Lee Martin's Blog, page 65

April 29, 2013

Teaching at Writers’ Conferences

At the end of this week, I’ll be in Oxford, Mississippi, teaching a memoir workshop preceding the Oxford Creative Nonfiction Conference and then sticking around to be on a panel during the conference proper. Thus begins the season of writers’ conference teaching with other visits to Rowe, Massachusetts; Yellow Springs, Ohio; and Montpelier, Vermont, to come. I love teaching at these conferences where folks are generally passionate about their craft and eager to pick up some little tidbit to help them along their writers’ journeys. I also love meeting folks I otherwise wouldn’t have had the chance to know, and getting to have some small part in the work that they’re doing. If I can share what I know in a way that will be helpful, maybe I can save someone a bit of time in the development of his or her craft. By so doing, I can pay back all the wonderful teachers who did the same for me. Like the handyman character, Red Green, used to say on his television show, “Remember, I’m pulling for you. We’re all in this together.”

I was first drawn to creative nonfiction by memoir. I was a fiction writer who decided to turn his skills with narrative into storytelling about the self. I quickly learned that I loved being able to dramatize moments from my life and arrange them in a narrative thread of cause and effect. I also loved being able to reflect upon those moments, interrogate them, use them to think more deeply about the person I was/am and the people around me. This is all to say that I’m very much looking forward to my trip to Oxford, and the conversation I’ll have about memoir with the folks in my workshop.

Here’s what I hope to give people when I teach at a writers’ conference:

1. A clear sense of what they’re attempting in the project that they have underway. An idea of what first brought them to the page. I like to invite people to get in touch with what they don’t know when they begin to write. What are they trying to sort through, figure out? What single question might provide a guide through their material and also a way of judging what belongs and what doesn’t?

2. A good idea of the narrative arc. What constitutes the beginning, middle, and end? Also a sense of how the writer’s emotional/intellectual arc responds to the pressures of the narrative arc. I was reading an article by Benjamin Percy in the May/June 2013 issue of Poets & Writers, called “Writing With Urgency.” He talks about Freytag’s Pyramid, that diagram that indicates the rising action of a narrative. Then he says, “But you must also imagine the emotional arc of your character inlaid in this pyramid. To create suspense, a story must have both: what is outside of the character (whatever is intruding on the character’s life) and inside of the character (whatever is desired that is just out of reach). When these two things come together, you build the potential for something to happen.” I’d like the people in my workshops to reach a better understanding of how the narrative arc and the emotional arc are inseparable.

3. A sense of what they’re good at. I’ll usually read a few passages that demonstrate the writers’ strengths so they can hear where their work is what I’d call “white-hot.” In other words, those places where I’m most engaged as a reader. I like to use those passages to invite folks to think about the artistic choices that the writer has made in order to create memorable effects.

4. Some questions about the material that the writers can use to produce more writing in an attempt to find some answers. In our first drafts, there are usually moments that need to be opened up. Sometimes our drafts suggest the questions, but sometimes readers can provide them by telling you what they’d love to know more about.

5. A confidence in the shape of the project and the things to be investigated. A center for the piece and a feeling that the writer is in control.

Ultimately, I hope folks leave my workshops knowing that their talents have been appreciated. I also hope they’ll have a clear plan for further work with their projects as well as craft issues to consider in future work. If we can accomplish that in Oxford, we’ll know we’ve had a good day’s work.

April 22, 2013

To My Students

Sunday morning, and I’m thinking of my students who are about to graduate, and another Sunday when I was fifteen, and my mother was working in the laundry at a nursing home in Sumner, Illinois, where the population was around 1,000 at the time. She had to be at work at 5am, which meant I didn’t have to go to church because my father wasn’t interested, which meant I was pretty much free to do whatever I wanted, which meant I was walking the streets just to be out of the house.

That’s when I saw the man in the back of a pickup truck parked along the side of the street just past Perrott’s Grocery. I didn’t know if he was asleep, passed out, or dead. He was face-down on the bed of that truck, a checked shirt pulled out of his jeans, a cuff with snap buttons undone around his wrist, a pair of pointy-toed brown cowboy boots on his feet.

This was a time when I was close to losing myself, just another teenage boy rebelling against authority, going from an “A” student to one who was barely getting by in a number of classes, taking risks with shoplifting and drinking. Small potatoes compared to some, but still I was no one my parents would recognize. I’m certain I didn’t know who I was or what I was on my way to becoming.

Then I saw that man. I stopped awhile and took him in, this man who’d obviously spent a portion of his Saturday night on that truck bed in this drowsy town where the bells at the Christian Church were now ringing and where my mother, a gentle woman who loved me, was putting her hands into detergent so strong it left her with a wicked rash. My mother who’d taught grade school for thirty-eight years and was now sixty-two years old. My mother working the five-to-two shift and missing the church service she loved, while I walked uptown, went into Piper’s Sundries and stole a paperback biography of Janis Joplin, smoked a couple of Camel cigarettes, did everything I could to forget about that man in the truck, but he was always there. He still is. I can’t get him out of my head

I wanted to be someone my mother would be proud to call her son. She took me to church that evening. She did her best to save me, and I wanted her to. It would take a few more years. It would take my mother’s unshakeable faith.

She was a teacher all her life, even after she retired. She knew how to see the best in people. She knew how to wait until they saw it in themselves. I saw that man in the truck on a Sunday morning, and I wanted to be better. It took a lot of Sundays for that to happen, but eventually it did, and, when it did, my mother didn’t act surprised. She’d been convinced all along that one day I’d pass through the darkness into the light. I’d find my talents and I’d love them too much to toss them away.

