Weston Cutter's Blog, page 18

September 10, 2013

The Hive by Gill Hornby

It’s obvious enough this book isn’t “high art.” It ain’t winning any Nobel Prizes for Literature; it’s not gonna be quoted from or passed down to the next generation. Does that disqualify it from making your reading list? It shouldn’t.

The Hive could be most easily compared to the movie Mean Girls, starring Lilo, screenplay written by the brilliant Tina Fey. Hornby makes no excuses or pretensions about this – a dedication in the book of the book even gives credit to Rosalind Wiseman and her non-fiction guide to female social behaviors, Queen Bees and Wannabes, the book that, surprise, Fey also used as the inspiration for Mean Girls. Looking at the press release that came with the book, the first line (I’m not joking here): “The Hive is Mean Girls for moms.” In bold like that, too, so you have to read it.

Not a mom? It’s cool, me neither. I’d have to argue that The Hive relates more to Fey herself and even her memoir, Bossypants than any film with Amanda Seyfried in a leading role. ((I could go on for awhile here about how strongly I’m convinced that Fey and my closer-in-age contemporary-idol Lena Dunham are The Perfect Examples of American Womanhood Today and how that means, yes, I am going to eat that third slice of pizza, and no, I would not rather have the Skinny Vanilla Latte or date that boring guy with more concrete life goals, but anyway, I’m doing a book review here (sort of), so if you want to hear more on that, message me later. ))

Anyway, what you need to know: The Hive is the novel parallel to Bossypants’ clever, insightful down to the last little detail of one woman eating four truffles while the others stopped at three, self-depreciating yet self-accepting style of the way women live today.

There’s a plot (it’s pretty loose) about an overly exclusively clique serving as a “fundraising for the school” group and the lives of individual members over the course of a rather dramatic school year. The beauty of the novel isn’t in the way these woman all over the course of the story kick out the bitchy “Queen-Bee” character from her commandeering role as chair of the committee, or in the way Hornby ever-so-unsubtly relates the modern woman’s social groups to that of a beehive – these are actually the worst parts and the places were I skimmed through with shame, thinking, “Oh my God, I’m reading Mean Girls for Moms in public.” The beauty of the novel comes as Hornby focuses on one of the moms and her individual struggles, which really, are everyone’s struggles. The beauty is in awkward little scenes, like one in which all the women get out measuring tape, comparing the sizes of their post-children asses, yet getting silent and uncomfortable when the fattest in the room points out that yes, she is the fattest in the room.

It’s better than the average marketed-to-today’s-woman novel – I’m thinking Confessions of a Shopaholic, Eat Pray Love, Bridgett Jones’ Diary, etc. (even though, if we’re being honest, those are not bad books and snobs should give them a chance). It has very little in common with the Clique books girls read in high school (if you have never seen those fake-Burberry covered “novels” with ambiguous photos of Blake Lively-esque girls on the cover, consider yourself lucky.) It has more in common with Jennifer Egan’s A Visit From the Goon Squad than a paperback flush.

What I’m saying is basically, fuck “high-art” for four or five hours, read something that will make you laugh and sigh with common understanding, and give this book a chance.

September 6, 2013

Jami Attenberg’s THE MIDDLESTEINS

The Middlesteins by Jami Attenberg

The Middlesteins by Jami Attenberg

A good author makes you empathize with her characters. It’s a great one that makes you sweat, weep and worry over each choice her characters are making. In The Middlesteins, Jami Attenberg left a weight in my gut with every page.

The story starts with young (but not little) Edie Herzen, age five and already 62 pounds, and follows her growth throughout the years, both emotionally and physically, until she’s almost reached 350 lbs. We follow her love of rye bread as a girl, to the solace she finds in her boyfriend then fiancé then husband Richard Middlestein, the way she replaces Richard’s affections with the more dependable comforts of food, and the escape that Edie finds in a fast-food meal eaten alone.

Here’s the super creepy part: it doesn’t going to matter how much you eat, how hard you diet, Edie’s story is going to freak you out. I mean, it starts out so innocently. This is just a girl who likes food. She likes a warm piece of bread with melted butter spread across the surface; she likes trying the newest sandwich at McDonald’s; she likes eating a great mixture of plates at her favorite Chinese restaurant with a bit of rice between each chopstick-full. It’s not that crazy, right? I enjoy the hell out of a rich, fresh baked doughnut, as I’m sure each of you with a soul and not unreasonable food allergies does as well – does this make us gluttons? Are we too on the path to obesity? It’s a scary trip to see a well-enjoyed meal through Edie’s eyes (comfort, entertainment, often great company) versus through the eyes of those who love her (self-harming, self-mutilating, self-destructive).

Speaking of seeing through other eyes, we get to the chance to do so through the others in the Middlestein family that comes along: there’s Richard, who by the time the story has really started, has left the sickly overweight Edie, posted his profile online and begun looking for someone healthy, young and comfortable. There’s Edie and Richard’s strong and confident, if more than a bit cynical, daughter Robin, the hip one living in a trendy neighborhood of the Windy City, far enough from her parents in the suburbs to feel space, but not far enough for freedom. She’s more than pissed at Richard, frustrated with her mother’s lack of caring about her health and unafraid to wear these feelings on her sleeve. Then there’s their son Benny and his family: his wife Rachelle who would love to take Edie’s care into her own hands; his willful daughter Emily who craves to see more, live more and experience more than her rolling-eyes would ever show, and her peace-keeping twin-brother Josh. Often, it’s not just the stories of Edie’s lunches that are breaking our hearts, it’s the discomfort of the grandkids watching Richard flirt with a woman not their grandmother; the tension of Robin wanting to join the family of one she loves without accepting the sacrifices to her pride that might mean; the way constantly pot-smoking, put it all out of his mind Benny can’t keep the hairs on his head.

