Andy Worthington's Blog, page 121

February 13, 2014

Radio: On the BBC World Service, Andy Worthington Discusses the US’s Latest Efforts to Hold Prisoners in Bagram Forever

This morning, I was interviewed on the BBC World Service’s “World Update” programme about Bagram prison in Afghanistan, and the latest news from the facility, in the long, drawn-out process of the US handing over control of the prison to the Afghan government. The show is here, it’s available for the next six days, and the section in which I’m interviewed begins at 27 minutes in, and lasts for four minutes.

This morning, I was interviewed on the BBC World Service’s “World Update” programme about Bagram prison in Afghanistan, and the latest news from the facility, in the long, drawn-out process of the US handing over control of the prison to the Afghan government. The show is here, it’s available for the next six days, and the section in which I’m interviewed begins at 27 minutes in, and lasts for four minutes.

The prison at Bagram airbase — America’s main prison in Afghanistan — was established in an old Soviet factory following the US-led invasion of Afghanistan in October 2001, and was a place of great brutality, where a handful of prisoners were murdered in US custody.

Used to process prisoners for Guantánamo until the end of 2003, it then grew in size throughout the rest of Bush’s presidency, and into President Obama’s. During this time, a new prison was built, which was named the Parwan Detention facility, but those interested in the prison, its violent history in US hands and its unenviable role as the graveyard of the Geneva Conventions refused to accept the rebranding.

In September 2012, the US and Afghan governments reached an agreement for the US to hand over control of Bagram to the Afghans, although it took months of legal wrangling until the Afghan authorities finally took control of the prison in March 2013.

As David Loyn noted in an article for the BBC, “Around 3,000 prisoners were handed over, and since then hundreds have been released after the evidence against them was assessed by an Afghan review process.” Others were prosecuted in a court that was set up at the prison.

The US authorities, however, told the Afghan government that some of the prisoners could not be released. 70 of the men handed over were given the status “EST,” meaning “Enduring Security Threat,” and, as the BBC put it, “There would be strong American protests if they were released.”

However, 65 others, seized since the agreement was reached in September 2012, have just been released by the Afghan government, prompting serious criticism by the US, which claimed that they were “dangerous insurgents” who should never have been released.

The US presented a dossier of detailed information about the men, including, as the BBC put it, “incriminating information from mobile phones, details of interviews with suspects including confessions, and pictures of bomb-making equipment.” As I explained to the BBC, however, the US has, from the beginning, had an extremely poor record when it comes to establishing accurate intelligence on the ground in Afghanistan — as can be readily seen from Guantánamo, and the classified military files released by WikiLeaks in 2011 — and the claims about these men are not necessarily trustworthy.

In addition, the US has no basis for criticizing Afghanistan when it comes to any aspect of the detention of prisoners, because, since the start of the “war on terror,” the US has persistently refused to hold prisoners in accordance with the Geneva Conventions, and has no right to be hectoring others.

From the beginning, for instance, as well as being subjected to savage brutality (in contravention of Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions), prisoners have been held without being screened to ascertain if they should have been seized or not. This screening is supposed to involve competent tribunals under Article 5 of the Geneva Conventions, held close to the time and place of capture, to tell the difference between civilians and combatants in situations in which both parties are not wearing uniforms. However, these tribunals were completely abandoned by the US after 9/11.

Moreover, once in detention, the men have had to wait, on average, for over a year for review boards to assess whether or not they should be released or whether they should continue to be held. Under President Bush, these reviews involved the prisoners having to make a statement before hearing the allegations against them, and under President Obama, although the review process was revised, it only copied the process at Guantánamo that the Supreme Court had found to be inadequate in 2008.

In addition, the US continues to hold around 60 foreign prisoners “in a corner of the facility that is still controlled by US troops,” as the BBC put it. Mostly Pakistanis, they also include men from other countries, who were seized in other countries and rendered to Bagram up to 12 years ago. Three of these men — Redha al-Najar, a Tunisian seized in Karachi, Pakistan in May 2002; Amin al-Bakri, a Yemeni gemstone dealer seized in Bangkok, Thailand in late 2002; and Fadi al-Maqaleh, a Yemeni seized in 2004 and sent to Abu Ghraib before Bagram — filed a habeas corpus petition in a US court years ago, which was granted by District Judge John D. Bates in May 2009, but was then successfully appealed by the Obama administration, when the inadequate review process mentioned above was implemented.

How this will all end is unknown at present. As the BBC noted, President Karzai “has taken a stridently anti-US line in several recent TV interviews, and refused to sign a deal to allow US troops to remain beyond the end of 2014, despite it being approved by Afghanistan’s highest representative authority — a loya jirga.”

It may be that President Karzai’s decision to release the men is part of this tussling with the US, or, perhaps, is part of the juggling required to survive politically in Afghanistan. However, as I told the BBC, it may also be that those examining the files for President Karzai genuinely concluded that the US could not back up its claims.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the four-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

February 12, 2014

US Appeals Court Rules that Guantánamo Prisoners Can Challenge Force-Feeding, and Their Conditions of Detention

In the latest news from Guantánamo, the court of appeals in Washington D.C. ruled yesterday that hunger-striking prisoners can challenge their force-feeding in a federal court — and, more generally, ruled that judges have “the power to oversee complaints” by prisoners “about the conditions of their confinement,” as the New York Times described it, further explaining that the judges ruled that “courts may oversee conditions at the prison as part of a habeas corpus lawsuit,” and adding that the ruling “was a defeat for the Obama administration and may open the door to new lawsuits by the remaining 155 Guantánamo inmates.”

In the latest news from Guantánamo, the court of appeals in Washington D.C. ruled yesterday that hunger-striking prisoners can challenge their force-feeding in a federal court — and, more generally, ruled that judges have “the power to oversee complaints” by prisoners “about the conditions of their confinement,” as the New York Times described it, further explaining that the judges ruled that “courts may oversee conditions at the prison as part of a habeas corpus lawsuit,” and adding that the ruling “was a defeat for the Obama administration and may open the door to new lawsuits by the remaining 155 Guantánamo inmates.”

In summer, four prisoners, all cleared for release since at least January 2010 — Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison, Ahmed Belbacha, an Algerian, Abu Wa’el Dhiab, a Syrian and Nabil Hadjarab, another Algerian, who was later released — asked federal court judges to stop the government from force-feeding them, but the judges ruled (see here and here) that an existing precedent relating to Guantánamo prevented them from intervening. The prisoners then appealed, and reports at the time of the hearing in the D.C. Circuit Court indicated that the judges appeared to be inclined to look favorably on the prisoners’ complaints.

As was explained in a press release by Reprieve, the London-based legal action charity whose lawyers represent the men involved in the appeal, along with Jon B. Eisenberg in California, the D.C. Circuit Court “held that the detainees should be allowed a ‘meaningful opportunity’ back in District Court to show that the Guantánamo force-feeding was illegal.” They also “invited the detainees to challenge other aspects of the protocol.”

