Terri Windling's Blog, page 119

February 23, 2016

The right books at the right time

Here's another passage from The Pleasure of Reading on the importance "place" in a child's imagination -- in this case, not the place where the child actually lives, but the worlds conjured by a writer's words:

"Oh, the excitement of the latest Famous Five adventure," playright Ronald Harwood reminisces, "with Biggles, Just William, Huckleberry Finn, Tom Sawyer and Long John Silver following close behind. I have not, except for Treasure Island, re-read them since childhood or adolescence and I've made it a condition not to re-read them now in case I am embarrassed by memory. I want to prevent the pompous adult, sensitive to what others may think, from inhibiting the impressionable child. I was, by the way, a late developer and only began reading intelligently when I was twenty.

"Oh, the excitement of the latest Famous Five adventure," playright Ronald Harwood reminisces, "with Biggles, Just William, Huckleberry Finn, Tom Sawyer and Long John Silver following close behind. I have not, except for Treasure Island, re-read them since childhood or adolescence and I've made it a condition not to re-read them now in case I am embarrassed by memory. I want to prevent the pompous adult, sensitive to what others may think, from inhibiting the impressionable child. I was, by the way, a late developer and only began reading intelligently when I was twenty.

"I should explain I was born and educated in Cape Town but my mother, born in London, led me to believe from an early age that England was the Promised Land and London Jerusalem so I was a good deal drawn to books which fed my hunger for Englishness, defined by me then, and now, as an ideal of gentleness, culture, countryside and justice.

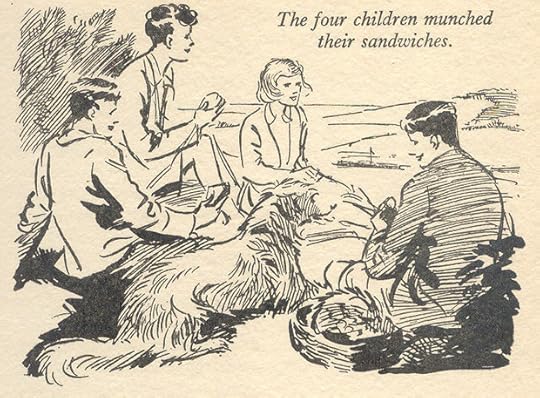

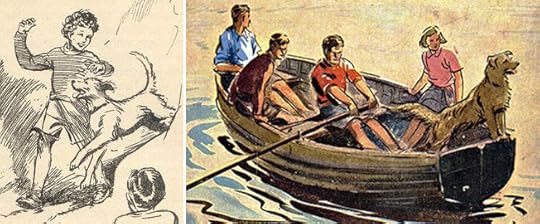

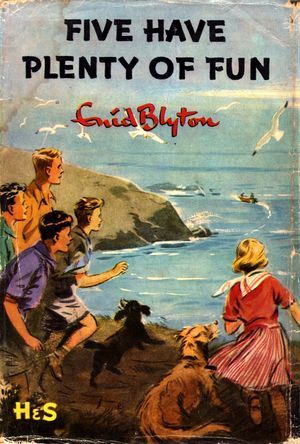

"Enid Blyton, more than any other writer I remember, fulfilled much of that definition, those longings for England, but only in her Famous Five stories. (I could not abide Noddy or any of the others.) The Famous Five, as I remember, lived somewhere in the south of England -- Kent, I think -- and were amateur detectives who, in their summer holidays, stumbled on crimes and solved them just as it was time to go back to school. Gentle justice triumphed.

"But it was her ability to share her love of the English landscape which was, to me, her most endearing quality," Harwood continues. "Enid Blyton described the rural scene so vividly that I carry to this day what I believe to be her images of tree-tunnels and green hillsides and well-kept careless gardens. I am told now it was a sugary, middle-class idyll she created (a criticism as meaningless to me now as it would have been then), romantic, idealized, nostalgic.

"The fascinating aspect of her power, however, is that when, many years later, I went to live in a Hampshire village and walked the footpaths and climbed the hangers, my memory was jolted by her descriptions of the England in which the capers of the Famous Five took place and seemed to me accurate. I cannot say she influenced my own writing but as a reader I owe her an enormous debt; and I remember in the 1970s, when censorship was virulent in England, how shocked I was to read of librarians removing Enid Blyton from their shelves for being too middle-class or too twee or too something. They could not have known that to one immigrant, at least, she described a magical world....

"I am beginning to understand that the books I read as a child subtly define the adult."

Doris Lessing lived in Iran until she was five, then spent the rest of her childhood on a farm in South Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe).

"I began reading at seven, off a cigarette pack," she recalls, before progressing to the books on her English-born parents' shelves. "The books I responded to then are not those I would  chose as best now. You have to read a book at the right time for you, and I'm sure this cannot be insisted on too often, for it is the key to the enjoyment of literature.

chose as best now. You have to read a book at the right time for you, and I'm sure this cannot be insisted on too often, for it is the key to the enjoyment of literature.

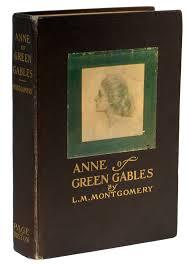

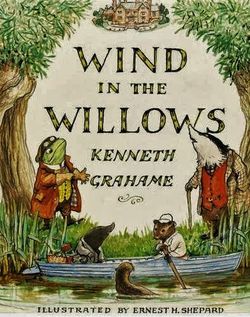

"I read children's books, some unknown to today's children. The [North] Americans: L.M. Montgomery's Anne of Green Gables books, Susan Coolidge's What Katy Did series, The Girl of Limberlost by Gene Stratton Porter and its sequels. Louisa Alcott. Hawthorne. Henty. The English classics were Lewis Carroll, who I like better now than I did then, and Milne's Winnie the Pooh, which I adored then and feel uneasy about now. The hero is a stupid greedy little bear, and the clever animals are ridiculous: good old England, I sometimes think, at it again. But there was Kenneth Grahame's  The Wind in the Willows,

The Wind in the Willows,

and a wonderful children's newspaper, and a magazine called The Merry-Go-Round that printed Walter de la Mare, Eleanor Farjeon, Lawrence Binyon, and other fine writers. Walter de la Mare's The Three Royal Monkeys entranced me then, and still kept some of its magic about it when I recently re-read it.

"I was lucky that my parents read to my brother and me. I believe that nothing has the impact of a story read or told. I remember the atmosphere of those evenings, and all the stories, some of them long-running domestic epics made up by my mother, about the adventures of mice, or our cats and dogs, or the little monkeys that lived around us in the bush and sometimes leaped about in the rafters under the thatch, or the interaction between our domestic animals and the wild ones all around us....Parents who read to their children or who make up stories are giving them the finest gift in the world. Do we too often forget that tale-telling is thousands of years old, whereas we have been reading for a trifling number of centuries?"

