Andy Worthington's Blog, page 113

July 16, 2014

For the First Time, A Nurse at Guantánamo Refuses to Take Part in Force-Feedings, Calls Them a “Criminal Act”

Reprieve, the legal action charity whose lawyers represent a number of prisoners still held at Guantánamo Bay revealed yesterday that a nurse with the US military at the prison “recently refused to force-feed” prisoners “after witnessing the suffering” it caused them.

Reprieve, the legal action charity whose lawyers represent a number of prisoners still held at Guantánamo Bay revealed yesterday that a nurse with the US military at the prison “recently refused to force-feed” prisoners “after witnessing the suffering” it caused them.

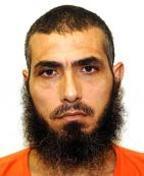

Abu Wa’el Dhiab, a Syrian prisoner long cleared for release from Guantánamo, who is in a wheelchair as a result of his physical deterioration after 12 years in US custody without charge or trial, told his lawyer Cori Crider during a phone call last week (on July 10) that the male nurse “recently told him he would no longer participate in force-feedings.”

Dhiab reported that the nurse said, “I have come to the decision that I refuse to participate in this criminal act.”

He added that, “after the man made his decision known, he never saw him again,” and Reprieve noted that he had “apparently been assigned elsewhere.”

Reprieve also noted that the nurse had spoken to Mr. Dhiab about what he perceived to be “the discrepancy between military descriptions of force-feeding and the reality.” He said, as Mr. Dhiab described it, “before we came here, we were told a different story. The story we were told was completely the opposite of what I saw.” Mr. Dhiab added that other nurses had “voiced their concern” about force-feeding, but had stated that they “had no power to object.” He said he frequently heard comments along the lines of, “Listen, we have no choice. We are worried about our job, our rank.”

Reprieve described how the nurse’s stand was “thought to be the first case of ‘conscientious objection’ to force-feeding at Guantánamo since a mass hunger-strike began at the prison last year.”

Abu Wa’el Dhiab’s story will be familiar to these who are studying Guantánamo closely, as he is one of six cleared prisoners offered new homes in Uruguay by President Mujica and is “currently engaged in a high-profile court battle against force-feeding, winning the first-ever disclosure of videotapes of the practice,” as Reprieve described it, and as I reported here.

Last month, his lawyers were permitted to watch the videotapes at a Pentagon facility in Virginia, and afterwards Cori Crider stated, “I had trouble sleeping after viewing them.” However, as was revealed in yesterday’s press release, the lawyers are “banned from disclosing their contents to the public or even, in unprecedented censorship, to other security-cleared Guantánamo lawyers.” On June 20, 16 mainstream media organizations submitted a motion in which they are seeking to have the force-feeding tapes made public.

In response to the news about the nurse’s principled opposition to force-feeding, Cori Crider said, “This is a historic stand by this nurse, who recognized the basic humanity of the detainees and the inhumanity of what he was being asked to do. He should be commended. He should also be permitted to continue to give medical care to prisoners on the base but exempted from a practice he rightly sees as a violation of medical ethics.”

In the Miami Herald, veteran Guantánamo reporter Carol Rosenberg reported how, in response to questions about the nurse, Navy Capt. Tom Gresback, a spokesman for the prison, said by email, “There was a recent instance of a medical provider not willing to carry out the enteral feeding of a detainee. The matter is in the hands of the individual’s leadership.” He added that the nurse had been given “alternative duties.”

Rosenberg added that the nurse’s refusal to force-feed prisoners took place “sometime before the Fourth of July.”

She also quoted Cori Crider saying that the nurse’s decision took “real courage,” and that “none of us should underestimate how hard that has been.”

Rosenberg also noted that the nurse was with the Navy medical corps, but explained that the Miami Herald had “not been able to determine the nurse’s name or home base,” although Cori Crider explained that Mr. Dhiab had “described the nurse as a perhaps 40-year-old Latino who turned up on the cellblocks in April or May, with the rank of a ‘captain,’” although Rosenberg thought it likely that he was a Navy lieutenant. She also noted how, last year, in the New England Journal of Medicine, civilian doctors on the US mainland had “decried as unethical the Guantánamo military medical staff’s practice of force-feeding mentally competent hunger strikers,” and had “urged a medical mutiny.”

No one knows how many of the 149 men still held at Guantánamo are currently on hunger strike, as the military stopped reporting the numbers in December, after a nine-month period in which numbers had been reported on a daily basis. In February, Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison, stated that there were 35 hunger strikers at the time, and that 18 of them were being force-fed.

The Miami Herald also reported further details about Cori Crider’s recent call with Abu Wa’el Dhiab, noting that, as the newspaper put it, he “described how he came to witness the nurse’s evolution toward refusing to tube feed across two or three months of treatment.” Mr. Dhiab explained that this evolution was “very compassionate.”

Carol Rosenberg added further details about the force-feeding of prisoners, as explained to reporters who visit Guantánamo Bay but are not allowed to see the force-feedings take place. She wrote that “a Navy medical team uses a calculus of meals missed and weight lost to decide when to recommend a once or twice a day tube feeding of a can of Ensure or other nutritional supplement.” The commander of the camps, who is a Navy admiral and not a doctor, is required to approve each feeding, which is managed by a “sailor trained as a medic.”

The process of the force-feeding itself is well documented — not least in the video of Yasiin Bey (formerly the rapper Mos Def) being force-fed last year, and in the animated film about force-feeding produced for Reprieve and the Guardian.

Cori Crider also explained how, before his complete refusal to be involved in force-feeding, the nurse “at times waived a doctor’s order to do a tube feeding,” as the Miami Herald described it.

She said Mr. Dhiab had told her, “Here, whenever a person has a fever or is sick, the typical force-feeding crew were still very rough with you. However, when he came to the block and saw that the person had a fever or was sick, he would say, ‘OK, because you are sick, you are not able to receive force-feeding’ and left them alone for that day.”

Crider added that the nurse should be permitted to tell his story to Judge Gladys Kessler, who issued the order requiring the authorities to release videotapes of Mr. Dhiab’s force-feeding to his lawyers, “despite any nondisclosure agreements detention center staff are obliged to sign,” in the Miami Herald‘s words. Judge Kessler said last month that a full hearing on the merits of Abu Wa’el Dhiab’s force-feeding challenge should take place by Labor Day, which falls on the first Monday in September.

“If he [the nurse] wants to give that evidence he should be allowed to give it,” Crider added.

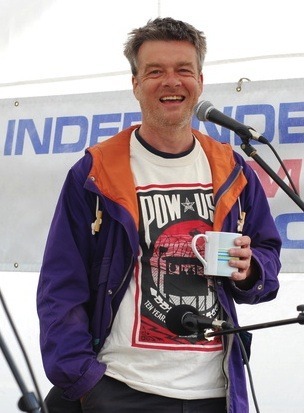

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

July 14, 2014

Andy Worthington: An Archive of Guantánamo Articles and Other Writing – Part 15, July to December 2013

Please support my work!

Over eight years ago, in March 2006, I began researching and writing about the Bush administration’s “war on terror” prison at Guantánamo and the 779 men (and boys) held there since the prison opened in January 2002. Initially, I spent 14 months researching and writing my book The Guantánamo Files, based, largely, on 8,000 pages of documents publicly released by the Pentagon in the spring of 2006, and, since May 2007, I have continued to write about the men held there, on an almost daily basis, as an independent investigative journalist — for 20 months under President Bush, and, shockingly, for what is now five and a half years under President Obama.

My mission, as it has been since my research first revealed the scale of the injustice at Guantánamo, continues to revolve around four main aims — to humanize the prisoners by telling their stories; to expose the many lies told about them to supposedly justify their detention; to push for the prison’s closure and the absolute repudiation of indefinite detention without charge or trial as US policy; and to call for those who initiated, implemented and supported indefinite detention and torture to be held accountable for their actions.

