Kristen Lamb's Blog, page 23

March 27, 2018

The Dangers of Premature Editing: Pruning Our Stories vs. Pillaging Them

[image error]

Editing is essential for crafting a superlative story. We clip away the excess, delete the superfluous and prune away the detritus to reveal the art. Yet, editing is something we’re wise to handle with care.

While lack of ANY editing is a major problem today, editing too much, too soon is just as big of a problem. Perhaps an even a bigger one.

For clarity, not all ‘editing’ is the same.

Today, we aren’t discussing proofreading and line-edit. Correcting punctuation, spelling, and grammar is perfectly fine. Moving some commas around is unlikely to endanger story integrity. We’re addressing the perils of premature content edit/developmental edit.

If we think about this for a moment, what I’m saying should make sense. If a work is only partially finished, there’s no way we can truly know what to cut and what to keep. We don’t yet have enough content/context necessary for clarity.

Editing too early is detrimental in a variety of ways.

Early Editing Uproots Subconscious Seeds

[image error]

Our subconscious mind is an amazing machine. Stephen King referred to the subconscious as ‘the boys in the basement.’ The prudent author allows those ‘boys in the basement’ to do their thing.

The best way to help? Stop interfering. The subconscious mind can see the big picture in ways our conscious mind cannot.

Unlike our conscious mind, the subconscious is always working. Busy, busy, busy. It’s fitting all the pieces together in ways we’d have a tough time consciously doing.

King has his analogy, and I have mine. I think in terms of planting and cultivating a garden.

We have a story idea (overall image of the ‘garden’ we want). Then we might write out a log-line, major plot points or detailed outline (a plan). Overall, we’re at least generally aware of the story we want to create.

As we write, our subconscious mind is planting seeds that, when viewed in a microcosm of one or three chapters, will frequently seem to make no sense. The idea needs time to put down roots and grow large enough for the conscious mind to accurately discern whether it’s something to keep or something to cull.

[image error]

Also a garden generally is not a singular plant. A garden is comprised of many plants of various types, colors, heights, widths, etc. Until our garden reaches a point where we can get a view of the creation as a whole we’re wasting time. Pruning, moving, replacing is wasted time and energy because we’re working blind.

Maybe that hyacinth needs to be moved because it’s too tall OR maybe we need to chill out and wait for the peonies planted nearby to come in.

Once all we’ve planted grows and blooms, THEN we have a way better idea of what plant needs to be moved, which should be filled in more (add in more coleus), and what’s a WEED that needs to GO.

Story as a Garden

[image error]

I love to garden. In the fall, I decided to start over after a blight ravaged everything I’d cultivated for six years. I removed all the plants, and prepped for spring. After widening the stones (since I wanted a larger garden) I filled the area with at least a couple thousand pounds of clean soil topped with mulch.

Since I had yet to plant anything intentionally, anything that popped up over fall and winter clearly was a weed.

GONE!

This all changed once I began planting. I had an idea of what I wanted: a beautiful garden bursting with blooms known to attract hummingbirds and butterflies.

Once I had the idea, I planted the bulbs and spread the seeds. Yet, if I ever hope to have my dream garden, it’s critical for me to resist the impulse to pull anything green and sprouting because it ‘might’ be a weed.

Until whatever seedling poking through the mulch grows to a certain point, I have no way to discern flower from weed.

Same with story. We don’t realize that a possibly mind-blowing idea is trying to germinate and take root in the fertile soil of our overall idea.

By editing too early, we can possibly uproot some mind-blowing twist or turn. We might remove the wrong character or delete a scene that should have stayed.

Y’all might find this hard to believe, but it actually is possible to edit all the life/magic out of a story.

Early Editing Feeds Fear

[image error]

All writers experience fear. Many of us suffer from Imposter Syndrome. We’re prone to believe unless we are a New York Times best-selling author we are a fraud. If we don’t have twenty books under our belt or an HBO mini-series based off our stories, we aren’t real authors.

The problem is that we’ll never have ANY of this if we consistently fail to finish. Perfect is the enemy of the finished. No half-finished novel has ever become a runaway success.

A story doesn’t have to be ‘perfect’ to be a hit. In fact, plenty of decent and even some outright dreadful novels have skyrocketed to the top of the charts.

Stories (like all art) are subjective. It’s impossible to craft a story everyone will love. There are way more than fifty shades of reader preferences.

Fear can paralyze productivity and halt professional growth. You know what? Maybe our novel is awful, but that isn’t necessarily because we lack talent.

We might simply be NEW. How many of you can pick up an unfamiliar instrument and are immediately ready to play on stage for money?

Storytelling is an artisan skill that takes years of training and practice. We get better by doing, by failing, then understanding what went wrong where and why. Then, armed with this new insight we write another story, and a better story.

Poisonous Perfection

[image error]

Editing is a common coping mechanism used to allay anxiety. Maybe we fear we really aren’t any good. We really are talentless hacks. Our book is terrible. Why are we even doing this? A brain-damaged hamster has more talent. On and on.

Thing is, perhaps all of this is true. We won’t know until we submit a finished product for peer review (and even then nothing is set in stone).

Yet, if we keep editing and reworking, this buys us time. We want to know if our writing is any good, but also can’t bear to think it might be truly awful. So long as we remain in literary limbo, we can hold onto our illusions.

My book is as good as (insert mega author), even better! I just have to tweak a few scenes before querying…

I want all of you who’ve even started writing a novel to embrace what a HUGE step that is. The world is brimming with people who spout nonsense like, ‘Yeah I always wanted to write a book, except I never could find the time.’

In their minds the ONLY reason they aren’t the next George R.R. Martin is a lack of time-management skills. We all know this is bunk. And yet? We have to be really careful we aren’t doing the same thing.

Getting past the hard part—starting—is a fantastic step. Now finish. Pros don’t find time, we make time.

Early Editing KILLS Momentum

[image error]

If we continue to go back changing things chapter by chapter, changing, changing, changing, either due to critique group feedback or our own self-edit, what happens is that we KILL our forward momentum with a big ol’ red-penning, back-spacing machete.

We can prune or progress.

Do that long enough, and it becomes hard not to be discouraged and ultimately give up. If you have been reworking the first act of your book for months, it can very easily end up in the drawer with all the other unfinished works.

Beginnings are not something I recommend spending too much time ‘perfecting.’ The big reason is that very often beginnings will change. Once we write the entire story and actually possess the BIG PICTURE, only then can we judge the merit of any opening.

We may have started too soon, too late, with the wrong hook, etc. Yet, if we spend weeks or months futzing with the opening, we get far too attached.

This means it’s all the harder to let it go because it’s a Little Darling. I’ve seen writers crater excellent plots because they refused to part with the opening they love. They would rather retrofit the rest of the novel than cut or change the beginning.

Great, now we have a super pretty opening…but the rest of the story is ‘meh’ because it’s all been redneck engineered to serve the first chapter(s) instead of the overall story.

An Editing Process I Recommend

[image error]

There is no ‘right’ way when it comes to process. All I can do is possibly share one to try. If you have a way that works? Fabulous. But, if you have a hard-drive bursting with unfinished stories, maybe try something new.

When I write a book (fiction or non-fiction) I leave any kind of content edit for after I’ve finished the entire first draft. FYI: Any time I ignore my own advice and don’t do this? It’s a disaster.

Now, is it okay to reread what we’ve written the previous day (session) in order to get grounded? Absolutely! It’s also perfectly fine to correct spelling, grammar, and punctuation errors.

But, if the correction has anything to do with the STORY (narrative, dialogue, setting, etc.), instead of deleting and/or ‘fixing,’ try this. Make notes of what places you believe at the time should be fixed, deleted, changed or even expounded.

NO changing or deleting. Period. Feel free to highlight and…

Make Notes then Move ON

[image error]

My advice is—instead of changing/correcting, etc.—to make a note that you believe something should be taken out/added/changed at a later time, but leave it be. I also recommend making notes in color. Red, purple, blue.

This technique is valuable in other ways. For instance, it helps maintain momentum when we hit places in the WIP where we need to fact check or research. I’ve been coauthoring a Western and am new to writing historical.

