Terri Windling's Blog, page 117

April 25, 2016

From the archives: Mud and the Muse

When you follow your dog...

...into a wildflower bog...

...there's no help for it, you're going to get wet, muddy, and stinky.

But you learn to be agile in the mud and muck...

...and to find new ways to get where you want to go...

...and you discover things that you would have otherwise missed...

...like this lovely water garden at the end of the leat.

Following the Muse is like that too. Sometimes, in the middle of a story or a painting, you find yourself wallowing through the sticky, boggy bits...

...and you just have to keep on going, no matter where it leads.

But I'm ready for the journey. I'm wearing sturdy boots, and I'm prepared to get muddy. So let's go.

Words: The poem in the picture captions is from Territories: Writing from Innu Assi, Qu��bec and Scotland (Edinburgh International Book Festival/Scottish Poetry Library); all rights reserved by the author. Pictures: A leat, a bog, and a wet, stinky dog.

Words: The poem in the picture captions is from Territories: Writing from Innu Assi, Qu��bec and Scotland (Edinburgh International Book Festival/Scottish Poetry Library); all rights reserved by the author. Pictures: A leat, a bog, and a wet, stinky dog.

April 24, 2016

Tunes for a Monday Morning

We're back to Scotland for this week's music, starting with two traditional Anglo-Scots ballads from the Glasgow band Top Floor Taivers: Claire Hastings (voice & ukulele), Tina Jordan Rees (piano), Gr��inne Brady (fiddle), and Heather Downie (voice & clarsach). The band has one lovely EP out so far, The Top Floor Taivers; and Claire Hastings' first album out, From the River to the Railroad, will be released later this week.

Above, a performance of "Captain Ward," filmed in Glasgow in January.

Below, a performance of "The Rocks o' Gibralter," from the same filming session.

Next, two traditional Gaelic ballads from D��imh (pronounced dive), based in the West Highlands. The band, whose name means "kinship" in Gaelic, consists of Angus MacKenzie (pipes and whistle), Ellen MacDonald (voice), Gabe McVarish (fiddle), Murdo Cameron (mandola, mandolin, and accordion), and Ross Martin (guitar). D��imh has five terrific albums out so far, the latest of which is The Hebridean Sessions (2015).

Above, "Cuir A-nall," performed at Celtic Connections in Glasgow in January.

Below, "Dhannsamaid le Ailean," another performance from Celtic connections.

These two are for Stuart Hill, who loves a good piper...and Angus MacKenzie is very good indeed.

April 22, 2016

In a Devon Wood

by Denise Levertov

Elves are no smaller

than men, and walk

as men do, in this world,

but with more grace than most,

and are not immortal.

Their beauty sets them aside

from other men and from women

unless a woman has that cold fire in her

called poet: with that

she may see them and by its light

they know her and are not afraid

and silver tongues of love

flicker between them.

The poem above is from Poems of Denise Levertov: 1960-1967 (New Directions, 1983); the poem in the picture captions is from The Journal of Mythic Arts (2006); the exquisite pencil drawings are by my friend & neighbor Alan Lee, who first introduced me to the Devon woods. All rights reserved by the authors & artist.

The poem above is from Poems of Denise Levertov: 1960-1967 (New Directions, 1983); the poem in the picture captions is from The Journal of Mythic Arts (2006); the exquisite pencil drawings are by my friend & neighbor Alan Lee, who first introduced me to the Devon woods. All rights reserved by the authors & artist.

April 20, 2016

The magic of moor and hill

"I think that in my heart I have always believed in fairies," writes Elizabeth Goudge in her autobiography, The Joy of Snow; "not fairies as seen in the picture books but nature spirits whose life is part of the wind and the flowers and the trees. Born in the West Country, and returning to it in middle life, how could I do anything else? But alas, I have never seen them.

"William Blake saw fairies, but he was a unique person, and so was a Dartmoor friend of mine who used to see them, and how I envied her! But if I did not see them I could feel how magic ran in the earth and branched in one's veins when one sat down. The stories that some of my Dartmoor friends told me would be laughed at by most people, but they were sensible persons and they did not laugh. I think that probably the one among my friends who experienced most was the one who said the least about it, Adelaide Phillpotts, Eden Phillpotts' daughter. She lived for years upon the moor and she loved it so deeply that she was not afraid to spend whole nights alone on the tors; but she is a mystic and mystics seem always unafraid. Her book The Lodestar is full of the wild spirit of the moor.

"The friend who saw fairies, when she first went to live in her cottage on the moor, was visited early in the morning by a little old woman, wearing a bonnet, who walked quietly into the kitchen where she was preparing breakfast. Friendly and smiling the old woman refused breakfast but sat down to chat. She wanted to know exactly what my friend intended to do in the garden. What flowers would she have? What vegetables? She had very bright eyes and nodded her head in approval as they talked. She seemed a happy old woman, very much at home in the kitchen, but when my friend turned away for a moment she found on looking around again that her visitor had left her. She was never seen again and when the neighbors were questioned they denied ever having seen such an old woman in the village.

"The friend who saw fairies, when she first went to live in her cottage on the moor, was visited early in the morning by a little old woman, wearing a bonnet, who walked quietly into the kitchen where she was preparing breakfast. Friendly and smiling the old woman refused breakfast but sat down to chat. She wanted to know exactly what my friend intended to do in the garden. What flowers would she have? What vegetables? She had very bright eyes and nodded her head in approval as they talked. She seemed a happy old woman, very much at home in the kitchen, but when my friend turned away for a moment she found on looking around again that her visitor had left her. She was never seen again and when the neighbors were questioned they denied ever having seen such an old woman in the village.

