Weston Cutter's Blog, page 15

January 28, 2014

The Careless People of the 1920s

CARELESS PEOPLE: MURDER, MAYHEM AND THE INVENTION OF THE GREAT GATSBY by Sarah Churchwell

CARELESS PEOPLE: MURDER, MAYHEM AND THE INVENTION OF THE GREAT GATSBY by Sarah Churchwell

I don’t think I have a whole lot in common with Owen Wilson, but after watching Woody Allen’s “Midnight in Paris,” I felt like Owen and I could be soul mates. I know his character was a creation of Woody Allen’s mind (I didn’t want to start an article saying “I don’t think I have a whole lot in common with Woody Allen, BUT!”, for what are probably obvious reasons), yet I’m like, “Owen (because no matter how many times I watch the film, I still can’t remember his character’s name), I will travel and live in the 1920s with you forever! I want to wear flapper dresses, tape my boobs and smoke foot-long cigarettes with one hand and hold a gold purse in the other! I want to be best friends with Hemmingway and help keep Zelda Fitzgerald from floating away from this world! I want to party and sip drinks like prohibition was a figment of the imagination!”

There’s this undeniable allure to the 1920’s, at least in my mind. From 2014, it seems like a swirly good time, an era when girls could be the revolutionary forerunners of women’s rights movements and wear the BEST dresses at the same time, where everyone making the news was wealthy and the biggest problems centered around finding the best bootlegger for your next party.

It’s a great mixture of all this (plus, some appeal for the men that doesn’t have to do with dresses that I’m not grasping) that makes The Great Gatsby so amazing, yet underappreciated in its own time. The novel itself is a perfect snapshot into the glamorous life of the 20s, plus one of literature’s best stories of jealousy and the harm it may bring. These too, as well as the other peculiarities of The Great Gatsby, the lives of Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, and the biggest crimes of the time, are the base elements in Sarah Churchwell ‘s newest book, Careless People: Murder, Mayhem and the Invention of the Great Gatsby.

Starting with the move of the Fitzgerald’s from the Twin City area to big-city Manhattan, Churchwell tracks the lives of Scott and Zelda carefully throughout the fall of 1922. The Great Gatsby itself being set in that tumultuous year, Churchwell also tracks the lives of Nick, Daisy, Tom and Jay as if they lived lives independent of the page, looking back on the events, the styles and the scandals, that come into play throughout the novel. For instance -the long white dress Daisy and Jordan are wearing when the reader meets them for the first time? Not just symbolic – long white gowns were the thing that season.

Of course, for folks with a mild 20s obsession like myself, the research is fascinating. For those less interested in the culture, don’t worry – Careless People offers plenty more. In-depth analysis of The Great Gatsby? They should hand this book out in high schools to make sure the kids are actually getting Fitzgerald’s words. A murder-mystery case as delicious as that of who killed Myrtle Wilson? Churchwell spends a good portion of the book telling the tale, helping us uncover the details of the famous 1922 double murder (and suspiciously botched investigation) of Eleanor Mills and Edward Hall, an event that most likely appeared in newspapers lying around Gatsby’s study. A closer look into the lives and the love between Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald? You’ll get to learn so much – like, down to how much Scott spends on parties and the affairs Zelda fell into a few years later in their marriage. Seriously, not a second is wasted in this 350 or so page-turner.

Careless People was fascinating. I got so wrapped up in the world Churchwell’s opened a window into, I almost tore out the list of words first recorded between 1918 and 1923 she complied and included in the book so I could carry it around with me and remember to use them all at my next formal party (slinky! Ritzy! Posh!). Without a doubt, it did nothing to discourage my desire to wander throughout the streets of Paris until a cab takes me back in time, a la a Woody Allen film. It’s utterly smashing.

January 24, 2014

The Artful Arrangement

(Today’s post is another guest spot from Tasha Cotter, whose first full-length collection of poetry, Some Churches, was published in 2013 by Gold Wake Press. You can find her online at www.tashacotter.com)

First published in 1976, Renata Adler’s Speedboat most closely resembles a novel-in-fragments. Narrated by journalist Jen Fain, Speedboat is rich in flashes of wit and wisdom while reporting on a life lived primarily in New York City. I found myself highlighting lines and noting her more aphoristic moments—there were many worth lingering over. The book, always episodic, frequently presents the reader with memorable lines such as, “I think when you are truly stuck, when you have stood still in the same spot for too long, you throw a grenade in exactly the same spot you were standing in, and jump, and pray.” I found myself pausing over such passages time and again. The book is not only captivating in its reporting of everything from the seemingly mundane to national politics and her experience negotiating the politics of higher education (our narrator Jen Fain can’t ever ask a straight question); it manages to illuminate the questions and oddities of contemporary life.