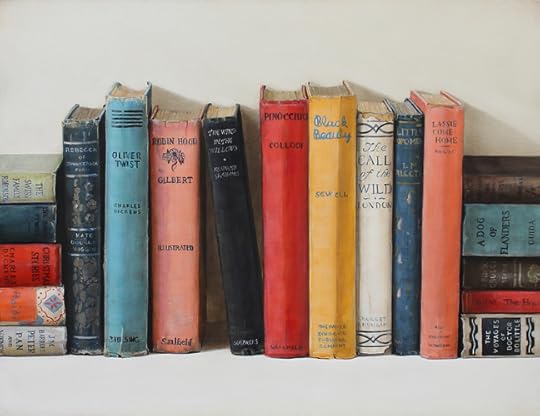

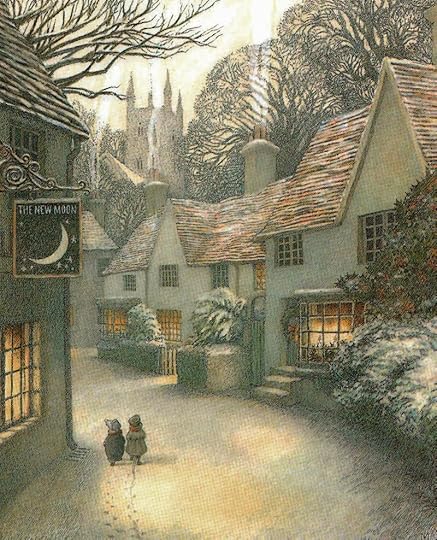

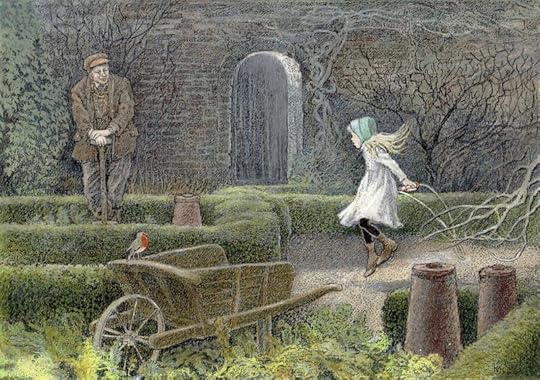

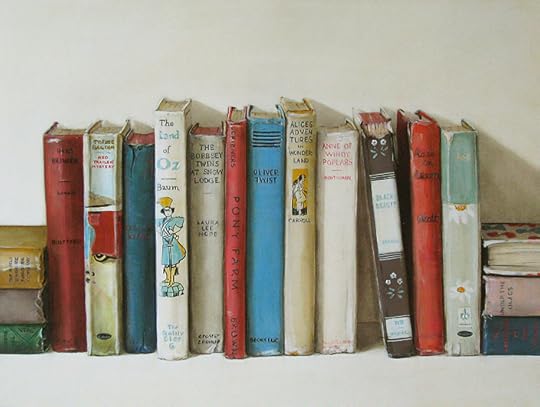

Pictures: The wonderful still life paintings at the top and bottom of this post are by Canadian artist Holly Farrell. The Famous Five illustrations are by Eileen Soper (1905-1990). The first edition of Anne of Green Gables was illustrated by M. A. & W. A. J. Claus (1914). The cover design for The Girl of Limberlost is by Wladyslaw T. Benda, the illustrator of What Katy Did is uncredited, and the cover illustration for Little Women is by C.M. Burd. Words: The passages by Ronald Harwood and Doris Lessing above are from Reading for Pleasure, edited by Antonia Fraser (Bloomsbury, 1992). All rights reserved by the authors, artists, or their estates.

Pictures: The wonderful still life paintings at the top and bottom of this post are by Canadian artist Holly Farrell. The Famous Five illustrations are by Eileen Soper (1905-1990). The first edition of Anne of Green Gables was illustrated by M. A. & W. A. J. Claus (1914). The cover design for The Girl of Limberlost is by Wladyslaw T. Benda, the illustrator of What Katy Did is uncredited, and the cover illustration for Little Women is by C.M. Burd. Words: The passages by Ronald Harwood and Doris Lessing above are from Reading for Pleasure, edited by Antonia Fraser (Bloomsbury, 1992). All rights reserved by the authors, artists, or their estates.

Reading and place

"Reading for me is inextricably tied to place," writes Scottish author Emma Tennant about the books she favored in childhood. It's my favorite of the charming essays to be found in Antonia Fraser's The Pleasures of Reading, for Tennant grew up in a house that seems to have emerged from a novel by Elizabeth Goudge, built by her great-grandfather:

"The Victorian Gothic house -- a 'monstrosity' to some, a 'folly' to others -- to all a decidedly odd place for a person to spend their formative years, cast its long shadow over the books I read. For years no book I read came from anywhere but the bowels and lungs -- and in some cases the twisted attics -- of the Big House that crouched at the end of a valley still then clad with the last shreds of the Ettick Forest. I read up and down the house, and I knew fairly early on that I would never begin to get through it all -- even with the help of the terrifying Demonologie, property of James IV of Scotland, with its turning paper wheels to aid with the casting of spells.

"To begin with that ragged line of Ettrick silver birches outside my window. This was the Fethan wood, where James Hogg set fairy tales and metamorphoses: it was dangerous to walk there, to go up to the ring of bright grass and look down at the house through silver-grey trees. People came out transformed into animals -- or didn't come out at all, to be discovered years later as three-legged stools. I read the Hogg stories -- or they were read to me -- and years before I was able to go on to his great masterpiece, The Confessions of a Justified Sinner, the account of a man driven insane by Calvinism, by the dictates of the devil who sends him out to kill as one of the Elect -- I could feel the power of Hogg's imagination in the hills and woods and streams that enclosed the house.

"The house could be said to be like an archaeological dig, with the basement providing material contemporaneous with the discoveries of archeologists Arthur Evans or Heinrich Schliemann, and just as startling for a child to discover as it must have been for the archaeologists to unearth the foundations of Knossos or Clytemnestra's tomb. Here were Henty and Ballantyne -- and, most important of all, H. Rider Haggard's She -- all in low rooms hard to find in a labyrinth of tiled passages, cold with a strong smell of rot. Here the strong and brave of the Empire fought their battles and had their impossible adventures; and here I lingered, in disused dairies and stillrooms, reading in a world which was a dusty monument to that vanished and glorious past.

