Terri Windling's Blog, page 26

October 5, 2020

Music and update

I  'm out of the studio today, down with symptoms again from mystery (Covid?) virus that Howard and I contracted early in the spring. These virus relapses have been getting shorter, at least, so I hope to be back in a day or two. (Touch wood.)

'm out of the studio today, down with symptoms again from mystery (Covid?) virus that Howard and I contracted early in the spring. These virus relapses have been getting shorter, at least, so I hope to be back in a day or two. (Touch wood.)

In the meantime, here's a wee bit of Monday Music: the latest video from Irish filmmaker Myles O'Reilly, whose work I love. He says:

"I managed to escape the pale to visit the extraordinary medieval town of Clonmel for this next musical yarn, and a yarn it truly is. There I met with the legend John Spillane and a very humble and inspiring puppeteer by the name of Des Dillon. The beautiful characters which Des brings to life in this video are just the right amount of joy to serve as an affective antidote to all the noise out there."

Visit O'Reilly's website to see more of Irish music films, and his Patreon page to support this work.

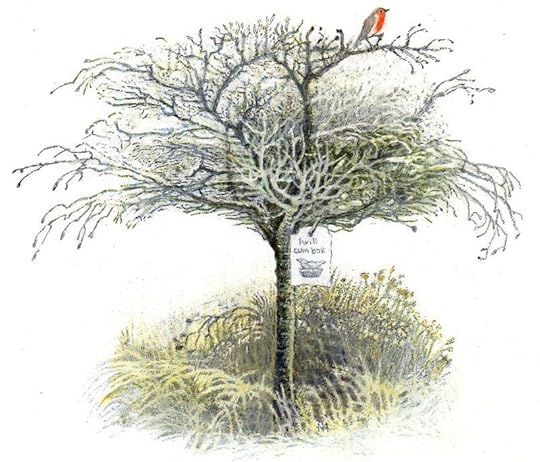

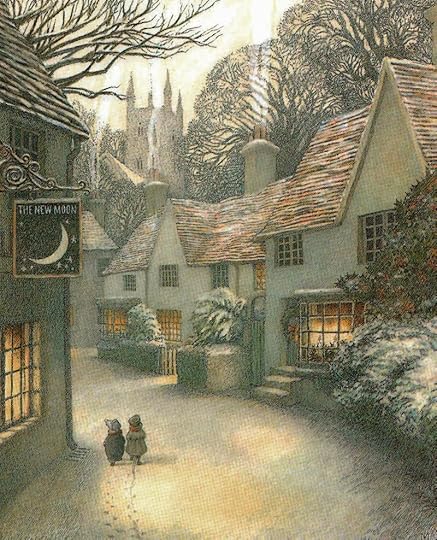

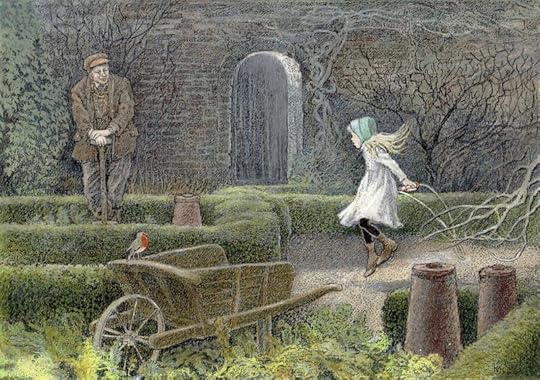

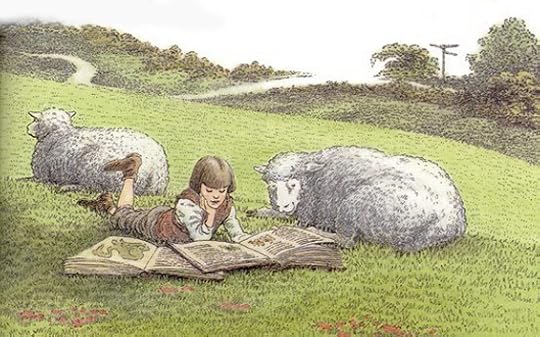

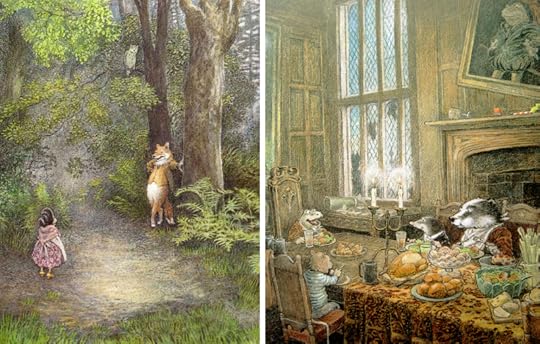

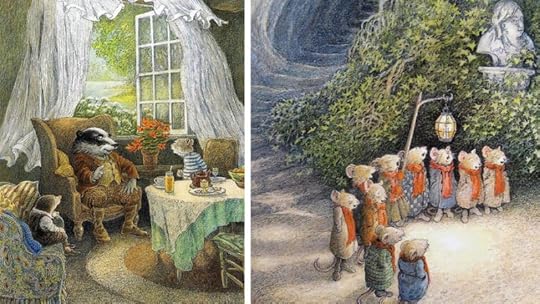

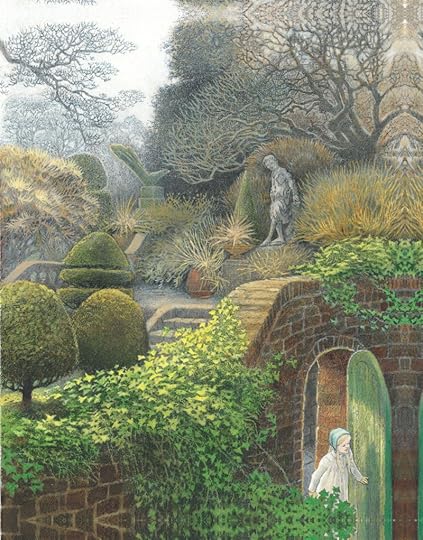

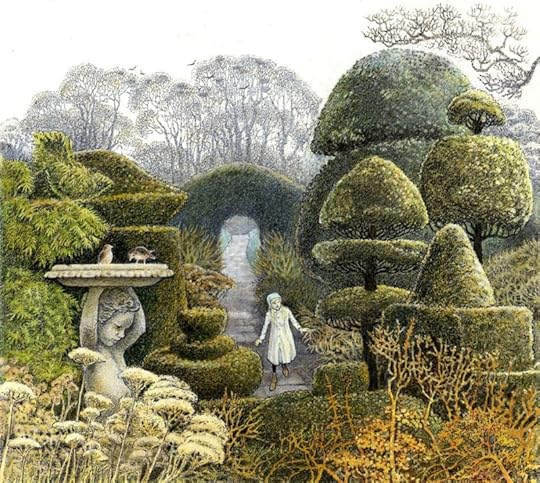

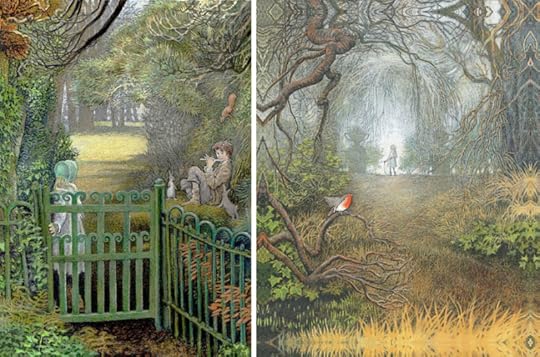

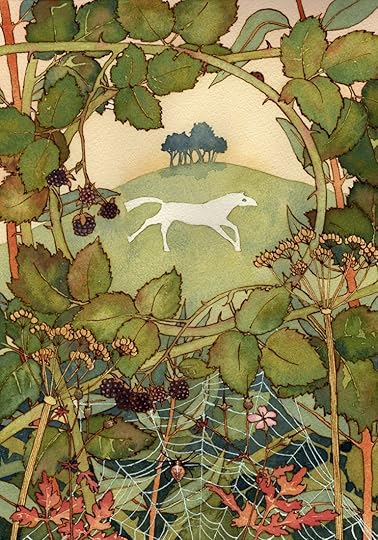

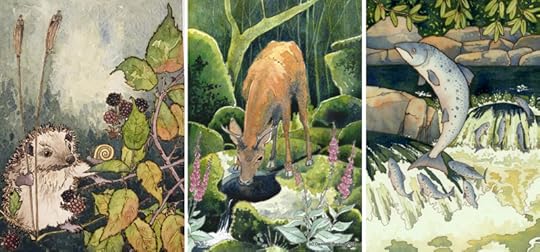

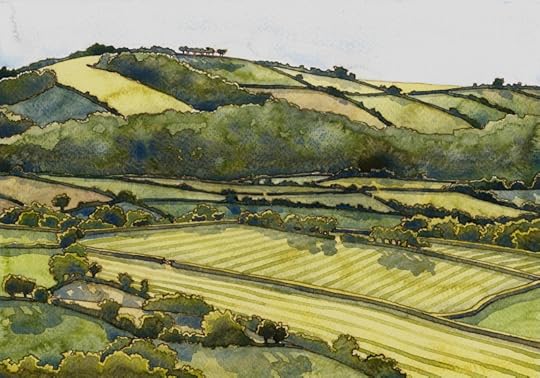

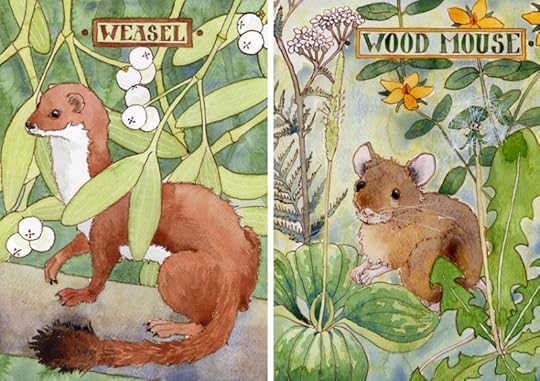

The illustrations above art by Inga Moore. All rights to the film and art in this post reserved by the filmmaker and artist.