First published in 1976, Renata Adler’s Speedboat most closely resembles a novel-in-fragments. Narrated by journalist Jen Fain, Speedboat is rich in flashes of wit and wisdom while reporting on a life lived primarily in New York City. I found myself highlighting lines and noting her more aphoristic moments—there were many worth lingering over. The book, always episodic, frequently presents the reader with memorable lines such as, “I think when you are truly stuck, when you have stood still in the same spot for too long, you throw a grenade in exactly the same spot you were standing in, and jump, and pray.” I found myself pausing over such passages time and again. The book is not only captivating in its reporting of everything from the seemingly mundane to national politics and her experience negotiating the politics of higher education (our narrator Jen Fain can’t ever ask a straight question); it manages to illuminate the questions and oddities of contemporary life.

There’s a sense of inventiveness about Speedboat. Over the years it’s been categorized as experimental fiction, which I think detracts from the book’s accomplishments. Adler isn’t interested in following any supposed rules of how a novel should look.

There’s a poetic quality about Adler’s clear gift for compression and attention to detail. You sense she misses nothing. While reading Speedboat I was alternately reminded of the fast-paced, vignette-like quality found in some of the work by Sandra Cisneros and the narrative-qualities of the poetry by Sarah Manguso. To read Speedboat is to learn about a cast of characters (mostly in New York City) from another era. The book is rich in anecdotes and images that force us to slow down and pay attention. For example, this passage on page 62:

The weather last Friday was terrible. The flight to Martha’s Vineyard was “decisional.”

“What does ‘decisional’ mean?” a small boy asked. “It means we might have to land in Hyannis,” his mother said. It is hard to understand how anyone learns anything.

Speedboat is a fast-paced tour through the mid-twentieth century. It’s easy to fall in love with this book, as it offers so much to its reader—honesty, self-awareness, and observations that feel true and applicable to your own life. Though not afraid to make large statements, Adler is also adept at weaving in the tiny, easy-to-miss moments of life. Take this example from page 89, “When our car broke down near the highway exit to the farm, a boy with a sign reading BOSTON trotted over. He thought we were slowing to give him a lift.”

The simplest moments in life are magnified in Speedboat and in context of the entire narrative, they work to superb effect. The personal becomes familiar and relatable allowing us to see our own lives and the lives of others as something like an artful arrangement.

Adler doesn’t just report on what she’s seen and heard, she deciphers it and then places it in the context of a larger narrative. Adler incorporates a variety literary tools to create a unified book. Whether it’s the queen arriving on an island the narrator happens to be on, or a memorable scene at one of Edith Piaf’s last concerts in Paris, or anecdotal information about a President, the book is electrically charged by her candor, insight, and movement through the world. In his Afterword for Speedboat, Guy Trebay observes, “Adler conjured a novel whose angular brilliance is how deftly it sampled the sounds and rhythms of contemporary life.” Comparing Adler’s work to a musical compilation works well. The book operates a lot like a soundtrack—full of different moods, images, and themes. The book is unconventional in how satisfying and yet seemingly original it is. Undoubtedly, it’s a book that’s every bit as relevant as it was when it was originally published.

January 21, 2014

Yu Hua’s Boy in the Twilight

Boy in the Twilight: Stories of the Hidden China by Yu Hua

Boy in the Twilight: Stories of the Hidden China by Yu Hua

As a little girl, I grew up on fables such as “The Tortoise and the Hare,” “The Ant and the Grasshopper,” “The Dog and His Reflection,” and most notably, since I was a terrific liar, “The Boy Who Cried Wolf.” At that age, though, I didn’t quite get irony or really, the lessons of these tales, so when grownups would ask if I understood the story, I always answered very easily: Yeah. Just don’t go screaming about wolves all the time or the other people in town won’t like you and wouldn’t help you out. Then a day later, I’d make up some truly unbelievable story, the grownups would ask “don’t you remember what happened to the boy who cried wolf?,” and I’d be like, yeah of course I do, but what does that have to do with a crow flying in the house and knocking over the lamp?

In a way, Chinese author Yu Hua’s latest collection of stories, Boy in the Twilight, has a feel similar to a collection of Aesop’s fables. Hua’s stories are full of irony, and although way too violent and full of adulterers for any wise parent to read to impressionable children, these tales give the impression that there is something to be learned at hand.

Take the title story, “Boy in the Twilight,” for instance. It starts off simple: A merchant catches a young boy stealing a single apple from his fruit stand, makes the boy spit it out and to teach him to never steal again, forces the child to shout out to every passerby that he is a thief. But the story doesn’t end with the young boy’s contrition or evidence that he has learned his lesson – instead, it ends with a look into the merchant’s life at home, empty and alone after losing his son to the river and his wife to another man.

Or, take the story “Appendix.” A doctor tells his young sons about a British surgeon that when stranded on his own, performs his own appendectomy in order to survive and brags about how their old man would be able to perform such a feat as well, only to eat his own words later when his own appendix bursts and the sons bring him a mirror and tools to do the job himself rather than getting another doctor at this crucial moment.

