Weston Cutter's Blog, page 32

March 10, 2011

Jim Moore's Reasonable Gorgeousness

I did not see Jim Moore's Invisible Strings coming. I mean every permutation of that phrase. One of the tricky joys of not seeing something coming is that there's compounded surprise in store, once whatever's coming finally arrives. The doubleness of wow-is-that–wait-it-seems-like–wait-a-second, that multivalent joy of perception, etc.

I did not see Jim Moore's Invisible Strings coming. I mean every permutation of that phrase. One of the tricky joys of not seeing something coming is that there's compounded surprise in store, once whatever's coming finally arrives. The doubleness of wow-is-that–wait-it-seems-like–wait-a-second, that multivalent joy of perception, etc.

Here's my favorite line from the book: "After that,/ just attention to detail, plus touch." That's from the poem "How We Got Used," which is short enough to merit copying in full here but which, honestly, you owe it to Mr. Moore and yourself to read it as part of this quietly amazing collection, this collection which tosses sparks so casually it's easy to read through and simply nod along, going yes, yes as the book (seemingly effortlessly) grows larger and larger in spirit, as it gets more and more colossally gorgeous, linguistically, on the page.

Here are the first half-dozen lines from "After Dinner":

For many years, unable to speak the language,

I have sat silently at tables with Italians.

Tonight, too. But this time I don't mind.

Joy enters the voices. Then sadness.

We sit in moonlight, drink wine

until I understand every last word.

One of the things were best equipped for—through songs, movies, pop culture at large—is unreasonable gorgeousness, unreasonable amazement (bitchy beauty, savant brainiac, hyper-competitive athlete). It's less common, seemingly, to experience totally reasonable gorgeousness—to experience beauty which doesn't demand so much to open the doors of its delight. It's weird even talking about this—that old quote All things excellent are as difficult as they are rare comes to mind.

But here's the thing: Maybe for Jim Moore, the excellence he's lassoed and put on the page has been difficult. Certainly, there had to be much work involved in these finely-crafted short-lined marvels. But for us, for the readers: the difficulty includes nothing more than just reading the book.

Here's the first half of "If I Could Have Been a Buddhist,":

I would have accepted humbly,

without judgement, the world

as it was given:

the whisper

of my sister's voice on the phone,

telling me of her friend's murder.

Jim Moore's poems are tricky masterpieces of revelation. There's little that's binary in the work—there's not longing and then longing satisfied. Look again at those lines above, from "After Dinner": As of the moment "Joy enters the voices," the reader's tossed timeless—perhaps joy enters voices every time. Look again: the claimed first-line problem is he can't speak the language; he still can't, by this chunk's end. Maybe every time he can, drunk enough, understand every word. I'm not saying that's what happens in the poem: I'm saying simply look closely at the structures Jim Moore makes, and take just a second and be thankful you're alive in a world in which someone can make such simultaneously rigorous and flexible structures, such perfect little machines of offering.

Jim Moore recently answered some questions, over email, and they're below, and I just want to note, before walking fully from the book, that Invisible Strings is one of the best, most generative and good books of poetry I've read in I don't know how long, and it takes roughly 45 minutes to read through it at a good, adult pace, and I've read it now 1) in bed 2) on a couch 3) standing in the kitchen, and have paged through it lots otherwise, and reader know deep down: this is a massive book of lasting gifts. You're a fool not to read it.

1. First, in the huge/general sense: what are some touchstones/influences for you? Please don't feel like this has to be the name-your-favorite-writers question—any art form applies, any anything applies (if you're hugely influenced by, say, the way the MN Twins are playing, by all means, say that).

I suppose most of my influences do come from the work of other poets. What drew me to poetry initially, as a young man, was that contemporary poets spoke directly and powerfully to things that mattered to me. It was shocking to me– I had no idea that there was an art form that could do that.

I remember sitting on the floor of a bookstore in Norman, Oklahoma reading Kenneth Rexroth, and feeling that it was such an amazing thing that he was doing, writing passionately about all the things that mattered to me–love, nature, identity–as if it was the most natural thing in the world. And, of course, it WAS the most natural thing in the world. From that moment on I was hooked.

One huge influence is the kind of moment which connects your own personal life to the larger life around you: being at La Guardia airport when a bomb went off, killing 12 people, going through the Vietnam War (and especially being in prison as a draft resister during that time), and so on.

Anything that takes me out of myself is a major blessing and important influence: passion, love, nature, particular cities (Venice, Calcutta, New York, Spoleto) and places. Blizzards work beautifully this way, as do mountains, the sea, the plains, certain rivers…anything that reminds me forcefully that my own ego is not the be all and end all. Of course, poems by poets I love do that very well.

1.1. Wait: what? Can you talk more about being a draft resister?

[There's] a longish poem from an earlier book (FREEDOM OF HISTORY) called "For You" which pretty much tells the story of how I ended up in prison. (It appeared in Pushcart and then more recently in the 'best of Pushcart" anthology). I had a teacher exemption but then two of my ex-students were killed in the War and I just felt I couldn't continue to cooperate with the Selective Service/draft system, so I returned my draft card and as a result was drafted. I refused induction and ended up in prison for ten months. I have another long poem, "With Timmy In and Out of Prison," about that experience.

(ed's note: Jim graciously allowed for quotation from his "For You," but lots of that poem's already been quoted at the until-now-to-me-unknown Pirene's Fountain, which had a huge feature on Moore in their last issue, and you'd be a fool to not read every last thing there–they interview Mr. Moore as well, and write an incredible overview of the man's work).

