Terri Windling's Blog, page 29

August 12, 2020

Fantasy and poetic truth

From "The Flat-Heeled Muse" by Lloyd Alexander (1924-2007):

"The Muse in charge of fantasy wears good, sensible shoes. No foam-born Aphrodite, she vaguely resembles my old piano teacher, who was keen on metronomes. She does not carry a soothing lyre for inspiration, but is more likely to shake you roughly awake at four in the morning and rattle a sheaf of subtle, sneaky questions under your nose. And you had better answer them. The Muse will stand for no nonsense (that is, non-sense). Her geometries are no more Euclidean than Einstein���s, but they are equally rigorous."

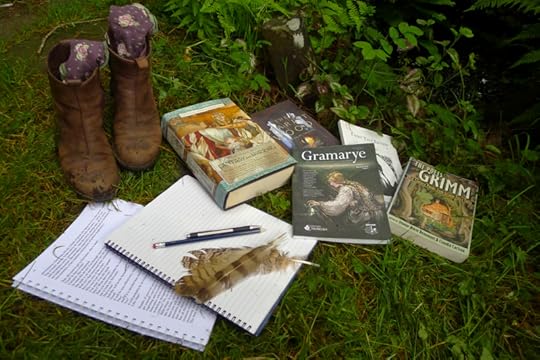

As a woman who roams the woods of Devon in scuffed old walking boots, I love the idea that the fantasist's Muse wears sensible shoes. I can picture her clearly: bramble-torn sweater, skirt damp from the river, mud on her cheek and moss in her hair...and okay, I admit that's a description of this writer too, but never mind. Alexander is making a serious point here about the craft of writing fantasy. The magic, he says, isn't made out of moonbeams and gossamer wings; it comes from what's real and earthy and true:

"The less fantastic it is, the stronger fantasy becomes. The writer can painfully bark his shins on too many pieces of magical furniture. Enchanted swords, wielded incautiously, cut both ways. But the limits imposed on characters and implements must be more than simply arbitrary. What does not happen should be as valid as what does. In The Once and Future King, for example, Merlyn knows what will happen in the future; he knows the consequences of Arthur's encounter with Queen Morgause. Why doesn't he speak out in warning? It is not good enough to say, 'Well, that would spoil the story.' Merlyn cannot interfere with destiny; but how does T. H. White show this in specific detail? By having Merlyn grow backwards through time. Confused in his memories, he cannot recollect whether he has already told Arthur or was going to tell him. No more is needed. The rationale is economical and beautiful, fitting and enriching Merlyn's personality.

"Insistence on plausibility and rationality can work for the writer, not against him. In developing his characters, he is obliged to go deeper instead of wider. And, as in all literature, characters are what ultimately count. The writer of fantasy may have a slight edge on the realistic novelist, who must present his characters within the confines of actuality. Fantasy, too, uses homely detail, but at the same time goes right to the core of a character, to extract the essence, the very taste of an individual personality. This may be one of the things that makes good fantasy so convincing. The essence is poetic truth.

"The distillation process, unfortunately, is unknown and must be classed as a Great Art or a Major Enchantment. If a recipe existed, it could be reproduced; and it is not reproducible. We can only see the results. Or hear them. Of Kenneth Grahame -- and the same applies to all great fantasists -- A. A. Milne writes: 'When characters have been created as solidly...they speak ever after in their own voices.'

"These voices speak directly to us. Like music, poetry, or dreams, fantasy goes straight to the heart of the matter. The experience of a realistic work seldom approaches the experience of fantasy. We may sail on the Hispaniola and perform deeds of derring-do. But only in fantasy can we journey through Middle Earth, where the fate of an entire world lies in the hands of a hobbit.

"Fantasy presents the world as it should be. But 'should be' does not mean that the realms of fantasy are Lands of Cockaigne where roasted chickens fly into mouths effortlessly opened. Sometimes heartbreaking, but never hopeless, the fantasy world as it "should be" is one in which good is ultimately stronger than evil, where courage, justice, love, and mercy actually function. Thus, it may often appear quite different from our own. In the long run, perhaps not. Fantasy does not promise Utopia. But if we listen carefully, it may tell us what we someday may be capable of achieving."

Go here to read Alexander's essay, "The Flat-heeled Muse," in full. It is a delight.

Words: The passages above are from "The Flat-heeled Muse" by Lloyd Alexander, published in The Horn Book (April, 1965). The fairy poem in the picture captions is from Poetry (November 2019). All rights reserved by the authors. Pictures: An encounter on our morning walk.

August 11, 2020

Little shape-shifters

In the video above, Cornelia Funke (author of The Thief Lord, Inkheart, etc.) speaks about the need for wilderness in children's lives. "Kids are so very good at still being shape-shifters, and shifting into feathers and fur. They still understand that we are connected to everything in this world, and that we are part of an incredibly intricate woven web of life and creatures."

Born in Dorsten, West Germany, Funke began her career as a social worker focused on children from deprived backgrounds; she then became a book illustrator before turning her hand to writing fantasy for young readers. Funke and her family moved from Hamburg, Germany to California in 2005.

"I'm fascinated by stories that stem from a particular place," she says. "That started with The Thief Lord, which wouldn't have come into being if it weren't for Venice. In the stories I choose to tell, places always play the role of a hero. I have also always been interested in the non-human and our relationship to that ��� whether plants or animals or imaginary creatures. I'm interested in everything that scratches at and questions the so-called reality that we perceive.

"I'm fascinated by stories that stem from a particular place," she says. "That started with The Thief Lord, which wouldn't have come into being if it weren't for Venice. In the stories I choose to tell, places always play the role of a hero. I have also always been interested in the non-human and our relationship to that ��� whether plants or animals or imaginary creatures. I'm interested in everything that scratches at and questions the so-called reality that we perceive.

