Weston Cutter's Blog, page 33

January 21, 2011

Preempting the Backlash: Kiss Each Other Clean

The new Iron and Wine album is streaming, and it's fantastic, and before you continue reading you should click the above link and start streaming the record. And with the album's impending release, it's only a matter of days before the reviews come cresting in. Stereogum's Premature Evaluation this week set the tone for what I expect many of the reviews to ultimately insist:

"[Kiss Each Other Clean] sounds more constructed and (over, over) produced than his past records. It's a bit like Sufjan's recent folksy electronics, only less arresting."

and

"At their core, many of the 10 songs on Kiss Each Other Clean are good ones, but the more-is-more production tends to mar and bury that fact."

Now, before I continue, it's helpful to point toward two specific tracks on Kiss Each Other Clean, two that I'm singling out because I think they're the album's strongest offerings. The first track, "Walking Far From Home," offers—in terms of core songwriting—a familiar Iron and Wine structure: A verse-driven song that hinges on a central phrase or refrain, image-heavy lyrics, and a slow/looping melody. What's compelling within this track, however, is the way in which the additional vocals and instruments seem to punctuate the song. After a handful of listens, I can't find a melody stronger than those of the central main and circular background vocals. This feels much different (and more interesting than) much of Beam's other work, which—though textured—frequently feels built on central guitar melodies.

Kiss Each Other Clean's third track, "Tree By The River," is a much more conventional (and instantly likeable) pop-song, and it's exactly the kind of thing that I suspect will drive the backlash. This is unfortunate. "Tree By The River," like much of this record, feels like it's channeling Van Morrison, like it's a forgotten product of 70s radio. I love it. And I especially love how far it stands from early (and just as good) Iron and Wine tracks like "Lion's Mane" or the more recent "Boy with a Coin." This is an artist pushing at his boundaries, feeling his way through new influences and new configurations. And—beyond just the strength of the record—there's something to applaud there.

I know that not everyone will feel the same, and that's fine as well. What bothers me about reviews like Stereogum's, however, is the reliance on terms like "over, over produced" and "more-is-more production." What does that even mean? Sure, stack "Walking Far From Home" against "The Sea and the Rhythm" and you'll hear a significant increase in production values and sonic spectrum. This is a rather obvious assertion: One was recorded in Beam's house about a decade ago, while the other was recorded in a proper studio this year. That'll net some difference in production. Beyond that, however, "over-production" strikes me as one of those nebulous critical terms without weight, a vague way of saying, "This album sounds too pretty." I think there are instances where too much studio gloss can ruin a record (I'm looking at you, Jimmy Eat World), where post-production numbs a song, removing some of the rawness that (rock especially) music might demand. But there are just as many instances where a band manages something amazing in the studio, using a large recording budget to realize a specific sound. (Superdrag's Head Trip in Every Key, a largely forgotten late-90s records, is one of my favorite examples of this. It's a beautiful album.) And it's also entirely possible to produce a sort of faux lo-fi sound; the right budget and pro tools rig can make many sounds possible.

My point in this is to say that critiques of Kiss Each Other Clean as overproduced or manufactured are mostly rubbish. Stereogum notes a difference between this record and Sufjan's newest, the latter of which is more arresting. I'd agree. But the comparison isn't fair: Sufjan is making a different kind of album, one with a different motivation (a meditation on the body, as I see it) while Beam is forging a contemporary homage to 70s radio pop—that still, at its core, maintains many of the Iron and Wine conventions that drove his early albums. Sure, any number of Iron and Wine fans are going to hold out hope for another acoustic album, one that's just a guy in his bedroom recoding on a four track. Fair enough. But artistic trajectories exist on a continuum: There's an arc between, say, Roth's Goodbye, Columbus and American Pastoral, and—to me—the development that occurred between those books is just as compelling as either of the novels themselves.

And after my first few spins of Kiss Each Other Clean, I'm fairly sure that it won't be my favorite Iron and Wine album. What I can also see, however, is a strong and fascinating record, one that marks an artist moving far beyond his first bedroom tapes and the experiments that followed. And we still have those tapes and all the great records that followed them, so: When you see the somewhat expected round of critiques that hail this album as "over-produced" and the product of major label money, just nod your head and press repeat on "Walking Far From Home." Beam's mix of vocals and instruments are far more compelling than the arguments made thus far about them.

January 18, 2011

Games + Ha Ha

Reality is Broken

by Jane McGonigal

Reality is Broken

by Jane McGonigal

I feel like this book's as hyped a book as I've seen in awhile, and for good reason: McGonigal's been a TED conference speaker, and she's got some of the most interesting ideas about video gaming that I've heard, ever. Rest assured: if you're a video game lover, you'll enjoy this book, but, awesomely, if you believe video games are a total waste of time, you'll enjoy this book as well. In fact, I'd argue the book might be best for folks who pooh pooh video games as gigantic time sucks.

Because why? Because McGonigal's got strange historical facts to present, the easiest one to PR-ify and pass around being the one about a King Atys in Asia Minor, 3,000 year before Herodotus, and how there was a famine for eighteen years, and the solve for the food lack was for everyone in the culture to play games one day and eat the next—the idea being that games would keep minds off food for 24 hours, and then, the next day, vice versa. It worked, by the way: that system and plan worked.

Actually, it's unfair to talk about the historical aspects McGonical presents as being most critical: the staggering statistics of contemporary gaming are just mind-melting—for instance, that all the gaming hours added up among the millions of players around the world tip the scales at way more than several billion hours. Wrap (or try to, anyway) your head around that.

