Terri Windling's Blog, page 111

July 20, 2016

Recommended Reading:

In a lovely new piece on becoming a novelist, Ramona Ausubel writes:

"We are not ever just writers -- we are also sons and daughters of good parents and disappointing parents and we are partners who need to pick up a quart of milk on the way home and parents who crawl into bed with the little ones late at night to admire them when they are still, even though we know we don���t have any tiredness to spare. We are students and teachers. We are readers, taking in the universes created by other minds. Our stories and poems and essays are written in and amongst and because of these moments."

So true. As it this:

"People will tell you that you need a thick skin to be a writer, what with all that disappointment and rejection, but I think part of what makes a good writer is the ability to be porous, to be able to feel all the intricate and complicated notes, the particular music of each moment. No writer should turn the volume down on her own emotional register. That���s her instrument. We have to feel everything."

Go here for the full article. It's beautifully written, funny, and wise.

The language of moving

The new issue of EarthLines (a magazine I highly recommend if you're not already a subscriber) is packed with treasures, including an insightful article on "The Language of Moving" by Alex Klaushofer. This captured my attention not only because I've moved many times myself over the course of my life (sometimes willingly, sometimes not, each move disruptive in its own way), but also because our daughter has recently moved back to Devon after several years of study and work in London -- and even such a relatively simple move, to a place already well-known and loved, has thrown up unexpected challenges, reminding me that there is a mythic quality to the act of pulling up roots and transplanting them. It's never truly simple, not on the practical level and especially not in the deeper, barely-conscious realm of dream, soul, and creative inspiration.

In "The Language of Moving," Klaushofer's relocation from suburban London to the Cotswolds was one she'd chosen and long desired, yet the difficulty of the transition from one sort of life to another took her by surprise. Moving, she says, "brought with it an uprooting, a displacing not acknowledged in the dominant discourse, especially not by those of my generation. Social talk about moving tends to focus relentlessly on the positive, with comments on the excitement that a new house and surroundings will bring. Perhaps not surpringly, since they come from a time when life was less atomized, it is older people who seem to understand the rupture involved in changing place. My eighty-something godmother enquires solicitiously again and again as to how I am feeling: am I settling? Do I feel strange?"

A little later in the article she comes back to the general absence of societal recognition of just how difficult moving can be:

"I'm coming to think that this absence is part of a broader lack in our language about our relation to place. Standard English has just one word for feelings of longing for a particular place: 'homesick.' The word implies a polarity: you are at home or away, and suggests the simple solution of going home; it carries no sense of the process of adapting to a new place or of mixed or complex feelings. Other languages of the British Isles do much better at capturing the range of feelings and experiences that make up the human attachment to place. Welsh has 'hiraeth,' a word that connotes a yearning for place that is lost or may not exist, a feeling of longing to be 'at home' in the sense of achieving a sense of belonging, of finding your paradise. Its cognate 'cynefin' denotes 'habitat' or 'customary abode'; the place which formed you, and with which you are most familiar. In a definition which encompasses cultural, social and geographical influences, Nicholas Sinclair describes it as 'the place of your birth and upbringing, the environment in which you live and to which you are naturally acclimatized.' The Scottish Gaelic 'd��thchas' conveys the collective nature of a heritage that connects people to a particular place, historically also the tribal system of land rights accorded to the members of a clan. The fact that the Scottish Gaelic equivalent of homesickness, nostalgia or longing for home, cianalas, has given rise to a genre of Gaelic poetry written by emigrees called b��rdachd cianalais is perhaps testament to how a profound sense of rootedness finds linguistic expression."

