Andy Worthington's Blog, page 117

May 9, 2014

Gitmo Clock Marks 350 Days Since President Obama’s Promise to Resume Releasing Prisoners from Guantánamo; 77 Cleared Men Still Held

Please visit, like, share and tweet the Gitmo Clock, which marks how many days it is since President Obama’s promise to resume releasing prisoners from Guantánamo (350), and how many men have been freed (just 12).

I wrote the following article for the “Close Guantánamo” website, which I established in January 2012 with US attorney Tom Wilner. Please join us — just an email address is required to be counted amongst those opposed to the ongoing existence of Guantánamo, and to receive updates of our activities by email.

Yesterday (May 8) marked 350 days since President Obama’s promise, in a major speech on national security issues on May 23 last year, to resume releasing prisoners from Guantánamo. Since that time, however, just 12 men have been released, even though 75 of the 154 prisoners still held were cleared for release in January 2010 by the high-level, inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force that President Obama established shortly after taking office in 2009.

In addition, two more men have been cleared for release this year by a Periodic Review Board, consisting of representatives of the Departments of State, Defense, Justice and Homeland Security, as well as the Offices of the Director of National Intelligence and the Joint Chiefs of Staff, who are reviewing the cases of 71 men recommended for ongoing imprisonment or for prosecution by the task force.

Last year we at “Close Guantánamo” established the Gitmo Clock to mark how long it is since President Obama’s promise, and to note how many men have been freed. Please visit the Gitmo Clock, like it, share it and tweet it if you are disappointed that just 12 men have been freed in the last 350 days, and if you want more action from President Obama.

President Obama’s promise to resume releasing prisoners from Guantánamo was triggered by a prison-wide hunger strike, which reminded the world of the ongoing injustice of Guantánamo and resulted in widespread criticism of the president’s failure to close the prison as he promised when he took office in 2009. The promise came after a period of nearly three years in which just five prisoners were released, after Congress raised obstacles that the president found it politically inconvenient to overcome.

The obstacles were indeed onerous, requiring the president and the defense secretary to certify that, if released, prisoners would be unable to engage in terrorism (a promise that was, I believe, impossible to make), but the legislation contained a waiver allowing the president to bypass Congress if he regarded it as being “in the national security interests of the United States,” which, nevertheless, the president refused to use.

As noted above, since his promise last May, the president has released 12 men from Guantánamo, but 77 cleared prisoners remain. At this rate, it will take until 2020 for the cleared prisoners to be released. This is unforgivable, especially because, in December, Congress eased its restrictions on the release of prisoners.

In his speech last May, President Obama promised to appoint two envoys to deal with the closure of Guantánamo, which he subsequently did, appointing two Washington veterans to the posts, Cliff Sloan at the State Department and Paul Lewis at the Pentagon. These men have been involved in the release of the 12 men, and are, presumably involved in ongoing negotiations to release 20 of the 77 other cleared prisoners who are still held, but for the 57 other cleared prisoners the problem is that they are Yemenis, and the Obama administration is unwilling to release them, citing worries about the security situation in Yemen.

This is completely unacceptable, as it thoroughly undermines the purpose and credibility of both the Guantánamo Review Task Force and the Periodic Review Boards. In addition, as I have repeatedly stated, it represents behavior on the part of the US that is more cruel than that of dictators, who, when they flout international law by imprisoning people without charge or trial, as at Guantánamo, do not pretend that there is a review process that will lead to the prisoners’ release, and then follow up by not releasing them. That cruelty has cast a pall of despair over the remaining prisoners at Guantánamo, and with good reason.

To address it, the president needs to immediately release the Yemeni prisoners who have been cleared for release — if not all 57, then at least those whose immediate release was recommended by the task force in January 2010 — 25 men in total, who were not released because, in December 2009, a Nigerian Man, Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab, who was recruited in Yemen, tried and failed to blow up a plane bound for Detroit with a bomb in his underwear, and, in the resulting hysterical backlash, President Obama imposed a moratorium on releasing Yemenis from Guantánamo, which he only lifted on his speech last May. At the time, he said that the Yemenis would be reviewed “on a case by case basis,” but in the last 350 days not one of them has been released.

Here at “Close Guantánamo,” we believe that all the Yemenis cleared for release should be freed, although we recognize that starting with the 25 would be less contentious politically. We acknowledge that, back in January 2010, the task force recommended 30 other Yemenis for “conditional detention,” which it described as being “based on the current security environment in that country.”

The task force added, “They are not approved for repatriation to Yemen at this time, but may be transferred to third countries, or repatriated to Yemen in the future if the current moratorium on transfers to Yemen is lifted and other security conditions are met.”

With the moratorium now lifted, these 30 men should, logically, join their 25 compatriots on the next plane home, but, as noted above, we are prepared to accept that, as a first move, the 25 men who were told in January 2010 that the US had no interest in continuing to hold them should be be released, with the 30 others following once it has been established that the release of their 25 compatriots has been a success.

The two other cleared Yemenis are those whose release was recommended by their Periodic Review Boards, and for those reviews to have any credibility, they too should be released as soon as possible.

What you can do now

Call the White House and ask President Obama to release the Yemeni prisoners whose release has been recommended by the Guantánamo Review Task Force and the Periodic Review Boards. Call 202-456-1111 or 202-456-1414 or submit a comment online.

Please also visit this page on the Witness Against Torture website to see a list of protests to mark the first anniversary of President Obama’s speech on May 23, and, if you can, please do get involved. I’ll be posting more about this day of action soon.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

May 7, 2014

MPs Support Alarming Citizenship-Stripping Measures Introduced by Theresa May

Is there no end to this government’s flagrant disregard for the fundamental rights of its citizens? Today, by 305 votes to 239, the House of Commons overturned amendments to the current Immigration Bill made by the House of Lords, which concerned home secretary Theresa May’s proposals to strip naturalised British citizens of their citizenship without any form of due process, even if doing so makes the individuals in question stateless.

Is there no end to this government’s flagrant disregard for the fundamental rights of its citizens? Today, by 305 votes to 239, the House of Commons overturned amendments to the current Immigration Bill made by the House of Lords, which concerned home secretary Theresa May’s proposals to strip naturalised British citizens of their citizenship without any form of due process, even if doing so makes the individuals in question stateless.

Back in March, as I described it in my article, “The UK’s Unacceptable Obsession with Stripping British Citizens of Their UK Nationality” MPs first voted, by 297 votes to 34, to pass the citizenship-stripping clause, which Theresa May had added to the Immigration Bill in January, and which, due to its addition at the last minute, had not received any scrutiny. Since 2002, the government has had the power to remove the citizenship of dual nationals who they believe to have done something “seriously prejudicial” to the UK, but May’s new legislation was designed to increase her powers, “allowing her to remove the nationality of those who have acquired British citizenship, even if it will make them stateless, if they have done something ‘seriously prejudicial to the vital interests’ of the UK,” as described in December by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, which has been covering this story closely.