What struck me from the very first few pages is just how much Attenberg’s prose is remindful of the family dramas of Jonathan Franzen. Same as Franzen, the novel’s plot is less important than the personal struggles and triumphs each character goes through along the way. There’s a few differences between the two: Attenberg’s female characters shine as if they’re autobiographical while the male characters are often given less forgiveness and seen more as assholes (Richard and Benny) or simply behave more as if they’re zoning out for most of the day (Benny and Josh). Still, it’s not a reason to ignore the story, or something I’m worried this still-growing author is going to struggle with repeatedly in upcoming stories.

Back to Franzen: It’s more than fitting that the guy’s quote is used on the cover of her trade edition, and his words completely sum up the experience: “The Middlesteins had me from its very first pages, but it wasn’t until its final pages that I fully appreciated the range of Attenberg’s sympathy and the artistry of her storytelling.” Trust me on this: you’ll get to those final pages very fast. This novel’s as addicting, scary and compassionate as it comes.

September 4, 2013

One White Dude’s Privileged+Incomplete Take

How to Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America by Kiese Laymon

How to Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America by Kiese Laymon

These books are not remotely tied together in any way other than the fact that they’re both written by great men who happen to be black. And maybe it’s simply that I read the Laymon the day before I read the ?uestlove, but it was hard not to hear the two oddly communicating with each other, or both, anyway, addressing a topic as foreign to me as Cyrillic or moon phases. The topic each addressed was something about the experience of young black men choosing their selves.

That may sound dumb. Maybe it’s dumb for me, a 34 year old very white man, to even try to wrestle with or address what these two men are doing in their books. The experience of reading How to Slowly Kill Yourself and Mo Meta Blues was, for me, most strange in illuminating the lack of something in my experience: I have never had to choose who I am, not really. I choose what I do, and how I earn resources, and how I spend resources, but Who I Am? I happen to, because of the accident of my skin color, not have to choose who I am—or, better, whoever I choose to be (beared lumberjack looking guy, bespectacled nerd, tank-topped weirdo looking dude) is basically safe.

Did you see this video? You should watch this video. I found it useful.

To be clear: that’s LeVar Burton—Jordi, and the guy lots of folks in my generation learned to associate with reading—talking about how he acts *when* he’s pulled over by law enforcement (notice he doesn’t say if). I myself have been pulled over in my 18 years of driving a total of I think 4 times, and at no point did I get a ticket, and in each of those instances it was because a light wasn’t working, and in each of those situations I was treated what I’d call normally—without suspicion, without malice.

But that’s what’s weird, to me, about being white and consuming any aspects of black culture in America: my normal is larded with privelige. It just is. I don’t know if it’s a causal privelige, or one predicated on someone else having a shit time (I don’t know if, all the times I should’ve been pulled over, some police officer was instead pulling over someone with darker skin than I). I truly don’t know. What I know is that I’ve loved the Roots since 1999—since I first heard “Adrenaline!”—and I’ve been reading Kiese Laymon since someone passed along a link to an essay of his on Gawker at some point in the last year or so (here’s something of his, recent, which is just devastating).

Laymon’s is a book about race, about being a young black man from Jackson, MS and the worlds of experience he’s moved through (in Jackson, and then at Oberlin, and now in NYC, though there’s less about that last one than the earlier locales, and the bulk of the earlier’s located in Jackson). What Laymon writes so gorgeously (that’s not fair: the writing, yes, is gorgeous [Laymon's writing's never less than fantastic, as impassioned and conflicted as the best of Baldwin], but it’s also…it’s hugely thick and complicated; not one sentence in How to Slowly Kill Yourself [or his novel Long Division, which is equally great and a rocket of narrative power] pretends at clarity or ease: everything is multivalent, and all aspects of [Laymon's, and, presumably, more] black life in the US—every move, every breath—carries deep and troubling history) about is his own Black Experience (one’s tempted on reading him to simply say he’s writing about *the* Black Experience, given the power of his voice, but of course there isn’t One), and how conflicted and tough that Experience is (I don’t know why I keep capitalizing it; read the book and you’ll feel compelled to do the same).

And I’d like to here posit that one of the reasons Black Experience (all of it) is tough in the US is not just because we white folks can be fearful pricks. Reading Laymon’s book reminds the reader (this reader, anyway) of something profound and uncomfortable: the greatest luxury of White Experience in the US, particularly middle-class white experience, is that we get to believe certain lies (such lies largely begin with bootstraps and move from there). Laymon’s How to Slowly Kill Yourself doesn’t merely call out those white lies (there’s an essay in which he imagines asking questions to Romney and Obama, and that comes close), but instead he tries to—through ‘straightforward’ essays like a three-part consideration of Michael Jackson, Bernie Mac, and Tupac, or a devastating piece on his uncle, to more complicated/exploratory essays which are multi-voiced, are letters to himself and others, etc.—expose and explore the complex/conflicted experience of one person’s experience of how it is/feels to be black in America, and trying to navigate the world as people claim it to be, and then the world as it actually is. Again: go watch LeVar up there, talking about how he acts when he’s stopped by cops. He had to make that choice because of some heavy-as-shit rules about Black Experience. Laymon, in his penultimate essay, goes guns-blazing meta, and offers a second-person essay detailing his experiences in publishing and considers the notion of “Real Black Writer” (imagine Franzen ever talking about being a Real White Writer), and the tricks and traps of that endeavor.