We think of moving as a straightforward proposition: the bags are packed, the house is emptied, the old door is shut and locked one final time, and then we're to the next adventure. Hey ho, here we go! We arrive in our new location: the suitcase is unpacked, the books placed in their new setting, morning coffee is poured into familiar cups but the kitchen window has a brand new view...yet after the relief that the move is finally "over" often comes a sense of...flatness. Of nameless anxiety. Of self-doubt and three-in-the-morning fears  that the move was a terrible mistake. This is all perfectly normal, we assure our daughter...and I remember friends making similar assurances to me after various uprootings. We don't move from one phase of life to another as easily and clearly as stepping through a door; there is a time of transition, a liminal space between there and here to be moved through as we re-form into the person who is going to live in this new place. The length of time is different for each move, but the one thing I've learned after all these years is that the mythic journey through the threshold of change is shorter, gentler, and less overwhelming if we remain aware of the transitional process, and accept it. Better still, respect it.

that the move was a terrible mistake. This is all perfectly normal, we assure our daughter...and I remember friends making similar assurances to me after various uprootings. We don't move from one phase of life to another as easily and clearly as stepping through a door; there is a time of transition, a liminal space between there and here to be moved through as we re-form into the person who is going to live in this new place. The length of time is different for each move, but the one thing I've learned after all these years is that the mythic journey through the threshold of change is shorter, gentler, and less overwhelming if we remain aware of the transitional process, and accept it. Better still, respect it.

Klaushofer notes that we have more words in English for the various aspects of "attachment to place" when it comes to animals, not human beings. Such as this one from sheep husbandry:

" 'Hefting' describes the process by which a ewe learns, traditionally through its mother, to stay in one particular area; once 'hefted,' the hill farmer has no need to confine the flock with fences because it will naturally incline to one pasture.

"The existence of a word for the ovine attachment to place is a reminder that, in its sparsity, our language of place forgets that we too are animals, with a pre-cognitive, non-economic attachment to the places we inhabit. Like the fox I used to see patrolling the streets of south London at the same time and in the same order every day, humans also have their runs and routines, whether built around exercise, dog walking or errands, that reflect their attachement to their habitat. Yet in a post-agricultural society which fosters a belief in our independence from the earth we almost never think in these terms."

Settled in the Cotswolds, but not yet truly settled, Klausofer writes, "I'm aware that I haven't quite hefted, that I'm in the midst of a transition, the in-between time that goes unacknowledged in the dominant discourse about moving."

Hefted. That's a wonderful word, and one I will remember and use.

For further insights into the art of moving place, I recommend reading Klaushofer's article in full.

The art today is by Helen Allingham (1848-1926), a Victorian painter, illustrator, and the first woman artist granted full membership in the Royal Watercolour Society. Born in Derbyshire, raised in Birmingham, Allingham was encouraged in art from an early age -- for both her grandmother and her aunt were professional artists, which was still unusual at that time. She studied art at the Birmingham School of Design, at the National Art Training School in London (now the Royal School of Art), and in night classes at the Slade -- where she met fellow illustrator Kate Greenaway, a life-long friend. Over the course of her professional career she illustrated books for both children and adults as well as popular newspapers and magazines. In 1874 she married the Scottish poet William Allingham (author of The Fairies: "Up the airy mountain/Down the rushy glen,/We daren't go a-hunting/For fear of little men..."). The couple moved to Sussex to raise their family, where Allingham fell in love with the rural landscape and began the work for which she is best known: watercolors of women, children, animals, and the country cottages of Sussex, Surrey, and Kent.

Although her work has largely fallen out of favor, castigated for its Victorian sentimentality, her gentle renditions of domestic life are known to have influenced many younger artists, including the young Vincent van Gogh (who found them in English magazines). In preparing this post, and thinking of artists whose work demonstrates a deep love of "place" and "home," Helen Allingham sprung immediately to mind.

The passage above by Alex Klaushofer is from "The Language of Moving" (EarthLines: The Culture of Nature, edited by David Knowles & Sharon Blackie, July 2016); all rights reserved by the author. I highly recommend the article, as well as the rest of this excellent issue of EarthLines. A related post: Kith & Kin. A related article: The Folklore of Hearth & Home.