In April, by 242 votes to 180, the House of Lords replaced the proposal with an amendment requiring it to be further considered by a joint committee of the Commons and Lords before being implemented, an eminently sensible proposal that should not have been overturned by 305 MPs in the House of Commons.

As the London-based legal action charity Reprieve described it in a press release, “The Government had brought forward minor tweaks to the proposal in response to the Lords’ criticisms, but even with these in place the decision to deprive Britons of their citizenship will still be entirely in the hands of the Home Secretary, and it will still be possible to render Britons stateless as a result. As it will only apply to naturalised Britons — people not born as UK citizens — the proposal will create two classes of citizens: those who are vulnerable to having their citizenship arbitrarily removed at any time, without any requirement for a legal process, and those who (through accident of birth) are not.”

The Bill will now return to the House of Lords, for the next round in what Reprieve described as “Parliamentary ‘ping-pong.’” Those who care about the rights of UK citizens can write to members of the House of Lords here (or here or here) to encourage them to oppose the clause when it returns to them for consideration.

It remains profoundly important that the clause is removed from the legislation, because it is so at odds with the values that the UK claims to uphold. As I explained when MPs first passed the citizenship-stripping clause in March:

The Bureau [of Investigative Journalism] has established that 41 individuals have been stripped of their British nationality since 2002, and that 37 of these cases have taken place under Theresa May, since the Tory-led coalition government was formed in May 2010, with 27 of these cases being on the grounds that their presence in the UK is “not conducive to the public good.” In December, the Bureau confirmed that, in 2013, Theresa May “removed the citizenship of 20 individuals — more than in every other year of the Coalition government put together.” As the Bureau suggested in February 2013, it appears that, in two cases, the stripping of UK citizenship led to the men in question subsequently being killed by US drone attacks.

The two men, Bilal al-Berjawi, a British-Lebanese citizen who grew up in London, and Mohamed Sakr, a British-Egyptian citizen who was born in the UK, travelled to Somalia in 2009, where they allegedly became involved with the militant group al-Shabaab. Theresa May stripped both men of their British nationalities in 2010, and, as the Bureau described it:

In June 2011 Mr. Berjawi was wounded in the first known US drone strike in Somalia and [in 2012] was killed by a drone strike – within hours of calling his wife in London to congratulate her on the birth of their first son. His family have claimed that US forces were able to pinpoint his location by monitoring the call he made to his wife in the UK. Mr. Sakr, too, was killed in a US airstrike in February 2012 … Mr. Sakr’s former UK solicitor said there appeared to be a link between the Home Secretary removing citizenships and subsequent US actions. “It appears that the process of deprivation of citizenship made it easier for the US to then designate Mr. Sakr as an enemy combatant, to whom the UK owes no responsibility whatsoever,” Saghir Hussain said.

Back in March, I also mentioned how Ian Macdonald QC, the president of the Immigration Law Practitioners’ Association, who has long opposed the disturbing trend towards secrecy and unaccountability in Britain’s post-9/11 anti-terror laws, described the citizenship orders as “sinister,” and said of the government, “They’re using executive powers and I think they’re using them quite wrongly. It’s not open government; it’s closed, and it needs to be exposed.”

Back in December, when approached by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism for an explanation of why there had been a marked rise in deprivation of citizenship orders, a spokesperson for the Home Office did not provide a direct answer, but said, “Citizenship is a privilege, not a right, and the Home Secretary will remove British citizenship from individuals where she feels it is conducive to the public good to do so.”

That is patently untrue. Citizenship is a right not a privilege, and anyone who worries about the abuse of executive power needs to speak up and be heard. At present, Theresa May is aiming her unacceptable policy at British Muslims travelling to Syria, but who knows who she — or future home secretaries — will decide is the next enemy within?

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

May 6, 2014

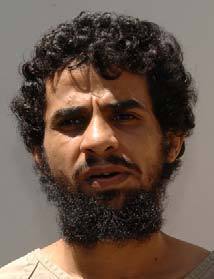

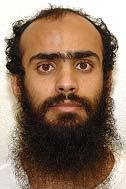

Saudi Prisoner Refuses to Attend His Periodic Review at Guantánamo, Complains About Intrusive Body Searches

On Monday, a Saudi prisoner at Guantánamo, Muhammad Abd al-Rahman al-Shumrani, refused to attend his Periodic Review Board, convened to assess whether he should continue to be held without charge or trial, or whether he should be recommended for release. He refused to attend for a reason that his personal representatives — two US military officers appointed to represent him — described as “very personal and tied to his strong cultural beliefs.” The representatives explained that he “has consistently stated his objection to the body search required to be conducted prior to his attendance at legal meetings or other appointments,” adding that he regards “the body search as conducted, which requires the guard to touch the area near his genitals,” as “humiliating and degrading.” The representatives stressed, however, that his refusal to attend, because of his problems with the body search, does “not imply an unwillingness to cooperate.”

On Monday, a Saudi prisoner at Guantánamo, Muhammad Abd al-Rahman al-Shumrani, refused to attend his Periodic Review Board, convened to assess whether he should continue to be held without charge or trial, or whether he should be recommended for release. He refused to attend for a reason that his personal representatives — two US military officers appointed to represent him — described as “very personal and tied to his strong cultural beliefs.” The representatives explained that he “has consistently stated his objection to the body search required to be conducted prior to his attendance at legal meetings or other appointments,” adding that he regards “the body search as conducted, which requires the guard to touch the area near his genitals,” as “humiliating and degrading.” The representatives stressed, however, that his refusal to attend, because of his problems with the body search, does “not imply an unwillingness to cooperate.”

The PRBs were set up last year to review the cases of 71 of the remaining 154 prisoners. 46 of these men were recommended for ongoing imprisonment without charge or trial by the high-level, inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force that President Obama appointed to review all the prisoner’s cases shortly after he took office in 2009.

The task force issued its report recommending prisoners for release, prosecution or ongoing imprisonment in January 2010, and in March 2011 President Obama issued an executive order authorizing the ongoing imprisonment of the 46 men, on the basis that they were too dangerous to release, even though insufficient evidence existed to put them on trial.

It was, of course, outrageous that the president was prepared to authorize indefinite detention on the basis of information that failed to rise to the level of evidence — in other words, on the basis of dubious reports by US personnel and dubious statements made by the prisoners themselves or by their fellow prisoners, in circumstances in which telling the truth was unlikely. President Obama tried to address this by promising that the men would receive periodic reviews of their cases, but, disgracefully, the first of these did not take place until November 2013, two years and eight months after the executive order was issued.