October 3, 2020

On loss and transfiguration

The classic makers of children's literature, writes Alison Lurie,

"are not usually men and women who had consistently happy childhoods -- or even consistently unhappy ones. Rather they are those whose early happiness ended suddenly and often disastrously. Characteristically, they lost one or both parents early. They were abruptly shunted from one home to another, like Louisa May Alcott, Kenneth Grahame, and Mark Twain -- or even, like Frances Hodgson Burnett, E. Nesbit, and J.R.R. Tolkien, from one country to another. L. Frank Baum and Lewis Carroll were sent away to harsh and bullying schools; Rudyard Kipling was taken from India to England by his affectionate but ill-advised parents and left in the care of stupid and brutal strangers. Cheated of their full share of childhood, these men and women later re-created, and transfigured, their lost worlds. "

J.M Barrie falls into this catagory, the happiness of his early childhood vanishing into darkness and gloom when an elder brother, the family favorite, died in a skating accident, after which Barrie's mother retreated permanently to her bed. C.S. Lewis was ten when he lost his mother to cancer (and just four when his beloved dog, Jacksie, was killed by a car -- a loss that so effected him that he insisted upon being called Jack for the rest of his life). George MacDonald lost his mother to tuberculosis at the age of eight. Enid Blyton's happy childhood in Kent ended  abruptly when her beloved father left the family for another woman, leaving Enid behind with a mother who disapproved of her interest in nature, literature, and art.

abruptly when her beloved father left the family for another woman, leaving Enid behind with a mother who disapproved of her interest in nature, literature, and art.

The sudden loss of a happier childhood world doesn't turn everyone into a children's book writer, of course, but it's interesting to note how many fine writers' backgrounds are marked by such loss; and Lurie may be correct that the desire to re-create the lost world lies at the heart of a particular form of creative inspiration. Or perhaps I'm just struck by Lurie's idea because it maps onto my own childhood, which was, from a child's point of view, safe and stable for the first six years when I lived in my grandmother's household (with my teenage mother and her sisters), and then plunged into darkness upon my mother's marriage to a brutal man, a stranger to me until the day of the wedding. Loss of home at a tender age can indeed send an unhappy child inward, seeking lands in imagination uncorrupted by the treacherous adult world.

Last week, we talked about concepts of home, place, connection to the landscape, and the way these things impact creative work. Today I'd like to come at the subject from a slightly different direction, with the idea that loss of home can be as powerful a creative spur as the finding of the heart's home, or the love of a long-established one.

Loss can come about in so many different ways, and needn't be dramatic to cause lasting trauma. I'm thinking, for example, of a loss all too common today in our over-populated world: the loss of treasured childhood landscapes to the unchecked sprawl of cities and suburbs, of beloved old houses and places we can never return to, buried under shopping malls and parking lots.

In her essay collection Language and Longing, Carolyn Servid writes poignantly of her husband's childhood in an isolated valley in the mountains of Colorado. Lightly populated by old ranching families, artists, and hermits, the valley was a sanctuary for humans and animals alike...until the development of the nearby town of Aspen into a ski resort and playground for the wealthy began to raise property prices on Aspen's periphery. When the dirt road into the valley was paved, change was not long behind: land speculation, housing developments, a golf course. The valley as generations had known and loved it was gone. Servid writes:

"[My husband] had witnessed this gradual transformation during summers home from college. He witnessed more changes every time he visited after marriage and various jobs took him out of the valley. He chronicled those changes to me before he ever drove me up the Crystal River Road to the Redstone house. The landscape stunned me the first time I saw it, and I watched it bring a deep smile of recognition to Dorik's eyes, but I knew his memories were of a wholeness that was no longer there. I realized he held a kind of perspective and knowledge that has been lost over and over again in the settlement of the continent, over and over again in the civilization of the world."

A little later, he learns that a neighbor's ranch has been sold off to a developer:

"I watched his face tighten, and knew that a deepening ache was filling him. Places and people he loved were both caught in the wake of rampant development that grew like a cancer. The impact was like a diagnosis of the disease itself, as though one of the most fundamental aspects of his life was being eaten away. I wondered then about the grief that comes to us when we lose the places we love. This grief doesn't have much standing among the range of emotions that our society values. We have yet to fully acknowledge and accept just how much our hearts are entwined with the places that shape us, tolerate us, hold us, provide for us. We have yet to openly testify and accede to the necessity of such places and love of them in our daily lives. We have yet to fully understand that our links as people living together in communties will never be more than transient and vulnerable without rootedness in the place itself."

Just as Servid wonders "about the grief that comes to us when we lose the places we love," I wonder about the ways such a loss impacts us as writers and artists. Grief is a powerful thing, and especially so when it rumbles away, unexpressed, in the depth of our souls, the quiet but constant base note of our lives. Grief for landscapes paved over, ways of life that are gone, for whole species that are rapidly vanishing around us. Grief can indeed be a spur to art, leading us to "re-create or transfigure" our cherished lost worlds, or it can do the reverse: deaden and silence and paralyze us.

Your thoughts?

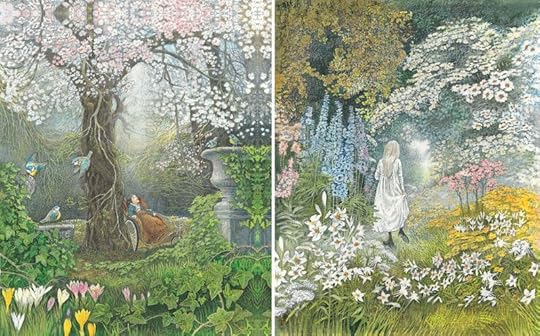

Like yesterday, the beautiful art in this post is by Inga Moore, who was born in Sussex, raised in Australia (from the age of eight), and returned to England when she reached adulthood. Joanna Carey, in her lovely portrait of the artist, writes:

"An imaginative, somewhat subversive child, she drew constantly, illustrating not just her own stories but also her schoolbooks, her homework, tests and exam papers. 'If you'd only stop all this silly drawing,' said the Latin teacher, 'you might one day amount to something.' She did stop -- 'for a long time' -- and is still resentful about that teacher's attitude. She regrets not going to art school, and endured 'one boring job after another' before eventually getting back to the drawing board. Supporting herself making maps for a groundwater company, she embarked on a series of landscapes and happily rediscovered her passion for drawing."

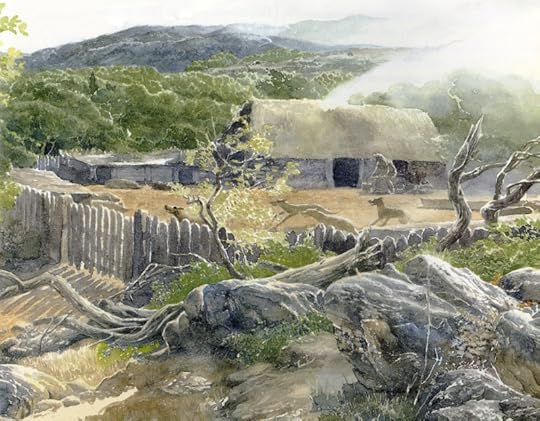

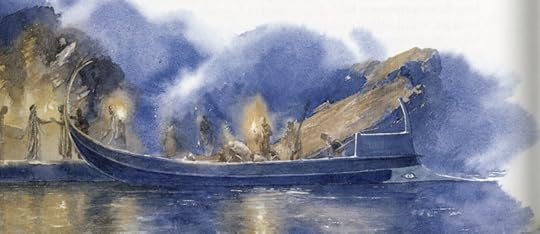

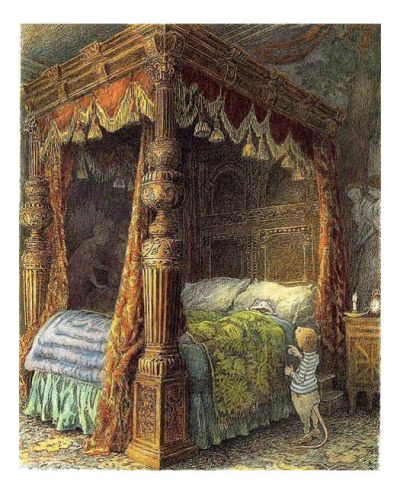

The pictures here are from Moore's editions of The Wind in the Willows, The Secret Garden, and The Reluctant Dragon, all highly recommended.

