Terri Windling's Blog, page 81

January 2, 2018

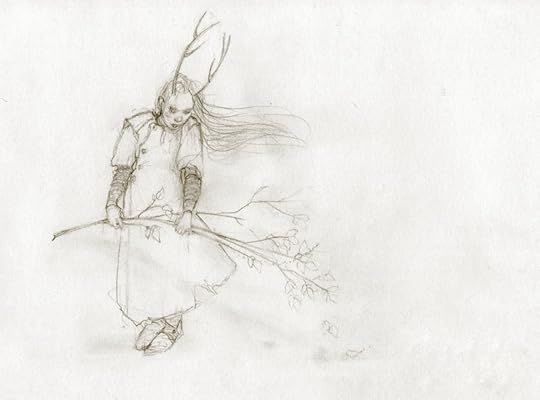

Myth & Moor update, with deer fairy

January 1, 2018

A new year begins

May the year ahead be magical, transformational, and wildly creative, but also calm and thoughtful, harmonious and balanced. May your pathway lie clear, your desk clean and ready, with the tools that you need always right near at hand. May your body and mind and spirit be strong for the things that you know in your heart must do (and may this be the year that you finally do them). May your work go well, and your rest time too. May problems be fewer and friends be many. May old hurt soften and old grief lighten. May life, art, and love never fail to surprise you.

Happy New Year from all of us at Bumblehill!

December 22, 2017

The best-laid schemes o' Mice an' Men....

I had a whole week of posts planned for you, full of recommended reading and mythic art publications -- but then the Winter Lurgy that's been making the rounds of the village turned up at my studio, scattering my work schedule and my best intentions to the cold winter wind.

I had a whole week of posts planned for you, full of recommended reading and mythic art publications -- but then the Winter Lurgy that's been making the rounds of the village turned up at my studio, scattering my work schedule and my best intentions to the cold winter wind.

Now the studio is closed for the holidays, and I'm officially away until January 2nd -- but I might sneak in for a post or two sometime next week, if the Lurgy permits and the creeks don't rise.

Tilly and I wish you good holiday cheer, in whatever form of cheer you like best: riotous celebration, or quiet peace and contentment, or anything in between.

For those who find the holiday season hard for any number of reasons, we send love and strength (both human and canine) from the green hills of Devon.

Thank you all for spending another year with us here at Myth & Moor.

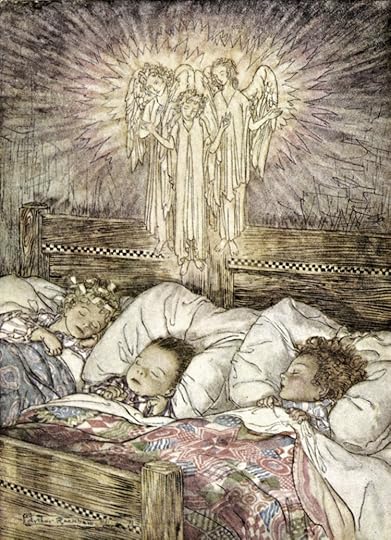

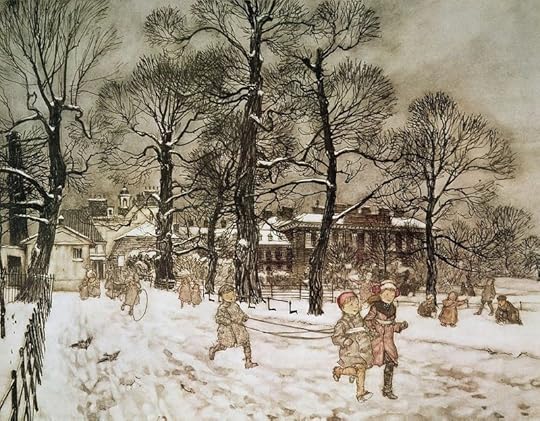

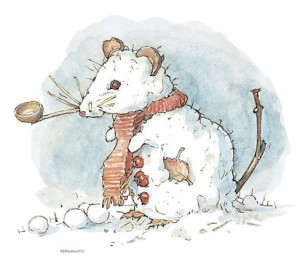

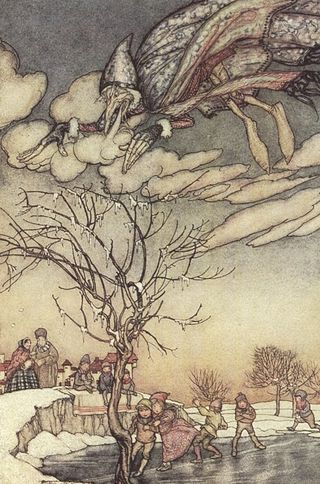

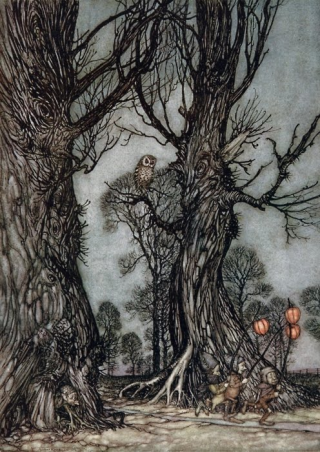

The title of this post comes from "To a Mouse" by Robert Burns. The art is "Jack Frost" and "The Dance in Cupid's Alley" by Arthur Rackham (1867-1939), and a charming little Brambley Hedge snow-mouse by Jill Barklem (1951-2017).

