Weston Cutter's Blog, page 19

August 5, 2013

Anton DiScalafani’s “The Yonahlossee Riding Camp for Girls”

The Yonahlossee Riding Camp for Girls by Anton DiScalafani

THE YONAHLOSSEE RIDING CAMP FOR GIRLS by Anton DiScalafani

It was bad. It was so bad. Oh gosh, there were so many problems in this book, maybe the easiest to start with is this: it’s a period-piece, set in the Great Depression and on the cover, there’s a photo of a girl in a ‘60s tuckered blouse and Capri-cut jeans smoking a cigarette. Nowhere in this novel does Thea, the novel’s main character, smoke, wear jeans or live within years of the 1960’s.

Of course, don’t judge a book by its cover, but unfortunately, the inside is even more painful. At the beginning of the novel, I couldn’t tell if I was reading Young-Adult or not. I kept going, thinking whatever, that’s fine if this book is marketed to teen girls, all right. But then it very rapidly becomes obvious that this is NOT for young girls as soon as the story devolves into way over-descript sex scenes. Not that the writing matures to match the content.

The novel starts with Thea Atwell’s parents dropping her off at the Yonahlossee Riding Camp for girls in the Blue Ridge Mountains. First-person narrative Thea painful foreshadows that she has done something horrible, which is why her parents are kicking her out of her Florida home, the only place she has ever known, and abandoning her at this boarding-school/camp. Luckily enough, she’s already in a tie for position of “best rider of the entire school,” basically as soon as she gets there, and she becomes BFF with a girl named Sissy instantly, so camp is just fine. Oh, and she goes through coming-of-age feelings being around so many other girls for a while.

Throughout the days at camp, Thea goes into long-flashbacks of her life back in Florida, her carefree-days with her gentle twin brother (who, maturity-wise, is like 4 years her junior) and her cousin-so-close-he-was-a-brother, as she so often refers to him, Georgie. Flashbacks of her days usually consist of Thea fondly remembering her horse and waiting for her cousin to visit so the two of them could sneak into barns or around the yard and fool around. I’m of the opinion that the words “cousin” and “penis” should never be in the same sentence, but DiScalafani is definitely not on the same page. There’s more foreshadowing in these flashbacks that the reason she got sent away was because of more than her just sleeping with Georgie.

Then there’s the days at camp, where Thea is just the greatest rider (and even wins the big competition!), which of course attracts the attention of the handsome Mr. Holmes, a co-owner of the camp. The other co-owner is Mrs. Holmes, his wife and the mother of his three beautiful daughters. Naturally, Thea and Mr. Holmes hook up repeatedly while the Mrs. is away trying to raise money to keep the camp afloat. Apparently the whole affair with Georgie didn’t teach her the consequences of sex.

Besides the fact that she’s having an affair with a married man twice her age, I have so many problems with the writing in this part. 1. DiScalafani’s Thea subscribes to the imaginary porn-esque idea that a girl doesn’t realize she is pretty until a guy sticks something in her. I’ve never met this girl in real life and am disappointed a female author would make a character like this. 2. Throughout the way over-descript sex scenes, there are horrible, horrible metaphors about Thea’s body rearing and bucking like a horse. 3. When the affair ends, and basically, when the novel ends, Thea has learned nothing. No major discovery. Basically, all that’s happened is she’s come of age because now, instead of having illicit affairs with boys and relatives, she’s moved on to having illicit relations with Men.

A fair question right now: why did I even continue to read this book? I guess it’s kind of like watching an accident happen, like watching someone about to trip and you want to stop it, but you know it’s already too late and you can’t, so you just painful watch her fall over. And like I mentioned earlier, it’s basically YA-level writing, so it’s an easy read and you can very quickly go from “Oh my God, she is NOT going to do that,” to “You idiot.” Maybe if you are interested in 1. Southern Decorum 2. Horse-back riding and metaphors or 3. Girls getting their V-cards cashed with inappropriate men, you might like this book. In my case, I couldn’t care less about any of those things, or subsequently, anything else DiScalafani is going to write next.

July 29, 2013

Fiona Maazel’s WOKE UP LONELY

Woke Up Lonely by Fiona Maazel

Woke Up Lonely by Fiona Maazel

I joined Twitter this spring because I don’t remember quite why, it seemed like a good idea, and for those of us whose nerdery tends bookward our Twitter-feeds are odd places as books come out—suddenly authors we’ve never heard of before (but whose publisher we’ve friended because said publisher is among the very greatest in the country) are everything in the Twitter-feed and we’re like: wha? That, anyway, was my experience this spring with Fiona Maazel‘s Woke Up Lonely, and I’m grateful to have joined Twitter if for no other reason than that I was hit over and over by Maazel’s name, and the title of her latest (and plus then there’s the fun part, which is actually *reading* the book, and going: holy shit, all those people on Twitter were totally right). It’s all good fun.

