Terri Windling's Blog, page 115

May 17, 2016

From the archives: Daydreams and spells

I'm afraid it's another post pulled from the archives today (first posted in 2013), as I'm having a week in which the time and spoons for all I need to do is in short supply. I do like re-visiting these old posts, though, and seeing the different kinds of conversations they spark a few years the road. Which reminds me that I must also apologize for taking so long to respond to comments. I am reading all the comments (and poems!) as they come in, and will go back and respond properly just as soon as pressing work deadlines ease. In the meanwhile, I'm so grateful to all of you here who keep the discussion going. It's what makes this blog feel like more than just mine; it is made by a whole community.

The passage below is from "Why our future depends on libraries, reading, and daydreaming," a lecture by Neil Gaiman in which he argues not only for the value of reading, bless him, but also for the value of stories often dismissed as "escapist."

"Fiction can show you a different world," Neil says. "It can take you somewhere you've never been. Once you've visited other worlds, like those who ate fairy fruit, you can never be entirely content with the world that you grew up in. Discontent is a good thing: discontented people can modify and improve their worlds, leave  them better, leave them different. And while we're on the subject, I'd like to say a few words about escapism. I hear the term bandied about as if it's a bad thing. As if 'escapist' fiction is a cheap opiate used by the muddled and the foolish and the deluded, and the only fiction that is worthy, for adults or for children, is mimetic fiction, mirroring the worst of the world the reader finds herself in. If you were trapped in an impossible situation, in an unpleasant place, with people who meant you ill, and someone offered you a temporary escape, why wouldn't you take it? And escapist fiction is just that: fiction that opens a door, shows the sunlight outside, gives you a place to go where you are in control, are with people you want to be with (and books are real places, make no mistake about that); and more importantly, during your escape, books can also give you knowledge about the world and your predicament, give you weapons, give you armour: real things you can take back into your prison. Skills and knowledge and tools you can use to escape for real.

them better, leave them different. And while we're on the subject, I'd like to say a few words about escapism. I hear the term bandied about as if it's a bad thing. As if 'escapist' fiction is a cheap opiate used by the muddled and the foolish and the deluded, and the only fiction that is worthy, for adults or for children, is mimetic fiction, mirroring the worst of the world the reader finds herself in. If you were trapped in an impossible situation, in an unpleasant place, with people who meant you ill, and someone offered you a temporary escape, why wouldn't you take it? And escapist fiction is just that: fiction that opens a door, shows the sunlight outside, gives you a place to go where you are in control, are with people you want to be with (and books are real places, make no mistake about that); and more importantly, during your escape, books can also give you knowledge about the world and your predicament, give you weapons, give you armour: real things you can take back into your prison. Skills and knowledge and tools you can use to escape for real.

"As J.R.R. Tolkien reminded us, the only people who inveigh against escape are jailers."

In her lovely biographical essay "Spells of Enchantment," Helen Pilinovsky notes how all kinds of children are in need of escapism, even those who don't come from particularly troubled homes:

"Fairy tales, fantasy, legend and myth...these stories, and their topics, and the symbolism and interpretation of those topics...these things have always held an inexplicable fascination for me," she writes.  "That fascination is at least in part an integral part of my character ��� I was always the kind of child who was convinced that elves lived in the parks, that trees were animate, and that holes in floorboards housed fairies rather than rodents.

"That fascination is at least in part an integral part of my character ��� I was always the kind of child who was convinced that elves lived in the parks, that trees were animate, and that holes in floorboards housed fairies rather than rodents.

"You need to know that my parents, unlike those typically found in fairy tales ��� the wicked stepmothers, the fathers who sold off their own flesh and blood if the need arose ��� had only the best intentions for their only child. They wanted me to be well educated, well cared for, safe ��� so rather than entrusting me to the public school system, which has engendered so many ugly urban legends, they sent me to a private school, where, automatically, I was outcast for being a latecomer, for being poor, for being unusual. However, as every cloud does have a silver lining ��� and every miserable private institution an excellent library ��� there was some solace to be found, between the carved oak cases, surrounded by the well���lined shelves, among the pages of the heavy antique tomes, within the realms of fantasy.

