Lee Martin's Blog, page 66

February 18, 2013

Post-MFA Advice

I’m thinking about all the MFA students these days who are making the turn into the homestretch. Only a couple of months to go until thesis defense time and then graduation. Exciting times, but also nail-biting, teeth-grinding, hair-pulling times. I remember my own anxiety about my post-MFA life, a life that included teaching five sections of composition each quarter at a technical college. Still, somehow I managed to work on my craft. Then I made a move to Memphis where I taught only four courses each semester, and I continued to work on my craft. While I was there, Stan Lindberg, then editor of The Georgia Review, came to be part of an editors’ symposium. I had the pleasure of picking him up at the airport, and we hit it off well. In the course of our conversation, he made the suggestion that I consider a Ph.D. program, and I decided he was right. That was really the beginning of all that’s come since.

So, if you’ll permit me, here are a few pieces of advice to those of you about to graduate:

1. Remember that graduation is often only the beginning and not the end.

2. No matter what work you have to do, or what it asks of you, don’t forget that you’re a writer. Work on your craft. Give it as much time as you can. Forgive yourself when you fall short of your goals.

3. Pay attention to the invitations that the world gives you. Often, a visitor comes with a piece of advice. See if that advice strikes something in you to the point that you know you’ve just heard the thing you need to hear.

4. Find ways to remain active in the literary community. Take community workshops, attend writers’ conferences, go to readings, ask questions of the guest writers, start your own writers’ groups, keep subscribing to literary journals, volunteer with community arts groups, look for non-traditional teaching opportunities through summer arts programs, continuing education classes, whatever it takes to stay connected to people who care passionately about the written word.

5. Accept that you’ll be envious of peers who succeed before you do. Keep practicing your craft. Try to remember that the world has a way of leveling these things out. One day, you’ll publish something or win an award, and you’ll want those same peers to be happy for you. Won’t you feel guilty if you had no good will for them in your heart when they stood where you do now?

6. Expect to succeed, but accept that many times you won’t. Keep in mind what Richard Ford said, “The thing about being a writer is that you never have to ask, ‘Am I doing something that’s worthwhile?’ Because even if you fail at it, you know that it’s worth doing.”

7. Your craft is a refuge. It is necessary. Out of all that will disappoint you, what you do between the margins matters most of all. It can save you. Treat it kindly. Although you may be tempted many times to forsake it, don’t. Love what you’ve chosen. It is the best expression of who you are.

February 11, 2013

Taking the Temperature of Writers’ Conferences

If you’re of a certain age, you’ll remember the old thermometers, the ones that you had to keep under your tongue for four minutes, the ones you had to shake down with an expert snap of the wrist, the ones that made you squint in order to make out the level of the mercury that told you your temperature. Believe it or not, I’m now the owner of a thermometer very much like this, only this one contains Galinstan, “a non-toxic, Earth friendly substitute for mercury.” You still have to hold it under your tongue for four minutes.

I was surprised to find out how impatient I was for those four minutes to pass, accustomed to the quick turnaround of a digital thermometer. I’d been lured into the world of instant gratification. Shame on me. If there’s one thing being a writer teaches me, it’s the art of patience. Results come in increments; sometimes, many more than four minutes pass between them. A career happens over a lifetime and not in a few seconds.

When I was just starting out, I decided to attend some writers’ conferences. It turned out to be a smart thing for me to do. Now, as I teach in a number of conferences each year, I try to keep in mind the person I was when I was a participant. I try to remember that I was nervous and just a little scared to have my work talked about by published writers and the other participants in the workshop. I try to remember that I often felt very far from home, a little bit like the boy on his first day of school. I was lucky, though. The writers’ conferences I attended gave me exactly what I needed:

1. A supportive group of folks who took my work seriously. In their company, I felt like a writer.

2. A smart group of folks who told the truth, but as delicately as they could.

3. An exposure to the literary life, and contact with agents and editors.

4. A network of friends, many of whom I’m still in touch with today.

5. Dedicated workshop leaders who were more interested in teaching than in playing the role of “famous author.”

6. The sense that with hard work and continued practice I could be better.

Maybe as I’ve taken the temperature of writers’ conferences (groan), I’ve given you something to think about. If you decide to attend one, stay open to learning, check your egos at the door, get to know people, give the sort of effort and respect to others that you want for yourself, leave with a sense of purpose and a direction to follow with your work. I’ll be teaching at conferences this summer in: Oxford, MS; Rowe, NH; Yellow Spring, OH; and Montpelier, VT. My one objective, as always, will be to enter a participant’s work with thanksgiving for its gift, with an understanding of what the work is trying to do, with plenty of praise for what’s working well, and with some suggestions for continued work. I hope I’m successful in returning each participant to his or her writing space with renewed vigor and a genuine excitement about the work that lies ahead.

