Terri Windling's Blog, page 89

August 9, 2017

The unwritten landscape

In her beautiful essay "Isabella's Crag," Alice Starmore describes the relationship between language and place on the Lewis moor in the Outer Hebrides, and how fragile that relationship is in a rapidly changing world:

"Although too insignificant to be named on any map, Creagan Iseabal Mhartainn [Isabella's Crag] is a towering feature of the 'unwritten landscape' -- a rich vocabulary of geographical co-ordinates known, loved and spoken of by generations of the families who spent their summers in the crag's vicinity. Today, I count only a half a dozen people, myself included, who could name that crag and guide you to it. The youngest of us is sixty, so the future of the unwritten language is far shorter than its past: the acumulation of knowledge and respect that engendered it is now de-valued and close to being forgotten, like Isabella herself, for not even the half-dozen knows who she was or when she lived. Yet her modest crag stands as a paradigm for the whole Lewis moor: for its past, present and possible future.

"Over my whole career," writes Starmore, "my greatest and most consistent artistic inspiration has stemmed from the childhood summers I spent on the Lewis moor during the 1950s and 1960s. For six weeks of each year of my childhood, my family moved from our usual home to the ��irigh of our ancestral ge��rraidh (pasture) on the moor just south of Stornoway. I belong to the very last Hebridean generation to take part in this traditional form of transhumance, for the practice had died out by the end of the 1960s.

"For centuries, the custom of transhumance in Lewis was an essential part of life in crofting villages, as arable land was limited. In order to provide enough fodder for the cattle to survive the winter and early spring, it was necessary to take them away to moorland pastures for the summer months so the village pastures could be harvested for winter feed.

"This was especially necessary in the Eye Peninsula, also known as the Point, where my family comes from. Point was a well-populated crofting area with virtually no hill grazing in the immediate district due to its peninsular situation. The summer hill grazing was on the far side of Stornoway, which involved a long march with the cattle through the town and then over hill and burn to the ��irigh.

"In my parents' youth, the men, women and children and animals walked the many miles to their summer pastures, carrying all their essential foodstuffs, clothing and utensils. This was known as An Iomraich (The Flitting).

"By the time I was a child, only the cattle and herders came on foot while we loaded all our chattels, including all domestic pets, in a small lorry hired for the day. We children perched on the top of the load like latter-day dustbowl Okies and headed off to glorious freedom and the joyful company of our little summer community.

"Each village tended to have its own ge��rraidh and quite often they were named after the crofting village, such as Ge��rraidh Shiadair (Shulishader's Pasture). Others were named after the original long-gone owner of the first ��irigh. For example, ��irigh an t-Sagairt (the Priest's Sheiling) was still known long after priests had departed these Presbyterian shores. Many more were named after a feature of the landscape, such as ��irigh a' Chreagain (the Sheilings at the Crag), or sometimes even a measure of distance such as ��irigh Fad As (the Faraway Sheiling).

"Place names were of great importance to us; as well as having a romance all of their own, they were a means of communicating where we were going or where we had been on our wanderings. My father would describe the journeys of his 1920s boyhood from Bayble in Point to the very furthest grazing at Loch Dubh nan Stearnag (the Black Loch of the Terns) in the heart of the Lewis moor. After walking twelve miles, they stopped to rest overnight at ��irigh na Beiste (the Animal Sheiling) before going through ��irigh Leitir (the Sheilings on the Slope) and then on to their own pasture called ��irigh Sgridhe at the foot of the Beinn a' Sgridhe in the Barvas Hills.

"My father's journey was epic by Lewis standards, and the pastures he passed through to get there were equivalent to the main towns on a road map. But the unwritten landscape held a treasury of terms with which to describe our journeys. My father could name every little feature he stopped at or passed by. Likewise, we children could tell our parents exactly where we were going, or where we had been."

"Knowing the landscape gave us the freedom of it. Our parents could get on with their day and trust that we would not get lost or drown in the vast network of lochs, burns and bogs that were all ours to explore....

