Terri Windling's Blog, page 114

June 10, 2016

Coffee, cows, the writing craft, and the larger reality

To end a week reflecting on social/environmental/political concerns in the making of art and the writing of fantasy, I'd like to turn to the words of Ursula K. Le Guin, who has been walking this ground for many years, and building masterworks upon it.

From "A Few Words to a Young Writer":

"Socrates said, 'The misuse of language induces evil in the soul.' He wasn't talking about grammar. To misuse language is to use it the way politicians and advertisers do, for profit, without taking responsibility for what the words mean. Language used as a means to get power or make money goes wrong: it lies. Language used as an end in itself, to sing a poem or tell a story, goes right, goes towards the truth.

"A writer is a person who cares what words mean, what they say, how they say it. Writers know words are their way towards truth and freedom, and so they use them with care, with thought, with fear, with delight. By using words well they strengthen their souls. Story-tellers and poets spend their lives learning that skill and art of using words well. And their words make the souls of their readers stronger, brighter, deeper."

From Steering the Craft: A Twenty-First-Century Guide to Sailing the Sea of Story:

"To make something well is to give yourself to it, to seek wholeness, to follow spirit. To learn to make something well can take your whole life."

From her National Book Award acceptance speech, November 2014:

''Hard times are coming, when we���ll be wanting the voices of writers who can see alternatives to how we live now, can see through our fear-stricken society and its obsessive technologies to other ways of being, and even imagine real grounds for hope. We���ll need writers who can remember freedom -- poets, visionaries -- realists of a larger reality.''

Go here for a podcast in which Ursula discusses language, writing, and the new, updated edition of Steering the Craft.

Pictures above: Morning coffee beside the stream (before the rain began), with Tilly on one side of our favorite oak and bovine neighbors on the other.

Pictures above: Morning coffee beside the stream (before the rain began), with Tilly on one side of our favorite oak and bovine neighbors on the other.

June 8, 2016

Art, activism, and the soil we grow in

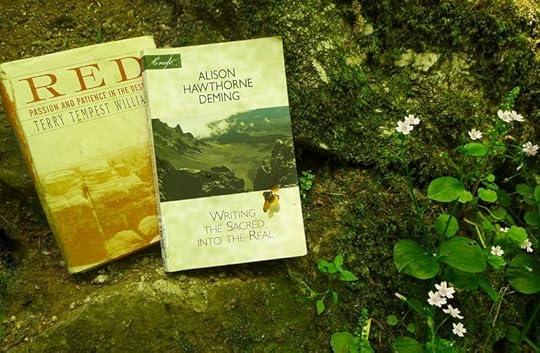

Following on from yesterday's post, here's another insightful passage from Writing the Sacred Into the Real by Alison Hawthorne Deming:

"In 1997, I was asked by the Orion Society to lead a conversation at the colloquium in honor of Gary Snyder when he received the John Hay Award for his writing and activism. My assignment was to address the question, Does activism compromise one's art? The question was very American, as Snyder pointed out. In [continental] Europe and Asia, an artist is a public person -- seeing the responsibility to use some of his or her skills on behalf of society. I answered the question by saying, Yes, of course compromise occurs. The work of activism exhausts us and makes us grieve; it takes us from our studios; it makes us scholars, negotiators, combatants, administrators, and business heads when we would prefer to be makers, dreamers, healers, and dancers. And if art is made to serve our activism, it can lose its elemental engagement with the unknown; its freedom to be outrageous, obscure, absurd, and wild; its need to speak the truth as it cannot be spoken in political discourse.

"In 1997, I was asked by the Orion Society to lead a conversation at the colloquium in honor of Gary Snyder when he received the John Hay Award for his writing and activism. My assignment was to address the question, Does activism compromise one's art? The question was very American, as Snyder pointed out. In [continental] Europe and Asia, an artist is a public person -- seeing the responsibility to use some of his or her skills on behalf of society. I answered the question by saying, Yes, of course compromise occurs. The work of activism exhausts us and makes us grieve; it takes us from our studios; it makes us scholars, negotiators, combatants, administrators, and business heads when we would prefer to be makers, dreamers, healers, and dancers. And if art is made to serve our activism, it can lose its elemental engagement with the unknown; its freedom to be outrageous, obscure, absurd, and wild; its need to speak the truth as it cannot be spoken in political discourse.

