David R. Stokes's Blog, page 3

September 11, 2015

Fourteen Years Later, Are We Still Vigilant?

Fourteen years after the attacks on Sept. 11th, we must remember. But even more, we must be vigilant.

Fourteen years after the attacks on Sept. 11th, we must remember. But even more, we must be vigilant.

By the autumn of 1944, and in the wake of the very successful landings in Normandy the previous June, Allied troops and commanders in the field, and civilian authorities in Washington, D.C. and London, were confident of victory in Europe. It was just a matter of time. In fact, as our forces moved like a juggernaut across France and into Belgium en route to the Rhine and Germany itself, the Nazis were in full-scale retreat, ceding back territory they had aggressively devoured four years earlier. There was even some talk – and it was surely well received – that some of our boys might be home by Christmas.

People had been crooning about it in a popular song for more than a year.

But all that changed when the Germans launched a massive, unexpected winter offensive that December, and a fierce conflict known famously to us as the Battle of the Bulge disabused the Allies of the notion of an expeditious victory. The war was by no means over and the enemy not at all vanquished. This brings to mind a musing from the mind of the great philosopher Yogi Berra, when he said: “It aint over til it’s over!”

You see, while many were prematurely preoccupied with postwar dreams, the good guys were given a brutal, bloody, and costly reminder that the ravages of war are ever possible until an enemy has actually been completely defeated. Three years after the attack on Pearl Harbor, it was pretty easy for Americans to remember what had happened without fear, because the threat was no longer there.

Have you ever watched a movie where the bad guy gets away at the end or enough loose ends are left hanging that you just know the producers are going to make a sequel? Well, our enemies have been longing for just that. Whether or not they can do it, or will, is, of course, a fair and open question. But for anyone to suggest that such a thing can never happen again is not only ludicrous; it is perilous.

Have you ever watched a movie where the bad guy gets away at the end or enough loose ends are left hanging that you just know the producers are going to make a sequel? Well, our enemies have been longing for just that. Whether or not they can do it, or will, is, of course, a fair and open question. But for anyone to suggest that such a thing can never happen again is not only ludicrous; it is perilous.

I certainly think that this anniversary of that horrific day in 2001 should be remembered – but not as a long ago, of a different time and place, event. It must be remembered in the way a Marine on Guadalcanal would have remembered Pearl Harbor in late 1942, or as an Army Ranger would have while scaling the cliff at Ponte Du Hoc, two years later.

This is a holy day in the sense of bearing witness to the terrible loss of life and the noble and heroic actions of so many in their diligent response. There should be a fervency attached to it all. The armor of war should not be put away abroad, nor should the home front be lulled into ominous complacency by political distractions or naïve pronouncements.

The threat is still there. It will not go away by ignoring it anymore than a cancer in the body will. It will not go away by giving it a new name – or no name. It will not go away because we have “smarter” people in charge who supposedly never overreact to crises and keep their heads when all others are losing theirs.

The threat is still there in spite of the fact that there is a systematic undermining of our intelligence capacities in the nation, born of a petty and cynical desire for political gain. We are tying the hands of people who are charged with helping to keep us safe.

The chief role of government is to protect us and keep us free. Instead we live in a time when all the energy in the executive and legislative branches seems to be directed at creating a society of dependent sheep. We’ll be fed, burped, bandaged, and entertained – until we wake up one day and face the sad news that something bad has happened again via the hands of an enemy we have ignored for too long.

There is still a war on. It is a driven by Islamism – a pernicious ideology that uses religion as a pretext for world domination. There are very bad people out there – and here at home; people who despise us, our constitution, and our way of life. They must smile and roll their eyes as they watch us try to wrestle with other issues, just as long as we don’t look too closely at what they’re doing.

But we hear less and less about it. Oh, occasionally a great communicator makes an offhand remark related to such a conflict, but usually only in the context of reminding us how sad it is to have wasted all that money “over there” when we could have used it to make everyone healthy and happy here at home.

In a time of war, you don’t make your side safe by marginalizing the conflict, minimizing the threat, or demoralizing those who are charged with crucial responsibilities.

In the century before the birth of Jesus Christ, a Syrian man named Publilus Syrus, who became popular in the days of Julius Caesar as a mime and actor, was known for his maxims, and many survive to this day. Among the best was this:

He is most free from danger, who, even when safe, is on his guard.

In July of 1927, the New York Yankees were on the road and well on their way to one of the greatest seasons ever experienced by a baseball team. The biggest crowd drawn that month at their famous stadium, however, had nothing to do with baseball. It was the scene of a boxing match between two contenders for the heavyweight title: Jack Dempsey and Jack Sharkey.

Dempsey, of course, had already been a legendary champ, only beaten the year before by savvy boxer and bookworm, Gene Tunney – the smartest guy ever to hold the title. This fight was to see who would face Tunney next. And by all accounts Sharkey took the battle to Dempsey for several rounds, cutting him up, and beating him to the punch.

So Dempsey went to work on the body and some of the punches strayed low – Okay several of the punches were south of the border. And at one point Sharkey turned to the referee to complain. At that moment, while Sharkey was looking at the official, Dempsey hit him with what he later referred to as the best punch he’d ever thrown.

It was over. Poor Jack Sharkey. He forgot the most important rule.

It was over. Poor Jack Sharkey. He forgot the most important rule.

Protect yourselves at all times. – DRS

July 2, 2015

Was Kennedy’s Close Friend a Soviet Spy?

[Review by CHIP ETIER]

“Don’t let it be forgot

That once there was a spot,

For one brief, shining moment

That was known as Camelot.” — Alan Jay Lerner

Mention “Camelot” in a group setting such as a cocktail party or church social and inevitably one or more of those present will think of, and perhaps mention, Jack and Jackie Kennedy.

So where were you in 1962?

October specifically.

Were you doing the old “duck and cover” thing? Were you stocking up the bomb shelter?

Were you doing the old “duck and cover” thing? Were you stocking up the bomb shelter?

If you weren’t around in 1962, ask an older family member. Many baby boomers were in elementary or middle school. John F. Kennedy was in the White House. Castro was in Cuba. Russian missiles were in Cuba, too. Kruschev was in hot water. The world was in shock.

How could it be possible that a Russian spy could have penetrated the innermost sanctums of the United States government? Such a breach in security would have given the Kremlin accurate and detailed information about Kennedy’s plans for handling the Cuban missile crisis.

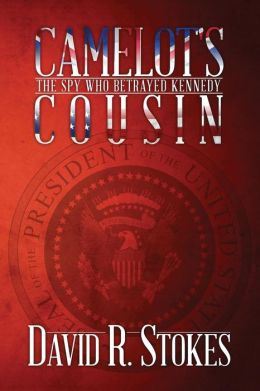

Author David Stokes most recent work of fiction, Camelot’s Cousin, offers readers an engrossing tale based upon circumstantial evidence to support that premise. Additionally, we see the possibility of another conspiracy theory to explain JFK’s assassination.

Stokes has a good story and he tells it well. The narrative comes across as conversational, which is a pleasant change from the business like detachment of most omniscient story tellers.The protagonist is a radio talk show host (an amalgam of contemporaries Stokes knows in real life) and his entourage of associates from work. Their adventures put them in harm’s way when they unwittingly attract the attention of none other than Vladimir Putin himself, his band of spies and seemingly inept hit men. Templeton Davis, the on-air personality, has an unquenchable desire for all things related to spies and their history. This desire is piqued by a discovery made on the farm of one of his support staff. His investigation sparks a series of untimely deaths. Who’s dying? The people he seeks out to help with his project.

Can former members of the OSS, the CIA, and the KGB ever really retire? Stokes delivers with a page-turner that could easily be non-fiction — if you believe in conspiracies.

Camelot’s Cousin is available at Amazon.com, Barnes & Noble, and more. Click HERE for details.

