David R. Stokes's Blog, page 9

June 10, 2013

Alinksy, Chambers, and the Rest of Us

[This column is currently posted at TOWNHALL]

[This column is currently posted at TOWNHALL]

A few years ago, when I finally got around to reading Saul Alinsky’s book, Rules for Radicals, I learned some vital things about culture warfare. Every American should read it. It’s chilling. The scary stuff begins on the book’s dedicatory page:

Lest we forget at least an over-the-shoulder acknowledgment to the very first radical: from all our legends, mythology, and history… the first radical known to man who rebelled against the establishment and did it so effectively that he at least won his own kingdom — Lucifer.

George Washington died because of misguided notions about how getting the bad blood out via leeches would cure his ailment. It was a case of a cure that killed. Sure, his cold was gone, but so was he. In a sense, the draconian measures some would use to remake our nation’s fabric, from health care, to national security, to the economy itself, are somewhat akin to bleeding the nation en route to restoration.

All this has done is to make us a weaker nation on so many levels.

As a pastor, I have preached sermons based on a haunting passage from the writings of the prophet Jeremiah called. The prophet was a patriot, but he knew that sometimes patriotism involved even more than waving a flag – a stand must be taken. His message was:

“Stand at the crossroads and look; ask for the ancient paths, ask where the good way is, and walk in it, and you will find rest for your souls.” — Jeremiah 6:16 (New International Version)

Jeremiah was speaking to his nation at a pivotal moment – a time that called for clear thinking and action. They had been on a slippery slope for a long time and the clock was running out. Nothing short of a return to what made them strong – even great – in the first place would correct the problem.

In March of 1946, Winston Churchill traveled to diminutive Fulton, Missouri to deliver his most famous speech—the one that talked about a sinister iron curtain born of Soviet expansionism.

That very week, Time Magazine published a review about two recently published books. One was a work by Frederick L. Schuman, the Woodrow Wilson professor of government at Williams College, called Soviet Politics. It was basically a defense of the Soviet system. The other book was Saul Alinksy’s Reveille For Radicals —the prequel to Rules for Radicals. The title of the review was, Problem Of The Century.

The reviewer suggested that, “the dominant problem of the 20th century is the reconciliation of economic liberty with political liberty.” He saw this issue resolved in Schuman’s book by simply “liquidating political liberty.” He saw Alinsky’s ideas in a little more favorable light, suggesting that it was written with a “burning honesty” and that the author had “glimpsed a vision which is greater than his ability to put it in practical terms.” In fact, that particular reviewer did not live long enough to see the fruit of Saul Alinsky’s attempt to put his vision into those “practical terms.” That would come later in Rules For Radicals. But the reviewer died 10 years before that.

That reviewer’s name was Whitaker Chambers.

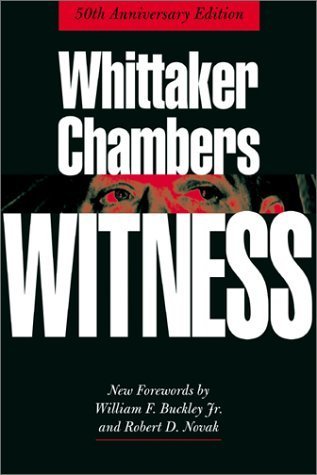

Though he never got to write a review of Rules for Radicals, but he did write a book of his own. It became a classic with a simple title, Witness.

Witness was the testimony of a man who had once been a communist, even a spy. Chambers ultimately saw the light and spent the rest of his days fighting—at great personal price—his former “faith.” Along the way, he exposed a traitor or two, gaining him the wrath of the liberal elite in America, though he has long since been vindicated as a truth-teller by many infallible proofs.

He began Witness with a letter to his children, letting them know the nature of the struggle and the craftiness of the enemy:

Communists are bound together by no secret oath. The tie that binds them across the frontiers of nations, across barriers of language and differences of class and education, in defiance of religion, morality, truth, law, honor, the weaknesses of the body and the irresolutions of the mind, even unto death, is a simple conviction: It is necessary to change the world.

It is not new. It is, in fact, man’s second oldest faith. Its promise was whispered in the first days of the Creation under the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil: ‘Ye shall be as gods.’ It is the great alternative faith of mankind. Like all great faiths, its force derives from a simple vision. Other ages have had great visions. They have always been different versions of the same vision: the vision of God and man’s relationship to God. The Communist vision is the vision of Man without God.

It is the vision of man’s mind displacing God as the creative intelligence of the world. It is the vision of man’s liberated mind, by the sole force of its rational intelligence, redirecting man’s destiny and reorganizing man’s life and the world.

The Communist vision has a mighty agitator and a mighty propagandist. They are the crisis. The agitator needs no soapbox. It speaks insistently to the human mind at the point where desperation lurks. The propagandist writes no Communist gibberish. It speaks insistently to the human mind at the point where man’s hope and man’s energy fuse to fierceness. The vision inspires. The crisis impels.

Whatever else you have on your summer reading list, I suggest you include Rules for Radicals and Witness—two very different books—two very different visions. They are every bit as different as two famous roads—one called “the broad way,” the other, “the straight and narrow.”

And they lead to two very different destinations.

June 5, 2013

The Boys Who Saved the World for the Rest of Us

[This is a preview of my column for TOWNHALL.COM. It will appear tomorrow, June 6th -- the 69th anniversary of D-Day -- DRS]

It made the papers, but was covered far from sufficiently, when Elisha “Ray” Nance died a few years ago at the age of 94. You may never have heard of him, but he was well known around Bedford, Virginia, a picturesque town located at the feet of the Blue Ridge Peaks of Otter. He delivered mail in that neck of the woods for many years. But it was for what he did before becoming a letter carrier that he should be best remembered.

Ray Nance was one of The Bedford Boys.

The Bedford Boys

In fact, he was the last surviving member of his town’s contingent in Company A of the 29th Infantry Division’s 116th Infantry – a group that waded ashore on a beach nicknamed Omaha in a far away place called Normandy, 69 years ago. And of the 30 soldiers from Bedford, then with a population of 3,200 (today, about twice that), he was one of only eight from his hometown who lived to tell the story.