Reprieve noted that the prisoners “have alleged that the force-feeding is both a violation of their rights, and gratuitously torturous,” although the judges “refused to ban force-feeding altogether, saying that for an immediate injunction ‘it is not enough for us to say that force-feeding may cause physical pain, invade bodily integrity, or even implicate petitioners’ fundamental individual rights.’” That quote came from Judge David Tatel, who added, “This is a court of law, not an arbiter of medical ethics … absent exceptional circumstances prison officials may force-feed a starving inmate actually facing the risk of death.” Judge Tatel also wrote, “Petitioners point to nothing specific to their situation that would give us a basis for concluding that the government’s legitimate penological interests cannot justify the force-feeding of hunger-striking detainees at Guantánamo.”

The judges also said that they “could not bar the doctors from following military orders in Guantánamo merely because they might be acting in violation of their medical ethics.”

Describing the current state of the hunger strike, Emad Hassan, a Yemeni who has been on a hunger strike since 2007, and has been force-fed for all that time, told Clive Stafford Smith in a recent conversation, “I am so dehydrated that my tongue becomes dry like tanned animal skin. They can’t find a vein to take my blood. They always strap me to the chair for force feeding, whether I am vomiting or not. The chairs slope backwards and because I have terrible kidney problems it is very painful.”

In another recent conversation, Shaker Aamer, speaking in anticipation of the court ruling, said, “This is one step towards justice. A general in charge of this place said they were going to make it less ‘convenient’ for us to go on a peaceful hunger strike. The way they force feed us is just torture, using the FCE [Forcible Cell Extraction] team to force us to the feeding room, using the torture chair to strap us down, using tubes that are too big for our noses, and putting the 120 centimeter tubes in and pulling them out forcefully twice each day, with each feeding. Instead of making matters worse here, they should treat us with respect, like human beings.”

Reprieve also noted that, at the latest count, 34 prisoners are involved in the latest hunger strike (first announced by Shaker Aamer in December), with 17 of the men being force-fed. This is one more than the 33 hunger strikers — with 16 men force-fed — reported by Shaker last month.

Responding to the ruling, Cori Crider, Reprieve’s strategic director, said, “This is a victory for the prisoners. The detainees have been on hunger strike for years now, with the simple, peaceful demand that they be given a fair trial or freedom. President Obama agrees that the Guantánamo regime is a blot on the reputation of America, and it is time he put an end to the torturous force feeding there.”

Jon B. Eisenberg said, “This decision puts a large crack in the edifice of lawlessness that has surrounded Guantánamo Bay since 2002. It’s a good day for the rule of law in America.”

Nevertheless, much of the mainstream media failed to get the positive message from the ruling. “Court turns down Guantánamo force-feeding challenge,” blared the Associated Press, noting that the court “rejected a bid for a preliminary injunction to stop force-feeding” at Guantánamo, which was true, but playing down the fact that two of the three judges had ruled that the prisoners “did have the right to challenge the force-feeding — rejecting two district court rulings that the judiciary didn’t have jurisdiction in the case.” Joining Judge Tatel (a Clinton nominee) in the majority ruling was Judge Thomas Griffith, an appointee of President George W. Bush, while the dissenting judge was Stephen F. Williams, an appointee of Ronald Reagan.

In fact, the rest of the AP report highlighted this successful aspect of the case, as Jon B. Eisenberg explained. In an email, he called it “a big win for us,” adding, “This decision establishes that the federal courts have the power to stop the mistreatment of detainees at Guantánamo Bay. The court of appeals has given us the green light to continue our challenge to the detainees’ force-feeding as being unconstitutionally abusive. We intend to do that.”

I’ll be watching further developments closely — not just, as Jon B. Eisenberg noted, in reference to the hunger strikers being force-fed, but also, more broadly, in terms of the green light that the court gave for prisoners’ complaints about the general conditions of their confinement, as noted by the New York Times. The fact that the judges ruled that “courts may oversee conditions at the prison as part of a habeas corpus lawsuit” is particularly satisfying, given that, in 2010 and 2011, after around three dozen prisoners had their habeas corpus petitions granted by the District Court, right-wing judges on the D.C. Circuit Court issued a number of rulings designed to make sure that it would be impossible for any more prisoners to have their habeas petitions granted. These new rules, ordering the lower court judges to regard anything the government presented as evidence as accurate with which were so successful that, since July 2010, no prisoner has had their habeas corpus petition granted. See my recently updated definitive Guantánamo habeas list (introduced here) for further information.

However, with D.C. Circuit Court judges overturning two of the only convictions in Guantánamo’s military commission trial system, in October 2012 and January 2013, largely discrediting the entire system, and with one of the court’s judges, Judge Harry T. Edwards, openly criticizing the baleful effects of his colleagues’ habeas rulings in two recent rulings (see here and here), it look as though perhaps, legally, the tide is finally turning …

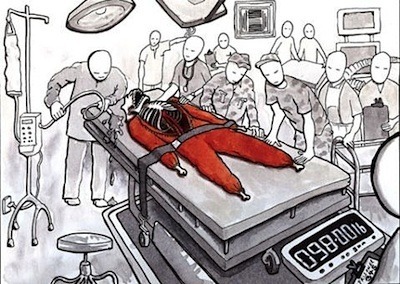

Note: Please see here for the website of Lewis Peake, the artist who drew the illustration at the top of this article in 2008, as part of a series of five illustrations based on drawings by Guantánamo prisoner Sami al-Haj, which the Pentagon censors had refused to allow the public to see. Reprieve commissioned Lewis Peake to reproduce the drawings based on descriptions of what Sami had drawn, and I reproduced them in my article, “Sami al-Haj: the banned torture pictures of a journalist in Guantánamo.”

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the four-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

February 11, 2014

Shaker Aamer Protest in London, Feb. 14, and Andy Worthington Talks About Guantánamo at Amnesty Conference in Leicester, Feb. 15, 2014

Please sign and share the international petition calling for the release of Shaker Aamer from Guantánamo.

Please sign and share the international petition calling for the release of Shaker Aamer from Guantánamo.

If you’re anywhere near Leicester on Saturday, February 15, 2014, and can spare a fiver to hear me speak, I’m the keynote speaker at Amnesty International’s East Midlands Regional Conference, where I will be discussing the “war on terror” prison at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, which I have been researching and writing about for the last eight years.

Following my recent experiences discussing Guantánamo during my two-week “Close Guantánamo Now” US tour, I will be talking about the monstrous history of the prison, 12 years since it opened, and explaining what has happened over the last few years — primarily involving obstacles to the release of prisoners that were raised by Congress, President Obama’s refusal to bypass Congress, even though he had the power to do so, and the promises to resume releasing prisoners that President Obama finally made last year, after the prisoners had embarked on a huge hunger strike that led to severe criticism of his inaction.

