Weston Cutter's Blog, page 16

November 26, 2013

Some New Music

A review of Bob Schneider’s Burden of Proof

Bob Schneider is tricky. It always seems like the Austin-based songwriter’s best stuff occurs when he’s trying not to be serious. His first album Loneyland is rife with moments like this, instances of tongue-in-cheek silliness that resonate with a peculiar sort of elegance, as is 2006′s Californian and many of his live recordings. Ironically, the times in which Schneider actively strives for meaningfulness tend to result in tunes that are so-so at best. Unfortunately, Burden of Proof is one of the latter.

The songs here aren’t altogether bad, they’re just, well, sort of forgettable. Laden with moody strings–courtesy of the Tosca String Quartet–and minimalist synth beats, the album aspires for a kind of depth that just doesn’t seem to come naturally to Schneider. The opening track “Digging for Icicles” sets a somber tone. The tone isn’t a bad thing in itself, except that its complete bereft of Schneider’s trademark wit and I-don’t-give-a-damn-what-you-think-of-me attitude. Thankfully, we do get a bit of this on tracks like “Wish the Wind Would Blow Me,” a quiet, whimsical love ballad, and “Unpromised Land,” a rollicking testament to youthfulness. This is really the high point of the album; it’s Schneider’s comfort zone, braying hoarsely at the top of his lungs over grinding guitars: “Those freaks you dig/ the ones you call your friends/ the ones who just don’t know/ when the party should end./ They can go to hell./ They can fuck right off./ I mean, Jesus Christ/ haven’t you had enough? Moments like this it’s easy to tell that Schneider is enjoying himself, which has made so much of his previous work so much fun.

Beyond this, however, the album drags. Slow and mournful don’t come easy to Schneider, and I’m not suggesting that he can’t pull it off or that, worse yet, he has some obligation to stick with the “fun” stuff. It’s just that Burden of Proof seems too tidy, too neat and polished to leave an impression. Schneider has no problem pouring his heart out, and there a few very stirring moments on this album, but not enough to elevate it beyond something backgroundish–quaint and enjoyable but ultimately subpar.

A review of Gregory Alan Isakov’s The Weatherman

I don’t actually remember how I came across this guy, only that once I did I was baffled that I hadn’t heard of him sooner. The fifth album from the South African singer-songwriter, Isakov’s The Weatherman is at once gorgeous and heartbreaking, a collection of stunningly beautiful tunes from a remarkably talented artist.

Now, let me be clear: I’m using that word “indie” begrudgingly because, frankly, I hate the term, its ubiquity, the beyond-reproach way it is applied to music that people either don’t know how to review or are too afraid to do so. In the case of The Weatherman, however, it’s applicable: the album was produced and recorded by Isakov himself using outdated analog equipment that lends the album a haunting, echoey resonance. And yes, I realize this isn’t a new thing, this circa early 70s hyper-reverbing you hear in most “indie” music (just like the artist’s Depression-era Dustbowl farmer aesthetic [*eye roll*), but it just somehow works here.

Part of it is the simplicity of the songs: stripped-down and unassuming, most of them follow a charming waltzy rhythm that elevates them (slightly) beyond the typical sad-bastard pace of most indie rock. The album is rich with banjo, guitar, and mandolin strings, all of them complimenting each other, creating a soft, wistful atmosphere. Isakov seems especially interested in the artistic qualities of memory, the ways in which we choose to remember the past, how sometimes it’s even better than the events to which it corresponds, because we can’t change them but we can change the way we remember them. We can reimagine them, we can streamline them through hindsight. Consider the lyrics to “Saint Valentine”:

well, Grace she’s gone, she’s a half-written poem

she went out for cigarettes and never came home

and I swallowed the sun and screamed and wailed

straight down to the dirt so I could find her trail

spread out across the Great Divide

To Isakov, the act of remembering seems poignant and powerful because, I think, that’s really what everything comes down to, a memory. The Weatherman acknowledges loss after the fact, exalting the past rather than mourning it. It’s a heartfelt collection of songs, well-crafted, infinitely listenable.

