Andy Worthington's Blog, page 69

September 9, 2016

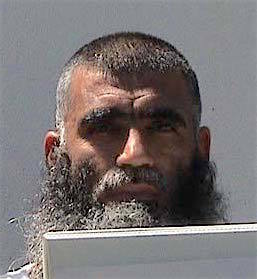

Afghan Moneychanger Seeks Release from Guantánamo Via Periodic Review Board

On August 25, an Afghan prisoner at Guantánamo, Haji Wali Mohammed, who was born in February 1965 or 1966, became the 62nd prisoner to face a Periodic Review Board. The PRBs — whose closest analogy are parole boards — were set up in 2013 to review the cases of all the prisoners who had not already been approved for release and were not facing trials, and in total 64 men have had their cases reviewed. The last two reviews took place on September 1 and September 8, and I’ll be writing about them very soon.

On August 25, an Afghan prisoner at Guantánamo, Haji Wali Mohammed, who was born in February 1965 or 1966, became the 62nd prisoner to face a Periodic Review Board. The PRBs — whose closest analogy are parole boards — were set up in 2013 to review the cases of all the prisoners who had not already been approved for release and were not facing trials, and in total 64 men have had their cases reviewed. The last two reviews took place on September 1 and September 8, and I’ll be writing about them very soon.

Of the 64, 12 decisions have yet to be taken, but of the 52 cases decided (see my definitive PRB list here), the board members — comprising representatives of the Departments of State, Defense, Justice and Homeland Security, as well as the office of the Director of National Intelligence and the Office of the Joint Chiefs of Staff — approved 33 men for release, while upholding the ongoing imprisonment of 19 others. That’s a success rate for the prisoners of 63%, which is a rather damning indictment of the caution exercised by the previous review board, the Guantánamo Review Task Force, which reviewed all the prisoners’ cases in 2009, and made the recommendations for the ongoing imprisonment of the 64 men who have ended up facing PRBs.

23 of the 64 had been recommended for prosecution by the task force, until the basis for prosecutions in Guantánamo’s military commissions largely collapsed as a result of a number of devastating appeals court rulings in Washington, D.C., in which judges dismissed some of the handful of convictions secured in the commissions, and concluded that the war crimes in question had been invented by Congress.

The 41 others were recommended for ongoing imprisonment by the task force, on the basis that they were too dangerous to release, even though the task force also admitted that insufficient evidence existed to put them on trial; in others words, the supposed evidence used to justify their ongoing imprisonment was dubious, to say the least, consisting, in large part, of untrustworthy statements extracted from the prisoners themselves, or from their fellow prisoners, when the use of torture and other forms of abuse — as well as bribery (with better living conditions) — were widespread.

Haji Wali Mohammed was one of the 41, even though, as I recognized when researching his story ten years ago, there was no good reason for suspecting that his story indicated that he bore any malice towards the US. A moneychanger, he had lost a large amount of money in a deal, and had been blamed by the Taliban. Quite how this made him any sort of enemy of the US was beyond me.

As I explained in The Guantánamo Files:

Mohammed, a 35-year old money exchanger, was captured at his home in Peshawar, on 24 January 2002. Married with two wives and ten children, he was born in Afghanistan, but his family fled to Pakistan in 1978 and lived in refugee camps for the next ten years until he established himself as a successful moneychanger and moved to Peshawar in 1988. All was well until 1995, when he first lost a significant amount of money, and in 1998, after entering into a business deal with the Bank of Afghanistan that also failed, he ended up being blamed by the Taliban, who made him responsible for the whole debt — around one million dollars — even though he only had a 25 percent stake in the deal.

He explained to his tribunal that the ISI took his car in November 2001 and then returned in January, because they knew he was “a very famous money exchanger” and assumed that he would pay them a bribe of at least $100,000. When he said that he actually owed a lot of money to other people and was unable to pay, he was told, “If you don’t have a car and you don’t have the cash, sell your house and give us half of it to save you from the bad ending.”

Three days later, he was handed over to the Americans, purportedly as a drug smuggler, although his new captors soon decided that he bought surface-to-air missiles for Osama bin Laden and — despite his abysmal financial record since 1995 — was entrusted with a million dollars by Mullah Omar. Explaining that he did not know bin Laden and had no time for the Taliban, who had ruined his life, he said, “We were businessmen, their ways and our ways were different. That’s why they didn’t like us and we didn’t like them. Because a businessman does not have a beard and listens to music in his car, and he watches television and they didn’t like that.”

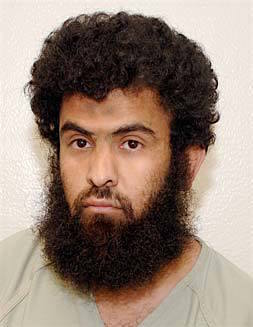

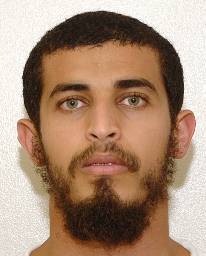

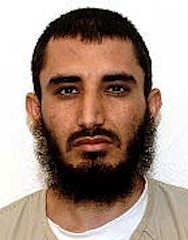

Describing his appearance at his PRB, Courthouse News, in an article entitled, “Gitmo Parole Hearing Goes Well for Afghan,” reported that he “wore a white, short-sleeved tunic,” and his “hair was cut short, especially on the sides of his head. His beard appeared long and full, though, graying as it neared his chest.” Courthouse News added that “[a] closed-circuit feed at the Pentagon of the hearing in Cuba showed Mohammad glancing down at papers on the table in front of him while an unnamed government representative read his detainee profile.”

At his PRB, the US authorities seemed to recognize that Mohammed might not have been the bigshot they had spent years pretending he was.

In the unclassified summary for his PRB, the US authorities described Haji Wali Mohammad as “an Afghan money changer who operated a currency exchange business and conducted financial transactions from the mid-to-late 1990s for senior Taliban officials before he fell out of favor with the group.” It was also noted that he “reportedly had ties to other extremist organizations, such as Hezb-e lslami, and may have made some transactions related to the narcotics trade.”

Those compiling the summary also noted that the authorities “assess with moderate confidence” that Mohammed “conducted financial transactions for Usama Bin Ladin [sic] in 1998 and 1999, either directly or through his ties to the Taliban, and was probably motivated by financial gain.” That latter point seems certainly to be true — and was confirmed by his attorney and his personal representative (a military officer appointed to help him prepare for his PRB), whose initial statements are posted below. However, it is worth noting that the connection with Osama bin Laden has not been confirmed.

Not only was it called into doubt by Mohammed’s attorney and his personal representative, but the authorities also noted that, although “identifying details for [Mohammed] have been corroborated … there has been minimal reporting on [his] transactions completed on behalf of Bin Ladin.” Crucially, the summary added, “Efforts to link [Mohammed] to Bin Ladin are complicated by several factors, including incomplete reporting, multiple individuals with [Mohammed]’s name — Haji Wali Mohammad — and lack of post-capture reflections.” As a result, it is, I think, acceptable to conclude that Mohammed actually had no connection with Osama bin laden.

