David R. Stokes's Blog, page 10

April 1, 2013

Preaching and Prayer in the White House East Room

As the first streaks of dawn quietly announced the arrival of morning on Sunday, November 16, 1969, a 35-year old preacher from Ohio named Harold Rawlings had already been awake for a while after a fitful night of what-could-barely-be-called sleep in a room at Washington, D.C.’s storied Mayflower Hotel.

In a few hours, he would face a crowd punctuated by the most powerful men and women in America, assembled in the most unusual of venues for any clergyman – the East Room of the White House.

Most presidents have likely never read Theodore Roosevelt’s, Nine Reasons A Man Should Go To Church. Among the things TR said was this gem:

Yes, I know all the excuses. I know that one can worship the Creator in a grove of trees, or by a running brook, or in a man’s own house as well as in church. But I also know, as a matter of cold fact, that the average man does not thus worship.

Richard Nixon decided in the first days of his presidency to reconcile the ethic of church attendance with the realities of security and logistics during his time in the White House, by having regular Sunday services in the East Room. Of course, he was criticized for it. Some saw it as political grandstanding and others (many in the clergy) feared Nixon might be setting a trend for “stay at home” worship.

Billy Graham noted, though, that in the early days of Christianity churches met almost exclusively in houses. So, on Nixon’s first Sunday in the White House, Graham shared a sermon, beginning a long run of non-sectarian religious services at 11 o’clock most Sunday mornings.

Reverend Rawlings had received an invitation, via the recommendation of his congressman, Donald “Buzz” Lukens, to bring the message during one of those services. But the preacher had to pay his own expenses to the nation’s capital, something gladly accomplished by his church, Landmark Baptist in Cincinnati, Ohio, where the lanky clergyman shared pastoral duties with his father, the senior minister of the church.

The preacher also had no idea when he accepted the White House invitation that he would be performing his prelatic duties against the backdrop of a city in turmoil.

Pastor Rawlings and his wife Sylvia made their way to Washington, D.C., on Saturday, November 15, 1969, while 250,000 protestors were in virtual control of the city’s streets and parks. The Washington Post headline the next day said, “Largest Rally in Washington History Demands End to Vietnam War.” There was a lingering hint of tear gas in the air and the remnants of torn and burned flags littering the ground. Other flags were prominent and not burned, but they bore only one star and just two stripes—the banner of the Viet Cong (National Liberation Front or “NLF”). The night before, 76 nearby buildings had been damaged, and nearly that many more would experience the same fate that day.

The swarm on Washington had been organized by an outfit called the New Mobilization Committee. This group was the successor to the National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam, which had been part of the infamous Chicago riots at the Democratic Convention in 1968. Basically, it was a leftist mosaic made up of people from Students For A Democratic Society (“SDS”), the Youth International Party (“Yippies”), and assorted fellow travelers.

And though the “festivities” had ended late Saturday night, thousands remained in the streets overnight continuing to shout things like, “Ho, Ho, Ho Chi Minh, NLF is Going to Win!” This made sleep that much more difficult for Harold and Sylvia Rawlings.

The couple enjoyed breakfast in the Mayflower’s restaurant, their waitress discreetly pointing out the famous “psychic”, Jeanne Dixon, who was sitting across the room near the booth where J. Edgar Hoover regularly ate lunch. This brush with celebrity would be nothing compared to the experience awaiting the preacher and his wife when they arrived at the White House.

They climbed a stairway to the second floor and were immediately met by the First Lady, Mrs. Pat Nixon, who invited them into the beautiful Yellow Oval Room, where they sat in Louis XVI style chairs. Tricia Nixon soon joined them, followed a few minutes later by President Nixon, who took Pastor Rawlings on a personal tour of the adjacent rooms, sharing details about their history. Nixon was in a great mood, no doubt bolstered some by the latest Gallup Poll showing that around 70% of Americans gave him high marks, this in the wake of his already famous “Silent Majority” speech a few days earlier.

They then made their way to the East Room, with Sylvia taking her seat next to Mrs. Nixon and Tricia. President Nixon, as was the custom, opened the service, “After a very awesome display yesterday,” pausing briefly for effect, knowing that some would think he was referring to the demonstrations, he continued, “of football, we thought it would be proper to have someone here from Ohio.” Ever the football fan, he was referring to the Buckeyes’ 42-14 win over Purdue.

Pastor Rawlings had been asked to suggest two hymns for the service and did so several weeks in advance, only to be called back by the White House and told, “President Nixon doesn’t know those – could you choose two others?” He did, and the service that day included the majestic strains of “All Hail The Power Of Jesus’ Name,” a song Nixon knew well. A choir from New York Avenue Presbyterian Church sang.

The President then introduced Rawlings, who chose as his theme that day, “The World’s Most Amazing Book.” Many notables were in the crowd of about 350, including Supreme Court Chief Justice Warren Burger, Secretary of State William P. Rogers, Treasury Secretary David M. Kennedy, Labor Secretary George P. Schultz, and United States Senators Claiborne Pell, Mark Hatfield, John Sherman Cooper, Gale McGee, John Williams, and Charles Percy. And the service was broadcast live across the country via the Mutual Broadcasting System.

