Terri Windling's Blog, page 122

January 13, 2016

The books that shape us: Interlude

I had one of my own favorite books of childhood open on the studio couch this morning, and while I across the room doing art-related things, Tilly crawled underneath it and fell asleep. (The book was on her blanket, after all -- but I love the fact that she carefully tucked herself below it instead of squashing it. Good dog!) I quietly got my camera out and was able to snap this picture without waking her up. It makes my heart melt.

The book is The Golden Book of Fairy Tales, translated from the French by Marie Ponsot and illustrated by Adrienne S��gur.

January 12, 2016

The books that shape us: 2

From an essay by A.S. Byatt in The Pleasure of Reading, edited by Antonia Fraser:

"The roots of my thinking are a tangled maze of myths, folktales, legends, fairy stories. Robin Hood, King Arthur, Alexander of Macedon, Achilles and Odysseus, Apollo and Pan, Loki and Baldur, Sinbad and Haroun al Rashid, Rapunzel and Beauty and the Beast, Tom Bombadil and Cereberus. I have no idea now where I got all this, except for the Norse myths, which came from a turn of the century book, Asgard and the Gods, bought by my mother as a crib for her Ancient Norse and Icelandic exams at Cambridge. I read the Fairy Books of Andrew Lang and several collections of ballads, and 'How Horatio Kept the Bridge' from Macaulay's Lays of Ancient Rome. The tales and myths and legends...made it clear that there was another world, beside the world of having to be a child in a house, an inner world and a vast outer world with large implications -- good and evil, angels and demons, fate and love and terror and beauty -- and the comfort of the inevitable ending, not only the happy ending against odds, but the tragic one too.

"The roots of my thinking are a tangled maze of myths, folktales, legends, fairy stories. Robin Hood, King Arthur, Alexander of Macedon, Achilles and Odysseus, Apollo and Pan, Loki and Baldur, Sinbad and Haroun al Rashid, Rapunzel and Beauty and the Beast, Tom Bombadil and Cereberus. I have no idea now where I got all this, except for the Norse myths, which came from a turn of the century book, Asgard and the Gods, bought by my mother as a crib for her Ancient Norse and Icelandic exams at Cambridge. I read the Fairy Books of Andrew Lang and several collections of ballads, and 'How Horatio Kept the Bridge' from Macaulay's Lays of Ancient Rome. The tales and myths and legends...made it clear that there was another world, beside the world of having to be a child in a house, an inner world and a vast outer world with large implications -- good and evil, angels and demons, fate and love and terror and beauty -- and the comfort of the inevitable ending, not only the happy ending against odds, but the tragic one too.

"At the same time, and just as early, I remember the importance of poetry, Nursery rhymes, ballads, the 'Jackdaw of Rheims' from Richard Barham's The Ingoldsby Legends and A.A. Milne's Now We Are Six, 'The Rime of the Ancient Mariner' and 'Slowly silent now the moon' by Walter de la Mare. I think one of the most important writers to me ever has been Walter de la Mare, though it is a debt hard to recognize or acknowledge. Partly for the singing strange rhythms of his poetry, partly for the strange worlds and half-worlds he gave one glimpses of, the world of a pike suspended in thick gloom under a bridge, the journeyings of the Three Mulla Mulgars, which I read over and over. The most important poems were three coloring books we had, a page of poetry beside a picture, all three complete stories: The Pied Piper, Tennyson's 'The Lady of Shalott,' his Morte d'Arthur. I knew them all by heart long before I thought to ask who had written them. Their rhymes haunt everything I write, especially the Tennyson. The enclosed weaving lady became my private symbol for my reading and brooding self long before I saw what she meant for him, and for 19th century poetry in general.

"At the same time, and just as early, I remember the importance of poetry, Nursery rhymes, ballads, the 'Jackdaw of Rheims' from Richard Barham's The Ingoldsby Legends and A.A. Milne's Now We Are Six, 'The Rime of the Ancient Mariner' and 'Slowly silent now the moon' by Walter de la Mare. I think one of the most important writers to me ever has been Walter de la Mare, though it is a debt hard to recognize or acknowledge. Partly for the singing strange rhythms of his poetry, partly for the strange worlds and half-worlds he gave one glimpses of, the world of a pike suspended in thick gloom under a bridge, the journeyings of the Three Mulla Mulgars, which I read over and over. The most important poems were three coloring books we had, a page of poetry beside a picture, all three complete stories: The Pied Piper, Tennyson's 'The Lady of Shalott,' his Morte d'Arthur. I knew them all by heart long before I thought to ask who had written them. Their rhymes haunt everything I write, especially the Tennyson. The enclosed weaving lady became my private symbol for my reading and brooding self long before I saw what she meant for him, and for 19th century poetry in general.

"Truthfulness forces me to admit that we did not have that great anthology of magical and narrative verse, de la Mare's Come Hither, but we were brought up on its contents by my mother, who gave us poems and more poems, as though it was unquestionable that this was the very best thing she could do for us.

"What about fiction, as opposed to fairy tales? What I remember most vividly is learning fear, which I think may be important to all animals -- I used to love the song from The Jungle Book -- 'It is fear, oh little hunter, it is fear.' And I remember Blind Pew tapping, the terrible staircase and the heather-hunting in Kidnapped, I  remember Jane Eyre locked in the Red Room, and poor David Copperfield at the mercy of Mr. Murdstone, the horrors of Fagin in the condemned cell (I could only have been eight or nine) and worst of all (though I still have nightmares about executions) Pip on the marshes being grabbed by Magwitch in that brilliant and terrible beginning of Great Expectations. I must have been very little. I didn't understand any more than Pip that Magwitch's terrible companion was fictive.

remember Jane Eyre locked in the Red Room, and poor David Copperfield at the mercy of Mr. Murdstone, the horrors of Fagin in the condemned cell (I could only have been eight or nine) and worst of all (though I still have nightmares about executions) Pip on the marshes being grabbed by Magwitch in that brilliant and terrible beginning of Great Expectations. I must have been very little. I didn't understand any more than Pip that Magwitch's terrible companion was fictive.

