Lee Martin's Blog, page 67

December 11, 2012

A Day at the Hospital

7:00 am: The woman at registration gives me an A+ for having all my paperwork properly filled out and ready to present. I don’t tell her I’m a teacher. I don’t tell her I have to believe that following all the rules will mean everything will work out just fine for me on this day when I’ve come to Riverside Methodist Hospital, so my cardiologist can confirm the presence of a suspected hole between the atria of my heart, and, if feasible, close it.

8:30 am: The nurse prepping me for my transesophageal echocardiogram says, “Your TEE was scheduled for 8 o’clock. I’m waiting for your blood chemistry before we go. I don’t complain. I’ve taken two Plavix and a baby aspirin to make my platelets nice and slippery so they won’t clot around the closure device, if indeed the second procedure is needed. In my head, I keep saying, “nice and slippery,” like a mantra meant to ease me through this day.

10:00 am: TEE time. A different nurse comes to wheel me to the room for the transesophageal. As she pushes my gurney down the hallway, I try out a joke on her. “What did the snail say while riding on the turtle’s back?” I lift my arms in the air, feel the air on my palms. “Wheeee,” I say, and the nurse laughs. I’ll remember her later in the day.

10:45 am: “Swallow,” the doctor, one of the associates in my cardiologist’s practice, says. “I need you to swallow the tube.” They’ve promised me that they’ve started the sedative that will send me into twilight, though I’ll have to be responsive to her command to swallow the tube and later to cough, so she’ll be able to hear and see if blood shunts from my right atrium through the suspected PFO into my left atrium. “Swallow,” she says, but I can’t. “We’ll try a pediatric tube,” she says, but still I can’t. I can’t swallow the tube, and, therefore, the TEE can’t be done, which leaves my cardiologist knowing no more than he already did about my heart. There’s talk of ordering an endoscopy to access the condition of my esophagus. There may be strictures or a narrowing of the esophagus that’s making it difficult for me to swallow the tube. The nurse is wheeling me back to the prep room, only this time I’m telling her no jokes; I’m not raising my arms in the air.

11:15 am: “ I guess I failed the first test,” I tell my cardiologist when he visits me in the prep room, saying he understands there was a problem with the TEE. “If they do an endoscopy,” he says, “I won’t be able to go into your heart today.” He tells me there are two options: do the endoscopy or let him do the closure procedure. I ask him whether the procedure will give him the information he’ll need in order to decide whether to close the hole he suspects is there. He tells me it will. I’ve come this far. I want something accomplished on this day. “Let’s do it,” I tell him. “All right, then,” he says. “I’ll get things ready in the cath lab, and we’ll see what we’ve got.”

12:20 am: I’m in the cath lab and everything is in place for the procedure. My cardiologist enters in his scrubs. He puts a hand on my shoulder. “Okay, buddy,” he says. “Let’s get to work.”

12:30 pm: My cardiologist says, “I’m definitely in the left atrium now.” I’m wide awake, watching the procedure unfold on a screen. I don’t feel a thing. My cardiologist has entered two veins in my groin, one for the tube that has the camera that captures the images he needs, the other for the catheter that delivers the closure device. There’s a hole, and I’m glad. If my cardiologist hadn’t found a hole, I’d have two tubes in my groin and a week’s recovery period ahead of me, all for nothing. Plus, we’d have no idea what caused my stroke or when it might happen again. But there’s a hole. Hallelujah! There’s a hole, and this man is going to close it.

12:45 pm: “I’m done,” my cardiologist says. “There was a hole. We closed it. You’re going to be fine.” Then, like a rock star, like Elvis leaving the building, he’s gone. I ask my nurse about the size of the hole. She shows me the device they used to close it, and it appears to be slightly larger than a nickel, slightly smaller than a quarter. I ask her about an image still left on the screen, a fluoroscopic image, I’ll learn later. “Is that my heart?” I ask her, and she says it is. She shows me where the occluder, the closure device, is located, this titanium ring of mesh, locked in place to keep blood shunting from right to left. My heart looks like a face in profile. The ridge of a forehead, the hook of a nose, the mouth and chin. There between the atria rests the occluder. Such a light thing, such a beautiful thing. “Can I have a copy of that image?” I ask. I clutch it to my chest as they wheel me to my recovery room.