AUTHOR INTERVIEW:

Author: David R. Stokes

Synopsis: When a Dad tries to dig a hole in his Northern Virginia yard to bury the remains of the family pet, he chances upon something buried years before-a mysterious briefcase. Its contents include a journal with cryptic writing. The father turns to his friend-and boss-Templeton Davis, a former Rhodes scholar and popular national radio talk show host, for help figuring out what he’s found.

They soon realize that they are in possession of materials that were hidden more than 60 years earlier by a notorious deep cover agent for the Soviet Union. And buried with the materials were clues to a great last secret of the Cold War-the identity of the most effective spy in the history of espionage.

Long a mere footnote in history, the story of this man’s treachery reaches the pinnacles of power and geopolitics. It’s a story that begins just before the Second World War breaks out and reaches the depths of the decades-long stand off that followed.

After reading Camelot’s Cousin, I couldn’t wait to learn more about the research and ideas behind the captivating book by David Stokes.

Hi David, I really enjoyed reading your book and found myself wondering what kind of work went into creating the story.

I was on the trail of a spy story—a genre I had always enjoyed—for a few years. I did a lot of reading, both fiction and nonfiction (including history works I reference at the end of the book). Many years ago, the Cold War, particularly the presidency during that time, was the focus of my thesis when I earned my Master of Arts degree in political science. Having written a narrative nonfiction story earlier (The Shooting Salvationist), I was interested to experience the fact that it required nearly as much research to write my novel as it did that previous true story.

Before we get to Camelot’s Cousin, I wanted to know a little more about what inspired you to get into writing. Have you always wanted to be a writer or did it build up over time?

I had thought about it for many years and in my work as a minister writing has played a big part. But the decision to actually write books (and articles, essays, columns, etc.) was around my 50th birthday in 2006. I guess I created a bucket-list of sorts when passing that milestone, realizing how life was passing by and I became more goal oriented when it came to writing.

I noticed the correlation between your radio career and the character Templeton Davis being a radio host. Do you feel it’s easier to create a story when pulling from personal experience?

Yes, certainly. And though Templeton Davis is not based on me, I wanted to create a character and context familiar to me—one that I could write about with credibility.

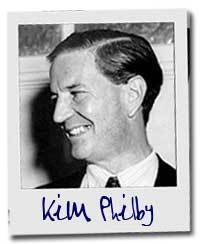

I really enjoyed the history you weaved into Camelot’s Cousin. How did you go about choosing Kim Philby to use in your topic?

Kim Philby was probably the most famous (infamous) spy during the Cold War and his story has been told many times and in many ways. In fact, the great espionage writer, Robert Littell, recently published a novel about him called, Young Philby. In the fall of 2011, I spoke at Darmouth College about my nonfiction book and had dinner after with a Pulitzer Prize winning writer (for journalism in the 1970s). He had covered the “spy beat” for many years back in the day and we had a conversation about Mr. Philby that really inspired me to build the story already developing in my mind around him.

Camelot’s Cousin had a lot of background research and information to back up parts of the storyline – what’s your method for researching the history behind your story?

Camelot’s Cousin had a lot of background research and information to back up parts of the storyline – what’s your method for researching the history behind your story?

Reading. Then more reading. It’s as simple as that. I probably have more than 200 books in my library about Cold War espionage (my personal library has more than 7,000 books). And the stories and images have long been part of my thoughts. Practically speaking, I took copious notes in journal-type notebooks. But much of the research was conducted as the story was being written, requiring long pauses at times to work things through.

Do you have an estimate for about how much time went into writing Camelot’s Cousin?

It took me about 6 months to write the narrative, then a few more months working with an editor in New York to polish it. This editor helped me with my previous book—an older gentleman who years ago discovered both Stephen King and John Grisham. I mention him in the book’s acknowledgement section. He was very helpful.

What can we look forward to from you next?

I have about 10 books in my head—fiction and nonfiction, but currently I am writing a political novel based on a true story from the late 1940s.

May 25, 2015

We Must Never Forget!

In 1916, the late poet Robert Frost penned the famous lines: “Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—I took the one less traveled by, and that has made all the difference.”

His metaphor has endured as testament to the importance of making choices based on factors other than superficiality and popularity.

President Kennedy and Robert Frost

Shortly after Frost’s death in 1963, President John F. Kennedy traveled to Amherst College in Massachusetts, where Frost had taught for many years, to deliver a eulogy about the famous wordsmith he had invited to participate in his inauguration. That day, Kennedy shared a line that, like the description of those fabled two roads, has since morphed into something beyond its original intent and focus. In my opinion, it was one of the best things Kennedy ever said:

A nation reveals itself not only by the men it produces but also by the men it honors, the men it remembers.

Next to ingratitude, forgetfulness is the most serious indicator of cultural decline. The two are intertwined. Thankfulness and remembrance are flip sides of the same precious cultural coin. On this Memorial Day, 70 years after the end of the war in Europe, we must reject the defeatism and cynicism so characteristic of our times and look back at heroes proved, and up at Almighty God in gratitude for them.

If the idea of gratitude toward God is off-putting to anyone—or seems somehow inappropriate, I would simply note how a famously liberal Democratic President approached matters on national radio seventy years ago. Roosevelt became America’s pastor for a moment and prayed:

“Almighty God: Our sons, pride of our Nation, this day have set upon a mighty endeavor, a struggle to preserve our Republic, our religion, and our civilization, and to set free a suffering humanity. Lead them straight and true; give strength to their arms, stoutness to their hearts, steadfastness in their faith…”

He added: “And, O Lord, give us Faith. Give us Faith in Thee; Faith in our sons; Faith in each other; Faith in our united crusade. Let not the keenness of our spirit ever be dulled. Let not the impacts of temporary events, of temporal matters of but fleeting moment let not these deter us in our unconquerable purpose.”

And he ended with: “Thy will be done, Almighty God. Amen.”

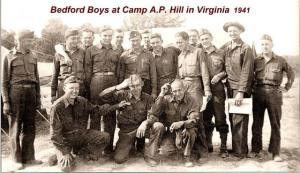

Elisha “Ray” Nance, who died a few years ago, was well known around Bedford, Virginia, a picturesque town located at the foot of the Blue Ridge Peaks of Otter, where for years he delivered the mail on nearby rural routes. But it was for what he did before becoming a letter carrier that he is best remembered.

Ray was one of “The Bedford Boys.”

He was the last of his town’s contingent in Company A of the 29th Infantry Division’s 116th Infantry – a group that waded ashore seven decades ago on a beach nicknamed Omaha in a far away place called Normandy in France. And of the thirty soldiers from Bedford (population then, about 3,200), he was one of only eight from his hometown who lived to tell the story.

He was the last of his town’s contingent in Company A of the 29th Infantry Division’s 116th Infantry – a group that waded ashore seven decades ago on a beach nicknamed Omaha in a far away place called Normandy in France. And of the thirty soldiers from Bedford (population then, about 3,200), he was one of only eight from his hometown who lived to tell the story.

Ray lost twenty-two Bedford buddies that day, nineteen of them in the very first moments of the battle. By the time he made it to the beach in the last of his company’s landing crafts, he saw “a pall of dust and smoke.” He could barely see “the church steeple we were supposed to guide on.” He couldn’t see anyone in front, or behind him—only that he “was alone in France.”

Mr. Nance was a hero “proved through liberating strife.”

On the fortieth anniversary of D-Day, President Ronald Reagan captured the attention of history and honored some of the other “Boys” who did so much for all of us on June 6, 1944. He called them “The Boys of Pointe Du Hoc,” and many of them were in his cliff-top audience in Normandy that day in 1984.

President Ronald Reagan salutes during a ceremony commemorating the 40th anniversary of D-day, the invasion of Europe.

