Terri Windling's Blog, page 88

August 25, 2017

The words that matter

���For adults, the world of fantasy books returns to us the great words of power which, in order to be tamed, we have excised from our adult vocabularies. These words are the pornography of innocence, words which adults no longer use with other adults, and so we laugh at them and consign them to the nursery, fear masking as cynicism. These are the words that were forged in the earth, air, fire, and water of human existence, and the words are: Love. Hate. Good. Evil. Courage. Honor. Truth."

- Jane Yolen (Touch Magic: Fantasy, Faerie & Folklore in the Literature of Childhood)

"Storytelling, like rhetoric, pulls us in through the cognitive mind as much as through the emotions. It answers both our curiosity and our longing for shapely forms: our profound desire to know what happens, and our persistent hope that what happens will somehow make sense. Narrative instructs us in both these hungers and their satisfaction, teaching us to perceive and to relish the arc of moments and the arc of lives. If shapeliness is an illusion, it is one we require -- it shields against arbitrariness and against chaos���s companion, despair. And story, like all the forms of concentration, connects. It brings us to a deepened coherence with the world of others and also within the many levels of the self.''

- Jane Hirshfield (Nine Gates: Entering the Mind of Poetry)

"Words are intrinsically powerful. And there is magic in that. Words come from nothing into being. They are created in the imagination and given life on the human voice. You know, we used to believe -- and I am talking about all of us, regardless of our ethnic backgrounds -- in the magic of words. The Anglo-Saxon who uttered spells over his field so that the seeds would come out of the ground on the sheer strength of his voice, knew a good deal about language, and he believed absolutely in the efficacy of language. That man's faith -- and may I say, wisdom -- has been lost upon modern man, by and large. It survives in the poets of the world, I suppose, the singers. We do not now know what we can do with words. But as long as there are those among us who try to find out, literature will be secure; literature will be a thing worthy of our highest level of human being."

- N. Scott Momaday (Survival This Way: Interviews with American-Indian Poets)

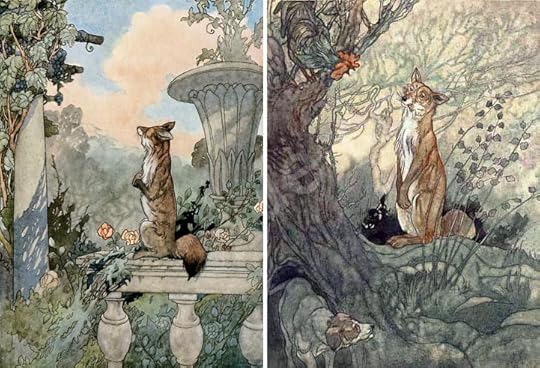

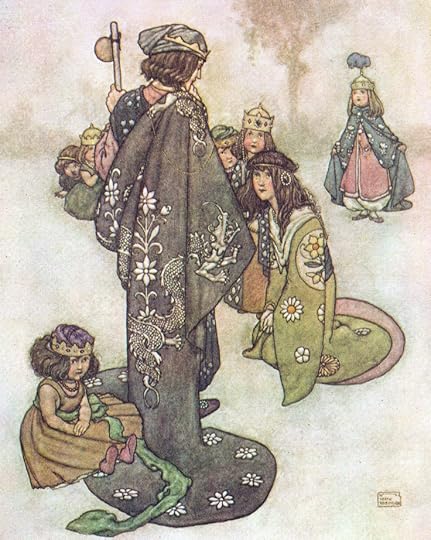

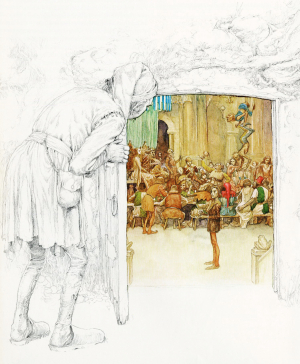

The art today is by brothers Charles Robinson (1870-1937) and William Heath Robinson (1872-1944), who were raised in a family of artists in Finbury Park, north London.

August 24, 2017

Handle with care

Words

by Anne Sexton

Be careful of words,

even the miraculous ones.