The Amnesty International conference takes place at the Friends Meeting House, 16 Queens Road, Leicester, LE2 1WP. It begins at 9.30am and runs until 5pm, and I’ll be speaking at 2pm. Entry is £5 (or £4 for the unwaged). For further information, please contact Ben Ashby by email or on 07794 441189.

The conference in Leicester takes place the day after campaigners in London — myself included — will be marking the 12th anniversary of the arrival at Guantánamo of Shaker Aamer, the last British resident in the prison, who remains held despite having been cleared for release in 2007, under President Bush, and again in 2009 by President Obama’s high-level, inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force. Shaker arrived at Guantánamo on the same day that his youngest child was born, who, of course, he has never seen. Just in case it is unclear, I will also be talking about Shaker Aamer at the conference.

The Save Shaker Aamer Campaign is holding a protest for Shaker outside MI6 headquarters, on Albert Embankment by Vauxhall Bridge in London, beginning at 1pm on Friday February 14, and running until 3pm, asking, in particular, whether MI6 is playing a major role in preventing Shaker’s release from Guantánamo, as has been claimed by Shaker’s lawyers at Reprieve, the London-based legal action charity founded by Clive Stafford Smith. See here for the Facebook page for Friday’s event.

In December, Clive Stafford Smith told the Observer that a letter written to Shaker by the British foreign secretary William Hague “reflects very strongly that the government is working hard for Shaker, but underlines that some elements are not playing it straight.” He added, “If there were no opposition to his release, he’d come home tomorrow.”

As I explained in an article at the time:

That opposition, as Stafford Smith made clear, appears to be the British security services. As the Observer described it, Reprieve believes they are “the stumbling block to [Shaker's] release,” with both MI5 and MI6 accused of making “defamatory statements” that have contributed to his long imprisonment without charge or trial –nearly seven years since he was first cleared for release under President Bush — and his torture, which was accepted by a judge in 2009, and led, earlier this year, to a three-day visit to Guantánamo by Metropolitan Police officers, who interviewed him about British complicity in his torture.

Last month, Shaker reported that the hunger strike at Guantánamo had resumed, with 33 men refusing food, 16 of whom were being force-fed, and just two weeks ago Clive Stafford Smith had a powerful op-ed published on CNN’s website, which I cross-posted here with my own commentary, in which — referring to the 77 prisoners, out of 155 in total, who are still held despite having been cleared for release (all but one since 2010) — he pointed out, “There can be no other prison in the world where 50 percent of the inmates are told: ‘You are cleared to leave, but you cannot go.’”

According to the latest report from Guantánamo, 34 prisoners are now on a hunger strike, with 17 being force-fed.

Note: For a detailed analysis of the potential obstacles to Shaker’s release, please see this article in the Daily Mail last April by David Rose.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the four-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

February 10, 2014

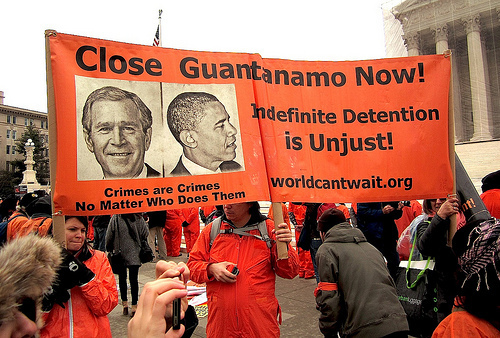

Video: Close Guantánamo Now – Andy Worthington and Dennis Loo at Cal Poly, Pomona, Jan. 17, 2014

On Friday January 17, 2014, as the last public event of my two-week US tour calling for the closure of the prison at Guantánamo Bay, I spoke at a wonderfully well-attended event at California State Polytechnic (Cal Poly) in Pomona, California, attended by several hundred students and arranged by Dennis Loo, a professor of sociology at the university, and a member of the steering committee of the World Can’t Wait, the campaigning group whose national director is Debra Sweet, and who I am enormously grateful to for organizing the tour.

On Friday January 17, 2014, as the last public event of my two-week US tour calling for the closure of the prison at Guantánamo Bay, I spoke at a wonderfully well-attended event at California State Polytechnic (Cal Poly) in Pomona, California, attended by several hundred students and arranged by Dennis Loo, a professor of sociology at the university, and a member of the steering committee of the World Can’t Wait, the campaigning group whose national director is Debra Sweet, and who I am enormously grateful to for organizing the tour.

The event, I’m glad to note, was filmed, and the video is posted below, via YouTube. My talk begins around 10 minutes into the video, after Dennis introduced the event by reading out World Can’t Wait’s full-page advertisement that ran in the New York Times last year, and it ended at around 31 minutes.

In my talk, I ran through the history of the prison — explaining the horrible innovation of holding men neither as criminal suspects nor as prisoners of war protected by the Geneva Conventions, how torture was authorized at the prison (through George W. Bush’s Presidential memo of February 7, 2002, which I recently wrote about here), and what types of torture techniques were used on the prisoners.

I then moved on to explain why Guantánamo is still open, despite President Obama’s promise to close it on his second day in office in January 2009, as I did throughout my tour — explaining how he appointed a high-level, inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force to review the cases of all the prisoners, and how he accepted an alarming recommendation that 48 men should continue to be detained without charge or trial on the extremely dubious and thoroughly unacceptable basis that they are too dangerous to release, even though insufficient evidence exists to establish this in a courtroom.

I also spoke about the serious obstacles to the release of prisoners that were raised by Congress, which were certainly significant, although a waiver in the legislation (the National Defense Authorization Act) always allowed the president to bypass Congress if he wished to, and if he regarded it as being in the national security interests of the United States — something that President Obama eloquently confirms to be the case every time he speaks about Guantánamo. The fact that he failed to do so indicates that he was unwilling to spend political capital freeing prisoners and fulfilling his promise to close the prison.

I also made a particular point of stressing how profoundly unacceptable it is for the task force to have cleared for release 76 of the remaining 155 prisoners over four years ago, and yet for these men still to be held, and explained how 55 of these men — plus another man just cleared for release via a Periodic Review Board — are Yemenis, who continue to be held because of fears about the security situation in Yemen, despite the fact that no justification can be made for holding cleared people on the basis of their nationality alone.

There was much more in my talk, and I hope you have the time to watch it, and also to watch Dennis’s talk (in which, amongst other topics, he provided a detailed explanation of the worrying provisions in the National Defense Authorization Act mandating military detention without charge or trial for terror suspects), and the extremely interesting Q&A session that followed, beginning at 53 minutes. I’m delighted to report that the majority of the students stayed for the Q&A session, and that many of them asked questions which showed that the event had had a significant impact.