From the archives: The folklore of winter

There are always requests to reprint this post on winter folklore and Christmas customs at this time of year, so here it is:

A cold wind howls, stripping leaves off of the trees, and the pathways through the hills are laced with frost. It's time to admit that winter is truly here, and it's here to stay. But Howard keeps the old Rayburn stove in the kitchen well fed, so our wind-battered little house at the edge of the village is cozy and warm. Our Solstice decorations are up, and tonight I'll make a second batch of kiffles: the Christmas cookies passed on through generations of women in my mother's Pennsylvania Dutch family...carried now to England and passed on to our daughter, who may one day pass it to children of her own.

My personal tradition is to talk to those women of the past generations as I roll out the kiffle dough and cut, fill, roll, and shape each cookie: to my mother, grandmother, and old great-aunts (all of whom have passed on now)...and further back, to the women in the family line that I never knew.

Kiffles are a labor-intensive process (as so many of those fine old recipes were), so I have plenty of time to tell the Grandmothers news and stories of the year gone by. This annual ritual centers me in time, place, lineage, and history; it keeps my world turning through the seasons, as all storytelling is said to do. Indeed, in some traditions there are stories that can only be told in the wintertime.

Here in Devon, there are certain "piskie" tales told only in the winter months -- after the harvest is safely gathered in and the faery rites of Samhain have passed. In previous centuries, throughout the countryside families and neighbors gathered around the hearthfire during the long, dark hours of the winter season,  gossiping and telling stories as they labored by candle, lamp, and firelight. The "women's work" of carding, spinning, and sewing was once so entwined with storytelling that Old Mother Goose was commonly pictured by the hearth, distaff in hand.

gossiping and telling stories as they labored by candle, lamp, and firelight. The "women's work" of carding, spinning, and sewing was once so entwined with storytelling that Old Mother Goose was commonly pictured by the hearth, distaff in hand.

In the Celtic region of Brittany, the season for storytelling begins in November (the Black Month of Toussaint), goes on through December (the Very Black Month), and ends at Christmas. (A.S. Byatt, you may recall, drew on this tradition in her wonderful novel Possession.) In early America, some of the Puritan groups which forbade the "idle gossip" of storytelling relaxed these restraints at the dark of the year, from which comes a tradition of religious and miracle tales of a uniquely American stamp: Old World folktales transplanted to the New and given a thin Christian gloss. Among a number of the different Native American nations across the continent, winter is also considered the appropriate time for certain modes of storytelling: a time when long myth cycles are told and learned and passed through the generations. Trickster stories are among the tales believed to hasten the coming of spring. Among many tribes, Coyote stories must only be told in the dark winter months; at any other time, such tales risk offending this trickster, or drawing his capricious attention.

In myth cycles to be found around the globe, the death of the year in winter was echoed by the death and rebirth of the Winter King (also called the Sun King, or Year King), a consort of the Great Goddess  (representing the earth's fertility) in her local guise. The rebirth or resurrection of her consort (representing the sun, sky, or quickening winds) not only brought light back to the world, turning the seasons from winter to spring, but also marked a time of new beginnings, cleansing the soul of sins and sicknesses accumulated in the twelve months passed. Solstice celebrations of the ancient world included the carnival revels of Roman Saturnalia (December 17-24), the Anglo-Saxon vigil of The Night of the Mother to renew the earth's fertility (December 24th), the Yule feasts of the Norse honoring the One-Eyed God and the spirits of the dead (December 25), the Persian Mithric festival called The Birthday of the Unconquered Sun (December 25th), and the more recent Christian holiday of Christmas, marking the birth of the Lord of Light (December 25th).

(representing the earth's fertility) in her local guise. The rebirth or resurrection of her consort (representing the sun, sky, or quickening winds) not only brought light back to the world, turning the seasons from winter to spring, but also marked a time of new beginnings, cleansing the soul of sins and sicknesses accumulated in the twelve months passed. Solstice celebrations of the ancient world included the carnival revels of Roman Saturnalia (December 17-24), the Anglo-Saxon vigil of The Night of the Mother to renew the earth's fertility (December 24th), the Yule feasts of the Norse honoring the One-Eyed God and the spirits of the dead (December 25), the Persian Mithric festival called The Birthday of the Unconquered Sun (December 25th), and the more recent Christian holiday of Christmas, marking the birth of the Lord of Light (December 25th).

