Jai Arjun Singh's Blog, page 56

November 19, 2015

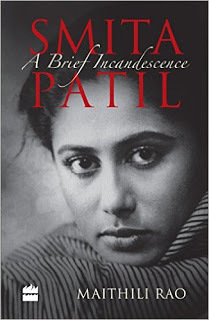

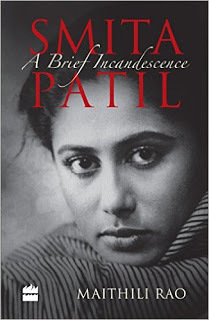

"The magic of Smita-ness" - a book about Smita Patil

[Did a version of this review for Open magazine]

One of the most cutting things a reviewer can say about a personality-centred book is that it is hagiographical; that the author has chosen veneration over discernment. This charge is sometimes a little unfair though (and I may be saying this from a position of defensiveness, having just written a book about a film personality myself). It is one thing for a book to be deceitful or compromised – perhaps because it is an authorized, controlled biography, or because the writer has a hidden agenda – but when the foundation stones are honesty and seriousness of intent, why should someone writing about a favourite person be obliged to maintain a discreet distance? After all, the best reason to write a book is that you are driven to write it – passionate about the subject, more willing to devote years of your life to it than most other fans would be. Surely a truthful expression of that passion is preferable to sap-headed “objectivity”.

Which brings me to Maithili Rao’s intense, deeply felt tribute

Smita Patil

, whose subtitle “A Brief Incandescence” is not just an apt description of Patil’s much-too-short life and how brightly she shone in the time given to her, but may also prepare you for the sometimes florid writing in these pages.

Which brings me to Maithili Rao’s intense, deeply felt tribute

Smita Patil

, whose subtitle “A Brief Incandescence” is not just an apt description of Patil’s much-too-short life and how brightly she shone in the time given to her, but may also prepare you for the sometimes florid writing in these pages.

Rao’s feelings are clear from the opening lines: “She was Indian cinema’s Everywoman. Her genius shone through in rendering the everywoman extraordinaire with a signature hypnotic allure, a depth charged with intensity that exploded into emotions on celluloid, grand and subtle, dramatic and nuanced all at once”. Some might think this effusive enough for one page, but a few lines down you find, among other descriptions, “haunting presence”, “finely sculpted face”, “wilful and generous mouth”, “voice vibrating with emotion”, “proud carriage of a born fighter”, "infinite inflections", "girlish trills of gaiety", and “tensile strength of steel balanced with the suppleness of a reed”.

I list these partly to caution those of you who get put off by this sort of prose, but also to tell the more open-minded among you to persevere regardless – because there are many good things in this book if you are interested in Patil and the cinema that she was such a vital part of. Speaking for myself, mild annoyance with some of the overwriting and the repeated descriptions of Patil’s bone structure gave way to a growing respect for the author’s Smita-adoration and a willingness to be swept along by it.

This isn’t a conventional biography, Rao says in her introduction. She does provide basic background information about the Pune girl who went to Mumbai in her teens, became a Marathi newsreader for Doordarshan in the early 1970s and then found her way into cinema (and into the moment of the Indian New Wave) via Arun Khopkar’s diploma short Teevra Madhyam, but the bulk of the book looks at Patil’s key films, their sociological impact, what her presence added to them, and the reservoirs in her personality that informed her performances. Through her own analyses and the observations of those who had known Patil, she dissects her strengths as a performer: stillness, intensity, instinct – the last of those being particularly important for someone who, unlike most of her peers, had never been to the FTII or studied acting formally.

This isn’t a conventional biography, Rao says in her introduction. She does provide basic background information about the Pune girl who went to Mumbai in her teens, became a Marathi newsreader for Doordarshan in the early 1970s and then found her way into cinema (and into the moment of the Indian New Wave) via Arun Khopkar’s diploma short Teevra Madhyam, but the bulk of the book looks at Patil’s key films, their sociological impact, what her presence added to them, and the reservoirs in her personality that informed her performances. Through her own analyses and the observations of those who had known Patil, she dissects her strengths as a performer: stillness, intensity, instinct – the last of those being particularly important for someone who, unlike most of her peers, had never been to the FTII or studied acting formally.

Rao’s assertions that “there are more peaks [of great performances] in Smita’s extraordinary career than any comparable figure of that time”, or that she was “indubitably the pole star of parallel cinema”, are debatable – but they form the basis of the book’s longest chapter, “Smita Patil and her Dasavatars”, in which she closely examines such films as Shyam Benegal’s Bhumika and Manthan, Jabbar Patel’s Jait re Jait and Umbartha, Mahesh Bhatt’s Arth and Mrinal Sen’s Akaler Sandhane; the two chapters that follow deal with other movies, ranging from Ketan Mehta’s superb Bhavni Bhavai to Sagar Sarhadi’s clunker Haadsa. Around this point she also rips into the many low-grade mainstream films that Patil chose to do. The little boy in me, who had loved B Subhash’s Dance Dance when it came out, bristled a little at Rao’s dismissal of it, but then ceded her points. (Even at age 10, I think I had understood that the long-suffering sister and wife Smita played in that film was a cipher, her fate little more than a pretext for Mithun to flex both muscles and angst, and for Shakti Kapoor to make an uncharacteristic sacrifice in the climax.) Happily, she does also acknowledge some of Patil’s more notable mainstream work such as JP Dutta’s epic Ghulami, a film that might have been pitch perfect if Dharmendra had been 15 years younger when it was made. (He and Smita are cast as childhood friends!)

Though I haven’t followed Patil’s career anywhere near as closely as Rao has, and even when I didn’t remember details of all the films discussed here, there is much in these analyses to chew on and appreciate, or – as a professional nitpicker – to disagree with. For instance, the 1974 Charandas Chor is very far from “a minor film”, in my view – it deserves to be rediscovered as a jewel of the New Wave, one of our best theatre-to-film adaptations, and a view of Benegal and his cinematographer Govind Nihalani working near full steam; personally I rate it above Nishant, which Rao spends many pages discussing. That said, Nishant is a more important Smita Patil film, and a starting point in her soon-to-be celebrated rivalry with Shabana Azmi.

Though I haven’t followed Patil’s career anywhere near as closely as Rao has, and even when I didn’t remember details of all the films discussed here, there is much in these analyses to chew on and appreciate, or – as a professional nitpicker – to disagree with. For instance, the 1974 Charandas Chor is very far from “a minor film”, in my view – it deserves to be rediscovered as a jewel of the New Wave, one of our best theatre-to-film adaptations, and a view of Benegal and his cinematographer Govind Nihalani working near full steam; personally I rate it above Nishant, which Rao spends many pages discussing. That said, Nishant is a more important Smita Patil film, and a starting point in her soon-to-be celebrated rivalry with Shabana Azmi.

I also enjoyed the close readings of specific scenes, such as the controversial bathing sequence from Rabindra Dharmraj’s Chakra, which has been both celebrated as unflinchingly realistic and derided as “poverty porn”; as Rao points out, the truth probably lies somewhere in between. Speaking as a male, I should say here that I found Patil genuinely sexy in that scene, and I would have trouble with any reading that strictly compartmentalized it as “frank but not titillating”. Its effect can vary depending on who is looking at it and in what context. And it should be possible to make two opposing suggestions: that the director’s intentions may have been questionable, but that Patil still found a way, through the deploying of confident, assertive sexuality, to keep the balance of power tilted in her favour. As she often did in other situations, in other films.

I also enjoyed the close readings of specific scenes, such as the controversial bathing sequence from Rabindra Dharmraj’s Chakra, which has been both celebrated as unflinchingly realistic and derided as “poverty porn”; as Rao points out, the truth probably lies somewhere in between. Speaking as a male, I should say here that I found Patil genuinely sexy in that scene, and I would have trouble with any reading that strictly compartmentalized it as “frank but not titillating”. Its effect can vary depending on who is looking at it and in what context. And it should be possible to make two opposing suggestions: that the director’s intentions may have been questionable, but that Patil still found a way, through the deploying of confident, assertive sexuality, to keep the balance of power tilted in her favour. As she often did in other situations, in other films.

*****

There is a raw, breathless urgency in much of Rao's writing. The prose is conversational and informal at times (“Smita had no prudish issues”) to the extent that she even uses half-sentences at times, or lapses into the present tense while describing an aspect of Patil’s personality (“There is an intriguing contrary streak in Smita”). At other times she slips into scholar mode and into the language of academia, as if by habit. Between the two extremes, I usually preferred the former mode, which provides a firsthand sense of how personal all this is to her.

