Andy Worthington's Blog, page 70

August 21, 2016

Obama Releases 15 Prisoners from Guantánamo to UAE; Just 61 Men Now Left (Part 1 of 2)

There was good news from Guantánamo last week, as 15 men were released, to begin new lives in the United Arab Emirates. The release was the largest single release of prisoners under President Obama, and takes the total number of men held at Guantánamo down to 61, the lowest level it has been since the prison’s first few weeks of its operations, in January 2002.

There was good news from Guantánamo last week, as 15 men were released, to begin new lives in the United Arab Emirates. The release was the largest single release of prisoners under President Obama, and takes the total number of men held at Guantánamo down to 61, the lowest level it has been since the prison’s first few weeks of its operations, in January 2002.

12 of the 15 men released are Yemenis, while the remaining three are Afghans. All had to have third countries found that would offer them new homes, because the entire US establishment refuses to repatriate any Yemenis, on the basis that the security situation in Yemen means they cannot be adequately monitored, and Afghans cannot be repatriated because of legislation passed by Congress. The UAE previously accepted five Yemenis prisoners from Guantánamo last November.

Of the 15 men, six — all Yemenis — were approved for release back in 2009 by the high-level, inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force that President Obama established shortly after taking office for the first time. This article tells the stories of those six men, while another article to follow will tell the stories of the other nine.

The six were part of a group of 30 Yemenis who were approved for release by the task force, but were then placed in a sub-category of “conditional detention” — conditional on a perceived improvement in the security situation in Yemen. No indication was given as to how this would be decided, and as a result those in the “conditional detention” group languished until the Obama administration began finding countries that would offer new homes to them, a process that only began last November and that, before last week’s releases, had led to 19 men being given new homes — in the UAE, Ghana, Oman, Montenegro and Saudi Arabia. Now just five men from this group are left.

The first of the six, Mohammed al-Adahi (ISN 033), born in 1962, and identified by the US as Muhammad Ahmad Said al-Adahi, was seized by Pakistani soldiers after accompanying his sister to Afghanistan to be married. As I explained in 2007 in my book The Guantánamo Files:

The first of the six, Mohammed al-Adahi (ISN 033), born in 1962, and identified by the US as Muhammad Ahmad Said al-Adahi, was seized by Pakistani soldiers after accompanying his sister to Afghanistan to be married. As I explained in 2007 in my book The Guantánamo Files:

Married with two children, al-Adahi had never left Yemen until August 2001, when he took a vacation from the oil company where he had worked for 21 years to accompany his sister to meet her husband … As he told his tribunal [his Combatant Status Review Tribunal, a cursory review system established by the Bush administration in July 2004], “In Muslim society, a woman does not travel by herself.” After flying to Karachi, they traveled to Kandahar, where his brother-in-law was living. Al-Adahi stayed in Afghanistan for a month, “to ease his sister’s transition to life in Afghanistan,” and then made his way back to Pakistan, where he was arrested by soldiers while traveling on a bus. “They were capturing everybody with Arabic features,” he said. “I gave them my passport and that shows that I’m an Arab. They said, ‘why don’t you follow us, we need you at the Center.’ From that point on they brought us over here.”

It had always struck me as ridiculous that al-Adahi was not released, and, exactly seven years ago, on August 21, 2009, a US District Court judge, Gladys Kessler, agreed. As I wrote at the time:

Judge Kessler explained, “There is no question that the record fully supports the Government’s allegation that Petitioner had close familial ties to prominent members of the jihad community in Afghanistan.” The brother-in-law, it appears, was “a prominent man in Kandahar,” who had fought the Russians in Afghanistan, and Judge Kessler also noted that it was “undisputed” that Osama bin Laden “hosted and attended [the] wedding reception in Kandahar,” that al-Adahi “was briefly introduced to bin Laden,” and that “A few days later, al-Adahi met bin Laden again and the two chatted briefly about religious matters in Yemen.”

However, Judge Kessler refused to accept the government’s contention that these familial ties and the two brief meetings with bin Laden proved that al-Adahi “was part of the inner circle of the enemy organization al-Qaeda,” and accepted instead that there was no reason to doubt that al-Adahi’s visit was, as he stated, to accompany his sister to her wedding (and also to receive medical treatment for a back problem). She noted also that he had not tried to hide the fact that he had met bin Laden, and that he had, in addition, stated that it was “common for visitors to Kandahar” to do so.

As in May [2009], when she granted the habeas appeal of another Yemeni, Alla Ali Bin Ali Ahmed, Judge Kessler had serious doubts about the manner in which the government established its case, which focused primarily on its claim that its various allegations should be considered as part of a “mosaic” of intelligence, to be viewed as a whole, rather than being examined in isolation. Dismissing this approach, she stated that, although she understood that “use of this approach is a common and well-established mode of analysis in the intelligence community … at this point in this long, drawn-out litigation the Court’s obligation is to make findings of fact and conclusions of law which satisfy appropriate and relevant legal standards as to whether the Government has proven by a preponderance of the evidence that the Petitioner is justifiably detained.”

Judge Kessler also made reference to two unreliable witnesses in al-Adahi’s case, who were revealed, in his classified military file, which was subsequently released by WikiLeaks, as two of the most well-known unreliable witnesses at Guantánamo — Abd al-Hakim Bukhari (ISN 493), a Saudi tortured by Al-Qaeda as a spy, who “identified [him] as a supervisor in UBL’s security forces,” and Abd al-Rahim Janko (ISN 489), a Syrian who was also tortured by Al-Qaeda as a spy, who “identified [him] as a trainer at the al-Faruq [aka al-Farouq] Training Camp.”

The WikiLeaks file also revealed that al-Adahi has been very ill during his 14 years at Guantánamo, noting that he was “on a list of high-risk detainees from a health perspective,” and that, although he “is in fair health,” he “has chronic stable medical problems”: “hypertension, hyperlipidemia, migraine headaches, asthma, and gastro-esophageal reflux,” as well as “a history of depression and schizoaffective personality disorder.”

The second of the six “conditional detention” prisoners, Abdel Qadir al-Mudafari (ISN 040) aka Abdel Qadir al-Mudhaffari, who was born in 1976, was regarded by the US authorities as one of the so-called “Dirty Thirty,” allegedly bodyguards for Osama bin Laden, who were seized by Pakistani soldiers after crossing from Afghanistan into Pakistan in December 2001. The “Dirty Thirty” scenario was always suspicious, however, primarily because so many of the men in question had been in Afghanistan for such a short amount of time that it was inconceivable that they would have been trusted with protecting al-Qaeda’s leader.

The second of the six “conditional detention” prisoners, Abdel Qadir al-Mudafari (ISN 040) aka Abdel Qadir al-Mudhaffari, who was born in 1976, was regarded by the US authorities as one of the so-called “Dirty Thirty,” allegedly bodyguards for Osama bin Laden, who were seized by Pakistani soldiers after crossing from Afghanistan into Pakistan in December 2001. The “Dirty Thirty” scenario was always suspicious, however, primarily because so many of the men in question had been in Afghanistan for such a short amount of time that it was inconceivable that they would have been trusted with protecting al-Qaeda’s leader.