For the miraculous we do our best,

sometimes they swarm like insects

and leave not a sting but a kiss.

They can be as good as fingers.

They can be as trusty as the rock

They can be as trusty as the rock

you stick your bottom on.

But they can be both daisies and bruises.

Yet I am in love with words.

They are doves falling out of the ceiling.

They are six holy oranges sitting in my lap.

They are the trees, the legs of summer,

and the sun, its passionate face.

Yet often they fail me.

I have so much I want to say,

so many stories, images, proverbs, etc.

But the words aren't good enough,

the wrong ones kiss me.

Sometimes I fly like an eagle

but with the wings of a wren.

But I try to take care

and be gentle to them.

Words and eggs must be handled with care.

Once broken they are impossible

things to repair.

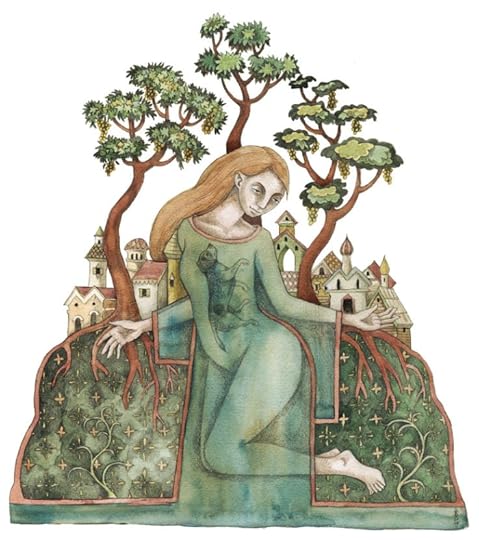

Pictures: The illustrations are by Julianna Swaney, who finds inspiration in nature, children's stories, fairy tales, and history. Poem: "Words" is from The Complete Poems by Anne Sexton (Houghton Mifflin, 1999). Further thoughts on the power of words are tucked into the picture captions (Run your cursor over the images to see them.) All rights to the art and text above reserved by the artist and the authors. Photographs: By the Wallabrook on Dartmoor.

August 23, 2017

Letters, words, stories

''Stories, like people and butterflies and songbirds' eggs and human hearts and dreams, are also fragile things, made up of nothing stronger or more lasting than twenty-six letters and a handful of punctuation marks. Or they are words on the air, composed of sounds and ideas -- abstract, invisible, gone once they've been spoken -- and what could be more frail than that? But some stories, small, simple ones about setting out on adventures or people doing wonders, tales of miracles and monsters, have outlasted all the people who told them, and some of them have outlasted the lands in which they were created.''

- Neil Gaiman (Fragile Things)

"A story is not like a road to follow...it's more like a house. You go inside and stay there for a while, wandering back and forth and settling where you like and discovering how the room and corridors relate to each other, how the world outside is altered by being viewed from these windows. And you, the visitor, the reader, are altered as well by being in this enclosed space, whether it is ample and easy or full of crooked turns, or sparsely or opulently furnished. You can go back again and again, and the house, the story, always contains more than you saw the last time. It also has a sturdy sense of itself of being built out of its own necessity, not just to shelter or beguile you."

- Alice Munro (Selected Stories)

"I spent my life folded between the pages of books. In the absence of human relationships I formed bonds with paper characters. I lived love and loss through stories threaded in history; I experienced adolescence by association. My world is one interwoven web of words, stringing limb to limb, bone to sinew, thoughts and images all together. I am a being comprised of letters, a character created by sentences, a figment of imagination formed through fiction."

- Tahereh Mafi (Shatter Me)

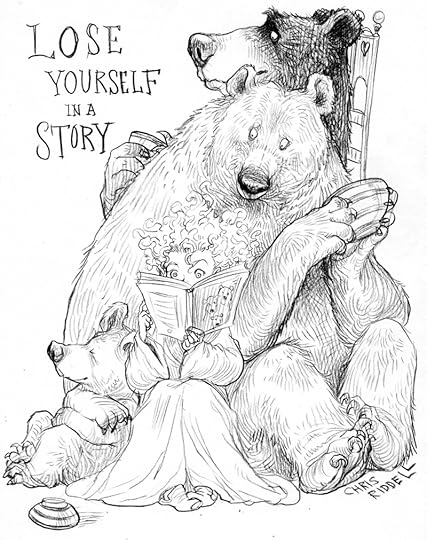

The drawings today are by the great Chris Riddell: illustrator, author, former UK Children's Laureate, and a tireless advocate for the importance of stories and art.

August 20, 2017

Tunes for a Monday Morning

After last week's discussion of Gaelic place-names, we must surely start the week some Gaelic songs....

In the documentary series Port, Scottish singer Julie Fowlis teamed up with Irish singer Muireann NicAmhlaoibh to investigate Gaelic music and culture in its variations across the two countries. We listened to songs from the northern islands of Scotland in a previous post. Today, we start with two Post performances filmed in Ireland.

Above: "D�� Domhnaigh/Elean��r na R��n."

Below: "Fill-i�� Oro H�� ��/O C�� Bheir Mi Leam."

The singers are Niamh Farrell (from Ireland) and Linda Macleod (from Scotland), backed up Stephen Markham, Seamie O'Dowd, Fowlis and NicAmhlaoibh.

Above: The Gloaming's recording session for "The Pilgrim's Song," based on the Irish-language poems of Se��n �� Riord��in. Iarla �� Lion��ird sings in the sean-n��s style (traditionally performed a capella), accompanied by Martin Hayes, Caoimh��n �� Raghallaigh, Dennis Cahill, and Thomas Bartlett.

Below: "Aurora," an instrumental piece by the Irish band Beoga. The group is: Damian McKee, Se��n ��g Graham, Liam Bradley, Eamon Murray, and Niamh Dunne.

The art today is by Ronan Halpin, who studied at the National College of Art & Design in Dublin and the Yale School of Art in America. He now lives and works on Achill Island, off of Ireland's west coast.

The pieces here are: Achill Goat, Pooka, Chimera, and The Old King.

August 18, 2017

Out of the studio

Sorry, everyone, I got caught up in other commitments and wasn't able to post earlier today. I'll be back in the studio, and back to Myth & Moor, on Monday morning.

In the meantime, let me leave you with George Saunder's thoughts on kindness:

"There���s a confusion in each of us, a sickness, really: selfishness. Be a good and proactive and even somewhat desperate patient on your own behalf -- seek out the most efficacious anti-selfishness medicines, energetically, for the rest of your life.

"Do all the other things, the ambitious things -- travel, get rich, get famous, innovate, lead, fall in love, make and lose fortunes, swim naked in wild jungle rivers (after first having it tested for monkey poop) -- but as you do, to the extent that you can, err in the direction of kindness. Do those things that incline you toward the big questions, and avoid the things that would reduce you and make you trivial. That luminous part of you that exists beyond personality -- your soul, if you will -- is as bright and shining as any that has ever been. Bright as Shakespeare���s, bright as Gandhi���s, bright as Mother Teresa���s. Clear away everything that keeps you separate from this secret luminous place. Believe it exists, come to know it better, nurture it, share its fruits tirelessly."

Amen.

The art above is by American sculptor Adrian Arleo.

August 17, 2017

True names

Continuing our discussion of the "language of place" with another passage from Robert Macfarlane's fine book Landmarks:

"The extraordinary language of the Outer Hebrides is currently being lost. Gaelic itself is in danger of withering on the tongue: the total number of those speaking or learning to speak Gaelic in Scotland is now around 58,000. Of those, many are understandably less interested in the intricacies of toponymy, or the exactitudes of what the language is capable of regarding landscape. Tim Robinson -- the great writer, mathematician and deep-mapper of the Irish Atlantic seaboard -- notes how with each generation in the west of Ireland 'some of the place-names are forgotten or becoming incomprehensible.' Often in the Outer Hebrides I have been told that younger generations are losing the literacy of the land....

"What is occurring in Gaelic is, broadly, occuring in English too -- and in scores of other languages and dialects. The nuances observed by specialized vocabularies are evaporating from common usage, burnt off by capital, apathay and urbanization. The terrain beyond the city fringe has become progressively more understood in terms of large generic units ('field,' 'hill,' valley,' 'wood'). It has become a blandscape. We are blas�� about place, in the sense that Georg Simmel used the word in his 1903 essay 'The Metropolis and the Mental Life' -- meaning indifferent to the distinction between things.

"It is not, on the whole, that natural phenomena and entities themselves are disappearing; rather that there are fewer people to name them, and that once they go unnamed they go to some degree unseen. Language deficit leads to attention deficit. As we further deplete our ability to name, describe and figure particular aspects of our places, our competence for understanding and imagining possible relationships with non-human nature is correspondingly depleted. The enthno-linguist K. David Harrison bleakly declares that language death means the loss of 'long-cultivated knowledge that has guided human-environment interaction for millennia...accumulated wisdom and observations of generations of people about the natural world, plants, animals, weather, soil. The loss [is] incalculable, the knowledge almost unrecoverable.' Or as Tim Dee neatly puts it, 'Without a name in our mouths, an animal or a place struggles to find purchase in our minds or our hearts."

One question I've been pondering lately is: How can fantasy writers use the metaphorical language of our form to strengthen our relationship to place, and to ameliorate the "language deficit that leads to attention deficit"? How do we re-enchant the land, in art and actuality?

More on that tomorrow.

Words: The passage by Robert Macfarlane is quoted f rom Landmarks (Hamish Hamilton, 2015; Penguin Books, 2016). The poem in the picture captions is from The Cloud Collector: Poems & Tale in Scots & English by Sheena Blackhall (Lochlands, 2015). All rights reserved by the authors. Pictures: Tilly encounters Dartmoor ponies on the hill behind our house.

August 16, 2017

The mnemonics of words

Following on from last week's discussion of the language of place, this week is devoted to Landmarks, Robert Macfarlane's extraordinary book on the subject:

"Ultra-fine description operates in Hebridean Gaelic place-names," writes Macfarlane, "as well as in descriptive nouns. In the 1990s an English linguist called Richard Cox moved to northern Lewis, taught himself Gaelic, and spent several years retrieving and recording place-names in the Carloway district of Lewis's west coast. Carloway contains thirteen townships and around five hundred people; it is fewer than sixty square miles in area. But Cox's magnificent resulting work, The Gaelic Place-Names of Carloway, Isle of Lewis: Their Structures and Significance (2002), runs to almost five hundred pages and details more than three thousand place-names. Its eleventh section, titled "The Onimasticon,' lists the hundreds of toponyms identifying 'natural features' of the landscape. Unsurprisingly for such a martime culture, there is a proliferation of names for coastal features -- narrows, currents, indentations, projections, ledges, reefs -- often of exceeptional specificity. Beirgh, for instance, a loanword from the Old Norse, refers to ' a promontory or point with a bare, usually vertical rock face and sometimes with a narrow neck to land,' while corran has the sense of 'rounded point,' derived from its common meaning of 'sickle.'

"There are more than twenty different terms for eminences and precipices," Macfarlane continues, "depending on the sharpness of the summit and the aspects of the slope. S��thean, for example, deriving from s��th, 'a fairy hill or mound,' is a knoll or hillock possessing the qualities which were thought to  constitute desirable real estate for fairies -- being well-drained, for instance, with a distinctive rise, and crowned by green grass. Such qualities also fulfilled the requirements for a good sheiling site, and so almost all toponyms including the word s��thean indicates sheiling locations. Characterful personifications of place also abound: A' Gh��ig, for instance, means 'the steep slope of a scowling expression.'

constitute desirable real estate for fairies -- being well-drained, for instance, with a distinctive rise, and crowned by green grass. Such qualities also fulfilled the requirements for a good sheiling site, and so almost all toponyms including the word s��thean indicates sheiling locations. Characterful personifications of place also abound: A' Gh��ig, for instance, means 'the steep slope of a scowling expression.'

"Reading 'The Onomasticon,' you realize that Gaelic speakers of this landscape inhabit a terrain which is, in Proust's phrase, 'magnificently surcharged with names.' For centuries these place-names have spilled their poetry into everyday Hebridean life. They have anthologized local history, anecdote and myth, binding story to place. They have been functional -- operating as territory markers and ownership designators -- and they have also served as navigational aids. Until well into the 20th century, most inhabitants of the Western Isles did not use conventional paper maps, but relied instead on memory maps, learnt on the island and carried in the skull.

"These memory maps were facilitated by first-hand experience and were also -- as Finlay [MacLeod] put it -- 'lit by the mnemonics of words.' For their users, these place-names were necessary for getting from location to location, and for the purpose of guiding others to where they needed to go. It is for this reason that so many toponyms incorporate what is known in psychology and design as 'affordance' -- the quality of an environment or object that allows an individual to perform an action on, to or with it. So a bealach is a gap in a ridge or cliff which may be walked through, but the element be��rn or beul in a place-name suggests an opening that is unlikely to admit human passage, as in Am Beul Uisg, 'the gap from which the water gushes.' Bl��r a' Chalchain means 'the plain of stepping stones,' while Clach an Line means 'rock of the link,' indicating a place where boats can be safely tied up. To speak out a run of these names is therefore to create a story of travel-- an act of naming that is also an act of wayfinding.

"Angus MacMillan, a Lewisian, remembers being sent by his father seven miles across Brindled Moor to fetch a missing sheep spotted by someone the night before: 'C��l Leac Ghlas ri taobh Sloc an Fhithich fos cionn Loch na Muilne.' 'Think of it,' writes MacMillan drily, 'as an early form of GPS: the Gaelic Positioning System.' "

The history and significance of place-names in land-based societies is something that those of us writing mythic fiction would do well to bear in mind -- whether we're working with myth or folktales born from a specific landscape, or creating an imaginary one.

"Invented names are a quite good index of writers' interest in their instrument, language, and ability to place it," says Ursula Le Guin. "To make up a name of a person or place is to open the way to the world of the language the name belongs to. It's a gate to Elsewhere. How do they talk in Elsewhere? How do we find out how they talk?"

Perhaps by knowing the land they walk. Which begins with knowing our own.

Words: The passage by Robert Macfarlane is quoted f rom Landmarks (Hamish Hamilton, 2015; Penguin Books, 2016). The passage by Ursula K. Le Guin is quoted from her essay "Inventing Languages," in Words Are My Matter (Small Beer Press, 2016). The poem in the picture captions is from The Bonniest Companie by Kathleen Jamie (Picador, 2015). All rights reserved by the authors.

Pictures:. There is a mismatch of words and photographs in this post, I'm afraid, for my own recent journey north took me only to the Isle of Skye and not to the Lewis moor. The photographs above are of our moor, Dartmoor, near

Scorhill, a bronze age stone circle. The illustration is "Looking Into the Fairy Hill" by my friend & neighbor Alan Lee. It's from his now-classic book Faeries, with Brian Froud (Abrams, 1978); all rights reserved by the artist

August 15, 2017

Weather and words

From Landmarks by Robert Macfarlane:

"Before you become a writer you must first become a reader. Every hour spent reading is an hour spent learning to write; this continues to be true throughout a writer's life. The Living Mountain, Waterlog, The Peregrine, Arctic Dreams, My First Summer in the Sierra: these are the books that taught me how to write, but also the books that have taught me how to see...."

"Books, like landscapes, leave their marks in us. Sometimes these traces are so faint as to be imperceptible -- tiny shifts in the weather of the spirit that do not register on the usual instruments. Mostly these marks are temporary: we close a book, and for the next hour or two the world seems oddly brighter at its edges; or we are moved to a certain kindness or meaness that would otherwise have gone unexpressed. Certain books though, like certain landscapes, stay with us even when we have left them, changing not just our weathers but our climates. The word landmark is from is from the old English landmearc, meaning 'an object in the landscape which, by its conspicuousness, serves as a guide in the direction of one's course.' John Smith, writing in his 1627 Sea Grammar, gives us this definition: 'a Land-marke is any Mountaine, Rocke, Church, Wind-mill or the like, that the Pilot can now by comparing one by another see how they beare by the compasse.' Strong books and strong words can be landmarks in Smith's sense -- offering us both a means of establishing our location and of knowing how we 'beare by the compasse.' "

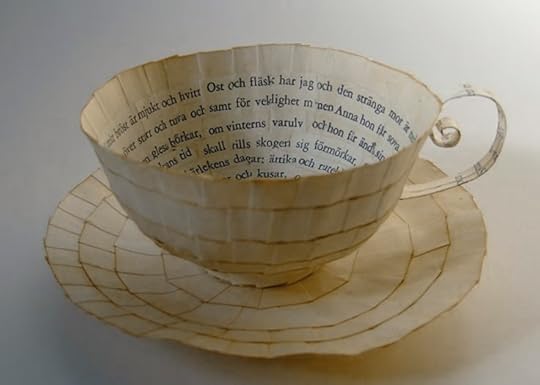

The art today is by Swedish paper artist Cecelia Levy. Please visit her website to learn more about her work.

The text above is quoted from Landmarks by Robert Macfarlane (Hamish Hamilton, 2015; Penguin Books, 2016), which I high recommend. All rights to the text and art above reserved by the author and artist.

The text above is quoted from Landmarks by Robert Macfarlane (Hamish Hamilton, 2015; Penguin Books, 2016), which I high recommend. All rights to the text and art above reserved by the author and artist.

August 13, 2017

Tunes for a Monday Morning

In troubled times, we need music to lift our spirits more then ever -- so today I'm turning to The Mae Trio from Melbourne, Australia to brighten the start of a new week. The musicians are Maggie Rigby (banjo, ukulele, guitar), her sister Elsie Rigby (violin, ukulele), and Anita Hillman (cello, bass).

Above: The video for "Well Enough Alone" from the trio's new album, Take Care, Take Cover.

Below: "Mr. Moon," filmed for the Songs from a Room series in London in 2015.

Above: An acapela version of Kate Rubsy's song "Lately," which was on their first album, Housewarming (2014).

Below: "Grandman's," filmed for the Songs from a Room series in June of this year.

And one more:

The Mae Trio and the great Scottish songwriter Dougie Maclean perform "She Loves Me."

The lovely paintings above are by Rima Staines.

August 11, 2017

Wanderers and wilderness

This piece was originally posted in August, 2015.

Like Robert Macfarlane (discussed in this previous post), Sara Maitland is fascinated by the peregrini: the early Celtic Christian monks and mystics who set out alone in small, flimsy boats, seeking solitude, nature, and God on the most remote islands of Britain.

"On island after island," she writes in A Book of Silence, "the more isolated and far-flung the better -- on St. Kilda, on the Farnes, on the Shiants, throughout the Hebrides and the northern islands, off the coast of Ireland, around Iceland and possibly even North America -- the traces of hermits can be found. This history is confused and uncertain, but originating in Ireland in the fifth century, there was a well-developed form of Christian spirituality which valued the silent eremitical vocation extremely highly.

"In Britain, the most famous such voluntary exile was Columba, who left Ireland in the mid sixth century and crossed the Irish Sea to become first a hermit and later a missionary and founding father based on the tiny island of Iona, which is just to the west of Mull. His community later spread across Scotland and converted north-east England as well, but he was by no means unique: over the next several centuries hermits settled alone or in tiny communities all over western Scotland and further afield too....These adventures were known in Ireland as 'green martydoms' -- to distinguish them from the 'red martyrdom' of being slain, shedding blood for the faith. To leave home and travel out beyond civilization was a martyrdom (the word means 'witness'), death of the ego, a self-giving that seems absolute."

"We do not know very much about the spiritual theology of these early hermits," Maitland continues. "Their lives are lost in legend and story, their physical markers faded or wiped out by the wildness of the places where they dwelt."

One of these hermits was St. Cuthbert, bishop of the monastery on Lindisfarne, a center of Celtic Christianity in the Farne Islands off the Northumbrian coast. A great lover of nature, he issued regulations to his monks for the special protection of Eider Ducks, which are called Cuddy Ducks ("Cuthbert's Ducks") to this day. He retired to live an austere and solitary life on Inner Farne Island in 676, and died there in 687.

Sara Maitland explains that we know more about St. Cuthbert than most other Christian hermits because he was personally known and loved by Bede, author of The Ecclesiastical History of the English People. "But what interested Bede is somewhat different than what interests me," writes Maitland. "So, for example, Bede records that Cuthbert would pray all night standing up to his neck in the frigid waters of the North Sea and, indeed, when he emerged otters would come and warm him with their tongues and fur. This combination of the ferociously ascetic and the miraculous engages Bede, for what he is writing about is the ultimate form of something so obvious to him that he never says anything about what Cuthbert thought he was trying to achieve, nor about the content of those prayers.

"It is not until rather later, from the tenth to twelfth centuries, that we begin to get accounts that attempt to explain what the island hermits were seeking, in the beguiling poetry of the Irish monks:

"Delightful I think it to be in the bosom of an isle, on the peak of a rock, that I might often see there the calm of the sea. That I might see its heavy waves over the glittering ocean, as they chant a melody to their Father on their eternal course. That I might see its smooth strand of clear headlands, no gloomy thing; that I might hear the voice of its wondrous birds, a joyful tune. That I might hear the sound of the shallow waves against the rocks; that I might hear the cry by the graveyard, the noise of the sea. That I might see its splendid flocks of birds over the full-watered ocean; that I might see its mighty wales, greatest of wonders. That I might see its ebb and its flood-tide in their flow; that this might be my name, a secret I tell, "He who turned his back on Ireland." That contrition of heart should come upon me as I watch it; that I might bewail my many sins, difficult to declare. That I might bless the Lord who has power over all, heaven with its pure host of angels, earth, ebb, flood-tide."

Unlike Maitland and the hermit monks she admires, I am not a Christian, and I certainly don't live an isolated life, yet my morning prayers on Nattadon Hill aren't so different from those of the nature-loving peregrini:

Delightful I think it to be in the green hills of Devon, climbing through bracken and blackberries to the granite peaks above, that I might often see the sheep-dotted fields, and the grey tors of Dartmoor beyond. That I might hear the wind singing in the trees, a choir of oak, ash, rowan, and beech; and the bells of the village church; and the bleating lambs; and the hooting of owls in the woods. That I might see this hillside covered in bluebells, stitchwort, and foxgloves, no gloomy thing; and that I might hear the voice of its rooks and its robins, a joyful tune. That I might see the badgers live undisturbed; and the small red deer, shyest of wonders; and watch wild ponies graze in the tall grass as they flow between valley and moor. That I come nameless to this hill, no more, no less than others creatures here, living quietly, gently upon its slopes. That I walk these paths with respect, attentiveness, open eyes, open ears, open heart. That I might bless Mystery within all of us; and my good neighbors, human and nonhuman alike; and the air, the water, the fire, the earth, ebb and flood-tide. Mitakuye oyasin.

Words: The quotes by Sara Maitland are from A Book of Silence (Granta, 2009), which I highly recommend. All rights reserved by the author. Pictures: The last three photographs above are mine, taken here in Chagford: Meldon Hill viewed from Nattadon Hill, a pathway on lower Nattadon, and a very young Dartmoor pony on the village Commons. The photographs of islands in Scottland and north-east England (and their birds and animals) are Creative Commons images. They are identified in the picture captions. (Run your cursor over the images to see them.)

Words: The quotes by Sara Maitland are from A Book of Silence (Granta, 2009), which I highly recommend. All rights reserved by the author. Pictures: The last three photographs above are mine, taken here in Chagford: Meldon Hill viewed from Nattadon Hill, a pathway on lower Nattadon, and a very young Dartmoor pony on the village Commons. The photographs of islands in Scottland and north-east England (and their birds and animals) are Creative Commons images. They are identified in the picture captions. (Run your cursor over the images to see them.)

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 708 followers