There are eleven more of these tales in Boy in the Twilight, including a story about an awkward young businessman using his new standings to woo two women at once (undoubtedly making up for lost time), matching tales of a cheating wife and a cheating husband who are both found out and bested by their faithful spouses, and the story of an ungrateful son sipping away on his parent’s hard-earned wages.

Being a Chinese author (actually the first one ever to win the James Joyce Award in 2002), Hua’s stories often stand apart with a touch of cultural differences from the typical American short story. For many of the stories, it’s difficult to tell if Hua is writing about the China he experienced growing up during the Cultural Revolution of the 1960’s, the China he knows today, or some nation caught in between the two places. Stories drift between small, dirt road laden villages to crowded apartment complexes set next to factories. Many stories reflect the realities of a nation undergoing rapid changes, such as the story of the young businessman in “Sweltering Summer,” newly rich, and dating two girls who are both slaves to the latest trends in fashion, devotees of English magazines devoid of a single Chinese character.

Life seems somehow less precious, more of a temporary commodity, in Hua’s stories. Characters see themselves less as protagonists bound for great things than simple men and women carrying on as best as they know how. Violence, even between friends exchanging bruises, is a muted tragedy. Animals, even dogs, aren’t precious.

There’s much to be taken away from Hua’s work, whether his stories truly have a moral or some sort of lesson in them or not. Perhaps what he is offering is nothing less than insight into the extremes of warmth, tragedy, pleasure and pain found in his version of the nation. Perhaps the takeaway is nothing more than 13 tales of irony, of characters’ highest and lowest points and how they carry on afterwards. If so, Boy in the Twilight is still a remarkable, wisening read.

January 16, 2014

The “Flyover Lives” of Middle-American Heroines

FLYOVER LIVES by Diane Johnson

FLYOVER LIVES by Diane Johnson

I have this idea that every child raised in New York City must be infinitely cooler than the other children in America. They must be exposed to so much! They must be so street-smart and savvy! They must be so aware of other ethnicities! They must value art and fine entertainment! The advantages they must hold!

Yet, these kids have one disadvantage: with the natural desire to flee one’s hometown for a bigger and brighter place, these kids have nowhere else in the states to go. They don’t get the advantage of being the cool person that graduated high school and never came back to their hometown, because if they leave that town, every else is smaller, like a downgrade.

The point I’m trying to make here: the place where you were born doesn’t make an ounce of difference on how cool of an adult you’ll be. You could be born in po-dunk Missouri and hate it so much that you spend every second working and plotting your way out of there and that work lands you in Harvard, which lands you somewhere else pretty cool; or, you could be born one of those cool NYC kids, find out about pot at a super early age and become a burnout 27-year-old living in your mom’s spare room. These are really cliché examples, but my point is: the city in which your mom decides to rid you from her womb bears no effect on your future coolness.

That said, and to get to the point of Diane Johnson’s first memoir, Flyover Lives: since it doesn’t define you, embrace it. Embrace the quirky little eccentricities of your hometown and the effect it had on your childhood/values as an adult. Look into your history and figure out why it’s the place your parents, or grandparents or earlier decided to move or stay planted there. Then, take another look at your family, and what it means to come from them.

Diane Johnson’s one of the best examples that you as an adult will have nothing to do with your hometown. Born in Moline, Illinois, a town that’s a suburb of Iowa far more than a suburb of Chicago, Johnson grew up, left the state, eventually settling in San Francisco and Paris, the cities which she now splits her time between. Along the way, she has written three popular novels about American women living in France (Le Divorce, which became a chick-flick starring Kate Hudson and Naomi Watts, Le Mariage, and L’Affaire), another novel about a woman dealing with cultural shifts (Lulu in Marrakech), been nominated for a couple of Pulitzer Prizes, National Book Awards, and, in my mind the coolest achievement ever, she co-authored the screenplay for Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining, aka the best horror movie, like, ever. So, she’s grown up to do cool things, you could say.

This whole memoir seems to be spun off one of those backhanded insults Johnson was offered by a French General’s wife who claimed Americans neither knew much about their own history, nor seemed to care. Years later, Johnson has examined as far back into her family’s history as she can, which is, impressively, the 18th century. She details the lives and the migration of notable family characters through letters and diaries, finding herself in the characteristics and choices of her ancestors.

Notably, though, she tells the story of her youth. Of course, it is easier to remember what has happened to oneself, and since she was born in the 1930’s (much earlier than the majority of us, I’m assuming), we still get a great glimpse into the history of a young girl growing up in Middle America in the middle of the century. Some things are the same – I totally connected with her when she talks about how annoying it was to grow up not being Swedish in a school with all these tall, blond, gorgeous girls with perfect last names varying from Hanson to Anderson and Jorgenson. Other parts are things I’ve only heard about – like picking out your house by flipping through a catalogue rather than taking in-depth tours of the property.