"When I'm standing on the street in Hamburg and there is one of those stepping stones under my feet, which is there to remind me of the Jews that were deported from the house I'm standing in front of, then that hugely scratches at the reality I find myself in at that moment. I might just have come back from a peaceful walk across the Isemarkt market square, for example. It scratches at my reality when a bird flies by me and I imagine how it views reality. It scratches at my reality when someone passes me by who has a different color of skin. How does that change the experience with world? We all know it does.

"It constantly scratches at my reality that we can perceive this world so differently. I find it absurd I'm asked so often why I write fantasy, because I think that reality is fantastic. And the only way to get closer to it is to write fantasy."

"I write stories I love to read myself, And I am profoundly enchanted by children and young readers, by their openness and curiosity, by their will to still ask the big questions about the world: where do we come from? What is this all about? Why is the world so beautiful and terrible at the same time? Children also still understand that we are just part of a huge web and connected to every plant and creature on this planet. They are still shape shifters and go easily into a story, whereas adults often hesitate to allow their imagination to give them feathers and wings."

Words: The Cornelia Funke quotes above are from interviews in Scroll.in (Dec. 2, 2018) and DW (Oct. 12, 2018). The video is from The Wilderness Society (Feb. 17, 2012). All rights reserved by Cornelia Funke.

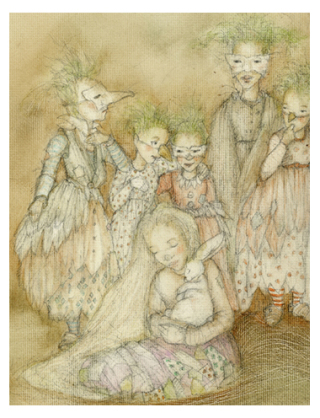

Pictures: A detail from my painting "The Dreaming," three little shape-shifters, and "The Lost Child." All rights reserved.

August 10, 2020

Tunes for a Monday Morning

As many of you know, I spent much of 2018 - 2019 happily immersed in the Modern Fairies project, an arts and research initiative which brought folk musicians, artists, writers, folklorists and filmmakers together to create works exploring what Britian's folklore tradition means to us in the modern world. After twelve months of research and collaboration, the project ended with a concert and multi-media presentation at the Sage Theatre in Gateshead/Newcastle (Spring 2019), but my MF colleagues are continuing to develop this material in a number of interesting ways -- the most recent of which is Wrackline, a gorgeous, deeply magical new album by the distinguished folksinger, songwriter, and music scholar Fay Hield.

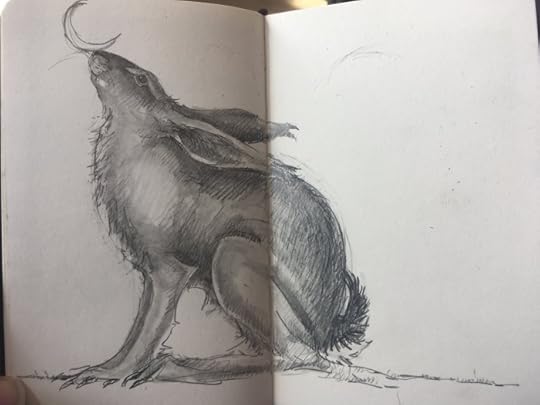

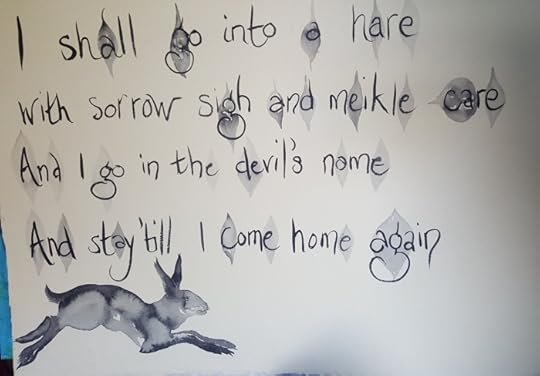

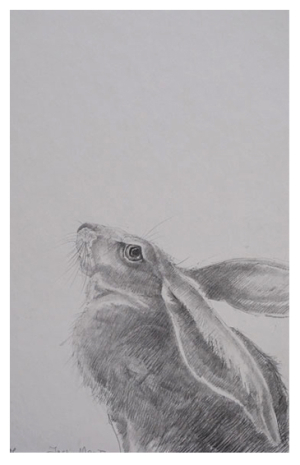

In the run-up to Wrackline's release next month, Fay is publishing posts highlighting the album's six folklore themes -- beginning with tales of witches (and other women) who cast themselves into the shapes of hares.

In the run-up to Wrackline's release next month, Fay is publishing posts highlighting the album's six folklore themes -- beginning with tales of witches (and other women) who cast themselves into the shapes of hares.

Above: A short video in which Fay introduces the concept of the new album.

Below: "Hare Spell," from Wrackline. As Fay explains:

"In exploring the mythical supernatural on the Modern Fairies project I became excited by the question of real magic and belief, and spent some time looking at magical acts themselves, rather than the stories about them. Inge Thomson and I chatted about the nature of spells and where the magic lay. Words are commonly seen to hold power, but as musicians, we wondered how we could draw this out through sound. We toyed with the relationship of music to language noticing that pitches are conveniently given letter names. That evening at the very first meeting of the Modern Fairies [at Oxford University, Summer 2018], we mused about how music could come out of the words themselves.

"I needed a spell, a real one that held magic. Jackie Morris gave me some words about a hare and a little digging showed that it comes from Isobel Gowdie, the wife of John Gilbert, likely a cottar in Auldearn, near Inverness. Isobel was tried in 1662 during the witchcraft trials and her confession gives a clear account, seemingly uncoerced, into her activities with the devil and visiting the king of the fairie. She includes several spells and chants used to conduct her own magic, including this spell to turn the utterer into a hare to do the devil���s work."