February 4, 2013

Stylin’: Is It Dead or Alive?

Mavis Gallant, in her brief essay about style in writing, says, “The only question worth asking about a story—or a poem, or a piece of sculpture, or a new concert hall—is, “Is it dead or alive.”

A piece breathes life, in part, from the style in which the writer has chosen to bring it to the page. As Gallant goes on to point out, “If a work of the imagination needs to be coaxed into life, it is better scrapped and forgotten.” Style, she says, should never be separate from structure, by which I take it to mean that the manner of telling should always be in the service of what’s being told. Put another way, style is part of the form, and the form and the content and the meaning must be part of the same whole in order for the writer to say what he or she has come to the page to say.

Style has always seemed like an instinctual matter to me. A voice emanating from the world of the work, a world the writer knows so well, he or she can’t help but speak its language. It’s amazing how an intimate knowledge of that world can make all sorts of decisions for a writer. Know your worlds and everything falls into place, including the style of the writing.

Still, within any distinct style (yours might not be mine and vice versa), there are tricks of language to be learned that we can adapt to useful purpose in any style that we use in our own work.

With that in mind, I turn to these passages from Ann Beattie’s story, “In the White Night.” This is the story of Vernon and Carol, parents grieving the death of their daughter. The story opens with them leaving a party. Their host calls to them, “Don’t think about a cow.” This is a carry-over from a game they’ve been playing at the party. “Don’t think about an apple,” the host says, and, of course, Carol, our point of view character can’t get that image out of her head. This is a story about the adjustments we make in order to go on living in our grief. We try to put the images of our losses out of our minds, but, of course, we’re never fully successful.

My writing activity this week involves two passages from Beattie’s story and asks you to think about some of her strategies with language and then put them to use in sections from a piece of fiction, creative nonfiction, or poem that you’ve written, or are writing.

The first passage takes place as Vernon and Carol are driving home from the party:

They passed safely through the last intersection before their house. The car didn’t skid until they turned onto their street. Carol’s heart thumped hard, once, in the second when she felt the car becoming light, but they came out of the skid easily.

Here we have a passage that begins with two declarative sentences that states the safe passage of the car though the last intersection before home. Those sentences put a steady sound into our heads. Then we’re surprised with a new sound that comes from a variation in sentence structure in the third sentence, which contains the moment of the car’s slide and Carol’s response to it. The sentence thumps us the way “Carol’s heart thumped hard, once. . . .” Notice the choice of the verb, “thumped,” with its “th,” it’s “mp,” its “d.” This is a word that bangs its way onto the page. Notice, too, the caesura that Beattie creates with the word, “once,” set off with commas, that pause, while the car is skidding. Finally, notice how the subordinate clause, with its subject and verb echoing the declarative sentences that began the passage, returns us to steady ground once the danger has passed. The sentence structure in this passage expresses the emotional content of the action being described.

Writing Prompt #1

1. Find a passage in your draft that describes an action. Use sentence variety to express the emotional content of the moment.

The second passage comes just as Carol and Vernon are leaving the party and are making their way to their car.

I n the small, bright areas under the streetlights, there seemed for a second to be some logic to all the swirling snow. If time itself could only freeze, the snowflakes could become the lacy filigree of a valentine.

