Andy Worthington's Blog, page 74

May 31, 2016

The Man They Don’t Know: Saeed Bakhouche, an Algerian, Faces a Periodic Review Board at Guantánamo

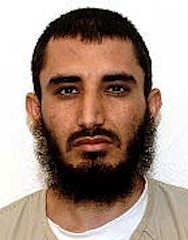

On Tuesday May 24, Saeed Bakhouche, a 45-year old Algerian who has been held in the US prison at Guantánamo Bay since June 2002, became the 40th prisoner to face a Periodic Review Board at Guantánamo.

On Tuesday May 24, Saeed Bakhouche, a 45-year old Algerian who has been held in the US prison at Guantánamo Bay since June 2002, became the 40th prisoner to face a Periodic Review Board at Guantánamo.

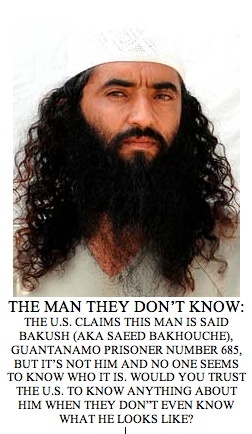

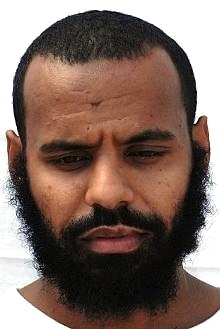

Like many Guantánamo prisoners, Bakhouche has also been known by another name – in his case, Abdel Razak Ali, a name he gave when he was captured – but to the best of my knowledge he is the only prisoner whose classified military file, compiled in 2008 and released by WikiLeaks in 2011, has a photo that purports to be him, but is not him at all. No one seems to know who it is, but it is not Saeed Bakhouche.

Moreover, his attorney, Candace Gorman, told me that a different photo – again, not of her client – was displayed outside his cell for a year and a half, a mistake that had disturbing ramifications, because this was the same photo shown to other prisoners during interrogations, leading to a situation whereby information about someone else was added his file as though it related to him.

The fact that the US authorities have, historically, not known who Saeed Bakhouche is, does not, however, appear to have been conveyed to the members of his PRB, which involves representatives of the Departments of State, Defense, Justice and Homeland Security, as well as the office of the Director of National Intelligence and the Office of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Set up in 2013, the boards are reviewing the cases of 46 men previously described, by the high-level, inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force that President Obama established shortly after taking office, as “too dangerous to release,” although that has turned out to have been outrageous hyperbole. Of the 40 men whose cases have so far been reviewed, eleven are awaiting decisions, just seven have had their ongoing imprisonment approved, while 22 have had their release recommended — and nine of those have, to date, been freed.

20 of those whose release has been recommended by PRBs were originally described as “too dangerous to release” by the task force, while two others are amongst 18 other men put forward for PRBs who were initially recommended for prosecution by the task force until the basis for prosecutions largely collapsed. This was in 2012-13, when appeals court judges in Washington, D.C. — in the D.C. Circuit Court, well-known for its preponderance of conservative judges — nevertheless dismissed two of the only convictions secured in Guantánamo’s troubled military commission trial system, on the inarguable basis that the war crimes in question — providing material support for terrorism and conspiracy — had actually been invented by Congress.

A cursory glance at Saeed Bakhouche’s case suggests that he would have been a candidate for prosecution, as he was seized in a house raid in Faisalabad, Pakistan on March 28, 2002 that secured the capture of Abu Zubaydah, regarded as a “high-value detainee,” for whom the CIA’s brutal and ineffective post-9/11 torture program was first developed. Crucially, the Bush administration’s claims that he was a significant figure in Al-Qaeda — no. 3 in the organization, after Osama bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri — have been thoroughly discredited in the years since, and in 2009 the Justice Department conceded that he was not a member of Al-Qaeda, and probably had not known in advance about the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001.

Instead, Abu Zubaydah was the gatekeeper of a independent training camp in Afghanistan, Khaldan, which was not affiliated with Al-Qaeda, and which was closed by its emir, Ibn al-Shaykh al-Libi, after Osama bin Laden sought to bring it under Al-Qaeda’s control. The evidence suggests that, after the US-led invasion of Afghanistan, Abu Zubaydah, as would be expected from someone with a great experience of logistics, was responsible for helping men, women and children – civilians as well as soldiers – to escape from the chaos of Afghanistan, and to wait in Pakistan until arrangements could be made for them to return home.

However, at the same time that the wildly exaggerated claims of Abu Zubaydah’s importance were dropped, the Justice Department, evidently desperate to cling to some reason for having tortured him, came up with a new claim — that he had been the head of a militia force that was aligned with Al-Qaeda.

January 2011: Saeed Bakhouche’s habeas corpus petition is turned down

Saeed Bakhouche was caught up in this unlikely scenario when his habeas corpus petition was turned down by District Judge Richard Leon in January 2011. As I explained at the time, in an article entitled, “Algerian in Guantánamo Loses Habeas Petition for Being in a Guest House with Abu Zubaydah”:

Ali [Bakhouche] arrived at Guantánamo in June 2002, after being subjected to abuse in Pakistani custody and in US custody in Afghanistan, and has, presumably, always been thought of as being part of a group associated with Abu Zubyadah, even though there are verifiable problems with this presumption.

The first is that, when four of the other men seized in the raid were put forward for a trial by Military Commission in June 2008, he was not included; the second is that, in November 2008, another Algerian seized in the house, Labed Ahmed, was freed, after the Bush administration accepted his explanation that he had been delivered to the house by mistake, but had nevertheless been allowed to stay; and the third is because the government’s reliance on claims that Abu Zubaydah was a significant terrorist have been thoroughly discredited.

The four men put forward for military commission trials in June 2008 were Noor Uthman Muhammed (from Sudan), who eventually accepted a plea deal in a military commission trial, and was released in December 2013, Ghassan al-Sharbi and Jabran al-Qahtani, both Saudis, and Sufyian Barhoumi, another Algerian. The latter three are also facing PRBs. No date has yet been set for al-Sharbi, but al-Qahtani’s PRB took place on May 19, which I wrote about here, and I will soon be writing about Barhomi’s PRB, which took place on May 26.

Back in January 2011, the government ambushed Saeed Bakhouche by claiming it had a diary written by one of Abu Zubaydah’s associates — a man whose whereabouts and true identity were unknown, so he could not be questioned in any way — which, the government alleged, not only confirmed the existence of the militia, but also indicated that it included Bakhouche, under a previously unknown alias, Usama al Jaza’iri.

This was not the only example of the government playing games with Bakhouche. As I also explained in my article:

[O]n December 24, [2010,] the government withdrew a key allegation on which, until that date, it had been relying, having discovered that it contained “potentially exculpatory information that the Government had not turned over to detainee counsel because it was classified at a higher classification level than detainee counsel was authorized to view.”

That statement, made by another Guantánamo prisoner who was not even seized with Zubaydah and Ali, but was captured in a house raid in Karachi six months later, apparently related to a claim by the prisoner in question that he had seen Ali in Afghanistan, and its removal not only emphasizes the general unreliability of the government’s supposed evidence, but also indicates how difficult it is for prisoners’ defense teams to be sure that they have been given given access to all the exculpatory material they need to defend their clients.

