Terri Windling's Blog, page 84

November 14, 2017

Under the Oak Oak

I wrote this post at the beginning of November, 2016: a few months after the Brexit vote, and just before the U.S. election. One year later, it seems to me that we need moments of healing, grounding, life-affirming silence and stillness more than ever....

It's one more week until the U.S. election. For this and too many other reasons the Internet feels like one giant howl of anxiety, anguish, and rage..And what I've been thinking about lately is silence. There is not enough silence in modern life. I don't mean the complete absence of sound, but those quiet moments when the human world recedes: the haranguing voices of the daily news, the ads that follow us shouting Look at me!, the commercial and cultural sound and fury that makes it hard to hear our own inner voice, our own inner music, or our own heart beating, much less the beating heart of the natural world that we share with our nonhuman neighbors.

I have begun the practice of beginning my days in silence (no Internet, no screens, no news, no music) while I drink my morning coffee...often outdoors, if the weather permits, underneath the old oak pictured here, or in the woods, or another favorite spot close to the studio. Or else indoors, by a window looking out at the birds, the weather, the land. First watching, listening, then some reading (from a printed book, tactile, heavy in my hands). This slows me down; sets the tone for the day ahead; roots me in the physical world and not the manic, noisy, crowded, transitory realm of cyberspace. It prepares me for the deep work of creating by honing the sharp instrument my attention.

If I could gift you with one thing in the anxious week ahead, it would be this. Silence. Blessed silence.

"Why is silence important to writers?" Lorraine Berry asked Utah-based writer Terry Tempest Williams in an interview in 2013. "Is silence something that we all, regardless of whether we���re writers or not, need access to? And how do we find that in our increasingly tuned-in, turned-on world?"

"Silence is where we locate our voice," Williams answered, "both as writers and as human beings. In silence, the noises outside cease so the dialogue inside can begin. Silence takes us to an unknown place. It���s not necessarily a place of comfort. For me, the desert holds this space of quiet reflection; it���s erosional, like the landscape itself.

"You also ask why is it important that writers write and not embrace a life of silence. In many ways, we do embrace a lifestyle of silence, inward silence, a howling silence that brings us to our knees and desk each day. All a writer really has is time. Time to think. Time to read. Time to write.

"Time for a writer translates into solitude. In solitude, we create. In solitude, we are read. If we���re lucky, our books create community having been written out of solitude. It���s a lovely paradox. It���s the creative tension that I live with: I write to create community, but in order to do so, I am pulled out of community. Solitude is a writer���s communion."

November 13, 2017

Tunes for a Monday Morning

Today, more wonderful music with Nordic folk roots, this time from Denmark...

Above: "Shine You No More," a traditional tune re-worked by The Danish String Quartet, from their gorgeous new album Last Leaf. The quartet is: Rune Tonsgaard S��rensen (violin), Frederik ��land (violin), Asbj��rn N��rgaard (viola), and Fredrik Sch��yen Sj��lin (violoncello).

Below: "Gammel Reinlender fra S��nndala," another traditional piece, from WoodWork (2015). I recommend all of their albums, both classical and folk, which get a great deal of play in my studio.

Above: "A Room in Paris" from the Danish/Swedish folk trio Dreamer's Circus: Rune Tonsgaard S��rensen (from The Danish String Quartet, violin), Ale Carr (cittern), and Nikolaj Busk (piano accordion). The song is from their album Second Movement (2015), and the video features the great Danish-Spanish dancer Selene Mu��oz.

Below: "The Danish Immigrant" performed by Andreas Toph��j (fiddle) & Rune Barslund (button accordion), from their EP of the same name. The duo emerged from the Nordic/Celtic folk scene in the the city of Odense (which was Hans Christian Andersen's hometown).

And to end, as we started, with The Danish String Quartet:

"Five Sheep, Four Goats," a traditional Nordic tune performed at a radio studio in Seattle, Washington.

November 12, 2017

Myth & Moor update

I've been off-line due to health issues, both mine & the hound's (we're both on the mend), and a computer problem (which is now resolved). My apologies for the posts, messages, emails, & engagements I've missed, and deep thanks for your patience. Myth & Moor will resume publication tomorrow.

Art: wee Dog Girls from my old sketchbooks

October 30, 2017

Tunes for a Monday Morning

With Halloween, Samhain, and the Days of the Dead approaching, here are songs of witchcraft, hauntings, devilish deeds, and magic by moonlight....