Which phrase—it’s good fun—I’d like to apply to Woke Up Lonely, which is true enough, in its way: the novel’s as fun as anything I’ve read in I don’t know how long. Quite awhile. But the novel’s much, much more than mere good fun. I’m not saying that’s not enough—if Woke Up Lonely‘s sole accomplishment was some measure of fun, that’d be great [lord knows how many novels don't even offer that]. But the book’s just…huge. Here’s what I mean: Woke Up Lonely is about a cult leader who wants to help people fight or overcome loneliness—Thurlow Dan’s his name, and his cult’s name is the Helix—and he’s hapless and funny and sad and riveting from the first page. Why’s he all those things? Because he spots his wife on the first page, his estranged wife and his daughter, the two of whom he hasn’t seen in years and years…which is true enough, except his wife has been spying on him (she works for a spy agency, she’s not just creepy or something) for those same years and years and, in fact, she’s spying in such a way to protect him…it all gets involved. Maybe this: you know sometimes those books you read where some question isn’t, you feel, being addressed or answered, and the fact that it’s not being addressed occurs to you and sort of fattens, parasitic, on your mind as you go a few pages, and then suddenly you’re like ARE YOU GONNA ADDRESS THIS OR NOT, and then, right after you admit your own frustration, the author actually addresses exactly the point you wanted addressed? Have you felt that? That perfect moment of desire and fulfillment getting balanced, literarily?

Woke Up Lonely is like that all the way through—the story’s as compelling and glorious as any you’ll read (along with Thurlow Dan and Esme [his wife], there are the spies Esme picks to help her run a mission on Thurlow, and the result is delicious and hilarious and amazing), and the writing: good lord. A friend and I were fixing on DeLillo last summer, reading the ones we’d missed along the way (Libra, The Names), and of course, yes, perfect icy marble prose, yes, of course, glorious, masterful, etc. But the thing with DeLillo, at least to me, is there’s so little blood in it. His stuff’s dessicated gorgeousity, but after awhile the reader (this reader anyway) is almost tempted to soak it down with some water or something, stir up the riveting, precise ground stone of the perfectness of it all. All of which is to say: Maazel’s DeLillo with blood and goofy wigs and a tendency to dance and crack weird jokes that you laugh at without even being sure you should be. Her writing’s as alive as anything I’ve come across. I dog-ear, but I’m a fucking stickler about that shit: it’s gotta be great. A usual book for me gets maybe 6 pages eared. Woke Up Lonely? 13 by the first 200 pages. Don’t take my yappering get-on-it huzzahing for this book if you don’t want—do what you like. But eventually you’re going to have to contend with Maazel. She’s the best there is. And, bonus: this is only her second book (here’s her first, and yes I’ve already ordered it, as I’m guessing should you). Meaning: get in on this now, so, in the next decade, as she keeps writing such phenomenal badassery, you can say Oh, yeah: I remember when I read her for the first time, too.

July 25, 2013

Four Things in Other Places

If you’re curious:

Here’s a poem of mine in Guernica, a magazine I’ve had the hots for for at least four years now and am tickled to be in;

Here’s a review at the Brooklyn Rail of Jean Thompson’s The Humanity Project (here’s the interview I did with her Ms Thompson in may about the same book);

Here’s a story of mine in the Doctor T. J. Eckleburg Review (with apologies for the picture at the end of the thing: it was late and I was tired);

And finally/updatedly, here’s a thing Green Mountains Review does, which they asked me to do, which was (as is damn near all they do) awesome (awesome that they do it, not awesome what I did).

July 22, 2013

The Mysterious and the Not-So-Mysterious

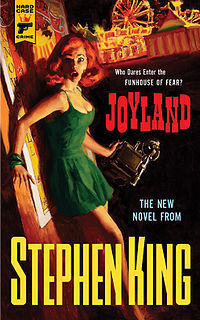

Joyland by Stephen King

I read my first Stephen King novel when I was in the seventh grade: The Wastelands, one of the installments in his Dark Tower series. It was the first book I’d ever read that wasn’t assigned by a teacher, and I tore through it in a matter of days. Sure, the writing was so-so–even as an adolescent I could tell this about King–but there were monsters and death and time warps and guns and explosions and demons, everything a discontented 13-year-old could hope for. To put it simply: it was fucking fun.

I read my first Stephen King novel when I was in the seventh grade: The Wastelands, one of the installments in his Dark Tower series. It was the first book I’d ever read that wasn’t assigned by a teacher, and I tore through it in a matter of days. Sure, the writing was so-so–even as an adolescent I could tell this about King–but there were monsters and death and time warps and guns and explosions and demons, everything a discontented 13-year-old could hope for. To put it simply: it was fucking fun.

Since then, I’ve read maybe two-thirds of King’s catalogue, and while his books and novellas tend to be either amazing (The Green Mile, Rita Hayworth and the Shawshank Redemption) or stomach-wrenchingly terrible (Duma Key, The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon) with very little grey area, that sense of fun, that at the very least the author is enjoying himself and his craft, is prevalent in all his work.