4:00 pm: Because of the incisions in my femoral veins, I have to lie in bed, not moving or bending my right leg. By the time the nurses come to remove the tubes, I’m a little bored, so I try out a few jokes on them. I tell the snail joke. No response. So I try a really bad pun that kids usually enjoy. “Where does the General keep his armies? In his sleevies.” Nothing. “Boy,” I say, “you’re a tough crowd.” Then I decide to try something a bit more, shall we say physiological. “Do you know what a man has when his alligator dies? A reptile dysfunction.” Finally, laughter. Giggles, snorts, guffaws. That’s what I like to remember as we turn toward the end of this day. I have three more hours of lying on my back. Then they’ll release me and I’ll sleep in my own bed. I’ll start to heal. I’ll wake the next morning, a lucky man. I’ll greet the rest of my life. . . bada-bing. . . whole-heartedly.

December 3, 2012

Writing Family Stories

I’ve been thinking about family stories lately, in part because I’ll be on a panel at the Associated Writing Programs annual conference in March along with Rebecca McClanahan, Mary Blew, Suzanne Bern, and Sharon Carmack (“Turning in Their Graves: Researching, Imagining, and Shaping Our Ancestors’ Stories), but also because the most glorious thing happened last week; a distant cousin found me, a cousin I didn’t even know I had. She descended from the line of my great-great-grandfather’s brother. Ever since I did the research for my book, Turning Bones, I’ve been curious about my great-great-grandfather, John A. Martin, and the other family he must have had. In Turning Bones, after sorting through a passel of Martins named James and John, I speculate that John A.’s father must have been James Martin. Now, all these years later, a cousin I didn’t know I had arrives to tell me I was right. James Martin who married Nancy Fite, only one example of the number of times Martins would marry Fites over the generations.

When my great-great-grandmother, Elizabeth Gaunce Martin, died, John A. Martin married a young widow named Eliza French Phillips. He was 64 at the time; she was 28. John and Eliza had four children of their own, the last one being born in 1884 when John A. was 74. In Turning Bones, I imagine that there were family members who didn’t exactly approve of the marriage. My new cousin tells me such was the case. She tells me that some of John A.’s sons moved away from Lawrence County, Illinois, angry with their father because of the marriage. My great-grandfather, Henry Martin, stayed. He married and had two sons. The older one was my grandfather, George William Martin, named after one of Henry’s brothers who was one of John A.’s sons who moved to Hamilton County, Illinois, some eighty miles away from Lawrence County.

In 1917, that George W. Martin, wrote a letter to The Sumner Press, one of a series of letters they were collecting from former residents of Lawrence County. In his letter, George W. points out that he is 75 years-old and that he and his brother Jackson and their wives (both of them Fites) left Lawrence County in 1881. At this point in the letter, George W. gives into melancholy:

Jackson lost his wife in 1910. We live about 10 miles apart. My wife took down in the spring of 1913 with heart and kidney troubles. She was under doctors care about 30 months. On September 2, 1916, her spirit took flight to God who gave it. She was a good woman and the best to me there was in the world. I feel very sad and lonesome. No place feels like home to me. I have a family living with me. They are very good to me, still they don’t make it feel like home. I had rheumatism all last summer. Feel stiff and sore yet, still can’t get around very well.

“No place feels like home to me.” My heart breaks when I hear my ancestor say this. It makes me think about the stories that people carry toward the ends of their lives. How I long to unburden them. If I could write a different story for them I would, but, alas, the facts are the facts. When you unearth your ancestors’ stories, you’ll be awash in numbers: birth dates, death dates, census figures. Then, if you’re lucky, you’ll find someone—or they’ll find you—who remembers the tales passed down through the generations, those stories of incredible joy or heart-numbing sadness, those stories of family secrets and anger and want. You’ll end up with a story that the numbers can’t give you, the story of people and how the lives they have may not be the ones they always wanted. If you’re lucky, you’ll find the voice of an ancestor come to admit, “No place feels like home to me.” If you’re smart, you’ll preserve that voice, respect it, understand the hard-earned wisdom that it is. As much as you may want to hide it—as much as you’ll want to bless that ancestor with grace—you can’t without demeaning everything his life has been. He’ll be the one talking; when we write our families’ stories, we have to learn to listen.