Below: "When She Comes," a second hare song which grew from a collaboration between Fay and poet Sarah Hesketh. Sarah writes:

"As I sat and listened to Fay transform her reading about Isobel Gowdie into song, I found myself really drawn into the story she was beginning to tell through the music. Here were two characters -- a woman and a hare -- with an incredibly strange and intimate relationship. Fay's song 'Hare Spell' was a glimpse into that relationship from Isobel's point of view; but what, I wondered, did the hare have to say about it all? How did he feel about having his body appropriated for her eldritch purposes? Was this a kind of hi-jacking or was there something more complex and consensual going on between the two of them? I wanted to explore the idea that the hare might be more than just a passive vessel for Isobel's adventures, and how it might feel for him to have to say goodbye as she decided to return to her own body."

The words are by Sarah and the music by Fay, with underlying chordal structures created by Ben Nicholls and Inge Thomson for Modern Fairies project, then further developed by Sam Sweeney and Rob Harbron for Wrackline. This is the Modern Fairies version, recorded at The Sage performance in April 2019. It was one my favourite songs from the show, bringing a lump to my throat every time I heard Fay sing it. (Sarah's exquisite lyrics are here.)

There are more shape-shifiting hares to come: Fay, Inge, Sarah and I are working with the good folks of the Alternative Stories podcast to create an audio drama on the subject; we'll let you when the broadcast date is set. And keep an eye on Fay's blog in the weeks ahead if you'd like to know more about the other songs on Wrackline (including one based on my poem "The Night Journey," which is an honour indeed).

Another thread of work that emerged from the Modern Fairies project was inspired by selkie (seal people) lore -- including songs created by Lucy Farrell, Inge Thompson, Barney Morse-Brown and Fay, presented in the final Modern Fairies show with art by Natalie Reid.

In the Autumn 2019, four of us from the project (Lucy, Fay, Barney, and me) reunited to present The Secrets of the Selkies: an evening of song and story at the Being Human Festival in Sheffield. During the week leading to festival, as the others ordered and rehearsed their music, my job as a writer/editor was to weave poems and monologues between the songs to join them into a common narrative, examining classic "selkie bride" folk tales from several characters' point of view. I don't know what the evening was like from the audience, but from the stage it felt like pure magic ... ending with choral singing of the selkie's call by everyone in the hall.

Above: A screen projection produced by Lucy -- with Natalie's art, Lucy's music, and selkie encounters described by Inge (who grew up on Fair Isle) and others.

Below: A little video by Tim James capturing a collage of moments from The Secrets of the Selkies.

Art above: Hares by Jackie Morris, and a selkie by Natalie Reid. The photograph of Fay's banjo is by Elly Lucas. All rights to the music and art above reserved by the musicians and artists.

To read previous posts on the Modern Fairies project, go here.

August 8, 2020

Writing from the edgelands

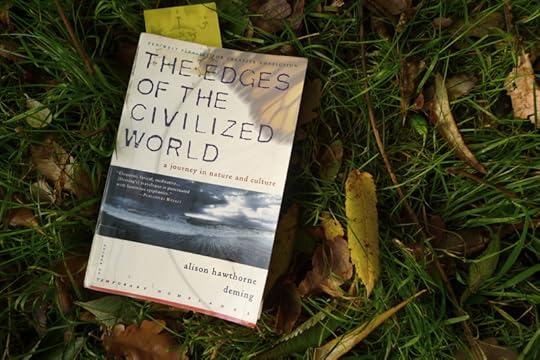

Following on from yesterday's post, here's another passage from Alison Hawthorne Deming's award-winning essay, "Poetry and Science: A View from the Divide." Once again, her words can also apply to the writing of fantasy literature, that most poetic of literary forms; specifically, to the kind of fantasy that is rooted in a strong sense of place and deeply engaged with the wild world (including imaginary wild worlds).

Deming writes:

"I think of poetry as a means to study nature, as is science. Not only do many poets find their subject matter and inspiration in the natural world, but the poem's enactment is itself a study of wildness, since art is the materialization of the inner life, the truly wild territory that evolution has given us to explore. Poetry is a means to create order and form in a field unified only by chaos; it is an act of resistance against the second law of thermodynamics that says, essentially, that everything in the universe is running out of steam. And if language is central to human evolution, as many theorists hold, what better medium could be found for studying our own interior jungle? Because the medium of poetry is language, no art (or science) can get closer to embodying the uniqueness of human consciousness. While neuroscientists studying human consciousness may feel hampered by their methodology because they can never separate the subject and object of their study, the poet works at representing both subject and object in a seamless whole and, therefore, writes a science of the mind.

"I find such speculation convincing, which is probably why I became a poet and not a scientist. I could never stop violating the most basic epistemological assumption of science: that we can understand the natural world better if we become objective. Jim Armstrong, writing in a recent issue of Orion, put his disagreement with this assumption and its moral implications more aggressively:

" 'Crudely put, a phenomenon that does not register on some instrument is not a scientific phenomenon. So if the modern corporation acts without reference to "soul," it does so guided by scientific principles -- maximizing the tangibles (profit, product, output) that it can measure, at the expense of the intangibles (beauty, spiritual connectedness, sense of place) that it cannot' ....

"Clearly a divide separates the disciplines of science and poetry. In many respects we cannot enter one another's territory. The divide is as real as a rift separating tectonic plates or a border separating nations. But a border is both a zone of exclusion and a zone of contact where we can exchange some aspects of our difference, and, like neighboring tribes who exchange seashells and obsidian, obtain something that is lacking in our own locality."

The subject of borders is especially relevant to creators of fantasy, for ours is a field that borders on others, and one that is often most fertile in those places where the edges meet. Border-crossing is thus part of a mythic artist's vocation, but it's not always a simple or comfortable one. As Sergio Trancoso once said:

"I am in between. Trying to write to be understood by those who matter to me, yet also trying to push my mind with ideas beyond the everyday. It is another borderland I inhabit. Not quite here nor there. On good days I feel I am a bridge. On bad days I just feel alone."