The first part of the sentence, “In the small, bright areas under the streetlights. . .” Beattie strings two adjectives together in spite of all the advice we hear about paring out our adjectives and adverbs. Those two stresses slow the sentence down and serve to emphasize the bright areas being presented to the readers. The pace of the sentence forces us to look at what’s being described. In the midst of the swirling snow, Beattie allows the language to be a little loose, to be expressive of what she’s describing. Notice how the sentence opens with a subordinate clause and the rest that comes at its end. It’s into this pause that the snow comes. Notice, too, the assonance and consonance, the repetition of the “f” sound in “freeze,” “snowflakes,” and “filigree”; the rhyming action of “snowflakes” and “lacy” and of “freeze” and “filigree.” Finally, notice how Beattie makes a metaphor from the detail of the snowflakes, saying that, “If time could only freeze, the snowflakes could become the lacy filigree of a valentine.” In a story about a couple trying to live in the aftermath of their daughter’s tragic death from leukemia, this metaphor is not only descriptive but also expressive of the sort of regret that couple experiences while at the same time making the adjustments necessary to their comfort.

Writing Prompt #2

Find a passage in your fiction, nonfiction, or poem that you think could better express what you’ve come to the page to explore. Write one sentence that uses successive stresses, or any other means, to slow the pace and call attention to a detail or a description. Then write another sentence, in which you construct a metaphor from a detail, a metaphor that becomes a container for the emotional center of the story.

Prose writers, don’t think that language is only the domain of the poets. Pay attention to sentence variety, word choice, prose rhythm, the sounds of words, metaphor, pacing, and the next thing you know, you’ll be stylin’!

January 28, 2013

My Mother Gives Me a Writing Lesson

As I dream of spring on this cold January day, I’m reading through some old letters from my mother, written in her widowhood, and I’m struck by the sound of my own voice in hers and the lesson she offers the writer I’ll one day be about how to let the details evoke a life:

As I dream of spring on this cold January day, I’m reading through some old letters from my mother, written in her widowhood, and I’m struck by the sound of my own voice in hers and the lesson she offers the writer I’ll one day be about how to let the details evoke a life:

The little garden I have planted just stands there. No potatoes ever came up. I don’t know if it will grow when it warms up or not. If it does we might have some spinach or lettuce when you come home. But I can’t promise any. I’ve been using onions from those I set out last fall. I want to get some cabbage and cauliflower as soon as the stores get their plants.

Flannery O’Connor, in Mysteries and Manners, talks about how the meaning of a story has to be made concrete through the details. “Detail has to be controlled by some overall purpose,” she says, “and every detail has to work for you.” She goes on to suggest that these details be gathered from “the texture of the existence” that forms the world of the story. “You can’t cut characters off from their society and say much about them as individuals,” she says. “You can’t say anything meaningful about the mystery of a personality unless you put that personality in a believable and significant social context.”

My mother wrote this letter to me while I was in the MFA program at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville. A ten-hour drive separated me from her home, a home I’d had to leave her in alone because two weeks before the move to Fayetteville my father died. My mother was seventy-two at the time and she hadn’t had a driver’s license for some time. To leave her was, at that time of my life, the hardest thing I’d ever done. Now, as I read this passage from her letter, I find the essence of her life in those days rising from the details that she includes: the garden where the potatoes have refused to come up, the hope for spinach or lettuce when I return, the acknowledgment that she shouldn’t hope for too much, but still the dream of cabbage and cauliflower plants to come. Each detail expressing some aspect of what it was to be her at that time in her life, each detail holding the person she was in that place. If I encountered this passage in a story, I’d say I loved the writer’s trust in the details, and I loved how they so simply and yet elegantly created the meaning of this character’s life.

We fiction writers have to pay attention to the worlds of our characters and to the way the objects of those worlds become expressive. So with that in mind, here’s a writing exercise:

1. Gather the details of the setting of a story that you’re working on or one that you’ve completed to which you want to add more cultural texture. Pay attention to sensory details, not limiting yourself to the visual. What are the sounds of this place? The smells? The textures? The tastes? What are the customs?

2. Zero in on the details that are intimately connected to your main character. What do they show you about him or her that you didn’t know? What do they confirm about your character that you already thought you knew? Are the details, for example, expressive of certain cultural attitudes? Is your main character acting in accordance with the cultural influences of the setting, or is he or she acting in resistance to those attitudes?

3. Have your main character engage in an activity that is common in this culture—playing music for tips in the subway, for example, or planting flowers in the garden, attending the symphony or bingo night at the American Legion. Or have your character do something that would be considered out of place in this culture. The key is to have your character act from his or her relationship with the culture in which he or she lives.