Turning to his behavior at Guantánamo, the authorities noted that he “has been highly compliant with the staff,” and “has committed a low number of infractions relative to other detainees, according to a Joint Task Force-Guantánamo (JTF-GTMO) compliance assessment.” The authorities added that he “appears to have been met semi-regularly by interviewers, based on the number of interviews in which he has participated, and has provided information on camp dynamics as well as on his fellow detainees. According to interviewers in 2005, [he] had a record of providing information on events that were about to take place within the camps at Guantánamo, and judged his reporting to be completely reliable and honest.”

This level of cooperation can only have helped Mohammed in his efforts to persuade the review board to recommend him for release, as is the assessment that, “during his detention [he] has never made statements clearly endorsing or supporting al-Qa’ida or other extremist ideology, but probably has a pragmatic view of the role the Taliban held in Afghanistan. He most likely judged that it was prudent to work with, rather than against, the Taliban Government in the 1990s.” The authorities also noted, “During his detention, [he] appears to have formed a more liberal view of politics in Afghanistan and has said the Taliban will have to change if they want to remain viable in the country, including changing their policy on women’s rights and education.”

Regarding his family situation, the authorities noted that he “probably has a complicated family situation — he has multiple wives and multiple children — split between Afghanistan and Pakistan. Should [he] be repatriated to Afghanistan, we assess he would attempt to return to Pakistan and reunite with his family who still resides there, possibly trying to return his Afghan-based family to Pakistan at the same time.”

The authorities noted that he “has communicated extensively with his family, and does not have current communications with any known or suspected terrorists.” Although those compiling the summary stated that they “judge that [his] familial connections to Hezb-e Islami leader Gulbuddin Hekmatyar — his half-brother, Haji Wakil, was married to Hekmatyar’s niece and his half-sister was married to Hekmatyar’s nephew — may serve as a potential avenue for him to be drawn back into extremism,” it was also noted that “[t]here are no indications that [his] family members are engaged in terrorist activity.”

Below, I’m cross-posting the initial statements made by Mohammed’s personal representative and his attorney, both of which are revealing. The personal representative stated that he was “never a member of the Taliban and was never an extremist,” and was obviously impressed by him, noting that, “Although he has been through many difficult times, he still maintains an excellent attitude and his personality shines vibrantly. In each meeting our conversations always included a story from him ending in laughter for us all. This is because he allows his true self to be known, which is a jovial person that enjoys the company of others.”

Mohammed’s attorney also spoke of his honesty, and emphasized the importance of the mistake made regarding his identity, noting that two US intelligence experts had called his identification “problematic.”

Below are the statements, and I hope, after reading them, you agree with me that Haji Wali Mohammed should be released — and, of course, I sincerely hope that the members of the review board accept that he should finally be freed.

Periodic Review Board, 25 August 2016

Haji Wali Mohammed, ISN 560

Personal Representative Statement

Good morning, ladies and gentlemen of the board. I am the Personal Representative for ISN 560. Thank you for the opportunity to present the case for Haji Wali Mohammed.

Wali Mohammed was a businessman since a very young age. His interests and relationships back home were always very focused on his career as a currency exchanger, which is a common occupation in that region. In this capacity, he executed an investment with the Afghan Central Bank while the Taliban were in power. However, he was never a member of the Taliban and was never an extremist. At times in the currency exchange you may have competitors, creditors, and others that owe you money. Unfortunately for Wali Mohammed, he made an investment that turned out poorly. At that same time there were others that owed him a significant amount he would then use for paying debts. This was all understood by the tribal elders, which spurred a tribal council to determine the outcome. During this council period, just as the results looked favorable for Wali Mohammed, he was quickly arrested at his home.

It is no surprise that Wali Mohammed has been a highly compliant detainee. Although he has been through many difficult times, he still maintains an excellent attitude and his personality shines vibrantly. In each meeting our conversations always included a story from him ending in laughter for us all. This is because he allows his true self to be known, which is a jovial person that enjoys the company of others. His detention has been truly difficult in this regard as he longs to reunite with his family. His children are the light in his life and their memory occupies his thoughts.

It is not Wali Mohammed’s nature to hide his feelings, which makes me confident he plans to do what he says after detention. The rest of his days will consist of significant family time and watching the Afghanistan cricket team he is so very proud of. He will certainly use the knowledge he gained at Guantánamo such as the value of healthy living and an open world view to instill in his children. Although he could support himself, he has a family that pledged to allow him to retire upon his return, which he plans to do. His family members are peaceful and he also desires a non-political and peaceful existence.

Wali Mohammed is open to any country for transfer and would attempt to relocate his family as necessary and permitted by the host nation. I am pleased to answer any questions you may have.

Periodic Review Board, 25 August 2016

Haji Wali Mohammed, ISN 560

Private Counsel Statement

Over more than 14 years in detention, and hundreds of interrogations since his 2002 arrest in Pakistan, Haji Wali Mohammed’s account of his life and business dealings has never varied. The Detainee Profile states that Mr. Mohammed was judged to be completely reliable and honest in his reporting on events about to take place in the camps at Guantánamo. It would be reasonable for the Board to consider the possibility that Mr. Mohammed has been completely reliable and honest in all that he has said since his arrest. We urge the Board to do so.

Mr. Mohammed made one significant mistake of judgment, and he has been very unlucky — most of all in having an extremely common name. He is, however, an honest man.

Wali Mohammed’s business was currency exchange. He bought and sold currency in Pakistan and the UAE with the aim of capitalizing on differences in exchange rates. As he has freely admitted, in late 1997 and early 1998, he entered into a partnership to pursue such a currency arbitrage with the Central Bank of Afghanistan — then under the control of the Taliban government. As Wali Mohammed has said, and as an expert on his behalf confirmed, such partnerships were commonplace before, during, and after the Taliban regime. Wali Mohammed described, and the expert confirms, the sudden and significant volatility in the value of the Pakistani rupee in 1998.

The result was a catastrophic loss — roughly a half-million of the $1.5 million the Central Bank had invested. After the Taliban government learned of the loss, investigators fired the head of the Central Bank, threatened Wali Mohammed with prison, actually imprisoned his cousin, and forced the entire loss on him — in violation of the terms of the deal. This is not the kind of treatment one would expect of someone who was part of or of any importance to the Taliban.

The disastrous failure of the Central Bank transaction also makes it implausible that Wali Mohammed conducted financial transactions for Osama Bin Ladin thereafter — leaving aside that Mr. Mohammed speaks little Arabic and bin Ladin spoke no Pashto. Two intelligence experts on behalf of Mr. Mohammed — one, the former Director of Human Intelligence Collection for the DIA; and the other, a former DIA intelligence analyst, identities expert, and, after the 9/11 attacks, a CIA contractor and charter member of the Terrorist Threat Integration Center, the National Counter Terrorism Center, and the Advanced Analytics Team — have shown, consistent with the Detainee Profile, that the identification of Mr. Mohammed is problematic. Even the late Taliban leader, Mullah Akhtar Mansour, reportedly carried a passport bearing the name “Wali Mohammed.”