King continues this playfulness in Joyland, published by Hard Case Crime, a pulp crime throwback outfit created by Charles Ardai and Max Phillips. The company’s roster includes some three dozen or so seasoned writers, most of them with some experience in the crime and thriller genres, and each book cover is illustrated in the pulp tradition, usually featuring some busty femme fatale peering furtively at the viewer. It’s kind of brilliant really, resuscitating such a literary tradition, especially considering how increasingly fractured our attention spans are becoming, as well as the corresponding attention given to on-the-go digital literacies. In this sense, King is a perfect fit for HCC. His contribution here is a jaunty supernatural mystery whose appeal is in its insistence that the reader simply enjoy the ride without taking it too seriously.

The story is told to us by Devin Jones, a college student who, after being shunned by his sorta-girlfriend, takes a job at a shabby North Carolina amusement park called, yes, Joyland. As Devin acclimates to his quirky new environment, all the while pining for the girl (and, consequently, a chance to lose his virginity), King introduces us to the carny world with encyclopedic bravado; it’s easy at times to get distracted by all the terminology he so eagerly throws at us–park-goers are called “rubes,” the Ferris wheel is a “chump-hoister,” etc.–but perhaps this is to be expected from the man Harold Bloom once derided as “an immensely inadequate writer on a sentence-by-sentence, paragraph-by-paragraph, book-by-book basis.” The characters are predictably stock, like Ms. Shoplaw, owner of the boarding house where Devin rents a room, who is conveniently well-versed in the park’s history; or like Lane Hardy, a derby-hatted carny prone to antiquated jive talk reminiscent of Cagney, but nowhere near as cool.

But of course, it all works, albeit in that backwards pulp kind of way. Devin is a likable narrator, and most of the other characters too, partially because our dealings with them are so brief; at 283 pages, Joyland is roughly a quarter the average length of King’s books, meaning that there is much less time for the story’s weaknesses to wear on us. But mostly it’s because they do only what is necessary to move the plot along at a reasonable pace, asking very little of the reader in return. There’s a very practical reassurance here; they aren’t interested in whether or not we like them, only that we keep turning the pages.

As the story continues, we find that there is more to the park than we first expected. Or perhaps we did expect it. Isn’t that the basis for a such a story? Are we surprised to know that a young woman was once murdered by her boyfriend in the Horror House? Does it shock us to know that Fortuna, the Joyland fortune teller, might actually have psychic abilities? And are we at all jolted by the notion that Devin’s friendship with a terminally ill boy and his “foxy” mother could be the key to solving the mystery of the ghost that has allegedly been haunting Joyland?

As the story continues, we find that there is more to the park than we first expected. Or perhaps we did expect it. Isn’t that the basis for a such a story? Are we surprised to know that a young woman was once murdered by her boyfriend in the Horror House? Does it shock us to know that Fortuna, the Joyland fortune teller, might actually have psychic abilities? And are we at all jolted by the notion that Devin’s friendship with a terminally ill boy and his “foxy” mother could be the key to solving the mystery of the ghost that has allegedly been haunting Joyland?

Hardly. That’s what King’s books are all about. And really, that’s sort of what the pulp genre is all about: it’s a chump-hoister in itself, a ride that promises only the fleeting thrill of putting some distance between you and the world for a short period of time. I don’t disagree with Bloom’s contention that Western literature has been increasingly debased, but I find it problematic to assume that “popular” fiction, written for sheer enjoyment, is inherently bad (my guess is that Bloom would cringe should names like Delillo and Roth and Pynchon suddenly start selling by the cartful at Wal-Mart). Fun is a good thing, and reading, I think, at the end of the day should be fun. Joyland is no work of art, but it actively aspires not to be, at least not in the way that folks like Bloom might define it, and by that measure it is immensely successful. Just sit back and enjoy the ride.

July 16, 2013

Three New

(elsewhere, there’s this. A grasping review of a weird book)

This is a strange, compelling debut book. I’d be a sucker for it no matter what, given that it’s about baseball and the midwest—and now that I live in a town with a single A team, I’m especially susceptible to this, a chronicle of the 2010 season of the Clinton Lumber Jacks. Single-A baseball is a strange territory: its players are, of course, on the team they’re on, but their goal is to get the hell out of there and get to the bigs. So there’s tension, obviously: every player’s got at least one eye down the road, hoping. And then, in this book’s case, there’s Clinton, Iowa, a town which once had the most millionaires per capita, an old mill town on the Mississippi which has now been taken over by Archer Daniels Midland, a town which once provided the raw material with which the country would be built and now provides the raw material with which the country makes itself fat and diabetic.

And so Class A features these two odd tensions, one regarding nostalgia and what Clinton (and, by extension, the US) once was, and one regarding what these players (and, by extension, us) hope to become. It’s a strange book in this way: Mann’s an engaging guide (if his reach does at times exceed his grasp: there are scenes in which he’ll discuss playing baseball in his youth in the middle of some present tense consideration, and time gets all wobbly and the reader [at least this reader] may suddenly find himself scanning paragraphs, searching for a transition that isn’t there), but he’s ultimately writing about failure, about a town that knows precisely how far from its former glory it’s fallen and the impossibility of ever ascending to such heights again, and about baseball players, the bulk of whom will end up nada, washed away, flushed from the machinery of professional baseball for one of a thousand reasons as insignificant as injury or significant as kismet. It’s a book full of unquenched longing; it’s hard to read, hard to contend, page after page, with so much almost-but-not-quite, and yet you’ll be unable to stop. It’s a beautifully sad thing very well done.

