Lee Martin's Blog, page 68

October 4, 2012

Watching and Listening During My Recuperation

Comments from the Convalescent:

When I began this convalescence, I envisioned catching up on books I’ve been wanting to read in between naps. What I’ve learned, though, is that restoration is hard work. First come the sleepless nights when the anxiety of what might happen with my next breath overwhelms me. Then comes the depression in the midst of a flurry of calls to doctors and the insurance company A whole lotta hub-hub going on. Not to mention the three daily walks, fussing with cranky heart monitor electrodes, trying to get used to the weight of that contraption sliding around with me when I try to sleep. Mama, it’s hard to find a rhythm.

As the days go on and I approach the two-week anniversary of my stroke, I’m slowly feeling my way back to a routine that will work for me. I’m having to relearn how to spend my days, with my eye on returning to teaching next week. I’ve been watching and listening. Along the way, what feels right to me is that role of the observer that’s so familiar to the way I’ve always lived my life.

It’s Just Life Going on the Way It Does:

A man near me at my neurologist’s reception counter says, “I need to change my emergency contact. He’s going to jail.”

A young man smokes a cigarette while squatting on his heels outside the garage of the house where the night before I heard a woman screaming.

A boy’s bicycle has been along the curb on the main street into my subdivision overnight and all day.

My neurologist says to me, “I’m going to give you three words I want you to remember: “Tulip, “Umbrella,” “Fear.”

The speech therapist says to me in the hospital, “I’m going to give you three words I want you to remember: “Rose,” “Sweater,” “Hamburger.”

I wonder: Does every series of three words I’m to remember begin with a flower?

I tell my neighbor’s teenage daughter a joke: “Why did the groundhog cross the road?” “To show the chicken it was possible.”

My neighbor’s teenage daughter tells me a joke: “What did one waiter say to the other waiter?” “We’re both waiters.”

Love resides in the most unexpected places, even in corny jokes.

“What did Baby Corn say to Mama Corn?” “Where’s Pop Corn?”

My cousin brings me apples from the orchard: yellow delicious and pixie crunch. She tells me a story about how after her father died, my aunt said to her, “I don’t know what to do with these guns.” My aunt, the retired junior high teacher, tatter of lace, painter of landscapes, collector of music boxes. My uncle, former public relations man, gentle tender of bird feeders, congenial teller of jokes, gracious host. Who knew they’d been packing heat? My aunt’s rifle. My uncle’s pistol. Certainly not my cousin, who tells me the pistol was in a wooden box on a book shelf in her parents’ living room, lo these fifty-some years. I remember that handsome box. I always thought it was one of my aunt’s music boxes.

Surprises, surprises. When my uncle was dying, he came back to consciousness toward the end and said, “Peaches, peaches. There’s a hole in Santa’s breeches.” At another point, he asked my aunt, “Mildred, how to you spell orange?”

What were those three words? Either series.

I type them now from memory: “Tulip, Umbrella, Fear.” “Rose,” “Sweater,” “Hamburger.”

I don’t plan on forgetting. Six small words. I’ll never hear one of them again without remembering how when the neurologist and the speech therapist gave them to me, I held onto them as hard as I could. I held them as if they were my life.

September 28, 2012

My Body Becomes a Lyric Essay

CEREBRAL ARTERY OCCLUSION, UNSPECIFIED; WITH CEREBRAL INFARCTION

The language of stroke. The language of my stroke. The doctors can’t pinpoint the exact cause, but they have a culprit under surveillance: a patent foramen ovale. When all of us are in the womb, there’s a natural opening between the left and right atria of the heart. This opening closes naturally when we’re born. But for about 25% of us, it doesn’t. I’ve had mine (if indeed I do have it; my cardiologist says the surface ultrasound sometimes picks up what it thinks is a hole in the heart, but it isn’t really, and he’ll have to do a different sort of test to know for sure about my suspected PFO), unknown to anyone, for 56 years. If indeed, this PFO is the guilty party, then it’s likely that’s how the blood clot traveled to my brain.

So what’s to be done about that pesky perhaps-hole? No one really knows whether it’s better to patch it or to instead manage the condition with medication. One clinical study has shown no difference in effectiveness. The results of a second clinical study are due in late October and will help dictate the direction of my treatment. It’s been a stark reality lesson in how the insurance companies control our health care. My cardiologist, one of the very best when it comes to PFOs, says he’d close every patient’s hole if it were up to him, but before the clinical studies show that the procedure is more effective than management with medication, he’d be called a quack.

I’m in a holding pattern, then (well, actually I’ll be wearing a small and portable heart monitor for 21 days to see if I have any atrial fibrillation before determining the next step).

It’s a time for going slow, for learning the language of blockages and holes and everything I can hear on the other side or passing through. Like a good lyric essay, something resonant rises up in the silence.

All I know for certain is how lucky I am to walk out of the hospital two days later with no impairments, how lucky I am to have so many people wishing me well. I love you all, love you with all of my heart, even with the possible hole, which your affection has already begun to fill.

September 17, 2012

Mad Libs for Creative Nonfiction Writers: A New Exercise

I designed a new writing exercise for my MFA creative nonfiction workshop last week, and contrary to what a good teacher should have done (stating the objective of the exercise before leading the students through it) I purposely eliminated that step and jumped right in. I didn’t want the students to write toward an objective, thereby thinking too much about the purpose of their responses to my cues. Instead, I wanted them to be open to leaps and associations and surprises and the texture such things can lend to a piece of creative nonfiction.

As promised, I’m now sharing this exercise with you:

1. Make a list of three adjectives. Any three. Don’t think too hard. Just do it.

2. Make a list of three objects that have recently become “unforgettable” to you in some way. Three objects from the current time or the recent past that you can’t get out of your head.

3. Make a list of three abstractions, but try to avoid nouns that could also be transitive verbs. Nothing that could be turned into a statement such as “I love x,” or “I hate y.” Stick with things like”limbo” or “harmony.”