"We lived on the border between micro and macro -- our detailed observations were balanced against the broad sweep of the open moor. Constant unsupervised exploration, with no time restrictions, allowed our imaginations to run free. We observed facts of nature, but it was also easy to believe in kelpies and shape-shifters when walking the moor in the late evening."

Outdoor life on the summer pasture contributed "to an intimate knowledge of the place, its history, and all the life within it. Though as a small child I was free of the cares of adults, it was obvious that everyone was very happy on the moor, and as the time approached to return home it was difficult not to be sad. Latterly, there were just three families on our pasture and none of us wanted to be the first or last to leave. We therefore tried to co-ordinate our flitting so that we would all leave on the same day. Alexina, the sky reader, gave voice to all our feelings about the ge��rraidh when she admitted one day, when we were packing up to go, that she was extremely sad at the thought of 'f��g��il an ge��rraidh na aonar' (leaving the pasture in loneliness).

"To us it had a spirit, a heart and soul, just as we had ourselves."

Words: The passage above is from "Isabella's Crag: Language, Landscape and Life on the Lewis Moor" by Alice Starmore (EarthLines magazine, May 2012); highly recommended. All rights reserved by the author.

Pictures: These photographs are from my recent journey to the Isle of Skye, which is south-east of Lewis in the Inner Hebrides. You can see Alice Starmore's photographs of the Lewis moor here, from her lovely exhibition "Mamba."

Related posts: "The Enclosure of Childhood" and "Finding the Way to the Green."

A language of land and sea

While thinking about the stories and language of place, I was reminded of the following passage from Love of Country: A Hebridean Journey by Madeleine Bunting. I read Bunting's book on my recent journey from Devon to the Isle of Skye, where it proved a fine introduction to a landscape steeped in Gaelic history, culture, and folklore.

"Every nation," she writes, "has its lost histories of what was destroyed or ignored to shape its narrative of unity so that it has the appearance of inevitability. The British Isles with their complex island geography have known various configurations of political power. Gaelic is a reminder of some of them: the multinational empires of Scandinavia, the expansion of Ireland, and the medieval Gaelic kingdom, the Lordship of the Isles, which lost mainland Scotland, and was ultimately suppressed by Edinburgh. The British state imposed centralization, and insisted on English-language education. Only the complex geography of islands and mountains ensured that Gaelic survived into the 21st century.

"What would be lost if Gaelic disappeared in the next century, I asked, when I visited hospitable [Lewis] islanders who pressed me with cups of tea and cake. There is a Gaelic word, cianalas, and it means a deep sense of homesickness and melancholy, I was told. The language of Gaelic offers insight into a pre-industrial world view, suggested Malcolm Maclean, a window on another culture lost in the rest of Britain. As with any language, it offers a way of seeing the world, which makes it precious. Gaelic's survival is a matter of cultural diversity, just as important as ecological diversity, he insisted. It is the accumulation of thousands of years of human ingenuity and resilience living in these island landscapes. It is a heritage of human intelligence shaped by place, a language of the land and sea, with a richness and precision to describe the tasks of agriculture and fishing. It is a language of community, offering concepts and expressions to capture the tightly knit interdependence required in this subsistence economy.

"Gaelic scholar Michael Newton points out how particular words describe the power of these relationships intertwined with place and community. For example, d��thchas is sometimes translated as 'heritage' or 'birthright,' but conveys a much richer idea of a collective claim on the land, continually reinforced and lived out through the shared management of the land. D��thchas grounds land rights in communal daily habits and uses of the land. It is at variance with British concepts of individual private property and these land rights received no legal recognition and were relegated to cultural attitudes (as in many colonial contexts). Elements of d��thchas persist in crofting communities, where the grazing committees of the townships still manage the rights to common land and the cutting of peat banks on the moor. Crofting has always been dependent on plentiful labor and required co-operation with neighbors for many of the routine tasks, like peasant cultures across Europe, born out of the day-to-day survival in a difficult environment.

"The strong connection to land and community means that 'people belong to places rather than places belong to people,' sums up Newton. It is an understanding of belonging which emphasizes relationships, of responsibilities as well as rights, and in return offers the security of a clear place in the world."

Bunting also notes that "Gaelic's attentiveness to place is reflected in its topographical precision. It has a plentiful vocabulary to describe different forms of hill, peak or slope (beinn, stob, d��n, cnoc, sr��n), for example, and particular words to describe each of the stages of a river's course from its earliest rising down to its widest point as it enters the sea. Much of the landscape is understood in anthropomorphic terms, so the names of topographical features are often the same as those for parts of the body. It draws a visceral sense of connection between sinew, muscle and bone and the land. Gaelic poetry often attributes character and agency to landforms, so mountains might speak or be praised as if they were a chieftain; the Psalms (held in particular reverence in Gaelic culture) talk of landscape in a similar way, with phrases such as the 'hills run like a deer.' In both, the land is recognized as alive.

"Gaelic has a different sense of time, purpose and achievement. The ideal is to maintain an equilibrium, as a saying from South Uist expresses it: Eat bread and weave grass, and then this year shall be as thou wast last year. It is close to Hannah Arendt's definition of wisdom as a loving concern for the continuity of the world."

And, I would add, to the Dineh (Navajo) concept of h��zh��, or Walking in Beauty.

Words: The poem in the picture captions is by Kathleen Jamie, from the Scottish Poetry Library. I highly recommend her poetry volumes, and her two gorgeous essay collections: Findings and Sightlines. The passage above is from Love of Country by Madeleine Bunting (Granta, 2016), also recommended. All rights to the prose and poetry in this post is reserved by the authors. Pictures: Sheep in the Fairy Glen, near Uist on the Isle of Skye.

August 8, 2017

The landscape of story

From "The Dreaming of Place" by Hugh Lupton:

"The ground holds the memory of all that has happened to it. The landscapes we inhabit are rich in story. The lives of our ancestors have contributed to the shape and form of the land we know today -- whether we are treading the cracked cement of a deserted runaway, the boundary defined by a quickthorn hedge, the outline of a Roman road or the grassy hump of a Bronze Age tumulus. The creatures we share the landscape with have made their marks, too: their tracks, nesting places, slides and waterholes. And beyond the human and animal interactions are the huge, slow geological shapings that have given the land its form. Every bump, fold and crease, every hill and hollow is part of a narrative that is both human and prehuman. And as long as men and women have moved over the land these narratives have been spoken and sung.

"This sense of story being held immanent in landscape," Lupton suggests, " is most clearly defined in the belief systems of the Aboriginal peoples of Australia. In Native Australian belief everything that is not 'here and now' is described as having gone 'into the dreaming.' The Aborigines believe that the tangled skein of remembered experience, history, legend and myth that constitutes the past -- that is invisible to the objective eye or the camera -- has not gone away. It is, rather, implicit in the place where it happened, a potentiality. It is a living memory that is held between a place and its people. It is always waiting to be woken by a voice.

"I remember the Irish storyteller Eamon Kelly once telling me that in the parish of County Clare where he grew up, every field had a name, and every field name was associated with a story. To walk from one end of the parish to the other was to walk through a landscape of story. It occurred to me that the same was probably once true for any parish in Britain.

"But today we are forgetting our stories. We have been forgetting them for a long time. Few of us live in the same landscape as our grandparents. The deep knowledge that comes from long familiarity has become a rarity. Places are glimpsed through the windows of cars and trains. Maybe, occasionally, we stride through them.

"What does it mean for a culture to have lost touch with its dreaming? What can we do about it?

"It seems to me that as writers, artists, environmentalists, parents, teachers and talkers, one of our practices should be to enter the Dreaming, that invisible, parallel worl, and salvage our local stories. We need to re-charge the landscape with its forgotten narratives. Only then will it regain the sacred status it once possessed. This might involve research into local history, conversations with elders in the community, exploration of regional folktales, ballads and myths...

"And then an intuitive jump into Imagination."

The passage by British storyteller, folklorist, and novelist Hugh Lupton is from EarthLines magazine (Issue 2, August 2012). The poem in the picture captions is by Scottish poet Judith Taylor, first published in The Interpreter's House (Issue 59, 2015). All rights reserved by the authors. For a related post on place and the importance of local stories, see "Wild Neighbors."

The passage by British storyteller, folklorist, and novelist Hugh Lupton is from EarthLines magazine (Issue 2, August 2012). The poem in the picture captions is by Scottish poet Judith Taylor, first published in The Interpreter's House (Issue 59, 2015). All rights reserved by the authors. For a related post on place and the importance of local stories, see "Wild Neighbors."

August 7, 2017

Tunes for a Monday Morning

My apologies for being away for so long, dear Readers. I was in high spirits just a month ago, after visiting friends on the Isle of Skye -- but then life turned around and clobbered us from an unexpected direction. (For family privacy sake, I can't be more explicit.) Now we're picking ourselves up off the ground, a bit bruised but eager to return to the things that shine a light in hard times: books and art and puppets and theatre, and the community (both near and far) that sustains us.

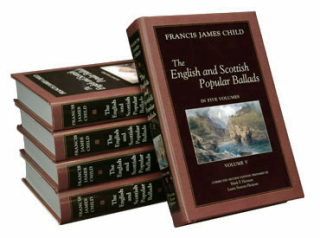

I'm back in the studio today, with Child Ballads by Anais Mitchell & Jefferson Hamer on the stereo: a lovely reminder of the folklore traditions that lie at the roots of the Mythic Arts field. When the album first appeared in 2013, there were listeners on this side of the Atlantic nonplused to hear classic British ballads sung in American accents -- forgetting that such songs made their way over to the New World with Anglo-Scots immigrants and are part of America's folk heritage too. Francis Child, the famous ballad collector, was an American himself: a scholar of literature, language and folklore at Harvard University. (For more information on the man, and on the ballads, go here.)

I'm back in the studio today, with Child Ballads by Anais Mitchell & Jefferson Hamer on the stereo: a lovely reminder of the folklore traditions that lie at the roots of the Mythic Arts field. When the album first appeared in 2013, there were listeners on this side of the Atlantic nonplused to hear classic British ballads sung in American accents -- forgetting that such songs made their way over to the New World with Anglo-Scots immigrants and are part of America's folk heritage too. Francis Child, the famous ballad collector, was an American himself: a scholar of literature, language and folklore at Harvard University. (For more information on the man, and on the ballads, go here.)

Above: Mitchell & Hamer perform an unusual version of "Tam Lin," Child Ballad #39. This variant omits the role of the Fairy Queen in stealing Tam Lin away, but includes a part of the song often elided in other renditions: Janet's intent to get rid of her unborn child (by the use of magical, poisonous plants) until Tam Lin dissuades her.

Below: Mitchell & Hamer perform "Willie's Lady," Child Ballad #6.

Above: Mitchell performs "Clyde Waters" (Child Ballad #216) on the Prairie Home Companion program, backed up by the great Chris Thile on mandolin and Sarah Jarosz on vocals, among others.

Below: a song from Mitchell's extraordinary folk opera Hadestown, based on the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice. Hadestown first appeared as a concept album in 2010, and was turned into a theatrical production by New York Theatre Workshop in 2016.

Although written almost a decade ago, Mitchell's Hadestown song "Why We Build the Wall" is especially relevant today, in the age of Trump. And so, sadly, is the final song: "Deportee" by Woody Guthrie (from 1948), which Mitchell performed a few months ago with Austin Nevins.

