David R. Stokes's Blog, page 8

September 2, 2013

A Labor Day Look Back At A Pivotal Moment

Today, on Labor Day 2013, it’s likely that many Americans know little about the circumstances and conditions that influenced the labor movement in America. I am a supporter of “right to work” laws, but I also know that there was a time when unionism provided the only hope millions of workers had for better working conditions–not to mention better lives.

Today, on Labor Day 2013, it’s likely that many Americans know little about the circumstances and conditions that influenced the labor movement in America. I am a supporter of “right to work” laws, but I also know that there was a time when unionism provided the only hope millions of workers had for better working conditions–not to mention better lives.

On March 25, 1911, approximately 500 workers were crafting “shirtwaists,” blouses with puffy sleeves and tight waists. These garments were the height of feminine fashion in America during the years before World War I and worn by “Gibson Girls.” It was part of an image personifying beauty, with a touch of independence, popularized by illustrated stories developed by a guy named—yep, you guessed it—Charles Dana Gibson.

But the women and girls (primarily) working long hours to produce the “shirtwaists” were not likely to actually wear them. They were immigrants for the most part, underpaid and overworked. They labored on the Lower East Side of New York City in a sweatshop at 29 Washington Place—specifically on floors seven through ten. On that particular Saturday they were wrapping up their otherwise typical workweek of many more than 55 hours or so, when a small fire started in a scrap bin. One sad hour later, glowing embers bore witness to an event of unspeakable horror. Sirens wailed throughout the city and hundreds of people made their way toward the scene of billowing smoke, “arriving in time to see tangles of bodies, some trailing flames, tumbling from the ninth-floor windows,” as described in the 2003 bestseller by David Von Drehle, Triangle—The Fire That Changed America.

It was a moment as pivotal as it was tragic.

The death toll reached 146, most of them women between the ages of sixteen and twenty-five. They died from burns, asphyxiation, trauma from a fall, or combinations thereof. In the aftermath of the Triangle fire, the movement toward trade unionism accelerated. Various governmental entities investigated and acted on issues such as low wages, the use of child labor, and employee safety. Eventually, several dozen laws and ordinances were enacted or enhanced, permanently changing the American workplace.

And part of the equation was the development of a strong labor movement in the country. In fact, standing in the crowd watching events unfold on that fateful day 100 years ago was a young lady named Frances Perkins, who would later serve as President Franklin Roosevelt’s Labor Secretary (the first woman in a presidential cabinet). She was famous for her observation that the Triangle fire was “the day the New Deal began.”

Few Americans today, no matter the political posture or affiliation, would seriously challenge the idea that things as they were in sweatshops in 1911 needed to change. And the next year, 1912, when the Titanic sunk, things changed to make sure ships had more lifeboats. Tragedies have often been the catalyst for constructive change and this has a way of honoring the memory of the fallen.

August 24, 2013

Ever Hear the One About Jack the Ripper and the Bible Teacher?

[I wrote this article for the Baptist Bible Tribune -- Springfield, MO, -- DRS]

GOD’S DETECTIVE

By David R. Stokes

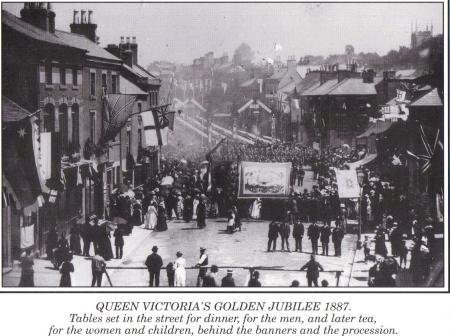

By the late 1880s, the British Empire was at its zenith — culturally, politically, and economically. Its capital, London, was, in effect, the capital of the world. Queen Victoria celebrated her Golden Jubilee in 1887, marking 50 years on the throne. She was called the grandmother of Europe in many quarters. The nickname was justified. Her children had married into many of Europe’s royal families.

William Gladstone and Robert Cecil (Lord Salisbury) were the strong political rivals of the day, Benjamin Disraeli having died in 1881. Arthur Conan Doyle’s new stories about a detective named Sherlock Holmes were becoming quite popular. H. G. Wells published his first short story in an obscure journal in 1888. A play called “The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde” was drawing capacity crowds to the Lyceum Theater in Westminster. George Bernard Shaw was trying to make a career as a literary critic. Fourteen-year-old Winston Churchill lived in London then — as did an eighteen-year-old young man from India named Gandhi.

William Gladstone and Robert Cecil (Lord Salisbury) were the strong political rivals of the day, Benjamin Disraeli having died in 1881. Arthur Conan Doyle’s new stories about a detective named Sherlock Holmes were becoming quite popular. H. G. Wells published his first short story in an obscure journal in 1888. A play called “The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde” was drawing capacity crowds to the Lyceum Theater in Westminster. George Bernard Shaw was trying to make a career as a literary critic. Fourteen-year-old Winston Churchill lived in London then — as did an eighteen-year-old young man from India named Gandhi.

Possibly they were among the readers of The Star — the largest evening circulation newspaper in London on Friday, August 31, 1888. If so, they might have noticed this item on the front page:

Mr. Robert Anderson, who succeeds Assistant Commissioner J Munro at Scotland Yard, is the third son of Matthew Anderson, of Dublin, formerly Crown solicitor for the city and county of Dublin. He is forty-seven years of age, and married in 1873 to Agnes Alexandrina, sister of Ponson by W. Moore, cousin and heir presumptive of the Marquis of Drogheda. Mr. Anderson was educated at Trinity College, Dublin, where he holds the honorary degree LL.D, and entered a student of the Middle Temple in 1860, and was called to the Bar 1870, having previously been called to the Dublin Bar in 1863.

