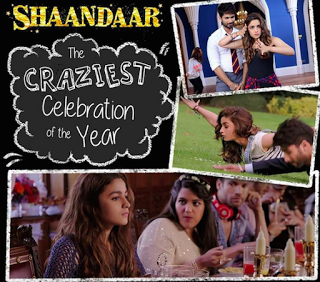

In defence of Vikas Bahl's delightfully zany Shaandaar

[Did this review for Mint Lounge]

It may be an understatement to say that Vikas Bahl’s madcap new film Shaandaar will confound or annoy many viewers. Twenty minutes in, I didn’t think it would be to my taste. The charming little animated flashback sequence that opens the film – about a man adopting a little girl and bringing her to his castle – is followed immediately by eye-popping set design (we are back in live-action mode, but only just), loud humour and a stream of apparent stereotypes including a “Fundvani” – a Sindhi with bling – toting a golden gun alongside a Big Moose-like kid brother who has to be married into a wealthy family.

My initial misgivings were soon dispelled though. After watching Shaandaar and thoroughly enjoying most of it, I felt like this film has the cult-following potential of Shaad Ali’s opulent narrative-musical Jhoom Barabar Jhoom (which has polarized audiences spectacularly – those who love it really, really love it), Anurag Kashyap’s No Smoking, or even Pankaj Advani’s Sankat City (which hasn’t developed a cult following yet, so maybe I shouldn’t include it in this list). All those films are deliriously over the top in places, and necessarily take the risks that come with stepping into that territory. Watching them, I was reminded – to varying degrees – of what Roger Ebert wrote in the context of the 2000 film The Cell:

In this fable, when the prince (a wedding planner named Jagjinder Joginder or JJ, played by Shahid Kapoor) tries to gallantly rescue the kooky “princess” Alia (Alia Bhatt), it turns out he has misjudged the situation and she is only skinny-dipping late at night. Instead of waking up Snow White – freeing her from malice-induced slumber – JJ must cure her insomnia and get her to sleep (he also cures himself in the process). Along the way they have a mock light-sabre fight to the tune of “Eena Meena Deeka”. Meanwhile an old witch, played by Sushma Seth, gorges on aaloo-paratha while hired sopranos stand by the dining table singing about sundried tomatoes. (Please, don’t let anyone tell you that THAT scene is unrealistic or over the top, it isn’t: I have been to richie-rich NRI weddings in London, and I know.) There is even a frog who gets a kiss, but resolutely stays a frog.

In this fable, when the prince (a wedding planner named Jagjinder Joginder or JJ, played by Shahid Kapoor) tries to gallantly rescue the kooky “princess” Alia (Alia Bhatt), it turns out he has misjudged the situation and she is only skinny-dipping late at night. Instead of waking up Snow White – freeing her from malice-induced slumber – JJ must cure her insomnia and get her to sleep (he also cures himself in the process). Along the way they have a mock light-sabre fight to the tune of “Eena Meena Deeka”. Meanwhile an old witch, played by Sushma Seth, gorges on aaloo-paratha while hired sopranos stand by the dining table singing about sundried tomatoes. (Please, don’t let anyone tell you that THAT scene is unrealistic or over the top, it isn’t: I have been to richie-rich NRI weddings in London, and I know.) There is even a frog who gets a kiss, but resolutely stays a frog.

Shaandaar doesn’t just play with fairytale archetypes though – it does amusing things with our expectations from certain dramatic tropes of Hindi cinema. While it has situations that may remind you of Bimal Roy’s Sujata (which also featured a cartoon scene involving the inner world of a “beti-jaisi” girl) and Shekhar Kapur’s Masoom (the connection is underlined by a Naseeruddin Shah voiceover), it steers away from the arcs we associate with those narratives.

Just one example: the intermission comes at a point where you expect something like conventional drama to occur after the break. A secret has just tumbled out of a closet, a father must come clean to his daughter about the past; ah, you tell yourself, THIS is where the fun and zaniness will stop, at least for a while, and things will get heavy.