This is already too long. Look, if we were wise, as a country, Laymon’s book would be required reading everywhere.

And then there’s ?uestlove’s Mo’ Meta Blues. Please know that there’s little of overt race-stuff in ?uestlove’s book: it is emphatically a book for music fans, and for some of us the thing’s just gonna be treasure (for instance, those of us who disagree with ?uestlove’s footnoter’s [Richard Nichols, "the group's comanager since day one"] claim that nobody really gives a shit about the song “Double Trouble,” [some of us, Mr. Nichols, have never had an mp3 player that doesn't have that song loaded onto it]). What Mo’ Meta Blues is, more than anything, is the smartest and most interesting music auto/biography I’ve read maybe ever, and certainly the most important one having to do with popular hip-hop/black music of the last two decades (which is a silly difference to even acknowledge, given that pop music is now entirely built upon hip hop [the same as R+R was built on the blues]).

The reader can’t help but note the emphasis ?uestlove (given name: Ahmir Thompson) puts on being aware of how he and the Roots are coming across: as anybody who’s read his liner notes know, the man’s keenly self-aware, and has (usually) a very very deep and abiding interest in presenting himself and his band just so. The most intereting part of Mo’ Meta Blues isn’t about the early days of the Roots, or about Thompson’s youth in his domineering father’s band (his mom was in the band too, but Thompson the elder ran things), but about the late-90′s and early 2000s music scene—that post-Biggie/Tupac/De La Soul moment of neo soul and Jay-Z and then the rise of southern rap (OutKast+co) and then Kanye—and what’s weird and fascinating in reading ?uestlove’s take on the whole thing is to discover how much he wanted to be The Band, how badly he wanted the Roots to hit it and become this Big Thing—wanted them to be chart-toppers (a la OutKast or Kanye, whoever).

Of course, the reason that’s so fascinating to me is because the Roots have always been, to my friends and I, the band, the hip-hop outfit we automatically got the new albums of (…my friends and I all of course being nerdy college white people, which brings up this whole other unfigure-out-able thing re: audience that’s better to just note and pass by). When this book was released, the line I saw quoted most was the one about how ?uestlove’s parents wanted him to be someone who could be on Jeopardy!, not someone who would be an answer on Jeopardy!. Fair enough, certainly, but one wants to sort of nodge Thompson and be like: that time you wanted to blow Jimmy Iovine’s mind and get him to pull the trigger and get all huge with The Tipping Point? That music lasts, and now you’re here, and Kanye’s clock is running, and Big Boi and Andre aren’t doing much, and and and…

It’s a damn great book. The thing about the layout, too: Richard Nichols footnotes his way through the thing, quarreling with ?uestlove page by page, which is damn fun, and there are, interspersed, notes from one Ben to another (one Ben is ?uestlove’s co-author, one’s the book’s editor), sort of filling in background about the book. It’s amazing. There’s a legitimate claim to be made that hip-hop folks do the best autobios (this and Jay Z’s alone would augur for such a claim). Certainly it would be a better world with more and more of these. Come on, Tariq/Black Thought: we’d all love to read it.

September 3, 2013

Duplex by Kathryn Davis

Trying to explain this novel is like trying to tell you about some weird dream I had: whether or not you were in it, no matter how crazy it was or poignant or whatever else attracts you to a good story, my retelling is gonna suck. While I hit on the plot, storyline (which, for Duplex, fits into about the same level of sense-making as most people’s dreams) and big key aspect, I ultimately have to leave out the colors and senses that made it so compelling, no matter how surreal it was. That said: this book is one you have to read for yourself, but here’s the best way I can relate it to you anyway.

It’s a different time. Maybe 1950, maybe 2050 or 2500, I’m not sure. It doesn’t matter. Fair warning: if details like that matter to you anyway, you’re going to struggle through this novel. A lot has changed: Robots are living next door, so close even, they share duplex walls with some of the most ordinary families in town. Not that it wasn’t a shock when the robots first moved in – after all, when out of the privacy of their own homes, they do don the guise of people. At first, people moved away or fought against robots living next door (think A Raisin in the Sun), but after so many came and it seemed every neighborhood had a robot or two, and as it turns out the robots weren’t that bad of neighbors (they’re Type A freaks when it comes to keeping human social standards, it turns out), people just got used to it, more or less.

Still, a lot of things haven’t changed. Most notably, girls. Girls continue dressing in saddle shoes and peter-pan collars, writing their own versions of novels about horses named “Lightning Bolt” or “Black Dancer,” they still fall in love with the boy next door in grade school and become high-school sweethearts, expecting love to last forever. But, in the case of main girl Mary and Eddie, whom everyone expects to be her starter husband, things get more complicated. Girls now have to chose between mere mortals and Sorcerers, or Bodies-without-Souls.