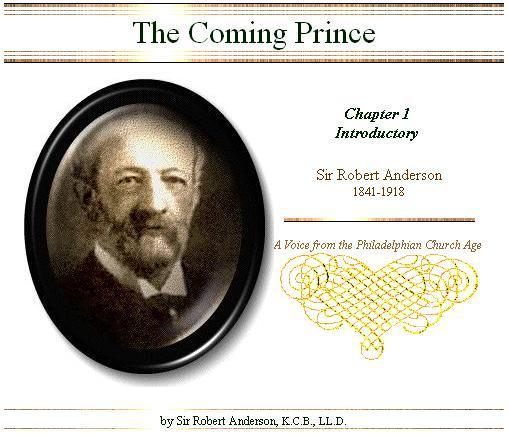

Described as “London’s foremost detective,” Robert Anderson was a tall man of “precise habits and quiet demeanor, and whose face is that of a deep student.” Absent from the announcement in The Star was any reference to Mr. Anderson’s other life and work. He was a devout Christian and the prolific author of several books about the Bible, one of which unlocked a code found in one of the Old Testament’s most cryptic visions.

The timing of the notice in the newspaper that August evening was interesting, for just across the same page was a story headlined, “A Revolting Murder.” It described the horrific discovery of the body of a woman in the Whitechapel area of London’s East End. Her name was Mary Ann “Polly” Nichols. She was the first victim of the infamous serial killer Jack the Ripper.

Quite a day to begin a new job as “London’s foremost detective.”

Though of Scottish descent, Robert Anderson was born in Dublin, Ireland, on May 29, 1841. His family was active in the Irish Presbyterian Church, and his father, Matthew Anderson, was an important official in the city. He was a Crown Solicitor. It was his job to prepare cases for criminal prosecution. There can be little doubt that the dual themes of Robert’s life were developed early on through his father’s life and influence — theology and criminal law.

Robert was very young when an infamous blight turned Ireland’s potato crop — the staple of the nation’s diet — into black, fungus-laden, mush. Due to his father’s secure position and salary, the Andersons were somewhat removed from what was going on in rural areas. As he grew through his teen years, two cultural dynamics influenced Robert’s life and career. First, there was the emergence of the Irish nationalist movement. Britain had done very little to help the suffering people in Ireland during the potato famine, and many were passionate about Ireland becoming an independent nation. The issue became an international concern because more than a million Irish citizens left home to seek better lives in the United States. Irish- Americans who supported Irish independence were known as Fenians — a nomenclature that eventually described all wings of the nationalist movement.

Robert was very young when an infamous blight turned Ireland’s potato crop — the staple of the nation’s diet — into black, fungus-laden, mush. Due to his father’s secure position and salary, the Andersons were somewhat removed from what was going on in rural areas. As he grew through his teen years, two cultural dynamics influenced Robert’s life and career. First, there was the emergence of the Irish nationalist movement. Britain had done very little to help the suffering people in Ireland during the potato famine, and many were passionate about Ireland becoming an independent nation. The issue became an international concern because more than a million Irish citizens left home to seek better lives in the United States. Irish- Americans who supported Irish independence were known as Fenians — a nomenclature that eventually described all wings of the nationalist movement.

The second cultural matter formative for Robert Anderson was the Great Irish Revival of 1859. This spiritual awakening was driven by prayer meetings and the powerful preaching of men such as Henry Grattan Guinness, grandson of the famous brewer of Irish stout ale. Robert attended several local services at the invitation of his sister. His analytical mind prompted him to listen to the preaching with the ear of a critic, but soon he proclaimed, “In God’s name, I will accept Christ!”

A stellar student, Robert graduated from Trinity College in Dublin in 1862 with a B.A. (eventually receiving the L.L.D. from Trinity in 1875). He studied briefly in France (Boulogne and Paris), before being admitted to the Irish Bar in 1863. But before plunging completely into a career, Anderson joined a team of missionaries and evangelists who traveled from town to town in Ireland preaching the gospel and seeking converts. His work as a lay-preacher fueled his desire to know the Scriptures. He immersed himself in the pages of the Bible and read it with a devoted heart and keen mind. The spadework for the books he eventually wrote about biblical themes was done during this time.

According to his diary, Robert preached not only in churches, but “in schoolrooms, court-houses or jury rooms, in private houses, cottages or barns, once at least in a ballroom, at times in open-air.” He wrote to his sister, “We are living in the pilgrim fashion,” and he recounted stories of God’s work, such as one about a man who “said that a week ago he was the vilest wretch in the country, but now saved.”

The fulltime ministry was not, however, to be Robert Anderson’s permanent path. He would remain passionate about his faith for the rest of his life, but he would do so as a layman. Imitating the biblical character Daniel — a man he wrote much about — Anderson would be a civil servant, involved in matters that were anything but the stuff of gospel meetings.

Largely through the influence of his father, Robert was drawn into Secret Service work. In 1865, Matthew Anderson was prosecuting a number of Fenian members charged with treason. He turned to his sons Samuel and Robert for help with the research side of things. He trusted them with confidential reports and other secret information that crossed his desk.

Nepotism may have been his gateway to the world of secrets, but Robert Anderson quickly demonstrated that he was a natural. One historian wrote of him that he was “able to work with the quiet patience and efficiency of a spider.” The same mind that found the Bible so fascinating — particularly various cryptic prophecies — also found intelligence gathering to be very interesting.

Irish nationalists referred to people like the Anderson family — Irish, but not in sympathy with the Fenians — as “castle rats,” a reference to the iconic Dublin Castle, the seat and emblem of British power in Dublin. But soon Robert became the resident expert on all things Fenian, and he wrote a detailed history of the movement for the authorities. This opened many doors for the young lawyer. His work on the project was known in the highest circles, and eventually Anderson was called to London to join a taskforce of sorts dealing with the Irish threat and political crime in general.

Along the way, Robert Anderson — while working on his writing about biblical themes in his spare time — became involved with the interrogation of Fenian prisoners. From there, it was a small step into the murky world of infiltration and espionage. Soon the man who had preached the gospel in the open air became a spymaster.

Thomas Beach, a.k.a. Henri Le Caron, has been called “the champion spy of the century.” That would be the 19th century. He infiltrated the Fenian movement in America for 21 years. And he reported directly to his handler in the British Secret Service — Robert Anderson.

A good number of Irish-Americans fought in the American Civil War — on both sides. By the end of the conflict in 1865, many of those same soldiers drifted into the Fenian cause. The more aggressive and extreme of the lot conceived a plan to attack British strongholds in Canada. The idea was to hold Canada hostage. This would be accomplished by seizing key cities and centers. If successful, the Fenians would then try to negotiate a trade with the reviled British — swap Canada for Ireland’s independence. Toward this end, there were four Fenian “raids” conducted between 1866 and 1871.

A good number of Irish-Americans fought in the American Civil War — on both sides. By the end of the conflict in 1865, many of those same soldiers drifted into the Fenian cause. The more aggressive and extreme of the lot conceived a plan to attack British strongholds in Canada. The idea was to hold Canada hostage. This would be accomplished by seizing key cities and centers. If successful, the Fenians would then try to negotiate a trade with the reviled British — swap Canada for Ireland’s independence. Toward this end, there were four Fenian “raids” conducted between 1866 and 1871.

The raids were doomed from the start, not only because the whole scheme was incredibly far-fetched, but also because of the work of spy Henri Le Caron and his handler, Robert Anderson. They made sure the best-laid Fenian plans were betrayed long before implementation.

In 1873, Robert Anderson married Agnes Alexandrina Moore — together they would have five children. Shortly thereafter he began writing books, many of which are still widely read by Bible students today. It was quite remarkable that Anderson could think through and produce so many detailed studies of scriptural issues while immersed in a demanding and intense career. An old college friend wrote to him in 1876, “How on earth have you had time to dive into theology?” But he found the time and spent it well.

The Gospel and its Ministry was published in 1875, dealing with the great themes of grace, faith, repentance, reconciliation, and justification. A bit later he wrote what was likely the most widely read of his books — The Coming Prince. In it he dealt in-depth with prophecies found in the Book of Daniel about an end-time ruler. Probably the most famous — and controversial — part of the book is Anderson’s calculation and solution regarding Daniel’s vision of “seventy-weeks.”

With the help of the Royal Astronomer, Sir George Airy, he fixed the date of the decree by Cyrus for the Jews to “restore and build Jerusalem” at March 14, 445 BC. Anderson calculated 173,880 days — accounting for 69 weeks of years on the lunar calendar — and arrived at April 6, 32 AD as the date Jesus entered Jerusalem, shortly before his crucifixion. The final “week” would be later in history and feature the ungodly work of the Antichrist, “who by the sheer force of transcendent genius will gain a place of undisputed pre-eminence.”

A few years later Anderson wrote Human Destiny, an examination of life after death from a biblical perspective. It thoroughly examined theories such as “universalism” and “conditional mortality.” One contemporary preacher, none other than Charles Haddon Spurgeon, considered this Anderson book to be “the most valuable contribution on the subject.” Later he wrote The Silence of God (which comforted many in Britain during The Great War) and The Bible and Modern Criticism.

In all, he wrote 17 volumes based on biblical issues, as well as three books about his work for the government. His circle of friends included Lord Salisbury (Robert Cecil), William Gladstone, Henry Drummond, James M. Gray, C. I. Scofield, A.C. Dixon, C.H. Spurgeon, E. W. Bullinger, John Nelson Darby, and many others.

Anderson’s work as a spymaster eventually led to an appointment as Irish Agent at the Home Office in London. He moved in influential circles, often in the company of the rich and powerful. He was invited into the “Gossett’s Room” — an elite club usually reserved for members of Parliament. Over the next several years, Robert Anderson, in addition to his work with the Home Office, served as secretary of the Royal Commission on Loss of Life at Sea, secretary of the Prison Commission, and on the Royal Observatory of Edinburgh Commission.

Anderson thought of leaving government service in the early 1880s, possibly to pursue his writing full time. But the rise of Fenian violence in London — including several bombings — kept him connected to secret work. He was involved in the creation of a new intelligence organization called the Special Irish Branch. This role put him in the perfect position at Scotland Yard to step into what would become the most sensational and controversial murder investigation in history.

Robert Anderson’s official title was Assistant Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police and Chief of the Criminal Investigation Department (CID). And he was the man in charge of the big case as fear gripped East London.

Eventually, five women were savagely murdered — the victims of Jack the Ripper (there are many who think there could have been as many as 18). The spree ran from the 31st of August in 1888 through the following November 9th, ending abruptly and mysteriously with the killing of Mary Jane Kelly.

The crimes have never been solved and opinions abound. The list of suspects involves more than 30 names, including a member of the Royal family, author Lewis Carroll (Alice in Wonderland), and at least one woman.

Robert Anderson actually believed that the crime had been solved, and over the years he left hints as to the identity of the killer. For example, this item was in the March 21, 1910, edition of the Washington Post:

Sir Robert Anderson, for more than 30 years chief of the criminal investigation department of the British government, and head of the detective bureau at Scotland Yard, has at length raised the veil of mystery which for nearly two decades has enveloped the identity of the perpetrator of those atrocious crimes known as the Whitechapel murders.

Sir Robert establishes the fact that the infamous “Jack the Ripper,” as the unknown slayer had been dubbed by the public, and at whose hands no less than fourteen women of the unfortunate class lost their lives within a circumscribed area of the east end of London, was an alien of the lower, though educated class, hailing from Poland, and a maniac of the most virulent and homicidal type — of a type recorded, by reason of its rarity, in medical treatises, but one with which the world at large is not familiar.

But the most important point of all made by Sir Robert is the fact that once the criminal investigation department was sure that it had in its hands the real perpetrator of the Whitechapel murders it procured from the secretary of state for the home department a warrant committing the man for detention “during the Kings’ pleasure” to the great asylum for the criminally insane at Broadmoor five or six years ago.

The man’s name was Aaron Kozminski. In 2011, “Ripperologist” Robert House wrote a book called Jack the Ripper and the Case for Scotland Yard’s Prime Suspect. In it, he makes the case that Robert Anderson was right, and that Kozminski was indeed the notorious serial killer.

Anderson retired from public life in 1901 and was knighted. He would be known ever after as Sir Robert Anderson. He spent his remaining days preaching and writing, advancing the cause of Christ and paying special attention to biblical prophecy and the second coming of Christ. He remained a keen student of current events and international affairs, always viewing them through the prism of God’s Word.

Anderson retired from public life in 1901 and was knighted. He would be known ever after as Sir Robert Anderson. He spent his remaining days preaching and writing, advancing the cause of Christ and paying special attention to biblical prophecy and the second coming of Christ. He remained a keen student of current events and international affairs, always viewing them through the prism of God’s Word.

Interestingly, Anderson himself seemed to wax prophetic when he wrote these words in the 1890s: “History repeats itself, and if there be any element of periodicity in the political diseases by which nations are afflicted, Europe will pass through another crisis and it is impossible to foretell how far kingdoms may become consolidated and boundaries changed.”

He lived to see that great crisis — The Great War — but not long enough to witness the full measure of consolidated kingdoms and shifted boundaries. A few days after the armistice, Robert Anderson, as did millions of others around that time, succumbed to Spanish Influenza. He died on November 15, 1918.

David R. Stokes is an author, broadcaster, columnist, and Senior Pastor of Fair Oaks Church in Fairfax, VA. His personal website is http://www.davidrstokes.com.

August 21, 2013

What About Negative Reviews?

David R. Stokes

[I wrote this blog for VENTURE GALLERIES - check out their wonderful site! - DRS]

Nearly a quarter century ago, my wife and I lived in Brooklyn with our two young daughters. Yes, that Brooklyn—the one in New York. And this was long before that borough of New York City became trendy. All it was back then was, well, Brooklyn.

The late Edward Irving Koch was the Mayor of New York City at the time. He was very popular. He used to go from event to event and ask crowds large or small a signature question: “How am I doing?” He wanted feedback. It was gutsy to ask New Yorkers to share their opinions. It was also superfluous because they never seemed to need prompting to do so.

They still don’t.

While writers don’t regularly ask readers their opinions, those opinions are generally forthcoming. They’re called reviews. They are a vital part of a book’s journey along the path from publication to purchase. Most potential readers of our work read a few reviews before making a purchase.

It’s nice to get good reviews, but it doesn’t always work out that way. In Mr. Koch’s case, there came a time when he stopped asking his trademark question. The feedback was too painful.

What should we make of reviews—the good, the bad, the ugly?

We should realize their importance in the grand scheme of things, but never allow them to define us. If we adopt an approach of calculated indifference, we can glean from some of the constructive comments from readers. We can also find the strength to ignore some of the more—shall we say—caustic comments.

Recently, I noticed two reviews that popped up about my novel, Camelot’s Cousin. One said, “Great read!! It’s seldom that I find a book so captivating. Difficult to put down. When a book of fiction combines an interesting time of history with facts, it’s destined to become a best seller.”

Recently, I noticed two reviews that popped up about my novel, Camelot’s Cousin. One said, “Great read!! It’s seldom that I find a book so captivating. Difficult to put down. When a book of fiction combines an interesting time of history with facts, it’s destined to become a best seller.”

But before I basked too long in the glow of such erudite discernment, I read another review (this one from across the pond), “It is written as though for a ten year old from the USA with little or no education. If the writer was responsible for childrens (sic) American TV, I would not have been surprised. A poor story; unlikely plots; chidish (sic) characterisation. Should not have been published.”

As an old professor of mine used to say, “The middle of the road is a good place to be if there is a wreck on both sides.” Clearly, we must navigate the deep and often murky waters of reviews with the right attitude, and I think I have the answer. It comes from my “day job.” Many years ago, I came across an essay written by a famous preacher in London, England in 1875. His name was Charles Haddon Spurgeon, and he is still regarded as a “prince of preachers.”

The essay was called, “The Blind Eye and the Deaf Ear.” It was a reminder of the virtue of deliberately ignoring some of what we see and hear—especially when directed toward us: “Public men must expect public criticism, and as the public cannot be regarded as infallible, public men may expect to be criticized in a way which is neither fair nor pleasant. To all honest and just remarks we are bound to give due measure of heed, but to the bitter verdict of prejudice, the frivolous faultfinding of men of fashion, the stupid utterances of the ignorant, and the fierce denunciations of opponents, we may very safely turn a deaf ear.”

Do I read reviews of my books? Sure. But I do so with a “blind eye and deaf ear.”

August 11, 2013

Teddy Roosevelt’s Warning to Time Magazine

Not wanting to go the way of its former print rival, Newsweek, it is no surprise that Time magazine is looking for ways to generate buzz. Thus the provocative current cover story: “The Child Free Life: When Having It All Means Not Having Children.” I read the article while on vacation. Vacation with my family—including seven grandchildren, ironic, huh?

I immediately remembered reading something Theodore Roosevelt said, directly on point, in a famous speech more than a century ago—on April 23, 1910. I am aware that most American conservatives find little in the political ideas by Theodore Roosevelt worth salvaging, much less translating into present day policy. But he nailed it that day, not only by giving us his famous quote about “The Man in the Arena,” but also with something he said about “child free living.” It was part of a major address delivered at The University of Paris (The Sorbonne) titled “Citizenship In A Republic.”

Roosevelt left the White House in 1909 and was at the pinnacle of his renown a year later when he toured Europe. One journalist wrote at the time, “When he appears, the windows shake for three miles around. He has the gift, nay the genius of being sensational.” TR addressed a massive audience in the school’s grand amphitheater. The crowd included academicians, “ministers in court dress, army and navy officers in full uniform, nine hundred students,” and another 2,000 “ticket holders.”

The former president was introduced that day as “the greatest voice of the New World.” And hiding in the shadows of his remembered-as-the-man-in-the-arena-speech is a long since forgotten rhetorical rebuke to the ideas promoted in the current issue of Time:

Finally, even more important than ability to work, even more important than ability to fight at need, is it to remember that chief of blessings for any nations is that it shall leave its seed to inherit the land. It was the crown of blessings in Biblical times and it is the crown of blessings now. The greatest of all curses is the curse of sterility, and the severest of all condemnations should be that visited upon willful sterility. The first essential in any civilization is that the man and women shall be father and mother of healthy children so that the [human] race shall increase and not decrease. If that is not so, if through no fault of the society there is failure to increase, it is a great misfortune. If the failure is due to the deliberate and willful fault, then it is not merely a misfortune, it is one of those crimes of ease and self-indulgence, of shrinking from pain and effort and risk, which in the long run Nature punishes more heavily than any other. If we of the great republics, if we, the free people who claim to have emancipated ourselves from the thralldom of wrong and error, bring down on our heads the curse that comes upon the willfully barren, then it will be an idle waste of breath to prattle of our achievements, to boast of all that we have done.

That’s right. Theodore Roosevelt told the French that they needed to keep having babies.

At the time of Roosevelt’s speech, France was a major world power. Today—not so much. There is enough blame for such decline in global influence to go around, but the increased secularism of Europe, with its penchant for socialized everything, has certainly played a role.

Now more than 100 years later, there is an even greater threat to their cherished way of life. If only the French today would rediscover Teddy’s advice and reverse the birthrate trend—they might have a fighting chance. But such is the mindset of secularism, it is all about self and “fulfillment.” Issues of family, not to mention progeny are secondary, if thought about at all. Marriage is deferred—even eschewed. Children are planned—or better, planned around. And over time the birth rate in Europe has fallen far short of what is needed to keep up with the various demands of the future. In other words, the nations are aging. There are fewer children, yet more grandparents—a trend that will continue and accelerate.

Now more than 100 years later, there is an even greater threat to their cherished way of life. If only the French today would rediscover Teddy’s advice and reverse the birthrate trend—they might have a fighting chance. But such is the mindset of secularism, it is all about self and “fulfillment.” Issues of family, not to mention progeny are secondary, if thought about at all. Marriage is deferred—even eschewed. Children are planned—or better, planned around. And over time the birth rate in Europe has fallen far short of what is needed to keep up with the various demands of the future. In other words, the nations are aging. There are fewer children, yet more grandparents—a trend that will continue and accelerate.

It takes a fertility rate of 2.1 births per woman to keep a nation’s population stable. The United States is drifting away from that. Canada has a rate of 1.48 and Europe as a whole weighs in at 1.38. What this means is that the money will run out, with not enough wage-earners at the bottom to support an older generation’s “entitlements.”

But even beyond that, the situation in France also reminds us of the opportunistic threat of Islamism. It is just a matter of time before critical mass is reached and formerly great bastions of democratic republicanism morph into caliphates. In the United Kingdom the Muslim population is growing 10 times faster than the rest of society. In fact, all across Western Europe it’s the same. The cities of Amsterdam and Rotterdam are on track to have Muslim majority populations in a decade or two. A T-shirt that can be seen on occasion in Stockholm reads: “2030—Then We Take Over.”

A few years ago, Britain’s chief Rabbi, Lord Sacks, decried Europe’s falling birthrate, blaming it on “a culture of consumerism and instant gratification.” “Europe is dying,” he said, “we are undergoing the moral equivalent of climate change and no one is talking about it.”

The Rabbi was right, and so was Teddy.

August 2, 2013

Harding Dies–Coolidge Takes Charge

[My article appears at TOWNHALL.COM today]

Ninety years ago today, on August 2, 1923, President Warren G. Harding died at the Palace Hotel in San Francisco, California. It was sudden, shocking, and has been fodder for conspiracy theorists ever since. His wife, Florence—described derisively by some as “The Duchess”—didn’t allow an autopsy, so we’ll never know exactly what caused the demise of the 29th President of the United States. It might have been congestive heart failure, or food poisoning, or even something more sinister.

President Harding’s Funeral

Seen in retrospect, through the prism of the scandals associated with his White House tenure, Harding is usually ranked well toward the bottom of the list of presidents. In reality, he was a very popular and effective leader. But he was cursed with cronies—men who ensured that his name would forever be associated with political corruption. What is sometimes forgotten about Harding is that he also had some effective public servants on his team, men such as Andrew Mellon, Herbert Hoover, and above all, Vice President Calvin Coolidge, who succeeded Harding.

Historians tend to bunch the three Republican presidents of the 1920s – Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover – together in a way suggesting they were identical triplets separated at birth. But there were many differences – some subtle, some not so much.

Herbert Hoover, all of his speechifying about “individualism” notwithstanding, was not the fiscal conservative many today make him out to be. Mr. Hoover had a strong interventionist streak in his personality. So, in many ways, he helped to turn a recession into the Great Depression. Ironically, when closely examined, Herbert Hoover’s approach to economics had more in common with his successor than it did with the two men preceding him in the White House.

What is usually missed about Harding, though, is how effective he was on the issue of the economy. When he assumed the presidency in March of 1921, he inherited a mess. Woodrow Wilson had expanded the role and size of government dramatically, incurred a $25 billion dollar debt, and cracked down on political opponents – even imprisoning some (socialist activist Eugene V. Debs, etc.).

In fact, the economic problems in the 1920-1921 Depression were actually worse in many ways than the Great Depression a decade later. But that downturn didn’t last as long – thankfully. Warren Harding cut federal spending and lowered taxes. And in less than two years the number of unemployed in the country fell from 4.9 million to 2.8 million, en route to a rate of 1.8 per cent by 1926 under his successor, Mr. Coolidge.

Oh – and Harding set the political prisoners free, even inviting Debs to the White House. He was a classier act than many now remember.

The night Harding died, Coolidge was at his family home in Vermont. The house had no electricity or telephone, so word came to the vice president via messenger. He got up from bed and dressed. Then he knelt beside his bed and prayed, after which he went downstairs where his father, a notary public, administered the presidential oath to him.

By the time Calvin Coolidge became president, the country was on its way to enjoying some great years of prosperity. He was a fiscal conservative who tried his best to stay out of the way. He knew that the government functioned best as a referee – not as a participant in the economic game – or as a team owner.

Amity Shlaes has written the definitive biography of the man. It’s called, simply, Coolidge. It came out earlier this year, and I interviewed her on the radio about the book and the man.

After he was elected in his own right the next year, he told the nation in his March 4, 1925 inaugural address:

I want the people of America to be able to work less for the government and more for themselves. I want them to have the rewards of their own industry. That is the chief meaning of freedom. Until we can re-establish a condition under which the earnings of the people can be kept by the people, we are bound to suffer a very distinct curtailment of our liberty.

Then on yet another August 2nd, this one in 1927, President Calvin Coolidge had breakfast in the White House residence with his wife, Grace, and remarked to her “I have been president four years today.” It was one of those quick, concise, directly-to-the-point sentences she had been used to hearing since they met in 1905. It was also something the American people were familiar with, having nicknamed the 30th president “Silent Cal.”

He had a 9:00 meeting with reporters in his office that morning. Before fielding a few questions, he told those gathered: “If the conference will return at 12:00, I may have a further statement to make.” Curious, but compliant, in those long-since-gone days of semi-civility between presidents and the press, the journalists found their way back at noon.

An hour or so before that conference encore, Coolidge took a pencil and wrote a message on a piece of paper. He handed it to his secretary with the instruction to take it to his stenographer and have him make several copies – enough for the newsmen who would be at the 12:00 meeting. Ever the frugal man, he suggested that the brief statement could be copied several times on the same sheet, thus only using a few sheets of paper. He told the secretary not to give the note to the stenographer, though, until about 11:50 a.m.

He really wanted to manage this story.

He asked for the pages to be brought to him uncut and before the reporters were admitted to the office, he took a pair of scissors and cut the paper into smaller slips. When he was just about ready, he told his secretary: “I am going to hand these out myself; I am going to give them to the newspapermen, without comment, from this side of the desk. I want you to stand at the door and not permit anyone to leave until each of them has a slip, so that they may have an even chance.”

An “even chance” at a big scoop, that is.

The handwritten note from the president said: “I do not choose to run for president in nineteen twenty-eight.” Though the now classic Broadway play (made into several film versions), The Front Page, was yet a year away from being published and produced, it comes to mind with the image of dozens of reporters rushing to find telephones.

Calvin Coolidge could have been re-elected if he had wanted the job for another term. His anointed successor, Herbert Hoover, won big in 1928, though it is clear that Coolidge was less-than-enthusiastic about the “Great Engineer.” It is one of those curious “what ifs” of history – would Coolidge have dealt with the coming of the Great Depression better than his successor?

His decision not to run in 1928 – at the height of his popularity – puzzled many. But Coolidge understood the nature of leadership, and its seductions. He explained it this way:

It is difficult for men in high office to avoid the malady of self-delusion. They are always surrounded by worshipers.They are constantly, and for the most part sincerely, assured of their greatness.They live in an artificial atmosphere of adulation and exaltation, which sooner or later impairs their judgment. They are in grave danger of becoming careless or arrogant.

Of course, it can never be proven, but I suspect that had Calvin Coolidge decided to run again in 1928, he might have responded to the initial shockwaves of 1929-1930 differently than Hoover. And maybe, just maybe, the Great Depression would not have lasted so long. And maybe, just maybe, people who should know better these days would stop trying the same old failed “interventionist” tactics that never really worked backed then.

At any rate, Mr. Coolidge died suddenly on January 5, 1933, after Hoover had been badly beaten by Franklin Roosevelt. He did not live to see what a prolonged depression looked like, but I suspect that he would have ventured an opinion or two.

His words would have been brief and directly on point.

July 21, 2013

Maybe What Readers Want is Continuity…

[This blog written for VENTURE GALLERIES -- please check out that great site! -- DRS]

Having spent years writing primarily non-fiction—history articles, a narrative nonfiction book, some current events and politics—developing my novel, Camelot’s Cousin, was a learning experience. But one surprise came after the book was published.

I began to hear this from readers: “So, David, when do we get to read the next story in your series?”

Next story? Series? Such a thing had never been even a blip on my writing radar until people starting reading Camelot’s Cousin. My plan was to move on to one of about a dozen new nonfiction projects, such as my recently book, Firebrand. I had always seen my books and stories as “stand alone” creations. One stop. One shot. File the material in a closet. Move on.

Then it happened—minor clamor for the next edition. At first, I resisted it. I have too many other things I want to write. The novel was a somewhat of a lark. I wanted to see if I could do it.

Then one night, when my wife and I were catching up on one of our favorite television shows, watching a few episodes recorded on our DVR—it hit me. When it comes to fiction, people enjoy continuity, and they want to know what happens next. This revelation came to me after I heard myself say, “Wow, I can’t wait for the next episode.” It was one of those head-slapping, should-have-had-a-V-8 moments.

So I began to envision a new story involving the cast of characters from Camelot’s Cousin. I am several chapters into it, and I am hooked. I still want to write that other stuff, but I can now see about four or five stories built around my lead character, Templeton Davis, the popular and successful host of a nationally broadcast radio talk show.

Now, some reading this blog—especially my author colleagues—will likely see my teachable moment as something all too obvious. They might be tempted to think, “Sure, David, we get it. You saw the truck and flagged it down. And then you made a great discovery—they have these vehicles that drive around selling ice cream. You can buy it right in front of your house. Dude—do you live under a rock?”

Edward R. Murrow once said, “The obscure we see eventually. The completely obvious, it seems, takes longer.” I think all of us are like that to a point. It was just a couple of years ago that one of my daughters—32 years old at the time—figured out that the insignia on a New York Yankee baseball cap was actually the letters, “NY.” But then, I only recently noticed that the tune behind the song teaching children their “ABC’s” is the same as “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star.”

I don’t know how many books I’ll produce in the Templeton Davis series, but it will be fun watching the characters grow. Hopefully they’ll learn obvious things much quicker than the man with the computer behind the curtain.

July 8, 2013

Goodreads Book Giveaway

Goodreads Book Giveaway

Camelot’s Cousin

by David R. Stokes

Giveaway ends July 26, 2013.

See the giveaway details

at Goodreads.

July 3, 2013

Lexington, Concord, and the Crypt in the Basement

[This column will appear at TOWNHALL.COM on July 4, 2013]

If America was born 237 years ago this week, the case can be made that she was conceived decades earlier. Long before men named Washington, Adams, Jefferson, Hancock, and Franklin became notable and influential, there were a few clergymen—yes, preachers—who meteorically blazed across the colonial sky.

In September of 1775, five months after the battles of Lexington and Concord, and while the shot heard ‘round the world later immortalized by Ralph Waldo Emerson still echoed, some Continental Army volunteers gathered at a church in the small coastal Massachusetts town of Newburyport, located almost 30 miles northeast of Boston. They were about to go to battle—an initiative led by, of all people, Benedict Arnold. The men decided that a little prayer accompanied by an extemporaneous sermon might be a good idea.

Old South Church in Newburyport, MA

The town’s Old South Church had found a bit of recent fame as people proudly pointed out that the bell in its clock tower had been cast by a fellow named Paul Revere, who had just months before made a name for himself on horseback. Revere, of course, is better known for his connection to a certain Old North Church. But some of the citizen-soldiers listening to Chaplain Samuel Spring’s challenge that day knew that they were also in the presence of another important bit of history—something they saw as very relevant to the emerging War of Independence.

As they listened to the sermon that day, many of them couldn’t help but be preoccupied with the pulpit itself. On the Sunday immediately following the battles of Lexington and Concord, the local minister, Dr. Jonathan Parsons, spoke fervently about liberty. His passion prompted a man named Ezra Hunt to step into the church’s aisle to form a company of 60 fighting men on the spot—said to be the first such group to attach itself to the fledgling Continental Army.

But as if those two connections to the greater cause weren’t enough, there was a third even more compelling reason many of the men found the venue so fascinating.

It was what was under the pulpit that inspired them.

Five years earlier, a famous preacher had been scheduled to speak at the Old South Church in Newburyport. He was America’s most famous clergyman, although his preferred appellation was—“revivalist.” His name was George Whitefield. He died that morning in 1770. A few days later, with much grief and ceremony, he was buried in a crypt directly beneath the church’s pulpit –where his crypt remains to this day.

Many of the men sitting in the church on September 16, 1775, preparing to go to war, were restless. No disrespect was intended for the chaplain, they just wanted him to be done with his remarks so they could see Whitefield’s tomb. They wanted to make a connection—not only with history and fame: but with what we might now refer to as the DNA of faith.

Lost to many Americans today via the whitewash of history that has led to a bit of a cultural brainwash when it comes to the founding era, is the story of Whitefield and the Great Awakening he helped spark. The common revisionist narrative today places faith and matters of religion on the periphery of history—an enduring lunatic fringe encompassing past and present. This better fits the secularist worldview espoused by those who want us to see government, secular, and struggles for “social justice” as not only the way to move boldly into the future, but also as consistent with our past.

There will be reenactments this weekend illustrating Revere’s ride, volleys fired, and a declaration proclaimed, but what will be missing as America rounds up its usual respects this 4th of July will be a cultural revisit to the seeds planted in the hearts and minds of men and women in the decades before 1775-1776.

Ordained in the Church of England at the tender age of 22 in 1736, he quickly became well known for his voice—it was loud and commanding, but never shrill and off-putting. It was said that he could speak to 30,000 people (Benjamin Franklin counted them once) and that all could hear him, even in the open air. His diction and flair for dramatics had audiences hanging on every word.

Whitefield emphasized personal conversion with his powerful messages on the new birth from the Gospel of John. The converted formed new churches—hundreds of them. And they revived existing churches that had long been spiritually moribund.

The chronological locus for the Great Awakening was the period of 1740-1742, but the residual and enduring effects lasted into the revolutionary period. And this is where the history being taught in schools today—and that most of us grew up hearing—misses the boat.

While revolutionary France defined itself by its hostility to religion, Americans had no difficulty embracing the values of the Enlightenment and republicanism, while at the same time clinging to their religious principles.”

And we have the Reverend George Whitefield, among many others, to thank for this.

When the sermon was finally done at Old South Church that September day, some of the citizen-soldiers sought out the church’s sexton and asked to see where Whitefield was buried. The sexton actually opened the coffin and a few of the officers obtained tiny bits of material from the dead preacher’s collar and wristband, carrying them into battle as good luck charms.

Of course, I am not all that into amulets and such, but I find myself cutting these men some slack. Their simple excision of fabric was really an exercise in remembrance and connection. They knew that what they were going to do soon in battle was somehow, someway tied to what Whitefield and others had been part of years before.

Of course, I am not all that into amulets and such, but I find myself cutting these men some slack. Their simple excision of fabric was really an exercise in remembrance and connection. They knew that what they were going to do soon in battle was somehow, someway tied to what Whitefield and others had been part of years before.

America, for the most part, has long-since forgotten the spiritual roots of the revolution we’ll sort of remember this week. — DRS

June 26, 2013

Tell Me A Story

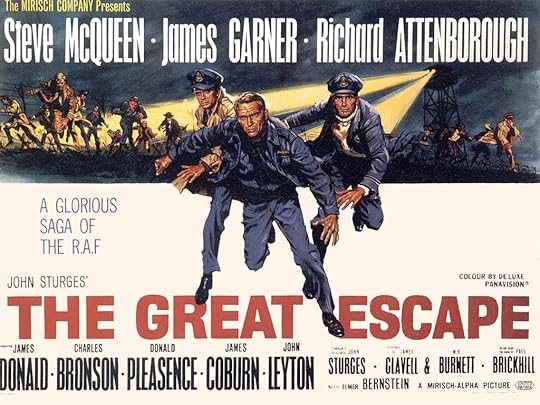

Part of my recent Father’s Day experience was the chance to watch one of my favorite movies from decades ago on the big screen. I’ve had the movie’s theme song as my cellphone ringtone for quite a while and, admittedly, I have seen the film so many times that I can quote much of the dialogue verbatim. My wife particularly enjoyed periodic demonstrations of this skill and knowledge last Sunday. Sure she did.

The film is the 1963 classic, The Great Escape—the sort of true story of an epic attempt at mass escape from a heavily guarded German prison camp during World War II. I was seven years old when it came out, so I never got to see it in all its full screen glory. I was first introduced to the story when one of the networks—this was way back when there were just three—aired the movie over two nights in 1967.

