Andy Worthington's Blog, page 73

June 16, 2016

Remembering Guantánamo’s Dead

Every year, I publish an article remembering the men who died at Guantánamo in what, in 2013, I first described as “the season of death” at the prison — the end of May and the start of June, when six men died: three on June 9, 2006, one on May 30, 2007, another on June 1, 2009, and the last on May 22, 2011.

Every year, I publish an article remembering the men who died at Guantánamo in what, in 2013, I first described as “the season of death” at the prison — the end of May and the start of June, when six men died: three on June 9, 2006, one on May 30, 2007, another on June 1, 2009, and the last on May 22, 2011.

Of the six, only the last death — of Hajji Nassim, an Afghan known in Guantánamo as Inayatullah — appears very clearly to have been a suicide. Nassim had profound mental health issues (as well as being a case of mistaken identity), but although there was no reason to suspect foul play, it is, as I explained last year, “disturbing and disgraceful that a profoundly troubled man, who was not who the authorities pretended he was, died instead of being released.”

Doubts have also been raised about the deaths in 2007 and 2009, as I also explained last year, when I wrote:

My very first articles, in May/June 2007, were written in response to the alleged death by suicide, on May 30, 2007, of a Saudi prisoner, Abdul Rahman al-Amri. Former prisoner Omar Deghayes later told me that al-Amri had been profoundly upset by the sexual harassment at Guantánamo — enough, perhaps, to lead him to take his own life — but Jeff Kaye (psychologist and journalist) later looked into the investigation into his death and found another murky story, as he did for Muhammad Salih (aka Mohammed al-Hanashi), another long-term hunger striker and agitator who died on June 1, 2009.

Muhammad Salih had been a cell block leader, who stood up against the injustice to which the prisoners were subjected (see former prisoner Binyam Mohamed’s article about him here), and as such his case contained eerie parallels to the cases of the three men who died on June 9, 2006, who had also been long-term hunger strikers and were well-known to their fellow prisoners.

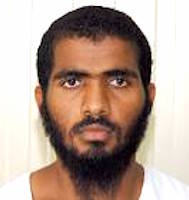

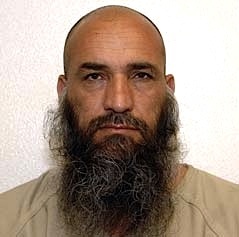

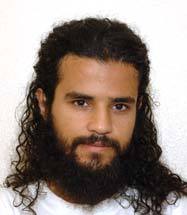

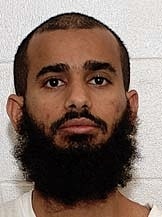

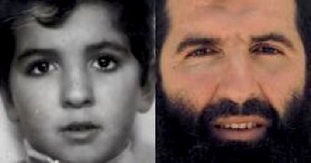

According to the US authorities, the three men — Yasser al-Zahrani, a Saudi who was just 17 years old when he was seized in Afghanistan at the end of 2001, Ali al-Salami, a Yemeni, and Mani al-Utaybi, another Saudi — committed suicide, but that always seemed implausible, as the prisoners were meant to be constantly monitored, and were not supposed to have access to sheets with which to hang themselves, even without factoring in the fact that all three were thorns in the side of the authorities.

However, although I covered the story with skepticism over the years — including when the NCIS produced a half-hearted report justifying the official line — the story only really blew wide open in January 2010, when Harper’s Magazine published “The Guantánamo Suicides” by the journalist and law professor Scott Horton, in which, drawing on testimony by a number of former military personnel — in particular, Staff Sgt. Joseph Hickman, who was in charge of the guard towers and was on duty on the night the men died — a chilling new narrative emerged: that, on the night the men died, vehicles had driven in and out of Camp Delta, to a shadowy facility known to the soldiers as “Camp No,” and later revealed to have been a secret facility called “Penny Lane,” where, it would appear, they had been tortured and killed, and where, it was also to be presumed, the rags had been stuffed down their throats that contributed to their deaths. Mention of the rags was removed from the official reporting, and, of course, it is implausible that men hanging themselves in their cells could, as well as tying themselves up, also stuff rags down their own throats.

Although widely praised, Hickman and Horton’s story hit a brick wall in the Obama administration, and has never been adequately investigated. In January 2015, Hickman’s book about the deaths, Murder in Camp Delta, was published by Simon & Schuster, but that too failed to dent the wall of official silence shielding the deaths from further scrutiny.

18 months on from the Senate Intelligence Committee’s witheringly critical report on the CIA’s post-9/11 torture program, and with a whole new trove of CIA documents just released through FOIA legislation revealing new and shocking details about torture, murder and cover-ups in the “war on terror,” it is surely time that the events of June 9, 2006 are officially revisited.

Below, I’m cross-posting a short op-ed Joseph Hickman wrote for Shadowproof (formerly FireDogLake), the excellent investigative site run by Kevin Gosztola, in which, on the 10th anniversary of the three deaths, Hickman wrote about how the deaths and their cover-up constituted a war crime, and called once more for transparency and justice.

I can only echo his words, and, to explain a little more of the story from Hickman’s perspective, I’m also posting excerpts from the interview Hickman did last February with Brooklyn-based blogger The Talking Dog, who has been conducting interviews with people intimately connected to the Guantánamo story for many years.

An excerpt from Joseph Hickman’s interview with The Talking Dog, February 2015

The first thing that matters [about the circumstances surrounding the three deaths on June 9, 2006] is that the NCIS immediately asserted that I was “only” a perimeter guard and not in a position to see what happened. That was, of course, a half truth. Half of my duties were inside Camp Delta. I was in a position to see what happened from inside the camp, and this “perimeter guard” characterization irritates me.

I was on duty. I was a reconnaissance soldier, which means you are trained in observation and what you see is important. That night I visited a number of positions. I was in charge of the solders at all of the towers inside Camp Delta. Tower 1 was only thirty-five feet from the medical clinic … it is also less than 50 yards from the walkway in Camp 1, with a clear view of it. I was also next to the entrance to Camp Delta. In the tower, I saw the white paddy wagon (which, of course, could pass without inspection or having to sign in) … I saw it back up to Camp 1, and I saw two guards get out and put a detainee in the vehicle. And then I saw the van make a right, and then a left — leaving Camp America. And then I saw the van return around twenty minutes later, and repeat the process with a second detainee.

Now this was a Friday night — there were no commissions scheduled, and there wasn’t a different camp outside the perimeter to take them to … but where were they going?

And then the van returned a third time. This time, I went to ACP [access control point] Roosevelt, the exit from Camp America, and watched. If the van went right, it would be going to the main part of the Guantánamo base — where the McDonalds, the PX and other facilities were. But if it went left, that led only to the beach (for personnel’s recreation) or to Camp No — the road led nowhere else. And the van went left. I knew it wasn’t taking detainees to the beach. This made me curious, as my only conclusion was that the van was going to Camp No. And so, I continued to do my duties of making rounds of my men’s positions.