As I described it in a profile I wrote in September 2010, according to the US authorities al-Mudafari “apparently stated that he wanted a struggle or jihad and chose to travel to Afghanistan rather than Palestine,” but was subjected to several dubious allegations (beyond the most obvious — that he was a bodyguard for Osama bin Laden). It was also alleged that he was “identified as a trainer” at al-Farouq, and it was also stated that he was identified by “an al-Qaeda operative” as being “a friend of Osama bin Laden’s personal secretary,” and was also “identified as being at a Taliban Supreme Leader’s [sic] compound.” Confusing matters were notes that he had received instruction in Yemen from Sheikh Muqbil al-Wadi (who was actually opposed to bin Laden), his own claims that he traveled to teach the Koran, and a claim by another unidentified source, who “stated that he did not think that the detainee ever fought with the Taliban because he was against the Taliban.”

Further details about these dubious allegations can be found in his classified military file, released by WikiLeaks in 2011.

The third “conditional detention” prisoner is Mohsen Aboassy (ISN 091), identified by the US authorities as Abdul al-Saleh or Abd al-Muhsin Abd al-Rab Salih al-Busi.

Born in 1979, Aboassy was a survivor of the Qala-i-Janghi massacre in November 2001, which, as I described it in an article in September 2010, “followed the surrender of the northern city of Kunduz, when several hundred Taliban foot soldiers — and, it seems, a number of civilians — all of whom had been told that they would be allowed to return home if they surrendered, were taken to a fortress run by General Rashid Dostum of the Northern Alliance. Fearing that they were about to be killed, a number of the men started an uprising, which was suppressed by the Northern Alliance, acting with support from US and British Special Forces, and US bombers. Hundreds of the prisoners died, but around 80 survived being bombed and flooded in the basement of the fort, and around 50 of these men ended up at Guantánamo.”

In that article, I also explained how:

[A]l-Saleh [Aboassy] said that he had answered a fatwa calling for young men to travel to Afghanistan, but felt that “the Taliban cheated him because he was fighting the Northern Alliance, which was not a cause that he believed in; therefore, it was not really a jihad for him.” He also denied knowing any members of al-Qaeda, and stated that, if returned to Yemen, he would “get married” and would “disregard anyone who suggests that he fight jihad.”

In a phone call just before his release, he told his lawyer, Shelby Sullivan-Bennis, of Reprieve, “Over the time that I have been in Guantánamo, thirteen children have been born in my family. I miss playing with my nephews and nieces. I have a photograph of them and when I get sad, I look at the photo to cheer myself up. After almost fourteen years in Guantánamo I realise that when I leave this place it will just be a bad memory. Determination, will, and ambition will overcome any ordeal and any difficulty.”

Sullivan-Bennis also stated, “Mohsen, whose favorite movie is Kung Fu Panda, has never, for a moment, been a threat to our national security — something the Obama administration realized nine long years ago when it cleared him for release. Yet there he languished, a fate lived by many Yemeni detainees, while the government took its time finding him a suitable country in which to resettle. It is to his credit that he is full of enthusiasm; excited about his new life in the United Arab Emirates, about reconnecting with his family and about becoming a carpenter. How many of us could cope so well with such a senseless ordeal? What might Mohsen have achieved had he not lost fifteen years of his life? How many more lives are going to be wasted at Guantánamo Bay?”

She also noted how he had stated in his recent phone call, “I would like to be a carpenter. I used to work like one here at Gitmo so I have learned things. I have used cardboard to make things like shelves and desks and so on. Making these things out of cardboard is very difficult. Outside, I will have wood and tools to make things so it will be easier.”

The fourth of the “conditional detention” prisoners to be released is Abd al-Rahman Sulayman (ISN 223) aka Abdul Rahman Sulayman, born in 1979, whose habeas corpus petition was turned down by a US judge in 2010, the same year that President Obama’s task force recommended his release if security concerns could be met.

The fourth of the “conditional detention” prisoners to be released is Abd al-Rahman Sulayman (ISN 223) aka Abdul Rahman Sulayman, born in 1979, whose habeas corpus petition was turned down by a US judge in 2010, the same year that President Obama’s task force recommended his release if security concerns could be met.

As I explained at the time, Sulayman had claimed that a facilitator for jihad in Afghanistan, Ibrahim Baalawi, had recruited him under false pretences with tales of the good life in Afghanistan. I wrote:

He “promised me that I’d be able to get married in Afghanistan. He may have had different intentions for me other than the marriage, but I didn’t know,” he [Sulayman] told his tribunal, adding that he was also told, “you can go to certain counties and they’ll give you a house, even if it’s an old house, and some financial assistance to get married. That’s without having to contribute anything at all. It’s a charity type of thing from these people. If you put yourself in my shoes, what would you do?”

However, in Sulayman’s habeas ruling in July 2010, Judge Reggie Walton turned down his petition after concluding, from his admission that he had attended the Taliban’s second lines, where he had received some weapons training, that, as I described it:

[H]e had been “part of” al-Qaeda or the Taliban, which is all that is required for the prisoners to lose their habeas petitions, even though much of the other supposed evidence was demonstrably false, and almost certainly produced by unreliable witnesses, either in Guantánamo or in other US-run prisons. These included ludicrous allegations that he was identified as a mortar instructor from a video made in the Tarnak Farms training camp in 2000 (before he arrived in Afghanistan), that he “was identified as an al-Qaeda spokesman and was part of Osama bin Laden’s entourage … during the escape from Tora Bora,” and that he was identified as a Taliban prison guard “who used torture techniques on inmates under his control.”

Further information about these claims can be found in his WikiLeaks file.

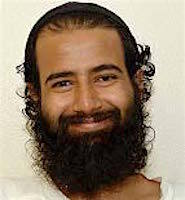

The fifth “conditional detention” prisoner to be released is Mohammed Khusruf (ISN 509), also identified as Mohammed Nasir Yahi Khussrof Kazaz, who was one of Guantánamo’s oldest prisoners. Born in February 1950, he was 66 years old at the time of his release.

The fifth “conditional detention” prisoner to be released is Mohammed Khusruf (ISN 509), also identified as Mohammed Nasir Yahi Khussrof Kazaz, who was one of Guantánamo’s oldest prisoners. Born in February 1950, he was 66 years old at the time of his release.

As I explained in an article in September 2010:

Khusruf, who was seized after a bombing raid in the Tora Bora region, said that he went to Afghanistan to teach the Koran, and asked, “Is it really reasonable that al-Qaeda or the Taliban, in bad need of men to fight, have to go to Yemen to find men at 60 years old to fight? Is this logical?” (according to US records, he was actually 51 years old at the time of his capture). He admitted training at al-Farouq, but said that he only did so because the man who arranged his travel told him he needed to be able to defend himself. He also explained that, after his arrest, he was moved from a jail in Jalalabad to “an underground prison” in Kabul — possibly the CIA’s “Dark Prison,” or else an Afghan jail — where “they would interrogate and beat us.” He added that those who were wounded “were also there” — presumably some of the other men rounded up in the Tora Bora region, who also ended up in Guantánamo.

The final “conditional detention” prisoner to be released is Jamil Nassir (ISN 728) aka Abdul Muhammad Ahmad Nassar al-Muhajari, who, it seems, had traveled to Afghanistan with his wife and children, and had ended up working for Al-Wafa, a charity once regarded by the US authorities as a front for terrorism, although those claims have evidently collapsed over the years, as almost all of the dozens of prisoners allegedly connected with Al-Wafa have been released.

