Andy Worthington's Blog, page 118

April 14, 2014

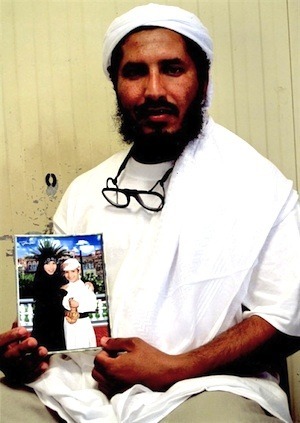

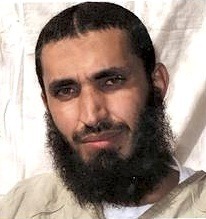

Gravely Ill, Shaker Aamer Asks US Judge to Order His Release from Guantánamo

I wrote the following article for the “Close Guantánamo” website, which I established in January 2012 with US attorney Tom Wilner. Please join us — just an email address is required to be counted amongst those opposed to the ongoing existence of Guantánamo, and to receive updates of our activities by email. Please also sign and share the international petition calling for Shaker Aamer’s release.

I wrote the following article for the “Close Guantánamo” website, which I established in January 2012 with US attorney Tom Wilner. Please join us — just an email address is required to be counted amongst those opposed to the ongoing existence of Guantánamo, and to receive updates of our activities by email. Please also sign and share the international petition calling for Shaker Aamer’s release.

Last Monday, lawyers for Shaker Aamer, 45, the last British resident in the US prison at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, asked a federal judge to order his release because he is chronically ill. A detailed analysis of Mr. Aamer’s mental and physical ailments was prepared by an independent psychiatrist, Dr. Emily A. Keram, following a request in October, by Mr. Aamer’s lawyers, for him to receive an independent medical evaluation.

The very fact that the authorities allowed an independent expert to visit Guantánamo to assess Mr. Aamer confirms that he is severely ill, as prisoners are not generally allowed to be seen by external health experts unless they are facing trials. Mr. Aamer, in contrast, is one of 75 of the remaining 154 prisoners who were cleared for release from Guantánamo over four years ago by a high-level, inter-agency task force established by President Obama shortly after he took office in 2009.

As a result, the authorities’ decision to allow an independent expert to assess Mr. Aamer can be seen clearly for what it is — an acute sensitivity on their part to the prospect of prisoners dying, even though, for many of the men, being held for year after year without justice is a fate more cruel than death, as last year’s prison-wide hunger strike showed.

In her submission, based on 25 hours meeting with Mr. Aamer from December 16-20, Dr. Keram, an independent psychiatrist who has previously examined other prisoners facing military commission trials, reported and analyzed what Mr. Aamer had told her about his initial detention by the Northern Alliance in Afghanistan in late 2001, his initial imprisonment by the US — at Bagram and Kandahar in Afghanistan — and his 12 years at Guantánamo, and her conclusions are that he has Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and “additional psychiatric symptoms related to his current confinement that are not included in the diagnostic criteria for PTSD but which also gravely diminish his mental health.”

The detailed list of his mental ailments is alarming, but Dr. Keram also provided an additional psychiatric prognosis, noting that, “In addition to the psychiatric symptoms discussed above, Mr. Aamer has suffered a profound disruption of his life, dignity, and personhood.”

She added: “The length, uncertainly, and stress of Mr. Aamer’s confinement has caused significant disruptions in his underlying sense of self and ability to function. He is profoundly aware of what he has lost. He discussed the struggle he faces if his detention were to continue indefinitely. Additionally, we discussed the struggle he will face, were he to be released, in regaining the ability to function in his family and society. He is aware that it has taken some of the former detainees years to begin to recover to the extent that they have some degree of meaning and productivity in their lives.”

That reference to “the length, uncertainty, and stress” of Mr. Aamer’s imprisonment reminded me of what Christophe Girod, an official with the International Red Cross, said back in October 2003, when the prison had been open less than two years. Girod said, “The open-endedness of the situation and its impact on the mental health of the population has become a major problem,” and it is disturbing to realize how those factors can only have been hideously exacerbated with the passage of 12 years — not just for Shaker Aamer, but for many, if not most or all of the 154 other remaining prisoners.

In her analysis, Dr. Keram continued: “The chronic and severe psychiatric symptoms described above have gravely diminished Mr. Aamer’s mental health. In order to maximize his prognosis, Mr. Aamer requires psychiatric treatment, as well as reintegration into his family and society and minimization [of] his re-exposure to trauma and reminders of trauma.”

Dr. Keram recommended that Mr. Aamer “should receive psychiatric treatment in England in order to obtain meaningful therapeutic benefit,” and also stressed that returning him to Saudi Arabia, the country of his birth — where the US has expressed an interest in returning him, even though he has a British wife and four British children, and was given indefinite leave to remain in the UK prior to his capture — would be disastrous.

As she explained: “The severity of Mr. Aamer’s psychiatric symptoms would worsen were he to be involuntarily repatriated to Saudi Arabia. He reported that should this occur he would not be reunited with his family for many years, if ever. His ongoing separation from his family significantly exacerbates his psychiatric symptoms. Additionally, the impact of a move to Saudi Arabia on his family would likely re-traumatize Mr. Aamer, as his wife and children are unaccustomed to Saudi culture. Finally, Mr. Aamer’s probable further confinement in the Saudi rehabilitation program would likely be re-traumatizing, as its goal would be to re-acclimate him to the norms of Saudi society. Mr. Aamer identifies as a British Muslim and is most comfortable in that culture.”

Dr. Keram also analysed Mr. Aamer’s extensive physical ailments, which include severe edema (swelling caused by fluid retention in the body’s tissues, and also known as dropsy), severe migraines, asthma, chronic urinary retention, otitis media (middle ear infection), tinnitus, GERD (gastroesophageal reflux disease, or acid reflux disease) and constipation.

In reporting the motion filed on behalf of Mr. Aamer, the New York Times helpfully explained that it represented “a new tactic by lawyers seeking the release of Guantánamo detainees by building on a court’s decision last year that a Sudanese detainee should be allowed to leave because of health problems.” The Times continued, “Both the Sudanese case and now Mr. Aamer’s focus on laws and regulations governing the repatriation of prisoners of war that could become increasingly important as the detainee population at Guantánamo ages.”

The New York Times added: “The law of war permits detaining enemy fighters without trial to prevent their return to the battlefield. But it requires repatriating those who are seriously wounded or sick even before an armed conflict is over. A Geneva Conventions article says detainees shall be repatriated if their ‘mental or physical fitness seems to have been gravely diminished’ and they seem unlikely to recover within a year.

The Times continued: “A United States Army regulation says wartime detainees who are ‘eligible’ for repatriation include sick or wounded prisoners ‘whose conditions have become chronic to the extent that prognosis appears to preclude recovery in spite of treatment within one year from inception of disease or date of injury.”

In the motion submitted last Monday, Mr. Aamer’s lawyers argued that he “should be released immediately because his illness has become so chronic that recovery, even with optimal circumstances and care, is precluded within one year, and is likely to take many years or the full course of his remaining natural life.”

The New York Times noted that Mr. Aamer’s condition “appears less severe” than that of the Sudanese prisoner, Ibrahim Idris, who was freed in December after the Justice Department refused, for the first time, to challenge a prisoner’s habeas corpus petition (Mr. Idris’s, in October). Mr. Idris’s lawyers had described him as morbidly obese and schizophrenic, and had argued that his “long-term severe mental illness and physical illnesses make it virtually impossible for him to engage in hostilities were he to be released.”

However, Ramzi Kassem, a law professor at the City University of New York, whose legal clinic represents Mr. Aamer, refuted the Times‘s claim about the gravity of Mr. Aamer’s illness compared to that of Ibrahim Idris. “The law does not require a prisoner’s total and permanent incapacitation,” he said in an interview, adding, “The grave illnesses with which Shaker has now been diagnosed, taken together or separately, meet the legal standard for release under international and domestic law.”

I thoroughly endorse Ramzi Kassem’s analysis, and fervently hope that the judge in his case in the District Court in Washington D.C. — Judge Rosemary Collyer — agrees.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

April 5, 2014

Please Read “Guantánamo Forever,” My Latest Article for Al-Jazeera English

I hope you have time to read my latest article for Al-Jazeera, “Guantánamo Forever,” and to like, share and tweet it if you find it useful. It covers the Periodic Review Boards (PRBs) at Guantánamo, convened to assess whether 46 prisoners designated for indefinite detention without charge or trial by the inter-agency task force that President Obama established after taking office in 2009, or 25 others designated for prosecution by the task force, should continue to be held without charge or trial, or whether they should be recommended for release — even if, ironically, that only means that they get to join the list of 76 other cleared prisoners who are still held. The review boards began in November, and have, to date, reviewed just three of the 71 cases they were set up to review. The fourth, reviewing the case of Ghaleb Al-Bihani, takes place on April 8.

The number of prisoners cleared for release (76) includes the first prisoner to have his case reviewed by a Periodic Review Board, which recommended his release in January, although my Al-Jazeera article is my response to the most recent activity by the review boards — the decision taken on March 5 to continue holding, without charge or trial, a Yemeni prisoner, Abdel Malik al-Rahabi, who has been at Guantánamo for over 12 years, and the review of Ali Ahmad al-Razihi, the third prisoner to have his ongoing detention reviewed, which took place at the end of March.

In the article I explain that the decision to continue holding Abdel Malik al-Rahabi, taken by representatives of the Departments of State, Defense, Justice and Homeland Security, as well as the office of the Director of National Intelligence and the Office of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, is a disgrace.

The most important reason why the decision is a disgrace is because the information analyzed by the board members is, as I explain in the article, profoundly unreliable, consisting primarily of statements made by prisoners who were subjected to torture in CIA “black sites” — or, in one notorious case, to a specifically tailored torture program in Guantánamo itself — and, in one other case, by a prisoner, now released, who, while regarded by some officials as an important informant, was better known as the most prolifically unreliable witness at Guantánamo, whose unreliability had been noted by other officials. These officials had warned against relying on any information he provided, and his unreliability had subsequently been cited by judges reviewing prisoners’ habeas corpus petitions.

Please read the article to find out more about these unreliable witnesses, as it is deeply troubling that the representatives of the US government departments who are reviewing the cases of these men show no sign of recognizing the profound unreliability of the supposed evidence — something that, for the most part, the mainstream media has also shown little interest in analyzing, even though the failure to do so helps to maintain the illusion that there is something resembling justice at Guantánamo, when there is not.

Note: Please also see my previous article for Al-Jazeera about the Periodic Review Boards, entitled, “Guantánamo’s secretive review boards,” and also see my other recent articles about the review boards, “Indefinitely Detained Guantánamo Prisoner Asks Review Board to Recommend His Release” and “Guantánamo, Where Unsubstantiated Suspicion of Terrorism Ensures Indefinite Detention, Even After 12 Years.”

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

March 29, 2014

The Chaotic History of Guantánamo’s Military Commissions

See the full list here of everyone charged in the military commissions at Guantánamo.

Recently, a friend asked me for information about all the Guantánamo prisoners who have been put forward for military commission trials at Guantánamo, and after undertaking a search online, I realized that I couldn’t find a single place listing all the prisoners who have been charged in the three versions of the commissions that have existed since 2001, or the total number of men charged.

As a result, I decided that it would be useful to do some research and to provide a list of all the men charged — a total of 30, it transpires — as well as providing some updates about the commissions, which I have been covering since 2006, but have not reported on since October. The full list of everyone charged in the military commissions is here, which I’ll be updating on a regular basis, and please read on for a brief history of the commissions and for my analysis of what has taken place in the last few months.

The commissions were dragged out of the history books by Dick Cheney on November 13, 2001, when a Military Order authorizing the creation of the commissions was stealthily issued with almost no oversight, as I explained in an article in June 2007, while the Washington Post was publishing a major series on Cheney by Barton Gellman (the author of Angler, a subsequent book about Cheney) and Jo Becker. Alarmingly, as I explained in that article, the order “stripped foreign terror suspects of access to any courts, authorized their indefinite imprisonment without charge, and also authorized the creation of ‘Military Commissions,’ before which they could be tried using secret evidence,” including evidence derived through the use of torture.

Cheney’s military commissions, which involved various chaotic pre-trial hearings but no trials, lasted until June 28, 2006, when, in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld, a challenge brought by one of the ten men charged (Salim Hamdan, a Yemeni who had taken a paid job as one of Osama bin Laden’s drivers), the Supreme Court ruled that the commissions lacked “the power to proceed because its structures and procedures violate both the Uniform Code of Military Justice and the four Geneva Conventions signed in 1949.”

Almost immediately, however, the Bush administration responded by negotiating with Congress for a new version of the commissions to be launched, and the result was the Military Commissions Act of 2006. Between February 2007 and December 2008, 27 prisoners were charged in the military commissions (including nine of the ten men previously charged), although only three cases went to trial — David Hicks in March 2007, Salim Hamdan in July 2008, and Ali Hamza al-Bahlul in October 2008. For a brief rundown of most of these stories, see my article from November 2008, “20 Reasons To Shut Down The Guantánamo Trials.”

When President Obama took office in January 2009, he initially suspended the commissions, but in a speech in May 2009 he announced that they were back on the table. He then worked with Congress to revive them, and the result was the Military Commissions Act of 2009. According to an announcement by Attorney General Eric Holder in November 2009, there were supposed to be two types of trials under the Obama administration — in federal court, for the five men accused of involvement in the 9/11 attacks, as well as in the military commissions. However, when the administration faced criticism for planning to hold the 9/11 trial in New York, President Obama dropped the plans, and Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and his four co-defendants (all accused of involvement the 9/11 attacks) were once more charged in the military commissions.

Nor were the military commissions free of problems. Senior Obama administration officials had told Congress (see here and here) that certain charges designated as war crimes in the MCA of 2006, and intended for the 2009 version — providing material support for terrorism, and, possibly, conspiracy — were not regarded as war crimes, and would probably be overturned on appeal. Congress failed to take the advice on board, but this was indeed what happened in October 2012, in another victory for Salim Hamdan, when his conviction was overturned, and in January 2013 the conviction of Ali Hamza al-Bahlul was also overturned. The government has appealed, but the effect has been for the military to concede that the total number of prisoners who will face trials by military commission (or have already faced trials) out of the 779 men held since the prison opened, is unlikely to exceed 20. In fact, at current estimates, it will be no more than the 15 already charged and/or convicted.

Delays in the 9/11 trial, challenges in the trial of Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri

Since my last article about the commissions (In October 2013), progress has been as painfully slow as usual in the pre-trial stages of the 9/11 trial (for five men including Khalid Sheikh Mohammed), and the trial of Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri (accused of masterminding the attack on the USS Cole in 2000). All six men were held for years in CIA “black sites,” were they were subjected to torture — which, of course, makes a fair and open trial improbable, and has led to a protracted game of cat and mouse as the government tries to suppress all mention of torture, while the defense teams try to expose it.

In December, Ramzi bin al-Shibh, one of the five alleged 9/11 co-conspirators, was ejected twice from the courtroom for interruptions — in the first instance shouting, “This is torture! You have to stop the sleep deprivation and the noises.” This led to questions about his mental competency, but these had not been addressed by January 31 this year, because he refused to talk to a mental health board whose members told the judge that they therefore didn’t know if he was fit to stand trial. As a result, the judge, Army Col. James L. Pohl, was obliged to put off the next round of hearings, scheduled for February, when the only hearings that took place were for al-Nashiri.

The hearings were immediately derailed when al-Nashiri threatened to sack his civilian lawyer, Rick Kammen. Two days later, he apologized, telling Judge Pohl, “I believe we are here in a unique and very strange court,” and complaining that “his lawyers go to secret pretrial hearings and are forbidden to tell him ‘what happened during those closed, classified sessions,’” as the Miami Herald described it.

After this, lawyers sparred over the use of hearsay evidence, held a secret meeting with the judge regarding CIA “black sites,” sought to have the death penalty dismissed in the case of a conviction because of the use of secret evidence which al-Nashiri cannot see, and held another secret meeting with the judge to discuss the use of classified information. At the end of it all, Judge Pohl set a date of December 4 for the trial to begin — although it remains to be seen if that date will hold.

Ahmed al-Darbi’s plea deal

In the last two months, however, the most significant development has been the announcement of a plea deal accepted by Ahmed al-Darbi, a Saudi prisoner, charged in the second and third versions of the commissions, who was seized in Azerbaijan in June 2002 and held in a CIA “black site” in Afghanistan prior to his arrival at Guantánamo. A declaration by al-Darbi about his torture is here.

As the New York Times reported, On February 20, al-Darbi pleaded guilty before a military commission to charges relating to his involvement in an Al-Qaeda attack in 2002 on a French oil tanker, the MV Limburg, off the coast of Yemen, when one crew member died. According to the plea deal, he “will spend at least three and a half more years at Guantánamo before he is sentenced,” and will then probably be transferred to Saudi Arabia to serve out the remainder of a sentence that is expected to be between nine to 15 years, “depending on his behavior in custody,” as the New York Times described it.

In exchange for this sentence (which, with the 12 years he has already spent in custody, will amount to between 21 and 27 years in custody in total), al-Darbi has agreed to cooperate with prosecutors, and is expected to testify against Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri, who is currently facing pre-trial hearings, and is accused of masterminding another attack on a ship, in this case the USS Cole, which was attacked in 2000, with the loss of 17 US lives.

“In a twist,” as the New York Times described it, al-Darbi “was already at Guantánamo by the time the MV Limburg was attacked.” The judge, Air Force Col. Mark Allred, acknowledged that, but said it made no difference. “Obviously you were not there, you were somewhere else,” he said. “But the actual perpetrators were there, and you are liable for their actions as a principal.”

The New York Times also noted that, in accepting a plea deal, al-Darbi had “traded away an opportunity to argue that a French vessel in Yemen in 2002 was beyond the scope of the American armed conflict with Al-Qaeda, and that if so, he could be prosecuted only in a civilian criminal trial, not an American military tribunal.” This could have been a significant challenge — and is one being undertaken by Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri — but it is, I believe, understandable that al-Darbi chose a plea deal instead, as it has proven to be the most reliable way of leaving Guantánamo, in marked contrast to the ongoing plight of the 75 men approved for release by an an inter-agency task force over four years ago, but still held, or the 69 others not scheduled to face trials, who are awaiting review boards to tell them if they too should be approved for release.

The contentious addition of conspiracy to the charges against Abd al-Hadi al-Iraqi

The week before Ahmed al-Darbi’s plea deal, the only other significant development of late was an announcement about the most recent prisoner to be charged, Abd al-Hadi al-Iraqi, who was brought to Guantánamo from an unidentified CIA facility in April 2007, and is regarded as a “high-value detainee.”

The week before Ahmed al-Darbi’s plea deal, the only other significant development of late was an announcement about the most recent prisoner to be charged, Abd al-Hadi al-Iraqi, who was brought to Guantánamo from an unidentified CIA facility in April 2007, and is regarded as a “high-value detainee.”

Al-Iraqi is one of only six prisoners brought to Guantánamo since 14 “high-value detainees” (including the five 9/11 co-defendants and Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri) were brought to the prison from the CIA’s “black site” in September 2006. An alleged high-level link between Al-Qaeda and insurgents in Iraq, he was charged last June, but on February 3 prosecutors added a charge of conspiracy to the existing charges.

This was a contentious move because, when the D.C. Circuit Court overturned the conviction against Ali Hamza al-Bahlul in January 2013, the judges specifically overturned not only the charge of providing material support for terrorism, but also conspiracy, “on the grounds that the charge was not recognized under the international laws of war,” as the New York Times explained.

The Times added, “The Obama administration has appealed, but if the ruling stands, it sharply undermines the utility of tribunals — as opposed to civilian courts — to sentence people to prison who participated in terrorist groups but are not personally linked to any specific attack.”

To my mind, it seems premature — or perhaps arrogant — of prosecutors to file a conspiracy charge when it has been struck down by the D.C. Circuit Court (which does not have a reputation as a liberal court). In addition, al-Iraqi will no doubt want to challenge whether the commissions are able to try conduct that took place before the passage of the Military Commissions Act in 2006.

Given al-Bahlul’s successful appeal, striking down conspiracy in his case, I can only wonder if, because al-Iraqi didn’t arrive at Guantánamo until April 2007, prosecutors hope to charge him with crimes that took place between the passage of the 2006 MCA and his capture, although that seems like a small window of opportunity, as well as being unreliable, as conspiracy remains a dubious charge in a war crimes forum.

The irony, of course, is that last week Sulaiman Abu Ghaith, a Kuwaiti who briefly acted as a spokesman for Al-Qaeda immediately after the 9/11 attacks, and was then held under a form of house arrest for 10 years by the Iranian government, was found guilty in a federal court in New York on charges that include conspiracy, for which he may well receive a life sentence. As a result, anyone paying close attention and seeking severe punishment for those who were allegedly involved with Al-Qaeda would, it seems to me, be better off pushing for the commissions to be scrapped — again — and for those who can genuinely be accused of crimes to be tried in federal courts on the US mainland instead.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

March 25, 2014

The UK’s Unacceptable Obsession with Stripping British Citizens of Their UK Nationality

In January, Theresa May, the British Home Secretary, secured cross-party support for an alarming last-minute addition to the current Immigration Bill, allowing her to strip foreign-born British citizens of their citizenship, even if it leaves them stateless.

In January, Theresa May, the British Home Secretary, secured cross-party support for an alarming last-minute addition to the current Immigration Bill, allowing her to strip foreign-born British citizens of their citizenship, even if it leaves them stateless.

The timing appeared profoundly cynical. May already has the power to strip dual nationals of their citizenship, as a result of legislation passed in 2002 “enabling the Home Secretary to remove the citizenship of any dual nationals who [have] done something ‘seriously prejudicial’ to the UK,” as the Bureau of Investigative Journalism described it in February 2013, but “the power had rarely been used before the current government.”

In December, the Bureau, which has undertaken admirable investigation into the Tory-led mission to strip people of their citizenship, further clarified the situation, pointing out that the existing powers are part of the British Nationality Act, and allow the Home Secretary to “terminate the British citizenship of dual-nationality individuals if she believes their presence in the UK is ‘not conducive to the public good’, or if they have obtained their citizenship through fraud.” The Bureau added, “Deprivation of citizenship orders can be made with no judicial approval in advance, and take immediate effect — the only route for people to argue their case is through legal appeals. In all but two known cases, the orders have been issued while the individual is overseas, leaving them stranded abroad during legal appeals that can take years” — and also, of course, raising serious questions about who is supposedly responsible for them when their British citizenship is removed.

The Bureau has established that 41 individuals have been stripped of their British nationality since 2002, and that 37 of these cases have taken place under Theresa May, since the Tory-led coalition government was formed in May 2010, with 27 of these cases being on the grounds that their presence in the UK is “not conducive to the public good.” In December, the Bureau confirmed that, in 2013, Theresa May “removed the citizenship of 20 individuals — more than in every other year of the Coalition government put together.” As the Bureau suggested in February 2013, it appears that, in two cases, the stripping of UK citizenship led to the men in question subsequently being killed by US drone attacks.

The two men, Bilal al-Berjawi, a British-Lebanese citizen who grew up in London, and Mohamed Sakr, a British-Egyptian citizen who was born in the UK, travelled to Somalia in 2009, where they allegedly became involved with the militant group al-Shabaab. Theresa May stripped both men of their British nationalities in 2010, and, as the Bureau described it:

In June 2011 Mr. Berjawi was wounded in the first known US drone strike in Somalia and [in 2012] was killed by a drone strike – within hours of calling his wife in London to congratulate her on the birth of their first son. His family have claimed that US forces were able to pinpoint his location by monitoring the call he made to his wife in the UK. Mr. Sakr, too, was killed in a US airstrike in February 2012 … Mr. Sakr’s former UK solicitor said there appeared to be a link between the Home Secretary removing citizenships and subsequent US actions. “It appears that the process of deprivation of citizenship made it easier for the US to then designate Mr. Sakr as an enemy combatant, to whom the UK owes no responsibility whatsoever,” Saghir Hussain said.

Ian Macdonald QC, the president of the Immigration Law Practitioners’ Association, who has long opposed the disturbing trend towards secrecy and unaccountability in Britain’s post-9/11 anti-terror laws, added that depriving people of their citizenship “means that the British government can completely wash their hands if the security services give information to the Americans who use their drones to track someone and kill them.” He also described the citizenship orders as “sinister,” and said of the government, “They’re using executive powers and I think they’re using them quite wrongly. It’s not open government; it’s closed, and it needs to be exposed.”

Another case exposed by the Bureau involves a man stranded in Pakistan, who says he is under threat from the Taliban and unable to find work to support his wife and three children His story was published on March 17, entitled, “‘My British citizenship was everything to me. Now I am nobody’ — A former British citizen speaks out.”

In another case, as Helena Kennedy QC noted in an article for the Bureau on March 20, another dual nationality UK citizen, Mahdi Hashi, “was picked up by Djibouti’s secret police, whom he told he was British. After calls, the agents told him the British authorities said he was no longer a British citizen. He had no other passport and was therefore rendered stateless. This meant he had no access to consular advice as to his rights; no representations were made that he should be brought before a court. As a result he was interrogated at length with no legal protection, handed over to American agents, further interrogated and then hooded and flown to the US without any extradition proceedings.” For more on Mahdi Hashi’s case, see this article in the Nation by Aviva Stahl, and you can listen to Aviva Stahl, in a recent radio interview with Rania Khalek and Kevin Gosztola here.

In December, a former senior Foreign Office official told the Bureau that “the steep rise in cases is at least partly due to the large number of British nationals travelling to Syria to participate in the civil war there,” as the Bureau described it. The former official said, “This [deprivation of citizenship] is happening. There are somewhere between 40 and 240 Brits in Syria and we are probably not quick as we should be to strip their citizenship.” The former official also “described the practice of revoking the citizenship of British nationals fighting in Syria as ‘an open secret’ in Foreign Office circles.”

In January, May presented her addition to the bill as, in the Guardian‘s words, “a last-ditch bid to reduce a damaging Tory rebellion in the Commons” after the Tory MP Dominic Raab had tabled an amendment seeking to change the law so that, as the BBC put it, “foreign criminals can no longer use Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights — a right to a family life — to escape deportation.”

May correctly told MPs that Raab’s amendment was “incompatible” with the European Convention on Human Rights, but the timing of the decision to add the citizen-stripping clause — Clause 60 — to the bill instead, which, disturbingly, passed by 297 votes to 34, was deeply suspicious. As the Bureau of Investigative Journalism noted earlier this month, May had announced her plans via the Times on November 12, 2013, in response to a ruling by the UK Supreme Court that “the Home Office had illegally revoked the UK citizenship of an Iraqi-born man, Hilal al-Jedda, because he held no other nationality.” (May subsequently issued another stripping al-Jedda’s citizenship for a second time).

The Bureau also noted on December 23 that May had already “held at least one confidential meeting with Coalition MPs to discuss the plans, including inserting an amendment into the Immigration Bill allowing her to remove the nationality of those who have acquired British citizenship, even if it will make them stateless, if they have done something ‘seriously prejudicial to the vital interests’ of the UK.”

In response to Theresa May’s dreadful innovations, Helena Kennedy QC wrote an article for the Bureau, in which she condemned the government for its disdain for the law following the Supreme Court’s Hilal al-Jedda ruling. She wrote, “The Government does not take well to judgments saying it has done something contrary to law,” and also pointed out:

The proposal to allow the Home Secretary to deprive a naturalised citizen of his or her citizenship not only risks damaging the UK’s international relations but also risks breaching a whole swathe of international obligations. The reason the government gives is that they want to prevent terrorism, but deprivation of citizenship is not a viable alternative to the responsible prosecution of alleged criminal conduct.

Citizenship is not a privilege; it is a protected legal status. The US, Germany and many other states would not dream of removing citizenship under any circumstances. The answer to conduct we deem criminal is to prosecute it.

Deprivation with all its consequences in the modern world is equivalent to a penal sanction of the most serious kind – but imposed without a criminal trial, without conviction, without close and open examination of the evidence and without the opportunity to defend yourself. All of this is contrary to due process — a fundamental human right.

Kennedy’s comment were in marked contrast to the position taken by the Home Office in December, when approached by the Bureau. On that occasion, the Home Office declined to comment on the reasons for the rise in deprivation of citizenship orders but said, “Citizenship is a privilege, not a right, and the Home Secretary will remove British citizenship from individuals where she feels it is conducive to the public good to do so.”

Helena Kennedy is correct, of course, but sadly most MPs failed to recognise the importance of proper legal safeguards for all citizens, and, last week, although there was a heated debate, the House of Lords failed to remove Clause 60 from the legislation, despite criticism by lawyers, by some MPs and by the Joint Committee on Human Rights, which issued a report on February 26 that, as the Bureau put it, “questioned the timing of Theresa May’s amendment on statelessness and said that the new power ran a ‘very great risk of breaching the UK’s obligations’ to other nations if Britons were to be made stateless while overseas.”

The clause passed despite the legal action charity Reprieve pointing out that the measures would “leave an estimated 3.4 million British citizens vulnerable to being arbitrarily made stateless in England and Wales alone, according to figures from the 2011 census,” and noting that, in 1958, the US Supreme Court denounced the stripping of citizenship as “a form of punishment more primitive than torture.”

As Reprieve described it, “Such a measure was held by the United States Supreme Court in the 1950s to constitute cruel and unusual punishment, and that the ‘use of denationalization as a punishment [means] the total destruction of the individual’s status in organized society. It is a form of punishment more primitive than torture, for it destroys for the individual the political existence that was centuries in the development…In short, [s/he] has lost the right to have rights.’”

As Helena Kennedy also explained, “Deprivation of citizenship is another way of avoiding the old-fashioned process of putting people on trial if they are suspected of doing wrong. It is a way of short-cutting the rule of law. Hannah Arendt said that statelessness deprives people of ‘the right to have rights’. It is a policy that has been used by the worst tyrannical regimes. It was why so many people wandered the world stateless after the Second World War and why in 1961 the UK with other nations signed up to the UN Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness. This intended change in the law will be a source of shame to us in the years to come. It must be opposed by us all.”

I will be posting a transcript of the House of Lords debate very soon, but the only hope now, legislatively, is that many of the Lords’ concerns will be “discussed at a meeting ahead of report stage,” as Alice Ross of the Bureau explained in an article compiling her live tweets of the debate. I hope at that point there will be further publicity, and further opportunities for this dreadful development to be challenged and, eventually, overturned.

Note: For further information on Clause 60, see Liberty’s briefing here.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

March 23, 2014

Sulaiman Abu Ghaith’s Unexpected Testimony in New York Terrorism Trial

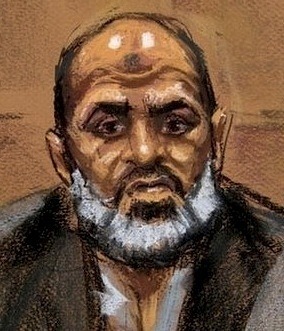

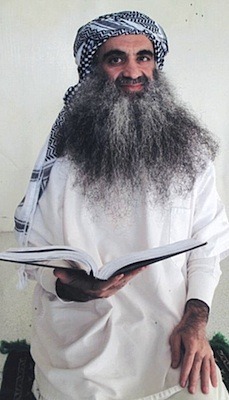

On Wednesday, Sulaiman Abu Ghaith (also identified as Sulaiman Abu Ghayth), the Kuwaiti cleric who is on trial in New York accused of terrorism, surprised the court by taking to the witness stand to defend himself.

On Wednesday, Sulaiman Abu Ghaith (also identified as Sulaiman Abu Ghayth), the Kuwaiti cleric who is on trial in New York accused of terrorism, surprised the court by taking to the witness stand to defend himself.

Abu Ghaith, 48, who was held for over ten years under a form of house arrest in Iran before being freed in Turkey, and, via Jordan, ending up in US custody last year, appeared in broadcasts from Afghanistan immediately after the 9/11 attacks as a spokesman for Al-Qaeda.

He is charged with conspiracy to kill United States nationals, conspiracy to provide material support and resources to terrorists, and providing material support and resources to terrorists — charges that include the claim that he had knowledge of Al-Qaeda’s operations, including plots involving shoe bombs (for which a British man, Richard Reid, was arrested, tried and convicted in 2002). As the New York Times described it, the government “said in court papers that as part of his role in the conspiracy and the support he provided to Al Qaeda, Mr. Abu Ghaith spoke on behalf of the terrorist group, ‘embraced its war against America,’ and sought to recruit others to join in that conspiracy.”

Abu Ghaith denies any knowledge of Al-Qaeda’s operations, and on Wednesday, just before the defence rested its case, he “offered an extraordinarily intimate look at [Osama] Bin Laden at the time [of the 9/11 attacks], taking jurors inside his cave in Afghanistan,” as the New York Times put it.

In his testimony, in which he was questioned by his lawyer, Stanley Cohen, Abu Ghaith explained how he had traveled to Afghanistan in June 2001 because of what he described as “a serious desire to get to know the new Islamic government in Afghanistan” — in other words, the Taliban — and described how he was invited to meet bin Laden in Kandahar. At a second meeting, he said, bin Laden “said in your capacity as a sheikh, an imam, and a teacher, we want you to give some lectures and speeches. And to teach at a religious school … that we have.”

Abu Ghaith described the school, in Kandahar, as the Religious Institute (although it was generally known as the Institute of Islamic Studies), whose director was Abu Hafs al-Mauritani, a spiritual advisor to Al-Qaeda, who fell out with bin Laden over the 9/11 attacks, which he opposed.

Abu Ghaith didn’t speak or teach at the school, but, at bin Laden’s request, he did speak at two training camps, and, in response to questioning by Cohen about how bin Laden described the camps, he said, “It was a preparation camp, because as we know in sharia, in the Islamic law, everybody needs to be prepared. Like in any nation need to prepare themselves to be ready.”

Abu Ghaith then returned to Kuwait briefly to collect his wife and his seven children and bring them back to Kandahar, where Abu Hafs found him opportunities to speak at a mosque and where he also met bin Laden again. After some time, however, he became worried that the healthcare facilities were insufficient in Afghanistan for his wife, who was pregnant, and so he arranged for her and the children to leave for Pakistan, and then to return to Kuwait.

Abu Ghaith arrived back in Afghanistan (presumably from Pakistan) on September 7, 2001, just four days before the 9/11 attacks. Cohen asked him about his role at this time:

Q. By the way, from the first time you met Usama Bin Laden through September 8, had he asked you to be a spokesperson for Al Qaeda?

A. No.

Q. Did anyone ask you to be a spokesperson for Al Qaeda during that time?

A. No.

Q. Did you volunteer to be a spokesperson for Al Qaeda?

A. When I spoke that title or that position was not there.

Questioned about 9/11, Abu Ghaith explained that he was in Kabul on the day, at the house of a friend called Adil, and that he learned about the attacks “[f]rom the media, from the TV.” Cohen asked him, “Prior to 9/11 did you have any idea that that attack was going to occur?” and he replied, “No. Specifically, no, I didn’t have any idea” — although he later conceded, under cross-examination, that he had heard, in the training camps, that “something” might happen. Michael Ferrara, a prosecutor, asked him, “You knew something big was coming from Al-Qaeda?” and he replied, “Yes.”

Questioned by Stanley Cohen, Abu Ghaith said that, on the evening of September 11, 2001, Osama bin Laden sent someone to ask him to meet with him. They traveled by car, for two or three hours, into the mountains. Cohen asked him, “Why did you go see Usama Bin Laden after you heard about 9/11?” and he replied, “I went to see him. I didn’t — I didn’t know the subject which he wanted to see me for, so I went as, as usual. Whenever he asked to see me, I went.” He added that he had met bin Laden six or seven times before 9/11.

Asked to describe what happened when he met bin Laden on this occasion, Abu Ghaith said:

I arrived to that area at night, I believe. I found Usama Bin Laden with another group, a guard, security guard, the number of which was about 20 to 25 people. I found him in a cave inside a mountain in a rough terrain, rough mountain terrain with some villages, some small villages and some bedouins who lived there. Naturally, I greeted him.

He said, Come in, sit down.

He said, Did you learn about what happened?

I said, What do you mean?

He said, The attacks on the United States.

I said, Yes.

He said, We are the ones who did it. What do you expect to happen?

I said, Why are you asking me this question? I don’t know anything about these events.

He said, Well, since you saw, you learned about that huge event, what do you expect to happen?

I said, I am not a military analyst in order to predict.

He said, Well, what’s your take on this as a person in his 30s and have some experience of life?

I said, I don’t have any military expertise to tell you what’s going to happen.

I said, Politically, I said, America, if it was proven that you were the one who did this, will not settle until it accomplishes two things: To kill you and topple the state of Taliban.

He said, You are being too pessimistic.

I said, You asked my opinion, and this is my opinion.

The day after, Abu Ghaith said that, after breakfast, he saw bin Laden having a meeting in a cave with Ayman al-Zawahiri, Al-Qaeda’s second-in-command, and Abu Hafs al-Masri (aka Mohammed Atef), Al-Qaeda’s military chief, who was killed in November 2001. “I was not invited to join that meeting,” he said, adding, “I was outside. They sat about half an hour talking. Then he [bin Laden] asked, he called me in.” He continued:

And he said to me: Now, after these events, it’s no secret or it’s not hard it’s a no-brainer to predict what is going to happen. What you expected may actually happen. And I want to deliver a message to the world. And Dr. Ayman also wants to deliver a message. I want you to deliver that message or to address the world.

I said, Well, I am new in this field. I don’t have any experience or any knowledge about the subject. I don’t have any ability to form ideas around that subject.

He said, I am going to give you some points and you build around them that speech.

I said, If you would kindly spare me that mission, it will be better.

He said, No, I insist that you speak. This is your job. You are an imam, you are a speaker, and you will only discuss the religious aspect, which you are familiar with.

I don’t want to hide that I had some convictions that the nature of any conflict, whenever there is an oppression or injustice inflicted on someone that there could be possible reactions. Those reactions could be unpredictable.

Under some of these convictions, I accepted to speak.

Around two hours later, in front of the cave, Abu Ghaith made the speech that was recorded and issued on video. In court, this exchange took place with his lawyer:

Q. Did anyone give you a statement to read as part of that video or any words to use in that video?

A. Other than the bullet points that Usama Bin Laden had given me to build the speech around, no.

Q. When you say bullet points, what do you mean, sir?

A. The points around which I built the speech. He said mention some of the Koranic verses and some hadith, that justify why those attacks happened, the nature of the conflict. These were the points around which I built that speech.

Afterwards, Abu Ghaith said that he spent two to three weeks staying with bin Laden and his entourage, because “the situation at that time after [9/11], the events were very tense and the roadways were extremely dangerous. I did not have any personal means of transportation to move, so I was forced to stay with him with the rest of the group.”

He was also asked about subsequent videos that were made, including one in which he spoke of a “storm of aeroplanes,” and in response to questioning from Cohen, he confirmed that the phrase came from bin Laden, and added, “All the videos which I filmed were the thoughts and the points made by Sheikh Usama” — a point that I thought was particular telling.

After his time with bin Laden, Abu Ghaith said they all went to Kabul, but then split up, and he stayed somewhere he had stayed previously, although he met with bin Laden again and made three more videos. Then, after no more than a week, he said that the situation in Kabul became insecure, and, like many other people, he then went to Jalalabad, and was eventually smuggled into Pakistan on a 16-hour route through the mountains. There, he said, he briefly met Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, who he had also met once in Afghanistan, although the meeting only involved “[c]asual talk.”

In connection with the videos Abu Ghaith was involved in making, the following exchange with Cohen also took place:

Q. By the way, when you made these videos, was it your intent to recruit anyone?

A. There’s no one who was capable of recruiting anyone except Usama Bin Laden. My intention was not to recruit anyone.

Q. What specifically was your intention?

A. My intention was to deliver a message, a message that I believed that oppression, if it befalls any nation, any people, any category of people, that category must revolt at some point. People do not accept oppression. They cannot take it. And what happened was a result, as I understand, a natural result for the oppression that befell Muslims. I wanted to proclaim the message that Muslims had to bear responsibility and defend themselves.

Abu Ghaith also responded to questioning about shoe bombs, stating that he had not heard about any plots, and had not heard about or met Richard Reid.

In further questioning, Abu Ghaith explained that, after his arrival in Pakistan, he was then taken to Karachi, and on to Iran, where he was at liberty for five months until the Iranian authorities seized him, and placed him under a form of arrest for over ten years.

As the New York Times put it, “Until Mr. Abu Ghaith took the stand, his lawyers had given no indication that they were going to have their client testify.” As I explained in an article last week, Abu Ghaith’s lawyers had submitted to the court written responses to questions that had been given to Khalid Sheikh Mohammed at Guantánamo, and had been hoping to have permission for Mohammed himself to testify from Guantánamo, but the judge, Lewis Kaplan, would not allow his testimony, ruling that the defense had largely failed to establish that Mohammed “has personal knowledge of anything important to this matter.”

The jury is currently deliberating in Sulaiman Abu Ghaith’s case, and I will provide an update when they deliver their verdict. In the meantime, as Daphne Eviatar explained in an article for the Huffington Post, “Although the government claims only that [Abu Ghaith] made a handful of speeches for al Qaeda between May 2001 and 2002, it seeks to hold him responsible for the deaths of all Americans Al Qaeda orchestrated between 1998 and 2013.” She added, “At a conference with the lawyers on Thursday after the defense rested its case, Judge Lewis Kaplan, who’s presided over this trial with a heavy hand since it started earlier this month, confirmed that that’s exactly how he will charge the jury on Monday.”

Although one of Abu Ghaith’s lawyers, Zoe Dolan, had attempted to get the judge to amend the proposed conspiracy charge so that Abu Ghaith couldn’t be held liable for everything Al-Qaeda did over a 15-year period, Judge Kaplan stated that, under US law, even if the jury decides Abu Ghaith only joined the Al Qaeda conspiracy on September 12, “the defendant still will be held responsible for any acts that happened before he joined the conspiracy.”

As Eviatar stated, “Although I’m a lawyer and I’ve studied criminal justice, the breadth of U.S. conspiracy law still astonishes me every time I hear about it. Its effect, in this case, is to make a Kuwaiti preacher who made a handful of speeches for Al Qaeda over a few short months in Afghanistan personally responsible for the deaths of thousands of people killed long before he ever came on the scene. There’s no question that if the jury finds he joined the Al Qaeda conspiracy, he’ll spend the rest of his life in prison.”

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

March 21, 2014

Guantánamo, Where Unsubstantiated Suspicion of Terrorism Ensures Indefinite Detention, Even After 12 Years

Please support my work!

Last week, in a decision that I believe can only be regarded objectively as a travesty of justice, a Periodic Review Board (PRB) at Guantánamo — consisting of representatives of six government departments and intelligence agencies — recommended that a Yemeni prisoner, Abdel Malik al-Rahabi (aka Abd al-Malik al-Rahabi), should continue to be held. The board concluded that his ongoing imprisonment “remains necessary to protect against a continuing significant threat to the security of the United States.”

In contrast, this is how al-Rahabi began his statement to the PRB on January 28:

My family and I deeply thank the board for taking a new look at my case. I feel hope and trust in the system. It’s hard to keep up hope for the future after twelve years. But what you are doing gives me new hope. I also thank my personal representatives and my private counsel, and I thank President Obama. I will summarize my written statement since it has already been submitted to the board.

I have been compliant in the camp facilities and other detainees trust me. I have taken the opportunities for education and personal growth. I have been preparing myself for the life after Guantánamo.

When I return to Yemen, I want to resume my education. My father, who is a tailor, has a job for me in his shop. I have a wife who longs for me and 13-year-old daughter who badly needs me. She’s a light — she is the light of my life.

Being apart from Ayesha has been the hardest part of my detention. In our calls, she says I want you to take me to the park; I want you to help me with my homework. She sends me five or six letters at a time. I will never again leave Ayesha without her father, my wife without her husband, my parents without their son. I want to make up for the twelve years I have been away.

The PRBs were first proposed in March 2011, when President Obama issued an executive order authorizing the ongoing imprisonment without charge or trial of 48 Guantánamo prisoners. These men had been recommended for ongoing imprisonment without charge or trial by the high-level, inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force that President Obama established shortly after taking office in 2009, on the dubious basis that they were too dangerous to release, but that insufficient evidence existed to put them on trial.

Disgracefully, although President Obama promised regular reviews for these men when he issued the executive order, it took over two and a half years for the first PRB to be convened. In the meantime, two of the 48 men had died, but 25 others — originally designated for prosecution by the task force — were added to the PRB list, making 71 men in total.

The first PRB, in October, led to a recommendation that the prisoner in question, Mahmoud al-Mujahid, a Yemeni, should be released — although the irony, of course, is that he merely joined 55 of his compatriots, who were cleared for release by the task force in January 2010, but are still held because of unreasonable fears about the security situation in Yemen.

In al-Rahabi’s case, although the Board “took into consideration [his] strong family support awaiting his return, including housing, employment opportunities, and a wife and daughter ready to support him,” they worried about other alleged problems — described as his “significant ties to al-Qa’ida, including his past role as a bodyguard for Usama Bin Ladin [sic] and a prior relationship with the current amir of al-Qa’ida in the Arabian Peninsula.” The board added, “Further, his experience fighting on the frontlines, possible selection for a hijacking plot, and significant training raise concern for the Board,” and also stated, “The detainee’s planned return to Ibb, assessed to have a marginal security environment, and ties to a relative who is a possible extremist, raises concerns about his susceptibility to reengagement.”

This would indeed be a worry, if any of it was true. Unfortunately, however, it has never been established objectively that there is any truth to the allegations. The most significant claim is that al-Rahabi was a bodyguard for Osama bin Laden, part of a group of men described as the “Dirty 30″ — all alleged bin Laden bodyguards, captured crossing the border from Afghanistan to Pakistan in December 2001.

See if you think this is plausible: al-Rahabi, who was born in 1979, would have been just 22 years old when he was seized. Is it really likely that, having arrived in Afghanistan in the summer of 2000, this young man rose to become a bodyguard for Osama bin Laden in such a short amount of time? In his classified military file, released by WikiLeaks in April 2011, witnesses queued up to accuse him, but all are suspicious — Sanad al-Kazimi, Sharqawi Abdu Ali al-Hajj, Ahmed al-Darbi, Mohammed al-Qahtani, Hassan bin Attash and Mustafa al-Hawsawi (a “high-value detainee”), who were all tortured, and Yasim Basardah, the most notorious liar at Guantánamo.

Moreover, the “high-value detainee” Walid bin Attash claimed that al-Rahabi was “a designated suicide operative,” who, in 1999, “trained for an aborted al-Qaida operation in Southeast Asia to hijack US airliners and crash them into US military facilities in Asia in coordination with 11 September 2001,” for which all the planned operatives swore bayat (an oath of allegiance) to Osama bin Laden. However, there is no evidence that al-Rahabi was in Afghanistan in 1999.

Even more ridiculous is a claim by Ibn al-Shaykh al-Libi (Ali Muhammad Abdul Aziz al-Fakhri), the leader of the independent Khaldan training camp, who was held in a variety of CIA “black sites” before being returned to Libya under Colonel Gaddafi, where he died in prison under suspicious circumstances in 2009. Al-Libi reported that al-Rahabi arrived in Afghanistan in 1995, when he was just 16, staying until 1996.

It may be that these allegations are more trustworthy than my analysis suggests, but I doubt it, as they are typical of prisoners who were tortured, or, in Yasim Basardah’s case, provided false allegations against a shockingly large number of his fellow prisoners to improve his own living conditions at Guantánamo, prior to his release in 2010.

The fact that, over 12 years after his arrival at Guantánamo, al-Rahabi is still being judged as “a continuing significant threat to the security of the United States,” based on information that has never been subjected to any kind of objective scrutiny, is thoroughly unjust, and shows how little regard for the truth the Obama administration and the Periodic Review Board members have — or, to put it another way, how much regard they have for the hugely unreliable collection of lies and hearsay masquerading as evidence in the files on the prisoners put together at Guantánamo.

Al-Rahabi’s case will apparently be considered again in six months, when I hope the board takes a less credulous approach to his perceived dangerousness, but I doubt this will happen, as there seems to be no impetus for the board, or the administration in general, to take a realistic view of the prisoners, rather than one full of distortion, innuendo and outright lies.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

March 19, 2014

Gitmo Clock Marks 300 Days Since Obama’s Promise to Resume Releasing Guantánamo Prisoners; Just 12 Men Freed

Today (March 19, 2014), it is 300 days since President Obama promised to resume releasing prisoners from Guantánamo, in a major speech on national security issues last May, and I’m asking you to promote the Gitmo Clock, which I established last year with the designer Justin Norman, to show how many days it is since the promise, and how many prisoners have been released (just 12). At this rate, it will take over five years for all the cleared prisoners at Guantánamo to be released.

When President Obama made his promise, he was responding to widespread criticism triggered by the prisoners themselves, who, in February, had embarked on a major hunger strike — involving nearly two-thirds of the remaining prisoners — and his promise came after a period of two years and eight months in which just five men had been released from Guantánamo.

What was particularly appalling about the release of prisoners being reduced to a trickle was that over half of the men — 86 of the remaining 166 prisoners at the time — had been approved for release from the prison in January 2010 by the high-level, inter-agency Guantánamo Review Task Force that President Obama established shortly after taking office in 2009 — and some of these men had previously been cleared for release by military review boards under President Bush, primarily in 2006 and 2007.

Congress had raised obstacles designed to prevent the release of prisoners, which had made it difficult for the Obama administration to release prisoners, but President Obama had the power to bypass Congress, through a waiver in the legislation, but had chosen not to use it. In addition, he had himself imposed a moratorium on releasing Yemeni prisoners — who make up two-thirds of the cleared prisoners — after it was revealed that a foiled bomb plot involving a plane on Christmas Day 2009 had been hatched in Yemen.

When he made his promise last May, President Obama also dropped his ban on releasing Yemenis and promised to appoint two envoys to help with the closure of Guantánamo. Those envoys have now been appointed — Cliff Sloan in the State Department and Paul Lewis in the Pentagon — and they have been helping with the release of the 12 prisoners who have left the prison since President Obama made his promise. In addition, in December, Congress eased its restrictions on the release of prisoners.

However, despite the president’s promise there are still 75 prisoners at Guantánamo who were cleared for release by the task force over four years ago, and 55 of these men are Yemenis. If President Obama wants his promise to be taken seriously, he needs to overcome the US establishment’s long-standing reluctance to release cleared Yemenis, because of fears about the security situation in Yemen. As the president said last year, “I think it is critical for us to understand that Guantánamo is not necessary to keep America safe. It is expensive. It is inefficient. It hurts us in terms of our international standing. It lessens cooperation with our allies on counterterrorism efforts. It is a recruitment tool for extremists. It needs to be closed.”

What you can do now

In conclusion, then, please visit, like, share and tweet the Gitmo Clock, and, if you would like to do more, you can:

- Call the White House and ask President Obama to release all the men cleared for release, and to make sure that reviews for the other men are fair and objective. Call 202-456-1111 or 202-456-1414 or submit a comment online.

- Call the Department of Defense and ask Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel to issue certifications for other cleared prisoners: 703-571-3343.

Please also feel free to write to the prisoners at Guantánamo.

Note: This article was published simultaneously here and on the website of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer and film-maker. He is the co-founder of the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK) and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here – or here for the US).

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, and “The Complete Guantánamo Files,” an ongoing, 70-part, million-word series drawing on files released by WikiLeaks in April 2011. Also see the definitive Guantánamo habeas list and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the “Close Guantánamo” campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

March 17, 2014

From Guantánamo, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed’s Declaration in the New York Trial of Sulaiman Abu Ghaith

On Sunday night, I received a fascinating document from the lawyers for Sulaiman Abu Ghaith, who is on trial in New York — a 14-page statement by Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, written in response to questions the lawyers submitted to him at Guantánamo, where he has been held since September 2006, following three and half years in “black sites” run by the CIA, where, notoriously, he was subjected on 183 occasions to waterboarding, an ancient torture technique that is a form of controlled drowning. I am posting a transcript of the statement below, as I believe it is significant, and it is, of course, rare to hear directly from any of the “high-value detainees” held at Guantánamo, because every word they speak or write is presumptively classified, and the authorities generally refuse to unclassify a single word.

On Sunday night, I received a fascinating document from the lawyers for Sulaiman Abu Ghaith, who is on trial in New York — a 14-page statement by Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, written in response to questions the lawyers submitted to him at Guantánamo, where he has been held since September 2006, following three and half years in “black sites” run by the CIA, where, notoriously, he was subjected on 183 occasions to waterboarding, an ancient torture technique that is a form of controlled drowning. I am posting a transcript of the statement below, as I believe it is significant, and it is, of course, rare to hear directly from any of the “high-value detainees” held at Guantánamo, because every word they speak or write is presumptively classified, and the authorities generally refuse to unclassify a single word.

Abu Ghaith (also identified as Sulaiman Abu Ghayth) is charged with conspiracy to kill United States nationals, conspiracy to provide material support and resources to terrorists, and providing material support and resources to terrorists, primarily for his alleged role as a spokesperson for Al-Qaeda immediately after the 9/11 attacks. Following the US-led invasion of Afghanistan, he fled to Iran, where he was held under a form of house arrest — and where he met and married one of Osama bin Laden’s daughters, who was also held under house arrest — until January 2013, when he was released to Turkey.

It was at this point that the US authorities became aware of his release from Iranian custody. At the request of the US, he was briefly detained, but soon released because he had not committed any crime on Turkish soil. The Turkish government then apparently decided to deport him to Kuwait, but on a stop-over in Amman, Jordan, he was arrested by Jordanian officials and turned over to US officials, who subsequently extradited him to the United States.