At 11:30 pm that night, the van returned to Camp Delta. I was back in Tower 1. The van backed up to the medical clinic. I was back in Tower 1, with a clear view of the medical clinic. The van backed up to the medical clinic — my view was obstructed by the van’s doors — but I watched the guards take stretchers into the clinic. Twenty to thirty minutes later, the lights in the camp all went on, and all hell seemed to be breaking loose.

I got down from the tower, and found a Navy corpsman (or medic) who I knew, and she told me that three detainees had stuffed rags down their throats and killed themselves. I knew something horrible was happening.

I asked the guards under my command for their observations. Three guards were stationed 20 feet from the medical clinic, and they reported that no detainees had come from Camp 1 — the only movement of detainees had been the paddy wagon. In fact, none of the guards in my command, who were watching the camp all night, saw anyone transported from any camp — other than the paddy wagon.

The next morning, of course, Col. Bumgarner gave us his talk about what “actually happened” — the detainees choked to death on rags — and what we would see in the news: that they simultaneously hanged themselves and were found that way in their cells … and we were ordered not to talk about it. Nonetheless, I was sure we would be asked about what we observed, by someone. Again, I asked the tower guards in Camp 1 — was anyone transported? The answer was consistent — no. And so, if they didn’t see it, it didn’t happen. And they did not see detainees taken from Camp 1 (where they supposedly hanged themselves in their cells) to the medical clinic. It did not happen.

And the NCIS did not contact me, or my men — ever.

At the time, I tried to put this behind me. But some details stick with you: it is just so hard to kill yourself at Guantánamo. I am aware of the suicide attempt during an attorney visit you described [of Juma al-Dossari] … that was a gap in security that was solved — and even the detainee in that situation still failed in his attempt. It’s just so hard to do it.

But the biggest thing is what just couldn’t add up: three men simultaneously (in non-contiguous cells) tying their hands together, putting masks on, forming nooses, shoving rags down their throat, and then managing to hang themselves simultaneously while being watched by soldiers every three minutes.

I should also note than I came forward to speak to the Justice Department — it was not just me. Seven guards came forward to tell them what we observed.

And finally, I can tell you that the way I ended the book — noting that I can’t name names, but nonetheless, from all I know, I consider what happened on June 9, 2006 “murder” (notwithstanding that a clever lawyer might characterize it as something else) — I put out the evidence I found. This is what I believe, but the reader can decide. I still think it was murder.

Ten Years Ago, I Saw the Real Guantánamo and it Changed My Life

By Joseph Hickman, Shadowproof, June 9, 2016

Ten years ago today, I was on duty as the sergeant of the guard at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba (GTMO). While I was standing in a watchtower inside Camp Delta overlooking the detainees, I saw something that would radically change my life.

I witnessed three detainees leave the camp in a white van and be transported to a top secret CIA facility, only to return to the camp a few hours later, dead. Over the next few hours, after the bodies returned to Camp Delta, I watched a cover-up being orchestrated by the GTMO Command. My commander flat-out lied to the media about what happened, claiming the detainees committed suicide in their cells as a form of asymmetrical warfare.

That day ten years ago shook the foundation of all I thought to be true. Prior to that night, I was a “true believer” — I was a proud soldier in the U.S. Military, I was one of the good guys in the Global War on Terror. After that night, I began to question those beliefs.

When I first arrived at GTMO a few months prior to that evening, I had my doubts about whether GTMO was a humane place. I was appalled at the conditions of the camp and the treatment of the detainees. But somehow I always found a way to rationalize what I saw. The treatment of the detainees was harsh and their living conditions inhumane. They looked more like poor farmers than the “worst of the worst” terrorists in the world; but my country told me they were and I believed them.

On June 9, 2006, all of that changed. Three men died on my watch. I knew the three detainees did not die in their cells. I knew they were murdered outside of the camp at a top secret CIA facility that the U.S. government denied existed. This was inexcusable. It was a war crime.

Even though going against the U.S. military’s official story of what happened that day would most assuredly end my military career, it was my duty as a soldier to report it. I went to the U.S. Army Inspector General and the Justice Department and reported what I witnessed. After I reported it to the Justice Department, they opened an official investigation and the FBI spent almost a year looking into my allegations.

They finally contacted my attorney and told him that while “the gist of what I reported was true,” they were closing the case, and were not going to pursue any charges against those involved.

Shortly after the Justice Department decision, I left the military. Not a day goes by that I don’t think about that night. I have spent years investigating the deaths and other issues concerning GTMO. I wrote a book laying out all the facts about what happened that night, hoping that one day another investigation will be opened and truth and justice will prevail. Though my hope for that is fading, I will never give up.

Since that night, a lot has changed at GTMO. Most of the detainees have been released and sent home or sent to different countries to try to start a new life. Unfortunately, there are still dozens of people being detained in GTMO with no evidence against them, living the nightmare of being held without charge or due process.

GTMO needs to be closed. Yet it remains open, and the GTMO command claims it is transparent and has nothing to hide. They even set up VIP tours for reporters, politicians, and attorneys. The tours are rehearsed for weeks prior to the VIPs’ arrival on the Island. They show the VIPs only what they want them to see, making it appear as if they are hiding nothing.

In reality, GTMO is shrouded in secrecy. No reporter, politician, or attorney, has ever seen the real GTMO. The only people that have seen it are the detainees, the guards, and the GTMO command. If they ever did see the real GTMO, maybe then justice would be served.

Note: In remembering Guantánamo’s dead, I also want to make sure that I acknowledge the three other men who died — Abdul Razaq Hekmati, who died of cancer in December 2007, and who was a profound case of mistaken identity, as I explained in a front-page New York Times story with Carlotta Gall in February 2008, Awal Gul, an Afghan who died after taking exercise in February 2011, and Adnan Farhan Abdul Latif, a Yemeni with mental health problems, repeatedly cleared for release, who died in September 2012 (and whose death is also a disputed suicide).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ is available for download or on CD via Bandcamp — also see here). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ is available for download or on CD via Bandcamp — also see here). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

June 14, 2016

Two More Prisoners – A Moroccan and an Afghan – Seek Release from Guantánamo Via Periodic Review Boards, as Two More Men Have Their Detention Upheld

Last week, the Obama administration’s efforts to reduce the number of men held at Guantánamo, via Periodic Review Boards, continued with two more reviews. The PRBs were established in 2013 to review the cases of 41 men regarded as “too dangerous to release,” and 23 others recommended for prosecution, and were moving with glacial slowness until this year, when, realizing that time was running out, President Obama and his officials took steps to speed up the process.

Last week, the Obama administration’s efforts to reduce the number of men held at Guantánamo, via Periodic Review Boards, continued with two more reviews. The PRBs were established in 2013 to review the cases of 41 men regarded as “too dangerous to release,” and 23 others recommended for prosecution, and were moving with glacial slowness until this year, when, realizing that time was running out, President Obama and his officials took steps to speed up the process.