"Another friend was driving back to her home on the moor one summer evening when she found herself in the most beautiful wood. She had no sense of strangeness but drove through it entranced by the loveliness of the evening light shining through the trees. Coming out of the wood she found herself at home, put the car away and went about the normal business of the evening, and only gradually did she remember that her road home lay through an open stretch of moorland. There was no wood there; not now. The next day she went to see an old man who had lived all his life on the moor and told him what had happened. He nodded his head. 'I know the wood, ma'am,' he told her. 'I've been there myself. But only once. You'll not see it again. It's only once in a lifetime.' "

Although Goudge never saw fairies herself, she did have a mystical experience in Devon:

"My mother and I had a cottage in an apple orchard at the edge of a village," she explains, "and behind the cottage, between the orchard and the village, there was a steep hill. To the right, Dartmoor was visible, but otherwise the place was a little valley in the hills that had a magic of its own. There were a few other small dwellings besides our own, an old house behind a high wall, a farm and some cottages, and so strictly speaking the place was not a lonely one, and yet, because of its particular magic, it was. Especially in the early morning and especially after a snow-fall. There is something very lonely about a deep snow-fall and Devon snow, because the average rainfall is high, is almost always deep. One is walled in and cut off. The world seems very far away and the heart rejoices.

"In spring, in Devon, there is often a sudden late snow-fall taking one entirely by surprise. I remember once seeing irises and tulips with their bright heads lifted above a deep counterpane of snow, and boughs of apple blossoms sprinkled with sparkling silver. But the snowfall [on this occasion] was earlier in the year. There were only the low-growing flowers in bloom in the garden and they were all buried out of sight. There had been no wind in the night, no suggestion that the last snow of the year was falling, and when I drew the curtains early in the morning I was astonished to see the white world. And what a world! I had never seen a snow-fall so beautiful and I was out in the garden at the first possible moment. The snowclouds had dropped their whole treasure in the night and were gone. The huge empty sky was deep blue, the air sparkling and clear. The sun was rising and the tree shadows lay blue across the sparkling whiteness. The whole world was pure blue and white and it seemed that the sun had lit every crystal to a point of fire. There was a silence so absolute it seemed a living presence. And then came the singing.

"It was a solo voice, ringing out joy and praise. One would have said it was a woman's voice, only could any woman sing like that, with such simplicity and beauty? It lasted for some minutes, and then ceased, and the deep silence came back once more.

"I stayed where I was, as rooted in the snow as the trees, but there was no return of the singing and so I went back to the cottage and mechanically began the first task of the day, raking out the ashes of the dead fire and lighting a new one. The light of the flames helped me to think. None of us, in the little group of dwellings in the valley had a voice much above a sparrow's chirp. No one in the village that I knew had a voice like that. It was war-time and visitors from the outside world seldom came. Even if by some extraordinary chance some great singer had descended upon us, what would she be doing struggling down the steep lane from the village in deep snow at this hour of a cold morning? And wouldn't I have seen her? I could see both lanes from the little terrace outside the cottage and had seen no one. There were only two explanations. Either I was mad or I had heard a seraph singing. Later when I took my mother her breakfast I told her of the singing. She looked at me and, as usual, made no comment whatsoever.

"And so, for some years, I inclined to the former view and told no one else about the singing. And then, one day after the war had ended, a very sensitive and sympathetic cousin came to visit us and told me about a holiday he had had in the wilds of Argyll. He had always wanted, he said, to talk to someone who had heard the singing and at last he come upon an old crofter who could tell him about it. The old man had been alone in the hills when he heard a clear voice, unearthly and very beautiful, singing in the silence. He could see no one, he could distinguish no words in the singing and the song was one he did not know. He tried to hum the air and my cousin tried to write it down, but they neither of them made much of a job of it. 'You never heard it again?' my cousin asked and the old man said, like the old countryman who was in the wood only once, 'No, never again.'

"My cousin told this tale so beautifully that I was too awed and shy to tell him, then, about my own experience. Besides, the great paean of praise I had heard in the snow seemed at that moment a little theatrical in comparison with the soft unearthly singing in the hills of Argyll. But, some years later, I did tell him. He was very kind, and he did not doubt my sincerity, but somehow I seemed to see at the back of his mind the figure of a stout opera singer from Covent Garden who had somehow, even in war-time and deep snow, got herself hidden behind the fir trees at the corner of our Devon garden.

'It does not matter. I remember that singing every morning of my life and I greet every sunrise with the memory. The birds, who had been singing so riotously, had been chilled to silence by that snowstorm. I have decided now that she, whoever she was, sang their dawn-song for them."

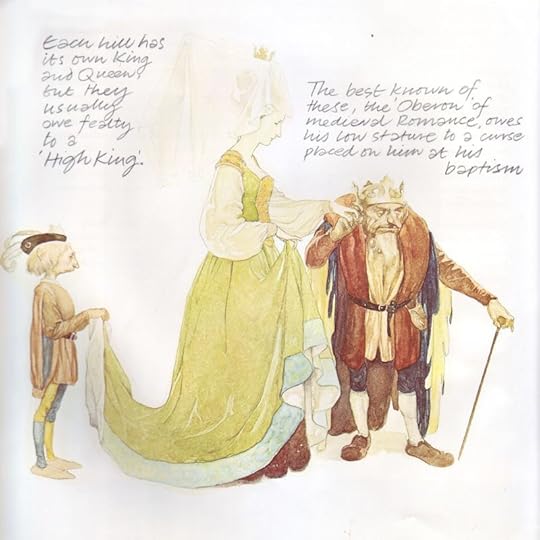

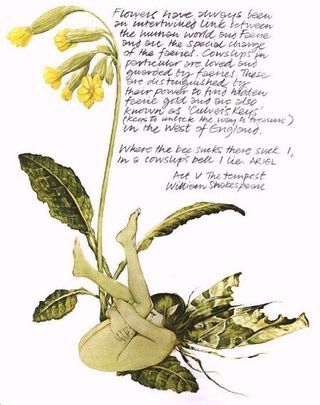

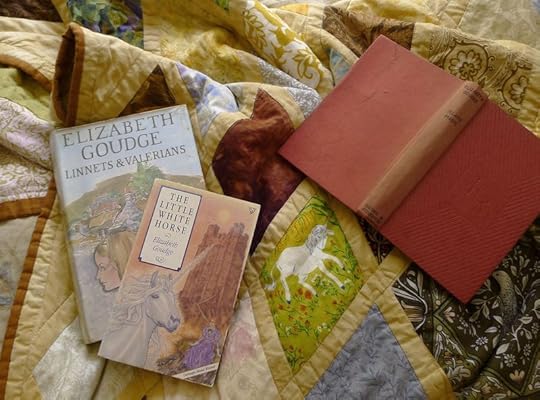

Words: The passage by Elizabeth Goudge is from The Joy of Snow: An Autobiography (Hodder & Stoughton, 1974); the poem in the picture captions is from Marrow of Flame by Dorothy Walters (Poetry Chaikhana, 2015); all rights reserved by the authors. Pictures: "King & Queen of the Faery Hill" by Alan Lee, "Cowslip Faery" by Brian Froud, and three fairy pictures by Arthur Rackham. The books in the last photograph are Linnets and Valerians, The Little White Horse, and Island Magic by Elizabeth Goudge; the quilt was made by Karen Meisner. Related posts on Devon folklore: Tales of a Half-Tamed Land, The Wild Hunt, and Following the Hare.