“If men and women would spend more time in the serious study of the word of God,” said Rev. Rawlings, “earth’s questions would seem far less significant and heaven’s questions far more real.” He then quoted former President Eisenhower, among others. The great man had died eight months earlier and his life and career had intersected with Nixon’s so significantly.

Rawlings affirmed that, “The Bible is not only good for the soul, but also for the body.” He illustrated this point with a moving story about a soldier in Vietnam, Army Private Roger Boe, who after being ambushed found an enemy bullet “lodged in his Bible, just short of the ammunition clip.” The preacher, describing America as “a haven for freedom and peace,” urged prayer, “to make us morally worthy of protection against outward aggression.” He also issued a reminder about praying for the men of Apollo12, at that moment racing through space, “our three astronauts that they might be blessed with safety and good health on their voyage to the moon.”

During a conversation with Harold Rawlings, who is a long-time friend, he told me that following the service Chief Justice Burger told him that his sermon was “the kind of message America needed to hear.”

A reception followed, with President and Mrs. Nixon personally introducing Rev. and Mrs. Rawlings to those filing by. Nixon, though, was at least a little bit in a hurry. He was going out to Robert F. Kennedy stadium that afternoon to see the Redskins play the Cowboys. In fact, this would itself be historic – the first time a sitting President of the United States attended a National Football League game. He was pulling for the home team, but conceded to a reporter that the Cowboys would come out on top, “I think they’ll win because of their running attack.”

But it turned out that the Redskins lost because Sonny Jurgenson threw 4 interceptions – three of them in the fourth quarter. Possibly, the fate of the Redskins that day was a harbinger of things to come that week for Mr. Nixon. The very next day, American newspapers first mentioned something about a massacre in Vietnam at a place called My Lai. And later that week, the President’s nominee for the Supreme Court, Clement Furman Haynsworth, was rejected by the Senate, 55-45.

This just reinforces something else Teddy Roosevelt said about why people should go to church: “In this actual world, a churchless community, a community where men have abandoned and scoffed at or ignored their religious needs, is a community on the rapid down grade.”

March 31, 2013

The Easter Effect

There are moments in time and space when transitory issues fade in significance as things that seem to matter so much are trumped by what really matters most.

Today, as people around the globe gather to remember, honor, and reflect on events that happened some 2,000 years ago in a micro-spot on the world map, it is fitting, I think, to take a departure from the relentless, and at times tedious debate about politics and policies big and small. Let us, for a moment at least (hopefully a life-long moment), focus on a simple, yet profound scenario. One that can be described succinctly and received joyously—it is something called the Gospel.

The word itself comes from the idea of “good news” or “glad tidings,” and is intended to be a divinely directed message of hope. It is a reminder that there is hope, now and in the future. And though we get worked up into a regular lather over issues that polarize people—and I am not suggesting that these issues lack importance—as I read the Biblical record I find it endlessly fascinating that a small group of people, from ordinary backgrounds, and with few natural gifts, could make such a difference in their world and history itself.

They were the first to experience The Easter Effect. They lived, worked, and later died with a sense of fulfillment and joy because they never got over what they knew to be true, having seen it with their own eyes. They were dramatically changed people. We could use the word “converted” to describe it, completely transformed by an encounter with that aforementioned simple scenario involved in the Gospel. The Apostle Paul put it this way:

“Moreover, brethren, I declare to you the gospel which I preached to you, which also you received and in which you stand, by which also you are saved, if you hold fast that word which I preached to you—unless you believed in vain. For I delivered to you first of all that which I also received: that Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures, and that He was buried, and that He rose again the third day according to the Scriptures, and that He was seen by Cephas, then by the twelve. After that He was seen by over five hundred brethren at once, of whom the greater part remain to the present, but some have fallen asleep. After that He was seen by James, then by all the apostles. Then last of all He was seen by me also, as by one born out of due time.” (I Corinthians 15:1-8 NIV)

When he wrote this, and as first century Christians migrated and ministered en route to the uttermost parts of the earth, it was against the backdrop of the rule of Rome. Social, political, and cultural dynamics were arguably a bit more challenging than what we see in America today, but those pioneers of the faith once for all delivered were largely unmoved by what would seem to be a daunting challenge. This was because they grasped the concept that the message of the Gospel was more about redemption than reformation, more about individual salvation than solving social problems, more about a world to come than the world that was—or is.

This is not to say that these souls on fire were indifferent to cultural or political matters, but they knew that ultimate hope and change were never really possible via human means and methods. And when they did pray for those in authority—even those with tyrannical tendencies in Rome—they did so with the seemingly singular goal of desiring to be left alone to live for God:

“Therefore I exhort first of all that supplications, prayers, intercessions, and giving of thanks be made for all men, for kings and all who are in authority, that we may lead a quiet and peaceable life in all godliness and reverence. For this is good and acceptable in the sight of God our Savior, who desires all men to be saved and to come to the knowledge of the truth. For there is one God and one Mediator between God and men, the Man Christ Jesus.” – (I Timothy 2:1-5 NIV)

Like the prayer for the Tsar in Fiddler on the Roof—that he may stay far away—this was a plea for freedom. But it was also a plea for a particular kind of freedom, to be able to live right and model and share the hope of the Gospel.