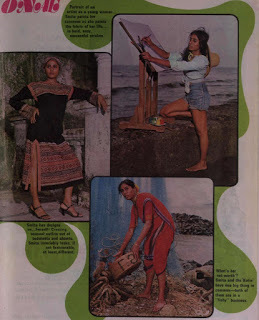

Though she discusses such character traits as Patil’s bohemian directness and generosity of spirit, and her relationships with her sister Anita and with friends, Rao is discreet about some things. She doesn’t spend much time on Patil’s controversial relationship with the married Raj Babbar, because she never got to speak firsthand with either of them and didn’t want to rely on hearsay and speculation. There are anecdotes about other aspects of Patil’s life though, such as the one about her draping handloom sarees over her jeans before going on air as a newsreader. And generously, she shares her stage with other Smita fans near the end of the book: there are short, heartfelt pieces by writer Deepa Deosthalee and theatre actor Vaishali Chakravarty, reminders of how thoroughly movie stars can imprint themselves on our lives.

But coming back to those Dasavatars, and to Rao’s thesis that they outshine – in quantity and quality – the heights attained by most other actresses. “I would personally place her above [Nargis and Meena Kumari] because she was untouched by film-industry baggage of stereotypes, expectations and practiced feminine airs and graces they were asked to adopt,” she writes. Actually, I think this same assertion could be used to make exactly the opposite case; skilled actors who operate mostly in the idiom of commercial cinema can face serious challenges in locating truth within an often-synthetic framework.

In any case it is hard to make such comparative assessments given that most of Patil’s best work was done by age thirty. With more time, there may have been more peaks – but it is equally likely that there may have been a rapid decline, a larger proportion of bad choices, and a consequent paring down of her reputation. The “what if” question is inescapable.

And perhaps this is why the story in Rao’s book that I thought most poignant was the one about a letter Smita wrote to director Saeed Mirza after they made Albert Pinto ko Gussa Kyon Aata Hai? together. How deeply do you believe in your political ideology and how long will you adhere to it, she asked. There was no apparent context for this question, but there is an urgency to it, a possible lament for the ephemeral nature of all things: principles, strong emotions, life itself. In another anecdote involving Amitabh Bachchan and his Coolie accident, Rao implies that Smita had a sixth sense. Could she have had a premonition of her own fate, and about the future arcs of her colleagues, many of whom were once associated purely with a cinema of integrity but who learned a few things about compromise over the years? Looking at the young woman with the soulful eyes on this book’s cover, one is tempted to say yes.

And perhaps this is why the story in Rao’s book that I thought most poignant was the one about a letter Smita wrote to director Saeed Mirza after they made Albert Pinto ko Gussa Kyon Aata Hai? together. How deeply do you believe in your political ideology and how long will you adhere to it, she asked. There was no apparent context for this question, but there is an urgency to it, a possible lament for the ephemeral nature of all things: principles, strong emotions, life itself. In another anecdote involving Amitabh Bachchan and his Coolie accident, Rao implies that Smita had a sixth sense. Could she have had a premonition of her own fate, and about the future arcs of her colleagues, many of whom were once associated purely with a cinema of integrity but who learned a few things about compromise over the years? Looking at the young woman with the soulful eyes on this book’s cover, one is tempted to say yes.

[Some posts about other notable biographies of actors who died young: Lois Banner on Marilyn Monroe; Vinod Mehta on Meena Kumari]

One of the most cutting things a reviewer can say about a personality-centred book is that it is hagiographical; that the author has chosen veneration over discernment. This charge is sometimes a little unfair though (and I may be saying this from a position of defensiveness, having just written a book about a film personality myself). It is one thing for a book to be deceitful or compromised – perhaps because it is an authorized, controlled biography, or because the writer has a hidden agenda – but when the foundation stones are honesty and seriousness of intent, why should someone writing about a favourite person be obliged to maintain a discreet distance? After all, the best reason to write a book is that you are driven to write it – passionate about the subject, more willing to devote years of your life to it than most other fans would be. Surely a truthful expression of that passion is preferable to sap-headed “objectivity”.

Which brings me to Maithili Rao’s intense, deeply felt tribute

Smita Patil

, whose subtitle “A Brief Incandescence” is not just an apt description of Patil’s much-too-short life and how brightly she shone in the time given to her, but may also prepare you for the sometimes florid writing in these pages.

Which brings me to Maithili Rao’s intense, deeply felt tribute

Smita Patil

, whose subtitle “A Brief Incandescence” is not just an apt description of Patil’s much-too-short life and how brightly she shone in the time given to her, but may also prepare you for the sometimes florid writing in these pages.Rao’s feelings are clear from the opening lines: “She was Indian cinema’s Everywoman. Her genius shone through in rendering the everywoman extraordinaire with a signature hypnotic allure, a depth charged with intensity that exploded into emotions on celluloid, grand and subtle, dramatic and nuanced all at once”. Some might think this effusive enough for one page, but a few lines down you find, among other descriptions, “haunting presence”, “finely sculpted face”, “wilful and generous mouth”, “voice vibrating with emotion”, “proud carriage of a born fighter”, "infinite inflections", "girlish trills of gaiety", and “tensile strength of steel balanced with the suppleness of a reed”.

I list these partly to caution those of you who get put off by this sort of prose, but also to tell the more open-minded among you to persevere regardless – because there are many good things in this book if you are interested in Patil and the cinema that she was such a vital part of. Speaking for myself, mild annoyance with some of the overwriting and the repeated descriptions of Patil’s bone structure gave way to a growing respect for the author’s Smita-adoration and a willingness to be swept along by it.

This isn’t a conventional biography, Rao says in her introduction. She does provide basic background information about the Pune girl who went to Mumbai in her teens, became a Marathi newsreader for Doordarshan in the early 1970s and then found her way into cinema (and into the moment of the Indian New Wave) via Arun Khopkar’s diploma short Teevra Madhyam, but the bulk of the book looks at Patil’s key films, their sociological impact, what her presence added to them, and the reservoirs in her personality that informed her performances. Through her own analyses and the observations of those who had known Patil, she dissects her strengths as a performer: stillness, intensity, instinct – the last of those being particularly important for someone who, unlike most of her peers, had never been to the FTII or studied acting formally.

This isn’t a conventional biography, Rao says in her introduction. She does provide basic background information about the Pune girl who went to Mumbai in her teens, became a Marathi newsreader for Doordarshan in the early 1970s and then found her way into cinema (and into the moment of the Indian New Wave) via Arun Khopkar’s diploma short Teevra Madhyam, but the bulk of the book looks at Patil’s key films, their sociological impact, what her presence added to them, and the reservoirs in her personality that informed her performances. Through her own analyses and the observations of those who had known Patil, she dissects her strengths as a performer: stillness, intensity, instinct – the last of those being particularly important for someone who, unlike most of her peers, had never been to the FTII or studied acting formally.Rao’s assertions that “there are more peaks [of great performances] in Smita’s extraordinary career than any comparable figure of that time”, or that she was “indubitably the pole star of parallel cinema”, are debatable – but they form the basis of the book’s longest chapter, “Smita Patil and her Dasavatars”, in which she closely examines such films as Shyam Benegal’s Bhumika and Manthan, Jabbar Patel’s Jait re Jait and Umbartha, Mahesh Bhatt’s Arth and Mrinal Sen’s Akaler Sandhane; the two chapters that follow deal with other movies, ranging from Ketan Mehta’s superb Bhavni Bhavai to Sagar Sarhadi’s clunker Haadsa. Around this point she also rips into the many low-grade mainstream films that Patil chose to do. The little boy in me, who had loved B Subhash’s Dance Dance when it came out, bristled a little at Rao’s dismissal of it, but then ceded her points. (Even at age 10, I think I had understood that the long-suffering sister and wife Smita played in that film was a cipher, her fate little more than a pretext for Mithun to flex both muscles and angst, and for Shakti Kapoor to make an uncharacteristic sacrifice in the climax.) Happily, she does also acknowledge some of Patil’s more notable mainstream work such as JP Dutta’s epic Ghulami, a film that might have been pitch perfect if Dharmendra had been 15 years younger when it was made. (He and Smita are cast as childhood friends!)