Ray lost 22 Bedford buddies that day, 19 of them in the very first moments of the battle. By the time he made it to the beach in the last of his company’s landing crafts to reach that point, he saw “a pall of dust and smoke.” He could barely see “the church steeple we were supposed to guide on.” He couldn’t see anyone in front, or behind him; only that he “was alone in France.” Mr. Nance was a hero “proved through liberating strife.”

In so many ways, it’s a different world today. But interestingly – even ironically – the challenges of our times are not completely unlike those days when bands of citizen-soldier-brethren from the greatest generation saved the world for those of us who would later be born to abundance and liberty.

Next to ingratitude, forgetfulness is the most serious indicator of cultural decline; and in truth, the two are intertwined. Thankfulness and remembrance are flip sides of the same precious cultural coin.

It always bothers me when leaders—those born out of due time—seem to apologize for America and our various endeavors to make this world a better (read: more free) place.

I find myself thinking back to a moment 29 years ago when, on the 40th anniversary of D-Day, President Ronald Reagan captured the attention of history and honored some of the other “Boys” who did so much for all of us on June 6, 1944. He called them “The Boys of Pointe Du Hoc,” and many of them were in his cliff-top audience in Normandy that day—June 6, 1984.

If you wanted to pick a more foreboding, certainly unlikely, place for an important military attack, you’d be hard-pressed to come up with a spot more uninviting than the imposing, rugged cliffs overlooking the English Channel four miles west of Omaha Beach. A few years ago, I had the privilege of visiting the Normandy region for a speaking engagement. I stood on the spot where the Great Communicator spoke and tried to wrap my mind around the quite-evident impossibility of what the United States Army Ranger Assault Group accomplished that fateful day. Mr. Reagan honored those men there:

We stand on a lonely, windswept point on the northern shore of France. The air is soft, but 40years ago at this moment, the air was dense with smoke and the cries of men, and the air was dense with smoke and the cries of men, and the air was filled with the crack of rifle fire and the roar of canon. Behind me is a memorial that symbolizes the Ranger daggers that were thrust into the top of these cliffs. And before me are the men who put them there. These are the boys of Pointe Du Hoc. These are the men who took the cliffs. These are the champions who helped free a continent. These are the heroes who helped end a war.

Now, all these years later, we mark another anniversary of D-Day. But the boys of Bedford are now all gone. And noble ranks of the boys of Pointe Du Hoc have been thinned out by the course of time, as well. So, what happens when those who really remember are no longer around to remind us? What happens when eyewitness memory is no longer vivid and available and we must resort to stories handed down from generations before?

This is where (and why) memorials come in, monuments to important men and moments of a sacred and so-easily-forgotten past.

It has a dozen years since the national D-Day Memorial opened in June of 2001 in that tiny Virginia town of Bedford, a community that gave so proportionately of its finest young men so many years ago. A while back, my wife and I, along with other family members, visited the D-Day Memorial. I talked to my grandkids about it all. The man who took us around was Mr. James E. Bryant. He had served as a Glider Infantryman with the 82nd Airborne Division and was part of all of his division’s campaigns from D-Day through to the end of the European war in May of 1945. He wrote a book about it all called, Flying Coffins Over Europe. I purchased a copy in the Memorial’s gift shop and asked him to sign it for me. I was honored and humbled to be in his presence. Really.

So, today I find myself missing the eloquence of Ronald Reagan and remembering how he honored “the Boys.” I also ponder the Great Communicator’s words from that inspirational speech in Normandy:

Strengthened by their courage, heartened by their valor, and borne by their memory, let uscontinue to stand for the ideals for which they lived and died.

Amen!

Why Did I Decide to Write Fiction?

[I will be contributing a couple of posts a month henceforth to an excellent site called VENTURE GALLERIES --- really worth checking out, great books and great people. -- DRS]

So, I decided to write a novel. This might not sound like that big of a deal for a writer, but it turned out to be a major moment in my life. Really.

You see, not only had I not ever written fiction before—I rarely read it. And by rarely, I mean I’d read one work of fiction for every 100 nonfiction books I’d consume. [READ THE COMPLETE POST HERE]

April 22, 2013

Don’t Let’s Be Beastly to the Islamists ;)

Noel Coward

The obviously sarcastic title of this column comes from the days of World War II. Noel Coward, then a famous playwright and popular British entertainer, wrote a song in 1943 titled, “Don’t Let’s Be Beastly to the Germans.” It was an instant hit. Prime Minister Winston Churchill liked it so much that he once had Mr. Coward sing seven encores in a row for him. He also gave the entertainer a few espionage assignments.

By then, chronic bombing by the Nazis and Winston Churchill’s persistent and ever eloquent emphasis on vigilance and victory steeled most Britons with the will to endure the worst. A slogan, Keep Calm and Carry On, was designed for posters to be used in case of an actual Nazi invasion. But it never had to be trotted out (though it emerged from mothballs decades later to become a popular and much parodied 21st century mantra). It was replaced by flesh and blood, as Churchill himself became the image of the era and his voice its soundtrack.

But Mr. Coward observed that a small, yet increasingly vocal number of people—self-styled sophisticates—challenged the militant attitude of the majority, even to the point of advocating more understanding and sympathy toward the Germans—this in 1943. And ideas were promoted that envisioned a post-war period of overweening and merciful munificence. So Coward wrote pungent and satirical lyrics to mock such naïve thinking:

Don’t let’s be beastly to the Germans

When our victory is ultimately won,

It was just those nasty Nazis

Who persuaded them to fight,

And their Beethoven and Bach

Are really far worse than their bite!

Let’s be meek to them

and turn the other cheek to them,

And try to bring out their latent sense of fun.

Let’s give them full air parity

and treat the rats to charity

But don’t let’s be beastly to the Hun!

Don’t let’s be beastly to the Germans,

For you can’t deprive a gangster of his gun!