By this time, 25 other men — initially recommended for prosecution by the task force — had been made eligible for the PRBs, after the military commission trial system was dealt a major blow by appeals court judges in Washington D.C., who overturned two of the only convictions achieved in the much-criticized trials because the war crimes of which the men had been convicted were not internationally recognized, and had, in fact, been invented by Congress.

Since the first PRB in November 2013, five more hearings have taken place, which I have been reporting in detail. That first hearing led to a recommendation (in January) for the release of the prisoner in question, a Yemeni named Mahmoud al-Mujahid, and just two weeks ago another Yemeni, Ali Ahmad al-Razihi, also had his release recommended. This is good news in theory, although in practice there is no sign of when, if ever, they will actually be released, as they have merely joined a long-standing list of Yemeni prisoners who have been cleared for release but are still held, consisting of 55 men whose release was recommended by the Guantánamo Review Task Force in January 2010. These men are still held because of US fears about the security situation in Yemen, but it is, of course, completely unacceptable to establish a review process — or, as it now is, two review processes — and then to not release prisoners recommended for release.

In between the two positive if inconclusive results for Mahmoud al-Mujahid and Ali Ahmad al-Razihi, the review board — which includes representatives of the Departments of State, Defense, Justice and Homeland Security, as well as the office of the Director of National Intelligence and the Office of the Joint Chiefs of Staff — concluded that another Yemeni, Abdel Malik al-Rahabi, should continue to be held (even though the supposed evidence against him is profoundly untrustworthy), and last month two other reviews took place, for which decisions have not yet been reached — in the cases of Ghaleb al-Bihani, a Yemeni who worked in Afghanistan as a cook, and Salem bin Kanad, listed by the US as a Yemeni, but who apparently has close family in Saudi Arabia.

For Muhammad al-Shumrani’s PRB, it was left to his personal representatives to make the case for his release, which they did to the best of their ability in a statement to the board, even though they were unable to meet him because of his refusal to undergo the body searches. They explained that he has only made an exception when he has had the opportunity to talk to his family, but added that he communicated with them in preparation for his PRB through letters.

They also noted that he expressed a willingness to take part in the Saudi government’s rehabilitation program if released, which, as they put it, shows that “he does not have a desire to return to the fight and should not be considered a continuing significant threat to the United States.”

In contrast, the US authorities tried to portray al-Shumrani as a threat, noting in the unclassified summary of evidence against him that he was “recruited for jihad while working as a high school teacher in Saudi Arabia,” and subsequently traveled to Afghanistan, where he underwent military training and fought against the Northern Alliance for a few months. The US authorities allege that, in addition, he “almost certainly” also fought against US forces, but no proof is provided for this additional allegation.

More worrying is the description of al-Shumrani as “a problematic and unpredictable detainee,” who has “committed several significant disciplinary infractions and used his authority as a religious leader to encourage other detainees not to cooperate with detention staff.” His personal representatives addressed these claims in their statement, explaining how his “resistant mindset while in detention is similar to the mindset and behaviors we expect of our own military members should they be captured and become Prisoners of War.”

It seems to me that this is an accurate description of al-Shumrani, and that, as a result, the board members will need to assess how long they believe it is justifiable to hold those seized as soldiers — and who, it should be noted, cannot even be proven to have taken up arms against US forces. The authorities, on the other hand, are unwilling to back down. Their unclassified summary of al-Shumrani describes how he “repeatedly has told interrogators and other detainees he would reengage in extremism if he were released from Guantánamo,” which sounds alarming, but “extremism” is not defined, and, it seems to me, refers more to an ongoing belief in the rights of Muslims to self-defence than it does to any active threat on al-Shumrani’s part, especially, as the US authorities also acknowledge that he “has minimal known associations with at-large extremists.”

A decision about Muhammad al-Shumrani’s case will probably not be reached for a couple of months, so in the meantime I’m posting below the personal representatives’ opening statement.

Periodic Review Board, May 5, 2014

Muhammad Abd Al-Rahman Al-Shumrani, ISN 195

Opening Statement of Personal Representative

Good morning ladies and gentlemen of the board. We are the Personal Representatives for Muhammad Abd Al-Rahman Al-Shumrani. We will be presenting Muhammad’s case to you today without the aid of private counsel.

Additionally, Muhammad has elected not to participate during this portion of the process, but we want you to know that though he is not physically present at today’s board, he has been cooperative during the earlier stages of the PRB process. He has provided information to us via letters on several occasions that help explain why he has chosen not to appear today. He has also provided us some information about what he would like to do in the future.

Muhammad has spent 12 years at Guantánamo Bay and during that time he has missed the birth of many family members and has had to endure the pain of losing his father. In fact, he found out about the death of his father 8 years after the fact. Now he desires to be reunited with his family, especially his mother, and make up for lost time. Today you will hear about the composition of his family and his future desires, should he be released from Guantánamo Bay.

Muhammad benefits from being a Saudi citizen and according to the unclassified dossier “the Saudi government has provided the appropriate assurances to facilitate the transfer of detainees.” As a result of “these assurances, the United States has transferred over 100 detainees, including two in 2013, to Saudi Arabia.”

Saudi Arabia has established a robust rehabilitation and aftercare program “focused on changing the attitudes of Saudis who have been involved in terrorism and include detainees transferred from the Guantánamo Bay detention facility. These components [of the program] include counseling, religious instruction, sports, and social and therapeutic activities.” Additionally, family members are able to visit the detainees going through the program. Muhammad has told us that he is willing to go through the government program even though he does not know the details of the program. This shows his desire to turn his life around and return home to be with his family.

Muhammad would like to be here today and talk to the board personally, but his reason for not participating is very personal and tied to his strong cultural beliefs. He has consistently stated his objection to the body search required to be conducted prior to his attendance at legal meetings or other appointments. For this detainee, the body search as conducted, which requires the guard to touch the area near his genitals, is humiliating and degrading. Muhammad has not only refused to attend our scheduled meetings with him, he has even refused dental appointments, knowing that his own personal comfort would be affected by failure to meet with the medical provider. In fact, the only appointments Muhammad takes are the limited opportunities he has to talk to his family. I will share Muhammad’s own words with you later today and I believe you will see that his convictions do not imply an unwillingness to cooperate, nor do they establish or support in any way that he is a significant threat to the United States, but rather that he is a man who cannot subject himself to searches he finds degrading.

Since being in detention, Muhammad’s behavior has been classified according to his unclassified dossier as “problematic and unpredictable” and it has been stated he uses “his authority … to encourage other detainees not to cooperate with detention staff.” In many ways, and as those of you with prior military experience would likely acknowledge, Muhammad’s resistant mindset while in detention is similar to the mindset and behaviors we expect of our own military members should they be captured and become Prisoners of War. Article III of the Code of Conduct states, “If I am captured, I will continue to resist by all means available.”