Though I haven’t followed Patil’s career anywhere near as closely as Rao has, and even when I didn’t remember details of all the films discussed here, there is much in these analyses to chew on and appreciate, or – as a professional nitpicker – to disagree with. For instance, the 1974 Charandas Chor is very far from “a minor film”, in my view – it deserves to be rediscovered as a jewel of the New Wave, one of our best theatre-to-film adaptations, and a view of Benegal and his cinematographer Govind Nihalani working near full steam; personally I rate it above Nishant, which Rao spends many pages discussing. That said, Nishant is a more important Smita Patil film, and a starting point in her soon-to-be celebrated rivalry with Shabana Azmi.

Though I haven’t followed Patil’s career anywhere near as closely as Rao has, and even when I didn’t remember details of all the films discussed here, there is much in these analyses to chew on and appreciate, or – as a professional nitpicker – to disagree with. For instance, the 1974 Charandas Chor is very far from “a minor film”, in my view – it deserves to be rediscovered as a jewel of the New Wave, one of our best theatre-to-film adaptations, and a view of Benegal and his cinematographer Govind Nihalani working near full steam; personally I rate it above Nishant, which Rao spends many pages discussing. That said, Nishant is a more important Smita Patil film, and a starting point in her soon-to-be celebrated rivalry with Shabana Azmi. I also enjoyed the close readings of specific scenes, such as the controversial bathing sequence from Rabindra Dharmraj’s Chakra, which has been both celebrated as unflinchingly realistic and derided as “poverty porn”; as Rao points out, the truth probably lies somewhere in between. Speaking as a male, I should say here that I found Patil genuinely sexy in that scene, and I would have trouble with any reading that strictly compartmentalized it as “frank but not titillating”. Its effect can vary depending on who is looking at it and in what context. And it should be possible to make two opposing suggestions: that the director’s intentions may have been questionable, but that Patil still found a way, through the deploying of confident, assertive sexuality, to keep the balance of power tilted in her favour. As she often did in other situations, in other films.

I also enjoyed the close readings of specific scenes, such as the controversial bathing sequence from Rabindra Dharmraj’s Chakra, which has been both celebrated as unflinchingly realistic and derided as “poverty porn”; as Rao points out, the truth probably lies somewhere in between. Speaking as a male, I should say here that I found Patil genuinely sexy in that scene, and I would have trouble with any reading that strictly compartmentalized it as “frank but not titillating”. Its effect can vary depending on who is looking at it and in what context. And it should be possible to make two opposing suggestions: that the director’s intentions may have been questionable, but that Patil still found a way, through the deploying of confident, assertive sexuality, to keep the balance of power tilted in her favour. As she often did in other situations, in other films. *****

There is a raw, breathless urgency in much of Rao's writing. The prose is conversational and informal at times (“Smita had no prudish issues”) to the extent that she even uses half-sentences at times, or lapses into the present tense while describing an aspect of Patil’s personality (“There is an intriguing contrary streak in Smita”). At other times she slips into scholar mode and into the language of academia, as if by habit. Between the two extremes, I usually preferred the former mode, which provides a firsthand sense of how personal all this is to her.

Though she discusses such character traits as Patil’s bohemian directness and generosity of spirit, and her relationships with her sister Anita and with friends, Rao is discreet about some things. She doesn’t spend much time on Patil’s controversial relationship with the married Raj Babbar, because she never got to speak firsthand with either of them and didn’t want to rely on hearsay and speculation. There are anecdotes about other aspects of Patil’s life though, such as the one about her draping handloom sarees over her jeans before going on air as a newsreader. And generously, she shares her stage with other Smita fans near the end of the book: there are short, heartfelt pieces by writer Deepa Deosthalee and theatre actor Vaishali Chakravarty, reminders of how thoroughly movie stars can imprint themselves on our lives.

But coming back to those Dasavatars, and to Rao’s thesis that they outshine – in quantity and quality – the heights attained by most other actresses. “I would personally place her above [Nargis and Meena Kumari] because she was untouched by film-industry baggage of stereotypes, expectations and practiced feminine airs and graces they were asked to adopt,” she writes. Actually, I think this same assertion could be used to make exactly the opposite case; skilled actors who operate mostly in the idiom of commercial cinema can face serious challenges in locating truth within an often-synthetic framework.

In any case it is hard to make such comparative assessments given that most of Patil’s best work was done by age thirty. With more time, there may have been more peaks – but it is equally likely that there may have been a rapid decline, a larger proportion of bad choices, and a consequent paring down of her reputation. The “what if” question is inescapable.

And perhaps this is why the story in Rao’s book that I thought most poignant was the one about a letter Smita wrote to director Saeed Mirza after they made Albert Pinto ko Gussa Kyon Aata Hai? together. How deeply do you believe in your political ideology and how long will you adhere to it, she asked. There was no apparent context for this question, but there is an urgency to it, a possible lament for the ephemeral nature of all things: principles, strong emotions, life itself. In another anecdote involving Amitabh Bachchan and his Coolie accident, Rao implies that Smita had a sixth sense. Could she have had a premonition of her own fate, and about the future arcs of her colleagues, many of whom were once associated purely with a cinema of integrity but who learned a few things about compromise over the years? Looking at the young woman with the soulful eyes on this book’s cover, one is tempted to say yes.

And perhaps this is why the story in Rao’s book that I thought most poignant was the one about a letter Smita wrote to director Saeed Mirza after they made Albert Pinto ko Gussa Kyon Aata Hai? together. How deeply do you believe in your political ideology and how long will you adhere to it, she asked. There was no apparent context for this question, but there is an urgency to it, a possible lament for the ephemeral nature of all things: principles, strong emotions, life itself. In another anecdote involving Amitabh Bachchan and his Coolie accident, Rao implies that Smita had a sixth sense. Could she have had a premonition of her own fate, and about the future arcs of her colleagues, many of whom were once associated purely with a cinema of integrity but who learned a few things about compromise over the years? Looking at the young woman with the soulful eyes on this book’s cover, one is tempted to say yes.[Some posts about other notable biographies of actors who died young: Lois Banner on Marilyn Monroe; Vinod Mehta on Meena Kumari]

Published on November 19, 2015 19:33

November 14, 2015

On movie servants, then and now

[Did this piece for The Indian Express]

The recent film Talvar has often been described as an objective presentation of competing scenarios in the Aarushi Talwar murder case, but this is a bit misleading: the narrative that the film most clearly endorses is the one uncovered by CDI officer Ashwin (Irrfan Khan) about a drinking binge that got out of hand in the servants’ quarters. The scenes recreating this scenario would have sent a chill through many middle-class viewers, given the familiarity of the domestic arrangements and the potential danger contained in them: a lower-class man unrelated to the family, living in quarters within the flat; the blitheness, or blindness, of his employers, who barely registered him as a sentient presence and didn’t realise he might have friends over late at night; the possibility that these men might set their sights on the “baby” of the house.

But calling Talvar alarmist — a caution about a clash of cultures, a warning to the genteel “us” about the grubby “them” — would be too simple. Because in that same narrative, the main servant Khempal (a stand-in for the real-life Hemraj who worked for the Talwars) is depicted as a benevolent, avuncular man who does everything he can to protect the young girl (“Meri beti jaisi hai”). In that sense, Khempal isn’t so removed from a familiar archetype of the Hindi-movie servant, one that all of us can picture when we remember movies of the 1970s. It’s another thing that the Raghu chachas and Ramu kakas of a bygone time, ancient retainers, doddering about with their dusting rags, would never be seen in the vicinity of a bottle of rum or whisky.

Or wouldn’t they?

In Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s 1975 Mili, the tortured Shekhar (Amitabh Bachchan) shifts from one apartment to another, elderly manservant Gopi in tow, to escape his past; but since he finds no peace of mind, there is plenty of liquor-guzzling, and naturally Gopi is the one who brings out the flasks and bottles. The relationship between the two is sharply observed: Shekhar’s angry outbursts might be cringe-inducing, were it not for the fact that the old man gives back as good as he gets — while also serving as Shekhar’s protector against the intrusion of other people in the building. They are almost like squabbling spouses.

In Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s 1975 Mili, the tortured Shekhar (Amitabh Bachchan) shifts from one apartment to another, elderly manservant Gopi in tow, to escape his past; but since he finds no peace of mind, there is plenty of liquor-guzzling, and naturally Gopi is the one who brings out the flasks and bottles. The relationship between the two is sharply observed: Shekhar’s angry outbursts might be cringe-inducing, were it not for the fact that the old man gives back as good as he gets — while also serving as Shekhar’s protector against the intrusion of other people in the building. They are almost like squabbling spouses.