Though they’ve been a little naughty

To the Czechs and Poles and Dutch,

I don’t suppose those countries

Really minded very much.

Don’t let’s be beastly to the Germans

When the age of peace and plenty has begun.

We must send them steel and oil and coal

And everything they need,

For their peaceable intentions

Can be always guaranteed!

Let’s employ with them

A sort of “strength through joy” with them,

They’re better than us at honest manly fun.

Let’s let them feel they’re swell again

And bomb us all to hell again,

But don’t let’s be beastly to the Hun!

Interestingly, some took Coward’s lyrics literally and thought the song was too pro-German, causing it to be eventually banned from the BBC.

In our day, and in the aftermath of yet another compelling example of the pernicious power of Islamism, we also hear voices dismissing the idea that there is really any pervasive threat to our security and way of life. Rhetoric is twisted and tortured to “prove” that what Tamerlan and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev did was an isolated case and not tied to any official terrorist “network.” But that rush to avoid judgment is worse than premature—it’s perilous.

The brothers may have acted alone (though this is far from certain), but they were actually far from alone at any time while planning their sordid deed. They were aided and abetted by resources made readily available by a very determined foe in the service of a deadly ideology. Regular and repeated reports about how the motives of the bombers “remain a mystery,” continue to do all of us a great disservice.

For several days now, media outlets in other countries, particularly Great Britain, have been reporting about an on-going investigation by the FBI into a “12-strong sleeper cell.” But the mainstream media here in the U.S. dismisses such reports, likely because they suggest an inconvenient narrative.

So, by all means, don’t let’s be beastly to the Islamists. Let’s accept every word in every CAIR (Council on American Islamic Relations) press release as divinely inspired. Let’s not jump to conclusions unless they are politically correct.

Many political leaders, beginning with President Obama, are shaking their heads in disbelief while talking about the “mystery” and “paradox” of young men who spent so much time here in America doing what they did. But the answer is quite simple. They believed in a basic code: “Islam is the solution.”

I use the term Islamist to describe what is often called radical Islam, though the Associated Press recently put my preferred nomenclature on its do not fly list. The reason some are uncomfortable with the use of Islamist is obvious. Part of the word is Islam. The idea is that every attempt should be made to disconnect violence from the religious identifier.

I understand the logic. But all such attempts are doomed to fall short because there in fact exists a very real connection between the religion itself and its violent variant. This does not mean my Muslim neighbors are all terrorists—certainly not. They are kind and decent people and I like them. Beyond that, as a Christian, I am commanded to love my neighbor.

But when it comes to the idea of Sharia, a term describing the body of Islamic sacred law, it gets very complicated, to say the least. Sharia is “the backbone of mainstream Islam” and therefore “intrinsically problematic.” The thrust is supremacy in all areas and walks of life.

And here’s the point too many Americans miss: Most devout Muslims believe in the precepts and goals of Sharia. So in practical terms it means that they believe in the replacement of existing codes of governance—in our case the U.S. Constitution itself. Not every devout Muslim believes in the violent overthrow of our government and way of life, but they all believe in the replacement of our government and way of life with Sharia. In other words, they believe in the ends—Sharia supreme—but not all believe in violent means.

So it’s not just “terrorism” that we should be concerned about—it’s the ideology itself.

Then there is the Islamic doctrine of Taqiyya—the idea that deceit is a legitimate tool when dealing with infidels (that be us). Grasping the fact that our determined enemies will at times use monumental deceit to further their cause is imperative right now. Yet, too many in key positions today are willing to risk our future on better angels that simply don’t exist.

Americans need to face the fact that, as complicated as it is in a country where we believe so strongly in religious freedom and expression, Islam itself is, in many ways, our big problem.

April 16, 2013

A Terrible, Teachable Moment

[This article is at TOWNHALL.COM]

[This article is at TOWNHALL.COM]

Wherever the investigation into what happened yesterday in Boston leads, my first reactions were likely in sync with those of most Americans hearing the news. My niece was in running in the Boston Marathon this year and I immediately wanted to reach out and find out if she and her family were safe. They were. She had finished long before, in the top tier of runners.

Then I watched and listened as those moments of terror were reviewed again and again. I prayed. I posted. I tweeted.

Now, a day later, I am still praying for those who have lost life or limb. I also pray for those investigating this sordid act of anarchism. And along with the rest us, I want to know two things—who and why.

I also have this recurring thought about how human nature’s default condition is lethargy and indifference, until brutally awakened. Then, it’s only a matter of time before “normal” (whatever that is) returns, accompanied by the onset of drowsiness.

I hope it’s not too soon to say this. I do not mean to take any attention away from those who need our prayers and encouragement, but Thomas Jefferson and others long ago reminded us that, “the price of liberty is eternal vigilance.” The Apostle Peter wrote to first century Christians about being vigilant because of the perpetual and destructive activity of the devil himself. In the Greek language, the word vigilance carries the idea of “watchfulness” or “keeping awake.”

I think something C.S. Lewis said at Oxford University in the autumn of 1939, shortly after the onset of the Second World War, speaks directly on point and to our times. He shared a talk called, Learning in Wartime:

I think it important to try to see the present calamity in a true perspective. The [terrorism] creates no absolutely new situation: it simply aggravates the permanent human situation so that we can no longer ignore it. Human life has always been lived on the edge of a precipice. Human culture has always had to exist under the shadow of something infinitely more important than itself. If [people] had postponed the search for knowledge and beauty until they were secure, the search would never have begun. We are mistaken when we compare war with “normal life.” Life has never been normal. Even those periods which we think most tranquil, like the nineteenth century, turn out, on closer inspection, to be full of crises, alarms, difficulties, emergencies. Plausible reasons have never been lacking for putting off all merely cultural activities until some imminent danger has been averted or some crying injustice put right. But humanity long ago chose to neglect those plausible reasons. They wanted knowledge and beauty now, and would not wait for the suitable moment that never comes. Periclean Athens leaves us not only the Parthenon but, significantly, the Funeral Oration. The insects have “chosen” a different line: they have sought first the material welfare and security of the hive, and presumably they have their reward. [People] are different. They propound mathematical theorems in beleaguered cities, conduct metaphysical arguments in condemned cells, make jokes on scaffolds, discuss the last new poem while advancing to the walls of Quebec, and comb their hair at Thermopylae. This is not panache: it is our nature. . . .