4. Find a place within the scene to rely solely on details, ala the passage from my mother’s lesson, to express something essential, but something impossible to say directly, about your character’s life.

Our characters come from specific worlds. Whether by birthright or adoption, fiction writers cozy up to particular landscapes and use them to give their writing authority, contribute to characterization, suggest plots, and influence tone and atmosphere. The details of a place can create the characters and their actions.

January 21, 2013

I Was Wearing Them the Day: Touchstone Moments for the Fiction Writer

I’ve always been interested in the question of where the fiction writer finds material. I’m particularly interested in how the autobiographical gets transformed into fiction. My curiosity comes not from wanting to know about the personal lives of writers, but more from a desire to provide my students a way to increase the urgency and intensity in their stories, to write about people and events and objects that matter deeply to the writers themselves, even if those characters and their actions and the things they possess are pure inventions. I believe writers create more memorable works when they either consciously or unconsciously make space for their own lives within their fictions. That’s why I often begin a fiction workshop with a nonfiction writing activity, one that invites the writers to recall specific moments from their pasts that were full of emotional complexity. Moments of simultaneous love and hate, fear and courage, pride and shame, or any other binary of opposites. I call these touchstone moments, ones that we fiction writers can tap into on an unconscious level during the writing of a story or novel, and by so doing, create a more resonant work.

I’m also interested in the use we fiction writers make of the objects that populate our invented worlds. Flannery O’Connor, in Mysteries and Manners, says, “In good fiction, certain of the details will accumulate meaning from the action of the story itself, and when this happens they become symbolic in the way they work.” She cites her own story, “Good Country People,” as an example. The story of a spiritually and physically maimed young woman who wears a wooden leg that ends up being stolen by a traveling Bible salesman. As O’Connor points out, writing about this story in Mysteries and Manners, the theft reveals the young woman’s deeper affliction to her, the affliction that comes from the absence of faith. The Bible salesman says to her as he’s about to leave, “. . .you ain’t so smart. I been believing in nothing ever since I was born!” The detail of the wooden leg, then, works within the plot of the story while at the same time expanding it thematically. If we fill our fictional worlds with concrete details and then make them a significant part of the action, we not only hasten the plot along, we also complicate the thematic concerns of a narrative in a rich and interesting way.

Let’s try a writing exercise that’s meant to invite you to access one of those touchstone moments from the past so it’ll be there at your disposal anytime you want to tap into its emotional complexity in your fiction. This exercise should also allow you to think about the way concrete objects acquire meaning through action.

1. Make a list of shoes that you remember wearing as a child. Go as far back in memory as you can.

2. Which pair of shoes on your list resonates most strongly for you, probably because they’re connected in some way to an emotionally complex moment from your childhood.

3. Using those shoes as your object, begin a freewrite with the words, “I was wearing them the day. . .” Narrate a moment from your past in which you felt contradictory emotions.

That’s all there is to it. Tell a story from your past and feel the layers of emotion that you felt then, that you still feel when you recall it. Let that complicated moment fill you. Know that it’s always there to help you create more resonant moments in your fiction, not necessarily replications of your experiences but containers for the complicated come and go of our lives at the ready for your use with created characters and events.

January 14, 2013

Preparing the Final Scene by Delaying Conflict

We start today with a passage from Richard Bausch’s story, “The Fireman’s Wife.” I’ve written about this story before on this blog, so I’ll only say that the story is about Jane who is close to leaving her marriage to Martin. At the end of the story, Martin has been injured while fighting a fire and has come home to find Jane’s bag packed. Because of his injury, she doesn’t leave that night. She gets him settled in bed, and the next morning, she listens to his attempts to talk about why she shouldn’t leave him. Then she walks outside. At this point, Bausch does some interesting things with landscape and the past:

Later, while he sleeps on the sofa, she wanders outside and walks down to the end of the driveway. The day is sunny and cool, with little cottony clouds—the kind of clear day that comes after a storm. She looks up and down the street. Nothing is moving. A few houses away someone has put up a flag, and it flutters in a stray breeze. This is the way it was, she remembers, when she first lived here—when she first stood on this sidewalk and marveled at how flat the land was, how far it stretched in all directions. Now she turns and makes her way back to the house, and then she finds herself in the garage. It’s almost as if she’s saying goodbye to everything, and, as this thought occurs to her, she feels a little stir of sadness. Here, on the work table, side by side under the light from the one window, are Martin’s model airplanes. He won’t be able to work on them again for weeks. The light reveals the miniature details, the crevices and curves on which he lavished such care, gluing and sanding and painting. The little engines are lying on a paper towel at one end of the table. They smell just like real engines, and they’re shining with lubrication. She picks one of them up and turns it in the light, trying to understand what he might see in it that could require such time and attention. She wants to understand him. She remembers that when they dated, he liked to tell her about flying those planes, and his eyes would widen with excitement. She remembers that she liked him best when he was glad that way. She puts the little engine down, thinking how people change. She knows she’s going to leave him, but just for this moment, standing among these things, she feels almost at peace about it. She has, after all, no need to hurry. And as she steps out on the lawn, she realizes she can take the time to think clearly about when and where; she can even change her mind. But she doesn’t think she will.

“The Fireman’s Wife” is a story that exhibits an extraordinary measure of restraint at the moment of climax. Rather than rushing ahead toward resolution, Bausch slows down and delivers a more nuanced portrait of a marriage in trouble. The drama happens at the level of character more so than the completion of action, and that’s because of Bausch’s sensitive and extraordinary management of Jane’s point of view.

So with a similar objective in mind, I offer the following exercise. This might work best with a story that you’ve already drafted or are in the process of drafting, but it could also be useful for a story that you’re thinking about writing.

1. Imagine a climactic moment for two of your characters, one that will bring them to a tipping point, or, in other words, a place where your point of view character might take an action that will change everything forever.

2. Have your point of view character walk away from the conflict.

3. Use the landscape and a detail that’s specific to the other character to activate the point of view character’s memory and to spark a divide within him or her as he or she straddles the past life and the one that lies ahead.

The objective of the exercise is to see what you can find within your point of view character before he or she enters the final scene of the story. By creating a moment of pause, the final resolution makes a louder noise; even if it’s fairly quiet in terms of action, it’s very resonant in terms of what rises up in the main character. In the case of “The Fireman’s Wife,” Jane experiences a surprise that she never could have predicted. She returns to the house and checks on Martin, who is sleeping. Bausch then give us this powerful last paragraph:

At last he’s asleep. When she’s certain of this, she lifts herself from the bed and carefully, quietly withdraws. As she closes the door, something in the flow of her own mind appalls her, and she stops, stands in the dim hallway, frozen in a kind of wonder; she had been thinking in an abstract way, almost idly, as though it had nothing to do with her, about how people will go to such lengths leaving a room—wishing not to disturb, not to awaken, a loved one.

A simple action can lead to a resonant end if your point of view character is alert enough to the world around him or her—if the action draws out a crucial response, one the reader won’t be able to forget.

January 7, 2013

Writing about Writing a Story

We’re starting Spring Semester classes at Ohio State, and I’ll be teaching the MFA fiction workshop as well as an advanced undergraduate fiction workshop. A semester for lying!

I’m beginning, as I often do, with Tobias Wolff’s story, “An Episode in the Life of Professor Brooke,” from Wolff’s first collection, In the Garden of the North American Martyrs. In the first two paragraphs of that story, Wolff efficiently and quickly gets a dynamic character on the page. A character of contradictions. A character made up of the story he tells himself, the one in which he’s a decent man, and the story that runs along beneath it just waiting for the pressures of the plot to bring it to the surface, a story of human failing that Brooke never could have predicted would eventually be his.

The action of the story involves a colleague of Brooke’s, Riley, the judgments that Brooke passes on his character, a woman named Ruth, and the actions that Brooke takes that create long-lasting consequences. The New York Times review of Wolff’s collection, published in 1981, devotes a good deal of space to this particular story. Of the opening, it says,

Within a few sentences you’ve developed a fix on both characters [Brooke and Riley] and start to anticipate the process of having all your presumptions confirmed by a steady accumulation of incriminating details—which, after all, is usually one of the more considerable satisfactions of tightly controlled fiction and closely observed life. But then Wolff begins to undermine our complacency of response. Because part of what he is up to in this unsettling collection is demonstrating how slippery the matter of passing judgment, moral or esthetic, can be.