That was a big event in our house. My parents let me stay up late on two consecutive school nights to watch it. It is actually one of my fondest “warm fuzzy” family memories from my childhood. Mom made popcorn, and Dad did color commentary about what World War II was like. I pointed out that his war was Korea—but he held court nonetheless.

What makes a movie endure and remain popular half a century later? Well, certainly the cast is a factor. I mean, Richard Attenborough, James Garner, David “Ducky” McCallum (how old is that guy?), and the ultimate Mr. “Cool”—Steve McQueen—they surely played a role (pun intended) in the film’s contemporary and legacy success. But there must be more. I once saw a film that had Gregory Peck and Michael Caine in it, and it was a bomb.

It’s got to be the story itself.

The late Don Hewitt, long time producer of CBS’s staple 60 Minutes, was once asked about the secret of the news magazine’s staying power. He replied that the key was as old as the Bible and as simple as four words—“tell me a story.”

It is my experience—as a writer and speaker—that good stories begin with questions—Why? Why not? How? What if?

I am often asked how I came up with the story I tell in Camelot’s Cousin. Well, it began with a question. In September 2011, I was invited to speak about my previous book, The Shooting Salvationist, to a forum at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire. In the audience that evening was a writer who won a Pulitzer Prize for journalism in the early 1970s. His area of expertise was intelligence and the CIA.

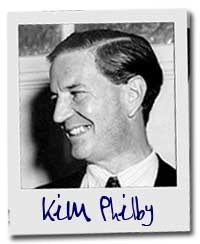

My host that evening invited this journalist to join us for a late dinner. It turned out to be quite an evening. Having always been fascinated by the world of intrigue during the Cold War, I picked this man’s brain. We talked much about the infamous spy, Kim Philby, who had been abruptly asked to leave the U.S. in 1951, under a cloud of suspicion. During our conversation that night the subject of materials he left behind was discussed. Philby had—according to his own memoir published in 1967—buried them in Virginia.

So, I asked the question—what if someone found what he buried? And what if something Mr. Philby planted beneath the Virginia soil pointed to other nefarious people and things?

That was all it took—I was hooked on a story.

[I wrote this blog for VENTURE GALLERIES, a great site about books and authors. -- DRS]

June 10, 2013

Why Did I Decide to Write Fiction? I Hardly Ever Read It ;)

[This blog written for VENTURE GALLERIES, where I will be posting a couple of times a month as part of their AUTHORS COLLECTION--DRS]

So, I decided to write a novel. This might not sound like that big of a deal for a writer, but it turned out to be a major moment in my life. Really.

You see, not only had I not ever written fiction before—I rarely read it.

Why, then, did I decide to write a novel? It was because I had this idea for a story buzzing around in my head for a few years. But also, I had noticed something while writing my first book, The Shooting Salvationist, a true narrative nonfiction story from the 1920s.

I really enjoyed writing the parts of that book where I had to use my imagination to fill in a few blanks to carry the story forward. I never invented dialogue. Everything in quotes in that work comes directly from a newspaper, archived record, published work, etc. In other words, the book is a true story—David McCullough’s kind of narrative history. But as with the works of McCullough and other narrative nonfiction writers such as Erik Larson or Howard Blum (not to mention the late Truman Capote, who pretty much started the genre), a certain measure of creative color is permissible, within narrow and confining limits.

One day in late 2011, I started to write what became Camelot’s Cousin. I wrote about 5,000 words and then put it aside. A few months later, I revisited it and began to move it forward (eventually it reached 105,000 words). And along the way, I discovered some things.

First, I was amazed at the level of research required. I confess to being a research geek—I simply love it. Few things are more fun to me than digging through archival collections, finding obscure old news items on the Internet, or capturing a factoid from a book. The aforementioned Erik Larson calls this process, “hunting detail.”

First, I was amazed at the level of research required. I confess to being a research geek—I simply love it. Few things are more fun to me than digging through archival collections, finding obscure old news items on the Internet, or capturing a factoid from a book. The aforementioned Erik Larson calls this process, “hunting detail.”

But, as a recovering “nonfiction only” addict, I admit to a bias—okay, call it a prejudice. I always thought fiction writers just made stuff up off the top of their heads via a sort of stream of consciousness process. “Real” writers are those who deal in facts and truth, with a passion for accuracy and detail and attribution—or so I thought. But frankly, I found the research elements for Camelot’s Cousin every bit as involved as the process for any nonfiction project I have started or completed.

Of course, my novel is set against the backdrop of actual history, and many of the characters are real, so some historical research was necessary. I actually have a bibliography in the back of the book. But the most demanding research was for the creative/fictional side of things—the things I made up.

For example, several chapters in the book involve the main character spending time in Oxford, England. After I finished the first draft of that section, I ran the pages by a friend in New York—and old editor (he actually discovered Steven King—I mention him in the acknowledgements). He called me one day and asked, “David, have you actually ever been to Oxford?” I told him that I had been to London, but never Oxford (dumb answer).

“Thought so,” he replied. “Okay, here’s what I want you to do. I want you to rewrite that entire section. But first, I want to acquire every episode of the old BBC series, Inspector Morse, about a fictional detective investigating murders in Oxford. Don’t write another word until you’ve watched every episode.”

Sounded like a fun assignment. It was certainly better than “wax on, wax off.” I not only watched all the Inspector Morse episodes, but I decided to watch the entire sequel series, Inspector Lewis, for extra credit –Ah grasshopper (pardon the mixed television metaphor).

My wife was annoyed that I wasn’t spending much time at my desk or computer. Instead, I was in a comfortable chair, watching people with funny accents solve mysteries. “It’s research, Honey—I promise. I’m working here. Really.” That was fun.

When I finally rewrote the Oxford section, I had a database of imagery and dialogue to tap. And I must confess—it was more fun than hanging out in the collections section of a university library, having to wear gloves and never being allowed to write in ink or speak above a whisper—just saying.

Oh—one more thing I discovered via writing my first novel is that I have a new view of fiction. I not only respect it more—I actually read more of it. A lot more.

This old dog learned some new tricks.