Trust me, it’s easy to lose a whole day on the Internet researching. Instead of stopping, I might write the scene with the people and in another color, make a note, ‘Research first class trains in 1870s.’

This allows me to keep writing instead of wandering off and making myself an expert in 19th century American rail travel.

Another way this method helps is if you’re writing and find yourself STUCK. If you have a log-line and a solid plot idea that’s fantastic. Yet, there will be times when we can’t seem to fit the pieces together…so skip ahead.

When I hit a wall, I might write ‘AND THEN ROMI DOES SOMETHING COOL AND FINDS A CLUE’ and pick up at the next logical place. In the meantime, my subconscious will be working on my problem even while I sleep.

Often the ‘answers’ my subconscious comes up with are WAY better than anything I could have planned. This also makes for some psychedelic dreams

March 20, 2018

Fizzle or Sizzle? How Genre is Fundamental for Story Success

[image error]

Genre is a word that makes a lot of new writers cringe. Many (mistakenly) believe any kind of boundaries will somehow impair or restrict creativity and crater imagination. This is why so many emerging authors (myself included) avoid learning about structure or how to plot until forced to…at gunpoint.

Fine! Yes, I’m being melodramatic, but close enough to the truth.

It’s easy to understand why we want to skip all that boring stuff. We’re eager to write, to create, to unleash the muse! Yet, in our haste, we can lose sight of what we stand to gain by truly understanding the fundamentals and respecting boundaries.

For any author who wants to eventually sell enough books to make writing a full-time occupation, genre is one of our greatest allies.

Genre Dictates Location

[image error]

Location, location, location. Yes, I remember being a neophyte, breaking out in hives when anyone mentioned I needed to choose a genre *shivers*. My book wasn’t a genre, it was all genres. It was a novel everyone would love. I didn’t need something as prosaic as…genre.

Yes, I was a clueless @$$hat so y’all can already feel better about yourselves. When we’re new, obviously we don’t understand the intricacies of the publishing profession. Why? BECAUSE WE ARE NEW.

***By the way, it is okay to be new. We all begin somewhere. Stephen King didn’t one day hatch as a mega-author.

Before we even get to how genre impacts story, we must remember publishing is a business. Many of you long to submit to an agent in hopes of a sweet contract with the Big Five. Great! You yearn to see your books on a shelf in a bookstore. Wonderful! Me too. *fist bump*

So where would the bookstore shelve your novel?

This is a critical question all writers must be able to answer. Ideally, we need to know our genre before we ever begin writing the novel, for reasons we’ll get to in a moment. But first…

Genre Lands Book Deals

[image error]Meh…there are better ways.

If we want to publish traditionally (legacy) the first step—beyond finishing the book, obviously—is landing an agent. Writers who take the business seriously research agents ahead of time because this is a partnership.

We don’t want just any agent, we want the right agent. Conversely, agents aren’t looking for any book, they’re on the hunt for books they can sell.

Most agents have a list of the sort of books they’re in the market to represent (which genre). Thus, if an agent’s bio states she’s looking for Young Adult and New Adult novels, we’re wasting her time and ours by querying our Middle Grade series. By doing a bit of research, we can locate agents who’ll be the ideal fit.

Agents create these wish lists for a reason. They know publishers all have wish lists, too. The agent’s job is to pay attention to those wish lists and hustle to deliver the goods. Their goal is to sell our book to a publisher and negotiate the sweetest deal possible for us (the author), because this benefits them, too.

Agents pay attention to the publishers’ shopping lists. If the publishers are no longer wanting Dystopian YA novels, the agent then knows that trying to sell the next Hunger Games is a fruitless endeavor.

Even if our book IS the next Hunger Games, agents won’t rep it because they already know they’re highly unlikely to sell it.

Genre Sells Books

[image error]

Now, traditional publishers might reject a certain genre for any number of reasons that have nothing to do with the quality of the book. Maybe they’ve already filled the X amount of slots reserved for a Dystopian YA. They don’t want to oversaturate the market. Perhaps Dystopian YA is not selling like it used to because Steampunk YA is picking up steam *bada bump snare*.

Thus, if you have an amazing Dystopian YA, you can go indie (if they’re open to representing it) or self-publish. Genre is still incredibly important because when we list our book for sale on-line, again, we have to tell Amazon (and other on-line distributors) where our story belongs.

Major publishers do, too.

Genre will directly impact metadata and will serve as a guide for keyword loading within the product description. Genre and the associated keywords will also influence which books are listed alongside ours (or vice versa). When we look up Gone Girl, we see…

[image error]

This is how on-line retailers help readers find books they’re likely to enjoy more easily.

Genre Draws Fans

This is one of the reasons we really don’t want to write a novel totally unlike ANY other. The story never before told is a unicorn, first of all. It doesn’t exist.

Also, a novel that can’t be fit into any genre is unlikely to draw fans. Whether readers are browsing a bookstore or browsing on-line, they generally know what sort of books interest them and head that direction.

If they’ve just finished Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl and they’ve read all of Flynn’s other books and want to read more books LIKE hers, genre is the flashing arrow pointing readers to similar novels (and authors).

This is a fantastic way for authors who aren’t yet household names to be discovered. Fans of the genre can then evolve into fans of that author.

Because readers can discover our work on a shelf or on-line, our odds of selling more books vastly improves.

This isn’t rocket science. People are unlikely to buy something they a) don’t even know exists or b) can’t find.

Genre Builds Brands

[image error]

As Cait mentioned in her post on best practices for publishing success, genre focus is a major factor in becoming a successful author. When we focus on a specific genre we build an author brand and cultivate a devoted fan base far faster.

A qualifier here, though. Just because we write a Psychological Thriller doesn’t mean we must only write Psychological Thrillers forever and ever. Often genres have ‘kissing cousins’ and, so long as we remain within that general genre region, it’s all good. Suspense, Mystery, Thriller, Sleuth, are close enough to count.

Once we’ve published enough books, built a solid brand and cultivated a large devoted fan following, then we gain more freedom to try something new.

Genre Helps Plotting

[image error]

When we choose any genre, there are certain reader expectations. Once we know what’s expected, we can then deliver what readers want. We also have a better idea how to plot. If we don’t understand how/why a thriller is different than a suspense, that’s a problem.

Let’s use these ‘kissing cousin’ genres as an example…

A thriller has large (global) stakes on the line. In the beginning a bad thing happens and it is a race against time to stop the MASSIVE bad thing by the end.

For instance, Lee Child’s debut novel Killing Floor is about a former MP-turned-drifter thrust by fate into a problem with global consequences. Reacher’s goal is to stop bad guys’ plan to inundate the market with counterfeit bills (which would destabilize the U.S. economy).

A suspense has more intimate stakes. In Thomas Harris’ book The Silence of the Lambs, the goal is to find and stop Buffalo Bill from murdering Size 12 women for his ‘woman suit.’ Ideally, Agent Starling will stop Buffalo Bill before the latest victim (a senator’s daughter) is killed. The stakes, however, are not global.

The F.B.I.’s image is at risk, Starling’s career is on the line, the latest victim’s life is in jeopardy, but overall?

Skinny girls are totally safe.

When we understand the dictates of a genre, we can plot better and also know what we’re selling (to agents, publishers, and readers).

Genre and Structure

Since this week is my birthday and the week I am re-launching my novel, The Devil’s Dance I’m going to indulge

March 16, 2018

How to Write Unforgettable Settings Readers Never Want to Leave

[image error]

Setting is an extremely powerful tool that can hook readers into a world they never want to leave. Oddly, too many writers fail to appreciate just how powerful settings can be. Details make the difference between the mediocre and the magnificent. Settings, written properly, can come alive and transition from boring backdrop to becoming an actual character (I.e. Hogwart’s).

Setting should be more than a weather report or a simple description of a room. When we harness the power of settings, we add in nuance and layers, give characters far more dimension, and deepen the emotional timbre of voice.

Today, we have a special treat. Award-winning author, Christina Delay (who’s represented by The Knight Agency) is here to give us tips to elevate the meh to the magical.