This undermining of what we come to expect of the characters from our first meeting them in the opening interests me tremendously. It seems crucial to worrying the submerged story up to the top of the narrative. To put it in simple terms, we meet our main characters in the opening, and we think we know exactly where the story is headed only to reach the end standing on completely different ground. The story seems to move in one direction when all long it’s moving in the opposite direction.

Which leads me to a question I’ll ask my workshop to help me consider because I don’t know the answer. Can writing about writing a story before you actually begin to put it on the page help to create this undermining effect or can it only happen spontaneously during the process of creating the story? Furthermore, is the answer possibly different depending on the individual writer?

But if you’ll indulge me, let’s try an exercise:

1. Write a name at the top of your computer screen or on a sheet of paper. Any name will do. Just create one right now without too much thought.

2. Answer a few questions about this character. Don’t think too much about your responses. Go with your first instincts. What does this person do for a living? What is his/her marital status? Does he/she go to church? If so, which church? What’s the one article of clothing that he/she can’t part with even though he/she can’t wear it anymore? How would he/she describe himself/herself? “I’m a person who. . . .”

3. Write down another character’s name and answer a few more questions. Where does this person like to go when he/she wants to be alone? What physical feature is he/she most vain about? When was the last time this person cried and why?

4. Now let’s create a third character, one that might seem a bit incongruous when placed with the first two characters. What is this person most passionate about? What’s something that he/she tries to keep other people from knowing? Which of the other two characters does he/she most admire and why? What object does he/she possess that is emblematic of a difficult time in his/her life?

5. I often ask people to now craft an opening in imitation of the first two paragraphs of the Wolff story. Decide which of your first two characters will be your point of view character. Then set him or her in a relationship with your second character. Invite your point of view character to be very sure in his/her assessment of the second character.

6. What have you led your readers to expect about your main character from the opening that you’ve written?

7. Decide upon a narrative that will make it impossible for these two characters to escape each other. Where are they? What do they have to do? What single action on the part of your main character will change the way he/she views himself/herself and the world around him/her? How will your third character be crucial to that change?

8. What story do you think you’re telling from the beginning? Complete this sentence, “This is a story about. . . .” How can you construct the narrative to tell an opposite story? Can you sketch out a series of causally connected actions on the part of your main character that will allow this opposite story to emerge? Can you complete this sentence? “I thought this was a story about. . ., but actually it’s a story about. . . .” Now hide the second half of that sentence and start writing your story, trusting that what you’ve hidden will work its way up through the actions of your main character.

This exercise is designed to help us test the possibility that thinking aloud on the page before we begin writing a story might lead to a more resonant end that takes us to a moment of inevitable surprise. But as I said, I have no idea whether this will prove to be helpful or prohibitive. I invite you to help me think about its effectiveness or lack thereof.

December 31, 2012

Happy New Year

I’m thinking today of some of the New Year’s customs from my native southeastern Illinois where many of the people came from Kentucky and Tennessee. True to the southern tradition, cabbage and black-eyed peas were popular foods on New Year’s Day. The cabbage represented green folding money and the peas represented coins. Eating them meant having economic prosperity throughout the year. I’ve also heard of folks sleeping with a horseshoe under their pillows on New Year’s Eve to bring good luck. I’ve tried the cabbage and the peas, and while I’ve never slept with a horseshoe under my pillow, I do keep one on a shelf in my study, a large horseshoe rescued from my family farm before I sold it, a shoe that must have come from the days when my grandfather plowed with a team of draft horses. I keep it turned up so the luck doesn’t fall out.

My parents weren’t big New Year’s Eve revelers, but they did usually host or attend an oyster soup supper for, or with, my aunts and uncles. The supper was generally followed by an evening of playing cards: pitch, euchre, or Rook. As far as I’ve been able to discover, the custom of eating oysters as a way of bringing good fortune comes from the Chinese. I’m fairly certain that my parents never set foot inside a Chinese restaurant, so if anyone knows more about this custom as it applies to those outside the Chinese culture, I’d be interested to hear from you. I’m particularly interested in how that custom of oysters on New Year’s Eve made its way to the farms and small towns of southeastern Illinois.