2. You may get to this in the above Q, but it seems like there's a fair dose of Ammons, Jack Gilbert, and Cid Corman in your work—yes? At all? Who knows if this Q'll even work.

Gilbert, yes. But not Cid Corman (except in his translations from the Japanese), Ammons, not so much. So many poets have made a huge difference to me, especially poets from other cultures. Reading poetry in translation has been, for me, a little like leaving the ego behind in the way I describe in the above question: I get away from American poetry's nervous tics, almost automatic ways of working. Japanese and Chinese poetry has made a huge difference to me. I certainly couldn't have written INVISIBLE STRINGS without having read Saigyo, Buson, Basho, Taneka, Du Fu, Li Po, Wang Wei and quite a few others. But also Polish poets, Scandinavian poets, Latin American poets and ancient poetry from many cultures.

3. How important is geography to you? It comes up lots in Invisible Strings, and your bio notes list you as dividing time between the cities and Italy, and I'm just curious about your take on place (or landscape, or latitude, whatever).

Geography is extremely important for reasons mentioned above. I do not necessarily write about a place when I am in it, but the place becomes a way for me to gain perspective on my own life and culture. In general, I feel like an outsider wherever I am so living, so that staying in a place where I am a true outsider actually feels very natural to me. It is easier, in other words, to feel like an outsider when in Calcutta than when in St. Paul where I feel as if I SHOULD feel at home. Being in a place strange to me reminds me to look, delights me with its surprises, quirks, mysterious ways (mysterious to me) of doing things.

4. Can you talk at all about the structure of your poems? This is one of the really crappy aspects of not knowing more of your stuff—I don't know if this style/pattern you use in your work, the back-and-forth tabbing in Invisible Strings, is something you've always done, or a new thing. But I suppose regardless of how long you've used the form: can you talk about how you came to it? (I'll confess a bit of an obsession about form lately).

The back-and-forth, alternating short lines with longs lines is something new and started about six years ago. I was at the beginning of a period when I knew that I would be travelling a lot and so decided I wanted to write short poems since I was likely to have short periods of time in which to work. The step ladder, tabbing of lines came unbidden. At the time I began writing like that I didn't know why, just knew that it felt right. I realized later that the alternating and shifting line length mimics for me the act of walking, long stride, then short stride. Once I started working that way it felt deeply satisfying; for me, there is something more rhythmic about it, like the rhythm that happens when running (I'm a fairly fanatical jogger) rather than having each line start flush left. Really, it's a body thing probably more than anything else.

This book is also a return to writing shorter poems, something I did a lot when I started working back in the late 1960s. It's a form I've always liked, both as a reader and a writer.

5. There's this way in which Invisible Strings seems (often) to be meditating on ways in which the speaker can earn or deserve the grace he's got. Is that something you're aware of or aiming for? Is there any overarching/-whelming ideational thing driving the poems themselves in this book?

What an interesting observation! I really hadn't thought about that, but I do believe you are on to something. As a son of the Scottish-Irish protestant world I may carry around a keener sense of guilt than some. (Another reason I love Italy is that I can get away from that mentality entirely.) I suppose the poems are partly a way to get out of the "right-and-wrong" way of looking at the world.

6. Can you talk about music's importance to you, particularly the quietness of music (you named Bill Evans, so I have to ask).

Well, I grew up in the 1960s so music was key. All the usual rock and roll icons, maybe especially Dylan. I came to jazz later but it's probably the form I feel closest to now though Beethoven's late Quartets and his late sonatas are always ways for me to remember just how powerful art can be. Listening to them is at once humbling and exalting. I sometimes write to music, but never music with words. Bach is good for me that way; his poise settles me down.

7. This might get too hairy to be answered clearly, but there's this great aspect of distance in Strings—the "absence courted by strings" in "Viola," thinking June will make you happy in May. I'm not even sure what the question might be in this–maybe it's got to do with geography and you'll have already answered this–but I'd be curious about the generative aspect of distance and longing in your stuff.

Right you are: I'd more often rather be sitting behind a window looking out at the world rather than being in the world! I suppose that's something a lot of writers feel. Distance–that feeling of distance–is a basic to me; a thing to be honored but also sometimes to be left behind. When I sit down to write I am really sitting down to find a way to connect with the world (and with my own interior world) in an intimate way.

One way to do this is to begin by acknowledging how powerful a factor distance is in my life. It's also why I read poems: if I connect to a poem in a deep way then distance disappears. I love travelling because it is a way to begin with distance as a given (you are going far away) but if the travelling goes well at all, you begin to connect with the new place in unexpected ways. Isn't that what poetry does? I think of Bishop as an inspiration and mentor in this context.

Oddly enough, I often feel more connected to the world (feel less distance from it) when I am in solitude than when I am with others. I spend too much time, when with others, trying to say the right thing, psyche out the dynamic of the particular social situation. One reason I love teaching poetry is that it is a way to be simultaneously public and private, to be with others in a social context but at the same time–because we are talking about poetry–solitude/soulfulness/loneliness is an equally important part of the equation.

8. Please, for as much or as little as you'd like, talk about what it's like to live with/love/be married to a visual artists. Does that sort of life make you re-view your own work in ways you find valuable? That sounds awful–I take it back. Here's the thing: you live with someone who 1) takes pictures (and therefore whose art is "real" in ways painting isn't real, in that photos are visual transcriptions, at least as most of us understand them) and 2) takes pictures of you. How's living as both subject and object? This is messy–discard this question if it's going too many directions. I'd just be curious about all of it.