They were a generation under the influence of The Easter Effect—people who were changed from the inside out and who eventually turned the world upside down (See: Acts 17:6).

Happy Easter—He Is Risen!

March 30, 2013

The Famous Texas Feud of First Baptist Preachers

[As historic First Baptist Church in Dallas, Texas, dedicates its new 130 million dollar home this weekend, here is a look back at a time of rivalry between First Baptist, Dallas--and First Baptist in Fort Worth, Texas]

W.A. Criswell, who for decades led historic First Baptist Church in Dallas, Texas, was the driving force in the decision to keep the congregation in its downtown location, while most other American city churches were fleeing to the suburbs.

When he was a young boy growing up in the northwest corner of the Texas panhandle, he began to feel stirrings in his soul about the call to the ministry. His parents were conflicted, with mother concerned about the boy’s prospects for material success, and father determined that if his boy became a preacher, he’d be the “right” kind.

The elder Criswell was a big fan of a preacher often referred to as the “Texas Tornado”—J. Frank Norris, pastor of the First Baptist Church in Fort Worth. The Mrs., well, her pulpit cup of tea was George W. Truett of Dallas’ First Baptist Church. He was devotional, where Norris was dogmatic. Truett was a unifier, where Norris was a divider. Both preachers were predominately evangelistic, but their methods and mannerisms were as different as night and day.

And they had a famous feud that lasted more than two decades.

Today, Dr. Truett is the better remembered of the duo, but this was certainly not the case when the two First Baptist Churches towered over the variants of Baptist life during the first half of the 20th century. And, although Truett’s legacy is secure, complete with the ongoing success of the Dallas church (a new 130 million dollar facility), as well the association of his name with his alma mater, Baylor University—at times the ghost of J. Frank Norris has haunted the Southern Baptist Convention.

For much of the 1920s and 1930s, the Fort Worth church was the larger of the two. In fact, it was in many ways America’s first megachurch. And Norris’ name was better known than Truett’s outside of Baptist circles, due largely to his penchant for sensationalism and controversy. After all, a preacher indicted four times by county grand juries during his ministry, once for perjury, twice for arson, and once for first-degree murder, with high-profile trials accompanying, would tend to get ample media coverage.

Even inside the denominational walls of the Southern Baptist world, Norris’ name was as well known as Truett’s, though not out of affection. Initially noticed favorably by George W. Truett and other leaders as a young and upcoming minister, even being given a plum job as editor of the Baptist Standard at the tender age of 30, leaders soon soured on J. Frank. They began to notice the young preacher’s apparently unbridled ambition, not to mention his “Haydenite” tendencies.

Dr. George W. Truett

This was a reference to a schismatic group of Southern Baptists in the latter part of the 19th century, led by one Samuel Hayden, and given over to the kind of “watch dog-ism” and divisiveness that would later characterize the emergence of Baptist Fundamentalism in the 1920s.

The growth of Fundamentalism in its early days following the end of World War I played out as a veritable tale of two preachers in the Southern Baptist world. Norris became an early champion of the movement, while Truett shied away from its more tenacious tendencies. It was this reluctance by Truett to engage perceived error that provoked J. Frank Norris’ wrath. And when Norris took on the great school where he and Truett had trained for the ministry (though more than 10 years apart), Baylor in Waco, Texas, the gloves were off.

J. Frank Norris conducted a celebrated witch-hunt, investigating the faculty of the Baptist school and looking for doctrinal anemia, especially when it came to the hot-button-issue-of-the-day: evolution. This all occurred against that backdrop of the Roaring Twenties, where the issues aired out at the Scopes Trial in Dayton, Tenn., were being debated around the country. Norris was the chief inquisitor, a man who was responsible for many notable faculty resignations at Baylor and elsewhere around the country.

And along the way, some of the brethren came up with a little poem, one that would be whispered and laughed at when preachers got together to chew the ecclesiastical fat:

“And what to do with Norris, was a question broad and deep.

He was too big to banish, and he smelled too bad to keep.”

But it was not at all funny to George W. Truett. It was personal, because Norris had made it so. By this time, the Fort Worth preacher had become what has been described as “Truett’s chief rival for the soul of Texas Baptistdom.” In 1924, the Baptist General Convention of Texas, with the full backing of Dr. Truett, ousted Norris and his church. Norris was waging all-out war against what he sarcastically called “The Baptist Machine.” His personal tabloid, called the Searchlight, had a circulation of more than 50,000 by this time, and it was commonplace to see Truett and other Baptist leaders described as “infidels” and worse in its headlines and pages.

Also around this time, it became part of the job description of deacons at Truett’s church to be watchful every Sunday morning, on the look out for anyone bearing anything resembling a telegram. Norris would regularly try to insert an agent provocateur into the Dallas church crowd, someone who, with the skill of an experienced process server, would get a choicely worded note into Dr. Truett’s hand—one designed to rattle the preacher with words such as: “How can a man like you presume to occupy a Baptist pulpit?”

Norris and Truett were not only different outside the pulpit; they were a study in contrast in it, as well. Norris tended to use outrageous and aggressive body language to aid his voice, complete with flailing arms, kicking feet, and even tossing the occasional coat to the floor. Truett, on the other hand, let his voice do all the work, one that could, it was said: “leap from a whisper to a shout in the utterance of a syllable.”