In the concluding pages of her essay, Deming returns to the place where art and science meet, the wild borderland between the two:

"In ecology the term 'edge effect' refers to a place where habitat is changing -- where a marsh turns into a pond or a forest turns into a field. These places tend to be rich in life forms and survival strategies. We are animals that create mental habitats, such as poetry and science, national and ethnic identities. Each of us lives in several places other than our geographic locale, several life communities, at once. Each of us feels both the abrasion and the enticement of the edges where we meet other habitats and see ourselves in counterpoint to what we have failed to see. What I am calling for is an ecology of culture in which we look for and foster our relatedness across disciplinary lines without forgetting our differences. Maybe if more of us could find ways to practice this kind of ecology we would feel a little less fragmented, a little less harried and uncertain about the efficacy of our respective trades, and a little more whole. And poets are, or at least wish they could be, as Robert Kelly has written, 'the last scientists of the Whole.' "

If poets are indeed "the last scientists of the Whole," I contend there are writers of fantasy and mythic artists standing right beside them.

Words: The passage above is from "Poetry and Science: A View from the Divide," published in The Edge of the Civilized World: A Journey in Nature and Culture by Alison Hawthorne Deming (Picador, 1998), which I highly recommend. The quote by Sergio Troncoso is from Crossing Borders: Personal Essays (Arte Publico Press, 2011). The Jim Carruth poem in the picture captions is from Envoi, #138, June 2004. All right reserved by the authors.

Pictures: A walk with husband, hound, and a herd of cows on the top of Meldon Hill.

The poet and the scientist

If, like me, you are a working artist striving to combine a love of nature with the creation of fantasy literature (or other forms of mythic art), it is sometimes a challenge to overcome the cultural divide between science and the arts -- in which knowledge of the flora, fauna, and biological processes that make up our world is deemed the domain of scientists, while artists working with the tropes of myth and fantasy are relegated to more ethereal realms.

When I need help crossing the barriers that convention (and my humanties-focused education) placed between the two, I turn to the increasingly-poetic field of contemporary nature writing for inspiration. The following passage, for example, is from "Poetry and Science: A View from the Divide," an excellent contemplation of the subject by American poet and essayist Alison Hawthorne Deming:

"Historically, cultures have been informed by places, by the natural features and resources available to people living in a specific geographic habitat. The 'globalization of culture' is the term in fashion for the phenomenon of everyone becoming more contiguous, contingent, more like us. We lament the dilution of local cultures in the floodwaters of global capitalism, feel a justifiable panic about the pace of this change, and wonder how we will know ourselves and others in the future if our nationalistic and ethnic identities melt away. It is not a contradiction that people by the droves are looking for their own cultural roots, castigating others for past cultural injustices, and documenting difference wherever they can find it, at a time when place-based culture is fading fast. We know something archetypal and precious is leaking from the world.

"But culture is not only place-based. Culture is also based on discipline, profession, affinity and taste, and in these forms has been around since the beginning of civilization. The problem with the future is that it is difficult to know what will happen there. But it seems likely that these non-place-based forms of culture will become increasingly important. Culture will become more and more our habitat, as cultural learning continues to supplant the poky genetic code. I'm not suggesting we relax our vigilance in protecting actual places and preserving the knowledge acquired by deeply place-based cultures, only that our motivation and ability to do these things may change -- may even improve -- as new cross-cultural affinities emerge. My affinities for literary writers and natural scientists probably say as much about who I am as the geographic fact that I am a tenth-generation New Englander, and nourish me in ways that make my best work possible. Cultural exchanges across disciplinary boundaries can be as fruitful as those across geographic ones. Unlike C.P. Snow, I do not see 'the intellectual life of the whole of western society being split into two polar groups,' literary intellectuals at one pole and scientists at another. I have always been struck, perhaps naively, by the fundamental similarity between the poet and the scientist: both are seeking a language for the unknown....

"The view from either side of the disciplinary divide seems to be that poetry and science are fundamentally opposed, if not hostile to one another. Scientists are seekers of facts; poets revelers in sensation. Scientists seek a clear, verifiable and elegant theory; contemporary poets, as critic Helen Vendler recently put it, create objects that are less and less like well-wrought urns, and more and more like misty collisions and diffusions that take place in a cloud chamber. The popular view demonizes us both, perhaps because we serve neither the god of profit-making nor the god of usefulness. Scientists are the cold-hearted dissectors of all that is beautiful; poets the lunatic heirs to pagan forces. We are made to embody the mythic split in Western civilization between the head and the heart. But none of this divided thinking rings true to my experience as a poet."

A little later in the essay, Deming notes:

"Today fewer Americans than ever believe scientists' warnings about global warming and diversity loss. Their scepticism stems, in part, from the fact that to a misleading extent the process of science does not get communicated in the media. What gets communicated is uncertainty, a necessary stage in solving complex problems, not synonymous with ignorance. But the discipline itself is called into question when a scientist tells the truth and says, in response to a journalist's prodding, 'Well, we just don't know the answer to that question.' ... What science-bashers fail to appreciate is that scientists, in their unflagging attraction to the unknown, love what they don't know. It guides and motivates their work; it keeps them up late at night; and it makes that work poetic. As Nobel Prize-winning poet Czeslaw Milosz has written, 'The incessant striving of the mind to embrace the world in the infinite variety of its forms with the help of art or science is, like the pursuit of any object of desire, erotic. Eros moves through both physicists and poets.' Both the evolutionary biologist and the poet participate in the inherent tendency of nature to give rise to pattern and form.

As a poet, Deming finds herself drawn to the precise language of science:

"...the beautiful particularity and musicality of the vocabulary, as well as the star-factory energy with which the discipline gives birth to neologisms. I am wooed by words such as 'hemolymph,' 'zeolite,' 'crytogram,' 'sclera,' 'xenotransplant' and 'endolithic,' and I long to save them from the tedious syntax in which most scientific writing imprisons them."