The Book of Barely Imagined Beings: a 21st Century Bestiary

by Caspar Henderson

The Book of Barely Imagined Beings: a 21st Century Bestiary

by Caspar Henderson

I don’t even know what to say about this book. Maybe the clearer and simpler the better: the book features twenty-seven animals (one for each letter but x, which gets two) that actually do exist and includes discursive, insanely smart and wide-ranging essays which (to this reader anyway) call to mind the best of Eliot Weinberger: you feel, on finishing one of these essays (for instance, the ‘H’ one, on humans), like there are windows in your mind that’ve been suddenly yanked open which you didn’t even realize had been closed. There are certainly plenty of reasons to read this book—it’s unbelievably gorgeous, for instance (it’s from U Chicago, which should tell you plenty), and the little moralistic aspects that end each essay are grounding and wise—but the primary reason is simply wonder: you will see the world differently on closing this book. You will be more amazed. I don’t know what else one should even think of asking for from a book.

The Annals of Unsolved Crime by Edward Jay Epstein

The Annals of Unsolved Crime by Edward Jay Epstein

This is exactly what it says it is: a great book from Melville House by Epstein (who, for the record, is maybe the most fascinating writer I’d till now not heard of, a journalist whose first book—about the JFK assassination and the Warren Commission—was published when he was a graduate student at Cornell [he's The Man re: the JFK assassination, having written three books on it]) about unsolved crimes. The book’s split into five sections, each of which features chapters on unsolved crimes based on a sort of filing system, from the first section’s “Loners”: But Were They Alone?” which examines (among other things) Lincoln’s assassination and the Anthrax Attack to Part Five’s “Solved or Unsolved?” which considers the Oklahoma City bombing and “The Knox Ordeal,” (regarding Amanda Knox). There is also, not that surprisingly, an Epilogue on the JFK assassination and which is so assured and precise it’s breathtaking (and that he includes it, almost casually, as this epilogue…it’s the equivalent of name-your-favorite athlete pulling off some physically miraculous move with the ease with which mere mortals yawn or mow the lawn). In fact, Epstein is, every page, monumentally assured and precise: he pokes believable holes in all sorts of things (regarding the Zodiac killer, for instance, he claims—with a calm reasoning I find hard not to be seduced by, “Based on the lack of any matching evidence at the different crime scenes or in the letters, I assess that a single person could not have both attacked all the victims and written all the letters deemed authentic by the police.”). One’s confronted in The Annals of Unsolved Crimes with the shocking complexity involved in both the way crimes happen and the way they’re attempted to be solved (Epstein believes McVeigh and Nichols had help for the Oklahoma City bombing, but points out that the FBI wanted open-and-shut trials for the suspects they already had in custody—political expedience trumps the full extent of justice [which could be a chorus to lots of what Epstein examines]). It’s a fast and tremendously satisfying book, though one which makes questionless comfort with the larger governing structures we live with impossible.

July 12, 2013

This Close

This Close by Jessica Francis Kane

This Close by Jessica Francis Kane

The quick and dirty way of figuring whether or not this book is for you is simple: Are you the kind of person that can live with being a bit of an asshole? Are you the kind of person that can stay with a conversation in which someone gently points out the little motions you go through each day that might make you one, even if she does so gently, in a way that almost forgives at the same time it condemns? If not (and that’s totally cool – I spent years hating those people that politely pulled me aside to tell me I had some broccoli in my teeth, so I know where you’re coming from), please don’t read this book. On the other hand, if you’re just someone who’s trying their best, fucking up every now and then or daily and still getting up the next morning, trying it all again, or hell, if you’re a vision of perfection who’s sure there’s nothing a piece of fiction could say that would make you feel a centimeter smaller: Read this book. Soon.

Jessica Francis Kane has an amazing detector for societies little conundrums. Circumstances other authors might skim over, or fail to notice, Kane turns into entire stories. Example: the first piece in the collection, “Lucky Boy.” It’s 15 pages about this guy that uses a dry cleaner feeling like an asshole for using a dry cleaner. Not in a mopey way, and he doesn’t even stop going to the same place after getting to know the girls working there, yet in a way that points out how crazy it is that some people have so much cash they can get others to wash their clothes while other people are so working-class they only have money they’ve earned by washing other people’s clothes. Confusing? That’s the world as Kane sees it.

That story goes on, getting more complex and even harder to judge. Instead of simply using the cleaners, picking up fresh clothes and leaving til his suits are dirty again, main man Henry starts taking the cleaners son to the park. He starts teaching the basics of how to throw and catch a ball to this apparently father-less boy. Yet, part of him still wants to just go to the cleaners and not feel guilty if the kid never learns to play ball. The other part thinks he’s an asshole for thinking those things.