Mr. Mohammed’s attenuated marital connections to relatives of Gulbuddin Hekmatyar do not constitute a threat. Mr. Mohammed is deeply devoted to the welfare of his own family and children. He has no interest in politics, or in engaging in dealings in any way connected to the Taliban or any other extremist group. We respectfully ask that the Board find that Wali Mohammed is not a threat to the security of the United States.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album ‘Love and War’ and EP ‘Fighting Injustice’ are available here to download or on CD via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album ‘Love and War’ and EP ‘Fighting Injustice’ are available here to download or on CD via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

September 7, 2016

No Justice for 14 Tortured “High-Value Detainees” Who Arrived at Guantánamo Ten Years Ago

[image error]I wrote the following article (as “Tortured “High-Value Detainees” Arrived at Guantánamo Exactly Ten Years Ago, But Still There Is No Justice”) for the “Close Guantánamo” website, which I established in January 2012, on the 10th anniversary of the opening of Guantánamo, with the US attorney Tom Wilner. Please join us — just an email address is required to be counted amongst those opposed to the ongoing existence of Guantánamo, and to receive updates of our activities by email.

Ten years ago, on September 6, 2006, President Bush announced that secret CIA prisons, whose existence he had always denied, had in fact existed, but had now been closed down, and the prisoners held moved to Guantánamo.

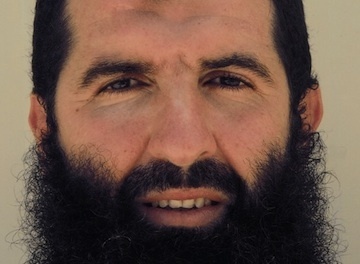

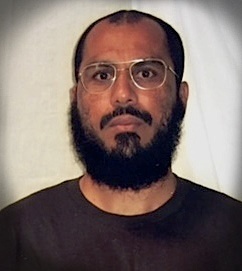

14 men in total were transferred to Guantánamo. Three were named by President Bush — Abu Zubaydah, described as “a senior terrorist leader and a trusted associate of Osama bin Laden,” and Khalid Sheikh Mohammed (KSM) and Ramzi bin al-Shibh, allegedly involved in the 9/11 attacks. Biographies of the 14 were made available, and can be found here. They include three other men allegedly involved in the 9/11 attacks — Walid bin Attash, Ammar al-Baluchi (aka Ali Abd al-Aziz Ali) and Mustafa al-Hawsawi — plus Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri, allegedly involved in the bombing of the USS Cole in 2000, Ahmed Khalfan Ghailani, a Tanzanian allegedly involved in the US Embassy bombings in Kenya and Tanzania in 1998, Majid Khan, a Pakistani alleged to be an al-Qaeda plotter in the US, the Indonesian Hambali and two Malaysians, Zubair and Lillie, the Libyan Abu Faraj al-Libi, and a Somali, Gouled Hassan Dourad.

After the men’s arrival, they were not heard from until spring 2007, when Combatant Status Review Tribunals (CSRTs) were held, which were required to make them eligible for military commission trials. As I explained in my book The Guantánamo Files in 2007, KSM and Walid bin Attash confessed to involvement with terrorism, although others were far less willing to make any kind of confession. Ammar al-Baluchi, for example, a nephew of KSM, and another of the alleged 9/11 co-conspirators, denied advance knowledge of the 9/11 attacks, or of al-Qaeda.

As I described it:

Ammar al-Baluchi was … adamant that he had no involvement with terrorism, and was dismissive of … allegations that he worked on a bomb plot with [Walid] bin Attash. Although he admitted transferring money on behalf of some of the 9/11 hijackers, he insisted that he had no knowledge of either 9/11 or al-Qaeda, and was a legitimate businessman, who regularly transferred money for Arabs, without knowing what it would be used for. His story was backed up by his uncle, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, who stated, “Any dealings he had with al-Qaeda were through me. I used him for business dealings. He had no knowledge of any al-Qaeda links. Ammar is being linked to al-Qaeda because of me.”

As I also explained, “Only two prisoners – Abu Zubaydah and Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri – broached the subject of torture,” although their statements were significant:

Zubaydah … said that he was tortured by CIA to admit that he worked with Osama bin Laden, but insisted, “I’m not his partner and I’m not a member of al-Qaeda.” He also said that his interrogators promised to return his diary to him – [which] contained … evidence of his split personality – and explained that their refusal to do so affected him emotionally and triggered seizures. Speaking of his status as a “high-value” prisoner, he said that his only role was to operate a guest house used by those who were training at Khaldan, and [speaking] of his relationship with bin Laden, [he said], “Bin Laden wanted al-Qaeda to have control of Khaldan, but we refused since we had different ideas.” He explained that he opposed attacks on civilian targets, which brought him into conflict with bin Laden, and although he admitted that he had been an enemy of the US since childhood, because of its support for Israel, pointed out that his enmity was towards the government and the military, and not the American people.

In his tribunal, al-Nashiri said that he made up stories that tied him to the bombing of the USS Cole in 2000 and confessed to involvement in several other terror plots – including the bombing of a French oil tanker in 2002, plans to bomb American ships in the Gulf, a plan to hijack a plane and crash it into a ship, and claims that bin Laden had a nuclear bomb – in order to get his captors to stop torturing him. “From the time I was arrested five years ago,” he said, “they have been torturing me. It happened during interviews. One time they tortured me one way, and another time they tortured me in a different way. I just said those things to make the people happy. They were very happy when I told them those things.”

In February 2008, the alleged 9/11 co-conspirators were put forward for a trial by military commission, as I explained in an article at the time, Six in Guantánamo Charged with 9/11 Murders: Why Now? And What About the Torture? (the sixth man was Mohammed al-Qahtani, specifically tortured in Guantánamo, against whom the charges were eventually dropped).

As pre-trial hearings took place, KSM demonstrated an ability to undermine the proceedings, and to slyly speak about the torture to which he and the others had been subjected, as I explained here, and also here and here. Also in 2008, al-Nashiri was charged, although when President Obama took office the commission process was frozen while the new administration worked out how to proceed.

In April 2009, while this was happening, there was another damaging development for the US, when a harrowing report about the experiences of the HVDs, compiled by the International Committee of the Red Cross in February 2007 and submitted to the government after ICRC representatives had been allowed to interview the men, was leaked to the New York Review Of Books.

Nevertheless, the men themselves remained silenced. As I explained in an article on September 5 about Abu Zubaydah:

Since arriving at Guantánamo … as with all the HVDs, every word he has uttered to his lawyers has remained classified, in contrast to all the other men held. For non-HVDs, although every word uttered between the prisoners and their attorneys is presumptively classified, the attorneys submit notes of their meetings to a Pentagon censorship team — the privilege review team — which then decides whether the notes should be unclassified. Over the years, a significant amount of information has been unclassified by the privilege review team, but the HVDs are an exception, as the Pentagon continues to try to silence them.

Outrageously, this enforced silence has been maintained ever since, as the US military and the Obama administration continue to try to hide evidence of the men’s torture. One way forward would have been to try the men in federal court, and to make whatever case was possible without reference to the use of torture, but although Ahmed Khalfan Ghailani was moved to the US mainland for a trial in May 2009, and was successfully prosecuted and sentenced, lawmakers soon acted to ban any further transfers, and although Attorney General Eric Holder announced in November 2009 that the 9/11 trial would take place in federal court in New York, the administration also ill-advisedly revived the military commissions, and when cynical opposition was mounted to the 9/11 trial plan, President Obama shamefully bowed to the pressure and dropped it.