Above: "Lancashire, God's Country" from Cunning Folk (George Nigel Hoyle), a musician, folklorist, and storyteller based in London. The song, based on the Pendle Witch Trials of 1612, comes from his gorgeous album Ritual Land, Uncommon Ground (2017). I also recommend the Cunning Folk blog for good posts on folklore, magic, and history.

Below: "Magpie," by the The Unthanks, from Northumbria. The song, written by David Dodds, is based on traditional counting rhymes, and appears on The Unthanks sixth album, Mount the Air (2015).

Above: "Devil's Resting Place" by singer/songwriter Laura Marling, based in London. The song is from her fourth album, Once I Was an Eagle (2013).

Below: "Pretty Polly," a murder ballad performed by Vandaveer (Mark Charles Heidinger and Rose Guerin), based in Kentucky. This traditional song comes from the British Isles, but can also be found in American Appalachian songbooks. It appears on Vandaveer's album of murder ballads, Oh, Willie, Please (2013).

Above: The spooky, folkloric video for "Black Horse" by singer/songwriter Lisa Knapp, from south London. The song appears on her second album, Hidden Seam (2013), and features vocals by James Yorkston.

Below: "La Fille Damnee" (The Damned Girl) by Breton harpist and songwriter C��cile Corbel. The song appears on her second album, SongBook Vol. 2 (2008).

The images today are of Avebury in Wiltshire and Callanish on the Isle of Lewis, photographed by my friend Stu Jenks. Visit Fizziwig Press to see more of his beautiful work.

October 25, 2017

Myth & Moor update

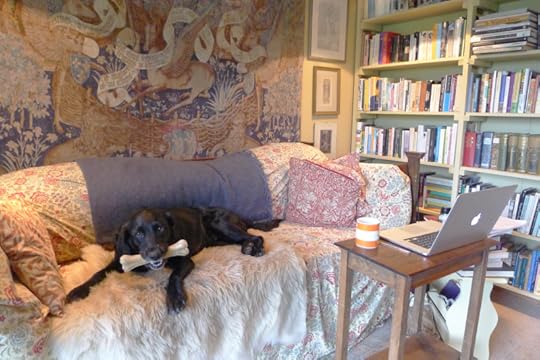

I'm off on a road trip to see the Mary Lobb exhibition at Kelmscott Manor. I'll be back in the studio on Thursday, and will tell you all about it. In the meantime, Tilly wants to be sure you all know that she has a new bone, and she's very proud.

October 23, 2017

Tunes for a Monday Morning

This week, folk music from northern Europe, both traditional and contemporary.

To start with: "Sparvens visa" (about a little sparrow and the coming of winter) by the Swedish folk trio Triakel: Emma H��rdelin (from the folk-rock band Garmarna), Kjell-Erik Eriksson (fiddle), and Janne Str��mstedt (harmonium). Their sixth and most recent album is Thyra (2014).

Above: "Le Fil" by the Swedish folk duo Symbio: Johannes Geworkian-Hellman on hurdy-gurdy and LarsEmil ��jeberget on accordion. They have one album out, Phoresy (2016), with a second due out next year.

Below: "Et steg ut" by Susanne Lundeng, a Norwegian fiddler and composer who draws inspiration from traditional Nordic music and jazz. In the video below she performs with Bj��rn Andor Drage (keyboard) and Arnfinn Bergrabb (percussion) in Bod��, in the north of Norway. Lungen's eighth and most recent solo album is 111 Nordlandssl��tter (2015.)

Above: "Shallow Digger" by Norwegian singer/songwriter Siv Jakobsen, based in Oslo on Norway's southern coast. The song is from her haunting new album The Nordic Mellow (2017).

Below: "How We Used to Love," an older song of Jakobsen's, from The Lingering (2015).

And to end as we began, with a song about a bird:

"Blackbird" by Swedish singer/songwriter Jenny Lysander, from her lovely first album Northern Folk (2015). The video was directed by Ana Tortos. Lysander is based in Stockholm.

The art today is: "The Maiden Notburga & her White Stag," a Norwegian fairy tale illustrated by Wilhelm Roegge (1829 - 1908), and "Gerda," from Andersen's The Snow Queen illustrated by Honor Appleton (1879-1951).