It's a steep learning curve for a writer to live with a visual artist! I love how we connect at the level of being committed artists, but at the same time we work in such different ways that it sometimes amazes me and makes question, in a helpful way, my own way of working. It's helpful living with another artist of any kind because they understand the particular obsessiveness of the artist, the crankiness and need for solitude often involved…and all the rest of it.

I don't think photos–at least not an artist's photos–are a visual transcription of the world, but much more an imaginative reshaping of it in the way that writing is.

I'm so used now to being a subject of JoAnn's photos I hardly think about it any more. It's an opportunity for me to zone out, to take a nap, to just be. At first, of course, it seemed odd and exotic, but that stage is long past. A couple of years ago I wrote a statement about all this for site at the Smithsonian called Click. Here's some of what I said there:

My wife, JoAnn Verburg, has been photographing me for twenty-five years. As soon as we became serious about each other it started and though there are long periods where she doesn't photograph me, eventually she wants to work with me again.

Just as her approach to photographing me has changed over the years, my attitude as the model has changed. At first, when we were falling in love, I felt flattered that she wanted to photograph me. No one had ever looked at me with such intensity and for such long periods of time. I've heard her say that photographing me—some of these pictures were quite large heads—allowed her to get used to the idea of a big head waking up next to her each morning: it was a way to get to know me using her medium as a tool.

I suppose that being her model was also a way for me to get to know her as well: because, after all, she was not just observing me, I was observing her. Over time, my response to how it feels to be photographed has ranged widely: sometimes it has bored the hell out of me, other times it has put me in a meditative state (after all, when you're being photographed with a large format camera and if you can't move for thirty or forty minutes, it does encourage an inner stillness as well as the outer stillness); most often—and most prosaically—it has put me to sleep. Literally. And this has suited her purposes as a photographer since she has focused on photographing me while I sleep.

I don't know that she would agree with what I am about to say but I believe that one of the reasons she so often photographs me asleep is that she is "practicing" for the day when I will die. As a poet, I believe that the most challenging conversations I have in my work are often with death. I think this is true for a lot of artists, whether writers or artists working in other mediums.

Sometimes JoAnn says, "Art is a wish." What her wish is, as an artist, I can't say for sure, but my wish, as a model, is that for the period of the time I am being photographed I might become someone who is somehow different from the man he usually is. While sometimes a nap is just a nap, occasionally it is more than that and I wake from it with a calm kind of clarity that visits rarely but is all the more welcome for that.

9. What's the view out your window?

Right now I am in Colorado Springs. I can see Pike's Peak in the distance, but closer up, railroad tracks and a park, a creek, people running in the park, several homeless people also in the park. I love this view. Here's something the wonderful translator David Hinton wrote in his introduction to THE SLECTED POEMS OF TU FU: "Tu Fu explored the full range of experience, and from this abundance shaped the monumental proportions of being merely human." Right now there is enough going on outside my window for me to do that for the rest of my life. I feel both grateful for and haunted by "the monumental proportions of being merely human."

March 8, 2011

Sad Sad Sad

I try to keep this relatively objective and book-focused, but I found out this morning that one of the absolute giants in my life, Jim Bartell, died this past Sunday. If you knew him, send condolences to his children. If you didn't know him, take a moment and send love and thanks to whoever has helped you become who you are—whatever mentor helped light the way. Let me be 100% clear: without Jim, I wouldn't have the life I have—wouldn't be writing, wouldn't be running this book blog, any of it.

I try to keep this relatively objective and book-focused, but I found out this morning that one of the absolute giants in my life, Jim Bartell, died this past Sunday. If you knew him, send condolences to his children. If you didn't know him, take a moment and send love and thanks to whoever has helped you become who you are—whatever mentor helped light the way. Let me be 100% clear: without Jim, I wouldn't have the life I have—wouldn't be writing, wouldn't be running this book blog, any of it.

March 7, 2011

Rap as Social Policy, Plus Immigration

The easy sell for this—that it's a necessary purchase for those of us who don't usually get through 24 hours without the occasional hova loop dominating gray-matter space—doesn't do this great book justice. Wait, let's back up: I assume everyone knows Jay-Z. Subject of a really profound 2001 profile regarding corporate rap, husband to Beyonce, maybe the single most accessible rapper in the history of the art, etc. For those of us in the late-20′s/early-30′s demographic, we might have different associations regarding Jay-Z than those held by younger folks: if you (like me) remember him mostly for his "Can I Get A…" or "Big Pimpin," his public self in the last while—marraige, less aggressive rap (or certainly less misogynist)—can strike odd. Don't get me wrong: I love Jay-Z's old stuff—I'd be happy to nerd out and be the dorky academic who talks at length about how "Big Pimpin" is doing more interesting metric stuff than all the poetry published in the last two years—it's just that this guy who promised "not for nothing, never happen, I'll be forever macking" is now, well, a liar.

That schism is actually one of the reasons this book is so valuable and great: Jay-Z does a tremendously satisfying job of squaring his various selves, and, in doing so, putting in some serious miles of thought and consideration about contemporary urban social issues. No more than a handful of pages ever pass without him ever mentioning his former life as a drug dealer; likewise, no more than a handful of pages ever pass without him mentioning why and how be became a drug dealer. Which means, aside from being a gorgeous art book (there's tons of photography, and the pages are thick like a coffee table book), Jay-Z's Decoded is a phenomenal, first-person account of failed social inner-city social policies from the last quarter of the 20th century.