"Asking this question is like asking, Does culture compromise nature? Does love compromise solitude? Does eating compromise prayer? Does the mountain compromise the sky? All of these are relationships of complementarity, correspondence, call-and-response, the mutualistic whole of existence.

"Gathering in Snyder's home place, listening to stories of the Yuba Watershed Institute and the building of the Ring-of-Bone Zendo, and celebrating the poet's work provided a lesson in how radical an act it is in this culture to live a life devoted to something other than capitalism. Yes, we all participate in it. Yes, we are all complicit in environmental degradation and overconsumption simply because of our position in the global food chain. But we can make life choices that nuture more meaningful and sustainable relationships. To live a life devoted to art, to spiritual practice, to service to one's community and ecosystem, restores faith in our collective human enterprise. Work on the culture is work on the self.

"Art can serve activism by teaching an attentiveness to existence and by enriching the culture in which our roots are set down. Culture is both the crop we grow and the soil in which we grow it. And human culture is the most powerful evolutionary force on Earth these days. The grief we feel at abuses of human power is the first positive step at transforming that power for the good. Legislation, information, and instruction cannot effect change at this emotional level -- though they play a significant role. Art is necessary because it gives us a new way of thinking and speaking, shows us what we are and what we have been blind to, and gives us new language and forms in which to see ourselves. To effect profound cultural change requires that we educate ourselves about our own interior wildness that has led us into such a hostile relationship with the forces that sustain us. Work on the self is work on the culture."

The images in this post are by Canadian artist Kristin Bjornerud, who was born in Alberta, studied at the Universities of Lethbridge and Saskatchewan, and is now based in Montreal.

"My watercolour and gouache paintings," she writes, "explore contemporary political themes, ecological motifs, and personal narratives through the lens of folktales, dreams, and magical realism. In these delicately painted tableaus, a world is revealed wherein dream logic pervades, where women swim with narwhals and vivify hand-knit fauna. These eccentric landscapes are uncanny projections of a possible world where familiar activities are imbued with a mythic quality while, at the same time, extraordinary deeds are carried out with unruffled poise by proud, unconventional heroines.

"My watercolour and gouache paintings," she writes, "explore contemporary political themes, ecological motifs, and personal narratives through the lens of folktales, dreams, and magical realism. In these delicately painted tableaus, a world is revealed wherein dream logic pervades, where women swim with narwhals and vivify hand-knit fauna. These eccentric landscapes are uncanny projections of a possible world where familiar activities are imbued with a mythic quality while, at the same time, extraordinary deeds are carried out with unruffled poise by proud, unconventional heroines.

"My aim is to create contemporary fairy tales that act as a medium through which we may consider our ethical obligations to the natural world and to each other. Retelling and reshaping stories helps us to understand how we are entangled, where we meet, and how our differences may be viewed as disguises of our sameness."

The passage by Alison Hawthorne Deming above is from Writing the Sacred Into the Real (The Credo Series, Milkweed Editions, 20010. All rights to the text and imagery above reserved by the author and artist. A previous post on Writing the Sacred Into the Real: "Lines for Winter."

The passage by Alison Hawthorne Deming above is from Writing the Sacred Into the Real (The Credo Series, Milkweed Editions, 20010. All rights to the text and imagery above reserved by the author and artist. A previous post on Writing the Sacred Into the Real: "Lines for Winter."

Giving voice to the voiceless

For those of us who care about what's going on in the world politically and environmentally, it can be a struggle to understand how this relates to making art, particularly if we work in mythic, nonrealist forms far removed from the increasingly worrisome headlines of the day.