35 cases have, to date, been decided by the PRBs, and in 24 of those cases, the board members have recommended the men for release, while upholding the detention of 11 others. This is a success rate for the prisoners of 69%, rather undermining the claims, made in 2010 by President Obama’s high-level, inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force, that the men described as “too dangerous to release” deserved that designation, even though the task force had conceded that insufficient evidence existed to put the men on trial.

In fact that description — “too dangerous to release” — has severely unravelled under the scrutiny of the PRBs, as 22 of those recommended for release had been placed in that category by the task force. The task force was rather more successful with its decisions regarding the alleged threat posed by those it thought should be prosecuted, as five of the eleven recommended of ongoing imprisonment had initially been recommended for prosecution by the task force.

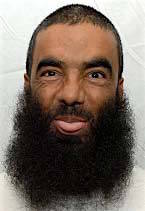

Two of those decisions took place last week, in the cases of Sanad Ali Yislam al- Kazimi (ISN 1453), a Yemeni citizen, and a former CIA “black site” prisoner, and Mohammed Abdul Malik Bajabu (ISN 10025), the prison’s sole Kenyan, and one of the last men to arrive at the prison in 2007.

Sanad al-Kazimi’s imprisonment is upheld

Both men had their cases reviewed last month, and I wrote about al-Kazimi’s review here, noting that, although the government described him as a member of al-Qaeda, albeit one who was “a somewhat disruptive and insubordinate figure” within the ranks of the organization.

Both men had their cases reviewed last month, and I wrote about al-Kazimi’s review here, noting that, although the government described him as a member of al-Qaeda, albeit one who was “a somewhat disruptive and insubordinate figure” within the ranks of the organization.

In their final determination, dated June 9, the board members determined, by consensus, as is required, “that continued law of war detention of [al-Kazimi] remains necessary to protect against a continuing significant threat to the security of the United States.”

In making this determination, the board members “considered [his] close and prolonged relationships with senior al-Qa’ida members, including after 9/11,” and also noted his “military training, his probable familial ties to al-Qa’ida in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), his history of violence and non-compliance toward the guards and interrogators, and his vague plans for post-detention life.”

However, the board members also acknowledged positive aspects of al-Kazimi’s behavior and attitudes, noting that they “greatly appreciated [his] candor” and saw “his devotion to his family as a positive.” They also recognized his “increased cooperation with detention staff” and also “appreciate[d] his personal development,” and, for his next review, an administrative file review in roughly six months’ time, they “look[ed] forward to seeing: continued compliance; increased engagement with mental healthcare staff to further improve his skills for dealing with conflict, stress, and change; continued participation in coursework at GTMO; and greater detail on his post-detention plan if family reunification is not possible in the near future.”

The suggestion, then, is that al-Kazimi might be able to demonstrate a coherent plan for life after Guantánamo, although I am not sure that his Al-Qaeda membership will be so easily forgotten, and if that is the case then I would urge the administration to find some way to charge him rather than relying on endless detention without charge or trial.

Mohammed Abdul Malik Bajabu’s imprisonment is upheld

I wrote about Mohammed Abdul Malik Bajabu’s PRB here, noting that the US authorities believe him to have been a member of Al-Qaeda in East Africa, who reportedly played a role in terrorist attacks in Kenya in November 2002 that killed 13 people and wounded 80 others, although they also acknowledged that, at Guantánamo, he has been “a highly compliant detainee,” who “has not expressed continued support for extremist activity or anti-US sentiments, although he is critical of US foreign policy.”

I wrote about Mohammed Abdul Malik Bajabu’s PRB here, noting that the US authorities believe him to have been a member of Al-Qaeda in East Africa, who reportedly played a role in terrorist attacks in Kenya in November 2002 that killed 13 people and wounded 80 others, although they also acknowledged that, at Guantánamo, he has been “a highly compliant detainee,” who “has not expressed continued support for extremist activity or anti-US sentiments, although he is critical of US foreign policy.”

In their final determination, also on June 9, and again determining that “continued law of war detention … remains necessary to protect against a continuing significant threat to the security of the United States,” the board members “considered [his] past involvement in terrorist activities including a close relationship with high-level operational planners and members of al-Qa’ida in East Africa, and his participation in the preparation and execution of the November 2002 attacks in Mombasa, Kenya,” and “also noted [his] total lack of candor regarding his pre-detention activities, the lack of a plan for his future should he be transferred, and no information provided regarding the available family support should he be transferred.”

On the latter points, it is clear, Abdul Malik made much less of a positive impression on the board than Sanad al-Kazimi, and will have to significantly change his attitude of he is to attempt to impress them.

Abdul Latif Nasir’s Periodic Review Board

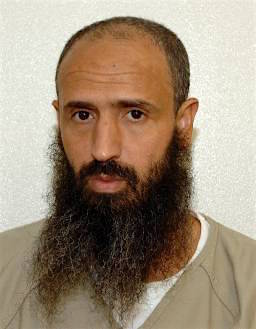

While these decisions were being taken, the first of last week’s reviews took place, on June 7, for Abdul Latif Nasir (ISN 244), the last Moroccan in Guantánamo, who is 51 years old, and was designated as “too dangerous to release” by President Obama’s task force in 2010.

Back in April 2008, I described how Nasir “had worked as a small-scale businessman in Libya and Sudan, and had also spent time in Yemen and Pakistan. He was captured in Afghanistan in late 2001, and has explained that he was attracted to the country because of its Islamic scholars and its piety. In Guantánamo, he has experienced particularly harsh treatment, because he stands up for the rights of his fellow prisoners, and refuses to keep silent in the face of injustice.”

In September 2010, I also explained how Nasir had “stated that he was not a member of al-Qaeda, and that he ‘disagreed with what bin Laden and al-Qaeda were doing outside of Afghanistan.’” I also noted that he had stated that “he did not think Osama bin Laden was in a position to issue a fatwa because he is not an Islamic scholar,” and condemned the 9/11 attacks because it was “against Islamic principles to attack innocent people.”

However, I didn’t know much more about him, except that he had taken part in the prison-wide hunger strike in 2013, and as a result, I was intrigued to see what the US authorities currently thought about him, and on looking at the unclassified summary provided by the authorities it seems to me that the combination of Nasir’s low-level status as a combatant, his good behavior in Guantánamo and his lack of connections with any terrorists means that he could well be recommended for release.

In the unclassified summary, the authorities described how Nasir “had been a conservative Muslim member of the non-violent but illegal Moroccan Sufi Islam group, Jamaat al-Adl Wa al-Ihassan, in the 1980s,” and “was recruited to fight in Chechnya by a member of the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group in 1996 while working at one of Usama bin Ladin’s charcoal production companies in Sudan.”