October 20, 2017

Animalness

���We need another and a wiser and perhaps a more mystical concept of animals. We patronize them for their incompleteness, for their tragic fate of having taken form so far beneath ourselves. For the animal shall not be measured by man. In a world older and more complex than ours, they move finished and complete, gifted with extensions of the senses we have lost or never attained, living by voices we shall never hear. They are not brethren, they are not underlings; they are other nations, caught with ourselves in the net of life and time, fellow prisoners of the splendour and travail of the earth.��� - Henry Beston (The Outermost House)

���How monotonous our speaking becomes when we speak only to ourselves! And how insulting to the other beings ��� to foraging black bears and twisted old cypresses ��� that no longer sense us talking to them, but only about them, as though they were not present in our world���Small wonder that rivers and forests no longer compel our focus or our fierce devotion. For we walk about such entities only behind their backs, as though they were not participant in our lives. Yet if we no longer call out to the moon slipping between the clouds, or whisper to the spider setting the silken struts of her web, well, then the numerous powers of this world will no longer address us ��� and if they still try, we will not likely hear them.��� - David Abram (Becoming Animal)

"Maybe it's animalness that will make the world right again: the wisdom of elephants, the enthusiasm of canines, the grace of snakes, the mildness of anteaters. Perhaps being human needs some diluting." - Carol Emshwiller (Carmen Dog)