Many symbols we associate with Christmas today actually come from older ceremonies of the Solstice season. Mistletoe, holly, and ivy, for instance, were gathered in their magical potency by moonlight on Winter Solstice Eve, then used throughout the year in Celtic, Baltic and Germanic rites. The decoration of evergreen trees can be found in a number of older traditions: in rituals staged in decorated pine groves (the pinea silvea) of the Great Goddess; in the Roman custom of dedicating a pine tree to Attis on Winter Solstice Day; and in the candlelit trees of Norse Yule celebrations, honoring Frey and Freyja in their aspects of Hunter, Huntress, and Protectors of Forests. The Yule Log is a direct descendant from Norse and Anglo-Saxon rites; and caroling, pageantry, mummers plays, eating plum puddings, and exchanging gifts are all elements of Solstice celebrations handed down from the pre-Christian world.

Even the story of the virgin birth of a Divine, Heroic or Sacrificial Son is not a uniquely Christian legend, but one found in cultures all around the globe -- from the myths of Asia, Africa and old Europe to Native American tales. In ancient Syria, for example, a feast on the 25th of December celebrated the Nativity of the Sun; at midnight the sun was born in the form of a child to the Virgin Queen of Heaven, an aspect of the the goddess Astarte.

Likewise, it is interesting to note that the date chosen for New Year's Day in the Western world is a relatively modern invention. When Julius Caesar revised the Roman calendar in 46 BC, he chose January 1 -- following the riotous celebrations of Saturnalia -- as the official beginning of the year. Early Christians condemned the date as pagan, tied to licentious practices, and much of Europe resisted the Julian calendar until the  Gregorian reforms in the 16th century; instead, they celebrated New Year's Day on the 25th of December, the 21st of March, or various other dates. (England first adopted January 1 as New Year's Day in 1752).

Gregorian reforms in the 16th century; instead, they celebrated New Year's Day on the 25th of December, the 21st of March, or various other dates. (England first adopted January 1 as New Year's Day in 1752).

The Chinese, Jewish, Wiccan and other calendars use different dates as the start of the year, and do not, of course, count their years from the date of Christ's birth. Yet such is the power of ritual and myth that January 1st is now a potent date to us, a demarcation line drawn between the familiar past and the unknowable future. Whatever calendar you use, the transition from one year into the next is the traditional time to take stock of one's life -- to say goodbye to all that has passed and prepare for a new life ahead. The Year King is symbolically slain, the sun departs, and the natural world goes dark. Rituals, dances, pageants, and spiritual vigils are enacted in lands around the world to propitiate the sun's return and keep the great wheel of the seasons rolling.

Special foods are eaten on New Year's Day to ensure fertility, luck, wealth, and joy in the year to come: pancakes in France, rice cakes in Ceylon, new grains in India, and cake shaped as boar in Estonia and Sweden, among many others. In my family, we ate the last of those scrumptious kiffles...if they'd managed to last that long. They could not, by tradition, be made again before December of the following year, and so the last bite was always a little sad (and especially delicious). The Christmas tree and decorations were taken down on New Year's Day, and the house was thoroughly cleaned and swept: this was another Pennsylvania Dutch custom, brushing out any bad luck lingering from the year behind, making way for good luck to come.

May you have a lovely winter holiday, in whatever tradition you celebrate, full of all the magic of home and hearth, oven and table, and the wild wood beyond.

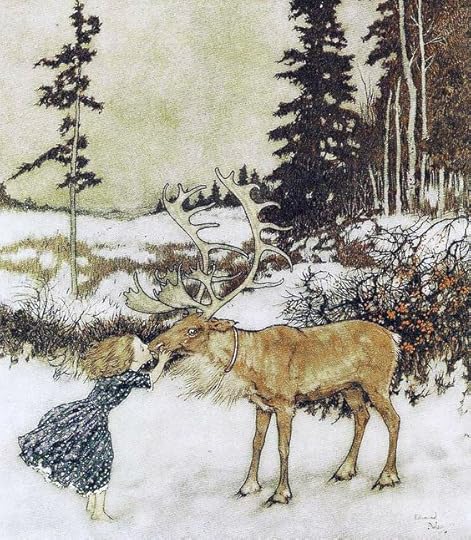

The paintings above are by three great artists of the Golden Age of Book illustration: Arthur Rackham (1867-1939), Edmund Dulac (1882-1953), and Charles Robinson (1870-1937). You'll find titles in the picture captions. (Run your cursor over the images to see them.) I recommend a related article by Derek Johnstone, published in The Conversation: "Why Ghosts Haunt England at Christmas But Steer Clear of America." Also, don't miss "Father Christmas: A New Tale of the North," a perfectly magical story by Charles Vess.