If you wanted to pick a more unlikely place for an important military attack, you’d be hard-pressed to come up with a spot more uninviting than the imposing, rugged cliffs overlooking the English Channel four miles west of Omaha Beach. More than a decade ago, I had the privilege of visiting the Normandy region for a speaking engagement. I stood on the spot where the Great Communicator spoke and tried to wrap my mind around the quite-evident impossibility of what the United States Army Ranger Assault Group accomplished that fateful day. Mr. Reagan honored those men there:

We stand on a lonely, windswept point on the northern shore of France. The air is soft, but forty years ago at this moment, the air was dense with smoke and the cries of men, and the air was filled with the crack of rifle fire and the roar of canon. Behind me is a memorial that symbolizes the Ranger daggers that were thrust into the top of these cliffs. And before me are the men who put them there. These are the boys of Pointe Du Hoc. These are the men who took the cliffs. These are the champions who helped free a continent. These are the heroes who helped end a war.

The boys of Bedford are now all gone. And noble ranks of the boys of Pointe Du Hoc have been thinned out by the course of time as well. Other heroes have taken their place and are equally worthy of our gratitude and honor.

Kennedy was right—how we remember heroes of the past, and how we treat heroes in our day, reveals the heart and character of our nation.

Reagan was right, too: “Strengthened by their courage, heartened by their valor, and borne by their memory, let us continue to stand for the ideals for which they lived and died.” Amen.

May 21, 2015

The Great War and Faith in America

The conflict triggered by a 20-year-old fanatic with a Browning semi-automatic pistol in the faraway Balkans changed politics, economics, and social culture. But what is often overlooked is the impact the global conflict had on the spiritual condition of America.

More than a century ago, the world lurched and stumbled into the most destructive war it had ever seen. Eventually, 65 million men would be mobilized. Twenty million would die. Another 21 million would be wounded. In the conflict’s wake — and as world leaders planned, plotted, and partitioned — much of the planet became a hot zone as an influenza epidemic wiped out another 25 million people.

Historians and scholars are still trying to figure out what happened that fateful summer a century ago. Was the casus belli of what was then called The Great War (or informally, The War to End All Wars) the inevitable result of a tangled web of alliances and treaties ebbing and flowing between the nations of Europe? Or, was it because there had been a decades-long arms race, including the proliferation of a new class of warship, the Dreadnought? Were political leaders guilty of hubris? Did soldiers and sailors really believe the whole thing would be over in a matter of months?

One of the better books on the subject came out in 1962. Written by Barbara Tuchman and titled The Guns of August, it chronicles the miscalculations, underestimations, and shortsighted decisions made by European leaders in the aftermath of the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie in Sarajevo by Gavrilo Princip on June 28, 1914.

One of the better books on the subject came out in 1962. Written by Barbara Tuchman and titled The Guns of August, it chronicles the miscalculations, underestimations, and shortsighted decisions made by European leaders in the aftermath of the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie in Sarajevo by Gavrilo Princip on June 28, 1914.

President John F. Kennedy, a voracious speed-reader, devoured the book when it came out. A few months later, when faced with his own unique crisis-laden situation — Soviet missiles were being placed in Cuba — he read it again. He wanted to get a copy to the captain of every ship on the “quarantine” line he had established to intercept Russian ships bound for Havana during those tense days.

It is tempting to say that what we now call World War I was merely about military might meeting political folly. But I think the roots of the conflict lay in something more philosophical — even spiritual.

In 1983, Alexander Solzhenitsyn, the Soviet dissident, received the Templeton Prize for Progress in Religion at a ceremony in London. During his acceptance speech he may very well have explained not only the “revolution” that wrecked his homeland, but the underlying cause of the colossal conflict that wreaked havoc on the world beginning in 1914:

“More than half a century ago, while I was still a child, I recall hearing a number of older people offer the following explanation for the great disasters that had befallen Russia: Men have forgotten God; that’s why this has happened.” [Emphasis added]

For decades, continental Europe had been creeping and convulsing away from its historic religious underpinnings. Across the English Channel, Great Britain was drifting, as well, but the impact of pulpit giants during the latter part of the nineteenth century mitigated the spiritual decline, at least somewhat.

This was not the case in France or Germany. The French Revolution had left in its wake the kind of tyranny that would appear again and again over the next two centuries. The revolt that began in 1789 was in many ways the sinister ancestor to Communism and Fascism. And in Germany a new “rationalism” had gained a theological foothold in seminaries and churches.

The living God was being replaced with the worship of “reason.”

Soon, other destructive philosophical systems coalesced in this environment. Karl Marx crafted a political and economic vision for a world without God. Charles Darwin published his ideas about human origins — origins that had no need of a Creator. Then Friedrich Nietzsche and others began to cherry-pick all the new ideas characterizing the zeitgeist of 19th-century Europe and take them to their logical conclusion: God was dead.

The inevitable fruit of this long slide downward was best articulated in Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s last novel, The Brothers Karamozov, published a few months before his death in 1880. One of his characters contemplates the ramifications of God dying: “Without God and the future life? It means everything is permitted now, one can do anything?” This is often paraphrased in a quote attributed to the novelist: “If there is no God, everything is permissible.”

The rest, as they say, is history.

By 1914, the mix of Nietszche’s deification of the “will to power,” distorted forms of Darwinism, and it’s hybrid Social Darwinism (complete with its implications of selective racial superiority), and a perpetual arms race, had created spiritual dry cultural kindling just begging for a spark.

George Weigel, Distinguished Senior Fellow of the Ethics and Public Policy Center in Washington, D.C., has written: “… the erosion of religious authority in Europe over the centuries — meaning the erosion of biblically informed concepts of the human person, human communities, human origins, and human destiny — created a European moral-cultural environment in which politics was no longer bound and constrained by a higher-authority operative in the minds and consciences of leaders and populations.”

The United States managed to keep out of things “over there” for quite a while. Even the loss of 128 Americans aboard the Lusitania, torpedoed by a German U-Boat in 1915, wasn’t enough to draw us in. In fact, President Woodrow Wilson won a second term in 1916 campaigning on the slogan: “He Kept Us Out of War.”

But not for long.

Wilson, on April 2, 1917, asked Congress for a declaration of war so that the world could be made “safe for democracy.” He had a vision for a new world order. And as this nation mobilized to join the physical conflict, churches and denominations across the country were facing a very real internal war of their own. It involved the same philosophical ideas that had short-circuited the spiritual vitality of the old world. However, unlike Europe, America still had a sizable remnant of doctrinal diehards who would not bow the knee to any modern Baal.

Two theological ideas emerged in this country against the backdrop of the European war and our ultimate involvement: Fundamentalism and Premillennialism. The former was a reaction to attempts to undermine the authority of the historic Christian faith. The latter was a response to the false optimism of the social Darwinism behind various progressive movements, both secular and ecclesiastic. The war was proving every day that the world was not getting better and better. The social gospel, in concert with philosophies of human potential and the worship of reason, was proving to be powerless against human nature unredeemed and unrestrained by the salt-like impact of authentic Christianity, the kind rooted in a belief in the authority of Scripture.

Two theological ideas emerged in this country against the backdrop of the European war and our ultimate involvement: Fundamentalism and Premillennialism. The former was a reaction to attempts to undermine the authority of the historic Christian faith. The latter was a response to the false optimism of the social Darwinism behind various progressive movements, both secular and ecclesiastic. The war was proving every day that the world was not getting better and better. The social gospel, in concert with philosophies of human potential and the worship of reason, was proving to be powerless against human nature unredeemed and unrestrained by the salt-like impact of authentic Christianity, the kind rooted in a belief in the authority of Scripture.

Actually, the advancement of both Fundamentalism and Premillennialism began in 1909, a year that turned out to be pivotal for American evangelicalism. It was the year Cyrus Ingerson (“C. I.”) Scofield published his famous reference Bible. The Scofield Bible became the ultimate text for dispensational premillennial thought for the next 50 years.