As I highlight every three months through my quarterly fundraising appeals, I have undertaken the lion’s share of this work as a reader-supported journalist and activist, so if you can support my work please click on the “Donate” button above to donate via PayPal.

In January 2010, I began to put together chronological lists of all my articles, in the hope that doing so would make it as easy as possible for readers and researchers to navigate my work — the 2,238 articles I have published in the last seven years.

This 15th list, covering July to December 2013, marked a period of hope for campaigners, after the men still held embarked on a prison-wide hunger strike to remind the world of the ongoing injustice of Guantánamo, and put pressure on President Obama to revisit his failed promise to close the prison and to resume releasing prisoners, which he had largely stopped doing since the fall of 2010 when Congress raised obstacles that he was unwilling to overcome, even though he had the means to do so.

In the period from October 2010 to July 2013, just five men were freed from Guantánamo, even though, throughout that period, over half the men still held had been cleared for release in January 2010 by the high-level, inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force that President Obama established shortly after taking office in 2009.

However, as a result of the hunger strike, President Obama delivered a major speech on national security issues in which he promised to appoint two new envoys to deal with the closure of Guantánamo, and also promised to resume releasing prisoners, and as a result, between August and December, he released eleven men from the prison (see here, here, here, here and here).

Six more men have been freed in the last six months, but there are, sadly, no grounds for those who oppose the existence of Guantánamo to sit back and relax, as the release of prisoners has once more ground to a halt, and renewed action is required to put pressure on the administration.

Throughout the period covered by this list, as I described it when I published the previous list, I continued to be “involved in campaigning to resist the age of austerity cynically introduced by the Tory-led government here in the UK, which is being used to wage a disgusting and disgraceful civil war against the poor, the unemployed and the disabled, and whose main aim being to almost entirely destroy the state provision of services.” Specifically, much of my attention was focused on the campaign to save Lewisham Hospital, my local hospital in south east London, and I’m very glad to note that the campaign was successful, providing hope for others working to save their local hospitals and the NHS in general.

As I always explain when I publish these lists, and as I most recently explained in the introduction to my Definitive Guantánamo Prisoner List (updated in March this year), I remain convinced, through detailed research, through comments from insiders with knowledge of Guantánamo, and, most recently, through an analysis of classified military documents released by WikiLeaks, that between 95 and 97 percent of the 779 men and boys imprisoned in total were either completely innocent people, seized as a result of dubious intelligence or sold for bounty payments, or Taliban foot soldiers, recruited to fight an inter-Muslim civil war that began long before the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, and that had nothing to do with al-Qaeda, Osama bin Laden or international terrorism.

The articles I wrote — and, on occasion, the photos I published — between July and December 2013 are listed below, separated into two categories: articles about Guantánamo, and articles about British politics. I hope you find the list useful.

An archive of Guantánamo articles: Part 15, July to December 2013

July 2013

1. Guantánamo, hunger strikes, force-feeding: Shaker Aamer and Other Prisoners Ask US Court to Stop the Force-Feeding and Forced Medication at Guantánamo

1. Guantánamo, hunger strikes, force-feeding: Shaker Aamer and Other Prisoners Ask US Court to Stop the Force-Feeding and Forced Medication at Guantánamo

2. Guantánamo, hunger strikes, force-feeding: Guantánamo Hunger Strike: Nabil Hadjarab Tells Court, “I Will Consider Eating When I See People Leaving This Place”

3. Guantánamo, hunger strikes, force-feeding: In Court Submission, Hunger Striker Ahmed Belbacha Tells Obama, “End the Nightmare that is Guantánamo”

4. Guantánamo, hunger strikes, force-feeding: Justice Department Tells Court that Force-Feeding Guantánamo Hunger Strikers is “Maintaining the Status Quo”

5. Guantánamo, hunger strikes, radio: Radio: On Day 150 of the Hunger Strike at Guantánamo, Andy Worthington Talks to Michael Slate

6. Guantánamo media: Video: Rapper Mos Def (Yasiin Bey) Force-Fed Like Guantánamo Prisoners

7. Guantánamo, hunger strikes, TV: Video: On Day 150 of the Guantánamo Hunger Strike, Andy Worthington Tells RT Why the Prison is a Moral, Legal and Ethical Abomination

8. Guantánamo, hunger strikes, force-feeding: Judge Recognizes Force-Feeding as Torture, But Tells Guantánamo Prisoner Only President Obama Can Deal with the Hunger Strike

9. Guantánamo, hunger strikes, force-feeding: Guantánamo Hunger Striker Abu Wa’el Dhiab: “The Mistreatment Now is More Severe than During Bush”

10. Guantánamo campaigns: For Ramadan, Please Write to the Hunger Striking Prisoners at Guantánamo

11. Bradley Manning: Bradley Manning Trial: No Secrets in WikiLeaks’ Guantánamo Files, Just Evidence of Colossal Incompetence

12. Guantánamo, TV: Video: “Is Guantánamo Forever?” – Andy Worthington on “Inside Out” with Susan Modaress

13. Guantánamo, hunger strikes, force-feeding: From Guantánamo, Hunger Striker Abdelhadi Faraj Describes the Agony of Force-Feeding

14. Deaths at Guantánamo: EXCLUSIVE: The Last Days in the Life of Adnan Latif, Who Died in Guantánamo Last Year

15. Guantánamo lawyers: The Schizophrenic in Guantánamo Whose Lawyers Are Seeking to Have Him Sent Home

16. Shaker Aamer, UK politics, video: Video: Andy Worthington Calls for the Release from Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, Parliament Square, July 18, 2013

17. Guantánamo: “The Grotesque Injustice of Guantánamo: Insiders’ Accounts” – By Video, Andy Worthington Joins Event in Portland, August 1, 2013

August 2013

18. Bradley Manning, TV: Video: Andy Worthington Discusses the Bradley Manning Verdict on RT

19. Guantánamo, torture, video: Video: Culture of Impunity Part Two – Andy Worthington on Bush’s War Crimes, Bradley Manning and Guantánamo

20. Guantánamo, hunger strikes, force-feeding: Shaker Aamer and Other Guantánamo Prisoners Call Force-Feeding Torture, Ask Appeals Court for Help

21. Guantánamo campaigns: GTMO Clock Launched, 75 Days Since Obama’s Promise to Resume Releasing Prisoners from Guantánamo, and Six Months Since Hunger Strike Started

22. Shaker Aamer, UK politics, photos: Photos: Shaker Aamer Protest in London, and His Latest Message from Guantánamo

23. Guantánamo, Periodic Review Boards: Endless Injustice: Newly Announced Guantánamo Review Boards Will Be Toothless Unless Cleared Prisoners Are Freed

24. Guantánamo campaigns: Congratulations to John Grisham for Writing about the Injustice of Guantánamo

25. Guantánamo, hunger strikes: Guantánamo: British Ex-Intelligence Officer On Hunger Strike in Support of Shaker Aamer

September 2013

26. Guantánamo campaigns: GTMO Clock: 100 Days Since President Obama Promised to Resume Releasing Prisoners from Guantánamo, Just Two Men Freed

27. Prisoners released from Guantánamo: Who Are the Two Guantánamo Prisoners Released in Algeria?

28. Life after Guantánamo: Video: Al-Jazeera’s Powerful and Important Documentary, “Life After Guantánamo”

29. Guantánamo: Meet the Guantánamo Prisoner Who Wants to be Prosecuted Rather than Rot in Legal Limbo 30. Deaths at Guantánamo: Remember Adnan Farhan Abdul Latif, Who Died at Guantánamo A Year Ago, Despite Being Cleared for Release

30. Deaths at Guantánamo: Remember Adnan Farhan Abdul Latif, Who Died at Guantánamo A Year Ago, Despite Being Cleared for Release