The final “conditional detention” prisoner to be released is Jamil Nassir (ISN 728) aka Abdul Muhammad Ahmad Nassar al-Muhajari, who, it seems, had traveled to Afghanistan with his wife and children, and had ended up working for Al-Wafa, a charity once regarded by the US authorities as a front for terrorism, although those claims have evidently collapsed over the years, as almost all of the dozens of prisoners allegedly connected with Al-Wafa have been released.

As I explained in an article in October 2010, Nasser —presumably after making sure his wife and children safely escaped Afghanistan following the US-led invasion — accepted an offer of safe passage to a house in Faisalabad with two other refugees, Labed Ahmed (an Algerian, released in November 2008) and Ravil Mingazov, a Russian whose release was recommended by a Periodic Review Board just last month, where, they were told, it would be easier for them to leave the country.

As I proceeded to explain:

After being accidentally delivered to Shabaz Cottage, where [the alleged “high-value detainee”] Abu Zubaydah [for whom the US’s post-9/11 torture program was first developed] was living (and where Ahmed insisted on staying), Mingazov and Nasser were then moved to the Crescent Mill guest house, where they were seized after about ten days. Any doubts about [their] innocence should have been removed not just by the ruling but also because, during a military review board at Guantánamo, Labed Ahmed had stated that, because he, Mingazov and Nassir “did not have a connection or relationship with Abu Zubaydah,” they “should have been placed in the Yemeni house.” As I have explained previously, “This indicates that, although Abu Zubaydah had some sort of contact with the [Crescent Mill guest] house, it was not a place that had any connection with terrorism, and was, at best, a place where a few foreigners fleeing from Afghanistan could be concealed alongside a group of students.”

Nevertheless, over the years Nassir had to contend with a number of outrageous allegations — that, as I described it in 2010, he “had rented a house next door to Mullah Omar, the leader of the Taliban,” and that he was linked by unknown sources to “the purchase of equipment used to assist al-Qaeda operatives in the production of biological weapons,” an allegation was levelled at numerous prisoners allegedly associated with Al-Wafa. As I also explained in 2010, “in light of his own claim that he traveled from Pakistan to Afghanistan to study and teach the Koran, it may be that the most reliable unidentified source is the one who stated that he was ‘not a guard nor affiliated with al-Qaeda,’ but a civilian who had ‘moved to Afghanistan with his wife and children.’”

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album ‘Love and War’ and EP ‘Fighting Injustice’ are available here to download or on CD via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album ‘Love and War’ and EP ‘Fighting Injustice’ are available here to download or on CD via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

See the following for articles about the 142 prisoners released from Guantánamo from June 2007 to January 2009 (out of the 532 released by President Bush), and the 161 prisoners released from February 2009 to June 2016 (by President Obama), whose stories are covered in more detail than is available anywhere else –- either in print or on the internet –- although many of them, of course, are also covered in The Guantánamo Files, and for the stories of the other 390 prisoners released by President Bush, see my archive of articles based on the classified military files released by WikiLeaks in 2011: June 2007 –- 2 Tunisians, 4 Yemenis (here, here and here); July 2007 –- 16 Saudis; August 2007 –- 1 Bahraini, 5 Afghans; September 2007 –- 16 Saudis; 1 Mauritanian; 1 Libyan, 1 Yemeni, 6 Afghans; November 2007 –- 3 Jordanians, 8 Afghans; 14 Saudis; December 2007 –- 2 Sudanese; 13 Afghans (here and here); 3 British residents; 10 Saudis; May 2008 –- 3 Sudanese, 1 Moroccan, 5 Afghans (here, here and here); July 2008 –- 2 Algerians; 1 Qatari, 1 United Arab Emirati, 1 Afghan; August 2008 –- 2 Algerians; September 2008 –- 1 Pakistani, 2 Afghans (here and here); 1 Sudanese, 1 Algerian; November 2008 –- 1 Kazakh, 1 Somali, 1 Tajik; 2 Algerians; 1 Yemeni (Salim Hamdan), repatriated to serve out the last month of his sentence; December 2008 –- 3 Bosnian Algerians; January 2009 –- 1 Afghan, 1 Algerian, 4 Iraqis; February 2009 — 1 British resident (Binyam Mohamed); May 2009 —1 Bosnian Algerian (Lakhdar Boumediene); June 2009 — 1 Chadian (Mohammed El-Gharani); 4 Uighurs to Bermuda; 1 Iraqi; 3 Saudis (here and here); August 2009 — 1 Afghan (Mohamed Jawad); 2 Syrians to Portugal; September 2009 — 1 Yemeni; 2 Uzbeks to Ireland (here and here); October 2009 — 1 Kuwaiti, 1 prisoner of undisclosed nationality to Belgium; 6 Uighurs to Palau; November 2009 — 1 Bosnian Algerian to France, 1 unidentified Palestinian to Hungary, 2 Tunisians to Italian custody; December 2009 — 1 Kuwaiti (Fouad al-Rabiah); 2 Somalis; 4 Afghans; 6 Yemenis; January 2010 — 2 Algerians, 1 Uzbek to Switzerland; 1 Egyptian, 1 Azerbaijani and 1 Tunisian to Slovakia; February 2010 — 1 Egyptian, 1 Libyan, 1 Tunisian to Albania; 1 Palestinian to Spain; March 2010 — 1 Libyan, 2 unidentified prisoners to Georgia, 2 Uighurs to Switzerland; May 2010 — 1 Syrian to Bulgaria, 1 Yemeni to Spain; July 2010 — 1 Yemeni (Mohammed Hassan Odaini); 1 Algerian; 1 Syrian to Cape Verde, 1 Uzbek to Latvia, 1 unidentified Afghan to Spain; September 2010 — 1 Palestinian, 1 Syrian to Germany; January 2011 — 1 Algerian; April 2012 — 2 Uighurs to El Salvador; July 2012 — 1 Sudanese; September 2012 — 1 Canadian (Omar Khadr) to ongoing imprisonment in Canada; August 2013 — 2 Algerians; December 2013 — 2 Algerians; 2 Saudis; 2 Sudanese; 3 Uighurs to Slovakia; March 2014 — 1 Algerian (Ahmed Belbacha); May 2014 — 5 Afghans to Qatar (in a prisoner swap for US PoW Bowe Bergdahl); November 2014 — 1 Kuwaiti (Fawzi al-Odah); 3 Yemenis to Georgia, 1 Yemeni and 1 Tunisian to Slovakia, and 1 Saudi; December 2014 — 4 Syrians, a Palestinian and a Tunisian to Uruguay; 4 Afghans; 2 Tunisians and 3 Yemenis to Kazakhstan; January 2015 — 4 Yemenis to Oman, 1 Yemeni to Estonia; June 2015 — 6 Yemenis to Oman; September 2015 — 1 Moroccan and 1 Saudi; October 2015 — 1 Mauritanian and 1 British resident (Shaker Aamer); November 2015 — 5 Yemenis to the United Arab Emirates; January 2016 — 2 Yemenis to Ghana; 1 Kuwaiti (Fayiz al-Kandari) and 1 Saudi; 10 Yemenis to Oman; 1 Egyptian to Bosnia and 1 Yemeni to Montenegro; April 2016 — 2 Libyans to Senegal; 9 Yemenis to Saudi Arabia; June 2016 — 1 Yemeni to Montenegro.