"I remember my first meeting with evil, too, and it has only just recently struck me how strange that was. I worked my way along my grandmother's shelf of school prizes -- was I nine or ten? Or younger? And read Uncle Tom's Cabin before anyone had told me that slaves had really existed outside The Arabian Nights. Tom's sufferings and the evil of the system and the people who killed him, with cruelty or negligence, made me feel ill and appalled. I never talked to anyone about it. We sang about Christ's suffering in church but that seemed comparatively comfortable and institutional and had after all a happy ending, whereas Tom's story did not. And yet one is grateful for the glimpses of the dark: as long as they do not destroy, they strengthen."

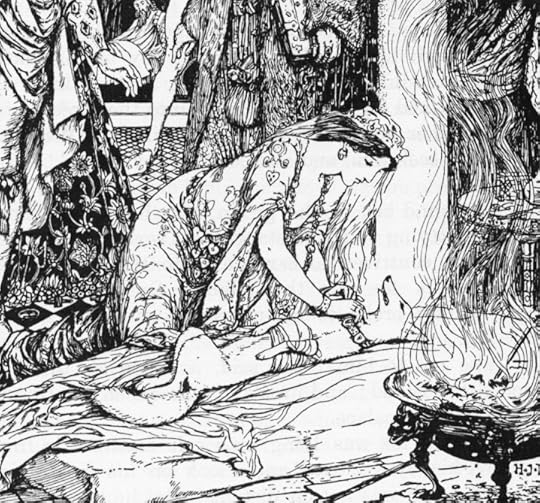

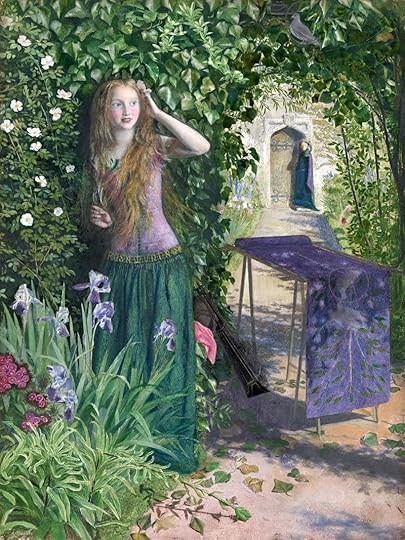

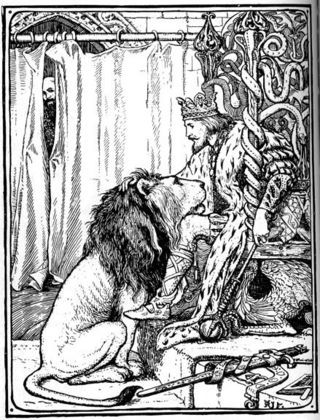

The art today is by Arthur Hughes, a Victorian painter associated with the Pre-Raphaelite movement. Born in London in 1832, Hughes studied art at Somerset House and the Royal Academy, and had his first picture accepted for a Royal Academy exhibition when he was only 17. Upon meeting Rossetti and other members of the original Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Hughes pledged himself to the Brotherhood's cause and spent the rest of his life creating paintings and drawings rooted in Pre-Raphaelite ideals. He was also a leading book illustrator in what was known as the "Sixties Group," remembered best today for his classic drawings for the fantasy novels of George Macdonald. The artist was married (to the model for his painting "April Love") and had six children, one of whom became a successful landscape painter. (The "fairy painter" Edward Robert Hughes was Arthur Hughes' nephew.) The artist died at home in London in 1915, after a long and prolific career.

The passage above comes from The Pleasure of Reading, edited by Antonia Fraser (Bloomsbury, 1992); I recommend reading A.S. Byatt's essay in full. All rights reserved by the author.

The passage above comes from The Pleasure of Reading, edited by Antonia Fraser (Bloomsbury, 1992); I recommend reading A.S. Byatt's essay in full. All rights reserved by the author.

January 11, 2016

The books that shape us: 1

For her anthology The Pleasure of Reading (published in an illustrated edition in 1992, and an expanded edition in 2015), Antonio Fraser asked a wide range of contemporary writers to describe their early reading, and what did (or did not) influence them. Here is how the great mystery writer Ruth Rendell answered the question:

"The picture I can still see in my mind's eye is of a dancing, gestulating thing with a human face and cat's ears, its body furred like a bear. The anomaly is that at the time, when I was about seven, the last thing I wanted was ever to see that picture again. I knew precisely where in the Andrew Lang Fairy Book it came, in which quarter of the book and between which pages, and I was determined never to look at it, it frightened me too much. On the other hand, so perverse are human beings, however youthful and innocent, that I was also terribly temped to peep at it. To flit quickly through the pages in the dangerous area and catch a tiny fearful glimpse.

"The picture I can still see in my mind's eye is of a dancing, gestulating thing with a human face and cat's ears, its body furred like a bear. The anomaly is that at the time, when I was about seven, the last thing I wanted was ever to see that picture again. I knew precisely where in the Andrew Lang Fairy Book it came, in which quarter of the book and between which pages, and I was determined never to look at it, it frightened me too much. On the other hand, so perverse are human beings, however youthful and innocent, that I was also terribly temped to peep at it. To flit quickly through the pages in the dangerous area and catch a tiny fearful glimpse.

"Now I can't even remember which of the Fairy Books it was, Crimson, Blue, Yellow, Lilac. I read them all. They were the first books I read which others had not either read or recommended to me, and they left me with a permanent fondness for fairy stories and with something else, something that has been of practical use to me as well as a perennial fascination. Andrew Lang began the process of teaching me how to frighten my readers....

"Now I can't even remember which of the Fairy Books it was, Crimson, Blue, Yellow, Lilac. I read them all. They were the first books I read which others had not either read or recommended to me, and they left me with a permanent fondness for fairy stories and with something else, something that has been of practical use to me as well as a perennial fascination. Andrew Lang began the process of teaching me how to frighten my readers....