This has also been confirmed through reports submitted by students after the event. I hope to be able to present a collection of these comments in the near future, but in the meantime I’m delighted that two students’ analyses of the event have been made available via Dennis.

The first comes from an article Dennis wrote, analyzing the work of the educational psychologist Benjamin Bloom, who, as he put it, “described two basic stages to cognitive development. The first and lower stage consists of recognition and recall, comprehension and application. The second, and higher, stage consists of analysis, synthesis and evaluation. Higher education should be designed to ensure that students achieve this higher stage.”

Dennis added:

Evaluation is the highest stage of cognitive development in Bloom’s taxonomy. It builds upon all of the preceding. It is the ability to assess the strengths and weaknesses of an argument and compare and contrast different arguments. It is Meta-Analysis. Without this, you would be unable to reach a true independent judgment. Instead, you would have to accept the opinions of others. A plethora of information is available today, and information is, of course, important. But what is even more important is the ability to sift through the information and sources and the ability to figure out what’s valid and what is not.

He also stated:

If you don’t receive training — and this does require training as it doesn’t happen to people spontaneously — in how to recognize and evaluate the underlying assumptions and value judgments of framing, then you are vulnerable to being roped into accepting something that you would otherwise not have accepted. That is why you cannot really think on your own and draw your own conclusions if you aren’t schooled in how to pierce the surface appearances of things and examine their value-laden assumptions. As an illustration of this, around 240 students went to our campus program “Close Guantánamo Now!” on January 17, 2014, and were shocked to learn that what they had been told was going on and therefore thought was going on — that Guantánamo housed the “worst of the worst” of terrorists, known and proven to be terrorists — was untrue.

Dennis then quoted from a paper that a student, Erin Frame, wrote in response to the “Close Guantánamo Now!” program. She wrote:

[M]ost of the information I was given by Dr. Loo and Andy Worthington was content that I had not come across before. Before I attended the event, my knowledge of the prison at Guantánamo Bay was extremely limited. The only thing I had heard about this place was that its prisoners consisted of dangerous terrorists. I had no idea that the majority of these people were innocent, captured and detained with no substantial evidence, and tortured. I was not aware that the families of these people were not even notified where they were or why they had been taken. The mainstream media was responsible for all of the information I received on the prison, and it was hardly sufficient. The mystery and false information surrounding Guantánamo Bay compares to that which surrounded the invasion of Iraq. Both instances involve breaking laws and hurting innocent people and in both situations, the American public was poorly informed.

When the Bush administration broke international law and committed the supreme war crime by invading a nation that had not threatened it, me and millions of Americans were not aware that this was illegal. I remember being confused as to why the US was at war, but believed at least that it was to fight terrorists just like I believed terrorists were being held at Guantánamo Bay. In both instances, I was wrong. Now that I have been enlightened to some of the truths behind Guantánamo Bay, I am aware that I now belong to a small minority of other informed people while the rest of the American citizenry remain shrouded in lies. I am aware that in order to take sufficient steps towards closing Guantánamo Bay, a much larger proportion of the population needs to be adequately informed about its illegality. Perhaps then, US citizens can put enough pressure on President Obama to leave him no choice but to shut down the establishment.

Dennis added, “This student’s self-description of having ‘extremely limited’ knowledge about Guantánamo (and about Iraq before taking her current class with me) matches the situation for the vast majority of Americans who are ‘shrouded in lies.’”

Below is another student’s perspective on the event:

A student’s detailed response to the “Close Guantánamo Now!” event at Cal Poly, Pomona, January 17, 2014

The terrorist prison at Guantánamo Bay is a little discussed topic in American society today. The first time I ever even heard of this prison was in the comedic movie “Harold and Kumar Escape from Guantánamo Bay.” The fact that the first many people heard of this prison was in a comedy movie speaks volumes about the knowledge that is made readily available to the general public. Today the prison at Guantánamo is an extremely well known blemish on American society. But while it is well known do we as a society know enough to form an opinion on the matter? I know for a fact that prior to the Guantánamo event I did not have the knowledge to form an opinion on the matter, but after hearing the speakers at the event the basic knowledge has been given to me so I can research further and build upon this knowledge to form my own opinion.

The first point brought up in the event and one that I believe is the most important is the fact that if President Obama wanted to close down Guantánamo Bay he could do it today with his power as commander and chief. On his second day in office President Obama stated that he would shut down Guantánamo Bay and yet he has not done so yet. In fact he seems to have just tried to keep everything about it kept quiet. It may end up being that President Obama sees out his second term without fulfilling this promise to the American people. The reason why he should shut it down is the second point I would like to bring from the event and that is that the acts that our government is committing at Guantánamo Bay directly go against the rules outlined by the Geneva Convention. The Geneva Convention was in response to the Second World War and the rules it put in place were to save humans from themselves. Humans can be the most violent and evil species on the planet as seen many times by our actions during war time throughout history. Look at Vlad the Impaler or Hitler, both violently murdered people just for being on the opposite side of what they believed to make an example out of them.

The Geneva Convention was [intended] to make sure that instances like this were to never happen again. It specifically stated that Prisoners of War were not to be tortured. Yet we see in Guantánamo Bay that these prisoners are tortured in many different ways including sleep deprivation and force feeding. Bush was able to partially get around this by calling these prisoners “illegal enemy combatants” instead of Prisoners of War. None of these men that are being held in Guantánamo Bay has ever faced a trial either and yet American law dictates that we have the right to a trial by jury. These prisoners who are sitting in an American prison do not have the rights that are promised in America. How does the government get around this?

President Bush was able to use a technical gray area to avoid these issues. By having this site at Guantánamo Bay in Cuba, Bush was able to find a loophole because the prison is not on American soil. This gave the government wiggle room that they needed to be able to justify the treatment of prisoners on a legal basis because our judiciary system does not have the authority to rule on issues that are on the soil of other countries. The majority of the prisoners that make up the population of Guantánamo Bay were kidnapped from their countries and are held without any evidence and have been held for in some cases 12 years. These prisoners have not even had their cases seen by a judge let alone a trial court with a jury. [...]

The fact that there are currently 56 men sitting in Guantánamo Bay that have been cleared to be released who have not yet been released should spark outrage in our society yet until I watched the event I had no idea about these men. President Obama himself put a ban on releasing these men back into the world and even after he lifted the ban these men still rot away in the prison. This was just one of the many things that I had not heard before the event. I had almost no knowledge of Guantánamo Bay because largely everybody tries to keep it hush hush because we don’t want to spark outrage. The only things that are told to the general public are that these men are all a danger to society and that they deserve to be in prison. These statements insinuate that there is extensive evidence implicating all of these men to serious terrorist activities yet, as we can see based on the imminent release of 56 prisoners due to lack of evidence, this is not the case. This is probably the biggest detail that I thought I knew before as compared to now. The way the government tells us to think about Guantánamo Bay and those who are in it serves only them in that the general population will not react negatively if we keep believing that these men are all out to see America destroyed and Americans slaughtered by the thousands.