August 15, 2016

The Last Prisoner to Arrive at Guantánamo, an Afghan Fascinated with US Culture, Asks Review Board to Approve His Release

On August 4, Muhammad Rahim, an Afghan, became the 56th Guantánamo prisoner to face a Periodic Review Board. The PRBs were set up in 2013, and are reviewing the cases of all the prisoners still held who are not facing trials (just ten of the remaining 76 prisoners) or who were not already approved for release by the high-level, inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force that President Obama established shortly after taking office in January 2009.

On August 4, Muhammad Rahim, an Afghan, became the 56th Guantánamo prisoner to face a Periodic Review Board. The PRBs were set up in 2013, and are reviewing the cases of all the prisoners still held who are not facing trials (just ten of the remaining 76 prisoners) or who were not already approved for release by the high-level, inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force that President Obama established shortly after taking office in January 2009.

33 men have so far been approved for release via the PRBs (and eleven have been released), while 17 have had their ongoing imprisonment held. This is a 67% success rate for the prisoners, and it ought to be embarrassing for the Obama administration, whose task force had concluded that they were “too dangerous to release” or that they should be prosecuted. See my definitive Periodic Review Board list on the Close Guantánamo website for further information.

Muhammad Rahim, who was born in November or December 1965, was the last prisoner to arrive at Guantánamo, in March 2008, when he was described as “a close associate” of Osama bin Laden. He has been described as a “high-value detainee” — one of only 16 held at the prison — but if this was the case he would surely have been put forward for prosecution, suggesting that, as with so many of the prisoners held at Guantánamo, his significance has been exaggerated.

Little was subsequently heard of Rahim, but at the end of 2012 his attorney, Carlos Warner, a federal public defender for the Northern District of Ohio, released letters that showed a different side to his client than the associate of bin Laden described by the US authorities. In one letter, Rahim wrote, “I like this new song Gangnam Style. I want to do the dance for you but cannot because of my shackles.”

In other letters, he “asked Warner to appeal for help from radio personality Howard Stern,” as the Associated Press described it. “If he is the ‘King of All Media’ he can help me,” Rahim wrote. In another, “he criticize[d] Fox News’ ‘Fair and Balanced’ slogan, writing that if that were true the channel ‘would not have to say it every five minutes.’”

The AP also spoke to one of Rahim’s brothers, Abdul Basit, an asylum seeker in London, who told them that, having left Afghanistan during the Soviet occupation, his brother “eventually got a job working for an Afghan government committee responsible for eradicating opium poppies, but that he was forced from the job by members of the Taliban.”

Basit, the AP revealed, was also detained by the US military — but in Afghanistan, for five years. He said that his brother “is a well-educated man who was not particularly interested in global politics,” and suggested that he was being “held more for who he might know rather than what he has done.” In broken English, he said, “There is no reason to put him in Guantánamo for this long time.”

In September 2015, Muhammad Rahim was in the news again. For Al-Jazeera, Jennifer Fenton wrote an article entitled, “‘Detained but ready to mingle’: Gitmo’s lonely heart on Tinder and Trump,” in which he wrote, “Donald Trump is an idiot!!! Sen. McCain is a war hero. Trump is a war zero,” adding, “How can a racist run for president? At this rate, Hillary [Clinton] has a chance.”

When he heard that millions of passwords had been stolen from the infidelity dating website Ashley Madison, he joked, “This is terrible news about Ashley Madison please remove my profile immediately!!! I’ll stick with Match.com … There is no way I can get Tinder in here.” Rahim doesn’t have any dating accounts, of course, but Warner described him as “detained but ready to mingle.”

Warner also described his client as a “funny guy” with “many ideas on a wide range of issues,” as Al-Jazeera described it. He added that the letters “give insight into the type of person Rahim is and should cause people to ‘look at his case and ask why is he being held.’”

Rahim is not only a joker. In another letter he wrote, “I am not high value. They call me high value because the CIA tortured me. How do we undo this injustice. Give me a trial. Let me be free.” He has never been charged, which suggests, as I mentioned above, that the US authorities do not have much of a case against him, and there are no records of him having undergone a Combatant Status Review Tribunal, which is required if prisoners are to face trials by military commission. A military lawyer was initially appointed to his case, but subsequently retired and was not replaced. In a letter, Rahim requested a military lawyer, asking, “I thought the military commissions wanted justice? How can I get justice without a military lawyer?”

He is also mentioned in the Senate Intelligence Committee’s report on the CIA’s torture program, for which the executive summary was made publicly available in December 2014. According to the report, “During sleep deprivation sessions, Rahim was usually shackled in a standing position, wearing a diaper and a pair of shorts … Rahim’s diet was almost entirely limited to water and liquid Ensure meal.” He was also subjected to sleep deprivation. Nevertheless, as the report also states, “the CIA’s detention and interrogation of Mohammad Rahim resulted in no disseminated intelligence report.”

Reflecting on his torture, he wrote in another letter, “How do I get out of here? I am innocent and I was tortured. Hung from the ceiling until I was dead.” He said that “animals were treated better” and “doctors and psychiatrist got rich off my blood,” although he also wrote, as Jenifer Fenton put it, that “he prays for them now.”

Rahim was alos mentioned in a detailed Rolling Stone article about Guantánamo at the end of 2015, in which the author, Janet Reitman, who spoke to Carlos Warner and to Rahim’s brother Abdul Basit about his case, noted:

The government issued a press release about Rahim, allegedly detailing his enemy activity, but it appears to be about another person entirely. This account, which Warner views as an example of the government’s general confusion, describes a low-level Al Qaeda operative, not, as was alleged about Rahim, a close associate of Osama bin Laden with “ties to Al Qaeda … throughout the Middle East.” A subsequent government report, filed in federal court in response to Warner’s habeas corpus petition seeking Rahim’s release, portrays him as a member of bin Laden’s inner circle, information based mostly on the word of two fellow Gitmo prisoners, and an informant who may have been subjected to torture.

Warner says that there is no indication that Rahim was an associate of bin Laden’s. Rahim did fight in Afghanistan, notes his brother, Basit, who I interview via Skype from his home in London, but it was during the war against the Soviets. Indeed, he and Warner note, Rahim worked for a time with the CIA. “The irony is, the ISI [Pakistani intelligence] picked him up, and the first thing he said was he wanted to talk with the CIA,” says Warner. “He trusted them because he’d worked with them, and he thought they’d help him.”

Nevertheless, in their unclassified summary for Rahim’s PRB, the US authorities maintained their claims about his significance, describing him as “one of a small number of Afghans to become trusted members of al-Qa’ida,” and adding, “He served as a translator, courier, facilitator, and operative for the group’s senior leadership, including Usama Bin Ladin [sic]. His proficiency in several languages, including Arabic, made him invaluable for communicating with foreign fighters and local populations in Afghanistan and Pakistan, as well as facilitating the movement of al-Qa’ida leaders and rank and file between the two countries, particularly after the start of Operation Enduring Freedom.”

It was also claimed that he “had advance knowledge of many of al-Qa’ida’s major attacks, including advanced knowledge of 9/11,” although I find that unlikely, and, it was also claimed, he “progressed to paying for, planning, and participating in attacks in Afghanistan against US and Coalition targets by al-Qa’ida, the Taliban, and other anti-Coalition militant groups.” The summary also notes that he “has admitted to working as a translator for al-Qa’ida,” but “claims to have done so only for the money,” which , if accurate, rather plays down much of the above.

