“High-Value Detainee” Hambali Seeks Release from Guantánamo Via Periodic Review Board

On August 18, Hambali, a “high-value detainee” held at Guantánamo since September 2006, became the 60th Guantánamo prisoner to face a Periodic Review Board. The PRBs were set up in 2013 to review the cases of all the prisoners not already approved for release or facing trials, and the last of 64 reviews will be taking place next week. To date, 33 men have been approved for release, while just 19 men have had their ongoing imprisonment upheld. Eleven further decisions have yet to be taken. For further details, see my definitive Periodic Review Board list on the Close Guantánamo website.

On August 18, Hambali, a “high-value detainee” held at Guantánamo since September 2006, became the 60th Guantánamo prisoner to face a Periodic Review Board. The PRBs were set up in 2013 to review the cases of all the prisoners not already approved for release or facing trials, and the last of 64 reviews will be taking place next week. To date, 33 men have been approved for release, while just 19 men have had their ongoing imprisonment upheld. Eleven further decisions have yet to be taken. For further details, see my definitive Periodic Review Board list on the Close Guantánamo website.

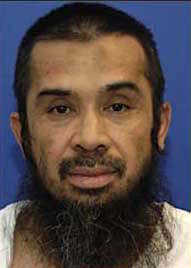

Hambali, an Indonesian born in April 1964, was born Encep Nurjaman, but is also known as Riduan Isamuddin. In the US government’s unclassified summary for his PRB, he was described as “an operational mastermind in the Southeast Asia-based Islamic extremist group Jemaah Islamiyah (JI),” who “served as the main interface between JI and al-Qa’ida from 2000 until his capture in mid-2003.”

Hambali was seized in Bangkok, Thailand in August 2003, with another “high-value detainee,” Mohammed Bashir bin Lap aka Lillie (ISN 10022), whose review took place three weeks ago, in the same week as another of Hambali’s associates, Mohd Farik bin Amin aka Zubair (ISN 10021).

The capture of Hambali was touted by the CIA as an example of the efficacy of torture, but as Human Rights First reported after the executive summary of the Senate Intelligence Committee’s report into the CIA detention program was published in December 2014:

[Although t]he CIA “consistently asserted” in various reports to the administration, the Department of Justice, and the Senate Intelligence Committee “that ‘after applying’ the CIA’s enhanced interrogation techniques, KSM provided ‘the crucial first link’ that led to the capture of Hambali” … “information obtained from KSM during and after the use of the CIA’s enhanced interrogation techniques played no role in the capture of Hambali.”

Human Rights First added:

[T]he CIA had the information needed to capture Hambali — including his role in Jemaah Islamiyah, his close relationship with al Qaeda operatives such as Majid Khan and KSM, and evidence of a $50,000 money transfer from KSM to Hambali’s associates — before the CIA detained KSM. The CIA learned all of the information that led to Hambali’s capture through “signals intelligence, a CIA source, and Thai investigative activities in Thailand.” … The chief of the CIA’s Counterterrorism Center Southeast Asia Branch said of the capture: “Frankly, we stumbled onto Hambali.”

After his capture, as the UK-based Rendition Project has reported, based on the Senate Intelligence Committee’s findings:

Hambali was initially held in US custody in a secret location in Thailand for 3-4 days, during which time he has testified that he was made to stand in a stress position with his hands cuffed to a hook in the ceiling, and kept naked, blindfolded and with a sack over his head.

At some point between 13-14 August 2003, Hambali and Lillie were both transferred from Thailand to CIA custody in Afghanistan … It was at this point that Hambali entered CIA custody, and was, according to CIA records cited by the SSCI report, almost immediately subjected to “enhanced interrogation techniques”. There are no declassified records detailing the torture of Hambali, although there are cables recording the fact that he later recanted the information he provided under torture, which he gave “in an attempt to reduce the pressure on himself … and to give an account that was consistent with what he assessed the questioners wanted to hear.” An Indonesian-speaking debriefer later suggested that Hambali had not in fact been resistant to initial questioning (the rationale for deploying EITs) – his poor English language skills and cultural norms dictating his answers instead. Hambali himself has testified that he was kept naked for most of the first six weeks of his detention in Afghanistan. Clothes were provided during the second week, but then removed again. He has also said that he was beaten repeatedly, with his interrogators placing a thick collar around his neck and then slamming him against walls.

It is not known where he was held after his initial six weeks in Afghanistan, although over the years there have been suggestions that he was held on the Indian Ocean island of Diego Garcia (as I discussed here), and in Morocco and Romania.

Since his arrival at Guantánamo, Hambali has largely been hidden behind a veil of silence like all the “high-value detainees,” except those who have been charged and have been able to sneakily speak out about their torture at pre-trial hearings. One of the most shocking facts about the HVDs is how, unlike the majority of prisoners at Guantánamo, whose attorneys can publicize notes from their meetings after they have been declassified by a Pentagon censorship team, every word uttered between the HVDs and their attorneys has remained classified.

Until his PRB, Hambali’s one opportunity to have his voice heard was at his Combatant Status Review Tribunal in the spring of 2007, when he and the other HVDs who arrived at Guantánamo in September 2006 were given a cursory administrative review of their cases before a trio of military officers — a process that was required if they were to be put forward for trials by military commission. At his tribunal, Hambali, through a linguist, spoke only to deny any involvement in terrrorism, and to claim that he had resigned from Jemaah Islamiya in 2000.