The passage by Alison Lurie is from Don't Tell the Grown-ups: Subversive Children's Literature (Little, Brown Publishers, 1990). The passage by Carolyn Servid is from Of Language and Longing: Finding a Home at the Water's Edge (Milkweed Editions, 2000). The quote by Joanna Carey is from "Inga Moore, illustrator of The Wind in the Willows" ( The Guardian, Feburary 6, 2010). All rights to the text and art above reserved by the authors and artist.

October 1, 2020

Stories with mischief in their blood

Storytelling is a subversive occupation, says Ben Okri:

"It is a double-headed axe. You think [the story] faces only one way, but it also faces you. You think it cuts only in one direction, but it also cuts you. You think it applies to others only, when it mainly applies to you. When you think it is harmless, that is when it springs its hidden truths, its uncomfortable truths, on you. It startles your complacency. And when you no longer listen, it lies silently in your brain, waiting.

"Stories are very personal things. They drift about quietly in your soul. They never shout their most dangerous warnings. They sometimes lend amplification to the promptings of conscience, but their effect is more pervasive. They infect your dreams. They infect your perceptions. They are always successful in their occupation of your spirit. And stories always have mischief in their blood. Stories, as can be seen from my choice of associate images, are living things; and their real life begins when they start to live in you. Then they never stop living, or growing, or mutating, or feeding the groundswell of imagination, sensibility, and character.

"Stories are subversive because they always come from the other side, and we can never inhabit all sides at once. If we are here, story speaks for there; and vice versa. Their democracy is frightening; their ultimate non-allegiance is sobering. They are the freest inventions of our deepest selves, and they always take wing and soar beyond the place where we can keep them fixed."

The most memorable stories reflect something of ourselves, Okri adds. We live our lives on this side of the mirror,

"but when joy touches us, and when bliss flashes inside us briefly, we have a stronger intuition. The best life, and the life we would really want to live, is on the other side of the mirror -- the side that faces out to the great light and which hints at an unexpected paradise. The greatest stories speak to us with our voice, but they speak to us from the other side."

Alison Lurie points out that the some of most subversive stories of all can be found in children's literature. So many of the classics, from Alice in Wonderland to The Hobbit,

"suggest that there are other views of human life besides those of the shopping mall and the corporation. They mock current assumptions and express the imaginative, unconventional, noncommercial view of the world in its simplest and purest form. They appeal to the imaginative, questioning, rebellious child within all of us, renew our instinctive energy, and act as a force for change. This is why such literature is worthy of our attention and will endure long after more conventional tales have been forgotten."

In Why You Should Read Children's Books Even Though You Are So Old and Wise, Katherine Rundell writes:

"A lot of children's fiction has a surprising politics to it. Despite all our tendencies in Britain towards order and discipline -- towards etiquette manuals and school uniforms that make the wearers look like tiny mayoral candidates -- our children's fiction is often slyly subversive.

"Mary Poppins, for instance, is a precursor to the hippy creed: anti-corporate, pro-play. Mr. Banks (the name is significant) sits at a large desk 'and made money. All day long he worked, cutting out pennies and shillings...And he brought them home with him in his little black bag.'

Edith Nesbit was a Marxist socialist who named her son Fabian after the Fabian Society; The Story of the Treasure Seekers contains jagged little ironical stabs against bankers, politicians, newspapers offering 'get rich quick' schemes and the intellectual pretensions of the middle class.

"And the same is true across much of the world; it was Ursula Le Guin, one of the greatest American children's writers, who said this: 'We live in capitalism. Its power seems inescapable -- but then, so did the divine right of kings. Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings. Resistance and change often begin in art. Very often in our art, the art of words.' Children's books in the house can be dangerous things in hiding, a sword concealed in an umbrella.

"Children's books are specifically written to be read by a section of society without political or economic power. People who have no money, no vote, no control over capital or labour or the institutions of state; who navigate the world in the knowledge of their vulnerability. And, by the same measure, by people who are not yet preoccupied by the obligations of labour, not yet skilled in forcing their own prejudices on to other people and chewing at their own hearts. And because at so many times in life, despite what we tell ourselves, adults are powerless too, we as adults must hasten to children's books to be reminded of what we have left to us, whenever we need to start out all over again."

But there is also danger in stories, cautions Scott Russell Sanders,

"as in any great force. If the tales that captivate us are silly or deceitful, like most of those offered by television or advertising, they waste our time and warp our desires. If they are cruel they make us callous. If they are false and bullying, instead of drawing us into a thoughtful community they may lure us into an unthinking herd or, worst of all, into a crowd screaming for blood -- in which case we need other, truer stories to renew our vision. So The Diary of Anne Frank and Primo Levi's Survival in Auschwitz are antidotes to Mein Kamp. So Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man and Toni Morrison's Beloved are antidotes to the paranoid yarns of the Ku Klux Klan. So the patient exchange of stories between people searching for common ground is an antidote to the hasty sloganeering and slandering of talk shows....

"We are creatures of instinct, but not solely of instinct. More than any other animal we must learn to behave. In this perennial effort, as Ursula Le Guin says, 'Story is our nearest and dearest way of understanding our lives and finding our way onward.' Skill is knowing how to do something; wisdom is knowing when and why to do it, or to refrain from doing it. While stories may display skill aplenty, in technique or character or plot, what the best of them offer is wisdom. They hold a living reservoir of human possibilities, telling us what has worked before, what has failed, where meaning and purpose and joy might be found. At the heart of many a tale is a test, a puzzle, a riddle, a problem to solve; and that, surely, is the condition of our lives, both in detail -- as we decide how to act in the present moment -- and in general, as we seek to understand what it all means.

"Like so many characters, we are lost in a dark wood, a labyrinth, a swamp, and we need a trail of stories to show us the way back to our true home."

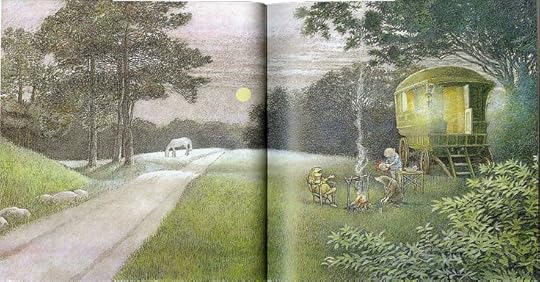

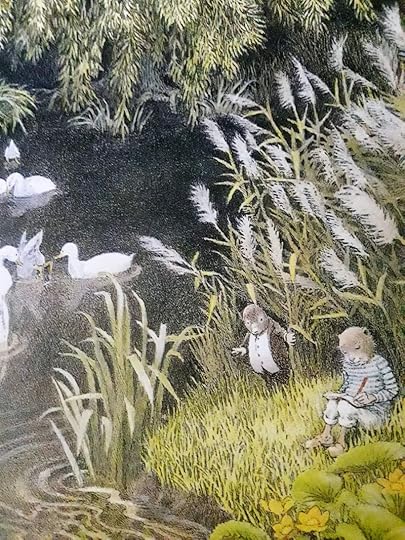

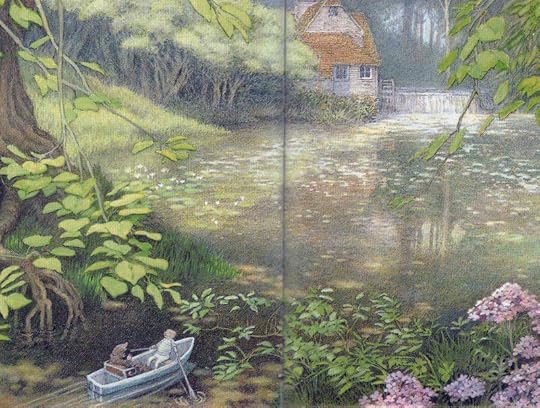

The lovely art today is by Inga Moore, who was born in Sussex, raised in Australia, and returned to England when she reached adulthood. She worked as an illustrator in London until the economic downturn caused her to lose her home there -- a fortunate loss, as it turns out. She relocated to the Gloucester countryside, discovered this rural corner of England to be her heart's home, and produced the remarkable illustrations for The Wind in the Willows and The Secret Garden for which she is now justly famed. You can learn more about the artist here.

Words: The passages quoted above are from A Way of Being Free: Essays by Ben Okri (Phoenix House, 1997); Don't Tell the Grown-ups: The Subversive Power of Children's Literature by Alison Lurie (Little Brown, 1990), Why You Should Read Children's Books Even Though You Are So Old and Wise by Katherine Rundell (Bloomsbury, 2019), and The Force of Spirit: Essays by Scott Russel (Beacon Press, 2000) -- each one of them highly recommended. All rights reserved by the authors.

Pictures: Illustrations for Kenneth Grahame's The Wind in the Willows and Frances Hodgson Burnett's The Secret Garden by Inga Moore, plus one illustration for E. Nesbit's The Railway Children. All rights reserved by the artist.