Turning to Guantánamo, the authorities noted that he “has been generally compliant with the guard staff” since his arrival at the prison in March 2008, “and has been highly compliant since August 2015, according to Joint Task Force Guantánamo.” The summary also noted that, although he “has committed relatively few disciplinary infractions compared to the general population at Guantánamo, he has remained mostly uncooperative and defiant,” adding, “He crosses the line into noncompliance when he thinks he is being disrespected, mistreated, or perceived as being weak.”

The summary also claimed that Rahim “views his time in detention as a continuation of jihad,” adding, “He claims the guard staff and the detainees’ lawyers are enemies, and has reprimanded fellow detainees for showing the slightest courtesy toward them. He has sought to intimidate and taunt his captors even if it means never being released and dying as a martyr, which he appears to welcome.” This, of course, is an analysis that makes no sense when compared with the letters made publicly available by Carlos Warner, and Warner’s own appraisal of his client, and I cannot see how the description in the summary can stand up against this alternative view.

The juxtaposition between the man revealed in the letters and the US authorities’ view continues in the assessment of him as “a hardened al-Qa’ida member and devoted Bin Ladin follower when he arrived at Guantanamo,” who “has become even more deeply committed to the group’s jihadist doctrine and Islamic extremism in general since that time.” The summary added, “He continues to view the US and the West as enemies, has expressed support for and praised attacks by other terrorist groups, and has said he intends to return to jihad and kill Americans.”

In conclusion, the summary’s authors “assess that given his language proficiency, al-Qa’ida bona fides, and extensive extremist connections established before his capture, [Rahim] has multiple conduits for reengaging should he be released,” adding that “one of his brothers in particular, Abd Basit Zahdran, could also provide him a path to reengage.”

In the publicly available documents for the PRB, nothing was made available by Carlos Warner, and nothing is known, as yet, of what Rahim himself said, although Courthouse News reported that “Walter Ruiz, one of the defense attorneys for suspected 9/11 plotter Mustafa al-Hawsawi, appeared at the table with Rahim during the hearing but did not offer an unclassified statement.”

However, in their opening statement, Rahim’s personal representatives (military personnel appointed to help prisoners prepare for their PRBs) also painted a portrait at odds with the military’s analysis, noting that he has shown regret for his past actions, which, he reiterates, he did only for the money, and hoping only for a peaceful life, and to be reunited with his two wives and his seven children. The opening statement is posted below.

Periodic Review Board Initial Hearing, 4 Aug 2016

Muhammad Rahim, ISN 10029

Personal Representative Opening Statement

Good morning, ladies and gentlemen of the Board. We are the Personal Representatives for ISN 10029, Mr. Muhammad Rahim.

Rahim has attended all scheduled meetings. During the meetings he has been respectful and eager to participate in the PRB. He has also shown regret for his past actions, saying he only did what he did for money, so he could feed his family.

Rahim has two wives and seven children. He eagerly wants to be reunited with his family. He believes he needs to be present to help guide his children on a peaceful path. He worries that without him there to guide them, they could be taken advantage of.

Rahim has spoken of wanting a peaceful life in the future.

Rahim has stated in our meetings that he has never had any ill will towards the US and this will continue in the future. We stand ready to answer any questions you have.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album ‘Love and War’ and EP ‘Fighting Injustice’ are available here to download or on CD via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album ‘Love and War’ and EP ‘Fighting Injustice’ are available here to download or on CD via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

August 9, 2016

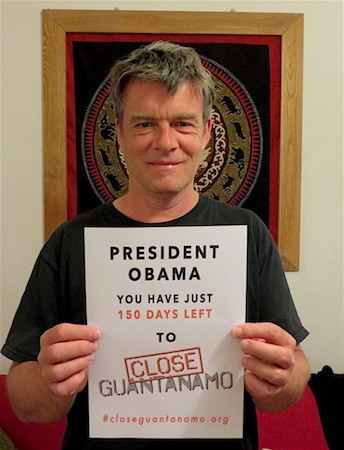

For Aug. 22, Please Send Us Your Photos Reminding President Obama That He Has Just 150 Days Left to Close Guantánamo

I wrote the following article for the “Close Guantánamo” website, which I established in January 2012, on the 10th anniversary of the opening of Guantánamo, with the US attorney Tom Wilner. Please join us — just an email address is required to be counted amongst those opposed to the ongoing existence of Guantánamo, and to receive updates of our activities by email.

I wrote the following article for the “Close Guantánamo” website, which I established in January 2012, on the 10th anniversary of the opening of Guantánamo, with the US attorney Tom Wilner. Please join us — just an email address is required to be counted amongst those opposed to the ongoing existence of Guantánamo, and to receive updates of our activities by email.

Dear friends and supporters,

Thanks to everyone who has supported the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative that we launched in January, when our co-founder Andy Worthington appeared on Democracy Now! with the music legend Roger Waters.

The Countdown began on Jan. 20 with supporters taking photos of themselves with posters reminding President Obama that he had just one year left to close Guantánamo, and has been followed by posters counting down every 50 days — 350 days on Feb. 3, 300 days on Mar. 25, 250 days on May 14, and 200 days on Jul. 3. Over 400 photos have been submitted to date, which can be found here, here and here.

The next significant date is Aug. 22, when President Obama will have just 150 days left to fulfill the promise he made on his second day in office back in January 2009, and we’re hoping that you’ll be able to join us in seeking to keep Guantánamo on the radar as the presidential race threatens to drown it out.

Please print off a poster , take a photo with it and send it to us.

We will be publicizing the Countdown reaching the 150-day mark, and also posting your photos on the website and on social media (on Facebook and Twitter). Please also feel free to include a message to President Obama, and, if you wish, let us know where you are, so we can show the geographical breadth of support for closing Guantánamo.

We maintain that the existence of the prison at Guantánamo Bay is as much of an affront to U.S. values now as it was when it opened in January 2002, because no country that claims to respect the rule of law should be holding people indefinitely without charge or trial. Soldiers should be held according to the Geneva Conventions until the end of hostilities — and not in a phony “global war” that seems to have no end — and terrorists should be charged and tried in federal courts. Every day that Guantánamo remains open is a source of shame for all decent Americans.

Because of pressure — from a variety of sources, including campaigners — President Obama has renewed his efforts to close Guantánamo in the last three years, releasing many dozens of prisoners, after a long period in which he did very little, after Congress raised obstacles, and he was unwilling to spend political capital bypassing lawmakers, even though he had the means to do so.

Just 76 men are left at Guantánamo, and 34 of those men have been approved for release — 13 by the high-level, inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force that President Obama established when he first took office in 2009 (the last 13 of the 156 men the task force recommended for release), and 21 others by Periodic Review Boards, another high-level process, involving representatives of the Departments of State, Defense, Justice and Homeland Security, as well as the office of the Director of National Intelligence and the Office of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, that began its deliberations in 2013.

32 men in total have been approved for release by the PRBs, and eleven of dos even have been freed. 16 others have had their ongoing imprisonment held, although their cases will continue to be reviewed every year. 16 others are awaiting reviews, or the results of reviews that have already taken place, and it is to be expected that a handful of them at least will also be approved for release, raising the prospect that, at the end of his presidency, President Obama may be holding no more than 40 men — ten facing trials, and around 30 whose ongoing imprisonment has been recommended by PRBs.