[Terrorism] makes death real to us: and that would have been regarded as one of its blessings by most of the great Christians of the past. They thought it good for us to be always aware of our mortality. I am inclined to think they were right. All the animal life in us, all schemes of happiness that centered in this world, were always doomed to a final frustration. In ordinary times only a wise [person] can realize it. Now the stupidest of us knows. We see unmistakably the sort of universe in which we have all along been living, and must come to terms with it. If we had foolish un-Christian hopes about human culture, they are now shattered. If we thought we were building up a heaven on earth, if we looked for something that would turn the present world from a place of pilgrimage into a permanent city satisfying the soul . . . we are disillusioned, and not a moment too soon. But if we thought that for some souls, and at some times, the life of learning, humbly offered to God, was, in its own small way, one of the appointed approaches to the Divine reality and the Divine beauty which we hope to enjoy hereafter, we can think so still.

Lewis later shared similar thoughts, at the government’s request, to a national audience on the BBC.

In a time of war, you don’t make your side safe by marginalizing the conflict, minimizing the threat, or demoralizing those who are charged with crucial responsibilities.

In the century before the birth of Jesus Christ, a Syrian man named Publilius Syrus, who became popular in the days of Julius Caesar as a mime and actor, was known for his maxims and many survive to this day. Among the best is this:

“He is most free from danger, who, even when safe, is on his guard.”

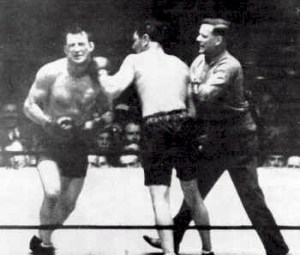

In July of 1927, Yankee Stadium in the Bronx was the scene of a boxing match between two contenders for the heavyweight title: Jack Dempsey and Jack Sharkey.

Dempsey, of course, had already been a legendary champ, only beaten the year before by savvy boxer and bookworm, Gene Tunney – the smartest guy ever to hold the title. This fight was to see who would face Tunney next. And by all accounts Sharkey took the battle to Dempsey for several rounds, cutting him up and beating him to the punch.

So Dempsey went to work on the body and some of the punches strayed low. Okay, several of the punches were south of the border. And at one point Sharkey turned to the referee to complain. At that moment, while Sharkey was looking at the official, Dempsey hit him with what he later referred to as the best punch he’d ever thrown. It was over just like that.

My point? When in a fight, protect yourself at all times.

April 8, 2013

Margaret Thatcher was also Right about Islamism

[This article is now at TOWNHALL.COM]

With the announcement out of United Kingdom today that former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher as died at the age of 87, her life, career, and words are being appropriately reviewed. This is an opportunity for some to recall her wisdom and tenacity. For others, it will just be an extended awkward moment as some try to find nice things to say about a leader whose policies and philosophy they despised. The next few days over there will be much like things were here in America in 2004, when Ronald Reagan died.

I try to watch Prime Minister’s Question Time on C-Span, when I can. This is where Great Britain’s top elected official stands in the House of Commons and wages verbal war with friend and foe alike over policies and practices. Across the pond, their big political kahuna answers to other elected officials, the way our leaders occasional face a hostile press (though mainstream media hostility toward the White House is a rarity these days). I think we might have better executive leaders, if they had to actually debate directly with congress – at least on occasion.

Margaret Thatcher was at her best when it came to those exchanges. Her last such appearance, on the day she left office in 1990, is worth watching again today.

There is much to review and laud about the Iron Lady’s life and work. Of course, her views on economics were the things for which will be most remembered. But today I am thinking of something else she said—when she had actually been out of office for more than a decade.

By then she was called Lady Thatcher, and she wrote an op-ed article that was published in the New York Times on February 11, 2002, a few months after the Sept. 11th attacks. The title of the piece was, Advice to a Superpower. She was characteristically direct describing the ideology behind the attacks and the on-going threat. Her words from that article will probably not be highlighted in the media today—likely not even mentioned. But her focus on the Islamist threat drew a clear, unmistakable warning from the past. Thatcher wrote:

Perhaps the best parallel is with early communism. Islamic extremism today, like bolshevism in the past, is an armed doctrine. It is an aggressive ideology promoted by fanatical, well-armed devotees. And, like communism, it requires an all-embracing long-term strategy to defeat it.

The Iron Lady nailed it. Though Islamism and communism as ideologies bear little resemblance to each other, beyond a mutual affinity for subduing and controlling others, they do have much in common when it comes to methodology.

Our greatest enemy is, and will be long for a long time, Islamism and its very clear agenda to subdue all who persist in the audacity of being non-Muslim infidels.

In the sixth century B.C., Sun Tzu, in Art of War, said:

So it is said that if you know your enemies and know yourself, you will fight without danger in battle. If you know only yourself, but not your opponent, you may win or lose. If you know neither yourself, nor your enemy, you will always endanger yourself.

He also said: “All warfare is based on deception.”

John J. Dziak, Ph.D., a professor at The Institute of World Politics in Washington, D.C., has written extensively on Russian Intelligence. A while back, his article, Islamism and Stratagem, appeared in The Intelligencer: Journal of U.S. Intelligence Studies (I have also been published in that journal). He drew parallels between the methods used by current day Islamists, and those used nearly 100 years ago by Lenin and company:

The Bolshevik regime was a conspiracy come to power. The Soviet Union in practice was a seventy-one-year old counterintelligence operation raised to the level of a state system. Organic to such a counterintelligence system is the widespread practice of provocations, diversion, deception, disinformation, ‘maskirovka’ (military focused deception), penetration, and other active measures of a highly aggressive nature.