Yes, there are sorcerers and there are robots and they’re basically found on every page of the novel, but please don’t get turned off thinking this is some sci-fi shtick. It’s the most base, human book I’ve read this year. The beauty of it is Davis’ writing; without her way with words, this story couldn’t work. It’s the little tiny details she points out to you, like a girls’ mousy hair and unpolished shoes, that make you hungry to get to the next page. It’s the way she makes every character, most notable, Cindy the prom-queen, the only daughter in house number 37 and the first robot to attend the local school, into a complex girl who gets hurt when people ask about her appetite (she doesn’t have one) and whose husband (a human) catches her often crying herself to sleep because she’s so upset about not having a soul.

In fact, it’s easier to relate Davis’ novel (at least this one, since I unfortunately have not read her other novels – The Thin Place and Versailles are now on my short-list) to a story your grandmother told you long ago, or magical-realists in the tradition of Gabriel Garcia Marquez than sci-fi guys like H.G. Wells or Orson Scott Card. There’s still mention of fairies, magic hinting at the seams of every sentence – there’s simply robots and futuristic devices as well. I firmly believe if Marquez had grown up in the digital age and wrote a novel for his daughter, it would look a lot like Duplex.

Storytelling is passed on, even in the book. In a parallel time to Mary, Eddie and Cindy’s, (again, it could be 5 years later, 500 years later, maybe even 5 months prior – it doesn’t matter), hopeless storyteller and the closest thing to the novel’s narrator Janice passes on the stories of Mary, Cindy and other girls, their card games encounters and love affairs with robots and sorcerers, to the other girls in her neighborhood, starting with her peers, moving to the girls she watches as the neighborhood ages. Janice not only introduces stories and context to the world Davis has created, she guides the reader in what to ask for and expect. For instance, in reply to the girls pestering for names in the stories she’s telling, Janice says: “No names. Why do you always want to hear names? Does that bush have a name? Does that tree?… If I told you the names it would make your brains explode.” It’s the sense of only telling part of the story, only what we can handle. Davis’ novel has parts incomplete, parts we never quite understand even at the end or after a re-reading, but ultimately, we have the stories we need, the sights we need to see into this world she’d dreamt up. And it’s a beautiful sight.

August 29, 2013

THE AFFAIRS OF OTHERS by Amy Grace Loyd

The Affairs of Others by Amy Grace Loyd

The Affairs of Others by Amy Grace Loyd

In The Affairs of Others, Celia isn’t lonely. She doesn’t allow herself to be. Following her husband’s death (we never learn his exact age, but he didn’t live far past 30 at the most), Celia is a young widowed landlord shielding herself from more hurt by simply never getting her hopes up, barely caring about anyone too much. When a new tenant moves in upstairs, Celia’s life gets complicated as the walls she tries to keep begin to fade.

Really, it’s a great debut novel. Not that author Amy Grace Loyd is by any means a newbie to the literature world – she’s previously worked for The New Yorker’s fiction department as well as serving as the fiction and literary editor at Playboy magazine. What this means: Loyd knows the difference between a good and a bad sex scene. And she writes the good ones, not the 50-shades-porn, not the anatomically-correct-scientific-description, but the scenes that buzz with narratives on the lines of a woman’s skin and the soft details of touch.

Here’s the catch with all that: 8/10 times sex happens in the book, Celia’s not involved. It’s between that new upstairs tenant Hope, recent divorcee mother of two, and some guy, beefy and stoned. Celia’s not being voyeuristic listening to the two’s games – she literally can’t block the noise out. Yet, Celia’s had too many invitations to peek into Hope’s life as a mother and as a fellow-lost soul looking for some type of completion to kick her out so easily.

Oh, and while this is all going on, Celia lost an old man. At least according to his daughter, who blames Celia when her father’s been AWOL for a week, not knowing the way Celia would restock his cupboards, make sure he eats and give him breaks on his rent costs, not minding if he missed a month here or there.

It’s awkward, it’s uncomfortable and all in the best kind of way. Inside the head of Celia, I felt on the verge of crying for basically the entire novel FOR HER, because the girl’s not allowing herself tears or self-pity. That brings to mind another highlight aspect of the novel: freakin’ Celia’s character is so well written, I’m sure she’s still renting out a place in Brooklyn today and if you look hard enough, you’ll really find her.

The only short-coming of the novel is the ending. It seems rushed, like Loyd said to herself “there’s so much shit happening, things are so messy, how can I tie this up neatly?” Some issues sort themselves out too easily, some get pushed to the background, others get “resolved,” if not in any satisfying way.

Overall, though, this is an amazing debut novel. I can’t wait to see what Loyd is going to write next. Cheap ending and all – read this book. It’s well worth your time.

August 26, 2013

Claire Vaye Watkin’s BATTLEBORN Stories

BATTLEBORN Stories by Claire Vaye Watkins

BATTLEBORN Stories by Claire Vaye Watkins

Just a preface before you start the first page: These stories ARE fiction. Or at least so says that paragraph on the credits page, “This is a work of fiction. Names, characters…” so on. But then I finished the first story, a piece about Claire, the daughter of former Charles Manson’s right-hand man Paul Watkins, and I started looking everything up online. So yes, when you get to that point when you’re questioning whether or not this author who didn’t mention it in her back-cover bio and whose name you haven’t heard of before was actually born in the Manson family, the answer is yes, get it out of your system now, yes she was (if you don’t believe, that’s fine, I doubted as well, but here’s a little proof: http://www.theguardian.com/world/2012/aug/10/manson-family-member-my-dad ). Does that mean the “Claire” in the story is the real author? Does that mean her short story is true? It’s likely she’s the only one who knows for sure, but really, it doesn’t matter.