Well, no such thing happens – after the break, as the dad starts telling his story, the film zips back into animated mode with a goofy scene that is a nod to Top Gun, of all things (while also being a reminder of what a different sort of person the dad once was, and how he was made to conform by his family). In other words, the timing and manner of the interval is predictable, but what follows is not. And after the big reveal, you have the wild-child hooting “Main naajaayiz hoon!” (“I’m illegitimate!”) – that’s even cooler than just being adopted, which is what she thought she was all this time. I have a feeling we’re no longer in Sujata Land, would be a mild way of describing this moment.

(And no, none of the above is really a spoiler.)

In its own way, Shaandaar deals with the oldest of subjects: the shifting equations between love and practicality, independence and materialism; the possessiveness of parents. (Its “message” – be your own person, don’t let others dictate how you should live your life – could be written on the head of a pin, as Orson Welles once said most movie messages could.) But I wasn’t consciously thinking about those things while the film was on – I was delighting in the many wacky touches, such as the operatic musical numbers: that mushroom interlude, which plays like a Peter Gabriel or Depeche Mode music video of the 1980s; or the hilarious qawwali that goes from being a standard jugalbandhi between men and women to a show of sexist nastiness to a sensitizing lesson, and finally a brazen display of hypocrisy that is often part and parcel of the arranged marriage system anyway. Particularly enjoyable here is Vikas Verma’s performance as the chauvinistic Robin (though it might be giving him too much “agency” to call him chauvinistic, since his brain resides in his eight-pack abs), the macho-seeming rich kid who coos “Yes bro!” every few seconds but turns into a sniveling wreck, blubbering in his mother tongue, when he gets locked up in an English prison.

There are some missteps and slack moments, of course – including, oddly enough, the Karan Johar cameo for a “Mehndi with Karan” show. But on the whole this is dynamic storytelling with unexpected flashes of warmth, and you get the sense that everyone had a lot of fun doing it, while possibly wondering exactly WHAT they were doing. And that puts me in mind of the things the crew members of Kundan Shah’s Jaane bhi do Yaaro told me years ago: the whole process was so self-contained, we weren’t even thinking of this as a film that might get released and seen by people, we were just having a ball with the strangest situations we had ever seen in a script.

And no, I don’t think it’s frivolous to cite an iconic, much-canonized film like JBDY as a reference point for Shaandaar. The 1983 comedy was so obviously trying to break the mould that many viewers – then and now – have been happy to overlook its little deficiencies, from the tackiness of some of the shot-taking to the fact that a lot of it (including parts of the celebrated Mahabharata scene) simply hasn’t dated well.

It’s a difficult business to make a truly lunatic, truly spaced out film. So much can go wrong, or seem forced; a movie that combines comedy with social commentary might easily stumble into pedantry. Even a Jaane bhi do Yaaro has that moment – the press conference on the roof of a skyscraper – where the madness is halted in its tracks to deliver what amounts to voiceover commentary about the pitiable state of the common man.

That scene was saved – sort of – by the presence of Pankaj Kapur, who maintained a loony tone even as his character, the evil Tarneja, stammered through a story about feeling angry when he saw a bully slapping a blind man. And Kapur is in Shaandaar too, having a fine old time as Alia’s dad.

In fact, it may be worth reminding ourselves just how often Kapur – usually described as a serious actor, with all the straitjacketing implied by that term– has appeared in crazy films, and to fine effect at that. When he made his glorious “comeback” in Maqbool in a very menacing part, after being under the radar for many years, and then followed it up with great performances in films like The Blue Umbrella and Dharm, one wasn’t associating him with craziness; one was thinking less about Karamchand the carrot-chewing detective and more about the soulful performer in realistic settings in films like Ek Doctor ki Maut. But consider the Serious Actor’s filmography. There is JBDY, and there are two films that were made on the heels of JBDY, by members of the same unit, and in a similar spirit: Saeed Mirza’s Mohan Joshi Haazir Ho (in which Kapur had a small part as a suited-booted, proto-Matrix, automaton-like “promoter”) and Vinod Chopra’s meta-film Khamosh.