He also noted that, “from its earliest history Islam has practiced what westerners label stratagem, deception, dissimulation, concealment, etc., in its dealings with not only the Infidel but with other Muslims, as well.” He identified Islamism as, “the twenty-first century heir to the counterintelligence state traditions of the totalitarian systems of the last century.”

So, Margaret Thatcher, who is being eulogized—appropriately so—today for her tireless crusade against the decadent grip of socialism, should also be remembered for her words about the greatest threat facing our nation and the world—Islamism.

April 5, 2013

Do We Really Need An Amazing Colossal Presidency?

In April of 1979, a week or so after the nuclear-near-disaster at Three Mile Island near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, Saturday Night Live did a sketch featuring Dan Aykroyd as President Jimmy Carter. Playing on the idea that Carter had a background in engineering and nuclear physics, Aykroyd insisted on visiting a place called cryptically, “Two Mile Island,” and his character was exposed to contaminated water.

Rosalyn Carter: Where is Jimmy? I have a right to see him!

Ross Denton: Mrs. Carter, the president is receiving special treatment right now.

Rosalyn Carter: What kind of special treatment? Why can’t I see him?

Ross Denton: Mrs. Carter, this is Dr. Edna Casey. Perhaps she can explain better than I what has happened to the president.

Dr. Edna Casey: Mrs. Carter, your husband was exposed to massive doses of radiation. Now this has affected the entire cell structure of his body and greatly accelerated the growth process.

Rosalyn Carter: Well, what does that mean?

Dr. Edna Casey: It means, Mrs. Carter, your husband, President Carter, has become THE AMAZING COLOSSAL PRESIDENT.

Rosalyn Carter: Well how big is he?

Dr. Edna Casey: Well Mrs. Carter, it’s difficult to comprehend just how big he is but to give you some idea, we’ve asked comedian Rodney Dangerfield to come along today to help explain it to you. Rodney?

Ross Denton: Rodney, can you please tell us, how big is the president?

Rodney Dangerfield: Oh, he’s a big guy – I’ll tell you that–he’s a big guy. I tell you he’s so big, I saw him sitting in the George Washington Bridge dangling his feet in the water! He’s a big guy!

It was a funny bit. But it’s not so funny to see life imitate art these days.

The founding fathers and framers of the constitution were very concerned about vesting too much energy in the American chief executive. In his book, The Cult Of The Presidency: America’s Dangerous Devotion To Executive Power, Gene Healy reminded us that many these days see it as “the president’s job to protect us from harm, to ‘grow the economy,’ to spread democracy and American ideals abroad, and even to heal spiritual malaise.” In fact, this job description is completely foreign to what was created back in the day. “If the public expects the president to deal with all national problems, physical or spiritual,” he writes, “then the president will seek – or seize – the power necessary to handle that responsibility.”

In other words, an amazing colossal presidency—the kind we are witnessing right now as described in Healy’s latest offering, a sequel of sorts: False Idol: Barack Obama and the Continuing Cult of the Presidency.

So, how did we go from what the constitution meant to where we are now? The trouble began around the turn of the 20th century and the Progressive movement. And it was very much an equal opportunity problem – with Democrats and Republicans to blame.

A careful look at the presidencies of Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson yields abundant clues about how we got here. TR was a Republican and a strenuous occupant of the White House – and in many ways, admirably so. He is seen by many today as a hero, though it is likely that his personal qualities inspire people more than his actual policies or approach to the presidency itself. He was a man of courage and confidence. His post-presidential speech at the Sorbonne in 1910 about Citizenship in a Republic, complete with its famous “Man In The Arena” characterization, was one of the great orations of the 20th century.

Mr. Roosevelt, however – all his wonderful traits notwithstanding – dramatically expanded the role of the presidency and with it the expectations of Americans. Then later, Woodrow Wilson picked up where Teddy left off and transformed the office into one that became, in fact, an amazing colossal presidency. And it wasn’t a good thing.

Still isn’t.

The day after his election in November of 1912, Wilson told his party chairman: “Before we proceed, I want it understood that I owe you nothing. Remember that God ordained that I should be the next President of the United States.” I think he may have showered in contaminated water that very morning. He was, after all, from New Jersey.

Wilson had written a book back in 1908 entitled Constitutional Government. In it, he talked about his views of the presidency: “The President is at liberty, both in law, and conscience, to be as big a man as he can.” His administration was living proof of this. This so-called “Progressive” man was a civil liberties wrecking crew, though revered by most Democrats today as a hero – even a saint. The nation under Wilson, and at the end of The Great War, was as close to totalitarianism as it had ever been. An editorial in The New Republic on November 16, 1918, gives a snapshot of what the country looked like, and this periodical clearly saw all of it as great:

The whole issue hinges on social control. For forty years we have been widening the sphere of this control, subordinating the individual to the group and the group to society. Without such control, vastly magnified, we should not have been able to carry on the war. We conscripted lives, property, and services; we took over railroads, telegraphs and other economic instruments. We fixed wages, prices, the quantity of coal, power, labor or transportation a man might command, and the quantity of food we might consume. All this we did on the narrowest of legal bases, for no one dared question our power.

In other words, it did happen here – thanks to an amazing colossal presidency.

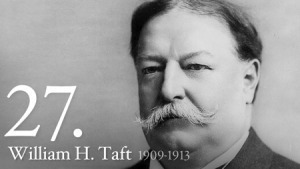

In between Teddy and Woody came William Howard Taft. Now largely dismissed by historians as a presidential failure, what it is missed is how much of a voice of reason he was. Roosevelt’s handpicked successor ratified by the voters in 1908, Taft and TR eventually had a falling out and conducted a party-dividing battle for the 1912 Republican nomination. Taft won that race, but Teddy decided to run as a third-party candidate that November, effectively conceding the overall election to Mr. Wilson.