September 30, 2020

The writer's journey

What makes the writer's journey exhilarating, says Eleanor Cameron, is that "one never knows what will emerge from the unconcious, memories that, suprisingly enough, begin coalescing into a pattern, only dimly perceived at first. But before long, for some mysterious reason, this pattern begins taking on the substance and detail that tell the writer that another novel, not necessarily of the past, is coming into being.

"It is something to be grateful for because it can be devastating to see nothing in the offing. I remember Lloyd Alexander saying, when I congratulated him on his latest book, 'Oh, but I haven't an idea what to do next. It's terrible -- I'm utterly barren and it frightens me!' He had not the faintest notion that The First Two Lives of Lukas-Kasha would appear within the next two years, not to speak of the Westmark Trilogy during the four after that.

"There are seven lines near the end of Cavafy's poem 'Ithaka' that particularly move me:

Keep Ithaka always in your mind.

Arriving there is what you are destined for.

But do not hurry the journey at all.

Better if it lasts for years,

so you are old by the time you reach the island,

wealthy with all you have gained on the way,

not expecting Ithaka to make you rich.

"As we sit at our desks, struggling to bring a conception into existence, we are always trying -- if we are serious and not simply working for money and attention -- to make ourselves worthy of the vision, no matter how modest the accomplishment. There, for me at least, lies the mingled hardship and true joy of writing, the journey taken."

''The life journey is a hero's journey," John Rowe Townsend agrees. "Although we may not feel very heroic, we are all embarked on the heroic quest, to live lives that have meaning for ourselves and others. We are on our individual Odysseys, our personal roads of trials. We have had our adventures, and we shall have more, but we shall come to Ithaka at last.''

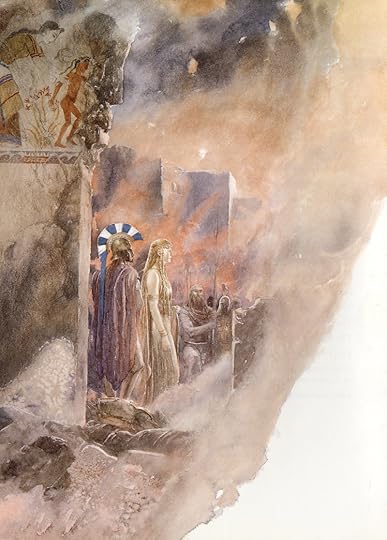

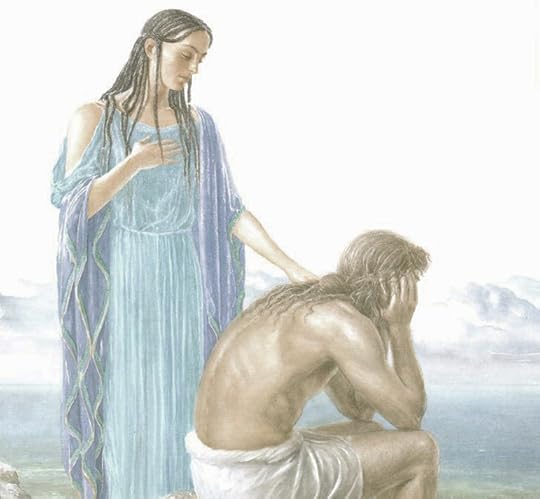

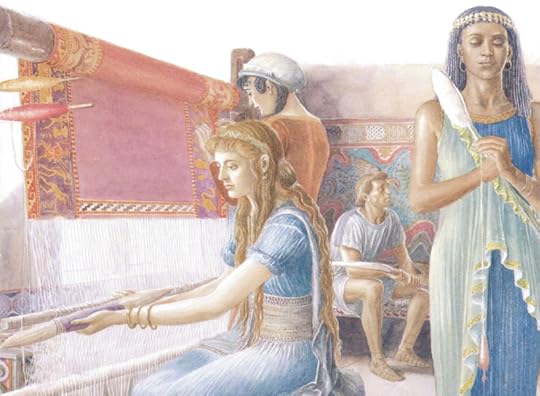

The art today is from The Wanderings of Odysseus by Rosemary Sutcliffe (1920-1992), a re-telling of the Odyssey for young readers, sumptuously illustrated by Alan Lee. Go here for an interesting interview with Alan on this book and many others.

Words: The Eleanor Cameron and John Rowe Townsend quotes are from Innocence & Experience: Essays & Conversations on Children's Literature, edited by Barbara Harrison and Gregory Maquire (Lothrop Lee & Shepard, 1987). The poem in the picture captions is from C.P. Cavafy: Collected Poems(Princeton University Press, 1975). All rights reserved by the authors or their estates.

Pictures: The illustrations above are from The Wanderings of Odysseus by Rosemary Sutcliff (Frances Lincoln, 1995). All rights reserved by the artist.

For the storytellers

"Stories, like people and butterflies and songbirds' eggs and human hearts and dreams, are also fragile things, made up of nothing stronger or more lasting than twenty-six letters and a handful of punctuation marks. Or they are words on the air, composed of sounds and ideas-abstract, invisible, gone once they've been spoken -- and what could be more frail than that? But some stories, small, simple ones about setting out on adventures or people doing wonders, tales of miracles and monsters, have outlasted all the people who told them, and some of them have outlasted the lands in which they were created."

- Neil Gaiman (Fragile Things: Short Fictions & Wonders)

On writing for children...and ourselves

"Children's fiction has a long and noble history of being dismissed," writes Katherine Rundell (in Why You Should Read Children's Books Even Though You Are So Old and Wise). "Martin Amis once said in an interview: "People ask me if I ever thought of writing a children's book. I say: 'If I ever had a serious brain injury I might well write a children's book.' There is a particular smile that some people give when I tell them what I do -- roughly the same smile I'd expect had I told them I make miniature bath furniture out of matchboxes, for the elves.

" Particularly in the UK, even when we praise, we praise with faint damns: a quotation from The Guardian on the back of Alan Garner's memoir Where Shall We Run To? read: 'He has never been just a children's writer: he's far richer, odder and deeper than that.' So that's what children's fiction is not: not rich or odd or deep.

Particularly in the UK, even when we praise, we praise with faint damns: a quotation from The Guardian on the back of Alan Garner's memoir Where Shall We Run To? read: 'He has never been just a children's writer: he's far richer, odder and deeper than that.' So that's what children's fiction is not: not rich or odd or deep.

"I've been writing children's fiction for more than ten years now, and still I would hesitate to define it. But I do know, with more certainty than I usually feel about anything, what it is not: it's not exclusively for children. When I write, I write for two people: myself, age twelve, and myself, now, and the book has to satisfy two distinct but connected appetites. My twelve-year-old self wanted autonomy, peril, justice, food, and above all a kind of dense atmosphere into which I could step and be engulfed. My adult self wants all those things, and also: acknowledgement of fear, love, failure; of the rat that lives within the human heart. So what I try for when I write -- failing often, but trying -- is to put down in as few words as I can the things that I most urgently and desperately want children to know and adults to remember. Those who write for children are trying to arm them for the life ahead with everything we can find that is true. And perhaps, also, secretly, to arm adults against those necessary compromises and necessary heartbreaks that life involves: to remind them that there are and always will be great, sustaining truths to which we can return."

"In an age that seems to be increasingly dehumanized," Lloyd Alexander once noted, "when people can be transformed into non-persons, and where a great deal of our adult art seems to diminish our lives rather than add to them, children's literature insists on the values of humanity and humaneness."

"We who hobnob with hobbits and tell tales about little green men are used to being dismissed as mere entertainers, or sternly disapproved of as escapists," said Ursula K. Le Guin in her acceptance speech for the National Book Award (for The Farthest Shore, 1972). "But I think perhaps the categories are changing, like the times. Sophisticated readers are accepting the fact that an improbable and unmanageable world is going to produce an improbable and hypothetical art. At this point, realism is perhaps the least adequate means of understanding or portraying the incredible realities of our existence."

The Katherine Rundell quote above is from her delightful little book Why You Should Read Children's Books Even Though You Are So Old and Wise (Bloomsbury, 2019). The Ursula K. Le Guin quote is from The Language of the Night: Essays (Women's Press edition, 1989). Both volumes are highly recommended. I'm sorry, but I can't remember where that particular quote by Lloyd Alexander is from -- I foolishly scribbled it down without attribution. All rights to the text reserved by the authors or their estates.

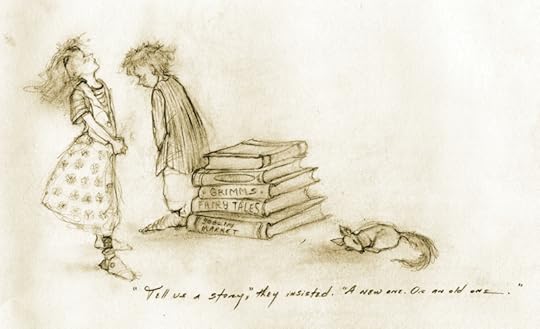

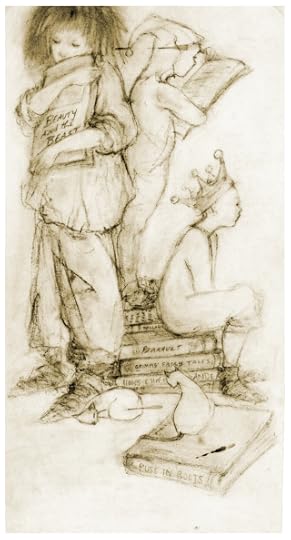

The pictures above are some random little sketches of mine, titled: Her Precious Fairy Tale Book, Storybooks, Some Little People, More Little People, Bunny Sisters (Family Portrait), and Tell Us a Story.