So, to my students, I say, love your talents, love yourselves, love the journeys you’re on, love the people around you. You’re going places, marvelous places you might not dare imagine. Trust me. I’ve seen the best of you. I know.

April 15, 2013

Mowing at Dusk

Maybe this is nostalgia, or maybe it has something to say about the work a writer does. I’ll leave that up to you.

I was a boy who didn’t understand the things my father loved. I had my sights set in a different direction. Each spring, before I graduated from the eighth grade, and my parents made the decision to move back to our downstate farm from Oak Forest, IL, where we’d been living the past six years, we’d often make the five-hour drive south after school was done on a Friday, so we could spend that night, and the next day, and Sunday morning on those eighty acres my parents still thought of as home.

On warm evenings, we’d drive with the windows down, and as we made our way into the country, I’d smell the clay soil being worked in the fields. I’d see the dust rolling up behind tractors that were pulling harrows or disks.

“They’re working that ground,” my father would say. Then for a good while, my mother and I would fall silent, letting him dream of summer when we’d be back for three months, and he could be what he was meant to be, a farmer, climbing on a tractor once more to help the tenant farmer with the wheat harvest, with cultivating beans and corn, with baling hay and straw. “Smell that dirt,” my father would finally say. “That’s home.”

Years later, after he was dead, my mother told me it was his idea for us to move to Oak Forest. She’d lost her teaching position downstate, and he insisted that we couldn’t do without her salary, so she took a job teaching third grade in that Chicago suburb, in spite, as she eventually told me, of her lesser insistence that they would do just fine. “Maybe he just wanted an adventure,” she said. “I don’t know.”

I still can’t make sense of it. That adventure cost him six years of what he loved the most. My father was most happy when he was working his farm. He was willing to swap that for a life of sitting around a one-bedroom apartment, watching quiz shows on television, loafing at an uptown diner, going to my basketball games and band concerts—a man separated from his passion and his land.

What a happy thing it is when our passions and the places we occupy match. To do the thing we love in a place we love? What more could we want?

Those spring evenings on the farm, we sometimes got there early enough to mow the yard, a chore we accomplished with two mowers, one manned by my father and one by me. Often, it was dusk when we finished, the last few swaths taking some guesswork. Then in a deep quiet, after the roar of the mowers, we let the world come back to us a little at a time: the call of a whippoorwill in our woods, the whistle from a distant train, my mother pumping water from our well, peepers trilling at our pond. Oak Forest seemed far, far away. We smelled the cut grass. We let the night settle around us, and without a word we knew, my father and I, that this was good work that we’d done in this place where we belonged.

“We’ll sleep good tonight,” he said, and I agreed, letting his pride become my own. Yes, we would I told him. We surely would.

April 8, 2013

The MFA Thesis Defense: Asking the Right Questions

It’s MFA thesis defense season, and that has me thinking about the best and the worst things that can come from such an exercise.

I remember well my own thesis defense in which I was told all the things I’d done wrong in my slim collection of stories. Helpful? To the extent that it gave me things to pay attention to when I continued writing, thinking all along about what sort of writer I wanted to be, what world I wanted to inhabit, and how I wanted to represent it in my prose, yes. Encouraging? Not much.

What did it teach me? This writing business takes a thick skin, persistence, a willingness to fail, to listen to why I failed, to figure out a way to not fail again while at the same time accepting that I will. Developing as a writer takes an intelligence, an ability to look at one’s work as if you’re not the one who wrote it, an acceptance that there are other writers who know more than you do, who are more talented, who are farther along. Steal from them whenever you can.

At some point in the thesis process, I tell my students that there are two realities: the thesis reality and the reality of the marketplace. An MFA thesis is not always a manuscript on its way to publication, nor should it be. If it is, then great, but what both the student and the advisor should expect from a thesis is a manuscript that highlights the writer’s strengths, weaknesses, and tendencies. The thesis should also provide a means by which both the committee members and the student can begin to assess the material that matters most to the writer and the direction that writer seems to be moving when it comes to best expressing that which compels them. These are the things that can come out of a thesis defense that will send the newly-minted MFA out into the world with some degree of excitement about reworking the thesis or perhaps starting anew with another manuscript.

It took me six years to begin to answer these questions for myself:

1. From what world do I wish to speak? (the small towns and farming communities of my native Midwest)

2. What’s my material? What am I obsessed with? (issues of violence and redemption, the consequences of deceit and betrayal, the blending of the moral and the profane)

3. How is the person, Lee Martin, connected to the writer, Lee Martin? (I spent my adolescence balanced on the thin line between my mother’s compassion and my father’s cruelty; it finally struck me that everything I wrote was in some way an attempt to navigate that boundary)

The answers to these questions aren’t always the same. Depending on where I am in my life and the circumstances I’ve encountered, my answers may change, but these are the questions I needed to be aware of before I could write the stories that ended up in my first book, which was published twelve years after I received my MFA. After my thesis defense, I had to find a way of posing those questions for myself and then setting out to answer them so I could be better prepared to write something that would be worthy of the marketplace. A different thesis defense approach on the part of my committee might have saved me some time, or maybe I was just young and dense and unable to listen in the right way. Still, each time I participate in a thesis defense, I try to keep in mind the young writers upon whom we’ll soon confer a degree. I imagine those writers absent from our program the following autumn, out there somewhere still trying to find their way to the writers they can be. By the time of the defense, I’ve given my students all the answers that I can about their work via workshops and individual conferences. Here at the end, I want to make sure that I give them the right questions.