The passage above by Alex Klaushofer is from "The Language of Moving" (EarthLines: The Culture of Nature, edited by David Knowles & Sharon Blackie, July 2016); all rights reserved by the author. I highly recommend the article, as well as the rest of this excellent issue of EarthLines. A related post: Kith & Kin. A related article: The Folklore of Hearth & Home.

July 19, 2016

The magic that is patiently waiting

After weeks and weeks of feeling pummelled by the daily news, I continue to root myself in the land, walking with quiet attentiveness, senses alert and heart open, despite every impulse to close myself down. I will not add to the voices of anger that seem to be everywhere right now, nor will I fall into the silence of sorrow. Quiet attentiveness is not silence; it's a form of deep listening, an important part of the alchemical process of art-making. Of healing. Of changing, and of making change happen. Without connection to the magic of the natural world, I cannot do my own work in the world -- and so I walk, and listen. And then I go back to the studio and write.

In an interview in Paris Review, the late American novelist and essayist Jim Harrison said:

In an interview in Paris Review, the late American novelist and essayist Jim Harrison said:

"Antaeus magazine wanted me to write a piece for their issue about nature. I told them I couldn���t write about nature but that I���d write them a little piece about getting lost and all the profoundly good aspects of being lost -- the immense fresh feeling of really being lost. I said there that my definition of magic in the human personality, in fiction and in poetry, is the ultimate level of attentiveness.

"Nearly everyone goes through life with the same potential perceptions and baggage, whether it���s marriage, children, education, or unhappy childhoods, whatever; and when I say attentiveness I don���t mean just to reality, but to what���s exponentially possible in reality. I don���t think, for instance, that M��rquez is pushing it in One Hundred Years of Solitude -- that was simply his sense of reality. The critics call this magic realism, but they don���t understand the Latin world at all. Just take a trip to Brazil. Go into the jungle and take a look around.

"This old Chippewa I know -- he���s about seventy-five years old -- said to me, 'Did you know that there are people who don���t know that every tree is different from every other tree?' This amazed him. Or don���t know that a nation has a soul as well as a history, or that the ground has ghosts that stay in one area. All this is true, but why are people incapable of ascribing to the natural world the kind of mystery that they think they are somehow deserving of but have never reached? This attentiveness is your main tool in life, and in fiction..."

"A living, speaking, real landscape is always full of magic," writes Sylvia Linsteadt. "Magic is the language of elk as they speak to each other through the fog. Magic is the way granite forms over millennia, the way murres lay green eggs. Magic is the sounds of tall grasses in the wind. Magic is the way fog is formed. Magic is the stories people leave behind in the places they inhabit, the spirits, ghosts and gods they talk to. Magic is the towhee poking about in the dirt for worms and seeds, singing her own peculiar tune."

"The world is full of magic things," said William Butler Yeats, "patiently waiting for our senses to grow sharper.''

The quote by Jim Harrison (1937-2016) is from "The Art of Fiction No. 104" (Paris Review, 1986). The Sylvia Linsteadt quote is from "Of Otters and Words With Roots" (The Gleewoman's Notes, July 2012). The poem in the picture captions is from New & Selected Poems by Mary Oliver (Beacon Press, 1993). All rights reserved by the authors. The drawing above is by Eleanor Vere Boyle (1825-1916).

The quote by Jim Harrison (1937-2016) is from "The Art of Fiction No. 104" (Paris Review, 1986). The Sylvia Linsteadt quote is from "Of Otters and Words With Roots" (The Gleewoman's Notes, July 2012). The poem in the picture captions is from New & Selected Poems by Mary Oliver (Beacon Press, 1993). All rights reserved by the authors. The drawing above is by Eleanor Vere Boyle (1825-1916).

July 18, 2016

Tunes for a Monday Morning

This week's tunes are all about love, because we can certainly use more of that these days.