In short it became apparent to me that the public is not well enough informed about Guantánamo Bay to form their own opinions. Based on my own personal knowledge both before and after watching the event I can say that the general public has been done a great disservice by our government trying to keep everything that is done at Guantánamo a secret. For everything we think we know about the prison there are probably another three things that the government has managed to keep hidden from us.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the four-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

February 8, 2014

Torture Began at Guantánamo with Bush’s Presidential Memo 12 Years Ago

I wrote the following article for the “Close Guantánamo” website, which I established in January 2012 with US attorney Tom Wilner. Please join us – just an email address is required to be counted amongst those opposed to the ongoing existence of Guantánamo, and to receive updates of our activities by email.

I wrote the following article for the “Close Guantánamo” website, which I established in January 2012 with US attorney Tom Wilner. Please join us – just an email address is required to be counted amongst those opposed to the ongoing existence of Guantánamo, and to receive updates of our activities by email.

This is a grim time of year for anniversaries relating to Guantánamo. Two days ago, February 6, was the first anniversary of the start of last year’s prison-wide hunger strike, which woke the world up to the ongoing plight of the prisoners — over half of whom were cleared for release by a Presidential task force over four years ago but are still held.

The hunger strike — which, it should be noted, resumed at the end of last year, and currently involves dozens of prisoners — forced President Obama to promise to resume releasing prisoners, after a three-year period in which the release of prisoners had almost ground to a halt, because of opposition in Congress, and President Obama’s unwillingness to overcome that opposition, even though he had the power to do so.

To mark the anniversary, a number of NGOs — the ACLU, Amnesty International, the Center for Constitutional Rights, Human Rights First and Human Rights Watch — launched a campaign on Thursday, “Take a Stand for Justice,” encouraging people to call the White House (on 202-456-1111) to declare their support for President Obama’s recent call for Guantánamo to be closed for good (in his State of the Union address, he said, “With the Afghan war ending, this needs to be the year Congress lifts the remaining restrictions on detainee transfers and we close the prison at Guantánamo Bay”). Please call the White House if you can, and share the page via social media.

Yesterday, February 8, was the 12th anniversary of the founding document of President Bush’s torture program, announced in a short Presidential memo entitled, “Humane Treatment of Taliban and al-Qaeda Detainees.”

This was the disturbing document in which President Bush declared that “none of the provisions of [the] Geneva [Conventions] apply to our conflict with al-Qaeda in Afghanistan or elsewhere through the world, because, among other reasons, al-Qaeda is not a High Contracting Party to Geneva.” He added, “I determine that the Taliban detainees are unlawful combatants and, therefore, do not qualify as prisoners of war under Article 4 of Geneva. I note that, because Geneva does not apply to our conflict with al-Qaeda, al-Qaeda detainees also do not qualify as prisoners of war.”

As I explained in an article marking the 10th anniversary of this memo in 2012:

This was the rationale for holding prisoners neither as criminal suspects or as prisoners of war, but as a third category of human being, without any rights. [This] paved the way for the use of torture, as people with no rights whatsoever had no protection against torture and abuse, and to this end the most alarming passage in the memorandum is the President’s claim that “common Article 3 of Geneva does not apply to either al-Qaeda or Taliban detainees because, among other reasons, the relevant conflicts are international in scope and common Article 3 applies only to ‘armed conflict not of an international character.’”

As I also explained two years ago:

President Bush claimed that the prisoners would be “treated humanely and, to the extent appropriate and consistent with military necessity, in a manner consistent with the principles of Geneva,” but it was a meaningless addition. By refusing to accept that everyone seized in wartime must be protected from torture and abuse, and by removing the protections of common Article 3 from the prisoners, which prohibit “cruel treatment and torture,” and “outrages upon personal dignity, in particular humiliating and degrading treatment,” President Bush opened the floodgates to the torture programs that were subsequently developed, both for use by the CIA, and at Guantánamo.

The CIA’s torture program — for use in the agency’s global network of secret torture prisons, or “black sites” — was subsequently authorized, on August 1, 2002, through a series of memos that will forever be known as the “torture memos,” written by John Yoo, a lawyer close to Dick Cheney, who worked in the Office of Legal Counsel, a branch of the Justice Department that is supposed to supply impartial legal advice to the executive branch. Instead, Yoo claimed that torture was not torture, and provided the “golden shield” that Bush administration officials used, and still use to try to prevent anyone holding them accountable for their actions.

Later, on December 2, 2002, defense secretary Donald Rumsfeld approved his own torture program for use at Guantánamo. This was originally intended for use on just one prisoner, Mohammed al-Qahtani, a Saudi considered to be an intended 20th hijacker for the 9/11 attacks, who was tortured for several months at the end of 2002 and the start of 2003 (see the harrowing interrogation log here, which runs from November 23, 2002 to January 11, 2003).

The torture of Mohammed al-Qahtani is the only example of torture admitted to by a senior Pentagon official, when, just before President Bush left office, Susan Crawford, who oversaw the military commissions at Guantánamo, told Bob Woodward of the Washington Post, “We tortured Qahtani. His treatment met the legal definition of torture.”

Al-Qahtani, however, was not the only prisoner tortured at Guantánamo. As Neil A. Lewis reported for the New York Times in a powerful article in January 2005:

Interviews with former intelligence officers and interrogators provided new details and confirmed earlier accounts of inmates being shackled for hours and left to soil themselves while exposed to blaring music or the insistent meowing of a cat-food commercial. In addition, some may have been forcibly given enemas as punishment.

While all the detainees were threatened with harsh tactics if they did not cooperate, about one in six were eventually subjected to those procedures, one former interrogator estimated. The interrogator said that when new interrogators arrived they were told they had great flexibility in extracting information from detainees because the Geneva Conventions did not apply at the base.

Although these specific techniques eventually came to an end, the Bush administration’s official use of torture did not come to an end until June 2006, when, in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, the Supreme Court reminded the Bush administration that common article 3 of the Geneva Conventions applied — and applies — to all prisoners held by US forces. Just over two months later, 14 “high-value detainees” were moved from secret CIA prisons to Guantánamo, and President Bush announced that the “black sites” — whose existence he had previously denied — had been closed down.

Torture, of course, did not come to an end. Many of the torture techniques migrated to Appendix M of the Army Field Manual, which was reissued on September 6, 2006, the very same day that the 14 “high-value detainees” arrived at Guantánamo, and the “black sites” were closed down.