The paintings above are by three great artists of the Golden Age of Book illustration: Arthur Rackham (1867-1939), Edmund Dulac (1882-1953), and Charles Robinson (1870-1937). You'll find titles in the picture captions. (Run your cursor over the images to see them.) I recommend a related article by Derek Johnstone, published in The Conversation: "Why Ghosts Haunt England at Christmas But Steer Clear of America." Also, don't miss "Father Christmas: A New Tale of the North," a perfectly magical story by Charles Vess.

December 19, 2017

In the gift-giving season

From the Myth & Moor archives:

I've been thinking a lot about gifts lately, in all the various meanings of the word -- prompted, of course, by the season of holiday gift-giving that is upon us. Here in "austerity Britain," where work and money are increasingly scarce for those in freelance and arts professions (which are  precarious even at the best of times), a truly frightening number of people are struggling just to put food on the table and keep the lights on overhead. And then comes Christmas, with its lovely old traditions but overwhelming modern expectations; with its roots planted in the good soil of family, community, folklore, and sacred stories, but its leaves unfurled in the toxic air of commercialism and over-consumption.

precarious even at the best of times), a truly frightening number of people are struggling just to put food on the table and keep the lights on overhead. And then comes Christmas, with its lovely old traditions but overwhelming modern expectations; with its roots planted in the good soil of family, community, folklore, and sacred stories, but its leaves unfurled in the toxic air of commercialism and over-consumption.

Some of us cherish the holiday; some of us simply cope with it and then sigh with relief when it's all over; some of us re-shape it into something more nurturing and reflective of our own ideals; some of us turn our backs on it altogether; and some of us weren't raised with Christmas at all, but simply watch while the rest of the Western world goes crazy for a few weeks every year.

I love the spirit of Christmas gift-giving, but not the commercial pressure to shop and spend -- especially in these lean financial times when life is hard, even desperate, for so many. I also prefer to view gift-exchange as a daily part of life, not something confined to the holidays. We gift each other with meals prepared, with gardens tended, with the chores that keep a household running, with kindness, patience, care, attention...a constant giving-and-receiving that starts at home and extends into the world through friendship, community, and activism.

Making art is a form of gift-giving, made wondrous by the way that some of our creations move outward far beyond our ken, gifting recipients we do not know, will never meet, and sometimes could never imagine. And I, in turn, have received great gifts from writers, painters, musicians, dramatists and others who will never know of my existence either, and yet their words, images, or ideas, coming to me at the right time, have literally saved me.

The paradox inherent in making art, of course, is that it's an act involving both giving and receiving. Like breathing, it requires both, the inhalation and the exhalation. We receive the gift of inspiration (inhale), give it shape and form and pass it on (exhale).

The word "gift" itself is commonly used to describe artistic talent: she's a gifted cellist, he's a gifted poet. But where does that "gift" of inspiration come from? In semi-secular modernity, we tend to be politely vague about such things -- but in her book Big Magic, Elizabeth Gilbert has an unusual answer to the question:

"I should explain," she says, "at this point that I've spent my entire life in devotion to creativity, and along the way I've developed a set of beliefs about how it works -- and how to work with it -- that is entirely and unapologetically based upon magical thinking. And when I refer to magic here, I mean it literally. Like, in the Hogwarts sense. I am referring to the supernatural, the mystical, the inexplicable, the surreal, the divine, the transcendent, the otherworldly. Because the truth is, I believe that creativity is a force of enchantment -- not entirely human in its origins....

"I believe that our planet is inhabited not only by animals and plants and bacteria and viruses, but also by ideas. Ideas are a dis-embodied, energetic life-form. They are completely separate from us, but capable of interacting with us -- albeit strangely. Ideas have no material body, but they do have consciousness, and they most certainly have will. Ideas are driven by a single impulse: to be made manifest. And the only way an idea can be made manifest in our world is through collaboration with a human partner. It is only through a human's efforts that an idea can be escorted out of the ether and into the material world."

Rationalists will scoff at Gilbert's words, but there's enough mysticism in my own beliefs that her concept of creativity doesn't seem so very far-fetched to me; indeed, my only quibble with the paragraph above is that I'm not entirely convinced that those ideas necessarily require a human partner. (Perhaps animals and others with whom we share the planet have art forms of their own that we don't yet perceive.)

A little later in the book, Gilbert writes about creative work in terms that even the rationalists among us might recognize: "Most of my writing life, to be perfectly honest, is not freaky, old-time, voodoo-style Big Magic. Most of my writing life consists of nothing more than unglamorous, disciplined labor. I sit at my desk, and I work like a farmer, and that's how it gets done. Most of it is not fairy dust in the least.

"But sometimes it is fairy dust. Sometimes, when I'm in the midst of writing, I feel like I'm suddenly walking on one of those moving sidewalks you find in an airport terminal; I still have a long slog to my gate, and my baggage is still heavy, but I can feel myself being gently propelled by some exterior force. Something is carrying me along -- something powerful and generous -- and that something is decidedly not me....