Norris’ ways caught up to him, at least temporarily, in 1926, when he shot an unarmed critic to death. The story became national news as Norris faced the Texas electric chair, in the biggest and most sensational trial of that decade in a Texas court. This is the story I tell in my book, THE SHOOTING SALVATIONIST: J. Frank Norris and the Murder Trial that Captivated America.

Dr. J. Frank Norris

Norris was acquitted and resumed his ministry, one that would lead him to pastor two churches, First Baptist in Fort Worth and Temple Baptist in Detroit, Mich., simultaneously for 16 years (1934-1950), boasting a combined church membership of 25,000. But the murder trial rendered him a virtual pariah among Southern Baptists, leading Norris to eventually start his own “independent Baptist” movement, one that flourished long after his death in 1952. Ironically, elements of the independent movement and the SBC interact with increased regularity these days, with the late Jerry Falwell’s Liberty University being the most enduring legacy of Norris’ independent Baptist vision.

George W. Truett died in July of 1944 after a yearlong illness. The search for a new pastor for First Baptist in Dallas, led them to 34-year old, W.A. Criswell. The new pastor—though this was likely not noticed at the time—was in some ways a composite of Truett and Norris, though certainly without the latter’s darker qualities.

And one day, after Criswell had been filling George W. Truett’s shoes for nearly eight years, W.A. glanced out the window of his office a saw an old man sitting there. He buzzed his secretary and asked how long the man had been waiting, “Well, he’s been there for quite a while, Dr. Criswell. He looked like a bum to me, and I wasn’t sure you’d want to be disturbed,” she said.

But Criswell recognized the old man, and he was no bum—it was J. Frank Norris.

Dr. Criswell received his visitor, embraced him, and they chatted about life and ministry. Norris died a few days latter.

[This article is a revised version of one written by the author for Preaching Magazine]

March 29, 2013

Have Some Evangelicals Left Their Bibles Behind?

In January of 2009, there was a furor over President-Elect Barack Obama’s selection of California mega-church pastor Rick Warren to pray at his first inauguration. Four years later, another mega-church pastor, Louie Giglio from Atlanta, was awkwardly uninvited to pray at Mr. Obama’s second inaugural.

Four years turned out to be a long, long time.

On the surface, playing the Warren card back then appeared to be a masterstroke by Obama – one that further demonstrated impressive political skills, the kind that took him from a backbencher in the United States Senate, to the highest office in the land.

A day or so after the election in November 2008, I was asked by someone about what Mr. Obama would do to prepare for his administration. I replied that I thought he would demonstrate significant savvy by – at least for a time – ignoring the clamorous pleas from core constituencies, the kind of people who will support and vote for him no matter what. And I suggested he would reach out to those who view him with fear – or at least mild suspicion.

That’s pretty much what number 44 did—at first. He confounded those who voted for “real change” by putting together a third Clinton term on most things, and a third Bush term on issues relating to the war in Iraq.

Evangelicals – especially younger ones – played a key role in Barack Obama’s ability to counter clear problems with his own church and pastor (remember Jeremiah Wright?). They also, in many cases, overtly campaigned for him, his decidedly non-evangelical views on abortion and other traditional values issues notwithstanding.

Mr. Obama was viewed by many evangelicals as a new kind of politician—someone who could bridge the gap, or reach out, or maybe begin a dialogue. Pick your warm fuzzy mantra.

Then the President’s position “evolved,” to use an interestingly pregnant term.

Evangelicals, those who take the Bible and their faith seriously, need to be reminded that when it comes to issues like gay marriage – even abortion – there is not really any middle ground with those on the left, even the so-called Christian left.

Rick Warren spent a great deal of time and money, investing his ministry in initiatives that are outside of the normal evangelical box. He worked tirelessly in Africa and elsewhere on the issue of AIDS – and cultivated a compassionate and understanding persona when it came to dealing with issues and ministry challenges stemming from same-sex attraction.

What Warren has not done, nor will he ever do, is to reach the point where he declares that homosexual behavior is not sinful. He will not do this because he is a Biblicist.

No matter how “understanding” evangelicals try to be, or how sincere some are, to open a dialogue with same-sex marriage advocates and activists, there can be no real rapprochement without the willingness to change the way the Bible is read and interpreted.

And that would be an evangelical bridge too far.

Conservative evangelicals possess a belief-system rooted in a movement popularized nearly 100 years ago and that reached its peak at the mid-point of the roaring twenties. Fundamentalism, part dogma, part culture, part reaction to culture—and in large measure driven by several key and dynamic personalities—was at its high water mark as a social phenomenon. Though certainly no fan, in fact a persistent critic, of the movement, H. L. Mencken, the caustic journalistic sage of Baltimore, observed its clear influence, writing at the time: “Heave an egg out of a Pullman window, and you will hit a fundamentalist almost anywhere in the United States today.”