Since then, the six men charged in the military commissions — the 9/11 five, and Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri — have been stuck in a horrible, dark, farcical limbo, as their lawyers seek to expose evidence of torture, while the government’s lawyers continue to do all they can to prevent that happening, even though, in December 2014, the 500-page executive summary of the Senate Intelligence Committee’s report into the CIA torture program was published, which revealed shocking new information about the program, including “rectal feeding,” which was as horrible as it sounds.

As the Committee explained, the CIA’s torture program was, amongst other findings, “not an effective means of acquiring intelligence or gaining cooperation from detainees.” In addition, the agency’s justification for torture techniques “rested on inaccurate claims of their effectiveness,” and “[t]he interrogations of CIA detainees were brutal and far worse than the CIA represented to policymakers and others.”

As for the rest of the 14, although one of them, Majid Khan, agreed to a plea deal in February 2012, the details of that deal have never been fleshed out, and in the meantime the other six men remained largely hidden — even, in most cases, forgotten — until the last few months, when they were given Periodic Review Boards, a parole-like process designed to allow men who were not already approved for release or facing trials to make a case for why they should be released.

See Somali “High-Value Detainee,” Held in CIA Torture Prisons, Seeks Release from Guantánamo via Review Board, Two Malaysian “High-Value Detainees” Seek Release from Guantánamo Via Periodic Review Boards, Guantánamo “High-Value Detainee” Abu Faraj Al-Libi Seeks Release Via Periodic Review Board, “High-Value Detainee” Hambali Seeks Release from Guantánamo Via Periodic Review Board and Torture Victim Abu Zubaydah, Seen For the First Time in 14 Years, Seeks Release from Guantánamo — although bear in mind that it is unlikely that any of them will be approved for release, even though, overall, the PRBs have, since January 2014, approved 33 men out of 52 for release.

Ten years on, then, as we look at the cases of the “high-value detainees,” it is only appropriate to conclude that justice remains as elusive for them as it did when they were hidden from the world before their arrival at Guantánamo — in the CIA “black sites” that should never have existed.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album ‘Love and War’ and EP ‘Fighting Injustice’ are available here to download or on CD via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album ‘Love and War’ and EP ‘Fighting Injustice’ are available here to download or on CD via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

September 5, 2016

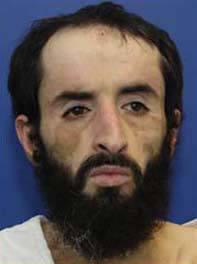

Torture Victim Abu Zubaydah, Seen For the First Time in 14 Years, Seeks Release from Guantánamo

On August 23, 2016, the most notorious torture victim in Guantánamo, Zayn al-Abidin Muhammad Husayn, better known as Abu Zubaydah, became the 61st prisoner to face a Periodic Review Board, and was seen for the first time by anyone outside of the US military and intelligence agencies, apart from representatives of the International Committee of the Red Cross, his attorneys and translators.

On August 23, 2016, the most notorious torture victim in Guantánamo, Zayn al-Abidin Muhammad Husayn, better known as Abu Zubaydah, became the 61st prisoner to face a Periodic Review Board, and was seen for the first time by anyone outside of the US military and intelligence agencies, apart from representatives of the International Committee of the Red Cross, his attorneys and translators.

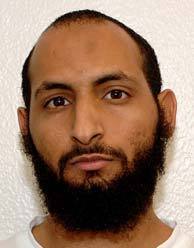

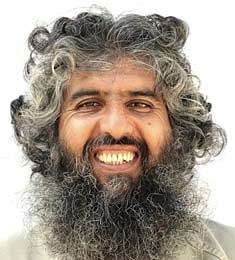

For the Guardian, David Smith wrote, “His dark hair was neat, his moustache and beard impeccably trimmed. His shirt was high-collared and spotlessly white. He sat at the head of the table with a calm, composed mien. It was the first time that the world has seen Zayn al-Abidin Muhammed Husayn, also known as Abu Zubaydah, since his capture in Pakistan 14 years ago.” He added that, “[a]fter a brief technical hitch, a TV screen showed a room with a plain white wall and black shiny table. Anyone walking in cold might have assumed that Abu Zubaydah, with the appearance of a doctor or lawyer, was chairing the meeting. To his left sat an interpreter, dressed casually in shirtsleeves, and to his right were two personal representatives in military uniform with papers before them. A counsel was unable to attend due to a family medical emergency.”

Smith also noted that he “sat impassive, expressionless and silent throughout, sometimes resting his head on his hand or putting a finger to his mouth or chin, and studying his detainee profile intently as it was read aloud by an unseen woman.”

In the New York Times, Scott Shane wrote, “Over 14 years in American custody, Abu Zubaydah has come to symbolize, perhaps more than any other prisoner, how fear of terrorism after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks changed the United States. He was the first detainee to be waterboarded, and his brutal torture was documented in a Senate report. He is among those held without charges and with no likelihood of a trial. The government long ago admitted that he was never the top leader of Al Qaeda it claimed he was at the time of his capture in 2002, but it insists that he may still be dangerous. In all that time, Mr. Zubaydah, now 45, had never been seen by the outside world. That changed on Tuesday, as his calm face was beamed via video feed from the Guantánamo Bay military prison to a Pentagon conference room.” He added, “Dressed in a white tunic and wearing a neatly trimmed beard, Mr. Zubaydah, whose mental stability has been questioned by some American officials, listened attentively, resting his chin on his right hand. He did not react visibly as officials read various statements about him.”

Scott Shane also reported that, in total, “[a] dozen reporters and human rights advocates watched the live video of the 17-minute unclassified part of the proceeding,” in which one of his personal representatives (military personnel appointed to help prisoners prepare for their PRBs) stated that he had told them that he “has no desire or intent to harm the United States or any other country,” that he “has repeatedly said that the Islamic State is out of control and has gone too far,” and that he hopes to “start a business after he is reintegrated into society and is living a peaceful life.”

The PRBs were set up in 2013 to review the cases of all the prisoners not already approved for release or facing trials, and the last of 64 reviews will be taking place this week. To date, 33 men have been approved for release, while just 19 men have had their ongoing imprisonment upheld. Eleven further decisions have yet to be taken. For further details, see my definitive Periodic Review Board list on the Close Guantánamo website.

Born in Saudi Arabia in March 1971 to Palestinian parents, Abu Zubaydah joined the US- and Saudi-funded mujahideen against the Soviet Union in Afghanistan in 1989, and went on to become what Scott Shane described as “a sort of travel agent, camp administrator and facilitator for militant fighters in Afghanistan in the early 1990s,” at the Khaldan camp, an independent camp run by Ibn al-Shaykh al-Libi, a Libyan who died in a Libyan prison in May 2009, allegedly by committing suicide, although that has always seemed unlikely to those who have studied his story closely. A longtime opponent of Col. Gaddafi, he had been seized crossing from Afghanistan to Pakistan in December 2001 and sent by the CIA for torture in Egypt, where he lied about al-Qaeda operatives meeting Saddam Hussein to discuss obtaining chemical weapons, a lie that was used by the US to justify its illegal invasion of Iraq in March 2003. After being sent around a variety of “black sites,” he was returned to Gaddafi’s Libya, where his death was convenient for the US, for Gaddafi and for the Egyptians.