"I only rarely experience this feeling, but it's the most magnificent sensation imaginable when it arrives. I don't think there is a more perfect happiness to be found in life than this state, except perhaps falling in love. In ancient Greek, the word for the highest degree of human happiness is eudaimonia, which basically means 'well-daemoned' -- that is, nicely taken care of by some external divine creative spirit guide."

(We've discussed the Greco-Roman idea of "creative daemons" in a previous post. Go here if you'd like to know more.)

C.S. Lewis, writing from a Christian perspective, also noted the mystical quality of creative inspiration:

"In the Author���s mind there bubbles up every now and then the material for a story. For me it invariably begins with mental pictures. This ferment leads to nothing unless it is accompanied with the longing for a Form: verse or prose, short story, novel, play or what not. When these two things click you have the Author���s impulse complete. It is now a thing inside him pawing to get out. He longs to see that bubbling stuff pouring into that Form as the housewife longs to see the new jam pouring into the clean jam jar. This nags him all day long and gets in the way of his work and his sleep and his meals. It���s like being in love."

"The artist's gift refines the materials of perception or intuition that have been bestowed upon him," says Lewis Hyde in his masterful book on the subject, The Gift: Creativity & the Artist in the Modern World. "To put it another way, if the artist is gifted, the gift increases in its passage through the self. The artist makes something higher than what he has been given, and this, the finished work, is the third gift, the one offered to the world."

Madeleine L'Engle was of a similar mind. In Walking on Water: Reflections on Faith & Art she wrote: "'We, and I think I'm speaking for many writers, don't know what it is that sometimes comes to make our books alive. All we can do is write dutifully and day after day, every day, giving our work the very best of what we are capable. I don't think that we can consciously put the magic in; it doesn't work that way. When the magic comes, it's a gift.''

���If," L'Engle added, "the work comes to the artist and says, 'Here I am, serve me,' then the job of the artist, great or small, is to serve. The amount of the artist's talent is not what it is about. Jean Rhys said to an interviewer in the Paris Review, 'Listen to me. All of writing is a huge lake. There are great rivers that feed the lake, like Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky. And there are mere trickles, like Jean Rhys. All that matters is feeding the lake. I don't matter. The lake matters. You must keep feeding the lake.' "

"One of the things we continue to learn from Native Peoples," says Terry Tempest Williams, "is that stories are our medicine bundles. I feel that way about our essays, our poems, our fictions. That it is the artist who carries the burden of the storyteller. Terrence Des Pres speaks of a prose witness that relies on the imagination to respond to the world as we see it, feel it, and dare to ask the questions that will not let us sleep. Imagination. Attention to details. Making the connections. Art -- right words to station the mind and hold the heart ready."

The gift of paying attention, of witnessing others' lives and passing the "medicine" of their stories, our stories, from generation to generation is the particular gift required of us as artists. Not only of us, but especially of us; in whatever artform we chose to work in.

Jane Yolen puts it most succinctly. "Touch magic," she says, "and pass it on."

The passage by Elizabeth Gilbert above is from Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear (Riverhead Books, 2015), which I recommend; all rights reserved by the author. Related posts: Knowing the World as a Gift, Gracious Acceptance, and On the Care & Feeding of Daemons & Muses.

December 17, 2017

Tunes for a Monday Morning

'Tis the season...

Above: "Fairytale Of New York" (the Pogues/Kirsty MacColl classic) performed by Katzenjammer and The Trondheim Soloists, from Norway, and Ben Caplan, from Nova Scotia.

Below: "Thaney," performed by Scottish singer Karine Powart at A Christmas Celtic Sojourn in Boston, Massachusetts. Polwart's song tells the story of the legendary Saint Thaney/Teneu/Enoch, whose son, Saint Mungo, is the patron saint of the city of Glasgow.

Above: "January, February (Last Month of the Year)," an American folk carol from Ruth Crawford Seeger's songbook, American Folk Songs for Christmas (1953) -- performed here by Amy Helm (lead vocals), Byron Isaacs, Daniel Littleton, Elizabeth Mitchell, Simi Stone, and Ruthy Ungar.

Below: "The Wexford Carol," a traditional Irish song dating back to the 12th century, performed by American bluegrass singer Alison Krauss and American cellist Yo-Yo Ma.

Above : "River," by Joni Mitchell, performed by American folk & roots musician Ana��s Mitchell and Swiss classical/folk/experimental musician Olivia Pedroli. The winter holidays can be a hard time for many people, for many different reasons. This one is for all who struggle to get through this time of year.

Below, in response to Joni 's melancholy tune: Rick Kemp's "Somewhere Along the Road," performed acapella by Steeleye Span -- a folk-rock band formed in 1969 and still making wonderful music together. This video warms my heart because it reminds me of winter gatherings around the table with my own circle of friends: toasting the seasons as as the years go by...growing older, greyer, slower, yes, but maybe a little wiser too. And still making art rooted in the folk tradition after all these years.