He then apparently “traveled to Yemen on his way to Chechnya, but was rerouted to Afghanistan in 1997 to receive training in weapons, topography, and explosives at al-Qa’ida camps.” He allegedly “became a weapons trainer at al-Farouq training camp and a member of the al-Qa’ida training subcommittee,” and “had occasional access to senior al-Qa’ida members, including Usama bin Ladin,”although on this latter point it seems clear that he had no leadership or decision-making role.

It was also claimed that he “fought for several years with the Taliban on the front lines in Kabul and Bagram, Afghanistan, and again at Tora Bora, as a commander and weapons trainer,” after he had “led a retreat” from Jalalabad to Tora Bora.

In Guantánamo, the summary noted, he “has committed a low number of disciplinary infractions compared to other detainees and most of his infractions have been failures to comply with Guantánamo guard force orders.”

It was also noted that he had been “cooperative with interrogators early on in his detention, but later retracted many of his earlier statements about his extremist activities and has refused to meet with interrogators or discuss his past since September 2007, with the exception of one session in September 2011.” Because of this lack of cooperation with interrogators, the authorities noted that they “lack insight into his current mindset and whether he would pursue extremist activity after detention,” although it was pointed out that he “has not expressed extremist views against US citizens, but almost certainly resents the United States government and those he sees as responsible for his prolonged detainment.” It was also claimed that he “has defended fighting jihad in certain circumstances and supports sharia law, which could make transfer to and integration into non-Muslim countries difficult,” although, if freed, there is no obstacle to his return to Morocco, where, crucially, he has supportive family members.

As the summary concluded, importantly, he “has had no contact with former Guantánamo detainees or individuals involved in terrorism-related activities while at Guantánamo.” He also “maintains close contact with his family in Morocco,” and “would almost certainly prefer transfer to Morocco to be with his family, who are willing and able to financially assist him with his reintegration into society.”

Below I’m posting the opening statements of one of his personal representatives (military personnel appointed to help the prisoners prepare for their PRBs) and of one of his lawyers, Shelby Sullivan-Bennis of Reprieve. The personal representative noted that he “is considered to be a thoughtful, intelligent and kind man by his fellow detainees,” and that he has availed himself of all the educational opportunities offered to him, and these observations were repeated and amplified by his attorney, who stated, “That Nasir is an introspective, intelligent, and kind-hearted man who, after all this time, seeks only to return to a family that is ready to receive him back has been consistently demonstrated over the years.” She also discussed his learning, his closeness to his family, and the job opportunities awaiting him should he be released; specifically, “full-time work at his older brother’s very successful water treatment company,” and also discussed in detail Reprieve’s expertise in helping former prisoners resettle and rebuild their lives.

Periodic Review Board Initial Full Hearing, 07 Jun 2016

Abdul Latif Nasir, ISN 244

Personal Representative Opening Statement

Members of the Board, I am the Personal Representative for Abdul Latif Nasir, ISN 244. I will be assisting Nasir with his Private Counsel this morning.

I can sincerely state that Nasir is considered to be a thoughtful, intelligent and kind man by his fellow detainees. He is very grateful to have this opportunity to have his case heard today.

Nasir is eager to begin this process in hopes to begin his life and move forward. As such, his time in Guantánamo Bay (GTMO) has been spent wisely. For example, he has attended many classes offered such as English, Math and Computer Science. But his appetite for continuing to learn does not stop there. He continues to learn on his own through self-education. He has created a 2,000 word English/Arabic dictionary (hand written) that he uses daily to practice his English language skills. While somewhat shy, he still manages to speak to those in English in an effort to better his skills, whenever possible. In my meetings with him, we rarely used a linguist to communicate. He both understands and writes in English very well. He also reads books and watches movies in English frequently.

Nasir is an educated man, with a high school equivalent education and one additional year at the collegiate level. Nasir concentrated his studies in Math and Science. For a short time he also studied at a technical institute. Computer Science is the area of most interest to Nasir and he hopes to work in that field in the future. However, he knows that computer science is constantly evolving and it will take some time to learn everything required to find employment. In the meantime, Nasir is willing and prepared to work for his brother’s business in order to start his future in the right direction. He is patient and understands that his time lost has created a hurdle that he can only overcome with hard work and determination.

Nasir has been a compliant detainee while at GTMO, taking advantage of communal living. Therefore, he has allowed himself to be more exposed to various cultures and religious backgrounds. Nasir feels that this cultural exposure has aided in understanding various points of view allowing him to better appreciate others’ customs and beliefs. Of course, this will only serve to help with his transition into the next phase of his life.

Nasir deeply regrets his actions of the past. I am very confident that Nasir has a strong desire to put this unfortunate period o f his life behind him and move on. Nasir will seek to reintegrate into society, marry and have a family of his own. Nasir has not made any negative comments or expressed any ill will towards the United States nor displayed any evidence of an interest in extremist activities.

I appreciate your time in this matter and your consideration for a transfer recommendation.

May 23, 2016

Statement by Shelby Sullivan-Bennis, Private Counsel for Abdul Latif Nasir (ISN 244)

Periodic Review Board Hearing Scheduled June 7, 2016

Esteemed Periodic Review Board Members,

My name is Shelby Sullivan-Bennis. It is my privilege to represent Abdul Latif Nasir and to appear before this board. I do so in conjunction with my fellow private counsel, Thomas Anthony Durkin, partner of Durkin and Roberts.

Over the course of many years, our lawyers at Reprieve have gotten to know Mr. Nasir quite well. And based on that long experience we can say a few things about him without reservation.

That Nasir is an introspective, intelligent, and kind-hearted man who, after all this time, seeks only to return to a family that is ready to receive him back has been consistently demonstrated over the years. It is not a picture manufactured for the benefit of this Periodic Review Board as today’s hearing date has approached. Nor has his behavior changed radically since the widespread improvement in camp conditions that took place in early 2009. Instead — as the materials before this Board demonstrate — these personal traits and the strong support of his family have been on consistent display over the many years he has spent here in Guantánamo.

Mr. Nasir has come a long way since he was sold for a bounty into American captivity back in 2002, having never experienced U.S. or Western culture. One small iteration of how far he has come are the pleasant meetings in English that I, as a female attorney, have enjoyed with Mr. Nasir. He once knew no English; and his culture would not have permitted him to meet with a female lawyer. Over the years, he has learned the English language, and also learned to work with and respect me.

His disciplinary status at Guantánamo has been compliant. He is allowed all privileges and has presented eagerly, helpfully, and gratefully to all meetings with his Private Counsel and Personal Representative.

Mr. Nasir loves and excels at the myriad courses of which he has taken advantage in his time at Guantánamo. With a background in math and science, he naturally excels in computer science and life skills courses, but has also developed a very good understanding of English. He meets with me entirely without the assistance of an interpreter, and we are able to communicate complex details quite well; in the event of confusion, he has always been patient with me.

Mr. Nasir has — famously, across the whole prison base — drafted his very own 2,000-word English to Arabic dictionary by hand, a sample of which is included in our submission. Since arrival at Guantánamo, Mr. Nasir has made a continuing effort to use this opportunity to further learn and integrate and he has inarguably succeeded at both.