Sometimes we need something solid to hold onto to give us faith in the future rolling out ahead of us. I make this post on New Year’s Eve, 2012, as a fine snow comes down on Columbus, Ohio, and as I wait to see why I’ve developed an irregular heartbeat three weeks after my PFO closure. I returned my 24-hour heart monitor this morning, and we’ll see what it shows my cardiologist. He’s told me that he’s confident that the device he implanted in my heart isn’t causing my arrhythmia. Maybe he’s right. Who knows? One more wrinkle to deal with here at the end of what’s been for me a challenging past three months. But it’s also been a year of good friends, good students, good books, good time spent with good people, and, when I was lucky and the muse was with me, good writing. I’m grateful to have had the chance to experience it all.

I wish you all a prosperous New Year, no matter what your lucky foods may be or what customs you may follow. I look forward to our paths crossing in 2013. Until then, love and blessings, and much, much, much good luck.

December 24, 2012

Slide Rules and Typewriters: A Memoir of Christmas Presents Past

Career Counseling

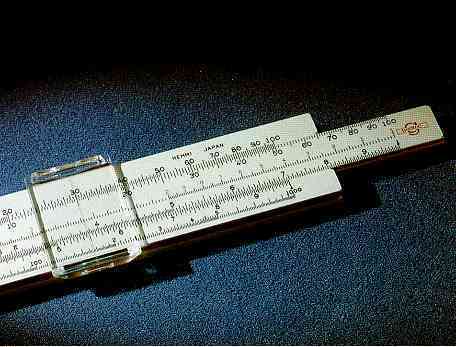

My cousin taught high school math. At Christmas, he gave me complicated puzzles. One year he gave me a slide rule. I kept it a long time. It seemed like something I should be able to make work. It looked inviting with its ruler-like lines and numbers and the cool middle slide that I could move back and forth. My cousin said it could multiply and divide and find square roots and algorithms, whatever they were. Every once in a while, I’d take it out and try to perform some simple calculation—two times two, for instance—but I could never get anything to compute. I’m sure some other boy, more mathematically inclined, could have had more luck, but he’d never have the chance. I held onto that slide rule just to spite the boy my cousin must have thought I was when he gave it to me.

My cousin taught high school math. At Christmas, he gave me complicated puzzles. One year he gave me a slide rule. I kept it a long time. It seemed like something I should be able to make work. It looked inviting with its ruler-like lines and numbers and the cool middle slide that I could move back and forth. My cousin said it could multiply and divide and find square roots and algorithms, whatever they were. Every once in a while, I’d take it out and try to perform some simple calculation—two times two, for instance—but I could never get anything to compute. I’m sure some other boy, more mathematically inclined, could have had more luck, but he’d never have the chance. I held onto that slide rule just to spite the boy my cousin must have thought I was when he gave it to me.

Career Counseling (Take 2)

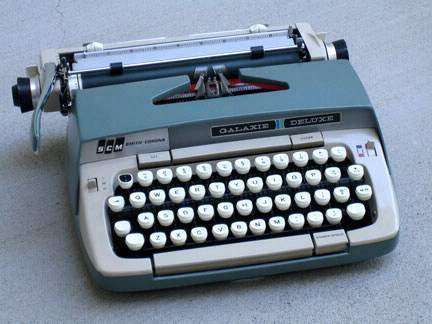

I took my first typing class when I was a sophomore in high school. I needed to learn to type,  my teacher told me if I intended to go to college. My parents told me that was what I indeed intended, so I set about learning to touch type, relying on muscle memory to locate the keys without looking at them. To help me practice at home, my parents bought me a portable typewriter—a Smith-Corona Galaxie Deluxe. It came in a hard plastic carrying case, gray, and it had a ribbon that was black on the top half and red on the bottom half. I could push a lever on the upper right side of the keyboard to change the color. The keyboard was cream-white, its metal casing sky blue. I loved the feel of my fingers pressing down on the keys, the clacking noise they made, and the bell that rang to tell me it was time to return the carriage. I’d seen Dick Van Dyke, as Rob Petrie, use a typewriter to write television scripts on The Allen Brady Show, and I thought the life he had seemed like a fine life—high jinks with his writing partners, Buddy and Sally; the glamor of the entertainment business; a fine wife and son in a fine home in the suburbs. I lived in a town of a thousand people in southeastern Illinois. Our house was a modest frame house with clapboard siding. I was an only child and through books I’d discovered the pleasure of a life lived inside the imagination. I had no idea what I wanted to do with that life, but I somehow sensed that typing was the way to find out. So I practiced. I typed the exercise my teacher taught me. I typed it again and again, ink pressed to paper:

my teacher told me if I intended to go to college. My parents told me that was what I indeed intended, so I set about learning to touch type, relying on muscle memory to locate the keys without looking at them. To help me practice at home, my parents bought me a portable typewriter—a Smith-Corona Galaxie Deluxe. It came in a hard plastic carrying case, gray, and it had a ribbon that was black on the top half and red on the bottom half. I could push a lever on the upper right side of the keyboard to change the color. The keyboard was cream-white, its metal casing sky blue. I loved the feel of my fingers pressing down on the keys, the clacking noise they made, and the bell that rang to tell me it was time to return the carriage. I’d seen Dick Van Dyke, as Rob Petrie, use a typewriter to write television scripts on The Allen Brady Show, and I thought the life he had seemed like a fine life—high jinks with his writing partners, Buddy and Sally; the glamor of the entertainment business; a fine wife and son in a fine home in the suburbs. I lived in a town of a thousand people in southeastern Illinois. Our house was a modest frame house with clapboard siding. I was an only child and through books I’d discovered the pleasure of a life lived inside the imagination. I had no idea what I wanted to do with that life, but I somehow sensed that typing was the way to find out. So I practiced. I typed the exercise my teacher taught me. I typed it again and again, ink pressed to paper:

Now is the time. . . .

Now is the time. . . .

Now is the time. . . .

December 17, 2012

Beauty Is Still With Us

Jake Adam York

I heard the news early yesterday afternoon that the poet, Jake Adam York, had suffered a stroke at the age of forty. Because of my own recent stroke, I have statistics at the ready. Of all the people under the age of fifty-five who suffer a stroke of unknown causes and who have no risk factors, forty percent have, as I did, a patent foramen ovale, a hole between the atria of the heart that allows blood to shunt from the right atrium to the left where a clot can travel to the brain. That hole can be closed, as mine was a week ago today in a successful procedure. My recovery has gone well. Tomorrow, I’ll be able to run again and to resume full activity. For these reasons, I felt confident that the news about Jake Adam York would be better in time, but, alas, our own stories are not always the stories of others. I was stunned to find out that by nightfall this incredibly gifted poet had left us all to soon.

Sometimes, as Wordsworth wrote, “the world is too much with us.” The world in all its ugliness: the school shootings in Newtown, CT, all those young lives taken before they could see how far they could reach; a poet leaving us to feel the empty space of all the poems he’ll have no chance to write; a million other individual tragedies every day that escape our knowing, and yet, of course, we sense their existence—how could we not?—through the thin veil that separates us from the arbitrary collision of circumstances that make up our living and our passing.

This sense of impending loss makes what we do in our lives all the more necessary; it makes what we create all the more beautiful. A story, an essay, a novel, a poem. A painting, a piece of music, a perfectly cooked meal, a performance. A kindness, a favor, a decency, a prayer. Whatever we have within us to announce our connection to one another. It’s important to remember at these times of loss that beauty is still with us, and we are here for one another.

So I’ll close with this poem from Jake Adam York, and his reminder that “what’s hidden’s never hid.” Until next time, blessings. . . .

DOUBLE EXPOSURE

Not even a father yet

my grandfather leans against

the grille of his ‘46 Packard,

new chrome blinding

even in black-and-white.

His white slacks billow

like a skirt in the wind.

His hair is perfectly still.

The war is behind him.

The road winds up from the farm.

One cornhusk hand

slips from the fender

and into the fingers

that ghost his fingers,

the thin, delicate lace

that haunts his hems.

The more I look, the more

he looks like someone else,

ringlets massing in his hair,

the gaze gone strangely tender,

the smile now doubly bright—

bright as the rings on his finger

casting what they cannot hold,

as if ready to part, to say

what’s hidden’s never hid

but beating like a second heart,

a second pulse in the pulse

that runs through everything.