I'm not saying this book's got to be read that way—if you like the guy's stuff, get the book, if only to read the footnoted lyrics he includes in each chapter. But this is not just some vanity project of a book by a world-famous rapper detailing stories of his money and his parties or whatever: this is a serious book that seriously considers black male inner-city life in America, that seriously considers the work of Basquiat (and Jay-Z's analysis of the work, and his appreciation and understanding for it, is great to read, even if it's funny to note how offhandedly he mention that he owns some of the artist's work [the book's cover, as an aside, is a Warhol print]), that seriously considers not just the drug hustle, but how and why it got to be exactly what it is (it's easy to read statistics in a newspaper about the disproportionate numbers of blacks locked up vs. whites, harsher sentences for crack than powdered cocaine, etc; those same stats take on a different life when presented by someone who was there, in them, a could-have-been-one-of-them).

And those lyrics Jay-Z footnotes and explains? Here's what's so awesome about them and that process: in trying to disentangle info and influences, Jay-Z actually proves, through his own lyrics, how inextricably tied rap is to the culture that birthed it (or, at least, how inextricably Jay-Z's rap is tied to his own culture). In lots of ways, the book feels like a magic knot of a trick: all these aspects of the man and his music are interconnected, and there's no way to understand one aspect without bearing in mind several other aspects simultaneously. You don't have to care about Jay-Z, or rap, that's fine, but unless you're insane or heartless or worse, you should care about the conditions in inner cities, and there are a handful of exceptional books that shine stark, clarifying light onto those stories, and Jay-Z's Decoded is one of the best them. (Also: this book should be necessary reading for anyone who watched The Wire, and certainly for anyone who loves Richard Price's novels, particularly Clockers).

Speaking of Social issues: Helen Thorpe's Just Like Us is the single-best book on immigration policy I've read. What's so fantastic about Just Like Us is that Thorpe has taken this hairy, complex issue—illegal immigration, specifically regarding hispanic immigrants—and has, instead of offering some tract or wonkish overview, addressed policy by addressing the stories of those effected by the policies in question. And what stories? Those of four high school girls in Denver.

Speaking of Social issues: Helen Thorpe's Just Like Us is the single-best book on immigration policy I've read. What's so fantastic about Just Like Us is that Thorpe has taken this hairy, complex issue—illegal immigration, specifically regarding hispanic immigrants—and has, instead of offering some tract or wonkish overview, addressed policy by addressing the stories of those effected by the policies in question. And what stories? Those of four high school girls in Denver.

Lest you believe that more intense or moving stories could be found by focusing on immigrants in Texas or Arizona, the stories of these four young women are as riveting as anything anyone could possibly drum up. Two of the young women are illegal immigrants—they were born elsewhere and brought across the border illegally—and two are legal. For those of us with little to no experience of how massively shadow-casting those terms are, and the shocking ways in which such tags shape identity, Just Like Us is less eye-opener than perception destroyer (for instance: one cannot get a driver's license without a birth certificate; one can't buy a plane ticket without some form of ID; day-to-day aspects that those of us born in the US so take for granted are complex, terrifying ordeals for these people).

Compounding the flat-out riveting aspect of this story is that Thorpe's husband was, in the period she's writing of (as he still presently is), mayor of Denver—Thorpe literally had as insider-ish a seat as possible. What Thorpe's biographic stake in the story precludes is Just Like Us mimicking that most perfect of life-story-as-policy-portrait masterpiece, Random Family by LeBlanc. I'll fess up to wanting Just Like Us to be more like Random Family, simply because, like anyone who's read it, I long for more writing like LeBlanc's (plus this book's almost asking for comparison–look at the covers of each book). However, Thorpe's vivid, personal telling of these lives, and the policies that so sharply and massively affect them, is phenomenal, refreshing, and illuminating. I'd expect most of us don't have 100% clear notions of exactly what should be done regarding immigration in this country—I at least am not 100% clear. This book, in the best ways, complicates the issue for me, and thankfully drags the issue from the realm of the theoretical. This is a riveting, necessary book.

March 3, 2011

Other Places/Things

[image error]In case you're hankering for more reviews and poetry and writing about writing, you can check out any of the following:

: Eleven Eleven, where I've got three poems in their latest issue;

: Rain Taxi, where, in the latest iteration of the online winter issue, I've got a review of Gary Noesner's incredible Stalling For Time: My Life as an FBI Hostage Negotiator.

: The Ploughshares Blog, where I've had stuff going up every Wednesday since the year began. The most recent post is a long conversation with Bob Hicok about the word random and its relationship to contemporary poetry; the older stuff is all interviews with awesome writers like Matthew Zapruder, Jennifer Boyden, Olena Kalytiak Davis, and Rhett Iseman Trull, editor of the excellent Cave Wall.

Back to regular reviews shortly.

February 25, 2011

'Til Somebody Kills the Lights': A review of Ryan Adams' III/IV

A while back, a friend and I were discussing whether or not Ryan Adams was overrated. My friend claimed that he was, his reasoning being that despite Adams' extensive catalogue, and despite the fact that nearly all of his songs could be classified as "good," he had yet to produce anything with any real staying power–nothing that might qualify as "great." Whereas most of the truly great songwriters manage to generate at least a couple of signature songs—that is, songs that more or less emblemize the grandness of their talent, like Neil Young's "Needle and the Damage Done" or Leonard Cohen's "Hallelujah,"—Adams' closest blush to this might have been "When the Stars Go Blue" off his album Gold—and even that was mostly the work of Tim McGraw, who covered the song on his second Greatest Hits album in 2006.