Her forgiveness is amazing, though. She’s not pointing fingers, telling us how to live or ating like she know the recipe for perfection; she’s simply saying there’s no way you’ll get there. You only get this close.

It’s not just a 1%, wealth and working class issue, either. Her stories cover a world of topics: Is it better to keep your firstborn little girl in a bubble, shield her from the world, or take the risk of letting her touch the CVS floor? Better to tell the mother of a lost friend just how much he meant, or grieve on your own, not go to her for some comfort/closure? Better to stay home and take care of your aging father and resent it the whole time, or live your own life and visit at Christmas? The sucky part is, there’s not often a third option you can go with that lets everyone win and you be the hero.

On the whole, I loved the collection, even if one or two of the stories didn’t strike me to the point of sympathy. Like “The Stand-In,” in which character Hannah (Kane often builds on the same characters, story by story, in different years of their lives, which totally works and I absolutely love in this case) and her father are on a trip to Jerusalem sans Hannah’s mother/his wife. Seeing how happy her father is with a lady named Rosa, Hannah gives her father the permission basically to go for it. To be fair, I just summed up the plot of the 20-page story in that last sentence (and her father does not go for it), but even in those pages, Kane didn’t quite get me to the point where I agreed with a girl rooting for her dad to cheat on her mom.

That’s probably the worst example in the book of where Kane lost me. A couple stories felt filler, like she stuck another in there to make the page count bigger, or at least, they didn’t hit me like they should have. But when they did, it was glorious. Word-wise: this is a book that’s more interested in sinking you into the story than getting you lost in beautiful language and heart-stopping phrases. Here’s the two sentences I’m gonna leave you with, probably my favorite writing in the book, probably the ones that best summarize the entire work, said about Maryanne the copyeditor: “She liked the chance to revise and perfect. It didn’t feel like real life at all.”

July 9, 2013

DAUGHN GIBSON

One of the most recent ways I realized I was old is that I now discover new music through NPR’s First Listen page, which I don’t imagine is like a *bad* thing or anything—maybe it’s got less to do with me being old as it’s got to do with the fact that the world of music is now so intermeshed that, well, a Jay-Z-produced soundtrack streams the week before it’s release on the website of the same media company which produces All Things Considered. Maybe all of this is old news and not worth much thinking about.

One of the most recent ways I realized I was old is that I now discover new music through NPR’s First Listen page, which I don’t imagine is like a *bad* thing or anything—maybe it’s got less to do with me being old as it’s got to do with the fact that the world of music is now so intermeshed that, well, a Jay-Z-produced soundtrack streams the week before it’s release on the website of the same media company which produces All Things Considered. Maybe all of this is old news and not worth much thinking about.

I’m frustrated to say that I missed Daughn Gibson when his debut All Hell dropped in April of 2012, but I’m glad to say that I’ve corrected for that mistake, and between trying to crack into more than just a few of the tracks on Yeezus and turning back again and again to the new Vampire Wknd and now easing into Hova’s MCHG, Gibson’s Me Moan is the thing I’ve been listening most to for a good while now, and it’s the best album on American Dark since last year’s Believers by A A Bondy.

Before anything else, below’s the first track of Me Moan, “The Sound of Law,” and, after that, the first track of Believers, “The Heart is Willing.”

I’ve never seen anyone use the term American Dark as a description for any musical genre, but it’s become clear of late that we actually need to start trying to establish and understand genres again. Take Jay-Z’s new album, which opens with “Holy Grail,” a track featuring a former boy-band leader crooning like Adam Levine (Timberlake’s voice could be almost anyone’s voice—it’s as close to featureless, at least on “Holy Grail,” as you could imagine), plus also a song featuring bits of the chorus to “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” a 20+ year old anticorporate and unlikely hit. What fucking genre features those elements? Is that still hip-hop? Is it still a hip-hop album if, on a later track, the progeny of a one-hit mulleted wonder is featured? On the one hand, it’s great that rap and hip hop are now so big and accepted that they can contain everything (though they sort of always did, hence sampling). But what’s the point of calling it hip hop if it’s got a little bit of everything? And how is what Jay-Z’s doing all that different from what Miley Cyrus or Justin Timberlake is doing, musically?

This is already getting out of hand. The point is: American Dark. I suppose the genre could be considered something like the continuing highway of music that stretches all the way back (Marcus’s Old, Weird America) and includes folks like Dylan and Townes, but has been, in the last decade plus, populated with folks like Califone, like Damien Jurado, etc. Who knows. Maybe it doesn’t much matter.

What very much does matter, however, is Daughn Gibson, and his Me Moan is strange and glorious and more than anything else totally weird and idiosyncratic: there’s almost a southern butt-rock feel to “Kissin on the Blacktop,” with its coiling low-picked guitar lines, but listen to “The Sound of Law,” again: there’s hints that the guy who made that could make “Kissin,” but it seems just as likely he’d head to darker woods. There are samples and loops going on here, same as on All Hell (I missed it, but I almost always catch up), and Gibson’s wide low rumble of a voice plays a line that I think is hard as hell to play: he can (of course) sound dead serious (as dudes who sound like they’ve got a twenty-story elevator shaft for a vocal chamber tend to), but he can also sound playful, loose, appealing to more than just the morose journaling set.