April 1, 2013

Working Class Students and Creative Writing Workshops

A series of articles has appeared lately about the inclusion of the rural poor in a university’s attempt to admit a diversified group of first-year students. Syndicated columnist, Ross Douthat, writes, “The most underrepresented groups on elite campuses often aren’t racial minorities; they’re working-class whites (and white Christians in particular) from conservative states and regions. Inevitably, the same underrepresentation persists in the elite professional ranks these campuses feed into: in law and philanthropy, finance and academia, the media and the arts.” I was one of those working class whites, and when it came time to make my college choice, it was simple. We had a community college twelve miles from my home. I knew how to drive there. I knew that after two years, I’d transfer to Eastern Illinois University, an hour away from home up Illinois Route 130. That’s what people did in my neck of the woods. I would follow the path that others had set for me. I never even considered the quality of these schools. They were what I knew, and what I knew felt comfortable. That’s about as far as my thinking about college went. I never considered other options. Even the University of Illinois in Champaign-Urbana seemed like a school meant for other people, but not for me. I came from a small town of a thousand people. The year I graduated, our high school had an enrollment of 132 students. My class had twenty-eight people in it. Nearly all of us were the children of working class parents.

Now I teach at one of the largest universities in the country, and I still sometimes feel like that shy country kid who spent a lot of time sitting in his car between classes during that first term at the community college because I didn’t know how to convince myself that I belonged there. The college was in a town of 9,000 people. It was a small town, yes, but to me it was large enough to make me shy. I took note of all the city kids who knew one another. To them, the community college was merely an extension of their high school years. They had an instant community to which they belonged. Although I and a handful of other students from my high school only lived twelve miles away, those twelve miles were enough to make me feel excluded. I was intimidated until I found my own community within the community college. Classes in English and literature allowed me to tap into my natural talents, and I gradually found other people who shared my interests. I found folks who were writing poems and stories, and I finally began to feel at home.

It’s what we’re all looking for, I suppose, those groups that value our talents and will put out the effort to encourage us to find our skills and then to develop them. In the case of creative writing, we who teach it encounter students from various backgrounds, and we try to help them strengthen their craft. We shouldn’t forget that we’re also inviting our students to use their writing to become more confident about the people they’ll be in the world beyond our classrooms. We’re helping them become the people they’re meant to be.

With that in mind, I want to offer some thoughts on three things we can do to make all our students feel included in our workshops:

1. We should be sensitive to any language around the workshop table that might make our students feel that their own experiences aren’t of value. When it comes to the rural poor, words like “white trash,” “trailer trash,” “redneck,” and “hillbilly” particularly get under my skin. I’m sure any ethnic group could come up with their own list of terms which make them grit their teeth, redden with embarrassment, make them wish they were invisible around the workshop table. We should be sensitive to the attitudes that our words suggest even if we think we’re speaking in a good-humored and harmless way.

2. We should also encourage conversations about social class. We can provide exercises for the exchange of stories and facts from various backgrounds so students can begin to value their diverse experiences. Any exercise that invites students to describe their homes and families in direct terms should work as long as we make sure that there’s an atmosphere of mutual respect around the table when it comes time to read from these exercises. For years, I’ve led my students in a round of applause after one of them shares work with us. No matter what the students may be thinking, the act of clapping is one that thanks someone for sharing. It’s my hope that the applause shows the student that his or her experience matters.

3. Finally, we can look for what makes our students’ work unique. We can praise them for taking us into worlds we wouldn’t have otherwise known. We can encourage them to keep writing from the worlds that they know most intimately. “Tell me about the mango trees in Trinidad,” I said once to a student, and she was off and running, recreating the world from which she came in a way that gave her the confidence she needed in order to keep writing about the place and the life she knew best.

Our students are like most people. They like having the chance to talk about what they know. They like being invited to tell stories that only they can tell, stories that come from the places and cultures that created them. So much of teaching is a matter of having good people skills. Like most writers, I get curious about people. I like to ask them questions. I like my students to tell me things I don’t know. The rural poor are accustomed to not having that chance. For a variety of reasons I won’t take the time to fully mention here, students who come from working class families often get the sense that their worlds don’t matter. Often, those worlds, when they appear on television or the movies, aren’t represented in an honorific way. The message is there in subtle and not-so-subtle ways: keep quiet, don’t call attention to yourself, hope that no one notices you. That’s what I felt those days at the community college when I sat in my car, afraid to speak to anyone, afraid that sooner or later someone would figure out that I was a fraud and ask me to leave. It was through creative writing that I finally found a way to speak from my working class world. Now I try to make that possible for all my students, no matter their cultural backgrounds. “Tell me your stories,” I say to them. “Tell me what you know.”

March 25, 2013

You’re Better than Language like That

Help me out here. Last week, I was in the audience for Famous Writer X, who had been invited to my university, and whom said university had paid a handsome sum. We were a diverse audience, made up of community members, university dignitaries, faculty members, graduate students, and a large number of undergraduate students. In short, this was a very big deal, and the audience filled a performance hall in our student union.

Ever since then, I’ve been conflicted when it comes to deciding how I feel about the rather earthy language that Famous Writer X used in his presentation—not the earthy language from the selections of his work that he read, but the language that he used when talking to the audience members or answering their questions during the q and a. One of those questions happened to be, “Why do you use so much profanity in your work?” Famous Writer X responded by saying, “I suppose you’re also wondering why I use so much profanity in my presentation.”