Above, a trio of new songs by Sam Beam & Jesca Hoop, performed for the Tiny Desk Concert series at the NPR offices last month. (NPR is America's publicly-funded radio network.) The songs are "Sailor to Siren," "Know the Wild that Wants You," and "Every Songbird Says," from the duo's beautiful album, Love Letter for Fire. Sam Beam, based in North Carolina, is best know for his three albums under the name Iron & Wine. Jesca Hoop was born in California, now lives in Manchester, England, and has released five solo albums to date. (The animated video that Sam refers to in his intro to the last song, by the way, is here.)

Below, Beam & Hoop perform "One Way to Pray" (my favorite song on the new album) at New York's WKCR radio station.

And last: "Left Handed Kisses" by Andrew Bird, performed with Fiona Apple. Bird, a singer/songwriter from Illinois, cites British folk music as an early influence. He's released nine solo studio albums, plus several live recordings and albums with the bands Squirrel Nut Zippers and Bowl of Fire. This song is from his most recent release, Are You Serious (2016).

���Love all, trust a few, do wrong to none." - William Shakespeare (All's Well That Ends Well)

The painting above is by Florence Susan Harrison (1878-1955). The drawing is by A.W. Bayles (1832-1909). This post is dedicated to Shany, for introducing me to Andrew Bird's music. And to Howard. He knows why.

July 16, 2016

On moving forward through difficult times, part five: Why Culture Matters

I'm popping into the studio on a Saturday to recommend a superb article by Frank Cottrell Boyce on "the generosity of art," a discussion ranging from the Opening Ceremony of the 2012 Olympics to the value of gift exchange, reading Heidi, and the poetry of Philip Larkin.

If you read nothing else this week, please do read this. It's an important piece. And so inspiring.

July 15, 2016

On moving forward through difficult times, part four: Why Stories Matter

"Stories teach us how to be human," writes Scott Russell Sanders (in one of my all-time favorite essays, The Power of Stories). "As I understand it, becoming fully human means learning to savor the world, to share in community, to see through the eyes of other people, to take reponsibility for our actions, to educate our desires, to dwell knowingly in time and place, to cope with suffering and death.

"We are creatures of instinct, but not solely of instinct. More than any other animal we must learn to behave. In this perennial effort, as Ursula K. Le Guin says, 'Story is our nearest and dearest way of understanding our lives and finding our way forward.' Skill is knowing how to do something; wisdom is knowing when and why to do it. While stories may display skills aplenty, in technique or character or plot, what the best of them offer is wisdom. They hold a living reservoir of human possibilities, telling us what has worked before, what has failed, what meaning and purpose and joy might be found.

"At the heart of many tales is a test, a puzzle, a riddle, a problem to solve; and that, surely, is the condition of our lives, both in detail -- as we decide how to act in the present moment -- and in general, as we seek to understand what it all means. Like so many characters, we are lost in a dark wood, a labyrinth, a swamp, and we need a trail of stories to show us the way back to our true home."

So please, creative people, keep telling those stories, in whatever medium you work in. Keep listening to the stories of others. Keep building those trails leading out of the dark woods.

And for those passing through the dark right now, stay safe. Stay open-hearted. Stay strong.

Scott Russell Sander's "The Power of Stories" was first published in The Georgie Review (Springm 1997), and can also be found in his essay collection The Force of Spirit (Beacon Press, 2000). The poem in the picture captions comes from The Antigonish Review (#126, 2001). All rights reserved by the authors.

Scott Russell Sander's "The Power of Stories" was first published in The Georgie Review (Springm 1997), and can also be found in his essay collection The Force of Spirit (Beacon Press, 2000). The poem in the picture captions comes from The Antigonish Review (#126, 2001). All rights reserved by the authors.