Here’s maybe another way to think about or consider the notion of American Dark as a genre: it’s weird music because it’s the work of one person, is the vision of one person. I like Jay-Z’s new one quite a bit, but it’s impossible not to hear it as the result of a whole lot of marketing and research—it’s music made for everyone. Whatever else people like Bondy or Gibson or Dylan or Van Zandt (or whoever: Richard Buckner’s on the list as well, Westerberg to a degree, maybe Chilton) have in common, it’s impossible to listen to their stuff and hear it as in any way compromised: it is agendaless music made for the sake of the listening. Anyway, Daughn Gibson: get on it pronto. Me Moan is out today from SubPop.

June 24, 2013

Drury + Offit

I’ll gladly go blue in the face declaiming the greatness of The End of Vandalism, Tom Drury’s debut novel set in Grouse County (which, for the record, Drury’s gone to lengths to make clear is not in any specific state, but I hereby would like to make clear, to Drury or whoever: I’ve lived in small town areas in both Minnesota and Iowa, and I’ve spent a lot of time in small town areas in Indiana and Illinois, and Grouse County is most assuredly Iowan, and to pretend anything otherwise is disrespectful to a) the accomplishment of what Drury’s created in his fictional county and b) the actual real-world specifics and state-to-state differences among small midwestern towns [for real: small Iowan towns—even small northern Iowan towns—are significantly different from small Minnesotan towns, even small southern MN towns]). I’ve taught Vandalism at least four times, read it half a dozen times, and feel the pull of the logic that orders the sentences and scenes so powerfully that I can’t read much else when I read it, as everything else comes off frustratingly flat at very best. I’ve read other Drury as well—I skipped his second and third novels, but then was thrilled to tackle The Driftless Area (which was direly underwhelming), and, now, Pacific, his fifth novel (and, worth noting, his third to feature some of the characters he introduced in his first novel; the books have been described as forming a trilogy, though that seems a stretch).

I’m not sure quite what to say about Pacific. It’s not as good as Vandalism, or wasn’t, anyway, as fun, and didn’t offer as many readerly goodies, at least to this reader (though it’s worlds better than The Driftless Area, which is in my all-time top-5 of Books I Wanted to Love). If you’re gonna read Drury, you’re gonna read him for the flat sentences and the weird way those sentences often snap together to provoke an exformative jolt of either humor or, if you’ve got midwestern experience, recognition. You read for sentences that are knowing and slightly aching and sweet all at once: “A reporter must question people bad things have happened to, but Albert was happier when they hung up the phone or closed the door, keeping their sadness private.” Like John Irving, with his wrestling and sexuality, Drury’s seemingly got a thing for hauntings and ghosts, spirit-working stuff. Plot doesn’t much enter here: Tiny and Joan’s son Micah goes to California, and, eventually, Lyris goes there to see him. Tiny steals stuff. Louise and Dan are still together, and the photo studio Louise worked at is now a thrift store. Dan’s investigates a thief, and Albert Robeshaw (the reporter from the sentence above) digs more into a childhood friend of that thief’s. Again: I’m not sure what to say. I read Pacific with speed and gladness, and there’s no arguing with the sentences. Not much happens, though that’s clearly not the agenda, either, so who cares. You’re reading Pacific to be among a set of very specific folks in Grouse County; for some of us, such company is worth it, regardless of what happens.

Do You Believe in Magic by Paul A Offit

The quicker the better on this: it’s a fine book, and it’s heartening and sad in lots of ways to read about folks who’ve been duped by fake medicine. That said, Dr Offic’s belittling as hell regarding medicine, and he cleaves to a premodern notion that refuses to acknowledge some of the weirder observed aspects of health (for instance, studies done regarding intercessory prayer haven’t gone both ways). Dr Offic believes in Objectivity, and that’s fine, and in lots of cases, that’s excellent: lots of health-related stuff is fairly binary, and is about diagnosing something correctly and treating it.

What Offit, in his frustration with the quakery of alternative medicine, seems disinclined to even consider, is that the binary of certain health situations (an ear infection is a specific, treatable thing) gets fuzzy when health is considered as a spectrum, or as something that’s not a diagnosable binary. To whit: if you’ve got a tumor, okay: it should be ID’d and treated. But what if you’ve got chronic pain? What if something feels weird and there’s no test on which that weirdness is registering? What then?

This is not a bad book by any stretch: it’s fascinatingly sad to read about all the ways people have tried to find healing for their maladies, but it’s also slightly sad that at no point does Offit take a moment to address the fact that medicine does not have *every* answer, and that some aspects of health lie beyond the convenient two-step of diagnose–>treat. Not a bad book at all, just one that could be better.

