Terri Windling's Blog, page 28

September 8, 2020

We are storytelling animals

"For me, the literature of the fantastic began with storytelling. After all, humans are storytelling animals. Only we now do most of our storytelling on the page. I am obsessed with stories -- my own and other people's. I want my music and art to tell stories as well. What happened next? is probably the first sentence I ever spoke. And even if it isn't, I can certainly pretend it is since both of my parents are no longer around to contradict me.

"Everyone in the family was a storyteller. Some people called them liars. But the Yolen gene is a storytelling gene. And so it goes. My daughter writes, one son is a musician whose songs tells stories, the other a photographer who captures stories in his lens. When I die, I want my tombstone to read: She wrote many good books and one great one. I will let the readers of that argue over which book I mean. That will force them to read the stories -- and tell their own."

"My family finds me a nuisance when I'm writing a book. It isn't just that I get absent-minded and forget meals. I laugh. In the early days, when I was writing The Ogre  Downstairs, I sat by myself and laughed so much that my children kept coming and asking if I was alright. Later, they got used to it and simply tested me to make sure I'd heard what they said. I became very good at replaying a conversation I hadn't actually known I'd had.

Downstairs, I sat by myself and laughed so much that my children kept coming and asking if I was alright. Later, they got used to it and simply tested me to make sure I'd heard what they said. I became very good at replaying a conversation I hadn't actually known I'd had.

"Now, when the children have long ago grown up, my husband still gets astonished when I laugh as I write. When I was writing Howl's Moving Castle and nearly fell off the sofa in my mirth, he said, 'You can't be making yourself laugh!' I said, 'No, it's this book that's making me laugh.' That is because, when a book is going as it should, it doesn't feel as if I'm doing it. It takes its own way, and people in it do things I don't expect. This is true however a book comes to me. Charmed Life arrived in my head almost as a complete book, but it was still unexpected. With Archer's Goon, on the other hand, I had almost no idea what was going to happen from one page to the next -- which made it very unexpected.

"But I don't always laugh. Some books, like the Dalemark Quartet, have kept me on the edge of my seat, barely able to breathe. Others, like Fire and Hemlock and Dogsbody, have wrung my heart as I wrote them and taught me things I never thought I knew about people and their feelings.

"I learn things as I write, you see. This is why I enjoy it so much."

"If I wanted to know where my ideas came from I wouldn't be an imaginative writer, I'd be a scientist. My whole life has been spent daydreaming and out of those ideas and daydreams come stories. It doesn't interest me where daydreams come from, what interests me is helping them grow and blossom into something different, some strange and wonderful tale of mystery and magic. Then again, if you ask a few scientists where they got their ideas from they might tell you they spent most of their life daydreaming and out of those daydreams came something different, some strange and wonderful discovery or invention."

"There were always tales passed from mother to daughter, father to son. Down through the generations they came, so that we would never forget that place, that magic, that elemental and awesome power that abided in our forbears. In each generation the power of the tales rests with us, the storytellers. I weep, I cry with joy, I exult in the God-power of the words.

"And so I have tried to pass them on to another generation, to keep alive the mortal power of our earlier selves, even as the world changes and dies, sleeps and awakes anew to the force that gives life to our souls. So that some child can hear the tales and find them awakened in herself to pass on to yet another generation. "

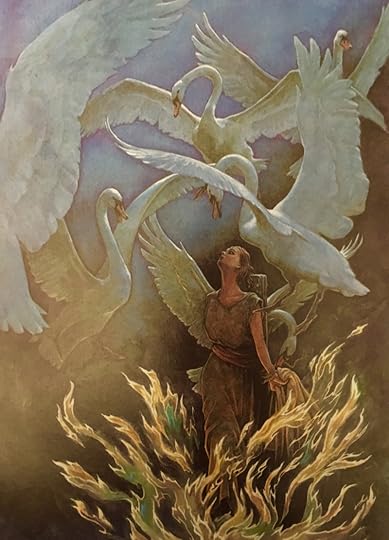

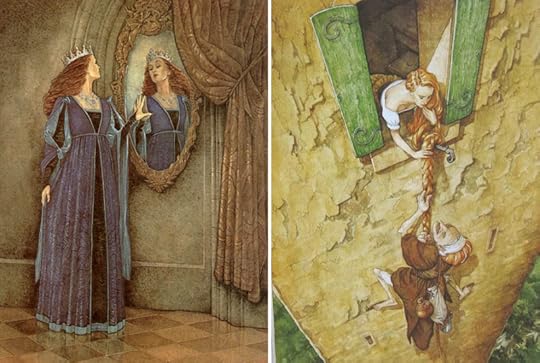

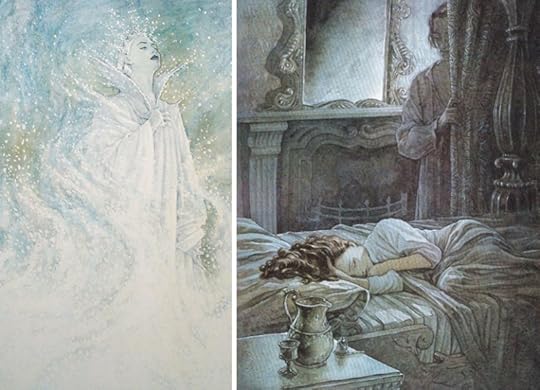

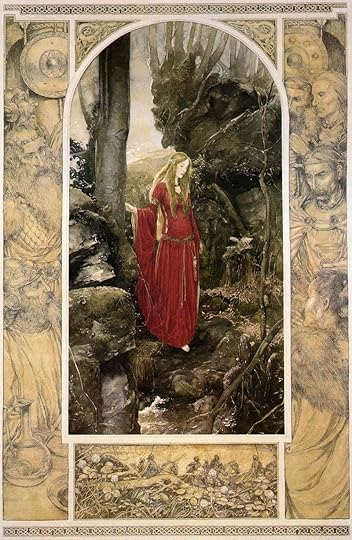

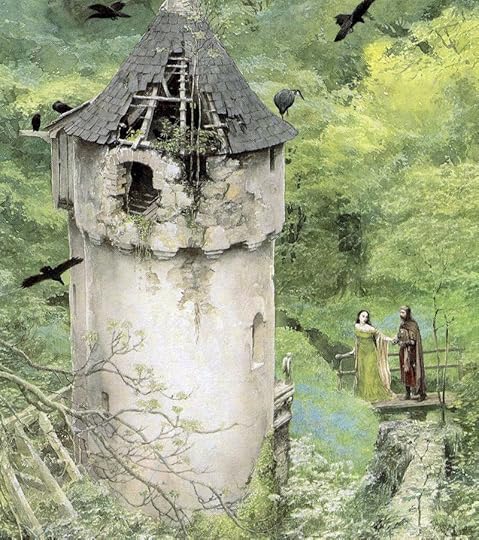

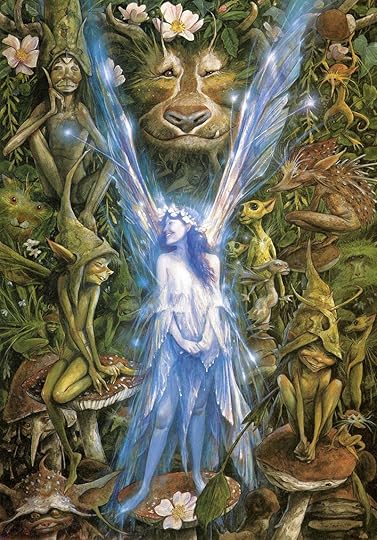

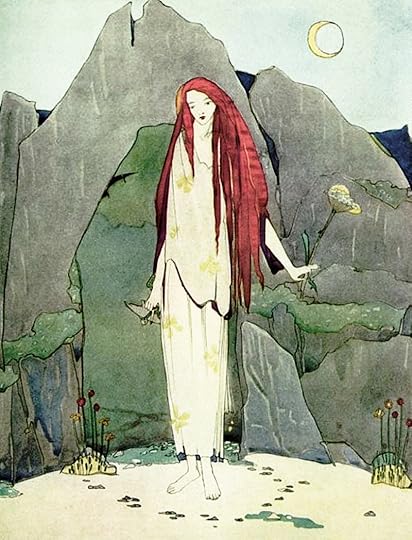

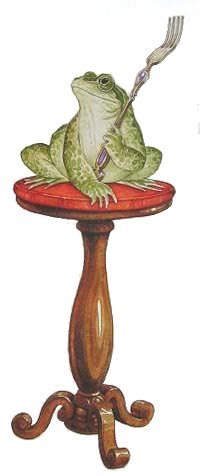

The paintings here are by Irish book artist P.J. Lynch. Born and raised in Belfast, he used drawing and reading, he says, "as a way of escaping from the horrors that were happening around me in the real world." After studying at the Brighton College of Art, he became an illustrator in 1984 -- going on to win two Kate Greenaway Medals for excellence in children's illustration. His many books include Fairy Tales of Ireland, East of the Sun and West of the Moon, The Candlewick Book of Fairy Tales, The Snow Queen, Catkin, The King of Ireland's Son, The Bee-Man of Orn, A Christmas Carol, and The Gift of the Magi.

"My first book, A Bag Of Moonshine by Alan Garner, was probably the thing that decided my career," he recalls. "I was lucky enough to win the Mother Goose Award for my illustration work on that book. That led to other book commissions and I���m still at it thirty years later. Maybe if I hadn���t won that prize I might have specialised in a different type of painting, but I am very glad that I did. I can���t think of a nicer career than making illustrated books."

To see more his enchanting work, please visit his website and blog.

All rights to art and text above reserved by the artist and the authors or their estates.

September 7, 2020

Tunes for a Monday Morning

Here in Devon, apples cluster on mossy old trees and blackberries are ripening as the summer eases into autumn. The morning air is crisp with change ... yet the pandemic goes drearily on and on. With each new season we learn new ways to live with it, but it takes a heavy toll.

Working from an isolated cabin by the woods, my daily routines (long hours of solitary desk work, broken by rambles through the hills with Tilly) have changed less than most. But Chagford, our village, is a sociable place, and it is very strange to have gone so long without meeting up with friends and neighbours for meals, music, community events, shared celebrations. The summer went by in the blink of an eye and seems to have barely happened at all. The Dartmoor countryside was as beautiful as always, the air even clearer, the birdsong more vivid ... but without friends gathered at an outdoor table, or sprawled around a picnic blanket, or playing music by a campfire while the kids and dogs tumble through the tall grass, it didn't actually feel like summer. I usually love the turning of the seaon, but this year it is tinged with melachology for all we've missed.

In honour of convivial summers past, and in the hope that there will be many more to come, I'm starting the week with songs of feasts and friendships, and of weathering hard times together....

Above: "Rang Tang Ring Toon" by Moutain Man, an American vocal harmony trio (Molly Erin Sarle, Alexandra Sauser-Monnig, and Amelia Randall Meath) from the mountains of Vermont. The song appeared on their second album, Magic Ship (2018).

Below: "Nest" by Ruth Moody, from Winnipeg, Canada -- best known as a member of the Wailin' Jennys trio. The song appeared on her first solo album, The Garden (2010).

Above: "Stand Like an Oak," a new single fom Rising Appalachia (sisters Leah and Chloe Smith), who divide their time between Georgia and New Orleans. Their most recent album is Leylines (2019).

Below: "Old Pine," by Ben Howard, who hails from the other side of the moor. This one, set on the Devon/Cornwall coast, is an old favourite of mine from Ben's first album, Every Kingdom (2011).

Above: "Old Ties and Companions" by Mandolin Orange (Andrew Marlin and Emily Frantz), from North Carolina. The song appeared on their fourth album, Such Jubilee (2015).

Below: An ode to the "Company of Friends" by Carrie Elkin and Danny Schmidt, from Austin, Texas. The song appeared on Elkin's solo album For Keeps (2012).

But let's not end on that somber note.

Below, "Typhoon" by Laura Cortese and the Dance Cards reminds us that after the wreckage of life's storms there's a time for building up again, preferably surrounded by our friends. The song is from their new album, Bitter Better (July 2020).

Top photograph: Preparing for a gathering of friends in my mother-in-law's garden here in Chagford, pre-pandemic.

Bottom photograph: Feasting with a group of women friends: Wendy Froud, me, Carol Amos, Elizabeth-Jane Baldry, Marja Lee and Hazel Brown (holding the camera), in Elizabeth-Jane's cottage kitchen. We'd been meeting monthly like this for over 25 years until the pandemic struck. I long for the day when we'll meet so freely again. I know it will come.

September 3, 2020

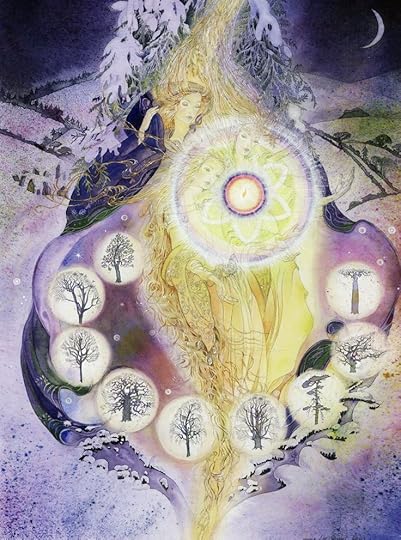

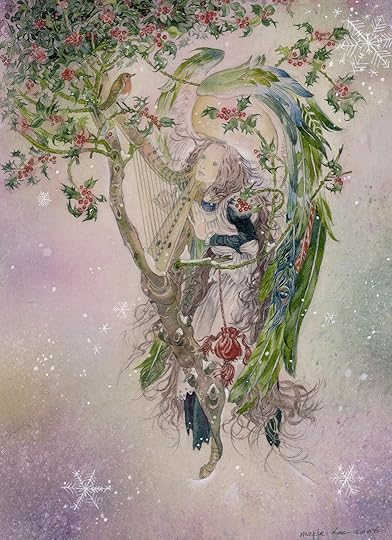

The Visionary Art of Marja Lee Kru��t

Marja Lee Kru��t was born and raised in the Netherlands in the province of Drenthe: a beautiful, dolmen-studded region in the northeast of the country, near the German border. She spent five years studying fashion illustration design in Amsterdam, and at the age of twenty she embarked on a professional career as a fashion illustrator. In 1964, Marja moved to London, where she created fashion drawings for major stores in England and abroad, as well as for newspapers and magazines such as Vogue and Harper's Bazaar. She was also involved in the ballet ��� both as a dancer and as a costumer for various productions -- and she made clothes for a Plimlico boutique that catered to the likes of Marianne Faithful, Mick Jagger, Pete Townsend, and Brian Jones. (Faithful was often photographed during those years in a cape Marja designed for her.)

While she was living in London, in a flat above Quentin Crisp's, Marja met her future husband, Alan Lee, a talented book illustrator. In 1975, the couple moved to a rural village at the edge of Dartmoor, sharing a house with their friend and fellow-artist, Brian Froud.

While she was living in London, in a flat above Quentin Crisp's, Marja met her future husband, Alan Lee, a talented book illustrator. In 1975, the couple moved to a rural village at the edge of Dartmoor, sharing a house with their friend and fellow-artist, Brian Froud.

Brian Sanders described the house in 1977 (in the book The Land of Froud): "From the outside the house is a modest Victorian cottage set back from the street in a tangled garden. From the moment that one crosses the threshold, guarded by a moss and lichen jewelled hand pointing skywards, from amid a welter of muddy wellington boots, a different land begins. Two families, the Lees and the Frouds, live here: the real Lee children side-by-side with Brian's family, the Troll King, his brother, and their mother. The mother has a hand in her back, and when Brian holds her they become one. The puppet fits to him and there is a deep affection between them: Brian the wizard surrounded by his animate creations, discussing them with a child who believes in them as much as he does. Walls, shelves and floors are crowded with books, toys, found objects and constructions. Ghosts, faeries and pictures of goblins abound." (It was during these years that Alan and Brian produced their now-classic art book, Faeries.)

Meanwhile, Marja continued to pursue her London-based illustration career until her children were born, but afterwards (like so many other women artists of her generation) her fashion work was set aside while she raised her children, and provided admin support for her husband's busy career. Yet even during those years focused on running a household, her creative powers did not lie dormant. She created costumes for local theatrical productions, and for figures sculpted by doll-artist Wendy Froud; she drew portraits, designed hats and clothes, and studied the Celtic harp...all while excelling in the area Grace Nuth has dubbed domythic art: bringing myth, magic, and romantism into every aspect of domestic life.

In 1998, her children grown, a new chapter in her life began when Marja returned to the studio. The work she produced was astonishing: drawings and paintings with a rich maturity of vision that had been quietly brewing over all those years, emerging like dreams, straight from the subconscious, each one a treasure of mythic art.

"I've always been interested in dreams," she says. "And in myth, mysticism, and symbolism. Through the use of color, of line, of the symbolic nature of garments, objects, patterns, and flowers, I attempt to create pictures that work on many different levels: marrying our everyday reality with other planes of dream and intuition. Painting, to me, is soul work, healing work. It's a kind of meditation."

Her painting practice is a spiritual one, craft and technique in service to spiritual intent.

"I begin each picture with a ceremony," she explains, "opening myself to the picture's theme and asking to be given the symbols with which to represent that theme. It's important to stay wide open as I work, to let the images come through me, unforced, shapes and colors emerging intuitively. It's a slow, deep, painstaking process, and a single picture can take me several months -- working out the composition and colors by doing many drawings and watercolor sketches first. Each part of the picture must be right; each element has an individual meaning, yet must also be woven into the rest of the design. I often use Celtic patterns, for instance, which represent the way things weave together in life -- and the way that our lives in the here-and-now are woven with other dimensions of consciousness.

"Flowers, animals, stones -- all these pictorial elements must work as part of the painting's composition, but have symbolic meanings as well. The specific flow and movement of a garment, for instance, can represent different aspects of spiritual awareness. I draw upon Celtic symbols...Eastern symbols...Steiner colour theory...Perelandra essences...mandalas...whatever the picture calls for. Watercolor is a fluid medium and I strive to work with, not against, the flow. That may sound airy-fairy but it's not, really; watercolor is a medium that requires technical precision too. In art, as in life, we must be grounded and free-flowing, intuitive, all at once. I suppose making pictures in this way, like any spiritual practice, is really all about balance."

"My background in fashion illustration is probably evident in my paintings, as well as my love of music and harps. I also like painting children, representing that childlike part within each of us. And fairies. Living here on Dartmoor, fairies were bound to turn up in my pictures!

"I have always loved the Victorian 'fairy painters' and book illustrators, such as Arthur Rackham and Edmund Dulac, as well as the Pre-Raphaelites: William Morris, Burne-Jones, Rossetti. But the artists who have influenced me the most are Gustav Klimt, Sulamith W��lfing, and the Renaissance painters Sandro Botticelli and Benezzo Gozzoli -- particularly the angels. W��lfing's influence is probably the most apparent. I feel an affinity with her. She drew angels even as a little girl, often talking about her angels and guides, and was influenced by Krishnamurti, the White Brotherhood, and the Theosophical Society. She was a mystic, really, and expressed her mysticism through her art. There are things that we can portray through pictures and symbols that we can't convey as easily through words. Art can speak directly to the soul. W��lfing's best pictures do this -- as do some of the great religious pictures from the Renaissance.

"I think art can be healing, moving, enlightening. It can also be puzzling, disturbing, or even upsetting...and sometimes that is necessary. It wakes you up. When you live with a picture, when you keep looking at it and taking it into yourself over a period of time, it can change you: moving you from one way of thinking to another, from one level of consciousness to the next. I like pictures that make you keep on looking, that reveal themselves and their meanings slowly. Art that keeps on giving you more, and a little more, every time you look."

Marja works from an exquisite painting studio at the back of a "secret garden," tucked away at the end of a path behind the old stone building where she lives. It is from here she does her "soul work," weaving painting and spiritual practices into a life lived on many levels at once. She creates magic on each one of those levels, and trails beauty behind wherever she goes.

Photograph: Marja Lee Kru��t & Brian Froud in front of Marja's art at the Whiddershins Mythic Art exhibition, 2016. For further information on the folklore of the harp, go here.

The paintings and drawings above are under copright by Marja Lee Kruyt, and may not be reproduced without her permission; all rights are reserved by the artist. The title of each artwork can be found in the picture captions. (Run your cursor over the images to see them.) The Brian Sanders quote is from The Land of Froud (Peacock Press/Bantam Books, 1977).

September 2, 2020

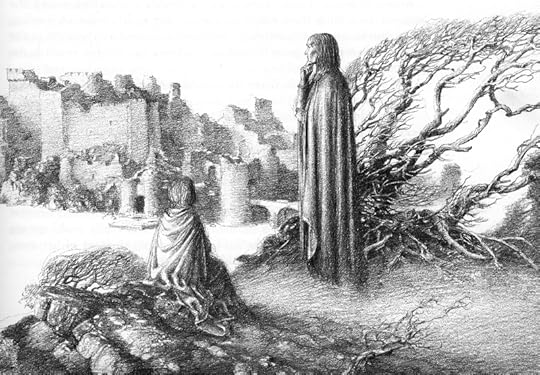

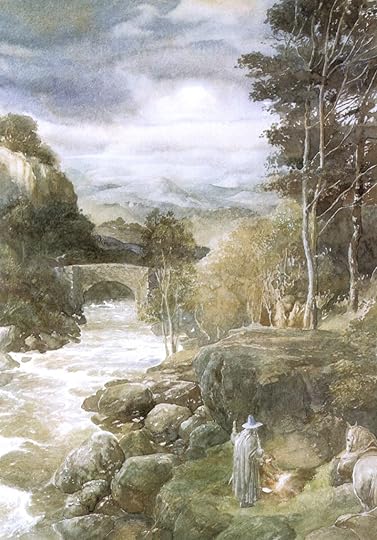

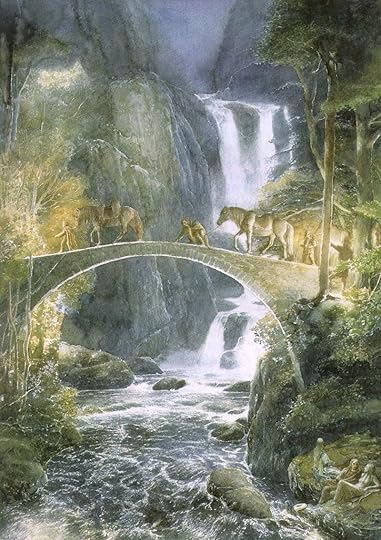

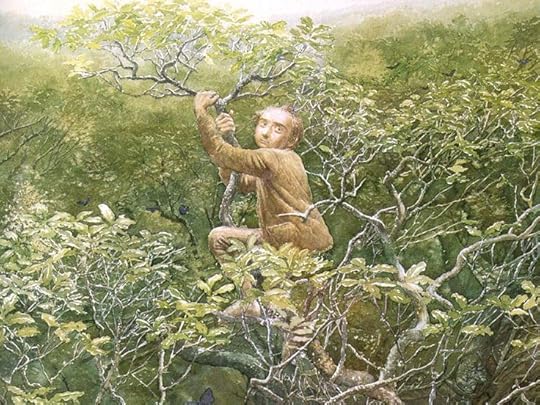

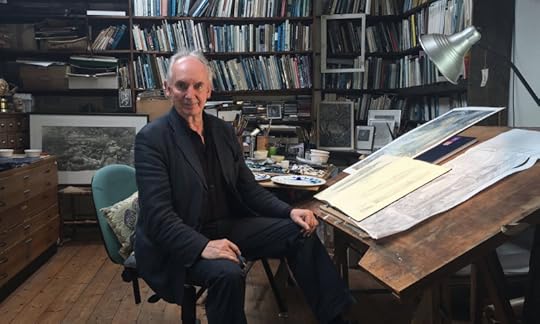

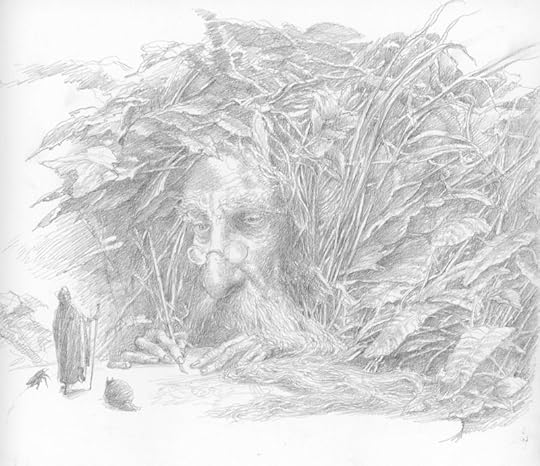

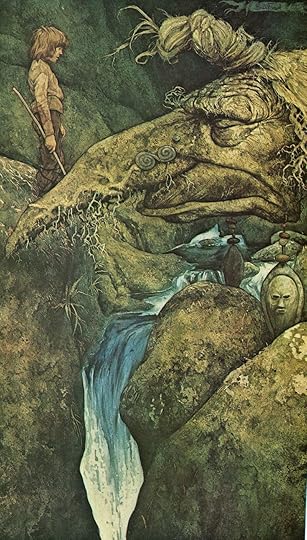

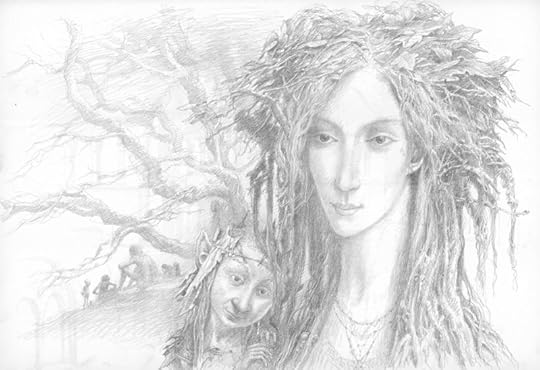

The Mythic Art of Alan Lee

"I have a very clear memory of my first encounter with myth," Alan Lee recalls, "sitting in a mobile library and travelling, at the same time, with Theseus on the road to Athens. By the time we'd met and disposed of the pine-bending giant Sinis, I'd become completely entranced. Within a few months I'd read every book on myths, legends, and folklore in our two nearest libraries."

The young boy entranced by ancient tales never lost his taste for magic and myth, and grew up to become one of the finest book illustrators of our time. His distinctively elegant watercolor paintings -- adorning Greek myths, Arthurian legends, Tolkien's Lord of the Rings, and other magical tales -- have earned him a world-wide following, the prestigious Kate Greenaway Award, museum and gallery exhibitions around the globe, and the deep respect of fellow artists and writers in the publishing field. Like Arthur Rackham or Edmund Dulac from Britain's Golden Age of illustration, Alan's work imbues imaginary landscapes with such startling reality one can almost step inside the paintings to travel beyond the visible horizon. Walking into his Devon studio, filled to the brim with paintings and books, is to cross a portal into the Otherworld of a master artist's vision, a place where stories come to life in pencil strokes and washes of color.

Alan was born in Middlesex in 1947, and decided at a young age that art would be his life's vocation. After training at Ealing School of Art he became a freelance illustrator, working in the fields of book publishing, advertising, and film. During these early years, his London work space was shared with a number of other artists -- including Brian Froud, a painter also drawn to myths and legends. These two friends teamed up to create Faeries, a book exploring the rich tradition of faery lore in the British isles, reaching past the modern image of the creatures (sweet little sprites with butterfly wings) to capture the faeries of the old oral tales: earthy, wild, mysterious, and capricious as a force of nature. Published in 1978, this ground-breaking book became an international bestseller, and an influential text for a whole generation of artists, writers, and film-makers to come.

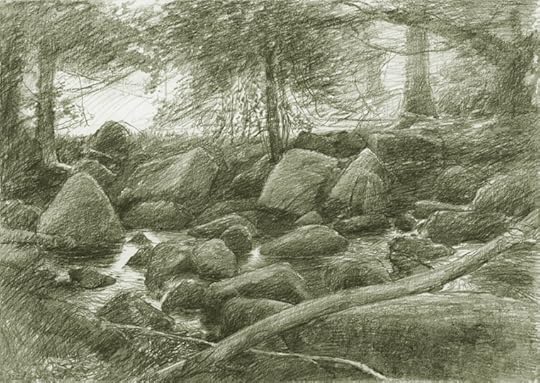

Just prior to the creation of Faeries, Alan, his family, and Brian moved from London to rural Devon, settling in a small village at the edge of Dartmoor. The mossy woods, wild hedgerows, and mythic grandeur of the moor had a strong effect on Alan's work: he is, in truth, a landscape artist as much as he is an illustrator, creating imagery born from the lines, textures, colors, and forms of the natural world. Dartmoor proved to be the perfect setting for an artist of Alan's temperament: a land of great and varied beauty, rich in history and myth, full of Bronze Age ruins, clapper bridges, and standing stones on the wind-swept hills.

In Arthurian lore, Merlin (the great magician of Arthur's court) retreats to the Forest of Celydonn after the Battle of Arderydd, living an elemental existence alongside the wolves and the deer. It is only after this retreat into nature that he comes fully into his magical powers -- an initiatory process echoed in myth cycles throughout the world. For Alan, the move to Devon was his own retreat into Celydonn. Wandering over the moor, through Wistman's Wood, and up winding paths by the River Teign, he came into his full powers as an artist, a magician upon the page.

The success of Faeries allowed him the time to pursue a project dear to his heart: paintings inspired by The Mabinogion, the great myth cycle of Wales. These magnificent tales are firmly rooted in the soil of the Welsh countryside, so he followed the threads of the stories to Dyfed and Snowdonia, soaking in the colors, forms, and spirit of these myth-haunted landscapes. Returning to his Devon studio with reference photos and sketchbook notes, Alan created a body of extraordinary paintings to accompany the Jones & Jones translation of the text. This edition of The Mabinogion, published in 1982, remains one of the artist's finest accomplishments to date.

Over the next several years, he continued to chose book projects with mythic resonance, such as Castles: a book of imagery drawn from myth, romance, and magical literature, with text by David Day; Merlin's Dream: Arthurian tales beautifully retold by Peter Dickinson; and two children's picture books: The Mirrorstone, with text by Michel Palin, and The Moon's Revenge, with text by Joan Aiken.

During these years he also pursued his second career as a concept artist and designer for feature films, working on such fantasy classics as Legend, directed by Ridley Scott, and Erik the Viking, directed by Terry Jones.*

In 1988, Alan was approached by J.R.R. Tolkien's publisher to create fifty new paintings for The Lord of the Rings, to be published in a handsome edition celebrating the centenary of Tolkien's birth. He immersed himself in this work for two years, resulting in illustrations so perfect, and so universally acclaimed, that they are now ineluctably bound with Tolkien's great story for readers all over the world.

"I first encountered The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings when I was eighteen," he remembers. "It felt as though Tolkien had taken every element I'd ever want in a story and woven them into one huge, seamless narrative. And, even more important for me, he had created a place -- a vast, beautiful, awesome landscape -- which lingered in the mind long after the protagonists had finished their battles and gone their separate ways."

How, I ask, does an artist even begin to approach a project like this? Particularly when illustrating a text that has meant so much to so many.

"Humbly," Alan says promptly. Then he pauses to give the question more thought. "Every artist works differently, of course, but my own approach to The Lord of the Rings was to allow the landscapes to predominate. In some of my scenes, the characters are so small they are barely discernible. This helped me to avoid, as much as possible, interfering with the pictures in the reader's mind, which tend to focus on the characters and their inter-relationships. My task lay in shadowing the heroes as they traveled on their epic quest -- often at something of a distance, coming closer at times of heightened emotion -- rather than simply re-creating the dramatic highpoints of the story. Later, when I illustrated The Hobbit, it no longer seemed appropriate to keep such a distance, particularly from the hero himself. I don't think I've ever seen a drawing of a hobbit which quite convinces me -- and I don't know whether I've gotten any closer to Tolkien's vision myself with my depiction of Bilbo. I'm fairly happy with my picture of him standing outside his home, Bag End, before Gandalf arrives and turns his world upside-down -- but I've come to the conclusion that one of the reasons Hobbits are so quiet and elusive is to avoid the prying eyes of illustrators."

In 1992, Alan began a journey into a very different kind of landscape when he agreed to illustrate The Illiad and The Odyssey, re-told for young readers by Rosemary Sutcliff. He'd loved these stories since childhood, and yet he hesitated before taking on the books.

"I was apprehensive," he explains, "about spending so much time on the battle plains of Troy when my natural home, and main source of inspiration, was the woods and sodden hills of Dartmoor. I'd rarely attempted to paint a landscape that wasn't at least as wet as the watercolors I worked in. I travelled to Greece, for the first time, with a copy of Pausanias as a guide, weighed down by paints, sketchpads, and camera. Most of the action takes place in Turkey, not Greece, but I'd heard that there wasn't a lot to see at the site of Troy itself, so I thought Mycenae would be a good substitute. I visited all the sites and museums I could, drawing artifacts and large crowds of Greek school children. I fell in love with all the Korai at the Acropolis; and, best of all, I went to Delphi. It had nothing to do with the story I was illustrating, but it's set in one of the most remarkable and beautiful landscapes I've ever seen."

Alan describes his research process as a way of "priming the pump," filling himself with ideas and images before he actually sits down to work. Though his painting process is an intuitive one, it is nonethless grounded in the real. Armed with hundreds of reference photos, sketchbooks filled with notes, and the visual impressions of his travels through Greece, he returned to his Devon studio to create a magical Greece that never was: half-way between myth and history, between Homer's world and the realm of the gods. The landscape, as always, came first -- and then he recruited family, friends, and neighbors to model for the extended dramatis personae of the tales. (I recall coming into his courtyard at the time to find a dying Odysseus laid out on the picnic table, Penelope swooning above him.)

Sadly, Rosemary Sutcliff died before the art was completed, and never saw her words brought so vividly to life in The Black Ships of Troy (winner of the Kate Greenaway Gold Medal) and The Wanderings of Oysseus.

At the end of the 1990s, Alan traveled to Wellington, New Zealand to begin work as Conceptual Designer of Peter Jackson's Lord of the Rings film trilogy; in 2004, he won an Academy Award for bringing Middle-earth to life on the big screen. For many years we didn't see much of him as labour on the films went on and on. But when they were done, and he finally came home, our small village felt 'right' again. His quietly presence had been deeply missed.

Other film jobs followed, but Alan managed to keep up with the book world too -- illustrating Tolkien's posthumous publications (The Silmarillion, The Children of H��rin, Beren and L��thien, etc.), as well as Shapeshifters: Tales from Ovid's Metamorphoses, and a splendid Folio Society edition of Old-English poetry. In between book and film projects, you'd often find him rambling the moor or sketching trees in the local woods: rendering the land he loved best in paintings, drawings, and etchings.

"I spend as much time as I can sketching from nature," he explains. "Dartmoor contains such a rich variety of landscape -- as many boulders, foaming rivers, and twisted trees as my heart could ever desire. When I look into a river, I feel I could spend a whole lifetime painting that river, from source to sea, and nothing else."

Alan works from a two-floor studio in an old stone barn half-smothered in ivy and roses. It's a magical place, with a silvery light and a sense of calm and tranquility -- despite an overflow of papers and books, and perpetual deadlines looming. In the large upstairs room, the walls are covered with etchings, drawings, and printers' proofs; the shelves hold rows of black sketchbooks filled with drawings, whimsical doodles, and notes; and the drawers are packed with paintings created through decades of steady work. Downstairs, an etching press sits among paintings boxed-up to ship to exhibitions. Across a courtyard is a second barn, newly renovated and largely empty -- a space adaptable for music, or dance, or solitary contemplation, whatever the moment might call for.

We sit in the cobbled courtyard now, tea, scones, and jam on the table before us. The white roses are in bloom, and music drifts down from an upper window.

"I like working in watercolor," Alan tells me," with as little under-drawing as I can get away with. I like the unpredictability of a medium which is affected as much by humidity, gravity, the way that heavier particles in the wash settle into the undulations of the paper surface, as by whatever I wish to do with it. In other mediums you are more in control, responsible for every mark on the page -- but with watercolor you are in a dialogue with the paint. It responds to you, and you respond to it in turn. It's a conversation. Printmaking also has this quality, this unpredictable element -- requiring an intuitive response, encouraging a spontaneity that allows the magic to happen.

"When I begin an illustration, I usually work up from small sketches -- which indicate, in a simple way, something of the atmosphere or the dynamics of the picture. Then I do drawings on a larger scale, supported by life studies from models if figures play a large part in the composition. When I've reached the stage where the drawing looks good enough, I'll transfer it to watercolor paper -- but the drawing is still fairly loosely rendered. I like to leave as much unresolved as possible before starting to put on washes of color. This allows for an interaction with the medium itself, a dialogue between me and the paint. Otherwise it's too much like painting by number, or a one-sided conversation."

I know so many young artists who look up to Alan, so I ask him which artists he looked up to himself in his youth. He answers readily:

"I was strongly influenced, in technique as well as subject matter, by the early 20th century book illustrators -- Arthur Rackham and Edmund Dulac in particular. And by Burne-Jones and other Pre-Raphaelites. Also by the various artists of the Arts-&-Crafts movement in England and Scotland. Going further back, I'm continually inspired by Rembrandt, Breughel (I've often wondered whether his brilliant "Tower of Babel" inspired Tolkien's description of Minas Tyrith), Hieronymous Bosch, and Albrecht Durer. It's not that these earlier artists have influenced my pictures in any obvious way, but that their example raises my spirits, and re-affirms my belief in the power of images to move and delight us. They show me how much further I have to go, and how much is possible."

We'd been in Florence and Venice together with a group of friends, so I bring up the Italian Renaissance painters and Alan's face lights up.

"I'd always liked the Italian masters," he says, "but now I'm completely besotted with Botticelli, Bellini, da Vinci, and the rest. To see their work in its natural landscape and light is a revelation. The paintings are calm, controlled, and yet each face, each form, each hill or flower or tree contains such passion. In Botticelli's paintings, every pebble and every leaf is rendered with a religious devotion. There's a reverence inherent in paying such close attention to every stone...turning painting itself into a form of worship, an act of prayer. I'm still thinking about it, still working through what effect this may have on my own approach to drawing and painting."

I ask whether he, too, sees painting as an act of communication with something beyond our human ken: God, Mystery, call it what you will.

"Yes," he answers slowly, "but perhaps in a more mythological sense than the religious orientation of the Renaissance. To draw a tree, to pay such close attention to every aspect of a tree, is indeed an act of reverence -- not only toward the tree, but toward our human connection to the tree, and to nature. It is one of the magical things about drawing: it gives us almost visionary moments of connectedness. Every element (hair, wind, rocks, water) is portrayed with one material (graphite, ink, paint) which binds it all together, bringing out the harmony that we know, and science confirms, exists in nature -- created as it is, as we all are, by particles that have existed since the dawn of the universe.

'This is the power of myth as well: it binds to the natural world. There have always been mythic tales of figures whose function is to act as an intermediary between humanity and nature: the shaman, the shape-shifter, the trickster, the embodiments of creative power, appearing in myths, fairy tales, and medieval legends all around the world. Often they have a touch of 'divine madness' -- like Merlin, or Shuibhne in Ireland, during their years of exile and madness in the woods, through which they gained their divinatory powers. It's interesting to me that in our century it is often artists who fulfill this function. And who, in popular stereotype, are given the license to be a bit mad. Look at Picasso, a classic trickster figure if there ever was one.

"The power of both myth and art," he continues, "is this magical ability to open doors and to make connections -- not only between us and the natural world, but between us and the rest of humanity. Myths show us what we have in common with every other human being, no matter what culture we come from, no matter what century we live in. And at the same time, mythic stories and art celebrate our essential differences.

"When I first encountered Greek myths as a child, the stories provoked a degree of excitement that can't be explained by their value as adventures, however great that may be. Although the stories were new to me, I felt a sense of recognition. My response to them, in particular to the otherworldly elements, suggests they were meeting a spiritual need that had not been touched by dull lectures at school, or the church services I regularly dozed through. I'm not suggesting that I wanted to sacrifice a bull to Zeus or consult a Sybil -- I didn't known any Sybils -- but that I'd found, unconsciously, a wider and deeper context for my hopes and fears. Myth gave me a sense of continuity and communion with the people of different times and cultures, and an enhanced and more imaginative relationship with the natural world."

The intersection of myth and art can indeed produce a form of magic connecting us to the numinous world -- and this is evident in the timeless beauty of Alan's illustrations of classic tales. The wandering paths of Middle Earth, the great green valleys of ancient Wales, the vistas over the plains of Troy, and twisted trees of the Devon woods all create a spell as potent and lasting as any conjured by Merlin himself.

Yet the quiet magician behind the paintings seems unaware of the power of the magic he creates with pencil, pen and brush.

"I keep drawing the trees, the rocks, the river," he says. "I'm still learning how to see them. I'm still discovering how to render their forms. I will spend a lifetime doing that. Maybe someday I'll get it right."

The paintings, drawings, sculptures, & photographs above are under copright by Alan Lee, and may not be reproduced without his permission; all rights are reserved by the artist. The pictures are identified in the picture captions. (Run your cursor over the images to see them.)

August 31, 2020

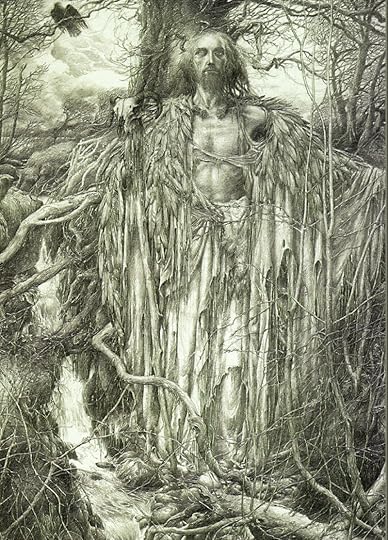

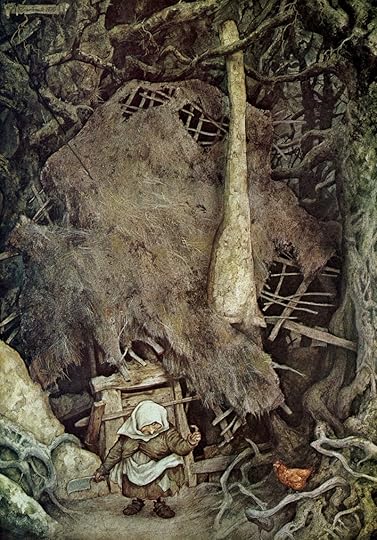

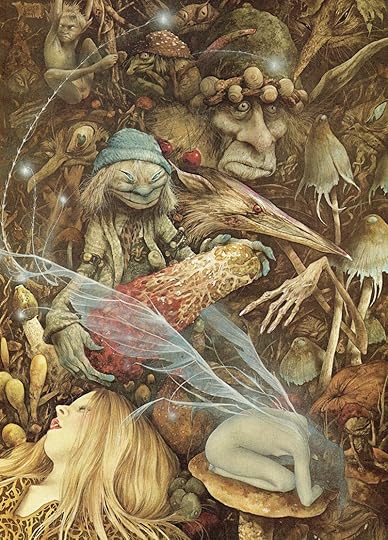

The Faerie Art of Brian & Wendy Froud

For those here and on social media who mentioned how much they loved Brian Froud's art in yesterday's post, here's a closer look at his work, which is deeply entwined with that of his wife Wendy Froud, a sculptor, puppet designer, and doll artist. They live close by here on Dartmoor, are old friends and colleagues, and I love them dearly.

The Froud family's thatch-roof farmhouse sits buried in ivy down a quiet country lane in England's West Country. Its old front door, with a goblin door-knocker, is a doorway into Faerieland. Inside is the kind of enchanted house one usually finds only in fantasy books: full of carved medieval furniture and tapestries, costumes, masks, old books, puppets and magical props from films. Faeries, goblins, trolls and sprites stare down from Brian's paintings on the walls, and cavort in the shape of magical dolls and sculptures created by Wendy.

Brian was born in Hampshire, raised Kent, and studied at the Maidstone College of Art. His deep involvement with folklore and myth began during his student days, he says, when he came across a book illustrated by Arthur Rackham in his college library. Rackham's goblins, faeries, undines, and tree folk re-awakening Brian's interest in the myths and legends he'd loved in childhood. He began to study the folklore of Britain, and then the tales of other lands, fascinated by the ways the magical traditions in all cultures shared common roots. When he left collage, Brian spent five years in London working in the field of commercial illustration, but he continued to paint mythic images and to develop a distinctive style of his own. (This early work was published in Once Upon a Time and The Land of Froud, both from David Larkin's Peacock Press.)

In 1975, Brian moved from London to Dartmoor, sharing a house with fellow-illustrator Alan Lee and his family. Inspired by the woods and hedgerows of Devon, and the ancient, myth-steeped landscape of the moor, the two collaborated on Faeries, an illustrated book of British faery lore. This marvelous, ground-breaking volume quickly became an international bestseller, and has influenced artists, writers, and folklorists all around the world in the decades since.

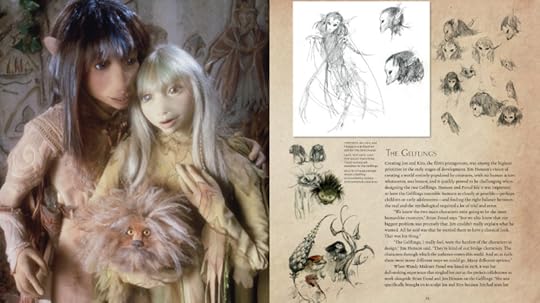

Brian's faeries and magical vision of the world so impressed the American filmmaker Jim Henson (creator of the Muppets) that he asked Brian to come to New York to design two feature films: The Dark Crystal and Labyrinth. Like Faeries, the films were ground-breaking -- pioneering new puppet design and performance techniques. It was on the set of The Dark Crystal that Brian met Wendy, who created the "gelflings" and other creatures for the film. (In the photo below the two of them are at work in the Dark Crystal workshop.)

Wendy was born and raised in Detroit, Michigan. "Both of my parents were artists," she says. "I've been a doll-maker all of my life. At about age five, as soon as I could bend a pipe-cleaner and bits of fabric together, I started to make the kind of dolls I couldn't find in stores: centaurs, satyrs, fauns, unicorns, and faeries. I wanted to be part of a magical realm, and so I created one for myself."

Wendy studied music and drama at Interlochen Arts Academy, then fabric design, jewelry, and ceramics at The Center for Creative Studies in Detroit. After graduation, she moved to New York City and landed a job which drew all her training together: working as a sculptor and puppet fabricator in Jim Henson's Creature Shop. Wendy worked on a number of different Henson projects, making puppets for The Muppet Show and The Muppet Movie, and the original prototype for Yoda in Star Wars. It was on the set of The Dark Crystal, however, with its imagery rooted in folklore and myth, that she found her greatest satisfaction, working with the shy-but-brilliant English faery artist at the heart of the film.

She married Brian during the filming of The Dark Crystal, was pregnant when work on Labyrinth began, and soon after gave birth to Toby, their son. The timing was co-incidental, but perfect. Toby ended up with a role in the film: playing the baby stolen by the Goblin King (David Bowie) and rescued by his sister (Jennifer Connelly).

After the films were done, the Froud family returned to Brian's village on Dartmoor. Rather than squeezing into his old cottage, a tiny place in the center of the village, they renovated a rambling Devon "longhouse" out in the countryside: a thatched granite building dating from medieval times, built over older Saxon foundations. In this atmospheric place, they set about creating a thoroughly magical environment filled with faeries, goblins, trolls, William Morris fabrics, antique toys, and shelves crowded with folklore texts. Brian set up a painting studio in a large room to one side of the house's central hall, while Wendy created two work spaces: a doll workshop in the eaves of the house, and a sculpting studio in the garden.

Although the Frouds never left film work altogether, during the years when Toby was young they chose to live more quietly in Devon, concentrating on creating art inspired by myths, legends, and fairy tales.

While Brian painted faeries and goblins, Wendy brought these same creatures to life in three-dimensional form, made of fimo, plaster, resin, cloth, feathers, leaves, and numerous other things -- mixing traditional art materials with found objects from the Devon woods. Some of Wendy's art is based on, or in dialogue with, Brian's paintings and sketches, while the rest explores a rich visual vocabulary that is uniquely her own.

Brian has largely concentrated on what could be called "faery portraiture," building a large, wide-ranging body of work informed by the colors, shapes, and textures of the land around him. "I've been actively engaged with mythic imagery ever since I picked up that Rackham book," he says, "but it really came into focus for me when I moved from London to Dartmoor. As I walked through the woods and over the moor, I looked at the trees and the rocks and the hills and I could see the personality in those forms, metamorphosing into faeries, goblins, trolls, and other nature spirits.

"After Alan and I published Faeries, he moved on from folklore to illustrate Tolkien and other literary works -- but I discovered that my own exploration of the Faerie Realm had only just begun. The faeries kept insisting on taking form under my pencil, emerging on the page before me, cloaked in archetypal shapes drawn from nature and myth. I'd attracted their attention, and they hadn't finished with me yet.

"I'm often called a 'fantasy' painter, " Brian notes, "but that's not quite accurate. My imagery comes from myth, folklore and the old oral story-telling tradition, not from fantasy literature; and although I did some commercial illustration in my youth, I don't see myself as an illustrator now. I publish books, but the paintings in them are personal visions and expressions, not illustrations of someone else's story. The pictures come first, and the text responds to the pictures, not the other way around. I have to confess that, unlike Wendy, I rarely read fiction at all. Most of my reading is nonfiction: history, mythology, archetypal psychology, and the like. I prefer the enchantment of a story told to one that is written down. In the oral tradition, where stories are told around the fireplace in semi-darkness, the words are alive: they leave the lips, enter into the air, and before they fall onto your ear they transform themselves into magic. They're not fixed; they change from telling to telling, and from listener to listener.

"I want my pictures to have that same quality of mutability. I don't like things to be fixed too solidly or explained too fully; I want each viewing to be like a re-telling of a tale, full of new possibilities. Back in my illustration days, I worked on a book called The Wind Between the Stars, and that was an interesting technical challenge, for how does one draw the wind? The work I do today still has that sort of challenge: drawing things that are normally beyond human perception, turning the invisible world of Faerie into visible form. Myth surrounds us every day, particularly in a landscape as soaked in history and old stories as Dartmoor. If I do my job well, not only does myth become visible within a painting, but that painting becomes a doorway into a new way of looking at the world. You turn and look at the land around you, and you begin to see the faces in the trees and faeries flitting through the shadows."

It is clear that his work gives Brian great satisfaction, but I've also seen him struggle with his art. What, I ask, is the most difficult thing about rendering his vision of the world and its magical spirit in paint?

Brian ponders the question, then answers slowly, "The hardest part -- or one of the hardest parts, because there are many hard parts -- is convincing the viewer that what I've depicted is true; that I've got it right. When Cocteau was making his classic film Beauty & the Beast, he was reaching for what he called 'the supernatural within realism' -- in other words, grounding fantastical elements with ordinary imagery, which gives plausibility to the first and enchantment to the second. I think this is important to mythic art no matter what the medium: painting, writing, filmmaking. You need realism as an underpinning, an anchor, for the magic.

"In order to obtain the 'supernatural within realism,' I usually start my larger, complex paintings with a human image," he explains. "The familiarity of the human form provides a touchstone and a reference; and then as we continue on in our journey around the picture, encountering stranger and stranger imagery, we have confidence that these faeries look just as they're supposed to look. We know that the distortions in their forms or faces are deliberate, not just a stylistic aberration or bad drawing. Every distortion in my paintings actually has a precise meaning behind it. In traditional lore, one often finds that faeries have some striking defect of form: some are hollow-backed or elongated, others have goat- or lion-feet. Heads, hands, and feet are often large in proportion to the rest of the body. This is due to the plastic nature of faery forms, which are often glimpsed in states of transition from one shape to the next.

"I start each painting by drawing a geometrical grid based on the Golden Section, a system of proportions and perspective developed by the ancient Greeks. The grid is overlaid with circles, triangles and the like, and where these things cross over is where I place the major figures. This gives the 'chaos' of a crowded painting an underlying structure of order. The central human figure is generally based on a photograph -- again, this provides an  underpinning of reality for the more fantastical aspects. I take my own photographs of models: friends and neighbors generally. The imagery surrounding the central figure is always in relationship to it. These secondary creatures are often drawn from earlier sketches -- I have many, many sketchbooks filled with such things.

underpinning of reality for the more fantastical aspects. I take my own photographs of models: friends and neighbors generally. The imagery surrounding the central figure is always in relationship to it. These secondary creatures are often drawn from earlier sketches -- I have many, many sketchbooks filled with such things.

"I always try to keep the drawing fairly loose; I don't like to get tight at this stage, which closes down possibilities. And even in the final stages of a painting I strive to maintain a looseness and a sense of...mystery. I find that in the fantasy genre, too many young painters over-paint their pictures; they're a bit too...over-wrought for my taste. They're much too bright and shiny. The artist has finished every detail, and every edge is hard and bright -- which doesn't allow me into their world, my eye slides right off that shiny surface. I prefer to keep my rendering as loose as possible, just on the edge of being finished. I want a painting to give just enough information for the picture to make sense; there should always be a little bit kept back, a few pieces missing, which the viewer must supply himself. In doing that, the picture comes to life. It becomes part of a reciprocal process, a communication. The painting allows you inside, where it can grow, and you can grow."

Despite the world-wide success of Faeries, and the huge acclaim he received for the Henson films, it often astonishes Brian's fans to know that it took him over ten years to find a publisher for his subsequent work.

"There were times when I thought I was mad to continue painting faeries," he recalls. "But I was driven to do it. I had a vision and I couldn't seem to let it go. So I said to myself: What do I have to do to convince a publisher that there's an audience for this art? I decided a humorous approach might open the door; it might perhaps be less intimidating. That's when the idea for Lady Cottington's Pressed Fairy Book came to mind.

This volume tells the story a Victorian young lady who "presses" fairies between book pages, much as her compatriots pressed and collected flowers. With art by Brian and text by Terry Jones (of Monthy Python fame), the book is utterly hilarious...and, like Faeries, it was a best-seller. To Brian's relief he had finally proved there was indeed an audience for his art.

More books in the Cottington series followed: Lady Cottington's Pressed Fairy Letters, Lady Cottington's Fairy Album, Strange Staines & Mysterious Smells, and, most recently, The Pressed Fairy Journal of Madeline Cottington. The latest volume was written by Wendy, as fine an author as she is a sculptor, telling the story of this mad, faery-hunting family from Victorian times to the present. (Go here to see the book trailer video, by Toby Froud. Artist Virginia Lee plays Angelica Cottington, the original fairy hunter in the family, and my husband, Howard, plays her twin brother Quentin, a mad inventor.)

The success of the "pressed fairies" allowed Brian to publish his other paintings of the Faerie Realm, collected in books such as Good Faeries/Bad Faeries, The Runes of Elfland, and Brian Froud's World of Faerie, a sumptuous overview of his art. Although less whimsical than the Cottington series, these volumes also have their humorous side. "Just like the old faery lore," he notes, "moving back and forth between between light and shadow."

Meanwhile, Wendy was creating art for exhibition, teaching, writing, and publishing magical books of her own: the Old Oak Wood series for children (A Midsummer Night's Faery Tale, The Winter, The Faeries of Spring Cottage), and The Art of Wendy Froud.

Behind the scenes, she was also involved with Brian's publications, sometimes editing or ghost-writing the text. This evolved into full collaboration between the two artists in Trolls and Faeries' Tales, gorgeous editions designed by Brian, written by Wendy, and featuring art by both.

More recently, the two of them had a busy year going back and forth to a film studio near Windsor to work on The Dark Crystal: The Age of Resistance, a tour-de-force of the puppetry art. Their son Toby, all grown up and a film puppeteer and director himself, was the Design Supervisor for The Age of Resistance, making sure the aesthetic vision of the original film was faithfully translated to the new series.

Since then, other television and stage projects have been afoot, slowed down by the Covid-19 pandemic but still moving forward. The Frouds spent the months of lockdown in their old Devon longhouse, engaged as always with the land, its spirits, and the stories in the green world around them.

As our discussion ends, Brian sits back and reflects on his long journey with the faeries:

"After all these years of drawing, painting, and sculpting them, Wendy and I are often asked if we 'believe' in faeries. The best answer I can give is that I don't have much of a choice in whether I believe in them or not, for they seem to insist on my painting them. I paint by intuition, and faeries keep appearing on the page before me. Mind you, it's not that I lie around on a chaise longue waiting for inspiration to strike -- painting is a discipline and I'm in my studio working a regular work day from 9 to 5. But on a Monday morning I'm often not sure what exactly I'm going to be doing next. I'll get out my tools, I'll get to work, and something will demand to come through -- some creature will form on the page before me, demanding to say: Hello!"

"Faeries are spirits of nature," notes Wendy. "They embody the wild, mysterious and spiritual forces to be found in nature, and help us to reconnect with wonder and mystery inside our own souls. Our ancestors passed these stories and images down for hundreds, thousands of years. As artists, Brian and I are merely part of a long tradition -- giving old tales new life and passing them on to the generations to come. I look at my sculptures as signposts or gateways into the realm of Faerie. I like to think that they can help people find their own way into that realm."

"Traditional cultures have always recognized and honored the animate spirits of the earth," Brian adds, "but in western culture we've rather left that behind...to our spiritual cost, and ecological peril. Now we're beginning to recognize how important it is to have a vibrant relationship with the land beneath our feet...and that the old stories and mythic imagery can aid this process."

"In other words," says Wendy with a smile, "we need the faeries, especially now. So Brian and I will keep telling their stories, for as long as they want us to."

The paintings, drawings, sculptures, & photographs above are under copright by Brian & Wendy Froud, and may not be reproduced without their permission; all rights are reserved by the artists. The title of each artwork can be found in the picture captions. (Run your cursor over the images to see them.)

The end of summer

Here in the UK, it's the last day of a long holiday weekend marking the end of summer, and already there is a chill in the air, a presage of the turning seasons. Wherever in the world you are -- whether it's the end of summer or the end of winter -- and whether the movement through nature's cycles makes for dramatic or subtle change -- we stand on the threshold "betwixt and between," poised between the old season and the new.

The old hedge-witches of the Devon countryside would tell you that this is a time for letting go of old troubles, old animosities, and out-dated ideas that no longer serve; it's also a time of renewal, revitalization, and travelling new paths in the days ahead. Carry acorns in your pocket for luck; yarrow for resilience; rosemary for protection of the spirit. Give the first blackberries back to the land, the first splash of cider to the apple trees. Leave milk out for the Good Folk, or a dram of whiskey, or a plate of beans. As we begin new jobs, new terms at school, new works of art or any other endeavors, we are counselled to take a moment on the threshold, pausing between the old and new to honour the magic of the in-between. Leave flowers or feathers, a poem or a prayer....

And then keep on walking.

The art above is by my friend and neighbour Brian Froud. All rights reserved by the artist.

August 28, 2020

Some exciting news....

Dr. Rob Maslen and Dr. Dimitra Fimi, the good people who run the Masters in Fantasy programme at the University of Glasgow, have successfully obtained funding to establish a new Centre for Fantasy and the Fantastic -- which will be the first of its kind anywhere. They've already created an extraordinary community of scholars in Glasgow, and the new centre is wonderful news for our field.

They are launching the centre with a online lecture by my dear friend Ellen Kushner, which I have no doubt will be splendid. Ellen will be talking about her creative practice and her award-winning novel Thomas the Rhymer (based on Scottish balladry), followed by a question-and-answer session.

They are launching the centre with a online lecture by my dear friend Ellen Kushner, which I have no doubt will be splendid. Ellen will be talking about her creative practice and her award-winning novel Thomas the Rhymer (based on Scottish balladry), followed by a question-and-answer session.

Afterwards, I'll be on a panel with two of the field's most brilliant scholars, Rob Maslen and Brian Attebery, discussing the future of fantasy.

The launch event is open to all, so please come join us. Tickets are free, but they're limited (due to space in the Zoom webinar room), and they're going fast. For more information, and to register for a ticket, please go here.

I'm very excited about the new centre, and also about this online event. Thank heavens our phone wires and Internet have finally been fixed! Prior to this, stormy weather kept knocking me off-line, which disastrous for my last online event (a panel discussion for ReConvene). We're having stormy weather again as I write this post, and the line is now holding up just fine.

But I think I'd better leave a dish of butter out to appease the fairies of Dartmoor just in case...

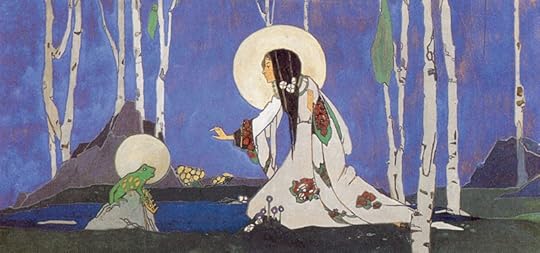

The paintings and drawings above are by Jessie M. King (1875-1949), who studied at the Glasgow School of Art. To see more of her work, go here.

August 26, 2020

Myth & Moor update

I'm almost frightened to say this lest I jinx it, but we seem to have a working Internet connection again. After many engineer visits and replacing of phone lines and puzzled scratchings of heads, the last set of repairs seems to have changed something. It's still rural Internet and not super-fast, but it's usable (touch wood), and we're not getting kicked off of it every five minutes. We are back in the modern world at last, and now I just hope we can stay here.

I have a gazillion missed messages to catch up on, which I'll be focused on for the next few days -- and then I'll be back to a regular Myth & Moor schedule on Monday.

I hope you're all having a good end-of-summer, and staying safe. Tilly sends her love.

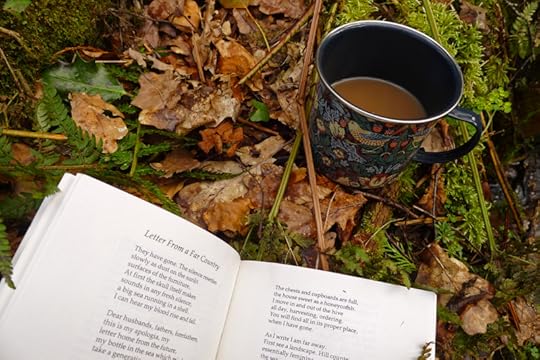

The poem glimpsed above is "Letter From a Far Country' by Welsh author Gillan Clarke.

August 19, 2020

Myth & Moor update

Apologies for my absence online. We're still having connectivity problems with our rural broadband, and we're still trying to get it fixed. At this point, messages by bird would be faster.... I'll be back just as soon as I can be. Wish us luck!

Art by Christian Schloe.

August 13, 2020

Tell all the truth but tell it slant

From "The Value of Fantasy and Mythical Thinking" by Katherine Langrish:

"Karen Armstrong claims that religion is an art, and I agree with her. In her book A Short History of Myth she examines the modern expectation that all truths shall be factually based. This is what religious fundamentalists and scientists like Richard Dawkins have, oddly, in common. A religious fundamentalist refuses to accept the theory of evolution because it appears to him or her to disprove the truth of Genesis, when what Genesis actually offers is not a factual but an emotional truth: a way of accounting for the existence of the world and the place of people in it with all their griefs and joys and sorrows. It���s ��� in other words ��� a story, a fantasy, a myth. It���s not trying to explain the world, like a scientist. It���s trying to reconcile us with the world. Early people were not na��ve. The truth that you get from a story is different from the truth of a proven scientific fact.

"Any work of art is a symbolic act. Any work of fiction is per se, a fantasy. In the broadest sense, you can see this must be so. They are all make-belief. Tolstoy���s Prince Andr�� and Tolkien���s Aragorn are equal in their non-existence. Realism in fiction is an illusion -- just as representational art is a sleight of hand (and of the mind) that tricks us into believing lines and splashes of colour are ���really��� horses or people or landscapes.

"The question shouldn���t be ���Is it true?���, because no story provides truth in the narrow factual sense. The questions to ask about any work of art should be like these: ���Does it move me? Does it express something I always felt but didn���t know how to say? Has it given me something I never even knew I needed?��� As Karen Armstrong says, 'Any powerful work of art invades our being and changes it forever.' If that happens, you will know it. It makes no sense at all to ask, ���Is it true?���

"Fantasy still deserves to be taken seriously -- read and written seriously -- because there are things humanity needs to say that can only be said in symbols. Here���s the last verse of Bob Dylan���s song ���The Gates of Eden��� (from Bringing it All Back Home):

At dawn my lover comes to me

And tells me of her dreams

With no attempts to shovel the glimpse

Into the ditch of what each one means

At times I think there are no words

But these to tell what���s true:

And there are no truths outside the Gates of Eden.

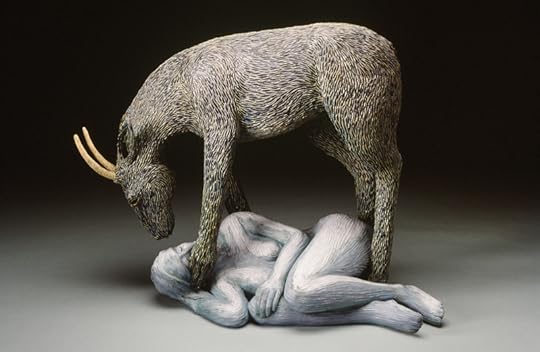

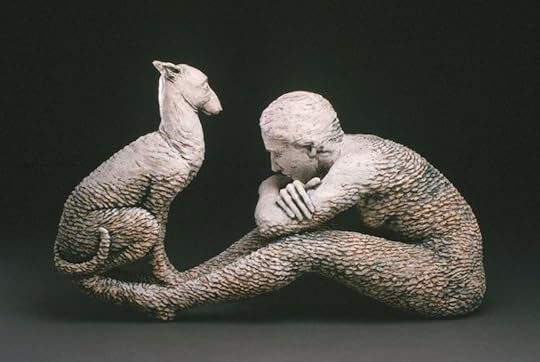

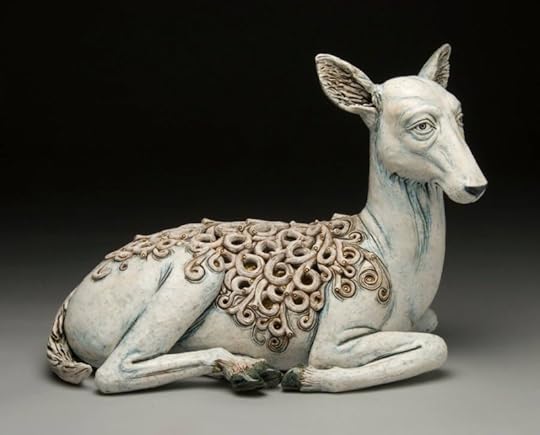

The mythic imagery today is by Adrian Arleo, an American ceramic artist who lives and works outside Missoula, Montana. She studied Art and Anthropology at Pitzer College, received an M.F.A. in ceramics from the Rhode Island School of Design, and has been Artist in Residence at Oregon College of Art and Craft and the Sitka Center For Art and Ecology. Her work is exhibited and collected around the world.

"For over thirty years, my sculpture has combined human, animal and natural imagery to create a kind of emotional and poetic power," she writes. "Often there's a suggestion of a vital interconnection between the human and non-human realms; the imagery arises from associations, concerns and obsessions that are at once intimate and universal. The work frequently references mythology and archetypes in addressing our vulnerability amid changing personal, environmental and political realities. By focussing on older, more mysterious ways of seeing the world, edges of consciousness and deeper levels of awareness suggest themselves."

Please visit the artist's website to see more of her wonderful work.

Words: The Katherine Langrish passage quoted above is from"The Value of Fantasy and Mythical Thinking" (An Awfully Big Blog Adventure, October 17, 2009); all rights reserved by the author. You can read the full piece here. I also recommend Kath's excellent essays on folklore, fairy tales, and fantasy literature, which you can find on her blog, Seven Miles of Steel Thistles, and in her book of the same name. The title of today's post, of course, is from an Emily Dickinson poem.

Pictures: Adrian Arleo's ceramic works above are Heard II, Heard I, Sirens of Rutino & Artemis/Diana II, Night, Apparition, Consider, Earth/Horse Teapot with Dog Lid, Glade & Dormant Honey Comb Woman, and Matrimony. All rights reserved by the artist.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 710 followers