July 13, 2016

On moving forward through difficult times, part three: Telling Our Stories

This post is from the archives, but seems pertinent this week:

���I believe in all human societies there is a desire to love and be loved, to experience the full fierceness of human emotion, and to make a measure of the sacred part of one's life. Wherever I've traveled -- Kenya, Chile, Australia, Japan -- I've found the most dependable way to preserve these possibilities is to be reminded of them in stories. Stories do not give instruction, they do not explain how to love a companion or how to find God. They offer, instead, patterns of sound and association, of event and image. Suspended as listeners and readers in these patterns, we might reimagine our lives." - Barry Lopez (About This Life)

"I come from a long line of tellers: mesemondok, old Hungarian women who tell while sitting on wooden chairs with their plastic pocketbooks on their laps, their knees apart, their skirts touching the ground...and cuentistas, old Latina women who stand, robust of breast, hips wide, and cry out the story ranchera style. Both clans storytell in the plain voice of women who have lived blood and babies, bread and bones. For them, story is a medicine which strengthens and arights the individual and the community." - Clarissa Pinkola Est��s (Women Who Run With the Wolves)

"Make up a story.

"Narrative is radical, creating us at the very moment it is being created. We will not blame you if your reach exceeds your grasp; if love so ignites your words they go down in flames and nothing is left but their scald. Or if, with the reticence of a surgeon's hands, your words suture only the places where blood might flow. We know you can never do it properly -- once and for all. Passion is never enough; neither is skill. But try. For our sake and yours forget your name in the street; tell us what the world has been to you in the dark places and in the light. Don't tell us what to believe, what to fear. Show us belief's wide skirt and the stitch that unravels fear's caul."

- Toni Morrison (Nobel Prize acceptance speech, 1993)

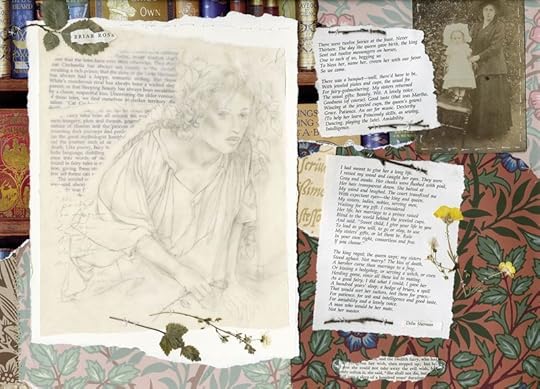

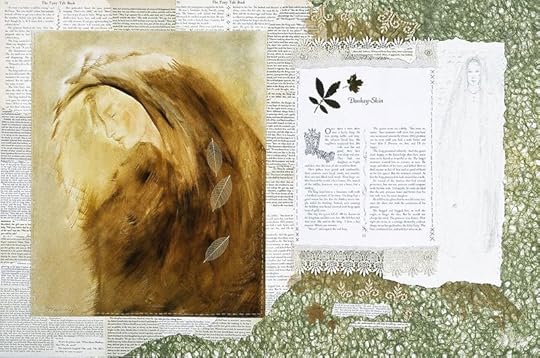

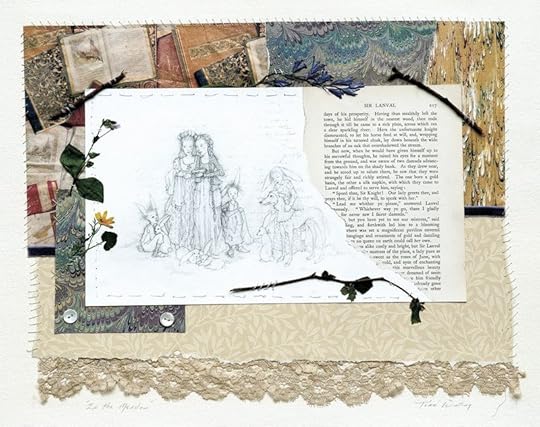

The poems tucked into the picture captions are "Caraboose" �� 1999 by Delia Sherman (read the full poem here), "Donkeyskin" �� by Midori Snyder �� 2001, and "Once Upon a Time,' She Said" by Jane Yolen, all rights reserved. My collages above are: "Briar Rose," "Donkeyskin," and "In the Meadow." Recommended reading: "Susan Sontag on Storytelling" by Maria Popova. (Brain Pickings)