“Well, yes,” I might have said. “I’m curious about that myself.”

Famous Writer X gave an answer to why he used profanity in his work, an answer that I confess I’ve forgotten, but one that I found convincing at the time. Characters are characters, after all, and they speak from their worlds in stories and novels. I understand that. Famous Writer X never got around to addressing the question of why he used so much profanity in his presentation, something I would see repeated at an awards banquet later that evening, a banquet at which he delivered the keynote address. A more formal setting with student scholarship recipients and their families on hand. I was left, then, to try to figure out I felt about our famous guest using such language at these two events.

One part of me understands that such language, such swagger, is part of his persona and obviously an attempt to bond with undergraduate students whom he must assume will relate to his street-wise irreverence. Another part of me thinks, though, that we should all be careful not to assume too much.

I remember when I was an MFA student and just learning how to be a teacher. The professor in charge of teacher training was a wonderful person from whom to learn. He taught us about practical courtesies such as always remembering to erase your chalkboard after your class was done, and being sure not to linger too long into the ten-minute break between classes. “Five minutes belong to you,” he said, “and the other five belong to the instructor of the next class.” One thing he taught us that I’ve always tried to remember was that we should never alienate a student, and, if we thought we had through something we’d said or done, we should correct the matter in private with the student.

I’ve thought of this advice in the days following Famous Writer X’s visit. I’ve thought about how the language he used assumed that his audience used similar language. I should say here that I’m no prude, but I can’t stop thinking about those members of the audience whose vocabulary didn’t include those words that Famous Writer X used and how there may have been some students who felt excluded from the audience that he was assuming would welcome his kind of talk. I’ve also thought about an essay, “No Ears Have Heard,” that I published last year in The Sun Magazine. In that essay, I recall a time when I was a teenager and I came home to find my parents visiting with some friends from church. When my father asked me where I’d been, I said I’d just been out “screwing around.” Mild language compared to the words Famous Writer X favored, but provocative nonetheless. After my parents’ friends were gone, my mother told me I was better than language like that. She asked me whether that phrase was something that I thought those friends would use. I couldn’t answer; I was too ashamed. My mother was a timid, soft-spoken woman. “Then you shouldn’t use it around them,” she said. “Do you understand?”

I did, and I still do. I sometimes fall short of my mother’s lesson, but I try my best to remember not to offend by assuming something about my audience I have no right to assume.

So this is ultimately a lesson about teaching, which as I grow older seems to be more and more about how successfully I can make students comfortable, make them trust me, make them open themselves to what I have to share with them about the craft of writing, invite them to take chances, to try things they haven’t tried before, to push them forward in the development of their talents. To my way of thinking, this is a process that takes a good deal of humility and courtesy, but then again, I’m not Famous Writer X. I could be wrong about all of this. What do you think?

March 18, 2013

In Defense of the Humanities

Recent proposals to privilege those college students who major in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM), by charging them lower tuition than their peers who major in the humanities have me feeling more than a little cantankerous. I remember a piece by John Ciardi that I first encountered when I was a new teaching assistant at the University of Arkansas. I want to share a lengthy excerpt from that piece, “Another School Year: Why?” I know that blog posts shouldn’t be this long, but this is an important issue, and I can’t think of a smarter and more eloquent response to STEM than these words from Ciardi:

Another School Year: Why?

Let me tell you one of the earliest disasters in my career as a teacher. It was January of 1940 and I was fresh out of graduate school starting my first semester at the University of Kansas City. Part of the reading for the freshman English course was Hamlet. Part of the student body was a beanpole with hair on top who came into my class, sat down, folded his arms, and looked at me as if to say: “All right, damn you, teach me something.” Two weeks later we started Hamlet. Three weeks later he came into my office with his hands on his hips. It is easy to put your hands on your hips if you are not carrying books, and this one was an unburdened soul. “Look,” he said, “I came here to be a pharmacist. Why do I have to read this stuff?” And not having a book of his own to point to, he pointed at mine which was lying on the desk.

New as I was to the faculty, I could have told this specimen a number of things. I could have pointed out that he had enrolled, not in a drugstore-mechanics school, but in a college, and that at the end of this course, he meant to reach for a scroll that read Bachelor of Science. It would not read: Qualified Pill-Grinding Technician. It would certify that he had specialized in pharmacy and had attained a certain minimum qualification, but it would further certify that he had been exposed to some of the ideas mankind has generated within its history. That is to say, he had not entered a technical training school, but a university, and that in universities students enroll for both training and education.

I could have told him all this, but it was fairly obvious he wasn’t going to be around long enough for it to matter: at the rate he was going, the first marking period might reasonably be expected to blow him toward the employment agency.

Nevertheless, I was young and I had a high sense of duty and I tried to put it this way: “For the rest of your life,” I said, “your days are going to average out to about twenty-four hours. They will be a little shorter when you are in love, and a little longer when you are out of love, but the average will tend to hold. For eight of those hours, more or less, you will be asleep, and I assume you need neither education nor training to manage to get through that third of your life.