"From the crepuscular vaults of the house there were two ways up. The back stairs led to the schoolrooms, where tubercular daughters had coughed over books of such spectacular dullness that I remember none of them -- except for the fact that some more recent incumbents had left a stash of historical romances by Margaret Irwin and Violet Needham. Here, in the abandoned schoolroom, I was drawn into a past (there were a couple of Georgette Heyers too) of phaetons and darkly scowling artistocrats and games of faro and the like, and for a while I stopped there, until the discovery of Alexander Dumas' The Back Tulip drew me down the stairs again and out into the garden. For the magnetic quality of that extraordinary book led me to search the grassy paths and flower borders for the elusive tulip -- and once I thought I saw it between two yew trees, at the entrance to the garden: a rich, gleaming black flower that would guide me somehow down the paths my own imagination was just beginning to try....

"The attic had books in trunks that had split open with age -- books no-one wanted when they went off to war, or went off to get married, or had no room for anyway. Bees had once swarmed in the attic, and it's to the smell of wax that I remember finding the early Penguins: the Aldous Huxleys, a book called A Month of Sundays, which I have never since been able to trace -- and the odd Agatha Christie, which kept me up there until dark, amongst children's wicker saddles, pictures of dead aunts that no-one would ever want to look at, and a floor covering of dead bees."

As an American child growing up in a series of unromantic mid-20th century houses, I longed for a Gothic pile like Tennant's, with rooms to explore and books to discover and pathways leading to fairy tale woods. It wasn't until I was grown that I finally lived in house full of history and ghosts: a  little stone cottage, 400 years old, that I owned for two decades before I was married. That's a story for another day, however, as that was a place that shaped my adult self, not the child I was and thus the writer and painter I became.

little stone cottage, 400 years old, that I owned for two decades before I was married. That's a story for another day, however, as that was a place that shaped my adult self, not the child I was and thus the writer and painter I became.

What houses did you love in childhood? Or long for? Or perhaps still inhabit today? We've been talking about place and home this last week, and the houses in which our childhoods unfolded surely shaped our creative psyches as much as the land or cityscape around them. For me, tossed back and forth between the houses of various relatives, with occasional stints in foster care, the transient aspect of those years created the theme of "finding home, place, and family" that runs (whether I consciously mean it to or not) through all of work.

Despite having no single place that was my home, I also associate the books I loved in childhood with places where I first read them, as Emma Tennant does in the passage above. Re-reading those books takes me right back, a potent form of time-traveling indeed.

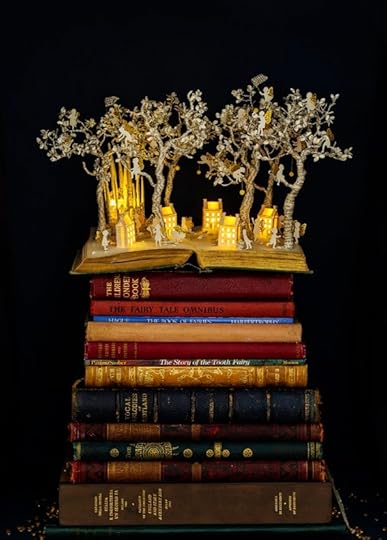

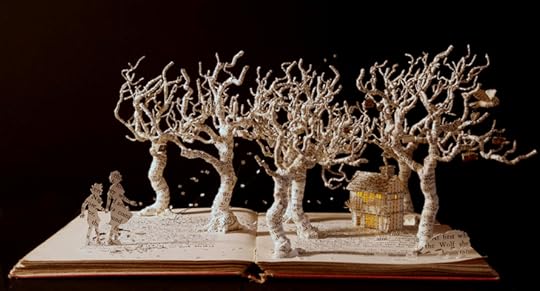

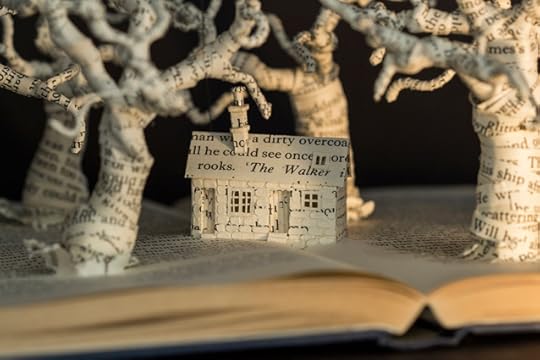

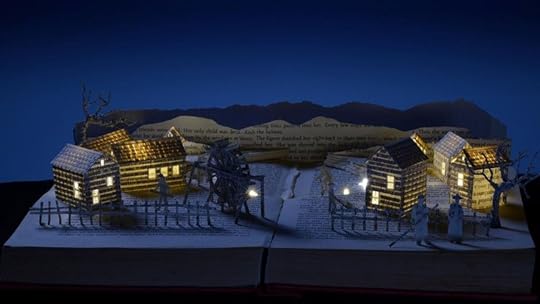

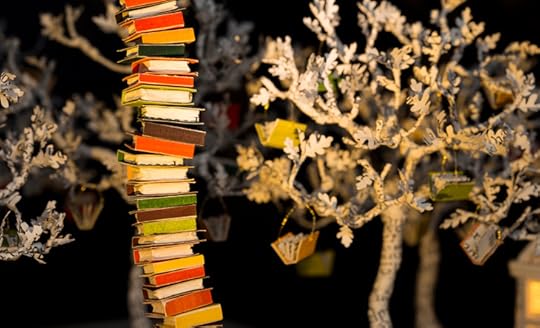

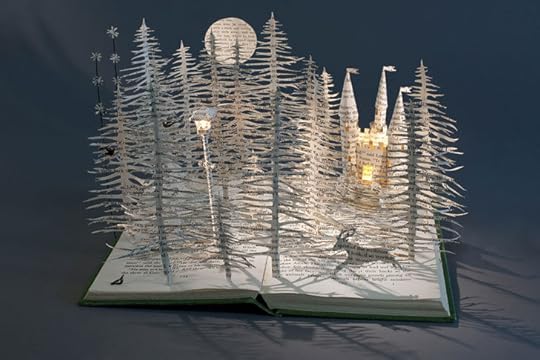

The art today is, of course, by the great British papercut artist Su Blackwell, most of it created in the last year.

���I often work within the realm of fairy-tales and folk-lore,"she says. "I began making a series of book-sculpture, cutting-out images from old books to create three-dimensional dioramas, and displaying them inside wooden boxes. For the cut-out illustrations, I tend to lean towards young-girl characters, placing them in haunting, fragile settings, expressing the vulnerability of childhood, while also conveying a sense of childhood anxiety and wonder. There is a quiet melancholy in the work, depicted in the material used, and choice of subtle colour."