The poems tucked into the picture captions are "Caraboose" �� 1999 by Delia Sherman (read the full poem here), "Donkeyskin" �� by Midori Snyder �� 2001, and "Once Upon a Time,' She Said" by Jane Yolen, all rights reserved. My collages above are: "Briar Rose," "Donkeyskin," and "In the Meadow." Recommended reading: "Susan Sontag on Storytelling" by Maria Popova. (Brain Pickings)

On moving forward through difficult times, part two: Walking Among Miracles

From Still Writing by Dani Shapiro:

"Too often, our capacity for awe is buried beneath layers of perfectly reasonable excuses. We feel we must protect ourselves -- from hurt, disappointment, insult, loss, grief -- like warriors girding for battle. A Sabbath prayer I have carried with me for more than half my life begins like this: 'Days pass and the years vanish and we walk sightless among miracles.'

"We cannot afford to walk sightless among miracles. Nor can we protect ourselves from suffering. [As writers] we do work that thrusts us into the pulsing heart of the world, whether or not we're in the mood, whether or not it's difficult or paintful or we'd prefer to avert our eyes.

"When I think of the wisest people I know, they share one defining trait: curiosity. They turn away from the minutiae of their lives -- and focus on the world around them. They are motivated by a desire to explore the unfamiliar. They enjoy surprise."

Words: The passage by Dani Shapiro is from Still Writing: The Perils & Pleasures of a Creative Life (Grove Press, 2014); the poem in the picture captions is from Sands of the Well by Denise Levertov (New Directions, 1996); all rights reserved by the authors. "On moving forward through difficult times," part one, is here.

Words: The passage by Dani Shapiro is from Still Writing: The Perils & Pleasures of a Creative Life (Grove Press, 2014); the poem in the picture captions is from Sands of the Well by Denise Levertov (New Directions, 1996); all rights reserved by the authors. "On moving forward through difficult times," part one, is here.

Pictures: The back garden here at Bumblehill, Howard in the garden, and Tilly sniffing the air in a moment of rapture (on the porch of Howard's studio at the back of the garden).

On moving forward through difficult times, part two:

From Still Writing by Dani Shapiro:

"Too often, our capacity for awe is buried beneath layers of perfectly reasonable excuses. We feel we must protect ourselves -- from hurt, disappointment, insult, loss, grief -- like warriors girding for battle. A Sabbath prayer I have carried with me for more than half my life begins like this: 'Days pass and the years vanish and we walk sightless among miracles.'

"We cannot afford to walk sightless among miracles. Nor can we protect ourselves from suffering. [As writers] we do work that thrusts us into the pulsing heart of the world, whether or not we're in the mood, whether or not it's difficult or paintful or we'd prefer to avert our eyes.

"When I think of the wisest people I know, they share one defining trait: curiosity. They turn away from the minutiae of their lives -- and focus on the world around them. They are motivated by a desire to explore the unfamiliar. They enjoy surprise."

Words: The passage by Dani Shapiro is from Still Writing: The Perils & Pleasures of a Creative Life (Grove Press, 2014); the poem in the picture captions is from Sands of the Well by Denise Levertov (New Directions, 1996); all rights reserved by the authors. "On moving forward through difficult times," part one, is here.

Words: The passage by Dani Shapiro is from Still Writing: The Perils & Pleasures of a Creative Life (Grove Press, 2014); the poem in the picture captions is from Sands of the Well by Denise Levertov (New Directions, 1996); all rights reserved by the authors. "On moving forward through difficult times," part one, is here.

Pictures: The back garden here at Bumblehill, Howard in the garden, and Tilly sniffing the air in a moment of rapture (on the porch of Howard's studio at the back of the garden).