In her lovely little book Writing the Sacred Into the Real, American poet and essayist Alison Hawthorne Deming discusses the tension between art and activism in her work; and although she's speaking in terms of poetry here, her insights can be applied to the writing of fantasy as well...at least to the kind of poetic, deeply mythic fantasy that rarely appears on the bestsellers list, by writers like Alan Garner, Robert Holdstock, Patricia McKillip, Elizabeth Knox, and so many others (including some of you reading this now).

Writing poetry, says Deming, "is an act of dissent in at least three ways: economically, because the poet labors to make a thing that will never be worth money; temporally, because the poem is an argument with the erosive passage of time; and politically, because in an age that values aggregate data, poetry -- all true art -- insists on the passionate importance of the individual.

"The turning inwards to explore the world through the lens of subject does not necessarily mean a turning away from the world. Denise Levertov turned Wordsworth's lament inside out by writing 'the world is / not with us enough.' Her poetics insisted upon both the lyric impulse -- the song of the soul singing in the present moment -- and the political impulse -- the cry for social justice and peace."

Though Levertov's poetic spirit infuses Deming's, trying to honor these two opposing impulses, she says, "can cause a chronic psychic whiplash. Just when attention is focused on the inner excitement of consciousness, the world calls you a solipsist and demands your attention. Try to tell the world what you think of it, and consciousness will insist that it -- consciousness itself -- is the only thing you can know in its passing, so you had better take heed, right now. But Levertov found balance in the meditative mode, which asks for both introspection and realism -- or as Muriel Rukeyser suggested, the meeting of consciousness and the world -- and she wove a tenuous unity out of condradictions. I take that lesson to heart.

"For me," she explains, "the natural world in all its evolutionary splendor is a revelation of the divine -- the inviolable matrix of cause and effect that reveals itself to us in what we cannot control or manipulate no matter how pervasive our meddling. This is the reason that our technological mastery of nature will always remain flawed. The matrix is more complex than our intelligence. We may control a part, but the whole body of nature must incorporate the change, and we are not capable of anticipating how it will do so. We will always be humble before nature, even as we destroy it. And to diminish nature beyond its capacity to restore itself, as our culture seems perversely bent to do, is to desecrate the sacred force of Earth to which we owe a gentler hand. That the diminishment has been caused by abuses of human power makes this issue political. Why should one species have the right to deprive so many others of their biological heritage and future? To write about nature, to record the magnificence, cruelty, and mysteriousness of it, is then an act both spiritual and political.

"Italo Calvino describes how literature's interior explorations can be put to political use: 'Literature is necessary to politics above all when it gives voice to whatever is without a voice, when it gives a name to what as yet has no name, especially to what the politics of language excludes or attempts to exclude. I mean aspects, situations, and languages both of the outer and of the inner world, the tendencies repressed both in individuals and in society. Literature is like an ear that can hear things beyond the understanding of the language of politics; it is like an eye that can see beyond the color spectrum perceived by politics. Simply because of the solitary individualism of his work, the writer may happen to explore areas that no one has explored before, within himself or outside, and to make discoveries that sooner or later turn out to be vital areas of collective awareness.'

Deming continues: "My early interests as a poet were to understand the modernist and postmodernist traditions, and to locate myself within their trajectory. And these conditions set aesthetic concerns in opposition to social ones -- the artist as rebel, dissident, and iconoclast. But the wellspring for that inconoclastic energy was for me the belief that art can be a voice of moral and spiritual empathy, an antidote to the cold-hearted self-interest that drives so much of American culture. I have a hunger / for harmony that I feel with dissent.

"Realizing the importance of nature as a subject was a slow process of conversion for me. Way stations along the route: hearing Richard Nelson speak about writing his beautiful meditative book The Island Within after decades of working as a cultural anthropologist and his explaining that he had decided to write about what he loved; hearing Stanley Kunitz say to Fellows at the Work Center that originality in art could come only from what was unique in one's character and experience, not from manipulating the surface of one's technique; remembering that all my life I have hungered for wild places and all of my life wild places have fed me and that this is central to who I am and would have to inform my aesthetic decisions; sitting up in bed as a child, darkness surrounding me, and staring at the mystery of how I came to exist in the world in this body, and how it is an impossible fact that I will one day stop being here; assessing what I most love about being here and what I would like to understand and contribute before leaving..."