One thing I do know for sure about Claire: this girl can write some sad stuff. Stories are filled with men lost in the Nevada desert, both figuratively and literally; Women scared they won’t ever love their baby or even that they’ll love it too much and it will be impossible to get rid of; Girls who have no one, or have someone until they lose them by their own selfish actions; Women stuck in loveless, lifeless marriages with “the right guy.” Really, I’m trying to think if any of her stories could be considered *happy* or at least having a redeeming ending and I’m coming up blank.

Second topic Watkins gets and gets well? Western terrain. From desert lands to glowing Las-Vegas lights and every brothel and one-man shack in between, Watkins is a master at capturing and recreating space. Don’t fret if this sounds boring to you: I couldn’t care less about cowboys, sand dunes, or basically any place that has less than 1,000 people/square mile, yet Watkins makes the land itself a character in the story and makes it something you actually care about (even if once you put the book down, you go back to ambivalence). Seriously, if Willa Cather had written about land this well, teachers would make O Pioneers! required reading. Throwing in probably my favorite line from any of the stories here: Subtext – This guy’s brought his little daughter with him to check out this abandoned, burnt-up ghost town, takes his eyes off her for a minute, loses her, panics, then finds her playing away behind the rotting schoolhouse. He hugs her, then slaps her across the face, and when she cries, only says to her: “Shh. That’s enough. A child means nothing out here.” Seriously, this girl can make Las Vegas feel as lonely as an empty home.

So why read such depressing stuff? Thing is, Watkins writes about all this muck and grime and mess of life so well. She understands the subtleties of love and loss and what can make each just so painful, and she captures it all on the page beautifully. In sweeping narrative, in picking just the right adjective or knowing when the basic nouns (boot, chair, can, tin) will do, Watkins work is incredible. And for those redemption seekers, those looking for a glimmer of hope in the dark, dark world Watkins has created, there’s also that moment before the loss when you see just what these people have. You see them loving, you see them holding on to babies that were never supposed to be born, cherishing memories or simply helping one another out. But, for those of you who want the story to end there, to not get to the messy stuff where it ends up broken and bleeding, you’d be wiser reading something else.

August 16, 2013

“That’s Not Funny, That’s Sick” wasn’t that much of either, oddly.

That’s Not Funny, That’s Sick by Ellin Stein

I don’t know if it’s ever a good idea to name a non-fiction book after an album. Think about it: have you ever read a history on The Beatles’ “Abbey Road” that didn’t make you want to throw down the book, put on the album and just chill? That’s Not Funny, That’s Sick (in case you’re wondering, named after the fifth comedy album produced by the National Lampoon Crew) definitely falls into that trap – the book doesn’t completely satisfy.

Stein starts way back before it was technically National Lampoon, when it was just called Harvard Lampoon and didn’t circulate too far from school. She hits on highlights throughout the mag’s growing years, from Radio Hours (basically comedy tapes), to movies such as Animal House (which, even if you’ve seen, may not have realized was connected to a Lampoon-styled Yearbook spoof) as well as the way the magazine made shows such as Saturday Night Live a possibility.

One problem here: I wish Stein would have specified more about the time she’s going after with the book. She basically quits the story after editor of the National mag Doug Kenney’s death in the early ‘80s, saying essentially, this was when the magazine was Finished. Except, it kept printing until 1998 and still has movies coming out under the heading “National Lampoon’s Such-and-Such” TODAY, as in August 2013. Seriously: did you know “National Lampoon Presents: Beach Party,” starring Matthew Lillard, has just completed production and is being released soon? NEITHER DID ANYONE EVER.

Also, Stein throws in a lot of stuff that has small connection to the Lampoon at all. There’s a chapter dedicated, and more surrounding those pages, just about Saturday Night Live (including John Belushi’s true feelings about the first season’s feature of Muppets and Bee costumes, for those four guys out there who were wondering), yet the connection between the mag and the show seems like they shared some actors/ senses of humor. Maybe there was more of a connection, but it wasn’t super clear.

As a ‘90s kid, I’ve never seen a single issue of the National Lampoon magazine. Really, the only context I had of ‘National Lampoon’ before reading this book was watching the Christmas Vacation movie like, twice and a vague memory of the connection to Ryan Reynold’s Van Wilder character. That said, some of the references didn’t quite click with me. Stein goes in-depth about jokes coming out of certain sections of the mag, yet fails to make those sections clear enough to someone who has never seen the thing in print. Same goes for long biographical details about the editors/contributors. While I was right there when she talked about Chevy Chase, Lorne Michaels, etc., I had no footing as she talked about this Doug Kenney guy who was a big part of the mag (and her book).

Either way, a lot of the jokes still stuck, even without the best of context. Stein picked out issues and jokes to retell as examples of humor, which really is the best part of the book. My dark favorite: her excerpt from something horrible called the Vietnamese Baby Book which was released during the conflicts which featured a section on “Baby’s Progress” (“Four weeks old: able to whimper; Six months old: first nightmares; Two years old: knows bombing raids without being warned”).