November 19, 2013

Simon Garfield’s TO THE LETTER: A Celebration of the Lost Art of Letter Writing

TO THE LETTER by Simon Garfield

TO THE LETTER by Simon Garfield

I’d have to guess I find a postcard or handwritten note in my mailbox probably twice a week. I absolutely realize this isn’t common; I was the odd girl of my friends in college that always had something in her mailbox, mainly because my mom is obsessed with snail mail. She’s constantly sending a stream of postcards (more often than not, postcards with pictures of my home state Minnesota, icehouses and loons. Sometimes they’re strange, though. One was like, a photo of Jewish Quilt; another the state capital building) and cards made by local artists or one of her friends who’s really into photography, gluing glossy 4x6s onto cardstock. And it’s not just to me – she sends postcards to my friends all the time. For instance: her birthday just happened in October, and my boyfriend sent her a card, to which she sent a postcard saying thank-you. My childhood best friend says she gets cards at least once a month from her.

That’s the thing about her cards as well – I can’t recall one in which she sent “big news.” Most of the time, it’s just a few sentences on the mundane: “Your brother and his girlfriend were here this weekend. We all saw the new James Franco movie. It was all right. Wish you could have come, but I’ll see you next month!” “Your uncle is still losing weight. Only 20 pounds til his goal!” Things like this mainly.

Here’s three main things her letter writing (I’m calling it letter-writing; her cards may be short, but they relate more to a letter than a text/email/etc.) has taught me: One, it’s ALWAYS good to come home from a long day to find a hand-written envelope waiting for you. Two, what you say doesn’t matter. I remember some cards that were literally this short: “Hi! Two weeks til vacation! Love, Mom.” And three, like every relationship, every correspondence is entirely its own, with its own rules and courtesies, its own personality.

It’s that last point that comes out most clearly in Simon Garfield’s newest book, To the Letter – letters have been and will continue to be deeply personal, unique to each pair of sender and receiver. In his book, Garfield tries less to study the facts and figures of letter writing throughout the ages than to look deeply into the actual letters and people behind the lines.

The book starts in the B.C.s with some of the first known letters from ancient Vindolanda, Rome, and tracks the time in letters since then. The early days’ letters include a first-hand account of a survivor of Vesuvius’ eruption (of which the man concludes “Of course these details are not important enough for history, and you will read them without any idea of recording them”), the graphic love letters of Abelbard and Helouise and perhaps the greatest letter-writer of her day (the latter half of the 1600s) Madame de Sèvingè.

A large portion of the book details the habits of famous author’s letter writing. There’s Jane Austen, who as Garfield describes, wrote terribly boring letters, detailing mundane details of her days, often using the “cross-writing” technique of writing the usual way, then turning the page 90 degrees and writing on top of the lines. Virginia Woolf, unsurprisingly, wrote a pair of suicide notes before her death, voicing her concerns that she was once again going mad. And even though he was in the limelight after the rise of emails, there are notes on David Foster Wallace, including letters written from super-fans to the publishers correcting them on mathematical mistakes in Infinite Jest.

Although there’s less of this than specific, personal examples, some of my favorite parts were the descriptions of some rather interesting aspects of letters and the postal service’s previous methods. For instance, to communicate “My heart belongs to someone else,” simply place the stamp on its side in the top left-hand corner. That way, the scorned wouldn’t even need to read the letter to be let down! Or, I’m sure you’ve heard a joke or anecdote about someone being mailed to their destination, but many of you probably didn’t know that a man actually did send himself through the post (although unfortunately, not in a box like I wanted to picture in my head).

I could go on and on about all the fun stuff this book includes. I mean, I haven’t even gotten to the love letters between a British WWII signalman and his sweetheart back home running through the book. The thing is, I could write 2,000 words telling you in detail all my favorite parts of the novel without giving a complete review, simply because, like all letters, your favorite part of this book will be completely personal.

November 12, 2013

Two New Music Bios

AC/DC: Hell Ain’t a Bad Place to Be by Mick Wall

By now, it’s hard for an American to have NOT heard a song by AC/DC. Even if you weren’t the type to play Highway to Hell over and over trying to teach yourself the chords on your Fender during high-school, chances are you’ve heard “You Shook Me All Night Long,” “Thunderstruck,” or “Back in Black,” or at least seen the now iconic covers. It’s hard not to at this point – they’re used on soundtracks to everything, parodied by everyone and listed on so many Rolling Stone’s “Best of” lists (Angus Young coming in at the 24th greatest guitarists of all time; the group itself making number 72 on the list of 100 greatest artists of all time).