The story continues on to telling about her first times living in France, as a single-mother of four children, and working with Stanley Kubrick (whom, she reports, was pleasant, even though he did cut out a whole bunch of lines from Wendy Torrance, leaving the wimpy, crying character on film today (can I just say how glad I was to hear the character wasn’t intended to be written that way?)). There’s some great stuff in here.

Unlike an ordinary memoir intended to tell only about the writer themself, Flyover Lives reads like an invitation to conversation, sort of a “I’ve shown you mine, now let’s see yours” tale. Funny, brave and intensely rewarding, this is the work of a woman intensely proud of her past lives as well as her present.

January 9, 2014

Gaute Heivoll BEFORE I BURN

Before I Burn by Gaute Heivoll

Before I Burn by Gaute Heivoll

A thrilling story of a real-life crime drama, Norwegian writer Gaute Heivoll’s Before I Burn explores a series of fires that ravaged his small hometown during the first days of his life. Written in the style of Capote’s In Cold Blood rather than your typical formulaic crime drama, Heivoll’s retelling is one part his own story, one part the story of the arsonist, his family and friends. It’s less of a mystery in terms of pointing out whom to blame for the fires than in understanding why he started them in the first place. It’s all about the mind of the man, making him human and not a monster.

Starting with a single fire, it seems like a tragedy, but an accident that does happen. Then another fire happens just a few days later. Eventually, the arsonist is so out of control that eight fires occur over a single weekend. The residents of this small Norwegian town feel helpless. Until the arsonist is caught, all the men of the town have become members of the fire department; all the women sleep in fear that their home may be the next. They try to carry on life as normal, celebrating in the new birth and the christening of the baby Gaute Heivoll (yes, actually the author), and carry on as best they can.

Just before these fires started, a young man named Dag returns to his parent’s home, back early from his stint in the military. But, as it seems to his mother, this isn’t the same Dag who left. This Dag is cold and distant, almost emotionless. She can’t put here finger on the difference, but she knows it is there, no matter how much her husband, Dag’s father, may deny it. It doesn’t help that any of the questions she asks her son about his time away are met with silence. Dag seems to be doing just fine outside of their home, even having a knack for fighting fires, something he picked up, following in his father’s footsteps.

If you’re cursing me out right now for pointing out the culprit, you can stop. It’s really not the drama of the story. What is the important part is trying to understand why Dag would start these fires, light up the homes of people he grew up surrounded and loved by, only to jump on the fire engine with his father and help put it out just shortly after. What’s important is understanding how it would feel to go to sleep in this town, not knowing if your home or your neighbor’s would be the next to go up in flames, as if you were living in a small-town “Nightmare on Elm Street” except it’s not just the teenagers that are being targeted and it really doesn’t matter if you fall asleep or not. What is important is trying to understand what it would feel like to be the parents of an arsonist what it would be like to be a mother, trying to talk to the shell of your son, or the father, trying to fight the feelings that something may not be right with your boy.

As I mentioned earlier, a large part of the book is devoted to Heivoll’s own story. Before I Burn tells the tale of his own journey, from being that little boy greeting the world during the same month as all the fires were occurring to accepting his role as a writer. Growing up in a town were everybody knows everybody else, including himself, Heivoll had much more of an insider’s point of view than Capote did while researching. These people already knew and trusted him. Getting these interviews and different sides of the story wasn’t the hard part.

In another piece, we hear from a 20-something Heivoll dealing with his father’s mortality. Getting a nonchalant call from his father who mentions doctors just drained 4 liters of fluid from his lungs as simply as if taking about a routine check-up, Heivoll begins seeing the man he looked up to slip into weaker and weaker states, just as he is coming into his own voice as a writer.

There’s a lot going on in this story and really, the least fascinating part of it is the fires. Before I Burn is a great psychological thriller, bringing you into the heart and the minds of the citizens of this small Norwegian town, leaving you looking differently at the people behind the crimes and the writers behind the stories.

January 7, 2014

Elizabeth de Waal’s THE EXILES RETURN

The Exiles Return by Elizabeth de Waal

The Exiles Return by Elizabeth de Waal

Here’s the story behind this novel: Elizabeth de Waal was the child of a wealthy Jewish banking family, lived in Vienna and studied philosophy, law and economics at the University of Vienna in the early 1920s. With the rise of Nazism and the threat of an invading Germany, Elizabeth and her family wisely fled the country, leaving behind much of their riches. Throughout the 1950’s, Elizabeth wrote five novels, all of which remained unpublished, cherished, yet collecting dust at the time of her death in 1991. The Exiles Return, found and recognized for its potential by her grandson, Edmund de Waal (artist and author of the 2010 memoir The Hare with Amber Eyes which goes into further detail of his family’s history), was one of those five novels.