Muhammad’s pattern of behavior in detention does not mean he is a significant threat to the United States; rather that he is behaving like a man captured in conflict who is continuing to resist by all means available, a quality which we train for and require from our military members.

As I have already stated, Muhammad has said he would like to return to Saudi Arabia and go through the country’s extensive detainee rehabilitation program so that he may rejoin his family. Never in our inquiries to Muhammad did we ask about or even mention the Saudi rehabilitation program. We did not ask him if he would be willing to participate in the program in any of our correspondence. Rather, Muhammad volunteered the information freely, thus showing he does not have a desire to return to the fight and should not be considered a continuing significant threat to the United States.

You have probably already reviewed the historical information that led to Muhammad’s detention. As you review the additional documentation we have provided, and have the opportunity to ask questions, I urge you to consider the whole picture when making your recommendation. Muhammad is a man who wants to start over and should be given a second chance. He should not be considered a continuing significant threat to the United States.Thank you for your time and consideration. We are happy to answer any questions you may have throughout this proceeding.

Note: The next three PRBs are for the last two Kuwaitis in Guantánamo, Fawzi al-Odah and Fayiz al-Kandari, and for Muhammad Murdi Issa al-Zahrani, a Saudi. All three were notified of their PRBs in February, but there has, however, been no indication yet of when the hearings will take place.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

May 4, 2014

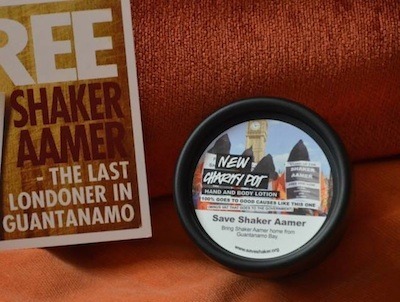

Cosmetics Firm Lush Supports the Release of Shaker Aamer from Guantánamo

I’m very pleased to note that the cosmetics firm Lush has created a Charity Pot calling for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison. The 20-year old company, which has over 900 stores in over 50 countries and is a fixture on many British high streets, supports dozens of small grassroots groups dedicated to environmental issues, animal protection and human rights, raising money for them through its Charity Pots (Facebook page here).

I’m very pleased to note that the cosmetics firm Lush has created a Charity Pot calling for the release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison. The 20-year old company, which has over 900 stores in over 50 countries and is a fixture on many British high streets, supports dozens of small grassroots groups dedicated to environmental issues, animal protection and human rights, raising money for them through its Charity Pots (Facebook page here).

The company’s Shaker Aamer Charity Pot supports the Save Shaker Aamer Campaign, who I have worked with for many years to try and secure the release of Shaker Aamer. 100% of the profits from the pots go to the charities that Lush supports, so this is perfect opportunity for those of you who care about plight of Shaker Aamer — most recently highlighted here and here — to support the campaign by buying pots — for personal use, perhaps, or as gifts for friends and family. They cost £6.95 each.

A list of UK shops is here, and an international list is here.

Back in the mists of time, I discovered Lush through a previous incarnation of the company called Cosmetics to Go, and in 2008, while working with Reprieve, the London- based legal action charity, I liaised with the company on a campaign to secure the release from Guantánamo of the Al-Jazeera journalist Sami al-Haj and the British resident Binyam Mohamed, who were featured in a bath bomb called “Guantánamo Garden” (see here and here). By February 2009, both men had been freed (see here for my report on Lush’s response to Sami al-Haj’s release).

Unfortunately, securing the release of Shaker Aamer is proving far more difficult, even though he has twice been cleared for release by the US authorities (in 2007 and 2010), and even though the British government claims to be actively seeking his release and his return to his family in the UK. If you want to do more for Shaker, please sign the international petition calling for his release on the Care 2 Petition Site, and please also sign the new petition on Change.org.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

May 2, 2014

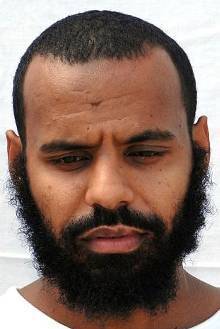

Guantánamo Review Boards (3/3): Salem Bin Kanad, from Riyadh, Refuses to Take Part in a System That Appears Increasingly Flawed

This article, looking at the recent Periodic Review Board for Salem bin Kanad, a prisoner held at Guantánamo since January 20, 2002, is the last of three providing updates about developments in the Periodic Review Boards, a system put in place last year to review the cases of 71 prisoners (out of the 154 men still held), who were designated for indefinite detention without charge or trial, or designated for trials that will not now take place. The original recommendations were included in a report that was issued in January 2010 by a high-level, inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force that President Obama had appointed to review the cases of all the prisoners still held when he took office in January 2009.

This article, looking at the recent Periodic Review Board for Salem bin Kanad, a prisoner held at Guantánamo since January 20, 2002, is the last of three providing updates about developments in the Periodic Review Boards, a system put in place last year to review the cases of 71 prisoners (out of the 154 men still held), who were designated for indefinite detention without charge or trial, or designated for trials that will not now take place. The original recommendations were included in a report that was issued in January 2010 by a high-level, inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force that President Obama had appointed to review the cases of all the prisoners still held when he took office in January 2009.

The task force recommended 48 men for indefinite detention without charge or trial, on the extremely dubious basis that they were too dangerous to release, even though it was conceded that insufficient evidence existed to put them on trial — which means, of course, that the so-called “evidence” is no such thing. In March 2011, President Obama responded to the task force’s recommendations by issuing an executive order authorizing their ongoing imprisonment without charge or trial, although he did promise that the men would receive periodic reviews to establish whether they should still be regarded as a threat.

Disgracefully, the Periodic Review Boards did not begin until last November, after two of the 48 “forever prisoners” had died, and 25 other men had been added to the list of prisoners eligible to take part in them — men who, although recommended for trials, will not now be prosecuted, after appeals court judges overturned two of the only convictions in the military commissions at Guantánamo, on the basis that the war crimes of which the men had been convicted were not internationally recognized, and had been invented by Congress. The boards consist of representatives of the Departments of State, Defense, Justice and Homeland Security, as well as the office of the Director of National Intelligence and the Office of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, who meet at an office in Virginia and hear testimony by video link from Guantánamo.

The first PRB, in November, was for Mahmoud al-Mujahid, a Yemeni, and in January the board recommended his release, although, shamefully, all that means is that he joined a list of 75 other Yemenis who were cleared for release by the task force in January 2010, but are still held because of the US authorities’ concerns about the security situation in Yemen. These concerns may be legitimate, but they are completely unacceptable as a basis for denying the release of men approved for release by high-level US government reviews.