In any other circumstance, the withdrawal of a key piece of evidence would have led to a new hearing, but with Guantánamo the normal rules do not apply, and while Abdul Razak Ali clearly has grounds to appeal, it seems unlikely that he will be able to dislodge the lies and misconceptions about Abu Zubaydah that have become accepted in the D.C. Circuit Court, or to challenge the dubious nature of statements made by his fellow prisoners, or that he will be able to succeed in reminding judges about the clear precedent for releasing a man who had nothing to do with Abu Zubaydah, as was established in the case of Labed Ahmed.

December 2013: The D.C. Circuit Court turns down Saeed Bakhouche’s appeal

Nearly three years after Saeed Bakhouche’s habeas corpus petition was turned down, his appeal was, predictably, turned down by the D.C. Circuit, which, in a series of rulings from 2009 up to the fall of 2011, had, for ideological reasons, thoroughly undermined the Supreme Court’s ruling, in June 2008, that the prisoners had constitutionally guaranteed habeas corpus rights. The court eventually gutted habeas corpus of all meaning for the Guantánamo prisoners by ruling that any information presented by the government that purported to be evidence had to be regarded as presumptively accurate, unless the prisoners and their lawyers could establish a clear case that it wasn’t – a tall order for men held at Guantánamo with little, if any means of seeking out exculpatory evidence in their cases.

In “The Mirror of Guantánamo,” an important article for the New York Times shortly after this ruling, Linda Greenhouse examined the largely unnoticed importance of Bakhouche’s failed appeal, running though the history of the legal basis for detention in the “war on terror,” and also examining “the burden of proof the government has to shoulder in proving that the detainee fits the definition.” As she noted, “Both parts have been hotly contested, but the Ali case strongly suggests that the contest is over.”

Examining the legal basis for detention, Greenhouse began with the Authorization for the Use of Military Force, passed just days after the 9/11 attacks, which allowed the president to “use all necessary and appropriate force against those nations, organizations, or persons he determines planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001, or harbored such organizations or persons.” As Greenhouse noted, “While Congress spoke of force, and not detention, the Supreme Court in 2004 held that the power to detain those who were ‘part of or supporting forces hostile to the United States or coalition partners’ in Afghanistan was an inherent part of the power to use military force there that Congress had granted.”

The detention powers were subsequently tweaked slightly, by George W. Bush’s Pentagon, the Obama administration — which indicated that the support necessary for detention had to be “substantial” and not “insignificant,” and which also made clear that “the definition applied anywhere in the world and was ‘not limited to persons captured on the battlefields of Afghanistan’ or to those ‘directly participating in hostilities’” — and by Congress, in the 2012 National Defense Authorization Act.

Turning to the burden of proof, Greenhouse noted, “These different iterations, each building subtly on what had gone before, have left plenty of room for judicial interpretation. The D.C. Circuit, with exclusive jurisdiction over the Guantánamo habeas cases, has jumped into the gaps. It has endorsed the government’s view that evidence should be viewed holistically, as a composite, even if individual pieces are missing or might have a benign explanation.”

She added, “The Ali case exemplified this approach. For example, when he was captured, Mr. Ali was staying at a guesthouse with Abu Zubaydah,” who she then wrongly described as “an Osama bin Laden ally who is now one of the highest of high-value detainees at Guantánamo.”

Continuing, she wrote:

Mr. Ali had been at the four-bedroom house for 18 days, and was studying English. The Zubaydah forces were known to teach English to terrorists in training, and others who were later determined to be enemy combatants had been captured at the same or similar houses.

The D.C. Circuit rejected the argument by Mr. Ali’s lawyers that it was applying a standard of “guilt by guesthouse.” The court said that “determining whether an individual is part of Al Qaeda, the Taliban, or an associated force almost always requires drawing inferences from circumstantial evidence, such as that individual’s personal associations.” Mr. Ali, Judge Brett M. Kavanaugh’s opinion concluded, “more likely than not was part of Abu Zubaydah’s force.”

Greenhouse also noted the strenuous objections made by one member of the D.C. Circuit, Judge Harry T. Edwards, formerly the court’s chief judge, who was part of the panel for Bakhouche’s appeal. In June 2013, as I discussed here, Judge Edwards had complained about how his fellow judges had turned down the habeas corpus petition of a Yemeni prisoner, Abdul al-Qader Ahmed Hussain, seized in another house raid on the same day as the raid on Abu Zubaydah’s house.

As she described it:

The other two judges on the panel, Karen LeCraft Henderson and Thomas B. Griffith, said it was appropriate to draw inferences from the facts the government presented about Mr. Hussain’s travels, affiliations and multiple stays in mosques owned by a Qaeda-affiliated Islamic missionary group, Jama’at al-Tablighi, known as J.T. [and which, it should be noted, is in fact a missionary organization with millions of members worldwide]. These facts, the two judges said, supported the conclusion that Mr. Hussain, a teenager at the time of his capture, was “a part of Al Qaeda or the Taliban when he was captured.”

Judge Edwards objected, quoting from the Authorization for the Use of Military Force, that “there is not one iota of evidence that Hussain ‘planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001, or harbored such persons.’” The government failed to carry its ostensible preponderance-of-the-evidence burden, Judge Edwards said. “I am disquieted by our jurisprudence,’ he added. “The time has come for the president and Congress to give serious consideration to a different approach for the handling of Guantánamo detainee cases.”

Turning to Judge Edwards’ contributions to Saeed Bakhouche’s appeal, Linda Greenhouse wrote:

While agreeing with the result, which he said was compelled by the circuit’s precedents, he again wrote a separate opinion. He said that the “personal associations” test the majority applied was “well beyond” the detention definition prescribed by Congress in the Authorization for the Use of Military Force and the more recent amendment. “It seems bizarre, to say the least,” Judge Edwards said, “that someone like Ali [Bakhouche], who has never been charged with or found guilty of a criminal act and who has never ‘planned, authorized, committed or aided any terrorist attacks,’ is now marked for a life sentence.” He said the circuit had “stretched the meaning” of the congressional enactments “so far beyond the terms of these statutory authorizations that habeas corpus proceedings like the one afforded Ali are functionally useless.”

This was an extremely powerful criticism of the Circuit Court’s overreach, but it yielded neither a climbdown by the court, nor any sign that the Supreme Court was perturbed by how its Boumediene ruling, granting the prisoners constitutionally guaranteed habeas corpus rights, had been gutted of all meaning by a lower court, as has been apparent every time requests have been made for the Supreme Court to intervene — see my article from June 2012, “The Supreme Court Abandons the Guantánamo Prisoners,” for example, and another article from September 2012, “Obama, the Courts and Congress Are All Responsible for the Latest Death at Guantánamo.”

