Andy Worthington's Blog, page 76

April 21, 2016

Guantánamo Review for Obaidullah, an Afghan Whose Lawyers Established His Innocence Five Years Ago

I wrote the following article for the “Close Guantánamo” website, which I established in January 2012, on the 10th anniversary of the opening of Guantánamo, with the US attorney Tom Wilner. Please join us — just an email address is required to be counted amongst those opposed to the ongoing existence of Guantánamo, and to receive updates of our activities by email.

I wrote the following article for the “Close Guantánamo” website, which I established in January 2012, on the 10th anniversary of the opening of Guantánamo, with the US attorney Tom Wilner. Please join us — just an email address is required to be counted amongst those opposed to the ongoing existence of Guantánamo, and to receive updates of our activities by email.

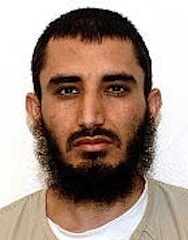

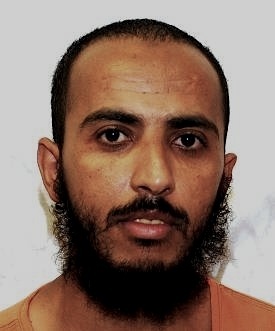

On Tuesday (April 19), Obaidullah (ISN 762), an Afghan prisoner at Guantánamo, became the 30th prisoner to face a Periodic Review Board, a review process set up in 2013 to review the cases of all the prisoners not already approved for release (by the high-level, inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force that President Obama established shortly after taking office in 2009) or facing trials.

Just ten men are in this latter category, but, when the PRBs were established in 2013, 25 others recommended for prosecution by the task force were made eligible for the PRBs, after a number of appeals court rulings made prosecutions untenable, along with 46 others described by the task force as “too dangerous to release,” on the basis that there was insufficient evidence to put them on trial; in other words, that the information used to justify their imprisonment was not evidence at all, but, to a large extent, information obtained through the use of torture or other forms of abuse, or through the bribery of prisoners — who were given “comfort items” in exchange for their cooperation.

Of the 30 cases reviewed to date, 20 have resulted in recommendations that the men in question be released, seven men have had their ongoing imprisonment recommended, and three decisions have not yet been taken. That’s a success rate of 74%, but only nine of the 20 approved for release have been freed, and 35 others are still awaiting their reviews, even though, when the PRB process was first established, via an executive order in 2011, President Obama promised that they would be completed within a year.

Of the 27 decisions taken, only three have involved prisoners formerly recommended for prosecution, with one approved for release (and freed), and two others recommended for ongoing imprisonment. One of the two pending recommendations is also for a man formerly recommended for prosecution, and Obaidullah is also in this category, although it has never seemed plausible to me that he should ever have been put forward for prosecution.

As I explained in my article, “Guantánamo trials: another insignificant Afghan charged,” written after he was put forward for a trial by military commission under President Bush in September 2008:

[He] was charged with “conspiracy” and “providing material support to terrorism,” based on the thinnest set of allegations to date”: essentially, a single claim that, “[o]n or about 22 July 2002,” he “stored and concealed anti-tank mines, other explosive devices, and related equipment”; that he “concealed on his person a notebook describing how to wire and detonate explosive devices”; and that he “knew or intended” that his “material support and resources were to be used in preparation for and in carrying out a terrorist attack.”

Despite the thinness of the allegations, and despite the fact that Obaidullah maintained his innocence, he then had his habeas corpus petition turned down, in October 2010, when Judge Richard Leon of the District Court in Washington, D.C. concluded, as I described it at the time, that “his account was full of evasions and inconstancies.”

Nevertheless, his lawyers refused to give up, and in 2011 a military investigator, Navy Lt. Cmdr. Richard Pandis, visited Afghanistan, establishing a coherent narrative in which Obaidullah was innocent. To cite just one example unearthed during the investigation, the fact that dried blood was found in the back seat of his car — which the U.S. authorities attributed to him carrying wounded insurgents — actually came about because, “two nights before the raid, Mr. Obaidullah’s wife had given birth in the car while on the way to the hospital.” The defense team added that he “had not volunteered that explanation about the blood” because of “a cultural taboo about discussing childbirth.”

Moreover, even if he had been engaged in militarily opposing the US occupation, it is difficult to see why he was at Guantánamo. As Charlie Savage noted, reporting about Lt. Cmdr. Pandis’s investigation for the New York Times back in 2012, “It is an accident of timing that Mr. Obaidullah is at Guantánamo. One American official who was formerly involved in decisions about Afghanistan detainees said that such a ‘run of the mill’ suspect would not have been moved to Cuba had he been captured a few years later; he probably would have been turned over to the Afghan justice system, or released if village elders took responsibility for him.”

Last April, the Los Angeles Times revisited Obaidullah’s story, in an article entitled, “Family fears that Afghan prisoner at Guantánamo will be forgotten.” In it, Ali M. Latifi spoke to his lawyers, who said they had “exhausted all potential remedies” in court, after their investigation failed to re-open any doors.

His lawyers also explained that Obaidullah had “turned his energy to writing poetry inspired by his experiences, which include time as a refugee in a Pakistani camp during the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan, as a shopkeeper in Khowst under Taliban rule and as a prisoner at Guantánamo.”

In a 2011 poem, he wrote:

Singing nightingales are following the caravan

And with their childish and delicate tongues sing sweet melodies

They are disgusted with the murders and oppressions humankind commit

Obaidullah’s lawyers also explained how claims that he was an Al-Qaeda member were “far-fetched.” Maj. Derek A. Poteet, part of his defense team, said, “Anyone who knows anything about Al Qaeda knows they wouldn’t recruit a 19-year-old Afghan who lived at home. It’s an organization comprised primarily of Arabs.”

The lawyers also explained how, in 2013, Obaidullah “joined more than 160 detainees in a hunger strike, during which he lost 40 pounds in five months.” His brother, Fazel Karim, “said the strike helped draw worldwide attention to the treatment of Guantánamo detainees, who were banned from participating in communal prayers.” As Maj. Poteet put it, “He lost the right to practice his religion.”

Fazel Karim also explained how, as the Los Angeles Times described it, “Obaidullah’s mother — whose health has deteriorated during his detention — worries that her son may be forgotten.” As he said, “She is worried that her son will never return home and that those still in detention will just disappear.”

It was also noted that Obaidullah’s relatives “have appealed to Afghan officials, including former President Sibghatullah Mojadidi, but have repeatedly been told that the issue is a ‘US matter.'”

The Los Angeles Times also explained that Obaidullah’s daughter, Mariam, “has seen him only on a computer screen” after the authorities allowed the International Committee of the Red Cross to “set up periodic Skype meetings.” However, relatives said Mariam “longs for his physical presence.” As Fazel Karim put it, “She cries out in her dreams for her father.”

Nevertheless, the US authorities continue to cling to their assessment of Obaidullah. In the government’s Detainee Profile, it is claimed that he “received training in explosives from the Taliban and was part of an al-Qa’ida-associated improvised explosive device (IED) cell that targeted Coalition forces in Khowst, Afghanistan,” and that, “During the early days of Operation Enduring Freedom, [he] also may have provided logistics support to fighters aligned with al-Qa’ida.”