The more typical family retainer in films of the time was the genial, subservient old man in a joint-family setting — the one who would pick the children up from school, and generally keep the home fires burning. You could be sure of his decorum-ensuring presence — polishing some knickknack or other in the background, waiting for bitiya’s instructions to bring chai, if an unmarried boy and girl happened to meet at one of their homes with no other family member present. For all we know, he was born with that dusting cloth attached to his shoulder. And our broad memories of those scenes lend heft to the idea that such films (particularly the Middle Cinema, represented by the work of Mukherjee, Basu Chatterji and Gulzar) were “innocent” and of a “simpler” time: that such servants belonged to the Old India of clearly defined class roles, where such a person wasn’t expected to transcend the circumstances of his birth; that the New India of the past 20 years is a more egalitarian (therefore, more precarious) place where the lower-class man of the household might be a Laxmikant Berde on buddy-buddy terms with rich kid Salman Khan.

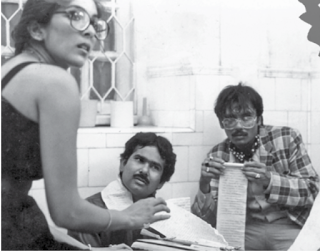

There is something to this view, but it can create a simplistic Then vs Now binary, while failing to recognise that things haven’t changed all that radically in our society, and that many of those old films were sharper than you think. Consider the celebrated character actor AK Hangal, who in the popular imagination is more associated with the generic family servant than any other actor is. In Basu Bhattacharya’s 1971 Anubhav, Hangal’s character operates well outside the cliché. In his mildly salacious opening scene, he comments wryly on current lifestyles, while apparently massaging Sanjeev Kumar’s buttocks. It’s two in the morning and Kumar’s character — a newspaper editor — is in bed, proofing reports. “Mujhe toh lagta hai ke aap logon ki duniya hee kuch ulti-pulti hai (God intended us to work during the day and sleep at night and here you are doing the opposite thing),” the old servant says with a disapproving head-shake. Later, he is a sounding board for the restless lady of the house, played by Tanuja; when he calls her “bahu”, this alienated child of the modern world feels like she belongs.

There is something to this view, but it can create a simplistic Then vs Now binary, while failing to recognise that things haven’t changed all that radically in our society, and that many of those old films were sharper than you think. Consider the celebrated character actor AK Hangal, who in the popular imagination is more associated with the generic family servant than any other actor is. In Basu Bhattacharya’s 1971 Anubhav, Hangal’s character operates well outside the cliché. In his mildly salacious opening scene, he comments wryly on current lifestyles, while apparently massaging Sanjeev Kumar’s buttocks. It’s two in the morning and Kumar’s character — a newspaper editor — is in bed, proofing reports. “Mujhe toh lagta hai ke aap logon ki duniya hee kuch ulti-pulti hai (God intended us to work during the day and sleep at night and here you are doing the opposite thing),” the old servant says with a disapproving head-shake. Later, he is a sounding board for the restless lady of the house, played by Tanuja; when he calls her “bahu”, this alienated child of the modern world feels like she belongs.

Anubhav was a formally experimental film — especially in its naturalistic sound design, overlapping dialogue and handheld-camera shots — that belonged more to the New Wave of the period than to narrative filmmaking. But even in films that looked much more conventional, sly things were done with the class divide and with the role of a servant as someone who could be a sutradhaar, a life-changer, a fount of wisdom or even a God-figure simply by virtue of being around all the time, managing the small but important things (it isn’t just chance that so many of these characters were named Raghu or Vishnu or Ram).

In a movie as frothy as Mukherjee’s Chupke Chupke, for instance, role-play is employed to show what might happen when class lines get blurred and a society’s safety nets fall away. “Driver insaan nahin hota?” asks Sulekha (Sharmila Tagore) when accused of getting a little too cosy with the family chauffeur; the fact that the “driver” is really Sulekha’s husband in disguise doesn’t nullify the larger resonance of this question, or the quiet, unshowy subversiveness of the film. (In another funny but pointed scene, a businessman looks directly at his childhood buddy but doesn’t recognise him, because the latter is wearing a driver’s uniform.) Meanwhile, the servant-as-bhagwaan idea had its clearest realisation in Bawarchi, where the title character, played by Rajesh Khanna, is strongly associated with the god Krishna: he emerges from a beautiful, misty setting (Vrindavan) and heads straight towards a house divided (Hastinapura) to set things right; in one dream sequence, he even plays saarthi or moral guide to the confused child of the house.

Meanwhile, the servant-as-bhagwaan idea had its clearest realisation in Bawarchi, where the title character, played by Rajesh Khanna, is strongly associated with the god Krishna: he emerges from a beautiful, misty setting (Vrindavan) and heads straight towards a house divided (Hastinapura) to set things right; in one dream sequence, he even plays saarthi or moral guide to the confused child of the house.

Hindi-movie servants didn’t have a good time of it in the 1980s, when they were usually embedded in a slapstick comedy track that ran alongside the main one; it is hard to say what social commentary may be found in all those scenes where Shakti Kapoor ran around in striped pajamas with his naara (drawstring) hanging out, or in the Johnny-Lever-channelling-Jerry-Lewis interludes. And later, in the world of the post-liberalisation “multiplex film”, people from what was once designated the Servant Class either became invisible — no joint families, no retainers — or were now the protagonists of stories about quick social climbing (or wanting desperately to climb), from Dibakar Banerjee’s Oye Lucky! Lucky Oye! to Kanu Bahl’s Titli.

But even as our cinema becomes self-consciously progressive, breaking away from its past traditions, there is still space — even in urban stories — for the honest, well-written depiction of the old-school servant. One of this year’s best films, Shoojit Sircar’s Piku , has the cantankerous Bhaskor Banerjee (Amitabh Bachchan) in a love-hate relationship with his household help Bhudan. In a nod to Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s cinema, Bhaskor was named after the character Bachchan had played in Anand 45 years earlier. But his scenes with Bhudan may remind you of the Shekhar and Gopi of another Mukherjee film, jousting with each other across class lines, affection and impatience running hand in hand.

--------------------------------------------

[My book The World of Hrishikesh Mukherjee has a few more reflections on the class divide in films like Chupke Chupke, Aashirwad, Anari and Gol Maal]

The recent film Talvar has often been described as an objective presentation of competing scenarios in the Aarushi Talwar murder case, but this is a bit misleading: the narrative that the film most clearly endorses is the one uncovered by CDI officer Ashwin (Irrfan Khan) about a drinking binge that got out of hand in the servants’ quarters. The scenes recreating this scenario would have sent a chill through many middle-class viewers, given the familiarity of the domestic arrangements and the potential danger contained in them: a lower-class man unrelated to the family, living in quarters within the flat; the blitheness, or blindness, of his employers, who barely registered him as a sentient presence and didn’t realise he might have friends over late at night; the possibility that these men might set their sights on the “baby” of the house.

But calling Talvar alarmist — a caution about a clash of cultures, a warning to the genteel “us” about the grubby “them” — would be too simple. Because in that same narrative, the main servant Khempal (a stand-in for the real-life Hemraj who worked for the Talwars) is depicted as a benevolent, avuncular man who does everything he can to protect the young girl (“Meri beti jaisi hai”). In that sense, Khempal isn’t so removed from a familiar archetype of the Hindi-movie servant, one that all of us can picture when we remember movies of the 1970s. It’s another thing that the Raghu chachas and Ramu kakas of a bygone time, ancient retainers, doddering about with their dusting rags, would never be seen in the vicinity of a bottle of rum or whisky.

Or wouldn’t they?

In Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s 1975 Mili, the tortured Shekhar (Amitabh Bachchan) shifts from one apartment to another, elderly manservant Gopi in tow, to escape his past; but since he finds no peace of mind, there is plenty of liquor-guzzling, and naturally Gopi is the one who brings out the flasks and bottles. The relationship between the two is sharply observed: Shekhar’s angry outbursts might be cringe-inducing, were it not for the fact that the old man gives back as good as he gets — while also serving as Shekhar’s protector against the intrusion of other people in the building. They are almost like squabbling spouses.

In Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s 1975 Mili, the tortured Shekhar (Amitabh Bachchan) shifts from one apartment to another, elderly manservant Gopi in tow, to escape his past; but since he finds no peace of mind, there is plenty of liquor-guzzling, and naturally Gopi is the one who brings out the flasks and bottles. The relationship between the two is sharply observed: Shekhar’s angry outbursts might be cringe-inducing, were it not for the fact that the old man gives back as good as he gets — while also serving as Shekhar’s protector against the intrusion of other people in the building. They are almost like squabbling spouses.The more typical family retainer in films of the time was the genial, subservient old man in a joint-family setting — the one who would pick the children up from school, and generally keep the home fires burning. You could be sure of his decorum-ensuring presence — polishing some knickknack or other in the background, waiting for bitiya’s instructions to bring chai, if an unmarried boy and girl happened to meet at one of their homes with no other family member present. For all we know, he was born with that dusting cloth attached to his shoulder. And our broad memories of those scenes lend heft to the idea that such films (particularly the Middle Cinema, represented by the work of Mukherjee, Basu Chatterji and Gulzar) were “innocent” and of a “simpler” time: that such servants belonged to the Old India of clearly defined class roles, where such a person wasn’t expected to transcend the circumstances of his birth; that the New India of the past 20 years is a more egalitarian (therefore, more precarious) place where the lower-class man of the household might be a Laxmikant Berde on buddy-buddy terms with rich kid Salman Khan.

There is something to this view, but it can create a simplistic Then vs Now binary, while failing to recognise that things haven’t changed all that radically in our society, and that many of those old films were sharper than you think. Consider the celebrated character actor AK Hangal, who in the popular imagination is more associated with the generic family servant than any other actor is. In Basu Bhattacharya’s 1971 Anubhav, Hangal’s character operates well outside the cliché. In his mildly salacious opening scene, he comments wryly on current lifestyles, while apparently massaging Sanjeev Kumar’s buttocks. It’s two in the morning and Kumar’s character — a newspaper editor — is in bed, proofing reports. “Mujhe toh lagta hai ke aap logon ki duniya hee kuch ulti-pulti hai (God intended us to work during the day and sleep at night and here you are doing the opposite thing),” the old servant says with a disapproving head-shake. Later, he is a sounding board for the restless lady of the house, played by Tanuja; when he calls her “bahu”, this alienated child of the modern world feels like she belongs.

There is something to this view, but it can create a simplistic Then vs Now binary, while failing to recognise that things haven’t changed all that radically in our society, and that many of those old films were sharper than you think. Consider the celebrated character actor AK Hangal, who in the popular imagination is more associated with the generic family servant than any other actor is. In Basu Bhattacharya’s 1971 Anubhav, Hangal’s character operates well outside the cliché. In his mildly salacious opening scene, he comments wryly on current lifestyles, while apparently massaging Sanjeev Kumar’s buttocks. It’s two in the morning and Kumar’s character — a newspaper editor — is in bed, proofing reports. “Mujhe toh lagta hai ke aap logon ki duniya hee kuch ulti-pulti hai (God intended us to work during the day and sleep at night and here you are doing the opposite thing),” the old servant says with a disapproving head-shake. Later, he is a sounding board for the restless lady of the house, played by Tanuja; when he calls her “bahu”, this alienated child of the modern world feels like she belongs.Anubhav was a formally experimental film — especially in its naturalistic sound design, overlapping dialogue and handheld-camera shots — that belonged more to the New Wave of the period than to narrative filmmaking. But even in films that looked much more conventional, sly things were done with the class divide and with the role of a servant as someone who could be a sutradhaar, a life-changer, a fount of wisdom or even a God-figure simply by virtue of being around all the time, managing the small but important things (it isn’t just chance that so many of these characters were named Raghu or Vishnu or Ram).

In a movie as frothy as Mukherjee’s Chupke Chupke, for instance, role-play is employed to show what might happen when class lines get blurred and a society’s safety nets fall away. “Driver insaan nahin hota?” asks Sulekha (Sharmila Tagore) when accused of getting a little too cosy with the family chauffeur; the fact that the “driver” is really Sulekha’s husband in disguise doesn’t nullify the larger resonance of this question, or the quiet, unshowy subversiveness of the film. (In another funny but pointed scene, a businessman looks directly at his childhood buddy but doesn’t recognise him, because the latter is wearing a driver’s uniform.)

Meanwhile, the servant-as-bhagwaan idea had its clearest realisation in Bawarchi, where the title character, played by Rajesh Khanna, is strongly associated with the god Krishna: he emerges from a beautiful, misty setting (Vrindavan) and heads straight towards a house divided (Hastinapura) to set things right; in one dream sequence, he even plays saarthi or moral guide to the confused child of the house.

Meanwhile, the servant-as-bhagwaan idea had its clearest realisation in Bawarchi, where the title character, played by Rajesh Khanna, is strongly associated with the god Krishna: he emerges from a beautiful, misty setting (Vrindavan) and heads straight towards a house divided (Hastinapura) to set things right; in one dream sequence, he even plays saarthi or moral guide to the confused child of the house. Hindi-movie servants didn’t have a good time of it in the 1980s, when they were usually embedded in a slapstick comedy track that ran alongside the main one; it is hard to say what social commentary may be found in all those scenes where Shakti Kapoor ran around in striped pajamas with his naara (drawstring) hanging out, or in the Johnny-Lever-channelling-Jerry-Lewis interludes. And later, in the world of the post-liberalisation “multiplex film”, people from what was once designated the Servant Class either became invisible — no joint families, no retainers — or were now the protagonists of stories about quick social climbing (or wanting desperately to climb), from Dibakar Banerjee’s Oye Lucky! Lucky Oye! to Kanu Bahl’s Titli.

But even as our cinema becomes self-consciously progressive, breaking away from its past traditions, there is still space — even in urban stories — for the honest, well-written depiction of the old-school servant. One of this year’s best films, Shoojit Sircar’s Piku , has the cantankerous Bhaskor Banerjee (Amitabh Bachchan) in a love-hate relationship with his household help Bhudan. In a nod to Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s cinema, Bhaskor was named after the character Bachchan had played in Anand 45 years earlier. But his scenes with Bhudan may remind you of the Shekhar and Gopi of another Mukherjee film, jousting with each other across class lines, affection and impatience running hand in hand.

--------------------------------------------

[My book The World of Hrishikesh Mukherjee has a few more reflections on the class divide in films like Chupke Chupke, Aashirwad, Anari and Gol Maal]

Published on November 14, 2015 09:59

November 9, 2015

Charles and his doubles

[My latest Mint Lounge column]

“He was everything larger than life that I had expected him to be (sic),” the actor Randeep Hooda said in an interview to a daily paper, “He was so full of life, almost virile. He is such a handsome man. Even at age 72, his aura is fully intact.”

By the time this gush-fest ends, the reader may have lost sight of the fact that the big incandescent blob of charisma being talked about – and the man Hooda plays in the new film Main aur Charles – is the serial killer Charles Sobhraj, who has spent over 30 years in jail (in separate stints) for his crimes.

But no, I’m being unfair to Hooda. An actor doesn’t have the luxury of being judgemental: he has to try and understand – even, to whatever degree possible, empathise with – the character he is playing. And Hooda is very good in Main aur Charles. The true scope of his performance and presence is felt gradually, as the film itself – directed with flair by Prawaal Raman, and wonderfully shot, often in dark shadowy settings, by Anuj Rakesh Dhawan – goes from being a disjointed (and puzzling) collection of vignettes to one where the narrative comes together more fully.

But no, I’m being unfair to Hooda. An actor doesn’t have the luxury of being judgemental: he has to try and understand – even, to whatever degree possible, empathise with – the character he is playing. And Hooda is very good in Main aur Charles. The true scope of his performance and presence is felt gradually, as the film itself – directed with flair by Prawaal Raman, and wonderfully shot, often in dark shadowy settings, by Anuj Rakesh Dhawan – goes from being a disjointed (and puzzling) collection of vignettes to one where the narrative comes together more fully.

The real-life Sobhraj was a charmer, and this was integral to his success at doing the things he did; it’s unreasonable to expect a film to present him as unattractive just to make a moral point. (Whether it should go as far as putting the tagline “Worth Dying For” on the poster is another debate!) Speaking more generally though, film history is dotted with magnetic villains, and with the accompanying question: is it okay to make evil seem seductive?