If released from Guantánamo, Mr. Nasir intends to begin full-time work at his older brother’s very successful water treatment company in Morocco, surrounded by a supportive and stable family. Mr. Nasir’s brother owns and runs a company that installs water treatment systems for swimming pools and other external and internal pools and water features. The company has both commercial and private clients, and the majority of their business comes from installing pools in Moroccan hotels. His brother has stated in his submissions before the board, and multiple times over the years, that he is prepared and eager to train Mr. Nasir to be a water treatment engineer and give him a job working with him at his company.

He will live with his family in their five-bedroom home in Casablanca, and will have ready access to several local service providers, including medical and psychological health facilities based in Casablanca with whom my office has direct contracts for provision of services to our clients. [A footnote stated, “As our ‘Life After Guantánamo’ project statement submitted to this board details, we have built particularly good relations with the ‘Association Medicale de Rehabilitation des Victimes de la Torture (AMRVT),’ a medical treatment center for victims of torture. The AMRVT’s staff is preeminent in the region as an assessment and service provide for people who have lived through trauma, and the center is conveniently based in the Nasir family hometown of Casablanca”].

Indeed, Mr. Nasir’s entire family has resided legally in Morocco for decades and is well established. His family support network in Morocco is strong; his two brothers, five sisters, three nieces, and four nephews all stand willing and able to support Mr. Nasir’s reintegration into Morocco, physically, economically, and emotionally. He has been in regular contact with them through the video calls facilitated by the Red Cross. As the letters, videos and photographs we have submitted to the Board attests, the members of his extended family and community have been ready and eager to have him back throughout the length of his detention, and they remain so today.

The family has provided ample evidence to the Board, in written and video-recorded form directly attesting to their readiness to welcome and support Mr. Nasir. The videos feature ten members of Mr. Nasir’s family currently living in Morocco, all offering their considerable resources in support of his return; he will not be welcomed by one or two people, but a household of stable, working family to help reintegrate him into society and give him purpose.

From Reprieve’s experience with over three dozen repatriated and resettled Guantánamo prisoners, we have concluded that the most important factor which determines former detainees’ success in life is family support. Team members have met the newborn babies of many of the men we have worked with and watched as they have re-focused their lives on parental responsibilities and bringing up their children as best they can. The extent and nature of the support that Mr. Nasir’s family is prepared to provide set the ideal conditions for his release.

We have a program set up to help our clients reintegrate into society called “Life After Guantánamo,” which is funded by the United Nations. This is a program that serves the interests of each relevant stakeholder — the client needs the help, and we (the United States) want the client to do well. For several clients who were resettled and repatriated by both Administrations, we worked with the State Department and host governments on transition plans for clients; we have served as an ongoing point of contact for local authorities; we have facilitated financial support and referrals for needs ranging from job placement to mental health care. We were a trusted and experienced resource in facilitating a successful transition for these clients, who are now rebuilding their lives; a number of former Reprieve clients have even successfully pursued higher education at universities after leaving Guantánamo. Finally, as mentioned, we have specific experience working with groups on the ground in Morocco. We would of course offer the same assistance for Mr. Nasir.

Thank you for taking into consideration the information we have provided. We respectfully submit that Mr. Nasir should be approved for transfer from Guantánamo consistent with the President’s mandate to lose the prison. I remain at your disposal to assist with any questions you may have regarding Mr. Nasir.

Very Truly Yours,

Shelby Sullivan-Bennis

Reprieve US

Abdul Zahir’s Periodic Review Board

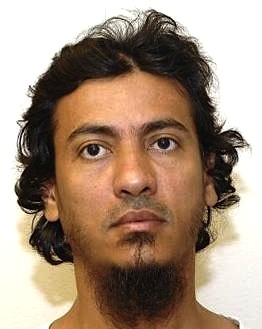

Two days after Abdul Latif Nasir’s PRB, on June 9, another review took place for Abdul Zahir (ISN 753), a 43- or 44-year old Afghan. As I explained in November 2010:

Two days after Abdul Latif Nasir’s PRB, on June 9, another review took place for Abdul Zahir (ISN 753), a 43- or 44-year old Afghan. As I explained in November 2010:

Zahir, who was captured in July 2002, was accused of being a translator for al-Qaeda member Abd al-Hadi al-Iraqi (ISN 10026) and a money courier for members of al-Qaeda and Taliban, and of taking part in a grenade attack on a vehicle carrying Toronto Star journalist Kathleen Kenna, her husband Hadi Dadashian, photographer Bernard Weil, and an Afghan driver in Zormat on March 4, 2002. Zahir was put forward for a trial by Military Commission in January 2006, when he stated that he did not take part in the grenade attack, and was the only one of the ten prisoners charged in the first incarnation of the Commissions who was not charged again after the Commissions were ruled illegal by Congress in June 2006, and were revived by Congress later that year.

On December 27, 2009, Kathleen Kenna, who was seriously injured in the attack, wrote an op-ed for the Toronto Star in which she wrote, “For almost eight years, we have all waited for justice. We don’t seek retribution. We’ve made it clear we cannot identify our attackers. We seek real justice, not a contrived justice. My conscience is divided: As a woman committed to social justice in everyday life, I want a public trial at a court where the defendant would enjoy the same rights to which we’re entitled under American and international law. As someone horribly wounded, then disabled, by the explosion, I want as fair a trial as possible at a time of war … We know nothing about Zahir’s arrest, but he was held at Guantánamo without charges for almost four years — far longer than is normally allowed under peacetime law. Unlike those awaiting criminal trials, Zahir was held without access to a lawyer of his choice, without a chance to tell his family his whereabouts. He wasn’t charged with war crimes until Jan. 2006: attacking civilians, aiding the enemy, and conspiracy. I don’t believe in indefinite detention without trial.”

However, what is noticeable about the unclassified summary for Zahir’s PRB is how there is no mention whatsoever of the grenade attack, from which it must be concluded that the US authorities no longer think that he had any involvement in it. In fact, as the summary makes clear, the authorities also acknowledge that, at the time of his capture, Zahir was “probably misidentified as [an] individual who had ties to al-Qa’ida weapons facilitation activities.”

As the summary stated, Abdul Zahir “was an Afghan insurgent captured by US military forces in July 2002 during a raid targeting an individual named Abdul Bari — an alias used by [Zahir] — who was believed to be involved in the production and distribution of chemical or biological weapons for al-Qa’ida. Because of Abdul Bari’s efforts to coordinate a shipment of unspecified items on behalf of the Taliban, US military forces targeted a compound in Hesarak village, Logar Province, Afghanistan, and captured [Zahir]. US forces recovered samples of unknown substances in the raid, including a white powder, that were initially believed to be chemical or biological agents, although other information later proved the samples to have been salt, sugar, and petroleum jelly.” Crucially, the summary stated, “While [Zahir] subsequently admitted during interviews to using the alias Abdul Bari on the phone — a fairly common name in the country — he ultimately provided no actionable information relative to al-Qa’ida’s weapons network, and we assess that AF-753 was probably misidentified as the individual who had ties to al-Qa’ida weapons facilitation activities.”