Saeed Bakhouche’s Periodic Review Board

In the government’s unclassified summary for Saeed Bakhouche’s PRB, which described him as Said Bin Brahim Bin Umran Bakush, aka Abdul al-Rizak, it was stated that he “was a trusted associate of prominent al-Qa’ida facilitator Abu Zubaydah (GZ-10016) and al-Qa’ida trainer lbn al-Shaykh al-Libi (LY-212).” Neither description is accurate, because, as noted above, neither Zubaydah nor al-Libi were members of Al-Qaeda, and the Khaldan camp, led by al-Libi, and for which Abu Zubaydah was a facilitator, was an independent camp that Osama bin Laden had wanted shut down after al-Libi refused to allow it to come under al-Qaeda’s control.

In a report on Bakhouche’s PRB, Courthouse News mistakenly stated that “US forces say they captured Bakush at a safe house in Faisalabad, Pakistan, in March 2002, along with … Abu Zubaydah and … lbn al-Shaykh al-Libi,” but in fact al-Libi had already been captured, fleeing Afghanistan in November or December 2001, and while Abu Zubaydah’s post-capture odyssey was one of the bleakest in the “war on terror,” as he was sent first to Thailand and then Poland to be tortured in CIA “black sites,” al-Libi’s treatment was no better. Sent by the CIA to Egypt, he made a false allegation, under torture, that Saddam Hussein had been meeting with senior Al-Qaeda figures to discuss providing them with chemical and biological weapons, a lie that was used to justfy the illegal invasion of Iraq in March 2003. Al-Libi himself was shunted around various “black sites” before being returned to Col. Gaddafi’s Libya, where — conveniently for everyone involved — he died, allegedly by committing suicide, in May 2009.

The government’s unclassified summary for Bakhouche’s PRB continued by stating, “We assess that in the late 1990s, [he] traveled to Afghanistan, where he attended basic and advanced training and later served as an instructor at an extremist camp” — a reference to Khaldan. The summary added that Bakhouche “was captured at a safehouse with Zubaydah in March 2002, where safehouse members were training for future attacks, including against US interests.” It has never been verified independently if there is any truth in these claims. Bakhouche’s classified military files, released by WikiLeaks in 2011, contained more detailed allegations — suggesting that he was “arrested at a Faisalabad safe house as a member of GZ-0016’s [Abu Zubaydah’s] Martyr’s Brigade, a fighting unit that was preparing to conduct an IED insurgency campaign against US and Coalition forces in Afghanistan and ultimately carry out attacks against targets in the US” — but, as I noted above, in my discussions of Bakhouche’s habeas corpus petition, claims made about the existence of this militia, identified as the Martyr’s Brigade, are not necessarily reliable.

Turning to Bakhouche’s behavior in Guantánamo, the US authorities noted that he “has committed a low number of disciplinary infractions compared to other detainees and the majority of his infractions have been failures to comply with Guantánamo guard force orders,” adding that he “has assaulted or attempted to assault guard forces or other detainees on occasions, including a February 2015 incident in which he struck another detainee.”

It was also noted that Bakhouche “has never admitted to any involvement in extremist activities,” and that, because of this, and because he “has provided conflicting information to interrogators,” the authorities “lack insight into what motivated his activities before detention and whether he would pursue extremist activity after detention.” However, noticeably, he “has not expressed or demonstrated any sympathy or support for al-Qa’ida, its global jihadist ideology, or radical Islamic views,” and “has not had any contact with anyone outside of Guantánamo,” apart from with his legal counsel.”

The authorities also noted that he “has not shown a strong interest in his release, but when asked, said it would be okay if he went to a Western country.” This reticence may be because of his fears about being repatriated, which, in turn, may be what made him lie about his name and nationality after his capture, although this is not reflected in the authorities’ description, which is as follows: “After lying about his nationality for two years, [he] noted that he did not want to return to Algeria because he feared authorities would immediately arrest him.”

The summary also noted that “Algeria has advanced CT [counter-terrorism] capabilities and is committed to working with the US on terrorism and sharing information with the US. AQIM [Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb] and ISIL’s official branch in Algeria have been forced into remote areas of the country by counterterrorism pressure, but remain capable of conducting attacks.” Crucially, the summary added, “We have no reporting that either terrorist group has attracted any of the Guantánamo detainees that were transferred to Algeria.”

And finally, in terms of post-release work intentions — something the review boards are looking for, in addition to remorse and a lack of violent, anti-American rhetoric and threats — the summary noted that Bakhouche “indicated to interrogators that he has held a variety of menial jobs, and could return to such employment if resettled.”

Below I’m cross-posting the opening statement made by Bakhouche’s personal representatives, who are military personnel appointed to help the prisoners prepare for their PRBs. They told the board members that he “has been a quiet, compliant detainee earning the respect of his fellow detainees and detention facility staff,” and that he hopes to find work as a long-haul truck driver after his release — although, expanding on the mention of jobs in his summary, they added that he has also worked as a waiter, a welder, a fruit picker and a baker.

Periodic Review Board Initial Hearing, 10 May 2016 [actually 24 May 2016]

Said Bin Brahim bin Umran Bakush, ISN 685

Personal Representative Opening Statement

Good morning, ladies and gentlemen of the Board. We are the Personal Representatives (PR) for ISN 685, Mr. Said Bakush. We will be assisting Mr. Bakush with his case this morning.

Said has been overjoyed and eager to participate in the Periodic Review process since we first met with him 16 March 2016. When we explained why we were meeting with Said, he mentioned his fellow detainees had talked about their initial meetings with PRs. This filled him with cautious optimism about his own forthcoming meeting with his PRs. Said has maintained a positive attitude throughout all of our meetings.

Throughout our meetings, Said has expressed his desire to be transferred from Guantánamo Bay. He is open to transfer to any country, which will be helpful considering Said also speaks a regional dialect of French from Northern Africa, as well as Arabic. He is willing to participate in any rehabilitation or reintegration program as well.

Said looks forward to life after his transfer from Guantánamo Bay, meeting a woman to be his future wife, and starting a family together with her. He also hopes at some point in the future to return to his birthplace to reconnect with his siblings’ families and other relatives. Said did not have one career path prior to his detention.

Though his formal education ended at third grade, he worked many seasonal part-time jobs ranging from restaurant server, construction welder, vineyard harvester, and baking regional traditional breads and desserts. Said also served a two-year enlistment in the Algerian military upon reaching adulthood.

During his time here at Guantánamo, Said realized, once transferred, he could start a thriving career in driving long-haul trucks and operating / managing a small trucking business delivering food and products to other regional businesses and restaurants. This plan will build upon truck driving training he learned as an enlisted soldier in the Algeria military. His prior part-time job experiences give him an advantage in terms of understanding what seasonal products to prioritize at his future trucking business and will help him to find employment regardless of where he is transferred.

Said has been a quiet, compliant detainee earning the respect of his fellow detainees and detention facility staff. By being exposed to so many people of various cultural and religious backgrounds here at GTMO, Said has had many opportunities to better understand and appreciate their beliefs and customs. This exposure to other nations’ people, cultures and religious faiths will serve him well wherever he is transferred.

We are confident that Said’ s desire to pursue a peaceful way of life if transferred from Guantánamo Bay is genuine and that he does not harbor negativity towards anyone. We remain convinced that Said does not pose a significant threat to security of the United States or any of its interests.