It’s not surprising it’s these guys UK rock writer Mick Wall would pick these guys as the focus for his newest book, AC/DC: Hell Ain’t a Bad Place to Be. Here’s where his take is special: Wall’s actually meet Malcolm and Angus Young, Bon Scott and Brian Johnson. At one point in the book, Wall actually writes himself into the story, interacting with a spiraling Bon. So although not a member of the crew, nor current official management, responded to his requests for interviews for this book, Wall’s got a stock-pile of previous interviews and past experience to draw on while writing. Oh, plus, he did get new interviews from a whole bunch of major characters in the story, including their former bass guitarist Mick Evans, Phil Carson (the guy who signed AC/DC to Atlantic Records), the original lead singer Dave Evans and many many more.

There’s great band history going on here – starting from the success of George Young (older brother and  later, manager of Malcolm and Angus Young’s AC/DC) in the Australian music industry and going all the way to recent matters, such as the Iron Man 2 soundtrack (which seemed like something I might not want to brag about, but hey, to each his own) – but in my opinion, the best part is getting some insight into the personalities of each of the characters. There’s the troubled lead singer, Bon Scott, the oldest and last member to the group, a guy who tired of the road and the fame. There’s the clear-cut leader behind all the band’s decisions, rhythm guitarist Malcolm Young. And, my personal favorite, the surprisingly clean-cut Angus Young, a champion-guitarist who preferred milkshakes to whiskey and really, more than anyone else in the band, seems to be in it just for the music.

later, manager of Malcolm and Angus Young’s AC/DC) in the Australian music industry and going all the way to recent matters, such as the Iron Man 2 soundtrack (which seemed like something I might not want to brag about, but hey, to each his own) – but in my opinion, the best part is getting some insight into the personalities of each of the characters. There’s the troubled lead singer, Bon Scott, the oldest and last member to the group, a guy who tired of the road and the fame. There’s the clear-cut leader behind all the band’s decisions, rhythm guitarist Malcolm Young. And, my personal favorite, the surprisingly clean-cut Angus Young, a champion-guitarist who preferred milkshakes to whiskey and really, more than anyone else in the band, seems to be in it just for the music.

It’s a book for fans, most definitely. There’s less going on about the actual music, less trying to show the wit and wisdom of their songs than showing the politics surrounding it all. But, for those who’ve been die-hard fans since the seventies (or since they heard “Highway to Hell” for the first time at 14 and thought “these guys get it”), and those who want to learn more about one of the biggest groups still rocking, this is a great place to start.

Duke: A Life of Duke Ellington by Terry Teachout

Duke: A Life of Duke Ellington by Terry Teachout

I don’t have a great context or understanding of the catalogues of jazz music, but whenever the Duke was mentioned, first thoughts always went to Class. Rather than the fun, quirky, hooting and howling kind of jazz, Ellington’s music steered to the elegant side, the kind of artsy jazz the piano players in Nordstrom’s are always playing rather than the jazz going through dimly-lit nightclubs. In theory, at least, that’s how I associated the Duke (although in reality, for every “Mood Indigo,” there’s an “East St. Louis Toodle-o”).

I’d have to guess Terry Teachout has a similar view of the man, born Edward Kennedy Ellington. In each chapter, Teachout upholds him as a man of style, a genius composer and a finer version of the typical nightclub bandleader. Not to say Teachout sugarcoats any of the Duke’s qualities – he’s no sucker to the Duke’s womanizing (although legally married to only one woman, Ellington lived with another for decades, and even then, spent many nights with woman not even his main mistress), his compulsion to keep family members and loved ones in the palm of his hands, or even the near-hypocrisy of the segregated clubs where Duke and his band first hit it big.

Starting with Duke’s childhood in U Street, Washington D.C. and concluding with the legacy that followed him, Teachout charts every move across the nation, the big members and managers of the Duke Ellington bands, the main ladies in his life and the surrounding events of his top songs (ex: “In a Sentimental Mood” came just after the loss of his beloved mother).

Thrown into the background is a Civil-Right’s timeline, perhaps one of the most fascinating points of the book. From the roaring ‘20s, where the band’s main stage was Harlem’s Cotton Club, a place that Cab Calloway once said “the idea was to make whites who came to the club feel like they were being catered to and entertained by black slaves,” to the days in which Ellington and his band were the papers’ top stories, yet rules didn’t even allow the paper to print a picture of the black man. Yet, Teachout admires the way Duke dealt with the racism, taking the high road in most cases and carrying himself as a man of class no matter the situation, even elevating him in comparison over his contemporary jazz-great, Louis Armstrong, who Teachout perceives as more of a clown for the audience and somewhat of an “Uncle Tom” of the jazz scene.