In fact, it may be worth reminding ourselves just how often Kapur – usually described as a serious actor, with all the straitjacketing implied by that term– has appeared in crazy films, and to fine effect at that. When he made his glorious “comeback” in Maqbool in a very menacing part, after being under the radar for many years, and then followed it up with great performances in films like The Blue Umbrella and Dharm, one wasn’t associating him with craziness; one was thinking less about Karamchand the carrot-chewing detective and more about the soulful performer in realistic settings in films like Ek Doctor ki Maut. But consider the Serious Actor’s filmography. There is JBDY, and there are two films that were made on the heels of JBDY, by members of the same unit, and in a similar spirit: Saeed Mirza’s Mohan Joshi Haazir Ho (in which Kapur had a small part as a suited-booted, proto-Matrix, automaton-like “promoter”) and Vinod Chopra’s meta-film Khamosh.

More recently there has been Vishal Bhardwaj’s Matru ki Bijli ka Mandola, the broad plot framework of which is similar to Shaandaar’s. Both films hinge on a nutty father-daughter pair (with Kapur as the dad in each case, hallucinating about pink buffaloes in one film, terrorizing someone with a “haunted” wheelchair in this one) and the arrival of a young messiah who briefly threatens the relationship but ends up setting things right (or as “right” as they can get in a story where a new twist can arrive at any time). And both films have Kapur in a flying machine near the end. I can totally picture him swooping down from the rafters and growling “Durachaari! Bhrashtachaari! Bol sorry!” at all those viewers who don’t submit to Shaandaar’s charms.

---------------------------

<!-- /* Font Definitions */ @font-face {font-family:"Cambria Math"; panose-1:0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0; mso-font-charset:1; mso-generic-font-family:roman; mso-font-format:other; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:0 0 0 0 0 0;} @font-face {font-family:Calibri; panose-1:2 15 5 2 2 2 4 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1073786111 1 0 415 0;} /* Style Definitions */ p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-parent:""; margin:0cm; margin-bottom:.0001pt; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;} .MsoChpDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; mso-default-props:yes; font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;} @page WordSection1 {size:612.0pt 792.0pt; margin:72.0pt 72.0pt 72.0pt 72.0pt; mso-header-margin:36.0pt; mso-footer-margin:36.0pt; mso-paper-source:0;} div.WordSection1 {page:WordSection1;} </style></span></span></div>--> <div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-size: large;"><span style="font-family: Times,"Times New Roman",serif;"><span style="font-family: Times,"Times New Roman",serif;"><b>P.S.</b>Some of the bordering-on-tedious slapstick comedy in <i>Shaandaar</i>’s first 20 minutes includes a cutesy scene between Kapur and his real-life son Shahid, where the former calls the latter “ullu ka patthaa” and you roll your eyes, thinking here we are again, stuck in Bollywood’s incestuous little circle; here begins the self-referencing and the bhai-chaara. And this does happen, to a degree, but then, even <i>Jaane bhi do Yaaro</i>had inside jokes like “Albert Pinto ko Gussa Kyon Aata Hai?” and “Antonioni Park”. Perhaps we have reached a post-post-modernist stage in film history where it should be possible to assess a film independently of the nudge-wink jokes contained in it; to simply take those things as a given.</span></span></span></div><span style="font-size: large;"><span style="font-family: Times,"Times New Roman",serif;"> </span></span>

It may be an understatement to say that Vikas Bahl’s madcap new film Shaandaar will confound or annoy many viewers. Twenty minutes in, I didn’t think it would be to my taste. The charming little animated flashback sequence that opens the film – about a man adopting a little girl and bringing her to his castle – is followed immediately by eye-popping set design (we are back in live-action mode, but only just), loud humour and a stream of apparent stereotypes including a “Fundvani” – a Sindhi with bling – toting a golden gun alongside a Big Moose-like kid brother who has to be married into a wealthy family.