In January, a second Yemeni, Abd al-Malik Wahab al-Rahabi, had his case reviewed, although, on March 5, the board recommended his ongoing imprisonment, based on tired old allegations that should not have been deemed credible.

On March 20, a third Yemeni, Ali Ahmad al-Razihi, had his case reviewed, and on April 23 he, like Mahmoud al-Mujahid, was approved for release — joining the other 56 Yemenis waiting for the US to realize that holding men they have publicly said they don’t want to hold is thoroughly disgraceful.

My article about Ali Ahmad al-Razihi was the first of my three updates, and was followed by an article about Ghaleb al-Bihani, another Yemeni and the fourth man to be given a PRB, whose hearing took place on April 8. No decision has yet been taken by the board in al-Bihani’s case.

The PRB for Salem bin Kanad

The hearing for Salem bin Kanad — who is between 37 and 39 years of age, and was initially identified as Salem Ben Kend — took place on April 21, putting his case in the spotlight for the first time in his 12 years in US custody. All that was known about him from the thousands of pages of documents that the Pentagon was obliged to release in 2006 was that he had traveled to Afghanistan to support the Taliban, and had “spent three months on the front line before he and his group was sent north to an area near Konduz [Kunduz] to fight the Northern Alliance,” and that he had then been ordered to surrender, and had ended up imprisoned in Qala-i-Janghi, a fort controlled by the Northern Alliance commander Abdul Rashid Dostum, where he survived a notorious massacre by US, British and Northern Alliance forces. In his classified military file, released by WikiLeaks in 2011, it was revealed that, in the massacre, he was “shot in the chest and legs.”

Despite having an opportunity to speak to the board on April 21, Salem bin Kanad turned it down. Army Lt. Col. Todd Breasseale, a Pentagon spokesman, said that he“chose not to participate,” and also that he “elected not to be represented by private counsel.”

As a result, he was only represented by two US military officers — personal representatives assigned to represent prisoners facing PRBs — who painted a compelling portrait of a “peaceful man,” held in Camp Six, where cooperative prisoners are held, who wants only to “return to a normal, productive life” with his family in Riyadh, in Saudi Arabia, where his father runs an automobile business, and where, it was noted, his relatives “have no identified extremist affiliation.” The personal representatives also stated that he wants to “attend a vocational school to study English and Computer Science,” which, he believes, “along with the sales experience he gained while working in his father’s auto detailing business, will set him up well for a career in sales and marketing.”

The personal representatives also revealed that bin Kanad has two daughters, the youngest of whom was just two months old when her last saw her. His status as a father has not previously emerged in any reports, but his personal representatives made it clear that they are a central concern of his, and that he “wants to urge both daughters to complete their educations.”

What was particularly noteworthy in the personal representatives’ statement was the identification of bin Kanad as a Saudi, as the US authorities have always regarded him as a Yemeni — or, as the unclassified summary explained, he “probably has relatives in both Yemen and Saudi Arabia.” It seems evident from bin Kanad’s own explanation of his circumstances that his wife lives in Yemen, as the representatives explained that he “has repeatedly spoken of his two daughters and desperately wants to bring them home to Riyadh.”

Bin Kanad’s strong Saudi connections should defuse the US authorities’ concerns about him returning to Yemen, as explained in the unclassified summary, in which it was stated, “The robust presence of al-Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) in [Kanad’s] home region of Hadramawt probably would encourage his reengagement in extremist activities if he were repatriated to Yemen.”

Furthermore, despite efforts earlier in bin Kanad’s detention to portray him as a prisoner of some significance, it is clear that the authorities have no real reason for wishing to continue holding him. His classified military file contained an allegation, by John Walker Lindh, the US citizen who also survived the Qala-i-Janghi massacre, that bin Kanad was his field commander, but that allegation appears to have become discredited. In the unclassified summary, the US authorities only claimed that he “fought on the frontlines in a Taliban unit commanded by Abu Turab al- Pakistani,” and “possibly served a low-level leadership role replacing Abu Turab when he was wounded.”

The authorities also noted that he “appears to have few associations with at-large extremists, based on his lack of interaction with anyone outside of Guantánamo save for family members,” who, as noted above, “have no identified extremist affiliation.”

As a result, it is, I believe, time for the authorities to send Salem bin Kanad back to his family in Riyadh, so that he can begin the long-overdue process of reconciling himself with his father, and supporting his daughters.

I hope the board agrees, but in the meantime I’m posting below the full text of the statement made by his personal representatives, which I hope you find useful.

Periodic Review Board, April 21, 2014

Salem Ahmad Hadi Bin Kanad, ISN 131

Opening Statement of Personal Representative

Good morning ladies and gentlemen of the board, we are the Personal Representatives for Salem Ahmad Hadi Bin Kanad. To my right/left is our translator, (translator’s call sign). Today, we will be presenting our case without the aid of a private counsel. We’ve met with Salem on multiple occasions and have learned a lot about him and his family. Salem has eagerly worked with us to prepare his case during the Periodic Review Board process, and we are eager to demonstrate to this board that he is a peaceful man. He has put his trust in us as his military personal representatives to guide him through the process and show to you that he should no longer be considered a continued significant threat to the United States.

To accomplish this, we would like to go over some factors for you to consider while deciding Salem’s case. First, Salem has been a consistently compliant detainee. As stated in his UNCLASSIFIED Compendium, “[Salem] has not presented significant force-protection problems while at the Guantánamo Bay detention facility.” A testament to his good behavior is the fact that he resides within a facility where only the most compliant detainees are authorized to live. It is the only camp in which the detainees are allowed to live in communal conditions. Residing within this camp means Salem has abided by a lengthy set of rules and guidelines established by the camp administrators. Second, during his detention he has become a trusted leader by his fellow detainees. In fact, his fellow detainees once elected him a block leader and entrusted him with the responsibility of addressing detainee issues with the security force. Third, Salem has taken it upon himself to maintain an exercise regimen that helps him stay physically fit and healthy considering the limiting conditions of the camp. All three of these attributes illustrate that Salem is a man capable of taking care of himself and his fellow detainees all while abiding by camp rules.

A common theme throughout our discussions with Salem has been his strong desire to return to a normal, productive life in Saudi Arabia. He would like to return to his home in Riyadh in order to reunite with his father, brothers and sisters; all of whom have no identified extremist affiliation. Once home, he plans to attend a vocational school to study English and Computer Science. He’s confident those studies, along with the sales experience he gained while working in his father’s auto detailing business, will set him up well for a career in sales and marketing. Most importantly, establishing a stable career will finally allow him to become a supportive father to his two daughters. Salem has repeatedly spoken of his two daughters and desperately wants to bring them home to Riyadh. He has never met his youngest daughter in person as she was only two months old the last time he saw her. He can’t wait to make up for the time lost during her childhood. While providing for their needs he wants to urge both daughters to complete their educations. His youngest daughter is currently in elementary school and, through his regular phone calls, he has urged her to focus on her studies. Salem’s goal for her would be to accomplish something he never did: complete her education through high school. His oldest daughter is currently learning to be a housewife, in accordance with their custom, but has shown great interest in sewing. Salem hopes to enroll her in a vocational school so that she can become a seamstress and pursue a job doing something she loves.