And one last song for the road:

"The Parting Glass," a traditional Scottish song performed acapella by two fine young bands: Kadia and Said the Maiden, filmed beside a Wassail bonfire at the Slindon Estate in West Sussex. Go here if you'd like to learn more about the folkways of Wassailing.

December 15, 2017

Creative solitude: an alternative view

After recommending Dorthe Nors' article on the value of creative solitude yesterday, I'd like to follow it up with an essay that takes a very different point of view: "How Not to Write Your First Novel" by American novelist Lev Grossman.

Fresh out of college and intending to be a writer, Lev headed West to find a lonely little town where he could "hunker down and get some real work done" -- and ended up on the coast of Maine. (For UK readers, this is like heading for Devon and ending up in the Shetlands.)

"I can't overstate how little I knew about myself at 22," he says, "or how little I'd thought about what I was doing. When I graduated from college I genuinely believed that the creative life was the apex of human existence, and that to work at an ordinary office job was a betrayal of that life, and I had to pursue that life at all costs. Management consulting, law school, med school, those were fine for other people -- I didn't judge! -- but I was an artist. I was super special. I was sparkly. I would walk another path.

"And I would walk it alone. That was another thing I knew about being an artist: You didn't need other people. Other people were a distraction. My little chrysalis of genius was going to seat one and one only."

Lev found the isolation he craved in a rustic (i.e., barely habitable) apartment down a long dirt road -- but isolation proved to be a less romantic and creatively fecund state then he'd imagined.

"I'm not even sure I understood how lonely I was. I had friends back in the real world, but I never asked anyone to visit me. On some level I still didn't believe that I could be lonely, even though it was staring me in the face, all day and all night. I genuinely thought that because I wanted to be a writer, that made me different from other people: mysterious, self-contained, a lone wolf, Han Solo.

"But by the end of November my sanity was starting to sag under the weight of all that solitude and empty time and creative failure. I wrote less and less and liked less and less of what I wrote. I felt like I couldn't go to bed till I'd accomplished something, anything, but usually that just meant I stayed up till dawn and then collapsed from exhaustion....

"Maine was trying to teach me something, but I was a slow learner. I thought I'd gone to Maine to face my demons and turn them into art, but it turned out that I couldn't face them, and not only that I couldn't even find them. I was trying to write about what I knew, which in itself probably wasn't a bad idea, but I was mistaken about what that was. I thought that what I knew most about was myself, but I could not have been more wrong. I didn't know the first thing about myself, and Maine wasn't going to teach me. You don't learn about yourself by being alone, you learn about yourself from other people."

To read the essay in full, please go here.

And while we're speaking of Lev today, I also recommend his fine essay on C.S. Lewis' The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe: "Confronting Reality by Reading Fantasy." And his 2015 Tolkien Lecture at Pembroke College, Oxford University.

December 14, 2017

The making of a writer

"A common question asked of writers is, 'When did you decide to become a writer?' The answer of course is that we didn't decide anything. It was decided for us. I firmly believe that mythical godmothers make appearances at our cradles, and bestow their gifts. The godmother who might have blessed me with a singing voice did not show up; the goddess of dance was nowhere in sight; the chef-to-the-angels was otherwise engaged. Only one made the journey to my cradle, and she whispered, 'You will be a storyteller.' "

- Mary Higgins Clark ("Touched by an Angel")

"People always want to know when and where you write. As if there's a secret methodology to be followed. It has never seemed to me to matter to the work -- which is the writer's 'essential gesture' (I quote Roland Barthes), the hand held out for society to grasp -- whether the creator writes at noon or midnight, in a cork-lined room as Proust did or a shed as Amoz Oz did in his early days.

"Perhaps the questioner is more than just curious, yearning for a jealously kept prescription on how to be a writer. There is none. Writing is the one profession for which there is no professional training. 'Creative' writing courses can teach the aspirant only how to look at his or her writing critically, not how to create. The only school for the writer is the library -- reading, reading. A journey through realms of how far, wide and deep writing can venture in the endless perspectives of human life. Learning from other writers' perceptions that you have to find your way to yours, at the urge of the most powerful sense of yourself -- creativity."

- Nadine Gordimer ("Being a Product of Your Dwelling Place")

"My love of writing grew out of my love of reading, with which my very life is identified. I can't imagine a mental life, a spiritual existence, not inetricably bound up with language of a formal, mediated nature. Telling stories, choosing an appropriate language with which to express each story: This seems to me quintessentially human, one of the great adventures of our species."

- Joyce Carol Oates ("The Importance of Childhood)

"Writers learn their craft, above all, from other writers. From reading. They learn it from immersing themselves in books....Perhaps they will have been encouraged along the way by a single, pivotal person; perhaps they will have learned perseverance after much rejection; perhaps they will get the recognition of readers and peers. Come what may, they must go to their desks alone."

