Jai Arjun Singh's Blog, page 54

March 9, 2016

Hrishi-da and Guddi at JNU

Anyone in Delhi on March 16 who is interested in watching Guddi and/or listening to me pontificate about “the world of Hrishikesh Mukherjee”, please do come for a screening + talk at the School of Arts and Aesthetics, JNU, starting at 2 pm. Here is the link to the event page on Facebook. (It says 17.00-18.30 at the top of the page, but the correct details are provided further down.)

Anyone in Delhi on March 16 who is interested in watching Guddi and/or listening to me pontificate about “the world of Hrishikesh Mukherjee”, please do come for a screening + talk at the School of Arts and Aesthetics, JNU, starting at 2 pm. Here is the link to the event page on Facebook. (It says 17.00-18.30 at the top of the page, but the correct details are provided further down.)

Published on March 09, 2016 22:09

March 3, 2016

Little heroes and other patriots - thoughts on Neerja and Airlift

[My latest Mint Lounge column]

The first two months of 2016 have brought us a surprisingly large number of films with either “Ishq” or “Love” in the title (none of which I have yet seen), as well as adult comedies (plural!) starring Tusshar Kapoor. But there have also been two tightly crafted movies based on real-life events from close to three decades ago: Ram Madhvani’s Neerja , about the courage shown by flight purser Neerja Bhanot during the 1986 Pan Am hijack, and Raja Krishna Menon’s Airlift , about the mass evacuation of 1.7 lakh Indians from war-torn Kuwait in 1990. Both films did a fine job of recreating time and place and, as far as I can tell, stayed close to the broad facts (though the Airlift plot was a highly simplified one, and its businessman-turned-saviour protagonist Ranjit Katyal was a rough composite of two people).

There are differences in the specifics of the stories – one might flippantly note that Neerja is about a group of people badly wanting to get off a plane, while Airlift is about a (much larger) group of people yearning to get on one – but both involve claustrophobic spaces and fear so potent you can smell it in the air. They also contain material that could, in the hands of other writers or directors, have been manipulated in the direction of speech-making about national duty. This is truer of Airlift, in which a money-minded NRI – who had turned his eyes away from his home country – becomes, to his own surprise, a sort of Oskar Schindler, or even a Moses, for his compatriots. While watching it, I kept anticipating the big moment calculated to bring a tear to the eyes of those who wear their patriotism on their sleeve (and dreading that there would be a prolonged scene with the national anthem, requiring all of us in the hall to either stand up like obedient sheep or be made to feel like desh-drohis), but though there is a suspenseful moment involving the unfurling of the flag, it is done matter-of-factly; the intimate narrative is put before the grand one.

There are differences in the specifics of the stories – one might flippantly note that Neerja is about a group of people badly wanting to get off a plane, while Airlift is about a (much larger) group of people yearning to get on one – but both involve claustrophobic spaces and fear so potent you can smell it in the air. They also contain material that could, in the hands of other writers or directors, have been manipulated in the direction of speech-making about national duty. This is truer of Airlift, in which a money-minded NRI – who had turned his eyes away from his home country – becomes, to his own surprise, a sort of Oskar Schindler, or even a Moses, for his compatriots. While watching it, I kept anticipating the big moment calculated to bring a tear to the eyes of those who wear their patriotism on their sleeve (and dreading that there would be a prolonged scene with the national anthem, requiring all of us in the hall to either stand up like obedient sheep or be made to feel like desh-drohis), but though there is a suspenseful moment involving the unfurling of the flag, it is done matter-of-factly; the intimate narrative is put before the grand one.

The Neerja story, you might think, wouldn’t have lent itself to such treatment anyway, but consider the basic plot – an Indian air-hostess helps people of multiple nationalities who are stranded on Pakistani soil – and imagine what a fictionalized version could have done with it. It’s notable then that both films, though clearly tempted at times, keep steering away from the big picture. The heroism they depict is from the Frodo Baggins school, beginning in such small ways that you barely register it: a young woman with a turbulent relationship in her past and a love for inspirational dialogues from Rajesh Khanna films develops a kinship with three nervous kids; a businessman, making hurried arrangements for his own family to escape, happens to glance at one of his employees – someone he has barely noticed before – who is asking “What will happen to us?”

The Neerja story, you might think, wouldn’t have lent itself to such treatment anyway, but consider the basic plot – an Indian air-hostess helps people of multiple nationalities who are stranded on Pakistani soil – and imagine what a fictionalized version could have done with it. It’s notable then that both films, though clearly tempted at times, keep steering away from the big picture. The heroism they depict is from the Frodo Baggins school, beginning in such small ways that you barely register it: a young woman with a turbulent relationship in her past and a love for inspirational dialogues from Rajesh Khanna films develops a kinship with three nervous kids; a businessman, making hurried arrangements for his own family to escape, happens to glance at one of his employees – someone he has barely noticed before – who is asking “What will happen to us?”

In these scenes, one sees how the simple matter of connecting with another person can lead to big deeds; the films are about “ordinary” people discovering new reserves of humanity in themselves. At the time of writing this, I haven’t seen Hansal Mehta’s Aligarh, but his earlier Shahid – about the lawyer-activist Shahid Azmi – was another such film, with a protagonist who fights the good fight not as a superhero but as a flesh-and-blood man who can’t always look his wife in the eye when she confronts him (much like Ranjit’s wife does in Airlift) about his responsibility to keep himself safe.

One reason I have been thinking about “small” heroes – people who had little desire in the first place to be heroic, or to be thrust into a situation that required heroism – is because we are surrounded by large-picture narratives these days. In the wake of the JNU arrests, there has been plenty of talk extolling our duties and loyalties towards this huge thing called the Nation, and the celebration of a much more exalted form of heroism, the sort that is pre-packaged and tied up to unquestioning allegiance. It includes the idea that war – if you do it in the name of country – is innately noble, almost independently of context. And that questioning the sanctity of these ideals or murats is in itself wrong. Or seditious.

Many people I know admire films like Shahid, Neerja and Airlift because they are “gritty”, “understated”, “real”, and represent another step away from the excesses of older Hindi cinema. But hyper-drama and grandstanding are vital parts of the human condition too, and if these low-key films refuse to give us that particular form of catharsis, then non-fiction TV has been taking up the role with gusto. Consider the rabble-rousing and dialogue-baazi in the parliamentary-session telecasts. Or the widely watched news-channel show where a veteran army-man wept because of the “disrespect” being shown to the national flag, after which we got to hear a solicitous audio recording in the voice of HRD minister Smriti Irani – all of this calibrated for maximum emotional effect, stoking the nationalistic sentiments of people who already subscribed to the view that physical violence in the premises of a Delhi court was a reasonable response to words spoken out loud in a university campus.

“disrespect” being shown to the national flag, after which we got to hear a solicitous audio recording in the voice of HRD minister Smriti Irani – all of this calibrated for maximum emotional effect, stoking the nationalistic sentiments of people who already subscribed to the view that physical violence in the premises of a Delhi court was a reasonable response to words spoken out loud in a university campus.

As indicated in earlier columns, I have plenty of time for the (well-made) melodramatic film which performs a very different function from the quiet, subdued one. In the current climate, though, with news anchors and politicians doing the declamatory things that Sohrab Modi and his inheritors once did on the big screen, it’s a relief to watch a film about a more tentative, even reluctant heroism that isn’t tied to the idea of one’s country being the best, just because one happened to be born in it. A heroism that grows to become something meaningful and inclusive. Who would argue that Neerja Bhanot and Ranjit Katyal, as depicted in these films, weren’t in the final analysis great patriots – if that word is to have any worth?

------------------------------

[A long piece about Hansal Mehta's Shahid is here. And here's a post about one of our most celebrated filmic patriots, Manoj Kumar]

The first two months of 2016 have brought us a surprisingly large number of films with either “Ishq” or “Love” in the title (none of which I have yet seen), as well as adult comedies (plural!) starring Tusshar Kapoor. But there have also been two tightly crafted movies based on real-life events from close to three decades ago: Ram Madhvani’s Neerja , about the courage shown by flight purser Neerja Bhanot during the 1986 Pan Am hijack, and Raja Krishna Menon’s Airlift , about the mass evacuation of 1.7 lakh Indians from war-torn Kuwait in 1990. Both films did a fine job of recreating time and place and, as far as I can tell, stayed close to the broad facts (though the Airlift plot was a highly simplified one, and its businessman-turned-saviour protagonist Ranjit Katyal was a rough composite of two people).