Also, in 1909, Lyman Stewart, a wealthy Presbyterian oilman, attended a service at Baptist Temple in Los Angeles, where A.C. Dixon, pastor at Moody Church in Chicago, was the guest preacher. Stewart had been interested in Christian publishing and had the idea to bankroll some books to defend historic Christian doctrine. The preacher and the tycoon talked after the service and soon formed an alliance. Dixon established the Testimony Publishing Company and Lyman recruited his brother Milton to help.

They became the Koch brothers of conservative Christianity for the next few years, anonymously funding the printing and distribution of twelve books called The Fundamentals. These volumes, mailed free of charge to hundreds of thousands of people across America, were published between 1910 and 1915, and each contained articles written by the leading conservative Christian teachers of the day — B.B. Warfield, R.A. Torrey (who edited the final three volumes), G. Campbell Morgan, A.T. Pierson, W.H. Griffith-Thomas, Thomas Spurgeon, and C.T. Studd. Eventually, more than three million copies were distributed.

The Fundamentals informed and fueled a movement. By 1920, the name “Fundamentalist” was being worn as a badge of honor by Americans who cherished sound Biblical doctrine. These same people were resolved that the ideas that led to spiritual bankruptcy in Europe would never gain a stranglehold over America.

There is one particularly interesting sidelight from the days of The Great War and the convergence of Fundamentalism and Premillennialism, and this had to do with views on the subject of patriotism.

At first, many Christian conservatives of the day — people who would soon be identified as Fundamentalists — were wary of involvement in the war. William Jennings Bryan is an example. The man today remembered most for his tepid final act at the Scopes trial in Tennessee in 1925, was actually a multi-faceted character. The three-time Democratic nominee for President (1896, 1900, and 1908) helped get Wilson elected in 1912. He was rewarded for his efforts with an appointment as U.S. Secretary of State. But war talk led him to resign in the wake of the sinking of the Lusitania in 1915. He opposed America’s entry into the war, not as a pacifist, but as a “peace-advocate.”

Then there was Billy Sunday. The famous evangelist was at the peak of his popularity as American boys began to cross the ocean to fight. And he turned his meetings into patriotic affairs. He said: “Christianity and Patriotism are synonymous terms and hell and traitors are synonymous.” He called the Germans “a great pack of wolfish Huns whose fangs drip with blood and gore.” Billy’s words were seldom minced.

One of the watershed moments in the embryonic days of American Fundamentalism, coming just five days after Congress declared war on Germany and the Central Powers, Billy Sunday opened a ten-week meeting in New York City. A temporary “tabernacle” with a seating capacity of nearly 20,000 was erected at 168th Street and Broadway. It filled every time the evangelist preached. Four train-car loads of sawdust covered the floor. Total attendance reached more than 1.5 million, and there were more than 98,000 conversions.

The New York Times, which just days before Sunday’s arrival in the city had been carrying banner headlines about the country’s wartime mobilization, began to make a place on the masthead for a box score about Billy’s campaign. Directly across from the paper’s iconic motto, “All the News that’s Fit to Print,” readers saw a daily running total of converts from the upper Manhattan meetings.

Billy Sunday held a premillennial view of Biblical prophecy, though this subject had been studiously avoided in The Fundamentals. Instead, Mr. Scofield’s Bible and study notes became the primary delivery mechanism for the increasingly popular eschatological view.

Billy Sunday held a premillennial view of Biblical prophecy, though this subject had been studiously avoided in The Fundamentals. Instead, Mr. Scofield’s Bible and study notes became the primary delivery mechanism for the increasingly popular eschatological view.

The strongest opposition to those who were moving toward a premillennial viewpoint, in light of world events, was not from Biblicists who held different views on the end times (read: Postmillennialists or Amillennialists). Instead, the fire came from theological liberals, chief among them Shailer Matthews.

The dean of the Divinity School at the University of Chicago, Matthews, was an outspoken advocate for theological liberalism — particularly what was known as the social gospel. He published articles and pamphlets ridiculing the idea of a literal Second Coming of Christ. One of his colleagues even went so far as to speak out against premillennialism as a dangerous ideology that was contrary to “the very heart of American ideals.”

These liberal theologians saw premillennialism as “a sinister conspiracy.” They even tried to imply that holding the doctrine could be treasonous. Shirley Jackson Case (a male, despite the name), also on the Divinity School faculty in Chicago, told newspaper reporters from the Chicago Daily News: “Two-thousand dollars a week is being spent to spread the doctrine. Where the money comes from is unknown, but there is strong suspicion that it emanates from German sources. In my belief the fund would be a profitable field for governmental investigation.”

The argument seemed to be that describing the world as beyond repair was akin to anarchist ideas about blowing things up in order to build something better. Case, in an article titled “The Premillennial Menace,” suggested that while our soldiers were fighting in France “it would be almost traitorous negligence to ignore the detrimental character of premillennial propaganda.”

One Fundamentalist replied smartly: “While the charge that the money for premillennial propaganda ‘emanates from German sources’ is ridiculous, the charge that the destructive criticism that rules in Chicago University ‘emanates from German sources’ is undeniable.”

And popular Bible teacher Arno C. Gaebelein spoke out on the destructive influence of apostate theology on European culture. He suggested that if churches in Germany and other European countries had “entered the conflict against German rationalism fifty years ago, as loyalty to Christ demanded, this most destructive and hideous of wars could never have occurred.”

Fundamentalists and Premillennialists were joining hands as never before. And this union brought about a change. Premillennialists had long been critical of reform and progressivism, seeing not only no hope, but no point in dealing with cultural issues. But when America went to war, more and more of those who had disengaged from trying to influence culture found ways to reconcile an ultimate hope with temporary issues.

J. Frank Norris of Fort Worth was one of the earliest to combine ardent premillennialism with an activist approach to community standards and issues. Billy Sunday clearly modeled this as well. For others, the journey was more conflicted, though they eventually arrived. William Bell Riley, pastor of First Baptist Church in Minneapolis, was becoming one of the nation’s leading Fundamentalist-Premillennialists.

As the war in Europe was nearing its end in 1918, he said he had no quarrel with the cry: “Make the world safe for democracy.” He did, however, add: “But who will rise, and when will he come to make democracy safe for the world?” He then emphasized that nothing was more compelling than personal conversion and the “divinely appointed plan of divine redemption.”

Riley, Norris, and many others would ride the Fundamentalist-Premillennialist wave for the next few years and see their movement become, for a brief time, one of the most potent in the nation during the 1920s. The Baltimore journalist H. L. Mencken would eventually write, “Heave an egg from a Pullman car anywhere in the country and you’re likely to hit a Fundamentalist smack in the face.”

May 1, 2015

The Fight of the LAST Century

THE OLD YANKEE STADIUM in the Bronx, located at East 161st Street and River Avenue in the Bronx, was much more than a baseball park; it was America���s premier outdoor arena.��If we were to pick a place that has been to us what the Coliseum was to Rome in days of glory, most would nominate Yankee Stadium, whether they liked the Yankees or not.

When it comes to sports, the stadium was not just a place for home runs, it was also the field of battle for gladiators of the gridiron and other team sports.

And, of course, there was the boxing.

It���s been more than a generation since a championship fight was held at Yankee Stadium (Muhammad Ali vs. Ken Norton in September 1976), and they were becoming rare events for the venue even then.��But during the sweet science���s heyday in the 1920s-1950s, the stadium ring planted over second base was the scene of many epic battles.

It���s been more than a generation since a championship fight was held at Yankee Stadium (Muhammad Ali vs. Ken Norton in September 1976), and they were becoming rare events for the venue even then.��But during the sweet science���s heyday in the 1920s-1950s, the stadium ring planted over second base was the scene of many epic battles.