- Marie Arana (Introduction to The Writing Life)

I find the sentiments expressed above interesting because they express my own experience of experience of writing: I am, by nature, a solitary person when it comes to writing (although not for visual art, which seems to draw on an entirely different part of my psyche), and have learned my trade through extensive reading and constant practice, plus the quietly intimate work of editing novels and stories by other writers. Yet here in the fantasy/mythic arts field, as well as in children's literature and folklore scholarship, many people I know have gained valuable professional training through classes, workshops, and MA programs; and/or they keep their skills honed through membership in writing groups. There is no right or wrong way to become a writer; it's a matter of finding out which method of learning the craft (and continuing to learn it) works best for each of us.

This aspect of the creative temperament is a subject that comes up often in our household, because my husband and I are very different. Howard works in the collaborative field of theatre and thrives when creatively engaged with others; the hardest parts of his work are those (like grant writing and admin work) that require him to sit at a desk alone. I am entirely the opposite. I crave silence and solitude, shutting out the clamour of the outside world in order to hear the quiet voice of my own imagination; and have a much harder time integrating the social aspects of my profession (and of life in general) with the hours and hours of solitary labour required to produce a book. Each of us needs a different tempo of life to do our best work, and creating a household that works for both of us is one of the challenges of a two-artist marriage. (There are different kinds of challenges, of course, for the single artist; as well as for artists with small children, artists in partnership with non-artists, etc..)

This aspect of the creative temperament is a subject that comes up often in our household, because my husband and I are very different. Howard works in the collaborative field of theatre and thrives when creatively engaged with others; the hardest parts of his work are those (like grant writing and admin work) that require him to sit at a desk alone. I am entirely the opposite. I crave silence and solitude, shutting out the clamour of the outside world in order to hear the quiet voice of my own imagination; and have a much harder time integrating the social aspects of my profession (and of life in general) with the hours and hours of solitary labour required to produce a book. Each of us needs a different tempo of life to do our best work, and creating a household that works for both of us is one of the challenges of a two-artist marriage. (There are different kinds of challenges, of course, for the single artist; as well as for artists with small children, artists in partnership with non-artists, etc..)

What makes a writer? Reading, reading, reading -- yes, I agree completely that reading widely and voraciously is the first and most important step. But the world we build around us is also what makes us artists, for good or ill. The ways we learn to write, and to keep on writing, do not happen in a vacuum: they're affected by the lives we lead, the commitments we have, the compromises we make, and the people we are.

I'd be interested to hear your thoughts on the subject, and your own experience.

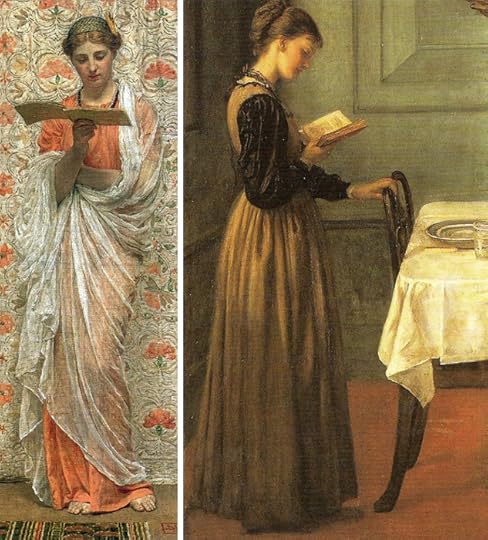

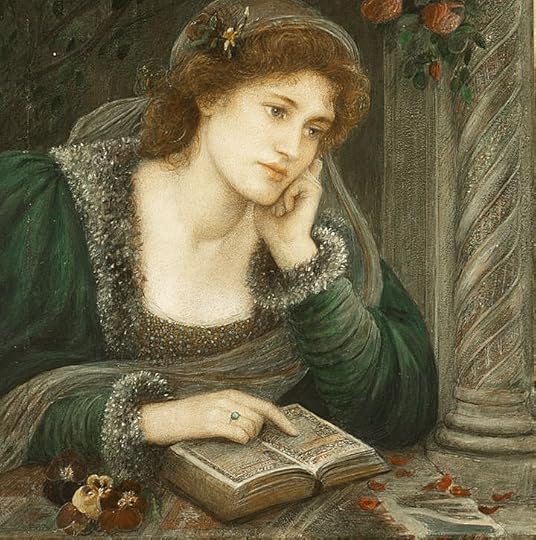

Pictures: In the Golden Days by John Melhuish Strudwick (1849-1937); The Gift That is Better Than Rubies by Eleanor Fortescue Brickdale (1872-1945); readers by Albert Moore (1841-1893) & Valentine Cameron Prinsep (1838-1904), Poetry by Simeon Solomon (1840-1905); Beatrice by Maria Spartali Stillman (1844-1927); Heidi and Peter Reading Together by Jessie Willcox Smith (1863-1935); and Reading Aloud by Julius LeBlanc Steward (1855-1919).