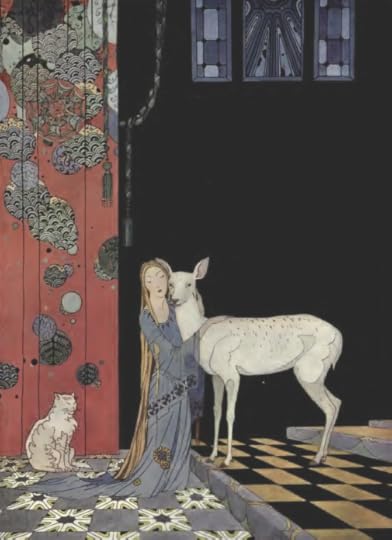

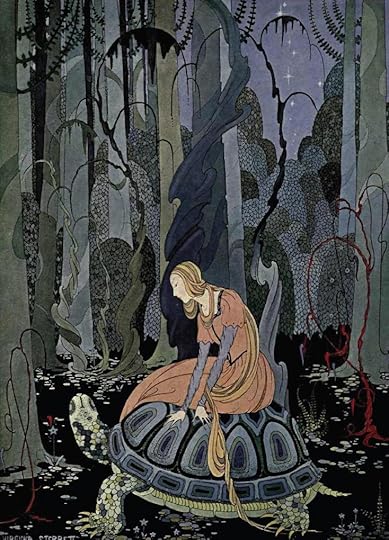

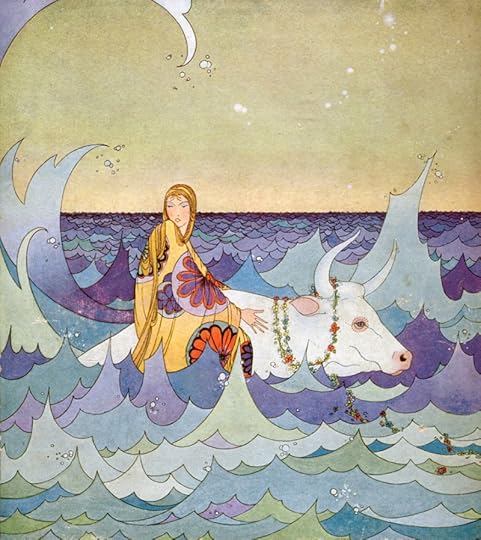

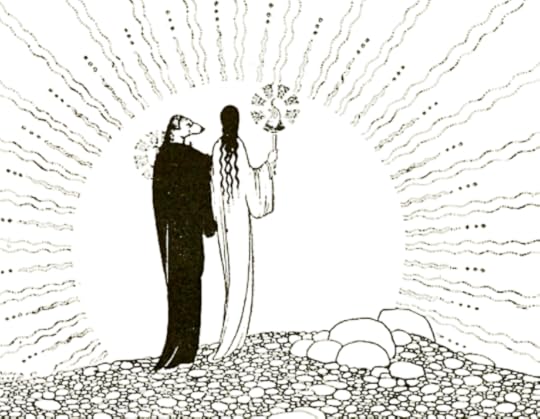

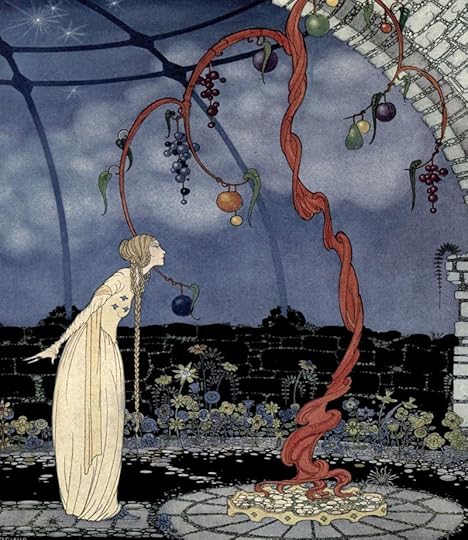

The art today is by American illustrator Virginia Frances Sterrett (1900-1931), who was born Chicago, but raised in Missouri after the early death of her father. She studied briefly at the Art Institute of Chicago, receiving a full scholarship when she was just 15 -- but had to leave when her mother grew ill and she took on sole support of her family. She worked in Chicago's advertising industry, and obtained her first book commission at the age of 19: illustrating Comtesse de S��gur's Old French Fairy Tales for the Penn Publishing Company in 1920, followed by Nathaniel Hawthorne's Tanglewood Tales in 1921.

At the same time Virginia's own health was failing and the diagnosis was grim: tuberculosis. The family moved to the warm, dry climate of California, but her health grew worse and worse, and she entered a sanatorium in Pasedena at age 24. She continued to work, but her output slowed, and her third book, The Arabian Nights, was not published until 1928. She was working on her last commission, Myths & Legends, when she died in 1931.

In a tribute to Sterrett, the Saint Louise Post-Dispatch reported: "Her achievement was beauty, a delicate, fantastic beauty, created with brush and pencil. Almost unschooled in art, her life spent in prosaic places of the West and Middle West, she made pictures of haunting loveliness, suggesting Oriental lands she never saw and magical realms no one ever knew except in the dreams of childhood....Perhaps it was the hardships of her own life that gave the young artist's work its fanciful quality. In the imaginative scenes she set down on paper she must have escaped from the harsh actualities of existence."

The quotes above first appeared on Myth & Moor in 2012, reposted today with updated art.

The quotes above first appeared on Myth & Moor in 2012, reposted today with updated art.

October 19, 2017

Holding the world in balance

Following on from yesterday's post, here's a passage from an interview with Chickasaw writer Linda Hogan noting the role of traditional ceremonies in mediating our relationship with animals:

"There were times when animals and people spoke the same language, or when the animals helped the humans. For instance, our mythology says it was the spider who brought us fire. I���ve thought about these human-animal relationships for years -- is this true? Well, humans and animals existed together for many thousands of years without creating the loss of species. There was enormous respect given to animals. I have to trust the knowledge of indigenous people because it held a world in balance.

"I have a special interest in ceremonies. I look at a ceremony called the Deer Dance. In the ceremony, I watch the entire world unfold through the life of the deer and a man dressed as a deer. The man dances all night. It is as if he were transformed into a deer. This is a renewal ceremony for the people. The deer that lives in the mountains far from the people provides them with life.

"The purpose of most ceremonies -- such as healing ceremonies -- is to return one person or group of people to themselves, to place the human in proper relationship with the rest of the world. I thought that we were out of touch with ourselves twenty years ago. Now, with computers and email and cell phones, we are even more out of touch. How many of us even stay in touch with our own bodies? If we aren���t inhabiting our own bodies, how can we understand animal bodies of the world?"

"Indian people," says Hogan, "must not be the only ones who remember the agreement with the land, the sacred pact to honor and care for the life that, in turn, provides for us. We need to reach a hand back through time and a hand forward, stand at the zero point of creation to be certain we do not create the absence of life, of any species, no matter how inconsequential they might appear to be. "