Abu Zubaydah, on the other hand, was seized in a house raid in Faisalabad, Pakistan on March 28, 2002, and was the first victim of the CIA’s “black site” torture program, held first in Thailand, where, as Scott Shane noted, he was subjected to waterboarding — on 83 occasions — and then in Poland, and then in a secret site within Guantánamo, code-named Strawberry Fields. The site in Guantánamo closed in March 2004 and for the next two and a half years he was moved to other “black sites,” probably in Morocco, Lithuania and Afghanistan, before arriving at Guantánamo with 13 other “high-value detainees” almost exactly ten years ago, on September 6, 2006.

I have written extensively about Abu Zubaydah over the years, most recently here, in an article that also provides links to the articles I wrote between 2008 and 2010, when few people were very interested in his case. I also recommend the UK-based Rendition Project’s profile, which provides a good timeline, and summarizes much of what is publicly known about his torture.

In the executive summary of the Senate Intelligence Committee’s report into the CIA’s torture program, published in December 2014, a cable dated July 15, 2002 chillingly described what should happen if Abu Zubaydah died — and also what should happen to him if he lived; namely, that he should “remain in isolation and incommunicado for the remainder of his life.”

This is the text of that cable:

If [Abu Zubaydah] develops a serious medical condition which may involve a host of conditions including a heart attack or another catastrophic type of condition, all efforts will be made to ensure that proper medical care will be provided. In the event that he dies, we need to be prepared to act accordingly, keeping in mind the liaison equities involving our hosts… regardless which [disposition] option we follow however, and especially in light of the planned psychological pressure techniques to be implemented, we need to get reasonable assurances that [Abu Zubaydah] will remain in isolation and incommunicado for the remainder of his life.

17 days after this cable, Jay S. Bybee, Assistant Attorney General at the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel (supposedly responsible for providing impartial legal advice to the executive branch of the US government), approved two memos written by OLC lawyer (and Berkeley law professor) John Yoo (the “torture memos”), cynically attempting to redefine torture so that it was not regarded as torture, and could be used on Abu Zubaydah, in a program created — for a total payment of $81m — by two former US military psychologists, James Mitchell and Bruce Jessen, who had no experience of interrogation, only of training US personnel to resist torture if captured by a hostile enemy. Bybee and Yoo have never been held accountable, although in 2010 an internal investigation holding them accountable was only stopped at the last minute.

The worst phase of Abu Zubaydah’s torture began almost immediately. As the Senate Intelligence Committee report stated:

After Abu Zubaydah had been in complete isolation for 47 days, the most aggressive interrogation phase began at approximately 11:50 AM on August 4, 2002. Security personnel entered the cell, shackled and hooded Abu Zubaydah, and removed his towel (Abu Zubaydah was then naked). Without asking any questions, the interrogators placed a rolled towel around his neck as a collar, and backed him up into the cell wall (an interrogator later acknowledged the collar was used to slam Abu Zubaydah against a concrete wall). The interrogators then removed the hood, performed an attention grab, and had Abu Zubaydah watch while a large confinement box was brought into the cell and laid on the floor. A cable states Abu Zubaydah “was unhooded and the large confinement box was carried into the interrogation room and paced [sic] on the floor so as to appear as a coffin.” The interrogators then demanded detailed and verifiable information on terrorist operations planned against the United States, including the names, phone numbers, email addresses, weapon caches, and safe houses of anyone involved. CIA records describe Abu Zubaydah as appearing apprehensive. Each time Abu Zubaydah denied having additional information, the interrogators would perform a facial slap or face grab. At approximately 6:20 PM, Abu Zubaydah was waterboarded for the first time. Over a two-and-a-half-hour period, Abu Zubaydah coughed, vomited, and had “involuntary spasms of the torso and extremities” during waterboarding. Detention site personnel noted that “throughout the process [Abu Zubaydah] was asked and given the opportunity to respond to questions about threats” to the United States, but Abu Zubaydah continued to maintain that he did not have any additional information to provide. In an email to OMS leadership entitled, “So it begins,” a medical officer wrote:

“The sessions accelerated rapidly progressing quickly to the water board after large box, walling, and small box periods. [Abu Zubaydah] seems very resistant to the water board. Longest time with the cloth over his face so far has been 17 seconds. This is sure to increase shortly. NO useful information so far … He did vomit a couple of times during the water board with some beans and rice. It’s been 10 hours since he ate so this is surprising and disturbing. We plan to only feed Ensure for a while now. I’m head[ing] back for another water board session.”

The use of the CIA’s enhanced interrogation techniques — including “walling, attention grasps, slapping, facial hold, stress positions, cramped confinement, white noise and sleep deprivation” — continued in “varying combinations, 24 hours a day” for 17 straight days, through August 20, 2002. When Abu Zubaydah was left alone during this period, he was placed in a stress position, left on the waterboard with a cloth over his face, or locked in one of two confinement boxes. According to the cables, Abu Zubaydah was also subjected to the waterboard “2-4 times a day … with multiple iterations of the watering cycle during each application.”

Abu Zubaydah’s own account of his torture was given to representatives of the International Committee of the Red Cross, who were allowed to interview the HVDs after their arrival at Guantánamo, and what they were told was so shocking that the ICRC report was later leaked to the New York Review of Books. I posted Abu Zubaydah’s full testimony in an article in March 2010, Abu Zubaydah’s Torture Diary.

During his four and a half years in CIA “black sites,” Abu Zubaydah lost an eye, and was so psychologically destroyed by his torture that he regularly experiences seizures. Writing about his PRB, David Smith noted that, “during the publicly open portion of [his PRB], there was no mention of the torture endured by the 45-year-old Palestinian, who has never been charged with a crime. There was, however, a black eyepatch hanging around his neck. Abu Zubaydah lost sight in one eye some time after he was taken into custody in disputed circumstances. On Tuesday, he could be seen occasionally swapping one pair of spectacles for another as he read documents about his case.”

Since arriving at Guantánamo, however, as with all the HVDs, every word he has uttered to his lawyers has remained classified, in contrast to all the other men held. For non-HVDs, although every word uttered between the prisoners and their attorneys is presumptively classified, the attorneys submit notes of their meetings to a Pentagon censorship team — the privilege review team — which then decides whether the notes should be unclassified. Over the years, a significant amount of information has been unclassified by the privilege review team, but the HVDs are an exception, as the Pentagon continues to try to silence them.

In Abu Zubaydah’s case, the shame of torture is compounded by the fact that, although initially touted as the number 3 in al-Qaeda, he was no such thing, and was not even a member of al-Qaeda. The US authorities eventually dropped its claims that he knew about the 9/11 attacks in advance, but claimed that he had been in charge of a militia force that was supportive of al-Qaeda after the US-led invasion in October 2001. Nevertheless, Abu Zubaydah was never put forward for a trial, suggesting that there was a profound weakness to the US’s revised case against him, and this was apparent in the unclassified summary prepared by the Pentagon for his PRB.

The summary alleged that he “trained and later supervised the training of militant recruits in Afghanistan starting in 1989,” and, in 1994, “started building a mujahidin facilitation network that he ran for several years, recruiting and facilitating the travel of operatives to Afghanistan and on to destinations abroad, including Europe and North America.” It was also claimed that he “played a key role in al-Qa’ida’s communications with supporters and operatives abroad and closely interacted with al-Qa’ida’s second-in-command at the time, Abu Hafs al-Masri.”