Visit the Blackwell's website to see her utterly amazing book sculptures and installations, and go here to see a video in which the artist discusses her creative process. She also has three lovely books out: The Fairytale Princess (with Wendy Jones), Sleeping Beauty Theatre (with Corina Fletcher), and Su Blackwell Book Sculptures.

The passage by Emma Tennant above is from The Pleasures of Reading, edited by Antonia Fraser (Bloomsbury, 1992). I recommend reading this delightful essay in full. All rights to the text and art above reserved by the author and artist.

The passage by Emma Tennant above is from The Pleasures of Reading, edited by Antonia Fraser (Bloomsbury, 1992). I recommend reading this delightful essay in full. All rights to the text and art above reserved by the author and artist.

February 21, 2016

Tunes for a Monday Morning

Today, music from the Songs of Separation project: the brainchild of folk musician Jenny Hill, conceived during the contentious run-up to the referendum for Scottish independence. Hill's idea was to bring ten English and Scottish women folk musicians to a fairy tale island off Scotland's west coast to create an album reflecting on "separation" in its many forms.

"Celebrating the similarities and differences in our musical, linguistic and cultural heritage," she writes, "and set in the context of a post-referendum world, the work aims to evoke emotional responses and prompt new thinking about the issue of separation as it occurs in all our lives. The collected songs aim to get to the heart of what we feel when we are faced with a separation, both good and bad."

The musicians (along with Jen Hill) are: Hazel Askew, Jenn Butterworth, Eliza Carthy, Hannah James, Mary Macmaster, Karine Polwart, Hannah Read, Rowan Rheingans, and Kate Young. They spent an intensive week planning, rehearsing, and recording the album on Isle of Eigg in June 2015 -- including recordings made at the two sites central to the ���Big Women of Eigg��� legend.

Above: A short video on the making of Songs of Separation.

Below: An even shorter video from project's video diary, documenting a group sing, in Gaelic, with the Isle of Eigg community. (You can view the other "Daily Reflection" videos on the project's YouTube channel.)

Next, two songs from the album itself.

Above: "Echo Mocks the Corncrake," featuring Karine Polwart. As Helen Gregory notes in her review of the album, this traditional song "contains subtle political content and references to at least two forms of separation, even though it���s often thought of as a simple love song. The lyric tells of a young man whose partner leaves him for the bright lights of Ayr (located on 'the banks o��� Doune'), an act of separation which is one manifestation of the rural depopulation occurring as a result of the impact of the spread of industrialisation during the 18th and 19th centuries, further exacerbated in Scotland by the greed-fuelled brutality of the Highland Clearances. And the corncrake? The subject of the separation of humankind from the natural environment is key: habitat loss has meant that the numbers of this migratory bird have declined across the British Isles since the mid-19th century. Consequently, corncrakes are now restricted to Ireland and the northern and western islands of Scotland including, of course, the Isle of Eigg. So it���s fitting that 'Echo Mocks The Corncrake��� opens with a field recording of the bird���s distinctive krek krek call which sets the rhythm of the piece, picked up by percussive beats on a variety of instruments ahead of Karine���s vocals."

Below: "It was A' for our Rightfu' King," written by Robert Burns in the 18th century, arranged here by Hannah Read. "The song is inspired by the failed Jacobite uprising of 1745, lead by Prince Charles Edward Stuart (1720 - 1788)," explains Pauline MacKay. "The Jacobites sought to restore the deposed Stuart dynasty to the Scottish and English throne. The Jacobites were defeated at the battle of Culloden in 1746, forcing Bonnie Prince Charlie to flee to the highlands. He eventually reached Europe where he died in exile (in Rome). In this song a young woman laments the failure of the uprising and her Jacobite lover's absence from Scotland."

To learn more about the project, visit the Songs of Separation website or Facebook page. The album itself has just been released, and it's a beauty. There's also a concert tour in the works -- but if you can't make it to any of the tour locations, perhaps you'd like to help someone else attend through a random act of musical kindness. (I'm assuming they'll continue to run the "Save Our Seats" program for other venues on the tour, though it's not listed on the website yet.)

February 17, 2016

Recommended Reading

I'm away until Monday morning. In the meantime, here's a round-up of recommended reading:

"Fantasy North" by E.R. Truitt (Aeon)

"Susan Cooper, The Dark is Rising" by Rob Maslen (The City of Lost Books)

"Angela Carter, The Magic Toyshop" by Rob Maslen (The City of Lost Books)

"Stella Benson, Living Alone" by Rob Maslen (The City of Lost Books)

"Design for Living: Goethe" by Adam Kirsch (The New Yorker)

The history of the Twa Sisters ballad by Natalie Zarrelli (Atlas Obscura)

"Mushrooms in Wonderland" by Mike Jay (Mikejay.net)

"Real Witches See Possibilities" by Asia (Woolgathering & Wildcrafting)

"Dancing the Cailleach" by Carlotte Du Cann (The Dark Mountain Project)

"The Weathered Woman" by Sarah Elwell (Between the Woods & the Waters)

"Riding the Wind" by Karen Emslie (Aeon)

"Connecting with Nature Through Wildlife, Place, and Memory" by John Aitchison (The Ecologist)

"Trees Have Social Networks Too" by Sally McGrane (New York Times)

"Crows Understand Analogies" by Leyre Castro & Ed Wasserman (Scientific American)

"Deep Intellect" by Sy Montgomery (Orion Magazine)

"Go Tell the Bees" by Karen Maitland (The History Girls)

"Feel the Buzz: The Album Recorded by 40,000 Bees" by Tim Jonze (The Guardian)

"On Liberty, Reading, and Dissent" by Shami Chakrabarti (The Reading Agency)

"Dark Books" by Tara Isabella Burton (Aeon)

"Why the British Tell Better Children's Stories" by Colleen Gillard (The Atlantic)

"Books Writers Want to Dissect" by Shana DuBois (SF Signal)

"In the Mid-Midwinter" by Liz Lochhead (Scottish Poetry Library)

"Negotiations" by Rae Armantrout (Poets.org)

"Questions to Ask Yourself Before Giving Up" by Kaitlyn Boulding (Guts)

And recommended viewing:

"The Life of Death," a hand-drawn animated video by Marsha Onderstijn (Vimeo)

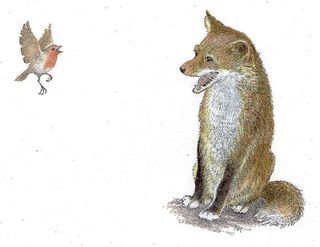

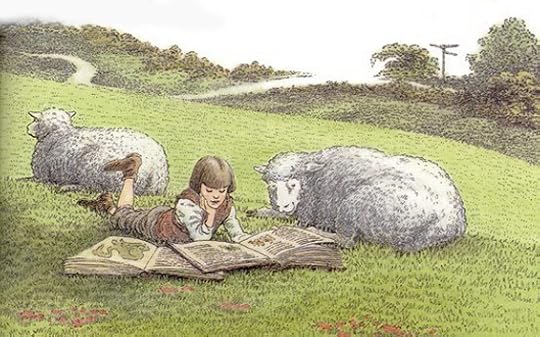

The illustration above is by Inga Moore.