31. Guantánamo, Bagram, Al-Jazeera: Read My First Article for Al-Jazeera Calling for an End to the Injustice of Guantánamo and Bagram

32. Life after Guantánamo, hunger strikes: Ahmed Zuhair, Long-Term Former Hunger Striker at Guantánamo, Speaks

33. Close Guantánamo: Tom Wilner: President Obama Could Close Guantánamo Tomorrow If He Wanted To

34. Life after Guantánamo: Algeria’s Ongoing Persecution of Former Guantánamo Prisoner Abdul Aziz Naji

35. Omar Khadr: It’s Omar Khadr’s 27th Birthday: He’s Free from Guantánamo, but Still Unjustly Imprisoned in Canada

36. Torture: Andy Worthington Joins Film-Makers and Authors to Judge Contest for Short Films About Torture

37. Life after Guantánamo: Book and Video: Ahmed Errachidi, The Cook Who Became “The General” in Guantánamo

38. Close Guantánamo: Nothing to Celebrate Four Months After Obama’s Promise to Resume Releasing Cleared Prisoners from Guantánamo

39. Shaker Aamer, UK politics: Guantánamo Prisoner Shaker Aamer Complains to UK Tribunal About Intelligence Services’ Role in His Kidnapping and Torture

October 2013

40. Guantánamo, military commissions, Al-Jazeera: Read My Latest Article for Al-Jazeera on Guantánamo’s Military Commissions and the Surveillance State

41. Edward Snowden, surveillance, radio: Andy Worthington Talks to Voice of Russia About the Perils of Blanket Surveillance

42. Guantánamo, Shaker Aamer: In Court, Guantánamo Prisoner Shaker Aamer Asks for Independent Medical Evaluation

43. Guantánamo, Shaker Aamer: Clive Stafford Smith’s Support for an Independent Medical Evaluation for Shaker Aamer in Guantánamo

44. Guantánamo, radio: Radio: Andy Worthington Discusses the Ongoing Injustice of Guantánamo with Chuck Mertz on “This Is Hell”

45. Guantánamo, death row, radio: Reflections on Herman Wallace – and I Discuss Guantánamo on Radio Stations in Portland and Johannesburg

46. Shaker Aamer, photos: Photos: Free Shaker Aamer from Guantánamo, Parliamentary Vigil, October 9, 2013

47. Guantánamo, hunger strikes, force-feeding: Watch the Shocking New Animated Film About the Guantánamo Hunger Strike

48. Guantánamo, Periodic Review Boards: Some Progress on Guantánamo: The Envoy, the Habeas Case and the Periodic Reviews

49. Guantánamo lawyers: Lawyers Seek Release from Guantánamo of Tariq Al-Sawah, an Egyptian Prisoner Who is Very Ill

50. Guantánamo campaigns: Today, As Guantánamo Hunger Strikers Seek Relief in Washington Appeals Court, A US Protestor Will Be Force-Fed Outside

51. Guantánamo, hunger strikes, force-feeding: Although Two Men Weigh 75 Pounds or Less, Guantánamo Prisoner Moath Al-Alwi Says, “We Will Remain on Hunger Strike”

52. Guantánamo interviews: An Interview with Guantánamo Expert Andy Worthington for The Prisma, An Online Multi-Cultural Newspaper

53. Guantánamo media: How the Egyptian Media Has Reported the Story of Tariq Al-Sawah, a Severely Ill Prisoner in Guantánamo

54. Guantánamo campaigns: 150 Days of the GTMO Clock: Despite Obama’s Promise, Just Two out of 86 Cleared Prisoners Freed from Guantánamo

55. Omar Khadr: Lies and Injustice: Canada’s Ongoing Mistreatment of Omar Khadr

56. Guantánamo, hunger strikes, force-feeding: Will Appeals Court Judges Rule that Force-Feeding at Guantánamo Must Stop?

57. Military commissions, torture: Torture: The Elephant in the Room at Guantánamo’s Military Commissions

November 2013

58. Omar Khadr: How Canada Has Hidden the Truth About Omar Khadr: US War Crimes, Institutional Racism and Media Failures

58. Omar Khadr: How Canada Has Hidden the Truth About Omar Khadr: US War Crimes, Institutional Racism and Media Failures

59. Torture, extraordinary rendition: Third Victim of CIA Torture in Poland Granted Victim Status, as European Court of Human Rights Prepares to Hear Evidence

60. Close Guantánamo: Will the End of War in Afghanistan Spur Obama to Close Guantánamo?

61. Guantánamo: Andy Worthington Attends Amnesty Film Screening About Guantánamo in Canterbury, and a Day for Shaker Aamer in Battersea, Nov. 13 and 23

62. Torture, extraordinary rendition: African Human Rights Commission Hears Evidence About CIA Rendition and Torture Case from 2003

63. David Hicks, military commissions: Former Guantánamo Prisoner David Hicks Appeals His 2007 Conviction for Non-Existent War Crime

64. Omar Khadr, military commissions: “He Didn’t Commit a War Crime”: Omar Khadr’s US Lawyer Challenges His Conviction at Guantánamo

65. Close Guantánamo: Will Carl Levin’s Amendments to the NDAA Help President Obama Close Guantánamo?

66. Torture: New Report Condemns Role of Doctors, Psychologists and Psychiatrists as Torturers in Bush’s “War on Terror”

67. Guantánamo, torture, radio: Radio: Andy Worthington Discusses Guantánamo’s 12th Anniversary and Accountability for Torture with Scott Horton and Peter B. Collins

68. Close Guantánamo, Yemenis: Will A Rehabilitation Center Lead to the Release of the Cleared Yemeni Prisoners in Guantánamo?

69. Guantánamo campaigns: Award-Winning Soul Singer Esperanza Spalding Calls for Closure of Guantánamo in New Song, “We Are America”

70. Guantánamo, Shaker Aamer, TV: From Guantánamo, Shaker Aamer Says, “Tell the World the Truth,” as CBS Distorts the Reality of “Life at Gitmo”

71. Close Guantánamo: Senate Passes Bill to Help Close Guantánamo; Now President Obama Must Act

72. Omar Khadr, military commissions: Video: Omar Khadr’s US Lawyer, Sam Morison, Explains Why His Guantánamo War Crimes Conviction is a Disgrace

73. Guantánamo, torture: Penny Lane: What We Learned This Week About Double Agents at Guantánamo

December 2013

74. Palestinians in Guantánamo: Abandoned in Guantánamo: Mohammed Taha Mattan, an Innocent Palestinian

75. Algerians in Guantánamo: Meet the Cleared Algerian Prisoners in Guantánamo Who Fear Being Repatriated

76. Torture, extraordinary rendition: European Court of Human Rights Hears Evidence About CIA Torture Prison in Poland

77. Shaker Aamer: Shaker Aamer’s Latest Words from Guantánamo, and a Parliamentary Meeting on Human Rights Day

78. Torture, extraordinary rendition, radio: Radio: Andy Worthington Discusses the European Court of Human Rights’ Hearing About Poland’s CIA Torture Prison on Voice of Russia

79. Prisoners released from Guantánamo: President Obama Forcibly Repatriates Two Algerians from Guantánamo

80. Guantánamo, Periodic Review Boards, Al-Jazeera: Read My Latest Article for Al-Jazeera About the Problems with Guantánamo’s New Review Boards

81. Guantánamo, hunger strikes, Shaker Aamer: Hunger Strike Resumes at Guantánamo, as Shaker Aamer Loses 30 Pounds in Weight

82. Close Guantánamo: “Close Guantánamo,” Says Prison’s First Commander, Adds That It “Should Never Have Been Opened”

83. Prisoners released from Guantánamo: The Stories of the Two Guantánamo Prisoners Released to Saudi Arabia

84. Omar Khadr, military commissions: Omar Khadr Condemns His Guantánamo Plea Deal, As Canada Concedes He Is Not A “Maximum-Security Threat”