It was also stated that his IED cell “probably was led by Bostan Karim” (ISN 975), who is also facing a PRB, and had his habeas petition turned down in October 2011. According to the military, Obaidullah “had a close relationship” with him, and the cell was “under the ultimate control of al-Qa’ida senior paramilitary commander Abu Layth al-Libi.”

It was also claimed that, “[d]uring early interviews,” Obaidullah “admitted to working with Karim to acquire and plant anti-tank mines to target US and other Coalition Forces,” but those early interviews took place in Afghanistan, when he was being abused. It was also stated that Obaidullah “has provided no information of value since his initial interviews in late 2002 — especially after learning of Karim’s transfer to Guantánamo in March 2003.” He apparently “stated that he was very afraid of Karim and wanted an opportunity to resolve any issues between them surrounding Karim’s capture.”

It was also noted that he has been “mostly compliant” at Guantánamo, and “has committed less than 100 infractions since his arrival — a low number relative to other detainees — including infrequent hostility toward the guards and failure to follow rules or instructions.” However, for most of his time, he has been regarded as offering “evasive, implausible, and contradictory explanations to questions pertaining to terrorist activities.”

Crucially, for his PRB, it was also noted that, because he “has provided little information to interrogators,” the authorities “lack insight into his current mindset, which challenges both our understanding of what motivated his activities before detention and whether he would pursue extremist activity after detention.” It was noted that he “has not expressed any intent to re-engage in terrorist activities or espoused any anti-US sentiment that would indicate he views the US as his enemy,” and it was also stated that he “has indicated that he enjoys studying English and wants to be collocated with English speakers,” and that, in March 2015, he “stated that he reads English books to expand his vocabulary and Arabic books to improve his Arabic.” He has also said that “if he returned to Afghanistan, he would like to finish his education and then return to being a shopkeeper,” although the authorities sounded a note of caution because some former prisoners, described as members of his alleged IED cell, “have reengaged in extremist activity in Khowst, Afghanistan,” and “could provide him opportunities to reengage should he choose to do so.”

In response, his civilian lawyer, Anne Richardson, and his personal representatives (military personnel assigned to help him prepare for his PRB) delivered powerful descriptions of his suitability for release. His representatives noted his enthusiasm for the PRB and for learning, and discussed his supportive family in Afghanistan, and Anne Richardson expanded on these points, based on the seven years she has known him. With reference to his poetry, she noted that one of his translators, for poems submitted during the habeas process, “was the distinguished poet Abdul Bari Jahani, who is now the Minister of Culture and Education, [and] who is the most esteemed living poet in the Pashto language.” Mr. Jahani, she added, “has written a supporting letter regarding Obaidullah, urging this Board to recognize that he poses no threat.”

She also stressed how cooperative he has been, describing how he “is and has for many years been one of the most compliant detainees, ” who “served as Block leader [and] a translator for others who experienced conflict with the guards or other detainees.”

These statements are posted below, and I hope you have time to read them.

Periodic Review Board Hearing, 19 April 2016

Obaidullah, ISN 762

Personal Representative Opening Statement

Good morning ladies and gentlemen of the Board.

Good morning ladies and gentlemen of the Board.

We are the Personal Representatives of ISN 762. We will be assisting Mr. Obaidullah this morning with his case, aided by his Counsel, Mrs. Anne Richardson.

In the past four months, Obaidullah has earnestly participated in the Periodic Review Process and has attended all meetings with his Personal Representatives and his Counsel.

Obaidullah has conducted himself in a professional and patient manner throughout all engagements with Counsel and his representatives. He has a proven history of compliant behavior while detained at Guantánamo. He has engaged with the Joint Task Force Medical Staff in order to deal with health issues.

This teamwork has greatly improved his quality of life. He has taken advantage of all the opportunities for education and personal enrichment while detained at Guantánamo. These opportunities include courses in English, Life Skills, computers.

Obaidullah is fortunate to have a very supportive family remaining in Afghanistan comprised of his spouse, daughter, mother, brother and sister. His family members and the town elders have pledged unwavering financial support, a place of residence, and assistance with employment during his transition to the utmost of their ability.

Subsequently, Obaidullah will discuss both his past and his desire for a better life for himself in the future. We are confident that Obaidullah’s desire to pursue a better way of life if transferred from Guantánamo, is genuine and that he does not represent a continuing or significant threat to the security of the United States of America. He is open to transfer to any country, but would prefer to return to Afghanistan if possible.

Thank you for your time and attention. We are pleased to answer any questions you have throughout this proceeding.

Periodic Review Board Hearing, 19 April 2016

Obaidullah, ISN 762

Private Counsel Opening Statement

Good morning. My name is Anne Richardson, and I am the Private Counsel for Obaidullah. I have been an attorney for over 25 years, and now work at a non-profit called Public Counsel in Los Angeles. I appreciate this opportunity to appear before you and to give you my observations regarding Obaidullah.

I first met Obaidullah in 2009, when I began to represent him in his habeas petition, along with the Center for Constitutional Rights. Since then, I have been down to Guantánamo about a dozen times to meet with him. I also regularly have telephone calls to stay in touch with him and keep his spirits up. Since about 2010, his English has been so excellent that we have not needed a translator unless we are discussing complex legal issues.

Obaidullah does not pose any threat to the United States. He was only approximately 19 when he was captured, from his own bed, in the middle of the night. He has a wife and a daughter, who was born just before he was captured, whom he desperately longs to see. His father died when he was very young, and his mother, brother and sister still live in the same village. Obaidullah’s brother Fazel has a very successful mobile phone shop and has already built a new house for his own wife and children that he hopes to share with Obaidullah and his family. His family has written supportive letters, stating that they will do everything in their power to help him make an adjustment once he is released from Guantánamo. While he would like to be transferred back home, where he can immediately start working with his brother Fazel, and live with his extended family, he is willing to go wherever the United States transfers him.

In all the years I have visited and spoken with him, Obaidullah has never expressed any ideological ideas about America or any other country. He has been unfailingly polite and courteous in asking after my family and those of the other habeas attorneys. I did not know if he would have a problem meeting with female attorneys, but he has always shaken my hand, and seen me as a full peer of any male attorney he also meets with. Far from being a religious extremist, he discussed with us childhood games he remembered from Afghanistan, and has written some moving poems, some of which we have submitted to this Board. In fact, one of his translators during the habeas process was the distinguished poet Abdul Bari Jahani, who is now the Minister of Culture and Education, who is the most esteemed living poet in the Pashto language. Mr. Jahani has written a supporting letter regarding Obaidullah, urging this Board to recognize that he poses no threat.

Obaidullah is and has for many years been one of the most compliant detainees. He served as Block leader, and even before that, he served as a translator for others who experienced conflict with the guards or other detainees. He has taken English classes, computer classes, art classes, and takes every opportunity to improve himself and improve his life once he is released from Guantánamo.

Obaidullah is no longer young, and wishes nothing more than just to be back with his family. He proudly tells us how smart his daughter is, and how important her schooling is to him. Although he is willing to undergo any program the US wishes to require, he does not need any rehabilitation.

