Terri Windling's Blog, page 27

September 25, 2020

Telling the hard stories

In "Fairy Tale Logic: A Conversation With Alice Hoffman," the author discusses why she drew on folkloric elements to tell a story about the Holocaust in her recent novel The World That We Knew:

"I grew up read��ing fairy tales and, as a kid, I always pre��ferred them to oth��er children���s lit��er��a��ture, because I felt like they told the truth. I felt like sym��bol��i��cal��ly, they got to the deep��est emo��tion��al truth. That feel��ing about fairy tales has stayed with me, and also the feel��ing that these were the orig��i��nal sto��ries, told by grand��moth��ers to grand��chil��dren, to intro��duce them to the world���������all that���s good and all that���s bad, what to be wary of and how to live your life. The oth��er part of it, though, was that there have been so many nov��els writ��ten about the Holo��caust, and I real��ly haven���t read any of them. I have read a ton of lit��er��a��ture on the Holo��caust, but not nov��els. The sto��ry of the Holo��caust is so illog��i��cal and irra��tional. It makes no sense. Why would peo��ple act this way? It���s inhu��mane. It just defies log��ic. The only way that I felt I could tell it was to use fairy-tale log��ic to try to make sense of a world where noth��ing made sense."

In an earlier piece, from 2004, Hoffman also defended the value of fairy tales and why we are drawn to tell and re-tell them:

"Fairy tales tell two stories: a spoken one and an unspoken one. There is another layer beneath the words; a riddle about the soul and its place in the greater canvas of humanity. Surely every child who reads Hansel and Gretel feels that he or she, too, is on a perilous path, one that disappears and meanders, but one that must be navigated, like it or not. That path is childhood: a journey in which temptations will arise, greed will surface, and parents may be so self-involved that they forget you entirely.

"It has long been my belief that writers of fiction fall into two categories: those who write to explain their lives, and those who write to escape them. Both, I suppose are looking for some 'truth' about their experiences, but the former are shackled by their worlds; the latter are free to imagine new ones. Do people choose the art that inspires them -- do they think it over, decide they might prefer the fabulous to the real? For me, it was those early readings of fairy tales that made me who I was as a reader and, later on, as a storyteller."

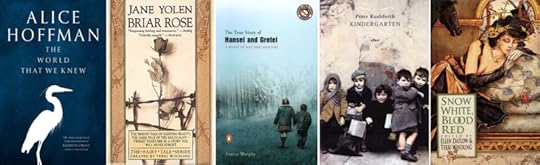

Hoffman's World War II novel, The World That We Knew, follows a trail blazed by several previous works of Holocaust literature making use of fairy tale themes: Jane Yolen's novel Briar Rose (1992), Lisa Goldstein's short story "Breadcrumbs and Stones" (published in Snow White, Blood Red, 1993), and Louise Murphy's novel The True Story of Hansel and Gretel (2003) in particular -- as well as Peter Rushford's Kindergarten (1976), a too-little-known novel for young readers centered on a fairy tale artist with a Holocaust history.

In listing these antecedents to Hoffman's book, I don't mean to imply that her work is derivative, for it is the nature of fairy tales to be retold, and the nature of fantasy books to be in conversation with each other -- in fact, it's one of the hallmarks of our field. Whether or not Hoffman is familiar with the stories I've listed, a certain number of her readers will be, and it is through readers as well as through writers and their texts that the Great Conversation continues.

Ellen Kushner and I were recently talking about this aspect of fantasy literature as she was preparing her talk for the launch of the Centre for Fantasy and the Fantastic at the University of Glasgow. We can read fantasy books as stand-alone works, of course; and, if the tale has been well constructed, the experience will be a satisfying one; but to fully appreciate the best works in our field requires knowing something of its history. Fantasy fiction is rarely (if ever) sui generis; it exists within the context of a rich and varied tradition, written in reponse to, or against, what has come before. It is an art form that does not depend on novelty for effect, but constantly references older stories and tropes, re-fashioning them into new shapes.

Fantasy writers, said Lloyd Alexander (as quoted in last Thursday's post), "draw from a common source: the 'Pot of Soup,' as Tol��kien calls it, the 'Cauldron of Story,' which has been simmering away since time immemorial. The pot holds a rich and fascinating kind of mythological minestrone. Almost everything has gone into it, and almost any�� thing is likely to come out of it: morsels of real history -- spiced�� and spliced -- with imaginary history, fact and fancy, daydreams and nightmares. It is as inexhaustible as those legendary vessels that could never be emptied."

In the contemporary fantasy field, Tolkien's 'Pot of Soup' contains not only the myth cycles, epics, and heroic romances he drew upon for The Lord of the Rings but also fantastical stories of a more recent vintage, including those by Tolkien himself. Themes, characters, imaginary landscapes, evocative metaphors and arresting images from works produced in the 19th and 20th centuries now swirl in that pot, flavouring the stories of writers today in ways both obvious and subtle.

In some fields, "influence" is a suspect thing, as though influence equals imitation. (It doesn't, and shouldn't.) Our field, by contrast, celebrates the influence of older stories and older works of art, bringing the old and the new into dialogue. For example: Ursula Le Guin's Earthsea cycle is, among many other things, a response to J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis' work: a conversation about what magic is, what power is, and what an imaginary world might be like if it grew from nonWestern mythic traditions. Stardust by Neil Gaiman and Charles Vess is, among many other things, a lively conversation with Hope Mirrlees' Lud-in-the-Mist and Lord Dunsany's The King of Elfland's Daughter. Snow White, Blood Red, the fairy tale anthology Ellen Datlow and I published back in 1993, was a direct response to Angela Carter's The Bloody Chamber (1979) and Tanith Lee's Red as Blood (1983); just as The Starlit Wood, edited by Navah Wolfe and Dominik Parisien (2016), is now in conversation with us all.

Although I've savoured Hoffman's work since her very first novel (Property Of, 1977), I haven't yet read The World That We Knew. You have to be ready to enter the hard stories, and I haven't been ready until now. As I turn through its pages, I will hear the whispered voices of Jane's Briar Rose, Lisa's "Breadcrumbs and Stones," Louise Murphy's The True Story of Hansel and Gretel and Rushford's Kindergarten, along with the echoes of fairy tales told and retold down through the centuries. Knowing the antecedents, the lineage, the tradition that Hoffman is working in will add to, not diminish, my appreciation of the book she's created.

In her fine essay collection Touch Magic: Fantasy, Folklore and Faerie in the Literature of Childhood, Jane Yolen writes:

"We have spent a good portion of our last decades erasing the past. The episode of the gas ovens is closed, wrapped in the mist of history. It is as if it never happened. At the very least, which always surprises me, it is considered a kind of historical novel, abstract and not particularly terrifying.

"It is important for children to have books that confront the evils and do not back away from them. Such books can provide a sense of good and evil, a moral reference point. If our fantasy books are not strong enough -- and many modern fantasies shy away from asking for sacrifice, preferring to profer rewards first as if testing the faerie waters -- then real stories, like those of Adolf Hitler's evil deeds, will seem so much slanted news, not to be believed."

It is important for adult readers to have such books as well, as the daily news keeps reminding us.

I am grateful to the writers who tell the hard stories. And I am grateful to be part of the conversation.

Words: The passages above are quoted from "Fairy Tale Logic: A Conversation with Alice Hoffman" by Jamie Wendt (Jewish Book Council: PB Daily, August 31, 2020); "Sharpening an imagination with the hard flint of fairy tale" by Alice Hoffman (The Washington Post, April 4, 2004); "High Fantasy and Heroic Romance" by Lloyd Alexander (Horn Book, Dec. 16, 1971); and Touch Magic by Jane Yolen (Philomel, 1981; August House, expanded edition, 2000). All rights reserved by the authors.