Likewise, science writers like Rachel Carson, Oliver Sacks, and Stephen Jay Gould demonstrate how researchers can use literary tools to describe scientific processes:

"...in particular, those aspects of the experience that will not fit within rigorous professional constraints -- for example, the personal story of what calls one to a particular kind of research, the boredom and false starts, the search for meaningful patterns within randomness and complexity, professional friendships and rivalries, the unrivaled joy of making a discovery, the necessity for metaphor and narrative in communicating a theory, and the applications and ethical ramifications of one's findings. Ethnobiologist and writer Gary Paul Nabhan, one of the most gifted of these disciplinary cross-thinkers, asserts that 'narrative and metaphor are more honest, precise and comprehensive ways of explaining an animal's life history than the standard technical format of hypothesis, materials, methods, results and discussion.'

"Much is to be gained when scientists raid the evocative techniques of literature, and when poets raid the language and mythology of scientists. "

The challenge for a poet, says Deming, is "not merely to pepper the lines with spicy words and facts, but to know enough science that the concepts and vocabulary become part of the fabric of one's mind, so that in the process of composition a metaphor or a paradigm from the domain of science is as likely to crop up as is one from literature or her own back yard."

And that, I believe, is the challenge for fantasists and mythic artists whose work is rooted in the natural world. The divide between art and science doesn't help us here. We, too, must breach the wall.

Words: The passage above, and the poem in the picture captions, is from "Poetry and Science: A View from the Divide," published in The Edge of the Civilized World: A Journey in Nature and Culture by Alison Hawthorne Deming (Picador, 1998), which I highly recommend. All rights reserved by the author.

Pictures: Our village nestles against two hills -- one behind my studio, where the hound and I walk most mornings, and the other, pictured here, rising high above the village Commons.

August 7, 2020

The language of whales

Marine biologist Eva Saulitis studied killer whales (or orca whales) in the coastal waters of Alaska for over thirty years, while also writing poetry and nonfiction blending nature writing and memoir. The following passage is from her first collection of essays, Leaving Resurrection:

"During my first summer out in Prince William Sound as a volunteer, one of my tasks was to decide on a project for my master's thesis. Initially, I felt drawn to the quieter ways of humpback whales, who stayed in protective areas near Whale Camp to feed. But small groups of killer whales kept passing by camp, hugging the shoreline. They were AT1 transients, mammal-eaters about which little was known except that they were mostly silent and difficult to follow....

"One day, my friend and I followed two AT1 transients from a small inflatable as they hunted harbor seals along an island shore. We lost them for several minutes, and then spotted silver mist above a rock. We let the boat drift near. Clinging tightly to the rock, its head craned back, eyes huge and black, a seal pup crouched above the water line. A transient nudged the rock, but couldn't reach the seal, at least not yet; the tide was rising. Abruptly, the whale turned, joined the second whale, and swam rapidly across an open passage. We left the lucky seal and raced to catch the transients, but they'd vanished. Cutting the outboard in mid-passage so we might hear their blows, we stood up, scanning with binoculars.

"I felt something through the bottom of my feet before I heard it. From the inflatable's wooden floorboards, a wail rose, and another, and another. My friend and I stared at each other.

"'It's the whales. They must be right under us. Let's drop the hydrophone,' I said.

"I scrambled for the tape recorder, and we huddled over the small speaker adjusting knobs as long, descending, siren-like cries reverberated against underwater island walls. In the distance, other whales answered, faintly. I'd never heard transients call before. It was like a stone had sung. I knew then. I wanted to learn the language of the whales that were mostly silent.

"In grad school, I learned the art of detachment, learned to watch how I said things, to listen for anthropomorphism, like applying the word language to non-humans. As scientists, we distinguish ourselves from whale huggers, lovers, groupies, and gurus, from those who think of whales as spiritual beings. We learn the evolutionary, biological basis for an animal's behavior. We study the various theories and counter-theories and debate their merits: reciprocal altruism, game theory, optimality theory, cost-benefit analysis.

"At scientific meetings, in animal behavior seminars, we don't debate whether animals have feelings. It's terra incognita. But on the research boat, or at the breakfast table, before the meeting begins, some of us talk about these things. One non-scientist friend, puzzled by the ways of science, asked, 'Isn't it strange to assume that humans are the only creatures with feelings, that we are so different from other animals?' Is it 'animapomorphic' to ascribe animal behaviors to humans? If it's wrong to suppose animals might share qualities with humans, then how do we see ourselves? Alone at the tip of some renegade branch of the tree of life?

"Out in the field, summer after summer, we search for knowledge, employing the scientific method: observation, hypothesis, data collection, analysis, discussion, conclusion. Poet and biologist Forrest Gander says that this method 'has endured as a scientific model, and a very successful one, for it predicts that when we do something, we will obtain certain results. But if we approach with a different model, we will ask different questions.' To create a new model: that prospect challenges all of the questions I've learned to ask -- and not to ask."

As the book goes on, Saulitis returns to this subject again and again. Is the language of science the only way, or even the best way, to understand the whales she is studying? What about the language of poetry, song, and story? What about the tales told about the whales by indigenous peoples whose lives have long been entwined with them?

In the book's final essay she reflects on local stories about the whales, such as this one:

"Very long ago, when someone died, the killer whales would come take them to a certain cove, dress them like killer whales, and release them into their new form. According to this story, the only difference between whales and humans is our skins. Zipping and unzipping this skin is like lifting up the cloth of the sea to go under, to effortlessly enter the killer whale realm. It seems magical, this lifting of cloth, this zipping on of skin. But it's much like the evolution story, in which killer whales shed body shapes to become what they've been now for five million years. Killer whales know some things about living here. Maybe we have to shed the skins we're wearing, find our way back into the weave, rejoin the ecosystem, put back on our animal skins....