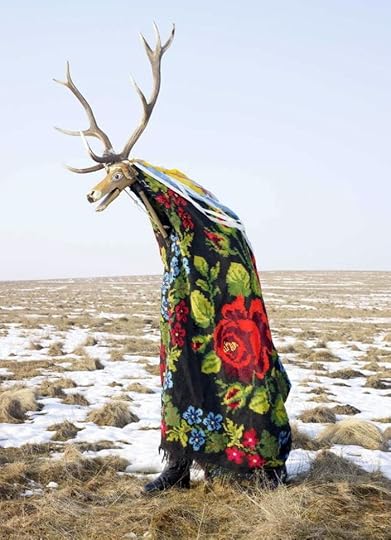

Pictures: A traditional stag dancer on New Year's Day in Romania (photographed by Ch arles Fr��ger ); Mayan, Portuguese, and Bhutan deers dancers (the second photograph by Fr��ger); a deer dancer performing at the Black Crane Festival in Bhutan; Tiben Cham Deers, early in the 20th & 21st centuries; a women's deer dance in Bali; an urban deer dance by American artist Carolyn Ryder Cooley ; Yaqui Deer and Pascola Dancers in procession in Sonora, Mexico; a Yaqui Deer Dancer in Arizona (photograph by Kyle Bowman), and Yokai spirits in Akita Prefecture, Japan (photographed by Charles Fr��ger). Please note that there are rules and taboos about photographing sacred ceremonies; I've only used photographs taken with permission.

Words: The first passage above is from an interview with Linda Hogan by Camille Colatosti, published onlne in The Witness. (Alas, it no longer appears to be available.) The second passage is from Hogan's essay collection Dwellings: A Spiritual History of the Living World (WW Norton, 2007), which I highly recommend. All rights reserved by the author.

Further reading: "Deer Woman and the Living Myth of the Dreamtime" by Carolyn Dunn, "Where the White Stag Runs" by Ari Berk, and two previous posts: "Wild Folklore" and "Homemade Ceremonies."

October 18, 2017

Keeping the world alive

From "First People" by Linda Hogan, an American poet, essayist, and novelist of the Chickasaw Nation:

"When I was younger...I heard stories of the times when humans and animals spoke with one another, but even while I concerned myself always with the lives of animals, caretaking the wounded ones, visiting the healthy, I never gave the old stories as much thought as they deserve. They were just stories, as if stories didn't matter. I didn't think then, as I do now, that a story is a container of knowledge. It is not only how we know about the world, but story is also how we find out about ourselves and our place of location within this world, as species, as Indian people, as women.

According to people who are from the oldest traditions, the relationship between the animal people and the humans is one of most significance. And this relationship is defined in story. Story is a power that describes our world, our human being, sets out the rules and intricate laws of human beings in relationship with all the rest. And for traditional-thinking native peoples, these rules of conduct and taboo are in place to keep a world alive, to ensure all life will continue.

'Once the world was occupied by a species called Ikxareyavs, "First People," who had magical powers. At a certain moment, it was realized that Human Beings were about to come spontaneously into existence. At this point, the First People announced their own transformation -- into mountains or rocks, into disembodied spirits, and above all into the species of plants and animals that now exist in the world....At the same time, it is ordained how the new species, the Human Beings, will live.' - Mamie Offield (Karok)

"As a young person, I didn't notice the similarity of stories the world over, that the Dineh people say we are the relatives of the animals, and that the aboriginal people of Australia say we are only one of many kinds of people. Nor did the old stories fit with my American education. Even though I was a half-hearted student at best, this education taught what my own, indigenous people once knew were the stories of superstitious and primitive people, not to be believed, not to be taken in a serious light. But we live inside a story, all of us do, and not only does a story prescribe our behavior, it also holds the unfathomed and and beautiful depths of a people, fostering and nurturing the very life of the future.

"The traditional native complex of laws and religion creates a way of seeing the world that doesn't allow for species loss, whether animal, plant, or insect. It has also been in the indigenous traditions, the place of ancient stories and ways of telling, that I have found the relationship between between humans and other species of animals most clearly articulated. Or, I might better say that the stories have found me. In this half-century-old Chickasaw woman they have found a ground in which to grow; they have found their place.

"The traditional native complex of laws and religion creates a way of seeing the world that doesn't allow for species loss, whether animal, plant, or insect. It has also been in the indigenous traditions, the place of ancient stories and ways of telling, that I have found the relationship between between humans and other species of animals most clearly articulated. Or, I might better say that the stories have found me. In this half-century-old Chickasaw woman they have found a ground in which to grow; they have found their place.

"What finally turned me back toward the older traditions of my own and other Native peoples was the inhumanity of the Western world, the places -- both inside and out -- where that culture's knowledge and language don't go, and the despair, even desperation, it has spawned. We live, I see now, by different stories, the Western mind and the indigenous. In the older, more mature cultures where people still live within the kinship circle of animals and human beings there is connection with animals, not only as food, but as 'powers,' a word that can be taken to mean states of being, gifts, or capabilities.