I’d have to say this is a book best left for the already fans of the National Lampoon – it’s definitely not an intro-course. There’s probably a lot of really cool, little-known facts in here that went way over my head that true fans would find fascinating. But for me, it only made me crave to see and read the original, not Stein’s anthology of it.

August 13, 2013

Thrilling as in Thrillers

Visitation Street by Ivy Pochoda

Visitation Street by Ivy Pochoda

I have a sort of schizy relationship to thrillers: I’ve yet to read one that I don’t just love, and, by and large, the ones I find are so hugely, awesomely good I feel stupid for all the literary fiction I read. Not that lit fiction’s inherently bad, but when it fails, it’s a waste; when thrillers/crime/pulpy stuff fails, at least yr heart is, usually, thudding along at a slightly higher rev than usual, and at least you’re flipping pages quick as you can. Anyway: I should read more. I say this plenty. Let’s just acknowledge it and move on.

The two crime/thriller books under consideration presently represent, I think, sort of far poles: Full Ratchet is a break-neck-paced page-turner with fast cars, hot sex, explodey things, mysteries, etc. etc. etc. It’s that sort of book, but please don’t think I mean any judgement: one needs that sort of book, I’d argue, a hell of a lot more than one needs the sort of book in which the too-self-aware twenty-something takes 240 pages to come to a conclusion that was clear as crystal as of page 12 (all he had to do was be honest with himself!). Ahem.

There’s more than a little Michael Clayton in Full Ratchet: our first-person narrator’s Silas Cade, a hit-man (he was introduced in Clawback, which is just as good as Full Ratchet, though this latest one’s not a sequel in the sense you’ve got to know Clawback to get it). Maybe better to call him a problem-solver: Silas will kill people if that’s the job, certainly, but his specific line of work is to get to the bottom of business practices that don’t square: Full Ratchet begins with him investigating a company in Pittsburgh with accounting irregularities, which irregularities will, eventually, be part of a larger, broader scheme, one which will, in the breathless words of newspapermen, go all the way to the top of the organization.

Weirdly, greatly: you can tell that, almost from the start. A book like Full Ratchet lives and dies, it seems to me, based on how it satisfies the expectations it gives you, and if this book did not have a big, menacing, isn’t-what-he-seems bad-guy at the top of things, you’d be (I’d've been) disappointed. This is me trying to say that it is, in the best ways, modestly formulaic, but also that the formula is great and worth it and big, big fun.

I don’t know what else you need. The thing’s a blistering popcorn thriller. I read it in a night with gusto and great pleasure, and I’d bet good money you’ll take to it similarly.

Not so Visitation Street, the debut on Denis Lehane’s imprint through Ecco books: it’s a great book, and I loved the thing, but Visitation seeps creepily along, the mystery at its center blossoming slow as a ragged, raw rose. The basics of the story are simple enough: a pair of young girls in Red Hook, Brooklyn, go out for a ride in a raft at night one night, and, in the morning, one of the girls is found washed up on shore, but the other one goes missing. It’s a humble, simple premise, and Ivy Pochoda absolutely blasts the ball out of the park on this because 1) she makes Red Hook come to scuzzy, trying-its-best life, and 2) she’s built a cast of hurt, wounded, hounded, luckless characters, each of whom demand some modicum of sympathy. For the record, too: Pochoda writes such fucking perfect sentences your head will spin. Best example from early on: “She has a toxic red dye job and faded tattoos that look like bruises. Her gray eyes tighten as the night drags on. By last call they look like the heads of two screws.” If that’s not bow-down writing, I don’t know what you’re looking for.

Tempting as it is to get into these characters, you’re honestly better served by simply purchasing the book (do it) and just discovering them. There’s Lil, a bartender, and Fadi, a bodega proprietor, and Cree, a young man with a dead father haunting him, and Val, the girl who washed up and who, now, lives with the ghost of June, the disappeared girl, chasing her as well. The book’s a stunner: I’m writing too little about it, and don’t even know what to say other than read it read it read it. Pochoda’s great novel’s right in line with the best of Richard Price and Lehane himself: work which centers around some dark event but which, by circling it—by including all the tiny aspects of city life that make these dark aspects transpire as they do—makes the label crime novel or thriller or anything else almost stupid, comically small. Visitation Street is a whole world. Get to it.

August 10, 2013

Deeply Enmurking

The History of Luminous Motion by Scott Bradfield

The History of Luminous Motion by Scott Bradfield

Nights I Dreamed of Hubert Humphrey by Daniel Mueller

Both of these books might be considered grotesque, dark, disturbing, weird, whatever. Both work on sort of Lynchian levels of nightmare-dark aspects stuffed into the middle of otherwise banal daily life. Both books are excellent, yet I want to be clear: I am by temperament a softie, and I like nice things, happy things: I grew up on the Beach Boys, and much as I love Wallace his darkest stuff makes me anxious and sad and mildly scared, and one of the big reasons I so love Richard Powers is because his stuff’s almost always so ultimately uplifting, so let’s-keep-going. There are plenty more examples, but I want to bring all of that stuff up simply to say that in the two days I read both of these books, reading 50 pages of one, then 50 pages of another, I felt…gross. Dark. I found myself in a weird, flummoxed mood. I haven’t smoked in years now, but both of these books made me feel like I’d been smoking for days.