Sugar Ray Robinson, often referred to as the greatest ���pound for pound��� boxer of all time, had already won welterweight and middleweight titles.��On a dreadfully hot night in June 1952, he tried to win the light-heavyweight crown against champion Joey Maxim.��And he was clearly winning when he succumbed to heat exhaustion in the fourteenth round.��He did, though, last longer than the referee, who had been carried out two rounds earlier.

Jack Dempsey, on the comeback trail seeking a rematch with Gene Tunney, fought at Yankee Stadium in 1927.��Tunney fought there, too.��In fact, there were 30 championship fights held on that field.

Calling something the best, or most significant, is always subjective and therefore risky.��But I think I���m right when I suggest that Yankee Stadium���s greatest moment did not involve Babe Ruth or even Reggie Jackson.��It wasn���t even a baseball game.

It was the fight of the century.

The 20th century.

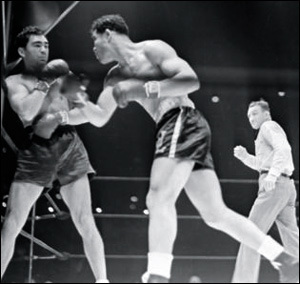

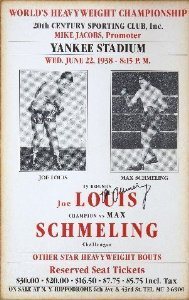

Long before even the parents of Floyd Mayweather and Manny Pacquiao were born, two boxers climbed into the famous stadium���s ring on June 22, 1938 and squared off in the most historic boxing match of all time.�� Max Schmeling and Joe Louis had fought in the same ring two years before, and the former world heavyweight champion from Germany had somehow, some way, found a flaw in Louis��� style.

The Brown Bomber from Detroit (the Yankees would soon be called ���Bronx Bombers��� as a take off on Louis��� nickname), as he was called, had been well on his way to pugilistic immortality, easily dispatching opponents���even former champions ��� hardly breaking a sweat.��He seemed to be invincible.��But the first fight with Max ended with Joe on the canvas in the twelfth round trying to remember who and where he was.

It was the 1930s and the world was becoming a very ominous and confusing place.��Hitler���s Nazi-Germany was on the move, and the dictator was beginning to look invincible himself.

Schmeling, as a German, was blocked from fighting James J. Braddock for the title, even though he was clearly the number one contender.��It fell to Louis to fight the Cinderella Man in 1937. Braddock was defending his title for the first time.��Louis went down in round one of that fight ��� only to come back strong and knock Braddock out in the eighth.

Yet, though he was the champion in name, Louis knew that he wouldn���t be able to think of himself that way until he could settle his score with Mr. Schmeling.��Most fight fans felt the same way.

In ancient times there was something called representative warfare, where one man from an army would do battle with an opponent sent by the enemy, and the larger conflict would be decided by this ���one on one��� ordeal.�� The Philistine giant, Goliath, who taunted the ancient Israelites, proposed this kind of settlement to the issues of his day.��Then he met a boy named David.

In 1938, as the world was becoming increasingly polarized in the face of impending war and as it was becoming clear to all people of freedom and good will that the Nazis were evil, the situation was ripe for a representative battle of sorts.��And the rematch of Joe Louis and Max Schmeling fit the bill.

So, on that night in 1938, veteran referee Arthur Donovan gave his ring instructions to two determined boxers as nearly 70,000 Yankee Stadium spectators looked on.��More than 100 million radio listeners tuned in from around the world.��This was the largest broadcast audience ever up to that time and included just about half of the American public.��That morning, the New York Journal-American had a large cartoon in the paper, one that showed a stadium and two figures in a boxing ring.�� Hovering above the ring was the image of an immense globe bearing the face of a man.��He was looking down on the scene on behalf of all humanity.

So, on that night in 1938, veteran referee Arthur Donovan gave his ring instructions to two determined boxers as nearly 70,000 Yankee Stadium spectators looked on.��More than 100 million radio listeners tuned in from around the world.��This was the largest broadcast audience ever up to that time and included just about half of the American public.��That morning, the New York Journal-American had a large cartoon in the paper, one that showed a stadium and two figures in a boxing ring.�� Hovering above the ring was the image of an immense globe bearing the face of a man.��He was looking down on the scene on behalf of all humanity.

Yes, it was that big of a deal that night.

Author David Margolick, in his definitive account of that evening entitled Beyond Glory: Joe Louis vs. Max Schmeling and a World on the Brink, wrote: ���The fight implicated both the future of race relations and the prestige of two powerful nations.��Each fighter was bearing on his shoulders more than any athlete ever had.��One didn���t need to be an anthropologist to know there had never been anything like it, or a soothsayer to know there would never be anything like it again.��If Louis won, no rivalry on the horizon could possibly generate as much excitement.��And with Europe and, inevitably, America, on the brink of war, the world would soon enough have more than prizefights on its mind.���

If you ever get a chance to see a film of the fight that night, try to find the audio of the radio broadcast by NBC���s Clem McCarthy as well.��His gravelly voiced blow-by-blow description turns the ear into an eye.��Joe Louis was ready this time ��� he knew what he was fighting for, and he didn���t want to waste any time.

Seven seconds into the bout, Joe Louis snapped the head of his opponent back with a left-jab, then another, and another.��Later opponents would suggest that Louis��� jab wasn���t a Muhammad Ali-type flick but more like putting a light bulb against your face, then breaking it.��Thirteen seconds later he had Schmeling on the ropes.��McCarthy could hardly keep up: ���And Louis hooks a left to Max���s head quickly! And shoots over a hard right to Max���s head!��Louis, a left to Max���s jaw!����A right to his head!��Louis with the old one-two!��First the left and then the right!��He���s landed more blows in this one round than he landed in any five rounds of the other fight!���

You get the picture.

In two minutes and four seconds it was over.��But no one felt cheated.��There were no catcalls that might usually accompany a lop-sided battle.��Referee Arthur Donovan later said: ���A referee lives a lifetime in two minutes like that.�����

So does a nation.

The rest is history.��The defeat of the German in the ring didn���t slow the world���s long slide into war ��� nor could it have.��Louis went on to fight again and again and again, defending his title successfully fifteen more times before December 7, 1941.��Schmeling went home in disgrace.��Nazis didn���t like it when someone from their master race got beaten up by a black man.

A few months after the fight, on November 9, 1938, as Nazis terrorized Jewish businesses and houses of worship during Kristallnacht, Max Schmeling sheltered two Jewish young people in his hotel suite in Berlin.

Joe Louis served his country in uniform during the war and emerged after to continue his career, though the clock was running out on his days of glory.��He died in 1981. His former foe helped pay the cost of Joe���s funeral. Max Schmeling, who lived to be just seven months shy of a hundred years old, died in 2005.

Their brief, but explosive meeting in June 1938 at Yankee Stadium captured the attention of the world and the imagination of our nation. — DRS

April 5, 2015

The Easter Effect & Real Change

There are moments in time and space when transitory issues fade in significance as things that seem to matter so much are trumped by what really matters most.

Today, as people around the globe gather to remember, honor, and reflect on events that happened some 2,000 years ago in a micro-spot on the world map, it is fitting, I think, to take a departure from the relentless, and at times tedious debate about politics and policies big and small. Let us, for a moment at least (hopefully a life-long moment), focus on a simple, yet profound scenario. One that can be described succinctly and received joyously���it is something called the Gospel.

The word itself comes from the idea of ���good news��� or ���glad tidings,��� and is intended to be a divinely directed message of hope. It is a reminder that there is hope, now and in the future. And though we get worked up into a regular lather over issues that polarize people���and I am not suggesting that these issues lack importance���as I read the Biblical record I find it endlessly fascinating that a small group of people, from ordinary backgrounds, and with few natural gifts, could make such a difference in their world and history itself.