85. Prisoners released from Guantánamo: Two Sudanese Prisoners Released from Guantánamo, 79 Cleared Prisoners Remain

86. Close Guantánamo: How Congress Is Finally Helping President Obama to Release Prisoners from Guantánamo

87. Shaker Aamer: For Christmas, the Reverend Nicholas Mercer Calls for the Release of Shaker Aamer from Guantánamo, Denounces UK Involvement in Torture

88. Guantánamo anniversary: Close Guantánamo Now: Andy Worthington’s US Tour on the 12th Anniversary of the Prison’s Opening, January 2014

An archive of articles about British politics, July to December 2013

July to September 2013

1. Save Lewisham Hospital: Save Lewisham Hospital: Hopes that the Judicial Reviews Will Find Downgrade Plans Unlawful

2. Save Lewisham Hospital: Save Lewisham Hospital: The Submission to the Judicial Review by Dr. Helen Tattersfield, Chair of the CCG

3. Guantánamo, UK politics: Audio: Andy Worthington Speaks about Guantánamo at the “Independence from America” Protest at RAF Menwith Hill, July 4, 2013 4. Save Lewisham Hospital: Lewisham Hospital Saved! Judge Rules Jeremy Hunt’s Downgrade Plans Unlawful

4. Save Lewisham Hospital: Lewisham Hospital Saved! Judge Rules Jeremy Hunt’s Downgrade Plans Unlawful

5. Save Lewisham Hospital, photos: Photos: Victory for the Save Lewisham Hospital Campaign

6. Save Lewisham Hospital: Save Lewisham Hospital: Events to Celebrate the Campaign’s Victory Over Jeremy Hunt

7. UK austerity: Disgusting Tory Britain: UN Housing Expert Attacked After Telling Government to Axe the Bedroom Tax

8. UK austerity: Petition and Protest: Stop This Callous Government’s Sickening War on the Disabled

9. Save Lewisham Hospital, photos: Photos: Save Lewisham Hospital Victory Parade and Rally, September 14, 2013

10. UK austerity: Is the Tide Turning Against the Tories, as Labour Pledges to Scrap the Bedroom Tax and Sack Atos?

11. Save Lewisham Hospital, photos: Photos: The Save Lewisham Hospital Victory Dance, September 27, 2013

October to December 2013

12. UK austerity, photos: Photos: The 10,000 Cuts and Counting Protest in Parliament Square, September 28, 2013

13. UK politics: London Events: Afghan War Protest, and Vigils for Talha Ahsan and Shaker Aamer, October 5-9, 2013

14. Save Lewisham Hospital: Appeal Court Victory for Lewisham Hospital – But Tories Respond with New Legislation to Close Dozens of Hospitals

15. UK austerity: Bonfires of Austerity: Anti-Tory Protests Across the UK on November 5, 2013

16. UK austerity, photos: Photos: Burning Effigies of Tories and Protesting About Austerity and PFI at the Bonfire of Cuts in Lewisham

17. London, housing crisis: Petition: Tell Boris Johnson Not to Approve the Monstrously Inappropriate Development Plans for Convoys Wharf in Deptford

18. Save the NHS: Save the NHS: Demonstrate in London to Save A&Es and Call for More Nurses

19. Save the NHS, photos: Save the NHS and Free Shaker Aamer from Guantánamo: Protest Photos, October and November 2013

20. UK civil liberties: Back in Print: The Battle of the Beanfield, Marking Margaret Thatcher’s Destruction of Britain’s Travellers

21. Save the NHS: Save the NHS: Sign the Petition to Stop Jeremy Hunt Closing Hospitals at Will + Lewisham Hospital Xmas Single

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

July 10, 2014

Canadian Appeals Court Rules That Former Guantánamo Prisoner Omar Khadr Should Be Serving a Youth Sentence

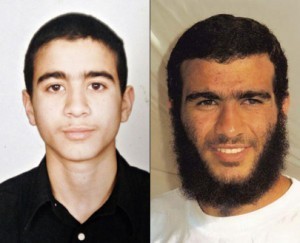

Good news about Guantánamo is rare – whether regarding those still held, or those released — so it was reassuring to hear this week that the Court of Appeal in Alberta, Canada, delivered a major blow to the Canadian government’s efforts to hold former prisoner Omar Khadr in federal prison rather than in a provincial jail. Khadr is serving an eight-year sentence handed down in a plea deal at his trial by military commission in Guantánamo in October 2010, and has been held in federal prisons since his return to Canada, where he was born in 1986.

Good news about Guantánamo is rare – whether regarding those still held, or those released — so it was reassuring to hear this week that the Court of Appeal in Alberta, Canada, delivered a major blow to the Canadian government’s efforts to hold former prisoner Omar Khadr in federal prison rather than in a provincial jail. Khadr is serving an eight-year sentence handed down in a plea deal at his trial by military commission in Guantánamo in October 2010, and has been held in federal prisons since his return to Canada, where he was born in 1986.

The 27-year old was just 15 years old when he was seized in Afghanistan after a firefight with US forces in a compound. He had been taken there, and deposited with some adults, by his father, but on his capture, when he was severely wounded, he was abused in US custody and eventually put forward for a war crimes trial, even though, as a juvenile at the time of the alleged crime, he should have been rehabilitated rather than punished according to an international treaty on the rights of the child signed by the US (and by Canada), even though there is no evidence that the allegation that he threw a grenade that killed a US soldier is true, and even though there is no precedent for claiming that a combat death in an occupied country is a war crime.

Khadr has since explained that he only agreed to the plea deal because he could see no other way of ever getting out of Guantánamo, and last November, via his US civilian lawyer, Sam Morison, he appealed in the US for his conviction to be overturned. In recent years, US appeals court judges have delivered two devastating rulings, overturning two of the only convictions secured in the military commissions, in the cases of Salim Hamdan and Ali Hamza al-Bahlul, on the basis that the war crimes for which the men were convicted were not war crimes at the time the legislation authorizing the commissions was passed — and had, in fact, been invented by Congress.

As Sam Morison told Colin Perkel of The Canadian Press last November, “the main argument turns on whether what Khadr is accused of doing as a 15 year old in Afghanistan was in fact a war crime under American or international law.” Morison explained, “These things weren’t crimes, at least in 2002. They weren’t crimes at the time of the charged conduct. Even if you take the government’s allegations at face value, he still didn’t commit a war crime.”

Perkel added, “The basis for charging [Khadr] for the battlefield death was that he was not in uniform, and was therefore an ‘unprivileged combatant,’” but Morison pointed out, as Perkel put it, that “there is no authority under international law to elevate what Khadr did to the status of a war-crime, which includes such egregious acts as deliberately targeting and killing civilians as the 9/11 terrorists did.”

As Morison described it, “Merely being an unlawful combatant is not by itself a war crime. War crimes still have to be war crimes. It has to do with what you do.” And on this basis, as I explained at the time, “even if Khadr had thrown the grenade that killed US Special Forces Sgt. Christopher Speer, who died in the firefight, it was not a war crime.”

A decision has not yet been taken on Khadr’s US appeal, but in the meantime the government of Stephen Harper has been doing all it can to defend Khadr’s imprisonment in a maximum-security prison since his return to his home country in September 2012.

That false insistence that Khadr should be held in a maximum-security prison was dealt a major blow last August, when Canada’s prison ombudsman Ivan Zinger, the executive director of the independent Office of the Correctional Investigator, said that prison authorities had “ignored favorable information” in “unfairly branding” Khadr as a maximum security inmate.

As I explained in an article at the time:

Zinger wrote, “The OCI has not found any evidence that Mr. Khadr’s behaviour while incarcerated has been problematic and that he could not be safely managed at a lower security level. I recommend that Mr. Khadr’s security classification be reassessed taking into account all available information and the actual level of risk posed by the offender, bearing in mind his sole offence was committed when he was a minor.”