On loss and transfiguration

"The classic makers of children's literature," writes Alison Lurie, "are not usually men and women who had consistently happy childhoods -- or even consistently unhappy ones. Rather they are those whose early happiness ended suddenly and often disastrously. Characteristically, they lost one or both parents early. They were abruptly shunted from one home to another, like Louisa May Alcott, Kenneth Grahame, and Mark Twain -- or even, like Frances Hodgson Burnett, E. Nesbit, and J.R.R. Tolkien, from one country to another. L. Frank Baum and Lewis Carroll were sent away to harsh and bullying schools; Rudyard Kipling was taken from India to England by his affectionate but ill-advised parents and left in the care of stupid and brutal strangers. Cheated of their full share of childhood, these men and women later re-created, and transfigured, their lost worlds. "

J.M Barrie falls into this catagory, the happiness of his early childhood vanishing into darkness and gloom when an elder brother, the family favorite, died in a skating accident, after which Barrie's mother retreated permanently to her bed. C.S. Lewis was ten when he lost his mother to cancer (and just four when his beloved dog, Jacksie, was killed by a car -- a loss that so effected him that he insisted upon being called Jack for the rest of his life). George MacDonald lost his mother to tuberculosis at the age of eight. Enid Blyton's happy childhood in Kent ended  abruptly when her beloved father left the family for another woman, leaving Enid behind with a mother who disapproved of her interest in nature, literature, and art.

abruptly when her beloved father left the family for another woman, leaving Enid behind with a mother who disapproved of her interest in nature, literature, and art.

The sudden loss of a happier childhood world doesn't turn everyone into a children's book writer, of course, but it's interesting to note how many fine writers' backgrounds are marked by such loss; and Lurie may be correct that the desire to re-create the lost world lies at the heart of a particular form of creative inspiration. Or perhaps I'm just struck by Lurie's idea because it maps onto my own childhood, which was, from a child's point of view, sunny and stable for the first six years when I lived in my grandmother's household (with my teenage mother and her sisters), and then plunged into darkness upon my mother's marriage to a brutal man, a stranger to me until the day of the wedding. Loss of home at a tender age can indeed send an unhappy child inward, seeking lands in imagination uncorrupted by the treacherous adult world.

In Friday's post, and yesterday's, we've been talking about concepts of home, place, connection to the landscape, and the way these things impact creative work. Today I'd like to come at the subject from a slightly different direction, with the idea that loss of home can be as powerful a creative spur as the finding of the heart's home, or the love of a long-established one.

Loss can come about in so many different ways, and needn't be dramatic to causing lasting trauma. I'm thinking, for example, of a loss all too common today in our over-populated world: the loss of treasured chilhood landscapes to the unchecked sprawl of cities and suburbs, of beloved old houses and places we can never return to, buried under shopping malls and parking lots.

In her essay collection Language and Longing, Carolyn Servid writes poignantly of her husband's childhood in an isolated valley in the mountains of Colorado. Lightly populated by old ranching families, artists and hermits, the valley was a sanctuary for humans and animals alike...until the development of the nearby  town of Aspen into a ski resort and playground for the wealthy began to raise property prices on Aspen's periphery. When the dirt road into the valley was paved, change was not long behind: land speculation, housing developments, a golf course. The valley as generations had known and loved it was gone.

town of Aspen into a ski resort and playground for the wealthy began to raise property prices on Aspen's periphery. When the dirt road into the valley was paved, change was not long behind: land speculation, housing developments, a golf course. The valley as generations had known and loved it was gone.

Servid writes that her husband "had witnessed this gradual transformation during summers home from college. He witnessed more changes every time he visited after marriage and various jobs took him out of the valley. He chronicled those changes to me before he ever drove me up the Crystal River Road to the Redstone house. The landscape stunned me the first time I saw it, and I watched it bring a deep smile of recognition to Dorik's eyes, but I knew his memories were of a wholeness that was no longer there. I realized he held a kind of perspective and knowledge that has been lost over and over again in the settlement of the continent, over and over again in the civilzation of the world."

A little later, he learns that a neighbor's ranch has been sold off to a developer. "I watched his face tighten," Servid writes, "and knew that a deepening ache was filling him. Places and people he loved were both caught in the wake of rampant development that grew like a cancer. The impact was like a diagnosis of the disease itself, as though one of the most fundamental aspects of his life was being eaten away. I wondered then about the grief that comes to us when we lose the places we love. This grief doesn't have much standing among the range of emotions that our society values. We have yet to fully acknowledge and accept just how much our hearts are entwined with the places that shape us, tolerate us, hold us, provide for us. We have yet to openly testify and accede to the necessity of such places and love of them in our daily lives. We have yet to fully understand that our links as people living together in communties will never be more than transient and vulnerable without rootedness in the place itself."

Just as Servid wonders "about the grief that comes to us when we lose the places we love," I wonder about the ways such a loss impacts us as writers and artists. Grief is a powerful thing, and especially so when it rumbles away, unexpressed, in the depth of our souls, the quiet but constant base note of our lives. Grief for landscapes paved over, ways of life that are gone, for whole species that are rapidly vanishing around us. Grief can indeed be a spur to art, leading us to "re-create or transfigure" our cherished lost worlds, or it can do the reverse: deaden and silence and paralyze us.

Your thoughts?