At one time, he was charged in the military commission’s process. The charges were later dismissed. We have submitted letters from a large number of his current and former military attorneys and investigators, as well as his habeas attorneys, all of whom express the same conclusion — that he is not a danger to the United States or its interests. We also stand ready to assist him in his reintegration into life outside the prison, whether financially or emotionally, so convinced are we that he will be able to adjust and lead a lawful, humble life on the outside.

In conclusion, I urge this Board to find that Obaidullah is not a threat to the United States, and I trust that any lingering doubts this Board may have will be assuaged by meeting him yourselves.

Very Truly Yours,

Anne Richardson

Note: Please check my definitive Periodic Review Board list for the latest news about forthcoming reviews.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ is available for download or on CD via Bandcamp — also see here). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ is available for download or on CD via Bandcamp — also see here). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

David Cameron, Zac Goldsmith and Andrew Neil Owe Suliman Gani An Apology for Calling Him “Repellent” and an IS Supporter

[image error]What a disgrace the Tories are. With Zac Goldsmith consistently trailing Sadiq Khan in the polls, prior to the election of London’s Mayor on May 5, campaign managers — including PR guru Lynton Crosby, who specialises only in the kind of black propaganda that has dragged politics into the gutter for the last six years — decided to play the race card, accusing Khan, a Muslim, of sharing platforms with Muslim extremists, and singling out, for particular attention, Suliman Gani, a teacher and broadcaster, and formerly the imam of Tooting Islamic Centre.

This was an odd choice, as anyone who knows Suliman Gani can confirm, because he is no extremist, but, rather, a community leader who tries to build bridges between communities, and a tireless advocate for human rights. I have known him for many years through my work on Guantánamo and the campaign to free Shaker Aamer, and have always found him to be thoroughly decent. Although he is socially conservative, and opposed to gay marriage, which is not a position I take, it is one that many Tories do, but I have no reason to suspect that he views women as “subservient,” as alleged, or, crucially, to believe that he is at all supportive of terrorism.

So it came as a real shock when, last Thursday, speaking of individuals Sadiq Khan has shared a platform with, Zac Goldsmith said, “To share a platform nine times with Suliman Gani, one of the most repellent figures in this country, you don’t do it by accident.”

Suliman Gani was shocked. Everyone who knew him was shocked. One might expect the violence-seeking provocateur Anjem Choudary to merit a description as “one of the most repellent figures in this country” by a white political candidate playing the race card, but not Suliman Gani.

And oh, the humiliation when Gani posted a photo of Zac Goldsmith standing with him, taken at an event last November encouraging Muslims to stand for election as Tory councillors, which was organised by Dan Watkins, the Conservative Parliamentary Spokesman for Tooting, who had stood against Sadiq Khan (and lost) at last year’s General Election. Gani has also appeared with other prominent Tories, including Jane Ellison, Tania Mathias, David Davis and Andrew Mitchell during human rights campaigns.

Goldsmith was also caught out trying to accuse Sadiq Khan of supporting Tooting resident Babar Ahmad, who was extradited to the US on terrorism charges (and is now back home in the UK). As Dave Hill described it in the Guardian:

He accused Khan of poor judgment by campaigning on Ahmad’s behalf and said he had “never heard of Ahmad until quite recently.” But within hours, video footage from 2012 emerged of Goldsmith telling anti-extradition campaigners that Ahmad’s case had “caught people’s imagination” and that he’d “been bombarded with letters” about it.

And then, on Monday, Andrew Neil stepped into the fray, nakedly showing political bias at a televised Mayoral debate by targeting Khan for sharing a platform with Gani, who, he said, supported IS, a claim that he fervently denies.

Gani immediately took legal advice, and as the media took an interest I liaised with him and LBC’s Theo Usherwood, and accompanied him to LBC’s studios for an interview at which he sought an apology from Zac Goldsmith, and, to amplify the Tories’ discomfort, revealed that he had actually backed the Tory candidate Dan Watkins against Sadiq Khan in the General Election last May and “even supplied canvassers for his campaign,” as the Guardian described it, reporting that he also “said he felt he had been used by the Conservatives ‘as a scapegoat to discredit Sadiq Khan.'” On April 14, Gani had also tweeted this photo of himself with Watkins.

In the interview, which aired yesterday, Gani also “said he spoke to Goldsmith, who by that time had become the Tory mayoral candidate, outside the meeting, shook his hand and requested a meeting with him to discuss giving further help.” According to Gani, “Goldsmith was very polite and said it was: ‘No problem, and I should send him an email.'”

Before the interview aired, however, David Cameron got involved, repeating the claim that Suliman Gani supported IS during Prime Minister’s Question Time, to boos from the Labour benches, I’m glad to note, and denunciations from senior figures in the Labour Party. A spokesperson for Jeremy Corbyn said, “I think it demeans the office of the Prime Minister to repeat some of those allegations. Sadiq has been very strong on issues around terrorism.” Shadow Justice Minister Andy Slaughter stated, “Cameron sinks into the gutter in a desperate bid to prop up his failing candidate. Demeans his office. Shame on him.”

In response to the attacks, Gani tweeted, “PM David Cameron accused me of being an extremist and that I support IS! He did so during PMQT in the commons and therefore cannot be sued.” In a second tweet, he wrote, “I hope the Prime Minister will reflect and retract his comments. This is defamation at its highest level.”

As Dave Hill noted for the Guardian, “Gani also told Usherwood that his alleged support for Islamic State was based on a misconstrued remark made by someone else at a meeting where the ‘historical context’ of IS’s emergence was discussed.”

[image error]He added that it was “not clear if the meeting in question” was the one advertised in the poster for a discussion in January, “The Evils of Isis,” which I’ve also posted here. As he noted, however, “The title of the Mitcham event [is] of interest in view of the prime minister’s Commons allegation about Gani.” Perhaps the best way of looking at the way the Tories have mischaracterised Gani’s views is to understand that, although he is in favour of the establishment of an Islamic State, he is appalled by the brutality of Daesh, whose violence he regards as un-Islamic.

As Hill also noted, “Gani said he had ‘never promoted terrorism or violence,’ and went on to say that he had fallen out with Khan over the MP’s support for same sex marriage.”

In response to the PMQ debacle, Sadiq Khan said, “The Tories are running a nasty, dog-whistling campaign that is designed to divide London’s communities. I’m disappointed that the Prime Minister has today joined in.”