“Then for about eight hours of each working day, you will, I hope, be usefully employed. Assume you have gone through pharmacy school—or engineering, or aggie, or law school, or whatever—during those eight hours you will be using your professional skills. You will see to it during this third of your life that the cyanide stays out of the aspirin, that the bull doesn’t jump the fence, or that your client doesn’t go to the electric chair as a result of your incompetence. These are all useful pursuits, they involve skills every man must respect, and they can all bring you good basic satisfactions. Along with everything else, they will probably be what sets your table, supports your wife, and rears your children. They will be your income, and may it always suffice.

“But having finished the day’s work what do you do with those other eight hours—the other third of your life? Let’s say you go home to your family. What sort of family are you raising? Will the children ever be exposed to a reasonably penetrating idea at home? We all think of ourselves as citizens of a great democracy. Democracies can exist, however, only as long as they remain intellectually alive. Will you be presiding over a family that maintains some basic contact with the great continuity of democratic intellect? Or is your family going to be strictly penny-ante and beer on ice? Will there be a book in the house? Will there be a painting a reasonably sensitive man can look at without shuddering? Will your family be able to speak English and to talk about an idea? Will the kids ever get to hear Bach?”

That is about what I said, but this particular pest was not interested. “Look,” he said, “you professors raise your kids your way; I’ll take care of my own. Me, I’m out to make money.”

“I hope you make a lot of it,” I told him, “because you’re going to be badly stuck for something to do when you’re not signing checks.”

Fourteen years later, I am still teaching, and I am here to tell you that the business of the college is not only to train you, but to put you in touch with what the best ideas human minds have thought. If you have no time for Shakespeare, for a basic look at philosophy, for the community of the fine arts, for that lesson of man’s development we call history—then you have no business being in college. You are on your way to being that new species of mechanized savage, the Push-button Neanderthal. Our colleges inevitably graduate a number of such life forms, but it cannot be said that they went to college; rather, the college went through them—without making contact.

No one gets to be a human being unaided. There is not enough time in a single lifetime to invent for oneself everything one needs to know in order to be a civilized human.

Assume, for example, that you want to be a physicist. You pass the great stone halls, of say, MIT, and there cut into stone are the names of the master scientists. The chances are that few of you will leave your names to be cut into those stones. Yet any one of you who managed to stay awake through part of a high school course in physics, knows more about physics than did many of those great makers of the past. You know more because they left you what they knew. The first course in any science is essentially a history course. You have to begin by learning what the past learned for you. Except as a man has entered the past of the race he has no function in civilization.

And as this is true of the techniques of mankind, so is it true of mankind’s spiritual resources. Most of these resources, both technical and spiritual, are stored in books. Books, the arts, and the techniques of science, are man’s peculiar accomplishment.

When you have read a book, you have added to your human experience. Read Homer and your mind includes a piece of Homer’s mind. Through books you can acquire at least fragments of the mind and experience of Virgil, Dante, Shakespeare—the list is endless. For a great book is necessarily a gift: it offers you a life you have not time to live yourself, and it takes you into a world you have not time to travel in literal time. A civilized human mind is, in essence, one that contains many such lives and many such worlds. If you are too much in a hurry, or too arrogantly proud of your own limitations, to accept as a gift to your humanity some pieces of the minds of Sophocles, of Aristotle, of Chaucer—and right down the scale and down the ages to Yeats, Einstein, E.B. White, and Ogden Nash—then you may be protected by the laws governing manslaughter, and you may be a voting entity, but you are neither a developed human being nor a useful citizen of a democracy.

I think it was La Rochefoucauld who said that most people would never fall in love if they hadn’t read about it. He might have said that no one would ever manage to become a human if he hadn’t read about it.

I speak, I am sure, for the faculty of the liberal arts colleges and for the faculties of the specialized schools as well, when I say that a university has no real existence and no real purpose except as it succeeds in putting you in touch, both as specialists and as humans, with those human minds your human mind needs to include. The faculty, by its very existence, says implicitly: “We have been aided by many people, and by many books, and by the arts, in our attempt to make ourselves some sort of storehouse of human experience. We are here to make available to you, as best we can, that experience.”

March 11, 2013

Seven Lessons I Learned from Ray Bradbury

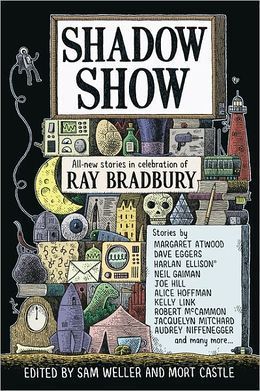

I was fortunate enough to be on a panel at this year’s AWP conference in Boston with Mort Castle, Alice Hoffman, John McNally, and Sam Weller. What did we all have in common? An appreciation of Ray Bradbury and original stories published in the tribute anthology, Shadow Show. The panel, “Shadow Show: Writers and Teachers on the Influence of Ray Bradbury and Other Genre-Bending Authors,” took place during what’s usually a deadly time at AWP, 4:30 on Saturday, the last day of the conference. By that time, many attendees have already caught flights home or are too exhausted or hung over to make it to the last sessions. What a pleasant surprise it was, then, to find our room filled with people, some of them standing in the back. The questions and comments from the audience after the panelists’ remarks were lively and stimulating. I’ll tell you this: there was a good deal of love in that room, enough to lift us up and send us home with the exhortation from Sam Weller, channeling the spirit of Ray Bradbury, to write. “Why aren’t you writing?” Sam thought Bradbury would say to us. “Go home and write.”