Words: The passage by Elizabeth Goudge is from The Joy of Snow: An Autobiography (Hodder & Stoughton, 1974); the poem in the picture captions is from Marrow of Flame by Dorothy Walters (Poetry Chaikhana, 2015); all rights reserved by the authors. Pictures: "King & Queen of the Faery Hill" by Alan Lee, "Cowslip Faery" by Brian Froud, and three fairy pictures by Arthur Rackham. The books in the last photograph are Linnets and Valerians, The Little White Horse, and Island Magic by Elizabeth Goudge; the quilt was made by Karen Meisner. Related posts on Devon folklore: Tales of a Half-Tamed Land, The Wild Hunt, and Following the Hare.

April 19, 2016

Elizabeth Goudge: A Sense of Otherness

I'm embarrassed to confess that it's only this year that I've finally read the English author Elizabeth Goudge (1900-1984), whose Little White Horse and Linnets and Valerians are now two of my favorite children's books of all time. (Oh, how I wish I'd read them as a child!)

I'm still making my way through her long list of books for adults, having paused between The White Witch and The Rosemary Tree to read her charming autobiography, The Joy of Snow. A number of her novels are set in Devon, so I shouldn't have been surprised to discover that she'd lived not far from here for a time -- in Marldon, on the other side of the moor. Close by Compton Castle, the inspiration for Moonacre Manor in The Little White Horse.

In her autobiography, Goudge describes Devon in the 1940s as "an unearthly place. The round green hills where the sheep grazed, the wooded valleys and the lanes full of wildflowers, the farms and apple orchards were all full of magic, and the birds sang in that long-ago Devon as I have never heard them singing anywhere else in the world; in the spring we used to say it sounded as though the earth itself was singing.

"The villages folded in the hills still had their white witches with their ancient wisdom," she recalls, "and even black witches were not unknown. I have never had dealings with a witch either black or white, though Francis, our village chimney-sweep, a most gentle and courteous man, was I think half-way to being a white warlock. He was skillful at protecting his pigs from being overlooked. He placed pails of water on the kitchen floor to drown the Evil Eye and nothing ever went wrong with his pigs before their inevitable and intended end.

"Black magic is a thing to vile to speak of, but many of the white witches and warlocks were wonderful people, dedicated to their work of healing. I knew the daughter of a Dartmoor white witch and she told how her mother never failed to answer a call for help. Fortified by prayer and a dram of whiskey she would go out on the coldest winter night, carrying her lantern, and tramp for miles across the moor to bring help to someone ill at a lonely farm. And she brought real help. She must have had the true charismatic gift, and perhaps too knowledge of the healing herbs.

"The father of one of my friends had a white witch in his parish in the valley of the Dart. She was growing old and she came to him one evening and asked if she might teach him her spells before she died. They must always, she said, be handed on secretly from woman to man, or from man to woman, never to a member of the witch's or warlock's own sex. 'And you, sir,' she told him, 'are the best man I know. It is to you I want to give my knowledge.'

"Patiently he tried to explain why it is best that an Anglican priest should not also be a warlock, but it was hard for her to understand. 'But they are good spells,' she kept telling him. 'I know they are,' he said, 'but I cannot use them.' She was convinced at last but she went away weeping."

In her lovely essay "Elizabeth Goudge: Glimpsing the Liminal," Kari Sperring notes:

"The most overtly magical of Goudge���s adult books is probably The White Witch, which is set against the early years of the English Civil War. The protagonist Froniga is, as the title suggests, a working witch, the daughter of a settled father and a Romani mother, and she possesses both the power to heal and the power to see the future. Yet while both are important to the plot, the book is not about her powers, but about her selfhood and character and her effect on those around her. A lesser writer would probably have taken this theme in the direction of witch trials and melodrama. Goudge uses it to examine the effects of divided politics on families and communities and the ways in which our beliefs affect others outside ourselves.

"Her characters do bad things, sometimes, and those have consequences, but she rarely writes bad people -- I can think of only one, the greedy and self-obsessed school-owner Mrs. Belling in The Rosemary Tree. Goudge was concerned not with judging others but with understanding them with compassion. In her case, that compassion is linked to her sense of otherness -- the most profound experiences of liminality her characters experience are often when they are most concerned with others than themselves."

The passage by Elizabeth Goudge is from The Joy of Snow: An Autobiography (Hodder & Stoughton, 1974). The passage by Kari Sperring is from "Elizabeth Goudge: Glimpsing the Liminal" (Strange Horizons, February 22, 2016). The poem in the picture captions is from Poems of Denise Levertov: 1960-1967 (New Directions, 1983). All rights reserved by the authors or their estates. Many thanks to Delia Sherman for urging me to read Elizabeth Goudge, and to Izzy Gahan for making sure I did so by putting Linnets and Valerians into my hands. A related post (discussing white or healing magic): In the Story Made of Dawn.

The passage by Elizabeth Goudge is from The Joy of Snow: An Autobiography (Hodder & Stoughton, 1974). The passage by Kari Sperring is from "Elizabeth Goudge: Glimpsing the Liminal" (Strange Horizons, February 22, 2016). The poem in the picture captions is from Poems of Denise Levertov: 1960-1967 (New Directions, 1983). All rights reserved by the authors or their estates. Many thanks to Delia Sherman for urging me to read Elizabeth Goudge, and to Izzy Gahan for making sure I did so by putting Linnets and Valerians into my hands. A related post (discussing white or healing magic): In the Story Made of Dawn.