That certainly seems to be true, and while I hope the Tories pay at the polls for their dirty campaigning, I do also think that Suliman Gani deserves an apology from David Cameron, Zac Goldsmith and Andrew Neil. The Muslim community, and those who know him, have rallied around him, but damage has been done to his reputation that is completely underserved, and he seems, above all, to be collateral damage to the Tories in a disgraceful effort to swing some old white racists their way in the last weeks of the Mayoral campaign. Ironically, however, they seem instead to have alienated considerably more Muslim voters, many of whom were planning to vote for Zac Goldsmith until they saw the Tories in their true colours.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ is available for download or on CD via Bandcamp — also see here). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ is available for download or on CD via Bandcamp — also see here). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

April 15, 2016

Saifullah Paracha, 68-Year Old Pakistani Businessman, Has His Ongoing Imprisonment at Guantánamo Approved

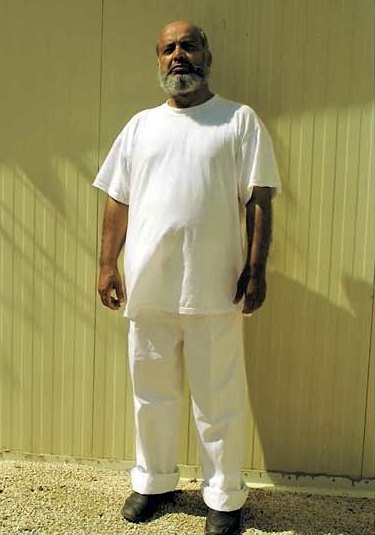

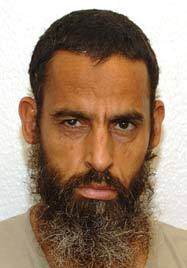

Bad news from Guantánamo for Saifullah Paracha, a Pakistani businessman, a victim of kidnap, extraordinary rendition and torture, and, at 68, the prison’s oldest prisoner, as his ongoing imprisonment has been recommended by a Periodic Review Board, following a hearing on March 8, which I wrote about here. The PRB process involves representatives of the Departments of State, Defense, Justice and Homeland Security, as well as the office of the Director of National Intelligence and the Office of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and it was established in 2013 to review the cases of all the prisoners not already approved for release by President Obama’s high-level, inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force, which reviewed all the prisoners’ cases in 2009, or facing trials (and just ten of the remaining 89 prisoners are in this latter category).

Bad news from Guantánamo for Saifullah Paracha, a Pakistani businessman, a victim of kidnap, extraordinary rendition and torture, and, at 68, the prison’s oldest prisoner, as his ongoing imprisonment has been recommended by a Periodic Review Board, following a hearing on March 8, which I wrote about here. The PRB process involves representatives of the Departments of State, Defense, Justice and Homeland Security, as well as the office of the Director of National Intelligence and the Office of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and it was established in 2013 to review the cases of all the prisoners not already approved for release by President Obama’s high-level, inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force, which reviewed all the prisoners’ cases in 2009, or facing trials (and just ten of the remaining 89 prisoners are in this latter category).

With this decision, 27 prisoners have had their cases decided, with 20 men approved for release, and just seven having their ongoing imprisonment approved. However, most of those approved for release were mistakenly described as “too dangerous to release” by the task force, while Paracha is from a smaller group of men initially recommended for prosecution until the basis for prosecutions largely collapsed, and in that group his is the second application for release that has been turned down, with just one success to date.

I have never found the case against Paracha — that he worked with Al-Qaeda in a plot or plots relating to the US — to be convincing, as he lived and worked as a successful businessman in the US from 1970-86, appears to be socially liberal, and has been a model prisoner at Guantánamo, where he has helped numerous younger prisoners engage with the various review processes established over the years. When his PRB took place, the authorities described him as as “very compliant” with the prison guards, with “moderate views and acceptance of Western norms.”

As I described his story nearly ten years ago in my book The Guantánamo Files:

Saifullah Paracha, a 55-year old businessman and philanthropist from Karachi, was arrested after flying into Bangkok for a business trip on 5 July 2003 [in a US-led sting operation]. Rendered to Afghanistan, he spent 14 months in Bagram and was then flown to Guantánamo on 20 September 2004. A graduate in computer science from the New York Institute of Technology, he acknowledged that he had met Osama bin Laden twice, at meetings of businessmen and religious leaders in 1999 and 2000, but denied the allegations against him, which included making investments for al-Qaeda members, translating statements for bin Laden, joining in a plot to smuggle explosives into the US and recommending that nuclear weapons be used against US soldiers. These were indeed wild accusations for anyone familiar with his story. Deeply impressed by all things American, he had lived in the US in the 1980s, running several small businesses, and after returning to Pakistan had made a fortune running a clothes exporting business in partnership with a New York-based Jewish entrepreneur (an unthinkable association for someone who was actually involved with al-Qaeda).

His case is inextricably tied to that of his 23-year old son Uzair, the eldest of his four children, who was detained in New York, where he was marketing apartments to the Pakistani community, four months earlier. Arrested by FBI agents, Uzair was accused of working with [the “high-value detainees”] Ammar al-Baluchi and Majid Khan … to provide false documents to help Khan enter the US to carry out attacks on petrol stations, and was convicted in a US court in November 2005 – even though he said that he was coerced into making a false confession, and both Khan and al-Baluchi made statements that neither Uzair nor his father had ever knowingly aided al-Qaeda – and was sentenced to 30 years’ imprisonment in July 2006. His father remains in Guantánamo, where, although he has heart problems, he has refused to undertake an operation because he does not trust the prison’s surgeons.

I also wrote more about Saifullah and Uzair Paracha in an article in July 2007, entitled Guantánamo’s tangled web: Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, Majid Khan, dubious US convictions, and a dying man.

Nevertheless, the US authorities still believe their version of events. For many years, Paracha was recommended for prosecution, including by the Guantánamo Review Task Force in 2009, and it was not until April 2013 that he was determined to be eligible, instead, for a Periodic Review Board.

in its Unclassified Summary of Final Determination, the Periodic Review Board decided, by consensus, that “continued law of war detention … remains necessary to protect against a continuing significant threat to the security of the United States.”

In making this determination, the review board “considered the detainee’s past involvement in terrorist activities, including contacts and activities with Usama Bin Laden, Kahlid [sic] Shaykh Muhammad and other senior aI-Qaeda members, facilitating financial transactions and travel, and developing media for al-Qaeda.”

The board also “noted the detainee’s refusal to take responsibility for his involvement with al-Qaeda, his inability and refusal to distinguish between legitimate and nefarious business contacts, his indifference toward the impact of his prior actions, and his lack of a plan to prevent exposure to avenues of reengagement.”

This wording is a pretty damning conclusion on the board’s part, although Paracha, of course, “cannot show ‘remorse’ for things he maintains he never did,” as his attorney, David Remes, explained to the board in March. On Thursday, after the board’s decision was announced, he said his client “will try to address the board’s concerns in his file review in October,” an administrative review that takes place six months after the initial PRB.

Below I’m posting Paracha’s own statement to the board, which was not publicly available when his review took place on March 8. In it, he said “that he was ‘duped’ into visiting Afghanistan and handling certain finances as part of charity work he did,” as the Miami Herald described it, and that he “said he met bin Laden in [his] role as chairman of a Karachi TV broadcasting studio, and sought an interview, which the studio never did get.”

In his statement, Paracha also refuted claims that he undertook research on chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear (CBRN) materials for al-Qaeda, as the US authorities claimed, and as Carol Rosenberg pointed out for the Miami Herald at the time of his PRB, the Senate Intelligence Committee’s report on the CIA’s torture program “casts doubt on CIA suspicions that the Parachas were trying to smuggle explosives into the United States, noting ‘the relative ease of acquiring explosive material in the United States.’”

Paracha also made a point of stating that he was not involved with al-Qaeda, noting, “I never worked with anybody to harm anyone in my life. My son Uzair and I were never involved for real.” He also refuted US claims that he was involved with the Pakistani extremist group Lashkar-e-Tayyiba, stating, “please do not think there are any relations between us. I am very liberal and their leaders are ultra conservative and fundamentalist. It is so disgusting how their leaders move around with bodyguards, holding guns over their shoulders. They have been exploiting poor innocent young generation. I will never align with them.”