My initial misgivings were soon dispelled though. After watching Shaandaar and thoroughly enjoying most of it, I felt like this film has the cult-following potential of Shaad Ali’s opulent narrative-musical Jhoom Barabar Jhoom (which has polarized audiences spectacularly – those who love it really, really love it), Anurag Kashyap’s No Smoking, or even Pankaj Advani’s Sankat City (which hasn’t developed a cult following yet, so maybe I shouldn’t include it in this list). All those films are deliriously over the top in places, and necessarily take the risks that come with stepping into that territory. Watching them, I was reminded – to varying degrees – of what Roger Ebert wrote in the context of the 2000 film The Cell:

The Cell is one of those movies where you have a lot of doubts at the beginning, and then one by one they're answered, and you find yourself seduced by the style and story […]We live in a time when Hollywood shyly ejects weekly remakes of dependable plots, terrified to include anything that might confuse the dullest audience member […] Into this wilderness comes a movie which is challenging, wildly ambitious and technically superb, and I dunno: I guess it just overloads the circuits for some people.One problem with Shaandaar was its pre-publicity: what turns out to be an audacious, energetic movie came with the dullest, most constricting promotional tagline imaginable. “India’s first destination wedding film”, it said. The trailers and the information that the shoot was in Leeds combined to give the impression that this film would do for British castle tourism what Zindagi na Milegi Dobaara did for Spain, and pretty much ensured that a viewer was unprepared for what Shaandaar really is: it isn’t just a fairytale – which is the first, most obvious observation to be made about it – but a revisionist fairytale on steroids (or magic mushrooms, to reference perhaps the film’s strangest scene); it belongs in the tradition of the Red Riding Hood retellings where the heroine gives the big bad wolf a kick in the seat of his pants.

In this fable, when the prince (a wedding planner named Jagjinder Joginder or JJ, played by Shahid Kapoor) tries to gallantly rescue the kooky “princess” Alia (Alia Bhatt), it turns out he has misjudged the situation and she is only skinny-dipping late at night. Instead of waking up Snow White – freeing her from malice-induced slumber – JJ must cure her insomnia and get her to sleep (he also cures himself in the process). Along the way they have a mock light-sabre fight to the tune of “Eena Meena Deeka”. Meanwhile an old witch, played by Sushma Seth, gorges on aaloo-paratha while hired sopranos stand by the dining table singing about sundried tomatoes. (Please, don’t let anyone tell you that THAT scene is unrealistic or over the top, it isn’t: I have been to richie-rich NRI weddings in London, and I know.) There is even a frog who gets a kiss, but resolutely stays a frog.

In this fable, when the prince (a wedding planner named Jagjinder Joginder or JJ, played by Shahid Kapoor) tries to gallantly rescue the kooky “princess” Alia (Alia Bhatt), it turns out he has misjudged the situation and she is only skinny-dipping late at night. Instead of waking up Snow White – freeing her from malice-induced slumber – JJ must cure her insomnia and get her to sleep (he also cures himself in the process). Along the way they have a mock light-sabre fight to the tune of “Eena Meena Deeka”. Meanwhile an old witch, played by Sushma Seth, gorges on aaloo-paratha while hired sopranos stand by the dining table singing about sundried tomatoes. (Please, don’t let anyone tell you that THAT scene is unrealistic or over the top, it isn’t: I have been to richie-rich NRI weddings in London, and I know.) There is even a frog who gets a kiss, but resolutely stays a frog.Shaandaar doesn’t just play with fairytale archetypes though – it does amusing things with our expectations from certain dramatic tropes of Hindi cinema. While it has situations that may remind you of Bimal Roy’s Sujata (which also featured a cartoon scene involving the inner world of a “beti-jaisi” girl) and Shekhar Kapur’s Masoom (the connection is underlined by a Naseeruddin Shah voiceover), it steers away from the arcs we associate with those narratives.