If what I’ve said to you so far makes you back away, like “nah, that book sounds gimmicky,” get over it. The gimmick isn’t what got this book into print. What did is the book’s powerful prose, it’s tale of exclusions, of trying to find one’s way back into an ordinary life, of love and lose, struggle and the human urge to hold on to hope. Further than that, realize this isn’t some historical fiction written by someone “putting themself in the shoes” of what it would like to be a Jew returning to Vienna, this was written, at the same time, by a Jewish woman exiled from Vienna. This is as real as it gets.

The story itself starts off by introducing the characters involved, all of which slowly connect together throughout the novel’s pages. There’s Professor Adler, a Jewish man once in line to be the headmaster before he fled to America. Unsatisfied with his life in the states, Adler returns to his position in Vienna, only to be told he has been passed in line and to find that he must now work in the presence of a self-proclaimed, unrepentant Nazi. There’s Marie-Thérès, fondly called Resi, a young American socialite sent to the country by her parents in an effort to turn around her attitude problems from home. While in this new place, Resi is forced to come to terms with what it means to be the daughter of a princess after the title has lost its importance. Then there is Theophil Kanakis, a wealthy Greek eager to gather to himself whatever spoils may be seized after all the recent shifts in power, including the prized possessions of displaced Jews and a young woman in urgent need of a husband.

To the young outsider, we often forget how fragile a country becomes after a war. In my mind, it seems as if, by 1950, every Nazi must have repent, known his misdeeds and if not taken into custody, escaped far from the scene of his crimes. Every Jewish family must have been compensated for the possessions seized from them and had their rightful homes returned to them. Unfortunately, it takes far longer than a few (or even ten) years to correct these wrongs. Much of the drama surrounding the characters in Exiles deals with these messy times, these times of trying to return to a life that once belonged to you, a life that once made sense and where everything was in order.

The Exiles Return is far less a novel in the sense of creating new events, new timelines and even new characters than perhaps a reimagining of what early 1950s life was truly like for Elizabeth. In his introduction, Edmund says of this novel: “The Exiles Return is profoundly autobiographical. In the figure of Resi… there is the glimmer of projection. And in Professor Adler… I think there is a strong sense of an alternative life being lived out.” Ultimately, what we get here is an honest account of how life felt to Elizabeth after the war.

In case it hasn’t come across earlier, I loved this novel. Since like fourth grade or so (I forgot which year it was in elementary school that the broke it to us that this big thing called the Holocaust happened), I’ve been an obsessed reader of all novels dealing with concentration camps, Anne-Frank-esque tales of hiding and the like, but this is the first novel I’ve picked up that honestly tells the injustices people suffered after their torment was supposed to be over.

De Waal’s prose is fantastic, her story superb and the subject important. I have no idea what those four other novels are about, nor do I know of their quality (I would have to assume Exiles to be the standout since it is the first one coming to light), but I hope the others are published as well. I’ll be ready and waiting to read them.

December 19, 2013

3 Nons, all Catch-up

(I know: every year around now it’s a scramble to get to books that were read and, for whatever reason, untouched-upon here. All of these books are worth your energy and time, even if the reviews here are brief.)

The Power of Glamour by Virginia Postrel

The Power of Glamour by Virginia Postrel

This book is borderline profound, and that it’s not totally isn’t, necessarily, a mark of any lack: Postrel’s trying to do something fairly grand, in that she’s trying to articulate a whole bunch of stuff about what glamour is and how (and how deeply) it appeals. To do such a thing requires addressing a shelf of abstractions—beauty, style, longing, grace, mystery (to say nothing of class)—and one can sort of see, fairly quick out the gates, how tough such a task would be (just try to define even one of those terms). Glamour, Postrel writes, is basically a believable illusion—this come-hither thing we strive toward (that’s a brutal paring of Postrel’s developed idea), and here, ultimately, is the issue for me with the book: it’s powerful, and it’s impossible to walk from this book not thinking differently about things, and yet…see, this is where it gets hard. Of course there’s not gonna be one book which objectively articulates everything about The Power of Glamour, same as there’s not gonna be one book which objectively articulates everything about, say, Bob Dylan, or archicture. This is getting dicey quickly. What I’d say is this: this is a gorgeous book that will blast you wide open and make you think about conceptions of lots of social appearance things in a much more significant way, very quickly, even if, in the end, you find yourself disagreeing with Postrel about certain things. That The Power of Glamour is not a perfectly coherent book is, the more I reflect on it, a gimme: no one faults Marcus for not Totally Nailing everything about Dylan (or Elvis or whoever), and anyway one ends up feeling massively appreciative simply for the book’s existence, for the fact that it’s opening—quite widely—a conversation the reader may not’ve even been aware s/he’d been longing to listen in on. Anyway: read it (of note, too: it’s a lusciously beautiful book, physically).

Capital Culture by Neil Harris

Weirdly, this book resonates with another I’ve been dabbling in recently (Shone’s Blockbuster): through tracing J Carter Brown’s leadership at the National Gallery of Art, Neil Harris shows the reader how we have come to experience museums as we have. That’s a vague sentiment. Try this: when you go into nearly any major museum in the US, you likely enter a large open space and immediately have the opportunity to purchase stuff from the gift shop and there’s also, somewhere, some cafe-ish upscale food on offer, and the whole trip can end up feeling more like cultural consumption rather than cultural appreciation or anything so elitist and sniffy. Harris, in this heavy-duty+large book, argues (to my mind incredibly convincingly) that we’ve got J Carter Brown to thank for how we currently understand and function within museums, and though one leaves the book with more of a contextualized understanding of Brown than anything resembling straight bio, it is, to this itenerant museum-goer and art consumer, a hugely engaging read: I hadn’t even thought to consider that the contemporary museum experience might’ve once been otherwise (not, at least, in any real way: I just assumed in the past there was some Difference, the same as I consider for just about every experience). It’s a dense but ruthlessly engaging book.

The Dynamics of Disaster by Susan W Kieffer

The Dynamics of Disaster by Susan W Kieffer

Kieffer—a woman you should know more about and to which end you should go here—in The Dynamics of Disaster addresses “changes of state,” which is a sort of fancy heading under which one could put all sorts of things. What Kieffer’s examining here are the physical changes on the earth, and the catastrophes such changes unleash and usher and etc. It’s hard to know how to talk about this book: it’s deeply informative (trying to wrap one’s mind around the distances plates travel in creating earthquakes is a lesson in incredulity), but also deeply (and I don’t mean this entirely critically) pedestrian. This is a book which reads almost as something like a primer for or manual regarding the darker gearing of the earth iself: when weather coalesces to, say, cause a tornado (say, for instance, the tornado that destroyed much of my college during my freshman year), most of us are left—by necessity—reckoning with the manifestations of the tornado: bricks pulled from the chapel, windows blown out, etc. Kieffer takes the reader deeper into the how of the tornado (or earthquake, or whatever), and, to that end, the book’s entirely great and wonderful…it’s just staid. That said, whatever it lacks in the riveting category, The Dynamics of Disaster more than makes up for in the wait, seriously? category.

December 17, 2013

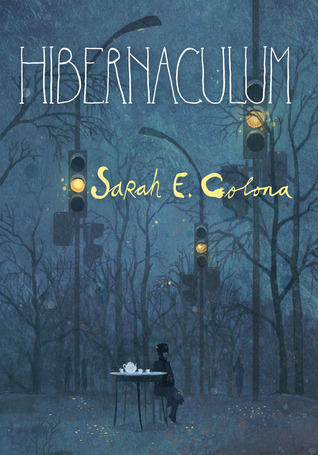

Reading Hibernaculum: Sarah Colona’s Traps of Enchantment

(Today’s post is a guest spot from Tasha Cotter, whose first full-length collection of poetry, Some Churches, was published in 2013 with Gold Wake Press. You can find her online at www.tashacotter.com)

Sarah Colona’s debut collection of poetry, Hibernaculum (Gold Wake Press, 2013) is a collection meant to protect us from winter. Like the title suggests, these poems offer us a kind of winter residence and through their insight and questions, we are safer for having read the collection.

Sarah Colona’s debut collection of poetry, Hibernaculum (Gold Wake Press, 2013) is a collection meant to protect us from winter. Like the title suggests, these poems offer us a kind of winter residence and through their insight and questions, we are safer for having read the collection.

The collection begins with a family’s winter homecoming, but the reader quickly senses there’s an element of unsteadiness—a quality to this gathering that’s darker and more dishonest than one would initially think. And we soon come to see that even amidst the people we know, we are sometimes deeply alone at such gatherings while simultaneously being fed the ideas of others. In this collection, such received wisdom usually comes at a price. Colona says it best when she writes: “A lullaby curse to always love less.”

The Poet is at her best when she is brief. Her gift of precision shines brightest in poems like, “Waxed Lachrymose,” “from her lips/ stilled bees fell.” Throughout the collection there’s an array of poems that touch upon ideas of femininity and womanhood. One passage in particular that speaks to the idea of what Colona is after can be found in her poem, “Memory and Forgetting”:

Always this

Disappearance

This impending loneliness

This is a book of mothers and daughters, of received wisdom, and what we choose to abandon. This is a distinctly feminine voice and these poems are little cautionary tales of fairytales gone wrong—but make no mistake— the speaker is no longer under any illusions. These poems are songs of experience.

Though clearly gifted in using poetic forms, there are many narrative-driven, free-verse poems here as well. Over the course of the book one begins to discern a whimsical quality to this book. I noticed a Grimms fairytale was alluded to and another poem was inspired by Cocteau’s Beauty and the Beast and it’s this poem, “Interlude,” that’s my favorite. Colona infuses the story with her own touch of magic and the story glistens with her touch, creating a new way of seeing a familiar story.

The last section of the book takes on a darker momentum. The speaker’s wry humor seems to have evolved over the course of the book and appears in these poems as being informed by experience.

Mythology is found throughout the collection and creates a bedrock for Colona’s themes of womanhood. Colona writes in the Notes section of the book, “most poems found in the second section have been inspired by the tale of Cupid and Psyche, and its subsequent derivations, which includes Beauty and the Beast.” I appreciated the summoning of these myths—their emergence and the interplay of myth and contemporary experience made this book a uniquely perceptive read, allowing the reader to sense that our own experiences are no less extraordinary or tragic, than the stuff of legends.

December 13, 2013

Morrissey’s AUTOBIOGRAPHY

Can you NOT remember the very first time you heard Morrissey’s voice? That deep, twisted baritone paired with his falsetto, his dark, lovelorn lyrics… for many, it’s like watching a horror movie: you listen through your fingers at first, scared by this new sound and eventually, you just can’t not engage completely. For me, that first song was “There Is a Light That Never Goes Out,” way back in sophomore year of high-school. Listening to the song, immediately looking up the lyrics – “And if a double-decker bus / Crashes into us / To die by your side / Is such a heavenly way to die / And if a ten-ton truck / Kills the both of us / To die by your side / Well, the pleasure – the privilege is mine” – dear god, could there be any better lyrics for a 15-year old in love for the first time? It was like the man knew my soul.

I’m sure most of you have a similar memory of the man. Steven Patrick Morrissey, as a solo artist and as the lead singer of The Smiths, has become so big in our indie-is-chic, underground for all culture that his name sits up there with icons such as Mick Jagger and David Bowie, yet somehow, every fan feels so unique in their love for him, kinda like he’s the underdog we’re all rooting for.

Given his popularity and the way common-culture has begun to so whole-heartedly embrace his music (a phenomenon incomprehensible to Morrissey himself as he says in Autobiography), I’m going to assume a lot of you reading this will have heard at least a few of his songs, and caught at least a few of his lyrics. Most themes of his songs are the same: being alone, having someone but then they left, bleakness, martyrdom and general despair. Expect nothing less in his book. Don’t take this as a bad thing, though. I mean, I freakin’ LOVE Morrissey. I love The Smiths. Yet, those songs are all mopey. So, is it really so far a stretch to love a mopey autobiography as well?

Here’s the way he pulls it off: Morrissey can truly write. Every sentence feels like it could be turned into lyrics, with witticisms and “such is life”s throughout. Beginning basically at his birth, Morrissey goes through the story of early life, from his days dyeing that famous quiff bright streaky yellow, up to the present. Morrissey speaks of his first loves (albums from New York Dolls, Patti Smith and David Bowie listened to at record shops, brought home and cherished), his hates (Margaret Thatcher, very apparently, as he calls the former Prime Minister a power-mad, “philosophical axe-woman with no understanding of personal error, as well as probably his biggest hatred, the entire meat industry and all its cogs) and his many many legal battles.

Interestingly enough, one thing completely not mentioned, at least in the American editions of Autobiography is any hint of a sex life. In the American-edition, Morrissey comes off as essential celibate, highlighted by a conversation between the man and David Bowie: “David quietly tells me, ‘You know, I’ve had so much sex and drugs that I can’t believe I’m still alive,’ and I loudly tell him, ‘You know, I’ve had SO LITTLE sex and drugs that I can’t believe I’m still alive.’” HOWEVER, in the European edition, which came out a bit earlier this year, Morrissey had apparently included many more details about the two-year relationship Morrissey had with photographer Jake Owen Walters. According to Spin, Walters’ role has been downplayed in the American edition, his name written out of entire narratives and even one of his pictures is removed from the copy. It raises a lot of questions – mainly, did Morrissey or his publishers do this? and also, did they think Americans wouldn’t notice? I mean, I found out and I didn’t even dig. I was just on Spin looking at there list of 2013’s Top Albums and I happened upon this fact. Anyone INTERESTED would find out in a second.

Anyway though, this is a fantastically balanced memoir. Morrissey does take his share from the pool of karma, pointing out just how great of a bitch Siouxsie can be, how he now feels about his once-partner Johnny Marr and harshly, how much he is looking forward to seeing certain journalist gets their dues (which he believes would include some sort of brutal murder scenario (yikes)), but he does admit where he was wrong in the past – for instance, he thought “There Is a Light That Never Goes Out” could be dropped off The Queen Is Dead. Most endearingly, though, is the way in which, through this all – millions of record sales, tributes, tattoos, sold-out shows, Morrissey still doesn’t quite see what the big deal is about.

December 11, 2013

An Interview with Omar Yamini

Author Omar Yamini

I read somewhere online that one out of nine African American men will spend time in jail between the ages of 20 and 34. No subtext here on the flaws in our system that have caused those numbers to be so high, no tirade about white privilege or anything else. It’s simply a statistic, and for Omar Yamini, that number needs to change. Yamini spent 15 years, from the ages of 20 to 35 in the Illinois prison system, experiencing first-hand what most of us know little about aside from watching “Orange is the New Black.” After getting out in the summer of 2011, Yamini began writing his story in a book, What is Wrong With You? that pairs with his non-profit organization, Determined To Be UpRight, to warn young people about the realities of serving time. I talked to him recently about his book and further into that experience:

When did you decide you wanted to write this book?

I wanted to write this book soon after I got out. My mother was a strong influence on me writing this book. When I was in prison, she used to always tell me “Omar, you need to write a journal. You need to write a journal so you can tell people what it is that you are seeing and witnessing. The way you are explaining things to me, people need to hear.” I would write letters to my mother and to my family and to Carrie (Yamini’s wife) explaining to them what is going on, telling them some of the behaviors of the people in prison. It was during one of those times that my mother told me that I need to write a journal. She said that for years, until I actually started to do it in my last year of imprisonment.

What would you consider to be the one worst thing about prison?

The worst part of prison is being without your family. Being in a place around people who don’t care, and this can be inmates or correctional officers and having to deal with strangers who don’t care about you or anybody else, and having no family to help you through those hard times. The hardest thing about prison is being without your family, without the people you love and trust the most. That’s the hardest. Because you need them. You really understand the meaning of family when you are in a situation where you need people that you trust the most.

Did you get a lot of visitation time?

I was one of those people who was blessed to have a supportive family. Whenever I needed to see someone in my family because times were getting rough, somebody was always there, whether it was a brother or a sister or Carrie, someone always showed up. My mother had a hard time seeing me in prison. It was too much. I did not see her until the last two years of my sentence. However, I talked to her all the time. She answered all my phone calls. She answered all my letters. It wasn’t abandonment; it was just, “I cannot see you in prison like that, so call me.” And I was blessed to have that. That correspondence was just as important as visitation.

Do you think your experience would have been different if you were a white man?

Yes, absolutely. American white men, for the first time in their lives, find themselves a minority. Some of them struggle, and some of them don’t, but they see what it’s like to have to go to another people, another race, who are pretty much the overwhelming majority, to get the things they need inside of prison. Some white men struggle with that. Not all, but some find themselves as part of supremacist groups. Some of them aren’t even racist, or even prejudiced, but they feel that they need to belong or need some protection. Now, the County Jail is another story. At Cook County Jail, I witnessed white inmates get treated really bad. A lot of young, wild gangbangers who were looking for some get-back, men who were probably going to lose their cases, especially the violent ones, because the conviction rate is so high in Cook County Jail, so many of them have no hope. They look to take out their frustrations on anyone they chose. And because you’re dealing with a gang affiliation, white men in Cook County Jail don’t have those protections. They’re pretty much on their own.

One of the strange things about white men in prison is that it can vary with the guards. Sometimes other white prison guards may give them special favors; and sometimes, you see the prison guards really mistreat them for being white in prison. Like they’re saying, “you wanna act like these other savages, we’re gonna treat you like one.” You never know how a white prison guard is going to treat another white man.

In the book, you mentioned meeting a man with an 850-year sentence…

Yeah. And beyond. It was heart-brekaing. It was dismal. It’s a feeling of complete despair. Probably the most depressing thing that I’ve ever been around. It set me straight. It made me give up any complaints about how much time I had left on my sentence. And I knew some of these guys that were getting mountains of time, Star-Trek time we called it, just light years. With my own eyes, I witnessed 20-year-old African Americans and Hispanics come back from court from their sentencing day with 250 years or 90 years or 430 years, and one guy, an old cellmate of mine was given 847 years, or something crazy like that. It was like, “we don’t stand a chance in here.”

Yeah. What kind of attitude would you have after getting that kind of sentence?

I guess that depends on the person. For me, it was what do I say? What kind of conversation can I possibly have with this person that just got 700 years? Some of those guys exploded before they transferred out. Some would start riots. It was terrible. It was worse than someone having a loved one pass. We deal with death in life, you can go and console the person that loses a mother or a child. But how do you console a person that’s gonna spend 800 years in prison? What do you say? What do you tell them, it’s gonna be okay? When you know this person is about to die in the penitentiary?

It was these dynamics that added to the mental and emotional stress that everyone was going through. I’m not making these statements to say that these people didn’t deserve it. Some of them probably did for the heinous crimes they committed. But that wasn’t the point of my book. The point of my book is a look into the conditions, and explaining these conditions to young people. These young people may not like the situation they’re in. They don’t like the financial situation they’re in, or they want to impress another person, or they want to belong. But when they get what’s coming, it might be 280 years.