Zinger, who also called Khadr’s case “unique and exceptional,” added that Khadr had “shown no evidence of problematic behaviour while in Canadian custody,” and noted that the US authorities “had categorized him as minimum security” — a particularly pertinent point to highlight the injustice of his treatment in Canada.

In December, Khadr was reclassified as a medium-security risk, and in the new year he was moved from Edmonton, where he was being held as a maximum-security prisoner, to Bowden Correctional Institution, north of Calgary — although Ivan Zinger has continued to criticize the government, complaining in a letter in to the Correctional Service of Canada that Khadr was still “unfairly classified,” even though the authorities had “lowered his risk rating from maximum to medium security.”

As he explained (and as I described it):

[T]he Canadian prison authorities have described Khadr as being “polite, quiet and rule-abiding,” and as someone who “does not espouse the criminal attitudes or code of conduct held by most typical federal offenders,” and, crucially, have also noted that they do not possess any information to suggest that he “espouses attitudes that support terrorist activities or any type of radicalized behaviour.”

However, while Khadr’s prison move was progress, his efforts to get a Canadian judge to recognize that his punishment in his home country was disproportionate fell on deaf ears last October, when, in a court in Edmonton, Justice John Rooke refused to allow his transfer to a provincial jail. As I described it in an article at the time, Khadr’s long-term civilian lawyer, Dennis Edney, had “argued that, as a sentence for murder in Canada, eight years would be regarded as a youth sentence (because a life sentence is mandatory for an adult murder conviction), and therefore Khadr should not have been sent to a maximum security prison.”

However, as I also wrote at the time:

[A]lthough Justice Rooke agreed that eight years was not an adult sentence, he accepted eight years as an appropriate punishment for the other four war crimes that Khadr agreed to in his plea deal. As he wrote in his ruling, “Mr. Khadr’s sentence could have been a single youth sentence and four adult sentences. However, Mr. Khadr obviously cannot be in both an adult provincial facility for adults and a penitentiary at the same time.” He added, as the Toronto Star put it, that “where there is ambiguity, the law dictates that the inmate should serve an adult sentence.”

Omar Khadr’s appeals court victory

Justice Rooke’s ruling has now been struck down by the appeals court. “We have concluded that the chambers judge erred in law in finding that Khadr was properly placed in a federal penitentiary under the ITOA (International Transfer of Offenders Act),” Justices Catherine Fraser, Jack Watson and Myra Bielby ruled, adding, “We conclude that Khadr ought to have been placed in a provincial correctional facility for adults.”

The judges also stated, “In summary, the eight-year sentence imposed on Khadr in the United States could only have been available as a youth sentence under Canadian law, and not an adult one, had the offences been committed in Canada.”

As the Globe and Mail described it, the ruling was “a vindication of the view held by lawyers for Mr. Khadr that the Conservative government went out of its way to treat their client harshly — more harshly than the laws of Canada allow.”

As the judges noted, “While not explicitly stated, it appears that underlying the [Attorney-General of Canada’s] position on this appeal is the view that a cumulative sentence of eight years for the five offences to which Khadr pled guilty is not sufficiently long to reflect the seriousness of the offences.”

The court also noted that, “if the Canadian justice department wished to make that argument,” as the Globe and Mail put it, Khadr “could respond that the US military justice system treated him unfairly — an argument he might well win, for reasons the court took some pains to spell out.”

Partly this involves Khadr’s appeal against his conviction in the US (as mentioned above), but also, as the judges reminded the government, “[t]he legal process under which Khadr was held and the evidence elicited from him have been found to have violated both the Charter and international human rights law” in two rulings from the Supreme Court of Canada delivered before Khadr’s plea deal and his return to Canada from Guantánamo. One involved questioning him without counsel while he was still a teenager (as seen in the documentary film, “You Don’t Like the Truth: 4 Days in Guantánamo“), and the other involved turning over information from the interrogations to the US authorities.

As an aside, the Globe and Mail added that, last fall, Prime Minister Stephen Harper “named a little-known lower-court judge who found Canada nearly blameless in the Khadr affair to the Supreme Court,” but that “the court ruled the appointment of Justice Marc Nadon of the Federal Court of Appeal illegal.”

As the Globe and Mail put it, this week’s appeals court ruling “also brings [Khadr] a step closer to freedom.” Nate Whitling, one of his lawyers, said in an interview that his client now “has the right any time he wishes to apply to a Youth Court judge for early release,” as the newspaper put it, adding, “Without the ruling, his only chance at release would be through the National Parole Board.”

The Canadian Press added that, “[a]s a young offender, Khadr would get an annual review for release before a youth judge,” and noted that Whitling “said the judge could order his release and let him serve out his sentence in the community,” As CBC News described it, he told Rosemary Barton on CBC News Network’s Power & Politics, “A youth sentence carries many advantages under Canadian law. Such sentences are designed to rehabilitate and reintegrate people like Omar in recognition of the fact that the events occurred when they were youths. The law of Canada confirms that youths, like Omar, have diminished culpability for the actions that occur when they are children under the law.”

Whitling also said he “spoke by phone with Khadr after the court decision and, while his client is optimistic about a transfer and eventual application for release, he’s worried he won’t get the chance.”

The Canadian government’s disgraceful decision to appeal the ruling

That was understandable. While Whitling explained that the ruling meant that Khadr “will ask to be moved to jail in Fort Saskatchewan, north east of Edmonton, to be closer to his Edmonton lawyers,” within three hours of the ruling, Public Safety Minister Steven Blaney spoke out, saying that a youth sentence was “not appropriate” for Khadr, and stating that the government will appeal to the Supreme Court.

Blaney wheeled out the government’s usual statement about Khadr’s US conviction — that Khadr “pleaded guilty to heinous crimes,” and that the government has “vigorously defended against any attempt to lessen his punishment for these crimes” — and added, “That is why the government of Canada will appeal this decision and seek a stay to ensure that he stays in federal prison — where he belongs.”

Dennis Edney explained why the appeals court ruling was important. “We are pleased to get Omar Khadr out of the hands of the Harper government,” he said, adding, “This is a long series of judgments against this intractable, hostile government,” which “would rather pander to politics than to apply the rule of law fairly to each and every Canadian citizen.”

Edney also pointed out, “This government chose to misinterpret the International Transfer of Offenders Act and place Omar in a maximum security prison, where he spent the first seven months in solitary confinement, instead of treating him as a youth as required under both Canadian and international law.”

On CBC News, Françoise Boivin of the New Democratic Party (NDP) said the government should respect the appeals court ruling, and “should think twice” about appealing to the Supreme Court. “The Conservative government is starting to cost us a lot of money in all their court challenges that they seem to lose one after the other,” she said.

That is certainly true, and I hope the Harper government is listening — not only because it loses every argument it tries to win in Omar Khadr’s case, and not only because it is wantonly spending taxpayers’ money doing so, but above all because its position is wrong, and fundamentally indefensible. It would be hard to conceive of a manner in which any other Canadian citizen has been treated as disdainfully by their government as Omar Khadr, and yet the lies and the racism of the government continue unabated, aided by unjustifiable initiatives like the one launched by Canada’s Welland Tribune in the wake of the appeals court decision — a poll asking readers, “Should Omar Khadr be allowed to transfer to a provincial jail?” as though, absurdly, the opinions of unqualified civilians regarding the law (and, specifically, the International Transfer of Offenders Act) are as valid as those of the judges who made the ruling.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

July 9, 2014

The 9/11 Trial at Guantánamo: The Dark Farce Continues

I wrote the following article for the “Close Guantánamo” website, which I established in January 2012 with US attorney Tom Wilner. Please join us – just an email address is required to be counted amongst those opposed to the ongoing existence of Guantánamo, and to receive updates of our activities by email.