Finally, he mentioned the former prisoner Jarallah al-Marri, released in July 2008, but evidently regarded with some suspicion by the authorities, contextualizing how he came to know him in Guantánamo — during recreation time when they were both held in isolation — and why that does not indicate anything more substantial. I met Jarallah in January 2009, when he visited the UK to take part in a tour organized by Cageprisoners with former guard Chris Arendt, prior to the UK government refusing to allow him to enter the country for a second time in February 2009, and was given no reason for thinking that he was a danger to the US.

Paracha’s case obviously continues to divide opinion, and I have no idea if he will be able to make a better case for his release in the future, but I do find a lack of substance to claims of the danger he poses, compared to his obvious efforts within Guantánamo to steer younger and more impressionable prisoners away from radicalization by encouraging them to engage with all the review processes and interaction offered to them.

Periodic Review Board Initial Hearing, 08 Mar 2016

Saifullah Abdullah Paracha, ISN 1094

Detainee Statement

Honorable Board,

My name is Saifullah Paracha. I was captured in Bangkok, Thailand on July 06, 2003 and transferred to Afghanistan. On the first day of my interrogation, I voluntarily gave complete details about my meeting with Osama Bin Laden. Just for quick reference I briefly give you some details.

I was chairman of an NGO Council of Welfare Organization (WCO). I was duped by the trustees to visit Afghanistan and extend our charity work to poor Afghans. I felt extremely pathetic towards Afghans, therefore; I prepared a small booklet on Afghanistan and requested Pakistan to make investment in basic cottage industries and in farming to create jobs rather than donation. That report was published in the newspaper. Pakistan Rice Exporters Association requested me to lead a delegation of about 90 business men and others to Afghanistan. In Kandahar, before the Taliban’s Governor and Ministers, I made a humble presentation to the delegations to teach Afghans “to catch fish rather than feed them fish.”

After the presentation, a gentleman approached me and praised my efforts. He asked me questions about my background and told me his name was Maulana Mahar. He invited me to meet Osama Bin Laden (OBL). OBL had a very controversial personality; he had close alliance with US during U.S.S.R. invasion in 1978 into Afghanistan. OBL was very popular and respected among most Muslim community. He was known throughout the world while the western countries portrayed him as a devil. He was from a very rich and influential Saudi family. His father was close friends of the Saudi King.

I was among the 12-15 audience members who heard him speak of the Holy Qur’an in a light tone and about the Prophet Mohammad saying (Ahadees). He said nothing hateful or negative about the west or any other nation. I was a chairman of Universal Broadcasting, Karachi which was a television recording studio. I saw an opportunity and requested him to record a T.V. program in English and gave him my card. He said he would think about it and someone would contact me. After I came back I had an opportunity to meet Secretary House Affairs, Pakistan. The Pakistan and Taliban governments had diplomatic relations, similar to the U.S. and Canada. I also visited the Pakistani Ambassador in Afghanistan.

We had a large office (10,000 sq ft on the 8th floor), operating several businesses under my chairmanship and major stockholders. These businesses included International Merchandise (IMG), Universal Broadcasting , Abson Industries, Cliftonia-Real Estate Developers, and the Council of Welfare Organization. We had a large reception area with two young female receptionists and our own security guard. On the front wall ofwe had two crossed flags, “Pakistan and U.S.A.”

One day the receptionist called me to say a gentleman who has my card from Afghanistan wants to see me. Our security guard brought him to my office in the IMGs office. He introduced himself as “Meer”. Meer is a very large tribe in Sind, Pakistan. This man was from Nawanshahr, an agriculturist. He presented my business card and told me he received a message to see me about recording T.V. programs from Afghanistan. He also told me, he helps in media related matters.

Meer was dressed in causal western dress, spoke URDU Pakistani and English clearly, was clean shaven and showed no signs of extremist personality. After U.S.S.R. invaded Afghanistan, a Holy war declared against infidel communist by Muslims worldwide and Jihad (freedom fighting) became fashionable and lucrative to raise money. Politicians, government officials and religious leaders were exploiting young Muslims. A large percentage of young male Pakistanis are still glorified for Jihad and they are everywhere, soliciting cash and kind. It is impossible to avoid them if you are living in Pakistan.

I showed Meer our studio, editing room and clips of our religious interviews and current affair programs. I proposed to make a small recording studio anywhere in Afghanistan, sound proof and proper lighting arrangements. Universal Broadcasting will pay. They can select and buy all recording equipment. He observed our staff in the IMG office, as our staff was busy and he asked about it. I explained to him and gave him our brochure. It gave brief details of our buying houses. We shook hands. He saw the U.S. and Pakistan flags and I told him about my partner, Charles Anteby. He did not show any concern and said he was also in the United States. Another visit he asked me to open a foreign exchange account in our bank and he deposited a check of 5000.00 in a non-interest bearing account. I suggested to him to make investment for some profit and he responded maybe later. In Pakistan there is a law that if Pakistan Muslim deposits money in the saving account, the government takes out 2.5% (Zakat) and gives it to the poor, irrespective of interest rate every Lunar year. So, it is very common for people to make investment with friends and relations or trusted companies. My partner Charles Anteby can witness, we had taken about two million for IMG after 9/11 when business slow down.

According to the profile I have been penalized for financial deals and TV programs I proposed making but no programs were recorded. I am a citizen of Pakistan. I brought this issue to responsible Pakistan official. There are many western media organization, who recorded hateful interviews and telecasted on their channels with Osama Bin Laden. There are many bankers who had all kinds of financial transactions and are not punished.

I have no idea what CBRN material is, I am ready to testify under oath that what CBRN stands for, and further I want to confirm, I did not make and search for any objectionable material.

With reference to a statement that I have shown no remorse working with al Qaida, as I described earlier about Mujahedeen, who is who, it’s very difficult to identify. Poor, young men from remote areas are glorified about life here after 70 virgins, garden, etc. They are programmed from a very young age. Some build palaces on their graves. I feel bad about this. I never worked with anybody to harm anyone in my life. My son Uzair and I were never involved for real. This is hateful thinking. I have been physically and financially involved in welfare work and I will never do my business based on profit before people. My loyalty is in the Creator and his creatures.

With reference to my resettlement I consider my two countries Pakistan and U.S.A. Since the U.S. does not facilitate transfer to the U.S., the only option left is Pakistan where my family needs me and I have a lots of assets and liabilities to take care. My businesses have suffered dearly. I had over 350 employees and they lost their livelihood. I will help my children start their family life and revive my businesses. Some senior politicians have requested the U.S. government to repatriate me back to Pakistan; one of them is a minister in the government now.

With reference to the Taliban, I am enclosing my letter dated Jan 21, 2002, before my captivity. I wrote about Afghanistan and how to bring peace. Pakistan’s stability and peace is now directly linked with Afghanistan. My motive’s is how we can end the suffering and destruction of Afghanistan and Pakistan. If U.S. wants me to stay away from Taliban, I will follow religiously.