Salem also desires to rekindle his relationship with his father in order to be the loving son he should have been. His father is aging and has sold his business in order to retire. During our conversations with Salem it has been readily apparent that he would like to spend time with his father; making up for the time they lost. As a child, Salem worked for his father and helped with the business that provided a stable income for the entire family. Ultimately, he wants to take the work ethic his father taught him and apply that to his studies and career. He wants to be capable of providing financial support for his father, brothers, sisters and family once he is working.

In order for Salem to achieve his goals he will need the support of his family. In fact, Salem’s family is praying for his transfer and is readily prepared to support him upon his return to Riyadh. His brother has contacted us stating the family is prepared to take Salem in and provide for his every need while he reestablishes himself as a productive member of the community. The Board can review the brother’s statement in Exhibit 2 [not included in the publicly available documents]. The family will provide him a place to live, support him financially, and assist with his enrollment in a vocational school to further his education.

As you review Salem’s case, we would like you to consider the person he is today, his goals of becoming a supportive member of his family, and his desire to reunite with his two daughters and father. We hope the statements provided show you the person we’ve gotten to know, and we believe Salem’s written statement only bolsters our case. Salem is looking towards the future and the man that he wants to be. He wants to be a loving father, a supportive son, an educated man, and a productive working member of his community. He would like to live the rest of his life in peace. We believe the information and documents we’ve provided this Board fully support you finding that he no longer should be considered a continued significant threat to the United States of America.

Note: The next PRB — the sixth — is for Muhammed Abd al-Rahman al-Shamrani (ISN 195), a Saudi, and takes place on May 5.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

April 30, 2014

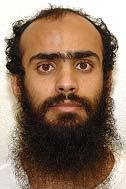

Guantánamo Review Boards (2/3): Ghaleb Al-Bihani, a Cook, Asks to Be Sent Home to Yemen or to Another Country

Last week, I published the first of three new articles about the Periodic Review Boards at Guantánamo, looking at the hearing for a Yemeni prisoner, Ali Ahmad al-Razihi, who had the opportunity to ask for his freedom on March 20.

Last week, I published the first of three new articles about the Periodic Review Boards at Guantánamo, looking at the hearing for a Yemeni prisoner, Ali Ahmad al-Razihi, who had the opportunity to ask for his freedom on March 20.

Ali is one of 71 prisoners — out of the 154 men still held — who were either designated for ongoing imprisonment without charge or trial in January 2010 by the high-level, inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force that President Obama established shortly after taking office in 2009 (46 men in total), or were recommended for prosecution (25 others).

The 46 had their ongoing imprisonment without charge or trial approved by President Obama in an executive order issued in March 2011, on the alarming basis that they were allegedly too dangerous to release, even though insufficient evidence existed to put them on trial. The president tried to sweeten this unacceptable endorsement of indefinite detention by promising that the men would receive periodic reviews of their cases, but the first of these did not take place until last October.

By this time the 46 had been joined by 25 others, initially recommended for trial by military commission. These men’s intended prosecutions had unravelled when appeals court judges dealt a massive blow to the legitimacy of the commissions in October 2012 and January 2013 by dismissing two convictions, on the basis that the war crimes for which the men had been convicted were not internationally recognized, and had been invented by Congress.

Since the PRBs started last November, just five men — all Yemenis — have had their cases reviewed, by representatives of the Departments of State, Defense, Justice and Homeland Security, as well as the office of the Director of National Intelligence and the Office of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, who meet at an office in Virginia and hear testimony by, or on behalf of the prisoners by video link from Guantánamo.

The first man, Mahmoud al-Mujahid, had his release recommended in January, which, theoretically, was reassuring, although disgracefully it hasn’t led to his release. Instead, he merely joined a list of 75 other Yemenis who were approved for release by the Guantánamo Review Task Force in January 2010, but are still held — apparently indefinitely — because of concerns about the security situation in Yemen.

A second man, Abd al-Malik Wahab al-Rahabi, had his PRB on January 28, although in his case the board decided that his ongoing imprisonment “remains necessary to protect against a continuing significant threat to the security of the United States,” even though the allegations against him — including a claim that he had been a bodyguard for Osama bin Laden — were generally untrustworthy, produced by other prisoners who had been tortured, or were known to be unreliable.

The PRB for Ali Ahmad al-Razihi, which I wrote about last week, in the first of three articles providing updates about the PRBs, took place on March 20, and almost as soon as I had published my article I had to provide an update, because the board recommended him for release, as with Mahmoud al-Mujahid, and with the same problems — although cleared for release, he too only joins a list of Yemenis cleared for release but still held, now numbering 57 men.

The PRB for Ghaleb al-Bihani

The fourth PRB, on April 8, was for Ghaleb al-Bihani, a 34-year old whose case first came to prominence over five years ago, in January 2009, when his habeas corpus petition was turned down by Judge Richard Leon in the District Court in Washington D.C. Al-Bihani had been in Afghanistan at the time of the US-led invasion in October 2001, but only as a cook working “in the kitchen of a pro-Taliban Arab militia, the 55th Arab Brigade, whose ranks included al-Qaida members,” as Carol Rosenberg described it in the Miami Herald.

Notoriously, as I explained in an article at the time, “How Cooking For The Taliban Gets You Life In Guantánamo,” Judge Leon refused to grant al-Bihani’s habeas petition because, as he explained in his ruling, “Faithfully serving in an al-Qaida affiliated fighting unit that is directly supporting the Taliban by helping to prepare the meals of its entire fighting force is more than sufficient [for continued detention]. After all, as Napoleon himself was fond of pointing out, ‘An army marches on its stomach.’”

Al-Bihani appealed, but was unsuccessful — twice — in the court of appeals, and in April 2011 the Supreme Court refused to hear his case. As his lawyers at the New York-based Center for Constitutional Rights described it, “As a result, an alleged kitchen aide, who was never accused of having raised arms against U.S. or allied forces, has lost [12] years of his life at Guantanamo and continues to be held indefinitely.”