Hambali is one of 23 prisoners facing PRBs who had initially been recommended for prosecution by the high-level, inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force that reviewed all the prisoners’ cases in 2009. However, he was never charged, and he and the 22 others were shunted into the PRB system in 2013, after appeals court judges in Washington, D.C. dismissed some of the few convictions secured in the military commissions, on the basis that the war crimes in question had been invented by Congress, and were not legitimate.

Nevertheless, the allegations against Hambali are so serious that it is surprising that he has never been put forward for a trial — or for prosecution in another country; say, Indonesia, or Australia, whose citizens were largely the victims of the Bali bombings in October 2002, for which Hambali has been accused of involvement, and in which 202 people died, including 88 Australians.

In March, however, the Indonesian government announced that they were not interested in having him back from Guantánamo. As the Miami Herald reported, “Indonesia’s coordinating minister for political, legal and security affairs Luhut Pandjaitan said … that officials are ‘discussing all necessary steps’ to ensure Hambali … stays in US detention.”

In November 2014, an Australian news website reported Hambali’s long detention without a trial, and spoke to former US Marine and military lawyer Dan Mori, who represented Australian Guantánamo prisoner David Hicks in his military commission. Mori, who now practises law in Melbourne, said, “I think in Hambali’s case, seeing him held accountable for Bali may not rank that high in political considerations in the US. But it’s time to put him up in a real court, in Australia, Indonesia or the US, give him a fair trial and provide some sense of closure and an opportunity for the family members to have their say, and see that justice is done for them and the family members that were killed.”

Hambali’s Periodic Review Board

Following the initial outline quoted above, those compiling Hambali’s unclassified summary for his PRB added that he “trained and fought in Afghanistan in the mid-1980s, and subsequently participated in violent jihad throughout Southeast Asia.” According to the summary, he “was involved in the December 2000 attack in Indonesia” — on Christmas Eve, when 18 people were killed in a wave of church bombings in Jakarta and across the country — and also “helped plan the Bali bombings in 2002 and facilitated al-Qa’ida financing for the Jakarta Marriott Hotel bombing the following year.”

The summary added that he “schemed with senior al-Qa’ida leaders regarding post 9/11 attacks against US interests, including attacks inside the United States,” and “also responded to al-Qa’ida’s interest in developing an anthrax program by providing a microbiologist, Yazid Sufaat, for that endeavor.” Those compiling the summary also noted that “[m]ost of these activities were conducted through his lieutenants, Mohd Farik Bin Amin … and Bashir Bin Lap.”

Turning to his behavior in Guantánamo, the summary noted that he “has mostly been compliant … having committed a low number of infractions relative to other detainees.” It was also noted that he “has emerged as a mentor and teacher to his fellow detainees, seemingly exerting influence over them and has been heard promoting violent jihad while leading daily prayers and lectures.”

Those compiling the summary also stated, “We judge that [Hambali] remains steadfast in his support for extremist causes and his hatred for the US. He most likely would look for ways to reconnect with his Indonesian and Malaysian cohorts or attract a new set of followers if he were transferred from Guantánamo Bay. He is close to his family and probably would quickly contact them as well, but we do not know if they would be able to support him financially. Hambali’s younger brother Rusman Gunawan has emerged as part of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant’s (ISIL) Indonesia-based network.”

In response to the allegations, Hambali’s personal representatives (military personnel appointed to help the prisoners prepare for their PRBs) prepared an opening statement that I’ve cross-posted below. In it, they address Hambali’s claims that he seeks only a peaceful life, and quote him saying that he “believes America has diversity and sharing of power which is much better than a dictatorship.”

It remains to be seen whether Hambali managed to impress the board members, but, as I noted above, I find it unlikely, given the severity of the allegations against him, and it would, I think, be appropriate, as Dan Mori stated back in 2014, for him to be subjected to a trial and not held indefinitely without charge — for reasons of justice, as well as for the US to demonstrate a commitment to the rule of law.

Periodic Review Board Initial Hearing

Encep Nurjaman Hambali, ISN 10019

Personal Representative Opening Statement

Good morning, ladies and gentlemen of the Board. We are the Personal Representatives for ISN 10019, Encep Nurjaman Hambali.

Hambali has attended all scheduled meetings. During these meetings he has been respectful and energetic. He has been most enthused about his PRB. He always smiles and never hesitates to answer any questions we have.

During his time in detention he has learned English, some from his interaction with JTF Staff and some from Rosetta Stone. He also taught himself Arabic, which he then held classes to help teach his fellow detainees. He went so far as to have homework and tests for them. His father and uncles were all teachers, so it came naturally for him.

When programs were offered, he was eager to attend. He enjoys watching the programs Planet Life, Blue Planet and also enjoys the great courses on DVD’s.

Hambali has stated he has no ill will towards the US. He believes America has diversity and sharing of power which is much better than a dictatorship.

He states that he wants nothing more than to move on with his life and be peaceful. He hopes to remarry and have children to raise.

We stand ready to answer any questions you may have.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album ‘Love and War’ and EP ‘Fighting Injustice’ are available here to download or on CD via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose debut album ‘Love and War’ and EP ‘Fighting Injustice’ are available here to download or on CD via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and the Countdown to Close Guantánamo initiative, launched in January 2016), the co-director of We Stand With Shaker, which called for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison (finally freed on October 30, 2015), and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by the University of Chicago Press in the US, and available from Amazon, including a Kindle edition — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here — or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and The Complete Guantánamo Files, an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

Andy Worthington's Blog

- Andy Worthington's profile

- 3 followers