I wrote the following article for the “Close Guantánamo” website, which I established in January 2012 with US attorney Tom Wilner. Please join us – just an email address is required to be counted amongst those opposed to the ongoing existence of Guantánamo, and to receive updates of our activities by email.

In two articles — this one and another to follow soon — I’ll be providing updates about the military commissions at Guantánamo, the system of trials that the Bush administration dragged from the US history books in November 2001 with the intention of trying, convicting and executing alleged terrorists without the safeguards provided in federal court trials, and without the normal prohibitions against the use of information derived through torture.

Notoriously, the first version of the commissions revived by the Bush administration collapsed in June 2006, when, in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, the Supreme Court ruled that the commission system lacked “the power to proceed because its structures and procedures violate both the Uniform Code of Military Justice and the four Geneva Conventions signed in 1949.”

Nevertheless, Congress subsequently revived the commissions, in the fall of 2006, and, although President Obama briefly suspended them when he took office in 2009, they were revived by Congress for a second time in the fall of 2009.

Despite this, just eight cases have been decided since the “war on terror” began — three under George W. Bush (David Hicks in March 2007, Salim Hamdan in August 2008 and Ali Hamza al-Bahlul in November 2008) and five under Barack Obama (Ibrahim al-Qosi in July 2010, Omar Khadr in October 2010, Noor Uthman Muhammed in February 2011, Majid Khan in February 2012 and Ahmed al-Darbi in February 2014). Of the eight, six involved plea deals, and what credibility the commissions had was shattered when the only two convictions that involved actual trials — those of Salim Hamdan and Ali Hamza al-Bahlul — were overturned on appeal in October 2012 and January 2013 on the basis that the war crimes for which they were convicted were not internationally recognized and had been invented by Congress. Further information about all these cases can be found in an article I put together in March, entitled, “The Full List of Prisoners Charged in the Military Commissions at Guantánamo.”

The government appealed in the case of Ali Hamza al-Bahlul, and a hearing took place last October, although no ruling has yet been taken by the court. However, the Hamdan and al-Bahlul rulings have already led to the government abandoning plans to proceed with any trials other than the ones currently taking place — for Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and four other men accused of involvement in the 9/11 attacks; for Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri, accused of masterminding the attack on the USS Cole in 2000; and for Abd al-Hadi al-Iraqi, one of the last men to arrive at Guantánamo, in April 2007.

All of these men were held in CIA “black sites” before their transfer to Guantánamo, where, as I explained in my last update about the commissions in March, “they were subjected to torture — which, of course, makes a fair and open trial improbable, and has led to a protracted game of cat and mouse as the government tries to suppress all mention of torture, while the defense teams try to expose it.”

In this article, I’ll provide updates on the 9/11 trial, and in a second article to follow I will look at developments in the case of Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri and the arraignment of Abd al-Hadi al-Iraqi.

Hearings generally take place every three months or so, and in 2013 defense lawyers in the 9/11 trial spent much of their time challenging a protective order, issued in December 2012 by the chief judge of the commissions, Col. James L. Pohl, accepting calls by prosecutors for material provided to the defense (through the process known as “discovery”) to be subjected to a protective order, because it “contains information that, if disseminated without authority, could pose a threat to public safety and national security and could implicate the privacy interests of the Accused and third parties.”

As I explained in October 2013:

[L]awyers for the prisoners argue that the protective order violates the UN Convention Against Torture, specifically through Judge Pohl’s acceptance, as Katherine Hawkins [a lawyer and researcher] put it, that “the defendants’ ‘observations and experiences’ of torture at CIA black sites are classified.” The men’s lawyers point out that the ban “violates the Convention Against Torture’s requirement that victims of torture have ‘a right to complain’ to authorities in the countries where they are tortured, and makes the commission into ‘a co-conspirator in hiding evidence of war crimes.’”

In December, at the last hearing of the year, Ramzi bin al-Shibh, one of the five alleged 9/11 co-conspirators, “was ejected twice from the courtroom for interruptions — in the first instance shouting, ‘This is torture! You have to stop the sleep deprivation and the noises,’” as I explained in an article in March. I added, “This led to questions about his mental competency, but these had not been addressed by January 31 this year, because he refused to talk to a mental health board whose members told the judge that they therefore didn’t know if he was fit to stand trial.” As a result, Judge Pohl was obliged to put off the next round of hearings, scheduled for February, and these did not take place until April, when bin al-Shibh’s competency was once more under scrutiny.

The strange case of the FBI investigation into the 9/11 defense team

However, bin al-Shibh’s mental state was almost immediately overshadowed by what appeared to be a fresh scandal, when, on April 14, defense lawyers “accused the FBI in open court of trying to turn a defense team security officer into a secret informant,” as the Miami Herald described it, prompting Judge Pohl to immediately call for a recess.

Jim Harrington, bin al-Shibh’s civilian defense attorney, said that two FBI agents had visited the home of his team’s Defense Security Officer, seeking information about who had provided media outlets with a statement produced by Khalid Sheikh Mohammed that had surfaced in January.

Defense Security Officers, who work for outside contractors, “have Top Secret security clearances,” as the Miami Herald put it, and are assigned to “guide team members, both lawyers and analysts, on what information should be blacked out in court filings — and what information can be released as unclassified.”

Jim Harrington noted that, when approached by the FBI, the Defense Security Officer — who, he said, had subsequently been suspended from the case — was made to “sign a non-disclosure agreement that appeared to draw him into a continuing informant relationship.”

In an emergency defense motion, lawyers stated, “Apparently as part of its litigation strategy,the government has created what appears to be a confidential informant relationship with a member of Mr. bin al Shibh’s defense team, and interrogated him about the activities of all defense teams. The implications of this intrusion into the defense camp are staggering. The most immediate implication, however, is that all defense teams have a potential conflict of interest between their loyalty to their clients and their interest in demonstrating their innocence to FBI investigators.”

On April 15, Judge Pohl, brushing aside the bin al-Shibh competency question by stating that he was “competent until somebody argued otherwise” (in the Miami Herald‘s words), “ordered everyone working for the 9/11 defense teams to notify their lead lawyer if US government agencies, including the FBI, had contacted them,” and “also sought a proposal from defense lawyers of what evidence he should gather, which people he should question.” When asked if he knew about the investigation, the chief prosecutor, Army Brig. Gen. Mark Martins, said, “No, we were not.”

Bizarrely, it transpired that the statement by KSM wasn’t even regarded as case evidence, and had been declared unclassified by the CIA, although an emergency prosecution filing at the end of February revealed that “prosecutors treated two copies as court evidence after defense lawyers handed them the document” in December.

On April 17, Brig. Gen. Martins announced that Justice Department lawyer Fernando Campoamor-Sánchez had been appointed as Special Trial Counsel, and was given until April 21 “to explain to the judge, in a ‘full factual submission,’ what he [had] been able to discover about what the FBI [was] doing.”

For his part, Judge Pohl acknowledged what appeared to be an FBI investigation. “Right now,” he said, “it appears from the state of the current record” that “there is some type of investigation by the FBI into Mr. Mohammad’s team.”

On April 21, Campoamor-Sánchez confirmed that the FBI was conducting an investigation that was related to the 9/11 trial, but was unrelated to the release of KSM’s statement. In a nine-page filing to the court, he wrote, as the Miami Herald described it, that the government “specifically kept Sept. 11 trial prosecutors in the dark” about what he described as a “preliminary investigation.”

The Herald added that the filing “does not make clear what the FBI is investigating.” Instead, Campoamor-Sánchez stated that he had given the judge “a second, classified document” in which he described “the nature of the actual FBI Preliminary Investigation being conducted.” He added that any wider disclosure would “jeopardize an ongoing FBI criminal investigation,” and explained in a footnote that the trigger for apreliminary investigation was “[a]ny ‘allegation or information’ indicative of possible criminal activity or threats to the national security.”

Campoamor-Sánchez asked Judge Pohl for an additional 30 days to find out more about the investigation, and the judge agreed, adjourned the proceedings until June. When the court reconvened on June 16, Campoamor-Sánchez confidently stated that “there is not any informant or mole in the defense camp,” adding that the FBI’s activity “created no conflict of interest because the agents weren’t investigating defense attorneys, only questioning their support staff.” He also stated that the defense lawyers “should trust in the prosecution argument supported by a sworn FBI affidavit that the investigation that kicked off the controversy by questioning defense team members was closed.”

The defense lawyers were not entirely reassured. “I do have a reasonable fear. I am trimming my sails. I am pulling my punches,” David Nevin, one of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed’s lawyers, told the judge. The lawyers explained that they had uncovered four separate episodes of the FBI questioning staff members, as part of two investigations which they were now being asked to believe were closed, even though they had only found out about them because the man questioned in April, Dante James, the classification specialist on the Bin al-Shibh team, had told them about it. The others, as the Miami Herald explained, were “a linguist on the team of the alleged mastermind, Khalid Sheik[h] Mohammed, in January 2013,” and, in November, “two former federal law enforcement officers working as civilian investigators” on the teams of Ramzi bin al-Shibh and Mustafa al-Hawsawi.

While the majority of the defense lawyers told Judge Pohl that uncovering the FBI investigation had created “suspicion and uncertainty in the 9/11 defense teams,” one lawyer, Walter Ruiz, said he had found no conflict of interest. Ruiz represents Mustafa al-Hawsawi, a Saudi captured with KSM in Pakistan in March 2003, who is accused of providing financial assistance and organizing travel arrangements for some of the 9/11 hijackers, and he explained that, although one of the two civilian investigators questioned by the FBI was his civilian investigator, Thomas Gilhool, “he had discussed what the FBI had done with both Gilhool and Hawsawi and concluded that, for his part, no conflict of interest exists.”

Furthermore, he and his client were seeking a separate trial because al-Hawsawi is “not interested in more delays.” Ruiz said that a separate trial would “let him more swiftly litigate several issues,” in particular the conditions at Camp 7, where the “high-value detainees” are held. He called it “pseudo isolation, which in long-term detention is sometimes considered torture.” He also criticized the lack of family contact and what he described as the inadequate provision of religious facilities, and called the manner in which the men have been held “tremendously embarrassing to our armed forces.”

What will be the impact of the Senate torture report on the 9/11 trial?

While the circumstances in which the FBI investigation was discovered cast another shadow on the credibility of the commissions, as well as providing another delay of many months in the seemingly interminable pre-trial hearings, it was not the only problem to surface in the last few months.

On April 2, James Connell, one of the lawyers for Ali Abd al-Aziz Ali (aka Ammar al-Baluchi), one of the five alleged 9/11 co-conspirators, was “trying to get a copy of the secret Senate report on CIA interrogations that has caused a bitter rift between the agency and Congress,” as the Miami Herald described it. Connell explained that “the report and related documents contain information about the torture of his client.” The 6,300-page report, commissioned by the Senate Committee on Intelligence, took four years to complete and was delivered to the committee in December 2012, but it has not yet been released, as all the parties involved — and particularly the CIA — argue about how much of it should remain classified.

Connell’s efforts have so far yielded no results, but on May 22 the Miami Herald reported that his interest in the torture report, and its repercussions for the 9/11 trial, were shared by Sen. Carl Levin (D-Mich.), the chair of the powerful Senate Armed Services Committee, and Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.), the chair of the Senate Intelligence Committee.

In a letter to President Obama, dated January 6, they wrote, “We write to urge that you direct all appropriate action to address the ongoing delay in the military commission trial of Khalid Shaykh Mohammad [sic] (KSM) and four other detainees being prosecuted at Guantánamo in connection with the 9/11 terrorist attacks.” They added, “Much of the delay is related to the continued classification of the information concerning the now defunct CIA Detention Interrogation Program.”

As will be discussed in detail in my forthcoming second article providing updates about the military commissions, on April 17 Judge Pohl ordered the CIA to provide details of the “black site” detention — “names, dates and places” — to Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri’s lawyers. The judge explained that the lawyers “are entitled to the information to prepare Nashiri’s defense.” Khalid Sheikh Mohammed’s lawyers have asked Judge Pohl to do the same in their client’s case, but progress is slow, as the CIA is still resisting Judge Pohl’s order in al-Nashiri’s case.

However, the lawyers’ concerns were echoed by Sens. Levin and Feinstein in their letter, in which they stated that it was urgent that the relevant information is declassified, because “the delay is further undermining the reputation of the military commissions with the American public and our friends and allies overseas.” They added, “The continued classification of information also interferes with our country’s long-delayed, but important efforts to publicly shine a light on the misguided CIA program you rightfully ended almost five years ago.”

The senators also said that if the administration did not resolve these issues, the 9/11 trial should be moved to a federal court — where, of course, it was supposed to take place, after an announcement by Attorney General Eric Holder in November 2009, until critics began a backlash and President Obama backed down.

In a letter dated February 10, White House Counsel Kathryn Ruemmler responded by stating that President Obama shares the senators’ commitment to “facilitat[e] the prosecution of those charged in connection with the 9/11″ attacks, but added that “declassification decisions, even with respect to historical legacy programs, are fact-based and must be made with the utmost sensitivity to our national security.”

Ruemmler also noted that the president and CIA director John Brennan “are committed to working with you and others on your respective committees to ensure that information regarding the RDI [rendition, detention and interrogation] program is declassified, consistent with our national security interests.”

Accurately, I believe, the Miami Herald described the Levin-Feinstein letter as “the latest turn in what’s erupted into an extraordinary behind-the-scenes battle between the CIA and its overseers in Congress over the Senate Intelligence Committee’s $40 million investigation into the interrogation program,” although the White House’s careful response showed only that the brakes are still on regarding the report’s eventual release.

And in the meantime, at Guantánamo, justice, in the cases of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and the four other men accused of involvement in the 9/11 attacks, appears as elusive as ever.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

July 6, 2014

The Rule of Law Oral History Project: How the Guantánamo Prisoners Have Been Failed by All Three Branches of the US Government

Two days ago I posted excerpts from an interview about Guantánamo and my work that I undertook as part of The Rule of Law Oral History Project, a five-year project run by the Columbia Center for Oral History at Columbia University Library in New York, which was completed at the end of last year.

Two days ago I posted excerpts from an interview about Guantánamo and my work that I undertook as part of The Rule of Law Oral History Project, a five-year project run by the Columbia Center for Oral History at Columbia University Library in New York, which was completed at the end of last year.

In this follow-up article I’m posting further excerpts from my interview — with Anne McClintock, Simone de Beauvoir Professor of English and Women’s and Gender Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison — although, as in the previous article, I also encourage anyone who is interested in the story of Guantánamo and the “war on terror” — and the struggle against the death penalty in the US — to visit the website of The Rule of Law Oral History Project, and to check out all 43 interviews, with, to name but a few, retired Justice John Paul Stevens of the Supreme Court; A. Raymond Randolph, Senior Judge in the US Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit; Ricardo M. Urbina and James Robertson, retired Senior Judges in the US District Court for the District of Columbia; Lawrence B. Wilkerson, Former Chief of Staff to Secretary of State Colin Powell; Joseph P. Hoar, Former Commander-in-Chief, United States Central Command (CENTCOM); former military commission prosecutor V. Stuart Couch and former chief prosecutor Morris D. Davis; Brittain Mallow, Commander, Criminal Investigation Task Force, and Mark Fallon, Deputy Commander, Criminal Investigation Task Force. Also included are interviews with former prisoners, lawyers for the men, psychologists and a psychiatrist, journalists and other relevant individuals.