July 12, 2016

That's the Way to Do It: Dame Judy & Mr. Punch

At the back of our garden, up against the woods, is the two-room cabin where Howard has his office and a small theatre studio. My own studio is not far away, so I often hear a variety of sounds drifting over the hedge between us: it might be accordion or mandolin practice one moment, lines declaimed from Shakespeare the next...or the growls of gnomes...or the Hedgespoken team planning works of wild hedgerow theatre for their travelling stage. Lately, however, I'd been hearing the odd "swazzle" voice of the puppet Mr. Punch -- a sound which sent Tilly into fits of barking, until she finally figured out it was Howard at work.

His studio has been used for puppetry performances before, but right now it's a vibrant, bustling workshop as he puts a new Punch & Judy show together. Puppet heads are scattered across tables and shelves, puppet clothes hang from our washing line, and even Tilly is getting used to Mr. Punch and his colorful companions....

I confess I was never a big fan of Punch & Judy or of slap-stick comedy in general before I met my husband -- whose life has been devoted to the European form of masked theatre known as Commedia dell'Arte, which is very slapstick, and very funny, and which won me over its mix of ridiculous pratfalls and sly, wry intelligence. Howard helped me to see the mythic roots of such comedy in Trickster tales and Dionysian revels, in the sacred anarchy of traditional carnaval and rural folk pageantry. Now I'm fascinated by lines of connection between the various forms of mask/puppet theatre and folk use of these arts in ritual form: in the Jack-in-Greens and Obby Osses of England, in the masked dances of the America's indigenous peoples, and in other folk rites and sacred traditions all across Europe and around the globe.

The ritualized slapstick violence of Punch & Judy is problematic today, however, for we tend to "read" the story in a literal fashion, interpreting the action as domestic abuse, when it is best understood metaphorically, as the unleashing of pure anarchy. Mr. Punch is a Trickster figure: a manifestation of Trickster's wicked delight in violating all social norms and constraints -- brazenly knocking down every authority figure (which is precisely why children love him). The challenge for performers today is to craft a story that conveys this same archetypal spirit of contrariness, freedom, and anarchy, without tacitly condoning violence, domestic or otherwise, in the real world.

(See Emma Windsor's recent post on the subject on the Puppet Place News blog.)

If you'd like to know more about the history of Punch & Judy, I recommend "That's the Way to Do It!" on the Victoria & Albert Museum website, curated to honor the show's 350th anniversary in 2012 -- a date based on the first known puppet play in England to contain a version of Mr. Punch, recorded by Samuel Pepys in 1662.

"He noted seeing it in Covent Garden," writes the V&A's curator, "performed by the Italian puppet showman Pietro Gimonde from Bologna, otherwise known as Signor Bologna: 'Thence to see an Italian puppet play that is within the rayles there, which is very pretty, the best that ever I saw, and a great resort of gallants.'

"He noted seeing it in Covent Garden," writes the V&A's curator, "performed by the Italian puppet showman Pietro Gimonde from Bologna, otherwise known as Signor Bologna: 'Thence to see an Italian puppet play that is within the rayles there, which is very pretty, the best that ever I saw, and a great resort of gallants.'

"Bologna was one of many entertainers who came to England from the continent following the restoration of the monarchy in 1660. Unlike today���s Punch & Judy, performed with glove puppets in canvas booths with the audience outside, Bologna used marionettes -- puppets with rods to their heads and strings or wires to their limbs ��� and performed within a transportable wooden shed, and as such would have been quite a novelty. Pepys was so delighted by the show that he brought his wife to see it two weeks later, and in October 1662 Bologna was honoured with a royal command performance by Charles II at Whitehall, where a stage measuring 20ft by 18ft was set up for him in the Queen���s Guard Chamber. The king rewarded ���Signor Bologna, alias Pollicinella��� with a gold chain and medal, a gift worth ��25 then, or about ��3,000 today. Other Italian puppeteers appeared in London, and on 10 November 1662 Pepys took his wife to see another show in a booth at Charing Cross performing: ���the Italian motion, much after the nature of what I showed her at Covent Garden.'