"Because I had a Scandinavian mother -- I have to describe her thus as she was half-Swede, half-Dane, with an Icelandic grandmother, born in Stockholm, brought up in Copenhagen -- I was early on introduced to Hans Andersen. I never liked him. He was too much of a moralist for me. His stories mostly carried a message and a threat. Oddly enough, or perhaps not oddly at all, the one I hated the most was the favorite of my mother, who had her stern Lutheran side. This was 'The Girl Who Trod on a Loaf,' which is about ugsome Inger who used a loaf of bread as a stepping stone to avoid wetting her fine shoes at the ford. The rest of course was that she sank down into the Bog Wife's domain, a kind of cesspit of creepy-crawlies, and that is only the beginning of her misfortunes.

"I never really wanted to read anything my parents wanted me to read. No doubt this is normal. The exception would be Beatrix Potter, but we grow out of her early and only return to our passion after twenty or thirty years. Does anyone read The Water Babies today? Charles Kingsley is just as improving as Andersen but in a different way. It was social rather than moral evils he pointed out. Andersen never gave a thought to Inger's poverty and deprived childhood. The poor little chimney sweep's boys always excited my wonder and pity. I never imagined I would one day live in a house where, inside the huge chimney, you can see the footholds the boys used to go up with their brushes. The water creatures the metamorphosed Tom encountered started me on a lifelong interest in natural history.

"Two years after Tolkien's The Hobbit was published I read it for the first time. Twenty years later I read it again and experienced just the same feeling of delight and  happiness and a quite breathless pleasure. That first time, when I was nine, was also the first time I remember feeling this. It is a sensation known to all lovers of fiction and comes about at page two, when you know it's not only going to be a good one, but immensely satisfying, enthralling, not to be put down without resentment, drawing inexorably to a conclusion of power and dramatic soundness.

happiness and a quite breathless pleasure. That first time, when I was nine, was also the first time I remember feeling this. It is a sensation known to all lovers of fiction and comes about at page two, when you know it's not only going to be a good one, but immensely satisfying, enthralling, not to be put down without resentment, drawing inexorably to a conclusion of power and dramatic soundness.

"While I was engrossed in The Hobbit I was also reading The Complete Book of British Butterflies, a fairly large tome by the great naturalist F.W. Frowhawk -- what a wonderful name that is, he sounds like a giant butterfly or moth himself. That copy I still have, can see it on the shelves from where I sit writing. I used to collect butterflies, kill them in a bottle containing ammonia on cottonwool and mount them on pins. The disapproval of a schoolfellow, whom I rather disliked but must have respected, put an end to that and I have killed hardly anything since, a few flies, a mosquito or two. Outside the pages of fiction, that is."