Take it away, Christina!

The Power of Settings

[image error]

You know that feeling when you read a masterful piece of writing and your entire world fades away? It’s as if you feel this inaudible click as those words shape themselves into a key that unlocks a place inside you?

Wanna write a scene like that? (Of course you do, so keep reading!)

Most unforgettable scenes have one central element that the author focuses on. It can be the emotion conveyed in the scene, a character revelation, an action-packed fight, or quick-witted dialogue, but every one of these elements has a central device that must be included.

Setting.

Without setting as the backdrop to each of these integral story elements, they simply cannot carry the power. It’d be like watching a film before it was edited, and you realize that the roaring dragon is really a stick with two legs and some wires propped in front of a green screen.

Setting carries your story.

So why pick boring, beige places to set scenes? Which would you prefer? Hanging out in a dentist’s office for 12-15 hours or wandering around The Shire for 12-15 hours?

Readers are the same.

Tips for Writing Unforgettable Settings

[image error]

Focus on Details

For scenes that need to pack a punch, delve into the details. Much like visiting a new place for the first time, in those scenes we need to have time to look around and soak it all in. We need to adjust our scope so that we take a close-up view of a few details.

But make these details specific.

Which moments or parts of the setting mean something to your character? And why? These are the moments we can reveal a little piece of backstory about our character, or allow a piece of the setting to lead them to a revelation.

Take this example from Tana French’s The Likeness and pay close attention to what she does with the details:

But children are pragmatic, they come alive and kicking out of a whole lot worse than orphanhood, and I could only hold out so long against the fact that nothing would bring my parents back and against the thousand vivid things around me, Emma-next-door hanging over the wall and my new bike glinting red in the sunshine and the half-wild kittens in the garden shed, all fidgeting insistently while they waited for me to wake up again and come out to play. I found out early that you can throw yourself away, missing what you’ve lost.

Share Setting Secrets

[image error]

Even if we’re writing a scene in Nowhereville in the middle of the desert where there’s nothing to meet the eye, work to find the secret of that locale to make it come alive. If we can’t find or create that secret, then that’s a setting best forgotten (changed) because it won’t resonate with readers.

In my personal travels and my travels with Cruising Writers, I always look for the secrets that only a person who had been there before would know.

For example, our Cruising Writers retreat to France in 2017 opened my eyes to a whole new level of setting. From the ruby red of poppies brushing against the bare vines of a French vineyard to the muted sound of church bells, muffled by wisps of fog, to the ruins of castles and tower lookouts speckling the rolling hills of vineyards.

After visiting France, you might bring in the dust from the unpaved roads or the narrow streets that American cars could never fit on, the paint on the edges of 500-year old buildings that have been scraped off of cars clipping their corners.

Maybe you’ll bring in the dog with sanitation issues that leaves a trail all around the French farmer’s market.

In every overarching setting you select for your book, find the secrets that only you know that will also bring to life the world for your readers.

Remember the Power of Lighting

[image error]

Have you ever noticed that sunlight looks different depending on where you are? Warm oranges and soft yellows weave between the trees during sunset on the West Coast. Sunset on a Caribbean cruise is neon and full of glamour. Think about what else comes with light and strive to thread those elements throughout your writing.

The feel of the summer sun on your skin after you’ve climbed out of freezing cold water, how your skin prickles when you pause in front of that diamond of light pouring in from a window in the middle of winter. The way the light can appear ominous or heavenly when set against a storm.

[image error]Beyond Google Earth

When you hear the writing advice, ‘Write what you know,’ I believe that applies to setting as well as theme. I’ve lived in Houston, Texas most of my life. This means I can write the details of living in Houston better than someone who lives in California, because I understand the nuances of my city.

Likewise, I can write the setting details and secrets of a cruise ship much better than someone who has never been on a cruise, but less well than crew member who lives on the ship. Google would only get me so far in doing research on a location. The best way to really get the details right is to visit the place in which we’re setting our story.

Write Settings That WOW!!!

Boring, dull, or filler settings? Who has time for that? There are so many books out there, so many titles to choose from, and readers want to be wowed. Settings can separate the so-so stories from the so-long and NEXT!

Setting is one of the most memorable parts of any great story, and as storytellers we need to give it the weight it deserves. Follow these tips, focus on the details, the secrets, and the firsthand experience, and elevate your writing to an entirely new level.

Do you agree that setting is one of the most important story elements? What are some of your tricks for writing unforgettable settings?

Thanks Christina!

As y’all can see from her bio (below), Christina is hostess of the Cruising Writers and this year I’m one of the SPEAKERS *evil laugh*. So if you have long dreamed of being trapped on a boat in the middle of the ocean with me…

What? The Stockholm’s sets in quickly

March 13, 2018

Dreams or Delusions? The Real Odds of Author Success

[image error]

Many new writers have a passionate dream of being a full-time, well-paid, maybe even famous author…until we see the odds of reaching those dreams. Then? All our enthusiasm and optimism suddenly leaks out *farting sound of deflating balloon* leaving space for doubt, anxiety, and defeatism.

Granted, odds of author success will be different depending on the dream, what our idea of ‘success’ happens to be. The odds of ‘being published’ today are far better than when I started out, but ‘being published’ is no longer the single largest challenge we face.

[image error]Not quite, but close.

If we want to replace the day job with being a full-time author–whether that is on a self-published, indie, legacy, or hybrid track—we have some tough work and tougher decisions ahead. I do have good news, though. While our mind can be our greatest enemy, it can also be our greatest ally.

Perception dictates reality.

This means we need to get our head in the game and make certain we’re framing our goals in a way that increases our odds of realizing our dreams.

Do Some People Lack the Talent to be Authors? Sure. But, in my eighteen years of experience, I’ve found that’s actually quite rare.

Why most writers fail to transition from amateur to pro has less to do with lack of innate talent and far more to do with a lack of a professional’s mindset and work ethic. We can’t keep amateur hours and hobbyist habits and expect to reap professional rewards. That’s basic logic.

Blind luck is an option. It’s a sucky one. But it is still an option. For those who want more than blind luck, how does this all shake out?

So glad you asked!

What Are the Odds….Really?

[image error]

I didn’t even consider becoming a writer until 1999 after my father passed away suddenly. Funny how death can make us take a hard look at life, right? Anyway, I recall feeling soooo overwhelmed. I mean my odds of even getting published were about as good as winning the Power Ball.

And the odds of becoming a best-selling author? Well, mathematically speaking, I had a slightly greater chance of being mauled by a black bear then hit by lightning…on the same day. Plenty of people told me the odds. Encouraged me to get a ‘real job’ instead of chasing rainbows.

Between the negative voices in my head and the dream-killers posing as ‘concerned friends and family,’ it was all I could do not to give up before I began.

Fresh Eyes

[image error]

After countless rejections, stories that fizzled, and failure after failure I hit a low point. Then, I realized my perspective about my odds of succeeding were skewed in a self-defeating direction.

Often it feels like we are the victims of fate, at the mercy of the universe, when actually it is pretty shocking how much of our own destiny we control.

The good news is that if we can get in a habit of making good choices, it is staggering how certain habits can tip the odds of success in our favor.

Time to take a REAL look at our odds of success. Just so you know, this is highly unscientific, but I still think it will paint a fairly accurate (and encouraging) picture.

The 5% Rule

[image error]

It has been statistically demonstrated that only 5% of any population is capable of sustained change. In lay terms, we call this GRIT. Though grit is simple enough in concept, training grit into our character is a lot of hard work—which explains why it’s called grit not a sparkle unicorn hug. Developing grit is a bumpy ride with more lows than highs, which is why long-term grit is a rare.

Thus, with that in mind…

When we start out, we’re up against presumably tens of millions of others who want the same dream we do. Yes, tens of millions. It is estimated that over 75% of Americans claim they’d one day like to write a book (and this is just Americans).

That’s a LOT of people.

From one angle, it’s easy to believe our friends and family are right. We DO have better odds of being taken hostage by feral circus clowns than earning the title New York Times Best-Selling Author.

*sobs*

Yet, I believe this generality isn’t entirely accurate because it fails to take into account the choices we make. These ‘odds’ aren’t factoring in how many variables are within our control.

Let’s say we accept we’re up against presumably tens of millions of others who desire to write a book/become a famous novelist.

Ah, but how many even start? How many decide to look beyond that day job? How many dare to take that next step and write even a single page?

Statistically? 5%.

Feeling Lucky? Upping Our Odds

[image error]

So only 5% of the tens of millions of people who desire to write will ever even take the notion seriously. This brings us to the millions.

But of those millions, how many who start writing a book will actually FINISH that novel? How many will be able to take their dream seriously enough to set firm boundaries with friends and family and hold themselves to a self-imposed deadline?

Statistically? 5%.

Okay, well now we are down to the hundreds of thousands. Looking a bit better. But, finishing a book isn’t all that’s required. We have to be able to write a book that is publishable and meets industry/reader standards. How many who write a novel will hire a seasoned content editor to make sure it really is…a book?

5%.

Or, if they don’t hire a content editor, how many join a critique group for professional feedback?

5%.

Ah, but this is where it gets tricky…the place where many writers who make it this far get stuck.

Aspiring Writers vs. Pre-Published Authors

[image error]

The best dose of humility I ever received was in my first critique meeting with ACTUAL authors (as in NYC published). I thought my novel was the best thing since puffy kitten stickers, and OMG so did everyone else!

It was AMAZING. They all wept because they’d failed to bring enough star stickers to paste all over my pages! No rose petals to throw at my feet! No lyres to sing songs of my book’s greatness!

….or not.

More like I spent an hour ugly-crying in my Honda, wondering if throwing myself off the library would kill me or merely wing me.

Despite the sound beatings, I sucked it up and returned week after week. I kept at it and improved despite having to sweep up my pride and self-esteem at the end of every meeting.

This said, how many take the step to attend a critique group, and then stick to writing even after a blistering critique? Many blistering critiques?

5%.

This marks a major fork in the road. The critique stage is the dangerous level. We’ve made it SO far…but can end up jammed in the funnel.

Talk is Cheap

[image error]

As a neophyte, I truly believed everyone who attended a writing critique group would be published. I mean they were saying they wanted to be best-selling authors. I was saying it.

But did they mean it? Did I mean it? Good question. But first a test…

How many of you reading this refer to yourself as an ‘aspiring author?’ Raise your hand. No one can see. Now, if you raised your hand, slap yourself HARD and never use that title again.

O_o

If we don’t take ourselves seriously, why would anyone else? So long as we refer to ourselves as ‘aspiring’ we’re locking into a hobbyist/dabbler mentality. To go pro, we need to think pro.

From now on, I recommend pre-published author or emerging author. I use pre-LEGEND

March 7, 2018

Character Building: How Story Forges, Refines, and Defines Characters

I put in a lot of work and study when it comes to honing my writing skills. This means I’m always searching for ways to become a stronger author and craft teacher. Want to get better at anything? Look to those who are the best at what they do and pay close attention.

This said, wanting to deepen my understanding of drama, I enrolled in David Mamet’s on-line course for Dramatic Writing (which has been superlative). In one of the lessons, Mamet said something that challenged my thinking regarding characters.

I won’t directly relay what his assertion was because it’s very much a class worth taking, and I’d hate to spoil it for anyone. Regardless, his commentary regarding character creation made me extremely uncomfortable.

At first, I balked. Big time. Challenging ideas do that.

I thought, Yes, well Mamet’s referring to stage and screen. With written fiction we have narrative. Actors don’t possess this.

Which IS true, yet Mamet’s unconventional opinion stopped me long enough to give his angle some serious consideration. Did his assessment relate to our sort of fiction?

Craft Crossover?

Written form stories hold some major advantages, the largest of those being internal narration. The audience knows what’s going on in the head of the character (or can believe they know).

On stage or screen, it’s up to the actors’ abilities to accurately portray the internal, which is a tough order. It’s also why if a book is made into a movie, watch the movie first.

Otherwise…

[image error]

This largely has nothing to do with the quality (or lack thereof) regarding the play/film. Internal narrative allows for a far more intimate psychic distance that is ONLY possible in the written form.

The medium is different and thus should be judged differently…though we still gripe the book was WAY better.

Stage and film rely on the screenplay which is very BASIC. It’s all dialogue and up to the director’s vision and the actors’ talent. Character creation for stage and screen cannot help but differ from written form, yet by how much? What can we learn from our sister mediums?

****Other than Sister Mediums is a way better reality show concept than Sister Wives? #SquirrelMoment

Character Creation

[image error] Image courtesy of Kevin Wood via Flickr Creative Commons

I thought back over works I’d edited, earlier stories of my own and had a moment of revelation. Why were some characters so flat? As interesting as some form-molded widget popped off on an assembly line?

Conversely, what made other characters almost come ALIVE?

What was the X-factor?

Now that I’ve noodled this, I’ve revised some of my thinking. Multi-dimensional characters are not something writers can directly create. Rather, these lifelike people are forged from the crucible of story.

Dramatic writing uses a core problem (fire). The core problem generates escalating problems (the hammer). The trials (increasing heat/hammering) reveal, refine, define, and ultimately transform the narrative actors into characters.

Story alone holds the power to bestow resonance.

Fill-In-The-Blank People

Sure, we can do all the activities of filling out a character profile. But, these character sheets alone are about as telling as a ‘fill-in-the fields-profile’ on a dating site. Height, weight, build, nationality, attractiveness, education level, how many kids, previously married, hobbies, etc.

Dating profiles also provide blank spaces for additional ‘deep, character-revealing statements’ such as: I’m not a game-player, love Mexican food, and my favorite activities are crossfit and hiking.

FYI: ALL of that is likely a lie (other than enjoying Mexican food). Anyone who starts with I am not a game-player is almost guaranteed to be a game-player. It’s Shakespeare’s Rules of Romance. Or, as I call it, ‘The Lady/Dude Doth Protest Too Much’ litmus.

Anyway…

No School Like Old School

[image error]….or not.

Do I create character profiles? Sure. I also put a lot of thought and research into what ‘people’ I want to cast in a given story. It’s a great activity, but be careful. We can’t camp there. Activity and productivity are not synonymous.

Ultimately, fictional characters reflect the real human experience in a distilled and intensified form. This, however, doesn’t give an automatic pass on authenticity.

Aristotle might be Old School, but his observations regarding drama resonate even into the 21st century. In Aristotle’s Poetics he asserts:

Since the objects of imitation are men in action, and these men must be either of a higher or a lower type (for moral character mainly answers to these divisions, goodness and badness being the distinguishing marks of moral differences), it follows that we must represent men either as better than in real life, or as worse, or as they are. ~Aristotle

This gives three schools: Polygnotus (more noble), Pauson (less noble), and Dionysius (real life).

[image error]

Even today these three schools of story thought are alive and well. Marvel’s Captain America movies proffer the larger-than-life hero, the man better than real men (Polygnotus).

Westworld and Game of Thrones provide a vast assortment of villains who are worse-than-life, an exaggeration of evil (Pauson).

Then, movies like Training Day or Glengarry Glen Ross show men as they really are…flawed. They’re not entirely noble or ignoble (Dionysis).

Granted, this is a vast simplification, but we can see novels fall into these schools as well. Genre dictates a lot of this. Harry Potter, The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo, and A Man Called Ove could reasonably be placed in each category.

Talk is Cheap

[image error]

Why do I mention these ‘schools’ of story? Depending on genre, readers will have expectations when it comes to what they’ll find entertaining. As writers, our primary job is to entertain. This said, stories are for the audience. This means we need to either serve them what they enjoy, or serve them what they don’t yet know they will enjoy

March 1, 2018

When Ideas Collide: Powerful Storms Make Superior Stories

[image error]

Every story begins with an idea. Alas, stories can only be created when at least two vastly different ideas collide. The place where they meet is the BOOM, much like the weather. Storms erupt because two very different bodies of air meet…and don’t get along.

Only one will win out. In the meantime, lots of rain, lightning strikes and maybe some tornadoes. After the powerful storms, the landscape is altered, lives are changed, some even lost.