A while back, a friend and I were discussing whether or not Ryan Adams was overrated. My friend claimed that he was, his reasoning being that despite Adams' extensive catalogue, and despite the fact that nearly all of his songs could be classified as "good," he had yet to produce anything with any real staying power–nothing that might qualify as "great." Whereas most of the truly great songwriters manage to generate at least a couple of signature songs—that is, songs that more or less emblemize the grandness of their talent, like Neil Young's "Needle and the Damage Done" or Leonard Cohen's "Hallelujah,"—Adams' closest blush to this might have been "When the Stars Go Blue" off his album Gold—and even that was mostly the work of Tim McGraw, who covered the song on his second Greatest Hits album in 2006.

However, as I explained to my friend, this is the very same thing that I think makes Adams such a phenomenal songwriter. The key word here is good: given the volume of tunes that the thirty-six-year-old so breezily dashes off year after year, you'd think you'd be able to find one or two that fall short of the mark, but there hardly ever is. Moreover, this seems intentional. It is almost as if Adams is burdened by the understanding that a great song—and even a good one sometimes—can ruin a career just as easily as it can launch it (for example: Nirvana's "Smells Like Teen Spirit" is a great song, and yet as the band has admitted, it also represented the beginning of their collective end).

So, okay, let me be completely upfront about this: I love everything Ryan Adams does. Everything. There was no chance I was not going to like this album. I would listen to the man read from the phonebook. Even his infamous phone message to rock critic Jim DeRogatis, in which Adams throws a tantrum befitting of a tween about DeRogatis' review of one of his shows, is endearing in a way that I can't quite figure out.

There was, however, some doubt as to how much I would like it. Because as any Adams' fan will tell you, as prolific he may be, he has put out a few clunkers in the past (see: 2008's Cardinology).

may be, he has put out a few clunkers in the past (see: 2008's Cardinology).

Fortunately, Adams appears to have come to terms with the schizoid nature of his music: III/IV plays like a greatest hits album, pulling from his impressive portfolio of styles. There are poppy, fuzzed-out tracks like "No" and "Kisses Start Wars," which hearken back to the grungy musical aesthetic of Rock and Roll; there's the elegantly somber "Ultraviolet Light," which could pass as a B-side from Cold Roses; and then are tunes like "Star Wars," whose jarring shifts between time signatures preclude it from any classification but, at the very least, make for a very interesting listening experience.

Is III/IV Adams' best album yet? Not exactly, but it's up there. In a way, he seems to have lost all concern for classification and marketing and genre, and the result is a spectacularly enjoyable album that tows the line between artistic conscientiousness and glitzy commercial appeal. Adams' place in the music world is no place at all, that indefinable space between genres.

Most important, however, is how effortless the album seems. That most of his songs, particularly those on III/IV, feel as if they were crafted in under ten minutes is precisely what makes them so enjoyable: they're good in spite of themselves. Even the less-than-spectacular tunes, the real dregs of his catalogue, outshine most of the capital-G "Great" songs cluttering up the charts. And I realize that I'm committing one of the cardinal sins of music reviewing here in that I'm gushing about the artist while commenting very little on the album in question, but I guess that's sort of my point: it's next to impossible to say anything true about Adams in the context of a single album in that each of albums represent only tiny niches of his songwriting abilities. There is a fleeting quality to his music, something pointedly unobtrusive, like a half-second-too-long glance from a stranger on the street, each song an anthem for the moment at which it's played. Unlike some of his contemporaries, Adams isn't partcularly interested in the future; rather, he's interested in trying to capture some ephemeral aspect of the present.

Most important, however, is how effortless the album seems. That most of his songs, particularly those on III/IV, feel as if they were crafted in under ten minutes is precisely what makes them so enjoyable: they're good in spite of themselves. Even the less-than-spectacular tunes, the real dregs of his catalogue, outshine most of the capital-G "Great" songs cluttering up the charts. And I realize that I'm committing one of the cardinal sins of music reviewing here in that I'm gushing about the artist while commenting very little on the album in question, but I guess that's sort of my point: it's next to impossible to say anything true about Adams in the context of a single album in that each of albums represent only tiny niches of his songwriting abilities. There is a fleeting quality to his music, something pointedly unobtrusive, like a half-second-too-long glance from a stranger on the street, each song an anthem for the moment at which it's played. Unlike some of his contemporaries, Adams isn't partcularly interested in the future; rather, he's interested in trying to capture some ephemeral aspect of the present.

February 15, 2011

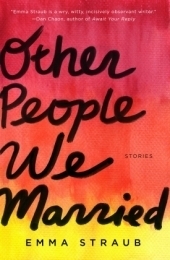

Three Quicks and FREE BOOK

Other People We Married

by Emma Straub

Other People We Married

by Emma Straub

There's lots I want to say about this debut collection of stories—that the stories themselves are lithe and move well, and that there's a terrific sadness to lots of them (a generative sadness though, or one which fractures light in not-unpleasant ways—L. Moore territory, in other words), and that the title story starts with a shockingly great trio of sentences ("The advertisement had been gloriously distorted. What did it say, 3 bed/2 ba cottage on the water, w/boat slip and dock, private beach. Great for families, was that it? It was like something Edward Gorey might have drawn, with a little girl skipping to her death.")—but before we get to the book proper, let's take a second and celebrate the actual physical book. Because this is the first paper release from 5 Chapters, which, as anyone who consumes fiction'll let you know, has, in the last several years, become a necessary online spot for great fiction. And the book is fucking gorgeous, one, but also, two, let's just acknowledge that this book, the actual, physical object, must, if nothing else, upend the obvious and dreary conversation about the shape and direction of books—everything paperless, multi-touch narratives, whatever. 5 Chapters started online, and now, look: a book. Keep this in mind next time you want to moan about the future of reading and print.