Maybe History first: re-issued by the everfantastic Calamari Press, Scott Bradfield’s debut novel was released in 1989 and the two reviews easiest to find online, from the LA Times and the NYTimes, are interestingly divided on the book—read both. They’re good fun. Also, read both for the basic plot stuff in the book—which is interesting enough but is not, ultimately, what History feels *about* in any real way, at least to this reader.

Phillip, History’s central character and narrator, is, sure, maybe a stretch for an 8 year-old—too articulate, whatever. But the thing about the book that made it so compelling to me, and why it was something powerful enough to interrupt and fuck with my emotional life over the days I read it, is that, like the best books, it strips away the cultural experiences which we ultimately use as condiments on our own lives. There’s some infinitely large number of books which try to (or are hyped because they) examine and lay bare the harrowing nature of childhood or some such. You’ve read examples of such books, no doubt.

But Bradfield’s History makes the experience of childhood—which includes the experience of literally bulilding a model or context by and through which to understand the world—as terrifying as it really is. Is Phillip a troubled, troubling kid—moreso than you or most folks you know/knew? Certainly. But the specifics of his experience don’t change the fact that the book’s examination of light/energy vs. matter/mass is, for all of us, something we’ve got to work through, in some way or another. Maybe you don’t think about this stuff. Maybe you shouldn’t. But Phillip does: his mom’s all light and energy, his dad’s all mass and inertia, and he’s trying to literally figure out the world between those two polarities directly, overtly—like, guy’s literally trying to understand how to slot the experience of each, how to value and evaluate each.

Maybe that’s why, ultimately, the book’s so devastating. The books/music/movies that end up destabilizing me, in good and bad ways, are those which ask/invite me to consider that the things I’ve worked through to a satisfiable level of certainty may in fact be wrong: maybe I’m wrong in how I have constructed a framework to understand reality. Even if History doesn’t change such notions, it forces you to contend again with those forces, forces you to recall the hugely significant stuff that helped you build your own awareness of How Life Works. Let me put it this way: it’s not remotely coincidental that religions rely on patterns for prayer: there’s mass, or synagogue, or whatever. There are these things, these agreed-upon, structured acts through which we operate our faith. I’d argue that the big reason for such structural stuff’s that contending with the infinite, with the deepest issues of spirituality, is destabilizing, and if we had to do it anew, each week, we’d barely be up for the task. Most of the big things are like this—love, death, etc. Childhood’s a darker realm, murkier, harder. Bradfield’s mapping it here. It’s a hard read—hard in what it asks the reader to deal with and do—but compelling as hell. You probably should be trying it.

Mueller’s Nights I Dreamed of Hubert Humphrey (by the badass Outpost19) is not quite as dark or bracing or demanding as Bradfield’s History (thankfully: one can only read so many rethink-everything books before just flipping on House Hunters), but it’s sneaky in ways History is not. This sneakiness manifests as follows: most of the stories in Nights are, roughly enough, about people (largely boys and men) trying to find their place in the world, trying to find where they fit. One may fairly/safely expect, therefore, for the stories to be animated by notions of desire, but a trick of desire is that articulating desire depends to a degree on awareness, specifically self-awareness. Mueller’s characters are folks of various clenchings, seemingly unable to be clear regarding what’s in them, at any depth. The murk of the thing’s tidal, or at least it was to me.

And yet such confusion is generative, in dark ways. There’s got to be a better word for what these characters are—they’re not really confused, nor are they ignorant; it’s more overwhelming: it’s that they’ve got things in them they won’t or can’t look at, and those things they won’t/can’t look at are [of course] massively important aspects regarding how crucial decisions are made. Think of it like this: if you’re somehow confronted by two very angry people, one of whom loves Lik-M-Aid and Coke Zero, the other of whom seems to have no clear weather pattern regarding desires, most of us would choose to be confronted by the angry person who also has some clarity regarding desires and wants. That’s life. But in these stories, such lack of clarity’s hugely generative: we read to the end of each of these stories, basically discovering if life is satisfying to these characters while they’re processing the same. It’s a heady way to read—again, it murked me, and left me feeling deeply weird—but there’s zero argument against the power of these stories.

August 7, 2013

Just Cover Ground

There are quite a few amazing books coming right around now, so I’m gonna try to just blast quickly through some significant worthwhile ones, but please know all of these are worth every bit of your reading time, even if the reviews are brief-ish.

The Infatuations by Javier Marias

The Infatuations by Javier Marias

I’ve been a Marias sucker since ’05, when I read A Heart So White, though I was (like most) bowled over in the last five or so years by his massive (in all senses) Your Face Tomorrow trilogy, out from New Directions. I don’t even know what to say about The Infatuations. Most certainly: this is his best, most amazing novel. Also: Marias’s style—the hugely long sentences which tributary off again and again; the long theoretical considerations by one character about another’s interior; the language that is so weirdly basic, so everyday-ish and almost simple—is always this weird spell cast on the reader, or at least it is on me: I begin any of his books and am sort of amazed to realize I’ve only covered forty pages, but, very unlike with other books, I find I can’t really skip or pull away from the long digressing passages. This is a clumsy way of saying that Marais is a magician, in that he can create tension out of what would, in the hands of most writers, be merely a matter of excess verbiage.