Thank you for your time and attention and we look forward to answering any questions you may have during this Board.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ is available for download or on CD via Bandcamp — also see here). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ is available for download or on CD via Bandcamp — also see here). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

May 29, 2016

Obama Officials Confirm That Nearly 24 Guantánamo Prisoners Will Be Freed By the End of July

I wrote the following article for the “Close Guantánamo” website, which I established in January 2012, on the 10th anniversary of the opening of Guantánamo, with the US attorney Tom Wilner. Please join us — just an email address is required to be counted amongst those opposed to the ongoing existence of Guantánamo, and to receive updates of our activities by email.

I wrote the following article for the “Close Guantánamo” website, which I established in January 2012, on the 10th anniversary of the opening of Guantánamo, with the US attorney Tom Wilner. Please join us — just an email address is required to be counted amongst those opposed to the ongoing existence of Guantánamo, and to receive updates of our activities by email.

Last week there was confirmation that the Obama administration is still intent on working towards the closure of the prison at Guantánamo Bay before President Obama leaves office, when officials told Spencer Ackerman of the Guardian that there is an “expectation” within the administration that 22 or 23 prisoners will be released by the end of July “to about half a dozen countries.”

80 men are currently held, so the release of these men will reduce the prison’s population to 57 or 58 prisoners, the lowest it has been since the first few weeks of its existence back in 2002.

As the Guardian explained, however, the officials who informed them about the planned releases spoke on condition of anonymity, because “not all of the foreign destination countries are ready to be identified.” In addition, “some of the transfer approvals have yet to receive certification by Ashton Carter, the defense secretary, as required by law, ahead of a notification to Congress.”

The releases will largely fulfill a promise made in January by Lee Wolosky, the State Department’s envoy for the closure of Guantánamo, who said at the time that the government would release all the prisoners approved for release “by this summer.”

Currently, 28 of the remaining 80 prisoners have been approved for release – 15 by the high-level, inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force that President Obama appointed shortly after taking office in January 2009, and 13 by Periodic Review Boards, another high-level process, established in 2013 to review the cases of all the prisoners not already approved for release by the task force, or facing trials (and just ten men are in this latter category).

The remaining 42 men are all eligible for Periodic Review Boards, which the administration has promised to complete before Obama leaves office. 35 are awaiting their reviews, or the results of their reviews, while just seven men have had their ongoing imprisonment approved by the boards.

Since they began in November 2013, the PRBs – which are akin to parole boards — have approved a total of 22 men for release. This is a success rate for the prisoners of 76%, and demonstrates that the task force was severely mistaken when, in 2010, it described 46 of the men who were later made eligible for PRBs as “too dangerous to release,” while acknowledging that insufficient evidence existed to put them on trial — meaning that the so-called evidence was profoundly unreliable, largely produced through interrogations involving torture or other forms of abuse, or through prisoners being bribed with better living conditions.

18 other men were recommended for military commission trials by the task force, but they too were added to the list of prisoners eligible for PRBs when the basis for prosecutions largely collapsed in 2012-13, after appeals court judges dismissed some of the few convictions secured in the much-criticized trial system, correctly ruling that the war crimes for which the men had been convicted – primarily, providing material support for terrorism and conspiracy – had been invented as war crimes by Congress.

It is impossible to estimate how many of the remaining PRBs will end with prisoners being approved for release, but it would seem reasonable to suggest that perhaps another 20 or so men will be recommended for release, leaving somewhere between 30 and 35 prisoners as what, in Spencer Ackerman’s words, “administration officials tend to call an ‘irreducible minimum.’”

Finally closing the prison, however, as President Obama promised when he first took office seven years and four months ago, remains elusive, because of a Congressional ban, included in the annual National Defense Authorization Act every year since 2011, on bringing prisoners to the US mainland for any reason. As Spencer Ackerman described it, the ban “has made the parole-and-transfer process the likeliest mechanism through which Obama can come close to accomplishing his long-thwarted goal of closing down Guantánamo.”

For next year’s NDAA, as I reported recently, the Senate Armed Services Committee has proposed that some prisoners should be able to make federal court plea deals and be imprisoned in other countries, and that seriously ill prisoners should be allowed to visit the US mainland for operations, but it remains to be seen if the proposals will be passed.

Already, however, the House of Representatives, which passed its version of the bill on May 18, restricts the release of prisoners like never before by, as the Guardian described it, “preventing the administration from transferring any detainee to a country subject to a state department travel warning — based on a standard far lower than a risk of terrorism or insurgency.” That list, as the Guardian noted, “currently includes all of Europe.”

As the Guardian also explained, “The White House has threatened to veto the defense bill, citing the Guantánamo provisions, among other reasons. Yet such veto threats have become an annual ritual. Every defense bill since 2011 that Obama ultimately signed included Guantánamo detainee restrictions.”

As a result, it may be that an executive order is the only route through which President Obama can fulfill his promise before he leaves office, or it may be that, after eight years, the president will have to admit defeat and hand over the prison’s closure to his successor – if that successor is a similar-minded Democrat, and not one of the Republican challengers who all seems to be in favor of keeping Guantánamo open, although that tough talk may, of course, change if they actually get elected and have to face sustained criticism, as happened with President Bush in his second term.

And even if President Obama – or his successor – succeeds in bringing several dozen prisoners to the US mainland, there will then be legal challenges if men continue to be held without charge or trial, because of the long-standing failure of the US to treat men seized in wartime since 9/11 according to the Geneva Conventions, and because, we believe, if they are not put on trial they will have new opportunities to challenge the basis of their detention under the US Constitution, which does not endorse indefinite detention without charge or trial, however much government officials pretend that there is such a thing as an “irreducible minimum” of prisoners who can continue to be held without either being given a trial or formally held until the end of hostilities.

First, though, let us hope that these 22 or 23 men are released within the next two months, and that steps continue to be taken to reduce the population of Guantánamo as much as possible.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ is available for download or on CD via Bandcamp — also see here). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ is available for download or on CD via Bandcamp — also see here). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

May 26, 2016

Alleged Al-Qaida Bomb-Maker Faces Periodic Review Board at Guantánamo

Last Thursday, Jabran al-Qahtani, a Saudi national, became the 39th prisoner to face a Periodic Review Board at Guantánamo.

Last Thursday, Jabran al-Qahtani, a Saudi national, became the 39th prisoner to face a Periodic Review Board at Guantánamo.

Set up in 2013 to review the cases of all the prisoners who were not facing trials (just ten men) or the rather larger group of men who had already been approved for release by the high-level inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force that President Obama established shortly after taking office in 2009, the PRBs involve representatives of the Departments of State, Defense, Justice and Homeland Security, as well as the office of the Director of National Intelligence and the Office of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and, since January 2014, they have approved 22 men for release and have defended the ongoing imprisonment of just seven men, a success rate for the prisoners of 76%.