They were the first to experience The Easter Effect. They lived, worked, and later died with a sense of fulfillment and joy because they never got over what they knew to be true, having seen it with their own eyes. They were dramatically changed people. We could use the word ���converted��� to describe it, completely transformed by an encounter with that aforementioned simple scenario involved in the Gospel. The Apostle Paul put it this way:

���Moreover, brethren, I declare to you the gospel which I preached to you, which also you received and in which you stand, by which also you are saved, if you hold fast that word which I preached to you���unless you believed in vain. For I delivered to you first of all that which I also received: that Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures, and that He was buried, and that He rose again the third day according to the Scriptures, and that He was seen by Cephas, then by the twelve. After that He was seen by over five hundred brethren at once, of whom the greater part remain to the present, but some have fallen asleep. After that He was seen by James, then by all the apostles. Then last of all He was seen by me also, as by one born out of due time.��� (I Corinthians 15:1-8 NIV)

When he wrote this, and as first century Christians migrated and ministered en route to the uttermost parts of the earth, it was against the backdrop of the rule of Rome. Social, political, and cultural dynamics were arguably a bit more challenging than what we see in America today, but those pioneers of the faith once for all delivered were largely unmoved by what would seem to be a daunting challenge. This was because they grasped the concept that the message of the Gospel was more about redemption than reformation, more about individual salvation than solving social problems, more about a world to come than the world that was���or is.

This is not to say that these souls on fire were indifferent to cultural or political matters, but they knew that ultimate hope and change were never really possible via human means and methods. And when they did pray for those in authority���even those with tyrannical tendencies in Rome���they did so with the seemingly singular goal of desiring to be left alone to live for God:

���Therefore I exhort first of all that supplications, prayers, intercessions, and giving of thanks be made for all men, for kings and all who are in authority, that we may lead a quiet and peaceable life in all godliness and reverence. For this is good and acceptable in the sight of God our Savior, who desires all men to be saved and to come to the knowledge of the truth. For there is one God and one Mediator between God and men, the Man Christ Jesus.��� ��� (I Timothy 2:1-5 NIV)

Like the prayer for the Tsar in Fiddler on the Roof���that he may stay far away���this was a plea for freedom. But it was also a plea for a particular kind of freedom, to be able to live right and model and share the hope of the Gospel.

They were a generation under the influence of The Easter Effect���people who were changed from the inside out and who eventually turned the world upside down (See: Acts 17:6).

Happy Easter���He Is Risen!

March 25, 2015

A Very True Spy Story

SEVERAL YEARS AGO, David Cornwell (better known by his nom de plume John Le Carr��) told an interviewer that ���espionage was not really something exclusive and clandestine.��It was actually the currency of the Cold War.��Spies were the poor bloody infantry of the Cold War.���

They still are, though these days we are in a different war and battling another pernicious ideology. I have read Cold War spy novels for years and even written a couple of my own. They make for entertaining reading, but the more we learn about the nuts and bolts of what actually went on back then, the better we come to understand that truth is, in many ways, even more dramatic than fiction.

Consider the case of Colonel Ryszard Kuklinski.��He was a Polish patriot who may have saved his nation, the whole continent of Europe, and maybe even the world, from massive suffering at the hands of a Soviet war machine which was once poised to race from behind Warsaw Pact borders to the Atlantic Ocean.

Consider the case of Colonel Ryszard Kuklinski.��He was a Polish patriot who may have saved his nation, the whole continent of Europe, and maybe even the world, from massive suffering at the hands of a Soviet war machine which was once poised to race from behind Warsaw Pact borders to the Atlantic Ocean.

A few years ago, I attended a symposium at Langley on the life and work of this remarkable, unsung hero who risked life, limb, and loved ones to pass along vital information at a crucial moment during the Cold War.�� Under the watchful eye of then DCIA General Michael V. Hayden, and as part of a very real social contract with this country, voluminous declassified materials were being made available to researchers and the public at large.��General Hayden was a history major back in college days and this passion clearly informed his directorate.

That particular historical symposium corresponded with the release of materials relating to Rsyzard Kuklinski and his work on our behalf, as well as that of his beloved Poland.��In fact, Kuklinski (who died in 2004) did not see himself as working for ���us��� ��� rather he consciously recruited America, via the CIA, to work on behalf of Polish freedom during a dark and difficult time.

In August 1972, Kuklinski sent a letter to the U.S. Embassy in Bonn, West Germany, establishing contact with our intelligence operatives.�� Signing it ���P.V.��� (Kuklinski later said this stood for ���Polish Viking���), this singular act began a relationship that would bear the fruit in the form of thousands of vital documents and much crucial information helping us to understand Soviet doctrine and intent.

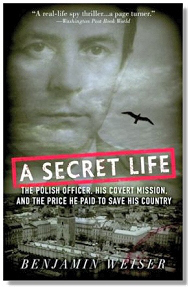

The definitive account of the Polish spy���s fascinating story was written in a book by Benjamin Weiser, a reporter for the New York Times, titled, A Secret Life: The Polish Officer, His Covert Mission, and the Price He Paid to Save His Country.

Wesier described Rsyzard Kuklinski at the time of his espionage work as ���a small man with tousled hair, penetrating blue eyes and the gestures and mannerisms of a man within whom an unbounded supply of energy is bottled up.����� He focused that energy on doing everything he could to prevent his country from being sacrificed during the Cold War as it had been in so many ways during the Second World War.

Wesier described Rsyzard Kuklinski at the time of his espionage work as ���a small man with tousled hair, penetrating blue eyes and the gestures and mannerisms of a man within whom an unbounded supply of energy is bottled up.����� He focused that energy on doing everything he could to prevent his country from being sacrificed during the Cold War as it had been in so many ways during the Second World War.

Kuklinski was motivated by patriotic fear.

His role as a high-ranking staff officer made him privy to information about what a major Soviet offensive in Europe would look like.����Though always framed via lip service as defensive in nature, the Soviet and Warsaw Pact war plans, in fact, were entirely designed to be offensive operations.

The salient point, as far as Kuklinski was concerned, had to do with the so-called Second Strategic Echelon ��� a massive potential Soviet offensive involving roughly two million soldiers and at least a million armored vehicles.�� Rsyzard, and others in a place to know about these plans, discerned accurately the only real response NATO���s forces would have to counter such a massive Soviet mobilization would be nuclear. And those bombs would not fall drop in Moscow or Western Europe; they would obliterate Poland, the perpetual twentieth century European pawn.

In fact, the materials passed to us by this highly effective Cold War spy enabled the United States and NATO to effectively plan for such a scenario. ��And the other guys never knew we had the information.��But even beyond the role he played for us strategically, Kuklinski also became our eyes and ears during those turbulent months in 1980 as the world watched Solidarity, a fledgling political movement led by Lech Walesa, begin to achieve political traction in Poland.�� The world also wondered if and when the Soviets (with the complicity of their puppets regime in Warsaw) would intervene as they had in Budapest (1956) and Prague (1968).

It seemed like only a matter of time.

Rsyzard Kuklinski was uniquely positioned in those days to report what was happening, enabling America, in the waning days of the Carter presidency, to effectively warn the Soviets off.�� At one point, he sent a sixteen-page letter to the CIA describing high-level meetings, during which the Polish government discussed the possibility off a Soviet invasion of their country.

It became clear in 1981 that the Polish government led by General Wojciech Jaruzelski, was preparing to declare martial law in the land, Kuklinski kept us informed in great detail.�� Kuklinski despised Jaruzelski, writing in one covert dispatch that the strongman was ���unworthy of the name Pole.���

In a dramatic moment on November 2, 1981, Rsyzard Kuklinski was summoned to a meeting in the office of one of his bosses.��Six men sat at a T-shaped table and learned that there was a ���mole��� among them ��� someone had been leaking information to the Americans.���� Somehow managing to keep his composure, Kuklinski joined the chorus of voices in the room denouncing such an act of ���treason.���

But he knew his days were numbered and soon found a way to communicate this message to his handlers: ���I urgently request instructions for evacuating from the country myself and my family.�� Please take into consideration that the state border is possibly already closed for me and my family.��� For several days, CIA personnel in Warsaw tried to carry out a plan to evacuate Rsyzard, his wife, and their two sons.