It’s the same with powerful stories. Yet, instead of weather fronts colliding, differing ideas are colliding.

It’s wonderful to have a great story idea. Alas, an idea alone is not enough. It’s a solid start but that’s all. Loads of people have ‘great ideas’ and that and five bucks will get them a half-foam latte at Starbucks.

Ideas are everywhere.

What differentiates the author from the amateur is taking the time to understand—fundamentally—how to take that idea and craft it, piece by piece, into a great story readers love.

Building Ideas into Stories

[image error]

Stories have key components required for building, and I promise we’ll get there. My goal, this go-round has been to elevate the teaching and deep-dive in a way I hope you’ve not experienced before.

I always found craft teaching either was so simplistic I was all, ‘Got it, sally forth.’ *taps pen* Or, the instruction was so advanced (assuming I was far smarter than I was) and it made me panic more than anything.

Like the ‘write your story from the ending.’ Sure, meanwhile, I’ll go build a semi-conductor.

There was this MASSIVE gap between X, Y, Z and why I was even doing X, Y, and Z. Why not Q?

And all to what end? How did I make all the pieces FIT? *sobs*

[image error]

Anyway, this is why we’re taking things SLOWLY. I want to fully develop these concepts so you can create incredible stories far more easily. Yes, this is master class level stuff, but hopefully I will help mesh with 101 concepts so even beginners will feel challenged (as opposed to utterly LOST like I did).

For those new to this blog or anyone who wants to catch up, here are the lessons so far:

Structure Matters: Building Stories to Endure the Ages

Conflict: Elixir of the Muse For Timeless Stories Readers Can’t Put Down

The Brain Behind the Story: The Big Boss Troublemaker

Problems: Great Dramatic Writing Draws Blood & Opens Psychic Wounds

How to Write a Story from the Ending: Twisted Path to Mind-Blowing End

Ideas as Character Catalyst

[image error]

When we discussed the BBT, I showed how all BBTs are an IDEA. This IDEA might manifest as a villain or as a core antagonist. The core antagonist only different from a villain in that this person’s goal is not inherently destructive, evil or nefarious. Their idea(s) simply conflicts with what the protagonist’s idea(s) and what the MC believes he/she desires.

This antagonist generates a core story problem BIG enough to shove the protagonist out of the comfort zone and into the crucible. This pressure (problems) creates heat which is the catalyst that creates the cascading internal reaction which will fundamentally alter the protagonist.

These internal changes are necessary for victory over the story problem via external action (choices/decisions). The MC cannot morph into a hero/heroine carrying emotional baggage, false beliefs, or character flaws present in the beginning. Why?

Because these elements are precisely WHY the MC would fail if forced to battle the BBT head-on in the opening of the story.

The story problem, and what it creates, is like a chemical reaction. Our protagonist, by Act Three should transform into something intrinsically different…a hero/heroine (a shining star instead of a nebulous body of gas). The problem should be big enough that only a hero/heroine is able to be victorious.

Villains as BBT

[image error]

Villains are fantastic and make some of the most memorable characters in fiction whether on the page, stage or screen (Joker, Buffalo Bill, IT, Dr. Moriarty, Cersie Lannister, etc.). A common misperception, however, is villains are ‘easy’ to write. No, mustache-twirling caricatures are easy to write. But villains, villains that get under our skin, who poke and prod at tender places take a lot of preparation and skill.

Dr. Hannibal Lecter is extremely dimensional. We, the audience, are conflicted because he’s horrible, grotesque, cruel… and suddenly we find ourselves rooting for him.

That seriously messes with our heads.

Dr. Lecter has an IDEA of polite society. Act like a proper human and be treated like one. His IDEA of what a human is entails all that separates us from animals, namely manners and self-control. Act like a beast, and beasts–>food.

This cannot help but conflict with any FBI agent’s duty to protect all lives (deserving or not), and help mete out justice in all homicides (even of those horrible folks we’re all secretly happy Hannibal made into a rump roast).

All I can think is thank GOD Lecter is fictional or half the folks on Facebook would now be curing world hunger.

Anyway….

Superb characters are never black and white, right or wrong because that’s an inaccurate reflection of humanity.

We (the audience) sense the falseness of such a simplistic character, and, while one-dimensional characters (villains included) can be amusing for a time, they’re not the sort of character that withstands the test of time. They don’t possess enough substance/dimension/gray areas to elicit heated debate and discussion among fans for years to come.

But villains are not ideal for all stories or all genres.

Core Antagonist as BBT

[image error]

There are what people call character-driven stories which don’t require a villain. I twitch when I hear the term ‘character-driven’ because too many mistake this as a pass for having to plot. NOPE. We still need a plot

February 27, 2018

How to Write a Story from the Ending: Twisted Path to Mind-Blowing End

[image error]

Now that we’ve discussed the Big Boss Trouble Maker who creates the core story problem in need of resolution, we’re going to tackle…endings. When we authors know our story ending ahead of time, we gain major creative advantage.

What is this madness? How can I know the END?

Calm down. I’ve been there, too. Which is why I’m here to walk you through and help this puzzling concept make total sense.

*hands paper bag*

If you’ve followed this series on structure, you already know why the BBT is so critical. The BBT creates the external problem that launches everything to come, the problem to be resolved (ending).

No Darth Vader and Luke likely remains a moisture farmer on Tatooine. Unless there’s a major external problem—Darth Vader and a Death Star—Luke can/will never become a Jedi.

No WWI pilot crashing through the veil hiding Themiscyra? Amazons continue doing Amazon stuff. Without the pilot, and the massive threat beyond the bubble (pre-Nazis), there is no external force burdening Diana of Themyscira, Daughter of Hippolyta, to make a tough moral choice.

Remain hidden in Amazon Safe Space and hope for the best, or step into the fray? No external problem and Wonder Woman can never exist.

[image error]Okay so maybe not exactly Thucydides. Plato and Napoleon Bonaparte get some credit, too.

A protagonist cannot become a hero/heroine without triumphing over a big problem, despite all we (as Author God) will throw at them. Once we know the problem, it’s far easier to have a sense of the ending.

If we’ve crafted the core problem in need of resolution, we should have a fairly solid idea how and where the story wraps up. Granted, we may not end our novel precisely the way we first envision, but that’s okay. A general idea is totally cool. When we begin writing our story, the ending we have only needs to be close enough for government work.

This loose boundary is what will fire up the muse for endings that are ‘surprising yet inevitable‘, as the great playwright David Mamet likes to say.

Surprising, Yet Inevitable

[image error]

I believe the greatest compliment any story can earn is the surprising yet inevitable ending. When we craft a story, ideally the reader will finish and say two things.

I never saw that coming and How did I NOT see that coming?

If we do a bit of work on the front end, and are vastly familiar with our core problem, then this offers us (writers) a myriad of ways to mess with the readers’ heads.

How? We know what they will expect. Why? Because (logically) we’d expect it, too. So, we don’t do THAT.

This is when the reader settles in for that smooth right turn he’d anticipated…and then we zing left across four lanes and take that weird left exit and U-Turn (for bonus smart@$$ points). Meanwhile, the reader screams and hangs on for life, simultaneously hating and loving us.

The reader is stunned, breathless, and maybe indignant.

Ah, but if he’d paid closer attention, he would’ve noticed we (the author) did put on our story blinker and it wasn’t signaling right

February 23, 2018

Problems: Great Dramatic Writing Draws Blood & Opens Psychic Wounds

[image error]

Problems are the essential ingredient for all stories. All forms of dramatic writing balance on the fulcrum of problems. The more problems, the better. Small problems, big problems, complicated problems, imagined problems, ignored problems all make the human heart beat faster.

Complication, quandaries, distress, doubt, obstacles and issues are all what make real life terrifying…and great stories captivating.

Face it, we humans are a morbid bunch. Most of us see flashing emergency lights on a slick highway, and what do we do? We slow down to see…while deep down desperately hoping we don’t see. We sit in a fancy restaurant and a woman throws a glass of red wine in her date’s face? Oh, we ALL pay attention.