The answer appears clearer in some cases than in others. When Adolf Hitler is depicted in godlike terms – descending from the clouds to greet his people and lead Germany to glory – in the 1935 documentary Triumph of the Will, it is relatively easy to say (with hindsight) that Leni Riefenstahl’s film was irresponsible, or even wicked. We wince at those images and turn for succor to films that threw a banana peel under the thick boots of fascism: the comical sight of Hitler as a megalomaniac playing with a balloon globe in The Great Dictator (1940), or the opening scene of To Be or Not to Be (1942), with the Fuhrer apparently window-shopping at a Warsaw market (and being gawked at in turn by spectators). And yet, even for a Triumph of the Will, there can be a counterview: what we are being shown is what the dispirited, messiah-starved German citizen of the time saw; in that sense, the film is being truthful to a specific perspective.

At other times, even when a bad-guy film has its heart in the right place, the casting may introduce a dimension that was not intended. In 1968, Tony Curtis played the notorious killer Albert DeSalvo in The Boston Strangler (a film that has minor structural similarities with Main aur Charles). He was deglamorized for the part, and it was a daring performance – but that didn’t completely take away from the fact that here was a Hollywood golden boy, a matinee idol who used to be associated with swashbucklers and romances. To a Curtis fan, might DeSalvo become easy to relate to on some level?

The dashing, blank-slate villain has quite a fan-following too. Anyone who has read Patricia Highsmith’s Tom Ripley novels will see that Sobhraj – at least as depicted in Main aur Charles – is a cousin to Highsmith’s amoral anti-hero, who slips from one personality to another as he prepares his crimes. (Unsurprisingly, Ripley has had some gripping cinematic avatars, from Alain Delon in the 1960 Plein Soleil to Dennis Hopper in The American Friend and Matt Damon in The Talented Mr Ripley.) In fact, thinking about Charles and Ripley, I realised that the “Main” (me) in the simple-seeming title Main aur Charles doesn’t have to be police commissioner Amod Kanth (Adil Hussain), who is Charles’s nemesis and the story’s po-faced moral centre; the “me” could just as easily be a second, hidden Charles. At one point he is shown fake passports bearing his photographs and assumed names, and asked: which of these people are you? “All of them,” he replies tersely. But is there a real person beneath the disguises, or only one final blank mask?

The dashing, blank-slate villain has quite a fan-following too. Anyone who has read Patricia Highsmith’s Tom Ripley novels will see that Sobhraj – at least as depicted in Main aur Charles – is a cousin to Highsmith’s amoral anti-hero, who slips from one personality to another as he prepares his crimes. (Unsurprisingly, Ripley has had some gripping cinematic avatars, from Alain Delon in the 1960 Plein Soleil to Dennis Hopper in The American Friend and Matt Damon in The Talented Mr Ripley.) In fact, thinking about Charles and Ripley, I realised that the “Main” (me) in the simple-seeming title Main aur Charles doesn’t have to be police commissioner Amod Kanth (Adil Hussain), who is Charles’s nemesis and the story’s po-faced moral centre; the “me” could just as easily be a second, hidden Charles. At one point he is shown fake passports bearing his photographs and assumed names, and asked: which of these people are you? “All of them,” he replies tersely. But is there a real person beneath the disguises, or only one final blank mask?

Which brings us to the doppelganger theme, with its view of good and evil as inextricable sides of the same coin. In recent popular culture, the idea has been iconised in some of the darker comics about the Batman-Joker relationship (see Alan Moore’s brilliant Batman: The Killing Joke, with its closing yarn about two lunatics trying to escape an asylum together) and you’ll also find it in the relationship between gentleman cannibal Hannibal Lecter and his pursuer Will Graham. “The reason you caught me is that we are just alike,” says Lecter to the spooked Will in the 1986 film Manhunter, a theme that has been more fully developed in the ongoing TV series Hannibal.

In fact, the title of Raman’s film reminded me of the two Charlies in one of the best doppelganger movies I have seen, Alfred Hitchcock’s 1943 Shadow of a Doubt: in one corner is the lady-killer (in both senses of the term) Uncle Charlie, in the other is his adoring small-town niece, who was named after him. Often linked together visually by the film, they have a near-telepathic connection – the difference being that the younger Charlie is uncorrupted, while the older one is a murderer and a nihilist.

In fact, the title of Raman’s film reminded me of the two Charlies in one of the best doppelganger movies I have seen, Alfred Hitchcock’s 1943 Shadow of a Doubt: in one corner is the lady-killer (in both senses of the term) Uncle Charlie, in the other is his adoring small-town niece, who was named after him. Often linked together visually by the film, they have a near-telepathic connection – the difference being that the younger Charlie is uncorrupted, while the older one is a murderer and a nihilist.

In the end he is tossed off a train; good triumphs over evil. But it isn’t that simple either. We are left with a clear sense that the once-innocent world of the younger Charlie has been forever altered. It’s a bit like the spooky scene in Main aur Charles where Amod Kanth’s wife, having become intrigued by the Charles story, tells her husband “He was involved with dozens of women, and you can’t even handle me alone?” and the otherwise straight-arrow cop looks at her and bursts into a convulsion of laughter, his eyes gleaming like those of the man he is pursuing to the ends of the earth.

“He was everything larger than life that I had expected him to be (sic),” the actor Randeep Hooda said in an interview to a daily paper, “He was so full of life, almost virile. He is such a handsome man. Even at age 72, his aura is fully intact.”

By the time this gush-fest ends, the reader may have lost sight of the fact that the big incandescent blob of charisma being talked about – and the man Hooda plays in the new film Main aur Charles – is the serial killer Charles Sobhraj, who has spent over 30 years in jail (in separate stints) for his crimes.

But no, I’m being unfair to Hooda. An actor doesn’t have the luxury of being judgemental: he has to try and understand – even, to whatever degree possible, empathise with – the character he is playing. And Hooda is very good in Main aur Charles. The true scope of his performance and presence is felt gradually, as the film itself – directed with flair by Prawaal Raman, and wonderfully shot, often in dark shadowy settings, by Anuj Rakesh Dhawan – goes from being a disjointed (and puzzling) collection of vignettes to one where the narrative comes together more fully.

But no, I’m being unfair to Hooda. An actor doesn’t have the luxury of being judgemental: he has to try and understand – even, to whatever degree possible, empathise with – the character he is playing. And Hooda is very good in Main aur Charles. The true scope of his performance and presence is felt gradually, as the film itself – directed with flair by Prawaal Raman, and wonderfully shot, often in dark shadowy settings, by Anuj Rakesh Dhawan – goes from being a disjointed (and puzzling) collection of vignettes to one where the narrative comes together more fully. The real-life Sobhraj was a charmer, and this was integral to his success at doing the things he did; it’s unreasonable to expect a film to present him as unattractive just to make a moral point. (Whether it should go as far as putting the tagline “Worth Dying For” on the poster is another debate!) Speaking more generally though, film history is dotted with magnetic villains, and with the accompanying question: is it okay to make evil seem seductive?

The answer appears clearer in some cases than in others. When Adolf Hitler is depicted in godlike terms – descending from the clouds to greet his people and lead Germany to glory – in the 1935 documentary Triumph of the Will, it is relatively easy to say (with hindsight) that Leni Riefenstahl’s film was irresponsible, or even wicked. We wince at those images and turn for succor to films that threw a banana peel under the thick boots of fascism: the comical sight of Hitler as a megalomaniac playing with a balloon globe in The Great Dictator (1940), or the opening scene of To Be or Not to Be (1942), with the Fuhrer apparently window-shopping at a Warsaw market (and being gawked at in turn by spectators). And yet, even for a Triumph of the Will, there can be a counterview: what we are being shown is what the dispirited, messiah-starved German citizen of the time saw; in that sense, the film is being truthful to a specific perspective.

At other times, even when a bad-guy film has its heart in the right place, the casting may introduce a dimension that was not intended. In 1968, Tony Curtis played the notorious killer Albert DeSalvo in The Boston Strangler (a film that has minor structural similarities with Main aur Charles). He was deglamorized for the part, and it was a daring performance – but that didn’t completely take away from the fact that here was a Hollywood golden boy, a matinee idol who used to be associated with swashbucklers and romances. To a Curtis fan, might DeSalvo become easy to relate to on some level?