"Libraries and bookshops, and indulgent parents, and myriad books housed in a plethora of nooks to hide in when I should have been attending math classes...or cleaning my room...or doing homework...provided me with an alternative to a reality I didn't much like. Ten years ago, you could have seen a number of things in the literary field that just don't seem to exist anymore: valuable antique volumes routinely available on library shelves; privately run bookshops, rather than faceless chains; and one particular little girl who haunted both the latter two institutions. In either, you could have seen some variation upon a scene played out so often that it almost became an archetype:

"Libraries and bookshops, and indulgent parents, and myriad books housed in a plethora of nooks to hide in when I should have been attending math classes...or cleaning my room...or doing homework...provided me with an alternative to a reality I didn't much like. Ten years ago, you could have seen a number of things in the literary field that just don't seem to exist anymore: valuable antique volumes routinely available on library shelves; privately run bookshops, rather than faceless chains; and one particular little girl who haunted both the latter two institutions. In either, you could have seen some variation upon a scene played out so often that it almost became an archetype:

"A little girl, contorted, with her legs twisted beneath her, shoulders hunched to bring her long nose closer to the pages that she peruses. Her eyes are glued to the pages, rapt with interest. Within them, she finds the kingdoms of Myth. Their borders stand unguarded, and any who would venture past them are free to stay and occupy themselves as they would."

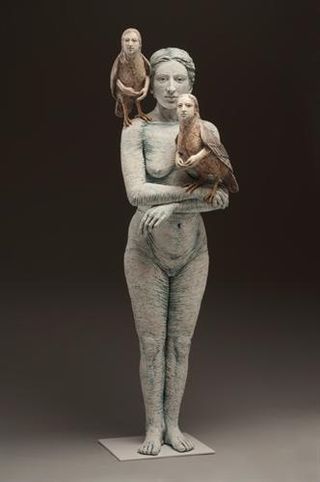

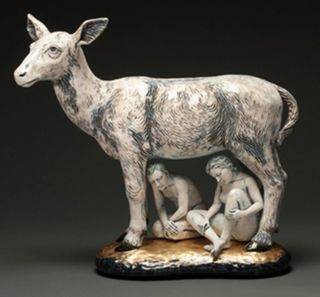

The exquisite mythic sculpture above and below is by Adrian Arleo, a ceramic artist in Lolo, Montana. "For over fifteen years," says Arleo, "I've been creating sculpture that combines human and animal imagery in a variety of ways. Some of these works elude to a relationship of understanding or connection between the human and animal realms. In others, the human figures possess animal faces, limbs, or other features in a way that reveals something hidden about the character or primal nature of the person.

"The Honey Comb sculptures are another variation on blending the human form with elements from nature. What appeals to me about the quality of this material is its appearance of simultaneously growing and deteriorating. I also like the way the wax approximates the material created by bees, enabling the work to be visual, tactile, and appealing to the sense of smell, like fresh honeycomb. On the flip side, the work might suggest the swarming, stinging insects that create this beautiful material. As with many things in life, beauty and the grotesque can cohabitate."

To see more of her beautiful work, go here. To read an interview with the artist, go here.

The passage by Neil Gaiman is from a lecture delivered to The Reading Agency at the Barbican in London (October 14, 2013), subsequently printed in The Guardian (October 15, 2o13). Follow the link to read it in full. The passage by Helen Pilinovsky is from an essay published in The Journal of Mythic Arts (2001). I recommend reading both essays in full. All rights to the text & imagery above reserved by the authors & artist.

The passage by Neil Gaiman is from a lecture delivered to The Reading Agency at the Barbican in London (October 14, 2013), subsequently printed in The Guardian (October 15, 2o13). Follow the link to read it in full. The passage by Helen Pilinovsky is from an essay published in The Journal of Mythic Arts (2001). I recommend reading both essays in full. All rights to the text & imagery above reserved by the authors & artist.

May 16, 2016

The art of hope

I'm still immersed in Conversations with Barry Lopez by William E. Tydeman, allowing myself only a few pages during my coffee break in the woods each day, drawing the book out and taking the time to really think about what I'm reading. Today, I'm struck by following passage on "hope" -- for "hope" and "goodness," it seems to me, are too often portrayed as banal, Pollyanna-ish qualities, when in fact it takes great courage and clarity of mind to reject despair, reach for the light and make something beautiful and whole out of lives and times so dark and fractured.