With reference to Lashkar-e-Tayyiba, please do not think there are any relations between us. I am very liberal and their leaders are ultra conservative and fundamentalist. It is so disgusting how their leaders move around with bodyguards, holding guns over their shoulders. They have been exploiting poor innocent young generation. I will never align with them. Universal Broadcasting is closed now and there is reason to associate with various leaders. I also have no resources or appetite to start such business again.

With reference to my profile dated Oct 27, 2015 and my relationship with fellow detainee Jarallah al-Marri. I was captured in early July 2003 in Thailand and kept in Bagram. In Sept 2004, I was brought to Guantanamo. From 2004 to November 2008, I was kept in isolation. I speak Urdu and English and most detainees speak Arabic. Some speak a little English. I hardly had human contact. In the beginning I was taken to an open air area just for one hour daily. After many months I was allowed for recreation for two hours with another inmate with very little communication of some English words. I think it was 2007 when [redacted] I met Jarallah as he was in a cell opposite to mine. We were allowed 2 hours daily for recreation.

My family writes me and will always support me. My daughter has sent me letters because they need me at home as the support for the family. My son does well in his education. My wife needs me and my support. I have told you everything.

God willing please let me go home.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ is available for download or on CD via Bandcamp — also see here). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ is available for download or on CD via Bandcamp — also see here). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

April 13, 2016

Two London Events for Mohamedou Ould Slahi, Best-Selling Author Imprisoned in Guantánamo

Please ask your MP to attend the Parliamentary briefing for Mohamedou Ould Slahi next Tuesday, April 19.

Please ask your MP to attend the Parliamentary briefing for Mohamedou Ould Slahi next Tuesday, April 19.If you’re in London — or anywhere near — then I hope two events next week might be of interest to you, and even if you’re not, then I hope you’ll be interested in asking your MP to attend the first event, a Parliamentary briefing about Guantánamo prisoner Mohamedou Ould Slahi, next Tuesday, April 19. Slahi has no UK connection, but his plight should be of interest to all MPs who care about the rule of law, as Guantánamo remains a place of shameful injustice, whose closure all decent people need to support.

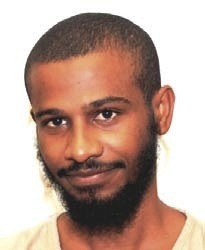

Both events involve the campaign to free Mohamedou Ould Slahi, one of the best-known prisoners still held in Guantánamo. A notorious victim of torture by the US, he is also the author of the best-selling book, Guantánamo Diary, an extraordinary account of his rendition, imprisonment and torture, written in Guantánamo and published, with numerous redactions, after a long struggle with the US authorities, to widespread acclaim in January 2015.

On the evening of Tuesday April 19, there will be a Parliamentary briefing for Slahi, hosted by Tom Brake MP (Liberal Democrat, Carshalton and Wallington), featuring the actors Jude Law, Sanjeev Bhaskar and Toby Jones, Slahi’s brother Yahdih and his lawyer, Nancy Hollander.

The following evening, Yahdid Ould Slahi and Nancy Hollander will be discussing Slahi’s case at ThoughtWorks in Soho.

The full details of both events are below, including RSVP information, but if you aren’t fully aware of Mohamedou Ould Slahi’s story, please first of all read my brief description from an article I wrote in February 2015, after his book was published:

A Mauritanian, born in 1970, Slahi was singled out for a specific torture program, approved by Donald Rumsfeld, in 2003. He had aroused US suspicions because he was related to Abu Hafs, the spiritual advisor to Al-Qaeda (who, lest we forget, opposed the 9/11 attacks), and because, while living in Germany in 1999, three would-be jihadists, including Ramzi bin al-Shibh, an alleged facilitator of the 9/11 attacks, had stayed for a night at his house.

However, although Slahi had trained and fought in Afghanistan in 1991-2, when, apparently, he had sworn allegiance to Al-Qaeda, that was the extent of his involvement with terrorism or militant activity, as Judge James Robertson, a District Court judge, concluded in March 2010, when he granted Slahi’s habeas corpus petition.

The Obama administration appealed Judge Robertson’s ruling, and in November 2010 the court of appeals — the D.C. Circuit Court — backed the government, vacating Judge Robertson’s ruling, and sending it back to the lower court to reconsider.

That never happened, and Slahi ended up abandoned. The high-level, inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force that President Obama established shortly after taking office in January 2009 had recommended him for prosecution in its final report two months before his habeas corpus petition was granted, and this stood until April 2013, when he was determined to be eligible for a new review process, the Periodic Review Boards, along with 24 other men who had initially been recommended for prosecution by the task force, and 46 others who had been recommended for ongoing imprisonment without charge or trial, on the profoundly dubious basis that they were too dangerous to release, but that insufficient evidence existed to put them on trial.

Slahi’s Periodic Review Board has now been scheduled — for June 2 — and it is to be hoped that the review board — which includes representatives of of the Departments of State, Defense, Justice and Homeland Security, as well as the office of the Director of National Intelligence and the Office of the Joint Chiefs of Staff — will approve his release, as with 20 of the 26 men who have been through the PRB process since it was established in November 2013, and who have had decisions taken. Four other men are awaiting the results of their PRBs, and 35 others are awaiting reviews.

Nevertheless, it is by no means apparent that Slahi’s PRB will approve his release, hence the need to maintain pressure on the Obama administration — and to push for support from diligent allies of the US, like the British Parliament.

I need hardly add that what is extraordinary about Slahi’s predicament is that it is impossible to imagine an American, held for 14 years without charge or trial — and tortured — by some other government, writing an account of his experiences, and eventually getting it published to widespread acclaim, with it topping several best-seller lists, without there being a huge uproar leading to his release, and yet Slahi has still not been freed.

Below are the full details of next weeks events:

Tuesday April 19, 2016, 6-7.30pm: Parliamentary briefing on the case of Mohamedou Ould Slahi

Grimond Room, Portcullis House, Westminster, London SW1A 2LW

With Jude Law, Sanjeev Bhaskar, Toby Jones, Mohamedou Ould Slahi’s brother Yahdih Ould Slahi, his lawyer Nancy Hollander, Jo Glanville, Director, English PEN and Jamie Byng, Publisher and Managing Director, Canongate Books. Moderated by Tom Brake MP.

Anyone can attend this event, although please allow time to clear security at Portcullis House. You can also let Bernard Sullivan know if you are coming, so that the organisers have some idea of how many are planning to attend.

Wednesday April 20, 2016, 6-8pm: Discussion about the case of Mohamedou Ould Slahi

Wednesday April 20, 2016, 6-8pm: Discussion about the case of Mohamedou Ould Slahi

ThoughtWorks, 76-78 Wardour Street, 1st Floor, Soho, London W1F 0TA

With Mohamedou Ould Slahi’s brother Yahdih Ould Slahi and his lawyer Nancy Hollander

There will be a buffet and drinks. If you would like to attend, please contact Suzie Gilbert.

Please also sign the ACLU’s Free Slahi petition to the US Secretary of Defense, Ashton Carter, which currently has just over 50,000 signatures, and see the ACLU’s Free Slahi page here.