The dashing, blank-slate villain has quite a fan-following too. Anyone who has read Patricia Highsmith’s Tom Ripley novels will see that Sobhraj – at least as depicted in Main aur Charles – is a cousin to Highsmith’s amoral anti-hero, who slips from one personality to another as he prepares his crimes. (Unsurprisingly, Ripley has had some gripping cinematic avatars, from Alain Delon in the 1960 Plein Soleil to Dennis Hopper in The American Friend and Matt Damon in The Talented Mr Ripley.) In fact, thinking about Charles and Ripley, I realised that the “Main” (me) in the simple-seeming title Main aur Charles doesn’t have to be police commissioner Amod Kanth (Adil Hussain), who is Charles’s nemesis and the story’s po-faced moral centre; the “me” could just as easily be a second, hidden Charles. At one point he is shown fake passports bearing his photographs and assumed names, and asked: which of these people are you? “All of them,” he replies tersely. But is there a real person beneath the disguises, or only one final blank mask?

The dashing, blank-slate villain has quite a fan-following too. Anyone who has read Patricia Highsmith’s Tom Ripley novels will see that Sobhraj – at least as depicted in Main aur Charles – is a cousin to Highsmith’s amoral anti-hero, who slips from one personality to another as he prepares his crimes. (Unsurprisingly, Ripley has had some gripping cinematic avatars, from Alain Delon in the 1960 Plein Soleil to Dennis Hopper in The American Friend and Matt Damon in The Talented Mr Ripley.) In fact, thinking about Charles and Ripley, I realised that the “Main” (me) in the simple-seeming title Main aur Charles doesn’t have to be police commissioner Amod Kanth (Adil Hussain), who is Charles’s nemesis and the story’s po-faced moral centre; the “me” could just as easily be a second, hidden Charles. At one point he is shown fake passports bearing his photographs and assumed names, and asked: which of these people are you? “All of them,” he replies tersely. But is there a real person beneath the disguises, or only one final blank mask?Which brings us to the doppelganger theme, with its view of good and evil as inextricable sides of the same coin. In recent popular culture, the idea has been iconised in some of the darker comics about the Batman-Joker relationship (see Alan Moore’s brilliant Batman: The Killing Joke, with its closing yarn about two lunatics trying to escape an asylum together) and you’ll also find it in the relationship between gentleman cannibal Hannibal Lecter and his pursuer Will Graham. “The reason you caught me is that we are just alike,” says Lecter to the spooked Will in the 1986 film Manhunter, a theme that has been more fully developed in the ongoing TV series Hannibal.

In fact, the title of Raman’s film reminded me of the two Charlies in one of the best doppelganger movies I have seen, Alfred Hitchcock’s 1943 Shadow of a Doubt: in one corner is the lady-killer (in both senses of the term) Uncle Charlie, in the other is his adoring small-town niece, who was named after him. Often linked together visually by the film, they have a near-telepathic connection – the difference being that the younger Charlie is uncorrupted, while the older one is a murderer and a nihilist.

In fact, the title of Raman’s film reminded me of the two Charlies in one of the best doppelganger movies I have seen, Alfred Hitchcock’s 1943 Shadow of a Doubt: in one corner is the lady-killer (in both senses of the term) Uncle Charlie, in the other is his adoring small-town niece, who was named after him. Often linked together visually by the film, they have a near-telepathic connection – the difference being that the younger Charlie is uncorrupted, while the older one is a murderer and a nihilist.In the end he is tossed off a train; good triumphs over evil. But it isn’t that simple either. We are left with a clear sense that the once-innocent world of the younger Charlie has been forever altered. It’s a bit like the spooky scene in Main aur Charles where Amod Kanth’s wife, having become intrigued by the Charles story, tells her husband “He was involved with dozens of women, and you can’t even handle me alone?” and the otherwise straight-arrow cop looks at her and bursts into a convulsion of laughter, his eyes gleaming like those of the man he is pursuing to the ends of the earth.

Published on November 09, 2015 03:21

November 6, 2015

Charles and his doubles

My latest Mint Lounge column uses the stylish new film about Charles Sobhraj, Main aur Charles, to look at questions around the depiction of evil onscreen. Here is the link. (Will put the piece up here in a few days.)

My latest Mint Lounge column uses the stylish new film about Charles Sobhraj, Main aur Charles, to look at questions around the depiction of evil onscreen. Here is the link. (Will put the piece up here in a few days.)

Published on November 06, 2015 18:52

October 26, 2015

Lit-fests! (A virtual one, and a reminder about Chandigarh)

It was fun to participate in LitFestX, an online literature festival where all I was required to do was sit at home and talk to my computer. Here's the video (the image is fuzzy, and I rambled a little more than I should have - the things I wrote about Chupke Chupke in the book probably make more sense than what I say here - but take a look anyway):

(Other video sessions from the fest can be viewed on this page - quite a variety of subjects and speakers.)

Also: another reminder about this year's edition of the Chandigarh Literature Festival (November 5-8), with its many scrumptious sessions that have critics in conversation with authors about specific books (or in conversation with filmmakers about specific films). The updated schedule for the fest is here, so please mark your calendars. Free entry, cosy venue, lots of talented writers and filmmakers: Kiran Nagarkar, Nayantara Sahgal, Gulzar, Jeet Thayil, Ananya Vajpeyi, Tarannum Riyaz, Shivmurti, Arundhathi Subramaniam, Sudeep Sen, Dilip Padgaonkar, Rahul Bhattacharya, Neeraj Ghaywan and Varun Grover, Navdeep Singh, Avinash Arun, Sriram Raghavan... and that's just a short list of participants.

As the dreaded lit-fest season draws near, I am reminded again of how nice it is to have a festival like this, with its many focused sessions where the participants know exactly what they are talking about. That might sound like the sort of thing ANY lit-fest is supposed to ensure, but you'd be surprised. Among many unsavoury experiences in the past, I was once asked to moderate a session where the subject of the discussion was completely unclear, and the organisers told me "It'll be fine - these are experienced writers, each of them will be happy to talk about their work, and all you have to do is prod them." Talk about cattle farms.

And the other day I was told - not asked, just told - that I would be moderating a session for a young author whom I hadn't even heard of, and not to worry, the organisers would send me his book "soon". (This was for a festival that I had already said yes to a few months ago, because they were putting me on a cinema session. May have to reconsider now.)

(Other video sessions from the fest can be viewed on this page - quite a variety of subjects and speakers.)

Also: another reminder about this year's edition of the Chandigarh Literature Festival (November 5-8), with its many scrumptious sessions that have critics in conversation with authors about specific books (or in conversation with filmmakers about specific films). The updated schedule for the fest is here, so please mark your calendars. Free entry, cosy venue, lots of talented writers and filmmakers: Kiran Nagarkar, Nayantara Sahgal, Gulzar, Jeet Thayil, Ananya Vajpeyi, Tarannum Riyaz, Shivmurti, Arundhathi Subramaniam, Sudeep Sen, Dilip Padgaonkar, Rahul Bhattacharya, Neeraj Ghaywan and Varun Grover, Navdeep Singh, Avinash Arun, Sriram Raghavan... and that's just a short list of participants.

As the dreaded lit-fest season draws near, I am reminded again of how nice it is to have a festival like this, with its many focused sessions where the participants know exactly what they are talking about. That might sound like the sort of thing ANY lit-fest is supposed to ensure, but you'd be surprised. Among many unsavoury experiences in the past, I was once asked to moderate a session where the subject of the discussion was completely unclear, and the organisers told me "It'll be fine - these are experienced writers, each of them will be happy to talk about their work, and all you have to do is prod them." Talk about cattle farms.

And the other day I was told - not asked, just told - that I would be moderating a session for a young author whom I hadn't even heard of, and not to worry, the organisers would send me his book "soon". (This was for a festival that I had already said yes to a few months ago, because they were putting me on a cinema session. May have to reconsider now.)

Published on October 26, 2015 18:03

Reviewing the reviewer: a part-response to Khalid Mohamed's piece

There have been some nice, flattering reviews of the Hrishikesh Mukherjee book recently, such as the ones by Jerry Pinto in The Indian Express (this was a special thrill) and by Gautam Chintamani in Mail Today, but the most entertaining one by far is this relentlessly negative one by Khalid Mohamed. Read and enjoy.

I suppose I should be glad that he took the trouble to go through the book closely. I also know full well that when an author responds to a negative review, he is automatically in a disadvantageous position: open to charges of being thin-skinned, petulant and so on. But since I am, first and foremost, a critic myself - and very invested in the basic tenets and disciplines of criticism - I won’t let this pass without making a few observations on strictly factual points:

1) “The thesis advanced by Jai Arjun Singh is that the master filmmaker was amazingly simple and honey-sweet.”