September 29, 2020

Telling stories back to the land

I was delighted to learn that Sharon Blackie (author of If Women Rose Rooted, etc.) also uses the term "re-storying" the land to describe the role that mythic artists can play to help restore our imaginative and physical connection to the beautiful, ailing planet we live on. Re-wilding, re-storying, re-engaging with the natural world in whatever place that we live -- urban, suburban, or rural -- is creative work, restoration work, justice and healing work all in one.

In an essay for the Center for Humans and Nature, Sharon writes:

"There are two key elements to this work of re-storying the Earth: first, coming to know the stories which are already existent in the land, and second, weaving our own stories into the fabric of the land, by engaging with it in ongoing acts of co-creation.

"When the places and features of the landscape are tied to its old stories, knowing and remembering those stories as we walk through the land can help to weave us into its history, connecting us to ancestral voices and raising our awareness of the continuity of human relationship with the place -- so helping us to establish meaningful and enduring bonds with the land in which we live."

You can read the full essay here.

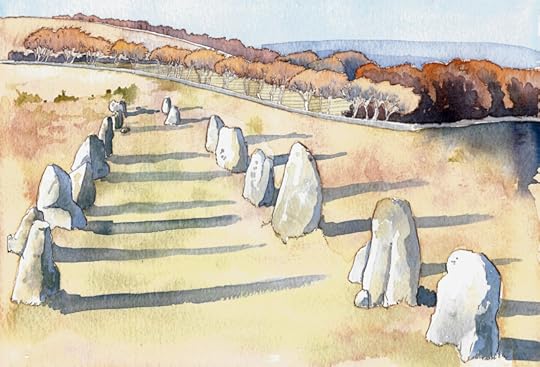

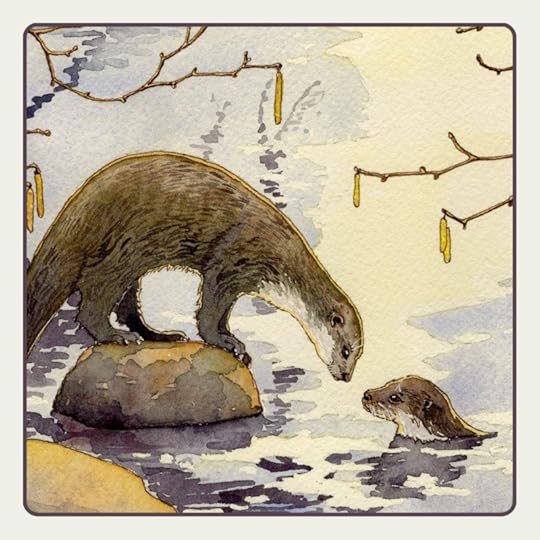

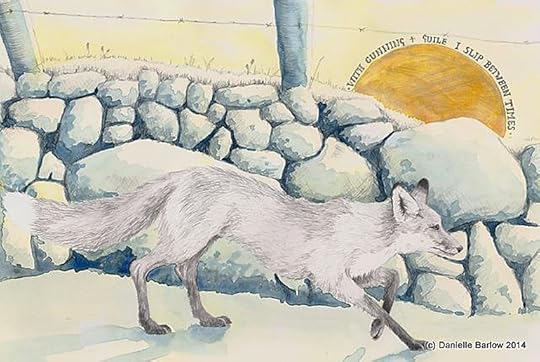

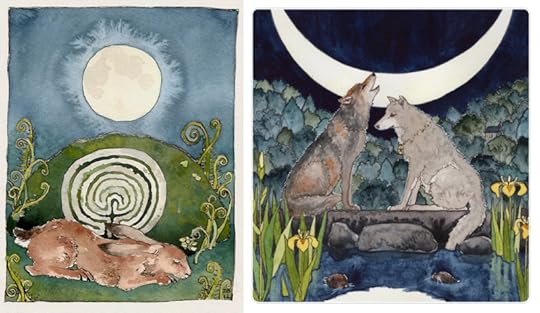

I can't think of an artist whose life and work embodies this more than my friend and village neighbour Danielle Barlow. Painter, illustrator, herbalist, incense maker, pony keeper, moor woman, myth spinner and hedgewitch, she is constantly listening to the whispered stories of Dartmoor, and weaving tales of her own into the land's Dreaming.

"I trained in textiles, and then in horticulture," she writes, "before returning to painting, my first love. These days I work primarily in ink and watercolour. I still juggle all three elements - painting, stitching and herbalism. Deeply rooted in this ancient landscape of ours, my work draws heavily on folklore and mythology, and explores the deep connection, both physical and spiritual, between people and the land they inhabit. The spirit of this land has sunk deep into my heart, and as I wander its ancient tracks, I find myself endlessly fascinated by the shifting relationships between human, animal, plants and land. My paintings above all attempt to capture the elusive ���Genius Loci - Spirit of Place���."

Visit Danielle's website to see more of her work, including her beautiful, Dartmoor-inspired oracle deck. Visit her Facebook page to see new pieces, works-in-progress, and sumptuous photographs of the green world around her; and to learn more about her process as she works with paints, textiles, and plants. You'll also find her on Instagram and Etsy. She has recently finished the enormous labour of creating a new tarot deck, The Witches' Wisdom Tarot (Hay House Publishers), in collaboration with writer Phyllis Curot. Many Chagford friends and neighbours posed for the artwork in this one (including me). It comes out at the end of October, and can be pre-ordered on Amazon UK here, and Amazon US here.

All rights to the quoted text and imagery above reserved by Sharon Blackie and Danielle Barlow.

September 27, 2020

Tunes for a Monday Morning

I'm thinking about deer on this brisk autumn morning -- but the stags and hinds of the folk tradition tend to be hunted and haunted, and their stories rarely end well (for the deer). Chased by keepers and kings, they run to the dark of the forest, and leap into the heart of enchantment. Following their trail is never a safe proposition, as folk and fairy tales tell us over and over. The trail leads to death, or a life transformation, and we never know which it will be.

Above: "Abbots Bromley Horn Dance" by Stick in the Wheel. This folk dance is performed each year in Staffordshire, and dates back at least to the Middle Ages, with older pagan roots. The precise meaning of the original dance can only be speculated, but it may have been a form of sympathetic magic to bring about a successful hunt, honouring the deer and the hunters alike. The video animation above is by Teresa Elizabeth Lobos, with archival footage from the village of Abbots Bromley.

Below: "Johnny O' Bredislee" (Child Ballad #114) performed by the great English folksinger June Tabor. This sad tale of a young man poaching the king's wild deer comes can be found on June's eleventh album, Aleyn (1997).

Above: "The Famous Flower of Serving Men" (Child Ballad #106 ) performed by Martin Carthy, another of the great musicians behind the revival of British folk music in the 20th century. The song originally appeared on Carthy's album Shearwater (1972) -- and inspired Delia Sherman's novel Through a Brazen Mirror, and a portion of Ellen Kushner's Thomas the Rhymer.

Below: "Geordie" (Child Ballad #209) performed by Silly Sisters (Maddy Prior and June Tabor) on their self-titled debut album (1976). It's the story of a man caught poaching in the king's greenwood and a woman determined to save him from hanging.

Above: "King Henry" (Child Ballad #32) performed by The Furrow Collective (Lucy Farrell, Rachel Newton, Emily Portman, and Alasdair Roberts) -- a ghostly story that starts with a deer hunt, proceeds to the after-hunt feast, and then gets progressively stranger. Martin Carthy, who also sings the ballad, once referred to it as "Beauty and the Beast reversed, originating in the Gawain strand of the Arthurian legend. The King Henry in the ballad probable never existed, since the point of the tale is that chivalry has its own rewards."

Below: "Sheaf and Knife" (Child Ballad #16) performed by Eliza Carthy (Martin Carthy's daughter, of the Carthy-Waterson folk music clan). This tale of incest and murder is dark even by Child Ballad standards, which is dark indeed. Carthy's wonderful version appeared on her album Heat Light & Sound (1996).

Above: "The Keeper," a traditional English folk song ostensibly about hunting the doe, but with obvious sexual connotations -- performed here by Sam Kelly and the Lost Boys, from their album Pretty Peggy (2017).

Below: "The Death of the Hart Royal" performed by Faustus (Paul Sartin, Benji Kirkpatrick, and Saul Rose). This unusual ballad of Robin Hood, Lord of the Greenwood, was found in the archives of Somerset folk song collector Ruth Tongue. The band recorded it for their third album, Death and Other Animals (2017), when they were Artists in Residence at Halsway Manor, the National Folk Arts Centre in Somerset's Quantock Hills.