Here's what McGonigal's setting out to prove and establish: that the seduction of games (of which I'd imagine every single person reading this has been touched by, from a multi-hour jag of World of Warcraft to simpler, diversionary 10-minute breaks to Minesweeper or Tetris or Scrabble or whatever) can be harnessed to better use than simply offering the player quick solipsistic synaptic snaps of joy—her example being SETI@home, the computer program which allows interested users the donate computer processing power to the organization which searches for extra terrestrial life. Thing of Tom Sawyer tricking friends into painting the fence: McGonigal's got similar ideas for games, and the descriptions of the games she's designed to offer people direct access to things/events which quantifiably make life better—dancing, talking to older people—are riveting. Who'd think a game set in a cemetary'd be great? Anyone?

McGonical, of course. I'm not joking: Reality is Broken seems poised to be as critical a book of cultural study and awareness as Brooks's Bobos or Putnam's Bowling Alone. Miss the boat at your own discretion on this one.

Zombie Spaceship Wasteland

by Patton Oswalt

Zombie Spaceship Wasteland

by Patton Oswalt

No: I'm not a rabid Patton Oswalt fan. I like him a lot, sure, but I'm not so massive a fan I'm upended by my affection and therefore unable to be objective about him. He's a funny guy. He makes me laugh sometimes. He seems to have interesting friends.

Far more critically: holy shit is this guy a good writer. Patton Oswalt is such a good writer, in fact, that you're forgiven, upon reading this book, for thinking that he should put his energy toward books intead of acting—not because he's bad at the latter, but because he's overwhelmingly good at the former. There's hilarious memoir-ish essays of teenagerhood and awkwardness (the hypnotically great "Ticket Booth,"), there's uncomfortably funny/sad (or sad/funny) pieces ("A History of America from 1988 to 1996," in which Oswalt, simply by [probably not 100% accurately] quoting the comedians for whom he opened in the time period mentioned hilariously offers a glimpse at what was happening in the US and the world at that moment), there are pictures (there's a comic). There's the hilarious world/personality-parsing of the collection's title piece.

Throughout everything, Oswalt dazzles with accessible, hell-yes sentences, and with mentions of exactly the bands and books and movies I, at least, like seeing mention of—R.E.M's in here, ditto Cormac McCarthy, Sarah Vowell, Star Wars, etc. It's a fantastic, hugely compelling read: this book is one of the most satisfying and surprising reads I can imagine.

January 15, 2011

Albums You Missed in 2010, Part One

At the end of each year, music writers give a great deal of attention to a rather small array of albums. This annual heralding is great, and it helps to focus listening patterns and fuel conversations—the sort of things that good music tends to do. And while 2010′s crop of "best of" is well worth your listening time and energy (The National, The Arcade Fire, Kanye, Best Coast, The Tallest Man on Earth, Sufjan, and so many others), I want to also make some space in January for the records you might've missed in 2010… the albums that, for whatever reason, just didn't get the love or the press or the online attention. I'm not going to say that these records have mass appeal (what ever does?) or are perfect compositions, but I think that within each of these albums there's something to appreciate and to dwell on, something worth focusing on—and returning to.

Jim Bryson & The Weakerthans: The Falcon Lake Incident

[image error]Unfamiliar with Jim Bryson's work, I picked up this record solely for the Weakerthans—and wow, what a surprise. If you're a fan of the Weakerthans, this is more of what we've come to expect and love: midtempo tracks with smart lyrics and instrumentation that ranges from the perfectly sparse to the appropriately brash. "Freeways in the Frontyard" is a standout a track, a quiet number worth a few minutes of your time:

There's something pretty incredible in those drawn out verses, and there's something immediately likeable in nostalgia-heavy lines like "let's watch the clouds collide and cover up the setting sun / just like we did when we were quite young." In many ways, this record feels like it should be a soundtrack to a film: A movie where people kick around a small town filled mostly with porches and diners and the ghost of something industrial. I think I've seen that movie—or maybe I've just listened to this record so many times that the narrative has built itself from the verses. Regardless, this is absolutely one of 2010′s hidden gems. And if you're not yet familiar with the Weakerthans, consider this an introduction to your new favorite band.

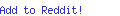

Someone Still Loves You Boris Yeltsin – Let It Sway

Let It Sway marks the next step in an impressive evolution for Someone Still Loves You Boris Yeltsin (SSLYBY), a growth from droney bedroom lo-fi (see, for example, Broom, their standout debut album) into something of a power-pop group. Then again, "power pop" has a number of connotations attached to it, and it's not entirely fair to toss SSLYBY into that mix. Consider, for example, "Back In The Saddle," Let It Sway's opener, and my hands-down favorite track of 2010. It begins with the quiet, almost muted sound of bedroom lo-fi but then kicks into something more anthem-like, a whirlwind of guitars and sing-along vocals and deceptively simple lyrics. But then, just when you think you have the pattern figured out, the song stumbles into an outro, spiraling out of hand in its closing moments. It's totally impressive and beautiful. (And I'll link here, for the time being, to an incredible mashup of "Back In The Saddle" and various Aerosmith footage, which is equal parts awesome and a reminder of how terrible Aerosmith is):