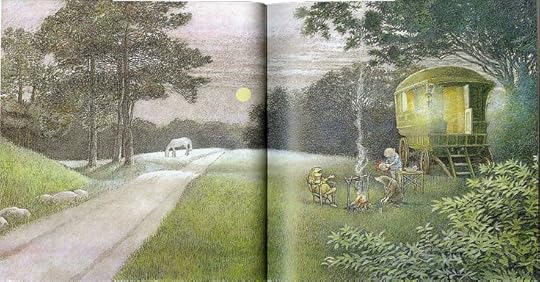

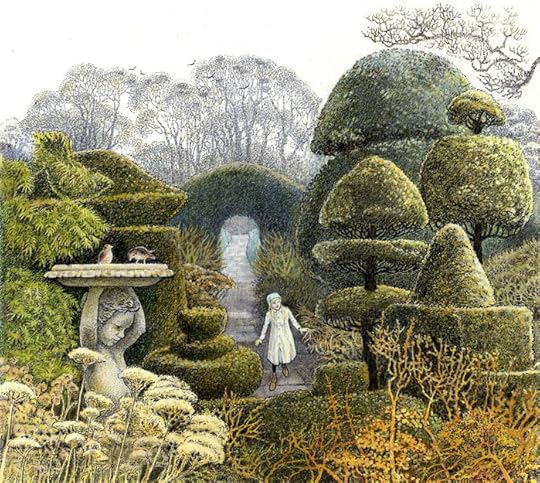

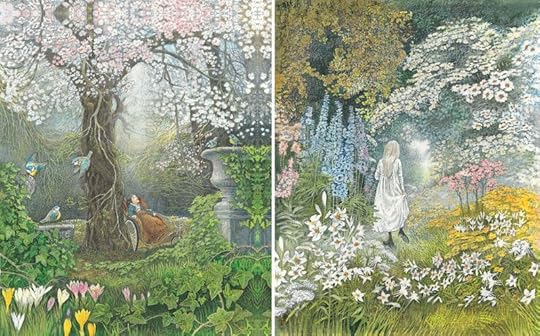

The beautiful art today is by Inga Moore, who was born in Sussex, raised in Australia (from the age of eight), and returned to England when she reached adulthood. Joanna Carey, in her lovely portrait of the artist, writes:

"An imaginative, somewhat subversive child, she drew constantly, illustrating not just her own stories but also her schoolbooks, her homework, tests and exam papers. 'If you'd only stop all this silly drawing,' said the Latin teacher, 'you might one day amount to something.' She did stop -- 'for a long time' -- and is still resentful about that teacher's attitude. She regrets not going to art school, and endured 'one boring job after another' before eventually getting back to the drawing board. Supporting herself making maps for a groundwater company, she embarked on a series of landscapes and happily rediscovered her passion for drawing."

"An imaginative, somewhat subversive child, she drew constantly, illustrating not just her own stories but also her schoolbooks, her homework, tests and exam papers. 'If you'd only stop all this silly drawing,' said the Latin teacher, 'you might one day amount to something.' She did stop -- 'for a long time' -- and is still resentful about that teacher's attitude. She regrets not going to art school, and endured 'one boring job after another' before eventually getting back to the drawing board. Supporting herself making maps for a groundwater company, she embarked on a series of landscapes and happily rediscovered her passion for drawing."

Moore worked as an illustrator in London until the economic downturn caused her to lose her home there -- a fortunate loss, as it turns out. She relocated to the Gloucester countryside, discovered this corner of England to be her heart's home, and produced the remarkable illustrations for The Wind in the Willows and The Secret Garden for which she is now justly famed. The pictures above are from those two volumes; the picture below is from The Reluctant Dragon.

The passage by Alison Lurie is from Don't Tell the Grown-ups: Subversive Children's Literature (Little, Brown Publishers, 1990). The passage by Carolyn Servid is from Of Language and Longing: Finding a Home at the Water's Edge (Milkweed Editions, 2000). The quote by Joanna Carey is from "Inga Moore, illustrator of The Wind in the Willows" ( The Guardian, Feburary 6, 2010). All rights to the text and art above reserved by their creators.

The passage by Alison Lurie is from Don't Tell the Grown-ups: Subversive Children's Literature (Little, Brown Publishers, 1990). The passage by Carolyn Servid is from Of Language and Longing: Finding a Home at the Water's Edge (Milkweed Editions, 2000). The quote by Joanna Carey is from "Inga Moore, illustrator of The Wind in the Willows" ( The Guardian, Feburary 6, 2010). All rights to the text and art above reserved by their creators.

February 16, 2016

Lines for winter

In quite a number of previous posts, I've quoted a range of writers on the value of rooting ourselves in the land on which we live -- of learning its flora, fauna, and folktales, and becoming part of a local community that encompasses human and animal neighbors alike. I mark these passages because they resonate with the life and art I am creating now, rooted on a quiet hillside in Devon. But there are, of course, other ways to experience a deep connection with magical world we live in, and so today I offer a passage presenting an alternative view.

In her beautiful little volume Writing the Sacred Into the Real, American poet and essayist Alison Hawthorne Deming notes that while geography is a touchstone for her imagination, this is not confined to geography of the state where she makes her home. Travel, she writes, is also a spur to keener attention and intimacy with place:

"Touchstone is a word used almost exclusively these days for its metaphoric meaning -- a thing which serves to test the genuiness or value of anything. The origin of this definition is mineral -- a smooth dark stone used for testing the quality of gold or silver alloys by rubbing them against it and noting the color of the mark made on the stone. I know one of the pieties of nature writing says that one can only have intimacy with nature and form community by staying in one place, answering to it and for it against the culture's assaults. But when I have tested my own experience for its genuineness and value, I find that I have consistently deepened my understanding of the intricate weave between nature and culture by learning about them in different places.

"I consider it implausible that human culture will settle back into an agrarian way of life in which geographic mobility is shunned in the interest of staying put. Human beings are thrilled by the technological prowess that keeps them moving all over the planet and beyond. We are not going to stop these movements, unless, of course, disaster demands it of us.

"For those who wish to celebrate an agrarian way of life, I hold no antagonism. Indeed, there is much to admire in the long study of one place. But what interests me, and what feels useful at this time in history, is to transpose what can be learned from more settled lifeways to the change and velocity of contemporary life. How, in a culture that is in love with its freedom and mobility, can individuals learn to conserve and preserve not only their own backyards but what is likely to become someone else's backyard in a year or two or twenty? The essay, or poem, or story can become a paradigm for reestablishing the spiritual intimacy with nature that we have lost from physical intimacy.

"I know that mobility can install an ethic of impermanence, of leaving one's mistakes and failures behind, rather than fixing them and fostering healing. But America is no longer an unsettled land, and as it grows more crowded, its membranes more permeable to the rest of the world, one finds that pulling up stakes and moving on leads one to face the same mistakes and failures played out in a new setting. We live in the same old story of fallibility and over-reaching goals that has been the bane and boon of human existence from the start. It does us good to face up to that -- our stunning potential for messing things up -- for without such awareness, we don't feel the need for restraint. And we do need mechanisms -- morality and law, plans and paradigms -- to restrain us, because it is our nature to dominate, control, and succeed against competition. For all our goodness, we are not benign animals."