"Pepys usually referred to the shows as Polichinello, a name relating to Punch���s roots in the Italian Commedia dell���Arte, where masked actors improvised comic knockabout plays around a number of stock characters, and Polichinello was the subversive, thuggish character whose Italian name Pulcinella or Pulliciniello may have developed from the word pulcino, or chicken, referring to the character���s beak-like mask and squeaky voice.

"Punch���s characteristic voice comes from the use of a reed retained at the back of the Punchman���s or ���professor���s��� mouth, calling for expert alternation of reed use when Punch is talking to other characters. In Britain the reed is called a swazzle, and in France a sifflet-pratique. Its  most common Italian name was pivetta, but also sometimes strega, or witch, and franceschina, after Franchescina, one of Punch���s wives in the Commedia dell���Arte who had a voice like a witch. Swazzles are made of thin metal today, but bone or ivory were formerly used, each equally tricky to master and easy to swallow.

most common Italian name was pivetta, but also sometimes strega, or witch, and franceschina, after Franchescina, one of Punch���s wives in the Commedia dell���Arte who had a voice like a witch. Swazzles are made of thin metal today, but bone or ivory were formerly used, each equally tricky to master and easy to swallow.

"Mr. Punch made himself thoroughly at home in Britain during the 18th century. His wife was the shrewish Dame Joan who made his life a misery, and his hunched back and pot belly became more pronounced. The marionette Punch was the celebrity disrupting the action in puppet plays all around the country, in established puppet theatres and in fairground booths where puppets were a popular feature of all the great fairs and small country wakes throughout the century."

Marionette shows were expensive to operate, however, "and by the end of the 18th century glove puppet versions of the Punch show, performed in small portable booths became a familiar sight on city streets and country lanes instead."

"With Punch���s move from marionette stage to portable booth came new clothes and new companions. By 1825 we hear in Bernard Blackmantle���s The English Spy of his wife being called Judy instead of Joan: ���old Punch with his Judy in amorous play,��� and of Punch���s having a Toby the dog, usually played by a real dog....

"Punch & Judy shows were not just for children in the early 19th century. Aspects of the comedy such as the marital strife between Punch and Judy, and in Piccini���s show the relationship between Punch and his girlfriend Pretty Polly, obviously struck a chord with many adult members of the audience. Punch was a well known celebrity with the satirical magazine named after him in London in 1841, children���s picture books published based on his shows, and images of him proliferating on all manner of household artefacts, from doorstops to baby���s rattles.

"As today, some censured the shows for Punch���s violent behaviour, but Punch & Judy found an ally in Charles Dickens, whose novels include several references to the shows. Dickens defended them as enjoyable fantasy that would not incite violence:

"'In my opinion the Street Punch is one of those extravagant reliefs from the realities of life which would lose its hold upon the people if it were made moral and instructive.' "

About the photographs in this post, Howard says:

"In the early nineties, whilst working at Norwich Puppet Theatre, I started to carve a Punch & Judy show. Then later on, towards the end of that decade, whilst working at the Little Angel Theatre in London, I carved more of the puppets. I never finished it. Last month, I went to an excellent Punch & Judy workshop at the Little Angel, run by Prof. Glynn Edwards (aided and abetted by Clive Chandler). When I got home I rooted out my unfinished Punch & Judy set. I am now finishing it off, and working on a show."

Keep an eye on his theatre Facebook page if you'd like to see how the project develops.

For more information on Punch & Judy, visit the V&A's Punch & Judy pages, Punch & Judy Online, and the Punch & Judy Fellowship. For puppetry in general, see The Curious School of Pupptry (where Howard teaches), the Puppet Place News blog, Puppeteers UK, and The Centre for Research on Objects & Puppets in Performance. For information on the mythic roots of comedy, see Midori Snyder's "A Chorus of Clowns and Masked Comic Theater."

The art and photographs above are identified in the picture captions. (Run your cursor over the images to see them.)

The art and photographs above are identified in the picture captions. (Run your cursor over the images to see them.)

Terri Windling's Blog

- Terri Windling's profile

- 708 followers