Let It Sway marks the next step in an impressive evolution for Someone Still Loves You Boris Yeltsin (SSLYBY), a growth from droney bedroom lo-fi (see, for example, Broom, their standout debut album) into something of a power-pop group. Then again, "power pop" has a number of connotations attached to it, and it's not entirely fair to toss SSLYBY into that mix. Consider, for example, "Back In The Saddle," Let It Sway's opener, and my hands-down favorite track of 2010. It begins with the quiet, almost muted sound of bedroom lo-fi but then kicks into something more anthem-like, a whirlwind of guitars and sing-along vocals and deceptively simple lyrics. But then, just when you think you have the pattern figured out, the song stumbles into an outro, spiraling out of hand in its closing moments. It's totally impressive and beautiful. (And I'll link here, for the time being, to an incredible mashup of "Back In The Saddle" and various Aerosmith footage, which is equal parts awesome and a reminder of how terrible Aerosmith is):

There are, however, poppier moments on Let It Sway, and the album's title track is a reminder that, despite all of the subgenres and splinters of contemporary rock music, there's a lot to be said for some verses and choruses and a good hook:

To be totally honest: On the first few listens, Let It Sway seems much stronger in its opening throes than it does in the second half. But this record is a grower, the kind of thing that blossoms with additional listens and attention—really, the best kind of pop record. When I look back and think about the albums that have moved me most, they're always the ones that, on first listen, seem too simple or too odd. But through the repetition of a single track, I find myself exploring the neighboring songs, and then the songs that neighbor those songs, until I've wound my way through the whole collection. And then the whole thing comes together as an obsession, an infection, a reminder of why I'm drawn to new music. Start with "Back In The Saddle" or "Everylyn" or any other hooky track on the record and then work your way through the rest. I'm pretty sure you'll find yourself in love with one of the most (tragically) underrated albums of 2010.

Against Me – White Crosses:

Unlike The Falcon Lake Incident or Let It Sway, White Crosses isn't a record for everyone, and if you're not drawn to punk or brash vocals or stacks of electric guitars, I probably wouldn't recommend this record. But for the rest of us, those who cut our teeth on punk and have since pushed into other directions, I think there's a lot of great things happening on White Crosses. I found White Crosses when, in the space of a long drive, I had the iPod set to shuffle through some new albums, and—wham—the opening chords hit hard, a sort of audio brick through the window, a reminder of the first punk records I purchased that were equal parts aggressive and electric.

Unlike The Falcon Lake Incident or Let It Sway, White Crosses isn't a record for everyone, and if you're not drawn to punk or brash vocals or stacks of electric guitars, I probably wouldn't recommend this record. But for the rest of us, those who cut our teeth on punk and have since pushed into other directions, I think there's a lot of great things happening on White Crosses. I found White Crosses when, in the space of a long drive, I had the iPod set to shuffle through some new albums, and—wham—the opening chords hit hard, a sort of audio brick through the window, a reminder of the first punk records I purchased that were equal parts aggressive and electric.

Now, a bit of necessary context: Against Me gets a lot of internet hate for "selling out," and a cursory Google search will yield any number of stories and opinions about the band's move from an independent to major label—as well as changes in lyrical content or musical stylings. And once upon a time, at age 16, in my punk rock prime, I might've been concerned with such things. Not so much now. I'm not the biggest fan of major labels, but I do understand the desire to have health insurance or to put some money in savings, and I also know that the interests and perspectives of artists shift over time. Fair enough. So, in short, I'm not entirely interested in the punk rock community's problems with Against Me.

What I am interested in, however, is the way that White Crosses paints a sort of picture of youth. It's a move you can see in so many songs (I think immediately of the differences between "Bastards of Young" and "Love Untold"), but Against Me really manage to weave the bittersweet with the angry. Look at "I Was A Teenage Anarchist":

There's the obvious-enough sing-along chorus — "Do you remember when you were young and you wanted to set the world on fire?" — but the truth, the energy, the crux of the song boils down to that last moment of the last verse, after the melody has just slightly shifted upwards and everything comes to a halt on "The revolution was a lie." There's a break there, an understanding that time morphs and attitudes shift and that what once worked or was promised won't always be that way. That what once seemed so genuine and honest was always marketed, always constructed, always impossible. And for me, mixed with the whole of a loud, uptempo, four-four record, there's something to really like in that honesty and that memory and the music that grows from it.

I do think that New Wave was a stronger record, and if you haven't heard New Wave, even if you're kinda sketchy on brash rock-n-roll, the first track (and its Replacements-homage video) is absolutely worth a spin. Still, White Crosses is a fine successor (with a opening track that's just as good as New Wave's) and a reminder that Butch Vig still has the same sort of sonic grasp that we once heard on Experimental Jet Set, Thrash and No Star and Siamese Dream. I'm not, mind you, saying that White Crosses is on that level… instead that, maybe, I have a lot of love for the music of the early/mid-90s, and that, occasionally, there's a track or an album that echoes something from that era. White Crosses is that kind of an album, and it's one that just didn't see enough love in 2010.

January 9, 2011

Picture Books + Poetry

Public Parks by Alexander Garvin and Walk This Way: Sign Graphics Now by Matteo Cossu

I'm no better than a little kid: sometimes I like big, huge books, with color and pictures, and the sniffy/highbrow way of talking about that, yes, is to discuss coffee table books, but, until real recently, I didn't have a coffee table, and I'd just open the suckers on the dusty dog-hairy ground, paging. Good books in this category aren't all that rare—art monographs and/or catalogs are almost worth any time invested, and like 90% of the U Chicago/Yale/Princeton coffee table books that come out are fantastic. Anyway.

I'm no better than a little kid: sometimes I like big, huge books, with color and pictures, and the sniffy/highbrow way of talking about that, yes, is to discuss coffee table books, but, until real recently, I didn't have a coffee table, and I'd just open the suckers on the dusty dog-hairy ground, paging. Good books in this category aren't all that rare—art monographs and/or catalogs are almost worth any time invested, and like 90% of the U Chicago/Yale/Princeton coffee table books that come out are fantastic. Anyway.