The results are a damning verdict on the task force’s decision to describe 46 men facing PRBs as “too dangerous to release,” even though the task force members also acknowledged that insufficient evidence existed to put them on trial; in other words, it was not evidence, but unreliable information extracted from prisoners at Guantánamo and elsewhere in the “war on terror” — including the CIA’s “black sites” — through the use of torture, other forms of abuse or bribery (with better living conditions, for example). It has also become apparent that another reason some prisoners were described as “too dangerous to release” was because the authorities regarded them as having a threatening attitude towards the US, even though it is, to my mind, understandable that some men confronted with long years of abusive and generally lawless detention might react with anti-social behavior and threats.

The PRBs are also reviewing the cases of 18 men recommended for prosecution by the task force until the basis for prosecutions largely collapsed in 2012-13, when appeals court judges in Washington, D.C. — in what was generally considered a predominantly conservative court — threw out some of the few convictions secured in Guantánamo’s military commissions, on the rather embarrassing basis that the war crimes for which the men had been convicted — primarily, providing material support for terrorism and conspiracy — had been invented by Congress.

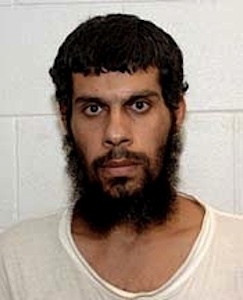

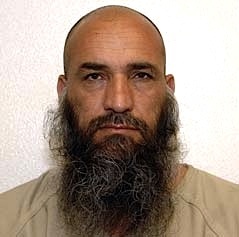

Jabran al-Qahtani, a graduate in electrical engineering from King Saud University in Saudi Arabia, is one of the prisoners who had initially been recommended for prosecution, under George W. Bush. In June 2008, he was put forward for a trial by military commission with two other men facing PRBs — Ghassan al-Sharbi (who has no date yet set for his PRB) and Sufyian Barhoumi, whose PRB took place on May 26, and which I’Il be writing about next week — and Noor Uthman Muhammed, a Sudanese prisoner who accepted a plea deal in his military commissions trial and was sent home in December 2013.

These three — and a handful of other men — were seized in a house raid in Faisalabad, Pakistan on March 28, 2002, at which Abu Zubaydah was also seized. The first victim of the CIA’s torture program, Abu Zubaydah was initially and mistakenly regarded as a significant member of Al-Qaeda, and was subjected to horrendous torture, even though it eventually became apparent that he was not a member of Al-Qaeda at all and had, instead, been the gatekeeper for an independent training camp that was not aligned with Al-Qaeda.

As a result, it may well be that there is little basis for the US’s historical claims that the men seized in Abu Zubaydah’s house were actively involved with terrorism, as the house may, primarily, have been functioning as part of a network of houses used for moving people — civilians and soldiers — out of Afghanistan, after the US-led invasion.

When al-Qahtani was charged, I wrote the following about him:

[He has] had little to say about the allegations against him: that he traveled to Afghanistan after 9/11 “with the intent to fight the Northern Alliance and the American forces, whom he expected would soon be fighting in Afghanistan,” and that he was part of a group at Abu Zubaydah’s house who were provided with money to buy the components to make remote-controlled explosive devices. He refused to take part in his tribunal at Guantánamo in 2004, and spoke very little in April 2006, during the pre-trial hearing for his first, aborted Military Commission, when he was concerned only to refuse the services of his military lawyer.

As with the other three men, the charges against him were dropped in October 2008. New charges were filed in January 2009, but were once again dismissed in January 2013, and it was just a few months later that the Periodic Review Boards were set up.

In its unclassified summary of al-Qahtani’s case for his PRB, the US authorities described him as “a self-radicalized electrical engineer who traveled from Saudi Arabia to Afghanistan in October 2001 to fight against US forces in Afghanistan.” It was also noted that he “received abbreviated weapons training at an al-Qa’ida camp in Afghanistan,” and the emphasis must surely be on “abbreviated,” because, post-9/11, all the camps closed following the US-led invasion on October 6, 2011 – and the summary continued by suggesting that he was then “selected by a senior al-Qa’ida military commander to receive explosives detonator training in Faisalabad, Pakistan,” where “he learned to construct circuit boards for radio-remote controlled improvised explosive devices with the intention of teaching bomb making techniques to operatives attacking US and Coalition forces in Afghanistan.”

It was also noted that he was “captured by Pakistani authorities,” just “five months after leaving Saudi Arabia,” at the safehouse of Abu Zubaydah, who was described, mistakenly, as a “senior al-Qa’ida facilitator.”

Turning to Guantánamo, it was noted that al-Qahtani “has been mostly compliant with guard force personnel” at the prison, “but has not cooperated with interrogators.” It was also noted that, “[e]arly in his detention, he expressed his support for the Taliban and repeatedly stated that he intended to rejoin the extremist fight against the US and its allies,” according to Joint Task Force-Guantánamo (JTF-GTMO) in a report in January 2009, but that he “has not been forthright about his expertise in electronics or his time in Afghanistan, and made conflicting statements about the extent of his affiliation with al-Qa’ida before discontinuing his participation with interrogators in late 2002.”

The authorities also noted that his electrical engineering degree “could provide him with credentials for employment if he is released,’ but that “[h]is education and training also make [him] a skilled bomb maker, however, whose electronics expertise would be in high demand by terrorist organizations.” The authorities assessed that, if he were to return to Saudi Arabia, he could “seek out prior associates who could provide him a path to reengage in hostilities and extremism, if he chose to do so,” although it seems unlikely that the Saudi authorities will not be very closely monitoring all released prisoners.

Below I’m posting the opening statements made by al-Qahtani’s personal representative, a member of the military appointed to help him prepare for his PRB, and an extensive submission by his civilian attorney, Judson Lobdell (of the San Francisco branch of Morrison & Foerster LLP), who stressed in particuar how al-Qahtani regretted his actions of 14-15 years ago, describing how he “has come to deeply regret what he did while he was young, ignorant, and swept away by a movement he did not understand.”

Prisoners expressing remorse is an important part of the review board’s deliberations, which are akin to parole boards, but it remains to be seen whether the review board members will accept the scale of his regret, when set against the authorities’ concerns about his perceived lack of forthrightness “about his expertise in electronics or his time in Afghanistan,” and his “conflicting statements about the extent of his affiliation with al-Qa’ida.”

Periodic Review Board Initial Hearing, 19 May 2016

Jabran Al Qahtani, ISN 696

Personal Representative Opening Statement

Good morning, ladies and gentlemen of the Board. I am the Personal Representative for ISN 696, Mr. Jabran Saad al Qahtani. I will be assisting Mr. Qahtani with his case this morning, along with the assistance of his Private Counsel.

Jabran has been overjoyed and eager to participate in the Periodic Review process since I first met with him in mid-April 2016. He has maintained his positive attitude throughout all of our meetings and has always been gracious and respectful towards me.

Mr. Qahtani has expressed his desire to return home to reunite with his family. However, he is open to transfer to any country, but would prefer an Arabic-speaking country, if possible. He is willing to participate in any rehabilitation or reintegration program as well. He looks forward to life after his transfer from Guantánamo Bay and reconnecting with his large family. As the youngest son of his parents, he hopes that at some point his many sisters and brothers could visit him and he could get to know the youngest members of his close-knit family who were born during his detention.

