David R. Stokes's Blog, page 7

November 23, 2013

Thank You, Mr. Schieffer

The Fort Worth Star Telegram issued four “Extras” on November 22, 1963, the day President John F. Kennedy died. The driving force was a 26 year-old cub reporter by the name of Bob Schieffer.

[I am personally grateful to Mr. Schieffer for another reason—but I’ll get to that in a bit.]

[I am personally grateful to Mr. Schieffer for another reason—but I’ll get to that in a bit.]

Bob Schieffer happened to answer the phone in the busy Star-Telegram newsroom about an hour after the news broke about the assassination. The caller—a woman—asked if anyone at the paper could give her a ride to Dallas. The young reporter was about to hang up, telling the caller that the newspaper wasn’t a taxi service, when the woman said that she was the mother of the man who had just been arrested in Dallas.

Bob Schieffer drove over to the home of Marguerite Oswald—mother of Lee Harvey Oswald—and gave her that ride to Dallas. Over the next few hours he was with her and able to phone in regular updates to his paper from the Dallas Police Station.

It was what they call a big scoop for the young reporter.

These days, Mr. Schieffer is one of the elder statesmen of the news business, close CBS heir to Murrow and Cronkite. Recently, his alma mater, Texas Christian University, in his beloved hometown of Fort Worth, Texas, renamed their excellent journalism school after him.

It was that love of Fort Worth that led Bob Schieffer to take an interest in a book I was writing a few years ago. It was about that town and one of its more “colorful” citizens—a famous preacher. And I’m deeply grateful to Mr. Schieffer for agreeing to write the Foreword to that book, The Shooting Salvationist: J. Frank Norris and the Murder Trial that Captivated America.

Here’s part of what he said about the book:

Here’s part of what he said about the book:

“For all the colorful characters who became part of Fort Worth’s history, surely none surpassed J. Frank Norris, the fiery fundamentalist preacher at Fort Worth’s First Baptist Church in pure outlandishness. His oratory and penchant for publicity brought thousands into his congregation and at one point First Baptist was among the largest churches in the world, a mega church before the phrase was coined. Unfortunately, for all his oratorical skills, Norris’ horizons were limited by several criminal indictments brought on by his tendency for violence.

In this book David Stokes tells the J. Frank Norris story.

If I hadn’t grown up in Fort Worth, I would have thought someone made all this up but no one did.

It really happened.”

Thank you, Bob Schieffer!

November 21, 2013

How Kennedy Became CAMELOT

Vinny is one of my grandsons (I have six, and one granddaughter—thanks for asking). He’s seven years old. The other day, as he showed me a screen and explained the latest level he’d reached in a game I didn’t know or understand, I was struck by the thought that I was exactly his age when my second grade teacher, who for some reason had left a classroom full of, well, second-graders, reentered the room. She was weeping. She wrote on the chalkboard: “President Kennedy has been shot.”

Then she left the room—again.

A few minutes later, right about the time I had my friend Tim in a chokehold (or was it the other way around?), she came back and went to the chalk, once again, writing: “President Kennedy is dead. You are dismissed. Go straight home.”

So we did. These were the days before carpools and long lines in front of schools where parents waited. We just walked home. Hundreds of kids poured out onto the sidewalks, with little security, but for a few fellow students wearing special belts around their waist and over one shoulder. They were the “safety patrol.” Becoming a member of that elite “special forces” group was an early ambition of mine, but I digress.

So we did. These were the days before carpools and long lines in front of schools where parents waited. We just walked home. Hundreds of kids poured out onto the sidewalks, with little security, but for a few fellow students wearing special belts around their waist and over one shoulder. They were the “safety patrol.” Becoming a member of that elite “special forces” group was an early ambition of mine, but I digress.

I remember walking home briskly, so that I could tell my mom what had happened. But she already knew. Everyone did.

Now, my folks weren’t Kennedy supporters—they voted for Nixon, and later Goldwater, and then Nixon, again. However, my mother always had the latest magazine lying around featuring the young First Lady on the cover. It’s hard to believe now, but Jackie was only 34 years old when her husband was taken from her, and us.

Over the past 50 years, since that fateful day in Dallas, the Kennedy story has been told, and retold. The thousand days of his presidency are often referred to as “Camelot,” a name pregnant with a sense of wonder and magic. In fact, the nomenclature is used so often, that there are some who may assume that was the way people referred to JFK’s White House when he lived and worked there.

Actually, the Camelot image began to be associated with all things JFK when Jackie Kennedy met with a famous writer after her husband’s murder. His name was Theodore H. White.

The day after Thanksgiving in 1963, and one week to the day from the assassination, Mrs. Kennedy had a late evening meeting with Mr. White at the Kennedy home in Hyannisport, Massachusetts. She had made it clear to the editors of Life Magazine that she preferred White write the primary essay in the special issue they were getting ready to publish. He had covered their wedding for the magazine in 1953, and more recently, he had written sympathetically about Kennedy in his Pulitzer Prize-winning book, The Making of the President, 1960.

During their conversation that night, the President’s widow, talked about how much her late husband had enjoyed the Broadway play, Camelot—particularly its music. He regularly played the original soundtrack record in the White House, usually before they drifted off to sleep.