The summary proceeded to note that Zahir “probably worked as a bookkeeper and Arabic and Pashto translator from mid-to-late 1995 until late 2001 for al-Qa’ida military commander Abd al-Hadi al-Iraqi,” who arrived at Guantánamo in 2007. Rather confusingly, the summary also claimed that, “[d]uring this same time frame, [he] probably worked for an Afghan Taliban commander also named Abdul Hadi,” and that, “[f]rom at least as early as March 2002 until his July 2002 capture, he also probably served as a low-level member of a Taliban cell.”

The claims are all vague, all preceded by the use of the word “probably,” and it may be the case, therefore, that few, if any of the allegations are reliable. Equally vaguely, it was also stated that Zahir “may have been recruited to translate in several al-Iraqi-owned guesthouses in Kabul where he probably had limited access to senior leaders from al-Qa’ida and other extremist groups.” It was also noted that, while he “has admitted to working for al-Iraqi and the Taliban, he says that he was coerced to do so under threats to his family’s safety and he has denied any direct involvement with the Taliban outside of his role as a translator,” which may well be true, of course.

The authorities also noted that Zahir “has been moderately compliant with the staff at Guantánamo and has committed an average number of infractions relative to the full detainee population,” adding, “We assess he has minimal contact with the broader detainee population and has no official or unofficial leadership roles.” regarding interrogation, it was stated that he “was receptive to direct questioning and met semi-regularly with interrogators until September 2008, probably assessing that cooperation would increase the likelihood of being repatriated, and because he enjoyed the interaction afforded him during interviews.” Since that time, however, he “has not been interviewed,” providing the summary’s authors “with low confidence in our ability to assess his current mindset.”

However, the summary also noted that he “never made statements clearly endorsing or supporting al-Qa’ida — or other extremist ideologies — and since at least 2003 he has sought to distance himself from any allegiance to the group.” In addition, although he “has expressed frustration with the United States over his detention and his perception that he has been charged with a crime,” he “does not appear to view the US as his existential enemy.”

It was also noted that he “corresponds regularly with his immediate and extended family,” ad that his “patriarchal and tribal obligations could serve as a deterrent to reengagement should [he] view these commitments as more important commitments than reestablishing himself with the Taliban or other extremists.”

Below I’m posting the opening statements of one of his personal representatives (military personnel appointed to help the prisoners prepare for their PRBs) and of his attorney, Robert Gensburg. The personal representative, who noted that he has become a poet in Guantánamo, also explained that he had said that “he knows that what he did in the past was wrong, but at the time he was only concerned with feeding his children,” adding, “He now realizes that his work was not legitimate and has expressed regret for his past decisions.” The expression of remorse is a key element in the review board’s deliberations, and it is to be hope that Zahir himself also made this clear in his discussion with the board members. For his part, Robert Gensburg, who has represented Zahir for over ten years, spoke about his client “has always been polite, calm, friendly and kind to me and the several colleagues who have worked with me on his case,” and is “uncommonly intelligent and thoughtful.”

Periodic Review Board Initial Hearing, 09 Jun 2016

Abdul Sahir [Zahir], ISN 753

Personal Representative Opening Statement

Good morning, ladies and gentlemen of the board. I am the Personal Representative for ISN 753. Thank you for the opportunity to present Abdul Zahir’s case this morning.

Abdul has been extremely polite and cooperative from the beginning and has attended all meetings with his Personal Representative. He has become a poet during his time here at Guantánamo Bay and has written many poems, some of which have been submitted to the Board. He has spent a lot of time preparing for this board and has put a great amount of effort into his thoughts and the book that he has developed that he refers to as his “Future Plans.” We have submitted a portion of this book as well to show a little bit about how he views the world now.

Abdul has told me that he knows that what he did in the past was wrong, but at the time he was only concerned with feeding his children. He now realizes that his work was not legitimate and has expressed regret for his past decisions. Based on our conversations, I believe that he is not quite as naive as he once was and has grown and learned during his time here at GTMO and will not make the same mistakes again. His only thoughts now are for his two wives and his three children, and the future he hopes to have with them. He is willing to go to any country, but would prefer an Arab country if possible. However more importantly, he wishes to go someplace where it is legal for him to have two wives, because despite his permission for them to leave him and remarry, they have remained faithful to him and he could not bear to leave either behind. He does of course realize that being reunited might take a while and he is prepared to wait as long as he must.

He has support from his family and village as is evident from the many documents we received pledging support. I believe that Abdul Zahir’s desire to pursue a better way of life if transferred from Guantánamo is genuine and that he does not represent a continuing or significant threat to the United States of America.

Thank you for your time and attention. I am pleased to answer any questions you may have throughout these proceedings.

Robert Gensburg’s submission

To: Periodic Review Board

In re: Abdul Zahir, ISN 753

My name is Robert Gensburg. I practice law in Saint Johnsbury, Vermont. I have represented Abdul Zahir, ISN 753, since 2005, when I filed a petition for a writ of habeas corpus on his behalf. I respectfully submit that continued law of war detention of Abdul Zahir is not necessary to protect against a continuing significant threat to the security of the United States.

Abdul Zahir is a now 43 or 44 year old citizen of Afghanistan. He has three sons. His oldest son is twenty, and he has never seen the youngest. [A footnote read, “The case file that has been submitted to you includes pictures of his sons with their grandfather, Abdul Zahir’s father-in-law”]. He supported his family doing odd jobs: driving a taxi, sheep herding, and eventually becoming a full time translator between his government and Abd al Hadi al Iraqi, one of the high value detainees. It is Abdul Zahir’s association with al Iraqi that landed him in Guantánamo.

In July of 2002, Abdul Zahir was taken into custody at his home in rural Logar province by United States Army forces. He was held at the Bagram Air Force base prison through October, and then transported to Guantánamo in October of that year. The case file that has been submitted to you accurately describes his behavior during the 14 years of his detention, and I will not belabor that here. While in Guantánamo he developed significant and permanent physical problems, which are cursorily described in the case file. Abdul Zahir also suffers from mental health problems, which lately appear to have been brought under control.

Throughout the 11 years of my association with Abdul Zahir, he has always been polite, calm, friendly and kind to me and the several colleagues who have worked with me on his case. He is uncommonly intelligent and thoughtful, although I think he still does not completely understand why lawyers or personal representatives would take up his cause against their own government. At our initial meeting in early 2006 (and today), I was struck by and came to deeply respect his strong moral compass that has been formed by his devotion to Islam.

The letters of support for Abdul Zahir that are included in the case file demonstrate that he will have very strong support in his community and his family upon his return. I suggest that you should attribute particular importance to the statement of support from Abdul Bari Jahani, Afghanistan’s recently appointed Minister of Information and Culture. Minister Jahani is a renowned poet and scholar. He translated for us on some of our conferences with Abdul Zahir, which thrilled our client (and my colleagues and me, too). Minister Jahani was as taken with Abdul Zahir as I was.

I know that the Periodic Review process is a forward looking process, and not a process for rehashing history and protesting innocence. I think it is important for the Board to know, however, that from day one Abdul Zahir has consistently tried to have a hearing before some neutral judge or commission to determine the validity of the claims that the government has made about him. There has been no effort to hide from or avoid those claims. I’ve had literally years of discussions with the Office of Military Commissions and the United States Attorney’s office for the Eastern District of New York about Abdul Zahir being given what Judge Henry Friendly called “some kind of hearing.” [See 123 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1267 (1975)] I’ve twice written to the OMC convening authority requesting that she and then he charge Abdul Zahir with something, and similarly to General Martins when he was appointed chief prosecutor. Abdul Zahir has been prepared to face the government’s claims in any forum for the last 14 years. Had he been given that hearing, it would have become obvious that he does not pose a threat, significant or otherwise, to the security of the United States.

Abdul Zahir’s life has been irretrievably damaged. He wants nothing more today than to return to his home and family, to reassemble some kind of normalcy, and to live in peace. As I wrote in the first paragraph, continued law of war detention of Abdul Zahir is not necessary to protect against a continuing significant threat to the security of the United States. I urge the Board to recommend that Abdul Zahir be cleared for release and return to his home and family.

Yours truly,

Robert A. Gensburg

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ is available for download or on CD via Bandcamp — also see here). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ is available for download or on CD via Bandcamp — also see here). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

June 13, 2016

Video: RT America’s One-Hour Special on Guantánamo Featuring Andy Worthington, Joe Hickman, Nancy Hollander and Tom Wilner

Last week, I was delighted to take part in an hour-long Guantánamo special on RT America, presented by Simone del Rosario, who had recently visited the prison. Simone began by noting that it was the tenth anniversary of three deaths at Guantánamo — 22-year old Yasser Talal al-Zahrani, a Saudi, who was just 17 years old when he was seized in Afghanistan at the end of 2001, 37-year old Salah Ahmed al-Salami (aka Ali al-Salami), a Yemeni, and 30-year old Mani Shaman al-Utaybi, another Saudi.

Last week, I was delighted to take part in an hour-long Guantánamo special on RT America, presented by Simone del Rosario, who had recently visited the prison. Simone began by noting that it was the tenth anniversary of three deaths at Guantánamo — 22-year old Yasser Talal al-Zahrani, a Saudi, who was just 17 years old when he was seized in Afghanistan at the end of 2001, 37-year old Salah Ahmed al-Salami (aka Ali al-Salami), a Yemeni, and 30-year old Mani Shaman al-Utaybi, another Saudi.

The deaths were described by the authorities as a triple suicide, but there have always been doubts about that being feasible — doubts that were particularly highlighted in 2010, when the law professor and journalist Scott Horton wrote an alternative account for Harper’s Magazine, “The Guantánamo Suicides,” that drew in particular on a compelling counter-narrative presented by Staff Sgt. Joseph Hickman, who had been in the prison at the time of the men’s deaths, monitoring activities from the guard towers. Hickman’s book Murder in Camp Delta was published in January 2015, and he was also a contributor to RT America’s show.

After this opening, the show dealt in detail with the case of Mohamedou Ould Slahi, Mauritanian national, torture victim and best-selling author (of Guantánamo Diary). Slahi is one of the prisoners still held who were designated for prosecution by the Guantánamo Review Task Force that President Obama established shortly after first taking office in January 2009, until the basis for prosecutions largely collapsed after a number of critical appeals court rulings and he was, instead, put forward for a Periodic Review Board, the latest review process, which began at the end of 2013. Slahi’s PRB took place on June 2, and, in discussing his case, Simone del Rosario also spoke to one of his attorneys, Nancy Hollander.

The full video of the show is below, via YouTube, and I urge you to watch it if you have the time, and to share it if you find it useful:

After the section on Mohamedou Ould Slahi, Simone del Rosario discussed the prison blocks that still exist at Guantánamo — the isolation cells of Camp 5, and Camp 6 with its communal spaces — and spoke to a guard who seemed to break with the military’s efforts at brainwashing by acknowledging that he saw the prisoners as human beings who responded to good and bad treatment as any human being would.

Joseph Hickman was interviewed next, and after that Simone del Rosario turned her attention to the allegations of recidivism — of prisoners “returning to the battlefield” — that have done so much damage during the Obama presidency, as parts of the machinery of government — in the Pentagon and the office of the Director of National Intelligence — have regularly claimed that around 15 percent of the men released from Guantánamo are “confirmed” recidivists, and a similar percentage are “suspected” of recidivism. The two numbers are generally bundled up together by mainstream media outlets, demonstrating a fundamental betrayal of the principles of journalism, and it is also generally overlooked that the authorities provide zero evidence to back up their claims, which, it is completely appropriate to say, are seriously exaggerated.

This was part of what I was asked to discuss, in my segment that began around 33 minutes into the show. I also ran through the story of who is currently held, and explained why they are, fundamentally, political prisoners, and I also explained how this essentially dates back to the original basis of the “war on terror,” when, with breathtaking arrogance, the Bush administration decided that it was going to hold human beings with no rights whatsoever, holding them neither as criminal suspects nor as prisoners of war.

My interview, also via YouTube, is below, for anyone interested in seeing it as a stand-alone piece:

My interview was followed by an interview with Tom Wilner, with whom I co-founded the Close Guantánamo campaign in 2012. Tom represented the Kuwaiti prisoners held at Guantánamo, and was also Counsel of Record to the prisoners as they petitioned the Supreme Court to grant them habeas corpus rights — efforts which were successful twice, in June 2004, in a victory that allowed lawyers to begin representing the men held at Guantánamo, even though Congress subsequently moved to block the men’s habeas rights, and in June 2008, when the Supreme Court rebuked Congress for having acted unconstitutionally, and granted them constitutionally guaranteed habeas rights.

However, although the 2008 ruling led to dozens of prisoners securing their release after District Court judges ruled on their habeas petitions, telling the government that they had failed to establish that they were connected to Al-Qaeda or the Taliban, politically motivated appeals court judges in Washington, D.C. began overturning or vacating those rulings, and changed the rules regarding the habeas petitions — telling the lower court judges that everything the government alleged was to be treated as presumptively accurate — so that, since July 2010, not a single habeas corpus petition has been won by the prisoners.

Disgracefully, the Supreme Court has repeatedly failed to confront this injustice, but, as Tom explained, one route out of the impasse ought to be for the Obama administration to allow an appeal to be heard by the full, en banc appeals court in Washington, D.C., which is now less dominated by profoundly conservative judges that it was in 2010-11.

At the end of the show, three more lawyers were interviewed — Gary Thompson, who represents Ravil Mingazov, a Russian citizen also facing a Periodic Review Board (on June 24), and military defense lawyer James Connell and his colleague Alka Pradhan, who represent “high-value detainee” Ammar al-Baluchi (aka Ali Abd al-Aziz Ali), one of the alleged 9/11 co-conspirators facing a trial by military commission. All three spoke eloquently about the failures of justice since the “war on terror” began, with Connell, in particular, noting how, disgracefully, the makers of the Hollywood film Zero Dark Thirty were given more information about his case than his lawyers.

My thanks to RT America for producing this show, which, as often with RT, is the sort of program that mainstream US media should be producing, but which, of course, is spectacularly lacking on the main US networks.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ is available for download or on CD via Bandcamp — also see here). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ is available for download or on CD via Bandcamp — also see here). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

June 11, 2016

Radio: Andy Worthington’s Hour-Long Guantánamo Interview on Wake-Up Call Podcast

Please support my work!

Please support my work!

Have an hour to spare? Want to hear me talk in detail about Guantánamo? Then please listen to me on Wake-Up Call Podcast with Adam Camac and Daniel Laguros, who “interview experts on foreign relations, economics, current events, politics, political theory, and more every weekday.”

They decided to call the show “The Horrible Guantánamo Bay Facility,” which I think is accurate, as I was able to explain in detail what a thoroughly disgraceful facility Guantánamo is at every level.

I began by explaining why the naval base at Guantánamo Bay was chosen as the location for an offshore facility that was supposed to be beyond the reach of the US courts, and how, of course, creating somewhere outside the law made it shamefully easy to begin torturing the men — and boys — who were swept up in the “war on terror” and held there.

See below for the interview on YouTube (and you can also listen to it here):

Following the introductory comments I mentioned above, I spoke about how the fundamental problem with the Bush administration’s detention policies in the “war on terror” was that, in seeking to establish a way of holding people without any rights whatsoever as human beings, senior officials decided, unwisely, that there was a third way to hold people beyond the established routes — that they are charged with a criminal offence and put on trial, or are taken off the battlefield, and held unmolested, with the protections of the Geneva Conventions, until the end of hostilities.

I proceeded to speak about the prisoners’ long struggle to secure habeas corpus rights, and how, briefly, that led to the release of dozens of prisoners, until politically motivated appeals court judges changed the rules governing the prisoners’ habeas petitions, effectively gutting habeas corpus of all meaning for those held at Guantánamo.

I then spoke about the forms of torture implemented at Guantánamo, and moved on from that to the shameful history of the military commissions, which have failed, throughout Guantánamo’s history, to deliver anything resembling justice to the handful of men who have faced trials. I also discussed the long and so far unsuccessful quest for accountability for the senior officials, up to and including George W. Bush, Dick Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld and their lawyers, who implemented the torture, rendition and indefinite detention without charge or trial that were at the heart of the detention policies in the “war on terror.”

I proceeded to discuss how competent tribunals (also known as battlefield tribunals), to separate combatants from civilians, were not implemented in the “war on terror,” and how this was just one of the many mistakes that led to people being held at Guantánamo who were not even soldiers, let alone terrorists, and how, of course, the Bush administration’s disastrous policies dangerously and irresponsibly blurred the differences between civilians, soldiers and terrorists.

I also spoke about the story of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in Guantánamo, freed last year as the result of a multi-faceted campaign, including my own contribution via the We Stand With Shaker campaign that I co-founded with activist Joanne McInnes in 2014, and, in connection with Shaker’s story, I also explained why the classified military files released by WikiLeaks in 2011 are full of profoundly unreliable statements made by prisoners who were subjected to torture or other forms of abuse, or were bribed to make statements with the promise of enter living conditions.

I also ran through the history of Guantánamo under President Obama, explaining how unprincipled opposition from Republicans, combined with Obama’s reluctance to spend political capital overcoming those obstacles, has left him with less than six months to fulfil the promise he made on his second day in office, nearly seven and a half years ago, to close Guantánamo within a year.

There was much more in the show than I have described above, and I hope you have time to listen to it, and to share it if you find it useful.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ is available for download or on CD via Bandcamp — also see here). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ is available for download or on CD via Bandcamp — also see here). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

June 8, 2016

Quarterly Fundraiser Day 3: Your Support is Vital for My Guantánamo Work – $3200 ($2200) Still Needed!

Please support my work!

Please support my work!

Dear friends and supporters,

I know times are tough all round, but I’m in desperate need of support from you to finance my ongoing project to call for the closure of the prison at Guantánamo Bay through my independent journalism, my research, commentary, public appearances, media appearances, and social media work. Most of this work is unpaid — or, to be more accurate, is reader-funded. Without your support, I cannot continue to do what I’ve been doing for the last ten years. I have no institutional backing, and no mainstream media operation behind me.

Since launching my latest fundraiser on Monday, I have received $300 (£200) in donations, but I’m still trying to raise another $3300 (£2200). That’s just $270 (£185) a week for the next three months — not a huge amount, I hope, for all the work that I do to try and bring to an end the long-standing disgrace and injustice that the prison at Guantánamo is, and will be until it is closed once and for all.

So please, if you can help out at all, click on the “Donate” button above to donate via PayPal (and I should add that you don’t need to be a PayPal member to use PayPal). You can also make a recurring payment on a monthly basis by ticking the box marked, “Make This Recurring (Monthly),” and if you are able to do so, it would be very much appreciated.

Any amount will be gratefully received, whether it is $25, $100 or $500 — or any amount in any other currency (£15, £50 or £250, for example). PayPal will convert any currency you pay into dollars, which I chose as my main currency because the majority of my supporters are in the US.

Readers can pay via PayPal from anywhere in the world, but if you’re in the UK and want to help without using PayPal, you can send me a cheque (address here — scroll down to the bottom of the page), and if you’re not a PayPal user and want to send cash from anywhere else in the world, that’s also an option. Please note, however, that foreign checks are no longer accepted at UK banks — only electronic transfers. Do, however, contact me if you’d like to support me by paying directly into my account.

With just 225 days left for President Obama to close Guantánamo, I’ll be doing what I can to educate people about the need for the prison to be closed before he leaves office — via the Countdown to Close Guantánamo that I launched in January, and also via my current focus on the Periodic Review Boards at Guantánamo, which are currently reviewing the cases of the many dozens of prisoners who, six years ago, were described by a US review process as “too dangerous to release.” That has turned out to be a rather disgraceful exaggeration, because, currently, 24 of the 33 men whose cases have been decided have been recommended for release.

You can see all my recent articles on the PRBs here and here, and you can also rest assured that, with your help, I will continue to do all I can to get the prison at Guantánamo closed once and for all.

Andy Worthington

London

June 8, 2016

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ is available for download or on CD via Bandcamp — also see here). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).