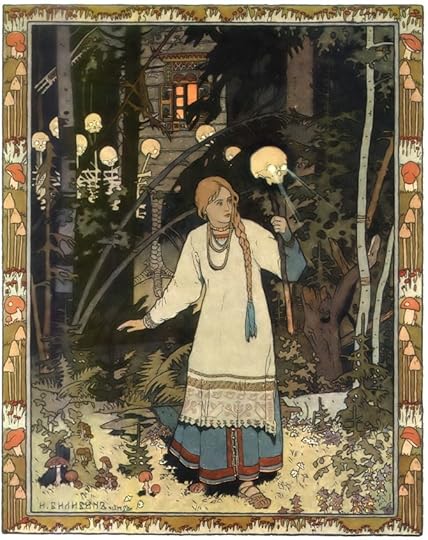

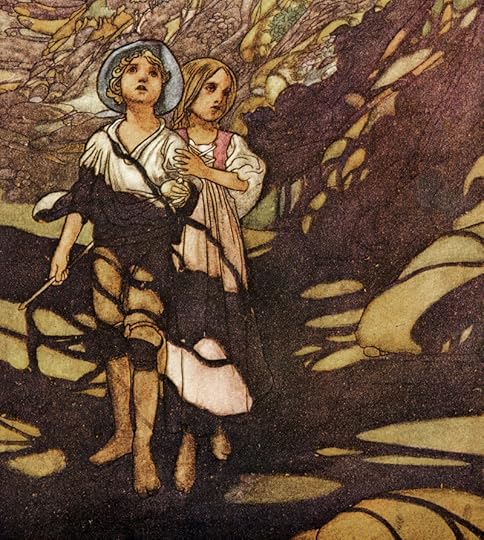

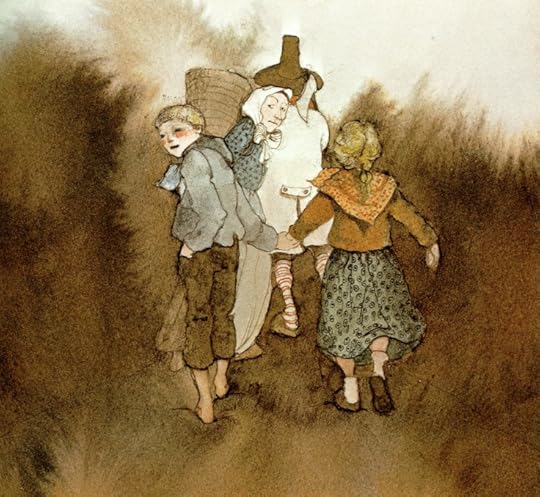

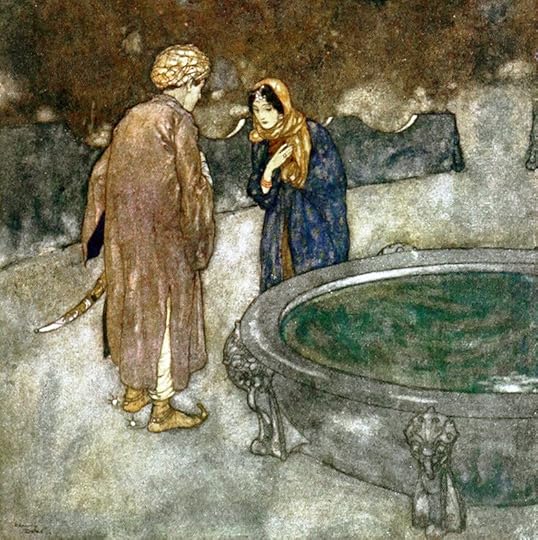

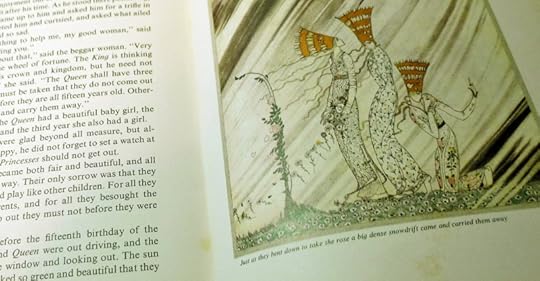

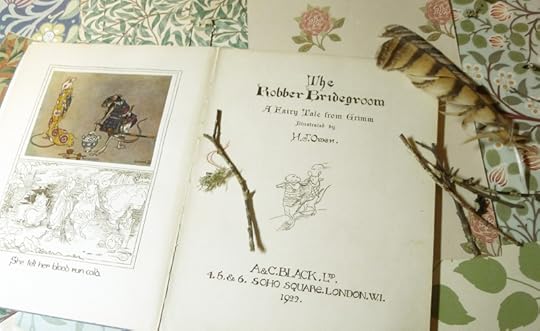

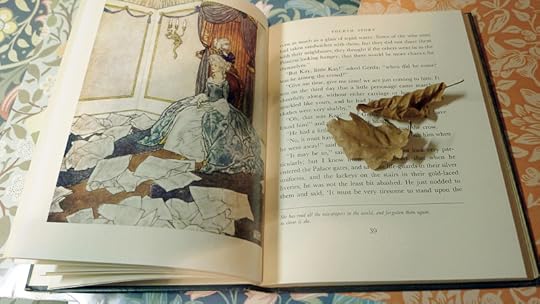

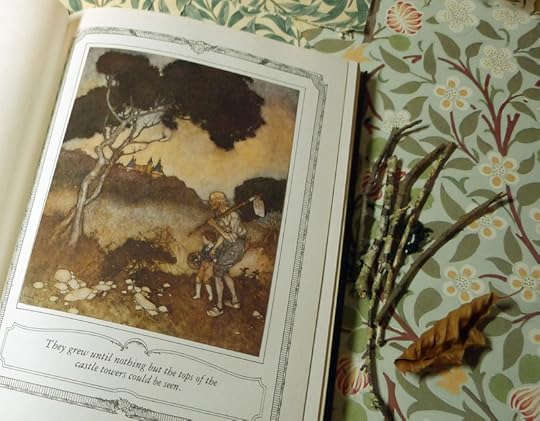

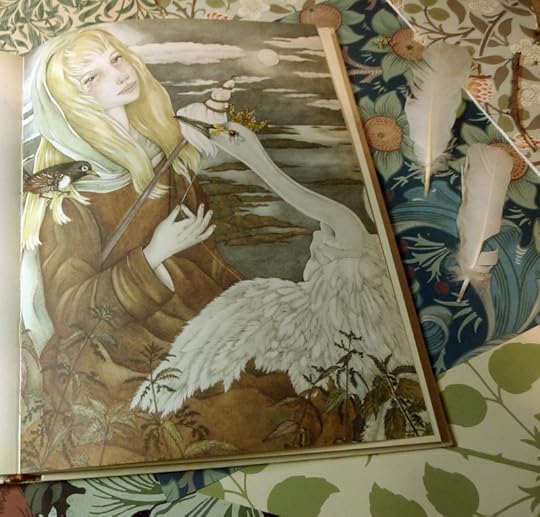

Pictures: "Vasilisa" by Ivan Bilibin, "Hansel and Gretel" by Charles Robinson, "Hansel and Gretel" and "The Legend of Rosepetal" by Lisbeth Zwerger, an illustration for "The Arabian Nights" by Edmund Dulac, and "Snow White" and "Rapunzel" by Trina Schart Hyman. All rights to the contemporary works reserved by the artists.