Don’t let it be forgot,

That once there was a spot,

For one brief, shining moment

That was known as Camelot

White was on deadline. They were actually holding up publication of the magazine, at a cost of $30,000, and waiting for his copy. So after his conversation with Mrs. Kennedy, he went to another room and spent 45 minutes composing the essay. Then he went to a telephone in the kitchen to dictate the story to an editor.

Jackie Kennedy came in as White was debating back and forth with the editor about toning down the whole “Camelot” angle. She gave White an angry look, while shaking her head emphatically—“No.”

And the rest is, as they say, history.

[This article was written for VENTURE GALLERIES--an excellent site for readers and writers. - DRS]

October 21, 2013

The Forgotten Mickey of ’68

Though this time of year the big-four of sports are all up and running—baseball, football, basketball, and hockey—to my mind it’s still baseball season until Yogi Berra’s famous benediction is pronounced: “It ‘aint over ‘til it’s over.” The man was a wordsmith.

This year, I find myself thinking a lot about what was going on 45 years ago—in 1968. It was time of conflict, assassination, national division, international disorder, and cultural explosion.

But I remember it also as a great year for baseball. It was the last year before divisional play began to fill October wall-to-wall. Back then, there were just two leagues—American and National. No divisions. So October baseball competed with Sunday football for barely one weekend.

It was also the year of Mickey.

There was Mickey Mantle, who was retiring at the end of the season after a certain-to-make Hall of Fame career. His last visit to league stadiums became a farewell tour of sorts. I saw him play his last game at Tiger Stadium in Detroit near where I grew up. And when he came to bat for the final time, I saw pitcher Denny McLain throw him a fat pitch designed to let Mickey hit it into the right field stands. When The Mick rounded second base on his final home run trot in Detroit, he tipped his hat to McLain.

It was very cool.

Of course, being a life-long Tiger fan, the mention of the name Mickey immediately brings to mind a guy named Mickey Lolich, a journeyman left-hander who found the ultimate groove that October. He had long pitched in the shadow of teammate McLain, who won 31 games that year (the last man to win 30). But the locals knew he had the stuff. And in the World Series against the St. Louis Cardinals, he pitched game seven on just two days rest and went the distance (that’s nine full innings—there’s no law against this) to lead the Tigers to the World Championship. This was long before baseball discovered “closers,” “middle-relievers,” and “pitch counts.”

But there was another Mickey that year—and he’s one of baseball’s forgotten heroes. His name—and you may have to scratch your head to remember—was Mickey Stanley. He was a gold-glove centerfielder, and a pretty fair hitter.

As the Tigers coasted toward the series that year, manager Mayo Smith knew he had a problem. You see, he had four great outfielders and only three positions: Mickey Stanley, Jim Northrup, Willie Horton, and another man destined for the Hall of Fame on the first ballot. His name was Al Kaline, one of the greatest all-around players ever. He came straight to Detroit from High School in 1953, and never spent a day in the minor leagues. In 1955, he became the youngest player ever to lead the league in batting, with a .340 average.

As the Tigers coasted toward the series that year, manager Mayo Smith knew he had a problem. You see, he had four great outfielders and only three positions: Mickey Stanley, Jim Northrup, Willie Horton, and another man destined for the Hall of Fame on the first ballot. His name was Al Kaline, one of the greatest all-around players ever. He came straight to Detroit from High School in 1953, and never spent a day in the minor leagues. In 1955, he became the youngest player ever to lead the league in batting, with a .340 average.

He broke his hand ’68 and missed many games. The outfield performed well in his absence, but Manager Smith knew that this might be Kaline’s only shot at playing in a World Series. So he conceived a gutsy plan.

Ray Oiler was the Tiger shortstop. The guy was amazing with the glove, but couldn’t hit a lick. I mean the guy could strike out in Tee-Ball. So Smith talked to Mickey Stanley and asked him if he’d ever played shortstop. He hadn’t. The two positions were very different.

Nevertheless, Mickey Stanley was moved from outfield to infield just for the World Series. This made room for Kaline in the lineup (this was also long before things like the “designated hitter” and “”Money Ball”). By all accounts, Stanley accepted the role without complaint, demonstrating what it meant to be a team member. He played flawlessly—not a misstep or error.

It was a great example to young ball players, who for many years heard Little League coaches bark: “What do you mean you don’t want to play where I need you? Did Mickey Stanley complain when he was put at shortstop?” Coaches loved Mickey Stanley.

Not long after the ’68 season, baseball began to change. Free agency came, along with more money, money, money. Players moved around a lot more. They started building stadiums where you could actually see the game from any seat (go figure).

I still love baseball. But I wonder if the spirit of Mickey Stanley is anywhere to be found? Not only in baseball—but in America, in general?