We believe that it is worthwhile trying to maintain the pressure on President Obama, even though we recognize that he may not be able to close Guantánamo before he leaves office, because of legislation passed by Congress preventing any Guantánamo prisoner from being brought to the U.S. mainland for any reason. Even if he were to pass an executive order, and could find his own funding, he would still need support from the state or states that would have to house the prisoners, and it is not clear that this support would be forthcoming, such is the extent of black propaganda about Guantánamo that is pumped out by the prison’s dangerous and unprincipled supporters.

While we still hope that President Obama can succeed, we are also prepared to carry on our campaigning into the next presidency, and we hope you will stay with us if that is the case. For now, however, let us do what we can to remind President Obama that we are still supportive of his aims.

If you want to do more than just send us a photo, you can write to your Senators and Representatives to ask them to drop their opposition to prisoners being brought to the US mainland. Find your Senators here and your Representatives here.

If you do contact them, you may want to let them know how ruinously expensive it is to keep Guantánamo open — at least $445 million a year, or $5.8 million a year per prisoner currently held — as well as how damaging it is for America’s reputation abroad and for its belief in itself as a country that respects the rule of law.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album ‘Love and War’ and EP ‘Fighting Injustice’ are available here to download or on CD via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album ‘Love and War’ and EP ‘Fighting Injustice’ are available here to download or on CD via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

August 5, 2016

Somali “High-Value Detainee,” Held in CIA Torture Prisons, Seeks Release from Guantánamo via Review Board

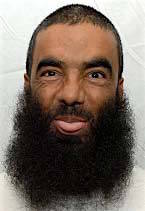

[image error]This week, Guleed Hassan Ahmed aka Gouled Hassan Dourad (ISN 10023), a Somali prisoner at Guantánamo — who arrived at the prison in September 2006, after being held in CIA “black sites” for two and a half years — became the 55th prisoner to face a Periodic Review Board. Set up in 2013, the PRBs are reviewing the cases of all the prisoners held at Guantánamo who are not facing trials (just ten of the remaining 76 prisoners) or who were not already approved for release by the high-level, inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force that President Obama established shortly after taking office in January 2009.

32 men have so far been approved for release via the PRBs (and eleven have been released), while 16 have had their ongoing imprisonment held, a 67% success rate for the prisoners, which rather demolishes the claims made by Obama’s task force that they were “too dangerous to release” or that they should be prosecuted.

Guleed Hassan Ahmed was born in April 1974, and is one of 16 “high-value detainees” who, as noted above, arrived at Guantánamo from CIA “black sites” in September 2006. He was seized in Djibouti in March 2004, by Somalis working with the CIA, but little is known of his whereabouts for the next two and a half years until his arrival at Guantánamo, or, indeed, why he ended up at Guantánamo at all. I always wondered if someone in the Bush administration wanted to have someone connected to events in Somalia at Guantánamo, simply to see if new connections could be made.

Allegedly the head of a Mogadishu-based organization, al-Itihaad al-Islamiya (AIAI), which, it is claimed, supported al-Qaeda members in Somalia, Ahmed had a Combatant Status Review Tribunal under George W. Bush in April 2007, but it reveals little about him before he returned to the silence that enshrouds all the “high-value detainees” unless they are charged and get to engage in pre-trial hearings. Ahmed, however, has not been charged, and was not even recommended for prosecution by Obama’s task force in 2009, suggesting that the government does not really have much of a case against him.

After nine years of US-imposed silence, he emerged briefly on June 2 as a witness in pre-trial hearings for Ramzi bin al-Shibh, one of five “high-value detainees” accused of planing an being involved in the 9/11 attacks. As Reuters described it, he “took the witness stand” to “back up claims” by bin al-Shibh, “who said guards at the U.S. prison used noises and vibrations to torment him.” In February, bin al-Shibh testified that “electronic devices hidden inside his cell were used to produce tremors and banging noises, disrupting his sleep for years.” Prosecutors, as Reuters explained, “responded by questioning his mental state.”

According to Reuters, Ahmed told the court, “Shibh told me that he’s got a problem … and I have the same problem that he’s got. They have mental torturing in the Camp Seven,” where the “high-value detainees” are held. “Speaking in broken English,” as Reuters put it, Ahmed “described vibrations in his cell floor, a constant ‘stinky smell’ and noises that sounded ‘like someone on the roof … hitting hammer.’”

When the prosecutor, Edward Ryan, “accused Ahmed of lying and questioned him on his disciplinary record at the prison,” asking, “Do you remember the time you spit out a food tray slot at a guard?” Ahmed replied by saying, “Yes, I did,” adding, “If you were there in the camp, you would do the same.”

In their unclassified summary for the PRB, the US authorities continued to describe Ahmed as significant, with no clue given as to why, if that was the case, he would not be facing a trial. It was noted that, in 1995, he “traveled from Sweden to Afghanistan to receive training, probably from al-Qa’ida, that he could use for jihadist purposes in his native Somalia,” a rather misleading claim, as Osama bin Laden was still in Sudan at the time, and a rather weak one, as revealed by the use of the word “probably.”

It was then noted that he “went to Somalia in 1997, joined the radical Muslim group Al-Ittihad al-Islami (AIAI), fought against the Ethiopian military and provided training to AIAl members,” although as Courthouse News reported, according to the Mapping Militants Project by Stanford University, “AIAI was initially nonviolent but later took up arms against Somali dictator Siad Barre — which drew wide national support — and later launched attacks in Ethiopia against mostly soldiers in an effort to control part of the country.” Their article added, “The US says Ahmed participated in the attacks against the Ethiopian military and trained other group members. However, the Stanford project says the group announced its transition from militancy to politics in January 1997, the same year the US says Ahmed worked with the group.”

Subsequently, however, according to the US authorities, Ahmed “served as a key member of al-Qa’ida in East Africa’s (AQEA) network in Somalia,” who “provided logistical and operational support to AQEA leaders, including almost certainly casing Camp Lemonier in Djibouti, the target of an AQEA plot.”

The authorities also noted that, “[d]espite initially admitting to his al-Qa’ida associations and providing a great deal of information about his support to AQEA, [Ahmed] over the course of his detention has sought to downplay his connection to the group.” They added that he “almost certainly remains a committed extremist and retains a worldview aligned with al-Qa’ida’s global jihadist ideology,” explaining that, “although he generally has been compliant with guard staff” at Guantánamo, “he has expressed hatred toward the West and support for violent extremism,” although the examples given do not necessarily back this up.

It was noted that, during interviews, he “has maintained to US officials that the only jihad he supports is the regional conflict in East Africa,” a point reiterated in an observation that he says that “he only supports regional insurgent efforts.” This, however, was described as an example of how he “has consistently attempted to deceive US officials,” even though it might just indicate that his only concerns are with the regional conflict in Somalia, and not anything else.

In conclusion, the US authorities claimed that it was “unclear” whether Ahmed “has become more radical during his time in detention — having possibly been influenced by more senior detainees — or if he always possessed anti-Western views and over time has become less hesitant to express them.” The authorities added the he “has expressed interest in reengaging in extremism if released,” and also stated that “[h]e does not appear to have direct contact with extremists outside Guantánamo, but some of his closest associates prior to detention have emerged as leaders in al-Shabaab, which almost certainly would provide avenues for [his] reengagement.”

In contrast, his personal representatives (military officials appointed to help prisoners prepare for their PRBs) painted a picture of someone who “wants nothing to do with extremism anymore and does not consider himself to be a threat to anyone,” who “harbors no enduring ill will to the US,” and who, moreover, wants only to be reunited with his wife and his four children, who live in Kenya — all positive comments for prisoners to make who are seeking to persuade US officials, in a process that is most closely akin to a parole board, that they are no threat, bear no ill-will towards the US, and have constructive and peaceful plans for life after Guantánamo.

The personal representatives’ opening statement is posted below. Courthouse News reported that Ahmed appeared before the PRB “in a long-sleeve, white tunic and looked intently engaged during the 20-minute hearing … viewed from the Pentagon in a closed-circuit feed,” and also noted that he “appeared without an attorney” at his PRB, and “had no legal representation.”

Periodic Review Board Initial Hearing, 02 Aug 2016

Guleed Hassan Ahmed, ISN 10023

Personal Representative Opening Statement

Good morning, ladies and gentlemen of the Board. We are the Personal Representatives for ISN 10023, Mr. Guleed Hassan Ahmed. He has met with us on multiple occasions over the past month and has never missed a meeting. From the start he has been cooperative and enthusiastic about his PRB.

Guleed has family in both Canada and in the US. All are ready and willing to support Guleed upon his transfer. He is especially looking forward to reuniting with his wife and four children who live in Kenya.

As an HVD he has not had access to as many classes and programs as the other detainees. He has however tried to participate in anything that was offered. Guleed likes to watch National Geographic movies, Blue Planet documentaries, and anything about science or nature. He likes to read religious books, Harry Potter books, the Economist and Newsweek.

Guleed would like the chance to leave detention at GTMO and start a new simple and peaceful life. He has had experience in Computer Engineering and small business in the past that could be useful in setting up a new life.

In our meetings with Guleed, he has stated to us that he harbors no enduring ill will to the US. Additionally, he has stated he wants nothing to do with extremism anymore and does not consider himself to be a threat to anyone. He wants only to live a peaceful life with his wife and children.

Thank you for your time and attention. We stand ready to answer any questions you have.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album ‘Love and War’ and EP ‘Fighting Injustice’ are available here to download or on CD via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album ‘Love and War’ and EP ‘Fighting Injustice’ are available here to download or on CD via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

August 4, 2016

Two Yemenis Approved for Release from Guantánamo, as Detention of Two Saudis Upheld, Including Torture Victim Mohammed Al-Qahtani

With just 168 days left for President Obama to close the prison at Guantánamo Bay, as he promised when he first took office in January 2009, the reassuring news is that there are now just 76 men held, and 34 of those men have been approved for release. 13 of those 34 were approved for release in Obama’s first year in office, by an inter-agency task force he established to review the cases of all the prisoners held at the start of his presidency, while 21 others have been approved for release since January 2014 by Periodic Review Boards. See my definitive Periodic Review Board list here on the Close Guantánamo website.

With just 168 days left for President Obama to close the prison at Guantánamo Bay, as he promised when he first took office in January 2009, the reassuring news is that there are now just 76 men held, and 34 of those men have been approved for release. 13 of those 34 were approved for release in Obama’s first year in office, by an inter-agency task force he established to review the cases of all the prisoners held at the start of his presidency, while 21 others have been approved for release since January 2014 by Periodic Review Boards. See my definitive Periodic Review Board list here on the Close Guantánamo website.

The PRBs, another inter-agency process, but this time similar to parole boards, have been reviewing the cases of all the men who are not facing trials and who had not already been approved for release, and, to date, 56 reviews have taken place, with 32 men being approved for release (and eleven of those already freed), and 16 approved for ongoing imprisonment, while eight decisions have yet to be taken. This is a 67% success rate for the prisoners, and ought to be a source of shame for the Obama administration’s task force, which described these men as “too dangerous to release” or recommended them for prosecution back in 2009.

In the cases of those described as “too dangerous to release,” the task force acknowledged that insufficient evidence existed to put them on trial, but clearly failed to recognise that their recommendations were based on extreme, and, it turns out, unjustifiable caution. In the cases of those recommended for trials, embarrassingly, the basis for prosecution collapsed in 2012-13 when appeals court judges struck down some of the only convictions secured in the troubled military commission trial system on the basis that the war crimes for which the men had been convicted were not internationally recognized, and had been invented by Congress.

Four of these decisions in the Periodic Review Boards were announced in the last week and a half, after the most recent decisions I reported — to approve for release Ravil Mingazov, the last Russian in Guantánamo, and to approve for ongoing imprisonment Haroon Gul, known to the authorities as Haroon al-Afghani, who is one of the last prisoners to arrive at Guantánamo, in 2007.

Of the four, two men, both Yemenis — Musa’ab al-Madhwani (ISN 839) and Hail Aziz Ahmed al-Maythali (ISN 840) — were recommended for release. Both men were seized in Karachi, Pakistan on September 11, 2002, the first anniversary of the 9/11 attacks, and, as the US government acknowledged, were mistakenly described as members of an Al-Qaeda cell.

The first to be approved for release, Musa’ab al-Madhwani, had his case reviewed on June 28, 2016, and the decision was taken on July 28, 2016. The decision to release him was unsurprising, and it is only a shame that it has taken so long. In December 2009, a judge reluctantly turned down his habeas corpus petition, because of the narrowness of the requirements for turning down habeas requests, and as I explained at the time of al-Madhwani’s PRB, District Judge Thomas F. Hogan “did not think Madhwani was dangerous,” noted that he had been a “model prisoner” since his arrival at Guantánamo in October 2002, and explained, “There is nothing in the record now that he poses any greater threat than those detainees who have already been released.”

In its final determination, the board members, “by consensus, determined that continued law of war detention of the detainee is no longer necessary to protect against a continuing significant threat to the security of the United States.”

The members also provided a rundown of how al-Madhwani had addressed all of their concerns. They described how they had considered that his “degree of involvement and significance in extremist activities has been reassessed to be that of a low-level fighter,” and also noted that he “has taken advantage of educational opportunities while at Guantánamo,” as well as describing his “lack of expression of support for extremist ideologies [or] anti-American sentiment,” his “lack of ongoing extremist ties,” and his “strong familial support network,” plus the fact that he “has been highly compliant throughout detention.”

Al-Madhwani will now be held until a third country is found that will offer him a new home, as the entire US establishment agrees that no Yemenis can be repatriated from Guantánamo because of fears about the security situation in Yemen.

On August 1, another of the “Karachi Six,” Hail Aziz Ahmed al-Maythali (aka Hayil al-Maythali), was also approved for release. His PRB took place on June 30, 2016, and, as I explained at the time, his lawyer, Jennifer Cowan, particularly explained how her client’s initial anger about his imprisonment had been replaced by a maturity and self-awareness that was obviously recognized by the board. As she stated, “he has grown substantially as a person. He recognizes that he made bad decisions in the past and he has no interest in repeating these mistakes. Hayil realizes that it was a mistake to go someplace else and fight for a cause that was not his. He does not blame America for his current situation, he blames himself for his actions.”