"I've found out too that the ancient intellectual traditions are not merely about systems of belief, as some would say. Belief is not a strong enough word. They are more than that: They are part of a lived experience, the ongoing experience of of people rooted in centuries-old knowledge that is held deep and strong, knowledge about the natural law of Earth, from the beginning of creation, and the magnificent terrestrial intelligence still at work, an intelligence now newly called ecology by the Western science that tells us what our oldest tribal stories maintain -- the human animal is a relatively new creation here; animal and plant presences were here before us; and we are truly the younger sisters and brothers of the other animal species, not quite as well developed as we thought we were. It is through our relationships with animals and plants that we maintain a way of living, a cultural ethics shaped from an ancient understanding of the world, and this is remembered in stories that are the deepest reflections of our shared lives on Earth.

"That we held, and still hold, treaties with the animals and plant species is a known part of tribal culture. The relationship between human people and animals is still alive and resonant in the world, the ancient tellings carried on by a constellation of stories, songs, and ceremonies, all shaped by lived knowledge of the world and its many interwoven, unending relationships. These stories and ceremonies keep open the bridge between one kind of intelligence and other, one species and other."

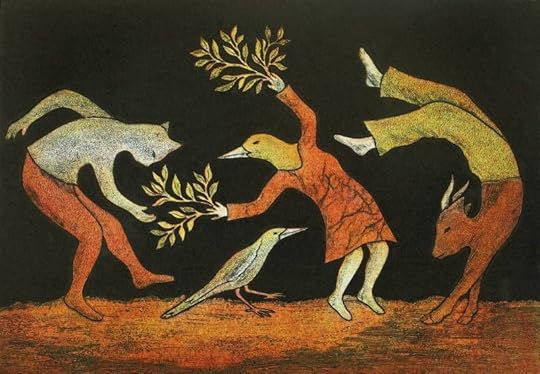

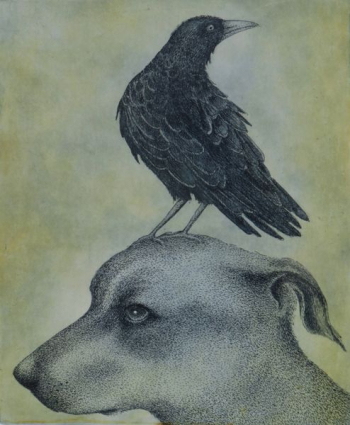

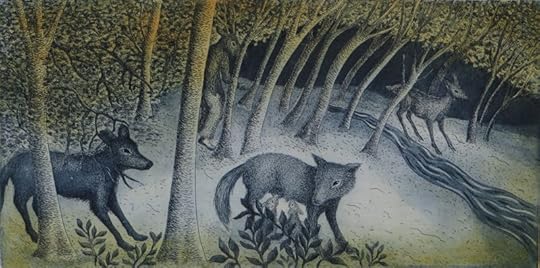

The beautiful imagery today consists of collographs, etchings, linocuts, and shadow prints by Australian artist Kati Thamo. Born in Western Australia to Hungarian parents, she studied art at Edith Cowan University and the Hobart School of Art, and now lives an works on the far south-west coast. From her website:

"The telling of tales has always been integral to Kati's art practice, and she draws on personal stories and incidents along with grander narratives to devise a form of visual fable. Using a cast of characters including animals and objects, her storylines describe the mystery, frailty, hopefulness and anxiety of life. She says, 'I often think of my images as small theatre settings where various dramas are enacted.' Her art is often imbued with her Eastern European heritage, and a journey to trace her migrant family's homelands in 2010 is reflected in subsequent exhibitions, and in the development of a series of works. More recently, Kati has been exploring the natural world, looking at ways to depict the fragility and complexity of natural ecosystems."

The passage above is from "First People" by Linda Hogan, published in Intimate Nature: The Bond Between Women & Animals, edited by Linda Hogan, Deena Metzger, and Brenda Peterson (Fawcett Columbine, 1998), which I highly recommend. All rights to the text and art above reserved by the author and artist.

October 16, 2017

Skunk Dreams

I'm sure I was not the only child who dreamed of sleeping with wild animals, although the closet I've come to that Jungle Book fantasy is to curl up with Tilly snoring beside me. The reality of animal life in the wild is different than fantasy tales of course -- as Louise Erdrich reminds us in this passage from her essay "Skunk Dreams":

"When I was fourteen, I slept alone on a North Dakota football field under the cold stars on an early spring night. May is unpredictable in the Red River Valley, and I happened to hit a night when frost formed in the grass. A skunk trailed a plume of steam across the forty-yard line near moonrise. I tucked the top of my sleeping bag over my head and was just dosing off when the skunk walked onto me with simple authority.