Related reading, on the subject of influence and tradition: "On finding your voice," Jonathan Lethem's "The Ecstasy of Influence, and "In the Tradition" by Michael Swanwick, which can be found in his book The Postmodern Archipelago (1997), and in The Year's Best Fantasy & Horror, Volume 8 (1995).

September 24, 2020

The only real story

From "Knowing Our Place" by Barbara Kingsolver:

"In the summer of 1996 human habitation on earth made a subtle, uncelebrated passage from being mostly rural to being mostly urban. More than half of all humans now live in the cities. The natural habitat of our species, then, officially, is steel, pavements, streetlights, architecture, and enterprise -- the hominid agenda.

"With all due respect to the wondrous ways people have invented to amuse themselves and one another on paved surfaces, I find this exodus from the land makes me unspeakably sad. I think of children who will never know, intuitively, that a flower is a plant's way of making love, or what silence sounds like, or that trees breathe out what we breathe in....

"Barry Lopez writes that if we hope to succeed in the endeavor of protecting natures other than our own, 'it will require that we reimagine our lives....It will require of many of us a humanity that we've not yet mustered, and a grace we were not yet aware we desired until we had tasted it.'

"And yet no endeavor could be more crucial at this moment. Protecting the land that once provided us with our genesis may turn out to be the only real story there is for us. The land still provides our genesis, however we might like to forget that our food comes from dank, muddy earth, and that the oxygen in our lungs was recently inside a leaf, and that every newspaper or book we pick up...is made from the hearts of trees that died for the sake of our imagined lives. What you hold in your hands [when you hold a book] is consecrated air and time and sunlight and, first of all, place. Whether we are leaving it or coming into it, it's here that matters, it is place. Whether we understand where we are or don't, that is the story: To be here or not to be.

"Storytelling is as old as our need to remember where the water is, where the best food grows, where we find our courage for the hunt. It's as persistent as our desire to teach our children how to live in this place that we have known longer than they have. Our greatest and smallest explanations for ourselves grow from place, as surely as carrots grow from dirt. I'm presuming to tell you something that I could not prove rationally but instead feel as a religious faith. I can't believe otherwise.

"A world is looking over my shoulder as I write these words; my censors are bobcats and mountains. I have a place from which to tell my stories. So do you, I expect. We sing the song of our home because because we are animals, and an animal is no better or wise or safer than its habitat and its food chain. Among the greatest of all gifts is to know our place."

I agree with Barbara that telling tales of the land and of the more-than-human world is crucial in these increasingly urbanized times...and yet, there is nature to be found in the city too, and folklore, and magic, and animal life, and numinous stories worth the telling.

Go here for a previous post on the magic of cities (and the early Urban Fantasy genre).

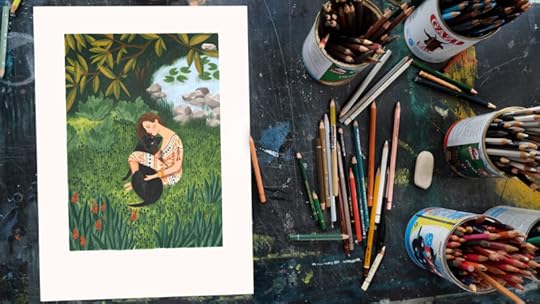

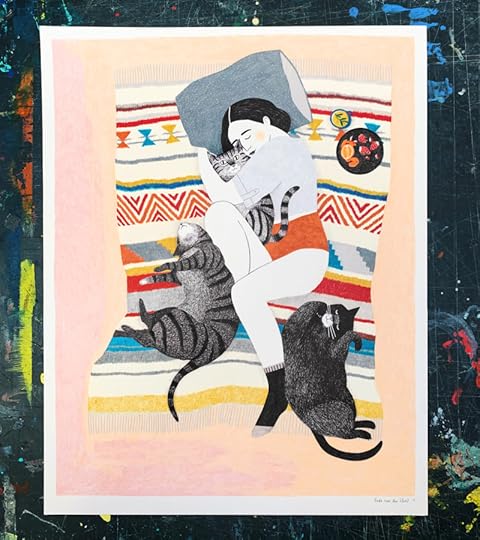

The imagery today is by Lieke van der Vorst, an illustrator based in the Netherlands. She studied graphic design at Sint Lucas, illustration at the Sint Joost Art Academy, and now creates dreamlike imagery inspired by her love of animals, plants, gardens, cookery, and the wild world.

"I grew up in Kaatsheuvel, a little village in the southern part of the Netherlands," she says. "Every summer my parents would pack up our De Waard tent and we would drive thirteen hours to Provence, France to camp among the lavender fields. These times spent in nature have had a strong influence on my life and work; and being kind to animals and the environment is an important part of my vision. I use my illustrations to try to make a positive impact on the world, while practicing green living as much as possible."

Please visit the artist's website or Instagram page to see more of her work.

The passage quoted above is from "Knowing Our Place" by Barbara Kingsolver, published in Small Wonder: Essays (HarperCollins, 2002). All rights to the text and art above reserved by the author and artist.

September 23, 2020

The landscape of story

From "The Right Place for Love" (Of Landscape and Longing) by Carolyn Servid, who grew up in India but found her heart's home on the wild coast of Alaska:

"In his book The Land, theologian and historian Walter Brueggemann recognizes a human yearning for place -- and acknowledges that yearning as a primary human hunger. I think of it as an instinctual desire and need for my own habitat, a word primarily used to describe an ecological home range that allows a given species to thrive. We usually don't think of ourselves as the sample species, but I'd like to consider the notion of habitat in a human context for a moment. For those of us who use the English language, it is interesting to note that habitat is related to a cluster of other words -- habit, ability, rehabilitate, inhabit, and prohibit. They all come from a common Latin root, habere, and spin off a fundamental concept of relationship: 'to hold, hence to occupy or possess, hence to have.' They constitute a family of words that ground us by describing where we live, how we live, what we are able to do, how we heal ourselves, what our connections are to the landscape around us, what the boundaries are for our behavior. Together, they offer a set of parameters that might allow us to thrive in a place we think of as home.

"Given the biological evidence that the earth is our home, it's not difficult or even particularly imaginative to assert that we in Western societies have been living for centuries in a perpetual state of homesickness. We have worked hard -- somewhat blindly and somewhat successfully -- to disconnect ourselves from the source of our being. Our efforts have only partially succeeded because we cannot, in fact, separate ourselves from the fundamental truth of the context of our lives....The human hunger for place that Brueggemann speaks of might be thought of as a longing to be reconnected to the very source of our being. That longing is also a hunger for love -- for the nurturing that a home place provides, for its familiarity, its comfort, its human community, is natural community, its light and landscape. I believe, too, that our hunger for place is a yearning for a sense of the holy, for home ground sacred enough to sustain our faith, sacred enough that we will not violate it, sacred enough that our commitment to its holiness will not falter."

Servid returns to the theme in a second essay, "The Distance Home":

"Homesick, we say, when our hearts reach back to those places that have embraced us, our language allowing us the truth that when we're away from them we feel unhealthy, ill at ease. Sentimentality, another voice says, urging me to ignore the bonds that form between the human heart and peculiarities of the earth. But perhaps the sentiments we attach to place are more natural to us than we know. Perhaps what is at work is an instinctual desire, a need, for a set of specific details to help determine our bounds, our own habitat, a particular context in which we can come to know how to best live our individual lives, how best to survive not only within the human community, but in a distinct region of the larger natural community that is our only real home."