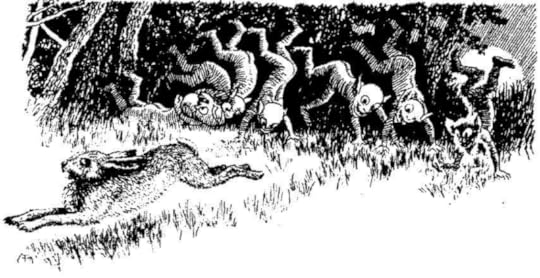

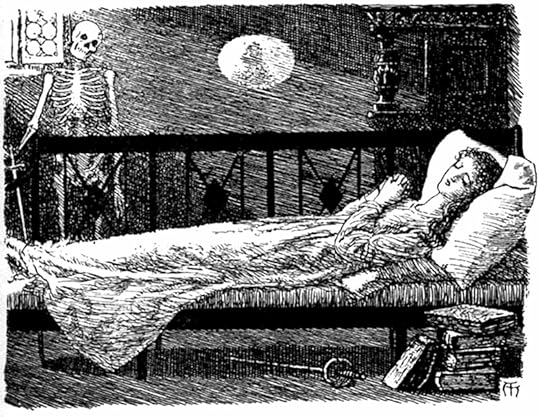

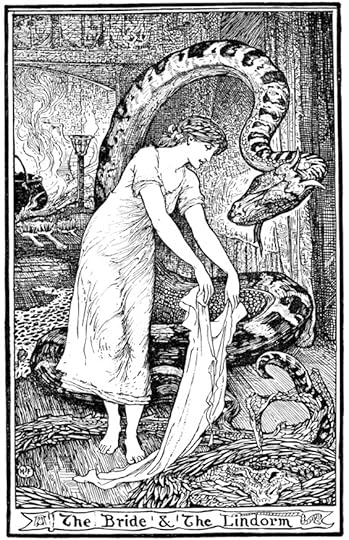

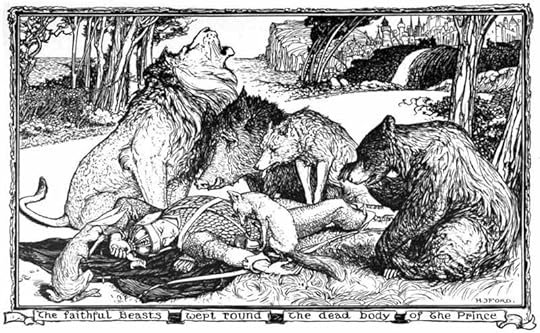

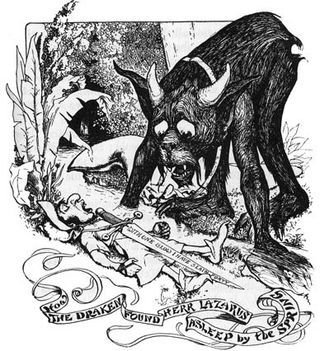

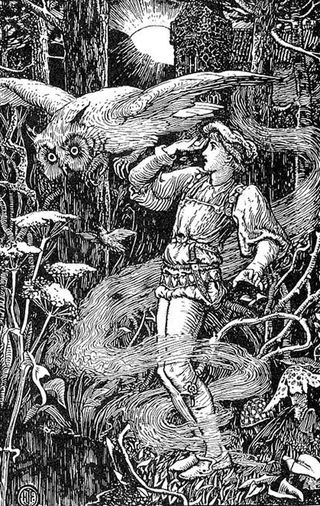

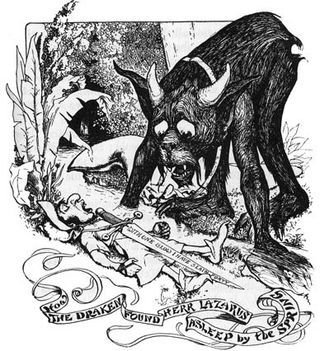

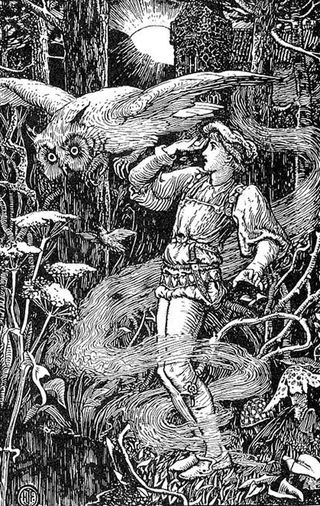

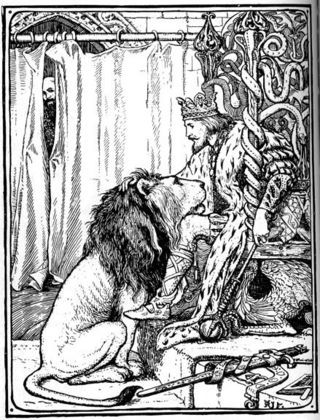

The drawings today are from Andrew Lang's Fairy Books, published from 1889 to 1910, illustrated by H.J. Ford. I have no idea which particular illustration from the series frightened Ruth Rendell, however!

Henry Justice Ford (1860-1941) was born and raised in London, where his father was a solicitor and the entire family was mad for cricket. (His father wrote books on the subject and his brother played professionally.) He studied classics at Cambridge, received a first-class degree, and then veered into an art career instead, training at the Slade and the Bushey schools of art. In addition to illustrating children's books and classics from the 1880s through the 1920s, Ford also painted historical works and landscapes exhibited at the Royal Academy, designed the Peter Pan costume for J.M. Barrie's first staging of his famous play, and was part of an artistic London set that included Barrie, P.G. Wodehouse, and Arthur Conan Doyle. He settled in Kensington, where he married late in life and had one much-loved adopted daughter.

The passage above comes from The Pleasure of Reading, edited by Antonia Fraser (Bloomsbury, 1992); all rights reserved by Fraser and the Ruth Rendell estate.

The passage above comes from The Pleasure of Reading, edited by Antonia Fraser (Bloomsbury, 1992); all rights reserved by Fraser and the Ruth Rendell estate.

The books that shape us

For her anthology The Pleasure of Reading (published in an illustrated edition in 1992, and an expanded edition in 2015), Antonio Fraser asked a wide range of contemporary writers to describe their early reading, and what did (or did not) influence them. Here is how the great mystery writer Ruth Rendell answered the question:

"The picture I can still see in my mind's eye is of a dancing, gestulating thing with a human face and cat's ears, its body furred like a bear. The anomaly is that at the time, when I was about seven, the last thing I wanted was ever to see that picture again. I knew precisely where in the Andrew Lang Fairy Book it came, in which quarter of the book and between which pages, and I was determined never to look at it, it frightened me too much. On the other hand, so perverse are human beings, however youthful and innocent, that I was also terribly temped to peep at it. To flit quickly through the pages in the dangerous area and catch a tiny fearful glimpse.

"The picture I can still see in my mind's eye is of a dancing, gestulating thing with a human face and cat's ears, its body furred like a bear. The anomaly is that at the time, when I was about seven, the last thing I wanted was ever to see that picture again. I knew precisely where in the Andrew Lang Fairy Book it came, in which quarter of the book and between which pages, and I was determined never to look at it, it frightened me too much. On the other hand, so perverse are human beings, however youthful and innocent, that I was also terribly temped to peep at it. To flit quickly through the pages in the dangerous area and catch a tiny fearful glimpse.

"Now I can't even remember which of the Fairy Books it was, Crimson, Blue, Yellow, Lilac. I read them all. They were the first books I read which others had not either read or recommended to me, and they left me with a permanent fondness for fairy stories and with something else, something that has been of practical use to me as well as a perennial fascination. Andrew Lang began the process of teaching me how to frighten my readers....

"Now I can't even remember which of the Fairy Books it was, Crimson, Blue, Yellow, Lilac. I read them all. They were the first books I read which others had not either read or recommended to me, and they left me with a permanent fondness for fairy stories and with something else, something that has been of practical use to me as well as a perennial fascination. Andrew Lang began the process of teaching me how to frighten my readers....

"Because I had a Scandinavian mother -- I have to describe her thus as she was half-Swede, half-Dane, with an Icelandic grandmother, born in Stockholm, brought up in Copenhagen -- I was early on introduced to Hans Andersen. I never liked him. He was too much of a moralist for me. His stories mostly carried a message and a threat. Oddly enough, or perhaps not oddly at all, the one I hated the most was the favorite of my mother, who had her stern Lutheran side. This was 'The Girl Who Trod on a Loaf,' which is about ugsome Inger who used a loaf of bread as a stepping stone to avoid wetting her fine shoes at the ford. The rest of course was that she sank down into the Bog Wife's domain, a kind of cesspit of creepy-crawlies, and that is only the beginning of her misfortunes.

"I never really wanted to read anything my parents wanted me to read. No doubt this is normal. The exception would be Beatrix Potter, but we grow out of her early and only return to our passion after twenty or thirty years. Does anyone read The Water Babies today? Charles Kingsley is just as improving as Andersen but in a different way. It was social rather than moral evils he pointed out. Andersen never gave a thought to Inger's poverty and deprived childhood. The poor little chimney sweep's boys always excited my wonder and pity. I never imagined I would one day live in a house where, inside the huge chimney, you can see the footholds the boys used to go up with their brushes. The water creatures the metamorphosed Tom encountered started me on a lifelong interest in natural history.