Whether you’re a seasoned fan with the Duke’s catalogue fully memorized, or like me, someone who appreciates his songs one at a time when in the mood, Duke is a great read. Informative, honest, fun yet heart-aching, it’s a story of a great man that truly echoes his legacy.

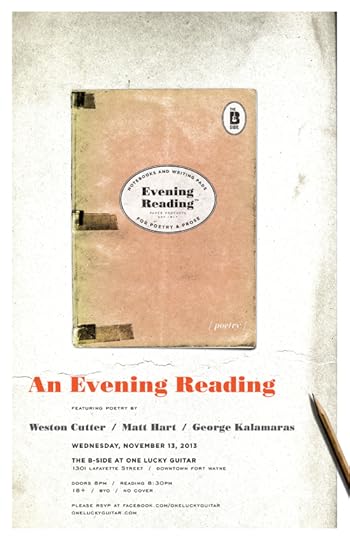

October 31, 2013

Nothing Huge

Here’s some elsewhere stuff (and: happy halloween):

1. A piece of fiction on the great Fiddleblack.

2. This thing answering the prompt “why write” for Green Mountains Review.

Also–and with apologies for breaching the disinterested tone of reviewing–if you’re remotely near Fort Wayne in November, there’s a reading downtown that should be cool. Details here.

October 28, 2013

Recent-ish Roundup

As ever, there are more books than time. Here are four titles that deserve your time and attention more than the brief-ish mention they’re being given here.

This is one of those straightforward propulsively readable things you finish and wonder why you don’t read more of: Buried Treasure is the story of a family blasted apart by a variety of incidents (a boy’s kidnapping; a father’s alcoholism; a mother’s death), and the attemps those who remain, suriviving, make to keep living, keep being something more than merely fatigued walking scars. Like lots of first books, Downs’s debut lags in a couple ways: in the first bit, the pace is too slow (the reader can almost feel the pieces being fit together, the machinery coming to life), though soon enough the story gets its bearings and moves along. Then there’s the issue of dovetailing—I don’t know what term you use for this, but it’s the thing in books (or movies) in which the story’s needs trump those of the characters. This happens here mostly in dialogue (which tends toward overexplanation and a thoroughness that’s lacking in actual day-to-day speaking). Neither of these are huge problems: ultimately, the book’s eminently readable.

The Disaster Artist

by Greg Sestero and Tom Bissell

The Disaster Artist

by Greg Sestero and Tom Bissell

I had not, before reading The Disaster Artist, seen The Room, a movie I was made aware of (like who even knows how many people) by Bissell’s essay in Harper’s in 2010. Further, I’m seemingly termpermentally unable to like things ironically—I understand kitsch as a concept, but I don’t…there’s something charmless and cold about liking stuff that one doesn’t simply feel, like a kick to the chest. I’m sure that sounds all sorts of earnest (I’m midwestern, after all). Whatever. The point is: even now, having seen The Room, I’m not taken with it—its cult-creating ability would’ve missed me. It seems a strangely sad movie about things not being comprehendable, but I suppose that’s got more to do with my own feelings than anything.

All of which to say: even for not much caring for or about the movie the book’s centered around, I was fairly well taken by The Disaster Artist. Sestero plays Mark in The Room, the guy who sleeps with Johnny’s fiancee, all of which, whatever: the book is about Tommy Wiseau, an actor Sistero met in an acting class, and who, somehow, puts together The Room—starring and producing and directing and micromanaging it to death—for $6M. What the book ultimately reads as, however, is a sad and un-understandable story of one guy who’s big dream—making this movie, telling this story—comes true, yet the resulting movie’s so absurd it all but occludes whatever was originally compelling about the dream. The Disaster Artist is a great book about one of the weirdest movies ever made. Go try it out. See what happens.