I was fortunate enough to be on a panel at this year’s AWP conference in Boston with Mort Castle, Alice Hoffman, John McNally, and Sam Weller. What did we all have in common? An appreciation of Ray Bradbury and original stories published in the tribute anthology, Shadow Show. The panel, “Shadow Show: Writers and Teachers on the Influence of Ray Bradbury and Other Genre-Bending Authors,” took place during what’s usually a deadly time at AWP, 4:30 on Saturday, the last day of the conference. By that time, many attendees have already caught flights home or are too exhausted or hung over to make it to the last sessions. What a pleasant surprise it was, then, to find our room filled with people, some of them standing in the back. The questions and comments from the audience after the panelists’ remarks were lively and stimulating. I’ll tell you this: there was a good deal of love in that room, enough to lift us up and send us home with the exhortation from Sam Weller, channeling the spirit of Ray Bradbury, to write. “Why aren’t you writing?” Sam thought Bradbury would say to us. “Go home and write.”

My contribution to Shadow Show, a story titled “Cat on a Bad Couch,” was a response to the only story that Bradbury published in The New Yorker. His story, “I See You Never,” touched me the first time I read it. It’s a poignant portrait of loss and what it means to try to make a home for oneself far away from one’s native land. In a little more than a thousand words, Bradbury tells the story of Mrs. O’Brian, whose tenant, Mr. Ramirez, has come in the presence of police officers to tell her he must give up his room as he’s being returned to Mexico; his temporary visa has long ago expired and the police have now discovered that fact. He’ll have to give up his job at the airplane factory, where he makes a good wage. He’ll have to give up his clean room with the blue linoleum and the flowered wallpaper. Most of all, he’ll have to give up Mrs. O’Brian, his “strict but kindly landlady,” who doesn’t begrudge him the right to get a little drunk at the end of the week.

I’ve used this story for years in my fiction workshops, asking my students to notice how skillfully Bradbury evokes the aching loss at the heart of the story by paying such careful attention to the details of Mrs. O’Brien’s home—the huge kitchen, the long dining table covered with a white cloth and laden with water glasses and pitcher and bright cutlery and platters and bowls, the freshly waxed floor—and the facts of Mr. Ramirez’s pleasant life in Los Angeles—the radio and wristwatch he bought, the jewels he purchased for his few lady friends, the picture shows he attended, the streetcar rides he took, the grand restaurants where he dined, the opera and the theater. Those details contrast with what Mrs. O’Brien recalls from a visit she once made to a few Mexican border towns—dirt roads, scorched fields, small adobe houses, an eroded landscape. Such is the world to which Mr. Ramirez must return, and the details of the story do the work of portraying his heartache. No need for the author to offer comment.

I ask my students to notice how Bradbury stays out of the way, allowing Mr. Ramirez’s agony to emerge organically form the details of the story. Mr. Ramirez says, “Mrs. O’Brian, I see you never, I see you never!” In the final move of the story, Mrs. O’Brien, sitting down to dinner with her children, realizes that this is indeed true, and again the details evoke her melancholy. With graceful understatement, Bradbury describes how she quietly shuts the door and returns to her dining table, how she takes a bit of food and chews it a long time, staring at the closed door. Then she puts down her knife and fork, and when her son asks her what’s wrong, she says she’s just realized—here she puts her hand to her face—that she’ll never again see Mr. Ramirez. The full brunt of her loss comes to her when it’s too late for her to express her sadness to him the way he has to her. Notice the irony in that last move, I tell my students, how it comes to us covertly because a skillful writer lets it emerge from the details of the story’s world.

I’m always interested in characters who are trying to live decent lives in spite of the human flaws that get in their way. In this same way, Bradbury’s work explores what Faulkner called the “verities and truths of the heart” in prose that expresses the fragility of everything. That sense of possible loss is always hovering and the question of how to behave in the face of that fact is what drives so much good literature.

Like Bradbury, I came from Illinois, living downstate and eventually spending six years of my childhood in Oak Forest, a southern suburb of Chicago. Because I found myself drawn toward tales that fell into the category of what I’ll call Midwestern gothic, I suppose my first mentors were those that some might call genre writers or popular writers, but whom I’ll call storytellers. Of course, Ray Bradbury was one of those. Here, in closing, are some of the other things I learned from Bradbury that I carried over into my literary fiction.

1. Let the characters create a plot made up of choices, actions, and consequences.

2. If that plot has an element of mystery or intrigue, all the better.

3. Make the familiar strange and the strange, familiar.

4. Create a vivid world from closely observed details

5. Give your language energy and simplicity.

6. Get on the stage quickly, do what you have to do, exit gracefully.

7. Pay attention to your own nightmares; don’t be afraid of your imagination.

Bradbury always cited Jules Verne and H. G. Wells as two of his biggest influences, but he also learned from writers such as John Steinbeck, Eudora Welty, and Katherine Anne Porter. Always, he was interested in not only telling a gripping tale but also touching his readers’ hearts. “If you’re reluctant to weep,” he said once, “you won’t live a full and complete life.” He approached his work, unafraid of his imagination and his emotions. Of Verne, he said, “He believes the human being is in a strange situation in a very strange world, and he believes that we can triumph by behaving morally.” To me this sounds like a belief that can pay off handsomely for both writers of genre and literary fiction. A good tale shouldn’t be divorced from a nuanced portrayal of characters, nor should a character study be devoid of plot. Ray Bradbury taught me a little bit of both. He taught me how to entertain while also turning a keen eye to the mysteries of ordinary folks.