Well, so, there were two in 2010 that I thought were awesome, and yes, I'll 100% admit that because I'm in love with a city planner my tastes head that direction. Still: even without E in my life, I'd be into these books.

The first one, Public Parks, is just exceptional: gorgeous, informative as a paged through Encyclopedia, massively riveting (in both large and small ways, from finding out that there used to be horse-drawn barges up a canal in Washington DC to the history of French Gardens and their impact on other parks). Yes: tons of space given to New York and Chicago, and sure, this MN's shoulder-chip was inflamed by the impression that his own beloved city was not looked closely enough at. Still: it's a hell of a book, and that subtitle? The Key to Livable Communities? It's actually fascinating: this book is lush, easier reading for anyone who's been tracking and loving the work of Lewis Hyde. Meaning what? Meaning if you're into notions of stewardship, of hard-to-quantify generative spaces, this is for you.

The other one, Walk This Way, is fantastic. Look, everybody's gotten lost while traveling at some point, and nothing's more frustrating than signs which, for all their oh-duh-that's-obvious-ness, are maddeningly hard to decipher (and not just linguistically, now: how about streetsigns which are crooked, or which don't necessarily make clear which street they're point down [I'm looking at you, three-way intersections in Chicago!]). I'd guess most of us don't spend too much time thinking of alternatives for how signs could convey info, and that's probably fine, but I think most of us'd benefit from spending some time at least considering how things could be different. This book is your entrance to such consideration, and I can say 100% say this with certainty: I learned more and my mind was more opened by this book than most others I've read in the past 12 months.

Missing You, Metropolis by Gary Jackson and Otherwise Elsewhere by David Rivard

I recently was talking (emailing) with a friend about poetry presses–we were talking which are best, which offer prettiest books, best lists, etc. There's (of course) Pitt and Copper Canyon, and there's Wave and Sarabande, but there's also, always, of course, Graywolf. Look, I've gone on too much about this press already—if they had sales like Dalkey Archive had sales, in which one could purchase 20 titles for $100 or whatever, I'd be hopelessly hosed—but I can't help that they consistently release some of the best books in the country, specifically with regard to poetry (Nick Flynn's new one's coming from them shortly, for instance).

Anyway: same song about Graywolf, over and over, this time regarding Rivard's Otherwise Elsewhere and Jackson's debut Missing You, Metropolis. I loved both—Rivard for the just-barely-within-reach associations pagely through the thing, how the poems gave much which still pushing the reader into new spots, and I've been back and forth through the thing maybe 5 times since fall, and it deserves way more mention and hype and push than this, but here's a start.

Jackson's debut is fucking mega, epic, fantastically cool: it's comic book love in poetry, it's youth and learning/longing, and everybody's here—Lois Lane, Gotham, Iron Man, Avengers—and it's just…words fail, give way in describing this book. Here's what I can say: all poetry depends on utterance, which needs a place from where words begin, and Jackson's made this Metropolis, decked it with what's made him and got him to where he is, and I know of few (none that I can think of off the top of my head) debut collections which so artfully, awesomely cover the terrain of former self, of self-discovery. It's also worth noting that this book's funny as hell—this is poetry for everybody, those of us who love/need the stuff, those who loathe it and cross the street to avoid it.

Jackson's debut is fucking mega, epic, fantastically cool: it's comic book love in poetry, it's youth and learning/longing, and everybody's here—Lois Lane, Gotham, Iron Man, Avengers—and it's just…words fail, give way in describing this book. Here's what I can say: all poetry depends on utterance, which needs a place from where words begin, and Jackson's made this Metropolis, decked it with what's made him and got him to where he is, and I know of few (none that I can think of off the top of my head) debut collections which so artfully, awesomely cover the terrain of former self, of self-discovery. It's also worth noting that this book's funny as hell—this is poetry for everybody, those of us who love/need the stuff, those who loathe it and cross the street to avoid it.

January 5, 2011

Marcus/Dylan and Wings for Purchase

I Just Lately Started Buying Wings

by Kim Dana Kupperman

Though I certainly like my share of nonfiction work, it's rare that I read collections of essays by single authors. I'll make the obvious exception for McPhee and would when Wallace dropped his, but, honestly, single-author collection of essays just haven't seemed to hold, at least to me. (for those who read them: what've been good ones? Was Lethem's? Franzen's back years ago was eh, and Chabon's seems okay; Zadie Smith's was great–I'll take it back, that's the last one I read and loved–but even that wasn't just general, it was a series of essays on books, there was a through-thread tugging that thing).

Anyway, hi. Here's what happened: I got this book way back, set it aside, and then, a month ago, was hankering to read something and wasn't thrilled with what was in front of me, so I grabbed this and holy shit did it grab back. Here's the sort of writing one confronts:

"We both knew that nothing was really wrong, nor was anything really right, which described as well the state of our deteriorating friendship. And we understood the known-yet-unknown state of affairs as if we had a fused consciousness and it was this manner of understanding that had drawn Irina and me together in the first place. This merged thinking would also drive us apart, as if there weren't enough space in the same perception for both of us."

A note: the book's subtitle is Missives from the Other Side of Silence, and while I'd like to offer some song+dance about what the book's about or what connects it or whatever, that blipped smidgen above is actually a good guide: what the book offers is Kupperman, is a woman who has a Full Self (more on that in a second), is a woman who wants to put herself against life's side in various locales and, if not understand it, at least hear the keyest pulsing. And so Kupperman talks about her mother through a recollection of the woman cleaning house and passing on the phrase Beauty hurts, and so she talks about her grandmother who lied about the place of her birth, and she talks about going to Russia and traveling through, trying to make some sense of one tributary of her heritage, and so she talks about airports and emergency levels, about domestic shelters and desire. This may or may not sound riveting, but I promise it's all riveting because of Kupperman—not because of her voice, but because of her person.