"A woman from Dolovan, near Nome, told me of a time that killer whales helped her people to find food. When she was a baby, her family was moved from Elim to Dolovan. Some people went overland. Her grandmother and others went by rowboat around Cape Darby, in the Bering Sea. She herself was in the boat, wrapped in a rabbit-skin parka. The people were hungry and cold, so someone called to the killer whales and asked them for food. The next day, big pieces of muktuk washed up on the beach. The people ate it raw, they were so hungry, and the oil stained their clothes, which had to be burned.

" 'You never play with or harm or hunt or harass a killer whale,' she said, 'because they are so close to people.' She told me that a woman in Dolovan married a white man who didn't know all of the traditional rituals or rules, and one day he shot a baby killer whale. 'A person who harms a killer whale will die,' she said. An adult killer whale showed up and started swimming through the bay back and forth. The white man finally confessed to his wife what he'd done. She blamed herself for failing to teach him properly, so she went to a point far out in the water and apologized to the killer whale, saying that her husband didn't know, that it was her fault. The whale eventually forgave them and left.

"Inupiaq people say that killer whales drove seals onto the ice for hunters to catch. Tobacco was thrown into the whales' open mouths, in thanks. Those stories from many places in coastal Alaska, of killer whales opened mouthed, lips pulled back, revealing their teeth to hunters in boats, remind me of Matushka. We first saw her in Prince William Sound in 1987 with some of her relatives on my first day volunteering on a research project with Craig. While some of the whales swam rapidly around us, Matushka breached and tail-slapped repeatedly within a few meters of the skiff, dousing us with water. I was twenty-three and naive, didn't know this wasn't ordinary killer whale behavior, so I screamed and jumped around and tried to touch her. Finally, I looked at Craig, salt water dripping from his beard, and saw his unease. It was weird, he said, for transients to interact with a boat this way. We couldn't even take identification photos for fear of ruining the camera, but more so, because the whales were too close. We finally had to back away from them, but they charged after.

"That was my initiation into killer whale research, and I see it now as both a welcoming and a warning, a warning that my stories would have to change. My imagination would have to expand to include Matushka as she glided along the hull of the boat, her mouth wide open, showing me her teeth. I would have to look into my own animal nature.

"It's not impossible to imagine killer whales and humans having once spoken the same language, interchanged body forms. We are still dependent on each other, and the stories tell us that we must act that way, unless we want killer whales to exist only as mythical creatures, like the thunderbird, who, in one story, did battle with a killer whale, driving it into the sea, where it's lived to this day. Our big, imaginative brains define us. Deprived of the creatures who inspire our stories, will we be human? Or will we be proto-something else?

"Just as language shapes our thoughts, the way we tell stories shapes the way we see, and the way we see -- what we look at, the amount of time we spend on the water, in the woods -- shapes our imaginations. Jurgen Kremer asks, 'What if we have established a big thought system at the foundation of which is one giant rationalization? What if we need to turn things upside-down?' Is that the difference between knowledge and wisdom? Is wisdom knowledge turned upside-down?

"I write poetry these days, a craft that encourages the holding of opposing truths in the mind at the same time. While my logical mind grapples to reconcile the Tlingit story of the origin of the killer whale with the paleontological story, in my other mind, they coexist. Both are essential."

Eva Saulitis died of breast cancer four years ago, at the age of 52. She wrote about her illness as she wrote about her whales: with the clear observations of a scientist and the emotional depth and language of a poet. (For example, see her gorgeous piece on nature and dying, "Wild Darkness," in Orion magazine.)

I highly recommend Leaving Resurrection: Chronicles of a Whale Scientist; Into Great Silence: A Memoir of Discover and Loss Among Vanishing Orcas; and her last essay collection, Becoming Earth -- as well as her poetry, published in Many Ways to Say It and Prayer in the Wind.

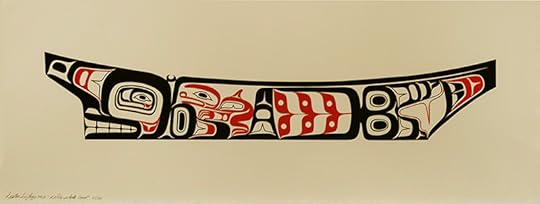

The imagery today is by Preston Singletary, a Tlingit artist based in Seattle who primarily works glass. His creations often feature killer whales because of the whale's significance as one of the crests of his clan.

"When I began working with glass," he says, "I had no idea that I'd be so connected to the material in the way that I am. It was only when I began to experiment with using designs from my Tlingit cultural heritage that my work began to take on a new purpose and direction. Over time, my skill with the material of glass and traditional form line design has strengthened and evolved, allowing me to explore more fully my own relationship to both my culture and chosen medium. This evolution, and subsequent commercial success, has positioned me as an influence on contemporary indigenous art. Through teaching and collaborating in glass with other Native American, Maori, Hawaiian, and Australian Aboriginal artists, I've come to see that glass brings another dimension to indigenous art. The artistic perspective of indigenous people reflects a unique and vital visual language which has connections to the ancient codes and symbols of the land. My work with glass transforms the notion that Native artists are only best when traditional materials are used. It has helped advocate on the behalf of all indigenous people -- affirming that we are still here -- that that we are declaring who we are through our art in connection to

our culture."

To see more of Singletary's beautiful, deeply spirited work, go here.

Words: The passages quoted above are from Leaving Resurrection by Eva Saulitis (Boreal Books, 2008); all rights reserved by the author's estate. The Jurgen Kremer quote is from Indigenous Science: Introduction (ReVision 18, no, 3, Winter 1996).

Pictures: The art above is by Preston Singletary; all rights reserved by the artist. The name of each piece is identified in the picture captions. (Run your cursor over the images to see them.)

August 6, 2020

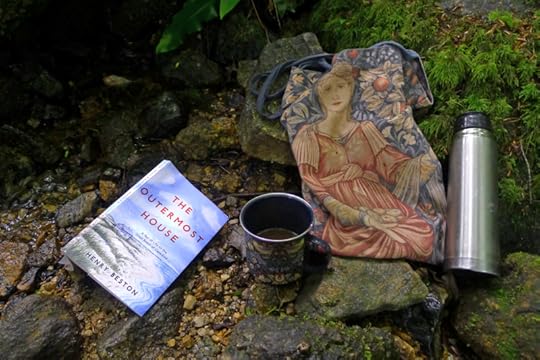

The Outermost House

In previous posts we've been discussing the oceans and islands of Ireland and Scotland, but there is a wealth of good writing about the sea from North America too -- such as The Outermost House by Henry Beston, first published in 1928.

Beston was born to a French and Irish family in Quincy, Massachusetts in 1888; he attended Harvard, and served in World War I as an ambulance driver (for the French army) and war correspondent (for the US Navy). Upon returning home, he worked as a magazine editor while also writing two books of fairy tales (The Firelight Fairy Book and The Starlight Wonder Book), and finding solace for wartime trauma through a love of birds and the natural world. In the 1920s, he built a tiny house on an isolated stretch of Cape Cod beach, then spent a year living alone there, observing the sea through four full seasons. He writes:

"My house stood by itself atop a dune, a little less than halfway south on Eastham bar. I drew the homemade plans for it myself and it was built for me by a neighbor and his carpenters. When I began to build, I had no notion whatever of using the house as a dwelling place. I simply wanted a place to come to in summer, one cozy enough to be visited in winter could I manage to get down. I called it the Fo'castle. It consisted of two rooms, a bedroom and a kitchen-living room, and its dimensions over all were but twenty feet by sixteen. A brick fireplace with its back to the wall between rooms heated up the larger space and took the chill off the bedroom, and I used a two-burner oil stove when cooking.

"My neighbor built well. The house, even as I hoped, proved compact and strong, and it was easy to run and easy to heat. The larger room was sheathed, and I painted the wainscoting and the window frames a kind of buff-fawn -- a good fo'castle color. The house showed, perhaps, an amateur enthusiasm for windows. I had ten. In my larger room I had seven; a pair to the east opening on the sea, a pair to the west commanding the marshes, a pair to the south, and a small 'look-see' in the door. Seven windows in one room perched on a hill of sand under and ocean sun -- the words suggest cross-light and glare; a fair misgiving, and one I countered by use of wooden shutters, originally meant for winter service but found necessary through the year. By arranging these I found I could have either the most sheltered and darkened of rooms or something rather like an inside out-of-doors. In my bedroom I had three windows -- one east, one west, and one north to the Nauset light....

"I had two oil lamps and various bottle candlesticks to read by, and a fireplace crammed maw-full of driftwood to keep me warm. I have no doubt that the fireplace heating arrangement sounds demented, but it worked, and my fire was more than a source of heat -- it was an elemental presence, a household god, and friend."

Beston began his year of solitude on the dunes almost by accident:

"My house completed, and tried and not found wanting by a first Cape Cod year, I went there to spend a fortnight in September. The fortnight ending, I lingered on, and as the year lengthened into autumn, the beauty and mystery of this earth and outer sea so possessed and held me that I could not go.

"The world is sick to its thin blood for lack of elemental things, for fire before the hands, for water welling from the earth, for air, for the dear earth itself underfoot. In my world of beach and dune these elemental presences lived and had their being, and under their arch there moved an incomparable pageant of nature and the year. The flux and reflux of the ocean, the incomings of waves, the gatherings of the birds, the pilgrimages of the peoples of the sea, winter and storm, the spendour of autumn and the holiness of spring -- all these were part of the great beach. The longer I stayed, the more eager I was to know this coast and to share its mysterious and elemental life; I found myself free to do so, I had no fear of living alone, I had something of a field naturalist's inclination; presently I made up my mind to remain and try living for a year on EasthamBeach."

I highly recommend this quietly beautiful, influential book, by an author now recognized as a pioneer of American nature writing.

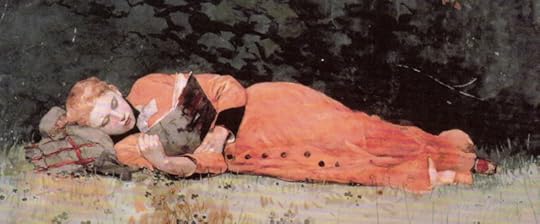

The art today is by American painter and printmaker Winslow Homer (1836-1910). Born (like Beston) in Massachusetts, Homer began his career as self-taught illustrator for newspapers and magazines, including a stint as a war artist on the front lines of the American Civil War for Harper's Weekly. After studying oil painting in New York and France, he gave up illustration to focus on landscape painting full time. Retreating from urban life from the 1870s onward, Homer lived a series of fishing villages in New England and northern England, finally settling on the coast of Maine, while also travelling extensively to paint and fish in Key West, Cuba, the Carribean, and the Adirondack Mountains. To see more of his work go here.

August 5, 2020

One last selkie tale

From "The Selkie Wife's Daughter" by Jeannine Hall Gailey:

I always wondered why she sang so strangely

at the spinning wheel, why her eyes held all

the mourning of the darkest sea. And why

she held me away,

as if afraid of my skin, why my feet and

hands were webbed with translucent sea���skin.

I used to bring her armfuls of yellow

water iris to almost

see her smile. I wondered why father

never let me swim out against the waves,

never let her walk the shores alone....

To read the full poem, go here.

Words: The poem extract above, inspired selkie legends is from Becoming the Villainess by Jeannine Hall Gailey (Steel Toe Books, 2006), which I highly recommend. All rights reserved by the author. Pictures: The photographs above are by Dan Kitwood, Steve Race, Elmar Weiss, and Friends of Horsey Seals (Norfolk). All rights reserved by the photographers.