"Two years after Tolkien's The Hobbit was published I read it for the first time. Twenty years later I read it again and experienced just the same feeling of delight and  happiness and a quite breathless pleasure. That first time, when I was nine, was also the first time I remember feeling this. It is a sensation known to all lovers of fiction and comes about at page two, when you know it's not only going to be a good one, but immensely satisfying, enthralling, not to be put down without resentment, drawing inexorably to a conclusion of power and dramatic soundness.

happiness and a quite breathless pleasure. That first time, when I was nine, was also the first time I remember feeling this. It is a sensation known to all lovers of fiction and comes about at page two, when you know it's not only going to be a good one, but immensely satisfying, enthralling, not to be put down without resentment, drawing inexorably to a conclusion of power and dramatic soundness.

"While I was engrossed in The Hobbit I was also reading The Complete Book of British Butterflies, a fairly large tome by the great naturalist F.W. Frowhawk -- what a wonderful name that is, he sounds like a giant butterfly or moth himself. That copy I still have, can see it on the shelves from where I sit writing. I used to collect butterflies, kill them in a bottle containing ammonia on cottonwool and mount them on pins. The disapproval of a schoolfellow, whom I rather disliked but must have respected, put an end to that and I have killed hardly anything since, a few flies, a mosquito or two. Outside the pages of fiction, that is."

The drawings today are from Andrew Lang's Fairy Books, published from 1889 to 1910, illustrated by H.J. Ford. I have no idea which particular illustration from the series frightened Ruth Rendell, however!

Henry Justice Ford (1860-1941) was born and raised in London, where his father was a solicitor and the entire family was mad for cricket. (His father wrote books on the subject and his brother played professionally.) He studied classics at Cambridge, received a first-class degree, and then veered into an art career instead, training at the Slade and the Bushey schools of art. In addition to illustrating children's books and classics from the 1880s through the 1920s, Ford also painted historical works and landscapes exhibited at the Royal Academy, designed the Peter Pan costume for J.M. Barrie's first staging of his famous play, and was part of an artistic London set that included Barrie, P.G. Wodehouse, and Arthur Conan Doyle. He settled in Kensington, where he married late in life and had one much-loved adopted daughter.

The passage above comes from The Pleasure of Reading, edited by Antonia Fraser (Bloomsbury, 1992); all rights reserved by Fraser and the Ruth Rendell estate.

The passage above comes from The Pleasure of Reading, edited by Antonia Fraser (Bloomsbury, 1992); all rights reserved by Fraser and the Ruth Rendell estate.

January 10, 2016

Tunes for a Monday Morning

It's been a grey, wet winter on Dartmoor where many of us long for a glimpse of the sun, so I'll start today with some earthy green magic from the London band Firefly Burning, whose work blends influences from folk, jazz, classical minimalism (�� la Philip Glass), pop, and poetry.

Above, "Pioneer," from the band's new album, Skeleton Hill.

Below, a performance of the title song from Skeleton Hill.

Next, "Beloved," performed by Firefly Burning at the Spitalfields Music Summer Festival 2014.

And to end with, a video celebrating the beauty to be found in the season we're in:

"Make It Holy" by The Staves, from their new album If I Was. This folk trio consists of three sisters (Emily, Jessica, & Camilla Stavely-Taylor) from Watford in Hertfordshire. (If you'd like a little more of their music this morning, go here and here.)

Many thanks, by the way, to The Nest Collective, who introduced me to Firefly Burning. I highly recommend their recent New Year's Playlist, which contains a lovely range of traditional and new folk music.

January 8, 2016

Between the storms: meditation in a wet winter woodland

From Walking Nature Home, a memoir by plant biologist Susan J. Tweit:

"Biologist E.O. Wilson calls humans' enate empathy for other species 'biophilia,' an inborn bond that links humans with other life. This instinctive connection may originiate in the molecules of our bodies that we hold in common with every cell of every kind of life.

"It is certainly reinforced by the thousands or millions of other lives we shelter, inside and out. There are ten times as many microbial cells in our body, say biologists, as human cells: the colony of microscopic mites that preen our skin of shed cells and other detritus; the 'bacterial nation' that populates our guts, a gastrointenstinal consortium whose individuals digest our food in exchange for shelter from the deadly levels of oxygen in the outside air; and the organelles of our cells, which are formerly free-swimming bacteria that long ago moved in and made themselves at home, as well as indespensible.

"Many of these millions are actively engaged in nurturing us. The five hundred to one thousand species and countless individual microbes that make up our gastrointenstinal consortium, for instance, aid us in obtaining nutrition by breaking down carbohydrates we could not otherwise process. They also protect the environment that feeds and shelters them by fending off outbreaks of potentially dangerous species of bacteria, and they may even regulate blood flow and capillary development in our intenstinal walls. These other lives interact so intimately with our existence that what we think of as 'I,' a solitary individual, is in reality 'we,' a thriving community.

"No wonder we have an inborn affinity for the rest of nature. It is who we are. The bonds we are born with to other species can't help but nuture our ability to link to each other."

"There is a way that nature speaks, that land speaks," says Native American novelist & poet Linda Hogan (in Dwellings, her beautiful collection of essays). "Most of the time we are simply not patient enough, quiet enough, to pay attention to the story."

Today, in the gentle lull between storms, the hound and I walk the hills quietly, listening to rain dripping from the trees and thinking about our connections to all that is here.

Paying attention to the story.

The passages above are from Walking Nature Home: A Life's Journey by Susan J. Tweit (University of Texas Press, 2009), and Dwellings: A Spiritual History of the Living World by Linda Hogan (WW Norton, 1993). The poem in the picture captions is by Native Alaskan poet Mary TallMountain, first published in That's What She Said: Contemporary Poetry & Fiction by Native Women, edited Rayna Green (Indiana University Press, 1984). All rights reserved by the authors.