For me, "home" is powerful concept, attached to the land I live on as much as to the family and community I live within, and much of my creative work is nurtured by the specifics of place: flora, fauna, geology, weather, and the folklore attached to all these things. It is shaped by the person I am, now, in this landscape and not another.

But what of those whose "home place" is a transient one, whether by preference or circumstance? Or those who are homeless, or exiled from home? Or the many of us who are immigrants, transplanted from distant countries and continents? What of those (the majority now) for whom home is an urban environment? Or those who have never found a place, outside of fiction and dreams, that feels like the place they truly belong? And how does this effect the creation of fantasy and mythic art, when myth itself is so often rooted in the land?

In his essay "The Dreaming of Place," storyteller and folklorist Hugh Lupton writes:

"The ground holds the memory of all that has happened to it. The landscapes we inhabit are rich in story. The lives of our ancestors have contributed to the shape and form of the land we know today -- whether we are treading the cracked cement of a deserted runaway, the boundary defined by a quickthorn hedge, the outline of a Roman road or the grassy hump of a Bronze Age tumulus. The creatures we share the landscape with have made their marks, too: their tracks, nesting places, slides and waterholes. And beyond the human and animal interactions are the huge, slow geological shapings that have given the land its form. Every bump, fold and crease, every hill and hollow is part of a narrative that is both human and prehuman. And as long as men and women have moved over the land these narratives have been spoken and sung.

"This sense of story being held immanent in landscape, is most clearly defined in the belief systems of the Aboriginal peoples of Australia. In Native Australian belief everything that is not 'here and now' is described as having gone 'into the dreaming.' The Aborigines believe that the tangled skein of remembered experience, history, legend and myth that constitutes the past -- that is invisible to the objective eye or the camera -- has not gone away. It is, rather, implicit in the place where it happened, a potentiality. It is a living memory that is held between a place and its people. It is always waiting to be woken by a voice.

"I remember the Irish storyteller Eamon Kelly once telling me that in the parish of County Clare where he grew up, every field had a name, and every field name was associated with a story. To walk from one end of the parish to the other was to walk through a landscape of story. It occurred to me that the same was probably once true for any parish in Britain.

"What does it mean for a culture to have lost touch with its dreaming? What can we do about it?

"It seems to me that as writers, artists, environmentalists, parents, teachers and talkers, one of our practices should be to enter the Dreaming, that invisible, parallel world, and salvage our local stories. We need to re-charge the landscape with its forgotten narratives. Only then will it regain the sacred status it once possessed. This might involve research into local history, conversations with elders in the community, exploration of regional folktales, ballads and myths...

"And then an intuitive jump into Imagination."

I couldn't agree more.

Ecologists talk of "re-wilding" the land. I believe we must "re-story" the land as well...and who else better than the writers of fantasy, steeped as we are in mythic traditions, to weave new myths out of the old, creating the vital tales we need in complex, troubled times.

Words: The passages quoted above are from Of Landscape and Longing: Finding a Home at the Water's Edge by Carolyn Servid (Milkweed Editions, 2000), and "The Dreaming of Place" by Hugh Lupton (EarthLines magazine, Issue 2, August 2012). The poem in the picture captions is an extract from Elegies by Muriel Rukeyser (New Directions, 1949). All rights reserved by the authors or their estates. Related posts: Kith & Kin, The Center Called Love, On Loss & Transfiguration, and The Tales We Tell.

Pictures: Tilly and her friend, Old Oak, who she visits almost every day. The two drawings are by Scottish book artist Eleanor Vere Boyle (1825-1916).

September 22, 2020

We are made for this

Last month we discussed the divide between science and art, and the particular pleasure of literary works inhabiting the edgelands between them -- such as nature writing, certain kinds of poetry, and fantasy fiction well-rooted in the magic of the natural world. (You can read that discussion running across three posts beginning here.)

Scott Russell Sanders is another writer, like Eva Saulitis and Alison Deming, who is equally at ease on both sides of the border. He came to his love of science after a church-and-bible childhood in rural Ohio, and both of these things have shaped his mind and his art. No longer Christian, he still finds value in the moral core of his religious upbringing, and plenty of scope for wonder and awe in the workings of the world around him.

In his fine new collection The Way of the Imagination, Sanders writes:

"The study of science fosters a greatly expanded sense of kinship, one that stretches from the dirt under our feet to distant galaxies. Exploding supernovas produced the calcium in our bones and the iron in our blood, along with all the elements heavier than helium that make up our bodies, our built environment, and our rocky, watery globe. We are kin not merely to a tribe or nation, not merely to humankind, but through our genes and evolutionary history we are linked to all life on Earth, plants and fungi as well as animals. We are made for this planet, creatures among creatures....

"What humans have learned about our world and ourselves is no doubt dwarfed by what we don't yet know, and may never know. Still, it's amazing that a short-lived creature on a dust-mote planet, circling an ordinary star near the edge of one among billions of galaxies, has managed to decipher so much about the workings of the universe. And the more we decipher, the more we realize that everything is connected to everything else, near and distant, living and nonliving, as mystics have long testified. The connectedness, this grand communion, is what I have come to think of as soul -- not my soul, as if I were a being apart, but the soul of Being itself, the whole of things.

"I have abandoned the religious creed in which I first encountered words like soul, sacred, holy, reverence, divinity, and awe, but I refuse to abandon the words themselves. For they point to what is of ultimate value, what claims our deepest respect. As a writer, I wish to say that nature is sacred, deserving of reverence for its creativity, antiquity, majesty, and power. I wish to say that Earth is holy, precious, surpassingly beautiful and bountiful, deserving of our utmost care. Although our survival is at stake, an appeal to fear won't inspire such care, because fear is exhausting and selfish. Although we need wise environmental policies, laws alone will not elicit such care, nor will a sense of duty, shame, or guilt. Only love will. Only love will move us to act wisely and caringly, year upon year, our whole lives long."

Any new book from Sanders is a cause for celebration, but The Way of the Imagination is especially wise (in its quiet, gentle way), and especially timely. I recommend it highly.

Words: The passage above is quoted from "A the Gates of Deep Darkness" by Scott Russell Sanders, published in The Way of the Imagination (Counterpoint, 2020). The poem in the picture captions is from Tin House (Winter, 2018). All rights reserved by the authors. Pictures: Down by the River Teign, early autumn.

September 21, 2020

Tunes for a Monday Morning

The Devon hedgerows are thick with blackberries and the orchards hang heavy with their fruits, so here are songs of farmers and plough boys, the harvest time, and the land's abundance....

Above: "Harvest Song" performed by Devon folk musician Jim Causley. It's from his early album Fruits of the Earth (2005).

Below: "Reaphook and Sickle" performed by Waterson-Carthy (Norma Waterson, Martin Carthy, Eliza Carthy, and Tim van Eyken), from their album Holy Heathens and the Old Green Man (2006)

Above: "Hey John Barleycorn" performed by Jack Rutter, a folk musician from West Yorkshire. This song isn't the better-known Barleycorn ballad popularised by Robert Burns but a broadside ballad from the 17th century, extolling the virtues of a plant will soon be made into ale and beer. The song appeared on Rutter's album Hills (2017).

Below: "The Farmer's Toast" performed by folk musician Kate Rusby, from South Yorkshire. The song appeared on her recent album Philosophers, Poets & Kings (2019).

Above: "The Barley and the Rye" performed by Bill Jones, a folk musician from Sunderland in the north of England. The song appeared on her early album Panchpuran (2001).