Later in the volume Deming speaks of the role of the artist in fomenting cultural change:

"Culture is both the crop we grow and the soil in which we grow it. And human culture is the most powerful evolutionary force on Earth these days. The grief we feel at abuses of human power is the first positive step at transforming that power for the good. Legislation, information, and instruction cannot effect change at this emotional level -- though they play a significant role. Art is necessary because it gives us a new way of thinking and speaking, shows us what we are and what we have been blind to, and gives us new language and forms in which to see ourselves. To effect profound cultural change requires that we educate ourselves about our own interior wildness that has led us into such a hostile relationship with the forces that sustain us....

"I don't mean to say that when a forest is gone you can replace it with a poem. When a forest is gone, you cannot replace it. But with written words, you can bear witness, you can hold a memory of the forest for others to experience and celebrate, you can grieve over the loss and rage against the forces that have leveled the forest -- and through grief you can fall in love with forests again, and through that falling you can believe again in the human capacity for love and in the faith that we might learn to protect what we love."

Yes, yes, yes.

The photographs here were taken early Sunday morning, when I woke to find the hills dusted with snow: the only snow we've had all this mild and soggy winter, and thus especially magical and welcome. I dressed hurriedly, whistled for Tilly, and slipped outdoors before it all disappeared, climbing our hill as the bells of the village church broke through the morning mist. We crested the hill on icy paths, came down again on ice turned to mud, then crossed a field leaving footprints that melted behind us as the morning warmed up.

By the time we passed beneath the old oak and turned onto our homeward trail, the snow had all but vanished. Back home, it was entirely gone. Howard was up now, making tea as Tilly burst through the door into the kitchen, paws muddy, eyes gleaming: It snowed! It snowed!

For one brief, enchanted moment we had tasted true winter. And now I am ready for spring.

The passages above by Alison Hawthorne Deming are from Writing the Sacred Into the Real (Milkweed Editions, 2001). The poem in the picture captions is from Selected Poems by Mark Strand (Knopf, 1990). Both are highly recommended. All rights reserved by the authors.

The passages above by Alison Hawthorne Deming are from Writing the Sacred Into the Real (Milkweed Editions, 2001). The poem in the picture captions is from Selected Poems by Mark Strand (Knopf, 1990). Both are highly recommended. All rights reserved by the authors.

February 14, 2016

Tunes for a Monday Morning

The connecting thread between all of the music today is Lauren MacColl, an award-winning fiddle player, music scholar, and songwriter from the Black Isle in the Scottish Highlands. MacColl performs in the "chamber-folk" quartet Rant, in a duo with flautist Calum Stewart, and in a trio with singer/harpist Rachel Newton, in addition to her solo work, her on-going research into the old music of the Highlands, and collaborations with other musicians. She's released three solo albums to date: When Leaves Fall, Strewn With Ribbons, and Tune Book. "Creating new music is often a response to an encounter with the land, with people, and the emotions that experience evokes," MacColl says. "And I'm lucky to live in a particularly beautiful place, with a landscape that never fails to inspire me, both in life and in music."

Above: "Miss Ferguson of Raith/Mary MacDonald," performed by Rant in Edinburgh in 2013. The group consists of four Scottish fiddlers: Bethany and Jenna Reid from the Shetlands, Lauren MacColl and Sarah-Jane Summers from the Highlands. Their second album, Reverie, is coming out in May, and the trailer for it is lovely.

Below: "Da Haa," performed by Rant.

Next: "Crow Road Croft" performed by Calum Stewart on flute and Lauren MacColl on fiddle. (The names of the other musicians are not listed.) Stewart & MacColl have recorded one album together so far: Wooden Flute and Fiddle (2012).

And last, for something just a little bit different:

The Rachel Newton Trio performs Scottish folk flavored renditions of two American country music classics: Hank Williams' "I'm So Lonesome I Could Cry" and Dolly Parton's "Jolene." The trio consists of Rachel Newton on harp, Lauren MacColl on fiddle, and Mattie Foulds on percussion.

Happy Valentine's Day

The poem in the picture caption is from I Was Not Born (Noemi Press, 2014); all rights reserved by the author. The picture is from one of my sketchbooks.

The poem in the picture caption is from I Was Not Born (Noemi Press, 2014); all rights reserved by the author. The picture is from one of my sketchbooks.

February 11, 2016

Early morning thoughts on Nattadon Hill

From "Of Landscape and Longing," a beautifully crafted collection of essays by Carolyn Servid, who grew up in India but found her heart's home on the wild coast of Alaska:

"In his book The Land, theologion and historian Walter Brueggemann recognizes a human yearing for place -- and acknowledges that yearning as a primary human hunger. I think of it as an instinctual desire and need for my own habitat, a word primarily used to describe an ecological home range that allows a given species to thrive. We usually don't think of ourselves as the sample species, but I'd like to consider the notion of habitat in a human context for a moment. For those of us who use the English language, it is interesting to note that habitat is related to a cluster of other words -- habit, ability, rehabilitate, inhabit, and prohibit. They all come from a common Latin root, habere, and spin off a fundamental concept of relationship: 'to hold, hence to occupy or possess, hence to have.' They constitute a family of words that ground us by describing where we live, how we live, what we are able to do, how we heal ourselves, what our connections are to the landscape around us, what the boundaries are for our behavior. Together, they offer a set of parameters that might allow us to thrive in a place we think of as home.

"In his book The Land, theologion and historian Walter Brueggemann recognizes a human yearing for place -- and acknowledges that yearning as a primary human hunger. I think of it as an instinctual desire and need for my own habitat, a word primarily used to describe an ecological home range that allows a given species to thrive. We usually don't think of ourselves as the sample species, but I'd like to consider the notion of habitat in a human context for a moment. For those of us who use the English language, it is interesting to note that habitat is related to a cluster of other words -- habit, ability, rehabilitate, inhabit, and prohibit. They all come from a common Latin root, habere, and spin off a fundamental concept of relationship: 'to hold, hence to occupy or possess, hence to have.' They constitute a family of words that ground us by describing where we live, how we live, what we are able to do, how we heal ourselves, what our connections are to the landscape around us, what the boundaries are for our behavior. Together, they offer a set of parameters that might allow us to thrive in a place we think of as home.

"Given the biological evidence that the earth is our home, it's not difficult or even particularly imaginative to assert that we in Western societies have been living for centuries in a perpetual state of homesickness. We have worked hard -- somewhat blindly and somewhat successfully -- to disconnect ourselves from the source of our being. Our efforts have only partially succeeded because we cannot, in fact, separate ourselves from the fundamental truth of the context of our lives....

"Our legacy of homesickness stems in part from our inability to love the biological facts of our lives. The human hunger for place that Brueggemann speaks of might be thought of as a longing to be reconnected to the very source of our being. That longing is also a hunger for love -- for the nurturing that a home place provides, for its familiarity, its comfort, its human community, is natural community, its light and landscape. I believe, too, that our hunger for place is a yearning for a sense of the holy, for home ground sacred enough to sustain our faith, sacred enough that we will not violate it, sacred enough that our commitment to its holiness will not falter."