April 18, 2016

From the archives: What Makes a Good Writing Day?

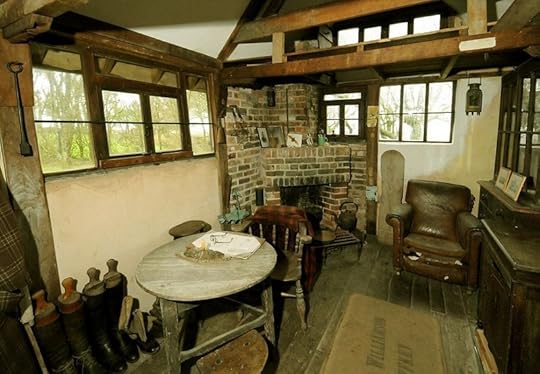

Dylan Thomas' writing hut, The Boathouse, in Laugharne, Wales

Dylan Thomas' writing hut, The Boathouse, in Laugharne, Wales

As I dig into my writing schedule again, this post (from April 2014) seems worth re-visit. My own answer to the question above is simple: Any day that I am strong enough to make it up to my studio is a good writing day. My creative needs have been pared to the bone after a month of infirmity. Give me health, time, and my sweet dog beside me, and I'm ready to go.

"A good day? I get up, I wake my teenage son up, we have breakfast, and he leaves at 8. That���s the cue for me to go to my office. My writing life has shifted slightly over the years, but what works best for me now is if I start writing immediately. I���ll check my email to make sure there���s nothing I need to deal with right away, then I read what I���ve written the day before. That jolts me into continuing. Ideally, the day before I���ve left a little bit left in the tank, so to speak. Not like Graham Greene ��� he used to write 500 words a day, and if the 500th word was in the middle of a sentence, he���d stop. I���m not that bad, but what���s really useful is to have a little left that you haven���t quite gotten down on paper. Then I can use that in the morning to get started. A lot of times, if the writing goes well, I���ll be done by 10. Sometimes I���m still working at 6. It depends on what I come up against."

"I get up around 4:30 or 5 at the latest. I usually go until I get tired, until about 9 or 10. Then I quit and monkey around. That monkeying around could be anything: research, working out, paying bills, flossing my teeth���I have a whole array of delaying behaviors that usually don���t kick in until 9 or 10. At 5 in the morning I���m too sleepy to do anything but try to think about what I was last working on. My mind is clearer. Through the day sometimes I���ll practice music. I push through the day, get my son to school. Then after dinner, 7 or 8, I���ll have a go at writing again, if I���m really deep into it.

"I can write anywhere. I was on the train this morning writing. I usually write the first few pages longhand. I used to write a lot longhand. I still write my first 20-30 pages longhand. Then I move to the computer, or I���ll type it ��� I still use a typewriter, too. I used to use a typewriter a lot more. I needed it early in my career. The computer makes you rewrite and just hit the 'insert' key. The insert key is deadly for a writer. You really have to push forward, know you���re going to discard and rewrite everything. Man, I rewrite everything. Even emails I rewrite."

Above: Hawker's Hut, built by poet Rpbert Stephen Hawker (1803-1875) near Morwenstow, Cornwall.

Below, a writer's hut built by poet Robert Duncan (1919-1988), also near Morwenstow.

"A day like today started around 4 in the morning, because often my kids wake me by yowling in their sleep. Then I���m bolt upright, wide awake, so I figure I might as well use that time in the middle of the night, so I hop up and do a bit of work. More typically I would get the kids off to school around 8:30, then I rush to my computer. I wish that what followed was actual writing. That would be bliss. But I admit that I first make my way through a fast-growing undergrowth of business....

"I know you���re supposed to do the writing first and leave the administrative stuff for later in the day, but I can���t see my way clear to do the writing until I���ve answered those wretched new emails. When I think back to when I had infinite time to write, before we had kids, I don���t think I did my best writing first thing in the morning. I need to warm up. Maybe in fact, by devoting the first hour of the day to silly business, I���m saving the better creative time for later. But sometimes the 'business' takes all day; I look up and it���s already 4, and I have to rush off to the bus stop to pick up the children."

"I don���t like getting up early, but I do because of school ��� driving my daughter to school is a good thing about my day. When I get back, either I walk/run our dog or go straight upstairs and sit down in the same chair I���ve had since 1981 ��� just the right arm height for a board to lay across and then I can sit there and write. A friend upholsters this chair every fifth year, and it is currently covered in red mohair velvet. My cousin���s quilt drapes the back of the chair. I am sort of obsessive about having things around me from my family ��� these objects pop up in the books."

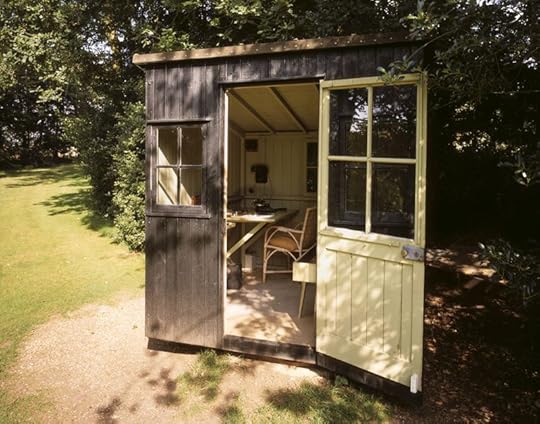

George Bernard Shaw's writing shed in Ayot St Lawrence, Hertfordshire. (It rotated to catch the best sunlight.)

George Bernard Shaw's writing shed in Ayot St Lawrence, Hertfordshire. (It rotated to catch the best sunlight.)

"The only time I have for writing is when I���m back home in England, in the house I grew up in, where all my things are, my books. Many times, I���ve got to try to get a lot of writing done in just, maybe, five days. That means setting the alarm for five o���clock. Desperately writing until breakfast, going back to write again. Always taking an hour off to spend with the dog. And in the evening I spend time with my sister ��� we own the house together and she lives in it with her family. Then I sometimes have to go back and write late into the night. It���s a very stressful way to write, high and edgy."