Just one example: the intermission comes at a point where you expect something like conventional drama to occur after the break. A secret has just tumbled out of a closet, a father must come clean to his daughter about the past; ah, you tell yourself, THIS is where the fun and zaniness will stop, at least for a while, and things will get heavy.

Well, no such thing happens – after the break, as the dad starts telling his story, the film zips back into animated mode with a goofy scene that is a nod to Top Gun, of all things (while also being a reminder of what a different sort of person the dad once was, and how he was made to conform by his family). In other words, the timing and manner of the interval is predictable, but what follows is not. And after the big reveal, you have the wild-child hooting “Main naajaayiz hoon!” (“I’m illegitimate!”) – that’s even cooler than just being adopted, which is what she thought she was all this time. I have a feeling we’re no longer in Sujata Land, would be a mild way of describing this moment.

(And no, none of the above is really a spoiler.)

In its own way, Shaandaar deals with the oldest of subjects: the shifting equations between love and practicality, independence and materialism; the possessiveness of parents. (Its “message” – be your own person, don’t let others dictate how you should live your life – could be written on the head of a pin, as Orson Welles once said most movie messages could.) But I wasn’t consciously thinking about those things while the film was on – I was delighting in the many wacky touches, such as the operatic musical numbers: that mushroom interlude, which plays like a Peter Gabriel or Depeche Mode music video of the 1980s; or the hilarious qawwali that goes from being a standard jugalbandhi between men and women to a show of sexist nastiness to a sensitizing lesson, and finally a brazen display of hypocrisy that is often part and parcel of the arranged marriage system anyway. Particularly enjoyable here is Vikas Verma’s performance as the chauvinistic Robin (though it might be giving him too much “agency” to call him chauvinistic, since his brain resides in his eight-pack abs), the macho-seeming rich kid who coos “Yes bro!” every few seconds but turns into a sniveling wreck, blubbering in his mother tongue, when he gets locked up in an English prison.

There are some missteps and slack moments, of course – including, oddly enough, the Karan Johar cameo for a “Mehndi with Karan” show. But on the whole this is dynamic storytelling with unexpected flashes of warmth, and you get the sense that everyone had a lot of fun doing it, while possibly wondering exactly WHAT they were doing. And that puts me in mind of the things the crew members of Kundan Shah’s Jaane bhi do Yaaro told me years ago: the whole process was so self-contained, we weren’t even thinking of this as a film that might get released and seen by people, we were just having a ball with the strangest situations we had ever seen in a script.

And no, I don’t think it’s frivolous to cite an iconic, much-canonized film like JBDY as a reference point for Shaandaar. The 1983 comedy was so obviously trying to break the mould that many viewers – then and now – have been happy to overlook its little deficiencies, from the tackiness of some of the shot-taking to the fact that a lot of it (including parts of the celebrated Mahabharata scene) simply hasn’t dated well.

It’s a difficult business to make a truly lunatic, truly spaced out film. So much can go wrong, or seem forced; a movie that combines comedy with social commentary might easily stumble into pedantry. Even a Jaane bhi do Yaaro has that moment – the press conference on the roof of a skyscraper – where the madness is halted in its tracks to deliver what amounts to voiceover commentary about the pitiable state of the common man.

That scene was saved – sort of – by the presence of Pankaj Kapur, who maintained a loony tone even as his character, the evil Tarneja, stammered through a story about feeling angry when he saw a bully slapping a blind man. And Kapur is in Shaandaar too, having a fine old time as Alia’s dad.

In fact, it may be worth reminding ourselves just how often Kapur – usually described as a serious actor, with all the straitjacketing implied by that term– has appeared in crazy films, and to fine effect at that. When he made his glorious “comeback” in Maqbool in a very menacing part, after being under the radar for many years, and then followed it up with great performances in films like The Blue Umbrella and Dharm, one wasn’t associating him with craziness; one was thinking less about Karamchand the carrot-chewing detective and more about the soulful performer in realistic settings in films like Ek Doctor ki Maut. But consider the Serious Actor’s filmography. There is JBDY, and there are two films that were made on the heels of JBDY, by members of the same unit, and in a similar spirit: Saeed Mirza’s Mohan Joshi Haazir Ho (in which Kapur had a small part as a suited-booted, proto-Matrix, automaton-like “promoter”) and Vinod Chopra’s meta-film Khamosh.