Nope. Not even close. I have repeatedly pointed to the complexities, contradictions and insecurities that one finds in Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s interviews and statements, and the glimpses one gets of inner demons - in his attitude to his own work and his much less than “honey-sweet” feelings about the state of the world. And “simple”, “innocent” and “honey-sweet” are words I have always found a bit problematic as descriptors of his cinema as well.

2) "In any case, why pull down Shakti Samanta and Asit Sen?”

Which... I haven’t done. (Though I personally find HM’s work more stimulating than theirs.) All I said was that those directors seemed more comfortable with the tropes of the emotional social film and with melodrama than Hrishi-da was. (And I don’t use "melodrama" as a pejorative.)

3) Now this bit is magnificently reductive:"For Singh, the airplane ending transporting Mili and the man she loves to a doctor in Switzerland suggests that her 'beemari is nothing more than the fact that she is single, that she hasn’t been completed yet by having a man in her life. No wonder the film ends with the hope that she might be cured.’ In other words, being single means being incomplete. And that’s not all. It’s suggested that the flight to the Alps could well morph into a honeymoon.”

I was being ironical in that passage - raising a hypothetical reading in order to refute it - and the very next line after the bit quoted by Mohamed is “Do I REALLY see the film in those terms? No.”

4) Referring to a couple of places where I have quoted from his old reviews of Hrishi-da’s films, Mohamed writes:

"I don’t have any quarrel with being quoted, even if it’s without the basic courtesy of being consulted.”

Basic courtesy? Really? You wrote something, it’s in the public domain now, and it’s fair game for any subsequent writer to quote from it as long as he provides the right attribution and doesn’t misquote or present something misleadingly out of context. (You know, the way Mohamed misrepresented my remarks on Mili above. Now THAT would be a problem.)

More than that, though, I’m amused at how Mohamed seems to think I have designated him a “strident beastie”, whatever that might be. I won’t offer an elaborate defence here, but anyone who’s interested: just go to the book’s Index, locate the two Khalid Mohamed references, take a look at what I have said on those pages, and then judge for yourselves.

For the record, and I have said this to friends often: I actually have high regard for some of the writing Mohamed did in the 1970s and 80s, at least whatever little I have encountered in magazines and archives. His 1983 review of Jaane bhi do Yaaro, for instance, was so sharp. Those fine old pieces make for a very worrying contrast with his output of the past 15 or so years (just one sample of which is here), and I think his career arc as a writer is a good caution to any talented young writer/critic who may be in danger of getting complacent or lazy or pompous over time.

P.S. the Bawarchi-Texas Chainsaw Massacre reference is from a passage that very specifically sets itself up as a farcical/April Fool-ish joke. Also: if a woman "falls at a man's feet" in a particular scene in a film, no, that does not automatically make the film itself regressive (though many critics, even today, seem to think it does); it could simply be a honest depiction of what a certain person from a certain milieu might do in a certain situation. A filmmaker's responsibility is to be truthful to his story and his characters, not to be "progressive" in a ham-handed way. But I’ll stop here...

I suppose I should be glad that he took the trouble to go through the book closely. I also know full well that when an author responds to a negative review, he is automatically in a disadvantageous position: open to charges of being thin-skinned, petulant and so on. But since I am, first and foremost, a critic myself - and very invested in the basic tenets and disciplines of criticism - I won’t let this pass without making a few observations on strictly factual points:

1) “The thesis advanced by Jai Arjun Singh is that the master filmmaker was amazingly simple and honey-sweet.”

Nope. Not even close. I have repeatedly pointed to the complexities, contradictions and insecurities that one finds in Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s interviews and statements, and the glimpses one gets of inner demons - in his attitude to his own work and his much less than “honey-sweet” feelings about the state of the world. And “simple”, “innocent” and “honey-sweet” are words I have always found a bit problematic as descriptors of his cinema as well.

2) "In any case, why pull down Shakti Samanta and Asit Sen?”

Which... I haven’t done. (Though I personally find HM’s work more stimulating than theirs.) All I said was that those directors seemed more comfortable with the tropes of the emotional social film and with melodrama than Hrishi-da was. (And I don’t use "melodrama" as a pejorative.)

3) Now this bit is magnificently reductive:"For Singh, the airplane ending transporting Mili and the man she loves to a doctor in Switzerland suggests that her 'beemari is nothing more than the fact that she is single, that she hasn’t been completed yet by having a man in her life. No wonder the film ends with the hope that she might be cured.’ In other words, being single means being incomplete. And that’s not all. It’s suggested that the flight to the Alps could well morph into a honeymoon.”

I was being ironical in that passage - raising a hypothetical reading in order to refute it - and the very next line after the bit quoted by Mohamed is “Do I REALLY see the film in those terms? No.”

4) Referring to a couple of places where I have quoted from his old reviews of Hrishi-da’s films, Mohamed writes:

"I don’t have any quarrel with being quoted, even if it’s without the basic courtesy of being consulted.”

Basic courtesy? Really? You wrote something, it’s in the public domain now, and it’s fair game for any subsequent writer to quote from it as long as he provides the right attribution and doesn’t misquote or present something misleadingly out of context. (You know, the way Mohamed misrepresented my remarks on Mili above. Now THAT would be a problem.)

More than that, though, I’m amused at how Mohamed seems to think I have designated him a “strident beastie”, whatever that might be. I won’t offer an elaborate defence here, but anyone who’s interested: just go to the book’s Index, locate the two Khalid Mohamed references, take a look at what I have said on those pages, and then judge for yourselves.

For the record, and I have said this to friends often: I actually have high regard for some of the writing Mohamed did in the 1970s and 80s, at least whatever little I have encountered in magazines and archives. His 1983 review of Jaane bhi do Yaaro, for instance, was so sharp. Those fine old pieces make for a very worrying contrast with his output of the past 15 or so years (just one sample of which is here), and I think his career arc as a writer is a good caution to any talented young writer/critic who may be in danger of getting complacent or lazy or pompous over time.

P.S. the Bawarchi-Texas Chainsaw Massacre reference is from a passage that very specifically sets itself up as a farcical/April Fool-ish joke. Also: if a woman "falls at a man's feet" in a particular scene in a film, no, that does not automatically make the film itself regressive (though many critics, even today, seem to think it does); it could simply be a honest depiction of what a certain person from a certain milieu might do in a certain situation. A filmmaker's responsibility is to be truthful to his story and his characters, not to be "progressive" in a ham-handed way. But I’ll stop here...

Published on October 26, 2015 06:54

October 23, 2015

In defence of Vikas Bahl's delightfully zany Shaandaar

[Did this review for Mint Lounge]

It may be an understatement to say that Vikas Bahl’s madcap new film Shaandaar will confound or annoy many viewers. Twenty minutes in, I didn’t think it would be to my taste. The charming little animated flashback sequence that opens the film – about a man adopting a little girl and bringing her to his castle – is followed immediately by eye-popping set design (we are back in live-action mode, but only just), loud humour and a stream of apparent stereotypes including a “Fundvani” – a Sindhi with bling – toting a golden gun alongside a Big Moose-like kid brother who has to be married into a wealthy family.

My initial misgivings were soon dispelled though. After watching Shaandaar and thoroughly enjoying most of it, I felt like this film has the cult-following potential of Shaad Ali’s opulent narrative-musical Jhoom Barabar Jhoom (which has polarized audiences spectacularly – those who love it really, really love it), Anurag Kashyap’s No Smoking, or even Pankaj Advani’s Sankat City (which hasn’t developed a cult following yet, so maybe I shouldn’t include it in this list). All those films are deliriously over the top in places, and necessarily take the risks that come with stepping into that territory. Watching them, I was reminded – to varying degrees – of what Roger Ebert wrote in the context of the 2000 film The Cell:

In this fable, when the prince (a wedding planner named Jagjinder Joginder or JJ, played by Shahid Kapoor) tries to gallantly rescue the kooky “princess” Alia (Alia Bhatt), it turns out he has misjudged the situation and she is only skinny-dipping late at night. Instead of waking up Snow White – freeing her from malice-induced slumber – JJ must cure her insomnia and get her to sleep (he also cures himself in the process). Along the way they have a mock light-sabre fight to the tune of “Eena Meena Deeka”. Meanwhile an old witch, played by Sushma Seth, gorges on aaloo-paratha while hired sopranos stand by the dining table singing about sundried tomatoes. (Please, don’t let anyone tell you that THAT scene is unrealistic or over the top, it isn’t: I have been to richie-rich NRI weddings in London, and I know.) There is even a frog who gets a kiss, but resolutely stays a frog.