June 21, 2013

Shriver’s BIG BROTHER

Lionel Shriver’s Big Brother felt like something of a throwback, at least for me: it’s sort of old-school lit in the sense that it’s narrated by a very smart, articulate woman telling what seems to be a very straight-forward story. Maybe it sounds silly to posit it like that, or maybe it’s just my reading, but that at least seems worth noting. I think Richard Powers is the last writer whose work has a similar narrator—erudite, intellectually and emotionally and linguistically complex on the page. Please let me be clear, too: it’s not that other writers don’t feature such characters, but the writing style here is different, heightened [to whit (opening at random): "People hear that all the time from family, but the impact of this simple, standard avowal on my brother at that moment was both deeply moving and alarming. Releasing Cody's hand so she could shiver into her coat, he embraced me in a grateful cacoon of flesh and feathers that made me feel warm and safe, my brtother briefly restored as my protector, but also a little smothered." That's from p.128 of the galley copy, and, again, maybe all writers do this and I'm just missing it, but Shriver's sentences have this sort of high diction you'd almost expect in a novel from a century ago].

Lionel Shriver’s Big Brother felt like something of a throwback, at least for me: it’s sort of old-school lit in the sense that it’s narrated by a very smart, articulate woman telling what seems to be a very straight-forward story. Maybe it sounds silly to posit it like that, or maybe it’s just my reading, but that at least seems worth noting. I think Richard Powers is the last writer whose work has a similar narrator—erudite, intellectually and emotionally and linguistically complex on the page. Please let me be clear, too: it’s not that other writers don’t feature such characters, but the writing style here is different, heightened [to whit (opening at random): "People hear that all the time from family, but the impact of this simple, standard avowal on my brother at that moment was both deeply moving and alarming. Releasing Cody's hand so she could shiver into her coat, he embraced me in a grateful cacoon of flesh and feathers that made me feel warm and safe, my brtother briefly restored as my protector, but also a little smothered." That's from p.128 of the galley copy, and, again, maybe all writers do this and I'm just missing it, but Shriver's sentences have this sort of high diction you'd almost expect in a novel from a century ago].

Before we get too much further into this, too, I’d like to note two things. First: I’ve never read Shriver before, and wish I had, and now plan gladly to track back and pick through the older stuff. Second: I know nothing about Shriver, but I now know that she apparently eats one meal a day, and then there’s also this, which article is essential in regarding Big Brother. Why? Because the novel features Pandora, a married woman in Iowa whose older brother, Edison, is morbidly obese. The novel also features the woman’s spouse, an unhappy ascetic named Fletcher, and his two kids from another marraige.

What the novel’s ultimately about is something else entirely, and before continuing you should know that there’s a twist to the novel that is I think largely good and satisfying, but which twist complicates reviewing the thing. Regardless: what’s the novel about. Ultimately, sure, the novel concerns family and loyalties: Edison—a jazz musician in New York who has recently become homeless (having, we’ll find later, eaten himself into debt)—arranges a visit with Pandora and her step-family in Iowa for two months, and one of the easy ways to read the whole thing is as a complicated teeter-totter balancing-act Pandora’s got to pull off, tugged by her brother on one side, her family on the other.

Helpfully (and awesomely realistically: I know everyone likes to talk about how real the best fiction feels, and how the characters bleed and etc., but I’ve read no one better than Shriver at this, nobody: this book offers the most squirms and/or laughs-of-recognition per page of anything I’ve ever read), neither Edison on the one hand, nor Fletcher (and his two kids, Tanner and Cody, late and early teens, boy and girl, respectively) on the other, is easy to love: both men are troubling and demanding in all the ways folks in those roles in any life are or can be demanding/troubling. If Pandora were married to a perfectly supportive and devoted man, that’d be one thing, but she’s not: she and Fletcher appreciated each other at their relationship’s start for their ability to be silently comfortable together, and, since they’ve been married, she’s started a company that’s made her a millionaire (after running a catering company) while he’s become a) a food nazi, b) a maker of artisinal high-end furniture, and c) one of those obsessive cyclist dudes (no disrespect for them, but still).

But the novel’s actually bigger than merely being ‘about’ balancing the pulls of multivalent family. Big Brother hits so hard—and, to be clear, it hits incredibly hard—because it centers on a harder, weirder gray area: how we decide to be and become who we are, and how we choose to identify ourselves and then set out satisfying that self. In Big Brother, Fletcher’s got his whole-grain, gluten-free purity, and Edison’s got his endless appetite (for everything: cigarettes, drinks, endless foodstuffs [there's a scene in which Edison's not even eating food but ingredients, which moment nearly snapped my brain]), and Pandora’s got her trying-to-appease-everyone, go-along-to-get-along needs, and Tanner, her teenage stepson, wants something like fame for something he presumes is intrinsically just in him, naturally (the compulsion for fame has him, mid-book, run away to his step-grandfather, Pandora and Edison’s father, who played the divorced father of a trio of kids in an old sitcom, an accomplishment the man still lives within the shadows and pull of). What Big Brother addresses is: what do you value, and how do you try to satisfy and/or fulfill those values.