March 4, 2013

A March Miscellany

Benediction

This morning, I finished Kent Haruf’s new novel, Benediction, and it has me thinking about how good literature requires courage on the part of the author while also asking the same from the readers. I say it requires courage because a book worth writing, and one worth reading, asks us to face our lives, and, if we’re truthful, we’ll admit that our lives are made up of small pleasures but also great disappointments and regrets, sadness, and an uncertainty of what lies beyond the here and now. Kent Haruf has the courage to look straight on with depth and humility at all of this in this story of a man dying of cancer and the ties that bind those around him. The book holds small moments of pleasure in what one of the characters calls, “the precious ordinary,” but it’s also an uncompromising look at the end of a life and one that doesn’t pull any punches in its portrayal. It is, simply put, life on the page, and I applaud Kent Haruf for having the courage to tell it to us plain. I’ve read some reviews that grumble about Dad Lewis being a character that it’s hard to root for. To those reviewers, I’d say that Dad Lewis is a flawed human being, as we all are, and, therefore, all the more interesting and memorable.

AWP in Boston

I’m wishing everyone who will be going to the AWP Conference in Boston safe travels. After my little health scare back in the fall, I’m very much looking forward to being with my family of writers. Please say hello, if you happen to spot me. I’ve missed you all. Here are a couple of panels that I’m on in case they might be of interest to you:

Friday, March 8

1:30-2:45

Room 111

Plaza Level

F199. Turning in Their Graves: Researching, Imagining, and Shaping Our Ancestors’ Stories. (Rebecca McClanahan, Lee Martin, Mary Clearman Blew, Suzanne Berne, Sharon DeBartolo Carmack) Five authors, including a Certified Genealogist, share their varied experiences of writing about family and ancestral roots, offering suggestions for every stage of the journey: accessing archival sources; sifting through facts to discover meaning, theme, and universal truths; deciding if and when to invent or fictionalize; shaping the material into and artful text; and dealing with all the consequences of the published work.

Saturday, March 9

4:30-5:45

Room 194

Plaza Level

S239. Shadow Show: Writers and Teachers on the Influence of Ray Bradbury and Other Genre-Bending Authors. (Sam Weller, Mort Castle, Alice Hoffman, Lee Martin, John McNally) Four accomplished authors discuss the literary shadow of Ray Bradbury, and the history of blurring genres in literature. The panel includes Bradbury biographer, Sam Weller; seven-time Bram Stoker Finalist, Mort Castle; #1 New York Times Bestseller, Alice Hoffman; Pulitzer nominee, Lee Martin. Each panelist will discuss Bradbury’s influence on their career. They will examine the increasingly porous boundaries between genre and literature.

I’ll also be reading as part of The Journal’s 40th Anniversary Celebration. That will take place on Friday evening at 10pm in Room 2309 of the Sheraton.

The kickoff event, though, will be Wednesday evening, March 6, at 7pm at Brookline Booksmith. 279 Harvard St.; Brookline, MA (617-566-6660). I’ll be joining some other folks with stories in Shadow Show, the Ray Bradbury tribute anthology, mentioned above for a discussion of the collection http://www.brooklinebooksmith.com/events/mainevent.html

Spring

The nature guy’s column in my morning paper assures me there are signs of spring: red-winged blackbirds have been spotted, chipmunks have awakened from their winter’s naps, skunk cabbage is up in the woods. I’m hoping these harbingers of spring will coax the warm weather out of hiding. It hasn’t been a particularly hard winter here in Columbus, Ohio, but just cold enough to make me long for the warmth of the sun. Spring training baseball games are underway. The NCAA tournament will start before we know it. Hang in there, everyone. Keep doing the good work. I think we’re going to make it.

February 25, 2013

Post-MFA Advice: Part Two

My post last week, in which I offered some advice to those about to graduate with their MFAs, got a good deal of response along with a request to offer more information about the sorts of jobs that might be possible. I decided, then, to go to folks more expert than I, recent grads from the MFA program at Ohio State. I asked them to share their experiences in those first few years after graduation and to offer any advice that they might have.

Some folks made teaching their priority even if it meant having to adjunct or take a non-tenure-track lectureship or a visiting appointment. Those temporary gigs better prepared folks for their first tenure-track positions. One person outlined the benefits of following this path:

1. I gained valuable post-MFA teaching experience, which made my application much stronger when I went on the job market the next year.

2. I made new friends and professional contacts

3. VAP positions are obviously less competitive than tenure-track jobs

4. Spending one year in a new part of the country often felt less like work and more like an extended vacation (which is not to say that the work was easy)

Some folks talked about going straight from the MFA to a Ph.D. program. One person offered the following advice:

I’m always happy to talk with folks about Ph.D. programs, mistakes I made and things I would do differently–like choosing your subject areas WISELY and diversifying your creative and critical output. Colleges and universities these days love people who can do EVERYTHING. (I’ll add that I found this to be true of my own Ph.D. experience. I chose Composition Theory as one of my secondary areas and Modern British and American Literature as the other so I could market myself as a generalist who could teach creative writing, composition, and lit. surveys.)

I should add here that at least one person I talked to decided to return for a graduate degree in Social Work with the hopes of landing a job with benefits, rather than continuing with adjunct teaching. “I love teaching,” she says, “but it’s a hobby I can’t afford as a single mom. I’m still writing, though! Free advice: you don’t have to take the GRE again if you want to get another grad degree at OSU, no matter how long you’ve been out. Once a grad student, always a grad student.”

One person went to law school and then practiced law for a year before landing a fellowship that allowed her to get back into teaching. I imagine a law degree would always provide a nice fall-back option if needed.