[This article was written for VENTURE GALLERIES - DRS]

October 3, 2013

SAVING REAGAN

[This column was written for TOWNHALL.COM -- DRS]

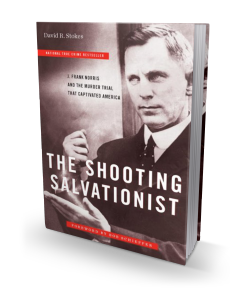

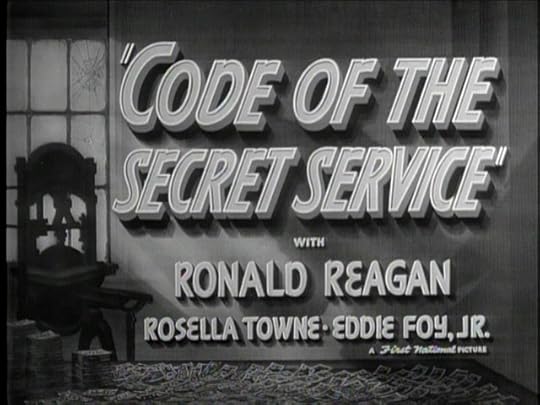

Hollywood put out some great movies in 1939, films such as Gone With the Wind, The Wizard of Oz, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, and The Hunchback of Notre Dame. But one movie that year—now largely forgotten—served a purpose even greater than helping a Depression-ravaged American public forget their dire straits, not to mention the storm clouds gathering around the world. It was called, Code of the Secret Service, and it starred a handsome young actor named Ronald Reagan.

Jerry Parr was nine years old the day his dad took him to a Miami theater to see Reagan play a G-Man named Brass Bancroft. Nearly forty-two years later, Jerry Parr was the Agent in Charge of the detail protecting that once-young actor who became the President of the United States.

Jerry Parr was nine years old the day his dad took him to a Miami theater to see Reagan play a G-Man named Brass Bancroft. Nearly forty-two years later, Jerry Parr was the Agent in Charge of the detail protecting that once-young actor who became the President of the United States.

And on March 30, 1981, Parr’s quick thinking and reflexes became part of history as he pushed President Reagan into a limousine when gunfire erupted outside the Washington Hilton Hotel following a speech to a labor group. There is an iconic photo of the moment capturing the intense grimace on Parr’s face as he forcefully protected his charge.

Jerry Parr, and his wife Carolyn, a retired judge from the U.S. Tax Court, have written a new book, a moving memoir of that fateful day and of Jerry’s life and career. It’s called, In the Secret Service: The True Story of the Man Who Saved President Reagan’s Life.

Parr, who retired from the United States Secret Service in 1985, shares a moment by moment recap of what happened on that sidewalk and in the limousine, including his decision to change course and head to the hospital instead of back to the White House. Mr. Reagan mentioned to Parr, “I think you broke my rib.” And while the agent pondered the prospect of having so wounded the president he noticed Reagan wiping some blood from his lips. “I must have cut the inside of my mouth.” But Parr saw that the blood was “frothy” and instantly realized that as a sign of a lung injury. Next stop GW Hospital. It was a decision that saved Reagan’s life.

Jerry Parr’s career in the USSS began a little more than a year before another president was shot—that one in Dallas, Texas, and with no happy ending. Parr was in Tennessee at the moment of the shooting, but made his way to Dallas a few days later to conduct numerous interviews, including many members of Lee Harvey Oswald’s family.

The book is filled with interesting stories about the Johnson, Nixon, Ford, and Carter years, as well as the Reagan tenure. But there are no salacious tidbits of gossip—the stuff of tell-all books written by purveyors of innuendo and helped along by a few disreputable miscreants who sell their souls and betray vital trusts for selfish reasons. In the Secret Service is a reminder that there are some—many, many—dedicated public servants who do their jobs because they have integrity and a sense of mission above and beyond themselves.

Parr was uniquely positioned to observe the impact of the shooting on Ronald Reagan, particularly his faith that God had spared him for a purpose. Reagan was comfortable talking about spiritual things because they were, indeed, very real to him. In fact, the book is really a story of God’s grace—in Reagan’s life, and the lives of Jerry and Carolyn Parr. It is also a story of finding and doing God’s will.

After the events of March 30, 1981 were long in the rear view mirror, and Mr. Reagan had fully recovered, Jerry Parr asked him, “Did you know you were an agent of your own destiny?” He told the president about the visit to that Florida movie house back in 1939, and how he saw the film many, many times thereafter. It inspired a little boy to become an agent like Brass Bancroft. Reagan smiled and in a typical use of humor replied: “It was one of the cheapest films I ever made.”

It was also—in a very real sense—the most important one he ever made. Nancy Reagan said, “Jerry put himself in harm’s way to protect Ronnie, and I am forever grateful.”

So are we.

[Watch a trailer of CODE OF THE SECRET SERVICE with Ronald Reagan HERE]

September 23, 2013

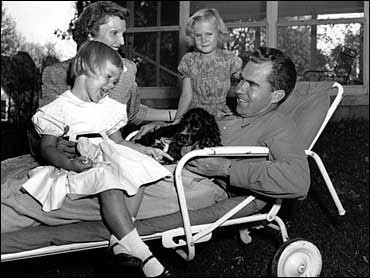

The Checkers Speech — 61 Years Ago Today

One day in 1974, as Spring began to give way to Summer, Frank Gannon—wordsmith and White House Fellow—took a walk in Washington, largely to get away from the stress induced by the Nixon White House’s ever-increasing Watergate milieu. He found his way to an old theater—one that happened to be featuring a triple billing of anti-Nixon films. He felt uncomfortable—even somewhat guilty—for being there, but for whatever reason even this was a welcome break from what was happening a few blocks away. He looked around and, though the lights were out, sensed the crowd’s unmistakable derision every time Richard Nixon’s familiar image appeared on the screen.

Then something curious happened.

The final feature of the odd cinematic trilogy was the simple replaying of a speech Mr. Nixon had given more than two decades earlier—on September 23, 1952—at another embattled moment in his career. The grainy video was designed to be the program’s pièce de résistance. But as a much younger Richard Nixon delivered his remarks on the screen that day, it was the audience that Gannon noticed. For whatever reason, the sarcastic hisses had stopped as Nixon spoke of finances and family and a dog named Checkers. It was almost as if these decidedly anti-Nixon partisans were suddenly fascinated.

He was 39-years old and on the verge of national leadership—the junior United States Senator from California and the Republican nominee for Vice President. He was living the American dream and fulfilling many of his own. And along the way, he carried the hopes of a new generation of Americans, those who had emerged from the darkness of global conflict with renewed resolve to embrace life and ensure that such a catastrophe never happened again.

In fact, this rising political star whose magnitude had increased so dramatically in six short years, had already experienced the clash of personalities and ideologies that was to define his generation. Richard Milhous Nixon would be a transcendent political figure in America for quite some time. His name would appear on five national ballots—a feat equaled only by Franklin Delano Roosevelt—two times for Vice-President and three for President. And like FDR, he would lose only once, and that barely to another young politician, this one from Massachusetts, who was making his own history in 1952.

Mr. Nixon is most often remembered through the prism of how his career—at least the public part—ended in August of 1974. This is not only unfortunate, but it also prevents us from figuring out how this man who fathomed such deep valleys managed to actually scale the highest political mountains extant. How could Nixon have done all he did if the caricature of him in the minds of so many Americans was an accurate characterization?

Understanding what he did in 1952 is crucial to processing all the rest. What is lost to so many in the fog of all that later transpired, is that Richard Nixon was actually right on the facts, as well as the politics, in 1952. He did not wiggle out of a mess. In fact, he demonstrated a clear capacity for communication and connection with the American people.

It was the dawn of the television age—the beginning of an entertainment, information, and communication seismic shift. In living rooms around the country, the large radio, complete with it’s prominently displayed dials, would be exiled to elsewhere in the house and the furniture would begin to arrange itself around the new media kid in town. The device that Edward R. Murrow would later characterize as “lights and wires in a box,” would eventually become so essential to Americans that they wondered how they ever lived without it. Although, until that September night when Richard Nixon spoke “coast to coast,” the shift from wireless to tube was anything but a done deal. And as the young politico prepared to make his case to the American people, he had no way of knowing that not only what he had to say would be important, but where he said it would be, as well—even more so.

It was the first synchronization of medium and message for a new age. This was the moment when television began to trump radio—even motion pictures—as the entertainment choice du jour of Americans. We loved Lucy, watched “Uncle Miltie,” and got our information more and more as much from Edward R. Murrow as from the venerable morning and evening newspapers.

In fact, in many ways it was the Checkers speech that signaled the beginning of our ever since fascination with the glowing tube. More Americans watched Nixon that September night than would watch any single event on T.V. for many years to come. But even politicians were slow to figure out what it all meant. The Republican National Committee put their Vice Presidential candidate on two radio networks (Mutual and Columbia; MBS, CBS), while on only one television hook-up (NBC). But, no matter—suspense built, and by airtime at 9:30 p.m. (eastern) on Tuesday, September 23, 1952 nearly 60 million viewers tuned in—an unheard of audience up to that point and well beyond.

Forget what else was airing or happening, or that Jersey Joe Walcott was defending his World’s Heavyweight Boxing Championship that very night and hour against a guy named Rocky Marciano—the fight had been blacked out on radio and television anyway and could only be seen live in Philadelphia or via a primitively skeletal network of closed circuit venues (complete with its famous knockout punch)—people wanted to hear what this man accused of financial improprieties would have to say. Would he resign from the Republican ticket? Would he tell the truth? Would he really give out his personal financial details when no other politician at the time did?

What viewers saw that night was a presentation—primitive in its production quality, in keeping with the technology of the young medium—carefully crafted and skillfully delivered. It was a deliberately arranged combination of facts, figures, family, and country. At moments it was clinical. Occasionally it was corny. But it all worked.

The great General of World War II and D-Day, Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Republican candidate for President and the man who held Nixon’s fate in his recently-indecisive hands, made notes as he watched his young running mate on television. And at one point, something Nixon said so disturbed him that he broke his pencil on his pad of paper.

Mrs. Eisenhower wept as she watched.

Mrs. Nixon sat near her husband at the otherwise empty El Capitan Theater in Hollywood. Some reporters saw his wife’s presence cynically, but they soon forgot about it as Mr. Nixon told a story that would chisel this small screen moment in storied stone. It was about a cocker spaniel: Yep—a dog. A dog named Checkers.

The broadcast was missed by many and dismissed by many more. The Democratic nominee for President that year, Adlai Stevenson—a man who prided himself on his use of the spoken word—didn’t even bother watching. He was convinced that television was a passing fad for plebeians. And even after watching the speech, Mr. Eisenhower still did not know what to make of, or do, with Nixon. It was powerful political drama, but more than that—it was great cultural drama.

The broadcast was missed by many and dismissed by many more. The Democratic nominee for President that year, Adlai Stevenson—a man who prided himself on his use of the spoken word—didn’t even bother watching. He was convinced that television was a passing fad for plebeians. And even after watching the speech, Mr. Eisenhower still did not know what to make of, or do, with Nixon. It was powerful political drama, but more than that—it was great cultural drama.

Nixon didn’t read a script or use a teleprompter, but rather he used a few notes to aid his prodigious memory, as would be his style throughout most of his public career. He demonstrated a mastery of detail and appeared to Americans as a sort of new kind of political communicator—just a guy having an animated conversation with friends. When the half-hour was up, the camera lights turned off before the candidate could actually give out the contact information for phone calls and telegrams to the Republican National Committee. Mad at himself for such an inexactitude, he was certain that he had failed—until he noticed one of the cameramen crying.

A few minutes later Darryl Zanuck, the Hollywood mogul whose career included the production of the first “talking” movie (The Jazz Singer in 1927) and hits such as All About Eve (1950), phoned. He told Richard Nixon that the broadcast was “the most tremendous performance” he’d ever seen. This from a man known for the saying: “There is nothing duller on the screen than being accurate but not dramatic.”

Calls and telegrams overwhelmed the RNC. It was quickly obvious that Nixon had not only won the day, but that he had tapped into something powerful. He had gone directly to the people in a way not really done before. Americans had read and heard speeches for generations, but this was something different—they saw and, for a brief and shining moment, they connected. And what too many casual observers miss is that Richard Nixon not only survived his first firestorm, he triumphed that night in 1952.

[This article was originally written for the Nixon Foundation -- DRS]

September 21, 2013

Of History and Historical Fiction

[I wrote this blog post for VENTURE GALLERIES -- DRS]

[I wrote this blog post for VENTURE GALLERIES -- DRS]

Larissa MacFarquhar, writing in the New Yorker last year called historical fiction, “a hybrid form, half-way between fiction and nonfiction. It is pioneer country, without fixed laws.” My observation is that sometimes historical fiction leans more to the latter, other times to the former. It depends, I suppose, on the writers taste—in writing and for research.

One of the projects I am currently developing is in the historical fiction genre, but I am trying my best to be accurate and precise. You might think this to be oxymoronic, but I find myself seeking the same level of exactitude when it comes to details that I have in all of my nonfiction writing. And just as my developing book is a work in progress, so is its author.

The story I am writing is set in a Pennsylvania steel town shortly after the end of World War II. So I have immersed myself in material about the era and region. I find myself wanting to get every detail right so that in the quite unlikely chance that a retired local historian from the town I am writing about should read the book, I’d get a nice note complimenting on my accuracy. Bob Schieffer (CBS News), who wrote the forward to my book, The Shooting Salvationist: J. Frank Norris and the Murder Trial that Captivated America, was drawn to the manuscript because of my attention to detail in telling some of the history about Fort Worth, Texas—his home town. And that was pretty cool.

Now, does this ultimately matter? Does being such a stickler for historical precision help move the story forward? Not really. In fact, I’m pretty sure some of it might actually get in the way. I can almost feel the biting cynicism of a customer review on Amazon: “Stokes spends too much time on trivia that means nothing to us, unless we grew up in that town. Who cares what diner had the best blueberry pie in town.”

But we are what we are. I will always be a sucker for that next pesky morsel of factoid.

So why write historical fiction—why not just stick with history itself and write a nonfiction account of something? I mean, David McCullough’s books aren’t so bad, and some say they read like novels. I agree, and I am a big McCullough fan. In fact, when I read one of his books, it makes me want to sell my Mac Air and buy a set of bongo drums, knowing I’ll never be able to write like him. But here’s the thing—what about great stories, real ones, from history, where there is not enough material in the records to fill in all the blanks?

This is, I think, the greatest service the historical fiction writer can provide for readers. Sometimes the only “story” we have exists in fragments. The DNA of the narrative is there, but not easily seen. Enter the practitioner of the craft of historical fiction. The writer builds a superstructure on those fragile fragments, but always with an eye on all relevant facts and materials extant.

The late Irving Stone was a genius at this. Writing in the preface to The President’s Lady: A Novel About Rachel and Andrew Jackson, he said of the historical elements of the book that it was, “as authentic and documented as several years of intensive research, the generous assistance of the historians and librarians in the field, and literally thousands of books, magazines, pamphlets, newspapers, diaries, public records, correspondence and collections of unpublished memoirs and doctoral theses can make it.”

Irving Stone

1903-1989

Nuff said.

Then Stone dropped the other shoe: “The interpretations of character are of course my own; this is not only the novelist’s prerogative, but his obligation. Much of the dialogue had to be recreated, but every effort has been made to create it on the basis of individual character, personality, temperament, education, idiosyncrasy, as well as recorded conversations and dialogue, memoirs, diaries, letters and published accounts by relatives, friends, associates, even of detractors and enemies.”

To my mind, the late and lamented Mr. Stone struck the right balance and set a standard for all who dare to recreate the past.

September 17, 2013

WHEN THE STARS VANISH – By Peter Wehner

[With the author’s permission, I am privileged to share this excellent article that appears at Patheos.com -- DRS]

When the Stars Vanish

By Peter Wehner

A recent interview in Relevant magazine caught my attention. In it, the journalist Peter Hitchens made this observation:

This is a period of great material wealth and the worships of economic growth and the century of the self, in which religious belief is going to be in trouble. The best metaphor for the state of mind in which we find ourselves is this is the first generation of the human race which doesn’t generally see the stars at night. It has blotted them out with street maps and car headlights and everything else. You simply can’t see the stars in most places where human beings are concentrated, and, in the same way, the triumph of consumerism and growth and the temporary joys of pleasure as a substitute for happiness blotted out the metaphorical stars of religious faith. It’s very hard to expect people who can’t see the stars to examine the significance of the stars or see their beauty.

This is an insightful and eloquently stated point. In acknowledging that, I need to insert a couple of qualifications, the first of which is that I believe wealth is better than poverty for all the obvious reasons – from mitigating human suffering to creating the conditions to foster human flourishing. (Among many other good things, wealth allows people to participate in uplifting cultural experiences, provides assistance to the needs of their children, supports worthy charities and funds college educations.) And my own situation qualifies me as wealthy, at least relative to most of the rest of the world and to those who have lived throughout history. Let’s just say no one will confuse my lifestyle with that of St. Francis of Assisi. (There is no record of him owning the 13th century equivalent of a plasma TV, at least after his pilgrimage to Rome in his early 20s.)

Still, one can appreciate the truth of what Hitchens is getting at. It’s no secret that often the danger posed to Christians over the millennia is less persecution than worldliness; that it is wealth and power that often undermine spiritual discipline and draw our affections away from the Lord; and that riches can be distractions, averting our gaze from what matters most.

The reason for this may be because every human heart is divided against itself, easily distracted, prone to waywardness. Living in the most opulent and consumeristic society in human history can magnify those tendencies; it can place in shadows and mist the understanding that this is not our true home, that we are citizens of another kingdom. That has been, at least for me, an ongoing challenge in my Christian pilgrimage. How do we die to self while living in a culture that so relentlessly celebrates the imperial self?

In his autobiography Pilgrim’s Way, John Buchan warned about his nightmare world. “It would be a feverish, bustling world,” he wrote, “self-satisfied and yet malcontent, and under the mask of a riotous life there would be death at the heart.” He goes on:

Men would go everywhere and live nowhere; know everything and understand nothing. In the perpetual hurry of life there would be no chance of quiet for the soul. In the tumult of a jazz existence what hope would there be for the still small voices of the prophets and philosophers and poets? A world which claimed to be a triumph of the human personality would in truth have killed that personality. In such a bagman’s paradise, where life would be rationalised and padded with every material comfort, there would be little satisfaction for the immortal part of man. It would be a new Vanity Fair… Not for the first time in history have the idols that humanity has shaped for its own ends become its master.

That is, I think, what Peter Hitchens was getting at with his metaphor about the stars being blotted out, with us unable to examine either their significance or their beauty.

Now it needs to be said that every society has struggled with its own set of problems, many of them far worse than this one. But societies also struggle to identify their problems, to understand the challenges they present not just to national greatness but to the human spirit, to our capacity to perceive reality rather than getting caught up in alluring images and evanescent pursuits.

Perhaps the most worrisome thing of all is not that we can’t see the stars, but that so many people don’t even seem to miss them.

September 13, 2013

Uncle Vladimir

[This column appears at TOWNHALL.COM today - DRS]

Vladimir Putin is currently cashing in on an ill-advised promise made when two presidents thought no one was listening. You may recall President Obama’s whispered assurance, back in March of 2012, to then Russian president, Dmitry Medvedev: “This is my last election. After my election, I have more flexibility.”

We are now witnessing that promised flexibility. America’s foreign policy is becoming a caricature—international affairs according to Gumby.

Russian President Vladimir Putin is a mix of Joseph Stalin and Lavrenty Beria—an experienced strongman and savvy intelligence officer. He is hardly someone to be impressed by “flexibility.” Vladimir is all about power and the expansion of Russian influence on the world. He also enjoys it when America looks bad. It makes him smile—sort of.

Russian President Vladimir Putin is a mix of Joseph Stalin and Lavrenty Beria—an experienced strongman and savvy intelligence officer. He is hardly someone to be impressed by “flexibility.” Vladimir is all about power and the expansion of Russian influence on the world. He also enjoys it when America looks bad. It makes him smile—sort of.

A while back, I read Michael Dobbs’ account of what happened when the “Big Three”—Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin—met at Yalta to carve up what was left of Europe. The book is called, Six Months in 1945: From World War to Cold War. I heartily recommend it to anyone wondering if history repeats itself, or at least rhymes.

Dobbs gives a wonderfully detailed account of a weak president being bested by a determined Soviet dictator. FDR gave territory and history away to a ruthless tyrant. A war that started, in part, with a Soviet invasion of Poland, ended with Soviet dominance of Poland and the rest of Eastern Europe.

Now with Vladimir Putin inserting himself in a grand way into the current Syria crisis, not to mention joining the editorial staff of the New York Times, the voice of Yogi Berra can be heard crying in the wilderness: “It’s déjà vu all over again.”

We must learn from history’s clock. It was dangerous and wrong to trust the Russians back then, and it is dangerous and wrong to trust them now.

In May of 1945, George Kennan was an American diplomat living and working in Moscow. Most Cold War buffs know very well of Kennan’s memo writing skills. His February 1946 “long telegram” is considered to be one of the seminal documents of the Cold War. In it, he described the Soviet Union’s “neurotic view of world affairs” and the “instinctive Russian sense of insecurity,” not to mention their, “secretiveness and conspiracy.”

But ten months earlier, Kennan wrote a memo that was largely overlooked at the time due to his relatively insignificant role as “nothing more than a highly competent clerk.” It is, in fact, that memo Mr. Obama and team should revisit right now. In language similar to what he would use in 1946, he bluntly acknowledged that Joseph Stalin knew just what buttons to push to get the United States to do his bidding. The Russians were already manipulating reality and events and had been all along. Kennan wrote: “They observe with gratification that in this way a great people can be led, like an ever-hopeful suitor, to perform one act of ingratiation after the other without ever reaching the goal which would satisfy its ardor and allay its generosity.”

Franklin Roosevelt gave the store away to Mr. Stalin and company at Yalta. His inexperienced successor, Mr. Truman, didn’t do much better at Potsdam. But of course, they were dealing with a Soviet dictator and we are dealing with Vladimir Putin. Putin is nothing like Stalin, right?

Actually, Mr. Putin has more in common with the pock-faced “man of steel”—referred to at times by Roosevelt and later Truman as “Uncle Joe”—than most people care to notice. He is driven by power and is one dangerous dude. The decision to portray him in sinister terms in my novel, Camelot’s Cousin, was not just a fictional tool, but rooted in scary reality. There are good guys and bad guys in the world. And then there are dumb guys who can’t tell the difference. They may be the most dangerous of all.

Actually, Mr. Putin has more in common with the pock-faced “man of steel”—referred to at times by Roosevelt and later Truman as “Uncle Joe”—than most people care to notice. He is driven by power and is one dangerous dude. The decision to portray him in sinister terms in my novel, Camelot’s Cousin, was not just a fictional tool, but rooted in scary reality. There are good guys and bad guys in the world. And then there are dumb guys who can’t tell the difference. They may be the most dangerous of all.

As President Obama looks for solutions in Syria and the Middle East by dancing with Vladimir Putin, he is looking for love in all the wrong places.

Sixty-eight years ago, it took a glorified clerk and a recently-booted-out-of-office politician to remind the world that Russia could not be trusted. Kennan wrote his telegrams. And Winston Churchill gave a speech about “the sinews of peace” and that ominous “Iron Curtain.”

In many ways, the key to the present crisis and future success is a good long look at the past.

September 12, 2013

Putin Writing For The New York Times–Stranger Than Fiction?

Now that Vladimir Putin has apparently joined the editorial staff of the New York Times

Now that Vladimir Putin has apparently joined the editorial staff of the New York Times  , I am wondering how long it will be politically acceptable to make him and/or the Russians the “bad guys” in fiction?

, I am wondering how long it will be politically acceptable to make him and/or the Russians the “bad guys” in fiction?

Those of you who have read my novel, CAMELOT’S COUSIN, know that Mr. Putin is a player in the story. How did I connect him to the Kennedy Assassination, of all things? Well, you’ll have to read the book.

It now has more that 170 customer reviews at Amazon, with an average rating of 4.6 stars out of a possible 5. I am so grateful to the thousands of readers who have enjoyed the story. If you haven’t read it, grab a copy today, either in e-book or paperback format.

Here are a few of the customer comments about CAMELOT’S COUSIN. — Best Regards, — DRS

What some readers are saying (from Amazon Customer Reviews):

“The author has taken true historical facts of the Cold War era and woven a most wonderful tale which is difficult to put down. Even touching upon and offering a believable reason for the assassination of President John F Kennedy, the book is very readable for someone like me who has lived through the post war sabre rattling between the USSR and the USA. A book to be enjoyed and one that makes for much conjecture as to what really happened.” – Barrie M

“Love the book. Gives you a new possible view of the Kennedy assassination . It is fictional but very believable story.”- Mary Faust

“Love the book. Gives you a new possible view of the Kennedy assassination . It is fictional but very believable story.”- Mary Faust

“I was interested to read this because I used to work for an attorney in Memphis, now deceased, that was a member of the OSS and was stationed in London during WWII. He had spoken to me of Kim Philby and he had several books in his library about him so the subject was of great interest to me. I really enjoyed the writing style of Mr. Stokes and the story moved along nicely. As a fan of historical fiction I recommend this book to any one who is interested in the subject.” - Florence Izzi

“I tried this book on for size because I enjoy reading espionage stories and this one sounded interesting. I was not at all familiar with the author but I am a huge fan now. This is a terrific book! Stokes writes in a style that flows and informs as well as entertains. I found the Kennedy tie in to not only pique my interest but hold it firmly tight. This is one of those keep me on the edge of my seat–I hate to put it down for fear I’ll miss something books. I will most definitely turn to other books by Mr. Stokes. Check this out my friends–you’ll be glad you did” – Daniel

I ordered this e-book because it was cheap. Boy, was I in for a big surprise. The storyline is fast-paced and really, really believable. My acid test for a book is whether it keeps me reading at bedtime. This one passed with flying colors. My only disappointment is that there’s no sequel.- Longtime Sailor [ Note to Longtime Sailor - I am working on sequel now, stay tuned! -- DRS]

“This book is a wild ride through history and into the present, pulling in the famous Cambridge spy ring and its star defector Kim Philby, Putin’s Russia, and with side trips into JFK’s Oval Office. The book is fiction, but is presented in such a way that builds a case for believability as each piece of information gathered is placed into the growing puzzle. It’s well-crafted and digs deeply into the old late 20th century world of spying and tradecraft, enough to warm the heart of most spy thriller veterans. Most of the book is presented at a pretty fast clip, but slows down near the end as both the hero and the reader need time to wind things down to a realistic and satisfying conclusion. Just because the Cold War is over, it isn’t necessarily the end of exciting, modern spy novels. This book proves it by using the past as a basis for adventure and excitement in the present. Recommended.” – Nyssa

“In recent moths I have read many books associated with JFK and his assassination. This one was an up-all-nighter..I recommend it for a new POV for the conspiracy theories around this event..”- Mary K. Hunt

As someone who was beginning a career in counterintelligence in 1963 I found this book to be very interesting and informative with great historical insights. Anyone interested in the Cold War period, espionage and spies will find this a great read. – Harry J.

Read these and the rest of the 171 customer reviews HERE.

September 5, 2013

This Old Dog Learned A New Trick ;)

[I wrote this blog for VENTURE GALLERIES — Please check out their great site! – DRS}

Sometimes I wonder if I would be a writer if I lived—say—200 years ago. No keyboards, no grammar checkers, no font choices, no copy and paste—no Internet. Yikes! Of course, the ubiquitous distractions of modernity were nowhere to be found, so maybe I’d have more time for quiet thought. But then again, what about saving copies of our work? I remember reading about a Bible teacher who had labored long over a project to publish an edition of the English Bible with copious notes, diagrams, and a built-in concordance—features quite common today, but unheard of as the 19th century gave way to its successor. Then the notes were lost in shipping (literally lost—as in the ship sank) and he had to start over. Bummer.

I seldom long for the good old days, because they probably weren’t all that good, after all. Give me cell phones, Twitter, Facebook, my Mac Air, and a high-speed wireless signal, any day. But at the age of 57, I know that my capacity to learn new stuff is limited. I often call on my grandkids for tech-support. It’s cheap, usually just a promise to look the other way while they raid the forbidden snacks in the pantry.So when I started hearing and reading about a computer program for writers called Scrivener (and its companion, Scapple), I was both intrigued and intimidated. I saw the potential, but I dreaded the journey along the learning curve.

I seldom long for the good old days, because they probably weren’t all that good, after all. Give me cell phones, Twitter, Facebook, my Mac Air, and a high-speed wireless signal, any day. But at the age of 57, I know that my capacity to learn new stuff is limited. I often call on my grandkids for tech-support. It’s cheap, usually just a promise to look the other way while they raid the forbidden snacks in the pantry.So when I started hearing and reading about a computer program for writers called Scrivener (and its companion, Scapple), I was both intrigued and intimidated. I saw the potential, but I dreaded the journey along the learning curve.

Over the past several months, I tried to figure it out. I’d spend an hour, or two, or three, and all it did was fuel a sense of frustration and personal irrelevance. But then I’d read another review, or some knucklehead Facebook “friend” would sing Scrivener’s praises, and I’d convince myself that I should give it one more try. Being a Christian, not to mention a minister, I try to avoid bad words, but I confess that many such words were making their way from brain toward tongue. I never used them, but I know that if someone nearby had written them down, I would have signed the document.

Then, in a moment of indescribable insight the breakthrough came. Like Archimedes the day he stepped into a bath and discovered the principle of “displacement,” I too exclaimed, “Eureka” (“I have found it”). I had crossed over from the darkness to the light, from ignorance to bliss, and to a new method. I may never use pen and paper again. All of a sudden, it all began to make sense.

How do such breakthroughs come—whether in learning something new, or in coming up with ideas for a writing project? I think they tend to come after a period of formative frustration. I think we most often must go through the valley before we can scale the mountain. But the reward of that moment of crystal clarity makes it all worth it.

Leo Szilard was a 35 year-old Hungarian theoretical physicist in London in 1933. And like most people in his profession during those days, he was wrestling with the problem and potential of the atom. One rainy afternoon, he was waiting for a light to change near the British Museum. When the light turned green, he began to walk. As he took his first step, everything changed. He later recalled that “time cracked open before him and he saw a way to the future.”

Admittedly, my breakthrough in learning a new computer program isn’t as significant as the splitting of the atom, but still—it’s a wonderful experience when the light comes on.