The passages above are from Walking Nature Home: A Life's Journey by Susan J. Tweit (University of Texas Press, 2009), and Dwellings: A Spiritual History of the Living World by Linda Hogan (WW Norton, 1993). The poem in the picture captions is by Native Alaskan poet Mary TallMountain, first published in That's What She Said: Contemporary Poetry & Fiction by Native Women, edited Rayna Green (Indiana University Press, 1984). All rights reserved by the authors.

January 6, 2016

From the archives: Secret Threads

Please forgive me for running two archive posts in a row, but the C.S. Lewis quote in Tuesday's offering made me think of this lovely passage by Lewis; and the art of Mr. Finch is always worth a re-visit. I added a few more pictures below, so the post isn't entirely old....

"You may have noticed," wrote C.S. Lewis, "that the books you really love are bound together by a secret thread. You know very well what is the common quality that makes you love them, though you cannot put it into words: but most of your friends do not see it at all, and often wonder why, liking this, you should also like that.

"Again, you have stood before some landscape, which seems to embody what you have been looking for all your life; and then turned to the friend at your side who appears to be seeing what you saw -- but at the first words a gulf yawns between you, and you realise that this landscape means something totally different to him, that he is pursuing an alien vision and cares nothing for the ineffable suggestion by which you are transported.

"Even in your hobbies," Lewis asks, "has there not always been some secret attraction which the others are curiously ignorant of -- something, not to be identified with, but always on the verge of breaking through, the smell of cut wood in the workshop or the clap-clap of water against the boat's side? Are not all lifelong friendships born at the moment when at last you meet another human being who has some inkling (but faint and uncertain even in the best) of that something which you were born desiring, and which, beneath the flux of other desires and in all the momentary silences between the louder passions, night and day, year by year, from childhood to old age, you are looking for, watching for, listening for?

"You have never had it. All the things that have ever deeply possessed your soul have been but hints of it -- tantalising glimpses, promises never quite fulfilled, echoes that died away just as they caught your ear. But if it should really become manifest -- if there ever came an echo that did not die away but swelled into the sound itself -- you would know it. Beyond all possibility of doubt you would say, 'Here at last is the thing I was made for.' "

This, to me, is what fantasy literature (and mythic arts) does best: it tugs on those secret threads, evokes bright worlds half-glimpsed at the corner of our eyes...where the heart's desire lies just ahead, but always just ahead, beyond the next turn of the page.

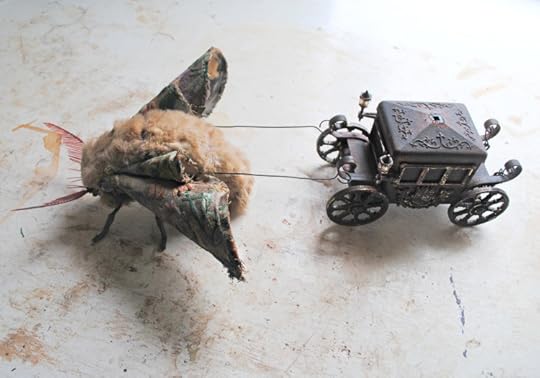

The gorgeous soft sculpturers here are by Mr. Finch, a textile artist in Leeds, near the Yorkshire Dales, with a name straight out of a fairy tale.

"My main inspirations come from nature," he writes. "Flowers, insects and birds really fascinate me with their amazing life cycles and extraordinary nests and behaviour. British folklore is also so beautifully rich in fabulous stories and warnings and never ceases to be at the heart of what I make. Shape shifting witches, moon gazing hares and a smartly dressed devil ready to invite you to stray from the path. Humanizing animals with shoes and clothes is something I���ve always done and I imagine them to come alive at night. Getting dressed and helping an elderly shoemaker or the tired housewife.

"Most of my pieces use recycled materials, not only as an ethical statement, but I believe they add more authenticity and charm. A story sewn in, woven in. Velvet curtains from an old hotel, a threadbare wedding dress and a vintage apron become birds and beasts, looking for new owners and adventures to have. Storytelling creatures for people who are also a little lost, found and forgotten���."

Visit Mr. Finch's website and to see more of his wondrous work. I love it deeply.

The passage above is from The Problem of Pain by C.S. Lewis, published in The Centenary Press' "Christian Challenge" series in 1940. I first read it for a class on Lewis way back in my university days (as a non-Christian, it's not a book I would have been likely to pick up myself), and though it is indeed quite theological, it contains interesting passages on a number of other subjects too. In class, we read it in conjunction with Lewis' Grief Observed, about the death of his wife, which was a fascinating pairing.

January 5, 2016

From the archives: Gracious Acceptance

To continue the discussion on gift-exchange....

The other side of the coin from the art of gift-giving is the less heralded art of gift-receiving -- and to live a balanced, creatively fecund life we must learn to practice both with equal skill. But as Alexander McCall Smith points out (in Love Over Scotland), the act that he calls gracious acceptance is "an art which most never bother to cultivate. We think that we have to learn how to give, but we forget about accepting things, which can be much harder than giving."

"Until we can receive with an open heart," notes psychologist Bren�� Brown astutely, "we're never really giving with an open heart. When we attach judgment to receiving help, we knowingly or unknowingly attach judgment to giving help."

"Human life runs its course in the metamorphosis between receiving and giving," the German Romantic poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe once wrote; and art-making, too, thrives in the space where giving and receiving dance in partnership. We take in the gifts of inspiration, shape them to our purposes, and then pass those gifts along through our stories, paintings, and other creative works.

To be skilled in the art of "gracious acceptance" is to be wide-open and receptive to the gifts the muses bring, and this skill, it seems to me, is helped or hindered by one's perception of the emotion of gratitude. There are those for whom gratitude is an uncomfortable, weakening, even shameful feeling; while others of us experience gratitude in a warm and positive manner, perceiving its ties as chords of connection, not heavy chains of obligation.