There are differences in the specifics of the stories – one might flippantly note that Neerja is about a group of people badly wanting to get off a plane, while Airlift is about a (much larger) group of people yearning to get on one – but both involve claustrophobic spaces and fear so potent you can smell it in the air. They also contain material that could, in the hands of other writers or directors, have been manipulated in the direction of speech-making about national duty. This is truer of Airlift, in which a money-minded NRI – who had turned his eyes away from his home country – becomes, to his own surprise, a sort of Oskar Schindler, or even a Moses, for his compatriots. While watching it, I kept anticipating the big moment calculated to bring a tear to the eyes of those who wear their patriotism on their sleeve (and dreading that there would be a prolonged scene with the national anthem, requiring all of us in the hall to either stand up like obedient sheep or be made to feel like desh-drohis), but though there is a suspenseful moment involving the unfurling of the flag, it is done matter-of-factly; the intimate narrative is put before the grand one.

There are differences in the specifics of the stories – one might flippantly note that Neerja is about a group of people badly wanting to get off a plane, while Airlift is about a (much larger) group of people yearning to get on one – but both involve claustrophobic spaces and fear so potent you can smell it in the air. They also contain material that could, in the hands of other writers or directors, have been manipulated in the direction of speech-making about national duty. This is truer of Airlift, in which a money-minded NRI – who had turned his eyes away from his home country – becomes, to his own surprise, a sort of Oskar Schindler, or even a Moses, for his compatriots. While watching it, I kept anticipating the big moment calculated to bring a tear to the eyes of those who wear their patriotism on their sleeve (and dreading that there would be a prolonged scene with the national anthem, requiring all of us in the hall to either stand up like obedient sheep or be made to feel like desh-drohis), but though there is a suspenseful moment involving the unfurling of the flag, it is done matter-of-factly; the intimate narrative is put before the grand one. The Neerja story, you might think, wouldn’t have lent itself to such treatment anyway, but consider the basic plot – an Indian air-hostess helps people of multiple nationalities who are stranded on Pakistani soil – and imagine what a fictionalized version could have done with it. It’s notable then that both films, though clearly tempted at times, keep steering away from the big picture. The heroism they depict is from the Frodo Baggins school, beginning in such small ways that you barely register it: a young woman with a turbulent relationship in her past and a love for inspirational dialogues from Rajesh Khanna films develops a kinship with three nervous kids; a businessman, making hurried arrangements for his own family to escape, happens to glance at one of his employees – someone he has barely noticed before – who is asking “What will happen to us?”

The Neerja story, you might think, wouldn’t have lent itself to such treatment anyway, but consider the basic plot – an Indian air-hostess helps people of multiple nationalities who are stranded on Pakistani soil – and imagine what a fictionalized version could have done with it. It’s notable then that both films, though clearly tempted at times, keep steering away from the big picture. The heroism they depict is from the Frodo Baggins school, beginning in such small ways that you barely register it: a young woman with a turbulent relationship in her past and a love for inspirational dialogues from Rajesh Khanna films develops a kinship with three nervous kids; a businessman, making hurried arrangements for his own family to escape, happens to glance at one of his employees – someone he has barely noticed before – who is asking “What will happen to us?”In these scenes, one sees how the simple matter of connecting with another person can lead to big deeds; the films are about “ordinary” people discovering new reserves of humanity in themselves. At the time of writing this, I haven’t seen Hansal Mehta’s Aligarh, but his earlier Shahid – about the lawyer-activist Shahid Azmi – was another such film, with a protagonist who fights the good fight not as a superhero but as a flesh-and-blood man who can’t always look his wife in the eye when she confronts him (much like Ranjit’s wife does in Airlift) about his responsibility to keep himself safe.

One reason I have been thinking about “small” heroes – people who had little desire in the first place to be heroic, or to be thrust into a situation that required heroism – is because we are surrounded by large-picture narratives these days. In the wake of the JNU arrests, there has been plenty of talk extolling our duties and loyalties towards this huge thing called the Nation, and the celebration of a much more exalted form of heroism, the sort that is pre-packaged and tied up to unquestioning allegiance. It includes the idea that war – if you do it in the name of country – is innately noble, almost independently of context. And that questioning the sanctity of these ideals or murats is in itself wrong. Or seditious.

Many people I know admire films like Shahid, Neerja and Airlift because they are “gritty”, “understated”, “real”, and represent another step away from the excesses of older Hindi cinema. But hyper-drama and grandstanding are vital parts of the human condition too, and if these low-key films refuse to give us that particular form of catharsis, then non-fiction TV has been taking up the role with gusto. Consider the rabble-rousing and dialogue-baazi in the parliamentary-session telecasts. Or the widely watched news-channel show where a veteran army-man wept because of the

“disrespect” being shown to the national flag, after which we got to hear a solicitous audio recording in the voice of HRD minister Smriti Irani – all of this calibrated for maximum emotional effect, stoking the nationalistic sentiments of people who already subscribed to the view that physical violence in the premises of a Delhi court was a reasonable response to words spoken out loud in a university campus.

“disrespect” being shown to the national flag, after which we got to hear a solicitous audio recording in the voice of HRD minister Smriti Irani – all of this calibrated for maximum emotional effect, stoking the nationalistic sentiments of people who already subscribed to the view that physical violence in the premises of a Delhi court was a reasonable response to words spoken out loud in a university campus. As indicated in earlier columns, I have plenty of time for the (well-made) melodramatic film which performs a very different function from the quiet, subdued one. In the current climate, though, with news anchors and politicians doing the declamatory things that Sohrab Modi and his inheritors once did on the big screen, it’s a relief to watch a film about a more tentative, even reluctant heroism that isn’t tied to the idea of one’s country being the best, just because one happened to be born in it. A heroism that grows to become something meaningful and inclusive. Who would argue that Neerja Bhanot and Ranjit Katyal, as depicted in these films, weren’t in the final analysis great patriots – if that word is to have any worth?

------------------------------

[A long piece about Hansal Mehta's Shahid is here. And here's a post about one of our most celebrated filmic patriots, Manoj Kumar]

Published on March 03, 2016 05:41

February 18, 2016

On Devashish Makhija’s Taandav (and other dancing men)

[My latest Mint Lounge column]

In Devashish Makhija’s brilliant new short film Taandav , a constable named Tambe (Manoj Bajpayee) points a gun at two men who have been getting on his nerves. “Naach,” he tells them, with all the authority conferred by uniform and position, but then, a few seconds later, he begins to dance himself. That’s an inadequate description though – it would be more accurate to say that he does a delirious, uninhibited version of Lord Shiva’s taandav, which is many different things depending on how you view it: a dance of creation or destruction, unmaking or remaking, despair or catharsis, or all of these.

Tambe is having a hard time of it, we learn early in this 11-minute movie (which you can watch online here). He can’t afford the fees needed to send his little girl to a good school. He then passes up a chance to purloin a stash of black money and share it with two other policemen (no one else was likely to find out). His wife and daughter are sad, the cops are frustrated, things have come to a boil – and now, faced with the pagan revelry of a Ganesh Visarjan night, something inside him explodes. At first his dance is both menacing and mildly comic – you wonder if he is having a mental breakdown and is about to start shooting around wildly. But before you realize it, it becomes a kinetic exercise in self-expression.

Tambe is having a hard time of it, we learn early in this 11-minute movie (which you can watch online here). He can’t afford the fees needed to send his little girl to a good school. He then passes up a chance to purloin a stash of black money and share it with two other policemen (no one else was likely to find out). His wife and daughter are sad, the cops are frustrated, things have come to a boil – and now, faced with the pagan revelry of a Ganesh Visarjan night, something inside him explodes. At first his dance is both menacing and mildly comic – you wonder if he is having a mental breakdown and is about to start shooting around wildly. But before you realize it, it becomes a kinetic exercise in self-expression.

Despite the taandav reference, the first image that leapt into my mind while watching this scene was from a non-Indian source: the actor Christopher Walken’s dance performance in the Fatboy Slim music video “Weapon of Choice”. (If you haven’t seen it, drop everything and go watch it now. Again, YouTube is your friend.)