Shady Characters by Keith Houston

Shady Characters by Keith Houston

This book’s actually just all sorts of fantastic: subtitled “The Secret Life of Punctuation, Symbols, and Other Typographical Marks,” it reads like a bit of kin to Just My Type, a book also fantastic and all about fonts. What Houston does here is focus on specific symbols, and, no, you’re right: one would not necessarily guess or believe that the history and development of, say, the octothorpe (#) would be riveting, but it really, really is. Ditto the history and development of the @ symbol, and the ampersand, the interrobang, etc. It’s riveting stuff.

And not just the history and development of this stuff: one of the things Houston does very well is trace the significance of *why* these things came to be (asterisk’s in there as well, yes), and what we’re given, because of this, is not just an appreciation for the specific symbols, but an appreciation for the code of written communication, for all the magic and utility it offers.

I’ve got the first few seasons of The Muppet Show, and I still find myself absently humming the theme to Fraggle Rock and Muppet Babies, and I think Kermit the Frog and Grover and the rest of the Sesame Street muppets are as culturally significant as any other characters created in the last half century, all of which means that I was a goner for this biography of Henson before I even cracked it. Fortunately, the book’s one of those great bios—likely, given Henson’s stature, there’ll be more, but there needn’t be: Brian Jay Jones has covered the man’s work thoroughly, dancing that fine line between respectful coverage and dirty-underwear-sniffing overexposure (especially, for instance, regarding Henson’s first marriage, a relationship grounded in creative energy and a shared pursuit [Muppets], the sort one regularly reads about when it comes to talented artists chasing their visions). There’s almost too much good stuff in here to tweeze particulars out in praise of their unique fascination—where to start? With the fact that puppetry was, in the 1950′s, offered through home ec departments in colleges? Or that Henson got his start (like so many others) in advertising? Or that Kermit was originally blue? Or to read about how much and fervently Henson believed in and cared about Labyrinth? It’s all in there, and it’s all great, but the real joy’s in something like the amazement offered as you read along and realize this all happened to/because of/through this one guy, this genius who, awfully, died shockingly young from an infection. Easy, at the book’s end, to play the game, to wish Henson’d've gone to the doctor sooner; hard to reckon with the size of his talent and vision and the fact that it’s not coming back.

October 27, 2013

Dropping Science: George Bishop and Dave Goldberg

The Night of the Comet by George Bishop

Typically, when a book starts out bad, it tends to be altogether bad. It’s very rare–in my experience, anyway–that a book whose first 70 pages or so are crammed full of clichés and hackneyed writing manages to right itself by the end. And so I was pleasantly surprised by George Bishop’s The Night of the Comet, a coming-of-age story that comes dangerously close to collapsing under the weight of its own hokeyness.

Typically, when a book starts out bad, it tends to be altogether bad. It’s very rare–in my experience, anyway–that a book whose first 70 pages or so are crammed full of clichés and hackneyed writing manages to right itself by the end. And so I was pleasantly surprised by George Bishop’s The Night of the Comet, a coming-of-age story that comes dangerously close to collapsing under the weight of its own hokeyness.

The book begins with our narrator Alan Broussard, Jr. receiving a telescope for his fourteenth birthday from his father, an astronomer-turned-high-school-science-teacher and all around geek. The elder Broussard’s hope is that he and his son might use the telescope to follow progress of Comet Kohoutek, with which the man is more than a little obsessed; he even convinces the mayor to host a viewing party in the town square. However, Junior uses the telescope to spy on his new neighbor Gabriella, whose well-to-do family has recently moved in across the inlet that separates the two families’ properties (Gatsby, anyone?). Meanwhile, the comet creates a divide between Junior’s father and mother, the latter of whom dreams of a more glamorous life and, to this effect, becomes infatuated with the new family across the water.

As a narrator, Alan, Jr. is …underwhelming, with his Bradyish sensibilities and his predictably wholesome devotion to his parents: I’ve never met a teenager who enjoyed the tale of when his parents first met as much as he does, so much so that he practically recites it by rote as his mother retells it upon request–but then maybe I just hung out with the wrong people when I was younger. The bigger issue is his voice, bland and toneless, not all that dissimilar from his father’s. This isn’t really a problem in terms of plot, but it doesn’t exactly make for a compelling read, either

The story ticks along in a predictable fashion–Alan, Jr. nervously pursues Gabriella, who is dating the class jock; Alan, Sr. tracks the comet with a mad scientist’s zeal; Mrs. Broussard, feeling neglected by her husband, grows distant and disenchanted with the marriage. Frankly, there’s nothing really new here; the whole thing feels dated and anachronistic, as if Bishop is writing about the kind of sugarcoated past the memory can’t help but conjure.