It was humiliating for Taft and while in the political wilderness he wrote a largely forgotten, but very insightful, book about the presidency entitled, Our Chief Magistrate and His Powers. What he had to say back then needs to be read, and read again by Americans today, in this new age of the amazing colossal presidency:

Ascribing an undefined residuum of power to the President is an unsafe doctrine and…it might lead under emergencies to results of an arbitrary character, doing irremediable injustice to private right. The mainspring of such a view is that the executive is charged with responsibility for the welfare of all the people in a general way, that he is to play the part of a universal Providence and set all things right, and that anything that in his judgment will help the people he ought to do, unless he is expressly forbidden not to do it. The wide field of action that this would give to the executive, one can hardly limit.

Warren Harding appointed William Howard Taft as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court in 1921, the only job he ever really wanted. Harding also undid much of the damage Mr. Wilson had done to the economy, not to mention liberty itself.

Sure, Harding had his share of personal problems—mostly having to do with the “friends” surrounding him. And Taft was not too great on the campaign trail or before the camera. But compared to some of the amazing colossal presidents we have had, I think the men who served before and after Wilson look better than him, and even in some ways, though it’s hard to admit, than the man who talked about being in the arena.

April 4, 2013

Forty-Five Years After His Tragic Death, A Look Back at Dr. King, the Preacher

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who was assassinated 45 years ago today in Memphis, Tennessee, was a great man on so many levels. But he was first and foremost a pastor/preacher, erudite and eloquent – persuasive and passionate. A while back, I revisited some of his last sermons and speeches, wondering how they’d play in today’s cultural and political climate.

Of course, such a translation of any discourse from one era to another is potentially problematic, running the risk of ignoring the context of the remarks and the idiosyncrasies of the moment. Dr. King could be a controversialist when it came to saying provocative things from the podium or pulpit.

A year to the day before his tragic death, Dr. King occupied the pulpit of Riverside Church in Manhattan. The church, built against the backdrop of the Fundamentalist-Modernist controversy of the 1920s, was founded by Harry Emerson Fosdick and John D. Rockefeller Jr., a liberal preacher with a generous benefactor. Mr. Rockefeller initially donated more than $10.5 million and his contribution grew to more than $32 million by 1959. It was a case of petrodollars funding Protestant liberalism.

As Dr. King spoke to a crowd of nearly 4,000 on April 4, 1967, he said that as a religious leader he wanted to “move beyond the prophesying of smooth patriotism to the high ground of a firm dissent.”

His subject was not Civil Rights – it was the Vietnam War.

Though careful to talk about America as his “beloved nation,” and not at all hesitant to address the crowd as “my fellow Americans,” he said that “the greatest purveyor of violence in the world” was “my own government.”

At that time, polls indicated that nearly 75% of Americans supported the war.

Dr. King faced his own media firestorm in the immediate aftermath of his “Beyond Vietnam” speech. The Washington Post described it as “unsupported fantasy,” and the New York Times called it “Dr. King’s Error.” U.S. News and World Report went even further suggesting that King was “lining up with Hanoi” and President Johnson angrily speculated that King had “thrown in with the Commies.”

Even legendary baseball player/hero Jackie Robinson came out against the speech and the NAACP adopted a resolution warning that King’s effort to connect the anti-war movement with civil rights was a “serious tactical mistake.”

Later that year, the annual Gallup Poll of the Ten Most Popular Americans would not include the name of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.—for the first time in more than a decade.

One long and very difficult year after his Riverside remarks, Dr. King was in Memphis. And the night before his death he was scheduled to speak at Mason Temple. There were storm and tornado warnings and he was weary from travel, so he asked Rev. Ralph Abernathy to go in his place. When Abernathy got to the church, he saw thousands who had braved violent weather to hear King, so he called back to the Lorraine Motel and encouraged his friend to come over. King did and he gave what was to be his last sermon.

During his 20-minute extemporaneous address that evening he asked: “Who is it that is supposed to articulate the longings and aspirations of the people more than the preacher?” He then added a word of encouragement to the great number of preachers in the crowd: “I want to commend the preachers…and I want you to thank them, because so often, preachers aren’t concerned about anything but themselves. And I’m always happy to see a relevant ministry.” As he warmed to the crowd and his message he said: “We don’t have to argue with anybody. We don’t have to curse and go around acting bad with our words.”

He called for the development of what he referred to as “a kind of dangerous unselfishness,” and segued to a rhetorical comfort zone, the biblical story of the Good Samaritan. He used the famous story as the basis for his admonition: “Let us rise up tonight with a greater readiness. Let us stand with greater determination…we have an opportunity to make America a better nation.”

Then he waxed personal and described a previous assassination attempt by “a demented black woman” ten years before and how the blade came so close to his aorta that one sneeze would have ended his life. This was a familiar King story, one that he told many times with the refrain “If I had sneezed…” being repeated again and again for effect. At this point, other preachers on the platform that night became unsettled because this story was usually one placed earlier in a speech. The concern was that Dr. King might “miss his landing” and not end on a high note.

There is an old formula in the African-American tradition of preaching: “Start low, go slow. Rise higher, catch fire. Retire.” The concern was that King was not quite catching fire. Then, however, came those final moments as he talked about being to the mountain top and seeing the“promised land” and the now famous and passionate ending:

So, I’m happy tonight! I’m not worried about anything! I’m not fearing any man! Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord!

As a preacher King was Sunday-centric, always with an eye on the next sermon. So the next afternoon, Thursday, April 4, 1968, he placed a call from room 306 of the Lorraine Motel back to Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta and gave his secretary the title for his upcoming Palm Sunday sermon: “Why America May Go to Hell.”

He never had the chance to preach that one. A few hours later his voice was silenced in a brief and deadly explosion of violence.

Dr. King is remembered 45 years later for his words and deeds. He is honored –appropriately so—as a hero. It is, though, an interesting question: “What would Dr. King say today – and how would he be received?”

Hitler’s Favorite Islamist

As members of the Allied Expeditionary Force entered the landing crafts that would transport them to their rendezvous with history in the early morning hours of June 6, 1944, they received individual copies of the Order of the Day drafted by their Supreme Commander, Dwight D. Eisenhower. He had given the go ahead for the massive invasion, code named Overlord, in spite of weather that was less than inviting. He wanted the men to understand what they were fighting for – and against.