4. Choose an adjective from your list, an object, and an abstraction. Do it in that order. Add a preposition or an article as necessary. Write the title of your essay (e.g. “Pretty Dog Leash in Limbo”). Note: now that you know you’re creating a title, feel free to switch out any of the words for others on your lists.

5. Write a few lines about the object you’re chosen. Why have you been thinking about it lately? Give us a context for why this object is important to you.

6. Write a few lines that evoke the abstraction you’ve chosen without naming it. How does the abstraction convey your emotional response to the object? In what way does thinking about the object leave you unsettled, uncertain, or whatever your emotional response turns out to be?

7. Write a few lines that evoke the adjective you’ve chosen without naming it. Give us a sense of its relationship to the object. Is it ironic, for example, or genuine?

8. Write a few lines about another object, story, or memory that comes to you right now. We’re working with free association here. Look for words or phrases or images that subtly connect to what you’ve already written. If you need a prompt, here’s one: “When I think of that dog leash, I remember (fill in the blank with another object, a story, a memory).”

9. Make a direct statement about where the second object, story, or memory takes you in your thinking. Here’s a prompt: “I begin (or began) to think about (fill in the blank however you’d like).” The emphasis with this last step is to let the texture of the writing invite an abstract thought, conclusion, question, speculation, etc., thereby allowing the central line of inquiry of the essay to grow organically from what precedes it.

Since this is a new exercise, I’m particularly interested in what you think. My students, in our post-writing debriefing, talked about how the exercise led them to unexpected connections, became a process of discovery, forced them to “push through” material that was a bit uncomfortable for them, and in general led them to things they wouldn’t have gotten to otherwise. I’m hoping this exercise will be helpful for those writers who want to write in forms that aren’t predominantly driven by narrative and who are more interested in dealing with recent material rather than the distant past.

September 12, 2012

The Thinginess of Life: Objects and the Writer

This morning, my Facebook friend, Susan Cushman (check out her blog, “(Not) Writing on Wednesdays” at http://susancushman.com/blog-pen-palette/), made me aware of a story she found on another blog, “HighRoadpost” by Lisa Joiner (http://highroadpost.com/). It’s the story of a book that Lisa found in the women’s room at LAX on a day when she and her husband had been flying standby, ending up in Los Angeles on their way to Santa Fe, though the LA stop hadn’t been in their original itinerary. But at LAX they were, and when Lisa found a book left behind by another traveler, she opened it to see if the owner’s contact information was inside. Indeed it was, so Lisa called the owner, who turned out to be an elderly woman traveling to a family wedding, and she told her she had her book, Heading Out to Wonderful, by Robert Goolrick. Lisa promised to return the book to its owner once she was back at home base, which she did, along with a letter detailing all the sights the book had seen along the way:

Just in airports alone, it saw Greensboro, Charlotte, Los Angeles, Phoenix, Albuquerque, San Diego and Sacramento. Then it went via land to Santa Fe, The Puye Cliff Dwellings, Taos, Red River and back to Santa Fe, New Mexico. It visited museums, art galleries, churches, pueblos, shops and restaurants. It was on the Old Santa Fe Trail and the Enchanted Circle Scenic Byway. I didn’t photograph it everywhere but took a few pictures so you would have a sense of its travels.

A few weeks later, Heading Out to Wonderful came back to Lisa, the owner mailing it along with a letter detailing her book club’s discussion of the book. Lisa decided to read the book and then pass it on to someone else. This humane contact with a stranger brought Lisa to this observation:” No matter where our journey is taking us we should remember we are always Heading out to Wonderful, wherever that may be!”

A few weeks later, Heading Out to Wonderful came back to Lisa, the owner mailing it along with a letter detailing her book club’s discussion of the book. Lisa decided to read the book and then pass it on to someone else. This humane contact with a stranger brought Lisa to this observation:” No matter where our journey is taking us we should remember we are always Heading out to Wonderful, wherever that may be!”

I’ve long reminded my students to remember what first brought them to writing, the love of language and the music it makes on the page, the stories it tells, the way it allows the writer to process the world and its people. The journey will, then, take us where we’re meant to go.

This morning, thanks to Susan Cushman, it seems that I was meant to make the acquaintance of Lisa Joiner, and soon after that to encounter a post from my former student and friend, Sonya Huber (check out her blog at http://sonyahuber.com/blog/), which refers to a review of Orwell’s diaries and points out the importance got the creative nonfiction writer exploring what the review calls “the thinginess of life,” or what Orwell called his “pleasure in solid objects.” The review says of Orwell: “Abstractions, he knew, were the enemy of the powerless. They destroyed the diverse particulars of everyday life and necessarily culminated in some type of inhumanity, killing people for the sake of the idea.”

This morning, thanks to Susan Cushman, it seems that I was meant to make the acquaintance of Lisa Joiner, and soon after that to encounter a post from my former student and friend, Sonya Huber (check out her blog at http://sonyahuber.com/blog/), which refers to a review of Orwell’s diaries and points out the importance got the creative nonfiction writer exploring what the review calls “the thinginess of life,” or what Orwell called his “pleasure in solid objects.” The review says of Orwell: “Abstractions, he knew, were the enemy of the powerless. They destroyed the diverse particulars of everyday life and necessarily culminated in some type of inhumanity, killing people for the sake of the idea.”

I’ve been talking in my creative nonfiction workshops lately about trusting the details, or now what I’ll call “the thinginess.” The objects of a life become expressive when rendered artfully. The objects portray an individual’s life and make us care more about what was important to that person whether we’re talking about real people from nonfiction or characters in a story or a novel. The things matter if we look at them closely enough, and they keep us anchored in the world of flesh and blood. That world is easier to dismiss when the emphasis falls on abstractions, and, when that happens, wars break out, health care declines, safety nets for the marginal disappear, because, after all, the world of ideas is rarely a world of the human heart.

Susan Cushman, Lisa Joiner, Sonya Huber, George Orwell: all of them come together today to remind me of the journey and the value of a well-considered and closely observed life. To remind us all, I hope, of why the individual and the objects that belong to them matter, not only for our writing, but for our living as well.

September 5, 2012

Nostalgia and the Memoirist

Last week in my MFA creative nonfiction workshop, the issue of nostalgia in memoir came up, and we explored the question of how a memoirist can deal in nostalgia without becoming nostalgic. Hmm. . . that may at first sound like a goofy question to chase around the workshop table, but please bear with me.

The word, nostalgia, has its roots in the Ancient Greek word for “a return home.” We define it now as a longing for home or familiar surroundings; a homesickness; a yearning for things of the past.

At the risk of stating the obvious, all writers of memoir deal with the things of the past; all memoirists, then, are in some way returning “home.” This journey carries with it a certain degree of risk. Memoir goes sour quickly, its falseness showing through, once it’s clear that the writer’s impulse is to celebrate, to romanticize, to indulge in sentimentality.

Such is sometimes the case in the dreams I often have of the farm in southeastern Illinois where I spent my early years with my mother and father. In those dreams, the house, which is now in ruins, has been rebuilt. My parents’ youth and health have been restored. The grass is green, the birds are singing, and happiness reigns. You get the idea: everything is peachy-keen. But that’s only one part of the lives we all lived in that farmhouse; my dreams conveniently edit out the struggles, the yearning, the anger, the suffering, the embarrassment of people who loved one another but who often fell short of that love. Apparently, there’s no room in my dreams for those truths. Maybe that’s because I’ve made a place for them in the memoirs I’ve written.

To deal in nostalgia without becoming nostalgic, a writer has to be honest, has to see the entire palette of the experience, both the bright colors and the dark ones. As is the case with almost any craft issue connected to a piece of writing, help comes in the form of this question: What was the impulse that first brought the writer to the page? In memoir, that impulse can’t be a nostalgic one, can’t be an intent to romanticize; a memoirist’s intention must be to see the self and the other people in his or her world with a clear eye, one meant for the honest exploration of the multiple layers of human experience.

Which brings me to Ted Kooser’s essay, “Small Rooms in Time.” This is an essay about a murder that takes place in a house where Kooser and his family lived before the divorce that sent them in different directions. Kooser says of the murder:

It’s taken me a long time to try to set down my feelings about this incident. At the time, it felt as if somebody had punched me in the stomach, and in ways it has taken me until now to get my breath back. I’m ashamed to say that it wasn’t the boy’s death that so disturbed me, but the fact that it happened in a place where my family and I had once been safe.

Notice how the essay bravely wades into nostalgia (“a place where my family and I had once been safe”), but it does so with a point of emphasis on uncomfortable honesty (“I’m ashamed to say that it wasn’t the boy’s death that so disturbed me”), thereby signalling the unflinching eye that will guide us through this return home.

At one point in the essay, Kooser talks about how since the murder that house has become permanently clear to him:

Since the murder I have often peered into those little rooms where things went good for us at times and bad at times. I have looked into the miniature house and seen us there as a young couple, coming and going, carrying groceries in and out, hats on, hats off, happy and sad.

It’s the honest admission of the bad times in concert with the good, the sad with the happy, that earns Kooser the right to remember in loving detail the facts of the life he lived in that house; it allows him to deal in nostalgia without becoming nostalgic. His intention isn’t to romanticize but to deal honestly with the circumstances and the effect, years later, that the murder has wrought on his memory of the past and his notion of himself in the present. Because he admits the sometimes unhappiness of his young family, we believe what he says thereafter. Of the house, he says,

The murder brought it forward and made me hold it under the light again. Of course I hadn’t really forgotten, nor could I ever forget how it feels to be a young father, frightened by an enormous and threatening world, wondering what might become of him, what might become of his wife and son.

The lesson for those of us who write memoir? Admit it all, every aspect of whatever “home” we’re revisiting, and then state the details, present the objects that furnished our rooms, simply and plainly without commentary. The resonance of the rugs, the sofas, the paintings, the draperies, the empty chairs, will come from the fact that we attach nothing to them except the truth that we were, even in that place and time, imperfect.

August 27, 2012

Making a Scene in Bowling Green: Writing Memoir

When I was a boy, my mother often said to me, “Don’t make a scene.” So I grew up to be a writer in part, perhaps, so I could make all the scenes I wanted. When we write narratives, whether fictional or the personal narratives of memoirs and essays, we need to give ourselves permission to make a scene.

Over the weekend, I had the pleasure of teaching a memoir writing workshop at the Warren County Public Library in Bowling Green, Kentucky. (A big shout-out here to the wonderful folks of Bowling Green and thereabouts who pushed the membership of my Facebook Fan Group to over 500; I Heart Bowling Green!) Here’s a link to the fan group on Facebook in case anyone else is interested in joining: https://www.facebook.com/groups/14139544589/?notif_t=group_r2j

During the workshop, we used objects from childhood (shoes, toys, scents, etc.) to recall pivotal moments from our pasts. The we crafted scenes that invited the reader into the writer’s memory and focused upon a moment of emotional resonance and complexity.

When people shared what they’d written, I heard stories of envy, desire, joy, disastrous circumstances–human moments, all of them shaped and delivered in a way that made me feel and feel deeply what the writers had felt when they lived through those moments.

When people shared what they’d written, I heard stories of envy, desire, joy, disastrous circumstances–human moments, all of them shaped and delivered in a way that made me feel and feel deeply what the writers had felt when they lived through those moments.

Here are some reminders for writers of personal narratives:

1. Make sure that you’ve chosen an episode that was somehow outside the regular come and go of an ordinary day, an episode that includes a climatic moment beyond which life was never quite the same.

2. Set the scene right away in space and time and give us a sense of what the main characters carried with them into the scene. That emotional baggage plays a huge part in the characters’ actions and reactions.

3. Include enough sensory detail to draw your reader into the scene. Remember that memoir isn’t only a record of what happened. It’s a chance to put your readers into your shoes. A scene is built from small details. Don’t neglect them.

4. Use the reflective voice of the writer at the desk to flesh out the complicated layers of the scene and how they played a role in shaping that writers’ life. Remember that you’re always a participant in the scene (the you of a younger age), but you’re also the narrator looking back and making meaning from what happened.

5. Use dialogue and action to move the scene to its climax. This is all part of making the readers feel that they’re with you in that moment.

Virginia Woolf said it wasn’t the thing that happened that mattered the most, but what the writer is able to make of the thing that happened. So, make a scene, and see where it takes you in your thinking about how you came to be who you are in the here-and-now. Make a scene so your readers can participate in it. Step back from the scene, providing a voice-over as such, as you speak from the adult perspective, the person who is capable of knowing now what you didn’t know then. Finally, some advice, taken from a sign on the wall of the room we used at the Warrn County Public Library. Some good sense advice for all of us:

Thanks for a wonderful time, Bowling Green!

August 21, 2012

Taking Care at the End: The Art of Misdirection

I just got back from teaching in the Vermont College of Fine Arts Postgraduate Writers’ Workshop, and I wanted to give a recap of the craft class that I taught. The session was called “Taking Care at the End: The Art of Misdirection.” So please permit me a digression. The photo below was taken by my conference colleague, Dinty Moore, as I crossed the street soon after my craft class. Do I look surprised? Or am I simply mugging for the camera? Or both? Perhaps I’m simply surrendering, as we do at the end of a good story, poem, novel, essay. Perhaps, I’m saying, “Okay, you got me. I didn’t see this coming, but now here it is.” The end of a good piece of writing has that feeling of simultaneous surprise and inevitability. The turn at the end catches us by surprise and we say, “Ah, of course,” because it has the ring of a truth that’s been artfully delivered. The question, then, is how can we set out on this covert operation? How can we catch our readers unaware as we spin a narrative opposite from the one they think they’re reading, allowing that submerged story to fully surface at the end?

I believe I’ve written a bit about Brian Hinshaw’s brilliant piece of flash fiction, “The Custodian,” before on this blog, but it warrants looking at again. The story is told in two paragraphs. Here’s the first one:

The job would get boring if you didn’t mix it up a little. Like this woman in 14-A, the nurses called her the mockingbird, start any song and this old lady would sing it through. Couldn’t speak, couldn’t eat a lick of solid food, but she sang like a house on fire. So for a kick, I would go in there with my mop and such, prop the door open with the bucket, and set her going. She was best at the songs you’d sing with a group–”Oh Susanna,” campfire stuff. Any kind of Christmas song worked good too, and it always cracked the nurses if I could get her into “Let It Snow” during a heat spell. We’d try to make her to take up a song from the radio or some of the old songs with cursing in them, but she would never go for those. Although once I had her do “How Dry I Am” while Nurse Winchell fussed with the catheter.

In the opening, we meet a narrator (I’m going to assume it’s a man though the story never specifies the gender) who works as a custodian in a health care facility. To keep the job from being too boring, he gets the patient in 14-A to sing, the only verbalization apparently that she’s capable of. There’s some lightness of tone in the opening. It’s apparent in the language: “mix it up a little,” “sang like a house on fire,” “it always cracked the nurses,” etc. At the end of the first paragraph, we learn that the custodian once had the woman sing “How Dry I Am” while a nurse attends to the patient’s catheter. When I read this story aloud, people generally laugh at that line and then in our conversation that follows, they admit to feeling guilty about laughing because they’re aware that the custodian may be dehumanizing the patient. I’d suggest that we haven’t been aware of the submerged story, the one that’s quite opposite from the one suggested by the opening lines, but at the very end of the first paragraph, that submerged story begins to rise.

Here’s the second and final paragraph of the story:

Yesterday, her daughter or maybe granddaughter comes in while 14-A and I were partways into “Auld Lang Syne” and the daughter says “oh oh oh” like she had interrupted scintillating conversation and then she takes a long look at 14-A lying there in the gurney with her eyes shut and her curled-up hands, taking a cup of kindness yet. And the daughter looks at me the way a girl does at the end of an old movie and she says “my god,” says “you’re an angel,” and now I can’t do it anymore, can hardly step into her room.

Notice what happens with language in that first sentence. The immediate pause after “Yesterday,” signals a shift in tone from the lightness of the first paragraph to the gravity of the second one. The submerged story, as it surfaces, requires a more contemplative tone. As that first sentence unwinds contains more than one pause, and actually we might argue that the second sentence is really a continuation of the first. Of course, there’s a great misreading in what the daughter thinks of the custodian. She thinks he’s doing something good by bringing a few moments of regular life and joy to the patient by getting her to sing. The daughter sees this as a completely beneficent act on the part of the custodian. He knows, though, that his motive hasn’t been beneficent at all but instead self-serving, a way of warding off the boredom. He feels so ashamed, he can’t continue, can hardly step into 14A where the patient will no longer have the opportunity for that singing. Is that a good thing? A bad thing? Both? The answer becomes complicated, the way it always does at the end of a good story that captures some simultaneous loss and gain. Perhaps, the custodian’s actions, though selfish in nature, actually did create something positive for the patient. Or perhaps, his action was so wrong, it’s a good thing that he’s stopped. It seems to me that once the submerged story fully rises, it’s impossible to privilege one interpretation over the other. A binary has been leveled, and the ending resonates with the complexity of truth made possible through Brian Hinshaw’s art of misdirection. We thought we were reading a story about a custodian who had no thought of what he might be doing when he got the patient to sing, but really we were reading, as the ending proves, a story of a man coming to an awareness of how someone else interprets his action, choosing to think of him as an angel, but at the cost of him never again wanting to get 14A to sing. A very complicated human story has fully arrived through the scrim of a more simple story of self-interest.

At some point, we all need to experience what it feels like when a narrative takes a surprising and resonant turn. We need to put into practice a story that begins leaning one direction, only to lean in the opposite direction at its end. The opposite story, or the submerged story, rises within the structure of the primary story, the one we think we’re reading. The pressure of plot (notice how the third character, the daughter, becomes the final catalyst necessary to the submerged story becoming visible) forces that submerged story to the top. Dramatic irony, in this case accomplished through the daughter’s misreading, provides an opposite result to what the custodian intended, bringing him to a different view of himself and the world around him. That world changes in a profound way that resonates with readers. It’s as if a gong sounds and the sound waves reverberate back through the story and on into the future beyond the story’s end. Simply put, we can’t forget it because it arrives in such a covert but totally genuine way.

If you’d like to put all of this into practice, think of a job that you had that could get boring or that you wanted to be done with. What did you do to “mix it up a little?” How can you imitate Hinshaw’s story? Two paragraphs, one that establishes the surface story and then signals the submerged story beginning to rise at the end of the first paragraph, and one that allows that submerged story to fully rise. How can you use a third character as a catalyst? How can you used a misreading to lead us to an ironic and resonant end?

August 12, 2012

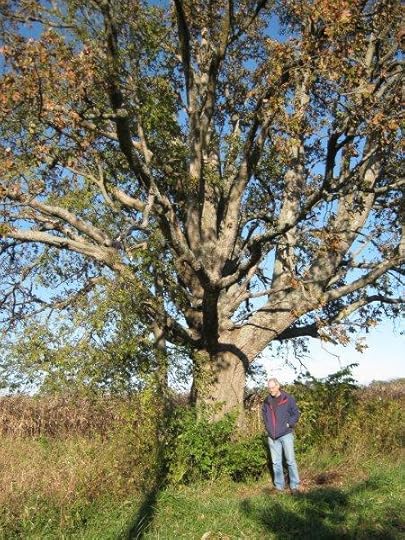

That Kind of Place: An Argument for Nostalgia

Why is it, once you reach a certain age, that Sundays are loaded with nostalgia? Today, I’m thinking of summer Sundays when I lived on our farm in southeastern Illinois. I’m talking about an eighty-acre plot of land on the Lawrence County side of the County Line Road. Eighty acres of clay soil in Lukin Township that my father planted in wheat, soybeans, and corn. The roads ran at right angles, mostly in straight lines. The fences did the same. A lane ran east from the County Line Road and led to our farmhouse on top of a gentle rise shaded by two maple trees and a giant oak.

I was the only child of older parents, my mother being forty-five and my father forty-one when I was born. As many of you know, he lost both of his hands in a corn picker when I was barely a year old. He was fitted with prostheses, and he continued to farm. My mother, who was a grade school teacher, helped him when she could. I had friends who lived on the next farm to our north, and we played together, but I spend a good deal of time on my own, left to entertain myself.

An oak tree stood beside our mailbox at the end of the lane. Here’s a picture of me standing in front of it earlier this year.

So many days, I stood in the front yard of our home and looked down the lane toward that tree, hoping beyond hope that I’d see a cloud of dust rising up from the road, a sign of a car coming, and I’d hope that car would slow and turn into our lane and come to pay a visit because out there in the country, particularly on those hot days when summer had nearly worn you down, you could get anxious for a change of pace, and a little company, particularly if that meant other kids to play with, was just the ticket.

The flat land sectioned off into blocks of fields; the roads running straight and squared; a tree like this to shade the mouth of a lane that led to a house where on Sundays, after a week of hard work, people were at rest. When I was a boy, this was my tribe: my mother and father, and the aunts and uncles and cousins who came to visit after church services were done. They came bringing angel food cakes, and Jello salads, and sugar pies, and hot dishes of baked beans and chicken and noodles, and cold ones of potato salad and slaw, and we sat down around the table to eat. My childhood was so often a time of hoping that someone might come to call, someone who would break through the fenced in squares of land and jumble things up a tad. I could even get excited when our cows sometimes got loose, somehow got beyond the barbed wire, and ended up in our yard or out on the County Line Road, or over in some other farmer’s pasture. I loved the fact that the ordinary all of a sudden seemed strange. Seeing a Jersey cow by my rope swing that hung from the maple tree in front of our house? Now that was something outside the regular come and go.

My father must have sometimes felt that same desire to break free. One Sunday, toward evening, when it was nearing time for all the company to pack up and leave, he said he bet he could beat me in a race. I must have been six or seven at the time, which means he would have been forty-seven or forty-eight. The numbers of his age meant nothing to me at the time, but I was always aware that he and my mother were much older than the parents of my friends, and, of course, I’d learned the stares people gave my father’s prosthetic hands. I knew that he was an oddity.

Which may explain why he challenged me to that race. Maybe he was tired of the role he’d been cast into because of his accident. Maybe he felt the freedom of a Sunday afternoon dwindling down with evening chores soon to come and then another week of work in the fields. Maybe he wanted, at least for a brief time, to be free of all of that. A race. Something he could do with his legs. Something he could do with his son just the way other, younger fathers, did.

I was delighted. It was, perhaps, the first time my father had seemed like other fathers to me. We raced across the yard. I laughed as I ran. My father lumbered past me, and I laughed to see him run. Then, at the finish line, he slipped. His feet went out from under him and he fell on his back, embarrassed, hurt, and I stopped and watched while my uncles helped him up, and I felt an ache in my throat because I’d caused all of that to happen just by being alive.

Often, these days, I wonder whether young writers know their own tribes well enough. We should all pay attention to our communities, our landscapes, so we can see how our characters act from either their sense of belonging or a resistance to the geography and the culture. We need to understand that our people and the places they occupy are never separate. We need the sort of intimate knowledge of people and places that the nostalgic impulse can bring.

When I was a boy, I lived in the kind of place where a man could try to escape all that yoked him to the land and to the limitations of his own body, the kind of place where his son could feel ashamed for coming to his parents so late in their lives. My mother and father and I and all the people around us: We lived in a place like that.

August 8, 2012

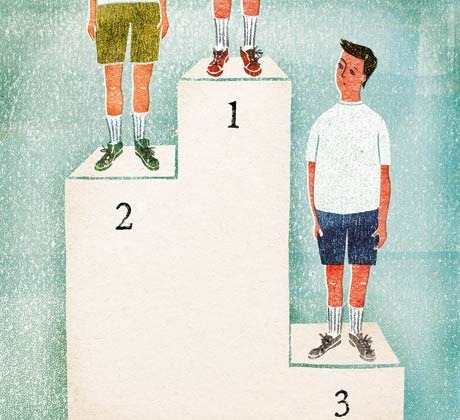

Klout: Online Influence and What It Means to Writers

Remember those high school days when you were always worrying over your popularity even if you acted like you weren’t, when you were trying to define a workable identity for yourself: a jock, a cheerleader, a stoner, a loner, a straight arrow, a good citizen, a lover, a fighter, and the list goes on. Remember those days when you were trying to find a position from which you could become relevant to other people, those days when you wanted to find a way to have clout? Brace yourselves if you’re a writer: those days are back.

Remember those high school days when you were always worrying over your popularity even if you acted like you weren’t, when you were trying to define a workable identity for yourself: a jock, a cheerleader, a stoner, a loner, a straight arrow, a good citizen, a lover, a fighter, and the list goes on. Remember those days when you were trying to find a position from which you could become relevant to other people, those days when you wanted to find a way to have clout? Brace yourselves if you’re a writer: those days are back.

In the era of social media, if you’re on Twitter, Facebook, etc., you’re leaving a trail by which people can gauge your degree of online influence over others. In other words, we can now see how much sway we have. We can see how well our “platforms,” in the parlance of the times, are working. Trying to promote a new book? How many people are you reaching with your Tweets, for instance, and how many people are re-tweeting what you’ve tweeted? How many people are talking about you and your book? How broad is your reach? How much clout do you have? Now you can find out, and, if you can find out, so can agents, editors, and publishers.

I learned all this earlier in the week when my friend Debra Jasper, a social media expert who co-founded Mindset Digital, a company that helps people reach more clients, customers, etc., told me about Klout.com, and how to find out what my Klout score was. So I went to the web site and found out my Klout, on a scale of 1-100 (Justin Bieber has a Klout score of 100), was 1. Imagine that moment in high school when your friend says, “So, you coming to the party Saturday? You know, Gary Goldenboy’s party, the one everyone who is anyone will be at?” and you swallow and say, “What party?” That’s sort of how I felt when I found out my Klout score was 1. I didn’t even know whether this was something I should worry about; I only knew I felt excluded.

I learned all this earlier in the week when my friend Debra Jasper, a social media expert who co-founded Mindset Digital, a company that helps people reach more clients, customers, etc., told me about Klout.com, and how to find out what my Klout score was. So I went to the web site and found out my Klout, on a scale of 1-100 (Justin Bieber has a Klout score of 100), was 1. Imagine that moment in high school when your friend says, “So, you coming to the party Saturday? You know, Gary Goldenboy’s party, the one everyone who is anyone will be at?” and you swallow and say, “What party?” That’s sort of how I felt when I found out my Klout score was 1. I didn’t even know whether this was something I should worry about; I only knew I felt excluded.

So I got to work. By listing a few areas of expertise on my Klout.com profile and then choosing some folks on Twitter that I felt were influential to me, I saw my score increase immediately to 33 and from there in just a few days to 52. How did this happen? I confess I have no idea. Furthermore, I still don’t know whether this is something I should keep paying attention to (will it affect my career?) or is it something I should sweep aside the way we all should have saved our energies worrying over our high school image and just got on with the business of living our lives and being true to ourselves.

The question is whether agents, editors, and publishers are starting to make decisions about which writers to represent or publish based on the online influence indicated by the data collected and analyzed by places like Klout.com. I went looking for answers, and here’s what I found, compliments of Meghan Ward’s blog, WRITERLAND. (I just decided to follow Meghan on Twitter, and I’ll most likely tweet a link to this information from her blog, setting into motion who knows what as far as both of our Klout scores.)

At any rate, here’s what a few agents and editors had to say:

Danielle Svetcov, literary agent with Levine Greenberg Literary Agency

“I’d never heard of Klout til you mentioned it. Now I will use it. This is how it always seems to work: Every time the Web gives us a new way to measure influence and sway in the marketplace, we have a new variable to factor into our picking and choosing. This can work in a writer’s favor if he/she is gifted in the influence and sway depts., and if the subject of the book (almost always non-fiction) is the area in which the writer has power and sway. If, however, the writer is simply gifted as a writer, and has terrible Klout, Twitter, Facebook scores, then those measurements may actually misdirect the gatekeepers (me, editors, etc). In short, Klout, Twitter, and Facebook can sometimes be very helpful for determining the potential audience of a book (and therefore an appropriate advance), but I’d be scared if they became the sole determiners of the future’s literary voices.

(Social media influence is coming into play in every genre. It’s become quite essential for selling non-fiction; it’s not so essential for fiction, but I’m sure if a fiction author had 20,000 Twitter followers, the writer’s agent wouldn’t fail to mention it in her submission letter to editors. Depends what kind of book it is. I wouldn’t usually do this for fiction, but for nonfiction where platform matters more, I would.)”

Michelle Brower, literary agent with Folio Literary Management.

“Honestly, this is the first time I’ve heard of a Klout score, so the answer would be, for me, “not at all”! I work with many fiction and narrative writers, where style and story are really my biggest criteria. I’ve found that social media can help spread the word about their books, but in and of itself doesn’t affect my client decisions.”

Daniela Rapp, Editor at St. Martin’s Press

“We do take authors’ social media platforms into very serious consideration, but as far as I know we don’t use an overall score to determine their “clout,” but rather look at their number of Twitter followers, Facebook fans, Web site hits or blog popularity. And in the end, no matter how high their score may be, if we don’t love the project, we won’t sign it up just because the author happens to be popular.”

Mollie Glick, literary agent with Foundry Literary + Media

“Depends what kind of book it is. I wouldn’t usually [look at Klout scores] for fiction, but for nonfiction where platform matters more, I would.”

In high school, I was never much of a joiner. I played basketball and wrote for the student newspaper. I performed in the junior class play, but I was never the sort who wanted to be a part of this clique or that one. So I’m amazed that I’m thinking about this topic of social media and online influence and the way it might come to bear on my life as a writer. The two worlds seem so opposite, but maybe they’re not. Maybe they’re both creative enterprises. I’d love to hear what others think, as I continue to think about the lay of the digital land and how it rubs up against the solitary time I spend in my writing room.

In high school, I was never much of a joiner. I played basketball and wrote for the student newspaper. I performed in the junior class play, but I was never the sort who wanted to be a part of this clique or that one. So I’m amazed that I’m thinking about this topic of social media and online influence and the way it might come to bear on my life as a writer. The two worlds seem so opposite, but maybe they’re not. Maybe they’re both creative enterprises. I’d love to hear what others think, as I continue to think about the lay of the digital land and how it rubs up against the solitary time I spend in my writing room.

July 30, 2012

Martin and Dean: A Mashup

I’ve just returned from teaching at the Midwest Writers Workshop in Muncie, Indiana. What a wonderful gathering of writers! While I was there, I also had the privilege of delivering the keynote address as well as the opportunity to visit the land of James Dean in Fairmount, Indiana. Some folks have been asking whether I could post my keynote address, “Does Your Mother Know You’re Reading This?: Becoming a Writer in the Midwest.” Well, it’s a bit long, methinks, for a blog post, but I thought I might be able to share a little of it while at the same time talking about my fantastic day visiting Fairmount (Thank you, Cathy Shouse). All my life, people have mangled my name, calling me either Lee Marvin or Dean Martin, so why not a Lee Martin/James Dean mashup. Here goes.

My keynote included this story:

My keynote included this story:

My father, though he believed in education and expected me to do well in school, could have lived his life just fine without books. Still, somehow when I’d learned to read, I became a member of a children’s book club that published what they called Junior Deluxe Editions. They were wonderfully illustrated, but they were much more than story-books. They were novels with the size and bulk of the books that grownups read. The Junior Deluxe Editions were books like Alice in Wonderland, Captains Courageous, At the Back of the North Wind, Kidnapped, Hans Brinker, Penrod and Sam. I believe the club must have operated as any book club does, so many to buy and featured selections mailed to you if you failed to decline them.

One day, I was in my father’s truck while he was doing some sort of field work. There was a place behind the seat where he could keep tools and whatnot. I particularly liked the red flags he kept there, flags on short dowel rods that were meant to be used in the case of a road emergency. I was reaching for them that day, when I felt the square edges of a box. I pulled it out and saw that it was just the right size to hold. . .you guessed it. . .a book. I couldn’t resist. I tore it open to find inside a Junior Deluxe Edition of The Prince and the Pauper, a book that my father intended to return, having decided, I suppose, that my collection was as complete as it was going to get.

It occurs to me now that someone enrolled me in that club and someone chose those books for me, as I surely didn’t make the selections myself, and that person could have been no one other than my mother. She was, in a sense, building a library for me, an effort that my father decided to short-circuit. My mother didn’t even know the book had come until I showed it to her.

My father was angry, and somewhat ashamed because he’d been caught hiding it. “Are you going to keep it?” he asked my mother.

“Well, it’s been opened,” she said. “I hardly think we have a choice.”

James Dean grew up in this house just outside Fairmount, Indiana, after the death of his mother when he was nine years-old. This was the farm of his aunt and uncle, and this is where Dean lived until graduating from high school and then going to California where his farther lived. He attended college for a while and then went to New York to study acting. The rest we know: leading roles in three major motion pictures (East of Eden, Rebel Without a Cause, and Giant) before his tragic death at the age of 24 in a car crash in California on September 30, 1955.

James Dean grew up in this house just outside Fairmount, Indiana, after the death of his mother when he was nine years-old. This was the farm of his aunt and uncle, and this is where Dean lived until graduating from high school and then going to California where his farther lived. He attended college for a while and then went to New York to study acting. The rest we know: leading roles in three major motion pictures (East of Eden, Rebel Without a Cause, and Giant) before his tragic death at the age of 24 in a car crash in California on September 30, 1955.

I like to think of this orphaned boy growing up in a small town in the Midwest while dreaming of brighter lights, bigger stages, missing his mother who always encouraged his creativity.

Again, from my keynote:

We [Midwesterners] could be as wary of those who visited us from afar as we could those who’d left us and gone off to make lives in the cities—sometimes even in foreign lands. In our less flattering moments, we thought those expatriates uppity, their absence a comment on the inadequacy of our provincial lives. Although we took pride in our children and dreamed good lives for them, we sometimes stopped short in what we could imagine. We wished for our daughters jobs as nurses or schoolteachers. We wished for our sons the inheritance of our farms or steady work at the refinery. We went on reading our Bibles, our newspapers, our seed catalogs, our farm implement manuals, our Reader’s Digests, our Family Circles and Better Homes and Gardens, our Enquirers, our Grits. Oh, sure, someone probably read the classics or contemporary novels—I know I’m generalizing—but for the most part we were communities who didn’t give much thought to the literary life. In fact, I’m fairly certain we sometimes stood on guard against the dangers of a life of the imagination, which stood in stark contrast to the level-headed horse sense we valued. We didn’t chew our cabbage twice, didn’t burn our bridges behind us, didn’t count our chickens before they hatched, didn’t look a gift horse in the mouth, didn’t try to teach a pig to sing.

Here I am, giving a signed copy of my novel, Break the Skin, to conference participant, Rebecca Watson. She’s only been writing a few months, but she has dreams of writing for a lifetime. The conference was full of such dreams. Sometimes I wonder whether the Midwest conditions us to be ashamed of our dreams for fear that people will think us overly ambitious or proud for believing that we can achieve our goals. I say, dream big. I say, follow your heart.

Here I am, giving a signed copy of my novel, Break the Skin, to conference participant, Rebecca Watson. She’s only been writing a few months, but she has dreams of writing for a lifetime. The conference was full of such dreams. Sometimes I wonder whether the Midwest conditions us to be ashamed of our dreams for fear that people will think us overly ambitious or proud for believing that we can achieve our goals. I say, dream big. I say, follow your heart.

Again, from the keynote:

One day, I walked into the small lending library that had come to our little town. To this day, I love the leisurely feeling of strolling down the aisles in a library, just to see what I can see. At the time I’m remembering now, public libraries—even that small lending library—were almost holy, so sacred that they required hushed voices. If you spoke at all, it was in a whisper. There were no cell phones ringing, as there are now, no beep-beep-beep of the bar code scanning self-checkouts, no clacking of computer keys, no full-throated voices at the reference desk. Oh, listen to me go on, old fuddy-duddy that I am. The libraries of my youth were places of supplication, places where you stood humbly in the midst of all those books. Places of reverence.

Even if the book was Jacqueline Susann’s Valley of the Dolls, the 1966 bestseller that Amazon.com now describes as an “addictively entertaining trash classic,” a novel of “sex, drugs, and schlock and more.” One of the most commercially successful novels of all time, having sold more than 30 million copies. I didn’t know any of that when the book caught my eye that day. Maybe it was the bold white letters on the black spine that first drew me to it. Maybe it was the sound and rhythm of the title. The front of the jacket was white with the title and the author’s name in black and gray letters. Brightly colored capsules—yellows, reds, blues—the “dolls” of seconal, nembutal, and amytal dotted the cover as if someone had left them scattered there. For whatever reason, I opened that book and read the first paragraph: “The temperature hit ninety degrees the day she arrived. New York was steaming—an angry concrete animal caught unawares in an unseasonable hot spell. But she didn’t mind the heat or the littered midway called Times Square. She thought New York was the most exciting city in the world.”

I was hooked. I’d never been to New York, but someone, this character, Anne, had just arrived there and she thought it was wonderful. A journey had begun, and I wanted to know who Anne was, why she’d come to New York, and what would happen to her while she was there. It didn’t matter to me that the novel was a bestseller or that people had sat in judgment of it. All I knew at the time was it was the start of a story, and it promised to take me somewhere I wasn’t able to go on that hot day in Sumner, Illinois. All I had to do was check it out.

And that’s where the problem came.

The librarian was a woman who lived on our street. I’d always thought her a kind woman, pleasant and quick with a smile and a good word. Her name was Rose and she had black hair curled on top of her head.

She took one look at Valley of the Dolls, and she pressed her lips together in a tight line and looked at me over the top of her glasses. When she finally spoke, she was stern.

“Does your mother know you’re reading books like this?”

For a moment I was flummoxed by the question. I hadn’t had any feeling of shame about checking out that book until she asked me that question. The only thing I knew to do was to tell the truth.

“My mother lets me read whatever I want,” I said.

I imagined that Rose was forming a new impression of my mother, then—not a good one, and I was sorry about that. But it was true. My mother was never afraid of what I might encounter between the covers of a book. She trusted me to recognize and to discard the books that were lacking in merit. Perhaps, it was the way I answered Rose, in a voice that managed to calmly state the fact while at the same time indicating how surprised I was that she had asked the question in the first place. Suddenly, she was the one ashamed.

She took my card. She penciled in the due date on the checkout slip glued inside the back cover. I read Valley of the Dolls, and as far as I can tell it did me no harm.

I end with this story as a way of saying how thankful I am that I had a mother who loved reading and who invited me into the world of the imagination. How thankful I am that she opened the world of books to me and never tried to close my mind or my heart to any corner of that world. She wanted it to be mine in its entirety. Who knows what I might have missed, had she felt otherwise.

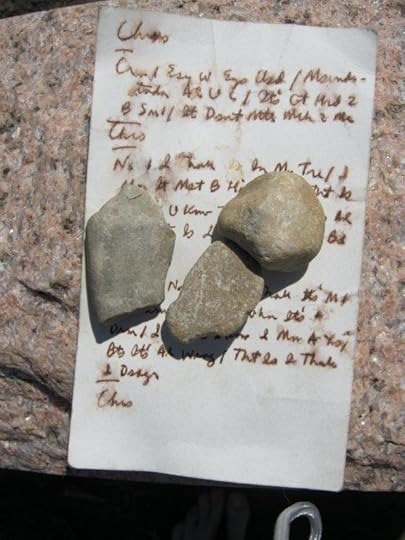

The above image is of a note left on the headstone at James Dean’s grave in Fairmount. I confess to not being able too make out the weathered scribble, but I’m glad it’s there, this note I’ll wager came straight from the heart. Here’s something that Dean said about acting: “To grasp the full significance of life is the actor’s duty, to interpret it is his problem, and to express it is his dedication.” Sounds like a good description of the writer as well.

The above image is of a note left on the headstone at James Dean’s grave in Fairmount. I confess to not being able too make out the weathered scribble, but I’m glad it’s there, this note I’ll wager came straight from the heart. Here’s something that Dean said about acting: “To grasp the full significance of life is the actor’s duty, to interpret it is his problem, and to express it is his dedication.” Sounds like a good description of the writer as well.

So a toast to all of us dedicated to the willed word on this day when I think of James Dean leaving Fairmount, setting out to find what might be waiting for him in the larger world. Actors, writers, dreamers from the Midwest. Reach far and high. Find your way to what pleases you.