More generally, it is worthwhile considering that the very function of Guantánamo is torture, as a place devoted to open-ended, and possibly unending imprisonment without charge or trial. In October 2003, this alarmed the International Committee of the Red Cross to such an extent that, although the organization is not supposed to make public statements, as part of its access arrangements, Christophe Girod, the senior Red Cross official in Washington D.C., told the New York Times, “The open-endedness of the situation and its impact on the mental health of the population has become a major problem.”

He added, as the Times put it, that “in meetings with members of his inspection teams, detainees regularly asked about what was going to happen to them.”

“It’s always the No. 1 question,” he said. “They don’t know about the future.”

Ten years and four months on from Mr. Girod’s comments, it is difficult to gauge quite how much more crushing the impact on the prisoners’ mental health has been in the intervening years, not just through their ongoing indefinite detention without charge or trial, but also as a result of the quashed hopes raised by President Obama’s election in 2009, and, most horribly, the process whereby, in January 2010, 76 of the remaining 155 prisoners were told that they had been cleared for release, and would be released as soon as the necessary arrangements could be made — but they have not been released.

To return to “Take a Stand for Justice,” the campaign launched on Thursday, the time is now to pick up the phone to the White House and to tell President Obama that the cleared prisoners — those 76 men plus a 77th recently cleared for release by a Periodic Review Board — must be released as soon as possible, that justice must be delivered as swiftly as possible to the other 79 men, who should be tried or released, and that no further delays are acceptable.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the four-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

February 6, 2014

Updated: My Definitive List of the Guantánamo Habeas Corpus Results

See the updated Guantánamo habeas list here.

Sometimes life takes us down unexpected routes, and yesterday, while looking for links for my last article, a transcript of a talk I gave in Los Angeles during my recent US tour calling for the closure of the prison at Guantánamo Bay on the 12th anniversary of its opening, I found myself visiting a page I first created in May 2010, entitled, “Guantánamo Habeas Results: The Definitive List.”

The page is a list of all the prisoners whose habeas corpus petitions were ruled on by judges in the District Court in Washington D.C. following the Supreme Court’s important ruling, in June 2008, in Boumediene v. Bush, granting the prisoners constitutionally guaranteed habeas corpus rights. At the time I created the list, there had been 47 rulings, and in 34 of those cases, after reviewing all the evidence, the judges concluded that the government had failed to demonstrate that they were connected in any meaningful manner with either al-Qaeda or the Taliban, an ordered their release.

This was humiliating for those who sought to defend Guantánamo, especially as the habeas hearings involved a low evidentiary hurdle — requiring the government to establish its case through a preponderance of the evidence rather than beyond any reasonable doubt. It was, moreover, a vindication for those like myself and some other journalists, as well as lawyers for the men, NGOs and others concerned by the existence of Guantánamo, like Lt. Col. Stephen Abraham, who had worked on the tribunals at Guantánamo, who had long maintained that the supposed evidence against the men was flimsy and untrustworthy, in large part because it was gathered using torture or other forms of coercion, or, in some cases at Guantánamo, because certain prisoners were bribed with better living conditions if they told lies about their fellow prisoners.

From the high point for the Guantánamo habeas process, which I marked with a series of articles under the heading, “Guantánamo Habeas Week,” a backlash soon began, engineered by conservative judges in the D.C. Circuit Court who, beginning in January 2010, issued rulings, following appeals by the government, designed to prevent the lower court from evaluating the evidence objectively, and ordering the release of dozens of prisoners.

I recorded these generally baleful decisions, in which the D.C. Circuit Court, as I put it, “demonstrated [a] commitment to eroding the District Court’s independence — and, for the most part, its fairness and impartiality — with increasingly aggressive assertions that have less to do with due process than with a kind of overreaching, authoritarian, right-wing ideology,” in two articles in the summer of 2010, “Habeas Corpus: Prisoners Win 3 out of 4 Cases, But Lose 5 out of 6 in Court of Appeals,” Part One and Part Two.

I then watched aghast as, under the new rules, no more prisoners were able to have their habeas petitions granted. Since July 2010, all the habeas petitions ruled on — eleven in total — have been won by the government, as have around two dozen appeals. In addition, lawyers’ efforts to deal with this by appealing to the Supreme Court have been in vain, as case after case has been turned down, with the Supreme Court refusing to revisit Boumediene, and, effectively, allowing prisoner detention policies to be dictated by a handful of conservative, ideologically driven appeals court judges, whose intention has been to destroy habeas corpus as a meaningful remedy for the men held at Guantánamo.

This process culminated in a thoroughly depressing ruling in October 2011, in which the D.C. Circuit Court overturned the successful habeas petition of Adnan Farhan Abdul Latif, a Yemeni with mental health issues, who had his habeas petition granted in July 2010, and had also been cleared for release by a military review board under President Bush, and by President Obama’s high-level, inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force in January 2010. See also this analysis by Sabin Willett, one of the Guantánamo lawyers.

In that ruling, the D.C. Circuit Court told the lower court that everything the government came up with — however risible — had to be given the presumption of accuracy unless the prisoners themselves could prove otherwise, even though, in Guantánamo, they are largely deprived of the means to do so.

In September 2012, Latif died at Guantánamo, reportedly by committing suicide, but no one in authority has had to answer for the failure to release him, and the D.C. Circuit Court has continued to set policy and turn down appeals, largely unnoticed by the mainstream media.

In revisiting my Guantánamo habeas page, I realized that I had largely failed to update it for some time, and set about remedying that, checking out appeal after appeal that was lost, and often finding that only a few specialist legal blogs had dealt with this procession of dismal rulings, even though the gutting of habeas corpus for the Guantánamo prisoners ought to be a matter of national concern.

The only glimmer of hope has come in the last few months, with dissenting opinions submitted by Circuit Judge Harry T. Edwards last June, in the case of Abdul al-Qader Ahmed Hussain (which I wrote about in an article entitled, “Judge Calls for An End to Unjust Provisions Governing Guantánamo Prisoners’ Habeas Corpus Petitions“), and, in December, in the case of Abdul Razak Ali, an Algerian, which I have not yet written about, although I wholeheartedly recommend a detailed article about the case by Linda Greenhouse in the New York Times.

I hope that Judge Edwards’ dissent signifies that the tide is turning against the decision by a handful of judges to eradicate habeas corpus for the Guantánamo prisoners, but I’m not holding my breath. Guantánamo has, in general, been a place where, from the moment the prison opened, the law was sent to be butchered, and, apart from that honeymoon period after Boumediene when dozens of prisoners were having their habeas petitions granted and were being freed, the only sure way out of Guantánamo is through political maneuvering — or in a coffin.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the four-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

February 5, 2014

Close Guantánamo Now: Transcript of Andy Worthington’s Speech at an Inter-Faith Event in Los Angeles, January 15, 2014

On January 15, as part of my two-week “Close Guantánamo Now” US tour, marking the 12th anniversary of the opening of the “war on terror” prison at Guantánamo, I was the keynote speaker at a lunch event in a Methodist church in Los Angeles, which was convened by Interfaith Communities United for Justice and Peace (ICUJP), a Los Angeles area interfaith coalition who describe themselves as being “united behind the message that religious communities must stop blessing war and violence.”