July 23, 2017

Myth & Moor update

I'm afraid I'm going to be out of the studio and off-line a little longer. I'd like to be back by the end of the week, if life permits -- but I've been living in a one-day-at-a-time kind of way, at the mercy of things beyond my control. As we all are really, every moment of our lives, but sometimes that fact is starker than others.

Thank you for your patience, and your messages of support. I hope your summer has been richly creative.

"It is good to love many things, for therein lies the true strength, and whosoever loves much performs much, and can accomplish much, and what is done in love is well done."

- Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890)

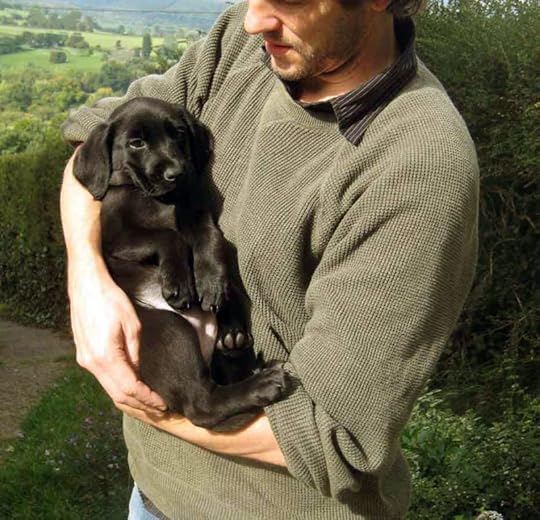

Happy Birthday to our Tilly

"People seem able to love their dogs with an unabashed acceptance that they rarely demonstrate with family or friends. The dogs do not disappoint them, or if they do, the owners manage to forget about it quickly. I want to learn to love like this, the way we love our dogs, with pride and enthusiasm and a complete amnesia for faults. In short, to love others the way our dogs love us."

- Ann Patchett (''This Dog's Life'')

Tilly's birthday is tomorrow, but we'll be away so I'm posting this today. She's eight years old, and continues to be the four-footed heart of our household.

July 17, 2017

Myth & Moor update

I'm still off-line dealing with some bears, I'm afraid. I'll be back to Myth & Moor just as soon as I can. Thank you so much for your patience.

Art by Julianna Swaney

July 9, 2017

Myth & Moor update

After writing about the small things that can disrupt one's work, I'm afraid a larger thing has come up that will keep me out of the studio on Monday, possibly longer. Please bear with me (and excuse the pun); I'll be back on a regular Myth & Moor schedule again just as soon as I can be.

For the growing list of people awaiting email from me, thank you for your patience. I haven't forgotten you.

Art above by John Bauer (1882-1918).

Embracing the Bear

First posted in the winter of 2014:

I've long used the term "embracing the bear" for those moments when I'm moving forward into something I fear, but don't want fear to stop me; thus I was intrigued to encounter the same phrase in Terry Tempest William's An Unspoken Hunger, where it has a slightly different, but related, meaning. In a gorgeous little essay on women and bears, Williams includes a description of Marian Engle 's Bear, a highly unsual, memorable novel which portrays a woman and a bear "in an erotics of place":

"It doesn't matter whether the bear is seen as male or female," says Williams. "The relationship between the two is sensual, wild.

wild.

"The woman says, 'Bear, take me to the bottom of the ocean with you, Bear, swim with me, Bear, put your arms around me, enclose me, swim, down, down, down, with me.'

" 'Bear,' she says suddenly, 'come dance with me.'

"They make love. Afterwards, 'She felt pain, but it was a dear sweet pain that belonged not to mental suffering, but to the earth.'

William writes that she, too, "has felt the pain that arises from a recognition of beauty, pain we hold when we remember what we are connected to and the delicacy of our relations. It is this tenderness born out of connection to place that  fuels my writing. Writing becomes an act of compassion toward life, the life we often refuse to see because if we look too closely or feel too deeply, there may be no end to our suffering. But words empower us, move us beyond our suffering, and set us free. This is the sorcery of literature. We are healed by our stories.

fuels my writing. Writing becomes an act of compassion toward life, the life we often refuse to see because if we look too closely or feel too deeply, there may be no end to our suffering. But words empower us, move us beyond our suffering, and set us free. This is the sorcery of literature. We are healed by our stories.