From 1910-1915 a series of twelve books was published and widely distributed to conservative-minded Christians around the country under the title The Fundamentals. A year before the first edition appeared, a wealthy Californian had been inspired, listening to a sermon by Chicago preacher, A.C. Dixon, to “bring the Bible’s true message to its most faithful believers.” Very soon he developed the concept for the publishing of “a series of inexpensive paperback books, containing the best teachings of the best Bible teachers in the world.” After The Great War (1914-1918), a movement took root, one based on the ideas in The Fundamentals, and that would transcend “various conservative Christian traditions.”

During the 1920s, most of the great protestant denominations experienced internal convulsions over issues raised – sometimes vociferously – by fundamentalists in the ranks. Of particular concern to some was the growing tendency on the part of religious “liberals” to question long-held dogmas of the faith.

Opposite the fundamentalists were the “modernists” – and they openly challenged things seen as precious to true believers everywhere. Harry Emerson Fosdick – a leading modernist protestant pastor – suggested an alternative narrative for the virgin birth. Jesus was likely (in his thinking) fathered by a soldier. The scriptural story could not possibly be true. And the resurrection – well, come on now – really? Rising from the dead – I mean, that’s just too incredible for “modern-intelligent” minds to accept.

And everything depended on what a person believed about the Bible itself.

To fundamentalists, it was the inspired Word of God. By this they meant the “verbal-plenary inspiration” of scripture. In other words, the “words” were inspired – and the book itself was in its entirety. And when it came to interpretation, fundamentalists opted for what they called, “the historical-grammatical” method – what the words meant in context and back then (think: “strict construction” of the U.S. Constitution – what did the founders and framers mean?).

Why is it important to know this? Because the evangelical movement grew out of fundamentalism. Led by people like Billy Graham and Harold John Ockenga – and schools like Moody Bible Institute and Wheaton College – the idea was to keep the solid “doctrinal” stuff – Biblicism and the centrality of Jesus Christ and his “Finished Work,” while moving away from the strident, often belligerent, methods of the earlier generation of fundamentalists.

A new-breed of evangelical “whiz kids” took the religious Model-T of the fundamentalists and popularized it to a post-war/Cold War nation. They even had a saying in the Youth for Christ movement in those days (where Graham got his start): “Geared to the Times, but Anchored to the Rock.”

Rick Warren and millions of others today remain faithful to these ideas. Though attempts are made to build bridges – to reach out – it is solely for the purpose of bringing people to a relationship with Jesus.

Though I hesitate to put words in Rick Warren’s mouth, or speak definitively as to where he stands – I am quite confident that his view of scripture is very much in line with the 1950s evangelicals – even the 1920s fundamentalists. It is a high view of the Bible – inspired of God, interpreted carefully, and applied personally.

This is a view commonly shared by conservative evangelicals across the denominational landscape. And it is why some evangelicals need to face the music. No matter how much you try to love, reach out, dialogue, and build bridges, the other guys are not going to be happy short of the abandonment of the Bible as a serious document relevant to our times.

Unless evangelicals are willing to say that the Bible does not call homosexual behavior sinful, no amount of posturing will change anything.

It is sort of like the Israeli-PLO land-for-peace narrative. It will never work because the PLO does not think Israel should exist. Conceded acreage will not bridge that chasm.

Nor will “reaching out” assuage those who believe that anyone who takes the Bible seriously on the matter of homosexuality is, ipso facto, a bigot filled with hate.

The Apostle Paul knew a thing or two about people and bridge building. He told the Corinthians that he was always willing to reinvent himself to a point in order to connect with others. But the connection he desired with others was designed to bring them to a place of faith in Jesus.

Many evangelicals are still firmly, optimistically, and sincerely on the Barack-Bridge. When will they realize that in order to cross it completely en route to the new promised land of change, they will have to lighten their load and leave some stuff behind?

And at the top of the heap of discarded stuff there will be a lot of Bibles.

February 15, 2013

Nixon at 100–Still Fascinating

[This article written for TOWNHALL.COM--to read it at that site, CLICK HERE]

Why do I still find Richard Nixon so fascinating? After all, my political views on many matters are arguably more conservative than his were and would likely be if he were alive and politically engaged today. I think my interest has always flowed from what I admired about the man himself. A giant American historical figure, Mr. Nixon was on five national electoral tickets—a feat matched only by Franklin Roosevelt.

This weekend, the Richard Nixon Centennial Special Exhibit opens at the Richard Nixon Presidential Library in Yorba Linda, California. It was my privilege to provide the narration for the exhibit’s video: Patriot. President. Peacemaker.

I grew up as a history geek and remember running home at the age of 12, after an early school dismissal on January 20, 1969, to watch Nixon’s inauguration as 37th President of the United States.

More than a year earlier, as Christmas approached in 1967, Richard M. Nixon, private – though prominent – American citizen, went through a period of soul searching. The sweep of national and international events, as well as extraordinary personal experiences, weighed on his pensive mind. He was emerging from a wilderness period, the kind he would later quote historian Arnold Toynbee describing as the, “temporary withdrawal of the creative personality from his social milieu transfigured in a newer capacity with new powers.”

To some, the term Nixonian refers to charting a more moderate (or as Mr. Nixon would likely have described: “centrist”) path. This is certainly an accurate definition as far as it goes. But to me, Nixonian is more than a mere political nomenclature indicative of a body of tactics and strategy.