And finally, I’m posting below an excerpt from Guantánamo Diary, published at the time of the book’s publication in the Guardian:

‘The torture squad was so well trained that they were performing almost perfect crimes’

The Guardian, January 18, 2015

I started to recite the Koran quietly, for prayer was forbidden. Once ________ said, “Why don’t you pray? Go ahead and pray!” I was like, How friendly! But as soon as I started to pray, ____ started to make fun of my religion, and so I settled for praying in my heart so I didn’t give ____ the opportunity to commit blasphemy. Making fun of somebody else’s religion is one of the most barbaric acts. President Bush described his holy war against the so-called terrorism as a war between the civilized and barbaric world. But his government committed more barbaric acts than the terrorists themselves. I can name tons of war crimes that Bush’s government is involved in.

This particular day was one of the roughest days in my interrogation before the day around the end of August that was my “Birthday Party” as _______ called it. _______ brought someone who was apparently a Marine; he wore a ________ _____________________________________________ __________________________________________.

_______ offered me a metal chair. “I told you, I’m gonna bring some people to help me interrogate you,” _______ said, sitting inches away in front of me. The guest sat almost sticking on my knee. _______ started to ask me some questions I don’t remember.

“Yes or no?” the guest shouted, loud beyond belief, in a show to scare me, and maybe to impress _______, who knows? I found his method very childish and silly.

I looked at him, smiled, and said, “Neither!” The guest threw the chair from beneath me violently. I fell on the chains. Oh, it hurt.

“Stand up, motherfucker,” they both shouted, almost synchronous. Then a session of torture and humiliation started. They started to ask me the questions again after they made me stand up, but it was too late, because I told them a million times, “Whenever you start to torture me, I’m not gonna say a single word.” And that was always accurate; for the rest of the day, they exclusively talked.

_______ turned the air conditioner all the way down to bring me to freezing. This method had been practiced in the camp at least since August 2002. I had seen people who were exposed to the frozen room day after day; by then, the list was long. The consequences of the cold room are devastating, such as ______tism, but they show up only at a later age because it takes time until they work their way through the bones. The torture squad was so well trained that they were performing almost perfect crimes, avoiding leaving any obvious evidence. Nothing was left to chance. They hit in predefined places. They practiced horrible methods, the aftermath of which would only manifest later. The interrogators turned the A/C all the way down trying to reach 0°, but obviously air conditioners are not designed to kill, so in the well insulated room the A/C fought its way to 49°F, which, if you are interested in math like me, is 9.4°C—in other words, very, very cold, especially for somebody who had to stay in it more than twelve hours, had no underwear and just a very thin uniform, and who comes from a hot country. Somebody from Saudi Arabia cannot take as much cold as somebody from Sweden; and vice versa, when it comes to hot weather. Interrogators took these factors in consideration and used them effectively.

You may ask, Where were the interrogators after installing the detainee in the frozen room? Actually, it’s a good question. First, the interrogators didn’t stay in the room; they would just come for the humiliation, degradation, discouragement, or other factor of torture, and after that they left the room and went to the monitoring room next door. Second, interrogators were adequately dressed; for instance ______ was dressed like somebody entering a meat locker. In spite of that, they didn’t stay long with the detainee. Third, there’s a big psychological difference when you are exposed to a cold place for purpose of torture, and when you just go there for fun and a challenge. And lastly, the interrogators kept moving in the room, which meant blood circulation, which meant keeping themselves warm while the detainee was _________ the whole time to the floor, standing for the most part. All I could do was move my feet and rub my hands. But the Marine guy stopped me from rubbing my hands by ordering a special chain that shackled my hands on my opposite hips. When I get nervous I always start to rub my hands together and write on my body, and that drove my interrogators crazy.

“What are you writing?” ___________ shouted. “Either you tell me or you stop the fuck doing that.” But I couldn’t stop; it was unintentional. The Marine guy started to throw chairs around, hit me with his forehead, and describe me with all kinds of adjectives I didn’t deserve, for no reason.

“You joined the wrong team, boy. You fought for a lost cause,” he said, alongside a bunch of trash talk degrading my family, my religion, and myself, not to mention all kinds of threats against my family to pay for “my crimes,” which goes against any common sense. I knew that he had no power, but

I knew that he was speaking on behalf of the most powerful country in the world, and obviously enjoyed the full support of his government. However, I would rather save you, Dear Reader, from quoting his garbage. The guy was nuts. He asked me about things I have no clue about, and names I never heard.

“I have been in __________,” he said, “and do you know who was our host? The President! We had a good time in the palace.” The Marine guy asked questions and answered them himself.*

When the man failed to impress me with all the talk and humiliation, and with the threat to arrest my family since the ______________ was an obedient servant of the U.S., he started to hurt me more. He brought ice-cold water and soaked me all over my body, with my clothes still on me. It was so awful; I kept shaking like a Parkinson’s patient. Technically I wasn’t able to talk anymore. The guy was stupid: he was literally executing me but in a slow way. _______ gestured to him to stop pouring water on me. Another detainee had told me a “good” interrogator suggested he eat in order to reduce the pain, but I refused to eat anything; I couldn’t open my mouth anyway.

The guy was very hot when _______ stopped him because ____ was afraid of the paperwork that would result in case of my death. So he found another technique, namely he brought a CD player with a booster and started to play some rap music. I didn’t really mind the music because it made me forget my pain. Actually, the music was a blessing in disguise; I was trying to make sense of the words. All I understood was that the music was about love. Can you believe it? Love! All I had experienced lately was hatred, or the consequences thereof.

“Listen to that, Motherfucker!” said the guest, while closing the door violently behind him. “You’re gonna get the same shit day after day, and guess what? It’s getting worse. What you’re seeing is only the beginning,” said _______. I kept praying and ignoring what they were doing.

“Oh, ALLAH help me…..Oh Allah have mercy on me” ____ kept mimicking my prayers, “ALLAH, ALLAH…. There is no Allah. He let you down!” I smiled at how ignorant ____ was, talking about the Lord like that. But the Lord is very patient, and doesn’t need to rush to punishment, because there is no escaping him.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ is available for download or on CD via Bandcamp — also see here). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ is available for download or on CD via Bandcamp — also see here). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

April 12, 2016

Emad Hassan’s Story: How Knowing a Town Called Al-Qa’idah Got Him 13 Years in Guantánamo

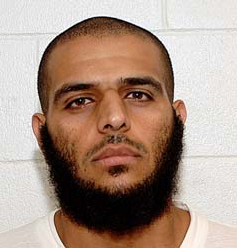

Last week, I published an article about the latest releases from Guantánamo — two Libyans, one of whom was Omar Mohammed Khalifh, a Libyan amputee seized in Pakistan in a house raid in 2002.

Last week, I published an article about the latest releases from Guantánamo — two Libyans, one of whom was Omar Mohammed Khalifh, a Libyan amputee seized in Pakistan in a house raid in 2002.

Khalifh had been approved for release last September by a Periodic Review Board — a process set up two and a half years ago to review the cases of all the men still held at Guantánamo who were not either facing trials (just ten men) or had not already been approved for release in 2010 by another review process, the Guantánamo Review Task Force.

Until the PRB’s decision was announced, I thought Khalifh had been seized in a house raid in Karachi, Pakistan in February 2002, but the documentation for the PRB revealed that he had been seized in a house raid in Faisalabad on March 28, 2002, the day that Abu Zubaydah, a training camp facilitator mistakenly regarded as a senior member of Al-Qaeda, was seized in another house raid. I had thought that 15 men had been seized in the raid that, it now transpires, also included Khalifh, but I had always maintained that they had been seized by mistake, as a judge had also suggested in 2009, and in fact 13 of them have now been released (and one other died in 2006), leaving, I believe, just two of the 16 still held.