"Flora and I have four young children, so I write late into the night ��� the only time our home is silent. At three in the morning, I usually collapse on the narrow bed in my study, but am often woken a couple of hours later by one or both of our 3-year-old twins, who like to waddle down from their room and climb on top of me. At 8, I make pancakes for the children, then sleep again until 11. This is when the day really begins. I make myself a cup of tea, sit at my desk, phone my friends in Beijing, read for a while, then start thinking about what I am going to write."

"I can���t write every day. I���m a binger. I like to go six or seven hours at a time, without a break, then go off somewhere and drink something."

Virgina Woolf's writing shed at Monk's House in Rodmell (near Lewes), Sussex

Virgina Woolf's writing shed at Monk's House in Rodmell (near Lewes), Sussex

"I���d be lucky to have a morning routine! But let���s pretend���. I���d get up in the morning, have breakfast, have coffee, then go upstairs to the room where I write. I���d sit down and probably start transcribing from what I���d [hand]written the day before.... I don���t think there���s anything too unusual about [my study], except that it���s full of books and has two desks. On one desk there���s a computer that is not connected to the internet. On the other desk is a computer that is connected to the internet. You can see the point of that!"

"When I���m rewriting, and it���s progressing, I begin breathing audibly through my nose. I like to proofread in noisy restaurants, with my glasses off, staring close at the type. I love the feeling of sealing up a FedEx envelope ��� that soft, cool fibrous Tyvek bending around the corner of a block of page proofs ��� and sending it off. Lately, working on Traveling Sprinkler, I���ve been writing in the car, so what I see is whatever is out the windshield ��� usually leaves, other cars, fireflies. The dashboard is the desk, complete with coffee stains."

Vita Sackville-West's writing tower at Sissinghurst Castle in Kent

Vita Sackville-West's writing tower at Sissinghurst Castle in Kent

"I find that writing a first draft is very difficult and laborious. It is also often quite disappointing. It hardly ever turns out to be what I thought it was, and it usually falls quite short of the ideal I held in my mind when I began writing it. I love to rewrite, however. A first draft is really just a sketch on which I add layer and dimension and shade and nuance and color. Writing for me is largely about rewriting. It is during this process that I discover hidden meanings, connections, and possibilities that I missed the first time around. In rewriting, I hope to see the story getting closer to what my original hopes for it were.

"I write while my kids are at school and the house is quiet. I sequester myself in my office with mug of coffee and computer. I can't listen to music when I write, though I have tried. I pace a lot. Keep the shades drawn. I take brief breaks from writing, 2-3 minutes, by strumming badly on a guitar. I try to get 2���3 pages in per day. I write until about 2 p.m. when I go to get my kids, then I switch to Dad mode."

Roald Dahl's writing hut at Gipsy House in Great Missenden, Buckinghamshire

Roald Dahl's writing hut at Gipsy House in Great Missenden, Buckinghamshire

"I try to write 1000 words on a good day, about three pages. The reason for that amount, it feels right to me because most of the scenes I write are 3000-4000 words long. Not always, but on average. That means that I get 3-4 days per scene, which is good, because sometimes I���ll read it and feel ��� I feel different on different days, so it means I won���t have just one tone per scene. I have several different cracks at it.

"I���ll often be in the middle of writing and realize I don���t know what I���m writing about. For instance, today I���ve been writing a scene about a man who���s grafting apple trees. So I have to stop and look at my notes about grafting. Just now I was thinking, I still don���t really understand this. I need to order a book at the British Library and go and read it tomorrow. That���s what happens as I go. So what I���ll do is write a basic part of the scene, but for the grafting bit���I���ll put down three stars. Three stars in a manuscript for me means there���s something missing, I have to go back and fill it out. I don���t want it to stop my writing flow, but I���ll leave it aside and do the rest of the scene without it, come back and fill it in later. That���s a good interruption. A bad interruption is when I can���t focus and I wind up fiddling around online, having lunch with a friend, or something like that. What I���m aiming for is that concentrated time of focusing."

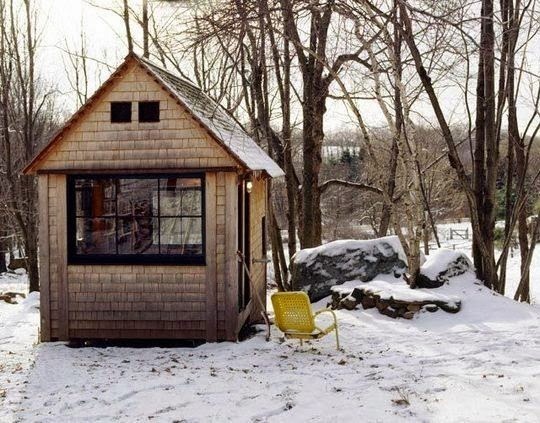

The writing hut in North Devon where naturalist Henry William Williamson

wrote Tarka the Otter.

The writing hut in North Devon where naturalist Henry William Williamson

wrote Tarka the Otter.

"I know many writers who try to hit a set word count every day," Russell continues, "but for me, time spent inside a fictional world tends to be a better measure of a productive writing day. I think I���m fairly generative as a writer, I can produce a lot of words, but volume is not the best metric for me. It���s more a question of, did I write for four or five hours of focused time, when I did not leave my desk, didn���t find some distraction to take me out of the world of the story? Was I able to stay put and commit to putting words down on the page, without deciding mid-sentence that it���s more important to check my email, or 'research' some question online, or clean out the science fair projects in the back for my freezer?

"For me, a good writing day is when I can move forward inside a story, because I take so much pleasure in tinkering with sentences that I often have to fight my own impulse to dither and revise in order to keep the momentum of the narrative going. So if I can move in a linear way through the story, and stay zipped inside the story, not jinx myself with despair or frustration or over-confidence or self-consciousness, and be basically okay with not-knowing what is going to happen from one sentence to the next, that���s a great writing day. Writers are such excellent self-saboteurs, though. I swear, I can hijack my own writing day in a hundred ways ��� I can eject myself from a story because I���ve decided it���s 'going good.' There���s this excruciating aspect of joy, I don���t know if you���ve ever experienced this, where you almost want to interrupt it. For me, the experience of losing myself in a character can feel intolerably wonderful. So I���ve decided that the trick is just to keep after it for several hours, regardless of your own vacillating assessment of how the writing is going....