Below: "Ploughboy Lads" performed by Scottish musician Alasdair Roberts (of The Furrow Collective). The song appeared on his early solo album The Crook of My Arm (2001).

Above: Ralph McTell's "The Hiring Fair," performed by the long running folk-rock band Fairport Convention. This version of the song appeared on Fairport's album In Real Time (1987).

Below: "Lovely Molly," performed by London-based folk singer and song collector Sam Lee, with London's Roundhouse Choir, at the BBBC Radio 2 Folk Awards, 2016. The song appeared on his album The Fade in Time (2015). For more of his music, go here and here.

And one more....

Below: "Soil & Soul," a new song by the English vocal harmony trio Lady Maisery (Hannah James, Hazel Askew, and Rowan Rheingans). It appears on their album Live (2020).

September 14, 2020

Coming up this week...

Here's one last reminder that Ellen Kushner is giving a talk (on fantasy lit and her own creative practice) to mark the opening of the new Centre for Fantasy & the Fantastic at the University of Glasgow. It's online, it's free, and it's going to be fab, so if you're a fantasy reader (or fantasy-curious), please don't miss it.

There will also be information about the Centre (what it is and who it's for). And a panel discussion on the future of fantasy with two brilliant scholars of the field: Rob Maslen and Brian Attebery....and, umm, me.

There will also be information about the Centre (what it is and who it's for). And a panel discussion on the future of fantasy with two brilliant scholars of the field: Rob Maslen and Brian Attebery....and, umm, me.

The Zoom webinar tickets have sold out -- but don't worry, you can also view the whole event live on YouTube, and you don't need a ticket for that. Just follow this link on Wed. night (from 6 pm onward) to The Centre for Fantasy YouTube Channel. For more info, see my previous post about this event.

I'm sorry to say that Howard and I are down with post-viral syptoms, yet again, from the nasty bug he caught in Spain in February -- which might have been Covid-19, or something else similarly persistent; the antibody tests were inconclusive. I am saving my strength for the Fantasy Centre launch -- which means there will be no new Myth & Moor posts until the launch has passed and I'm back on my feet. I pray that won't be long, and thank you all for your kindness and patience.

Perhaps I'll see some of you at the launch on Wednesday night...?

Images above: A photograph of Ellen with Tilly by the Fairy Spring here in Chagford, during one of her many visits. A drawing by British book artist Helen Stratton (1867-1961). "Bedtime Story," a gorgeous painting by American artist Jeanie Tomanek. You can see more of her work here.

September 11, 2020

Wild stories

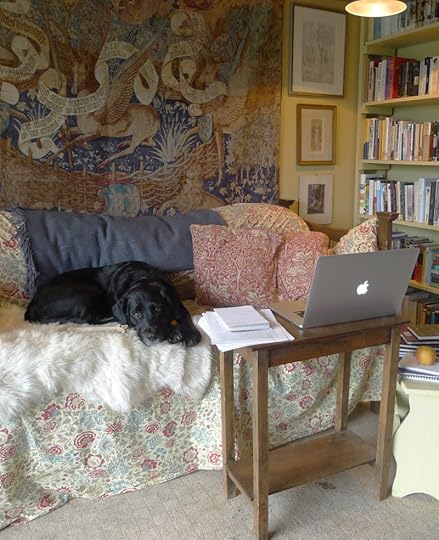

While the world of human affairs goes on its noisy, alarming way, I return again and again to the woods and hills behind my studio. To moss. To mud. To the mulch of leaves on the forest floor. To the strength of granite and the swift ways of water. To the hawthorn berries brightening the hedgerows, and blackberries ripening among the thorns. To acorns and apples dropping from the trees as the seasons turn.

I keep leaving my desk, Tilly close at my heels, crossing from the imaginary landscapes of writing or reading to a world I can touch, and smell, and taste: to the old stone wall at the edge of the treeline, and pathways trodden through bracken by ponies and sheep. To the riverside, the commons, the crossroads. To the chilly mornings and the night-times drawing in. To discomfort. To loss. To pain. To joy. To acceptance. To the things that are real.

I keep leaving my desk, Tilly close at my heels, crossing from the imaginary landscapes of writing or reading to a world I can touch, and smell, and taste: to the old stone wall at the edge of the treeline, and pathways trodden through bracken by ponies and sheep. To the riverside, the commons, the crossroads. To the chilly mornings and the night-times drawing in. To discomfort. To loss. To pain. To joy. To acceptance. To the things that are real.

An occupational hazard for the solitary writer is to live in the realm of the mind alone (or the shadowlands of the Internet), and not in the body, the senses, the wild rhythms of the local groundscape we each inhabit, whether rural or urban. For many of us in the fantasy field, the wild world is the very place that we seek to conjure and enter through stories and paintings -- and so we must not neglect our relationship with the elemental wild around us. In our kind of work, "magic" is not a metaphor for gaining power, control, or authority, but for our numinous connection with natural world, and our nonhuman neighhbors. It is wild work. It is soul work. And we need wild stories right now, more than ever.

"I have a sense," writes Kate Bernheimer (author & editor of The Fairy Tale Review) "that a proliferation of magical stories, especially fairy tales, is correlated to a growing human awareness of separation from the wild and natural world. In fairy tales, the human and animal worlds are equal and mutually dependent. The violence, suffering, and beauty are shared. Those drawn to fairy tales, perhaps, wish for a world that 'might live forever.' My work as a preservationist of fairy tales is entwined with all kinds of extinction."

"Writing," says Sylvia Linsteadt, "is my way into the heart of the world -- its wildness, its strange magic, its beauty, its terrors, its sadness, its joy. Metaphor (a favorite of mine) is an act of shape-shifting, of remembering that each thing is hitched to the next in the great cyclical transformation of energy, from sun to seed to doe to cougar and back to worm; the line between ourselves and the wild world is thin indeed. Writing (thick with metaphor) is the means through which I can praise the wild mystery of this world, and also explore its unseen realms -- the realms inside the hearts of bears and granite stones and buckeye trees; the lands just the other side of the moon and the fog, the lives of men and women long ago or just around the corner. If I were buckeye tree, then writing would be the buckeyes that fruit at the ends of my limbs come late August. In other words, writing is the thing made in me from all the waters and winds and soils and stories that come through my five senses (or six), and it feels very inevitable, like the buckeyes at the end of summer.

"Also, I have always been an avid reader," Sylvia continues; "especially as a child I devoured books that told of magical worlds and lands, lady-knights and healers, the everyday peasant life of Old Europe (especially Scotland & Ireland), talking animals, caravans of camel nomads, druids, long adventures on horseback. Such books literally shaped and changed my life. They informed the way I see the world today -- as a place much more mysterious and full of wild magics than we tend to believe, where everything is alive and everything speaks. So I write because writing is even better than reading in the sense that you really get to go to those places in your imagination, and give them to other people. The stories we tell ourselves and each other form the world in which we live."

Our task, as David Abram sees is, "is that of taking up the written word, with all its potency, and patiently, carefully, writing language back into the land. Our craft is that of releasing the budded, earthly intelligence of our words, freeing them to respond to the speech of things themselves -- the the green uttering-forth of leaves from the spring branches. It is the practice of spinning stories that have a rhythm and lilt of the local soundscape, tales for the tongue, tales that want to be told, again and again, sliding off the digital screen and slipping off the lettered page to inhabit the coastal forests, those desert canyons, those whispering grasslands and valley and swamps."