This is that thing about the Full Self. I don't know, maybe it's just me, but one of the reason I assume I don't tend toward essay collections is because, often enough, single essays can sometimes feel coy, back-turned, withheld, ironic—there's an I'm-coming-clean sense that's so hyped (by clues great and small in the text) that I can't believe it, or, worse, I believe the impulse for coming clean's more important than the coming clean. Not so with Kupperman: she's incredibly straight on the page, and by straight I mean riveting and aware and unironic and unafraid to be sincere and serious, and holy hell is this a fine, fine book. Fine enough to convince me of the goodness of a whole type of book I've been overlooking for awhile now.

Bob Dylan by Greil Marcus

by Greil Marcus

Good god, speaking of Full Selves. What's to say about this book? That you're a fool not to read it, automatically, because it's Marcus? That this is 2010′s second amazing Dylan book (hello S. Wilenz's Dyan in America)? That that old line, about how if horses didn't exist humans would've invented them, applies to Dylan and Marcus, too? The fact that this book's content's been drawn from smidgens and bits stretched across decades is both a positive and a negative—the reading can sometimes be too quick, the discrete bits of info like the point at which a skipped pebble and lake meet, but the book's massive, and it becomes, page after page, accretive through speed. It's a both thing, the brevity and pace.

And Dylan! Good lord. A group of friends and I list our top 10 records at each year's end, and I've included Dylan when he's released he's last few albums, and holy shit, reading this book you can't help but be stunned with wonder that this man's done what he's done. If there's any sorrow available in/through/from this book, it's because of this: who knows how long it'll be till someone like Dylan bothers opening wide again, how many generations.

January 2, 2011

Patrick Somerville + HAPPY NEW YEAR

I can, fortunately or un-, remember exactly when it was I last read a book of stories as compelling and gasp-inducingly fucking gorgeous as Patrick Somerville's The Universe in Miniature in Miniature: it was four years ago, and it was Kelly Link's Magic for Beginners. There've been great collections since then, of course—Blake Butler's Scortch Atlas comes instantly to mind, plus every collection ever by Jim Shepard—but it's been a long, long time since I've been this knocked back and shocked by a book.

I can, fortunately or un-, remember exactly when it was I last read a book of stories as compelling and gasp-inducingly fucking gorgeous as Patrick Somerville's The Universe in Miniature in Miniature: it was four years ago, and it was Kelly Link's Magic for Beginners. There've been great collections since then, of course—Blake Butler's Scortch Atlas comes instantly to mind, plus every collection ever by Jim Shepard—but it's been a long, long time since I've been this knocked back and shocked by a book.

I started this book on a plane flying from Iowa to Atlanta, and Ellen was beside me, reading her own book, and I had to damn near put my hand over my mouth to keep from constantly, botheringly interrupting her, hitting her with these sentences which were, at 34,000 feet hitting me hard as hell. That, more than anything else, is the Somerville magic, or at least where it's most clearly manifest: in sentences. Here's a good sample, drawn entirely at random:

"Lucy says we aren't watching to see if he will die. 'That would miss the whole point,' she says. 'And besides,' she says, 'that would be, like, cruel.'" ("Universe/Miniature/Miniature")

"I recognized it from the one time I had done it in Grayson, when I'd first come back to the midwest. I'd met an old friend and we'd gone to the playground at the same elementary school we'd attended twenty years before. He had gotten into ATV sales or something. I'd spent a lot of time having fourth-grade memories come into my head, not really knowing whether they were real or whether I was making them up—they'd been too pleasant, in a way, and didn't fit into my haunted, dark-enchanted-forest sense of childhood. The kind where the trees eat little boys. He'd asked me why I came back, and I said "It was so lonely out there," which had felt basically true, and then we'd smoked the meth." ("No Sun")

"Phil is not much of a researcher, or a reader, or someone who thinks anything through. For him to be preparing is a meaningful development. It's like a horse reading The Celestine Prophecy." ("Hair University")

Look, I could keep going on and on like this—honestly, every page, or, at very least, every third page, featured lines like these—lines which featured a loose, chummy, playful confidence, lines which just fucking shone with good.

It's worth me at least acknowledging all the ways I'm prediscposed to liking this book. First, it's Somerville, and his the Cradle knocked me sideways two years (or whenever) back. Second, it's out from Featherproof, and if there's a more interesting press publishing more gorgeous books—I'm talking all presses now, indie or big guys—I don't know of it. Third, the book's not only midwestern, but features one of my all-time favorite trick of midwest fiction: setting it in a fictitious town. I admit this may be a moderately silly adoration on my part, but seriously: fictitious midwest towns are where it's at. Someday somebody smart'll put together an amazing atlas of fictitions towns (for the record: one of this year's upcoming devastators is Alan Heathcock's Volt, which is a powerhorse of a collection as well, and that whole thing? It's set in Krafton, another fake midwestern town). Anyway, those are three legitimate beefs you could cite regarding my overwhelming enthusiasm for Somerville and Universe/Miniature/Miniature.