"I write to make peace with the things I cannot control, " says fellow writer and activist Terry Tempest Williams. "I write to create red in a world that often appears black and white. I write to discover. I write to uncover. I write to meet my ghosts. I write to begin a dialogue. I write to imagine things differently and in imagining things differently perhaps the world will change. I write to honor beauty. I write to correspond with my friends. I write as a daily act of improvisation. I write because it creates my composure. I write against power and for democracy. I write myself out of my nightmares and into my dreams. I write in a solitude born out of community. I write to the questions that shatter my sleep. I write to the answers that keep me complacent. I write to remember. I write to forget.... I write as ritual. I write because I am not employable. I write out of my inconsistencies. I write because then I do not have to speak. I write with the colors of memory. I write as a witness to what I have seen. I write as a witness to what I imagine.... I write because it is dangerous, a bloody risk, like love, to form the words, to say the words, to touch the source, to be touched, to reveal how vulnerable we are, how transient we are. I write as though I am whispering in the ear of the one I love."

Can we write fantasy and mythic fiction in this manner as well? Fantasy as ritual, fantasy as witness, fantasy that gives "voice to the voiceless" -- including the whispering more-than-human voices of the land we live on? I believe we can. Or at least I intend to try, and to see where it might take me....

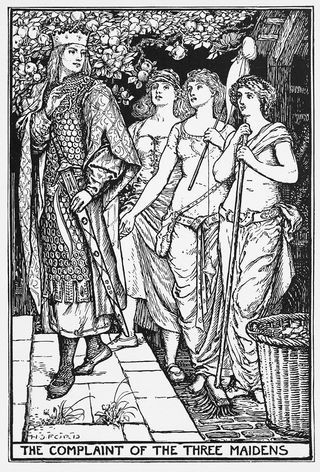

The passage by Alison Hawthorne Deming above is from Writing the Sacred Into the Real (The Credo Series, Milkweed Editions, 2010). The passage by Terry Tempest Williams is from Red: Passion and Patience in the Desert (Pantheon, 2001). The poem by Denise Levetov in the picture captions is from O Taste and See (New Directions, 1964). All rights reserved by the authors. The illustration is by Honore Appleton (1879-1951).

The passage by Alison Hawthorne Deming above is from Writing the Sacred Into the Real (The Credo Series, Milkweed Editions, 2010). The passage by Terry Tempest Williams is from Red: Passion and Patience in the Desert (Pantheon, 2001). The poem by Denise Levetov in the picture captions is from O Taste and See (New Directions, 1964). All rights reserved by the authors. The illustration is by Honore Appleton (1879-1951).

June 7, 2016

Myth & Moor update

This blog's server, Typepad, was down all morning, so I missed my window for posting today. The server problem seems to be fixed now, and as long as it stays fixed I'll be back on a regular posting schedule tomorrow morning. See you then!

June 5, 2016

Tunes for a Monday Morning

This week starts off with American folk and roots music from Sarah Jarosz, who at the age of 25 is already one of the top mandolin and banjo players in the county. Her fourth album is due out later this month, and it's reputed to be very good indeed.

Above, Jarosz performs "Annabelle Lee," an adaptation of the poem by Edgar Allan Poe, filmed in Scotland in 2013 for the BBC's TransAtlantic Sessions. The song is from her second album, Follow Me Down (2011).

Below, she performs her song "Build Me Up From Bones," accompanied by Alex Hargreaves on violin and Nathaniel Smith on cello (2014).

In addition to her solo work, Jarosz also tours as a member of the trio I'm With Her, along with Sara Watkins (of Nickel Creek) and Aoife O'Donovan (of Crooked Still).

Above, the group's rendition of "A Hundred Miles" by Gillian Welch, performed for A Prairie Home Companion last autumn, backed up by The Jeremy Kittel Trio.

Below, "Shadow Blues" by Laura Veirs, also performed for A Prairie Home Companion.