The summary went on to claim that he “possibly had some advanced knowledge of the bombings of the US Embassies in Kenya and Tanzania in 1998 and the USS Cole bombing in 2000” — the word “possibly” throwing some serious doubt on the claims — and also that he “was generally aware of the impending 9/11 attacks and possibly coordinated the training at Khaldan camp of two of the hijackers.”

With more confidence, the summary noted that Abu Zubaydah “most actively plotted attacks against Israel, enlisting operatives from various militant groups, including al-Qa’ida, to conduct operations in Israel and against Israeli interests abroad,” adding that he “was convicted in absentia by the Jordanian Government for his role in planning attacks against Israeli, Jordanian, and Western targets during the Millennium time frame in Jordan.”

Following 9/11, according to the summary, Abu Zubaydah “took a more active role in attack preparations, sending operatives to al-Qa’ida senior member Khalid Shaykh Muhammad (KU-10024) to discuss the feasibility of exploding a radiological device in the United States, and supporting remote-controlled bomb attacks against US and Coalition Forces in Afghanistan” — this latter allegation involving US citizen Jose Padilla, British resident Binyam Mohamed and the so-called “dirty bomb plot,” while failing to acknowledge that, as assistant defence secretary Paul Wolfowitz had conceded in May 2002, when Padilla was first seized, there was no plot at all, and the alleged plotters had gone no further than to browse the internet.

Turning to his conduct at Guantánamo, the summary noted that he “has shown a high level of cooperation with the staff at Guantánamo Bay and has served as a cell block leader, assuming responsibility for communicating detainees’ messages and grievances to the staff and maintaining order among the detainees.”

Also according to the summary, “He readily and consistently responded to most if not all lines of questioning by the debriefers, including providing detailed information on his terrorist activities and those of his associates. His debriefers assessed that he withheld information, which might have been to protect historical or current activities.” It was also assessed that he “has used his time in Guantánamo to hone his organizational skills, assess US custodial and debriefing practices, and solidify his reputation as a leader of his peers, all of which would help him should he choose to reengage in terrorist activity — all of which sounds highly unlikely, as his only sphere of influence is the other HVDs.

Those compiling the summary also claimed that he “probably retains an extremist mindset, judging from his earlier statements.” The authors conceded that he “has not made such statements recently,” but decided that that was “probably to improve his chances for repatriation.” Nevertheless, it was noted that he “has condemned ISIL atrocities and the killing of innocent people.”

In terms of his family connections, it was noted that he “has had little communication with his family, suggesting he would lack a support network, even if he tried to leverage his university coursework in computer programming to get a job and reintegrate into society.” I imagine that his lawyers took exception to this claim, although the only statement that was made publicly available was from his personal representatives, and I’ve cross-posted it at the end of this article.

The summary concluded by claiming that some of Abu Zubaydah’s “former colleagues continue to engage in terrorist activities and could help [him] return to planning attacks against Israel and the United States in Pakistan, should he choose to do so.”

So does Abu Zubaydah have a chance of being released?

One of his attorneys, Joe Margulies, a professor at Cornell Law School, thinks not. He told the Guardian that the PRB was “just a formality, a ritual,” adding, “Abu Zubaydah will not be released.”

Margulies also said, “It’s all show, it’s all theatre. Here’s the bottom line. Since Barack Obama took office, there is no one more different — who they thought he was and who he is — than Abu Zubaydah. He has done nothing that authorizes his continued detention. It is morally and legally unjustified.”

Margulies added that Abu Zubaydah now describes himself as a “broken man,”, adding, “I once had hopes that the US would have a thoughtful, fair examination of Abu Zubaydah’s torture but no longer because of the lengths this administration has gone to protect the CIA.”

Margulies also spoke to the New York Times, telling Scott Shane that, in their conversations, Abu Zubaydah “has always been completely honest. He believes in defending Muslims who are under attack,” but he “has always said innocent civilians are never a legitimate target.” Despite what Shane called the government’s “shifting accusations,” Margulies said, as he described it, that “his client was never a member of Al Qaeda and has never been charged with a crime by American authorities.” In Joe Margulies’s words, “He’s the poster child for the torture program, and that’s why they never want him to be heard from again.”

Below is the personal representatives’ opening statement, in which, oddly, Abu Zubaydah (Zayn al-Abidin) is referred to as Zeinelabeden.

Periodic Review Board Initial Hearing, 23 Aug 2016

Zayn Al-Ibidin Muhammed Husayn, ISN 10016

Personal Representative Opening Statement

Good morning, ladies and gentlemen of the Board. We are the Personal Representatives for ISN 10016, Mr. Zayn al-lbidin Muhammed Husayn. We will be working with Zeinelabeden to present his case to you on why he no longer needs to be detained in order to ensure that the security of the United States is not in jeopardy.

Although he initially believed that he did not have any chance or hope to be released, because of the reputation that has been created through the use of his name, he has been willing to participate in the Periodic Review Process. He has been respectful to us in all of our meetings and dealings with him, and he has come to believe that he might have a chance to leave Guantánamo through this process.

Zeinelabeden has expressed a desire to be reunited with his family and begin the process of recovering from injuries he sustained during his capture. He has some seed money that could be used to start a business after he is reintegrated into society and is living a peaceful life. Zeinelabeden has stated that he has no desire or intent to harm the United States or any other country, and he has repeatedly said that the Islamic State is out of control and has gone too far.

Zeinelabeden would like to thank the board for this opportunity to plead his case and looks forward to answering any questions the board may ask him.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album ‘Love and War’ and EP ‘Fighting Injustice’ are available here to download or on CD via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album ‘Love and War’ and EP ‘Fighting Injustice’ are available here to download or on CD via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

September 4, 2016

Photos of the March For Europe in London on Sep. 3 and the Need to Keep Fighting Brexit and the Tories

See my photos on Flickr here.

See my photos on Flickr here.On Saturday September 3, I visited Parliament Square at the end of the latest March for Europe. The first March for Europe took place on July 2, and was attended by around 50,000 people. See my photos here, and my article about it here.

Saturday’s march and rally was a smaller affair, but many thousands of protestors marched in London, and in other cities across the UK, and I believe more people would have taken part had it taken place a few weeks later, after the end of summer had more thoroughly worn off.

The March for Europe organisation describes itself as “a diverse, inclusive movement seeking strong ties between Britain and Europe,” and it provides an opportunity for those of us who were — and are — dismayed by the result of June’s EU referendum — to leave the EU — to highlight our concerns; essentially, as I see it, that leaving the EU will be so disastrous for our economy that MPs, generally supportive of remaining in Europe, must demand that Article 50, triggering our departure, is not triggered. If MPs refuse, those of us who perceive how disastrous leaving the EU would be need to do all we can to publicise the truth about what our isolation would mean.

For my earlier articles about the disastrous impact of the EU referendum, see: UK Votes to Leave the EU: A Triumph of Racism and Massively Counter-Productive Political Vandalism, Life in the UK After the EU Referendum: Waking Up Repeatedly at a Funeral That Never Ends, As the Leaderless UK Begins Sinking, MPs, Media and British Citizens Don’t Seem to Care, On Brexit, the Labour Party, With Its Blundering and Pointless Coup, Lost Its Best Opportunity Ever to Attack the Tories and 1,000+ Lawyers Tell Parliament that UK Cannot Leave EU Without MPs’ Consent.