Other folks got jobs in academic advising. In fact, I know more than one OSU alum who has secured these sorts of jobs at OSU. One of these folks said, “I would agree that finding time for writing and publishing is key, and I think it can be done with a full time job, but you have to be pretty ruthlessly willing to write when you can write.” Another person had this to say:

In terms of how this sort of job (which is 8-5, M-F, year-round) fits in with my creative writing pursuits, it’s a better fit for me than teaching because I feel I am using a different skill set that compliments my writing rather than tiring me out (which teaching writing can sometimes do–especially when grading lots of composition papers). The downside is that the schedule of an advisor can be rigid and we don’t have the opportunity for breaks between semesters (in fact the “breaks” in semesters are when we are the busiest).

This same person offered this excellent job-seeking advice:

In terms of words of advice for those about to graduate–be hopeful–talk to your thesis advisor, talk to your friends, and family members about possible job opportunities. Don’t underestimate the skills you have! Apply for all the post-MFA fellowships out there but also use Career Connection: http://careerconnection.osu.edu/ to have your resume reviewed and to practice your interviewing skills.

Another person landed a job as a Program Coordinator with the Migrant Education Program:

Although I work in rural small valley towns where they grow rice, walnuts, almonds, grapes, beans, I do a lot of writing, analyzing, managing, planning, negotiating, and training of staff. I get paid a mid-level teacher salary with benefits and retirement. The job depended more on my years as a high school teacher and my teaching credential more than the MFA. However, the MFA has made my job so much easier. I’m not sure how, but I picked up the academic government language fairly quickly. So I write sentences such as “According to the data from the California Department of Education, 20% of migrant students scored at Proficient or Advanced on the . . .” for pages and pages. It’s like creative writing because often the data we get is flawed. But the flow and confidence from the MFA program and the teaching opportunities have really helped.

Another person described his search for a job in advertising, publishing, university administration, and the nonprofit sector. Here’s his advice:

1) Apply far and wide. Job searching is a full-time gig in this difficult job market. I was at my desk from 8-5 during the week seeking open positions and applying for them. It sucked. But it worked out eventually.

2) Gather a sample of professional writing. Writing-intensive jobs often require you provide a sample of professional writing. Be prepared for this.

3) Teaching, coursework, and any other part-time professional experience completed during the MFA is valid. But it has to be sold as such. Every cover letter and resume is an argument for why your experience makes you capable of excelling in the vacant position. There are a lot of skills in teaching that translate to other jobs, and I found interviewers were cognizant of that.

4) Freelance-to-hire, contract, and contract-to-hire work may be worth looking into, depending on the field you’re looking at.

In similar fashion, another recent grad ended up working as a web producer, managing editorial projects for publication. “It’s a demanding full-time job,” she says, “and carving out time for writing is a balancing act, but it can be done, with difficulty.” I’ll attest to that. I know that this person just had a piece accepted at a premier literary journal.

Another recent grad ended up in Los Angeles writing for television shows:

It’s a great job that pays very well and it’s more fun than a job should be, but it’s also very inconsistent. In 2011, I didn’t work much and I was officially employed for about 3/4 of 2012. Much of my fiction-writing energy is taken up by my tv writing now, but lately I’ve been better about carving out time to work on my own prose projects.

Another person spoke about the importance of protecting writing time by free-lancing for the first five years after graduation: “conducting focus groups, writing corporate reports, some editing freelance work.” In this same vein, another recent grad said,

My big advice, which I followed, was to find a job that required no more than 40 hours of work, including commuting, so that I could finagle at least 10 hours of writing time a week. Prioritize writing; then let everything else fall into place. That’s my advice.

A few people talked about the harsh realities of our personal lives that can sometimes stand in the way of our writing careers. Tremendous losses, illnesses, self-doubt, disappointments, questions of whether the degree was worth the effort. One person wished that she’d known that others have felt the same way before she walked away with that MFA in hand and so many hopes for the future. “I think post-MFAs should be prepared for the potential feeling of hitting a wall and not knowing what to do about it,” this person said.

I quite agree. It can be a shock to find yourself away from the setting that meant so much to you, that workshop room where people paid such close attention to your work, those professors’ offices where your mentors did their very best to help your talents develop. It’s doubly hard if your life hands you some sadness to deal with at the same time you doubt your abilities. The MFA is not always a golden ticket. That’s for sure.

Here’s something I’ll confess: that feeling of self-doubt has never completely disappeared for me. I still have times when I wonder whether I’m good enough; I imagine other writers feel the same way. The one thing I know for sure (and I think everyone who so kindly responded to my call for their post-MFA stories would agree) is that writing is a necessity for me, and it always was even in those days when I wasn’t publishing and was seriously thinking about giving it all up. The only problem was I couldn’t. I couldn’t stop thinking of story ideas, couldn’t stop shaping sentences until they pleased me, couldn’t stop “writing” even when I wasn’t.

I sometimes worry about how easily we seduce so many young writers into our MFA programs, all of them with dreams of publication in their eyes. We know the market for teachers is glutted. We know that our students will sometimes incur a good deal of debt with student loans. We know that not every student will achieve the goals that he or she has. We owe our students some straight talk about the odds. We owe them our support even after they’ve left our programs. We owe them options and advice. I apologize for the length of this post, but this is important, and I hope it’ll be helpful. I’ll close with my thanks to those who spoke so eloquently and urgently about their own experiences, and with all good wishes and blessings for those of you about to graduate.