Jabran has been a compliant detainee with a relatively low number of infractions since his arrival at Guantánamo Bay and has taken advantage of the communal living opportunity here at the detention facility. He earned an electrical engineering degree from King Saud University and comes from a large close-knit family of educators, government workers, and small business owners. Additionally, over the past 14 years, Jabran has attended art, computer skills, and English courses offered at the camp. By being exposed to so many people of various cultural and religious backgrounds here at GTMO, Jabran has had many opportunities to better understand and appreciate their beliefs and customs. These adaptive skills, along with his formal education in Saudi Arabia and coursework completed at Guantánamo Bay, will serve him well wherever he is transferred.

I am confident that Jabran’s desire to pursue a better way of life if transferred from Guantánamo Bay is genuine and that he bears no ill will towards anyone. I remain convinced that Jabran does not pose a significant threat to security of the United States or any of its allies.

Thank you for your time and attention and I look forward to answering any questions you may have during this Board.

Statement of Mr. Judson Lobdell

Written Submission in Support of Jabran Said Wazar al Qahtani (ISN 696)

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

This submission is to support the release of Jabran Said Wazar al Qahtani (ISN 696). Mr. al Qahtani has been confined at Guantánamo Bay for the past fifteen years as a result of actions that he took when he was twenty four years old. He is now thirty nine and has come to deeply regret what he did while he was young, ignorant, and swept away by a movement he did not understand.

Mr. al Qahtani realizes that he cannot recapture the years he lost or the other consequences of his actions. But he is committed to starting his life afresh, focusing on what he has come over time to recognize are most important to him: building a family and contributing to his community through work and service.

MR. AL QAHTANI POSES NO THREAT TO THE SECURITY OF THE UNITED STATES

The Background to Mr. al Qahtani’s Actions

Jabran Said Wazar al Qahtani is the eighth child of Sa’id Wazur al Qahtani. He has 13 brothers and eight sisters. His father built a successful real estate business in Riyadh.

As a boy, Mr. al Qahtani was raised in a family where an education was highly prized. Math, science, and engineering came naturally to many of Mr. al Qahtani’s older brothers, who achieved early success. Two of Mr. al Qahtani’s brothers are chemical engineers, one is an electrical engineer, one is a petroleum engineer, one is a computer scientist, and two are college professors. None of his siblings has had any involvement in extremist movements.

Mr. al Qahtani greatly admired the success and achievement of his father and his older brothers. Although studies did not come as easily to him as some his older brothers, Mr. al Qahtani was able, through long hours of study as a boy and a young man, to earn an electrical engineering degree specializing in high voltage from King Saud University in Riyadh. This led him to accept a position at the Saudi Arabian Electric Company in Riyadh. Around that time, Mr. al Qahtani met Nawal. They married and began to plan a family of their own.

In 2001, however, Mr. al Qahtani got caught up in a wave of enthusiasm for defending Islam against what he heard described as a “crusade” by the United States and its allies. His understanding of battle at that time came from story books. He had no training or experience with combat or military affairs.

In what he has come to recognize as the greatest mistake of his young life, Mr. al Qahtani left Saudi Arabia for Afghanistan in 2001 and, after a series of misadventures, ended up in a training camp north of Kabul. The camp lasted for ten days. While it included weapons instruction, most of that consisted of classroom lectures. He spent much of his time digging a bunker and ducking fire from the Northern Alliance. He never fired a shot in anger.

After the ten days were over, Mr. al Qahtani retreated into hiding for approximately twenty days. He ended up in a safe house in Faisalabad, where he was captured by Pakistani soldiers. Plans to exploit Mr. al Qahtani’s knowledge of engineering by training him to train others on the making of triggering devices came to nothing. Nobody was ever harmed by a device made directly or indirectly by Mr. al Qahtani.

Mr. al Qahtani was the furthest thing from a hardened Mujahadeen. In the words of one of those captured with Mr. al Qahtani in Faisalibad: “His background and actions weren’t that of a fundamentalist. He liked to joke, have fun.”

Mr. al Qahtani’s attempts to puff himself up as tough and dangerous following his capture — for example, calling himself a “terrorist” — were nothing more than a misguided attempt to fit into the extreme society of his fellow Guantánamo Bay detainees.

Mr. al Qahtani’s Family are Committed to Supporting His Plans to Start a Family and Live a Quiet Life

Mr. al Qahtani comes from a well-respected Saudi Arabian family that, despite his mistakes, is willing to support his reintegration into modern society.

None of Mr. al Qahtani’s brothers is involved in extremist activities. They were all dismayed by Mr. al Qahtani’s actions and would have tried to stop him had they known his intentions in 2001-2002.

Mr. al Qahtani’s family statements, enclosed with this submission, evince a loving family ready to support Mr. al Qahtani:

Mr. al Qahtani’s brother has collected letters from all available members of his family. He says that Mr. al Qahtani’s release would return the “smile and happiness” to every member of his family.

His other brother hopes that Mr. al Qahtani’s life is stabilized “with marriage, suitable work, and [a] house to be a productive individual serving his home and his society.”

His brother-in-law says that his entire family was shocked when he left home but hopes that the Board gives Mr. al Qahtani an opportunity to join his family once again.

Another brother describes him as, among many other things, “gregarious,” “humorous,” “moderate,” “patient,” and “loved by others.”

Another brother says that Mr. al Qahtani’ s leaving home was “terrible” and that he hopes to help Mr. al Qahtani “proceed his life which will be the new better beginning to him.”

An additional brother remarks fondly on how Mr. al Qahtani taught his younger siblings school lessons and hopes that his family can help Mr. al Qahtani start a family of his own soon.

His sisters and his father’s second wife express excitement for his release and note that his family plans to help provide him a home and financial support upon his release.

Mr. al Qahtani plans to reintegrate into society by finding a wife, a job, and starting a family. These are not the plans of a potential recidivist, but rather the plans of a man ready to live the rest of his life quietly.

Mr. al Qahtani’s Behavior in Custody has Improved

The statements from Mr. al Qahtani’s fellow inmates and teachers reflect the maturing of his character. Mr. al Qahtani has taken a number of classes at Guantánamo, including English, life skills, and Photoshop courses, and his instructors in those courses speak highly of his studious nature and willingness to work with others. Similarly, while Mr. al Qahtani was formerly stand-offish at Guantánamo, he has slowly opened up to other inmates and has become social once again. Their statements evince his development while in Guantánamo Bay and his readiness to reintegrate into modem society.

THE BOARD SHOULD RELEASE MR. AL QAHTANI

Mr. al Qahtani poses no threat to the security of the United States. He deeply regrets his decision to leave home in 2002 and realizes that it was based on an immature, storybook notion of the world that has no basis in reality.

Mr. al Qahtani’s training as an electrical engineer should not stand in the way of his release. Mr. al Qahtani is not a bomb-maker. Indeed, he has never been alleged to have been a bomb-maker, only a young man who, because of his education, was picked out to receive training in that area. There is no reason to believe that formal electrical engineering training Mr. al Qahtani received twenty years ago would provide him with relevant specialized knowledge of bomb-making.