To me, Nixonian is a metaphor for persistence.

Richard Nixon was the embodiment of rugged determination. He personified what nineteenth-century Scottish essayist Thomas Carlyle once wrote: “Permanence, perseverance and persistence in spite of all obstacles, discouragement, and impossibilities. It is this, that in all things distinguishes the strong soul from the weak.”

And in those waning days of 1967, Mr. Nixon was poised to mount another campaign for our nation’s highest office, though he had not actually won an election in more than a decade. He had lost a breathtakingly close race for the presidency in 1960. Then, in an awkward comeback attempt, was rejected in 1962 by California voters in a race he was encouraged to run by former President. Immediately thereafter, the prevalent wisdom was that Nixon was a loser, and that his political obituary had already been written.

But the so-called experts were all wrong. Nixon was down, but certainly not out. In so many ways, as was the case with Winston Churchill, the days described by most biographers as his wilderness period, were among his best. Persistence, determination, patience, reflection – these were the future president’s watchwords as the nation was torn by crisis, a horrific presidential assassination, an expanding and confusing war in Southeast Asia, and national leadership marked by the hubris of some who apparently actually thought they were “the best and brightest.”

On the eve of 1968, a year that would be marked by tumult and division, many were beginning to take another good long look at Richard Nixon. At the time, Lyndon Johnson’s hold on the office was tenuous. LBJ would bow out for good by the end of March. It was shaping up to be a very interesting political season.

What was happening was akin to a political story in Great Britain a generation earlier, when a man thought to be a has-been rose again to lead at a perilous moment. Signs began to pop up all over London in 1939 bearing the words, “What Price Churchill?” Winston Churchill would so often say, “KBO,” which meant: “Keep Buggering On.” I am not sure if Richard Nixon ever said it exactly that way – but he clearly understood the meaning.

Citizen Nixon had a long talk with his family on Christmas Day in 1967 about whether or not he should run again for the White House. It was a subdued moment for all of them – but especially Nixon, himself. His mother, Hannah – beloved by her son, and a source of strength and encouragement through the years – had passed away that previous September. Among her last words to him were: “Richard, don’t you give up. Don’t let anybody tell you, you are through.”

As Nixon’s mind reflected on his mother and her inspiring words, he remembered the simple, yet profound, funeral service at the Friends Church in East Whittier, including the moving eulogy shared by Billy Graham. Possibly, this is when he decided to send a plane to pick up the evangelist, inviting the preacher to spend some time with him at Key Biscayne a few days hence.

Graham was ill and had cancelled all of his engagements. But he likely recalled a moment a few years before – in the autumn of 1963 – when John F. Kennedy had invited Graham to ride with him in the presidential limousine and talk at the White House. Graham was sick that day too, and begged off, asking for a rain check. But before such a conversation would ever take place, the president traveled to Dallas. Likely, Billy didn’t think twice about accepting Nixon’s invitation.

The politician and the evangelist walked Key Biscayne’s beach on New Year’s Eve in 1967, and the conversation was about whether or not Nixon should run. Graham encouraged his friend that day arguing: “You are the best prepared man in the United States to be president.”

The preacher was right.

Among Nixon’s favorite lines to quote were those from Theodore Roosevelt’s “Man In The Arena” speech. But Richard Nixon also exemplified what Kipling wrote about in “IF”: “If you can force your heart and nerve and sinew to serve your turn long after they are gone, and so hold on when there is nothing in you except the will, which says to them: ‘Hold on’…”.

That’s Nixonian.

February 12, 2013

Richard Nixon Centennial Video and Exhibit

[NOTE: It was my privilege to do the voice over work for the video that will be premiered at this event. I also did the voice work for video last year marking the centennial of Mrs. Pat Nixon’s birth. – DRS]

Tricia Nixon Cox, daughter of the 37th President of the United States, and David Ferriero, Archivist of the United States, will lead the festivities at the official opening of the Richard Nixon Centennial Exhibit, Patriot. President. Peacemaker. It will take place at the Nixon Library in Yorba Linda, California, on Friday, February 15.

The 11AM ribbon cutting ceremony and official opening tour is followed by a Noon Luncheon with Nixon family, friends, and former White House officials.

This highly visual story-teller presentation will feature the most important and influential aspects of the 37th President’s life. Guests will “walk in RN’s shoes” as they’re guided through the five key chapters that define President Nixon’s his legacy, How American, In the Arena, Creating a Just Society, Peacemaker of His Time, and Global Elder Statesman.

For more information about this event, CLICK HERE.

December 12, 2012

When School Teachers Act Like Bullies

I grew up in the downriver suburbs of Detroit, Michigan. Most of that time in a community (first a township, then a city) called Taylor—a place in the news recently for having closed its public schools in the wake of a massive wave of teachers calling in “sick.” However, these “educators” apparently made a nothing-short-of-miraculous group recovery immediately after their illness laden phone calls and quickly made their way en masse to the state capital in Lansing to join the angry mob protesting the recent legislative move to successfully make Michigan the nation’s 24th “right to work” state. This was, to sort of borrow a cliché from Vice President Biden, a big deal.

By their participation in this particular protest, these Michigan educators acted like bullies—hardly their best moment. It seems that the whole union thing brings out the worst in some people—even those with enough education to presumably know better.