But still…you should believe. You should believe how good this book is. Look again at that long passage from the story called "No Sun"—in which, by the way, the sun stops shining (not really: the world stops spinning, but the result's basically the same). The genius of Universe is in the decisions at sentence level: that whole paragraph's just about the moment a character spots some meth on a gas station's counter, yet look at what you get, look at all you're begin given by this generous, incredible author—not just the ass-kicking fireworky stuff ("didn't fit into my haunted, dark-enchanted-forest sense of childhood. The kind where the trees eat little boys."), but the quieter, plainer stuff ("He'd asked me why I came back, and I said "It was so lonely out there," which had felt basically true, and then we'd smoked the meth."). Look, here's a simple quiz: if you're the sort of reader who just fell sideways over reading Cather/Rye and Holden's description of his brother's red hair (right at the start—Holden teeing up at the golf course—go to the shelf, pull it down and read, it's before page 13), you need to read Universe/Miniature just for the sentences alone, for the associative glory of them. These are sentences propped one after another by someone with a phenomenal sense of how to make a reader comfortable, how to befriend a reader with nothing more than sentence order.

If that's not your thing, though, you're still not off the hook. Like gorgeous books? Pick this thing up–and, please, write a letter to Featherproof, letting them know how gorgeous the thing. Like pictures in your book? There's pictures in here. Like fiction which is attempting to solve or address questions of empathy, aloneness, the boundaries of self, the difficulty of truly connecting and being with and loving another?

See how that snuck up?

It's easy to flap arms and shout about Somerville's sentences—they are really, really, really that good. What Somerville's actually doing in these stories—the things he's trying to make happen among and to his characters—is orders of magnitude more difficult and gorgeous. Here's another quiz: in a non-Gardner way, are you interested in moral fiction? That is, fiction which, in some way, attempts to address how it feels to be alive and trying to connect to people and feel honest, decent love, to make do—and, actually, not just fiction with addresses it, but which honestly reckons with the difficulties, the threats, the risks, the attendant harm?

This sounds lofty. It is. Not for nothing did Wallace couch such questions in futuristic tellings of tennis academies and halfway houses, and Somerville, in his collection, couches such questions in strange quasi-science-y ways. In these stories, the earth stops spinning, there's a machine for understanding other people, an ox and man are burned on the same pyre. The word and idea of Pangea comes up more times than I kept track of. There are—maybe I've said this—some of the best sentences written in a long while.

Look, just read this book. It's the new year. You've got resolutions. I guarantee that, if you're generous with your definitions and yourself, reading Patrick Somerville's The Universe in Miniature in Miniature will fulfill at least two of them, maybe more. Read and be amazed.

December 28, 2010

MINNESOTANS: WEDNESDAY NIGHT

Mostly I like to keep this third persony and distant, but now I've actually got an event, and would love the place filled, so:

Mostly I like to keep this third persony and distant, but now I've actually got an event, and would love the place filled, so:

Wednesday, December 29th, at 7:30pm, there'll be a book launch at Common Good Books for my first book, You'd Be a Stranger, Too. I'm told there'll be stuff to eat and drink, and, for sure, there'll be me and copies of the book available, and there'll be some things read and lots of laughs laughed and the usual. Again: it'd be great to get the place filled.

And, of course, happy holidays and etc. and stay warm, whichever snowpocalypse you did or did not shovel through.

December 20, 2010

Sean Manning's The Things That Need Doing

Sean Manning's The Things That Need Doing was a hard book to read, not least because it is, start to finish, a book about a young man's mother dying. The book's difficulty, though, for me, was more than merely subject matter: stress young in the description one sentence prior. The Things That Need Doing is, certainly, a moving and tender book of a pretty overwhelming love of son for mother, and it's equally a mesmerizing glipmse of the world of late-stage life-saving hospital work, but it's also a book very very very much centered around young Sean Manning, a writer whose work (as an editor) I've been excited by often recently.

Sean Manning's The Things That Need Doing was a hard book to read, not least because it is, start to finish, a book about a young man's mother dying. The book's difficulty, though, for me, was more than merely subject matter: stress young in the description one sentence prior. The Things That Need Doing is, certainly, a moving and tender book of a pretty overwhelming love of son for mother, and it's equally a mesmerizing glipmse of the world of late-stage life-saving hospital work, but it's also a book very very very much centered around young Sean Manning, a writer whose work (as an editor) I've been excited by often recently.

Let's maybe step back and establish some things: though certainly my top 10 any art thing—albums, books, films—likely feature at least 50% of material either about or made by dudes who fit several demographic categories I do as well (dudes, white, middle-class, educated, etc.), I get tired of stuff that features, well, me. I've gone on about this stuff before, elsewhere and here at Corduroy, so I don't want to get too much into it. I'm saying this mostly because I want to signal just who's writing this review, and with what mentality and agenda (lest I sound too pompous: my first book of stories has just been released, and a majority of the work in there features narrators exactly like I am—meaning, I guess, I bemoan this stuff, but it's not like I've got some pocketful of silver bullets).

Back to Manning: the easiest rebut to the above is, well, dude, he's writing nonfiction, and he's writing about his life and his mom and his months in Cleveland hospitals and his experience watching Lebron and the Cavs, etc. Too all of which I say: yes, of course, absolutely. And it actually occurs to me that maybe I've pooched the screw on this one already: I liked lots of aspects of this book, and read it glad and fast on a Saturday afternoon.

Here's maybe an easier way to get at this: the books Manning's edited up until now are writerly books, featuring other writers talking about 1) their favorite books, 2) their favorite baseball players, and 3) their favorite concerts. Meaning what? Meaning this is someone who's editorial impulse has so far been to let artists talk about the other art they like, in categories sometimes aside from those in which they work. Why's this significant? Because Manning's story of his mother's death (months and months long, plus flashbacks) features all sorts of Klosterman/Horby-ish moments of significant emotional impact happening simultaneous with moments of sports and/or music.