What connects the two scenes? Both are very funny and very unexpected – you shake your head disbelievingly even as you admire the actors’ work – and this is partly because the characters are dour-looking patriarchal figures. Both men are also constrained in clothes that don’t seem right for exuberant dancing: Tambe is in a well-fitting police uniform, while the Walken character (a morose businessman?) is in formal suit and tie. The costumes are suggestive of the larger shackles that such men can find themselves in – as authority figures who are expected to be always detached and in control, not go wild, much less perform for the amusement of others. And the dances are acts of liberation. Tambe has stepped out of his straitjacket (this episode will lead to him literally losing his vardi too) and is playing his own tune. The Voltaire quote that ends Makhija’s film – “Man is free at the moment he wishes to be” – finds an echo in the Fatboy Slim song lyrics “Check out my new weapon, weapon of choice” and “If you walk without rhythm, you never learn”. (It might be worth mentioning here that Walken, who trained as a dancer at an early age, had become typecast in “serious” roles as a screen actor, and “Weapon of Choice” was an assignment he took on – at age 58 – with childlike delight.)

businessman?) is in formal suit and tie. The costumes are suggestive of the larger shackles that such men can find themselves in – as authority figures who are expected to be always detached and in control, not go wild, much less perform for the amusement of others. And the dances are acts of liberation. Tambe has stepped out of his straitjacket (this episode will lead to him literally losing his vardi too) and is playing his own tune. The Voltaire quote that ends Makhija’s film – “Man is free at the moment he wishes to be” – finds an echo in the Fatboy Slim song lyrics “Check out my new weapon, weapon of choice” and “If you walk without rhythm, you never learn”. (It might be worth mentioning here that Walken, who trained as a dancer at an early age, had become typecast in “serious” roles as a screen actor, and “Weapon of Choice” was an assignment he took on – at age 58 – with childlike delight.)

A fevered dance as a transcendental act, as a discovery of new possibilities: this is something we usually associate with female performers in our cinema – whether it is Waheeda Rehman’s legendary snake dance in Guide (where the character, Rosie, goes back to what she loves best, her art) or Madhubala’s “Pyaar kiya toh darna kya” in Mughal-e-Azam (a courtesan defies an empire and turns a showy palace into her personal hall of mirrors) or, in a less weighty mode, Sridevi’s “Kaate nahin kat te” in Mr India (the scene where the no-nonsense, Lois Lane-like heroine gets in touch with her sexually desirous side).

A fevered dance as a transcendental act, as a discovery of new possibilities: this is something we usually associate with female performers in our cinema – whether it is Waheeda Rehman’s legendary snake dance in Guide (where the character, Rosie, goes back to what she loves best, her art) or Madhubala’s “Pyaar kiya toh darna kya” in Mughal-e-Azam (a courtesan defies an empire and turns a showy palace into her personal hall of mirrors) or, in a less weighty mode, Sridevi’s “Kaate nahin kat te” in Mr India (the scene where the no-nonsense, Lois Lane-like heroine gets in touch with her sexually desirous side).

Male actors – not so much. I grew up in an era where some leading men – Mithun Chakraborty, Rishi Kapoor, Kamal Haasan, later Govinda – were adept on their feet, but the musical scenes were mostly regular romantic scenes rather than intense solos. Besides, consider deeper history. It is well-chronicled that before the advent of Shammi Kapoor – a phenomenon unto himself, not quite replicable – dancing did not come naturally to our male actors; they were much more often passive spectators, or beaming beneficiaries of a woman’s attention. Dilip Kumar did his first full-fledged dance scene 16 years into his career, in Gunga Jumna. And though we think of Dev Anand as the unruffled romantic hero, he had some surprisingly awkward moments when called upon to dance. “Tasveer Teri Dil Mein” from the 1961 Maya is a lovely song, but watch the scene: Anand is passable when he is just bobbing his head and clasping his hands while Mala Sinha does most of the work, but when the framing forces him to jig along in a full-body shot, it resembles a Jar Jar Binks action sequence from the Star Wars prequels.

No wonder then that Tambe’s dance is so uplifting, despite the grimness of his situation. The family’s troubles can have only grown with his suspension, yet the film’s closing scene is a warm, optimistic one: watching his wife and daughter watching a YouTube video of his taandav, he chuckles, and then they all laugh together. His brief transgression has, as with Shiva’s dance, remade a world.

In Devashish Makhija’s brilliant new short film Taandav , a constable named Tambe (Manoj Bajpayee) points a gun at two men who have been getting on his nerves. “Naach,” he tells them, with all the authority conferred by uniform and position, but then, a few seconds later, he begins to dance himself. That’s an inadequate description though – it would be more accurate to say that he does a delirious, uninhibited version of Lord Shiva’s taandav, which is many different things depending on how you view it: a dance of creation or destruction, unmaking or remaking, despair or catharsis, or all of these.

Tambe is having a hard time of it, we learn early in this 11-minute movie (which you can watch online here). He can’t afford the fees needed to send his little girl to a good school. He then passes up a chance to purloin a stash of black money and share it with two other policemen (no one else was likely to find out). His wife and daughter are sad, the cops are frustrated, things have come to a boil – and now, faced with the pagan revelry of a Ganesh Visarjan night, something inside him explodes. At first his dance is both menacing and mildly comic – you wonder if he is having a mental breakdown and is about to start shooting around wildly. But before you realize it, it becomes a kinetic exercise in self-expression.

Tambe is having a hard time of it, we learn early in this 11-minute movie (which you can watch online here). He can’t afford the fees needed to send his little girl to a good school. He then passes up a chance to purloin a stash of black money and share it with two other policemen (no one else was likely to find out). His wife and daughter are sad, the cops are frustrated, things have come to a boil – and now, faced with the pagan revelry of a Ganesh Visarjan night, something inside him explodes. At first his dance is both menacing and mildly comic – you wonder if he is having a mental breakdown and is about to start shooting around wildly. But before you realize it, it becomes a kinetic exercise in self-expression.Despite the taandav reference, the first image that leapt into my mind while watching this scene was from a non-Indian source: the actor Christopher Walken’s dance performance in the Fatboy Slim music video “Weapon of Choice”. (If you haven’t seen it, drop everything and go watch it now. Again, YouTube is your friend.)

What connects the two scenes? Both are very funny and very unexpected – you shake your head disbelievingly even as you admire the actors’ work – and this is partly because the characters are dour-looking patriarchal figures. Both men are also constrained in clothes that don’t seem right for exuberant dancing: Tambe is in a well-fitting police uniform, while the Walken character (a morose

businessman?) is in formal suit and tie. The costumes are suggestive of the larger shackles that such men can find themselves in – as authority figures who are expected to be always detached and in control, not go wild, much less perform for the amusement of others. And the dances are acts of liberation. Tambe has stepped out of his straitjacket (this episode will lead to him literally losing his vardi too) and is playing his own tune. The Voltaire quote that ends Makhija’s film – “Man is free at the moment he wishes to be” – finds an echo in the Fatboy Slim song lyrics “Check out my new weapon, weapon of choice” and “If you walk without rhythm, you never learn”. (It might be worth mentioning here that Walken, who trained as a dancer at an early age, had become typecast in “serious” roles as a screen actor, and “Weapon of Choice” was an assignment he took on – at age 58 – with childlike delight.)

businessman?) is in formal suit and tie. The costumes are suggestive of the larger shackles that such men can find themselves in – as authority figures who are expected to be always detached and in control, not go wild, much less perform for the amusement of others. And the dances are acts of liberation. Tambe has stepped out of his straitjacket (this episode will lead to him literally losing his vardi too) and is playing his own tune. The Voltaire quote that ends Makhija’s film – “Man is free at the moment he wishes to be” – finds an echo in the Fatboy Slim song lyrics “Check out my new weapon, weapon of choice” and “If you walk without rhythm, you never learn”. (It might be worth mentioning here that Walken, who trained as a dancer at an early age, had become typecast in “serious” roles as a screen actor, and “Weapon of Choice” was an assignment he took on – at age 58 – with childlike delight.) A fevered dance as a transcendental act, as a discovery of new possibilities: this is something we usually associate with female performers in our cinema – whether it is Waheeda Rehman’s legendary snake dance in Guide (where the character, Rosie, goes back to what she loves best, her art) or Madhubala’s “Pyaar kiya toh darna kya” in Mughal-e-Azam (a courtesan defies an empire and turns a showy palace into her personal hall of mirrors) or, in a less weighty mode, Sridevi’s “Kaate nahin kat te” in Mr India (the scene where the no-nonsense, Lois Lane-like heroine gets in touch with her sexually desirous side).

A fevered dance as a transcendental act, as a discovery of new possibilities: this is something we usually associate with female performers in our cinema – whether it is Waheeda Rehman’s legendary snake dance in Guide (where the character, Rosie, goes back to what she loves best, her art) or Madhubala’s “Pyaar kiya toh darna kya” in Mughal-e-Azam (a courtesan defies an empire and turns a showy palace into her personal hall of mirrors) or, in a less weighty mode, Sridevi’s “Kaate nahin kat te” in Mr India (the scene where the no-nonsense, Lois Lane-like heroine gets in touch with her sexually desirous side).Male actors – not so much. I grew up in an era where some leading men – Mithun Chakraborty, Rishi Kapoor, Kamal Haasan, later Govinda – were adept on their feet, but the musical scenes were mostly regular romantic scenes rather than intense solos. Besides, consider deeper history. It is well-chronicled that before the advent of Shammi Kapoor – a phenomenon unto himself, not quite replicable – dancing did not come naturally to our male actors; they were much more often passive spectators, or beaming beneficiaries of a woman’s attention. Dilip Kumar did his first full-fledged dance scene 16 years into his career, in Gunga Jumna. And though we think of Dev Anand as the unruffled romantic hero, he had some surprisingly awkward moments when called upon to dance. “Tasveer Teri Dil Mein” from the 1961 Maya is a lovely song, but watch the scene: Anand is passable when he is just bobbing his head and clasping his hands while Mala Sinha does most of the work, but when the framing forces him to jig along in a full-body shot, it resembles a Jar Jar Binks action sequence from the Star Wars prequels.