How will it be possible for some of these same teachers to, in the next few days after returning to the classroom, break up a fight involving one kid bullying another? You just know that some wise guy kid, who’d fit in the cast with Ralphie in The Christmas Story, will talk back to the teacher, saying something like: “Yeah, well I saw some of you teachers do worse stuff up in Lansing than I’m doing to Billy! Besides, he deserves to be pushed around, it’s the only way I can intimidate him.” The teacher on the receiving end might then smile—missing the irony of the situation—and feel proud that this student knew how to use the word “intimidate” correctly, then wonder if the kid knew how to spell it. [Read the full article at TOWNHALL.COM]

November 26, 2012

Lessons from a polarizing case 65 years ago still resonate today

[Written for EXAMINER.COM]

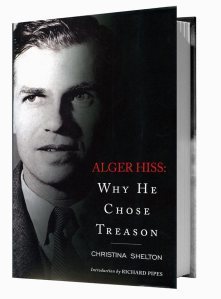

In her new book, Alger Hiss: Why He Chose Treason, Christina Shelton, a retired U.S. intelligence analyst, refreshes our memory not only about the famous Hiss espionage case itself, but why it indeed still very much matters:

The story doesn’t go away, because it has become a symbol of the ongoing struggle for control over the philosophical and political direction of the United States. It is a battle between collectivism and individualism; between centralized planning and local/state authority, and between rule by administrative fiat and free markets…

Hiss firmly believed in a collectivist political ideology; he believed government was the ultimate instrument of power for solving problems and that the U.S. Constitution should be bent or bypassed to support this view. Hiss put his political belief into practice in his support for Communism and loyalty to the USSR, a state where government authority and power were not limited by the rule of law—in fact it would brook no limit.

It was high political drama more than six decades ago—controversial and polarizing. A Harvard trained and highly ranked member of the Federal Government charged by a self-confessed former Soviet spy of being a partner in those very same nefarious enterprises.

On the one hand there was Whitaker Chambers, the somewhat frumpy-looking accuser, a man who had wandered in from the darkened cold years before, having seen the sinister reality behind the propaganda-driven hope and change promised by Communism. Then there was this other guy named Alger Hiss with poster-child-for-success looks, brains, friends in very high places, and a killer resume with seemingly endless references.

Add to that mix a committee in the House of Representatives increasingly dominated by a young Congressman named Richard Nixon who was quickly climbing a ladder to somewhere—and no Hollywood writer or gifted novelist could devise a more compelling story. Along the way we learned about microfilm squirreled away in a pumpkin on a Maryland farm, one man’s dental challenges, and a President of the United States talking about something called a “red herring.”

The story simply won’t go away—nor should it. It contains the DNA of our current national political discussion and cultural divide. Ask people about the Hiss case today and many will predictably give you a deer-in-the-headlights stare. But those old enough to remember, or who have demonstrated a cultivating interest in the political history of our country for the past hundred years or so, tend to quickly reach animation. “Hiss was smeared,” or “Chambers was right,” or my favorite: “Well, that was just McCarthyism at its worst.”

Never mind that Senator Joe McCarthy didn’t even begin to make a name for himself until after Alger Hiss’s conviction on a couple of counts of perjury.

But as the saying goes—“Just because you’re paranoid doesn’t mean they aren’t out to get you.” And with the Hiss case it took years for a preponderance of evidence to come out proving that Whitaker Chambers was right and that Alger Hiss lied. He was a traitor and perjurer. And it still matters today, not just because of the idea of finding out the true story but because the philosophies the two men represented at the time are alive and well and every bit as distinct and diametrically opposed as the Tea Party is from the group purporting to Occupy Wall Street.

Even while denying his guilt throughout his life (he died in 1996 at the age of 92), Mr. Hiss maintained a steadfast belief in the liberalism behind all the manifestations of the New Deal. And this remains the salient talking point—the very real connection between the “progressive” political machinations and actual Marxist thought and methodology. “What Is To Be Done” gave way to what has been done. This is the story of American political liberalism from the heady days of the New Deal to the conjured euphoria of “Yes, We Can.”

Whitaker Chambers, who died in 1961, never lived to see the fall of Soviet communism. In fact, he truly believed that it would never happen and that when he left communism to embrace the ideas and ideals of American freedom he was leaving the winning side for a losing cause. We know that he was wrong—at least in the short run. Having read his wonderful political tome, Witness, several times, I often wonder what Chambers would have made of the events of the late 1980s and early 1990s.

Yet, to sort of quote Ronald Reagan: “Here we go again.”

These days, the “constant vigilance” consistently needed to perpetuate liberty in the face of what often seems to be humankind’s default affinity for a clueless slouch toward tyranny (weeds grow naturally, flowers take work), seems to be in dangerously short supply. The Hiss case would be a great story for all Americans to revisit every few years—as a caveat and catalyst. Christina Shelton’s book is a great place to start. She reminds us that, “Hiss has become emblematic of the ideological divide that continues to this day in the United States…Hiss’s advocacy of collectivism and the need for government control over society and his support for international policies ahead of national security interests still resonate today.”