Edgar Allan Poe illustrations by Edmund Dulac (1882-1953)

June 2, 2016

Once upon a time....

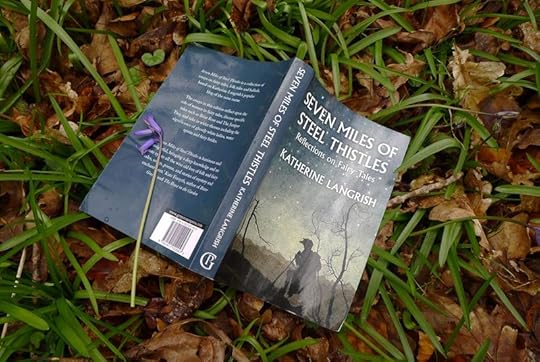

One of the very best books I've read this year is Seven Miles of Steel Thistles: Reflections on Fairy Tales by Katherine Langrish, the author of West of the Moon and other excellent works of myth-based fantasy for children.

Now while I might seem biased because Katherine is a family friend (her daughter and ours have been best friends for many years), in truth I am sharply opinionated when it comes to books about folklore and fairy tales; I was mentored in the field by Jane Yolen, after all, which sets the bar pretty damn high. Thus it is no small praise to say that Seven Miles of Steel Thistles is an essential book for practioners of mythic arts: insightful, reliable, packed with information...and thoroughly enchanting.

Now while I might seem biased because Katherine is a family friend (her daughter and ours have been best friends for many years), in truth I am sharply opinionated when it comes to books about folklore and fairy tales; I was mentored in the field by Jane Yolen, after all, which sets the bar pretty damn high. Thus it is no small praise to say that Seven Miles of Steel Thistles is an essential book for practioners of mythic arts: insightful, reliable, packed with information...and thoroughly enchanting.

"As a child I was usually deep in a book," Kath writes in the volume's introduction, "and as often as not, it would be full of fairy tales or myths and legends from around the world. I remember choosing the Norse myths for a school project, retelling and illustrating stories about Thor, Odin and Loki. I read the tales of King Arthur, I read stories from the Arabian Knights. And gradually, I hardly know how, I became aware that grown-ups made distinctions between these, to me, very similar genres. Some were taken more seriously than others. Myths -- especially the 'Greek myths' -- were top of the list and legends came second, while fairy tales were the poor cousins at the bottom. Yet there appeared to be a considerable overlap. Andrew Lang included the story of Perseus and Andromeda in The Blue Fairy Book, under the title 'The Terrible Head.' And surely he was right. It is a fairy story, about a prince who rescues a princess from a monster....

"The field of fairy stories, legends, folk tales and myths is like a great, wild meadow. The flowers and grasses seed everywhere; boundaries are impossible to maintain. Wheat grows into the hedge from the cultivated fields nearby, and poppies spring up in the middle of the oats. A story can be both things at once, a 'Greek myth' and a fairytale too: but if we're going to talk about them, broad distinctions can still be made and may still be useful.

"Here is what I think: a myth seeks to make emotional sense of the world and our place in it. Thus, the story of Persephone's abduction by Hades is a religious and poetic exploration of winter and summer, death and rebirth. A legend recounts the deeds of heroes, such as Achilles, Arthur, or C�� Chulainn. A folk tale is a humbler, more local affair. Its protagonists may be well-known neighborhood characters or they may be anonymous, but specific places become important. Folk narratives occur in real, named landscapes. Green fairy children are found near the village of Woolpit in Suffolk. A Cheshire farmer going to market to sell a white mare meets a wizard, not just anywhere, but on Alderley Ledge between Mobberley and Macclesfield. In Dorset, an ex-soldier called John Lawrence sees a phantom army marching 'from the direction of Flowers Barrow, over Grange Hill, and making for Wareham.' Local hills, lakes, stones and even churches are explained as the work of giants, trolls or the Devil.