Eventually they were spirited away for the long drive to Berlin.

At a reception following that symposium I was attending a few years ago, I had the opportunity to speak one on one with the driver of that car during a reception.

We stood just a few feet from the iconic CIA floor seal in Langley���s lobby.�� He told me that they had managed to get through three checkpoints en route and that he still got chills when thinking about that perilous trip.

Life in America was no picnic for this Cold War hero and his family.�� They had to live under an assumed identity and avoid outside relationships, particularly with Polish-Americans, for years.�� The two Kuklinski sons met with untimely accidental deaths less than a year apart, breaking the hearts of Mom and Dad.

Questions were raised about the nature of the deaths ��� one in a boating accident (the body never found) and the other on a college campus, felled by a hit-and-run driver.��But no evidence (beyond the circumstantial) was ever discovered pointing to anything conspiratorial or sinister.

Rsyzard Kuklinski was tried in absentia in 1984 in Poland, found guilty of treason, and sentenced to death.�� After the Cold War ended, his sentence was commuted to 25 years (which hurt Kuklinski deeply).��In 1995, the chief justice of the Polish Supreme Court annulled his sentence.��All charges against him were revoked in September of 1997, enabling him to return to Poland a free man.

In April-May 1998, Rsyzard Kuklinski made an eleven-day tour of several Polish cities. He was greeted by some as a hero on a level with Pope John Paul II.�� Others, however, protested that he was���and would remain���a traitor.

Lech Walesa, for all his good work in the cause of freedom, never completely accepted Kuklinski���s account of things ��� even suggesting publicly that Rsyzard was a ���double-agent��� working for the Soviets as well as the Americans.��No such evidence exists. In fact, as new information comes out, the argument that Kuklinski was a Polish patriot and one of the good guys gets stronger.�� But Walesa���s remarks highlight the tension that occurs when ���state��� becomes synonymous with ���country.���

Frankly, Rsyzard Kuklinski���s work ��� his willingness to risk it all for what he believed was right ��� left the world a better place.�� The Soviet Union eventually fell apart and freedom broke out in his beloved Poland.�� Neither would have happened had Warsaw Pact nations acted on clearly defined plans for continental ��� even global ��� hegemony.

When Kuklinski died in February 2004, then Director of Central Intelligence George Tenet said: ���This passionate and courageous man helped keep the Cold War from becoming hot, providing the CIA with precious information upon which so many critical national security decisions rested.�� And he did so for the noblest of reasons ��� to advance the sacred causes of liberty and peace in his homeland and throughout the world.���

Long before that statement by Tenet, Rsyzard Kuklinski had reflected, ���I am pleased that our long, hard struggle has brought peace, freedom, and democracy not only to my country but to many other people as well.���

So are we.

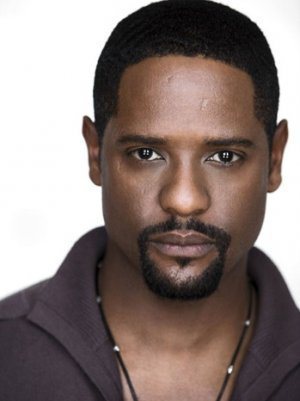

[Check out David’s spy novel, CAMELOT’S COUSIN: The Spy Who Betrayed Kennedy – now in development as a major motion picture starring BLAIR UNDERWOOD]

February 4, 2015

BLAIR UNDERWOOD to Star in Film Version of CAMELOT’S COUSIN

[From THE HOLLYWOOD REPORTER]

Blair Underwood is heading to Camelot.

The actor’s production company, Intrepid Pictures, has acquired the rights to David R. Stokes‘ spy novel Camelot’s Cousin: The Spy Who Betrayed Kennedy. Intrepid will partner with Little Studio Films to adapt the thriller into a film with Underwood in the lead role.

The actor’s production company, Intrepid Pictures, has acquired the rights to David R. Stokes‘ spy novel Camelot’s Cousin: The Spy Who Betrayed Kennedy. Intrepid will partner with Little Studio Films to adapt the thriller into a film with Underwood in the lead role.

Set amid the Cuban Missile Crisis, Camelot’s Cousin��centers on the discovery of a long-lost journal that indicates one of President John F. Kennedy‘s closest friends was a Soviet spy. In the present day, scholar and media personality Templeton Davis (Underwood) decides to investigate the journal’s contents, which draw him into a decades-old international conspiracy…

[read FULL ARTICLE at THE HOLLYWOOD REPORTER]

January 27, 2015

World Watches Britain Prepare For Churchill’s Grand Farewell

Fifty years ago this week, all eyes were on London as carefully crafted preparations for Winston Churchill’s funeral were announced and put in motion.�� He died on January 24, 1965, and the grand farewell several days later on January 30, would be watched by more than 350 million people via television, the largest audience in history at the time, surpassing even the size of the viewing audience for the funeral of John F. Kennedy fourteen months earlier.

Ceremony Making Winston Churchill Honorary U.S. Citizen. Randolph Churchill Represents his Father – 1963

Winston and Clemmie wept as they watched Kennedy’s funeral on their small television from their London town home on November 25, 1963.

Down through the years, Winston Churchill inspired hundreds of young politicians, including Jack Kennedy. In the late 1930s, when JFK���s father, Joseph P. Kennedy, was U.S. Ambassador to Great Britain (the Court of St. James), appeasement was all the rage, and Joe Kennedy was a big fan of anything that would keep his sons from going to war with Hitler. The Ambassador���s eldest son, Joe Jr., agreed with his father, but younger brother Jack saw things differently. He admired Churchill, who at that time was doing his best to awaken his sleeping nation.

That admiration continued over the years, and in 1963 Mr. Kennedy oversaw the unique process of having Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill declared an honorary citizen of the United States. The only other foreigner ever so honored was the Marquis de LaFayette, who had helped George Washington during the American Revolution.

However, by the time of the White House ceremony on April 9, 1963, Mr. Churchill���s deteriorating health prevented his travel to America. Instead, he was represented by his son Randolph at the event that included numerous luminaries, including the three sons of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Bernard Baruch, and Ambassador Joe Kennedy, who by that time was confined to a wheel chair by the devastating effects of a massive stroke.

Winston and Clementine watched the ceremony live on television at 28 Hyde Park Gate via satellite hookup, one more sign of how much the world had changed since Churchill���s Victorian childhood.

Late the next morning, there was a knock on their front door. The caller was David Bruce, the U.S. Ambassador to Great Britain. He was there on official business.

���Mr. Ambassador, so kind of you to call on me today,��� Churchill said as he greeted the diplomat.

���It is my pleasure, Mr. Churchill. I bring greetings from President and Mrs. Kennedy.���

A tear developed in Churchill���s eyes and he replied, ���Mr. Bruce, please convey my deep appreciation to the President and his lovely and charming wife. I am honored by his greeting and your visit.���

The Churchill Home – 28 Hyde Park Gate, London

Ambassador Bruce then presented Churchill with his official United States passport.

Several months later, and while still grieving the death of their own daughter, Diana (by her own hand), Winston and Clementine watched the same small television, via the same satellite hook up, as the story of the assassination of John F. Kennedy was told. Roy Howells observed the scene that sad night as the great man who had accomplished so much sat staring into the fire, clearly pondering the magnitude of Kennedy���s death.

Now Winston Churchill was dead and the long laid and frequently revised plan called Operation Hope Not was coming to life, as details of what was to transpire over the next few days were beginning to be made public.