"Storytellers ought not to be too tame," Ben Okri agrees. "They ought to be wild creatures who function adequately in society. They are best in disguise. If they lose all their wildness, they cannot give us the truest joys."

Jay Griffiths adds: "What is wild cannot be bought or sold, borrowed or copied. It is. Unmistakeable, unforgettable, unshamable, elemental as earth and ice, water, fire and air, a quitessence, pure spirit, resolving into no contituents. Don't waste your wildness: it is precious and necessary."

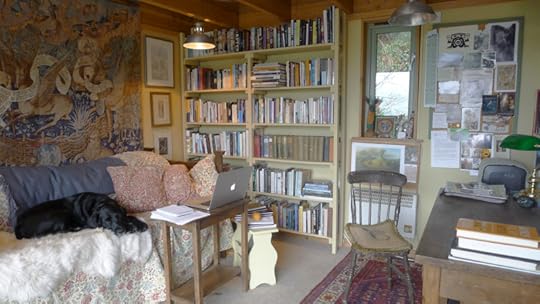

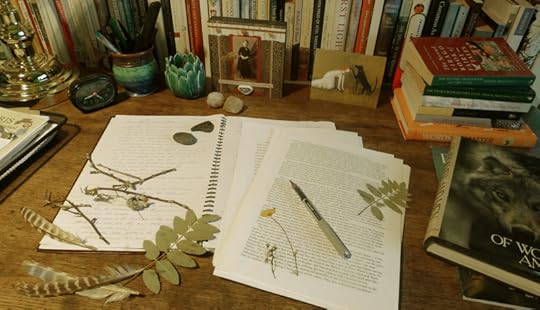

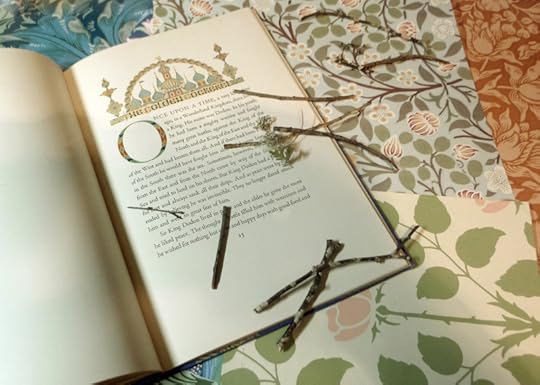

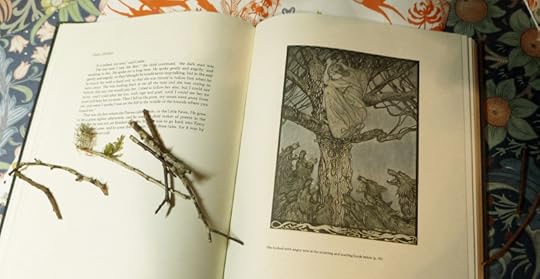

Words: The passage by Sylvia Linsteadt is from an interview by Asia Sular (Woolgathering & Wildcrafting, Sept. 2014), which I recommend reading in full. Kate Bernheimer's quote is from the Introduction to her anthology My Mother She Killed Me, My Father He Ate Me: Forty New Fairy Tales (Penguin, 2010); Ben Okri's quote is from his essay collection A Way of Being Free (W&N, 1997); Jay Griffith's quote is from Wild: An Elemental Journey (Penguin, 2007). All three books are recommded. All rights reserved by the authors. Pictures: My quiet hillside studio on a rainy day -- with the hound, works-in-progress, old fairy tale books, and bits of the wild slipping in from the woods.

September 10, 2020

Dipping from the Cauldron of Story

From "High Fantasy and Heroic Romance" by Lloyd Alexander:

"While its full meaning remains tantalizingly unknown, we can trace mythology's historical growth into an art form: through epic poetry, the chansons de geste, the Icelandic sagas, the medi��eval romances and works of prose in the Romance languages. Its family tree includes Beowulf, the Eddas, The Song of Roland, Amad��s de Gaule, the Perceval of Chretien de Troyes, and The Faerie Queene. In modern literature, one form that draws most directly from the fountainhead of mythology, and does it consciously and deliberately, is the heroic romance, which is a form of high fantasy. The world of heroic romance is, as Professor Northrop Frye defines the whole world of literature in The Educated Imagination, 'the world of heroes and gods and titans..., a world of powers and passions and moments of ecstasy far greater than anything we meet outside the imagination.'

"If anyone can be credited with inventing the heroic romance as we know it today -- that is, in the form of a novel using epic, saga, and chanson de geste as some of its raw materials -- it must be William Morris, in such books as The Wood Beyond the World and The Water of the Wondrous Isles. Certainly Morris showed the tremendous strength and potential of the heroic romance as an artistic vehicle, which was later to be used by Lord Dunsany, Eric Eddison, James Branch Cabell; by C. S. Lewis and T. H. White. Of course, heroic romance is the basis of the superb achievements of J. R.R. Tolkien.

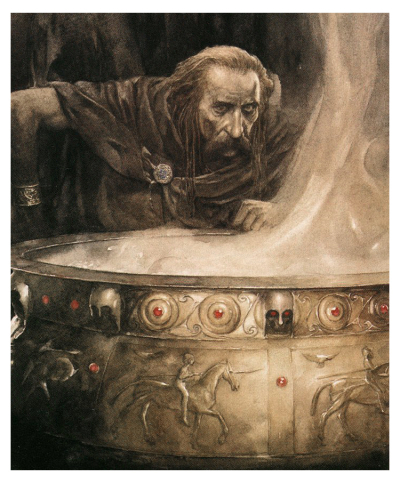

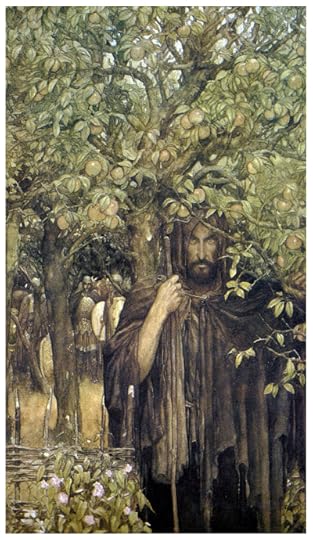

"Writers of heroic romance, who work directly in the tradition and within the conventions of an earlier body of literature and legend, draw from a common source: the 'Pot of Soup,' as Tol��kien calls it, the 'Cauldron of Story,' which has been simmering away since time immemorial. The pot holds a rich and fascinating kind of mythological minestrone. Almost everything has gone into it, and almost any�� thing is likely to come out of it: morsels of real history -- spiced�� and spliced -- with imaginary history, fact and fancy, daydreams and nightmares. It is as inexhaustible as those legendary vessels that could never be emptied.

"Among the most nourishing bits and pieces we can scoop out of the pot are whole assortments of characters, events, and situa��tions that occur again and again in one form or another through�� out much of the world's mythology: heroes and villains, fairy godmothers and wicked stepmothers, princesses and pig-keepers, prisoners and rescuers; ordeals and temptations, the quest for the magical object, the set of tasks to be accomplished. And a whole arsenal of cognominal swords, enchanted weapons; a wardrobe of cloaks of invisibility, seven-league boots; a whole zoo of dragons, helpful animals, birds, and fish.

"Among the most nourishing bits and pieces we can scoop out of the pot are whole assortments of characters, events, and situa��tions that occur again and again in one form or another through�� out much of the world's mythology: heroes and villains, fairy godmothers and wicked stepmothers, princesses and pig-keepers, prisoners and rescuers; ordeals and temptations, the quest for the magical object, the set of tasks to be accomplished. And a whole arsenal of cognominal swords, enchanted weapons; a wardrobe of cloaks of invisibility, seven-league boots; a whole zoo of dragons, helpful animals, birds, and fish.