Regardless, Mr. al Qahtani has absolutely no desire to be a bomb maker. He wishes to live a quiet life, raise a family, get a job, and earn respect in his community.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ is available for download or on CD via Bandcamp — also see here). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ is available for download or on CD via Bandcamp — also see here). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

May 24, 2016

Periodic Review Board at Guantánamo for Yemeni Subjected to Long-Term Sleep Deprivation in Prison’s Early Years

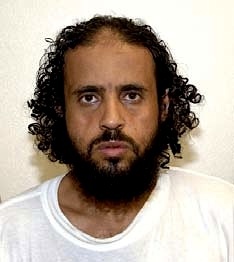

Last Tuesday, Mohammad Rajah Sadiq Abu Ghanim (aka Mohammed Ghanim), a Yemeni born in 1975, became the 38th prisoner to face a Periodic Review Board at Guantánamo. These involve representatives of the Departments of State, Defense, Justice and Homeland Security, as well as the office of the Director of National Intelligence and the Office of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and were set up in 2013 to review the cases of all the prisoners who had not already been approved for release by the high-level inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force that President Obama established shortly after taking office in 2009, or were not facing trials. Just ten men are in this latter category.

Last Tuesday, Mohammad Rajah Sadiq Abu Ghanim (aka Mohammed Ghanim), a Yemeni born in 1975, became the 38th prisoner to face a Periodic Review Board at Guantánamo. These involve representatives of the Departments of State, Defense, Justice and Homeland Security, as well as the office of the Director of National Intelligence and the Office of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and were set up in 2013 to review the cases of all the prisoners who had not already been approved for release by the high-level inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force that President Obama established shortly after taking office in 2009, or were not facing trials. Just ten men are in this latter category.

Those eligible for the PRBs were 46 men described as “too dangerous to release” by the task force, which also, however, acknowledged that insufficient evidence existed to put them on trial; in other words, that is was not evidence, but unsubstantiated claims made by prisoners subjected to torture, abuse or bribery (with better living conditions), or that they were regarded as having dangerously anti-American attitudes (despite the fact that their appalling treatment may have inspired such sentiments).

18 others had been recommended for trial by the task force, until the basis for prosecutions largely collapsed when appeal court judges overturned some of the handful of convictions secured in the military commission trial system, pointing out that the war crimes for which the men had been convicted had actually been invented by Congress.

Mohammad Abu Ghanim is one of the men initially described as “too dangerous to release,” and will be hoping to join the 20 others in that category who have been recommended for release by PRBs. Two men originally recommended for prosecution have also been recommended for release, while just seven men have so far had their ongoing imprisonment upheld. This is a 76% success rate for the prisoners, and a rather damning indictment of the scaremongering involved in the task force describing men as “too dangerous to release,” when that has now been disproved on 20 separate occasions.

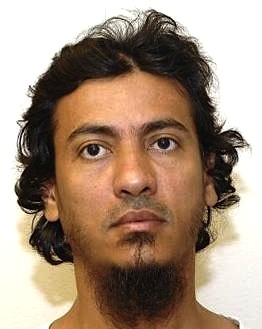

In a profile of Mohammad Ghanim in September 2010, I noted, “In Guantánamo, Ghanim was accused of having ‘participated in jihad activities’ in Bosnia and of taking part in the Yemeni civil war, and of being a bodyguard for Osama bin Laden. In response, he has apparently stated that he fought only with the Taliban.”

The bin Laden bodyguard allegation is unreliable, in part because, even though it was made by a number of high-profile prisoners, they were all subjected to torture, and in part because, although Ghanim is one of 30 men seized in December 2001 crossing from Afghanistan to Pakistan, who were all described as bin Laden bodyguards and known as “the Dirty Thirty,” most of them were young Yemenis, who had not been in Afghanistan for long, and would not have been trusted with such important positions.

I also described the torture and abuse to which Ghanim had been subjected in Guantánamo:

In a report from a former prisoner published by Cageprisoners, it was stated that Ghanim was subjected to prolonged sleep deprivation in Guantánamo, as part of what was euphemistically termed “the frequent flier program,” and was also denied medical treatment: “Every two hours he would get moved from cell to cell, 24 hours a day, seven days a week, sometimes cell to cell, sometimes block to block, over a period of eight months. He was deprived of sleep because of this and he was also deprived of medical attention. He had lost a lot of weight. He had a painful medical problem, haemorrhoids, and that treatment was refused unless he cooperated. He said he would cooperate and had an operation. However, the operation was not performed correctly and he still had problems. He would not cooperate. [H]e was [then] put in Romeo Block where the prisoners would be made to stand naked. It was then left to the discretion of the interrogators whether a prisoner was allowed clothes or not.”

The US authorities’ unclassified summary for Ghanim’s PRB repeats the claims — first made publicly available in 2011 by WikiLeaks, when the formerly classified military files on the prisoners were released, after they were passed to WikiLeaks by Pfc. Bradley Manning — that he “is an experienced militant who probably acted as a guard for Usama Bin Ladin in Afghanistan,” adding, “He forged relationships with future al-Qa’ida members while fighting for jihadist causes during the 1990s and probably participated in plots against government and Western interests in Saudi Arabia and Yemen. He also associated with several USS Cole plotters and probably left Yemen for Afghanistan around the time of the bombing in October 2000, although we have no evidence that he had a role in the operation.”

Some of these allegations — about his connections with terrorists in Yemen — seem more troubling, although the claim that he was “fighting for jihadist causes during the 1990s” is clearly exaggerated. As the 1990s began, Ghanim was 15 years old, and there seems to be no basis for suggesting that he did anything more than visit Bosnia in 1994, when he was 19, leaving the year after when the Dayton Peace Accords were signed.

As well as repeating the bin Laden bodyguard allegation, the authorities also noted that, in Afghanistan, “he fought for the Taliban against the Northern Alliance, worked for an al-Qa’ida-associated charity, [and] possibly trained to become an al-Qa’ida instructor,” although it is not possible to discern how much truth there is to these additional allegations.

In Guantánamo, the authorities stated, he “has committed an average number of infractions compared to other detainees,” but “has improved his behavior since mid-2013, probably because he wanted to improve his chances for transfer.” The authorities also noted, “The majority of his infractions have been non-violent and relatively minor; however, he has also participated in mass disturbances and non-violent demonstrations in response to quality of life issues or perceived injustices committed by the guard force.”

It was also noted that Ghanim “has demonstrated varying levels of cooperation during his interviews, and his cooperation has improved when he felt that the debriefer has treated him with respect,” which is surely a vindication of rapport-building rather than abuse as a way to secure reliable information.

The authorities also stated, “He has been reluctant to discuss other detainees, except to report on their impending hunger strikes or possible uprisings” — which is generally a sign of a strong-willed prisoner, who has managed not to get drawn into making false allegations against his fellow prisoners — and added that he “appears to have some influence among other detainees and has served as an intermediary between some detainees, which may have helped raise his status in prison.”