The great man would lie in state in Westminster Hall from Wednesday through Friday. This 250-foot long hall adjoined the House of Commons, where Churchill spent his political career. When William Gladstone���s body laid in state there in 1898, more than a quarter of a million people walked by to pay respects. No one dared to try to estimate the number who would course by over the upcoming three days.

Saturday morning, the casket bearing Churchill���s body would be placed on a gun carriage for the journey to St. Paul���s Church, the site of the funeral service. Following the service, the body would be taken to a pier near the Tower of London. It would travel by barge to Festival Pier on the south side of the river, in view of the Houses of Parliament. From there the casket would be taken to Waterloo Station and loaded onto a special funeral train for the 70-mile journey to Churchill���s ancestral home���Blenheim Palace, where a burial would take place in a nearby church yard. Churchill would be joining his father and mother who were buried there decades before.

That was the basic plan. But the real drama would be in the details.

The entire initiative would involve a cast of thousands. In a sense, it would be a theater production writ large���very large. And overseeing all of it would be the Earl Marshall���a 56-year old man named Bernard Fitzalan-Howard, 16th Duke of Norfolk.

Bernard Fitzalan-Howard, 16th Duke of Norfolk

He was an old hand at big events, having overseen the coronations of George VI in 1936 and Elizabeth II in 1953. His role actually dated back to medieval times, serving as one of the seven Great Offices of State. And since ceremony was his main job���really his only job���he spent a lot of time waiting and preparing for ultimate moments, like an army general in peacetime. He loved cricket and had recently managed the English team in Australia, but he had been watching Churchill���s health over the past few years, not in a morbid way, but out of the very real desire to be ready to give the great man the send off he and the nation deserved.

The Earl Marshall had been the guardian of Operation Hope Not, the funeral plans for Churchill, from its inception. Now he was set to produce and direct an unprecedented and unparalleled event. He was also determined that his nation and its long held and practiced traditions, sometimes scorned and mocked in the modern age, would, through civility and ceremony, impress���even rebuke���those who embraced what he saw as degenerative cultural change. And since more than 100 nations would be sending delegations, including many actual heads of state, he knew that it would all be watched and analyzed by several hundred million people.

The eyes of the world would be on his masterpiece. More eyes than had simultaneously watched anything ever before.

[I am currently working on a novel set against the backdrop of Churchill���s death and funeral. It���s titled, ���THE CHURCHILL FUNERAL PLOT.��� Coming soon ��� stay tuned! ��� DRS]

January 24, 2015

Glimpses From Churchill’s Final Hours & Death

As Winston Churchill lingered for several days between life and death 50 years ago this month, the crowd near his home located at 28 Hyde Park Gate in Kensington, seldom dipped below 250 people, even in the middle of the night, and no matter what kind of weather London in January had to offer. Beyond that, newspapers around the world had the story of Winston Churchill���s life-threatening illness on page-one.

President Lyndon Johnson sent a message: ���We are all very sorry for your illness and we are praying for a rapid and complete recovery. All of us continue to look to you for wise counsel and judgment.���

President Lyndon Johnson sent a message: ���We are all very sorry for your illness and we are praying for a rapid and complete recovery. All of us continue to look to you for wise counsel and judgment.���

Meanwhile, the other Churchill news coming out of Washington, D.C. was an announcement, by the English-Speaking Union, that the proposed statue of Churchill that was to stand astride the dividing line between the British Embassy and American soil would indeed include a cigar. There had been strong opposition to this from some members of the society���but ultimately 80 per cent of them voted in favor of the familiar Winstonian appendage.

Former President Eisenhower sent word from his Gettysburg, Pennsylvania farm, ���Mrs. Eisenhower and I are deeply distressed to learn that our old friend has been stricken with another illness.��� Charles De Gaulle���s message described his own ���feeling of shock��� at Churchill���s decline. And world leaders began to instruct their aides to begin making travel and logistical plans in the event of a funeral to come.

While the headlines each day tried to communicate the same news in different ways������Sir Winston Losing Ground,��� ���Condition of Sir Winston Worsens,��� ���Churchill Clinging to Life,��� it seemed as if the world stopped, or at least slowed down spinning on its axis.

Likely Churchill never knew that he had stopped a strike from his sickbed, but such was the case. School teachers in Great Britain had been prepared to walk off the job that day over a pay dispute, but cited the great man���s illness as the key to their decision to stage the protest ���at a more suitable time.��� Certainly, this move by labor would have amused the long time Tory leader.

The expressions coming out of the Soviet Union were predictably colder. Radio reports in Moscow tended to be terse and limited. For its part, the official newspaper for Soviet defense, Krasnaya Zvezda, included language calling Churchill, ���the godfather of the Cold War,��� and indicating that the Briton had not been forgiven for his 1946 speech in Fulton, Missouri, and the reference to an ���Iron Curtain.���

By Thursday, January 21st, Dr. Moran was reporting that his famous patient was at a low point. Archbishop of Canterbury, Michael Ramsey, told many that the great man was approaching death. By this time, however, the crowds were gone, due not to diminishing concern, but because Lady Churchill had requested it. Fresh fallen snow marked the area recently clogged by people on the narrow dead end street.

Even the press had been moved back a block or so, something Mrs. Churchill deeply appreciated. Anthony Montague Brown, one of Churchill���s secretaries and who had been the bearer of Lady Churchill���s request that everyone move away from the area around the house, walked over to where the reporters were now gathered and read an appreciative message: ���I would like to thank you for the speed with which you complied with Lady Churchill���s request. She was very touched, She has been feeling the strain.��� The journalists nodded affirmatively, almost bowing in respect.

The Friday news was more of the same, though there was a stir of sorts when the home directly behind 28 Hyde Park Gate caught fire. However, even the three fire engines responding to the blaze did their part to respect the need for quiet���they arrived at the scene without sounding sirens or bells.

Later that Friday, Lady Churchill was summoned to the telephone for a call from her grandson, Winston. Her face broke into a broad smile���the first for her in a long time���as she learned of the birth of their third great-grandchild, a boy born at Westminster Hospital. The child was premature but doing quite well, the proud father reported, adding that his wife, Minnie, was fine, as well. Clementine shared the joyous news with everyone and then went into her husband���s room and whispered it in his ear. But the great man, though breathing, was likely never aware of the blessed event. And soon Clementine���s smile was again absent from her face.

The next day was Saturday and someone noted that the next day would be the anniversary of the death of Winston���s father. The comment that he had made a dozen years earlier���about how he would die on the same date���was also recalled and rehearsed. Could it be, they wondered, that the great man was mustering all the courage and fortitude he had left to make it until the page of the calendar and hands of the clock moved to the point of his personal prophecy?

Long after the household went to bed that night, Clementine visited Winston���s room around 1:00 AM. She held his hand and sat silent next to him for a bit before heading back to bed. By the time she returned to his room about six hours later, it was clear than there had been a change for the worse. The family was summoned. Less than 30 minutes later, Randolph arrived with his son, Winston, joining Mary, Sarah, and Clementine in the drawing room. A few minutes later Lord���s Moran and Brain came in.

One of the nurses put out a tray of coffee. Everyone stood by in somber silence.

A little before 8:00 AM, Roy Howell appeared and cleared his voice while repeating, ���I think you had all better come in.��� They formed a line and one by one went to his bed, some knelt immediately, some whispered to him. Eventually all those in the room knelt prayerfully.

And just as a clock down the hallway finished pealing eight times marking the morning hour on Sunday, January 24, 1965, the Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill drew his last breath and, as the ancient scriptures often said, was ���gathered unto his fathers.���

[I am currently working on a novel set against the backdrop of Churchill’s death and funeral. It’s titled, “THE CHURCHILL FUNERAL PLOT.” Coming soon — stay tuned! – DRS]