Following the deer

"As long as people have lived or hunted alongside the deer's habitats," says writer and mythographer Ari Berk (in "Where the White Stag Runs"), "there have been stories: some of kindly creatures who become the wives of mortals; or of lost children changed into deer for a time, reminding their kin to honor the relationship with the Deer People, their close neighbors. And there are darker tales, recalling strange journeys into the Otherworld, abductions, and dangerous transformations that don't end well at all. But all stories about the deer share some common ground by showing us that the line between our world and theirs is very thin indeed."

Ovid's Metamorphoses, Ari continues, tells the story "of youthful Actaeon who spends the day hunting with his dogs on the hillsides, catching so much game that the slopes run red with blood. As the sun ascends the sky, he calls off the chase, bidding his comrades retire with the promise of renewing the hunt early the next day. Then he does a dangerous thing: he wanders for a time in a wood he does not know, and so comes by accident to the sacred grotto where Diana is accustomed to bathe with her nymphs. To Actaeon's great misfortune, he spies the goddess of the hunt naked and she, seeing him, blushes. Then lifting up her hands, she throws water in Actaeon's face and he flees that place. As he wanders back to find his friends he hears his dogs barking and sees that they are chasing him. Confused he calls out to them, but instead of his voice, he hears the bellowing of a great stag, for stag he now is, transformed by the goddess's vengeful hand. So he runs fast on four legs but soon his dogs chase him down and, tearing him apart, find their old master toothsome indeed. The myth of Actaeon is an early example of the connection of deer stories with the violation of taboos. Actaeon made three fatal errors: overhunting the hillside, entering a sacred enclosure unknowingly, and gazing upon the virgin mistress of the hunt. His punishment is perfectly suited to address his errors for he learns to see the world, though briefly, from the perspective of a shy creature who calls the wild home and instinctively respects its boundaries.

"In the medieval Welsh Mabinogion, does and stags appear as physical manifestations of the boundary between worlds. In the story of 'Pwyll,' the deer are followed into the forest during a hunt. But Pwyll, the prince, and his dogs are soon separated from his companions and he finds himself lost in the woods. Soon he hears other dogs and, following their barking, comes upon a clearing in the woods where he finds a strange pack���red-eared and white-furred���bearing down upon a stag. Pwyll chases those dogs off and sets his own upon the stag instead, most discourteously. When he later meets the owner of the white dogs���who is none other than the Arawn, lord of the Otherworld���satisfaction is demanded and Pwyll must repay Arawn by assuming his form and exchanging places, traveling into the Otherworld to kill one of Arawn's enemies. So following the deer is often a way into the Otherworld, or a sign that we are very close to its borders."

as crows fly

in the dawn light

on the cold hill

the deer are running

the thud of their hooves

on the bed of the stream

is the drum that rocks

the roots of the birch

and the wind that shakes

the birch tree���s leaves

- Scottish poet Chris Powici (from "Deer")

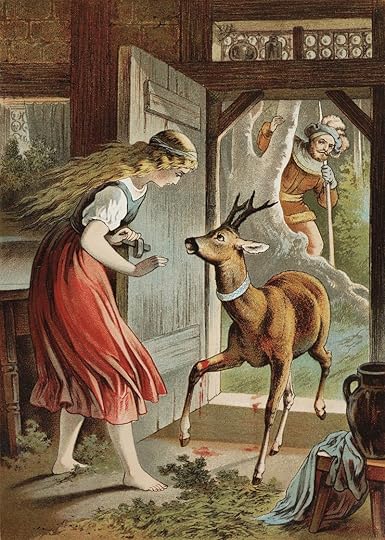

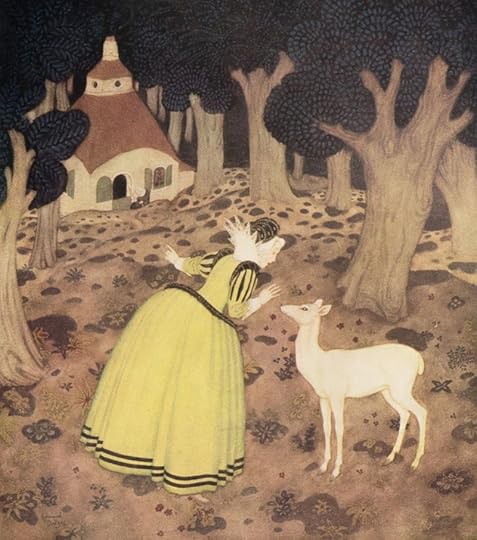

Deer that roam the Western fairy tale tradition are guardians, guides, companions to the fairies, and occasionally fairies themselves in disguise -- or else they are men and women be-spelled, roaming the woods in animal-shape by day, briefly regaining their humanity each night. In Brother and Sister from Grimms' Fairy Tales, for example, two siblings flee their wicked stepmother through a dark and fearsome forest. The path of escape lies across three streams, and at each crossing the brother stops, intending to drink. Each time his sister warns him away, but the third time he cannot resist. He bends down to the water in the shape of a man and rises again in the shape of a stag. Thereafter, the sister and her brother-stag must live in a lonely hut in the woods . . . but eventually, with his sister���s help, (and after she marries a king), the young man resumes his true shape.

Ellen Steiber looked at this tale's archetypal patterns when writing her contemporary version, "In the Night Country" (published in The Armless Maiden). "Fairy tales are journey stories," she says in a beautiful essay on the subject. "They deal with initiation and transformation, with going into the forest where one's deepest fears and most powerful dreams are realized. Many of them offer a map for getting through to the other side. Out of curiosity, I went back to the patterns of three in [Brother and Sister], since the very rhythms of repetition set them off and give them importance. There are three brooks, three days of the hunt, and three times that the queen's ghost speaks [after the sister's marriage to the king, when her role as queen has been usurped by her step-sister]. Each of these patterns presents challenge and transformation; they are the places of power in the story, the points where true magic occurs. In the first the brother is thirsty; he needs nourishment and finally gets it, a difficult metamorphosis being the price. In the second he must either follow his own deer nature or 'die of grief'; at great risk he runs with the hunt, and that act takes both brother and sister farther along on the path they must travel to a new state of being. (It's worth noting that in the fairy tales one can rarely remain in the forest ��� one takes what was found there and brings it back into the world.) In the third challenge, the king must recognize the [true] queen, an act that will restore her to life and lead to a redress of wrongs, a final ending of the curse, a coming into balance. As abuse [in a family] takes many forms, so does salvation. Here are three of many acts that can get you through: nourishing yourself, following your heart even at great risk, and being seen for what you are."

Beloved, what can be, what was,

will be taken from us.

I have disappointed.

I am sorry. I knew no better.

A root seeks water.

Tenderness only breaks open the earth.

This morning, out the window,

the deer stood like a blessing, then vanished.���

- American poet and essayist Jane Hirshfield (from "Standing Deer")

In The White Deer (a.k.a. The White Hind and The White Doe), from the French fairy tales of Madame d���Aulnoy, a princess is cursed in infancy by a fairy who'd been insulted by her parents. Disaster will strike, says the fairy, if the princess sees the sun before her wedding day. Many years later, as she travels to her wedding, a ray of sun penetrates her carriage. The princess turns into a deer, jumps through the window, and disappears into the forest -- where she's eventually hunted by her own fianc��, who does not know what she has become.

As she flees the arrows of the royal hunting party, the prince is as "unescapable as memory" in this passage from Eve Sweetser's poem, "The White Hind at Bay":

She leads him through briars, bogs

scent-killing brooks ��� inexorably

the following fate comes on.

Always, till now, some twist has let her out.

In exhaulted desperation

she sees the cliff before her.

From teeth and knives

her white hide is no protection

"Leave off these fawnish fantasies,

her kind deer parents often said

"What's a white skin?

Does every third-born son

wed a princess?"

Can wild hope save her?

Can she be again

the princess she was in childhood

(or was it dreamed of?)

exquisite and beloved,

ideal and human both?

It is so far ��� so long ago

she left off thinking of glass slippers

accepted her four hooves.

two deer

came walking down the hill

and when they saw me

they said to each other, okay,

this one is okay,

let���s see who she is

and why she is sitting

on the ground like that,

so quiet, as if

asleep, or in a dream,

but, anyway, harmless;

and so they came

on their slender legs

and gazed upon me

not unlike the way

I go out to the dunes and look

and look and look

into the faces of the flowers;

and then one of them leaned forward

and nuzzled my hand, and what can my life

bring to me that could exceed

that brief moment?

- American poet Mary Oliver (from "The Place I Want to Get Back To")

"Deer is a common figure in American Indian myths, " notes Ari Berk, "often appearing in stories that continue the focus on families, kinship, marriage, child-rearing, hunting and pursuit. Among the Pueblos of the New Mexico, stories are still told of Deer Boy, a baby left in the grass, abandoned by its young mother, a girl of the village. It was a Deer Woman who found the human child and brought him home to raise with her own fawns. Time passed and the boy spent the days running with his fawn brothers and sisters. Some time later, a hunter from the village noticed strange tracks among those left by the Deer People. The Deer Woman knew the time had come for the boy to return to his people. She readied him to be caught by the hunter and told him what he must know about his real mother and what she looked like. She told him that to remain among his own people he must, upon returning to the village, be left alone and unseen in a room for four days. So he was found by the hunter and taken home and much happiness attended his homecoming. The boy told his family he must be left alone for four days and they agreed. But his birth mother, so impatient was she, stole a glance at her son before the four days were finished. In an instant the boy took on the shape of a deer and ran to the North where he joined his other mother and lived for the rest of his days among the Deer People."