No wonder then that Tambe’s dance is so uplifting, despite the grimness of his situation. The family’s troubles can have only grown with his suspension, yet the film’s closing scene is a warm, optimistic one: watching his wife and daughter watching a YouTube video of his taandav, he chuckles, and then they all laugh together. His brief transgression has, as with Shiva’s dance, remade a world.

Published on February 18, 2016 22:06

February 4, 2016

The life of the mind: writers on screen, writers in caves

[My latest Mint Lounge column]

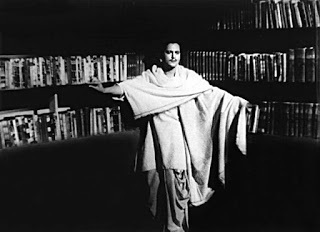

The actor Rajesh Vivek, who died last month, was probably best known to contemporary audiences as the hirsute seam-bowler Guran in Lagaan. Those whose memories stretch back further might remember his short but compelling part as a possessed fakir in Shyam Benegal’s Junoon two decades earlier. Speaking for myself though, another Vivek performance has top recall value. Long before I became a professional writer, his role as the sage-cum-scribe Veda Vyasa in the 1980s TV version of the Mahabharata gave me an early – possibly subconscious – hint that writers can be weird people.

As a youngster watching the show through a fault-finding lens (I had been a Mahabharata buff for years already, and unforgiving of any little trespasses), it was obvious that much of it conformed to an anodyne, Amar Chitra Katha-like template: costumes and mukuts (crowns) were just so, even the colours of the main characters’ clothing often matched the comic-book versions. The big difference was when Vyasa showed up. Grimy, disheveled, smiling wryly, he was very different from the archetype of the rishi with the snow-white Santa Claus beard. Obviously he was meant to look forbidding in the key scene where the widowed princesses Ambika and Ambalika are frightened by him (during the conceptions of the blind Dhritarashtra and the pale-complexioned Pandu respectively), but even otherwise there was a touch of the enfant terrible about Vivek. Speaking his lines in a coarse, casual way, he brought an off-kilter quality to the show. Which was appropriate in a way, because Vyasa is a disruptive force – the author who enters his own story and participates in it to keep the narrative moving.

Anyway, it was thus I learnt that writers didn’t behave like anyone else: they came, whence no one knew, and went as they pleased; living in solitude most of the time, they showed up for grand parties once a year (Rajasuya Yagnas back then, literature festivals today), quaffed a few dozen glasses of wine, impregnated some princesses maybe, and then went back shyly to their caves, mountaintops or barsaatis.

With literature-festival season well underway, I have been thinking about the ongoing metamorphosis of authors from solitary types to social-media celebrities. As I write this, I’m preparing to moderate a session at Jaipur with the bestselling writers Ravinder Singh, Ravi Subramanian and Anuja Chauhan, all of whom are glamorous,

Yeh kitaabein agar likh bhi diye toh kya hai?savvy and confident. Looking at them, one doesn’t think of the poets in gutters who have populated our cinematic past: the tragic, self-flagellating ones – for whom Guru Dutt’s Vijay in Pyaasa is the poster boy – as well as the ones who joke about their straits. In Anupama, when Ashok (Dharmendra) tells someone he is a writer, the response is “Lekin aap kaam kya karte hain? (But what work do you do?”) and he takes it in good spirit. At the beginning of Anand, a writer quips that he had to sell his bicycle to get his novel published. And one of my favourite sequences from V Shantaram’s

Navrang

is the song “Kaviraaja Kavita ke Mat ab Kaan Marodo”, where at an informal mehfil, a poet playfully advises his friends that they are better off selling grain or being money-lenders.

Yeh kitaabein agar likh bhi diye toh kya hai?savvy and confident. Looking at them, one doesn’t think of the poets in gutters who have populated our cinematic past: the tragic, self-flagellating ones – for whom Guru Dutt’s Vijay in Pyaasa is the poster boy – as well as the ones who joke about their straits. In Anupama, when Ashok (Dharmendra) tells someone he is a writer, the response is “Lekin aap kaam kya karte hain? (But what work do you do?”) and he takes it in good spirit. At the beginning of Anand, a writer quips that he had to sell his bicycle to get his novel published. And one of my favourite sequences from V Shantaram’s

Navrang

is the song “Kaviraaja Kavita ke Mat ab Kaan Marodo”, where at an informal mehfil, a poet playfully advises his friends that they are better off selling grain or being money-lenders.

In recent years, depictions of writers have been more in keeping with the changing image of the profession, and aided by films that are adapted from bestselling novels. Arjun Kapoor, playing a version of Chetan Bhagat in 2 States, is allowed to look studious and thoughtful, but generally gets to do the things that most Hindi-movie heroes do: sing, romance, clown about. In Happy Ending, the bickering novelists played by Saif Ali Khan and Ileana D’Cruz are successful and trendy, but listening to their trite conversations one is hard put to imagine they could have written anything of quality.

I have mixed feelings about these films. In my view, movies featuring writers as protagonists should have a tinge of horror. Like the ones based on Stephen King stories: Secret Window (writer is plagued by a stalker who may be his own creation) or Misery (writer is held captive by a potentially violent fan). And this is why my favourite scene from a film about writers is the apocalyptic climax of the Coen Brothers’ Barton Fink, a story about a screenwriter trapped in a plebeian Hell – but also about how a tortured artist can create Hell around him. In that scene, a salesman named Charlie (superbly played by John Goodman) charges down a hotel corridor with rifle in hand as the walls explode in flame around him. “I’ll show you the life of the mind!” he bellows, a reference to an earlier dialogue involving the sort of work writers do, which is meant to be “superior” to that of everyone else.

my favourite scene from a film about writers is the apocalyptic climax of the Coen Brothers’ Barton Fink, a story about a screenwriter trapped in a plebeian Hell – but also about how a tortured artist can create Hell around him. In that scene, a salesman named Charlie (superbly played by John Goodman) charges down a hotel corridor with rifle in hand as the walls explode in flame around him. “I’ll show you the life of the mind!” he bellows, a reference to an earlier dialogue involving the sort of work writers do, which is meant to be “superior” to that of everyone else.

When things are getting too noisy at a big literary event, I admit to having the sort of dark fantasy where Charlie shows up in that mood, to spice things up a little and send writers scuttling back to their caves.

[Some more gloomy reflections on lit-fests in this piece about Howard Jacobson's The Finkler Question]

The actor Rajesh Vivek, who died last month, was probably best known to contemporary audiences as the hirsute seam-bowler Guran in Lagaan. Those whose memories stretch back further might remember his short but compelling part as a possessed fakir in Shyam Benegal’s Junoon two decades earlier. Speaking for myself though, another Vivek performance has top recall value. Long before I became a professional writer, his role as the sage-cum-scribe Veda Vyasa in the 1980s TV version of the Mahabharata gave me an early – possibly subconscious – hint that writers can be weird people.

As a youngster watching the show through a fault-finding lens (I had been a Mahabharata buff for years already, and unforgiving of any little trespasses), it was obvious that much of it conformed to an anodyne, Amar Chitra Katha-like template: costumes and mukuts (crowns) were just so, even the colours of the main characters’ clothing often matched the comic-book versions. The big difference was when Vyasa showed up. Grimy, disheveled, smiling wryly, he was very different from the archetype of the rishi with the snow-white Santa Claus beard. Obviously he was meant to look forbidding in the key scene where the widowed princesses Ambika and Ambalika are frightened by him (during the conceptions of the blind Dhritarashtra and the pale-complexioned Pandu respectively), but even otherwise there was a touch of the enfant terrible about Vivek. Speaking his lines in a coarse, casual way, he brought an off-kilter quality to the show. Which was appropriate in a way, because Vyasa is a disruptive force – the author who enters his own story and participates in it to keep the narrative moving.

Anyway, it was thus I learnt that writers didn’t behave like anyone else: they came, whence no one knew, and went as they pleased; living in solitude most of the time, they showed up for grand parties once a year (Rajasuya Yagnas back then, literature festivals today), quaffed a few dozen glasses of wine, impregnated some princesses maybe, and then went back shyly to their caves, mountaintops or barsaatis.