"Its ripe odor must have dissipated in the frozen earth of its winterlong hibernation, because it didn't smell all that bad, or perhaps it was just that I took shallow breaths in numb surprise. I felt him -- her, whatever -- pause on the side of my hip and turn around twice before evidently deciding I was a good place to sleep. At the back of my knees, on the quilting of my sleeping bag, it trod out a spot for itself and then, with a serene little groan, curled up and lay perfectly still. That made two of us. I was wildly awake, trying to forget the sharpness and number of skunk teeth, trying not to think of the high percentage of skunks with rabies, or the reason that on camping trips my father kept a hatchet underneath his pillow.

"Its ripe odor must have dissipated in the frozen earth of its winterlong hibernation, because it didn't smell all that bad, or perhaps it was just that I took shallow breaths in numb surprise. I felt him -- her, whatever -- pause on the side of my hip and turn around twice before evidently deciding I was a good place to sleep. At the back of my knees, on the quilting of my sleeping bag, it trod out a spot for itself and then, with a serene little groan, curled up and lay perfectly still. That made two of us. I was wildly awake, trying to forget the sharpness and number of skunk teeth, trying not to think of the high percentage of skunks with rabies, or the reason that on camping trips my father kept a hatchet underneath his pillow.

"Inside the bag, I felt as if I might smother. Careful, making only the slightest of rustles, I drew the bag away from my face and took a deep breath of the night air, enriched with skunk, but clear and watery and cold. It wasn't so bad, and the skunk didn't stir at all, so I watched the moon -- caught that night in an envelope of silk, a mist -- passing over my sleeping field of teenage guts and glory. The grass in spring that has lain beneath the snow harbors a sere dust both cold and fresh. I smelled that newness beneath the rank tone of my bag-mate -- the stiff fragrance of damp earth and the thick pungency of newly manured fields a mile or two away -- along with my sleeping bag's smell, slightly mildewed, forever smoky. The skunk settled even closer and began to breath rapidly; it's feet jerked a little like a dog's. I sank against the earth and fell asleep too.

"Of what easily tipped cans, what molten sludge, what dogs in back yards, what leftover macaroni casseroles, what cellar holes, crawl spaces, burrows taken from meek woodchucks, of what miracles of garbage did my skunk dream? Or did it, since we can't be sure, dream the plot of Moby Dick, how to properly age parmesan, or how to restore the brick-walled, tumbledown creamery that was its home? We don't know about the dreams of any other biota, and even much about our own. If dreams are an actual dimesion, as some assert, then the usual rules of life by which we abide do not apply. In that place, skunks may certainly dream themselves into the vests of stockbrokers. Perhaps that night the skunk and I dreamed each other's thoughts, or are still dreaming them. To paraphrase the problem of the Chinese sage, I may be a woman who has dreamed herself a skunk, or a skunk still dreaming she is a woman....

"Skunks don't mind each other's vile perfume. Obviously they find each other more than tolerable. And even I, who have been in the direct presence of a skunk hit, wouldn't classify their weapon as mere smell. It is more on the order of a reality-enhancing experience. It's not so pleasant as standing in a grove of old-growth red cedars, or watching trout rise to the shadow of your hand on the placid surface of an Alpine lake. When the skunk lets go, you are surrounded by skunk presence: inhabited, owned, involved with something you can only describe as powerfully there.

"I woke at dawn, stunned into that sprayed state of being. The dog that had approached me was rolling the grass, half-addled, sprayed too. The skunk was gone. I abandoned my sleeping bag and started home. Up Eighth Street, past the tiny blue and pink houses, past my grade school, past all the addresses where I had baby-sat, I walked in my own strange wind. The streets were wide and empty; I met no one -- not a dog, not a squirrel, not even an early robin. Perhaps they had all scattered before me, blocks away. I had gone out to sleep on the football field because I was afflicted with a sadness I had to dramatize. Mood swings had begun, hormones, feverish and brutal. They were nothing to me now. My emotions seemed vast, dark, and sickeningly private. But they were minor, mere wisps, compared to skunk."