For fellow lovers of solitude, I recommend "What Great Artists Need: Solitude," in which Danish writer Dorthe Nors reflects on lessons learned from Igmar Bergman (The Atlantic, 2014)

December 13, 2017

The path forward

My apologies for the lack of a post yesterday (Tuesday). This blog's server, Typepad, was down all morning -- and by the time they had the platform up and running again, I was deep into my manuscript-in-progress. The post I'd planned for you is below, with yet more lovely art from the Pre-Raphaelite era.

I've enjoyed spending two weeks posting about the Pre-Raphaelites -- and could very easily keep going on the subject -- but I'm also aware that not everyone here is obsessed with Victorian art. I've got a few more PRB posts in the works, but I'll mix them up now with other posts on the usual topics: the writing life, the art-making process, fantasy, fairy tales, book recommendations and journeys through the Devon hills with Tilly, our mythic Animal Guide....

The photograph at the top of this post, by the way, is from my recent road trip to Kelmscott Manor, taken at the manor's doorway by Marja Lee Kru��t.

On becoming a writer

From "A Real Life Education" by novelist, playwright, and screenwriter Susan Minot:

"I never wanted to be a writer. That is, I never had the notion I wanted to be a writer. I started the way other people did, writing compositions in school. I liked doing that; it pulled at my imagination with a sort of elastic tension I enjoyed. The same thing happened when I made up games with  friends or put on plays with my brothers and sisters. There was something about elaborating on the world that gave great pleasure.

friends or put on plays with my brothers and sisters. There was something about elaborating on the world that gave great pleasure.

"But I also also enjoyed art class -- art wasn't even like a class it was so good; you got to make things with your hands -- and I liked science. Who wouldn't? We got to go outside and collect pollywogs in the pond. We got to dissect frogs and see the secret goings-on inside. If I had a thought about it, which I didn't because I was not practical, I would have pictured myself as an artist. I could picture painting in a studio with easels and brushes, or, even better, out in a landscape with a box of paints.

"But a writer? I had no picture in my mind of what being a writer was. How could I aspire to that? I'd never met a writer. What did a writer actually do? What did a writer have, words? I did not come from a literary family, despite the fact that two siblings and one step-sister became writers too. (And I would not be surprised if there were more to come.) My youngest sister, Eliza, who is a novelist, believes that part of it was our having to relay information among the siblings -- there were seven of us and a lot going on -- which encouraged our putting things into words."

"When I left home for boarding school," Minot notes later in the essay, "I began to write on my own -- prose poetry, journal writing. It was the first time I had a room of my own, and I found that writing was a way both of being alone and of finding what was going on inside of myself. Instead of doing homework, I wrote pages of stream-of-consciousness long into the night.

"The novelist Jim Harrison has said that he is suspicious of any budding writer who is not drunk with words. I was completely inebriated. I was compelled to write; it became a compulsion. I wrote out of desperation. In the great turmoil and gloom and euphoria of adolescence, I found there was nowhere to express the chaos of the emotions I was feeling, nowhere but in words. I began to rely so much on writing that I was living a double-life -- one in the world and one on the page. The one on the page was more intense, more satisfying and for a long time much more real....

"The novelist Jim Harrison has said that he is suspicious of any budding writer who is not drunk with words. I was completely inebriated. I was compelled to write; it became a compulsion. I wrote out of desperation. In the great turmoil and gloom and euphoria of adolescence, I found there was nowhere to express the chaos of the emotions I was feeling, nowhere but in words. I began to rely so much on writing that I was living a double-life -- one in the world and one on the page. The one on the page was more intense, more satisfying and for a long time much more real....

"I am very fortunate to make my living by writing, though I feel I got to this point through no more design than having followed an often bewildered instinct and by simply always writing. I believe that what an artist needs most, more than inspiration or financial consulation or encouragement or talent or love or luck, is endurance. Often the abstraction of using only words frustrates me -- I write on paper with a dipped pen and ink, and type on a manual typewriter in order to have some three-dimensional activities with my hands -- but again and again I discover how far words are capable of going, both in the world and on the page. The fact is, this side of the mind, nothing goes father than words. With words I am able to do those things that first intrigued me when I was young, those things that made me feel most alive -- I am able to paint pictures, collect things from muddy ponds, dissect insides, make things up, put on costumes, direct the lights, inspect hearts, entertain, dream.

"And, if it goes well, I might convey some of that vitality to others, and so give back a drop into that huge pool of what other artists have, as strangers, given me: a reason to live."

Pictures: A portrait of the artist's daughter, Gladys Holman Hunt, by William Holman Hunt (1827-1910), a founding member of The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood; "Fairy Tales" by Mary L. Gow (1851-1929); a portrait of Katie Lewis by Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1898); a sketch of Elisabeth Siddal reading by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, PRB (1828-1882); and a portrait of Winifred Robers by Eleanor Fortescue Brickdale (1872-1945).

Words: The passages above come from "A Real Life Education" by Susan Minot, published in The Writing Life, edited by Marie Arana (Public Affairs, 2003); all rights reserved by the author.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 708 followers