With literature-festival season well underway, I have been thinking about the ongoing metamorphosis of authors from solitary types to social-media celebrities. As I write this, I’m preparing to moderate a session at Jaipur with the bestselling writers Ravinder Singh, Ravi Subramanian and Anuja Chauhan, all of whom are glamorous,

Yeh kitaabein agar likh bhi diye toh kya hai?savvy and confident. Looking at them, one doesn’t think of the poets in gutters who have populated our cinematic past: the tragic, self-flagellating ones – for whom Guru Dutt’s Vijay in Pyaasa is the poster boy – as well as the ones who joke about their straits. In Anupama, when Ashok (Dharmendra) tells someone he is a writer, the response is “Lekin aap kaam kya karte hain? (But what work do you do?”) and he takes it in good spirit. At the beginning of Anand, a writer quips that he had to sell his bicycle to get his novel published. And one of my favourite sequences from V Shantaram’s

Navrang

is the song “Kaviraaja Kavita ke Mat ab Kaan Marodo”, where at an informal mehfil, a poet playfully advises his friends that they are better off selling grain or being money-lenders.

Yeh kitaabein agar likh bhi diye toh kya hai?savvy and confident. Looking at them, one doesn’t think of the poets in gutters who have populated our cinematic past: the tragic, self-flagellating ones – for whom Guru Dutt’s Vijay in Pyaasa is the poster boy – as well as the ones who joke about their straits. In Anupama, when Ashok (Dharmendra) tells someone he is a writer, the response is “Lekin aap kaam kya karte hain? (But what work do you do?”) and he takes it in good spirit. At the beginning of Anand, a writer quips that he had to sell his bicycle to get his novel published. And one of my favourite sequences from V Shantaram’s

Navrang

is the song “Kaviraaja Kavita ke Mat ab Kaan Marodo”, where at an informal mehfil, a poet playfully advises his friends that they are better off selling grain or being money-lenders.In recent years, depictions of writers have been more in keeping with the changing image of the profession, and aided by films that are adapted from bestselling novels. Arjun Kapoor, playing a version of Chetan Bhagat in 2 States, is allowed to look studious and thoughtful, but generally gets to do the things that most Hindi-movie heroes do: sing, romance, clown about. In Happy Ending, the bickering novelists played by Saif Ali Khan and Ileana D’Cruz are successful and trendy, but listening to their trite conversations one is hard put to imagine they could have written anything of quality.

I have mixed feelings about these films. In my view, movies featuring writers as protagonists should have a tinge of horror. Like the ones based on Stephen King stories: Secret Window (writer is plagued by a stalker who may be his own creation) or Misery (writer is held captive by a potentially violent fan). And this is why

my favourite scene from a film about writers is the apocalyptic climax of the Coen Brothers’ Barton Fink, a story about a screenwriter trapped in a plebeian Hell – but also about how a tortured artist can create Hell around him. In that scene, a salesman named Charlie (superbly played by John Goodman) charges down a hotel corridor with rifle in hand as the walls explode in flame around him. “I’ll show you the life of the mind!” he bellows, a reference to an earlier dialogue involving the sort of work writers do, which is meant to be “superior” to that of everyone else.

my favourite scene from a film about writers is the apocalyptic climax of the Coen Brothers’ Barton Fink, a story about a screenwriter trapped in a plebeian Hell – but also about how a tortured artist can create Hell around him. In that scene, a salesman named Charlie (superbly played by John Goodman) charges down a hotel corridor with rifle in hand as the walls explode in flame around him. “I’ll show you the life of the mind!” he bellows, a reference to an earlier dialogue involving the sort of work writers do, which is meant to be “superior” to that of everyone else. When things are getting too noisy at a big literary event, I admit to having the sort of dark fantasy where Charlie shows up in that mood, to spice things up a little and send writers scuttling back to their caves.

[Some more gloomy reflections on lit-fests in this piece about Howard Jacobson's The Finkler Question]

Published on February 04, 2016 16:27

January 31, 2016

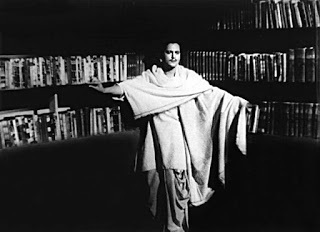

Jaipur and Kolkata with Sharmila Tagore, the Akhtars and others - photos, updates

As mentioned earlier, I have been putting up lit-fest reports on Facebook rather than on the blog (those are public posts, I think you can see them even if you don’t have an FB account) - but every once in a while, it makes sense to post something here too. So here goes.

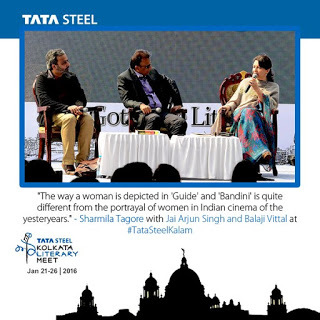

I had a very nice discussion with Sharmila Tagore and Balaji Vittal at the Kolkata Literary Meet on Jan 25. Sharmila ji was gracious as usual, and in a good mood too. One highlight: her recalling an incident during the Satyakam shoot near Jamshedpur where a bunch of youngsters tried to disrupt the shoot/generally misbehave. Dharmendra pulled one of them across by his collar, Sharmila ji told us (“and have you seen Dharam’s hands?”) and gave him a couple of slaps. “Because we did that sort of thing in those days,” she added drily, to much laughter (and I thought about Sulekha being teasingly called a “Communist” because she carries her own bags from the bus in Chupke Chupke).

I had a very nice discussion with Sharmila Tagore and Balaji Vittal at the Kolkata Literary Meet on Jan 25. Sharmila ji was gracious as usual, and in a good mood too. One highlight: her recalling an incident during the Satyakam shoot near Jamshedpur where a bunch of youngsters tried to disrupt the shoot/generally misbehave. Dharmendra pulled one of them across by his collar, Sharmila ji told us (“and have you seen Dharam’s hands?”) and gave him a couple of slaps. “Because we did that sort of thing in those days,” she added drily, to much laughter (and I thought about Sulekha being teasingly called a “Communist” because she carries her own bags from the bus in Chupke Chupke).

Also, in response to an audience question about her famous bikini shoot in 1966: “I did it because I thought I looked good. One should do these things at the right time, no? I mean, there would be no point my wearing a bikini today.” Watching her on stage, and speaking with her before we went up, it was very hard to believe that this year marks the 50th anniversary of Anupama, An Evening in Paris and Nayak.

My favourite Sharmila moment though had nothing to do with the filmi discussion. It was just before we went up on stage when, right in the middle of an interview, she stopped, pointed at one of the Victoria Memorial’s stray pups sitting nearby, and asked if someone could give it some water because it looked thirsty and unwell.

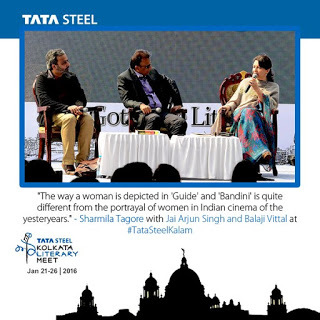

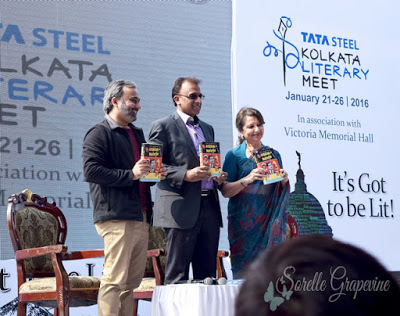

The pic below is courtesy the Sorelle Grapevine blog, which also has a nice writeup about the session, plus a short video. See here.

---------------------

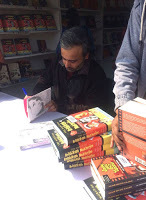

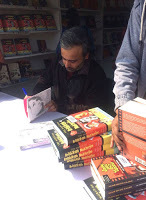

Got to sign copies of my three books at the little stall outside Victoria Memorial. It was nice to see The Popcorn Essayists there. (Treat this as a re-plug for an anthology containing some very good pieces by Anjum Hasan, Rajorshi Chakraborti, Namita Gokhale, Amitava Kumar, Kamila Shamsie, Sumana Roy, Manjula Padmanabhan, Madhulika Liddle, Sidin Vadukut, Manil Suri, Musharraf Ali Farooqi and Jaishree Misra.)

In this pic, the Popcorn Essayists, Jaane bhi do Yaaro and Hrishikesh Mukherjee can be seen in the company of many worthies, including Anirudha Bhattacharjee and Balaji Vittal’s two books, and Amitava Nag’s new book about Soumitra Chatterjee.