Toward the end of the book, Shelton tells the story of Vladimir Bukovsky, a man who spent a dozen years in Soviet prisons and labor camps as a dissident. He reflectively compared the former USSR and the European Union (EU), where “nationalism is suppressed in an attempt to establish a socialist European state.” He summarized his comments with words of warning:

“I have lived in your future and it didn’t work.”

November 24, 2012

New Novel views Kim Philby through the Looking Glass

[This review written for EXAMINER.COM]

Harold Adrian Russell Philby, better known by his prescient nickname, “Kim,” continues to fascinate writers. Having falling prey to this compelling interest myself with my own research and story, I recall what the wife of a famous writer (someone who actively covered the Washington “spy” beat for many years back in the day) once told me when I shared my interest in all things Philby. She called it an obsession-inducing black hole.

She understated the case.

So I waited for the latest offering from skilled espionage-stuff writer, Robert Littell, with great anticipation.

I wasn’t disappointed.

The recently released novel is called Young Philby. The narrative is voiced by several characters, real people who interacted with Kim Philby throughout his journey from naïve Cambridge student idealism to full-fledged treachery as one of the most notorious Soviet agents in history. He was a man addicted to what one biographer called “the drug of deceit.”

Along the way in the pages of Littell’s interpretation of Kim’s life, we witness his (presumably) theory about Philby’s development as an espionage agent. We learn about a key recruiter, an early love interest, and the order of things with relationship to the other well-known Cambridge spies: Guy Burgess, Donald MacLean, and Anthony Blunt.

Littell’s chronology when it comes to the order of recruitment seems to be one of the most fictional aspects of Young Philby, not fitting with the actual history of what happened. But then again, his ultimate speculation in the book about Philby’s real agenda and loyalty is, as well, clear fiction—compelling fiction—but fiction nonetheless.

A good book from an excellent author who knows his genre—Young Philby is a quick read that will linger in your mind.

November 21, 2012

Forgotten Jewish Hero of Thanksgiving

[This article appears at EXAMINER.COM]

Our national Thanksgiving narrative is rich with stories about proclamations, gatherings, meals, traditions, football, and of course, the obligatory pardoning of a turkey by the president of the United States. Schoolchildren rehearse that day long ago when the Plymouth pilgrims broke bread. We note famous things men named Washington and Lincoln said.

But did you ever hear of Gershom Mendes Seixas? He is one of America’s forgotten heroes.

We hear much these days about our “Judeo-Christian” heritage and its early and enduring influence on our culture. A look back at the founding era of our nation reminds us, however, that only about 2,500 Jews actually lived in the colonies in 1776. Usually those of us who speak of that early dual influence are referring to the Christian Bible with its Jewish roots.

But pointing this out is not to say that Jews were not active and represented during the colonial and founding periods. Quite the contrary. And Gershom Mendes Seixas is a case in point. Described as “American Judaism’s first public figure,” he was appointed, in 1768, chazzan of New York’s Congregation Shearith Israel – the only synagogue serving the city’s approximately 300 Jewish residents.

He was just 23 years old at the time. Largely self-taught in the Talmud with much help from his devout father, he never actually became an “official” rabbi. In fact, it would be several decades before a rabbi was ordained in America.

Seixas was the first Jewish preacher to use the English language in his homilies. He was a gifted teacher and tireless worker. And when it came to the American Revolution, he was a patriot – as demonstrated by his actions while the colonies were struggling to actually realize the independence that had been recently proclaimed.

His synagogue, like much of the greater public, was somewhat divided on the issue of independence. But Seixas used all of his persuasive skills to convince his congregation that they should cease operations in advance of the approaching British occupation of the city, during the early days of the conflict.

He fled to his wife’s family home in Connecticut, carrying various books and scrolls precious to the synagogue for safekeeping. In 1780, he accepted the leadership role at a synagogue in Philadelphia, where he became an outspoken cultural voice regularly calling on God to watch over General Washington and the great cause.

When the war ended, he was invited back to resume his work with Congregation Shearith Israel in New York. He returned with the books and scrolls to serve from 1784 until his death 32 years later.

When George Washington was inaugurated as the first president of the United States on April 30, 1789, Seixas was asked to participate as one of the presiding clergyman. This was certainly an act of gratitude by Washington for the preacher’s stalwart support during the war. It was also, though, an expression of Washington’s thinking about the importance of religious freedom and diversity in the new nation.

Later that year, as the nation set aside Thursday, the 26th of November, the date so designated by the president for Thanksgiving, Seixas preached a sermon to his New York congregation. His Thanksgiving Day message was based on a text from the Psalms where it talks about how King David had “made a joyful noise unto the Lord.” Seixas told his listeners that they had much to rejoice about – “the new nation, its president, and above all, the new constitution.”

Warming to his theme, he reminded them that they were “equal partakers of every benefit that results from this good government,” and therefore should be good citizens in full support of the government.

Beyond that, they were encouraged to conduct themselves as “living evidences of his divine power and unity.” He further admonished them “to live as Jews ought to do in brotherhood and amity, to seek peace and pursue it.”

As the nation prepares to celebrate Thanksgiving next week, Gershom Mendes Seixas’s sermon is every bit as relevant to all of us 223 years later.