There's nothing wrong with this—lots of us do this, and it's not at heart a bad venture—but it's a strange thing, how this happens. Here's the way to talk about this in exceptionally positive terms: Manning's so willing to tell his mother's story completely that he's also willing to let himself look, quite often, pretty self-involved, pretty self-centered. Which is a gutsy thing to do, as a writer—to allow oneself to look bad on the page for the sake of the story.

I don't know. I go back and forth on this stuff. For the record: I blame Klosterman for this affect/tic—he's the one who took Hornby's slight, self-depricating style and Americanized it, blocked it hard and heavy for the American stage. What it comes down to, for me, is that this book, Manning's The Things That Need Doing, is, certainly, yes, a moving and beautiful book about his mom's death, and it's about how he and his dad (his parents were divorced but, touchingly, his dad was 100% present for his ex-wife's death) made decisions and coped, and it ends just gorgeously, achingly. However, here's what you realize on the last page: Manning gets out of the way and just recalls—he doesn't try so hard to make himself appear on the page, doesn't try to make the reader see/think/feel certain things about him. It's a gorgeous last several pages, and the fact that Manning didn't offer more writing like that earlier can be frustrating, but it's also exciting to think of what he's capable of, what he'll be able to do when he's trying to stuff less self onto each page.

December 14, 2010

Miracles and Cities and Highways

Morning Miracle

by Dave Kindred

This book knocked me sideways in a fashion I didn't even realize I was desperately in need of. Here's what to first disabuse yourself regarding when you approach this book: though the book's subtitle is Inside the Washington Post: A Great Newspaper Fights for Its Life, please don't imagine this'll be a bland or airless walk-through of a death rattle of the Post. Certainly the life and vitality of the Post is one of the things that's under examination here, but far more thrilling is what the book really is: it's Dave Kindred being a thrilled, devoted, rhapsodic newspaper lover, page after page.

Admission: my favorite Smithsonian museum is the Postal museum, which is so compelling and great I'll spend whole blocks of DC time therein whenever I'm at the capital for the rest of my life. Mail is fiercely great to me, and why? Because it's the root of democracy—cheap and easy spread of info and ideas, a system which allows citizens to make stitches of contact across the national fabric. I get fully of silly gusto just thinking about it. Kindred, I'd guess, probably likes the postal museum as much as I do: his love for the Post isn't simply that it's a legendarily great paper (though it is—Bradlee, Graham, Woodward/Bernstein, etc.), but that big, powerful newspapers are totems of the best ideals of democracy. Sound dorky? Maybe it is. This book is, for this newspaper lover (and lord, if you think you don't care about newspapers, move to a part of the country where you can't have a newspaper delivered and then note whether you miss the artifiact), is a muscled, powerful valentine to one of the best inventions in history. Are times bleak for newspapering? Oh lord yes. But you'd be a fool not to read Kindred and fully understand the whole game.

Makeshift Metropolis by Witold Rybczynski

Makeshift Metropolis by Witold Rybczynski

I happen to be real interested in cities, which interest has been massively furthered by the fact that I am in love with a city planner (which I heartily recommend, if anyone's interested: falling in love with someone whose interests [professional or personal] you find enticing's a sure way to keep lotsa fires burning), all of which is simply to say that Rybczynski's Makeshift Metropolis was both a fantastic book to get in the mail and, weirdly, also sort of a let down.

Let me first clear up why it may remotely be a let-down: if you think lots about cities; if you and your beloved sit and talk at length about how a city's health has much to do with density; if you understand that transportation is the single biggest shaper of how cities have been made in the last century and also how, as fossil fuels increase in price, cheap transportation will make sprawling exurban areas untenable; if you know who Jane Jacobs is (to say nothing of Moses)—if you know all of these details, this book will likely be interesting read, but not necessarily illuminating reading. This is, in the best ways, a sort of entry into contemporary thinking regarding city planning and designing by one of the best thinkers we've got.

However, if all of the above does not apply to you, get this book. If you're lucky enough to have the spare time and mental energy to wonder why cities are as they are, this book should absolutely be something you have on your nightstand, the sooner the better. Lest, of course, this sound like as nerdy a topic as my professed love for postal stuff, let me be real clear: everything in your life is influenced by notions of how cities are built—what kind of transportation you procure for yourself, what sort of cultural opportunities you have and are willing to put money into, the food you eat, everything. Start thinking about cities now; buy this book to kickstart the noodling.

Interstate 69

by Matt Dellinger

Speaking of cities: here's a good counterpart to Rybczynski's latest. Take a second and just think how cities come to be: New York's there because of shipping, ditto LA and San Francisco and Seattle. On the interior, cities have been best founded on rivers—shipping again—and then, once railroads grew shoulders, some cities got established because of those routes. And then, of course, after boats and railroads came cars, and so now there are cities based on, sure, highways. Easy proof: think of the 'best' suburb in whatever big city you're most familiar with—is it proximate to the city based on highway travel time? Likely. I grew up in Saint Paul, and home prices diminished by suburb as each moved a ring further from the city (the etymology for the word idiot, by the by, is someone who lives beyond city walls: density and proximity to the city has been significant since the start).

Anyway: Interstate 69 is real, and would cut through southern Indiana—would, in fact, be an international highway, running from Mexico up through Texas, north through Indiana and up into Michigan. What good would a highway like this do? Well, think of the two big things it could provide: quick and easy shipping between Mexico and Canada (hence its nickname the NAFTA highway), and it could also pump a bit of blood and life into otherwise pretty wiped-out towns along its route. Of course, these two needs and benefits could be viewed as in opposition—it's an easy claim that small towns have had hatchets taken to them precisely because of NAFTA (plus it gets deeper: making the highway provides employment to US workers…even though what they're building will, in all likelihood, further undercut what manufacturing jobs remain in the country). There is, of course, no answer.

There is also, presently, no completed I-69: it exists in parts and fragments, unconnected and made whole. Dellinger's book is fantastic reading regarding the pros and cons of such an undertaking and, though it's a fairly common publisher's cliche, the story of I-69 is a pretty tricky mirror and one can't help, on reading Dellinger's great book, but find oneself reflected back, good and bad sides all. Read the book.

December 5, 2010

Let's try this again…

A review of Denis Johnson's Nobody Move

(Note: I originally claimed that there had been very little prehype surrounding the release of this book. Turns out I just don't know where to look for prehype. Mea culpa)

Denis Johnson is one of the few fiction writers today with the maddening ability to move seamlessly between writing styles in a manner that doesn't come across as gimmicky. You've got the wonderfully bleak Tree of Smoke, which won the National Book Award in 2007; Jesus' Son, which manages to merge the ambitions of poetic prose and screwball comedy; the dystopian Fiskadoro; and academia. However, as many Johnson fans will attest, it isn't so much the case that the author jumps from style to style as much as it is that he seems to embrace all styles, all genres, as appendages of some larger indefinable whole. His comfort zone has no boundary which, for those of us foolhardy enough to have made a career out of writing, is both demoralizing and phenomenally invigorating.

In Nobody Move, Johnson throws his hat into the pulp/crime ring, and as one might expect, the result is spectacularly fun and moving. The book, while grim and delightfully blunt and carved from a very Chandleresque model, somehow manages to sidestep all (or at least most) of the cringe-inducing clichés associated with the genre, while still employing those customary guns-and-gangsters tropes that make guys like, say, Elmore Leonard great guilty pleasure reading. Part of this is due to the author's understated prose style, the Hemingwayish sparseness that allows the characters' actions to speak for themselves; those brave souls who made it through Tree of Smoke with their faith in the human spirit still intact can certainly attest to this. In this regard, Nobody Move is certainly no exception.

On the surface, the novel's protagonist Jimmy Luntz is the prototypical crime novel Good Guy: a down-on-his-luck gambler with a sharp tongue and a fondness for Hawaiian shirts. He even sings in a barbershop chorus. Why a barbershop chorus is anyone's guess. Johnson never actually ties this particular character trait into the rest of the story; Luntz just happens to sing in a barbershop chorus, end of story. Which is kind of brilliant, inasmuch as it's one of the most of literarily unusual things about him and, perhaps not coincidentally, the thing to which Johnson devotes the least attention. This is one of the many ways in which the author crafts wonderful characters in all his books: the most ludicrous details and qualities always take a backseat to the more commonplace ones, which teases out the reader's curiosity.

To be sure, Luntz is not, by any conventional standard, a decent person; he's only Good insomuch as he spends most of the book being chased by the less-dimensional but equally fascinating Gambol, who Luntz mistakenly shoots in the leg at the beginning of the book. The reader isn't rooting for Luntz because of his bumbling Forest Gumpishness; he/she is rooting for him in spite of it. In fact, between Luntz and Gambol, it is nearly impossible to distinguish which character is "Good" and which is "Bad," beyond the fact that the former occupies the central role.

This is what makes Johnson's characters so compelling: even the flat ones seem to know that they're flat. They possess an ethical awareness that flies in the face of the traditional crime novel formula. The book may masquerade as a disposably fun crime novel, but on a deeper level Johnson isn't concerned with the concept of Good vs. Bad so much as he with what these ideas even mean.

[image error]What I mean is: there's never a longing on the part of the reader for anyone to get what he or she deserves, primarily because we don't know what they deserve. Because really: what do barbershop chorus vocalists and murderous heroines and gay saloon proprietors deserve? What fate would be appropriate for Juarez, the shadowy dealer for whom Gambol collects; or for Anita Desilvera, Luntz's protagonist counterpart/unwitting-victim-in-a-financial-scheme-turned-murderer? In the context of the book, these just aren't relevant questions. What is relevant are the ways in which these characters slyly maneuver the strict parameters of the genre without being overshadowed by the clunky momentum of plot. While there's very little love or even and inkling of friendliness between any of the major characters, there really isn't that much animosity, either. At least, not as one might expect. Even Gambol, in his efforts to track down Luntz, makes it clear that it's just business, nothing more, as evidenced in the opening scene in which the former confronts the latter in order to collect on a debt (this is also the scene that sets the plot in motion):

"So hey," Gambol said, "you are in a barbershop chorus."

"What are you doing here?"

"I cam here to see you."

"No, but really."

"Really. Believe it."

"All the way to Bakersfield?"

That lucky feeling. It had let him down before.

"I'm parked over here," Gambol said.

Gambol was driving a copper-colored Cadillac Brougham with soft white leather seats. "There's a button on the side of the seat," he said, "to adjust it how you want."

This is how the book distinguishes itself from the typical crime novel track: whereas in most books of its ilk the tension arises from the question of how the Good Guy is going to thwart the Bad Guy, the principle questions in Nobody Move are a bit more complex: Who, exactly, is supposed to get thwarted, and why? Action is a secondary consideration here; Johnson's focus, as always, is the characters, which despite occupying very customary roles, bring with them a depth that renders all the guns and death and sex as minor footnotes in what winds up as a very dramatically engaging novel.