"By undressing, exposing, and embracing the bear, we undress, expose, and embrace our authentic selves. Stripped free from society's oughts and shoulds, we emerge as emancipated beings. The bear is free to roam."

"We are creatures of paradox, women and bears, two animals that are enormously unpredictable, hence our mystery," Williams continues. "Perhaps the fear of bears and the fear of women lies in our refusal to be tamed, the impulses we arouse and the forces we represent....As women connected to the earth, we are nurturing and we are fierce, we are wicked and we are sublime. The full range is ours. We hold the moon in our bellies and fire in our hearts. We bleed. We give milk. We are the mothers of first words. These words grow. They are our children. They are our stories and our poems."

Credits: The sublime images above are by the Russian surrealist photographer Katerina Plotnikova, based in Moscow; all rights reserved by the artist. The pen-and-ink drawings are Victorian illustrations, artists unknown. The text above is from An Unspoken Spoken Hunger: Stories from the Field by Terry Tempest Willians (Pantheon, 1994); all rights reserved by the author.

Other recommended bear fiction: The Red Garden by Alice Hoffman (the woman-bear relationship in this book completely slays me), The Bear and the Nightingale by Katherine Arden, Tender Morsals by Margo Lanagan, East by Edith Pattou, Snow White and Rose Red by Patricia C. Wrede, Ice by Sarah Beth Durst, and Her Frozen Wild by Kim Antieau. Short fiction: "The Bear Outside" by Tom Hirons, "Sleeping With Bears" by Theodora Goss, "Else This, Nothing Ever Grows" by Sylvia V. Linsteadt, "Bear's Bride" by Johanna Sinisalo (in The Beastly Bride), "The Woman Who Loved a Bear" by Jane Yolen (in Once Upon a Time), "Brother Bear" by Lisa Goldstein (in Ruby Slippers, Golden Tears), and "The Brown Bear of Norway" by Isobel Cole (in Black Thorn White Rose). For magical poetry, I particularly love "The Bear's Daughter" by Theodora Goss and "An Embroidery" by Denise Levertov. Jackie Morris' picture book The Ice Bear is a thing of beauty; and Michel Pastoureau's The Bear: History of a Fallen King is fascinating. Other recommendations welcome.

More ursine symbology, folklore, and art can be found in "Following the Bear" (winter 2014).

July 7, 2017

The small things

I was up much later that usual on Wednesday night, waiting for my husband to return from a work gig in London -- a simple journey that turned into a nine hour ordeal due to multiple train failures on the way. The whole transport system was in chaos that night: every single train from Paddington Station cancelled; and then Waterloo Station, where the weary travellers were directed, paralyzed by breakdowns as well. He finally got home after one in the morning, and I couldn't sleep until he'd made it back safely.

Public transit frustrations are an ordinary part of modern life, of course (at least here in Britain, where our rail system is a disgrace) -- so why am I telling you about it? Because these small, everyday, uncontrollable events affect those of us in the arts with long-term health conditions disproportionately. After losing just a few hours of sleep, I woke up on Thursday morning to a spoon drawer close to empty, my studio schedule disrupted once again. This was not a major problem, of course. I rested up, did some work from home, and I'm back in the studio this morning, catching up on the tasks that I'd missed. My work plans are often affected by these kinds of things, so small and common that they're rarely mentioned....

But today I decided to talk about it. Shining a light on the difficulties of the art-making process can be as important as noting the things that inspire us or help us progress -- including the particular challenges faced by artists with disabilities or medical conditions.

Most healthy people can understand, and empathize with, the disruptive nature of a large medical crisis; but the daily effects of life's random ups and downs on those of us with limits of strength are perhaps less obvious. These small things -- trivial and constant -- chip away at our work time, our output, our income, and sometimes even our self-esteem, as we watch healthier colleagues speed ahead of us, unencumbered by the weight that we carry.