"Showing up and staying present is a good writing day."

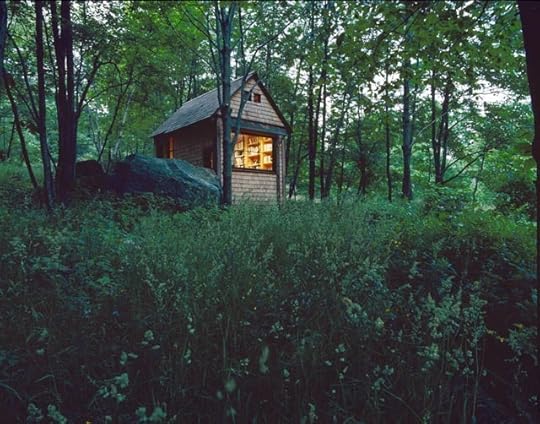

Michael Pollan's wrote a book about building this writing hut: A Place of My Own: The Architecture of Daydreams.

Michael Pollan's wrote a book about building this writing hut: A Place of My Own: The Architecture of Daydreams.

"On a shelf above my computer are five letters that spell out W-R-I-T-E. Just in case I forget why I���m there."

Tunes for a Monday Morning

It's a quiet, misty morning here on Dartmoor, too chilly to sit outdoors for long, but there are lambs in the fields, ponies on the Commons and primroses all along the winding path up to my studio...so it must be spring, and the warmer days we've been longing for will surely come soon.

This week's music starts with The Furrow Collective, a group of four fine folk musicians who are also well known for their solo work: Emily Portman (from Glastonbury), Lucy Farrell (from Maidstone), Alasdair Roberts and Rachel Newton (both from Glasgow).

Above, "I'd Rather Be Tending my Sheep," a West Country folksong from the collective's first album, At Our Next Meeting (2014). This one is for Delia Sherman (and all you other knitters out there), and for Cynthia Rose on her sheep farm in Wiltshire.

Below, "Many's the Nights Rest," a lovely informal performance filmed just last month. The song can be found on The Furrow Collective's new EP, Wild Hog in the Woods.

"���I stumbled across ���Many���s the Night���s Rest��� in a journal of the Folk-Song Society from 1905," says Portman, "and was struck by the resolute tone of the chorus ���Many���s the night���s rest you���ve robbed me of, but you never shall do it again���. It���s Roud No. 293 ��� a version of ���Bonny Boy��� and Lucy Broadwood collected it in 1901 from a Henry Hills in Sussex. I imagine this song representing a woman finally washing her hands of her cheating boyfriend and moving on, though you could draw other, darker conclusions depending on your temperament."

Above, "Green Gravel," a deliciously dark children's song recorded by Fay Hield, who is both a folk singer and lecturer in Ethnomusicology at the University of Sheffield. It comes from her latest album, Old Adam (2015), which I highly recommend -- along with Hield's excellent Full English project, and her 2014 TED Talk, "Why Aren't We All Folk Singers?"

"Green Gravel" is associated with children's games in Britain and North America; this particular version comes from Alice Bertha Gomme's The Traditional Games of England, Scotland, and Ireland. "The song has links to burial ceremonies," Alex Gallacher explains, "with green gravel representing the newly turned grave; though there is no suggestion this rhyme was performed at burials, more that children took the ideas of life, love and death into their own sphere."

To end with, a beautiful rendition of "The Grey Selchie" (Child Ballad No. 113) by Maz O'Connor, from Barrow-in-Furness in Cumbria. This new video, released a few weeks ago, was filmed for The Blue Room Sessions in the Netherlands. O'Connor has released three lovely albums of original and traditional tunes, the latest of which is The Longing Kind (2016).

The first two photographs above were taken by my friend Helen Mason. The last one is mine. A related post:

The Folklore of Sheep. Previous music by Maz O'Connor here.

April 15, 2016

From the archives: The Broader Conversation

On a witchy and misty Dartmoor day, winding through the narrow lanes near Hound Tor, Wendy Froud and I are stopped by three cows. "The Three Fates," Wendy says as she breaks the car. The cows approach with deliberate steps, as if with a message they mean to deliver. They are big, gentle, remarkably graceful; too large for the fairy cattle of Devon folklore but holding their own bovine enchantment. In the moments of silence that pass between us, the moor, perhaps all the world, stands still....

Then they turn as one towards Manaton, leaving as purposefully as they'd come. We hold the silence until they are gone. Goodbye, lovely ladies, goodbye.

"All things have the capacity for speech," writes David Abram (in Becoming Animal), "all beings have the ability to communicate something of themselves to other beings. Indeed, what is perception if not the experience of this gregarious, communicative power of things, wherein even obstensibly 'inert' objects radiate out of themselves, conveying their shapes, hues, and rhythms to other beings and to us, influencing and informing our breathing bodies though we stand far apart from those things? Not just animals and plants, then, but tumbling waterfalls and dry riverbeds...

"... gusts of wind, compost piles and cumulus clouds, freshly painted houses (as well as houses abandoned and sometimes haunted), rusting automobiles, feathers, granite cliffs and grains of sand, tax forms, dormant volcanoes, bays and bayous made wretched by pollutants, snowdrifts, shed antlers, diamonds, and daikon radishes, all are expressive, sometimes eloquent and hence participant in the mystery of language. Our own chatter erupts in response to the abundant articulations of the world: human speech is simply our part of a much broader conversation.

"It follows that the myriad things are also listening, or attending, to various signs and gestures around them. Indeed, when we are at ease in our animal flesh, we will sometimes feel we are being listened to, or sensed, by the earthly surroundings. And so we take deeper care with our speaking, mindful that our sounds may carry more than a merely human meaning and resonance. This care -- this full-bodied alertness -- is the ancient, ancestral source of all word magic. It is the practice of attention to the uncanny power that lives in our spoken phrases to touch and sometimes transform the tenor of the world's unfolding."