On January 15, as part of my two-week “Close Guantánamo Now” US tour, marking the 12th anniversary of the opening of the “war on terror” prison at Guantánamo, I was the keynote speaker at a lunch event in a Methodist church in Los Angeles, which was convened by Interfaith Communities United for Justice and Peace (ICUJP), a Los Angeles area interfaith coalition who describe themselves as being “united behind the message that religious communities must stop blessing war and violence.”

Although the event was not filmed, an audio recording was made by Jenny Jiang, a journalist who runs a news site, “What the Folly?” which includes transcripts she makes of various talks and speeches. Jenny got in touch with me before my visit to ask for permission to record and transcribe my talk, and I was delighted that she wanted to do so.

Jenny subsequently published the transcript of my talk (unscripted as always), in which I ran through the history of Guantánamo, discussed the various legal challenges that have taken place over the years, discussed President Obama’s failure to close the prison as he promised, and the reasons for that failure, and also addressed where we are now, and what we can do in the coming year to keep the pressure on President Obama and on Congress to try and ensure that the prison is finally closed.

I’m cross-posting my own version of the transcript below, which I hope you have time to read, and to share if you find it interesting, and if you are interested, you might also like two other transcripts on Jenny’s site, which I have not cross-posted below — the first is a transcript of the Q&A session that followed my talk, when I shared the platform with the Rev. Dr. Art Cribbs of CLUE-LA (Clergy and Laity United for Economic Justice) and Edina Lekovic of the Muslim Public Affairs Council, and the second is an interview Jenny conducted with me straight after the event, when she asked some follow-up questions raised by my talk and as a response to my work in general.

I’d just like to thank Jenny once more for her attention to Guantánamo, and for her thoughtful and well-researched questions. Below is the transcript, which begins after I had been introduced by Andy Griggs of ICUJP, who had spent several years trying to arrange for me to talk in Los Angeles, a plan that finally came to fruition with the help of the campaigning group the World Can’t Wait and the “Close Guantánamo Now” tour that they sponsored.

Transcript of Andy Worthington’s speech at an interfaith luncheon in Lose Angeles on Jan. 15, 2014

By Jenny Jiang for What the Folly?, January 20, 2014

So you may have figured out by now from the funny accent that Andy [Griggs] wasn’t kidding, that I am actually from the UK, and it is strange still to me to this day that I became so deeply involved in the story of Guantánamo. But Guantánamo is a story that involves human rights, and human rights are about all of us, and what we have been seeing at Guantánamo is that some people have rights and other people don’t.

Standing up here on this podium as a foreigner, I’m of course aware that there are foreigners at Guantánamo, but not United States citizens — although that’s not to say that United States citizens are always treated well by their government. But the prison at Guantánamo is very specifically somewhere for holding non-US citizens outside the law. That was the intention when the prison was opened.

I came to this story about eight years ago, actually, and I was interested in Guantánamo as many people around the world had become interested in Guantánamo as the story of this strange prison that had been opened by the Bush administration. It was alarming to many people from the day that it opened, although I understand that it appeared to be less alarming for some Americans because there were men in orange jumpsuits and people in US prisons wear orange, but around the world a lot of people were troubled from the very beginning.

These images of kneeling people with their ears covered and their eyes covered, hooded — the whole thing didn’t seem to be something that fitted with any established notions of what it is that you do when you deprive people of their liberty. It didn’t seem to fit with the notion of taking people off the battlefield at wartime and holding them in accordance with the Geneva Conventions. And you know, it didn’t do that because that isn’t what it was.

What this was was an experiment in holding people with no rights whatsoever, and the intention, when the Bush administration opened it, was that these men would be held without rights forever.

Legal challenges

It actually took nearly two and a half years of the prison being open before lawyers who had started working on the prisoners’ behalf almost as soon as the prison opened managed to get the case of the prisoners in front of the Supreme Court. So it had bounced around the lower courts for a while and made it to the Supreme Court in June 2004, when the Supreme Court said to the Bush administration, unusually, “You know, these are guys that you’ve captured in wartime but there is no way that they can establish their innocence if they claim that they were seized wrongly. There’s no means by which they can have that claim listened to. You have sealed them in Guantánamo with no way out.”

So they gave the prisoners habeas corpus rights. That was extremely important in one way which remains so to this day. It was important at that time because it broke the secrecy that surrounded Guantánamo up to that point. For the Bush administration to do what it wanted to do with people that it held without rights, which involved torturing and abusing them, it was necessary for them to have absolute secrecy, that no one outside of the people they trusted would be allowed in — except for representatives of the International Committee of the Red Cross who are sworn to secrecy, although on occasion they have spoken about what they saw at Guantánamo. But that’s a side issue.

When the lawyers were allowed into Guantánamo because of the habeas ruling in Rasul v. Bush in June 2004, it pierced that secrecy once and for all, and lawyers have been there ever since, however much they’re messed around by the authorities.

Now, it turned out that the Bush administration was really unwilling to accept the decision of the Supreme Court, so they worked with Congress to find ways to pass new legislation to repeal the rights that the prisoners had [the Detainee Treatment Act of 2005 and the Mlitary Commissions Act of 2006]. They [the prisoners' habeas rights] were not actually reinstated by the Supreme Court until another round of to-ing and fro-ing and the ruling that was made in June 2008 [Boumediene v. Bush] that the prisoners had constitutionally guaranteed habeas corpus rights. That was an interesting ruling. It involved the Supreme Court saying that Congress had acted unconstitutionally in trying to deprive the men of the habeas rights that they said they had four years before.

By this point, the prison’s been open seven and a half years and finally the men got their habeas corpus rights, and court cases then proceeded to the district court in Washington, D.C., where judges impartially looked at the government’s supposed evidence, and we had what legally was the only golden period in Guantánamo’s history where, in late 2008, 2009 and into 2010, several dozen prisoners — three dozen prisoners, slightly more — had their habeas corpus petitions granted by US district court judges, who looked impartially at what purported to be evidence on the part of the government. The government was given a very low hurdle to establish that these people were connected in any kind of meaningful manner whatsoever with Al-Qaeda or the Taliban. And judges were throwing out case after case, saying to the government, “You have not established the case that you were making to detain these people and to deprive them of their liberty.”

Now, unfortunately, what happened after these initial successes was that the conservative judges in the court of appeal in Washington, D.C. — the next layer up from the district court judges making these habeas rulings — decided that they were profoundly unhappy with the decisions being made and, for political and ideological reasons, re-wrote the rules governing the habeas corpus petitions to make sure that no more habeas corpus petitions would be granted.