As I explained when I posted the photos on Facebook:

Today I took these photos of the latest March for Europe in London, joining protestors calling for MPs, who mostly support remaining in the EU, to be allowed to vote on whether or not we should trigger Article 50, the piece of legislation that would officially initiate what would be our economically suicidal departure from the EU. Make no mistake: the funding that supports an untold number of jobs in the UK requires us to stay in the EU, as well as the trade that is so vital to our economy — much, much more so than mistaken notions of “protecting” ourselves from immigration (which, incidentally, is also hugely important for our economy).

Over the last month, I’ve been relieved to get away from the insanity of life in Britain right here, right now, having visited Spain with my family for a much-needed break, and having been extremely unwilling to engage with the ongoing madness since my return.

All good things must come to an end, however, and as the politicians are back at work, and Theresa May held a Cabinet meeting to decide what to do about implementing our departure from the EU, it has not been possible to pretend any longer that what is possibly the worst time of my life politically is a bad dream.

Do I exaggerate? Well no, not really. Not only did 52% of my fellow citizens vote to leave the EU, which continues to make no sense whatsoever, but the media doesn’t want to talk about how disastrous leaving the EU will be, just as they are, in general, unwilling to discuss the profound problems of a country in which the rich continue to get richer and the poor continue to get poorer, the economy is based to an alarming degree on housing greed, and a meaningful job market for the young is non-existent.

The media’s refusal to engage with the real issues is also apparent in their refusal to accept that the Labour Party can have a socialist leader, and echoes the majority of Labour MPs, who refuse to accept the Party members’ choice of leader, and seem determined to destroy the Party completely, allowing the Tories, with their new, unelected leader, Theresa May, to conveniently obscure the fact that this whole mess is the Conservative Party’s fault, and that May is a genuinely dangerous and divisive authoritarian. And this whole mess now sees the Tories — with the addition, I suspect, of a post-Olympics bounce — leading in the polls by what ought to be an unimaginable margin.

The present, therefore, is bleak, and the future even bleaker, unless we act, to publicise the horrors that will come unless we draw back from the brink, and to try to persuade MPs that they must be allowed to vote on triggering Article 50, and that they must vote for us to stay in the EU, a position they themselves hold, and that should not be overturned by a majority in a referendum that is not legally binding and that should never have been called.

Wednesday’s cabinet meeting, when the Tories discussed the next steps for Brexit, was described by the Guardian’s Martin Kettle a showing that “what Brexit really means is still a work in progress.”

Kettle’s article — clearly expressing how “Theresa May will lead us into a bleak future – outside the single market,” continued:

It was always clear, for instance, that meaningful migration controls would be at the heart of any Brexit package that May will accept. Border controls are crucial to the social reform Toryism she stands for. That was explicitly confirmed this week. Free movement as we know it will end. The rules governing movement to and from the 27 remaining European Union member states will change. Downing Street claims to have a pretty clear idea of what it wants to achieve.

Likewise, it has always been obvious that May will look to maintain existing EU single market trading links as much as possible. As an aim it’s a no-brainer. But the reality is something else. You can’t be in the single market without free movement, so if the UK forsakes free movement, in what sense can it still access the single market? Deciding how far to push that is not a dilemma for London, but one for the whole EU.

True, it is a mistake to think that no compromises whatever are possible. The single market is not just one undifferentiated system. Services, digital issues, energy and transport are all not fully unified. Even rights to free movement can be differentiated – like existing length of stay, the position of dependents, students and, in particular, those in and with offers of employment.

Nevertheless, it is naive to imagine May either wants to or could deliver continued freedom of movement in the aftermath of the Brexit vote. The Brexit vote was many things, but at its heart it was a revolt against migration, both real and imagined. Others may be in denial about this, but the prime minister certainly is not.

It therefore follows that Britain has not got a hope in hell of negotiating a deal that keeps the country in the single market after Brexit. Freedom of movement is not a detail, to be casually set aside. And if the UK is determined to end freedom of movement, it also follows that UK access to the single market will be very limited.

Not enough people have grasped this yet. Charles Grant of the Centre for European Reform thinktank says “the British people are living in cloud cuckoo land” about the economic impact. Most prophets of post-Brexit economic doom are lying low at the moment – August’s rebound in manufacturing being the latest reason for them to do so. But it is hard to imagine how a Britain outside the single market will not struggle.

That, I think, is putting it mildly. In contrast to the Leave campaign’s lies about how we would get back the £350m we supposedly gave to the EU every week, and would spend it on the NHS, it is clear that the £350m figure was a blatant lie, and, moreover, the government never had any intention of spending any more money on the NHS, as it wants only to privatise Britain’s greatest asset.

In fact, the UK pays around £13bn a year to the EU, but receives back at least half of that in support for farmers, poor areas of the UK, and scientific research — but only someone delusional would think that all of those supported via EU funding will find their funding replaced by the Tories. This week I met a friend and filmmaker, who works with vulnerable young people, who told me how his entire sector faces total collapse, as funding is withdrawn, and funders — including some large corporate funders — are talking about moving their operations to France or Germany, moves that we are not hearing about, as our media, for the most part, conspires to pretend that it is business as usual.

It is, as I hope you agree, very clearly not business as usual, and I encourage you to think about what can be done in the coming months, and to take a look at the new incarnation of the Remain campaign’s Stronger In Europe project; namely, Open Britain, which is calling for Britain to remain in the single market, and is warning that millions of jobs depend on it. They also have a petition to sign, which will also allow them to keep you updated.

Also see the album here:

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album ‘Love and War’ and EP ‘Fighting Injustice’ are available here to download or on CD via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album ‘Love and War’ and EP ‘Fighting Injustice’ are available here to download or on CD via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

September 2, 2016

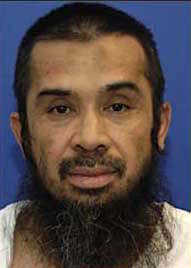

“High-Value Detainee” Hambali Seeks Release from Guantánamo Via Periodic Review Board

On August 18, Hambali, a “high-value detainee” held at Guantánamo since September 2006, became the 60th Guantánamo prisoner to face a Periodic Review Board. The PRBs were set up in 2013 to review the cases of all the prisoners not already approved for release or facing trials, and the last of 64 reviews will be taking place next week. To date, 33 men have been approved for release, while just 19 men have had their ongoing imprisonment upheld. Eleven further decisions have yet to be taken. For further details, see my definitive Periodic Review Board list on the Close Guantánamo website.

On August 18, Hambali, a “high-value detainee” held at Guantánamo since September 2006, became the 60th Guantánamo prisoner to face a Periodic Review Board. The PRBs were set up in 2013 to review the cases of all the prisoners not already approved for release or facing trials, and the last of 64 reviews will be taking place next week. To date, 33 men have been approved for release, while just 19 men have had their ongoing imprisonment upheld. Eleven further decisions have yet to be taken. For further details, see my definitive Periodic Review Board list on the Close Guantánamo website.

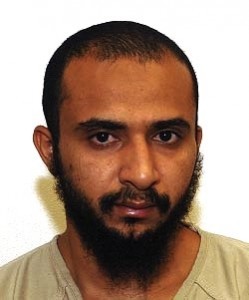

Hambali, an Indonesian born in April 1964, was born Encep Nurjaman, but is also known as Riduan Isamuddin. In the US government’s unclassified summary for his PRB, he was described as “an operational mastermind in the Southeast Asia-based Islamic extremist group Jemaah Islamiyah (JI),” who “served as the main interface between JI and al-Qa’ida from 2000 until his capture in mid-2003.”