The narrator of Elizabeth Berg's novel Open House is clearly in the latter camp: "I made cranberry sauce," she tells us, "and when it was done put it into a dark blue bowl for the beautiful contrast. I was thinking, doing this, about the old ways of gratitude: Indians thanking the deer they'd slain, grace before supper, kneeling before bed. I was thinking that gratitude is too much absent in our lives now, and we need it back, even if it only takes the form of acknowledging the blue of a bowl against the red of cranberries."

Mary Oliver, too, is a writer who seems to follow Meister Erkhart's dictum that "if the only prayer you ever say in your entire life is thank you, it will be enough" -- for every poem she writes is a hymn of gratitude for the commonplace marvels of daily living. Take her 1992 poem "Morning," for example:

Salt shining behind its glass cylinder.

Milk in a blue bowl. The yellow linoleum.

The cat stretching her black body from the pillow.

The way she makes her curvaceous response to the small, kind gesture.

Then laps the bowl clean.

Then wants to go out into the world

where she leaps lightly and for no apparent reason across the lawn,

then sits, perfectly still, in the grass.

I watch her a little while, thinking:

what more could I do with wild words?

I stand in the cold kitchen, bowing down to her.

I stand in the cold kitchen, everything wonderful around me.

Art-making, like gift giving, requires two separate actions: giving and receiving, both of them equally important. We breathe in the world and push it out again: inhaling, exhaling; the cycle kept in motion; never resting for too long on one side and not the other. The perpetual giver, like the perpetual receiver, is an artist (and a person) out of balance, in danger of draining the creative well dry. It's hard work, and it's humbling work, to master both roles equally, including whichever one we find the hardest -- but that's precisely the task that art (and life) demands of us.

"The reality of all life is interdependence," notes cultural anthropologist Mary Catherine Bateson. "We need to compose our lives in such a way that we both give and receive, learning to do both with grace, seeing both as parts of a single pattern rather than as antithetical alternatives."

"When we give cheerfully and accept gratefully," says Maya Angelou, "everyone is blessed."

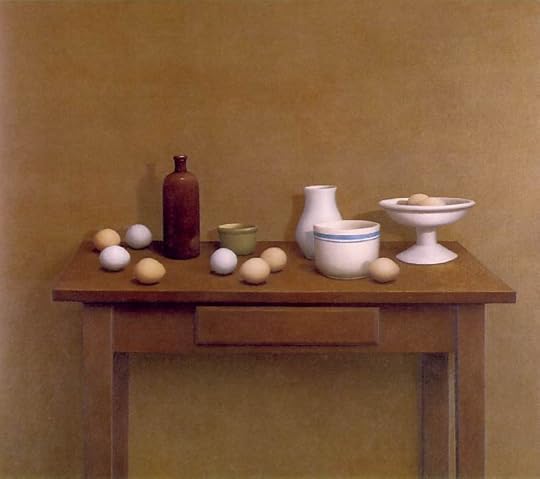

The quietly beautiful still life paintings here today are by the American artist William Bailey. Born in Iowa in 1930, educated at the University of Kansas, Bailey is now Professor Emeritus of Art at Yale University.

"Morning" by Mary Oliver is from New and Selected Poems (Beacon Press, 1992), which is highly recommended. All rights reserved by the author.

"Morning" by Mary Oliver is from New and Selected Poems (Beacon Press, 1992), which is highly recommended. All rights reserved by the author.

Gift exchange

I've been thinking a lot about gifts lately, in all the various meanings of the word -- prompted, of course, by the season of holiday gift-giving that has just passed. Here in "Austerity Britain," where work and money are increasingly scarce for those in freelance and arts professions (which are precarious even at the best of times), a truly frightening number of people are struggling just to put food on the table and keep the lights on overhead. And then comes Christmas, with its lovely old traditions but overwhelming modern expectations; with its roots planted in the good soil of family, community, folklore, and sacred stories, but its leaves unfurled in the toxic air of commercialism and over-consumption.

Some of us cherish the holiday; some of us simply cope with it and then sigh with relief when it's all over; some of us re-shape it into something more nurturing and reflective of our own ideals; some of us turn our backs on it altogether; and some of us weren't raised with Christmas at all, but simply watch while the rest of the Western world goes crazy for a few weeks every year. At Bumblehill, we celebrate Winter Solstice and Yule rather than Christmas, and focus on feasting and doing things together as a family. Our gift-giving is the simple (but loving) act of distributing little packages of home-made kiffles: each cookie filled with the talk and laughter we share in the long day it takes to make them all.

I love the act of gift-giving (at any time of year), but not the commercial pressure to shop and spend, especially in these lean financial times when life is hard, even desperate, for so many. I also prefer to view gift-exchange as a daily part of life, not something confined to holidays. We gift each other with meals prepared, with gardens tended, with the chores that keep a household running, with kindness, patience, care, attention...a constant giving-and-receiving that starts at home and extends into the world through friendship, community, and activism.

Making art is a form of gift-giving, made wondrous by the way that some of our creations move outward far beyond our ken, gifting recipients we do not know, will never meet, and sometimes could never imagine. And I, in turn, have received great gifts from writers, painters, musicians, dramatists and others who will never know of my existence either, and yet their words, images, or ideas, coming to me at the right time, have literally saved me.

The paradox inherent in making art, of course, is that it's an act involving both giving and receiving. Like breathing, it requires both, the inhalation and the exhalation. We receive the gift of inspiration (inhale), give it shape and form and pass it on (exhale).

The word "gift" itself is commonly used to describe artistic talent: she's a gifted cellist, he's a gifted poet. But where does that "gift" of inspiration comes from? In semi-secular modernity, we tend to be politely vague about such things -- but in her book Big Magic, Elizabeth Gilbert has an unusual answer to the question:

"I should explain," she says, "at this point that I've spent my entire life in devotion to creativity, and along the way I've developed a set of beliefs about how it works -- and how to work with it -- that is entirely and unapologetically based upon magical thinking. And when I refer to magic here, I mean it literally. Like, in the Hogwarts sense. I am referring to the supernatural, the mystical, the inexplicable, the surreal, the divine, the transcendent, the otherworldly. Because the truth is, I believe that creativity is a force of enchantment -- not entirely human in its origins....