They told the lower court to accept pretty much everything the government claimed unless the prisoners were able to prove the evidence was wrong. And they were advocating the acceptance of material that was so flimsy — this was not evidence that the prisoners, obviously, were in a position to challenge very easily. They were stuck in Guantánamo with very little access to anything to try and prove that what the government was saying, however useless, was wrong.

So that was a very dark process that was undergone in the D.C. Circuit Court. And many of the prisoners who lost their petitions subsequently, some of the prisoners who had their successful petitions vacated or reversed, tried to appeal to the Supreme Court. This has happened for the last few years — a variety of different petitions to the Supreme Court. And the Supreme Court has turned down all of those. That’s really not a very good reflection on what the Supreme Court has done in these cases either.

How I became involved in uncovering the truth about Guantánamo

So, I kind of started off there with a bit of a legal history that I hope that you find useful. But to go back to where we were when the habeas corpus rights were first granted by the Supreme Court, and the administration tried to overturn that with new legislation, the first lawyers were in the prison, and they were very significant in getting the stories out.

To those of us who were interested in listening, it was clear that there was something terribly wrong going on at Guantánamo. And these stories also came out from former prisoners. Now I don’t know if any of you have been been watching this story from the beginning but, in 2004 and 2005, British prisoners were released from Guantánamo, the British nationals. And nearly all of them then spoke extensively in the British press about what had happened to them.

And the pieces of the jigsaw puzzles started to come together. People were telling very similar stories about the kind of things that had happened to them, and the kind of things that were happening to them were terrible. There was the initial extremely brutal treatment in Afghanistan at the prisons that were in Bagram and Kandahar. There were clear stories emerging of people who had been murdered, particularly in Bagram.

And then there was the Guantánamo situation where, in some ways, things appeared to be slightly more clinical, but there were also episodes of extreme brutality there as well, because there were a number of different agencies involved and some particular groups that were responsible for breaking the prisoners introduced [via Donald Rumsfeld] a number of torture techniques to Guantánamo. which were applied to a significant number of prisoners. The only figure that I’ve seen on this is that an former interrogator told the New York Times in 2005 that it applied to about 1 in 6 of the prisoners. So, over 100 prisoners.

And this was the program of prolonged sleep deprivation, where they moved prisoners from cell to cell every few hours for periods of weeks or even months, which they euphemistically and cynically called the “frequent flier program” — perhaps an example of what they thought passed for humor. The other techniques that were used on the prisoners: they were short-shackled in painful positions; they had loud music blasted at them; noise was used on them; forced nudity; if they had phobias that the psychologists had identified, those would be played on them.

It was an absolutely terrible period in Guantánamo’s history, and stories of what happened here came out through all kinds of different groups. Afghan prisoners, who probably were not speaking Arabic, for example — I remember an Afghan prisoner came out and said, “They stood me in front of the cold machine hundreds of times.” And he’s obviously talking about how he was subjected to this — they either turned the heat up really high or they turned the heat down really low, and he was subjected to that. So, different elements of it were coming out from all over the place to show that this was a coherent story and something awful had happened, and I began trying to find out who the prisoners were in, I think, September 2005, and I went through what documentation was available — via released prisoners, and there were at the time estimates of who was there. Lists had been put together of people who might possibly be there. The Washington Post did one and a British group called Cageprisoners did another one.

The prison had been open for nearly four years and still the US government hadn’t told the world who was being held there. There were parents of disappeared people all around the Middle East and other countries who didn’t know whether their sons had been killed. They didn’t know if their sons were in Guantánamo. Some of them only found out that their children were in Guantánamo when the Pentagon lost a freedom of information lawsuit and was obliged to release 8,000 pages of documents in the spring of 2006, which for the first time told the world the names and nationalities of the men held in Guantánamo.

March 2006. So four years and two months after the prison opened, the Bush administration finally — and under duress — let the world know who was held there. The 8,000 pages that were released included the allegations — the unclassified allegations — against the prisoners, and thousands of pages of transcripts from tribunals that had been held at Guantánamo, the very one-sided tribunals convened by the Bush administration after they lost the first habeas corpus decision in the Supreme Court. And they didn’t want to oblige by giving the prisoners habeas corpus rights. They said, “We’ll hold an internal review process to assess whether these men are enemy combatants and we can continue to hold them.”

And they held the process and decided that most of them were. They were horribly one-sided. The men didn’t have legal representation; they were just given a personal representative from the military who may or may not have wished to represent their interests. They weren’t allowed to see or hear what purported to be the classified evidence against them. And as I said, the major intention of it was to rubber-stamp their prior designation as enemy combatants, not to objectively assess whether or not they should have been seized in the first place or whether there were any grounds for imprisoning them.

But, in these thousands of pages of documents, there were transcripts made of what the prisoners said when they had the opportunity to go in front of a tribunal of US military officers and explain their story, and it turned out when I started reading them, some of these people just leapt out of the page at me. Some of them were, you know, they were so angry or they were so funny or they were so sympathetic or they were so insightful. There were all kinds of stories leaping out to me.

You know, it was when I began to want to tell their story. So having started before their names and nationalities were released, which was really difficult to find out, apart from the ones who had been freed, suddenly I had all of this information in front of me. And I then, for some reason, decided that I couldn’t sleep very much for 14 months and had to write a book about it, which I did. But I had no idea when I was doing it that nobody else was going to do it. I thought that one of the major newspapers in the United States would assign people to cover this important story, but they didn’t.

I mean, it wasn’t an easy job going through all of this documents and coming up with a narrative, which is essentially what I did when I started going through the stories. I realized that were captured in different places. They were captured at different times. And I kind of went through it [the documentation] and took it all apart in that way. Human Rights Watch did tell me once that they’d put a couple of researchers on it but they couldn’t work out how to do it, but they were the only people that I had heard about who made an attempt to analyze it.

So I did that and I wrote a book, which I only had three copies of today and they’ve all gone. Sorry about that. You can, I think, buy it on Amazon. It’s called The Guantánamo Files, and I’m Andy Worthington, but you probably know that, and if you Google those things together, you should find it. I think it’s still a very good introduction to the stories of the men who were held and the lies that were told about them.

And I have, ever since that time, been writing about them, generally online. I’ve built up this huge website of articles covering the men’s stories, continually trying to make people remember that these are human beings — they’re not just “the worst of the worst” who we don’t need to know who they are — but also to expose the lies that have been told about them and to expose what’s wrong about the way people are held at Guantánamo. And that’s because if you’re going to deprive somebody of their liberty, you either charge them with a crime — arrest them, charge them with a crime, give them a trial — or you take them off the battlefield in accordance with the Geneva Conventions and hold them unmolested until the end of hostilities. And that wasn’t what happened at Guantánamo.