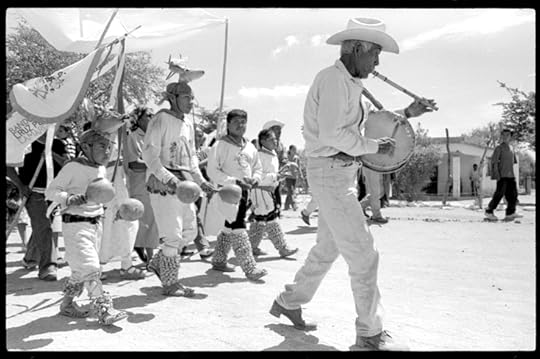

The Yaqui (Yoeme) people of the Sonoran desert traditionally divide themselves into two related groups: the Vato'im (Baptized Ones), who remain in this world and integrate seventeenth century Spanish Catholicism with the rites of their own aboriginal religion, and the Surem (the Enchanted People), who went away to the Wilderness World to preserve the ancient ways. In the extraordinary Deer Dance, still performed at Easter and other times in Arizona and northern Mexico, a dancer takes on the shape, the movements, the consciousness of the sacred deer on the borderline between these two worlds, blessing the ground he walks on. Yaqui Deer Songs by Larry Evers and Felipe S. Molina is a beautiful account of a deer mythology that is not buried in history but still living, still a vibrant part of everyday life for the modern Yoeme. "Flower-cover fawn went out, enchanted, from each enchanted flower wilderness world, he went out...," the singers sing as the deer dancer moves, gourd rattles in his hands and strings of rattles bound around his shins. A deer head rises over his own, antlers decorated with flowers. "So this now is the deer person, so he is the deer person, so he is the real deer person...." The drummers drum, the dancer leaps, and it is the real deer person indeed.

Question: Can you tell us about what he is wearing?

Well, the hooves represent the deer���s hooves,

the red scarf represents the flowers from which he ate,

the shawl is for skin.

The cocoons make the sound of the deer walking on leaves and grass.

Listen.

Question: What is that he is beating on?

It���s a gourd drum. The drum represents the heartbeat of the deer.

Listen.

When the drum beats, it brings the deer to life.

We believe the water the drum sits in is holy. It is life.

Go ahead, touch it.

Bless yourself with it.

It is holy. You are safe now.

- Tohono O'Odham author Ofelia Zepeda (from "Deer Dance Exhibition")

Native American writer and educator Carolyn Dunn describes the Deer Woman tales she grew up with in a short, poetic essay on the subject:

"Deer Woman's specific magic and myth surrounds marriage and courtship rituals," she says. "I write of Deer Woman from the Cherokee/Muskogee/Seminole/Choctaw perspective because this is what I know. But other cultures have encounters with Deer Woman or Deer Man. Ella Cara Deloria recorded several traditional Dakota and Lakota narratives which mirrored the Southeastern tribes' Deer Woman stories. The Karuk, according to the Karuk artist and storyteller Lyn Risling, have stories of the Deer Woman in which the spirit is associated with fertility and maturation rituals and prepares young women for marriage. The Southeastern stories are similar in that young people must be instructed in the choosing of a societally-approved mate in order for cultural survival and regeneration. In these stories, a beautiful young woman meets a young man and entrances him into a sexual relationship. The woman is so beautiful that the young man is often swayed by her beauty away from family, home, community. If the young man is so entranced as to not notice the young woman's feet���which in the case of Deer Woman are hooves���then he falls under her spell and stays with her forever, wasting away into depression, despair, prostitution, and ultimately, death.

"The Deer Woman spirit teaches us that marriage and family life within the community are important and these relationships cannot be entered into lightly. Her tales are morality narratives: she teaches us that the misuse of sexual power is a transgression that will end in madness and death. The only way to save oneself from the magic of Deer Woman is to look to her feet, see her hooves, and recognize her for what she is. To know the story and act appropriately is to save oneself from a lifetime lived in pain and sorrow; to ignore the story is to continue in the death dance with Deer Woman. Deer Woman instructs us that sexual attraction does not a proper marriage make; it is the societal and cultural responsibility of each tribal member to choose a mate wisely���therefore ensuring tribal survival into the next generation. Both the Karuk stories and the Southeastern stories illustrate this cultural responsibility."

Muskogee/Creek author Joy Harjo finds Deer Woman in a bar late on a winter's night in her haunting prose-poem "Deer Dancer":

"She was the myth slipped down through dreamtime. The promise of feast we all knew was coming. The deer who crossed through knots of a curse to find us. She was no slouch, and neither were we, watching.

"The music ended. And so does the story. I wasn't there. But I imagined her like this, not a stained red dress with tape on her heels but the deer who entered our dream in white dawn, breathed mist into pine trees, her fawn a blessing of meat, the ancestors who never left."

Chickasaw writer Linda Hogan addresses the secret desire so many of us have to run away with the deer ourselves in this passage from her beautiful poem "Deer Dance":

That night, after everything human was resolved,

a young man, the chosen, became the deer.

In the white skin of its ancestors,

wearing the head of the deer

above the human head

with flowers in his antlers, he danced,

beautiful and tireless, until he was more than human,

until he, too, was deer.

Of all those who were transformed into animals,

the travelers Circe turned into pigs,

the woman who became the bear,

the girl who always remained the child of wolves,

none of them wanted to go back

to being human. And I would do it, too, leave off being human

and become what it was that slept outside my door last night,

rested in my sleep.

"Convince the deer you are one of them," advises Shauna Osborne, a Comanche/German mestiza writer from New Mexico. "Dance with them and they will show you the way. Pay strict attention to the leg positions and neck angles -- that���s where the heart of their dance lies. Deer have this natural grace, this presence, on the dance floor that just can't be beat. Once you find it, you���ll know. Do some research: Ginger Rogers had a definite tinge of deer blood in her and my mother always swore that Travolta had to be part deer. 'How else could he glide through the air like that?' she would demand. However, the best contemporary example of a deer dancer has to be, without doubt, Christopher Walken. He defies the laws of physics with such style and does it with a nonchalant matter-of-factness which all deer dancers should try to emulate. Treat his work as it should be treated -- a sacred text of the Deer Dancers. Roll with this or roll with that -- just make sure your feet never quite touch the ground. However, you must remember: when the song ends, the story does too."