In fact, it may be worth reminding ourselves just how often Kapur – usually described as a serious actor, with all the straitjacketing implied by that term– has appeared in crazy films, and to fine effect at that. When he made his glorious “comeback” in Maqbool in a very menacing part, after being under the radar for many years, and then followed it up with great performances in films like The Blue Umbrella and Dharm, one wasn’t associating him with craziness; one was thinking less about Karamchand the carrot-chewing detective and more about the soulful performer in realistic settings in films like Ek Doctor ki Maut. But consider the Serious Actor’s filmography. There is JBDY, and there are two films that were made on the heels of JBDY, by members of the same unit, and in a similar spirit: Saeed Mirza’s Mohan Joshi Haazir Ho (in which Kapur had a small part as a suited-booted, proto-Matrix, automaton-like “promoter”) and Vinod Chopra’s meta-film Khamosh.More recently there has been Vishal Bhardwaj’s Matru ki Bijli ka Mandola, the broad plot framework of which is similar to Shaandaar’s. Both films hinge on a nutty father-daughter pair (with Kapur as the dad in each case, hallucinating about pink buffaloes in one film, terrorizing someone with a “haunted” wheelchair in this one) and the arrival of a young messiah who briefly threatens the relationship but ends up setting things right (or as “right” as they can get in a story where a new twist can arrive at any time). And both films have Kapur in a flying machine near the end. I can totally picture him swooping down from the rafters and growling “Durachaari! Bhrashtachaari! Bol sorry!” at all those viewers who don’t submit to Shaandaar’s charms.

---------------------------

<!-- /* Font Definitions */ @font-face {font-family:"Cambria Math"; panose-1:0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0; mso-font-charset:1; mso-generic-font-family:roman; mso-font-format:other; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:0 0 0 0 0 0;} @font-face {font-family:Calibri; panose-1:2 15 5 2 2 2 4 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1073786111 1 0 415 0;} /* Style Definitions */ p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-parent:""; margin:0cm; margin-bottom:.0001pt; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;} .MsoChpDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; mso-default-props:yes; font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;} @page WordSection1 {size:612.0pt 792.0pt; margin:72.0pt 72.0pt 72.0pt 72.0pt; mso-header-margin:36.0pt; mso-footer-margin:36.0pt; mso-paper-source:0;} div.WordSection1 {page:WordSection1;} </style></span></span></div>--> <div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-size: large;"><span style="font-family: Times,"Times New Roman",serif;"><span style="font-family: Times,"Times New Roman",serif;"><b>P.S.</b>Some of the bordering-on-tedious slapstick comedy in <i>Shaandaar</i>’s first 20 minutes includes a cutesy scene between Kapur and his real-life son Shahid, where the former calls the latter “ullu ka patthaa” and you roll your eyes, thinking here we are again, stuck in Bollywood’s incestuous little circle; here begins the self-referencing and the bhai-chaara. And this does happen, to a degree, but then, even <i>Jaane bhi do Yaaro</i>had inside jokes like “Albert Pinto ko Gussa Kyon Aata Hai?” and “Antonioni Park”. Perhaps we have reached a post-post-modernist stage in film history where it should be possible to assess a film independently of the nudge-wink jokes contained in it; to simply take those things as a given.</span></span></span></div><span style="font-size: large;"><span style="font-family: Times,"Times New Roman",serif;"> </span></span>

Published on October 23, 2015 23:14

No comments have been added yet.

Jai Arjun Singh's Blog

- Jai Arjun Singh's profile

- 11 followers

Jai Arjun Singh isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.