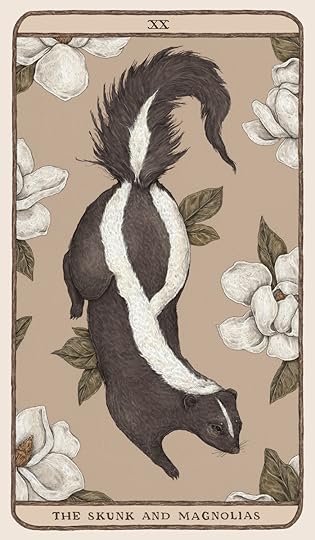

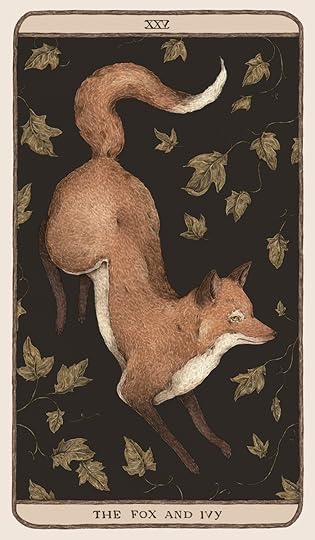

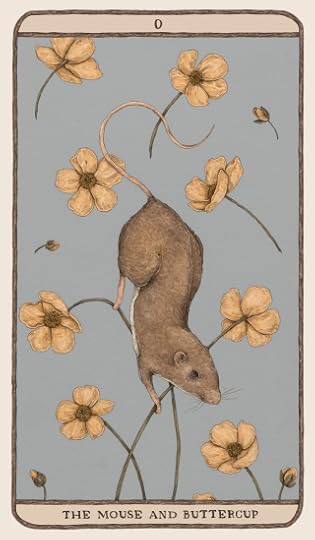

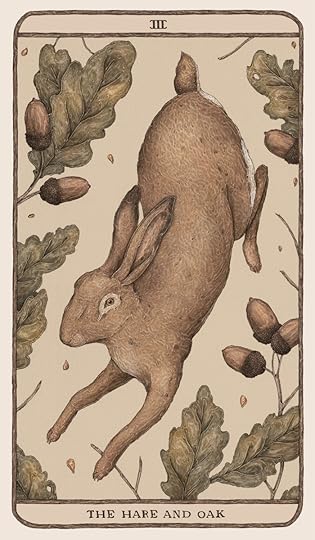

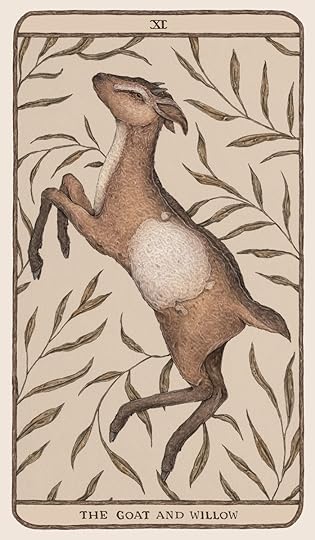

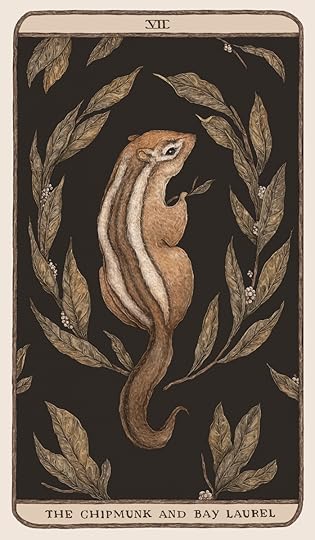

The art today is by Jessica Roux, an American painter whose work is rich in flora and fauna. Raised in the woodlands of North Carolina, Roux studied at the Savannah College of Art & Design in Georgia, and now works as a freelance illustrator and stationary designer.

"I can���t get enough of history," she says. "Old lithographs and studies by early naturalists are some of my favorite things. I love medieval bestiaries and the early Northern Renaissance. I���m also really inspired by nature. There are just so many strange plants and animals out there that I want to know more about."

The images here are from Roux's "Woodland Wardens" series, an oracle deck in progress. (I hope it's completed and published soon.) For those of you in or near Tennessee, the series can be viewed at Gallery 205 in Columbia through Dec. 1st.Y

You can also see more of her work on her website and in her print shop here.

The passage above is from "Skunk Dreams" by Louise Erdrich, first published in The Georgia Review (1993). All rights to the text and art above reserved by the author and artist.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 708 followers