The passage begins with Lopez noting his desire to explore the relationship between emotion and landscape in the context of nature writing (a publishing label, I should acknowledge, that he personally dislikes). And the single emotion that he's most interested in exploring this way is hope.

The passage begins with Lopez noting his desire to explore the relationship between emotion and landscape in the context of nature writing (a publishing label, I should acknowledge, that he personally dislikes). And the single emotion that he's most interested in exploring this way is hope.

"I think you can evoke aspects of the land in prose in a way that makes people hopeful about their lives, " he says. "I think you can also describe landscapes that are not just physically but metaphysically dreary, and that those descriptions can make a readers lose a sense of hope about the subtle possibilities of their own lives. For me -- and maybe there is some mode of critical thinking about his -- the creation of story is a social act. It's driven by individual vision, of course, but in the end I think story is social, and part of what makes it social is this impact it can have on the psyche of the reader.

"My sense is that story developed in parrallel with the capacity to remember in Homo sapiens. I don't mean 'Where did we cache the food last spring?' but memory operating at a more esoteric level, recalling, say, the circumstances that induced loving behavior. Story, it seems to me, begins as a mnemonic device. It carries memory outside the brain and employs it in a social context. So you could say a person hears a story and feels better; a person hears the story and remembers who they are, or who they want to become, or what it is that they mean. I think story is rooted in the same little piece of historical ground out of which the capacity to remember and the penchant to forget come."

After reading these words, I flip back to the book's introduction by William Tydeman and find this passage I'd marked last week:

"Most times when Lopez speaks of hope, I am reminded of the simple-minded approach so many critics and intellectuals take toward place-based writing and its expression of hope. Lopez and I agree with an analysis made by Christopher Lasch, who conveys a nuanced view of the multilayered meaning of hope. He argues that 'Hope asserts the goodness of life in the face of its limits.' Hope does not require a belief in progress or prevent us from expecting the worst but, rather, hope 'trusts life without denying its tragic character. Progressive optimism, often confused with hope, is based on a denial of the natural limits of human power and freedom -- a blind faith that things will somehow work out for the best. It is not an affective anecdote to despair.' Those who challenge the status quo and support the popular uprising for social justice 'require hope, a tragic understanding of life, the disposition to see things through.' Hope is what we need."

It is indeed.

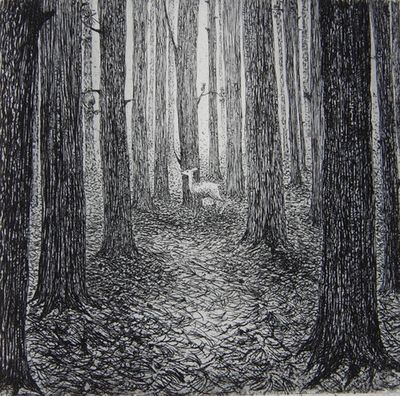

The art today is by Flora McLachlan, a printmaker born in Sussex and now based in Pembrokeshire, West Wales. "My pictures are records of things seen and imagined by twilight or moonglow," she writes. "I take inspiration from my studies of English literature, myth and legend. I try to express a sense of the enchantment I feel is embedded in our ancient landscape. I try to imagine the secret face of the land, when the light fades and the creatures come out to roam. I���m feeling for a lost or hidden magic, a glimpse through trees of the white hart.

"My preferred technique is etching. I love its atmosphere, the deep mysterious blacks and the glowing whites. During the long etching process, my original idea changes, and grows, with the working of the metal. The act of creation continues with the printing of the image; many of my etchings are underprinted with a painterly mono-collagraph plate, and most are complex and demand a concentrated and meditative approach to the inking and printing."

To see more of McLachlan's beautiful work visit the artist's website; and , her Etsy shop.

The passages quoted above are from Conversations with Barry Lopez: Walking the Path of Imagination by William E. Tydeman (University of Oklahoma Press, 2013). All rights to the words & images in this post reserved by the authors & artist. A related post: "On art, culture, and radical hope."

The passages quoted above are from Conversations with Barry Lopez: Walking the Path of Imagination by William E. Tydeman (University of Oklahoma Press, 2013). All rights to the words & images in this post reserved by the authors & artist. A related post: "On art, culture, and radical hope."