[image error]

Screeching tires, glass breaking or even a spouse on the phone muttering Uh-oh and our chest cinches. We must know what’s going on. Humans require resolution in order to return to our ‘happy’ homeostasis, even if deep down we know that ‘resolution’ is a lie. Delusion is inherently human, and so is neurosis which is good news for writers.

Can you say ‘job security’? *wink wink*

Humans Wired for Drama

[image error]

If we take a moment to ponder people, it makes sense why problems make for excellent stories. First, all humans are wired for survival, thus any potential threat to survival makes us pay attention. We’re biologically designed to be egocentric. Thus survival is not a problem, it’s a given. It’s also why this conversation makes my left eye twitch:

Me: So what is your protagonist’s goal?

Writer: To survive.

Me: *face palm*

Survival is Not Story

Here’s the deal. We ALL have a goal to survive. If, at the end of the day, I am NOT DEAD? I consider that a pretty good day. My genetic desire to survive is why I don’t blow dry my hair in the shower, take up bear-baiting, or see how far I can drive backwards on a highway.

Survival isn’t interesting. Whatever threatens survival? That’s what’s interesting.

[image error]

Secondly, humans possess a deep compunction to assign order in a world brimming with chaos. Remember our first lesson, when we discussed cause and effect? Our desire for order is directly related to survival. If we believe A + B = C, then when A +B =Z, we’ll drive ourselves nuts to know why.

What changed? Did we do, say, think something differently? Does this deviation mean anything? Is it dangerous?

Every superstition ever imagined hinges on human desperation for order and control.

We won the game when I didn’t wash my underwear and lost when I wore clean ones. Dirty underwear=winning.

Thirdly, humans are innately selfish. This proclivity for selfishness makes us all psychically vulnerable. For instance, we develop neuroses of varying degrees of severity. Neuroses, fundamentally, are false beliefs regarding cause and effect.

I smiled at the clerk and she was extremely rude. So it is true. People don’t like me.

Or, the clerk caught her boyfriend in bed her mother minutes before heading to work and—in truth—we (the neurotic customer) have nothing to do with her bad attitude. Aside from being in the blast radius of the poor clerk’s Jerry Springer drama.

Chaos Abounds

[image error]

When we factor in that humans a) are wired to survive b) crave order and c) are innately selfish, it makes sense why we are a story species. Stories are what discharges that leftover psychic energy left over at the end of every day.

Life rarely makes perfect sense, but stories do. Reality has no set order, but stories do. Every day bad guys win, good people die, and ‘stuff’ happens for no apparent reason which freaks us out.

These are the main reasons why stories are the balm that eases our jagged thoughts and weary heart. In well-written stories, we might not like the outcome, but it makes sense. The play or movie might not set well, but there is integral order. In dramatic writing, even when the good guy loses, he still wins.

Life can’t say the same.

The point of any great dramatic writing isn’t some canned message or ‘good guy always wins’ soma, or even some thinly veiled morality tale/lecture/pontification. Drama—when boiled down to its essence—is to feed the innately illogical and selfish id what it desires.

Entertainment.

But not simply any entertainment. Entertainment that speaks to the primal realms of the mind and offers release. Enter in…PROBLEMS.

A Hero Must Decide

[image error]

Ever pay attention to the word ‘decide?’ De-cide. What other words end in ‘cide?’ Homicide, fratricide, sororcide, matricide, herbicide, pesticide, and y’all get the gist. Cide implies killing. Something, someone must die.

When we look to story, this is the point of a solid core story problem, because death is the ultimate objective. I know, I know. Missed my calling writing inspirational greeting cards, but bear with me.

In our last lesson, we unpacked my created literary term Big Boss Troublemaker, which is the BRAIN behind the core story problem in need of resolution. Strong BBTs make for stories that endure because IDEAS are impossible to completely destroy.

Like weeds of the human condition, we might eradicate a problem in one story but then POOF! It pops up again in another. Over and over, again and again.

[image error]

This is why there are no new stories, only new ways of telling the same stories. All human stories are about the same things: love, betrayal, greed, acceptance, etc. These are emotional touch-points that imbue story immortality.

Same but Different

This is why Shakespeare’s plays are as relevant today as they were a few hundred years ago. It’s precisely how Baz Luhrmann can take a story about two star-crossed lovers trapped between two feuding families and set it in modern-day Verona Beach…and our brains don’t explode.

We accept Leonardo DiCaprio and Claire Danes as Romeo and Juliet. We accept beach duels and gunfights, and John Leguizamo (Tybalt) spouting, ‘Peace? Peace. I hate the word, as I hate hell, all Montagues, and thee.’ We accept the Montagues and Capulets circa 1996 and oddly? We’re cool.

THIS makes perfect sense….

[image error]

And this…

[image error]

Not only does this make total sense, and speak to our souls…it is AWESOME. Romeo & Juliet is a play that is hundreds of years old, that tells a story we witness every single day. TODAY. We see these same dramas play out in our lives daily, whether in person, on-line or in the news.

The point of any story is the hero (heroine) has no choice but to de-CIDE. Ideas must die or victory is lost. Romeo and Juilet physically die in the end, but the IDEA that love can triumph over hate wins. Granted it’s a Pyhrric victory, but the IDEA that hate is more powerful—that might makes right—is ultimately defeated.

***It also proves Shakespeare’s sardonic point that romantic love leads to terminal stupidity, but that’s another post.

The Problem & Push

[image error]

In any good story there are at least two IDEAS at war, meaning lots and lots of problems. There is the BBT’s (opposition’s) central idea, which will inevitably collide with the protagonist’s central idea.

As we discussed last lesson, ideas are relayed via the corporeal and this happens by proxy.

The proxy has a plan that forces the protagonist out of the comfort zone, and eventually gives the MC no choice but evolution or extinction. It’s do or die, whether that is a physical death, a psychic death, or both.

DEATH is always on the line. Whether we are writing comedy or tragedy, genre fiction or literary this maxim is universally true.

The MC must change internally (the IDEA) as well as externally (behavior), since talk is cheap. Action is what matters, because action is belief made manifest.

Problems at Play

[image error]

Let’s use an example. Today, we’ll look at Zootopia. Sure, it’s a kid’s movie but a fabulous example how we don’t have to be writing Hamlet, There Will Be Blood, or Glenngarry Glenn Ross to write terrific drama with depth.

Judy Hopps is a bunny who dreams of going off and being a cop in Zootopia, a place where all animals coexist in perfect harmony and are not prejudged based off species or history.

Sure.

Zootopia (like all utopian ideals) is vastly different from the pretty picture, as Judy soon finds out when she enters the police academy. Then she gets an even harder dose of reality as a rookie cop. It is true—Zootopia is a wonder for sure—but it also has its fair share of prejudice, stereotyping, and mistrust.

The BBT is the IDEA that prejudice is inevitable and dangerous and there is only one option—eat or be eaten. Our proxy of this IDEA is the seemingly meekest and most helpless of all creatures—a sheep (Bellwether)—who’s the ‘hapless/spineless’ assistant to Mayor Lionheart (a lion, of course).

Bellwether doesn’t believe prejudice can ever be overcome, that all creatures will eventually resort to their baser natures. As a sheep, her kind have always been prey. Unless she uses her wits, she and her kind will remain perpetually in danger, a permanent menu ‘option.’

Granted, it’s a manufactured danger (neurosis), since predator and prey animals have managed to coexist in Zootopia without anyone being eaten for generations. Yet, her argument is compelling because her belief is grounded in authentic fear.

It is Bellwether’s perceived inevitable reversal that compels her to force ‘fate’s’ hand. She cannot endure the stress that she (and other prey animals) could be the daily special any day. Thus, she takes action to ensure prey animals are in control. TOTAL control.

Great Antagonists Actually Make a Good Point

[image error]

This is what separates deep, layered antagonists (and villains) from caricatures. When we open our minds and think from the opposition’s POV, they kinda make a good point…which is what messes with our heads.

***FYI—Id, being primal and freaky, totally digs mind games and is still unsure if Dr. Hannibal Lecter is a villain or anti-hero. Sure he eats people, but only the ones who kinda deserved it.

Moving on…

Bellwether devises a scheme to ‘prove’ predator animals cannot be trusted, and thus must be contained for obvious public safety reasons. By inflaming deeply held, but politely hidden, beliefs among the animals, she will have all the justification needed to oppress those considered a threat (predators).

In the beginning, Judy Hopps naively believes she’s devoid of prejudice, completely enlightened, and without fear. Predators are not a threat. They don’t view her and her kind as food, but as fellow citizens and friends. All that being hunted and eaten stuff is ancient history.

This is Judy’s IDEA and it cannot help but collide with Bellwether’s IDEA that prejudice is inevitable and dangerous.

[image error]

Desperation forces Judy to ally with a fox (historically known for enjoying rabbits as munchies) in order to solve the mystery. Predator animals really are going berserk, seemingly reverting back to their wild natures. Why?

Strong Protagonists Face Personal Extinction

Deep down, Judy believes the animals of Zootopia have evolved and can coexist (though is now facing escalating doubts). Problems bash Judy’s IDEA repeatedly, harder and harder.

A psychic sledgehammer slams into her beliefs, testing their actual strength. No matter what she does or tries, the evidence mounts that she’s delusional.

Everything she sees and experiences only seems to affirm predators are dangerous, cannot be trusted, and must be contained.

The core story PROBLEM—Why are all the predators suddenly going berserk?—gives Judy only two choices. She can give up or be brave and to take a hard honest look at herself.

Is she really as devoid of prejudice as she once believed? Really all that evolved, all that enlightened after all? Or deep down does she actually agree with Bellwether?

[image error]

In the beginning, Judy believed Zootopia was perfect, but by the end of Act 2? Judy doesn’t even know why she’s THERE. All her psychic wounds are open and bleeding.

Eventually the story problem forces Judy to de-CIDE. One idea must die. Either Zootopia dies or the notion that prejudice is inevitable and dangerous must die.

For that to happen, Judy Hopps must expose Bellwether’s true colors and stop her nefarious plan, or Zootopia implodes. The old ways return only the roles reversed (prey in control) and all progress goes up in flames.

À La Fin

[image error]

Both sides, antagonist and protagonist have their own unique IDEA. The story is the crucible that fires out the BS, and reveals truth. Problems batter both sides until one side finally wins. Just as a suggestion, in commercial fiction, it’s a sound plan for the protagonist (hero/heroine) to win. Otherwise it’s called a French film

February 21, 2018

Publishing Success: Genre Loyalty vs. Plot Bunny Saboteurs

Genre matters. Genre is the foundation for longevity, building a loyal fan base and also the key to unlocking all the other plot bunnies (other genres/story ideas) we’ve been dying to try out. Regardless of the publishing path we choose, genre focus is the game-changer that transitions us from published authors to powerhouse brands.

Hello, My Name is Cait and I am a Plot Bunny Addict

Yeah, we’ll get there in a minute.

By now, all of you should know that when you don’t hear from me (Cait) for a while, you should probably worry because I’m holed up in my study either doing research or coming up with new and creative ways to achieve world domination–though so far, I’ve had to rule out hallucinogenic peanut butter, karaoke, and podcasting.

[image error]Frighteningly enough, I looked very much like this as a baby. *shudders*

But, I’m back now, ready to start sharing with all of you the fruits of my research. I’ve been doing some deep digging into the state of the publishing industry, analyzing trends, and preparing to throw down some predictions.

***Punxsutawney Phil ain’t got nothin’ on me.

Today, we’re going to explore current publishing trends and the strategy of choosing a genre. At first glance, it seems pretty straightforward, right? We like to write X, so X will be our genre.

But then…along comes that plot bunny with its cute wiggly nose and cotton ball tail, begging us to take a little side trip into Y genre. It’s cool. We can do that because we can self-publish, right?

[image error]

Not So Fast

No more rules. Freedom! We’ve broken the oppressive shackles of traditional publishing in all areas, including the ridiculous way publishers used to limit writers to one specific genre. We are now free to be a seven-genre-crossing author if we want! Ha!

[image error]Yeah…it starts like this…

Well…sorta. Not quite. But kinda.

Let’s take a closer look.

In the beginning, BIG PUBLISHING said, ‘Let there be genres,’ and there were genres, and lo, the publisher saw that it was good.

Before Amazon glomped onto the scene with push-button publishing, authors actually had to pick a genre and stick with it….’til death did they part.

There were solid business reasons for this.

Books took a long time to write and even longer to publish, and this isn’t even accounting for the amount of money it took to produce a book and get it to market—pun intended. The agent then publisher invested a lot of time, thought, and care into helping the author choose a genre. This was imperative for crafting a brand—which is when a name alone has the power to drive sales.

Stephen King. Enough said.

The Downside of Genre Loyalty

While brand loyalty was great for book sales, it wasn’t always so easy on the authors. How many thrillers can one writer write before the thrill is gone? For the author and their readers. But, rules were rules and why mess with what worked?

Then indie…

[image error]

Back in the day, if we started writing historical romance…well, we pretty much kept writing more historical romance. Sure, there was some flexibility in the century we chose for our next book. But, it was a nigh-on-impossible quest to go from regency romance to noir crime thriller. Only a handful of already mega-successful authors really ever managed it well.

***Namely because rules don’t apply to them the same way as mere mortal authors.

The Big (Book) Bang

Enter the era of insta-hey-look-I-published-a-book. All the old rules (ostensibly) went out the window. Wanna go from cozy mystery to epic sword and sorcery? No problem! Just keep hitting that ‘Publish Your Book’ button. Who needed fans of the cozy mystery genre to discover our books in the urban fantasy genre?

Genre schmenre. Social media wizardry would magically lead fans to discover US.

[image error]

Sure, we might lose some people if we went a while (okay years) without publishing something in our audiences’ preferred genre. Maybe we’d see some drop off when we took that hard left from chick lit to shifter menage erotica. Perhaps our Amazon rankings even dropped below where we’re comfortable.

No biggie. It’s a phase. It will pass.

As long as we just keep hitting that ‘Publish Your Book’ button, we can publish whatever we want in any genre we want. Vive la revolution!

Yes…and, no.

Babies & Bathwater

Interestingly, what I’ve learned from years of working in publishing and studying how it works is that we might have let excitement cloud our vision. To be blunt, in our desire to be unchained from one genre forever…we went a tad cray-cray (actual business term), and threw the book baby out with the bathwater.

Now that the dust is settling in the publishing world, evidence suggest genre focus matters more than we might have realized.

[image error]

The truth is that we authors need to position ourselves flexibly but firmly between these two extremes. There is a point between Write six hundred spy thrillers until you DIE and Write ALL the genres and even MIX them!

Regardless of what new shiny the muse wants to explore, picking then sticking with a primary genre is the foundation for great brands, books, and business.

Self-Publishing

Counter to what many have touted, it turns out self-publishing is especially sensitive to genre consistency.

Over the past two years, there were a number of minor fads and trends that had authors jumping from epic fantasy to fairytale retellings, to urban fantasy all within the space of six months. On the one hand, authors developed some momentum in KENP pages read and attracted new fans.

However, in every competitive analysis I’ve done on authors who self-publish, those who started with a primary genre and stuck with it for 90% of their books over a 3-4 year period had the best book rankings, author rankings, social media followings, and Google name recognition.

And while I’m not privy to every single author’s sales numbers. Stupid restraining orders *rolls eyes*. I have been able to dig up enough data that permits me to make the following extrapolation:

Authors with a primary genre for 90% of their books over a 3-4 year period made the most money and had the consistently bestselling books.

This isn’t to say these authors don’t also publish in other genres, but they don’t spend the majority of their writing time, social media time, and marketing resources trying to establish their name and brand in multiple genres simultaneously. That is not a formula for success, more a formula for a nervous breakdown.

For these authors, evidence demonstrates that a successful presence in secondary genres develops more organically and over a longer period of time.

What’s the Takeaway?

[image error]

If our career goal is to be a hybrid author or even a purely legacy publishing track, then building in a primary genre becomes even more critical.

The Legacy Published Plan

Let’s start with traditional (legacy) publishing. Getting a book out with the Big 5 generally takes anywhere from 18-24 months. Most traditionally-published authors publish one book per year.

There’s a lot of time, a LOT of money, and a lot of resources invested in getting each book to market (as mentioned earlier). Thus, it makes sense for publishers to erect strong parameters around the the author’s brand. Focus is what generates traction, backlist, and a solid fan base with money to spend.

[image error]

Nowadays, there is a teeny tiny degree of flexibility that has crept into the legacy model, most likely in order to compete with Amazon’s yoga-esque genre fluidity. That’s how we get writers like Emma Donoghue who can bend from Victorian mystery to the contemporary masterpiece of psychological drama that is ‘Room.’

Yet, she is the exception, not the norm. In truth, only a fraction of a percentage of traditionally-published authors have been able to pull off this genre-inverted-triangle successfully.

All to say that, if we want to publish traditionally, we’d better really, REALLY love the genre we’re writing in, because that’s going to be home for a long, long time.

The Hybrid Author Plan

With a hybrid publishing model (some books self-published, some books through a traditional publisher), our approach will depend on whether we start out self-published or traditionally-published.

If we start out as self-published but with a goal to eventually enter into the traditional model, genre consistency becomes essential (even if our long-game is to change genres once we break into traditional publishing).

[image error]

There are major advantages for a writer who can demonstrate a solid track record of longevity and focus in a single genre. First, genre concentration tangibly demonstrates our ability to achieve long-term goals.

Secondly, by maintaining genre cohesion, this increases the odds we’ll build a vested fan base eager to BUY OUR future books. This makes our books a sound investment for agents/editors based off numbers (not hopes and luck).

Thirdly, genre focus is vital for building a strong author brand. Name recognition alone is useless and not a brand. Only a name that translates into an actual sale is a brand.

James Patterson—>Ka-Ching!

Weird Guy Who Book Spams Non-Stop—>Unfollow & BLOCK

Since legacy press is a business and not a non-profit, these three benefits can translate into (our) massive advantage when we’re seeking our own place in ‘the club.’

We need the club, but why does the club need us? That’s where we need to hustle.

If we’ve successfully stuck to a genre and created a strong fan base on our own, then traditional is the next logical business step to expand distribution for a product that is already successfully selling.

It is a win-win for author and publisher.

If we seek to change genres, it shows the publisher we can commit to the time and work it takes to build both the reputation and backlist required for success.

Again, win-win.

Expanding Genre ‘Horizons’

If we start out as traditionally-published and want to expand into self-publishing, there are several things to consider. First, we need to be very, very sure (as in, I-have-had-a-conversation-with-my-lawyer-agent-editor-sure) that we won’t be violating the terms of our publishing contract by putting out work in the same genre.

[image error]

Once we have the ‘all-clear’ to keep writing in the same genre, there’s a big adjustment ahead we need to take seriously. First there is the frequency of publication required to compete effectively in self-publishing. Can we write at a pulp fiction speed and maintain quality?

***Often this is the impetus for legacy authors to also write indie. They long to produce at a far faster pace than the legacy model can accommodate.

Also, there’s the question of financial resources required to achieve parity between traditional and self-published books. Cover design, proofing, editing, formatting, etc. Fans have come to expect a certain quality and we better be able to meet or even exceed anything we published via legacy.

No easy task.

On the upside, our fan base should already be somewhat established, so YAY! We can just keep growing and growing…

Stretching Our Genre Wings

In another scenario, we may choose to expand into self-publishing because we’d like to try other genres, especially ones that might not necessarily jive with an already-established fan base.

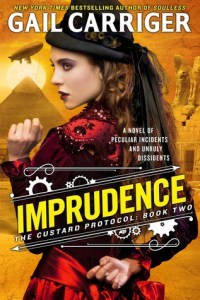

Steampunk fantasy author Gail Carriger is an excellent example of this (as well as being one of my favorite writers). She has a firmly established seventeen-book steampunk genre backlist of traditionally-published books.

Gail chose to self-publish because she wanted to release shorter and more frequent works in her same steampunk universe (with special dispensation from her publisher).

Eventually, she started publishing works in the contemporary urban fantasy genre with an LGBTQ focus.

Carriger continues to publish both her traditional steampunk and is now consistently building her presence in this new genre. Because she approached her writing career with strategy, her brand has not only maintained integrity, but it is also steadily expanding.

The Plot Bunny Nursery

Also known as the TBW (to-be-written) pile.

At the end of the day, what does all of this mean for all of us writers along the publication continuum?

This is the question I asked myself one day in January as I looked at my writing and marketing plans for 2018. It’s a fact that I don’t so much have a plot bunny nursery as I do a crack house for wayward hares.

[image error]

I’m seriously all over the place in terms of my ideas. I have plot bunnies in steampunk, YA mythology, fairytales, historical romance, contemporary psychological thriller, shifter romance. While all my story ideas might be wonderful, I know it’s unwise to try to pursue them all simultaneously.

Strategy matters. This means, I know which bunnies get adopted first. The others can wait (and likely breed).

I confess. My brain bounces from genre to genre like a kangaroo in a bouncy castle. Yours might, too. That’s okay. We can write all the books!

Eventually.

If we publish with planning and intention regarding genre, we’re more likely to reap far better reward. The evidence doesn’t lie. Authors who’ve performed the best—whether traditional, hybrid, or self-published—are the ones who’ve done three things:

Written really great books.

Picked a genre and remained focused on it for at least three years.

Published consistently.

This is where the professional discipline that Kristen talks about really has to kick in. Sometimes, little bunnies have to just chill (drug them if you must). We can’t always do what’s fun and shiny and new. To make it in this highly competitive market, we have make a plan, then stick with the plan, even when it gets boring, or hard, or seems to be getting us nowhere.

[image error]

Jumping genres non-stop isn’t the cure for sagging sales and rankings. Writing and publishing great books in a focused genre, then building from there is. So keep calm, stay focused, and the bunnies will be just fine.

Promise

February 16, 2018

The Brain Behind the Story: The Big Boss Troublemaker (BBT)

[image error]

Last post in our structure series, I introduced the core antagonist, what I call the Big Boss Troublemaker. The BBT is our central opposition. This is the force responsible for creating the core story problem in need of resolution. While stories have all sorts of ‘antagonists’ we’ll get to them another time.

In fact, buckle up because this is Master’s Class material.

Today’s post is advanced content, since we’re going to explore the BBT far more deeply than ever before. I’ve blogged on the BBT before with a simpler explication. But, after 1,200 or so blogs, even I need a good challenge.

One of my goals this year is to offer far more demanding content and accelerated lessons. There are plenty of Writing 101 blogs catering to new writers. Hey, I’ve written a few hundred, myself.

Problem is, not all writers are brand new and even those who might be just starting out? It’ll be good for you to stretch your synapses and give the gray matter a hardcore workout. The Internet has plenty of ‘pink weight’ craft blogs and I don’t care to add any more. Namely because I know you guys are wicked smart and dying to be truly punished.

I meant pushed. Yes, pushed.

Here we go…

The CORE (IDEA)

[image error]

The BBT is a wholly unique sort of antagonist. This specific antagonist, the BBT, is the BRAIN (mastermind) of all great stories. Why? Because all great stories involve an IDEA that must be defeated.

How do we do this?

Great stories are almost like living creatures. Like all living creatures, there are critical limitations when it comes to structure. What this means is not all ‘components’ are equally necessary for an organism to be considered ‘alive.’

If a kitten is born with no hair? We call it a Sphynx then sell it for big bucks to people who adore cats that resemble space aliens.

If our kitten is born with unusable back legs, it’s sad. But, we humans get creative and craft a Lego ‘kitten wheelchair’…producing a kitten now drunk with power. ZOOOOOOM! LOOK AT HIM GO ALL THE PLACES!

Ah, but a kitten born with no brain stem? Little to do but mourn. We can’t work around this missing ‘organ,’ no matter how much we may want to. Regardless how creative we get, actual life requires a brain that directs every other system.

The Living Story