Back to Straub: oh just read the thing. Do you need more reasons to part with the $15 necessary to secure yourself a copy of this book? She's great. The stories are weird things, narratives stuffed with bb guns, strange neighbors, quiet. There's lots of midwest, too, which of course I'll claim makes it amazing, but you can find your own reasons.

How to Write a Sentence

by Stanley Fish

I was sold on this book frmo the start, because it's Fish, and because he could write about cracked gaskets and I'd be thrilled and would gladly read along, but then, on page 33, I got totally suckered and for-sured into this book: Fish uses a metaphor for learning the rules of writing that I've used before. You shall tie yourself to forms and the forms shall set you free, he writes, and then mentions the phrase "wax on, wax off," which I needn't tell anyone from my own demographic what that's referencing, and that's really all it took for me to stay 100% invested in this book—that Fish, in writing about one of the most basic machines of language, bothers to make room for Ralph Macchio.

Oh, and, of course: you'll understand more about sentences after reading this, no matter your skill level, than you'll believe. Seriously.

This is an odd memoir, or wasn't, anyway, exactly what I expected: Allen Shawn's the child of Wallace Shawn, the famous New Yorker editor (go check who Salinger dedicated Franny and Zooey to), plus also he himself is a composer, teaches at Bennington, and is the author of Wish I Could Be There, another memoir which (apparently–haven't read it) focuses more on his agoraphobia and anxieties (which makes the title a dark little joke, of course).

I shouldn't say Twin wasn't what I was expecting, actually, because I don't know what I was expecting. I got that the book was about Allen's sister Mary, who happens to be autistic—but that's a cheap sell; it's not the book you're now imagining, about a fraternal twin writing about his impaired twin. It's deeper than that: this book is about the way phobias and hurt thread their way through families, and how our relatives inevitably act as mirrors and all but demand we ask questions of ourselves and our blood and how and why things are as they are. I certainly didn't expect to be moved by the almost shocking stiff-upper-lip-ism that the Shawn family seems to have lived with and for and through for so long. It's a strangely moving book, Twin is: I didn't know what I was getting into when I started it and, even now, I'm not 100% sure what I was into when I read it. But I'm glad I did.

AND NOW, A CONTEST: I have a free copy of Twin to give away, courtesy of the good people at Viking. TO ENTER: Leave a note in the comments about who your twin is—if not by birth, than by some other thing, make it up, whatever. CONTEST RESULTS: At 10pm tonight I'll draw a name at random from the day's commenters. Good luck, thanks for reading.

February 11, 2011

The Four Stages of Cruelty=Great Fiction

The Four Stages of Cruelty

by Keith Hollihan

The Four Stages of Cruelty

by Keith Hollihan

I have to admit something: I don't necessarily go for novels. This has been a slowish development, and I imagine it's common for lots of us who read a lot. Here's what happens: we read craploads of great novels through our twenties, which is rad, and then we've built ourselves little palaces of greatness–our favorite books are almost all novels (Gold Bug Variations, Infinite Jest, Bel Canto, Giant's House) and then…then we keep reading novels, of course, but the dirty secret is that great novels are rare, insanely, impossibly rare. Every year we get maybe a dozen real great, lasting ones—this past year there was Visit From the Goon Squad and Skippy Dies, for instance, but off the top of your head, how many more? Again, I'm talking great—there are plenty of good novels (hi there, Freedom), but great—stuff that lasts, that holds up—is harder.

I'll admit that I don't know if Keith Hollihan's Four Stages of Cruelty will hold up or last, if it's great, but holy damn the thing sure struck me as one of the best books of 2010 (even though I read it January of 2011). Here's what's most awesomely weird about Four Stages of Cruelty: it'd be damn near impossible to pick up this book and deduce, from the cover or anything, that it was anything close to a great book—the cover's in black and white, and it's got drawings of prison scenes on it, and a glance at the dustflaps convince that the thing is set in a preison—Ditmarsh penitentiary—and that the book's lead is Kali Williams, a late-30′s female prison guard.

Let me also, quickly, get this bit out of the way: Hollihan lives in St. Paul, MN; I don't have to like him for that fact, but I do.

How to do this book justice. Hm. Here's how Hollihan chose to offer entrance to his intoxicating book: he started the thing with a 1.5 page second-person italicized thing, Let's say your name is Joshua. You're eighteen years old, a quiet student who likes to draw and an otherwise normal person, but you're going out of your mind because your ex-girlfriend won't talk to you anymore and has been hooking up with another guy. It goes like this, the first part, the intro, whatever it is, goes You take your father's gun because you want her to know how painful it feels and how far you'd go to get her back. But when you're finally there, standing in the middle of the living room, nothing works out the way you'd planned. Not that you had any plans. The girlfriend, you realize, is no longer your girlfriend. She's screaming at you to get out, and there's a look in her eyes that doesn't fit with the way you feel. Meanwhile, her new boyfriend has decided to go all Rambo. It gets crazy. You're both fighting over the gun like it's a live snake, and it's pointing this way and that. You just want to get a firm hold on it, put it away, and go home. But Rambo won't let go.

But then he does.

There's more—there's another page of this stuff—but it's worth drawing your attention to because of two things: 1) the intro ends up being a fantastic trick of empathy which Hollihan deploys to get you to give a damn about characters in this book almost by accident, by trickery (it'll be much more clear when you get into the book) and 2) this whole passage betrays an incredibly deep and wise understanding of the actual world on Hollihan's part. We don't necessary talk about this stuff in book reviews, because it's too tricky, but Hollihan's Four Stages is a good chance to talk about the fact that one has to have a massive pool of empathy to draw from to write a good, moving book about people honestly facing difficult circumstances and fates.