And here’s where I wish you’d already read the book, so we could, together, wrestle with the book’s twist, which twist casts in a pretty dramatic light exactly the results of such choices, of what we choose to value, and how. Most wonderfully, the book—which could’ve devolved at the end into a fairly maudlin, let’s-get-more-empathetic whimpering thing—ends with a hard-eyed accounting (the novel ends with the line “I pay every day.”). It’s a merciless book and one which, if you’re lucky or un- enough to have family, will likelihood force at least a few chin-clutching moments of consideration about how you value them, and how you allow yourself to be valued, and how you might work a bit harder or better at the whole messy, difficult enterprise. The thing’s a marvel.

June 6, 2013

Lanier+Brown

Who Owns the Future

by Jaron Lanier

Who Owns the Future

by Jaron Lanier

Lanier’s You Are Not a Gadget was one of 2010′s great reads, but what was weird was that it was a great read in a (to me) surprising way. The book actually was wrestling with structural questions of the internet and how it is used; I’d begun the thing thinking (as lots of the promo material’d have us believe) that Lanier, father of virtual reality (dude coined the term, a fact you’ve seen like 17% of the time you’ve seen his name, probably) was going to just talk about the ‘net, and to a degree he did, but what’s wild about Gadget is that it’s one of the smartest policy books in recent memory, even if the policy in question has to do with hugely amorphous questions of the internet and how we use it vs how we should.

So now there’s Who Owns the Future, which is an even better policy book than Gadget. I feel like I should keep backpedaling and defend the position that Lanier’s ultimately putting forward policy arguments, but the evidence is right there early on as Janier begins his book wondering about the $1B value of Instagram with its in-the-teens number of employees vs. Kodak when it had 100k+ employees and a similar valuation. Janier’s asking the great, seemindly obvious question: how does that square? If Instagram can be said to be worth $1B, what’s the value? Lanier’s the sort who writes (seemingly offhandedly) sentences like “Information always underrepresents reality,” a fact I bring up only to say that what he’s doing is emphatically not an isn’t-the-net-cool-let’s-aim-for-utopia sort of cash-out book. Dude’s got serious ideas and serious values and is rigorous about articulating them in ways lots of wonky folks would be wise to learn from.

Lanier ultimately is proposing a new way to look at the quantitative value that’s being created online by its users—those of us whose searches and likes and similar purchases are helping companies mine more and more speific and precise demographic info from which they can make money from advertisers. To go much more into it here would be to ruin the book, and the book’s too good to rob its oomph from readers in this way. Also, finally (and it may be small potatoes, but it’s cool): Lanier’s writing style is wonderfully loose; there are chapters, and then each chapter’s got like page-long considerations or sections, and the smallness of the bites that Lanier offers—this breaking of things down and down—ends up making the reading feel wonderfully intimate, like you’re actually sitting there, shoulder to shoulder with this incredibly insightful and smart man as he works his thorough way through some very heavy issues with great grace. It’s a hell of a book. I’m already excited for whatever he’ll write next.

The Boys in the Boat by Daniel James Brown

The Boys in the Boat by Daniel James Brown

The entirety of my relationship to rowing or crew or any of that is that I with some regularity use the rowing machine at the downtown Y—meaning I know next to nothing of the actual exprience of rowing aside from having some familiarity with a few of the specific motions of the ordeal.

The entirety of my relationship to significant world affairs is that I’m alive, and a voting citizen. Much past that, I’m moot: I pay taxes, I’ve protested certain things, I’ve written letters to elected officials, but that’s really it.

The entirety of my relationship with group activities—team sports, for instance—is that I played in a band in high school (one could argue an MFA program has a group activity aspect, and in its way it does, but the sublimation of individual goals for larger accomplishment is, obviously, not paramount in that setting).

And the entirety of my relationship to any pursuit of something like pure excellence is rooted mostly in writing, I suppose. Writing of course offers those of us fool enough to chase it the opportunity to carefully bring the blade of our souls or self or whatever to bear against rawer material in an attempt to capture or create some sensation.

All of this may seem sort of silly, sure, but here’s the thing: Daniel James Brown‘s The Boys in the Boat—the story of the nine rowing boys who won gold in the 2000 yard rowing event at the 1936 Olympics in Berlin (yes: Hitler)—is a staggering story made (largely) of the four strands listed above, and the book’s just remarkable, gorgeous, incredible (not least for how it starts: Joe Rantz, one of the ’36 boys, was Brown’s neighbor, and the book starts with Rantz, in hospice care, telling Brown this story).

Most significantly (I think), The Boys in the Boat is 100% immedest in its aims and goals—Brown’s swinging for distant fences, and I think he hits it. I don’t know about you, but lots of the nonfiction I receive and read is microhistory-type stuff: a history of the hand, or a consideration of holistic medicine, whatever. Brown’s Boys is big-aimed and trying to be both macro and micro: it’s a story of these nine young men and their unbelievable efforts and dedication and will and strength, but it’s also the story of why these young men, in this pursuit of theirs, has significance and relevance, both regarding the world in which they accomplished it and the world today.

It’s a stellar, stellar read, and you’re wise to get on this. Fingers crossed the book continues to pick up the attention it richly deserves.

Class A by Lucas Mann

Class A by Lucas Mann