In April 2011, details of al-Bihani’s ill-health became public knowledge, when WikiLeaks released classified military files on the majority of the Guantánamo prisoners, and he was described as being “on a list of high risk detainees from a health perspective.” As CCR described it, “His ailments include Type 2 Diabetes, asthma, chronic migraine headaches, chronic neck and lower back pain, depression, and anxiety. His blood sugar level fluctuates dangerously, rising as high as 700.”

Despite this, he has tried to remain positive abut his future. As CCR recently explained in another profile of his case:

Despite dealing with serious health problems and the emotional toll of his 12-year, indefinite detention, Mr. Al-Bihani has tried to make the best of his circumstances. He has endeavored to educate himself and learn skills to prepare for life after Guantánamo.

He is an avid reader, requesting dozens of books over the years. He has also been learning English and Spanish, developing his GED proficiency, educating himself about his diabetes, and trying to cope with his anxiety and depression through exercise, including yoga.

Mr. Al-Bihani has talked for years of his hopes for a new life, ideally in a new country. He hopes to become a father and start a family of his own, pursue his education and a career, and care for his health.

In contrast, the US authorities still maintain that al-Bihani is a threat. In an unclassified summary for his PRB, he is described as “almost certainly” a member of al-Qa’ida,” with “extensive knowledge of al-Qa’ida and Taliban leadership and operational procedures,” which “suggests he actively supported both groups,” although it was conceded that “he probably did not hold a leadership position in either.”

This is clearly an attempt to exaggerate the importance of a cook, and is reinforced by references to his alleged “associations with at-large extremists,” which turns out to be a reference primarily to his brothers. Six of them also traveled to Afghanistan for jihad (and one, cleared for release, is also at Guantánamo), and, according to the government’s unsubstantiated claims, “at least one … is a member of al-Qa’ida in the Arabian Peninsula.” The US authorities allege that, as a result, some or all of his brothers would “almost certainly would induce [al-Bihani] to reengage in extremist activities if he were repatriated to Yemen.”

This is not necessarily true, of course, although, in response, al-Bihani has long expressed his desire to be released in another country. As the authorities described it, since 2010 he “has expressed a fear of repatriation to the Middle East, stating that he no longer wishes to fight and would prefer to be transferred to Europe to establish a life away from jihad.” Nevertheless, the authorities refuse to take this at face value, explaining that, because of what is perceived as al-Bihani’s “longstanding tendency to provide conflicting statements about his own involvement in terrorism,” this “does not allow for an assessment with confidence about whether his stated intent to renounce jihad is credible.”

The authorities also note that he “has been a problematic detainee throughout his tenure at the Guantánamo Bay detention facility, having committed several significant personal disciplinary infractions and incited or participated in mass protests.”

Despite this analysis, al-Bihani was robustly defended at his PRB on April 8 by two people representing him — firstly, the personal representative appointed to represent him, an unnamed US military official, who was evidently so impressed by his desire to rebuild his life in peace that he opened his statement by saying that he “does not meet the standard for ‘continuing significant threat to the security of the United States’”; and secondly, his civilian lawyer, Pardiss Kebriaei of CCR, who expanded on the details provided by CCR above — in particular, his thirst for knowledge and his desire for a second chance.

I’m posting below both of these statements, which I believe provide a compelling case for al-Bihani’s release, although it remains to be seen, of course, if the board is prepared to agree with that assessment. Sadly, al-Bihani’s own words are not included, as the prisoners themselves remain censored, continuing the revolting tradition at Guantánamo of the authorities silencing the prisoners as much as possible, and thereby reinforcing their tired myths about the threat that insignificant prisoners like Ghaleb al-Bihani pose.

I hope you find the statements useful, and that you share this information if you do. A decision about al-Bihani is expected within the next few weeks, and, whether he is approved for release or not, the Periodic Review Boards remain a poor substitute for justice, either approving the ongoing imprisonment of people who are not a threat, or toothlessly recommending their release.

Periodic Review Board Ghaleb Nasser Al-Bihani, ISN 128

April 8, 2014

Opening Statement of Personal Representative

Bottom Line Up Front: Detainee does not meet the standard for “continuing significant threat to the security of the United States.”

Ladies and gentlemen of the Board, good morning. I am the Personal Representative for Ghaleb Nasser Al-Bihani, ISN number 128. In our submission, we have provided you with information that demonstrates that Mr. Al-Bihani should not be considered a continuing significant threat to the security of the United States.

Looking at the factors listed in the DTM 12-005 for assessing whether a detainee meets this standard, they can be grouped into three general categories: factors that go to whether a detainee has the capacity to be a significant and continuing threat to the security of the United States, whether he has the motive, and whether he will have the opportunity. In the vulnerability assessment methodologies with which I am familiar, if any of the three is absent or sufficiently low, then a threat is considered to be negligible.

Over the past 6 months, I have worked closely with Mr. Al-Bihani. I believe that he currently has neither the motive nor the capability to be a significant threat to U.S. National Security, and that he will not become one after his transfer. I say this as both a warfighter and as someone who has years of experience performing vulnerability assessments.

Starting with motive, Mr. Al-Bihani’s wish is, ideally, to be transferred to a third country where he can build a new and independent life. Camp records indicate that he has expressed this desire repeatedly over the past several years, since 2009. While the compendium for Mr. Al-Bihani implies that he may have ill intentions toward the U.S. when it states that he has been a “… problematic detainee throughout his tenure …,” camp records instead show that there have been only isolated and relatively minor incidents since 2009. He and his Private Counsel will speak more during their statements about his motives and his efforts to prepare for a better future. Our medical expert witness will address in her testimony [not included in the documents made available to the public] how Mr. Al-Bihani’s health problems can affect behavior.

In terms of capability, Mr. Al-Bihani does not have skills that would present a “significant” threat to U.S. National Security. Mr. Al-Bihani did not hold a leadership position with AI Qaeda or the Taliban — he didn’t even fight with them. He was not involved in specific attacks. Twelve years ago, he was an assistant cook in one of the groups that fought against the Northern Alliance, prior to U.S. combat operations, and then surrendered. The compendium itself states that he “… probably did not hold a leadership position in either [Al Qaeda or the Taliban].” And while his compendium lists various training, even if he had received every bit of the training listed, it would be equivalent to that provided to a Private in the U.S. Army — by himself, not a significant threat to a nation’s security.

In terms of opportunity, any concerns the Board may have about his environment after release can be mitigated. Again, if given a choice, Mr. Al-Bihani wants to go to a third country to build an independent life. Wherever he is transferred, he is willing to agree to appropriate security measures, and he is willing to participate in a rehabilitation program. As you will hear, he will also have the support and positive influence of his relative, and NGO support, to help ensure his successful reintegration.

Based on these factors, the U.S. has insufficient reason to believe that Mr. Al- Bihani has the motive or capability to be a significant continuing threat to U.S. National Security — or that any concerns about potential opportunity cannot be addressed. In closing, ladies and gentlemen, Ghaleb Nasser Al-Bihani does not meet the standard to be considered a continuing significant threat to the security of the United States.