Which, certainly, in Four Stages, they do: everybody's staring down the barrel of something tricky and/or hard in this book, from Kari—the radically alone female (one of very few) CO at Ditmarsh, to Josh, the young man whose story starts with Kari taking him to his father's funeral. I don't want to get too much into the plot details because 1) I can't remember everything (this plot's stuffed as satisfying full as a popcorn bag) and 2) I don't want anything ruined. Here's what's necessary to know: Hollihan writes sentences which move like incredibly fast, well-built machines; Dan Chaon (whose fiction I don't think we've ever stood up and shouted for on Corduroy, which is a shame—that guy's a monster master) claims in his blurb that Four Stages is "impossible to put down" and of course he's right—I picked this up on I think a Thursday evening after finishing some other book, and I was done with it before sleep that night. It's insane how the book packs punch and picks up speed. Here's what's also necessary to know: you'll squirm. There's blood and violence—nothing's gratuitous, but it's there. I squirmed. Here's what else: if you read this, you'll be shoving it into the hands of every friend you've got in about a week. Read The Four Stages of Cruelty; decide for yourself if it's one of the greats of 2010. My vote's been leaning yes since I picked the thing up.

February 2, 2011

Chocolate Cancer Devils

The Devil and Sherlock Holmes

by David Grann

Attention New Yorker readers: remember the story from last year, about the Supreme Court of Texas executing that guy who'd supposedly burned his house down, his little girls inside? That was written by Grann. And remember the article about Ricky Henderson? And the one about the Giant Squid? And the one about The Brand, the story of the Arayan Brotherhood? Yeah: all those were by Grann as well.

Look, anybody who reads a good magazine regularly's got his or her own squad of writers always looked out for, always hoped for, issue to issue, and these writers, sometimes, go on to be Big Names—Gladwell, anyone? Grann's the guy who wrote The Lost City of Z, which was a fucking riveting read, and his articles are some of the best, most entertaining things a casual reader's got any right to hope for. Read The Devil and Sherlock Holmes: these essays are gripping, perfectly written, and exactly the sort of things you'll come back to, over and over again.

The Emperor of All Maladies

by Siddhartha Mukherkee

I'm the last person to this party, so probably the less said the better. Look, this book was a top-10 for a whole lot of folks last year, and there's only so much I could possibly say that hasn't already been said about this book. Maybe it's best merely to say that I picked this book up after reading an almost hypnotically good and mostly upbeat book of stories, and not once in reading this did I ever have to stop and think guh, this is too heavy; medical books can do that, can be too much, too morbid, can make one have to confront one's own mortality a bit too keenly. Certainly one has to do that to some extent as well in Emperor, but holy shit is it worth it.

Chocolate Wars

by Deborah Cadbury

Yes, you're reading and assuming correctly: the author of this book has a family connection to chocolate, though the family connection, critical tough it may have been as an impetus, leaves no real trace in the book. Instead, the tale you're welcome to is, certainly, true to the subtitle—the 150 year rivalry between the world's greatest chocolate makers—but it's also much, much bigger and stranger, less about commerce as we presently understand it (avaristic, endlessly money-grubbing) and more about how commerce was conceived of several generations back.

Meaning what? Meaning the Cadbury family used the fortune it made in chocolate (and the development of milk chocolate is given in Chocolate Wars, and it's certainly riveting) for the betterment of society, as did the Nestle family—schools built, green spaces established and maintained. Awesomely, Cadbury traces these aspects through to the roots—to the fact that these businesspeople were Quakers, and that there were certain obligations that obtained from that fact.

I will say that Chocolate Wars is, at times, a bit dry, a bit stuffy—I'm sure there's a riveting tale to be woven from the development of chocolate from tropical cocoa bean to world-dominating confection, but that riveting tale's not quite what one gets in Cadbury's measured, deep book. Instead, one's left with a stranger, more philosophical story: what responsibilities does a company have to those it employs? To those whose lands it harvests from? Those questions, those ideas, are illuminating and well presented here.

January 29, 2011

A Best + Necessary Read: Revolution

I can't remember how or why I picked up Deb Olin Unferth's Vacation—I'm sure I was excited that it was a McSweeney's book, and that the blurbs were from Aimee Bender and Diane Williams. I don't really know what else there was, though, why I thought to heft the thing, turn those pages. Of course, like every human who has hefted/turned Vacation, I feel desperately, little-kid in love with the thing: the confident ease or whatever it was that allowed Unferth to so blithely craft this narrative that simply did, simply went propelled and which trusted the reader to follow, to get it, to keep up, to trust.

Plus to the above, for reasons having to do with this particular reviewer and having nothing to do with me, know the following: 1) McSweeney's also published Unferth's Minor Robberies in part of that little stories-in-a-box thing (there were I think supposedly 145 stories in that box), the one that featured Eggers and Manguso as well; 2) Deb Olin Unferth sends great postcards; 3) Unferth's presently in New York, teaching at Wesleyan; 4) I'm 100% biased, or compromised anyway, in that the woman blurbed my own book (though I'd like to think I'd be strong-minded/-willed enough to call out a book's badness, regardless of my emotional or otherwise proximity to the author). Anyway, that's just info to bear in mind.