On August 1, another of the “Karachi Six,” Hail Aziz Ahmed al-Maythali (aka Hayil al-Maythali), was also approved for release. His PRB took place on June 30, 2016, and, as I explained at the time, his lawyer, Jennifer Cowan, particularly explained how her client’s initial anger about his imprisonment had been replaced by a maturity and self-awareness that was obviously recognized by the board. As she stated, “he has grown substantially as a person. He recognizes that he made bad decisions in the past and he has no interest in repeating these mistakes. Hayil realizes that it was a mistake to go someplace else and fight for a cause that was not his. He does not blame America for his current situation, he blames himself for his actions.”

In their final determination, the board members, having, as with all the men approved for release, determined, by consensus “that continued law of war detention … is no longer necessary to protect against a continuing significant threat to the security of the United States,” focused in particular on how his “degree of Involvement and significance in extremist activities has been reassessed to be that of a low-level fighter,” and how, although he “admitted to fighting with the Taliban, he explained his rationale for doing so and articulated his regret.”

The board members also “noted the availability of familial and financial resources and structures within the region,” as well as al-Maythali’s “progression over the past few years to be more open to other cultures.” Finally, the members noted that he “has no known close associations with terrorists outside of Guantánamo.”

Unlike al-Madhwani, who was recommended for resettlement in any country, the board members, in al-Maythali’s case, recommended “transfer only to an Arabic-speaking country, preferably a GCC [Gulf Cooperation Council] country”; in other words, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Bahrain or Oman.

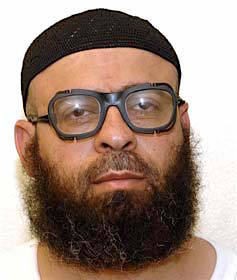

Of the two men whose ongoing imprisonment was recommended, the first was Mohammed al-Qahtani (ISN 063), a Saudi prisoner and an alleged 20th hijacker for the 9/11 attacks, who was subjected to a specific torture program in Guantánamo, the first that has ever been acknowledged publicly by a senior Pentagon official.

Al-Qahtani’s case was reviewed on May 16, 2016, as I discussed here, and the decision was taken on July 18, 2016, with the board members being unswayed by al-Qahtani’s lawyers’ explanations of his severe mental health issues predating his capture, despite the fact that, as they put it, Dr. Emily Keram, an expert witness who examined him, “concluded that Mr. al-Qahtani’s pre-existing mental illnesses likely impaired his capacity for independent and voluntary decision-making well before the United States took him into custody, and left him ‘profoundly susceptible to manipulation by others.’” As the lawyers added, “These findings call into serious question the extent to which it would be fair to hold Mr. al-Qahtani responsible for any alleged actions during that period of his life. They also cast doubt on any claims that Mr. al-Qahtani would have been entrusted with sensitive information about secret plots.”

Al-Qahtani’s case was reviewed on May 16, 2016, as I discussed here, and the decision was taken on July 18, 2016, with the board members being unswayed by al-Qahtani’s lawyers’ explanations of his severe mental health issues predating his capture, despite the fact that, as they put it, Dr. Emily Keram, an expert witness who examined him, “concluded that Mr. al-Qahtani’s pre-existing mental illnesses likely impaired his capacity for independent and voluntary decision-making well before the United States took him into custody, and left him ‘profoundly susceptible to manipulation by others.’” As the lawyers added, “These findings call into serious question the extent to which it would be fair to hold Mr. al-Qahtani responsible for any alleged actions during that period of his life. They also cast doubt on any claims that Mr. al-Qahtani would have been entrusted with sensitive information about secret plots.”

In their final determination, however, the board members, having determined, by consensus, that “continued law of war detention of the detainee remains necessary to protect against a continuing significant threat to the security of the United States,” pointed out that they had “considered [his] past involvement in terrorist activities, to include almost certainly having been selected by senior al-Qa’ida members to be the 20th hijacker for the 9/11 attacks and, after failing in that effort, returning to Afghanistan and fighting on the front lines against the Northern Alliance.”

The board members also “noted its inability to assess [his] current mindset and credibility due to this refusal to respond to questions regarding his reasons for traveling to Afghanistan and ensuing activities,” adding, “The lack of information prevented the Board from understanding how and to what extent his psychiatric condition contributed to his decisions during that time.”

In conclusion, the board members sounded a note of cautious optimism for those seeking al-Qahtani’s release, stating that they recognize “the benefits of the Mohammed bin Naif rehabilitation program” in Saudi Arabia, which has treated numerous returning Guantánamo prisoners, and others who have engaged in militancy and terrorism. They added that they also recognized “the available family support,” and encouraged “officials of the Mohammed bin Naif Counseling and Care Center to work with the detainee to begin treatment for his mental health diagnoses while at Guantanamo.”

They also welcomed “additional information from the Saudi government for consideration in future reviews,” commended al-Qahtani “for his recognition of his mental health diagnoses,” and stated that they looked forward to reviewing his file in six months, as with all prisoners whose ongoing imprisonment is recommended, as well as encouraging him “to be more forthcoming with the Board in future reviews and to cooperate with mental health officials.”

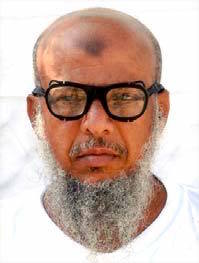

The final decision — another decision to recommend ongoing imprisonment — was for Ghassan al-Sharbi (ISN 682), described as Abdullah al-Sharbi, another Saudi whose case was reviewed on June 23, 2016, as I discussed here. The decision was taken on July 25.

Al-Sharbi doomed his chances of being recommended for release by refusing even to meet with his personal representative, a military official appointed to help prisoners with their reviews. Seized with the alleged ”high-value detainee” Abu Zubaydah and accused of being a bomb-maker, he has been persistently uncooperative at Guantanamo, even though, many years ago, I met his then-military defense lawyer and his sister, who both described a man at odds with the US military’s assessment of him.

Nevertheless, in their final determination, having determined, by consensus, that “continued law of war detention … remains necessary to protect against a continuing significant threat to the security of the United States,” the board members “considered [his] past involvement in terrorist activity to include selection by senior al-Qa’ida leaders to receive training on the manufacture of remote controlled improvised explosive devices and his attending meetings with senior al-Qa’ida leaders where they may have discussed attacks against the United States,” adding that they “also noted [his] mostly non-compliant and hostile behavior while in detention, including organizing confrontations between other detainees and the guard force.” Finally, they “considered [his] prior statements expressing support for attacking the United States, and [his] refusal to discuss his plans for the future.”

They did, however, state that they appreciated his “candor at the hearing” — which was the first mention of how he had behaved — and encouraged him “to engage with his Personal Representative for future reviews and answer questions in any future hearings.”

Note: Of the nine decisions not yet taken, most relate to the most recent reviews, although three are overdue, as decisions are generally expected within one to two months — for Said Salih Said Nashir (ISN 841), the last of the “Karachi Six,” whose case was reviewed on April 21, for Jabran al Qahtani (ISN 696), reviewed on May 19, and for Sufyian Barhoumi (ISN 694), reviewed on May 26. The latter two were seized with Ghassan al-Sharbi, Abu Zubaydah and others.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album ‘Love and War’ and EP ‘Fighting Injustice’ are available here to download or on CD via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).