The passage by David Abram is from Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology (Pantheon, 2010); the poem in the picture captions is from The Writer's Almanac (Oct. 7, 2005); all rights reserved by the authors. This post first appeared on Myth & Moor in 2012.

The passage by David Abram is from Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology (Pantheon, 2010); the poem in the picture captions is from The Writer's Almanac (Oct. 7, 2005); all rights reserved by the authors. This post first appeared on Myth & Moor in 2012.

April 13, 2016

Relationship and reciprocity

"When did human beings forget their cousins the creatures?" asks Priscilla Stuckey in Kissed by a Fox, which I found myself re-reading recently. "When did we fail to remember that the web of life is a delicate one, requiring attention and care?

"Some point to the rise of agriculture ten thousand years ago. Ecologist Paul Shepard suggests that domesticating plants and animals led us to turn 'from finding to making,' from taking our chances with nature to manipulating nature. Others say that when people gathered into cities and built urban centers we became increasingly separated from the natural world. Environmental historian J. Donald Hughes writes that the urban revolution meant 'the great divorce of culture and  nature' wherever it took place on the planet. Still others say that literacy trained people away from intimate connections with the more-than-human world. Philosopher Eric Havelock observed that when people no longer had to 'story' their experiences, as they do in oral societies, telling tales of characters and relationships, they shifted to considering others as things rather than persons. Cultural ecologist David Abram emphasizes that relying on the printed word changes our ways of perceiving: instead of listening to breezes, watching clouds, or feeling our way along animal tracks -- all practices to cultivate intimacy -- we allow our senses to dim, except for one particular way of using our eyes.

nature' wherever it took place on the planet. Still others say that literacy trained people away from intimate connections with the more-than-human world. Philosopher Eric Havelock observed that when people no longer had to 'story' their experiences, as they do in oral societies, telling tales of characters and relationships, they shifted to considering others as things rather than persons. Cultural ecologist David Abram emphasizes that relying on the printed word changes our ways of perceiving: instead of listening to breezes, watching clouds, or feeling our way along animal tracks -- all practices to cultivate intimacy -- we allow our senses to dim, except for one particular way of using our eyes.

"While there is truth in all these analyses, I want to point to something at once simpler and more sweeping. I think we forget our cousins the creatures when we forget each other. When we retreat from caring for the human community, we lose regard for the more-than-human one as well. And the opposite is just as true: when we fall out of relationship with the natural world, we lose interest in helping one another thrive.

"For this is the bottom line of survival: it depends on our relationships with others. Though the land-community survived for millions of years without humans, we cannot survive without the land community. We are dependent for our day-to-day survival, our very existence, on billions of nonhuman others. And we are dependent in equally complex ways on one another."

We are indeed.

"Caught up in a mass of abstractions," writes David Abram, "our attention hypnotized by a host of human-made technologies that only reflect us back to ourselves, it is all too easy for us to forget our carnal inherence in a more-than-human matrix of sensations and sensibilities. Our bodies have formed themselves in delicate reciprocity with the manifold textures, sounds, and shapes of an animate earth -- our eyes have evolved in subtle interaction with other eyes, as our ears are attuned by their very structure to the howling of wolves and the honking of geese. To shut ourselves off from these other voices, to continue by our lifestyles to condemn these other sensibilities to the oblivion of extinction, is to rob our own senses of their integrity, and to rob our minds of their coherence. We are human only in contact, and conviviality, with what is not human."

The art today is by Canadian sculptor Ellen Jewett. Born in Ontario and "raised among newts and snails," she studied Anthropology and Fine Art at McMaster University, and now creates surrealistic, biophilic works in clay from her studio on Vancouver Island.

"Plants and animals have always been the surface on which humans have etched the foundations of culture, sustenance, and identity," she says. "For myself, natural forms are a continual source of fascination and deep aesthetic pleasure. At first glance my work explores the more modern prosaic concept of nature: a source of serene nostalgia balanced with the more visceral experience of 'wildness' as remarkably alien and indifferent. Upon closer inspection of each 'creature' the viewer may discover a frieze on which themes as familiar as domestication and as abrasive as domination fall into sharp relief. These qualities are not only present in the final work but are fleshed out in the process of building. Each sculpture is constructed using an additive technique, layered from inside to out by an accumulation of innumerable tiny components. Many of these components are microcosmic representations of plants, animals and objects. Some are beautiful, some are grotesque and some are fantastical. The singularity of each sculpture is the sum total of its small narrative structures.

"Over time I find my sculptures are evolving to be of greater emotional presence by using less physical substance: I subtract more and more to increase the negative space. The element of weight, which has always seemed so fundamentally tied to the medium of sculpture, is stripped away and the laws of gravity are no longer in full effect. In reading the stories contained in each piece we are forced to acknowledge their emotional gravity cloaked as it is in the light, the feminine, the fragile, and the unknowable."

The passage by Priscilla Stuckey is from Kissed by a Fox & Other Stories of Friendship in Nature (Counterpoint, 2012); the passage by David Abram is from The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception & Language in a More-Than-Human World (Vintage, 1997). Both are highly recommended. All rights to the text and art above reserved by the authors and artist.

The passage by Priscilla Stuckey is from Kissed by a Fox & Other Stories of Friendship in Nature (Counterpoint, 2012); the passage by David Abram is from The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception & Language in a More-Than-Human World (Vintage, 1997). Both are highly recommended. All rights to the text and art above reserved by the authors and artist.

Every illness is narrative

One of the strange things about a long-term medical condition is the abruptness with which it can overturn your life. Most of the time it simmers quietly in the background, folded into the rhythm of the days, time-consuming and annoying perhaps, but also familiar, under control. That control is entirely illusory, however, for bodies are complicated things and don't always act in the prescribed ways that medical textbooks say they should. And when they don't, there isn't always a clear and demonstrable reason why. One day you're just like everyone else: doing your work, paying your bills, making plans as though the future is ordered and predictable; and the next day you're flat on your back. Again. Feeling like Charlie Brown the umpteenth time Lucy pulls the damn football away.