In conclusion, the summary noted that Ghanim “has avoided explicitly aligning himself with violent extremism,” attributing this to him “probably judging that this may improve his chances for transfer.” It was also that he “has expressed hatred towards the United States on occasion,” although it was acknowledged — for the first time, I think — that this was “probably out of frustration with his detention and debriefers’ line of questioning.”

It was also noted that a former prisoner with whom he has corresponded “is suspected of reengaging in terrorism,” and that “several of his family members and childhood friends associate with AQAP [Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula] members who could facilitate [his] introduction to the group or other extremist activity if he chose to reengage.” On the former point, I find it unfair that correspondence with a former prisoner “suspected of reengaging in terrorism” is regarded as a sign of sympathy with anti-US sentiment, when it is unclear that any such sympathy exists. In addition, the latter point is largely irrelevant, as, if he were to be approved for release, he would not be repatriated. This is because the entire US establishment is unwilling to repatriate any Yemenis, and third countries must be found that are prepared to offer them new homes.

Below I’m posting the opening statement made by Ghanem’s personal representatives (military personnel appointed to help them prepare for their PRBs), in which they explained that he “fosters no ill-will toward the United States and is no longer a threat to America,” and also referred to his compliant behaviour at Guantánamo. No opening statement was provided by an attorney, and it remains to be seen if Ghanim himself not only demonstrated compliance at Guantánamo, but also remorse for his previous actions, which seems very much to be what the boards — whose closest analogy is a parole board — seem to be looking out for in particular.

Periodic Review Board Initial Hearing, 17 May 2016

Mohammad Rajab Sadiq Abu Ghanim, ISN 044

Personal Representative Opening Statement

Good morning, ladies and gentlemen of the Board. As Mohammad Rajah Sadiq Abu Ghanim, ISN 044, Personal Representatives, we would like to thank the Board for allowing us the opportunity to present Mohammad’s case and reveal how he is no longer a continuing significant threat to the United States.

From day one, Mohammad has actively participated in every meeting that we scheduled with him. He was always eager to provide any information that was asked of him, as well as provide any clarity to any situation that was not fathomable to us. During our meetings, Mohammad has expressed his desire to return home and to reunite with his family. He is aware that he may not be going back to Yemen, but he is willing to settle wherever the board determines for him. He is enthusiastically looking forward to the opportunity to have a wife and children of his own someday.

Since his detention in Guantanamo, Mohammad has been respectful to the guard force, and he has diligently tried to keep his fellow detainees from harming themselves and each other. He has been a compliant detainee and has taken advantage of the many opportunities presented to him to learn about American culture. He likes to read books written by American authors as well as watching several American television shows. He has become a person who is considerate and tolerant of others. Additionally, his time here has given him the opportunity to meet Americans and be exposed to American values and culture. This has given him an appreciation of the good things that America and Americans can accomplish.

Mohammad fosters no ill-will toward the United States and is no longer a threat to America; he is ready to answer any questions the Board may have for him at this time.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ is available for download or on CD via Bandcamp — also see here). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album, ‘Love and War,’ is available for download or on CD via Bandcamp — also see here). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

May 22, 2016

Insignificant Afghan Finally Approved for Release from Guantánamo

Good news from Guantánamo, as another prisoner, Obaidullah, an Afghan, is approved for release by a Periodic Review Board. Decisions have now been taken in the cases of 29 prisoners, with 22 recommended for release, and just seven recommended for ongoing imprisonment. This is a success rate for the prisoners of 76%, which is hugely significant, because, back in 2010, they were either recommended for prosecution or were described as “too dangerous to release” by the Guantánamo Review Task Force, which President Obama established, shortly after taking office in 2009, to review the cases of all the prisoners held when he became president. 18 men were in the former category, and 46 in the latter.

Good news from Guantánamo, as another prisoner, Obaidullah, an Afghan, is approved for release by a Periodic Review Board. Decisions have now been taken in the cases of 29 prisoners, with 22 recommended for release, and just seven recommended for ongoing imprisonment. This is a success rate for the prisoners of 76%, which is hugely significant, because, back in 2010, they were either recommended for prosecution or were described as “too dangerous to release” by the Guantánamo Review Task Force, which President Obama established, shortly after taking office in 2009, to review the cases of all the prisoners held when he became president. 18 men were in the former category, and 46 in the latter.

The decision also means that, of the 80 men still held, 28 have been approved for release — 15 by the task force in 2010, and 13 by the PRBs (nine of those approved for release by PRBs have already been freed). 35 others are awaiting PRBs, or are awaiting decisions, and just ten men are facing trials — or have already had trials.

Obaidullah, who was just 19 years old when he was seized at his home in Afghanistan in July 2002, is one of the prisoners who had initially been recommended for prosecution — and is the second former prosecution candidate to be recommended for release by a PRB (three others have been recommended for ongoing imprisonment). He had been put forward for a trial by military commission in September 2008, charged with providing material support for terrorism and conspiracy, based on claims that he “stored and concealed anti-tank mines, other explosive devices, and related equipment”; that he “concealed on his person a notebook describing how to wire and detonate explosive devices”; and that he “knew or intended” that his “material support and resources were to be used in preparation for and in carrying out a terrorist attack.”

At the time, I described these allegations as “the thinnest set of allegations to date” in the commissions, in an article entitled, “Guantánamo trials: another insignificant Afghan charged,” in which I also mentioned how Obaidullah had spoken, in an earlier review at Guantánamo, of his torture by US forces in Afghanistan — how, in Khost, US soldiers “put a knife to my throat and said if you don’t tell us the truth and you lie to us we are going to slaughter you,” how they “tied my hands and put a heavy bag of sand on my hands and made me walk all night in the Khost airport,” and how, In Bagram, “they gave me more trouble and would not let me sleep. They were standing me on the wall and my hands were hanging above my head. There were a lot of things they made me say.”

As I also pointed out, when Charlie Savage of the New York Times wrote about Lt. Cmdr. Pandis’s investigation back in 2012, he noted, “It is an accident of timing that Mr. Obaidullah is at Guantánamo. One American official who was formerly involved in decisions about Afghanistan detainees said that such a ‘run of the mill’ suspect would not have been moved to Cuba had he been captured a few years later; he probably would have been turned over to the Afghan justice system, or released if village elders took responsibility for him.” The last Afghans transferred to the general population in Guantánamo were sent in November 2003, and it is certainly true to note that the majority of alleged Afghan insurgents seized and held at Bagram from December 2003 onwards were returned to their families many years ago.

It is also worth noting, I believe, that, when Obaidullah was first charged, I wrote, “It doesn’t take much reflection on these charges to realize that it is a depressingly clear example of the US administration’s disturbing, post-9/11 redefinition of ‘war crimes,’ which apparently allows the US authorities to claim that they can equate minor acts of insurgency committed by a citizen of an occupied nation with terrorism.”

In October 2010, Obaidullah also had his habeas corpus petition ruled on by a US judge, who turned it down, but, as the Associated Press noted this week, “The government dismissed the [military commission] charges in 2011 and his lawyers have been pressing for his release ever since.” This was even before the charges in the military commissions were largely discredited, when, in 2012 and 2013, appeals court judges ruled that providing material support for terrorism and conspiracy were not war crimes triable by a military commission.