Periodic Review Board Ghaleb Nasser Al-Bihani, ISN 128

April 8, 2014

Opening Statement of Private Counsel Pardiss Kebriaei

Good morning. My name is Pardiss Kebriaei and I am the Private Counsel for Ghaleb Nasser Al-Bihani. Thank you for the opportunity to assist Mr. Al-Bihani in this review process.

I have represented Guantánamo detainees since 2007, including men who have been resettled in third countries and repatriated to Yemen. I have represented Mr. Al-Bihani since early 2011. I have had over two dozen meetings and phone calls with him since then, for a total of over 100 hours of conversation.

I began representing Mr. Al-Bihani after the close of his habeas case, so most of those hours have been spent discussing the here and now, and the future. I would like to share two main observations of Mr. Al-Bihani based on our conversations and interactions.

The first is that Mr. Al-Bihani has been talking about his wish for a new start in a third country for years. From our first phone call in April 2011, he spoke about wanting resettlement. He has continued to express this desire in virtually every conversation we have had since then, asking me about possibilities from Qatar, to Spain, to Costa Rica, to Uruguay. As he will tell you, he will accept transfer to any country the government determines is appropriate, including Yemen or Saudi Arabia. But if he had a choice, he would be sent to a third country. This is not because he thinks a third country is the fastest route for release, although certainly, he wants that route. It is not because he thinks this is what the Board wants to hear, because he has been saying for years that he wants resettlement. He will tell you more about his motivations, but what he has expressed to me continuously is his desire for a new beginning. A break from what has come before. A real chance to build a better life in an environment where there is stability, economic and educational opportunity, and calm. I believe that he wants these things.

The second is that I have observed Mr. Al-Bihani try hard to prepare himself for the life he wants to build. We have submitted to the Board a long list of books he has requested over the years. He has asked for Arabic-English dictionaries, Spanish language books, GED books, and DVDs on Latin America. He has asked for the latest research on diabetes, for yoga magazines, and self-help books. He has taken pages of notes on his readings. He has worked with his doctors to make various medical requests. He has come to every meeting we have scheduled over the past three years to work with me. He came to every meeting his Personal Representative and I scheduled over the past six months to prepare for this review, and said he was hopeful about it. Two weeks ago, he sat in a three-hour meeting pushing through a migraine headache to work on the statement that he is going to read to you. He began these efforts years ago, before anyone was checking. And he has tried to persevere in spite of his chronic health problems, which have at times been debilitating.

Wherever Mr. Al-Bihani is transferred, my organization will help support his rehabilitation and reintegration. For several clients who were resettled and repatriated by the Administration in 2009 and 2010, we worked with the State Department and host governments on transition plans for clients; we visited clients multiple times after release; we served as an ongoing point of contact for local authorities; we provided financial assistance and referrals for needs ranging from live-in interpreters to mental health care; and we partnered with other NGOs and organizations to help address other needs. We were a trusted and experienced resource in facilitating a successful transition for these clients, who are now rebuilding their lives. We would offer the same assistance for Mr. Al-Bihani.

We are still in contact with a client who was approved for transfer and resettled in a European country in 2009. The government’s assessment of him was not djssimilar to some of the assertions about Mr. Al-Bihani. Like dozens of resettled men, he went to a country where he had never been, where support had to be provided, and it was. It is five years later. He is fluent in the language of that country and working as an interpreter, he got married a couple of years ago, and he just had his first child. The United States successfully transferred him, as it has many others, and it can do so again with Mr. Al- Bihani. He is his own person and he should be evaluated on his own merits.

I will now turn it over to Mr. Al-Bihani to speak directly to you about his efforts and intentions.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

April 28, 2014

As Boris Johnson Approves Monstrous Convoys Wharf Development, New Campaign Opposes 236 Planned Towers in London

I was rather pleased that I was out of the country when Boris Johnson, London’s Mayor, announced on March 31 that he was approving plans for the development of Convoys Wharf in Deptford, because, in a city overrun with soulless riverside developments, designed almost exclusively for wealthy foreign investors and unaffordable for ordinary Londoners, it is a particularly depressing example, and one that, for me, is close to home, as I live just up the road from Deptford.

I was rather pleased that I was out of the country when Boris Johnson, London’s Mayor, announced on March 31 that he was approving plans for the development of Convoys Wharf in Deptford, because, in a city overrun with soulless riverside developments, designed almost exclusively for wealthy foreign investors and unaffordable for ordinary Londoners, it is a particularly depressing example, and one that, for me, is close to home, as I live just up the road from Deptford.

The 40-acre riverside site has been vacant since 2000, when it was closed by its last owner, News International, which used it as a dock for importing newsprint, and, since 2002, developers — initially NI itself, and, since 2005, the Hong Kong-based Hutchison Whampoa, which bought the site off NI — have been trying to gain approval for a Dubai-style high-rise residential development on the site, consisting of 3,500 homes, featuring one 48-storey tower, and two 38-storey towers, far higher than anything else on the shoreline for miles around.

Normally, Chinese businessmen with £1bn to spend on luxury housing on London’s riverfront don’t have to wait for years to have their plans accepted, but the problem with Convoys Wharf is that it was and is a place of great historic importance — the site of the first of King Henry VIII’s Royal Dockyards, which was first developed in 1513 to provide ships for England’s rapidly expanding Royal Navy.

Because of the historic importance of the site, English Heritage raised objections to the various plans for the site — the designs put forward first by Richard Rogers, then by Aegis and, most recently, by Terry Farrell — because none of them focused on the importance of the site’s heritage, and two local groups were also formed, which also reflected these concerns — Build the Lenox, which proposed to build a replica of the Restoration warship Lenox where she was originally built, and Sayes Court Garden, a proposal to create a world class garden and Centre for Urban Horticulture on the site of a pioneering garden established by the writer and botanist John Evelyn in 1653, which is on the edge of the Convoys Wharf site.

Other concerns — primarily about the size of the planned towers, the number of affordable homes and the inability of the local area to cope with the traffic demands of the project — were raised by local campaigners and by Lewisham Council, which was responsible for approving the plans until, in November, Hutchison Whampoa, tired of the democratic process, appealed directly to London’s Mayor, Boris Johnson, who obligingly took the decision out of Lewisham’s hands and into City Hall, where it was only a matter of time before he approved the plans.

The Mayor approved the plans after a three-hour hearing at City Hall on March 31, at which he made a point of establishing that Hutchison Whampoa must pay heed to the Build the Lenox and Sayes Court Garden campaigns. However, as the academic and Deptford resident Karen Liljenberg explained on her blog: