Andy Worthington's Blog, page 119

March 14, 2014

Long-Cleared Algerian Prisoner Ahmed Belbacha Released from Guantánamo

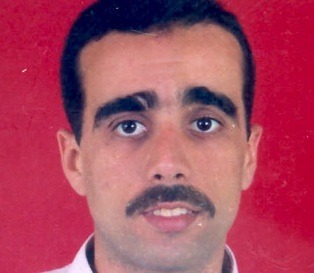

I’m delighted to report that Ahmed Belbacha, an Algerian prisoner, has been released from Guantánamo. It’s always good news when a prisoner is released, and in Ahmed Belbacha’s case it is particularly reassuring, as I — and many other people around the world — have been following his case closely for many years. I first wrote about him in 2006, for my book The Guantánamo Files, and my first article mentioning him was back in June 2007. I have written about his case, and called for his release, on many occasions since.

I’m delighted to report that Ahmed Belbacha, an Algerian prisoner, has been released from Guantánamo. It’s always good news when a prisoner is released, and in Ahmed Belbacha’s case it is particularly reassuring, as I — and many other people around the world — have been following his case closely for many years. I first wrote about him in 2006, for my book The Guantánamo Files, and my first article mentioning him was back in June 2007. I have written about his case, and called for his release, on many occasions since.

Ahmed was cleared for release from Guantánamo twice — by a military review board under the Bush administration in February 2007, and by President Obama’s high-level, inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force, appointed by the president shortly after taking office in 2009.

Nevertheless, he was terrified of returning home, and, from 2007 onwards, tried to prevent his forced repatriation in the US courts. This seems to have annoyed the authorities in Algeria, as, in 2009, he was tried and sentenced in absentia, receiving a 20-year sentence for membership of a foreign terrorist group abroad. As his lawyers at Reprieve noted, despite repeated requests, no evidence was produced to support the conviction.

Although the US courts eventually refused to accept calls by Ahmed and other prisoners to prevent their enforced repatriation — or their transfer to other countries — the US authorities were concerned about Ahmed’s in absentia conviction as long ago as 2010, when they “expressed some concern” about repatriating him, as the Washington Post reported.

Fortunately, as Ahmed’s lawyers at Reprieve noted on his release, “The transfer is in accordance with his and his family’s wishes, and marks the end of a dreadful 12 years for Mr. Belbacha.” Reprieve also noted that they expect that “the efforts so far made by the Algerian authorities to end this injustice will now continue, so that Ahmed can return to his family as soon as possible,” adding, “His parents have been deeply worried and confused by the continued detention of their son, and Ahmed has repeatedly told his lawyers that his main concern is now to get home and help his brothers to look after them.” Sadly, during his 12 years of imprisonment without charge or trial, his grandmother died without him having had the opportunity to speak to her.

Reprieve’s lawyers also noted that they “have met with representatives of the Algerian government, and have been assured that Ahmed will be treated fairly and humanely on his return to the country” — worries based not only on his in absentia conviction, but also on the fact that the intelligence services can and do hold people (including returned Guantánamo prisoners) for 12 days on their return, and also because of the harassment to which other released Algerians have been subjected — and, in the case of Abdul Aziz Naji, returned in July 2010, the three-year sentence he received after another dubious trial.

Ahmed’s story

A gentle character, and just 5′ 3″ tall, Ahmed is 44 years old, but was just 32 when he was first seized and sold to the US military in Pakistan. He is one of eleven children, from a middle class family, and after high school he trained as an accountant for Algeria’s national oil company, Sonatrach, where he was also a star player on the company’s well-known football team. After undertaking his national service, he returned to Sonatrach, working in its commercial division.

However, as his lawyers at Reprieve explained, “his life was dramatically changed by the events of the civil war, when his army service and role at Sonatrach brought him to the attention of local militant Islamic groups.” After receiving threats against himself, and his family, Ahmed decided to seek asylum in Britain, travelling via France, and heading for Bournemouth, where he worked in a launderette, and then at the Swallow Royal Hotel. He was there during the 1999 Labour Party Conference, and was in charge of cleaning the room of John Prescott, the Deputy Prime Minister, a job he did so well that Prescott left him a thank you note and a tip.

Nevertheless, Ahmed was unsuccessful in his asylum application, and was turn down in 2001. He appealed, but, as Reprieve described it, “the procedure dragged on for months,” and, because he “was having increasing difficulty finding steady work and greatly feared deportation,” he “decided to travel to Pakistan, where he could take advantage of free educational programs to study the Koran,” in the hope that, after six months away, the UK economy “would be better and his job prospects would improve.”

Ahmed and a friend flew to Pakistan in June 2001, and, after some time there, decided to pay a visit to Afghanistan, staying for a while in an Algerian guest house.

While he was there, however, the 9/11 attacks took place, and then the US-led invasion began. As Reprieve noted, when the Northern Alliance began rounding up Arabs, he realised it was no longer safe in Afghanistan, and, like many others, travelled to Pakistan through the mountains, hoping to reach Islamabad and to fly home.

Instead, he “was seized in a small village and taken briefly to a border prison,” and “was then transferred to another prison six or seven hours’ drive away, where he was held for about two weeks and interrogated by the CIA.” He was then taken to Kandahar, to the US military’s first major prison in Afghanistan, where abuse was widespread, and in March 2002 he was flown to Guantánamo, where he endured twelve years of abuse and injustice.

Ahmed’s release

Last year, Ahmed responded to the ongoing injustice of Guantánamo by joining the prison-wide hunger strike that reminded the world of the men’s plight, and forced President Obama to promise to resume releasing prisoners.

It is fair to say, I believe, that without the majority of the men embarking on a prison-wide hunger strike, Ahmed might still have been waiting in Guantánamo for his release.

As Reprieve added in their press release, “Ahmed now needs to be returned to the safety and security of his home, as soon as possible, so that he can start to recover from the dreadful experience of the last 12 years in prison.”

Commenting on Ahmed’s release, Polly Rossdale, the deputy director of Reprieve’s Guantánamo team, said, “Ahmed’s last 12 years show how dangerous it is for us all if the time-tested procedures of open justice are disregarded. The US Government was happy to arrest and detain Ahmed for over a decade, without ever giving him a chance to answer their unfounded accusations. We applaud the efforts now being made — however late they come — to right some small portion of this wrong, and get prisoners home who should never have been forced to endure such a nightmare in the first place.”

Cliff Sloan, the State Department’s special envoy for the closure of Guantánamo, also issued a statement after Ahmed’s release. “We greatly appreciate the close cooperation of the government of Algeria in receiving one of its nationals from Guantánamo,” he stated, adding, “Today’s transfer represents another step in our ongoing efforts to close the detention facility at Guantánamo.”

Paul Lewis, Cliff Sloan’s counterpart at the Pentagon, added, “The transfer of this Algerian national from Guantánamo Bay is another step forward in our effort to reduce the population and close the detention facility responsibly,” adding, “I would like to thank Special Envoy Sloan’s office and the many others who worked on this transfer. Their work is greatly appreciated.”

Although Ahmed Belbacha has now been released, 75 other men cleared for release by the Guantánamo Review Task Force — 55 Yemenis and 20 men from other countries — are still held. Their release is just as urgent as Ahmed Belbacha’s, and I hope to hear soon that some of them have also been freed. The administration needs to realize as soon as possible that endless prevarication on releasing the Yemenis — because of security fears about their homeland — is both counter-productive and cruel. After all, what is worse than indefinite detention without charge or trial? The answer? Indefinite detention without charge or trial after a presidential task force approved your release.

It is four years and two months since these men were told that the US no longer wished to hold them, and that arrangements were being made for their transfer. How much longer must they wait?

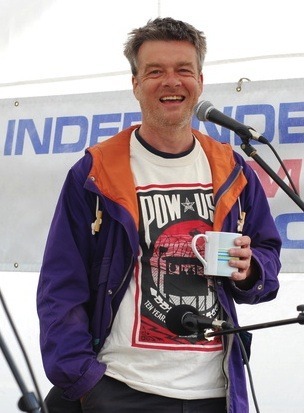

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

See the following for articles about the 142 prisoners released from Guantánamo from June 2007 to January 2009, and the 82 prisoners released from February 2009 to December 31, 2013, whose stories are covered in more detail than is available anywhere else –- either in print or on the Internet –- although many of them, of course, are also covered in The Guantánamo Files: June 2007 –- 2 Tunisians, 4 Yemenis (here, here and here); July 2007 –- 16 Saudis; August 2007 –- 1 Bahraini, 5 Afghans; September 2007 –- 16 Saudis; September 2007 –- 1 Mauritanian; September 2007 –- 1 Libyan, 1 Yemeni, 6 Afghans; November 2007 –- 3 Jordanians, 8 Afghans; November 2007 –- 14 Saudis; December 2007 –- 2 Sudanese; December 2007 –- 13 Afghans (here and here); December 2007 –- 3 British residents; December 2007 –- 10 Saudis; May 2008 –- 3 Sudanese, 1 Moroccan, 5 Afghans (here, here and here); July 2008 –- 2 Algerians; July 2008 –- 1 Qatari, 1 United Arab Emirati, 1 Afghan; August 2008 –- 2 Algerians; September 2008 –- 1 Pakistani, 2 Afghans (here and here); September 2008 –- 1 Sudanese, 1 Algerian; November 2008 –- 1 Kazakh, 1 Somali, 1 Tajik; November 2008 –- 2 Algerians; November 2008 –- 1 Yemeni (Salim Hamdan) repatriated to serve out the last month of his sentence; December 2008 –- 3 Bosnian Algerians; January 2009 –- 1 Afghan, 1 Algerian, 4 Iraqis; February 2009 — 1 British resident (Binyam Mohamed); May 2009 —1 Bosnian Algerian (Lakhdar Boumediene); June 2009 — 1 Chadian (Mohammed El-Gharani), 4 Uighurs to Bermuda, 1 Iraqi, 3 Saudis (here and here); August 2009 — 1 Afghan (Mohamed Jawad), 2 Syrians to Portugal; September 2009 — 1 Yemeni, 2 Uzbeks to Ireland (here and here); October 2009 — 1 Kuwaiti, 1 prisoner of undisclosed nationality to Belgium; October 2009 — 6 Uighurs to Palau; November 2009 — 1 Bosnian Algerian to France, 1 unidentified Palestinian to Hungary, 2 Tunisians to Italian custody; December 2009 — 1 Kuwaiti (Fouad al-Rabiah); December 2009 — 2 Somalis, 4 Afghans, 6 Yemenis; January 2010 — 2 Algerians, 1 Uzbek to Switzerland, 1 Egyptian, 1 Azerbaijani and 1 Tunisian to Slovakia; February 2010 — 1 Egyptian, 1 Libyan, 1 Tunisian to Albania, 1 Palestinian to Spain; March 2010 — 1 Libyan, 2 unidentified prisoners to Georgia, 2 Uighurs to Switzerland; May 2010 — 1 Syrian to Bulgaria, 1 Yemeni to Spain; July 2010 — 1 Yemeni (Mohammed Hassan Odaini); July 2010 — 1 Algerian, 1 Syrian to Cape Verde, 1 Uzbek to Latvia, 1 unidentified Afghan to Spain; September 2010 — 1 Palestinian, 1 Syrian to Germany; January 2011 – 1 Algerian; April 2012 – 2 Uighurs to El Salvador; July 2012 — 1 Sudanese; September 2012 — 1 Canadian (Omar Khadr) to ongoing imprisonment in Canada; August 2013 — 2 Algerians; December 2013 — 2 Algerians, 2 Saudis, 2 Sudanese and 3 Uighurs to Slovakia.

March 13, 2014

Quarterly Fundraiser Day 4: $1800 Still Needed to Support My Guantánamo Work

Please support my work!

Please support my work!

Dear friends and supporters,

Today is the fourth day of my quarterly fundraiser, in which I ask you, if you can, to make a donation to support my ongoing work telling the stories of the men still held in Guantánamo, and campaigning to secure the closure of the prison. If you can help out at all, please click on the “Donate” button above to donate via PayPal (and please note that you don’t need to be a PayPal member to use PayPal).

Most of the work I do in unpaid — or, more specifically, is only supported by you, my readers — and that is not just the majority of the 20 or so articles I write every month, but also some of my personal appearances, and most of my media appearances (on radio and TV), as well as my work on other issues of importance — the future of the NHS, for example, and the Tory-led UK government’s cruel assault on the disabled.

As a result, it is no exaggeration to say that, without your support, I will be unable to carry on working as I do. Since I launched this particular fundraiser on Monday, seven friends have donated $700, for which I’m very grateful, but over the next three months, that works out at just $50 a week, which isn’t really enough to live on.

If fifty of the thousands of people who read my work donated $50, I’d be able to reach my target, but that’s just one example. To give another example, a donation of $25/£15 is just $2/£1 a week for next three months, less than the price of a newspaper every week for the 3-5 articles I write every week, and the extras I also provide — my recent update to my definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, for example, updated for the first time since April 2012, expanded from four parts to six parts, and containing links to everything I have written about the prisoners since I first started working full-time on Guantánamo eight years ago.

All contributions to support my work are welcome, whether it’s $25, $100 or $500 — or, of course, the equivalent in pounds sterling or any other currency. You can also make a recurring payment on a monthly basis by ticking the box marked, “Make This Recurring (Monthly),” and if you are able to do so, it would be very much appreciated.

Readers can pay via PayPal from anywhere in the world, but if you’re in the UK and want to help without using PayPal, you can send me a cheque (address here — scroll down to the bottom of the page), and if you’re not a PayPal user and want to send a check from the US (or from anywhere else in the world, for that matter), please feel free to do so, but bear in mind that I have to pay a $10/£6.50 processing fee on every transaction. Securely packaged cash is also an option!

In conclusion, I hope you can help me continue working as an independent voice calling for the closure of Guantánamo.

With thanks, as ever, for your support,

Andy Worthington

London

March 13, 2014

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign.

March 12, 2014

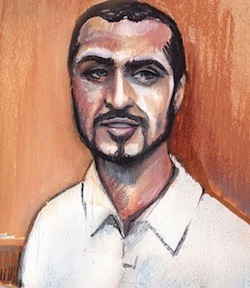

Guantánamo Prisoner Force-Fed Since 2007 Launches Historic Legal Challenge

I wrote the following article for the “Close Guantánamo” website, which I established in January 2012 with US attorney Tom Wilner. Please join us — just an email address is required to be counted amongst those opposed to the ongoing existence of Guantánamo, and to receive updates of our activities by email.

I wrote the following article for the “Close Guantánamo” website, which I established in January 2012 with US attorney Tom Wilner. Please join us — just an email address is required to be counted amongst those opposed to the ongoing existence of Guantánamo, and to receive updates of our activities by email.

Last month, the court of appeals in Washington D.C. (the D.C. Circuit Court) delivered an important ruling regarding Guantánamo prisoners’ right to challenge their force-feeding, and, more generally, other aspects of their detention. The force-feeding is the authorities’ response to prisoners undertaking long-term hunger strikes — or, as Jason Leopold discovered on March 11 through a FOIA request, what is now being referred to by the authorities as “long-term non-religious fasts.”

The court overturned rulings in the District Court last summer, in which two judges — one reluctantly, one less so — turned down the prisoners’ request for them to stop their force-feeding because of a precedent relating to Guantánamo, dating back to 2009.

As Dorothy J. Samuels explained in a column in the New York Times on March 11, revisiting that ruling:

In 2009, the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia badly undermined the rule of law by dismissing a civil case brought by former Guantánamo detainees never charged with any offense while in custody. That decision (which the Supreme Court declined to review) largely echoed the Obama administration’s arguments that former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld and other senior military officers could not be held responsible for violating the plaintiffs’ rights because the ill-treatment fell within the scope of their employment, and that it was not yet “clearly established” during the 2002-2004 period covered by the case that torture was illegal.

Highlighting the absurdity of that ruling, Samuels added:

Not only were the plaintiffs … never charged with any wrongdoing while in custody, but some of them were found by the government’s then-operative review process not to be enemy combatants. How could the abusive treatment of those individuals, including use of solitary confinement, sleep deprivation, exposure to cold, shackling, and mocking of religious practices, be considered within the scope of government employment? The simple answer is that it can’t, notwithstanding the government’s best efforts to make the whole problem go away.

As a result of last month’s appeals court ruling, a Yemeni prisoner, Emad Hassan (who I wrote about recently here), launched a historic legal challenge on March 11, becoming “the first Guantánamo Bay prisoner to have his claims of abuse at the military base considered by a US court of law,” as his lawyers at Reprieve put it.

Described, accurately, as being “gravely ill,” Emad Hassan, who was cleared for release in 2009 by President Obama’s high-level, inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force but is still held (like 75 other men cleared for release by the task force), “has been abusively force-fed more than 5,000 times since 2007 as part of the military’s efforts to break his hunger strike,” as Reprieve also described it, and “suffers from serious internal injuries as a result.”

As Reprieve also described it, the case, Hassan v. Obama, “highlights the increasing brutality of the Guantánamo Bay force-feeding process, which the military has amended step-by-step to make it so painful that only the most courageous peaceful protester can continue. It will be the first case requiring a US judge to review a Guantánamo prisoner’s detailed testimony describing his treatment — and will force the military to respond.”

With the support of two experts — the psychiatrist Stephen Xenakis, a retired Brigadier General and Army medical corps officer with 28 years of active service, and Steven Miles, Professor of Medicine at the University of Minnesota Medical School — Hassan’s legal team argue that the force-feeding practices at Guantánamo “amount to torture,” explaining that, for example, “the speed at which liquid is forced into some prisoners is a form of water torture that is similar to water-boarding.” The lawyers cite “clear evidence that the military practices and protocols have been deliberately altered to cause gratuitous pain and suffering in an effort to coerce the prisoners to renounce their peaceful protest.”

In a recent statement, Emad Hassan said, “All I want is what President Obama promised — my liberty, and fair treatment for others. I have been cleared for five years, and I have been force-fed for seven years. This is not a life worth living, it is a life of constant pain and suffering. While I do not want to die, it is surely my right to protest peacefully without being degraded and abused every day.”

Jon B. Eisenberg, counsel for Emad Hassan in the US, said, “After 12 years of wrongful imprisonment, Emad and his fellow-hunger strikers are protesting peacefully in the only way they can. The punishment inflicted on these desperate men is nothing short of torture, and it is about time that it is brought to light and judged by a court of law.”

Eric Lewis, a partner at Lewis Baach PLLC and the chair of the newly-established Reprieve US, said, “This case marks an historic step in the long battle to bring basic rights to the legal black hole at Guantánamo Bay. For over a decade, abused prisoners at the US military base have been denied any effective legal mechanism to challenge their treatment. This case calls upon US judges to restore the most basic rights, medical standards and human dignity to these men at Guantánamo Bay.”

In a report for Al-Jazeera America, the journalist Massoud Hayoun spoke to Clive Stafford Smith, the founder and director of Reprieve, who told him, “This is the first time that any court will compare what the prisoners are saying about the torturous methods with what the military is saying.”

In a declaration accompanying the court submission, Stafford Smith stated how, in a meeting at Guantánamo last month, Hassan spoke about how, in early 2006, the authorities described the restraint chairs brought to Guantánamo to break the prison-wide hunger strike that had been raging from the summer of 2005 onwards as the “torture chairs.” He described being force-fed through large tubes, which were shoved into and pulled out of his nostrils before and after each feeding.

Alarmingly, as Stafford Smith also explained:

[O]n the Torture Chair the men were also given an anti-constipation drug which would cause ether to defecate on themselves while still being fed. They were not given clean clothes. Mr. Hassan says he finds it difficult to talk about this even today, several years later. “I could not think someone who called himself human did this to me,” he said to me on February 5, 2014.

Emad Hassan’s first hunger strike lasted from June 2005 February 2006, and he began hunger striking again in 2007, a process that has continued unbroken since that time. As Stafford Smith described it, he “has suffered with chronic pancreatitis and multiple hospitalizations stemming from the force feeding techniques.” He added that “his illness has included attacks brought on by the use of the nutritional supplement Jevity, which contains high levels of fat — a trigger for pancreatitis.”

Hassan also told his lawyer that “the doctors at Guantánamo do not protect his health or interests,” and that their “only object appears to be to find ways to make the detainees bend to the military’s will.” He added, “They systematically make the force feeding process gratuitously painful, by forcing the liquid down the men’s noses faster, by speeding up the flow of liquid, by using a bigger tube, and by pulling the 110 centimetre tube out of his nostril after every feed and then forcing it back in.”

Hassan also told Stafford Smith that, in response to nausea brought on by the forced feeding process, the authorities forced him — and other hunger strikers — to take Reglan, a drug that he said “made him feel crazy.” In the Standard Operating Procedure for dealing with hunger strikers, which was obtained last year through FOIA legislation by Jason Leopold for Al-Jazeera, the use of Reglan was recommended during force-feeding, even though, as Reprieve explained in a press release to accompany the submission of the first legal challenge to the force-feeding last June, “Medical studies into the drug have determined that prolonged use of Reglan also is linked to a high rate of tardive dyskinesia (TD), a potentially irreversible and disfiguring disorder characterized by involuntary movements of the face, tongue, or extremities.”

While medicated on Reglan, Stafford Smith wrote, Hassan “would sit on his bed, legs folded, thinking that he was talking to the nurse, but he actually found that he was talking to himself.”

Stafford Smith also noted that the last time he met Hassan, who is 5 feet 3 inches tall and weighed 119 pounds before his capture, he weighed just 85 pounds and was in “very bad” health. This was also his weight in December 2005, as I explained in 2009 in a report based on an analysis of height and weight records, and it is, of course, an alarmingly low body weight for a full-grown man. If a photo was available, Emad Hassan would resemble one of the survivors of the Holocaust.

In the submission to the court, Emad Hassan’s legal term explained that their client “wishes to make clear that he is not seeking an injunction to permit him to continue his hunger strike until death. Rather, he is seeking a constitutional protocol that ensures he is not force-fed prematurely and is not subjected to methods of force-feeding that cause unnecessary pain and suffering.”

Because this is a a preliminary injunction, it “puts time schedules in place that are quite short — around 20 days normally,” Stafford Smith told Al-Jazeera, meaning that a decision may be made by the end of the month. In the meantime, the force-feeding of Emad Hassan, and the 17 other hunger strikers currently being force-fed, continues, even though, as Clive Stafford Smith accurately described it, the prison at Guantánamo Bay has become a “festering wound of human rights violations.”

I hope the judges recognize this, and act accordingly.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

March 10, 2014

Quarterly Fundraiser: $2500 Needed to Support My Guantánamo Work

Please support my work!

Dear friends and supporters,

It’s that time of year again, when I ask you, if you can, to help to support my work as an independent journalist researching, writing about and commenting on the “war on terror” prison at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, and working to try to get the men still held there either released or tried, and the prison closed down. If you can help out at all, please click on the “Donate” button above to donate via PayPal (and I should add that you don’t need to be a PayPal member to use PayPal).

Every three months, I ask you if you can help to support my work — not just my writing, but also my personal appearances, the TV and radio interviews I undertake, and the maintenance of this website and various social media sites associated with it.

All contributions to support my work are welcome, whether it’s $25, $100 or $500 — or, of course, the equivalent in pounds sterling or any other currency. You can also make a recurring payment on a monthly basis by ticking the box marked, “Make This Recurring (Monthly),” and if you are able to do so, it would be very much appreciated.

Readers can pay via PayPal from anywhere in the world, but if you’re in the UK and want to help without using PayPal, you can send me a cheque (address here — scroll down to the bottom of the page), and if you’re not a PayPal user and want to send a check from the US (or from anywhere else in the world, for that matter), please feel free to do so, but bear in mind that I have to pay a $10/£6.50 processing fee on every transaction. Securely packaged cash is also an option!

It’s eight years since I began working on Guantánamo on a full-time basis — first through researching and writing my book The Guantánamo Files, and, since May 2007, as a full-time independent investigative journalist and commentator. I had begun researching Guantánamo in September 2005, but eight years ago, in March 2006, three developments occurred that persuaded me that writing a book about Guantánamo and the men held there was not only necessary, but also possible.

The first was Moazzam Begg’s autobiography, Enemy Combatant: A British Muslim’s Journey to Guantánamo and Back, which I bought and devoured shortly ate its publication on February 27, 2006, and the second was the docudrama “The Road to Guantánamo,” directed by Michael Winterbottom and Mat Whitecross, telling the stories of the three Guantánamo prisoners known as the “Tipton Three,” which I watched engrossed when it was first broadcast on Channel 4 on March 9, 2006.

The third development was the release, on March 3, 2006, of thousands of pages of documents relating to the Guantánamo prisoners, released after the Pentagon lost a FOIA lawsuit — including, for the first time, their names and nationalities, as well as the unclassified allegations against them, and the transcripts of the tribunals and review boards held at Guantánamo, a rigged process designed to establish that the majority of the prisoners were correctly designated as “enemy combatants,” who could continue to be held indefinitely without charge or trial, but one that, nevertheless, allowed the prisoners to have a voice.

If you follow my work, you will know that I drew on these documents (and others released in the following months) to write my book The Guantánamo Files and to begin writing about Guantánamo and the men held there on a full-time basis as a freelance journalist after I finished the manuscript for my book in May 2007. Since my last fundraiser, in December, I have been writing about the men freed as a result of the prison-wide hunger strike last year, which forced President Obama to promise action.

Nine prisoners were released in December — more than in the previous three years — but since then the release of prisoners has ground to a halt once more, even though 77 of the 155 men still held have been cleared for release — all but one since January 2010, when the high-level, inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force appointed by President Obama shortly after he took office in January 2009, issued its recommendations regarding who to release, who to prosecute and who to continue holding without charge or trial. As a result, my work telling the men’s stories and reminding the world about their existence, is, sadly, as important as ever.

As I mentioned above, your support is essential, as the only other regular income I receive is from the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, which I established with the US attorney Tom Wilner in January 2012. Most of my work, however, is only possible because of your support — for example, the majority of the 50+ articles I have written since my last fund-raising appeal in December, and the additional projects I have undertaken, like my definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, which I first published in March 2009, and which I have just updated — for the first time since April 2012 — and expanded from four parts to six parts. The prisoner list contains links to everything I have written about the prisoners over the last eight years, in over 1,500 articles, and is intended to provide a powerful resource for those researching Guantánamo.

In addition, in February, I updated my definitive Guantánamo habeas corpus list, analyzing the results of the prisoners’ habeas corpus petitions from 2008, when they provided the opportunity for innocent men and insignificant prisoners to leave Guantánamo, to 2010 and 2011, when judges in the appeals court in Washington D.C. shut down habeas corpus as a means whereby the prisoners could be released.

I do hope you can help me continue working as an independent voice calling for the closure of Guantánamo, and an end to the lies told by those who want to keep it open. Indefinite imprisonment without charge or trial is unacceptable under any circumstances, and the regime at Guantánamo must be brought to an end.

With thanks, as ever, for your support,

Andy Worthington

London

March 10, 2014

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the four-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

March 7, 2014

Updated for 2014: Andy Worthington’s Definitive Guantánamo Prisoner List – Now in Six Parts

Please support my work!

See Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5 and Part 6 of Andy Worthington’s Definitive Guantánamo Prisoner List

Eight years ago, I began working full-time on exposing the truth about Guantánamo (essentially, as an illegal interrogation center using various forms of torture and abuse) and researching and telling the stories of the men — and boys — held there, first for my book The Guantánamo Files, and, since May 2007, as an independent investigative journalist and commentator writing about Guantánamo and related issues on an almost daily basis. I have published 2,175 articles since May 2007, and over 1,500 of those articles are about Guantánamo.

Five years ago, I decided that it would be useful to list the 779 prisoners who have been held at Guantánamo since it opened on January 11, 2002, and to provide links to articles in which I told their stories — and also references to where I told their stories in The Guantánamo Files (about 450 stories in total) or in in 12 additional online chapters I wrote between 2007 and 2009.

I updated the list in January 2010, in July 2010, in May 2011, and in April 2012, on the first anniversary of the release, by WikiLeaks, of “The Guantánamo Files,” classified military files relating to almost all of the 779 prisoners who have been held at Guantánamo since it opened. I worked as a media partner on the release of these files, and, as I noted in April 2012, when my update to the list coincided with the 1st anniversary of the release of those files, “We had the eyes of the world on us for just a week until — whether by coincidence or design — US Special Forces assassinated Osama bin Laden, and Guantánamo disappeared from the headlines once more, leaving advocates of torture and arbitrary detention free to resume their cynical maneuvering with renewed lies about the efficacy of torture and the necessity for Guantánamo to continue to exist.”

This latest update to the list is published almost five years to the day since my first four-part list, and, to accommodate all the information it contains, I have expanded it from four parts to six parts, and also included more photos than were previously available. Please note that Part 1 covers ISN numbers (prisoner numbers) 1-133, Part 2 covers 134-268, Part 3 covers 269-496, Part 4 covers 497-661, Part 5 covers 662-928 and Part 6 covers 929-10029.

Two years ago, when this list was last updated, I had begun an unprecedented project, “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” a projected 70-part, million-word series, in which I analyzed the information in the WikiLeaks files, adding it to what was already known about the prisoners, to create what I hoped at the time would be “a lasting indictment of the lies and distortions used by the Bush administration to justify holding the men and boys imprisoned at Guantánamo.” As I also noted:

For the most part, despite the hyperbole about the prisoners being “the worst of the worst,” the captives were people that the US had largely bought from its Afghan and Pakistani allies, or had rounded up randomly, and had then tortured or otherwise coerced — or in some cases bribed — into telling lies about themselves and their fellow prisoners to create a giant house of cards built largely on violence and involving very little actual intelligence.

I still hope to continue with “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” which, currently, features 422 profiles in 34 articles, but to do so I need to secure further funding. In the meantime, however, I have spent the last two years continuing to research and write about the prisoners, here on my website, on the “Close Guantánamo” website, and for other publications, as well as visiting the US to campaign for the prison’s closure, regularly attending events in the UK, and undertaking TV and radio interviews on a regular basis.

Since my last update in April 2012, securing any kind of progress towards the closure of Guantánamo has been a slow and difficult process. Just 13 prisoners have been freed in the last two years, even though 77 of the remaining 155 prisoners have been cleared for release — all but one since President Obama’s high-level, inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force published its report in January 2010 recommending who to charge or release — or, alarmingly, to continue to hold without charge or trial — after a year spent reviewing the prisoners’ cases.

Cynically, Congress tied President Obama’s hands in releasing prisoners from Guantánamo, setting up an onerous (if not impossible) set of demands if any prisoners were to be released, and although the president possessed the power to override Congress, he chose not to do so for reasons of political expediency.

In addition, the Supreme Court also washed its hands of responsibility for the prisoners, leaving it up to the men themselves to force the world to pay attention to their plight and their despair. which they did by embarking on a major hunger strike in 2013. This led President Obama to promise to resume releasing prisoners, and as a result eleven men were released between August and December 2013, compared to just five men in the previous three years.

With Congress now having been persuaded to ease its restrictions on the release of prisoners, President Obama needs to push ahead with the release of the 77 men cleared for release — overcoming fears of instability in Yemen, the home of the majority of the cleared prisoners — and he also needs to speed up the review process for 71 other prisoners, and proceed to trials for the only other men — just eight in total — who have been charged and will face trials.

In addition, important information about the status of the 155 prisoners still held has been released in the last two years. This came from (a) a list of 56 cleared prisoners released by the Justice Department in September 2012, based on the recommendations of the task force, and (b) a complete list of the task force’s recommendations, released by the DoJ in June 2013, which also identifies the 46 men recommended for indefinite detention without charge or trial, and the 33 recommended for trials. There are also 30 additional Yemenis listed who were recommended for “conditional detention,” to be freed when it was decided that the security situation in Yemen had improved.

I have also included some additional information about the 71 men who were put forward for Periodic Review Boards in April 2013 — the 46 men recommended for indefinite detention without charge or trial, and 25 of the 33 recommended for trials — after the list was secured through FOIA legislation by Jason Leopold in February 2014.

My list is not, of course, the only online database that is publicly available. The New York Times, for example, has made all the publicly available information about the prisoners, from the Bush-era Combatant Status Review Tribunals (CSRTs) and annual Administrative Review Boards (ARBs), available on its Guantánamo Docket (and the original source material remains available on the US Department of Defense’s website), although these only cover the stories of around three-quarters of the 779 prisoners held in total, and, most importantly, none of these documents provide contextual analysis of the men’s stories.

As a result, as I explained when I first published the list:

It is my hope that this project will provide an invaluable research tool for those seeking to understand how it came to pass that the government of the United States turned its back on domestic and international law, establishing torture as official US policy, and holding men without charge or trial neither as prisoners of war, protected by the Geneva Conventions, nor as criminal suspects to be put forward for trial in a federal court, but as “illegal enemy combatants.”

I also hope that it provides a compelling explanation of how that same government, under the leadership of George W. Bush, Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld, established a prison in which the overwhelming majority of those held — at least 93 percent of the 779 men and boys imprisoned in total — were either completely innocent people, seized as a result of dubious intelligence or sold for bounty payments, or Taliban foot soldiers, recruited to fight an inter-Muslim civil war that began long before the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, and that had nothing to do with al-Qaeda, Osama bin Laden or international terrorism.

With hindsight, the only thing about the above that might need changing is that figure of 93 percent. With just eight men facing charges, six having been convicted (or having reached plea deals), without those convictions subsequently being overturned, and only a handful having been released to engage in, or threaten to engage in terrorism, despite black propaganda from Guantánamo’s defenders claiming otherwise, it may be more accurate to state that the innocents and foot soldiers actually add up to somewhere between 95 and 97 percent of all of those held throughout Guantánamo’s long and dark history.

In conclusion, I hope that this updated six-part list is not only useful from the point of view of historical research, but also that it provides crucial, relevant information that is valuable for those still seeking to close Guantánamo, and to bring to an end this bleak chapter in American history.

As ever, I thank you for your support, and if you’re able to make a donation to help me to continue my work, then I will be very grateful. Please click on the “Donate” button above to make a payment via PayPal. All contributions are welcome, whether it’s $25, $100 or $500.

Andy Worthington

London, March 7, 2014

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the four-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

March 6, 2014

Life after Guantánamo: Stories from Afghanistan

[image error]On February 24, I was delighted to be interviewed about Guantánamo by BBC World News — the BBC’s global, commercial arm — as part of their “Freedom” series. As the website states, “Whether it’s freedom from surveillance or freedom to be single, the BBC is investigating what freedom means in the modern world.”

The interview, which, unfortunately, isn’t available online, was preceded by a short clip of two former Guantánamo prisoners, from Afghanistan, talking about their experiences to the reporter Dawood Azami, who travelled to Afghanistan to meet former prisoners. The two men were Shahzada Khan (ISN 952, also known as Haji Shahzada), who was released in April 2005, and Haji Ghalib (ISN 987), who was released in February 2007.

Dawood Azami’s visit, and his meetings with former prisoners were also featured in a BBC World Service broadcast, “Guantánamo Voices,” and in an article for the BBC World Service’s online magazine, which I’m cross-posting below because it provides a powerful insight into some generally little-known stories, which demonstrate clearly the kind of chronic failures of intelligence that led to so many insignificant or completely innocent men — and, in some cases, boys — ending up at Guantánamo.

As Dawood Azami notes in his article, 220 of the 779 prisoners held at Guantánamo throughout its long and inglorious 12-year history were Afghans — and 19 are still held. Many, as I first discovered for my book The Guantánamo Files in 2006 and 2007, and have written about since in my articles, were unwilling Taliban conscripts, or even, in as many as a few dozen cases, people who were working for the Americans in Afghanistan, but were seized and sent to Guantánamo because rivals told lies about them, and no one in the US military or the intelligence services was providing the kind of overview required to work out who was telling the truth.

In one particularly notorious example, a man named Abdul Razzaq Hekmati, who had actually freed three senior anti-Taliban figures from a Taliban jail (including Ismael Khan, who became a minister in Hamid Karzai’s post-Taliban government) died of cancer in Guantánamo without anyone ever having believed his story. After his death, in December 2007, I wrote about the tragic circumstances of his death in a front-page story for the New York Times with Carlotta Gall.

I have previously written about Haji Shahzada, not just in my book but also in an article in September 2011, in which I explained that he was a father of six and a village elder in Kandahar province, who was seized in a raid on his house in January 2003, with two house guests, and held at Guantánamo for over two years until his release in April 2005.

As I also explained:

Shahzada’s story (and that of the men seized with him) was one that had struck me as particularly significant when I was researching my book The Guantánamo Files, as it was a clear demonstration of how easily US forces in Afghanistan were deceived, seizing innocent people after tip-offs from untrustworthy individuals with their own agendas. In Shahzada’s case, it has not been confirmed whether the tip-off came from a rival or from members of his family seeking to seize his assets, but the entire mission was a disgrace.

One of the men seized with him, Abdullah Khan, had sold Shahzada a dog, as both men were interested in dog-fighting, but he was regarded by the soldiers involved in the raid (and, subsequently, by US interrogators) as Khairullah Khairkhwa, a senior figure in the Taliban. The problem with this scenario was not only that Khan was not Khairkhwa, but also that Khairkhwa had been in US custody since February 2002 and was held at Guantánamo (where he remains to this day).

In addition, Shahzada, a landowner who had never liked the Taliban, endured numerous aggressive interrogations in which he was obliged to repeat, over and over again, that his friend Khan was not a Taliban commander, and that he had not been supporting the Taliban. He was also particularly eloquent in warning his captors that seizing innocent people like him was a sure way of losing hearts and minds in Afghanistan.

“This is just me you brought but I have six sons left behind in my country,” he said. “I have ten uncles in my area that would be against you. I don’t care about myself. I could die here, but I have 300 male members of my family there in my country. If you want to build Afghanistan you can’t build it this way … I will tell anybody who asks me that this is oppression.”

I also analyzed Haji Shahzada’s Detainee Assessment Brief (one of the classified military files released by Wikileaks in April 2011) here.

In The Guantánamo Files, I wrote about Haji Ghalib as follows:

40-year old Haji Ghalib, the chief of police for a district in Jalalabad, and one of his officers, 32-year Kako Kandahari, were captured together, after US and Afghan forces searched their compound and identified weapons and explosives that they thought were going to be used against them. Both men pointed out, however, that they fought with the Americans in Tora Bora. “I captured a lot of al-Qaeda and Arabs that were turned over to the Americans,” Ghalib said, “and I see those people here that I helped capture in Afghanistan.” He explained that he thought he may have been betrayed by one of the commanders in Tora Bora, because he “let about 40 [al-Qaeda] escape so I got on the phone and cussed at him and that is why I am here.”

In 2008, Ghalib also told Tom Lasseter of McClatchy Newspapers (as later reported here) that he was detained “in a basement at an airstrip in Jalalabad during March 2003” by Special Forces troops, and added, “At night they would strap me down on a cot, and put a bucket of water on the floor, in front of my head. And then they would tip the cot forward and dunk my head in the bucket … They would leave my head underwater and then jerk it out by my hair. I sometimes lost consciousness.”

In 2008, Ghalib also told Tom Lasseter of McClatchy Newspapers (as later reported here) that he was detained “in a basement at an airstrip in Jalalabad during March 2003” by Special Forces troops, and added, “At night they would strap me down on a cot, and put a bucket of water on the floor, in front of my head. And then they would tip the cot forward and dunk my head in the bucket … They would leave my head underwater and then jerk it out by my hair. I sometimes lost consciousness.”

Also featured in Dawood Azami’s article are four other former prisoners: the father and son Haji Nasrat Khan (ISN 1009), who was released in August 2006, and Izatullah Nasratyar (ISN 977, also identified as Izatullah Nasrat Yar), who was released in November 2007. Both men were pro-US and opposed to the Taliban, and, as well as featuring them in The Guantánamo Files, I wrote about Haji Nasrat Khan, who was 78 years old when he was freed, here, based on an analysis of his Detainee Assessment Brief, and including his powerful criticism of how the US betrayed Afghan hopes, and I wrote about his son on his release here.

Also featured were Haji Ruhullah Wakil (ISN 798), a tribal elder from eastern Afghanistan, released in May 2008, who I wrote about on his release and also here, and Mawlawi Abdul Razaq (aka Abdul Razak Iktiar Mohammed, ISN 1043), the former Minister of Commerce in the Taliban government, who I wrote about briefly on his release in August 2007.

I hope you have time to read the article,and to share it if you find it useful. One piece of information that I had not come across before, but found very interesting, is that, in 2012, about 90 former Afghan prisoners came together to form “The Association of Former Guantánamo Detainees from Afghanistan,” and I’d very much like to find out more about this association, as I believe it could help to dispel some of the lies that are still told by those in the US who still support the existence of Guantánamo.

Life after Guantánamo prison

By Dawood Azami, BBC World Service, February 25, 2014

Some 220 Afghans have been held at the US military prison at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, making them the largest single group of the nearly 50 nationalities involved. The vast majority have returned home, where their stories of imprisonment, and sometimes abuse at American hands, have made a big impact.

I stopped strangers on the street in Kabul and other provinces of Afghanistan to ask if they had heard of Manhattan or the World Trade Centre. Few of them had. But all of them knew about Guantánamo.

“In the history of mankind, there have been only two such cruel prisons. One was Hitler’s and the other one is this American prison,” says Haji Ghalib, a former district police officer from eastern Afghanistan, who was arrested in his office in February 2003.

That sums up the reputation Guantánamo has in Afghanistan.

Three Afghans died in detention. Of the rest, all but 19 have been freed without charge, and have usually returned home to a hero’s welcome.

“Thousands of people from my villages and the surrounding area had gathered to welcome me. I shook hands with more than 2,000 of them,” says Haji Shahzada Khan, a village elder from Kandahar, southern Afghanistan.

It was much the same for Izatullah Nasratyar, a former Mujahideen fighter who helped push Soviet troops out of Afghanistan, with American help, in his youth.

“People gave me a very warm welcome. They brought me cattle and other things they could afford,” he says.

But how much the ex-detainees are prepared to say about their experiences varies.

Some have written books that have become bestsellers in Afghanistan and Pakistan. Others are more guarded.

“They did things to us that is against humanity, against human rights and against Islam. I cannot even talk about that and I will not talk about it,” says Haji Nasrat Khan, Izatullah’s elderly father.

He was already in his late 70s and in poor health when he was seized in 2003 by the US forces in a raid at his house in a village a few kilometres outside the Afghan capital, Kabul.

“I told them find me a single bit of evidence. If you don’t have the evidence, then why have you arrested me and kept me here? It was not only me, there were a lot of innocent people they detained.”

Haji Shahzada also prefers to remain silent.

“I usually say to people that Guantánamo is like the mother-in-laws’ home. That it’s a nice place,” he says.

“If we tell the truth about conditions there, then it will increase the worry and the suffering of the relatives of remaining detainees. I cannot disclose the realities of life in Guantánamo.”

The experience of Guantánamo is different for different prisoners.

So-called “compliant” detainees — those who follow the rules — live together in a communal way, can meet other inmates from their own block and are able to learn as well as read.

“People there don’t waste their time. The only good memory I have from Guantánamo is that I learnt the Koran and writing and also got a different experience,” says Haji Ghalib.

“I memorised the Koran there and learnt many new prayers that now I recite regularly,” says Izatullah Nasratyar.

Both men spent four and a half years at the detention facility.

But Haji Ruhullah, a tribal elder from eastern Afghanistan, paints a harsher picture.

“Guantánamo not only took the freedom of movement, it also took all the other rights. Even talking was not allowed,” he says. “We were not even allowed to move our lips while reading a book or reciting the Koran. The guards would punish us because they thought we were talking to other prisoners.”

Nearly all the former inmates I spoke to said they did not expect to return back alive. Many compared the experience of Guantánamo with death — and their release to being reborn.

“When we were transferred [to Afghanistan] from Guantánamo, it was like rising from the dead,” says former Taliban government Minister of Commerce, Mawlawi Abdul Razaq, who spent five years in detention after his arrest in April 2002, four of them in Guantánamo.

“While in Guantánamo, we didn’t have any knowledge of the outside world. The letters we were exchanging with our families were mostly censored and blacked out by the Americans. We were worried about our families … The difference was like coming out of the grave.”

Izatullah says the experience of Guantánamo changed his outlook on life.

“This prison has given me a lot of good things,” he says, surprisingly.

“I was never thankful enough for the bounties Allah has bestowed upon us. I had not thanked God for the freedom to be in the sun or the shade at your own free will or to go to the toilet whenever you want to.

“But when we were in the hands of other men we realised that God has bestowed a lot of bounties upon us. It was only then we realised what a privilege freedom is.”

After the joy of homecoming, though, the experience of picking up after four or five lost years has often been bitter.

“I went to see my vineyards after my release and found out that up to 5,000 of the vine trees had dried up. That is the memory that haunts me the most,” says Shahzada Khan.

“My small children couldn’t look after them in my absence. That was the day when I realised that I had really been imprisoned.”

Some of the former detainees lost their livelihoods and jobs.

“Neither the government nor anyone else will employ us — I’ve been without a job since I came home. Even after we were proven innocent, why won’t they help us?” says Haji Ghalib, the former district police officer.

Although released without charge, many of them say they are still harassed by the US and Afghan security forces, who suspect some of them of possible links with the insurgents.

A few former detainees have been killed in raids, mostly by US forces. Some have been re-arrested and imprisoned in Afghanistan, accused of being “involved in subversive activities”.

In fear of such a fate, about 90 of them came together in 2012 to form “The Association of Former Guantánamo Detainees from Afghanistan”.

“We came together in this body to support each other and protect our rights,” says Haji Ruhullah Wakil, the head of the association.

“We have met President Karzai, Nato commanders and the US officials in Kabul to discuss our problems and assure them that we pose no threat.”

The mere existence of Guantánamo, however, does continue to pose a threat — as the Taliban is able to exploit the fact in verse designed to recruit and motivate fighters.

One such chant describes a young Taliban detainee writing a letter to his mother.

“I am a prisoner in Cuba’s jail // Neither at night, nor at day, I can’t sleep, oh mother,” it goes.

The singer describes the hardship of life at Guantánamo and tells his mother there is no hope of seeing him alive.

The Americans have to weigh this danger against the risk of releasing potentially dangerous men.

The detention facility still holds 155 detainees — down from a peak of nearly 800.

“The detainees that were brought here were picked up on the battlefield. We kept them here to keep them off the battlefield,” says Admiral Richard Butler, commander of the Joint Task Force, that runs the Guantánamo military prison.

“Once the chain of command decides they’re no longer needed to be kept here for that reason, then we’ll transfer ‘em. But until then I make no judgement on the guilt or innocence of the detainees.”

Haji Ghalib did return to Afghanistan, and was reunited with his family. But without a job, living in a cold damp apartment in Kabul, his life has undergone a radical turn for the worse.

“Two Americans told me that our American government apologises from you because you spent five years here but you were proven innocent,” he says.

“I told them, ‘I cannot forgive you from my heart.’”

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the four-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

March 5, 2014

A Few Surprises in the New Guantánamo Prisoner List

I wrote the following article for the “Close Guantánamo” website, which I established in January 2012 with US attorney Tom Wilner. Please join us — just an email address is required to be counted amongst those opposed to the ongoing existence of Guantánamo, and to receive updates of our activities by email.

I wrote the following article for the “Close Guantánamo” website, which I established in January 2012 with US attorney Tom Wilner. Please join us — just an email address is required to be counted amongst those opposed to the ongoing existence of Guantánamo, and to receive updates of our activities by email.

On February 20, my friend and colleague, the investigative journalist Jason Leopold, published a prisoner list from Guantánamo, which he had just obtained from the Pentagon, and which had not previously been made public.

The list, “71 Guantánamo Detalnees Determined Eligible to Receive a Periodic Review Board as of April 19, 2013,” identifies, by name, 71 of the 166 prisoners who were held at the time, and, as Jason explained in an accompanying article:

The unclassified two-page list was obtained by Al Jazeera in response to a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request filed last July, immediately after a Defense Department official began notifying attorneys for some prisoners that parole hearings would begin in an effort to empty out Guantánamo and help President Barack Obama make good on his five-year-old promise to shutter the detention facility.

When the notifications began last July (which I wrote about here), it was apparent that the decisions regarding the Periodic Review Boards (PRBs) were based on recommendations made in January 2010 by the high-level, inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force that President Obama established shortly after taking office in 2009. The task force members spent a year reviewing the cases of the 240 prisoners held when Obama took office, and recommended them for release (156 men, 80 of whom have been released), for prosecution (36 men in total) or for ongoing imprisonment without charge or trial, on the basis that they were too dangerous to release but insufficient evidence existed to put them on trial.

This latter category, comprising 48 of the prisoners, was profoundly troubling to those of us who had looked closely at what purported to be the evidence against the prisoners, and had concluded, with good reason, that it was profoundly unreliable. This is because it consisted, to an alarming degree, of self-incriminating statements made by the prisoners themselves, often in circumstances in which coercion, or other forms of pressure were used, or of statements made by other prisoners, even though many of these prisoners had been identified as unreliable by personnel at Guantánamo, and also, in some cases, by judges reviewing the supposed evidence in the prisoners’ habeas corpus petitions.

In July, when the first Periodic Review Board notifications began, it was obvious that the 71 men included 46 of the 48 men who had been designated for ongoing imprisonment without charge or trial by the task force. The other two, sadly, had died at Guantánamo in 2011. Following the task force’s recommendations, President Obama had issued an executive order designating these 46 men for ongoing imprisonment without charge or trial, but had attempted to deflect criticism from human rights advocates by promising that they would receive Periodic Review Boards, so when the notifications began they were, to be frank, long overdue.

The identities of these 46 men were revealed last June, when Charlie Savage of the New York Times obtained, for the first time, the “Final Dispositions” of the Guantánamo Review Task Force, identifying whether those still held had been cleared for release, recommended for prosecution, or recommended for ongoing imprisonment without charge or trial.

The identities of these 46 men can also be found in the prisoner list on the “Close Guantánamo” website, or in the list of prisoners included in my article in January providing information for those who want to write to the prisoners at Guantánamo.

Until now, however, the US government had not spelled out publicly who the other 25 men were, although the identities of the 36 men recommended for prosecution had been made available last June in the task force’s “Final Dispositions,” and most of the 25 could be worked out by removing from the 36 the names of those who have already been charged.

Four of these men are no longer at Guantánamo — Ibrahim al-Qosi, Omar Khadr and Noor Uthman Muhammed were released after agreeing to plea deals in their trials by military commission, and one other — Ahmed Khalfan Ghailani — was transferred to the US, where he was tried and convicted, and another, Majid Khan, agreed to a plea deal and is still held.

Eight others have been charged — Ahmed al-Darbi, Mustafa al-Hawsawi, Ramzi Bin al-Shibh, Walid Bin Attash, Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri, Ali Abd al-Aziz Ali, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and Abd al-Hadi al-Iraqi.

According to this analysis of the figures, only eleven men should have been charged, rather than the 13 who have been charged, but the list obtained by Jason Leopold explains the discrepancy, as Ahmed al-Darbi and Abd al-Hadi al-Iraqi, although on the list, will evidently not be facing Periodic Review Boards. Al-Darbi recently agreed to a plea deal, and al-Iraqi, charged in June 2013, recently had conspiracy added to his charge sheet.

This was in spite of the fact that, although 36 men were recommended for prosecution, only 13 have been charged because judges in the court of appeals in Washington D.C., in two ground-breaking cases in October 2012 and January 2013, dismissed two of the only convictions secured in the military commissions, of Salim Hamdan and Ali Hamza al-Bahlul, on the basis that the charges — material support for terrorism and conspiracy — were not real war crimes and had been invented by Congress.

As a result of removing these names, it has now become clear that the 25 men originally recommended for prosecution, but now facing PRBs instead, include such prominent figures in Guantánamo’s history as Abu Zubaydah, the first supposed “high-value detainee,” held in CIA “black sites” from March 2002 to September 2006, when he arrived at Guantánamo. The Bush administration’s vile torture program was first developed for Abu Zubaydah, even though he was never a member of al-Qaeda at all, despite being initially touted as the organization’s third-in-command. Also facing a PRB is Mohammed al-Qahtani, supposedly intended as the 20th hijacker for the 9/11 attacks, who had a specific torture program approved for him at Guantánamo by Donald Rumsfeld.

Also included are other “high-value detainees” held in CIA “black sites” prior to their arrival at Guantánamo in September 2006 — Abu Faraj al-Libi (captured in Pakistan in May 2005), the Indonesian Hambali and two alleged associates, Mohd Farik bin Amin and Bashir bin Lap (captured in Thailand in 2003), and Haroon al-Afghani, who arrived at Guantánamo in 2007. Also on the list are a number of other men held in “black sites” and transferred to Guantánamo in September 2004 — Sanad al-Kazimi and Sharqawi Abdu Ali al-Hajj, Hassan bin Attash (the brother of Walid bin Attash, who was just 17 when he was seized in Pakistan in September 2002 and rendered for torture in Jordan), the brothers Abdul and Mohammed Rabbani (also seized in Pakistan in September 2002) — and Saifullah Paracha, a Pakistani businessman seized in Thailand in 2003.

Others of note are Mohamedou Ould Slahi, another torture victim, who, despite being hyped as an al-Qaeda member, had his habeas corpus petition granted in 2010, Tariq al-Sawah, an Egyptian whose lawyers are seeking his release because he is very ill, Sufyian Barhoumi, an Algerian who is trying to get charged so he might be able to be released, Ravil Mingazov, the last Russian in Guantánamo, and Obaidullah, an insignificant Afghan, wrongly accused of being an insurgent, who nevertheless was put forward for a trial by military commission.

The identities of the 71 men are now known, and I have added the information to the prisoner list on the “Close Guantánamo” website, but it is of little help to them. The first Periodic Review Board took place in October, and the second in January, and although the first PRB led to a recommendation for the release of the man in question, Mahmoud al-Mujahid, a Yemeni, he only joins the 76 other prisoners, cleared for release by the task force, who are still held.

And of course, with each PRB only taking place every three months, it will take until 2031, at this rate, for all the PRBs to be completed.

The message, then, must be for the Obama administration to release the prisoners already cleared for release, and to speed up significantly the process of conducting the Periodic Review Boards.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).