In this pic, the Popcorn Essayists, Jaane bhi do Yaaro and Hrishikesh Mukherjee can be seen in the company of many worthies, including Anirudha Bhattacharjee and Balaji Vittal’s two books, and Amitava Nag’s new book about Soumitra Chatterjee.

------------------------------

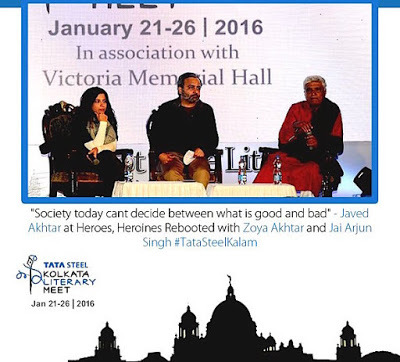

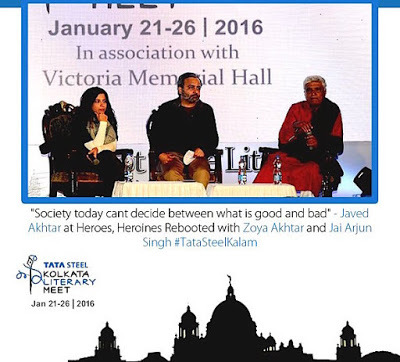

Then there was the session with Javed Akhtar and Zoya Akhtar, which went off well, I’m told. (I can never judge these things while up on stage.) Javed-Saab was looking a bit like the angry young man the couple of times I ran into him in Jaipur (and later at the Kolkata airport, where people peremptorily came up and took selfies with him without even saying a proper hello, as if he were a wax statue or something) - but he was in good form at the Kalam session, especially when dealing with audience questions near the end.

------------------------

And here are pics from the sessions at the Jaipur Literature Festival, where Anuja Chauhan and I played musical chairs with the moderator’s seat. First, “The Craft of the Bestseller” with Anuja, Ravi Subramanian and the massively popular Ravinder Singh who continues to thrill crowds and readers despite his repeated admissions that he doesn’t read books himself. And then, “Jaane Kahaan Gaye Woh Din: New Books about Old Bollywood” with Rauf Ahmed and Anuja.

The video of the “Jaane Kahaan” session is here. At one point during the first half of the session, Rauf saab seemed to forget that the panel was only 45-50 minutes long (and that most of the audience would need some context for the inside references he was making to old-time movies and movie-stars), but Anuja deftly got things back on track, and I got to speak a bit too.

[Don’t have time at the moment to do detailed reports of any of the sessions, but will try at a future date]

I had a very nice discussion with Sharmila Tagore and Balaji Vittal at the Kolkata Literary Meet on Jan 25. Sharmila ji was gracious as usual, and in a good mood too. One highlight: her recalling an incident during the Satyakam shoot near Jamshedpur where a bunch of youngsters tried to disrupt the shoot/generally misbehave. Dharmendra pulled one of them across by his collar, Sharmila ji told us (“and have you seen Dharam’s hands?”) and gave him a couple of slaps. “Because we did that sort of thing in those days,” she added drily, to much laughter (and I thought about Sulekha being teasingly called a “Communist” because she carries her own bags from the bus in Chupke Chupke).

I had a very nice discussion with Sharmila Tagore and Balaji Vittal at the Kolkata Literary Meet on Jan 25. Sharmila ji was gracious as usual, and in a good mood too. One highlight: her recalling an incident during the Satyakam shoot near Jamshedpur where a bunch of youngsters tried to disrupt the shoot/generally misbehave. Dharmendra pulled one of them across by his collar, Sharmila ji told us (“and have you seen Dharam’s hands?”) and gave him a couple of slaps. “Because we did that sort of thing in those days,” she added drily, to much laughter (and I thought about Sulekha being teasingly called a “Communist” because she carries her own bags from the bus in Chupke Chupke).

Also, in response to an audience question about her famous bikini shoot in 1966: “I did it because I thought I looked good. One should do these things at the right time, no? I mean, there would be no point my wearing a bikini today.” Watching her on stage, and speaking with her before we went up, it was very hard to believe that this year marks the 50th anniversary of Anupama, An Evening in Paris and Nayak.

My favourite Sharmila moment though had nothing to do with the filmi discussion. It was just before we went up on stage when, right in the middle of an interview, she stopped, pointed at one of the Victoria Memorial’s stray pups sitting nearby, and asked if someone could give it some water because it looked thirsty and unwell.

The pic below is courtesy the Sorelle Grapevine blog, which also has a nice writeup about the session, plus a short video. See here.

---------------------

Got to sign copies of my three books at the little stall outside Victoria Memorial. It was nice to see The Popcorn Essayists there. (Treat this as a re-plug for an anthology containing some very good pieces by Anjum Hasan, Rajorshi Chakraborti, Namita Gokhale, Amitava Kumar, Kamila Shamsie, Sumana Roy, Manjula Padmanabhan, Madhulika Liddle, Sidin Vadukut, Manil Suri, Musharraf Ali Farooqi and Jaishree Misra.)

In this pic, the Popcorn Essayists, Jaane bhi do Yaaro and Hrishikesh Mukherjee can be seen in the company of many worthies, including Anirudha Bhattacharjee and Balaji Vittal’s two books, and Amitava Nag’s new book about Soumitra Chatterjee.

In this pic, the Popcorn Essayists, Jaane bhi do Yaaro and Hrishikesh Mukherjee can be seen in the company of many worthies, including Anirudha Bhattacharjee and Balaji Vittal’s two books, and Amitava Nag’s new book about Soumitra Chatterjee.------------------------------

Then there was the session with Javed Akhtar and Zoya Akhtar, which went off well, I’m told. (I can never judge these things while up on stage.) Javed-Saab was looking a bit like the angry young man the couple of times I ran into him in Jaipur (and later at the Kolkata airport, where people peremptorily came up and took selfies with him without even saying a proper hello, as if he were a wax statue or something) - but he was in good form at the Kalam session, especially when dealing with audience questions near the end.

------------------------

And here are pics from the sessions at the Jaipur Literature Festival, where Anuja Chauhan and I played musical chairs with the moderator’s seat. First, “The Craft of the Bestseller” with Anuja, Ravi Subramanian and the massively popular Ravinder Singh who continues to thrill crowds and readers despite his repeated admissions that he doesn’t read books himself. And then, “Jaane Kahaan Gaye Woh Din: New Books about Old Bollywood” with Rauf Ahmed and Anuja.

The video of the “Jaane Kahaan” session is here. At one point during the first half of the session, Rauf saab seemed to forget that the panel was only 45-50 minutes long (and that most of the audience would need some context for the inside references he was making to old-time movies and movie-stars), but Anuja deftly got things back on track, and I got to speak a bit too.

[Don’t have time at the moment to do detailed reports of any of the sessions, but will try at a future date]

Published on January 31, 2016 01:58

January 27, 2016

Little grown-ups, and other misfits

[Did this for my Forbes Life books column – around the time I was part of the jury for the children’s fiction prize at the Goodbooks Awards]

---------------------------------------

Discussions about literature for children and young adults often pivot around the question: should young readers be spoon-fed? Do messages and morals have to be spelt out? Some parents and teachers seem to think so, but there are others who give pre-teen readers more credit and point out that the best way to engage a mind – and to provoke some thought in the process – is to tell a story really well, to make the characters and situations involving. Ideas can lie embedded within a “fun” narrative. Besides, as the writer EB White once put it, “Children are the most attentive, curious, eager, observant, sensitive, quick, and generally congenial readers on earth. Anyone who writes down to them is wasting his time.” A related observation is that it makes little sense to shield children from “dark” subject matter, especially at a time when content of all sorts is so easy to access.

Having recently read a number of new young-adult (YA) books by Indian authors, I was pleased to find that many of them – some to a greater degree than others – steer clear of pedantry. Even the ones that are set in a school environment and deal with a vulnerable but intelligent child beginning to make sense of the world, working his way through notions of right and wrong, seeing a friend or classmate through fresh eyes and learning about empathy.

Having recently read a number of new young-adult (YA) books by Indian authors, I was pleased to find that many of them – some to a greater degree than others – steer clear of pedantry. Even the ones that are set in a school environment and deal with a vulnerable but intelligent child beginning to make sense of the world, working his way through notions of right and wrong, seeing a friend or classmate through fresh eyes and learning about empathy.

A good example of this is in Payal Dhar’s Slightly Burnt , which begins by cleverly misdirecting the reader: the narrator, a 16-year-old named Komal, has just had her life turned upside down, because her best friend Sahil (and she only wants them to be friends, nothing more) has said three little words to her. We think we know what those words are, but soon we discover that we were wrong; we then follow Komal on a journey to understanding and acceptance. I won’t provide big spoilers here, but this novel addresses an important subject – the marginalization of people who are unconventional in some way – with lightness. You won’t at all feel you are being preached to.