"But -- in accordance with one of fantasy's own conventions -- nothing is given for nothing. Although we are free and welcome to ladle up whatever suits our taste, and fill ourselves with any mixture we please, nevertheless, we have to digest it, assimilate it as thoroughly as we assimilate the objective experiences of real life. As conscious artists, we have to process it on the most per��sonal levels; let it work on our personalities and, above all, let our personalities work on it. Otherwise we have what the com��puter people delicately call GIGO: garbage in, garbage out. Because these conventional characters -- these personae of myth and fairy tale, though gorgeously costumed and capari��soned -- are faceless, the writer must fill in their expressions. Colorful figures in a pantomime, the writer must give them a voice.

"Since I have been talking about the 'Cauldron of Story,' I am now reminded of the Crochan, the Black Cauldron that figured in one of the books of Prydain. Now, cauldrons of one sort or another are common household appliances in the realm of fan��tasy. Sometimes they appear, very practically, as inexhaustible sources of food, or, on a more symbolic level, as a lifegiving source or as a means of regeneration. Some cauldrons bestow wisdom on the one who tastes their brew. In Celtic mythology, there is a cauldron of poetic knowledge guarded by nine maidens, counterparts of the nine Greek muses.

"There is also a cauldron to bring slain warriors back to life. The scholarly interpretation -- the mythographic meaning -- is a fascinating one that links together all the other meanings. Im��mersion in the cauldron represented initiation into certain re��ligious mysteries involving death and rebirth. The initiates, being figuratively -- and perhaps literally -- steeped in the cult mys��teries, emerged reborn as adepts. In legend, those who came out of the cauldron had gained new life but had lost the power of speech. Scholars interpret this loss of speech as representing an oath of secrecy.

"One branch of The Mabinogion, the basic collection of Welsh mythology, and one of my own prime research sources, tells of such a caul

dron of regeneration, and how it ended up in the hands of the Irish. And, in the tale of Branwen, the Welsh princess rescued from the Irish by King Bran, a great number of slain Irish warriors came back to life. Naturally, this cauldron posed an uncomfortable problem for the Welshmen, who were constantly finding themselves outnumbered; until one of the Welsh soldiers sacrificed his life by leaping into the cauldron and shattering it. This incident gave me the external shape of the climax of The Black Cauldron. Though changed and manipulated con��siderably, the nub of the story is located in the myth ���- except for one detail of characterization: the essential internal nature of the cauldron, its inner meaning and significance beyond its being an unbeatable item of weaponry.

"And so I tried to develop my own conception of the cauldron. Despite its regenerative powers, it seemed to me more sinister than otherwise. The muteness of the warriors created the horror I associated with the cauldron. Somehow, I felt that these voice��less men, already slain, revived only to fight again, deprived even of the oblivion of the grave, were less beneficiaries than victims. As the idea grew, I began to sense the cauldron as a kind of ultimately evil device. My 'Cauldron-Born,' then, were not only mute but enslaved to another's will. If they had lost their power of speech, they had also lost their memory of themselves as living beings -- without recollection of joy or sorrow, tears or laughter. They had, in effect, been deprived of their humanity: a fate, in my opinion, considerably worse than death. The risk of dehumanization ��� of individuals being manipulated as objects in�� stead of being valued as living people -- is, unfortunately, not confined to the realm of fantasy.

"Another example of the same kind of creative invention on the part of a writer has to do with the birth of a character; and in this case a most difficult delivery. Writing The Book of Three, the first of the Prydain chronicles, I was groping my way through the early chapters with that queasy sensation of desper��ate insecurity that comes when you do not know what is going to happen next. I knew vaguely what should happen, but I could not figure out how to get at it. The story, at this point, needed another character: Whether friend or foe, minor or major, comic or sinister, I could not decide. I only knew that I needed him, and he refused to appear.

"The work came to a screaming halt: the screams being those of the author. Day after day, for better than a week, I stumbled into my work room and sat there, feeling my brain turn to con��crete. I had been reading a very curious book, an eighteenth-cen��tury account of the various characters in Celtic mythology. One of them stuck in my mind -- a one-line description of a creature half-human, half-animal. The account was interesting, but it was not doing much to solve my problem. I was convinced, by now, that I had suffered severe brain damage; that I would never write again; the mortgage would be foreclosed; my wife carried off to the Drexel Hill poor-farm; and I -- quivering and gibbering, moaning and groaning -- I did not even dare to imagine what would become of me. The would-be author of a hero-tale had begun to show his innate cowardice, and I was feeling tremendously sorry for myself.

"The work came to a screaming halt: the screams being those of the author. Day after day, for better than a week, I stumbled into my work room and sat there, feeling my brain turn to con��crete. I had been reading a very curious book, an eighteenth-cen��tury account of the various characters in Celtic mythology. One of them stuck in my mind -- a one-line description of a creature half-human, half-animal. The account was interesting, but it was not doing much to solve my problem. I was convinced, by now, that I had suffered severe brain damage; that I would never write again; the mortgage would be foreclosed; my wife carried off to the Drexel Hill poor-farm; and I -- quivering and gibbering, moaning and groaning -- I did not even dare to imagine what would become of me. The would-be author of a hero-tale had begun to show his innate cowardice, and I was feeling tremendously sorry for myself.

"At four o'clock one morning, I had gone to my work room for what had become a routine session of sniveling and hand-wring��ing. I had decided, one way or another, to use this hint of a half�� animal, half-human creature. The eighteenth-century text had given him a name -- Gurgi. It seemed to fit, but he still refused to enter the scene. I could see him, a little; but I could not hear him. If I could only make him talk, half the battle would be over. But he would not talk. And so I sat there, expecting to pass the morning as usual, crying and sighing. All of a sudden, for no apparent reason what�� ever, I heard a voice in the back of my mind, plaintive, whining, self-pitying. It said: 'Crunchings and munchings?' And there, right at that moment, there he was. Part of him, certainly, came from research. The rest of him -- I have a pretty good idea where it came from.

"My point, in these examples, is simply this: A writer of fan��tasy, like any writer, must find the essential content of his work within himself, in his own personality, in his own attitude and commitment to real life. Whatever form we work in -- fantasy or realism, books for children or for adults -- I believe that the fundamental creative process is the same. In his work, the author may be very heavily disguised, or altogether anonymous. I do not think he is ever totally absent.

"On the contrary, his presence is required; not as a stage man��ager who can be seen busily shifting the cardboard scenery, but as the primary source of tonality and viewpoint. Without this viewpoint, the work becomes more and more abstract, a play of the intellect that can move us only intellectually. It may be tech��nically brilliant, but it becomes sleight of hand instead of true magic. If art -- as Plato defined it -- is a dream for awakened minds, it should be, at the same time, a dream that quickens the heart.

"High fantasy indeed quickens the heart and reaches levels of emotion, areas of feeling that no other form touches in quite the same way. Some books we can enjoy, some we can admire, and some we can love. And among those books that we love as chil��dren, that we remember best as adults, fantasy is by no means least."