And that tension he creates (he does it in all his novels; I don’t know why I’m surprised by it anymore) is so perfect for The Infatuations it’s hard for me not to just jump up and down about it, shouting. Look, Marias has been going long enough now to have earned the adjectivization of his name, and what I’d like most to say about The Infatuations is the least descriptive: it’s terribly, terribly Marias-ian: Maria frequents a cafe which is also frequented by a couple, and what is the word for that relationship—those people you see regularly without ever forming some relationship? The husband of that couple, Deverne, is murdered. The dead husband’s best friend, Diaz-Varela, comforts Luisa, the widow. Maria begins an affair with the best friend. Those details would be enough to fuel plenty of novels, but Marais adds a shift: the best friend may or may not have been involved with the murder of the husband.

To say more is sort of silly: the point of the story is not in grasping after some aspect of who-did-what-and-when-with-what. The point, rather, is bigger and darker, and is about selves, about who we truly are, deep within. Even writing that seems schmaltzy and dumb, but I’m telling you, it’s there. I can think of no other piece of fiction I’ll read this year that’ll offer pleasures like those found here, and the reason, by the by, that Marais is always rumored to be on the short list for a Nobel is because of work like this. So, so, so damn good.

I stupidly did not read Once the Shore, Yoon’s debut collection of stories from four years back, and was thrilled for Snow Hunters for the hope of rectifying a mistake. The advance hype on this book seemed to focus on the fact that the manuscript was originally much, much longer—more than double the final book’s length—and Yoon’s cleaving and paring were the big sell.

Such praise is merited, certainly: Snow Hunters, a story of Yohan, a Korean prisoner of war who emigrates to Brazil, is almost fable-like at the sentence level. Maybe fable’s the wrong word: maybe it’s more dream-like. The sentences—spare, stripped down to austerity—are propulsive. They also, by dint of their sort of passive tone, make the whole book feel just achingly lonely: Yohan’s story (the novel covers a decade) is monastically solo. True, he works for/with Kiyoshi mending clothes, but he lives fundamentally apart.

The novel’s ultimately something like an emotional snapshot, though one in which emotion’s almost completely absent: Yoon’s power has everything to do with how physically-grounded and -detailed his sentences are, and how that detail lends itself to yawning solitude, quietness, etc. I kept thinking of Barrico’s Silk on reading this—another book which seems more invested in how it will make the reader feel than, say, how the reader thinks or sees things. The feeling here is large, a sort of cathedral of emptiness that Yoon, at book’s close, hints will be filled in, and which hints are enough.

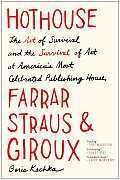

Oh good lord did I gobble the hell out of this one. The book’s a portrait of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, the publishing company. Your response to that previous sentence probably tells you as much about how you’ll feel about this book as anything. If you read books without ever (or much) checking the colophon at spine’s base, this book may be only glancingly interesting. If you know books well and know FSG because that’s where like half of all the great literary fiction and nonfiction and poetry have been published for the last 50 years, this book is necessary.

There is of course a third category of potential fans of this book, and that is: people who just generally give a shit about 20th C (mostly American) literature. FSG’s background is probably no more or less riveting than lots of other presses—I’d have a hard time believing the stories of, say, McSweeney’s, or Graywolf (which is in fact distributed by FSG), or Wave aren’t just as interesting or gratifying to read about. What makes FSG unique, however, the scope of their successes, and what those successes have meant. If you partake of what’s considered high-brow cultural life, you basically have to contend with FSG and its authors (given, for instance, how many New Yorker authors they’ve got). And that, ultimately, is where Hothouse is most valuable: it ends up being a snapshot of or lens through which to view American literary/cultural life in the last 50 years, from New Journalism to big publishing consolidations to certain foci on certain work in translation, etc. I just devoured this thing. I can’t see how anyone wouldn’t.

Crapalachia by Scott McClanahan

Oh dear shit just read this. Just read it. Buy six copies and read the shit out of it. I finished this book only yesterday (though it’s been out much longer, was released by the 100%-badass-still-haven’t-missed Two Dollar Radio), and I’m fairly certain I’m too close to the experience of having read it to be able to say much. What I can say is that it’s a *memoir*, but the thing’s subtitled A Biography of Place, and that place is West Virginia (a state I’ve only got a going-through relationship to, having driven it plenty in the years ’06-’09), and what the book is is McClanahan’s big barrel-chested grab at wrestling his life into some Thing he can point at and say that’s it, a way to turn his experience into lessons or ideas. Which, sure, is the job of any memoir, but McClanahan’s actively trying—he interrupts the narrative early on [the first 50 pages are fucking perfect genius: the first chapter's actually like 13 pages in, and two chapters back to back both try/fail to make clear what Ruby, McClanahan's grandmother, was like] to, on page 26, say “The theme of this book is a sound. It goes like this: Tick, tick, tick, tick, tick, tick, tick. It’s the sound you’re hearing now, and it’s one of the saddest sounds in the world.” The point of the interruption—the point of the whole fucking book—is that the living is beautiful and crazy and everyone will die and that’s it. That’s really it. It’s as simple and obvious as that—and yet, jumping into McClanahan’s speeding vehicle of a book [the thing just thrums: you'll tear through it; I had to stop myself, and only finished it yesterday because I'd put it off already for two days], you feel like such a basic, obvious observation’s a revelation—which, I’ll submit, better be the whole point of reading and connecting with people. Make it a revelation. This book stuns. Good lord.

Hothouse by Boris Kachka

Hothouse by Boris Kachka