"Here is what I think: a myth seeks to make emotional sense of the world and our place in it. Thus, the story of Persephone's abduction by Hades is a religious and poetic exploration of winter and summer, death and rebirth. A legend recounts the deeds of heroes, such as Achilles, Arthur, or C�� Chulainn. A folk tale is a humbler, more local affair. Its protagonists may be well-known neighborhood characters or they may be anonymous, but specific places become important. Folk narratives occur in real, named landscapes. Green fairy children are found near the village of Woolpit in Suffolk. A Cheshire farmer going to market to sell a white mare meets a wizard, not just anywhere, but on Alderley Ledge between Mobberley and Macclesfield. In Dorset, an ex-soldier called John Lawrence sees a phantom army marching 'from the direction of Flowers Barrow, over Grange Hill, and making for Wareham.' Local hills, lakes, stones and even churches are explained as the work of giants, trolls or the Devil.

"Fairy tales can be divided into literary fairy tales, the more-or-less original work of authors such as Hans Christian Andersen, George MacDonald and Oscar Wilde (which will not concern me very much in this book), and anonymous traditional tales originally handed down the generations by word of mouth but nowadays usually mediated to us via print. Unlike folk tales, traditional fairy tales are usually set 'far away and long ago' and lack temporal and spatial reference points. They begin like this: 'In olden times, when wishing still helped one, there lived a king...' or else, 'A long time ago there was a king who was famed for his wisdom throughout the land...' A hero goes traveling, and 'after he had traveled some days, he came one night to a Giant's house...' We are everywhere or nowhere, never somewhere. A fairy tale is universal, not local."

Katherine concludes the book's introduction with the reminder that fairy tales, found all around the world, are amazingly diverse and amazingly hardy. "They've been told and retold, loved and laughed at, by generation after generation because they are of the people, by the people, for the people. The world of fairy tales is one in which the pain and deprivation, bad luck and hard work of ordinary folk can be alleviated by a chance meeting, by luck, by courtesy, courage and quick wits -- and by the occasional miracle. The world of fairy tales is not so very different from ours. It is ours."

It is indeed.

Seven Miles of Steel Thistle is available from The Greystones Press, a terrific new publishing venture by Mary Hoffman and Stephen Barber. (Check out their other books too.) You can read Katherine's musings on folklore on her blog, also called Seven Miles of Steel Thistles; and learn more about her other books, stories, and essays here.

There are seven miles of hill on fire for you to cross, and there are seven miles of steel thistles, and seven miles of sea, says the narrator of an old Irish fairy tale.

With this delightful collection of essays as a guide, the journey is worth every step.

Words: The passages by Katherine Langrish in the post above and in the picture captions are from Seven Miles of Steel Thistles (The Greystones Press, 2016); all rights reserved by the author. Pictures: The illustrations are by H.J. Ford, from the Fairy Books edited by Andrew Lang.

Words: The passages by Katherine Langrish in the post above and in the picture captions are from Seven Miles of Steel Thistles (The Greystones Press, 2016); all rights reserved by the author. Pictures: The illustrations are by H.J. Ford, from the Fairy Books edited by Andrew Lang.

May 30, 2016

About the exhibition:

Dartmoor, a landscape steeped in...

About the exhibition:

Dartmoor, a landscape steeped in mythic and legend, is home to a large number of artists inspired by mythic themes. The works in this show explore myth, folklore, and faery tales in diverse ways, ranging from earthy to ethereal, sensual to spiritual, and frightening to whimsical...shaped into paintings, sculptures, assemblages, magical clocks, handbound books, and more.

Participating artists:

Alan Lee, Marja Lee, Virginia Lee, Brian Froud, Wendy Froud, David Wyatt, Rima Staines, Danielle Barlow, Angharad Barlow, and me (all from Chagford); Hazel Brown (from Torquay); Pauline Lee (from Ashburton), Neil Wilkinson-Cave (from Moretonhampstead); and Paul Kidby (from Hampshire, but with strong Dartmoor connections).

In addition to the main gallery show, Green Hill will display mythic art and crafts throughout the art centre (by Alexandra Dawe, Meg Connolly, Leonie Grey, Sally Hinchcliffe, and others); and books and prints will be on sale in the Green Hill shop. They've also organized a programme of related events to run throughout the summer: workshops, talks, film showings, etc., for both adults and children. Please contact Green Hill Arts, or visit the Calendar section of their website, for more information.