Tunes for a Monday Morning

We're sticking close to home today with music that is (mostly) from Devon, with photographs by James Ravilious (1939-1999), Devon's great chronicler of rural life.

Above: "Hold On" by Wildwood Kin, three young women from just up the road in Exeter. The group consists of two sisters, Beth and Emillie Key, and their cousin Meghann Loney. They have one four-track EP out so far, Salt of the Earth

Below: "Silver Threads Among the Gold," a beautiful paean to aging by Seth Lakeman, who lives on the other side of Dartmoor near Tavistock. He's back up by Wildwood Kin in this performance, filmed at The Convent in Stroud. The song is from Ballads of The Broken Few, due out in September.

Above: Seth Lakeman again, this time with the recording of "Blacksmith's Prayer" for Tales from the Barrelhouse, an album that explores the history and experience of country artisans in Devon and Cornwall.

Below: "Artisan," a gorgeous song about carpenters from the same album. This man is simply one of the finest songwriters working in Britain today.

And last, above: "The Carpenter" by Hannah James, a singer, accordion player and champion clog dancer from north-west England. Having collaborated with numerous folk musicians in the UK and abroad, she now performs in a duo with Sam Sweeney, in the Lady Maisery trio, and in her own innovative music & dance show JigDoll.

May 15, 2016

Tunes for a Monday Morning

We're sticking close to home for the music today, as all but the last song come from musicians raised here in Devon....

Above: "Hold On" by Wildwood Kin, three young women from just up the road in Exeter. The group consists of two sisters, Beth and Emillie Key, and their cousin Meghann Loney. They have one four-track EP out so far, Salt of the Earth

Below: "Silver Threads Among the Gold" by Seth Lakeman, backed here up Wildwood Kin at The Convent in Stroud last September. Lakeman lives just over the moor near Tavistock. The song will be on his next album, Ballads of The Broken Few, due out later this year.

Above: Seth Lakeman again, this time with the video for "A Blacksmith's Prayer" from Tales from the Barrelhouse, a gorgeous album that explores the history and experience of country artisans in Devon and Cornwall.

Below: "Artisan," a stripped down performance of his song about carpenters from the same album.

And last, above: "The Carpenter" by Hannah James, a singer, accordionist and champion clog dancer who performs in a duo with Sam Sweeney, in the Lady Maisery trio, and in her own innovative music & dance show JigDoll.

The photographs today are by the great Devon photographer James Ravilious (1939-1999).

May 13, 2016

Painting with language

From Conversations with Barry Lopez by William E. Tydeman:

"Artists and writers are constantly changing the sense of orthodoxy in perceived relations," says Lopez, "visual, accoustical, spacial, emotional relationships. All this work stimulates thinking. So, we know we are horizontally oriented, it just makes me more curious about the vertical dimension. As a writer, I always want to stimulate a sense of awareness. I want to create and intensify patterns. When I listen to music, I always hear patterns. When I'm walking in the woods, I sense patterns. Walking in the woods with somebody, I might identify a plant, but the naming of the plant comes out of a pattern of movement, the conjunction of the time of year with that particular space. For example, knowing that I'm coming off a ridge and down onto a south-facing slope in May, I'm going to be looking for certain plants that I'm not going to find on the north side.

"So I'm always looking for these patterns when I'm writing, though I'm not necessarily thinking about a pattern -- it's like I've caught it in a sidelong glance and, like a painter, I'm trying to render it. I'm making a pattern in language that stands in the place of a pattern I've seen or felt.

"But this kind of intelligence can also get in the way of a story," he adds. "I have to remind myself sometimes when I'm writing fiction that it's a good thing not to be thinking, because then I might be trying to make a point. Writing a short story to make a point seems vaguely contradictory to me. In fiction I don't want to make a point, I want to report a pattern I'm aware of, make it work in a dramatic narrative, and leave it at that, and trust that the reader encountering this pattern will be compelled to think about life differently."

Words: The passage quoted above is from Conversations with Barry Lopez: Walking the Path of Imagination by William E. Tydeman (University of Oklahoma Press, 2013). Please note that Lopez is talking about writing fiction here, as opposed to the different mindset one needs when writing nonfiction. The poem in the picture captions is from Heaven: Collected Poems 1956-1990 by Al Young (Creative Arts, 1992). All rights reserved.