"I believe that our planet is inhabited not only by animals and plants and bacteria and viruses, but also by ideas. Ideas are a dis-embodied, energetic life-form. They are completely separate from us, but capable of interacting with us -- albeit strangely. Ideas have no material body, but they do have consciousness, and they most certainly have will. Ideas are driven by a single impulse: to be made manifest. And the only way an idea can be made manifest in our world is through collaboration with a human partner. It is only through a human's efforts that an idea can be escorted out of the ether and into the material world."

Rationalists will scoff at Gilbert's words, but there's enough mysticism in my own beliefs that her concept of creativity doesn't seem so very far-fetched to me; indeed, my only quibble with the paragraph above is that I'm not entirely convinced that those ideas necessarily require a human partner. (Perhaps animals and others with whom we share the planet have art forms of their own that we don't yet perceive.)

A little later in the book, Gilbert writes about creative work in terms that even the rationalists among us might recognize: "Most of my writing life, to be perfectly honest, is not freaky, old-time, voodoo-style Big Magic. Most of my writing life consists of nothing more than unglamorous, disciplined labor. I sit at my desk, and I work like a farmer, and that's how it gets done. Most of it is not fairy dust in the least.

"But sometimes it is fairy dust. Sometimes, when I'm in the midst of writing, I feel like I'm suddenly walking on one of those moving sidewalks you find in an airport terminal; I still have a long slog to my gate, and my baggage is still heavy, but I can feel myself being gently propelled by some exterior force. Something is carrying me along -- something powerful and generous -- and that something is decidedly not me....

"I only rarely experience this feeling, but it's the most magnificent sensation imaginable when it arrives. I don't think there is a more perfect happiness to be found in life than this state, except perhaps falling in love. In ancient Greek, the word for the highest degree of human happiness is eudaimonia, which basically means 'well-daemoned' -- that is, nicely taken care of by some external divine creative spirit guide."

(We've discussed the Greco-Roman idea of "creative daemons" in a previous post. Go here if you'd like to know more.)

C.S. Lewis, writing from a Christian perspective, also noted the mystical quality of creative inspiration:

"In the Author���s mind there bubbles up every now and then the material for a story. For me it invariably begins with mental pictures. This ferment leads to nothing unless it is accompanied with the longing for a Form: verse or prose, short story, novel, play or what not. When these two things click you have the Author���s impulse complete. It is now a thing inside him pawing to get out. He longs to see that bubbling stuff pouring into that Form as the housewife longs to see the new jam pouring into the clean jam jar. This nags him all day long and gets in the way of his work and his sleep and his meals. It���s like being in love."

"The artist's gift refines the materials of perception or intuition that have been bestowed upon him," says Lewis Hyde in his masterful book on the subject, The Gift: Creativity & the Artist in the Modern World. "To put it another way, if the artist is gifted, the gift increases in its passage through the self. The artist makes something higher than what he has been given, and this, the finished work, is the third gift, the one offered to the world."

Madeleine L'Engle was of a similar mind. In Walking on Water: Reflections on Faith & Art she wrote: "'We, and I think I'm speaking for many writers, don't know what it is that sometimes comes to make our books alive. All we can do is write dutifully and day after day, every day, giving our work the very best of what we are capable. I don't think that we can consciously put the magic in; it doesn't work that way. When the magic comes, it's a gift.''

���If," L'Engle added, "the work comes to the artist and says, 'Here I am, serve me,' then the job of the artist, great or small, is to serve. The amount of the artist's talent is not what it is about. Jean Rhys said to an interviewer in the Paris Review, 'Listen to me. All of writing is a huge lake. There are great rivers that feed the lake, like Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky. And there are mere trickles, like Jean Rhys. All that matters is feeding the lake. I don't matter. The lake matters. You must keep feeding the lake.' "

"One of the things we continue to learn from Native Peoples," says Terry Tempest Williams, "is that stories are our medicine bundles. I feel that way about our essays, our poems, our fictions. That it is the artist who carries the burden of the storyteller. Terrence Des Pres speaks of a prose witness that relies on the imagination to respond to the world as we see it, feel it, and dare to ask the questions that will not let us sleep. Imagination. Attention to details. Making the connections. Art -- right words to station the mind and hold the heart ready."

The gift of paying attention, of witnessing others' lives and passing the "medicine" of their stories, our stories, from generation to generation is the particular gift required of us as artists. Not only of us, but especially of us; in whatever artform we chose to work in.

Jane Yolen puts it most succinctly. "Touch magic," she says, "and pass it on."

January 3, 2016

Tunes for a Monday Morning

In the hush of a winter morning on Dartmoor, as we move gently into a new week and new year, I'd like to re-visit the music of Italian pianist and composer Ludovico Einaudi, which is steeped in his classical training but borrows from other genres and art forms.

Above: "Walk," an exquisite song from Einaudi's 2013 album, In a Time Lapse.

Below: The composer discusses the process of how he put In a Time Lapse together. He conceives of "the entire voyage as a book, like when you are reading or writing a novel, so that every part is a chapter where some elements come back in different ways, in the music's different and reccuring themes."

And below, to end with:

"Divinire," from Einaudi's 2006 album of the same name. The performance was filmed in the Palazzo Te in Mantova, Italy.

At this time of year, it is dark when I climb the path to the studio each morning. The cabin rattles with gusts of wind; the stream behind it is roaring, swollen with rain. I switch on a lamp, turn on the stereo, and Eidaudi's music blends into the song of the storm. Tilly circles, then settles beside me; coffee steams in my cup; and a new day begin

"It's only when we become aware or are reminded that our time is limited that we can channel our energy into truly living," Einaudi once said.

The difficult year that I've just left behind has been an all too effective reminder that life and time are limited indeed, but today a brand new year lies before us. It's an empty white page, a blank canvas, a fresh notebook.

An invitation to possibility.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 708 followers