I'll be at at the Meet the Artists evening on August 6th; at a Coffee Morning with three other women artists (Wendy Froud, Marja Lee, and Hazel Brown) on July 11th; and I'm giving talk on August 20th on The Power of Story: Healing & Transformation in Folk & Fairy Tales. Do come if you can.

For photographs from the first Widdershins exhibition in 2013, go here (via Virginia Lee) or here (via Rima Staines).

May 22, 2016

Myth & Moor update

Re-posting this in case anyone missed it:

I will be delivering the 4th Annual Tolkien Lecture at Pembroke College, Oxford University this Thursday at 6:30 pm. The Pembroke Fantasy lecture series "explores the history and current state of fantasy literature, in honour of JRR Tolkien, who wrote The Hobbit and much of The Lord of the Rings during his twenty years at the college." The lecture I'll be giving is Tolkien's Long Shadow: Reflections on Fantasy Literature in the Post-Tolkien Era. Admission is free, but you need to register for a ticket and space is limited. Go here for further details.

I am taking a short break from Myth & Moor this coming week to deal with other pressing matters, and to prepare for Oxford. May 30th is a holiday here in Britain, so the Hound and I will be back on Tuesday, May 31st.

May 30th is also the date of the annual Two Hills Race here in Chagford, a gruelling route up and down two steep hills, with brambles and a bog in between. Our nine-year-old friend Fynn has decided to run this year to raise money to support wounded veterans. If you can spare a few pennies to pledge to this young man's heart-felt cause, it would encourage him greatly (and make those of us who care for him very happy too). The site takes Paypal and credit cards in any currancy, and even very small amounts are welcome. More info here.

Have a good and creative week.

May 21, 2016

Light and shadow, part two

"When I am constantly running there is no time for being. When there is no time for being there is no time for listening." - Madeleine L'Engle (Walking on Water)

I'd been looking forward to a solitary, calm, work-focused week while my husband was up in London...but it turned into one of crisis-management instead, the quiet of my creative voice drowned out by a louder chorus of life's demands. The stress level rose in my studio, and by Friday Tilly had clearly had enough. Normally if I'm too busy or tired for our morning walk she accepts it with good grace, but this time she would simply not give up. She stared and stared. She tapped my knee with her paw, eyes wide, her intention clear. She walked to the door and back, over and over, and then tapped me on the knee once more. And so, at last, I gave in, closed down the computer and laced up my boots.

I followed her out the garden gate, through the woods and onto Nattadon Hill, carpeted now with bluebells and swaths of stitchwort like little white stars.

Work fell away. Words fell away. Heart-ache and worry slowly fell away too. We climbed, and climbed, the air tasting of flowers, and I grew a little lighter with every step. Re-discovering, as Madeleine L'Engle would say, time for being. And for listening.

An hour later we came back down, following the path through wildflowers and bracken back to the studio. The problems pressing on me hadn't solved themselves, the work on my desk hadn't disappeared, and I wasn't magically flooded with new insight and energy for tackling both those things...but it was better. A subtle, almost imperceptible change, but it was enough.

As long there are moments of beauty on the hard, dark days, I know that I can keep on going.

And that you can too.

The Madeleine L'Engle quote is from Walking on Water: Reflections on Faith & Art (Wheaton Literary Series, 2001). The poem in the picture captions is from Where Many Rivers Meet by David Whyte (Many Rivers Press, 2004). All rights reserved by the authors.

The Madeleine L'Engle quote is from Walking on Water: Reflections on Faith & Art (Wheaton Literary Series, 2001). The poem in the picture captions is from Where Many Rivers Meet by David Whyte (Many Rivers Press, 2004). All rights reserved by the authors.

May 19, 2016

Light and shadow

I'm struggling with life today and I have no words. I offer you this peaceful picture of our girl instead, which is a poem and a prayer in itself.

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 708 followers