One of the 16 was Emad Hassan, a Yemeni released in Oman last June, who had been a long-term hunger striker (and who I have written about extensively). Emad was the subject of an article last September in Newsweek, which I’m cross-posting below. I had intended to post it back in the fall, but was distracted by my involvement in a last-minute campaign for the release of British resident Shaker Aamer, the Fast For Shaker campaign that Joanne MacInnes and I, the co-founders of the We Stand With Shaker campaign, set up just a few weeks after the article was first published.

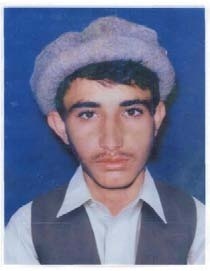

The article is based on the fact that, after Emad Hassan’s capture, he was asked if he had any connection to Al-Qaeda, and said yes, although he was referring not to the terrorist organisation, but to Al-Qa’idah, a town near where he grew up in Yemen. Nevertheless, this was enough for those masquerading as intelligence analysts to conclude that he was a threat to the US.

This kind of mistake is typical of the often inept gathering of information about the prisoners held at Guantánamo, and the author of the Newsweek article, Lauren Walker, did a good job in pointing out how unreliable so much of what purports to be evidence against the prisoners actually is. She notes that Emad Hassan’s lawyers, at Reprieve, “claim much of the U.S. government’s incriminating information comes from a small group of informants at Guantánamo who told interrogators what they wanted to hear. Many sold out their fellow detainees for small rewards. Some reportedly received PlayStations and pornography for their assistance. Others were mentally ill or say they were tortured.”

However, what is particularly interesting about her article is information provided by John Kiriakou, an ex-CIA officer, who, as she notes, “was later imprisoned for nearly two years for emailing a reporter the name of a fellow officer.” Kiriakou called the series of house raids on March 28, 2002, which he helped organize, “the largest raid in the CIA’s history.” As Walker puts it, “Fourteen houses were raided and 52 people were taken prisoner that night,” according to Kiriakou, who also explained that the house in which Emad Hassan was captured “was a last-minute addition. Each house was targeted because it had been in frequent electronic contact with an Al-Qaeda affiliate. But Hassan’s had just one short call on record. The day before the raid, an unnamed foreign government called to give the CIA a tip; an informant said it was an Al-Qaeda safe house.”

Kiriakou told Walker that, after the raids, “he lost track of the ‘lower-level guys,’ as he focused on Abu Zubaydah, although he also recalled “a series of errors in the lead-up to the raid,” based on “faulty intelligence” that, I suspect, was replicated in relation to the Issa House, where Hassan and the 15 other men were seized. As Walker put it, “One suspected safe house turned out to be shish kabob stand with a pay phone … Another was a girls school. The CIA-led team stormed in and arrested an old man and his two sons. The agency later discovered the men had allowed strangers to use their phone for 5 rupees per call.” As Kiriakou said, “Were there innocent Arabs in some of those houses? I wouldn’t be surprised if the answer was yes.”

There’s much more in Lauren Walker’s article and I hope you have the opportunity to read it in its entirety — with its harrowing sections on Hassan’s eight-year hunger strike and recollections by his lawyers about his intelligence and his delight in reading. I was disappointed that, towards the end of the article, she mentioned that dozens of those still held “are considered too dangerous to be released, but there’s not enough evidence to charge them,” without qualifying that designation, as these are the men facing Periodic Review Boards, men like Omar Mohammed Khalifh, who falsely incriminated himself because he couldn’t stand the pressure exerted on him by the authorities, who were desperate for “confessions.” — and he, of course, is not unique. In 20 out of 26 cases so far decided by the PRBs, the board members have recommended them for release, and it seems likely, therefore, that many others considered too dangerous to be released by Obama’s task force, despite there being insufficient evidence to put them on trial, will also be recommended for release after their PRBs because, as with Khalifh, the “evidence” is actually fundamentally unreliable.

How a Botched Translation Landed Emad Hassan in Gitmo

By Lauren Walker, Newsweek, September 10, 2015

“Do you have any connection to Al-Qaeda?” the man asked.

“Do you have any connection to Al-Qaeda?” the man asked.

It was the spring of 2002, and Emad Hassan was sitting in a chair in a small tent, hands cuffed behind his back. Standing in front of him were a young American soldier and his Arabic translator. The soldier barked at him in English, a language Hassan barely understood, and the translator repeated his words in broken Arabic.

For weeks, Hassan, a small, soft-spoken 22-year-old with dark skin and curly hair, had been held by the Americans in Afghanistan. Born and raised in Yemen, he traveled to Faisalabad, Pakistan, in the summer of 2001 to study the Koran at a small university. But one evening the following spring, Pakistani authorities burst into the house he shared with 14 other foreign students and brought them to a nearby prison. After two months of beatings and interrogation, the Pakistanis handed him over to the U.S. military.

Eventually, Hassan found himself in front of the young American in what he later learned was the U.S. military prison in Kandahar. Confused and afraid, his lawyers say, Hassan decided it was best to continue telling the truth. “Yes,” Hassan said, according to his lawyers, he had a connection to Al-Qaeda. He waited for the next question, but the soldier and the translator seemed satisfied. The interrogation was over. What was lost in translation, Hassan’s lawyers say: The soldier thought he was talking about Al-Qaeda, the deadly terrorist group. Hassan was actually referring to Al-Qa’idah, a village 115 miles from where he grew up in Yemen.

Weeks later, prison guards came into Hassan’s cell. They stripped him of his clothes and put him in a diaper. Then they blindfolded him, placed earmuffs over his head and marched him onto a plane. When the aircraft landed, he soon learned he was in the U.S. prison at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba. What had started as a comic misunderstanding became a surreal odyssey through the dark side of America’s war on terror.

‘The Worst of the Worst’

In his satirical novel, From the Memoirs of a Non-Enemy Combatant, writer Alex Gilvarry tells the story of Boy Hernandez, a fashion designer mistaken for a terrorist. Like Hassan, Hernandez is sent to Guantánamo Bay. But while Gilvarry’s fictional journey has darkly humorous twists (Hernandez’s PR agent is named Ben Laden), there is nothing funny about the ordeal that prisoners — some of whom are allegedly innocent — have endured behind bars at the U.S. facility.

After the September 11 attacks, the U.S. government used parts of the longtime U.S. Navy base at Guantánamo to hold prisoners who Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld called “the worst of the worst” in the fight against Al-Qaeda. Some detainees like Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the alleged mastermind of 9/11, are widely considered hardened terrorists. In recent years, however, new information has undercut Rumsfeld’s claims and indicated that few Gitmo detainees were major players in the war against America.

But Rumsfeld’s words stuck, both in the minds of the public and the people who worked at the prison. “Especially in the early days, everyone was pissed,” says Brandon Neely, a guard when the first detainees arrived on January 11, 2002. “People knew people that died in the twin towers. We had friends in Afghanistan. We wanted to do what we could to get revenge.”