The saving grace comes each and every time that a friend or colleague stops, looks back, sees us struggling on, and extends a helping hand. That happens often too. The trials of illness are many; but so are the blessings, which shine bright as the moon.

The second reason I have chosen to write about this is to express my solidarity with all of the writers, painters, and other artists out there coping with various medical conditions: determined to keep working, keep creating, keep contributing to the social good, but not always able to control exactly how and when. Viewed from the outside, our work pace can seem slow, or flakey, or lazy compared to the pace and output of those with reliable strength -- yet as a group, we tend to be more self-disciplined and hard-working, not less; for when energy is limited, you quickly learn to make good and efficient use of whatever work time the body allows.

This wasn't the post I was planning for today. This isn't the week I was planning to have. But this too is part of the artists' life. This too is part of the discussion.

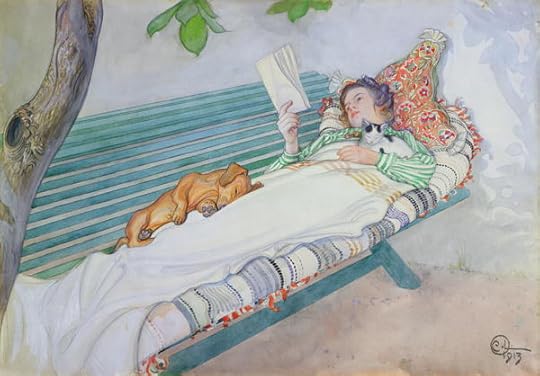

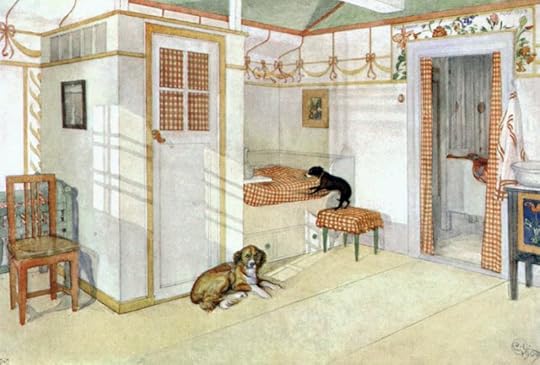

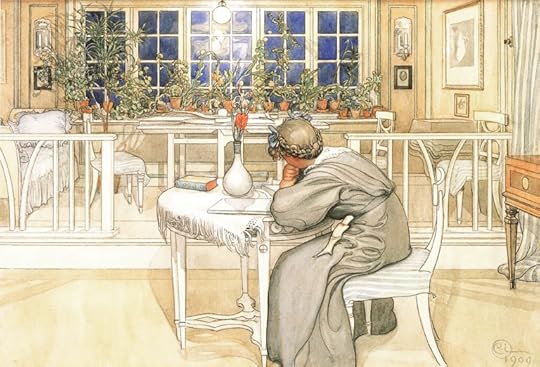

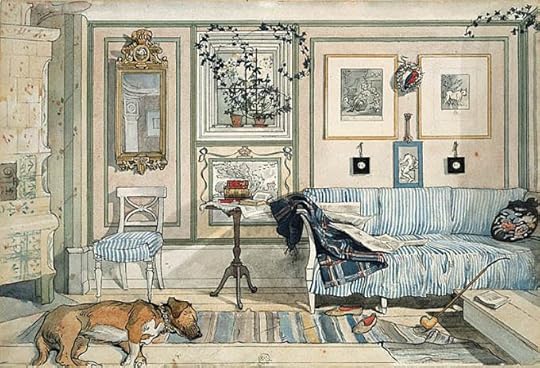

Art above: Four paintings by Carl Larsson (1853-1919). Related posts: On blogging (and spoons), Every illness is narrative, and The beauty of brokenness.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 708 followers