Why, you wail, is this happening again? You can blame yourself, you can blame your doctors, you can blame the Man in the Moon if you want to, but the desire to place blame, to find a reason, is a desire to maintain the illusion of control and to make life predictable once more. If I do X, then I'll stay healthy. If I don't do Y, then getting sick is all my fault. But life is not a straight-forward equation; it is random, messy, surprising and confounding. You can fret, fume, cry, and tie yourself in knots trying to determine where you went wrong. Or you can give yourself over to Mystery, and turn your energy towards healing.

"In the secular world of modern medicine," writes Kat Duff, "we try desperately to rescue ourselves from the grasp of the Unknowable. Doctors have supplanted the gods, deciding when life begins and ends, working miracles, and taking credit for their successes. This aura of divinity that surrounds the medical profession in our society, and the extraordinary expectations that come with it, is the source of much pain and frustration for doctor and patient alike, especially when cures are not forthcoming....

"The sense of diminishment we often experience in the grasp of the Unknoweable, the face of the uncurable, probably has something to offer us from a spiritual perspective, but in the secular world of [modern] America, it is without meaning and so intolerable. That is why the first commandment in illness is to get well. Sick people are under tremendous pressure, from themselves and from others, to overcome their ailments, and return to life as usual in our fast-paced, production-oriented world."

The pressure to get well.

We all know that pressure -- and, as Duff makes clear, it comes from within us just as much as it comes from the expectations and norms of modern society. It's hard to reconcile the slow, gentle rhythms that deep healing processes demand with the pace of life going on all around us: our families, friends, and colleagues whizzing by us in the fast lane, a blur of motion. Yet there is much to be learned from the fallow time and enforced solitude of illness; from those hazy, sweat-soaked, fever-dream days when the mind, like the body, is cut off from its usual pathways and preoccupations. Illness strips us of the things we believe to be central to our identity: our daily tasks, our creative work, our usual roles in family and community. What's left is the naked, vulnerable Self who lies buried beneath these things: the person we are, not the social construct we build, and that person is worth knowing.

In the aftermath of her cancer surgery, Rebecca Solnit observed:

"There is a serenity in illness that takes away all the need to do and makes just being enough. In that state I've only been in before with severe flu, there is no boredom, no restlessness, no thinking about what should be done or has been done. You are elsewhere than consciousness, than everyday life, than the usual bodily awareness and social engagement. We call it doing nothing or resting: the conscious mind does little but the body works furiously, under cover of stillness, to rebuild, rewire, recharge."

A major illness or injury, she continues, "is a rupture that invites you to rethink, to restart, to review what matters. It's a reminder that your time is finite and not to be wasted, and in breaking you from the past it offers the possibility of starting fresh. An illness is many kinds of rupture from which you have to stitch back a storyline of where you're heading and what it means. Every illness is narrative. There are the epics in which you ultimately triumph over what afflicts you and return for awhile to your illusory autonomy, and the tragedies, in which the illness will ultimately triumph over you and take you away into the unknown that is death, and the two are often impossible to tell apart until they resolve.

"Then there are the enigmatic illness whose prognosis is uncertain, in which well-being comes and goes unpredictably, with the difficulty of a story without a plot, or an unfathomable one. Doctors are forever being implored and pressured to read the future from the medical evidence to the present, to confirm the story, but early on they learn that rules are rubbery: the near-thriving suddenly collapse, the person at death's door travels all the way back to rejoin the living, and the time line of death and likelihood of recovery remain unforeseeable."

The ups and downs of such illnesses, in other words, remain a Mystery.

Although I spent the last month confined to bed, watching the world through window glass, I was simultaneously making a long journey: from the land of the well to the sick and back again. It's a journey we all make sooner or later, for as Susan Sontag famously said: "Illness is the night side of life, a more onerous citizenship. Everyone who is born holds dual citizenship, in the kingdom of the well and the kingdom of the sick. Although we all prefer to use the good passport, sooner or later each of us is obliged, at least for a spell, to identify ourselves as citizens of that other place."

Books, like the faithful Hound beside me, have been my boon companions on the journey: volumes grown thick with scraps of paper and margin notes pencilled in a shaky hand, marking passages I'll return to here on Myth & Moor in the days and weeks ahead.

Right now, however, I'm still in that liminal space between one world and another: between bed and studio, sickness and health, winter's end and the approach of spring. I haven't fully transitioned back to normal daily life and I know (from having made this passage all too often) that the transitory process should not be rushed. Released back into the world, everything is strange, fresh, and remarkable, undulled by familiarity. The sunlight shimmers, the woodland cries its welcome, the hillside hums with a numinous enchantment. And what better state can there be for a fantasy writer to work in?

Even illness has its gifts.

The passage above by Kat Duff is from

The Alchemy of Illness

(Bell Tower, 1993), the passage by Rebecca Solnit is from The Far Away Nearby (Viking & Granta, 2013), and the Susan Sontag quote is from Illness As Metaphor (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1978). All three are highly recommended. The poem in the picture captions is from New Ohio Review (No. 9, Spring, 2011). All rights reserved by the authors. Photographs: Some of the books I've been reading (or re-reading) in the weeks of crisis and return; plus the faithful Hound and bedside flowers. The beautiful quilt was made by Karen Meisner. Some related posts: Stories are Medicine, the four "On Illness" posts beginning with In a Dark Wood, and Books, the Beast, & Me.

The passage above by Kat Duff is from

The Alchemy of Illness

(Bell Tower, 1993), the passage by Rebecca Solnit is from The Far Away Nearby (Viking & Granta, 2013), and the Susan Sontag quote is from Illness As Metaphor (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1978). All three are highly recommended. The poem in the picture captions is from New Ohio Review (No. 9, Spring, 2011). All rights reserved by the authors. Photographs: Some of the books I've been reading (or re-reading) in the weeks of crisis and return; plus the faithful Hound and bedside flowers. The beautiful quilt was made by Karen Meisner. Some related posts: Stories are Medicine, the four "On Illness" posts beginning with In a Dark Wood, and Books, the Beast, & Me.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 708 followers