Hambali was seized in Bangkok, Thailand in August 2003, with another “high-value detainee,” Mohammed Bashir bin Lap aka Lillie (ISN 10022), whose review took place three weeks ago, in the same week as another of Hambali’s associates, Mohd Farik bin Amin aka Zubair (ISN 10021).

The capture of Hambali was touted by the CIA as an example of the efficacy of torture, but as Human Rights First reported after the executive summary of the Senate Intelligence Committee’s report into the CIA detention program was published in December 2014:

[Although t]he CIA “consistently asserted” in various reports to the administration, the Department of Justice, and the Senate Intelligence Committee “that ‘after applying’ the CIA’s enhanced interrogation techniques, KSM provided ‘the crucial first link’ that led to the capture of Hambali” … “information obtained from KSM during and after the use of the CIA’s enhanced interrogation techniques played no role in the capture of Hambali.”

Human Rights First added:

[T]he CIA had the information needed to capture Hambali — including his role in Jemaah Islamiyah, his close relationship with al Qaeda operatives such as Majid Khan and KSM, and evidence of a $50,000 money transfer from KSM to Hambali’s associates — before the CIA detained KSM. The CIA learned all of the information that led to Hambali’s capture through “signals intelligence, a CIA source, and Thai investigative activities in Thailand.” … The chief of the CIA’s Counterterrorism Center Southeast Asia Branch said of the capture: “Frankly, we stumbled onto Hambali.”

After his capture, as the UK-based Rendition Project has reported, based on the Senate Intelligence Committee’s findings:

Hambali was initially held in US custody in a secret location in Thailand for 3-4 days, during which time he has testified that he was made to stand in a stress position with his hands cuffed to a hook in the ceiling, and kept naked, blindfolded and with a sack over his head.

At some point between 13-14 August 2003, Hambali and Lillie were both transferred from Thailand to CIA custody in Afghanistan … It was at this point that Hambali entered CIA custody, and was, according to CIA records cited by the SSCI report, almost immediately subjected to “enhanced interrogation techniques”. There are no declassified records detailing the torture of Hambali, although there are cables recording the fact that he later recanted the information he provided under torture, which he gave “in an attempt to reduce the pressure on himself … and to give an account that was consistent with what he assessed the questioners wanted to hear.” An Indonesian-speaking debriefer later suggested that Hambali had not in fact been resistant to initial questioning (the rationale for deploying EITs) – his poor English language skills and cultural norms dictating his answers instead. Hambali himself has testified that he was kept naked for most of the first six weeks of his detention in Afghanistan. Clothes were provided during the second week, but then removed again. He has also said that he was beaten repeatedly, with his interrogators placing a thick collar around his neck and then slamming him against walls.

It is not known where he was held after his initial six weeks in Afghanistan, although over the years there have been suggestions that he was held on the Indian Ocean island of Diego Garcia (as I discussed here), and in Morocco and Romania.

Since his arrival at Guantánamo, Hambali has largely been hidden behind a veil of silence like all the “high-value detainees,” except those who have been charged and have been able to sneakily speak out about their torture at pre-trial hearings. One of the most shocking facts about the HVDs is how, unlike the majority of prisoners at Guantánamo, whose attorneys can publicize notes from their meetings after they have been declassified by a Pentagon censorship team, every word uttered between the HVDs and their attorneys has remained classified.

Until his PRB, Hambali’s one opportunity to have his voice heard was at his Combatant Status Review Tribunal in the spring of 2007, when he and the other HVDs who arrived at Guantánamo in September 2006 were given a cursory administrative review of their cases before a trio of military officers — a process that was required if they were to be put forward for trials by military commission. At his tribunal, Hambali, through a linguist, spoke only to deny any involvement in terrrorism, and to claim that he had resigned from Jemaah Islamiya in 2000.

Hambali is one of 23 prisoners facing PRBs who had initially been recommended for prosecution by the high-level, inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force that reviewed all the prisoners’ cases in 2009. However, he was never charged, and he and the 22 others were shunted into the PRB system in 2013, after appeals court judges in Washington, D.C. dismissed some of the few convictions secured in the military commissions, on the basis that the war crimes in question had been invented by Congress, and were not legitimate.

Nevertheless, the allegations against Hambali are so serious that it is surprising that he has never been put forward for a trial — or for prosecution in another country; say, Indonesia, or Australia, whose citizens were largely the victims of the Bali bombings in October 2002, for which Hambali has been accused of involvement, and in which 202 people died, including 88 Australians.

In March, however, the Indonesian government announced that they were not interested in having him back from Guantánamo. As the Miami Herald reported, “Indonesia’s coordinating minister for political, legal and security affairs Luhut Pandjaitan said … that officials are ‘discussing all necessary steps’ to ensure Hambali … stays in US detention.”

In November 2014, an Australian news website reported Hambali’s long detention without a trial, and spoke to former US Marine and military lawyer Dan Mori, who represented Australian Guantánamo prisoner David Hicks in his military commission. Mori, who now practises law in Melbourne, said, “I think in Hambali’s case, seeing him held accountable for Bali may not rank that high in political considerations in the US. But it’s time to put him up in a real court, in Australia, Indonesia or the US, give him a fair trial and provide some sense of closure and an opportunity for the family members to have their say, and see that justice is done for them and the family members that were killed.”

Hambali’s Periodic Review Board

Following the initial outline quoted above, those compiling Hambali’s unclassified summary for his PRB added that he “trained and fought in Afghanistan in the mid-1980s, and subsequently participated in violent jihad throughout Southeast Asia.” According to the summary, he “was involved in the December 2000 attack in Indonesia” — on Christmas Eve, when 18 people were killed in a wave of church bombings in Jakarta and across the country — and also “helped plan the Bali bombings in 2002 and facilitated al-Qa’ida financing for the Jakarta Marriott Hotel bombing the following year.”

The summary added that he “schemed with senior al-Qa’ida leaders regarding post 9/11 attacks against US interests, including attacks inside the United States,” and “also responded to al-Qa’ida’s interest in developing an anthrax program by providing a microbiologist, Yazid Sufaat, for that endeavor.” Those compiling the summary also noted that “[m]ost of these activities were conducted through his lieutenants, Mohd Farik Bin Amin … and Bashir Bin Lap.”

Turning to his behavior in Guantánamo, the summary noted that he “has mostly been compliant … having committed a low number of infractions relative to other detainees.” It was also noted that he “has emerged as a mentor and teacher to his fellow detainees, seemingly exerting influence over them and has been heard promoting violent jihad while leading daily prayers and lectures.”

Those compiling the summary also stated, “We judge that [Hambali] remains steadfast in his support for extremist causes and his hatred for the US. He most likely would look for ways to reconnect with his Indonesian and Malaysian cohorts or attract a new set of followers if he were transferred from Guantánamo Bay. He is close to his family and probably would quickly contact them as well, but we do not know if they would be able to support him financially. Hambali’s younger brother Rusman Gunawan has emerged as part of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant’s (ISIL) Indonesia-based network.”