In this second excerpt from the interview, I explain how, at the time Anne and I were talking (in June 2012), the situation for the Guantánamo prisoners had reached a new low point, as the Supreme Court had just failed to take up any of the appeals submitted by seven of the men still held. These all related to the men’s habeas corpus petitions, and the shameful situation whereby, for ideological reasons, primarily related to fearmongering, a handful of appeals court judges, in the D.C. Circuit Court, had effectively ordered District Court judges to stop granting habeas corpus petitions submitted by the prisoners (after the prisoners secured 38 victories), by demanding that anything that purported to be evidence submitted by the government — however risible — be given the presumption of accuracy unless it could be specifically refuted.

For the Supreme Court decision, see my articles, “The Supreme Court Abandons the Guantánamo Prisoners” and “Meet the Seven Guantánamo Prisoners Whose Appeals Were Turned Down by the Supreme Court,” as well as my appearances on Democracy Now! and RT, and for the political maneuvering of the D.C. Circuit Court, see “As Judges Kill Off Habeas Corpus for the Guantánamo Prisoners, Will the Supreme Court Act?” and “Lawyer Laments the Death of Habeas Corpus for the Guantánamo Prisoners.”

With inaction for the president, and restrictions on the release of prisoners that were raised by cynical lawmakers, June 2012 represented the point at which it could be inarguably stated that the Guantánamo prisoners had been failed by all three branches of the US government. This was something that became abundantly clear just three months later, when Adnan Farhan Abdul Latif, a Yemeni prisoner with mental health problems, who had been cleared for release under President Bush and President Obama, died at the prison, allegedly by committing suicide. For my analysis, see “Obama, the Courts and Congress Are All Responsible for the Latest Death at Guantánamo.”

The excerpt below comes from Day 2 of my three-day interview, and is from pages 43 to 59 of the transcript, which is available here. Please note that, in the passages below, I have added a few links that are particularly useful for readers wanting to know more.

Excerpt from The Rule of Law Oral History Project interview with Andy Worthington

Conducted by Anne McClintock

Q: I wonder if we could pick up some of the threads from yesterday. Perhaps we could start with last week on June 11 [2012]. It seems to me that something fairly momentous happened, a critical legal turning point for the prisoners, and I wondered if you could perhaps recap what happened and what that might mean for the prisoners.

Worthington: Yes. There have always been—not always. Initially, there was only one route out of Guantánamo, and that was diplomatic arrangements between the Bush administration and the home countries of the prisoners who were held. Now, from almost the beginning, in fact, from the beginning, from day one, a handful of lawyers who realized that something terribly wrong had taken place started to try to get habeas corpus rights for the Guantánamo prisoners. It took two and a half years for that process to lead to the Supreme Court ruling in Rasul v. Bush, in June 2004, that the prisoners did have habeas corpus rights.

Now what that did, hugely importantly—what that did was it opened the prison to visiting lawyers. It broke the spell of silence that had enshrouded Guantánamo for all that time, where, effectively, we found out afterwards, they were torturing people with impunity. And they stopped, at least in the sense of the torture program. They didn’t call it that, but that’s what it was. They stopped. As soon as they were going to be subjected to outside scrutiny, then they changed the way they behaved in that sense.

They fought back with the help of a compliant Congress, which twice passed legislation that included provisions designed to strip the prisoners of the habeas corpus rights that the Supreme Court had given them. So the Detainee Treatment Act in 2005 and the Military Commissions Act in 2006. It took until June 2008 for the Supreme Court to revisit its ruling and to rule—I think this is important—that the habeas-stripping provisions that Congress had passed in those two acts were illegal, were unconstitutional rather, and to insist that the prisoners had constitutionally guaranteed habeas corpus rights.

Now that’s a huge ruling, but what they didn’t do, what the justices didn’t do, was stipulate exactly what the standards were to justify the ongoing detention of prisoners when they submitted their habeas corpus petitions to the District Court in Washington, D.C.

So the judges of the District Court got together. They decided what the standards were and they started reviewing the habeas corpus petitions of the men. Something over two dozen of those cases were won by the prisoners.

Q: And that was when, Andy?

Worthington: Actually, I think the figures are different than that. Thirty-eight cases? I can’t remember the exact numbers [Note: It was 38 cases]. A majority of the cases were won by the prisoners from October 2008 until the summer of 2010. It led to the release of over two-dozen prisoners, so the only people who left Guantánamo through any legal means were the ones who had their habeas corpus petitions granted and were released from Guantánamo. In the summer of 2010, in particular, the D.C. Circuit Court, so the court of appeals in Washington, the District of Columbia, started fighting back in earnest. Actually, in January 2010, they issued a ruling claiming that there should be no constraint on the president’s wartime powers, which pretty much everyone disagreed with. The alarming figure was Judge A. Raymond Randolph.

Now he’s a senior judge in the D.C. Circuit Court. He had approved every piece of legislation under Bush relating to Guantánamo that was subsequently overturned by the Supreme Court. But he and some of his fellow judges decided that the rules were too lax; that what the District Court judges were doing was releasing prisoners by granting their habeas corpus petitions. They decided they were doing that because they weren’t approaching the alleged evidence in the right way, so they imposed restrictions on the District Court’s ability to have any kind of objective analysis of the evidence. [A] number of rulings have been issued and have ended up, towards the end of 2011, with a ruling in which an intelligence report produced in the field—which pretty much everyone would say is going to be imprecise, needs to be something that is open to questioning as to its reliability—they basically said that it should be trusted; that all government evidence should be presumptively regarded as accurate, unless the prisoners can prove that it isn’t.

Q: And also, presumably, some of those could have been extracted under coercive conditions.

Worthington: Well, the problem isn’t just with—this isn’t so much to do with the government’s intelligence report, although the intelligence reports produced in the field would be based on interrogations shortly after capture, when it’s extremely unlikely that people weren’t being treated coercively. Also, it would be based on information that could have been extracted from the Afghans or the Pakistanis, who were holding these men before they were handed over to U.S. custody.

So yes, it’s extremely unreliable. But it’s not the major problem with the evidence. That’s part of it. The other main problem with the evidence is that the statements that the U.S. government relies on that were produced by the prisoners themselves, or by their fellow prisoners in Guantánamo or by other prisoners in other facilities, run by or on behalf of the United States, where people were also being interrogated—there are profound problems with that evidence, either because people were tortured or otherwise coerced; because people were bribed, in some cases with better living conditions; and, in some cases, mentally ill people were bribed or coerced.

Q: And in many cases implicating, so there was a kind of proliferation of the naming of names.

Worthington: Yes. I think the key to how people were coming up with this information is to bear in mind that there was what was called the “family album.” There were albums of photographs of prisoners, or of people who were at-large and suspects. There were always these photo albums and people were shown the photo albums. “Who is this man? You know this man. When did you last see this man? When did you last have dinner with this man? When were you last buying surface-to-air missiles from this man?” All of this is going on.

Q: During the interrogation process.

Worthington: Everywhere. There was a man who was held in the Jordanian prison, where the Jordanians were holding prisoners for the United States government and torturing them. He said every day that’s what it was. Every day was photos—”Who’s this? Who’s that? Who’s this?” People he didn’t know. You have to invent a story, unless you’re one of those people who doesn’t crack, in which case terrible things happen to you.

Q: Well, we know that [John S.] McCain [III], when he was being tortured, gave the names of the Green Bay Packers, the football team.

Worthington: Well, all of it is unreliable.

Q: Right. Right.

Worthington: So the decision by the Supreme Court not to accept appeals by seven Guantánamo prisoners—it’s the second year that they haven’t accepted any appeals—

Q: This was last week, you mean.

Worthington: Yes. This was last week.

Q: June 11, was it?