November 26, 2012

Creative Cultural Criticism: A Writing Exercise

I’ve always enjoyed the mockumentaries of Christopher Guest and their critical and hilarious critiques of heavy-metal rock and roll, community theatre, dog shows, folk music, and the entertainment industry. Exaggeration can be a component of a good piece of creative cultural criticism as the writer casts a satirical eye toward the customs and details of a particular group or an aspect of our contemporary world. I always appreciate it when the writer suddenly and surprisingly becomes a part of the culture under consideration and is willing to be an object of his or her own criticism. Good creative cultural criticism highlights some aspect of our world and critiques it in a way that allows us to think more deeply about who we are. Here’s a writing activity whose purpose is to invite us to do just that.

1. Identify a particular cultural group (maybe it’s Ohio State football fans, or your neighborhood association, or art collectors, or jazz aficionados), or something that’s of interest to you about our contemporary culture (maybe it’s reality television, or Facebook, or Twitter, or online shopping. Maybe you’re a part of this particular group, or maybe you’re not. Maybe you appreciate a particular aspect of the culture, or maybe you oppose it.

2. Spend a few minutes characterizing the object of your criticism. What are the facts and the procedures? By what is this cultural group or phenomenon known? Buckeye football helmet mailboxes? Clove cigarettes? Fine wines? Wry status updates? A credit card at the ready? Tell us anything you can to characterize what you’ve come to critique.

3. What’s your history with this group or this phenomenon? Are you a member? A participant? Have you been in the past? Or are you truly an outsider? Answer these questions or others that occur to you by beginning with, “I am/am not what most people would call a _____.” Fill in the blank with the object of your criticism: Buckeye football fanatic, Facebook user, etc. Talk about what excites you about the group or the aspect of the culture, or talk about what you fear when you consider it. Give us a sense of who you are in relationship with the thing you’ve come to critique.

4. Give us a quick scene, or a mini-scene, about something that happened to you because of the object of your critique.

5. What are the general assumptions about the object of your criticism? Begin writing with the words, “Everyone assumes that. . . .” Then go on to consider the easy conclusions that we’ve reached about your group or your phenomenon. Then find a place to make room for an opposite truth that you’ve learned from your own experience as represented in the scene from step 4. You might say something like, “I’m starting to think, though, that. . . .” Your goal here is to see if you can find an opposite truth or another layer of truth that the general population has missed because of their hasty assumptions.

6. Write two more statements to be used as a focusing device for the piece of creative cultural criticism that this activity may lead you to write. Begin with, “It wasn’t_____(fill in the blank with the object of your criticism: Buckeye Football, Facebook, online shopping) that ____ (fill in this blank with a result to complete the cause and effect suggested by the first part of the sentence). Then write a statement that suggests a new cause. Begin with, “It was_____.” Here’s an example from Meaghan Daum’s essay, “On the Fringes of the Physical World,” in which she considers the effects of email and online chatting on romance: “It was not the Internet that contributed to our remote, fragmented lives. The problem was life itself.”

This exercise is an invitation to think more deeply about what some aspect of our culture can show us about ourselves. As always, we’re looking for the truths that most people won’t see. In creative cultural criticism, it’s often the leaps in thought that the writer makes that take us to this surprising place.

November 19, 2012

Happy Thanksgiving and PFO Closure

I’m thinking about Thanksgiving this week, and the way my mother’s side of the family always gathered at someone’s home for dinner in those long-ago times when I was a boy. For those of you unaware of the ways of rural southeastern Illinois, that was the meal we ate at noon. The evening meal was always supper.

The men ate first. Apparently, that was also the way of rural southeastern Illinois. The women were on hand to serve the food and keep tea glasses filled and to take dessert orders. I’m not really proud of that fact, but, alas, there it is. The kids ate at card tables in a nearby room. I was the oldest cousin, so I was the first to be invited to join the men’s table. There, my Uncle Richard insisted I sit beside him, and there he initiated me into the group by putting food on my plate when the serving dishes came round even if it was food I told him I didn’t want. My protests didn’t matter. He told me he was certain about what was best for me. At his side, I learned that sometimes it didn’t matter what I preferred; sometimes, I had no choice but to give myself over to someone else’s care.

Such is the case now with my cardiologist. Last week in his office, he told me that the second clinical trial testing a new device for PFO closure had shown the device to be more effective in preventing a second stroke versus treatment with medical therapy. But, he emphasized, the results of the trial hadn’t reached “statistical significance,” which, as I understand it, is the data the trial would have to produce to indicate that its findings reflected a pattern and not just a chance. Bottom line? No one really knows whether closing a hole between the atria of the heart does a better job of preventing a second stroke than managing the condition with anti-coagulants. Still, my cardiologist is confident that closure is the way to go.

“What would you do if it were your heart?” I asked my cardiologist.

He didn’t hesitate. “I’d close it,” he said. “In a minute. Wouldn’t even think about it.”

So on December 10, I’ll report to Riverside Methodist Hospital to have a a transesophageal echocardiogram done. This is the test that will confirm the presence of the suspected hole between my atria and also allow the cardiologist to access its size. If the hole is there and it turns out to be large enough to close, my cardiologist will do just that through a cardiac catheterization procedure. He’ll will thread a catheter through a femoral vein in my groin and deliver a septal occluder to my heart. The occluder is a small patch that looks something like an umbrella. It’s made of a polytetrafluorethylene material held inside a wire frame made of a nickel-titanium metal alloy called nitinol. Once the patch is in place tissue will begin to grow into the patch allowing the occluder to function as a permanent implant. My blood flow will return to its normal path, no longer able to shunt from my right atrium to my left, thereby significantly reducing my chances of having another stroke. I may be released from the hospital that evening or I may have to stay overnight. I won’t be able to run for a week, but I can walk right away, and after that week I should be back to full activity.

So, this Thanksgiving week, I give thanks for the love and support I’ve received from so many of you (keep it coming, please, as the days move on toward December 10), and I give thanks to the medical technology that has made such a procedure available for me, and I give thanks for my Uncle Richard who taught me all those years ago that sometimes your only choice is to keep quiet and surrender to the care of others. Happy Thanksgiving, everyone.

November 12, 2012

An Exercise in Nature Writing

We’ve had a beautiful weekend here in Columbus, Ohio. Plenty of sunshine and temperatures approaching 70. The trees are almost bare now; only a few are being stubborn and refusing to let their red leaves fall to the ground. It was the perfect sort of weekend for the writing assignment I gave my advanced undergraduate creative nonfiction writers last week. Find a place in the natural world, I told them. A park, the Franklin Park Conservatory, the Columbus zoo, an arboretum, Mirror Lake on campus, or a more secluded spot in the countryside. Just let yourself be there. Take note of all the sensory details. Pay attention to your response to your surroundings. What happens to you when you’re in that place? Bring your observations to class, and we’ll use them for a writing activity.

Today, it’s rainy with temps in the 40s. A perfect day for writing. A perfect day for recalling our beautiful weekend. So let’s get started.

1. Locate yourself in the natural world. Begin with a sentence something like this one from Elizabeth Dodd’s essay, “Setting Forth in their Footprints”: That night I sleep on blm [Bureau of Land Management] land just up the road, overlooking the Lyman Canyon, marked on the map as an intermittent stream a few hundred feet below the rim.

2. Once you’ve established your place in your particular slice of nature, sketch in the sensory details of the place. See if there’s one detail that especially makes an impression on you. Again, an example from Elizabeth Dodd’s essay: A high mesa to the east changes color as I sit watching, cooling in the evening; a tiny bit of snow clings to its upper reaches, but the rock flows various shades of vermillion, rufus, ocher, and I recognize for a moment the perfect shade of a stone I picked up days ago, grinding from it a few experimental grains as if to approximate paint. Then, briefly, the rock seems to shine from within, the way the dying heart of a campfire would have if I’d kindled one, just in the last moments before it would be time to scatter the coals, douse them with water, and listen to the hiss of ash-scented steam. Notice how precise Dodd is with her naming.

3. Let the details lead you to a statement that expresses a mood. Dodd says, Instead I listen to the current in the canyon below, an allegro of motion, of flow, the world in its exquisite movement into spring.

4. Now carry that mood inward as you make statements about what being in that place is like for you. Maybe you’ll begin with a statement something like, “For some time, I’ve been thinking about. . . .” Or maybe something like, “Being in this place makes me feel/wonder/ think/question. . . .”

5. Come back to one of the details of the place, perhaps a detail that you featured in the first step of this activity in the way that Dodd featured the mesa in the example from her essay. This time find something new in that detail. Maybe you begin, “I keep coming back to the sight, sound, smell of. . . .” Now that you’ve let the natural world take you to your own thoughts and emotions, what do you notice about your featured detail that you didn’t the first time you encountered it? How has your place in the natural world changed as a result of the journey it invited you to take inside your head and heart?

“Nature is full of genius, full of the divinity,” Thoreau said. I hope this writing exercise invites you to use your relationship with the natural world for the divine purpose of instruction as you take a closer look at what our interaction with natural spaces can tell us about ourselves.

November 5, 2012

Already Been Chewed: A Writing Exercise Using Facts

In light of all the controversy lately involving the manipulation of facts in creative nonfiction, I’ve come up with a writing exercise to force us to stay true to documented information and to use it for the exploration of material in which we have a personal stake, material we’ll come at slantwise, much in the same way that Dinty Moore does in his fine essay, “Son of Mr. Green Jeans,” which is subtitled, “A Meditation on Fathers.”

Dinty’s essay actually borrows from an ancient form of poetry, the abecedarian, in which the first line or stanza begins with the first letter of the alphabet and is followed by the successive letter until the final letter is reached. So Dinty’s essay begins with some facts about ALLEN, TIM, and ends with the section, ZAPPA, which draws in the central character of Hugh “Lumpy” Brannum, who played Mr. Green Jeans, on “Captain Kangeroo,” and forges connections with Dinty’s own thoughts on fatherhood, particularly his wish that his own father hadn’t embarrassed him with his drinking. Hugh Brannum would have been Dinty’s preference for a father, but Hugh Brannum, contrary to rumors, wasn’t Frank Zappa’s father, nor, of course, was he Dinty’s. The last line of the essay: “Too bad.” We get to this sentiment through a consideration of facts, some personal, some not.

So let’s start with some lists. For the time being, don’t worry about an alphabetical order, although if one starts to suggest itself, please feel free to go with it.

1. Who was one of your favorite childhood characters from TV, film, cartoons, comics, computer games, etc.? I challenged myself to start off with an “A” character, so I chose Atom Ant, that cartoon crime fighter from my childhood. “Up at at’em, Atom Ant!”

2. Choose a famous person that you so associate with something about the personality of your favorite childhood character. This famous person might end up being another character, as was the case with me when I chose Dennis the Menace.

3. Think of someone from your life, either present or past, who is contrary to the personality of your favorite childhood character. I chose my timid mother.

4. Come up with an animal that you associate with the personality of your favorite childhood character. I chose a type of ant called Crazy Ants.

5. Come up with an animal that you believe is contrary to the personality of your favorite childhood character. I chose the sloth.

6. Recall at least one personal experience that’s suggested by your consideration of the previous items on your list. I recalled the time my mother mustered her courage and confronted my high school principal over what she considered an injustice done to me.

7. Write your title: Son/Daughter of (Your Favorite Childhood Character): A Meditation on (leave this blank for now)

8. Begin with your favorite childhood character. Use a subject heading such as Atom Ant, or if you prefer, Ant, Atom. Write a few lines giving us some facts about that character. Feel free to do some research if you’d like.

9. Move on to each of the other items on your list, giving each a subject heading. Please note that the heading doesn’t have to be the name of the person or the animal you’re considering. Dinty has a section in his essay, for example, called Inheritance. Find more facts, whether from inside or outside your life. Go in whatever order your instinct tells you to go, knowing re-arrangement is always possible later.

10. Now that you’ve gathered your facts, go back to your title and fill in the subtitle A Meditation on. . .

It’s my hope that this exercise will open up some material for you and send you in search of other subject headings, other facts, as you continue to explore the center of your meditation via information. Even if you aren’t able to go “A” to “Z.” I hope the exercise will help you think about all that you can accomplish in a segmented essay if the segments are artfully juxtaposed and arranged.

October 29, 2012

Hole in the Heart, Hole in the Essay

The results for the second clinical study concerning PFO (patent foreman ovulae) closure are in. If you’ve been following my blog, you’ll recall that the doctors think I have a PFO, a hole between the atria of my heart that was supposed to close at birth but didn’t. The first clinical study that weighed the difference in effectiveness between closing the hole and managing it with anticoagulants showed no negligible difference. This second study, RESPECT, studied the effectiveness of a different closure device. The study shows that this device, the Amplatzer PFO Occluder, reduces stroke risk by 46.6 to 72/7 % over medical management alone.

These results may mean that I’ll be facing a PFO closure procedure sometime in the future, but for now I’m content to use what I’ve learned to help me think about an interesting question that came up in my MFA creative nonfiction workshop last week. We were talking about a segmented lyric essay, and I posed the question, “Considering the subject matter and the author’s treatment of it, is it fair to ask why the form is the only possible way for the writer to express what he’s come to say?”

It’s the old question of form fitting content. Take my heart for example. It’s meant to pump blood through my body. That blood isn’t supposed to shunt from my right atrium to the left through a PFO. That hole represents a defect in the form of the heart, and, therefore, the blood isn’t “expressed” the way it’s meant to be. If a clot moves from right to left, it can then travel up an artery to my brain, which is what the doctors think happened to cause my stroke.

Form and content. If the form is off in some way, the content isn’t properly expressed. Correct the content (close my PFO) and everything goes along all hunky-dory.

But, a student in my workshop said, why do we always hold lyric essays to that form and content standard. “We don’t ask that question of narrative essays,” my student said.

Point well taken. It seems to me that when the form calls attention to itself in some way by varying from the traditional, we immediately start to think about how the form is working in concert with the content. We’re less likely to ponder the same when reading a narrative essay because the form doesn’t call attention to itself. As lyric essays become more widely practiced and read, it may be that we’ll be less likely to consider that form and content question, but really it’s a good question, even for a narrative essay.

Thinking about all this after last week’s workshop, I came to the conclusion that the happy union between form and content in a narrative essay is announced through the narrative itself. The real-life story being told is one of such power, because of the tensions inherent in its storyline and because its telling takes us more deeply into the human heart, that it can only be expressed by being dramatized. I’m thinking of an essay like Barry Lopez’s “Murder,” in which a strange woman asks our author to murder her husband. Dramatic stuff, indeed. Lopez expresses the drama through a narrative that allows us to participate in the complicated and tense negotiations.

All of this is to say that the question of form fitting content is a fair question for both lyric and narrative essays. I find it important to always consider the best container to hold one’s subject matter and to fashion that container without holes so it can best perform its function, which is to communicate to the reader what can only be expressed in that form.

October 23, 2012

Lee Martin, Unplugged

It’s a glorious Indian Summer day here in Columbus, Ohio, and I’m giving thanks for the twenty minutes of running that I did this morning in the midst of my forty-minute walk. As many of you know, I’m a month into recovery from a stroke. To catch you up to speed in case you didn’t know that, I spent two days in the hospital and, fortunately, left with no impairments. An echo-cardiogram showed what may be a hole between the atria of my heart, a patent foreman ovale, the hole we all have in the womb which closes at birth—at least, it’s supposed to. For roughly twenty-five to thirty-three percent of the population, it doesn’t, and most of us are never aware of that fact, unless, as the doctors suspect is the case for me, a clot travels through that hole and into the brain.

My cardiologist wanted me to wear a heart monitor for twenty-one days to make sure I had no arrhythmia. I finished the test yesterday and will now wait to hear about the next step in this journey.

This morning was my first steps running without electrodes stuck to my chest, a sensor worn on a cord around my neck, and the heart monitor, which was the size of an older cell phone, in my pocket. For the first time in a little over three weeks, I was unplugged.

Before the stroke, I ran for an hour every other day. Now, I’m slowly working my way back toward that goal. In the long stretch of years when I was able to run without thought of my health, I sometimes forgot to give thanks for the sheer joy of each step. I grumbled over my balky joints, my sore feet, my tight calf muscles. I rushed to fit in a run so I could get to what lay ahead of me that day. I forgot the blessing of what running was to me.

So it is sometimes for the writer. I’ll admit I’ve wasted energy and time moaning over my own work when it’s not going well. Likewise, for the minutes I’ve spent envying other writers’ successes or feeling overly pleased with my own. The challenge of the work, the fact that someone’s acclaim eclipses our own, the smug pride we take in what we accomplish? They’re obstacles to the rich blessing that our work offers us. What a privilege it is to be able to face the page for however many minutes we can manage each day. Twenty minutes? Thirty minutes? An hour or more? Celebrate that time. Give thanks that you have the chance to do the thing you love. Do it for a lifetime. Treat it well, this gift, so it will return to you, knowing you embrace it with all your spirit and heart.

October 17, 2012

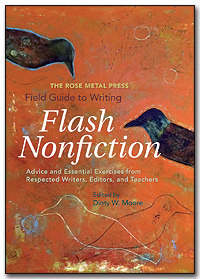

Communal and Personal Voices in Flash Nonfiction

This week’s post comes from my contribution to the Dinty Moore-edited, The Rose Metal Press Field Guide to Writing Flash Nonfiction. I don’t recall why, but at the time Dinty asked me for a contribution, I was pondering issues of voice, possibly because flash nonfiction is often voice-driven, or at least it is for me.

I remember one of my writing teachers, Gerald Shapiro, saying that he thought a good writer was usually a good mimic. I’ve always thought that a writer’s voice comes in part from the voices that surrounded him or her in childhood, a chorus of voices rising up from various communities: town, neighborhood, church, family, etc. , and in part from the individual speaking either in concert with those communal voices or in resistance to them.

Ancient Greek drama becomes an interesting way of thinking about how this works. In those plays, a chorus provided a cultural backdrop from which a single actor spoke. The voice of that actor was more personal, more lyric, giving the drama a more textured sound of an individual speaking from, and being considered by, a community.

Being aware of the communal and the personal voice when we write flash nonfiction can create a more textured sound. It can also lend a note of urgency, particularly if the juxtaposition of communal and individual creates a tension in the speaker. This tension pushes the piece along as the different voices rub together, providing the conflict of sensibilities crucial to the quick exploration of subject matter and character.

Here’s a writing activity that will help you practice this dance between the communal and the personal voices. Allow yourself no more than 750 words.

1. Recall a saying from one of your communities (e.g. family, church, school, scout troop, neighborhood, town) and write an opening line that contains that saying.

2. Keep writing using the language of the community to introduce a character. Here’s an example from the opening of my essay, “Dumber Than”: A box of rocks. That boy–oh you know the one.

3. Put that character in action. Again, an example from “Dumber Than”: Dropped his cat from that second-story sleeping porch just to see if it was true, what they said about cats always landing on their feet.

4. Find a place to step forward and to speak more personally. Extend the narrative or create a new scene: Once at Halloween, I caught him soaping the windshield of my ’72 Plymouth Duster.

5. As you turn toward the end of your essay, consider how the persona you’ve established for yourself is fitting into, or separating itself from, the persona of the group. Be aware of any tensions that exist between the different aspects of yourself and how what you’re writing invites you to do a quick exploration of your own character.

6. At the very end, find a way to blend your personal voice with the communal voice of the group: That’s when we got all righteous. Don’t act like it’s not true. Dumber than a bagful of hammers, we said. Now that’s one thing we always knew for sure.

October 10, 2012

Update From the Sick Ward

My family doctor tells me I’m doing great a little over three weeks after my stroke. She says I can go back to teaching. I confess that I already have. I taught my advanced undergraduate creative nonfiction workshop last night, I tell her, a three-hour class.

She wants to know whether it felt comfortable to me; I tell her I loved being back with my students. Then I come clean about what the work asks of me in the way of preparation and the other duties I have, and—oh, yeah—there’s still a glimmer of a writing career for me, a novel I want to get back to, essays I want to write. I tell her I’ve chosen to cancel readings, other teaching gigs. I tell her I’m learning to say no, at least for a while. She says she thinks it’s good for me to be back at work where I’ll have plenty of things to occupy my mind, so I won’t dwell on the stroke and the maybe-hole in my heart and whatever is waiting on down the road.

Then she gives me a gift: I can start running for five minutes during one of the three walks I take every day, and if that goes well, I can move up to ten minutes after four days, increasing things from there—gradually, of course.

“We’ll have you back to where you were,” she says.

I’ve been running since the early 80s; for the past few years, I’ve run an hour every other day. I’ve done weight training on the in-between days. No weight lifting yet, she says. My neurologist is worried about the increase in inner-cranial pressure that such an activity would cause.

I’ll take it, those five minutes, with the promise of more time to come. I’ll take it as a step toward what I hope will be a day when I’ll have no need to write about my stroke and the maybe-hole in my heart, when it’ll all seem like something that happened a long time ago in a world I somehow managed to fall into and then found a way to leave. A world of paralysis and helplessness, one I’ll hope to know again only by its absence.

*

One of yesterday’s joys was finding my contributor’s copies of The Rose Metal Press Field Guide to Writing Flash Nonfiction in the mail that had piled up at school. I took special note of a piece by Jennifer Sinor, “Crafting Voice.” I was intrigued with her thoughts on the ephemeral nature of voice. “We can’t point to it on the page,” she says, “pin it down, say that here, right here, in the way this sentence runs or in this choice of words or in this use of detail, we have voice.” She concludes that we identify voice by noting its absence, which leads to “the distance we feel from the writer, the subject, or from the words on the page.” Without voice, we feel at a remove, not fully engaged.

*

The absence of blood flow.

“Have you felt any tingling, any numbness?” my doctor asks me, and I tell her on occasion in my foot and my ankle.

She wants to know which foot

“Both,” I tell her, and she doesn’t express any alarm.

I let worry lift from me and wing away to the high shelves in the exam room, one of them displaying ancient remedies and medical instruments. I long for the day when I’m not on hyper-alert, on guard against any twinge and ache. I watch young men and women running through my neighborhood and I want to feel what I know they feel—that effortless glide through space and time. At night, I close my eyes and recall the routes I’ve run in countless cities. Five minutes, ten, fifteen, and on and on to the endorphin calm I crave.

*

“You don’t find your voice,” Jennifer Sinor says. “You make it.”

You make it out of an intimate knowledge of your subject matter, letting it inhabit you. Once you fully understand your material, not just factually but also in terms of the complications it presents, your confidence will translate into voice on the page.

For me, each draft I write is another way of living with my material and another step toward more fully knowing its complications and ironies. Drafts are discoveries, and I never know how many drafts I’ll need in order to know what I need to know.

*

Today, what I know is this: I’ve been lucky to be able to make my professional life the way I’d have it: a little writing, a little teaching. Without those two things, I wouldn’t have a voice. I wouldn’t be me.

*

Voice also comes, Jennifer Sinor points out, from a writer allowing herself to be vulnerable.

*

The first time I saw my family physician after the stroke, I wept. I wept from the memory of not being able to lift my right arm, my right leg. I wept because for a time, I hadn’t been able to say the words my brain held. I wept over the kind words, good deeds, and the windup toys my students and colleagues sent me. I wept over Nunzilla, and Chirpy Bird, and Robot Guy, and Knight on Horse. I wept because my doctor called me on the day of my release from the hospital, and the first thing she said was, “This is not going to happen again.” I wept because I didn’t want to weep. I wept for everything I’d gained and everything I’d lost.

Absence and presence.

I wept because, in spite of all this, there was still love.