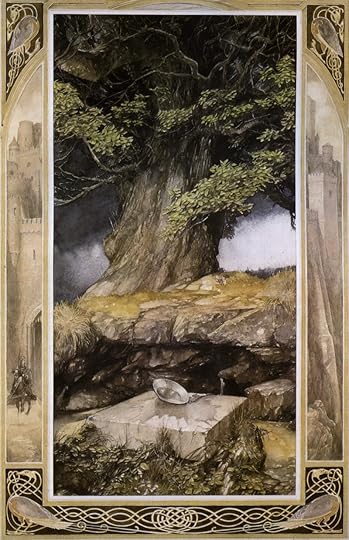

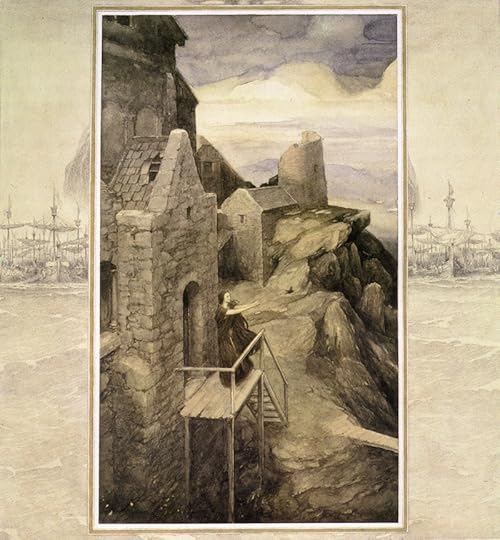

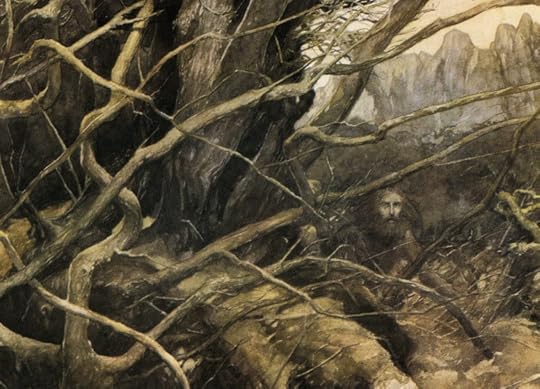

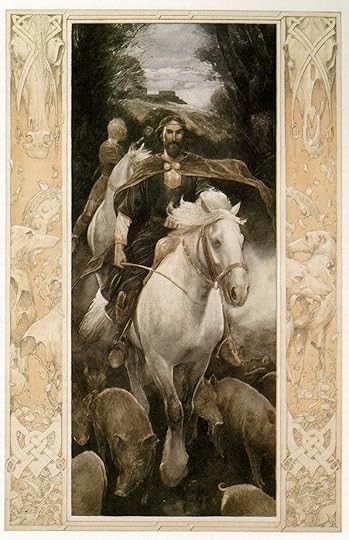

The art today is from The Mabinogion, magnificently illustrated by Alan Lee. The paintings first appeared in an edition published by Dragon's Dream in 1982 (translated by Gwyn Thomas and Thomas Jones, 1949), and can now be found in a volume published by HarperVoyager in 2000 (translated by Lady Charlotte Guest, 1838-1845). The Easton Press published a sumptuous limited edition (with the Guest translation) in 2015.

More of Alan's artwork, including other Mabinogion paintings, can be found in this post from last week.

The passage above is from "High Fantasy and Heroic Romance" by Lloyd Alexander (The Horn Books, Dec. 16, 1971). You can read the full essay here. All rights reserved by the author's estate. The paintings above first appeared in The Mabinogion, translated by Gwyn Jones & Thomas Jones, illustrated by Alan Lee (Dragon's Dream/JM Dent & Sons Ltd, 1982). All rights reserved by the artist.

September 9, 2020

Stepping into story

"Step across the boundary and the trespass of story will begin. The forest takes a deep breath and through its whispering leaves an incipient adventure unfurls. The quest. In the lull -- not the drowsy lull of a lullaby but the sotto voce of a woodland clearing, scented with story as it is with with wild garlic -- this is the moment of beginning, the pause on the threshold before the journey. So many tales begin here, hard by a great forest...."

"Humans are storytelling creatures. We need story, we need deep mythic happenings, as much as we need food and sun: to set us in our place in the family of things, in a world that lives and breathes and throws us wild tests, to show us the wildernesses and the lakes, the transforming swans, of our own minds. These minds of ours, after all, are themselves wild, shaped directly by our long legacy as hunters, as readers of wind, fir-tip, animal trail, paw-mark in mud. We are made for narrative, because narrative is what once led us to food, be it elk, salmonberry or hare; to that sacred communion of one body being eaten by another, literally transformed, and afterward sung to."

"When we are at ease in our animal flesh, we will sometimes feel we are being listened to, or sensed, by the earthly surroundings. And so we take deeper care with our speaking, mindful that our sounds may carry more than a merely human meaning and resonance. This care -- this full-bodied alertness -- is the ancient, ancestral source of all word magic. It is the practice of attention to the uncanny power that lives in our spoken phrases to touch and sometimes transform the tenor of the world's unfolding."

"The earliest storytellers were magi, seers, bards, griots, shamans. They were, it would seem, as old as time, and as terrifying to gaze upon as the mysteries with which they wrestled. They wrestled with mysteries and transformed them into myths which coded the world and helped the community to live through one more darkness, with eyes wide open and hearts set alight."

- Ben Okri

"For adults, the world of fantasy books returns to us the great words of power which, in order to be tamed, we have excised from our adult vocabularies. These words are the pornography of innocence, words which adults no longer use with other adults, and so we laugh at them and consign them to the nursery, fear masking as cynicism. These are the words that were forged in the earth, air, fire, and water of human existence, and the words are: Love. Hate. Good. Evil. Courage. Honor. Truth."

"Current cant equates fantasy with escapism, and current fashion would have it that fantasy is both easy to read and to write. It isn't. When it is done honestly, by a skillful writer, fantasy takes us far enough beyond our daily perceptions to open us to the essential realities beneath it."

"Someone needs to tell those tales. When the battles are fought and won and lost, when the pirates find their treasures and the dragons eat their foes for breakfast with a nice cup of Lapsang souchong, someone needs to tell their bits of overlapping narrative. There's magic in that. It's in the listener, and for each and every ear it will be different, and it will affect them in ways they can never predict. From the mundane to the profound. You may tell a tale that takes up residence in someone's soul, becomes their blood and self and purpose. That tale will move them and drive them and who knows what they might do because of it, because of your words."

"To me, fantasy has the emotional strength of a dream, it works directly on our nerve endings, whatever age we happen to be, touching heights and depths not always accessible through realism. In fantasy, my concern is how we learn to be real human beings. It's a continuing process."

The imagery today is by Alexandra Dvornikova, a contemporary folk artist and illustrator from Saint Petersburg, Russia. She studied print-making, graphics, and art therapy at Saint Petersburg Stieglitz State Academy of Art and Design, and now creates books, cards and prints, fabric designs, animations, and more. She finds inspiration in the Russian fairy tales she heard as a child, as well as masks, music, ritual, nature and ecology, the folklore of animals, mosses and mushrooms, venomous plants, and lonely cabins deep in the woods. To see more of her art, please visit Dvornikova's website and Instagram page.

All rights to the art and text above reserved by the artist and the authors, or their estates. Painting titles can be found in the picture captions. (Run your cursor over the images to see them.)

September 8, 2020

Oak and stone

"How it is that animals understand things I do not know, but it is certain that they do understand. Perhaps there is a language which is not made of words and everything in the world understands it. Perhaps there is a soul hidden in everything and it can always speak, without even making a sound, to another soul."

- Frances Hodgson Burnett (A Little Princess)

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 710 followers