I'm tempted to say that those who should snap quickest up and read Revolution are those who read Vacation, tempted to say that the books are a strange little mirrory combo of Unferth's life, or aspects of it, despite the fact that Vacation is a novel and Revolution is a memoir (subtitled: the year I fell in love and went to join the war). For those who are still getting to Vacation, the story involves a man following his wife who is following another man; things move from Syracuse to Central America; the driving questions (why's he following? why's she?) end up being less interesting than the ancillary ones (what's the nature of searching vs. finding? and the relationship between knowledge and fact? and is there something generative in not knowing certain things clearly?), and the whole book, despite its size, ends up really being a sledgehammer of awesomeness, one which'll knock you as sideways as any book you've let into your life.

I'm tempted to say that those who should snap quickest up and read Revolution are those who read Vacation, tempted to say that the books are a strange little mirrory combo of Unferth's life, or aspects of it, despite the fact that Vacation is a novel and Revolution is a memoir (subtitled: the year I fell in love and went to join the war). For those who are still getting to Vacation, the story involves a man following his wife who is following another man; things move from Syracuse to Central America; the driving questions (why's he following? why's she?) end up being less interesting than the ancillary ones (what's the nature of searching vs. finding? and the relationship between knowledge and fact? and is there something generative in not knowing certain things clearly?), and the whole book, despite its size, ends up really being a sledgehammer of awesomeness, one which'll knock you as sideways as any book you've let into your life.

And yes, certainly, those of us who come grateful and thrilled to Revolution with Vacation in mind or memory (or spleen or wherever it is readers keep old books) will find much excitement. Those Central American scenes in Vacation? There was probably quite a bit of actual first-hand experience that led to them (I don't know why stuff like this matters, the fiction/reality overlap, but I know it's true: Wallace's Jest felt/feels more because of his drug use and tennis playing as the quickest/easiest example). The compulsion/desire to stalk someone, and, through stalking, discover something one believes findable (that's gnarly to write, I know, but we've all done this—it's the hope we'll discover why we want to hang out with someone by hanging out with that person)—that's huge in Revolution, that's everything.

Because here's the story: young Unferth (like early college, 18 or something) decamped to Nicaragua with her Christian boyfriend, the sort of guy all of us know or have met or have maybe been, the one who believes Changing the World is somehow an activity one goes elsewhere for. He wants to go help the Sandanistas claim their country.

Because here's the story: young Unferth (like early college, 18 or something) decamped to Nicaragua with her Christian boyfriend, the sort of guy all of us know or have met or have maybe been, the one who believes Changing the World is somehow an activity one goes elsewhere for. He wants to go help the Sandanistas claim their country.

This may not sound riveting, but it is, emphatically and fully. Unferth's writing's some of the finest, most taut stuff being put on paper in English, and the chapters through Revolution are short, several pages at most, episodic in a snapshotty way. Here, for instance, is "Parade" from page 75:

There was the day in San Salvador that we went to the plaza. It was more or less deserted except for the police forces, the military, and the guardia nacional. We spotted a few citizens moving through. I hadn't wanted to come and now that there was so little to see, I hoped that meant we could leave. "You see?" I said to George. "Nothing here." Suddenly we heard drums, the regular beat of western drumming, and a parade came marching along. No one saw it, except us and the soldiers and a thin line of locals who obligatorily assembled. In my memory it seems as if the parade was going by a few inches from my nose, so large I could see only hands, faces, drums, the white and red uniforms, the sway of the legs of the stilt walkers and the purple material of their costumes, their eyes through the masks. They stopped in the middle of the plaza. The drummers played a marching tune. The clowns and stilt walkers waved and teetered around. Then they all went on.

Please know that this episode is not immediately preceeded by a scene in which George and Deb were headed to the plaza; the chapter immediate before, in fact, was about Deb admitting to her mom that she'd suddenly gotten engaged. This associative (some'd say random) narrative construction—linear but not causal—has been a cool tool among a certain sort of stylist for awhile now, but Unferth's actually using it for larger, stranger ends, too. Of course, what the style does, first and foremost, is force/allow the reader to draw intellectual/emotional connections between disparate events which, because they crowd each other chapterly, end up feeling like they're related: my understanding of Unferth's engagement, and her telling her mom about the engagement, is colored by this weird hyperparade, this thing she didn't necessarily even want to be there for, this thing which so few people saw.

But what the reader discovers as the book wraps quickly to its close is that Unferth's been using this defamiliarizing narrative trick throughout to bring the reader in, to make the reader feel the sort of traceless confusion that Unferth seems to have felt then. Actually, not even (or not only) felt then, in her 18th year, in 1987 in Nicaragua, but in the passage of time since: Revolution is, in the end, an attempt to reckon with the past and with the younger Unferth the present Unferth is. I will submit that however that may sound, written down like that as a boring sentence, the way you'll actually feel, reading it, is too big to name, too expansive and breath-takingly great to minimize. This is a book, fundamentally, about the self, particularly past selves, and if you're reading anything other than this this month, February of 2011, you're making a mistake to every self you've ever had, the one right now and all the ones you could later become.

January 25, 2011

Shameless Elsewheres

For those interested in finding/following Cutterwork in other venues, there's the following:

An interview with Ed Skoog at the Ploughshares Blog. I'll have stuff up there on Wednesdays from now through April–mostly author interviews, but hopefully some bloggier-type things, too;

A review of the latest Adrienne Rich at the Rumpus; and

A podcast/recording of me reading my poem "Winter Prayer" up at the Indiana Review blogspot (called Under the Blue Light)–the poem's from their latest issue which, like all their other issues, is hot as hell.

There's more stuff around or coming soon, but it'll keep. Back to the regular broadcast.