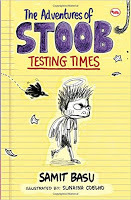

Which is also the case with Samit Basu’s delightful

The Adventures of Stoob: Testing Times

. If you’re in a solemn mood, you might tell someone that this book’s lesson is: It Isn’t Good to Cheat in Your Exams. But that wouldn’t begin to convey the strengths of this fluid narrative about a boy who has a rich inner life, and who is so nervous about his exams that he nearly crosses over to the dark side. In a smart demonstration that “doing the right thing” can be cool, some of the most fun passages have Stoob and his friends thinking up ways to prevent another friend from cheating during a test. The writing aside, I enjoyed Sunaina Coelho’s illustrations, which complement the text wonderfully – as in the drawing of Stoob being chased by weapon-wielding Hindi alphabets, or the hilarious one of him and his parents depicted as mythological characters from an old, melodramatic movie.

Which is also the case with Samit Basu’s delightful

The Adventures of Stoob: Testing Times

. If you’re in a solemn mood, you might tell someone that this book’s lesson is: It Isn’t Good to Cheat in Your Exams. But that wouldn’t begin to convey the strengths of this fluid narrative about a boy who has a rich inner life, and who is so nervous about his exams that he nearly crosses over to the dark side. In a smart demonstration that “doing the right thing” can be cool, some of the most fun passages have Stoob and his friends thinking up ways to prevent another friend from cheating during a test. The writing aside, I enjoyed Sunaina Coelho’s illustrations, which complement the text wonderfully – as in the drawing of Stoob being chased by weapon-wielding Hindi alphabets, or the hilarious one of him and his parents depicted as mythological characters from an old, melodramatic movie.

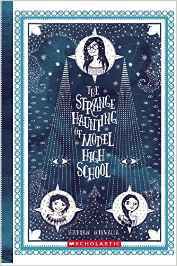

Another of my recent favourites in the school sub-genre was Shabnam Minwalla’s The Strange Haunting of Model High School . Though set in south Mumbai – with references to real-world landmarks such as Churchgate station – this book might remind you a little of Enid Blyton’s St Clare’s stories, with a supernatural twist thrown in. The characters here include a lonely girl-ghost who has been floating around the school’s corridors for over a hundred years seeking a piece of information that will put her mind at rest, a conniving deputy principal named Mrs Rangachari, and the three protagonists – BFFs named Lara, Mallika and Sunu – who set out to help the ghost even as they prepare for an inter-school production of the musical Annie.

One of the incidental themes in Minwalla’s novel – a less-privileged girl attending a posh school – is handled more directly, and a little more self-consciously, in Kate Darnton’s The Misfits , told from the perspective of an American girl named Chloe who has recently moved to Delhi with her parents. When Chloe encounters another misfit, the dark-skinned Lakshmi, who is very Indian but not of the “right class”, she gets an insight into the workings of the adult world, and gets to play savior as well. Darnton’s book is sensitive and engaging, but since it seems to have been written in part for a non-Indian readership, some of the content might feel over-expository, and just a teeny bit patronizing, to an Indian reader. (Chloe’s parents, who used to be hippies in their own youth, keep shaking their heads indignantly at the class prejudice they see around them.)

Another, breezier story about an 11-year-old girl is Judy Balan’s

How to Stop Your Grownup from Making Bad Decisions

, written as a series of blog entries by “Nina the Philosopher”. A few dramatic things happen here (Nina and her friend Aakash blow up the school swimming pool with stolen chemicals; her single mom has a serious accident and must also be kept from getting married to a seemingly unsuitable boy), but the overall tone is that of a chatty diary entry – Nina isn’t trying to write a thriller for us, she is simply going through life and negotiating things as they happen. In the process she shows the clear-sighted wisdom one might expect in an intelligent child, but which some adults might also envy. “People who THINK all the time should have their own rooms,” she observes, making a case for introverts who need a lot of space to themselves, even when they aren’t doing anything observably important.

Another, breezier story about an 11-year-old girl is Judy Balan’s

How to Stop Your Grownup from Making Bad Decisions

, written as a series of blog entries by “Nina the Philosopher”. A few dramatic things happen here (Nina and her friend Aakash blow up the school swimming pool with stolen chemicals; her single mom has a serious accident and must also be kept from getting married to a seemingly unsuitable boy), but the overall tone is that of a chatty diary entry – Nina isn’t trying to write a thriller for us, she is simply going through life and negotiating things as they happen. In the process she shows the clear-sighted wisdom one might expect in an intelligent child, but which some adults might also envy. “People who THINK all the time should have their own rooms,” she observes, making a case for introverts who need a lot of space to themselves, even when they aren’t doing anything observably important.

At one point, Nina says she feels like she is the grown-up and her mom the teenager in the house. A more literal version of this situation can be found in Andaleeb Wajid’s No Time for Goodbyes , which operates at the intersection of YA fantasy and teen romance: after glancing at a Polaroid photo, 16-year-old Tamanna finds herself back in 1982, where her future mom is a little younger than her, and where she has to pretend to be a visitor from Australia (while dodging questions such as why the Harry Potter book she has brought along has a “2000” publishing date). A nice nostalgia trip for those of us who remember the times Wajid is writing about, this is the first in a three-book series (the sequel, Back in Time, is out too), and I’d be interested in seeing how she manages to stretch out this one-note premise without getting too repetitive.

One thing she does well is to invoke the pang of knowing that the person you want to be with may always remain inaccessible or out of bounds – in this case, literally belonging to another dimension. Looked at that way, notwithstanding the time-travel angle, this book is about the very universal “outsider” emotions that are also evoked in real-world narratives like Slightly Burnt and The Misfits.

One thing she does well is to invoke the pang of knowing that the person you want to be with may always remain inaccessible or out of bounds – in this case, literally belonging to another dimension. Looked at that way, notwithstanding the time-travel angle, this book is about the very universal “outsider” emotions that are also evoked in real-world narratives like Slightly Burnt and The Misfits.

[Other recent posts on children's/young adult books: ; Tik-Tik, the Master of Time]

---------------------------------------

Discussions about literature for children and young adults often pivot around the question: should young readers be spoon-fed? Do messages and morals have to be spelt out? Some parents and teachers seem to think so, but there are others who give pre-teen readers more credit and point out that the best way to engage a mind – and to provoke some thought in the process – is to tell a story really well, to make the characters and situations involving. Ideas can lie embedded within a “fun” narrative. Besides, as the writer EB White once put it, “Children are the most attentive, curious, eager, observant, sensitive, quick, and generally congenial readers on earth. Anyone who writes down to them is wasting his time.” A related observation is that it makes little sense to shield children from “dark” subject matter, especially at a time when content of all sorts is so easy to access.

Having recently read a number of new young-adult (YA) books by Indian authors, I was pleased to find that many of them – some to a greater degree than others – steer clear of pedantry. Even the ones that are set in a school environment and deal with a vulnerable but intelligent child beginning to make sense of the world, working his way through notions of right and wrong, seeing a friend or classmate through fresh eyes and learning about empathy.

Having recently read a number of new young-adult (YA) books by Indian authors, I was pleased to find that many of them – some to a greater degree than others – steer clear of pedantry. Even the ones that are set in a school environment and deal with a vulnerable but intelligent child beginning to make sense of the world, working his way through notions of right and wrong, seeing a friend or classmate through fresh eyes and learning about empathy. A good example of this is in Payal Dhar’s Slightly Burnt , which begins by cleverly misdirecting the reader: the narrator, a 16-year-old named Komal, has just had her life turned upside down, because her best friend Sahil (and she only wants them to be friends, nothing more) has said three little words to her. We think we know what those words are, but soon we discover that we were wrong; we then follow Komal on a journey to understanding and acceptance. I won’t provide big spoilers here, but this novel addresses an important subject – the marginalization of people who are unconventional in some way – with lightness. You won’t at all feel you are being preached to.

Which is also the case with Samit Basu’s delightful

The Adventures of Stoob: Testing Times

. If you’re in a solemn mood, you might tell someone that this book’s lesson is: It Isn’t Good to Cheat in Your Exams. But that wouldn’t begin to convey the strengths of this fluid narrative about a boy who has a rich inner life, and who is so nervous about his exams that he nearly crosses over to the dark side. In a smart demonstration that “doing the right thing” can be cool, some of the most fun passages have Stoob and his friends thinking up ways to prevent another friend from cheating during a test. The writing aside, I enjoyed Sunaina Coelho’s illustrations, which complement the text wonderfully – as in the drawing of Stoob being chased by weapon-wielding Hindi alphabets, or the hilarious one of him and his parents depicted as mythological characters from an old, melodramatic movie.