He told them:

You are about to embark upon the Great Crusade, toward which we have striven these many months. The eyes of the world are upon you. The hopes and prayers of liberty-loving people everywhere march with you. In company with our brave Allies and brothers-in-arms on other fronts, you will bring about the destruction of the German war machine, the elimination of Nazi tyranny over the oppressed peoples of Europe, and security for ourselves in a free world.

In those days leaders weren’t as concerned about the politically correct parsing of phrases and words as some seem to be today. It was clear to them that they were not fighting mere “flesh and blood” but abhorrent ideological wickedness (“Nazi tyranny”). And they passed that clarity onto those who were engaged in the perilous fight.

So, why is it so hard for some today to call things as they are?

We are not fighting a war on terror. We are fighting against a pernicious way of thinking. Terrorism is a methodology – a way to fight a battle. The technique itself is not the enemy. Our foes are people and regimes that, in the name of foul opinion, perpetrate destruction. Just like back in the 1940s.

Can you imagine what it would have sounded like if Ike, FDR, or Churchill had been bound by the sensitivities of our day? We would have been “battling the blitzkriegers,” or maybe “bringing to justice those who dared to attack too early on a Sunday morning,”—hardly clarion calls.

Wars make more sense, and they tend to be conducted with greater vigilance and effectiveness, when we understand things in terms of good vs. evil. But these days, it’s hard to even bring up the idea that Islamism is to blame, much less to frame the current conflict as a war against it. However, history leaves clues that remind us that there is really not much new under the sun.

David G. Dalin and John F. Rothman wrote a book a few years ago, one that should be read by all Americans seeking to understand current geopolitical reality. It was titled, Icon of Evil: Hitler’s Mufti and the Rise of Radical Islam. They made a compelling and well-documented case that we are actually fighting the quasi-spiritual offspring of Nazism and Fascism.

Haj Amin al-Husseini (1895-1974) is by no means a household name today, but his story is a key historical plot-point helping to create the mess we now find ourselves in. From his appearance on the stage of turbulent Middle Eastern politics in 1921, until his death fifty-three years later, he was a consistent and vociferous voice preaching a blend of anti-Semitic, anti-Western, and pan-Islamic rhetoric to anyone who would lend an ear. And there were plenty of listeners. There still are. He was the grand mufti (maximum leader) of all Muslims in Palestine – the big kahuna.

Mr. al-Husseini’s political journey was driven by a radical interpretation and application of Islam. He was an effective and charismatic leader of a vast movement—the forerunner of the various manifestations of Islamic fanaticism extant. This virulent form of his religion took hold during the period between the two world wars and grew to become the plague it now is on all houses of freedom.

And it turns out that al-Husseini was a big fan of a man by the name of Adolf Hitler. And the number one Nazi liked him, too.

In November of 1941, there was a meeting in Berlin, one that is often relegated to a footnote in the history of that great global conflict. Haj Amin al-Husseini made his way, from the mansion he’d been provided by the Nazis, toward the Reich Chancellery. There he met Hitler in the dictator’s private office. Dalin and Rothman describe this ominous meeting in great detail. It’s a fascinating story. The mufti sought to ingratiate himself with Hitler and the strategy was reciprocal. They pledged allegiance to each other.

And why not? They had common goals and enemies. The German leader bestowed honorary Aryan citizenship on his guest and it was clear that his visitor was keenly interested in being set up as the Nazi leader in Palestine and its surrounding region. Al-Husseini eventually recruited 100,000 European Muslims to partner with the Waffen-SS, and the authors of Icon of Evil hinted at the idea that the cleric-politician was influential in the decision to implement the notorious Final Solution. He was even pretty good friends with Heinrich Himmler and Adolf Eichman.

Nazis and radical Islamists – together. Nothing good could come of that. In fact, a good case can be made that many of the horrific things we have seen in the past 20 years were incubated in that Berlin laboratory.

One of the most captivating portions of Icon of Evil was devoted to the question: What if Hitler had been victorious and the war had turned out differently? Drawing on similar previous musings by writers such as William L. Shirer, John Keegan, and David Fromkin, the duo shared a chilling narrative about how radically different life would be today had Hitler won. This is important not just because of the horrifying idea of a Hitler-dominant Europe – but also due to what the Middle East would look like in such a case.

Al Husseini wanted to extend the Holocaust beyond the borders of European living space to the Middle East. His goal was something near and dear to the heart of the depraved men running the Third Reich – a Palestine that would be virtually Judenrein (a reprehensible Nazi term literally meaning: “clean of Jews”).

Then there’s the story of how this wicked preacher was able to avoid the Nuremberg trial dragnet, in spite of clearly being guilty of egregious war crimes. He would not be brought to justice, but rather would live out his days back in the Middle East. His post-war work included becoming something of a mentor to men who would become famous in his cause.

What do Gamel Abdel Nassar, Anwar Al Sadat, Yassir Arafat, and Saddam Hussein have in common? They were all connected with, and deeply influenced by, Haj Amin al-Husseini. Hamas and Hezbollah are very much part of his legacy, as well. He worked closely with the theoretician of radical Islam, Sayyid Qutb, as well as Saddam’s infamous uncle, General Khairallah Talfah. The guy was connected. And the usual suspects he ran with paved the way for everything from the attacks on September 11, 2001, to the maniacal rhetoric of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

In fact, some of Haj Amin al-Husseini’s spirit is in the intellectual and emotional DNA of every current radical Islamist.

Now, here’s what really bugs me – why could we fight a war seventy years ago, all the while referring to our enemies as Nazi thugs, and yet today be so concerned about sensibilities that we’re reduced to, at best, rhetorical beating-around-the-bush?

The war we are in is not against a weapon, no matter how dreadful that weapon is. We are fighting a virulent ideology. To be brutally honest about it—to call our enemies today terrorists, or even Islamo-Fascists, is not strong enough.