Pictures: These photographs were taken earlier this week. Tilly had a small medical procedure yesterday and is now home and resting quietly. She'll be up and back into her beloved woods soon.

May 11, 2016

From the archives: Picking Nettles

In the fairy tale of "The Wild Swans" by Hans Christian Andersen, the heroine's brothers have been turned into swans by their evil stepmother. A kindly fairy instructs her to gather nettles in a  graveyard by night, spin their fibers into a prickly green yarn, and then knit the yarn into a coat for each swan brother in order to break the spell -- all of which she must do without speaking a word or her brothers will die. The nettles sting and blister her hands, but she plucks and cards, spins and knits, until the nettle coats are almost done -- running out of time before she can finish the sleeve on the very last coat. She flings the coats onto her swan-brothers and they transform back into young men -- except for the youngest, with the incomplete coat, who is left with a wing in the place of one arm. (And there begins a whole other tale.)

graveyard by night, spin their fibers into a prickly green yarn, and then knit the yarn into a coat for each swan brother in order to break the spell -- all of which she must do without speaking a word or her brothers will die. The nettles sting and blister her hands, but she plucks and cards, spins and knits, until the nettle coats are almost done -- running out of time before she can finish the sleeve on the very last coat. She flings the coats onto her swan-brothers and they transform back into young men -- except for the youngest, with the incomplete coat, who is left with a wing in the place of one arm. (And there begins a whole other tale.)

This was one of my favorite stories as a child, for I too had brothers in harm's way, and I too was a silent sister who worked as best I could to keep them safe, and sometimes succeded, and sometimes failed, as the plot of our lives unfolded. The story confirmed that courage can be as painful as knitting coats from nettles, but that goodness can still win out in the end. Spells can broken, and gentle, loving persistence can be the strongest magic of them all.

I grew up with the story, but not with Urtica dioica: "common nettles" or "stinging nettles." I imagined them as dark, thorny, and witchy-looking -- and although they're actually green and ordinary, growing thickly in fields and hedges here in Devon, nettles emerge nonetheless from the loam of old stories and glow with a fairy glamour. It is a plant that heralds the return of spring, a tonic of vitamins and minerals; and also a plant redolent of swans and spells, of love and loss and loyalty, of ancient powers skillfully knotted into the most traditional of women's arts: carding, spinning, knitting, and sewing.

According to the Anglo-Saxon "Nine Herbs Charm," recorded in the 10th century, sti��e (nettles) were used as a protection against "elf-shot" (mysterious pains in humans or livestock caused by the arrows of the elvin folk) and"flying venom" (believed at the time to be one of the four primary causes of illness). In Norse myth, nettles are associated with Thor, the god of Thunder; and with Loki, the trickster god, whose magical fishing net is made from them. In Celtic lore, thick stands of nettles indicate that there are fairy dwellings close by, and the sting of the nettle protects against fairy mischief, black magic, and other forms of sorcery.

Nettles once rivaled flax and hemp (and later, cotton) as a staple fiber for thread and yarn, used to make everything from heavy sailcloth to fine table linen up to the 17th/18th centuries. Other fibers proved more economical as the making of cloth became more mechanized, but in some areas (such as the highlands of Scotland) nettle cloth is still made to this day. "In Scotland, I have eaten nettles," said the 18th century poet Thomas Campbell, "I have slept in nettle sheets, and I have dined off a nettle tablecloth. The young and tender nettle is an excellent potherb. The stalks of the old nettle are as good as flax for making cloth. I have heard my mother say that she thought nettle cloth more durable than any other linen."

"Nettles have numerous virtues," writes Margaret Baker in Discovering the Folklore of Plants. "Nettle oil preceded paraffin; the juice curdled milk and helped to make Cheshire cheese; nettle juice seals leaky barrels; nettles drive frogs from beehives and flies from larders; nettle compost encourages ailing plants; and fruits packed in nettle leaves retain their bloom and freshness.

"Mixing medicine and magic, a healer could cure fever by pulling up a nettle by its roots while speaking the patient's name and those of his parents. Roman soldiers in damp Britain found that rheumatic joints responded to a beating with nettles. Tyroleans threw nettles on the fire to avert thunderstorms, and gathered nettle before sunrise to protect their cattle from evil spirits."

The medicinal value of nettles is confirmed by Julie Bruton-Seal & Matthew Seal in their useful book Hedgerow Medicine:

"Nettle was the Anglo-Saxon sacred herb wergula, and in medieval times nettle beer was drunk for rheumatism. Nettle's high vitamin C content made it a valuable spring tonic for our ancestors after a winter of living on grain and salted meat, with hardly any green vegetables. Nettle soup and porridge were popular spring tonic purifiers, but a pasta or pesto from the leaves is a worthily nutritious modern alternative. Nettle soup is described by one modern writer as 'Springtime herbalism at one of its finest moments.' This soup is the Scottish kail. Tibetans believe that their sage and poet Milarepa (AD 1052-1135) lived solely on nettle soup for many years until he himself turned green: a literal green man.

"Nettles enhance natural immunity, helping protect us from infections. Nettle tea drunk often at the start of a feverish illness is beneficial. Nettles have long been considered a blood tonic and are a wonderful treatment for anaemia, as they are high in both iron and chlorophyll. The iron in nettles is very easily absorbed and assimilated. What cooks will tell you is that two minutes of boiling nettle leaves will neutralize both the silica 'syringes' of the stinging cells and the histamine or formic acid-like solution that is so painful."

Nattadon Nettle Soup

Melt some butter in the bottom of the soup pot, add a chopped onion or two, and cook slowly until softened.

Add a litre or so of vegetable or chicken stock, with salt, pepper, and any herbs you fancy.

Add 2 large potatoes (chopped), a large carrot (chopped), and simmer until almost soft. If you like your soup thick, use more potatoes.

Throw in several large handfuls of fresh nettle tops, and simmer gently for another 10 minutes.

Add some cream (to taste), and a pinch of nutmeg.

Pur��e with a blender, and serve.

If you happen to have some truffle oil in your pantry, a light sprinkling on the soup tastes terrific.

And here are two more good nettle recipes: nettle pancakes and wild nettle bread.

Nettles, folk tales around the world agree, have long been associated with women's domestic magic: with inner strength and fortitude, with healing and also self-healing, with protection and also self-protection, with the ability to "enrich the soil" wherever we have been planted. Nettle magic is steeped in dualities: both fierce and soft, painful and restorative, common as weeds and priceless as jewels. Potent. Tenacious. Humble and often overlooked. Resilient.

And pretty tasty too.

The illustrations for "The Wild Swans" above are by Nadezhda Illarionova, Susan Jeffers, & Yvonne Gilbert. The Nettle Coat is by Alice Maher. Related posts: "Swan's Wing" and "The Folklore of Food."

The illustrations for "The Wild Swans" above are by Nadezhda Illarionova, Susan Jeffers, & Yvonne Gilbert. The Nettle Coat is by Alice Maher. Related posts: "Swan's Wing" and "The Folklore of Food."

On a misty morning in the Devon hills

"There exists a glamorized view of hardship and artistic achievement," notes the American writer Chris Offutt. "Young people who believe this can easily become self-destructive in their desire to 'suffer for their art.' They think they need hardship. But we all have hardship in our own way. Genuine suffering can lead to wisdom. It can also lead to despair and cruelty, drug addiction and violence. Artists are people who manage to take all this and turn it into something new. They make something. All artists excel for the same reasons: they are disciplined, diligent, and possess endurance.

"In order to develop artistic skill, you must have time to do so. Due to circumstances, some people simply don���t have the time and energy. Others who do, squander it."

Time and energy. The raw ingredients of art, for without them, inspiration and intention are ephemeral things. We all know people who squander their energy, time, and talent. And we all struggle not to be those people.

I am deeply grateful to have time to work, and for the circumstances, support, self-discipline and sheer luck that makes it possible. Energy, however, remains in short supply...or rather, my body is using its energy to heal and thus has only a little to spare for things it considers less vital. There is no arguing with the body. My work may be vastly important to me, but healing has its own priorities...and its requisition of the body's energy stores must not only be accepted, but respected.

So here is my prayer as I walk the hills, winding through the bluebells and bracken, led by a black-furred bundle of joy:

Let me not waste time and life on self-pity, kicking against physical disability. Let me use what energy I have wisely and well, working within the haiku of limitation -- crafting new work out of these materials. W orking with the life I have, and not against it.

"I write every day," says my wise friend Jane Yolen. "Every single day....Even if I am ill, traveling, caring for a sick husband, running around a convention, walking the Royal Mile -- even then I will manage to write something. Because being a writer means that kind of commitment. It doesn't have to be something for publication (though what does get published is almost always a surprise). It is something to get the brain, the heart, the imagination, and the fingers coordinated, working together. Not strangers but a good team.

"After my big back operation, part of my recovery was to walk a mile (or more) a day. As the amazing nurse Donna explained it to me: if you walk a mile at a good steady pace (mine is fast) outside, taking in the fresh oxygen, your spinal fluid moves up and down oiling the spine. Well, that's what writing every day does. It keeps the fluid moving about our brain, oiling its parts. Writing needs such fluidity.

"Yes, life happens," Jane continues. "It interrupts all our careful plans. A person from Porlock, an auto accident, a shooter in the movie theater, or more happily twins born, a friend stopping in for tea, your book winning the Caldecott, your editor calling to say you won the Nebula, your agent messaging that you sold a book, falling in love. But the bottomest of lines is this: if you are a writer, you write. And you turn all of life's hiccups into poetry or prose.

"How lucky are we -- accidents, incidents, handicaps, heartbreaks all become research, become prompts. So don't ignore them, but use them. Every day.

"Every single glorious, bloody day."

The quote by Chris Offut is from an interview in Salon magazine (March, 2016). The quote by Jane Yolen is from a post on her Facebook page (August, 2015). The poem in the picture captions is from Twelve Moons by Mary Oliver (Little, Brown, & Co., 1978). All rights reserved by the authors.

The quote by Chris Offut is from an interview in Salon magazine (March, 2016). The quote by Jane Yolen is from a post on her Facebook page (August, 2015). The poem in the picture captions is from Twelve Moons by Mary Oliver (Little, Brown, & Co., 1978). All rights reserved by the authors.

May 10, 2016

The genius of the community

In his fine book of conversations with writer & naturalist Barry Lopez, who has long been one of my guiding lights, William E. Tydeman quotes these words from a talk Lopez gave at Rice University in Houston, Texas in 2004:

"I have been puzzled and troubled all my life by the idea of individual genius. In my experience those who are most comfortable with this characterization are often the people who are least aware of how their work has benefited from the support of others. In my view they are always ready to accept full credit for the quality of an individual vision but are vaguely contemptuous of the idea that something they've made is not fully their own, that it is partly due to the way people support them and also to something unknown moving through them.

"We say Bach is a genius," Lopez continues. "But when Yo-Yo Ma finds two different interpretations of the Sixth Cello Suite, what is Ma? I don't mean to be academic here or to play games with concepts of originality or interpretation. I'm saying something much simpler, or, you might say, more naive. It is my view that individual genius is a gift, that the gifted personality is a manifestation of a kind of genius that belongs, finally, to the community. The genius is in us.

"In ensemble art, the theater, dance, the music of the quartet, the trio, the orchestra, it is easy to see that one person is not responsible. It's harder with painting, photography, or writing. Why pursue this distinction? Because in a celebrity-driven culture like ours, claims to originality and genius seem curiously misplaced. Historically, humanity has more often benefited from the genius of the community than from the genius of the individual. And people with no faith in their own wisdom in hard times have perished waiting for a genuis to appear and lead them.

"I believe in the singular vision of the individual artist," Lopez makes clear. "If I am honest, I would have to say I accept the artist's occasional disregard for community, the neglect of spouse, of children and parents, that this obsession sometimes entails. But there is a line here. What does the community gain by your work and what does it lose?

"The line I draw for myself is, I know, subjective and probably inconsistent. What is more on my mind these days about this though...is this. If humanity is [ecologically] imperiled, shouldn't our investment in the work of artists include more than it does? Shouldn't we be underwriting collaboration and cooperation? If, as the poet Robert Duncan has said, 'The drama of our time is the coming of all men into one fate,' shouldn't we be thinking more about a wisdom revealed in the mounting of one communal voice...?