August 4, 2020

Another selkie tale

From "A Taste of the Sea" by essayist & novelist Scott Russell Sanders:

"A selkie takes a great risk in changing from a seal to a man, for he may not be able to change back again. No matter how carefully he hides his pelt, someone may find it. A child playing along the shore may take it for a plaything, a beachcomber may take it for a rug, a fisherman may sell it to the fur dealer, a woman intent on keeping him in her arms may lock it in a chest. Without that pelt, a selkie cannot return to the sea. Nor can he return if he has fallen in love with the woman who called him ashore to father her child.

"It is said that male selkies are the seducers, charming female humans with our fathomless dark eyes and our muscles sculpted from swimming. Although that may be true for others, it is not so for me. I did not choose to shed my skin and walk on two legs away from the ocean, any more than salmon choose to abandon saltwater for spawning and death in their native streams. I was summoned from the water by a maiden who wept seven tears into the cove where I floated, asleep and dreaming....

To read the rest of Sanders' short, evocative story, please go here. His new collection, The Way of the Imagination, is coming out this month from Counterpoint Press.

Other recent selkie posts: The accomodation of paradox, Following the seals, and A selkie tale.

Words: The text quoted above is from "A Taste of the Sea" by Scott Russell Sanders (Orion Magazine, May 19, 2020); the poem in the picture captions is "The Fisherman's Farevwell" by Scottish poet Robin Robertson (Poetry, January 2013); all rights reserved by the authors. Pictures: The photographs above are by Dan Kitwood, Jason Neilus, Dmitry Starorstenov, and Peter Verhoog; all rights reserved by the photographers.

August 3, 2020

Tunes for a Monday Morning

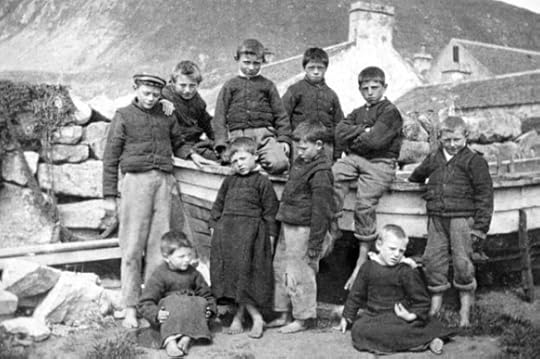

The music today is from an extraordinary musical project: The Lost Songs of St Kilda.

The islands of St Kilda, at the westernmost edge of the Scottish Hebrides, were continuously inhabited for over two millenia until its last residents were officially evacuated in 1930. As Patrick Barkham writes in The Islander:

"St Kilda is the most famous island -- or islands -- in Britain. Hiort, as it is known in Gaelic, is an archipelago containing Hirta (in Gaelic, Hirte), Borerary (Boraraigh), Soay (S��thaigh) and D��n. It is the most peripheral of British isles, fifty miles west of the Outer Hebrides, a hundred miles from the Scottish mainland. Plenty of islands lost their people in the early 1900s, particularly the smaller islands of the Outer Hebrides -- Berneray, Mingulay, Sandray, Taransay, Scarp and Boreray -- but St Kilda has become the generic example of small-island extinction. A pinprick on any map, alone in the Atlantic, it is much more prominent in many mental cartographies, an object of obsession and longing -- 'as much a place of the imaginationas a physical reality', as Madeleine Bunting says in her tour of the Hebrides. St Kilda is Britain's only dual World Heritage site, protected for both its nature and its culture; and archaeologists, geologists, ecologists and historical anthropologists have poured over it, subjecting it to more than seven hundred books and scholarly articles. Its story is told and retold, polished and revised, mostly by outsiders like me, who wonder: Were the Hiortaich unique, or rather like us? And why, after so many generations of habitation, did they abandon the home they loved?"

Why, indeed. That's a question journalists and scholars have been asking since the evacuation, with complex and contradictory answers.

The Lost Songs of St Kilda is a collection of traditional tunes from the islands -- all of which would have been lost forever were it not for Trevor Morrison, who had learned them from his piano teacher, a St Kilda evacuee. Morrison made a home-recording of the songs, and after his death, in 2012, the recording eventually found its way to the offices of Decca Records. Decca then asked Sir James Macmillan and other Scottish composers to develop the St Kildan tunes, aided by the Scottish Festival Orchestral and additional musicians (including Julie Fowlis, from North Uist). The result is this very beautiful album: a tribute to a lost musical tradition and a vanished way of life.

Above, a short video about the project.

Below, the returning of the Lost Songs, after all these years, to the place where they were born.

Above, "Soay," a tune named after one of the smaller islands of St Kilda. The name is derived from Sey��oy, meaning the Island of the Sheep in Old Norse. The piece is performed by composer Sir James Macmillan on Hirta, the largest of the islands. (If you live in an area where this video won't play, you can access an audio-only version of the song here.)

Below, "Hirta," with film footage from the 1920s, and contemporary photographs. There are several theories about the orgins of the island's name, including its possible derivation from Hirt, the Norse word for shepherd, or from h-Iar-T��r, a Scots Gaelic word meaning "westland." (An audio-only version of the song is here.)

To learn more about the Lost Songs project, go here.

I also recommend Hirta Songs (2014), a fine album of music by Aladsair Roberts and poetry by Robin Robertson. The piece below is "The Leaving of St Kilda."

And one more recommendation: Night Waking (2011), a novel by Sarah Moss that was partially inspired by St. Kilda's history. The story takes place on a fictional Scottish island, split between contemporary and Victorian narratives: darkly comic and mysterious by turns. It's the first in a sequence of interconnected novels, followed by Bodies of Light (set in Victorian Manchester and London) and Signs for Lost Children (set in Cornwall and Japan). I personally think Moss is one of the best writers working in Britain today.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 710 followers