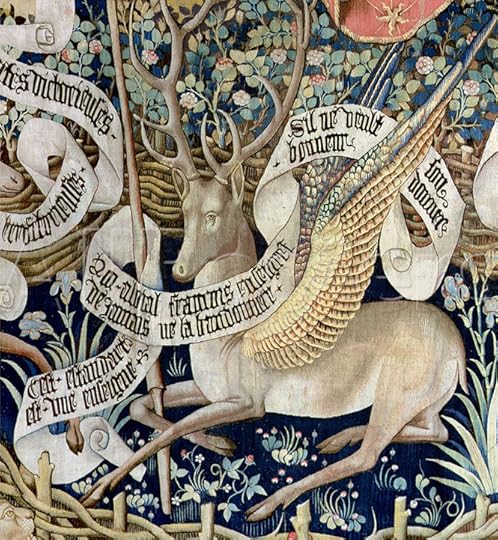

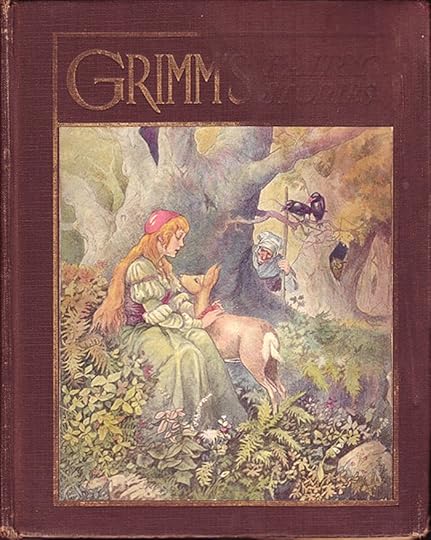

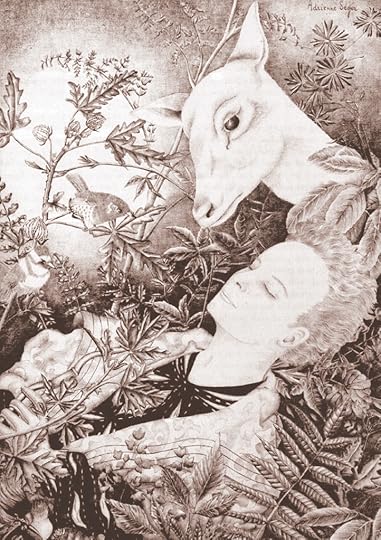

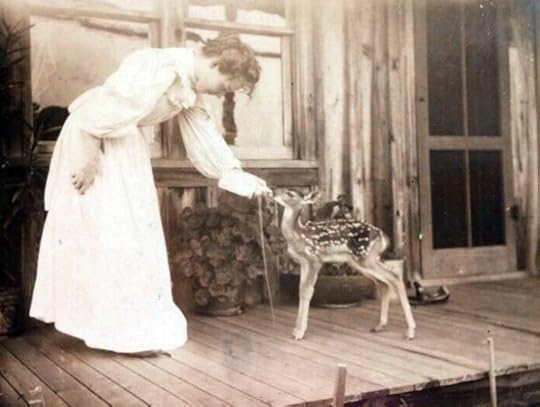

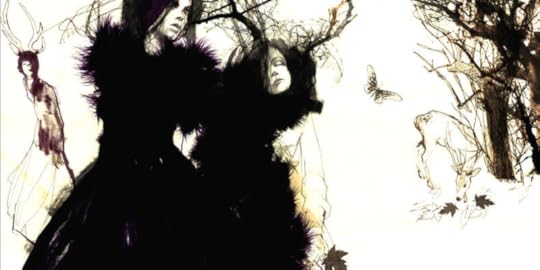

The enchanted deer imagery above is: "White Stag" photograph by Jane Baynes; "Acteon and Diana" by Domenico Veneziano (1410-1461); "The Mystic Wood" and "The Lady Clare" by John William Waterhouse (1849-1917); "Running Deer" by Alex Herbert, "Brother and Sister" (the cover image for an edition of Grimms Fairy Tales) by John Barton Gruelle (1880-1938); ���Brother and Sister��� by Carl Offterdinger (1829-1889); "Perched" by Kelly Louise Judd; "Brother and Sister" by Edmund Dulac (1882-1953); "The White Deer" by Adrienne S��gur (1901-1981); "All by Grandmothers" by Kristin Vestgard; an old photograph (provenance unknown); "The Deer Woman" by Susan Seddon Boulet (1941-1997); "Easter Procession, Rancho Camargo, Sonora" (from the "Miners & Mayos" photography series) by David Bacon; "Deer Dancer" portrait by Kyle Bowman; "The Deer Man" and "The Deer Woman" by Wendy Froud; "Deer Maiden" bronze by Erich Schmidt-Kestner (1887-1941); "Born" by Kiki Smith; three deer sketches by Daniel Egn��us; and a deer photograph (provenance unknown). All rights to the prose, poetry and art above reserved by the authors and artists.

This piece first appeared on Myth & Moor back in 2013. For more deer poetry, art, and lore, go to these follow-on posts: Following the Deer: Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, and L'Envoi.

September 26, 2020

Imagining a different kind of world

From an interview with Lev Grossman (author of The Magician trilogy), in which he is asked for his definition of fantasy literature:

"My working definition? Any book with magic in it. It���s crude but effective. It helps if you take the long view, historically speaking, because it���s not like J.R.R. Tolkien invented fantasy with The Hobbit. Take a giant step back and you can���t help but notice that the greater part of all human literature is fantasy, in the sense that it has monsters and magic and things like that in it. Shakespeare is infested with ghosts and spirits and witches. Look at Spenser. Look at Dante. Look at Ovid, or Homer. Go back past the 18th century and practically everything could be called fantasy.

"My working definition? Any book with magic in it. It���s crude but effective. It helps if you take the long view, historically speaking, because it���s not like J.R.R. Tolkien invented fantasy with The Hobbit. Take a giant step back and you can���t help but notice that the greater part of all human literature is fantasy, in the sense that it has monsters and magic and things like that in it. Shakespeare is infested with ghosts and spirits and witches. Look at Spenser. Look at Dante. Look at Ovid, or Homer. Go back past the 18th century and practically everything could be called fantasy.

"It���s only relatively recently, at the start of the 18th century, that you see the arrival and dizzying ascent of what we might broadly call realism. Suddenly, around about Robinson Crusoe or so, Western culture was seized by this powerful idea that literature was supposed to resemble real life, and fictional worlds were supposed to behave like the real world, as it was coming to be understood by scientists, and anything that didn���t do so wasn���t literature. Magic and the supernatural were exiled to other, lesser categories: Gothic fiction, fairy tales, ghost stories, children���s books, fantasy. A lot of people still think it belongs there."

"There is a specific modern tradition of fantasy fiction," he clarifies, "that starts in the 1920s and 1930s in England and America with writers like Lord Dunsany and Hope Mirrlees, and which really takes off with C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien, as well as T.H. White and Robert E. Howard....That generation -- the ones who were writing in the 1920s and '30s -- had been the victim of a historical trauma: They bore witness to a period of catastrophic social and technological change. The Victorian world of their childhood was shattered and swept away by the 'advances' of the early 20th century -- the electrification of cities, the rise of mass media, the replacement of horses by cars, the rise of psychoanalysis, the invention of mechanised warfare. As a result, the world that they found themselves in as adults was virtually unrecognisable to them.

"Some of those writers responded to this cataclysm by creating strange, fragmented masterpieces that we now know as literary modernism: Joyce, Hemingway, Kafka, Woolf, Faulkner and so on. Gertrude Stein famously called them the Lost Generation, and she wasn���t wrong. But other writers -- like Lewis and Tolkien, who were both veterans of the Somme -- wrote fantasy instead. They used it as a way to express their sense of longing for a lost world, an idyllic, more grounded, more organic, more connected world that they would never see again. They were part of the Lost Generation too."

Returning to these ideas in his essay "What is Fantasy About?," Lev notes that "longing" is a prominent theme in fantasy: the longing for a lost world, or a better one.

"Lewis and Tolkien were virtuosos of longing," he writes. "They had, after all, lost a world, the world of their Victorian childhoods....They lived through, if not a singularity, then a pretty serious historical inflection point, and they longed for that pre-inflected world. (Laura Miller writes about this really compellingly, albeit somewhat differently, in The Magician���s Book, her excellent book about Narnia. She quotes Lewis on his special notion of Joy: 'an unsatisfied desire that is itself more desirable than another satisfaction.')

"We too have lived through an inflection point: a great deal of technological and social change. We can lay claim to a certain amount of longing.

"Longing for what exactly? A different kind of world. A world that makes more sense -- not logical sense, but psychological sense. We���re surrounded by objects that we don���t understand. Like iPods -- they���re typical. They���re gorgeous, but they���re also really alienating. You can���t open them. You can���t hack them. You don���t even really know how they work, or how they���re made, or who made them. Their form is abstractly beautiful, but it has nothing to do with their function. We really like them, but it���s somehow not a liking that makes us feel especially good.

"The worlds that fantasy depicts are very different from that. They tend to be rural and low-tech. The people in a fantasy world tend to be connected to it -- they understand it, they belong in it. People in Narnia don���t long for some other world (except when they long for Aslan���s Land, which I always found unsettling). They���re in sync with it....To be sure, fantasy worlds are often animated by weird mysterious forces -- like magic -- but even those forces on some level come from inside us. They���re not made in China. They express deep human wishes and primal emotions. Likewise the worlds of fantasy are inhabited by demons and monsters, but only because we���re inhabited by monsters, the ones that live in our subconsciouses (subconsci?) Those monsters are grotesque and not-human, and sometimes they even destroy us, but we recognize them instinctively.

"This longing for a world to which we���re connected -- and not connected Zuckerberg-style, but really connected, like a dryad with its tree ��� surfaces in a lot of places these days, not just in fantasy. You see it in the whole crafting movement ��� the Etsy/Makerfaire movement. You see it in the artisanal food movement. And it you see it in fantasy."

For more of Lev Grossman's thoughts on the evolution of fantasy, I recommend "Fear and Loathing in Aslan's Land," the third annual J.R.R Tolkien Lecture on Fantasy Literature at Pembroke College (Tolkien's college), Oxford, in 2015.

The passages above are from "Lev Grossman on Fantasy" ( on Five Books.com) and "What is Fantasy About?" on Lev Grossman's blog (November, 2011). The Lisel Mueller poem in the picture captions was first published in The New Yorker (November, 1967) and also appears in her book Alive Together: New & Selected Poems (Louisiana State University Press, 1996), which I highly recommend. All rights reserved by the authors.

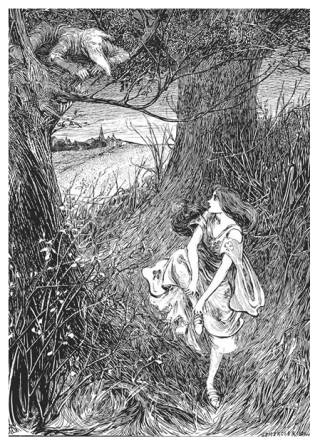

The text for this post is from the Myth & Moor archives (Nov. 15, 2018), re-visited as part of our conversation about stories and fantasy this week -- with new photographs of a walk (and swim) on a beautiful autumn morning here in Chagford. The drawing is by British book artist Helen Stratton (1867-1961). Her body of work is delightful, and ought to be better known.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 710 followers