Which is also the case with Samit Basu’s delightful

The Adventures of Stoob: Testing Times

. If you’re in a solemn mood, you might tell someone that this book’s lesson is: It Isn’t Good to Cheat in Your Exams. But that wouldn’t begin to convey the strengths of this fluid narrative about a boy who has a rich inner life, and who is so nervous about his exams that he nearly crosses over to the dark side. In a smart demonstration that “doing the right thing” can be cool, some of the most fun passages have Stoob and his friends thinking up ways to prevent another friend from cheating during a test. The writing aside, I enjoyed Sunaina Coelho’s illustrations, which complement the text wonderfully – as in the drawing of Stoob being chased by weapon-wielding Hindi alphabets, or the hilarious one of him and his parents depicted as mythological characters from an old, melodramatic movie.Another of my recent favourites in the school sub-genre was Shabnam Minwalla’s The Strange Haunting of Model High School . Though set in south Mumbai – with references to real-world landmarks such as Churchgate station – this book might remind you a little of Enid Blyton’s St Clare’s stories, with a supernatural twist thrown in. The characters here include a lonely girl-ghost who has been floating around the school’s corridors for over a hundred years seeking a piece of information that will put her mind at rest, a conniving deputy principal named Mrs Rangachari, and the three protagonists – BFFs named Lara, Mallika and Sunu – who set out to help the ghost even as they prepare for an inter-school production of the musical Annie.

One of the incidental themes in Minwalla’s novel – a less-privileged girl attending a posh school – is handled more directly, and a little more self-consciously, in Kate Darnton’s The Misfits , told from the perspective of an American girl named Chloe who has recently moved to Delhi with her parents. When Chloe encounters another misfit, the dark-skinned Lakshmi, who is very Indian but not of the “right class”, she gets an insight into the workings of the adult world, and gets to play savior as well. Darnton’s book is sensitive and engaging, but since it seems to have been written in part for a non-Indian readership, some of the content might feel over-expository, and just a teeny bit patronizing, to an Indian reader. (Chloe’s parents, who used to be hippies in their own youth, keep shaking their heads indignantly at the class prejudice they see around them.)

Another, breezier story about an 11-year-old girl is Judy Balan’s

How to Stop Your Grownup from Making Bad Decisions

, written as a series of blog entries by “Nina the Philosopher”. A few dramatic things happen here (Nina and her friend Aakash blow up the school swimming pool with stolen chemicals; her single mom has a serious accident and must also be kept from getting married to a seemingly unsuitable boy), but the overall tone is that of a chatty diary entry – Nina isn’t trying to write a thriller for us, she is simply going through life and negotiating things as they happen. In the process she shows the clear-sighted wisdom one might expect in an intelligent child, but which some adults might also envy. “People who THINK all the time should have their own rooms,” she observes, making a case for introverts who need a lot of space to themselves, even when they aren’t doing anything observably important.

Another, breezier story about an 11-year-old girl is Judy Balan’s

How to Stop Your Grownup from Making Bad Decisions

, written as a series of blog entries by “Nina the Philosopher”. A few dramatic things happen here (Nina and her friend Aakash blow up the school swimming pool with stolen chemicals; her single mom has a serious accident and must also be kept from getting married to a seemingly unsuitable boy), but the overall tone is that of a chatty diary entry – Nina isn’t trying to write a thriller for us, she is simply going through life and negotiating things as they happen. In the process she shows the clear-sighted wisdom one might expect in an intelligent child, but which some adults might also envy. “People who THINK all the time should have their own rooms,” she observes, making a case for introverts who need a lot of space to themselves, even when they aren’t doing anything observably important. At one point, Nina says she feels like she is the grown-up and her mom the teenager in the house. A more literal version of this situation can be found in Andaleeb Wajid’s No Time for Goodbyes , which operates at the intersection of YA fantasy and teen romance: after glancing at a Polaroid photo, 16-year-old Tamanna finds herself back in 1982, where her future mom is a little younger than her, and where she has to pretend to be a visitor from Australia (while dodging questions such as why the Harry Potter book she has brought along has a “2000” publishing date). A nice nostalgia trip for those of us who remember the times Wajid is writing about, this is the first in a three-book series (the sequel, Back in Time, is out too), and I’d be interested in seeing how she manages to stretch out this one-note premise without getting too repetitive.

One thing she does well is to invoke the pang of knowing that the person you want to be with may always remain inaccessible or out of bounds – in this case, literally belonging to another dimension. Looked at that way, notwithstanding the time-travel angle, this book is about the very universal “outsider” emotions that are also evoked in real-world narratives like Slightly Burnt and The Misfits.

One thing she does well is to invoke the pang of knowing that the person you want to be with may always remain inaccessible or out of bounds – in this case, literally belonging to another dimension. Looked at that way, notwithstanding the time-travel angle, this book is about the very universal “outsider” emotions that are also evoked in real-world narratives like Slightly Burnt and The Misfits.[Other recent posts on children's/young adult books: ; Tik-Tik, the Master of Time]

Published on January 27, 2016 06:35

January 16, 2016

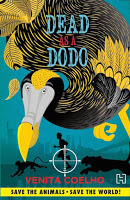

Children's book awards: Dead as a Dodo and other winners

The Hindu Young World-Goodbooks Awards for children’s books were announced yesterday at the Lit for Life festival in Chennai. Manjula Padmanabhan, Anil Menon and I were the jury for the fiction category, and after some fun email exchanges we gave the prize to Venita Coelho’s wonderful

Dead as a Dodo

, a travel-adventure in which three special agents (a human, a tiger and an overenthusiastic monkey) set out to rescue the world's last surviving dodo. But I’d also strongly recommend the other books on the shortlist: Mohit Parikh’s Manan

The Hindu Young World-Goodbooks Awards for children’s books were announced yesterday at the Lit for Life festival in Chennai. Manjula Padmanabhan, Anil Menon and I were the jury for the fiction category, and after some fun email exchanges we gave the prize to Venita Coelho’s wonderful

Dead as a Dodo

, a travel-adventure in which three special agents (a human, a tiger and an overenthusiastic monkey) set out to rescue the world's last surviving dodo. But I’d also strongly recommend the other books on the shortlist: Mohit Parikh’s Manan

(which I wrote about ), Mathangi Subramanian’s

Dear Mrs Naidu

and Samit Basu’s

The Adventures of Stoob: Testing Times

. Plus another book I enjoyed hugely while I was reading the initial list of submissions: Shabnam Minwalla’s

The Strange Haunting of Model High School

.

(which I wrote about ), Mathangi Subramanian’s

Dear Mrs Naidu

and Samit Basu’s

The Adventures of Stoob: Testing Times

. Plus another book I enjoyed hugely while I was reading the initial list of submissions: Shabnam Minwalla’s

The Strange Haunting of Model High School

.

Published on January 16, 2016 19:32

January 15, 2016

Ghosts and projections, in Wazir and other films

[My latest Mint Lounge film column]

If you haven’t watched Bejoy Nambiar’s Wazir yet and intend to, you may want to skip this column for now. (I’m not convinced a spoiler alert is really needed, but possibly I’m overestimating your deductive skills.)

At the halfway point, the title character – a goon hired by a minister to strong-arm people – makes his showy appearance. Or… he doesn’t. Because we subsequently learn that Wazir never existed: he was fabricated by master strategist Omkarnath Dhar (Amitabh Bachchan) as part of a convoluted, and very improbable, revenge plan. In the flashback that accompanied Omkarnath’s story about being attacked late at night, we saw Wazir all right (and gawped at Neil Nitin Mukesh’s scenery-chewing in the role), but now it turns out that the whole scene was a lie. Which means that in a sense, our eyes – with the movie camera as their guiding spirit – had played us false.

The scene got me thinking about other such sequences – where we are shown a person who doesn’t exist, or an incident that never took place – and to what degree they might be said to have misled the viewer. After all, film is a powerful and persuasive medium; once you have seen something on a screen, it is difficult to “un-see” it.

The scene got me thinking about other such sequences – where we are shown a person who doesn’t exist, or an incident that never took place – and to what degree they might be said to have misled the viewer. After all, film is a powerful and persuasive medium; once you have seen something on a screen, it is difficult to “un-see” it.

The conundrum of the unreliable flashback, for instance, goes back a long way. In 1950, Alfred Hitchcock’s Stage Fright earned some notoriety for a flashback scene that turned out to be a murderer’s false account. While many viewers and critics felt cheated (and Hitchcock himself conceded the point during an interview with Francois Truffaut), defenders of the film felt the device was justifiable: when a person creates a cover-up story, he internalises his own lies, and that is what the viewers were shown in this case.