In another essay, Servid returns to the theme:

"Homesick, we say, when our hearts reach back to those places that have embraced us, our language allowing us the truth that when we're away from them we feel unhealthy, ill at ease. Sentimentality, another voice says, urging me to ignore the bonds that form between the human heart and peculiarities of the earth. But perhaps the sentiments we attach to place are more natural to us than we know. Perhaps what is at work is an instinctual desire, a need, for a set of specific details to help determine our bounds, our own habitat, a particular context in which we can come to know how to best live our individual lives, how best to survive not only within the human community, but in a distinct region of the larger natural community that is our only real home."

But what of those whose homes are transient ones, whether by preference or circumstance? What of those who are homeless, or exiled from home, or migrating from one "home place" to another? What of those (an increasing number of us) for whom home is an urban environment? Or those who have never found a place, outside of fiction and dreams, that feels like the place they belong? And how does this effect the creation of mythic art, when myth itself is so often rooted in the land?

We've touched on different aspects of this subject in previous posts (especially "Kith & Kin," but also "Writing Without Roots," "More Thoughts About Home," and "The Magic of Cities," if you happened to miss them), and I'm curious to know your thoughts. Is place important in your life? In your creative work? In your relationship to folklore and myth?

The two passages above are from "The Right Place for Love" and "The Distance Home" in Carolyn Servid's essay collection Of Landscape and Longing: Finding a Home at the Water's Edge (Milkweed Editions, 2000). The passage in the picture captions is from the title essay in Scott Russell Sander's Writing from the Center (Indiana University Press, 1995). All right reserved by the authors. The drawing above is by Eleanor Vere Boyle (1825-1916).

The two passages above are from "The Right Place for Love" and "The Distance Home" in Carolyn Servid's essay collection Of Landscape and Longing: Finding a Home at the Water's Edge (Milkweed Editions, 2000). The passage in the picture captions is from the title essay in Scott Russell Sander's Writing from the Center (Indiana University Press, 1995). All right reserved by the authors. The drawing above is by Eleanor Vere Boyle (1825-1916).

February 10, 2016

On art, culture, and radical hope

The Edge of the Civilized World: A Journey in Nature and Culture by Alison Hawthorne Deming has been on my Wish List for a while now, and I'm pleased to have finally gotten hold of a copy. The book begins with "a constellation of questions" about our place in the natural world, and as this is an issue often discussed here on on Myth & Moor, I'll quote the passage in full:

"What is civilization?" Deming asks. "Where and how is it being formed? On what assumptions is it founded? What should we hope for the future of humanity and our world? To what extent can our ideas, hopes and will shape the future? What has civilization blurred and rejected that we might clarify and call back into our shepherding intelligence? What lessons did our ancestors learn that we should not forget? And what of their practices would we be better off in leaving behind?

At this point in modernity, Deming continues, "one can do nothing without doubts and questions. We see everything from multiple perspectives: most of civilzation's gains have been earned at the expense of others, and for all its marvelous advances civilization has led the natural world to the edge of collapse. We can count, like the numbers on a doomsday clock, the species being driven out of existence. We can measure the hole we have made in the sky and the dirty pall that threatens to smother the Earth. We can predict the outcome of continuing to consume the world, but we cannot seem to stop ourselves from consuming it. The result seems to be that one either revels in consumption and forgets the future, or one retreats into solipsistic rage, lament and self-hatred. 'If humanity's the enemy,' writes the poet Chase Twichell, 'the enemy is me.'

"Knowing that civilization has been the royal standard under which conquest, genocide and enslavement have been committed throughout history, how can one just consider civilization's spiritual aspect: the good progress of humanity as we struggle to transcend the qualities in ourselves that rob us of faith in our own nature and rob others of their future? What antidote can be found to counteract the poison of anticipating an apocalyptic future in which human power destroys not only its own best inventions, but the very conditions under which life is given? Can we restore faith in civilization as an expression of radical hope in the best of the collective human enterprise on Earth -- those acts and accomplishments that honor beauty, wisdom, understanding, inventiveness, love and moral connection with others?

"Perhaps such questions are not the province of art, which thrives on being present in the moment, attending to what's local, peculiar, off-kilter and half-seen. Or perhaps such questions are the only province of art -- the attempt to understand, as John Haines once put it, the terms of one's existence. Art is a materialization of the inner life, so when a question persists, no matter its unwieldy or hazy nature, one knows one is stuck with it -- it is the needle through which one must pass the thread."

In Letters to a Young Poet, Rainer Maria Rilke advised:

"Be patient toward all that is unsolved in your heart, and try to love the questions themselves, like locked rooms and like books that are now written in a very foreign tongue. Do not now seek the answers, which cannot be given you because you would not be able to live them. And the point is, to live everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps you will then gradually, without noticing it, live along some distant day into the answer."

"I think about Rilke," mused Terry Tempest Williams, "who said that it's the questions that move us, not the answers. As a writer I believe it is our task, our responsibility, to hold the mirror up to social injustices that we see and to create a prayer of beauty."

Pictures: Rain and sun in the winter woods, and the first shoots of the wild daffodils. Words: The passage by Alison Hawthorne Deming is from The Edges of the Civilized World (Picador, 1998). The passage by Rainer Maria Rilke comes from Letters to a Young Poet, a wonderful little volume published by the recipient of the letters in 1929, three years after Rilke's death from a long-undiagnosed illness that turned out to be leukemia. The quote by Terry Tempest Williams is from A Voice in the Wilderness: Conversations with Terry Tempest Williams, edited by Michael Austin (Utah State University Press, 2006). The splendid poem in the picture captions is from Out There Somewhere by Native American poet Simon J. Ortiz (University of Arizona Press, 2002). All right reserved by the authors.

Pictures: Rain and sun in the winter woods, and the first shoots of the wild daffodils. Words: The passage by Alison Hawthorne Deming is from The Edges of the Civilized World (Picador, 1998). The passage by Rainer Maria Rilke comes from Letters to a Young Poet, a wonderful little volume published by the recipient of the letters in 1929, three years after Rilke's death from a long-undiagnosed illness that turned out to be leukemia. The quote by Terry Tempest Williams is from A Voice in the Wilderness: Conversations with Terry Tempest Williams, edited by Michael Austin (Utah State University Press, 2006). The splendid poem in the picture captions is from Out There Somewhere by Native American poet Simon J. Ortiz (University of Arizona Press, 2002). All right reserved by the authors.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 708 followers