They are Islamo-Nazis and they’re really bad people—like the German-Nazis were.

April 2, 2013

Which Revolution?

In my opinion, the best part of John F. Kennedy’s inaugural address on January 20, 1961, had nothing to do with asking anyone anything. The moment to remember was when he said:

The world is very different now. For man holds in his mortal hands the power to abolish all forms of human poverty and all forms of human life. And yet the same revolutionary beliefs for which our forebears fought are still at issue around the globe – the belief that the rights of man come not from the generosity of the state, but from the hand of God. We dare not forget today that we are the heirs of that first revolution.

It is interesting, even sadly ironic, that what is going on in our nation right now does resemble an old revolutionary spirit, but not necessarily that of Lexington, Concord, or Philadelphia. In fact, a case can be made – if one looks closely – that the spirit of 2013 is more like the spirit of 1789 than 1776.

The American and French Revolutions are linked in our minds because of chronology; but they were vastly different affairs. One led to a new birth of freedom; the other to terror and tyranny. That one also became the portal and model for horrors to come.

As our nation morphs its way along, en route to becoming what some liberal diehards very much want it to be, a significant number of people would seemingly prefer “Liberty – Equality – Fraternity” over “Life – Liberty – and the Pursuit of Happiness.”

It is in the parsing of those vitally important words that we find the keys to understanding where we came from, where we are, and where we are going. One revolution was about individual rights and dreams. The other was about “the people” as a group and the highest virtue being “the greater good.”

Can you guess which is which?

When Thomas Jefferson wrote about “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” in the Declaration of Independence, he was borrowing from 17th century English philosopher, John Locke, whose triad was “life, liberty, and the pursuit of property.” Jefferson’s use of this language was clearly designed to describe the rights of individual people to live free, be free, and freely pursue their dreams in a free marketplace. Those thoughts were very much in presence in that Philadelphia birthing room.

The French Revolution, on the other hand – though similar to what happened here in the sense of changing things and breaking free from an old order – had little to do with individual rights. It was all about collectivism. And in many ways, the French Revolution is the ancestor of all totalitarian systems to follow. Hitler, Mussolini, Pol Pot Lenin, and all other political gangsters were heirs of Robespierre and later, Napoleon. Those tyrannical manifestations were not misguided aberrations – distortions of something that started out good (as in, “Lenin was cool, but that Stalin guy, he was messed up!”) – the seeds of the horror were present at the beginning.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, 18th century Enlightenment philosopher, had written about volonté générale or “general will” and the Jacobins, followed by others, ran with it insisting that voice of “the people” could best, actually only, be expressed by so-called “enlightened” leaders.

Our revolution indeed drew a measure of strength from the Enlightenment, but it was of the earlier Locke variety. And America’s use of Enlightenment concepts was tempered by something else; something that set it apart from what happened in France—a spiritual foundation.

Vive la revolution — Vive la difference.

The French not only declared war on the monarchy, they also attacked Christianity, replacing it with a religion of the state, introducing the worship of secularism. Sound familiar?

In America, it was very different. Now, I am not one of those who spends a lot of time trying to prove the Christian bona fides of our founding fathers, but I do believe that the influence of The Great Awakening, which ended about 20 years before the shot heard around the world was fired, was still very much a part of our national fabric at the time.

And another such movement, often referred to as The Second Great Awakening began while the French were unsuccessfully trying to figure out how to be free. To ignore those religious and cultural movements in America is to miss an important piece of the puzzle.

The very concepts of liberty, equality, and fraternity sound nice and make for great propaganda. But in the end, without virtue born of something deeper and greater, it all ends up looking the same. This is why all totalitarian regimes like to call their realms The Peoples’ this or that – like The Peoples Republic of China, or Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, or The Peoples Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

We need to beware of those who share our vocabulary, but use a different dictionary. Are we still about the individual, personal, hard-fought-for rights: Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness, or does the cry: Liberty, Equality, Fraternity seem to increasingly be the spirit of this age?

The reason it has all worked and endured so well in this land is because we are a nation “under God.” There I said it. There is no real liberty without that. All attempts at actual freedom end up moving toward tyranny without some sense of higher purpose and power. I believe firmly in the separation of church and state. But minus positive religious influence, a nation cannot long remain free.

Thomas Paine’s story should be a cautionary tale. He, of course, wrote Common Sense in early 1776, and it was by all accounts vital to shaping public opinion in support of our patriotic ancestors. He was a revolutionary. Mr. Paine helped us early on, but as he moved on and shared more of his thinking via his acerbic pen, he expressed ideas that, while probably resonating with some today, would in no way mesh with the spirit of 1776.

While Common Sense supported the ideas of freedom, small government, and even low taxes – all very much part of that old revolutionary spirit – by the time the French were acting out, his writings became increasingly more radical. When parts one and two of his work, The Rights of Man, appeared in 1791 and 1792, he became a pariah in England and fled to France like where he was treated like a hero, being made an honorary citizen of the republic. But by this time, his writings advocated a progressive income tax, public works for the unemployed, and guaranteed minimum incomes.

And don’t even get me started on his next bestseller, The Age Of Reason; a rant against revealed religion. Paine died virtually alone and penniless in 1809. Only six people attended his funeral.

This of course, brings us back full circle to the thesis of this article – that concepts of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, expressed individually (the intent of our founders), can only keep from drifting toward collectivism when there is a spiritual impulse – or at least a spiritual pulse.

C. S. Lewis said it very well in The Screwtape Letters 70 years ago:

Hidden in the heart of this striving for Liberty there was also a deep hatred of personal freedom. That invaluable man Rousseau first revealed it. In his perfect democracy, only the state religion is permitted, slavery is restored, and the individual is told that he has really willed (though he didn’t know it) whatever the Government tells him to do. From that starting point, via Hegel (another indispensable propagandist on our side), we easily contrived both the Nazi and the Communist state. Even in England we were pretty successful. I heard the other day that in that country a man could not, without a permit, cut down his own tree with his own axe, make it into planks with his own saw, and use the planks to build a tool shed in his own garden.