"In some strange way," Lopez concludes, "I think we are at a cultural crossroads today where the primacy of the individual is concerned. If we are endangered as a culture, do we need to ask ourselves what price society pays for our vigorous support of individual visions? I don't know. I do not really worry about what other people are doing. In my own life, however, I am suspicious of this idea, the primacy of the individual, despite my Enlightenment upbringing. So, I am trying to explore the disquieting dimensions of my own ego."

The passage quoted above is from the introduction to Conversations with Barry Lopez: Walking the Path of Imagination by William E. Tydeman (University of Oklahoma Press, 2013), which I highly recommend. The poem in the picture captions is from David Whyte's What to Remember When Waking (Sounds True, 2010). All rights reserved by the authors. Related posts: On the Care & Feeding of Daemons & Muses, Gift Exchange, and Knowing the World as a Gift.

The passage quoted above is from the introduction to Conversations with Barry Lopez: Walking the Path of Imagination by William E. Tydeman (University of Oklahoma Press, 2013), which I highly recommend. The poem in the picture captions is from David Whyte's What to Remember When Waking (Sounds True, 2010). All rights reserved by the authors. Related posts: On the Care & Feeding of Daemons & Muses, Gift Exchange, and Knowing the World as a Gift.

May 9, 2016

Event Announcements for a Monday Evening

I can't remember if I mentioned this before, but since it's coming up soon I'll do so again:

If you're anywhere near Oxford, UK this month, I will be delivering the 4th Annual Tolkien Lecture at Pembroke College, Oxford University, on May 26th (6:30 pm). The Pembroke Fantasy lecture series "explores the history and current state of fantasy literature, in honour of JRR Tolkien, who wrote The Hobbit and much of The Lord of the Rings during his twenty years at the college."

As if it wasn't daunting enough to speak about fantasy at Professor Tolkien's old college, last year's speaker was the wonderful Lev Grossman, with Philip Pullman scheduled for 2017. What an erudite pair to be squeezed between! Please come if you can; it would be lovely to have some folks from the Myth & Moor community there. Admission is free, but you need to register for a ticket and space is limited. Go here for further details.

While I'm on the subject of public events, the Green Hill Arts Centre (here in Devon, in nearby Moretonhampstead) is hosting a second Widdershins exhibition of Dartmoor mythic art, running June 25th to August 27th. Participating artists include Brian Froud, Wendy Froud, Alan Lee, Marja Lee, Virginia Lee, Danielle Barlow, Angharad Barlow, Rima Staines, Hazel Brown, Paul Kidby, me, and I think one or two other folks as well...I'll let you know when I've got the complete list.

Like the first Widdershins in 2013, there will be talks, workshops and other mythic events surrounding the exhibition -- but the full schedule hasn't been finalized yet. This is just a heads-up to let you know that the show is happening; I'll post the full schedule of events when it goes live, and I hope some of you can come.

May 8, 2016

Tunes for a Monday Morning

Yesterday was World Accordion Day, so our music this week features four fine squeezebox players working in the English/Irish/Scottish folk tradition.

Above, the great button accordian player Sharon Shannon (from County Clare, Ireland) performs "Blackbird: Padraig O'Keefe's/The Happy One-Step" with multi-instrumentalist Alan Connor at the Celtic Colours International Festival, Cape Breton Island (2014). Shannon has released many excellent albums over the last twenty years, the latest of which is In Galway, in collaboration with Connor (2015).

Below, "Northern Lass/The Kings' Barrow" by Leveret, a trio of English folk music stalwarts based in Derby and Stroud. Andy Cutting plays the melodeon here, with Sam Sweeney on fiddle and Rob Harbron on concertina. The song can be found on Leveret's first album, New Anything (2015).

Above, "Save the Bees" from Lau, an English & Scottish folk trio named after the Orcadian word for "natural light." Martin Green plays piano accordion, with Kris Drever on guitar and Aidan O'Rourke on fiddle. The song is from their third album, Race The Loser (2012).

Last, "Beads & Feathers" by Sea Road Sessions. That's Alan Kelly on piano accordion, with Kris Drever again on vocals & guitar, plus Steph Geremia (vocals & flute), ��amonn Coyne (banjo), Ian David Carr (guitar), and Staffan Lindfors (bass). The song was filmed during the sound check before the band's appearance at Celtic Connections in Glasgow, 2015.

Photographs: A button accordion player in an old French postcard, and paper art by Peter & Donna Thomas.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 708 followers