But then something happens, I don’t know how to explain it, the story shifts, the book takes on a new focus, or maybe it just hones its original focus. Somehow, Bishop steps out of the realm of cliché into a truly moving story about the realities of love, the cold truth about what “coming of age” actually entails. It’s interesting, partially because I’m not sure if its intentional, this shift, although I can’t say if that’s a point in its favor or not.

Frankly, though, I think the question of intent here is irrelevant; all that matters is what we’re left with, a flawed but charming tale about the blurry boundary between adolescence and adulthood. The Night of the Comet doesn’t execute a complete 180, but it’s enough to leave the reader feeling somewhat satisfied.

The Universe in Our Rearview Mirror: How Hidden Symmetries Shape Reality by Dave Goldberg

The Universe in Our Rearview Mirror: How Hidden Symmetries Shape Reality by Dave Goldberg

I saw The Matrix on a rainy Easter Sunday, close to midnight, in 1999. I was with my friend Brad, both of us high school students at the time, a year from graduating and aching to escape our prim little Louisiana town. After the movie, we went to a nearby Waffle House and, over cigarettes and burned coffee, discussed the movie with the flighty acumen you’d expect from folks our age; we talked about time and reality, whether or not God exists. We said things like “If we can’t even know if God is real, how do we know if, like, we’re real or whatever?” I cringe now think of this conversation. To the people sitting nearby, we must have sounded asinine, but we didn’t care; the movie had gotten us into a philosophical fervor, and at that moment talking through these questions seemed like the most important thing in the world (I also wasn’t getting laid back then, in case it wasn’t already obvious).

It’s these kinds of questions that form the foundation of Dave Goldberg’s latest book The Universe in Our Rearview Mirror: How Hidden Symmetries Shape Reality. Advertising itself as a stoner’s guide to physics, the book addresses such topics as relativity, quantum mechanics, black holes, antimatter, and the philosophy of time, all through a somewhat sarcastic lens of pop culture. Goldberg’s interest in these topics is the presence of symmetry–the tendency, for instance, for particles to “spin” in tandem with their counterparts, or the balancing effect of matter and antimatter. The writing is thorough but accessible, employing enough real-world analogies for the laypersons among us to grasp some of these weighty concepts.

Goldberg does have a habit of getting sidetracked, making it tricky at times to follow him; each chapter seems to meander through a series of semi-related ideas before revealing an actual focus, which, for folks like me who are baffled by any physics concept more complicated than Newton’s falling apple, can be frustrating. There’s also his constant interjections of self-deprecating humor, which get a little predictable and sometimes come across as snotty; Goldberg himself refers to the kinds of hypotheses he’s addressing as “stoner questions” and gets in a couple jabs at the Twilight series. Hardly a crime, I know, but it’s like, of course he would rag on Twilight, it’s sort of the whipping boy of anyone afraid of being taken too seriously–it’s just so easy, you know?

The point being, I suppose, that Goldberg’s aim here–elucidating the mysteries of the physical world in the context of symmetry–is noble, but his attempts at teenager-ish irony undermine this in a way that doesn’t make the material any more easy to understand and, at times, is just downright annoying.

All the same, it’s a quick and interesting read, more or less fun, especially if you’ve ever sat in a Waffle House at 2 AM and waxed philosophically with fellow losers. I think the real purpose here isn’t to explain these concepts but to give credence to those lofty, abstract questions that drift into our minds from time to time. And I think that’s a good thing, helping us to recognize that “stoner questions” are kinda what physics is all about–I just wish Goldberg could have found a slightly less insulting way to phrase it.

October 26, 2013

Michael Farris Smith’s RIVERS

This book actually came out more than a month ago, and I apologize for not having been of service and mentioning it then: I should have. More people should have. I’m mildly amazed this book didn’t get a sharper/more amazed response from everyone, but who knows.

What the book is: a novel that could be maybe said to be set in some ‘dystopian future,’ and I suppose sort of is, but it’s only very very barely so (the when of the novel hardly matters—post-Katrina is the biggest thing—and Rivers feels dystopian the way No Country for Old Men feels dystopian: less about some anti-utopia, more that you’re reading about some elemental aspect of the world as it presently exists, it’s just that you’ve been able to not focus on or think about or consider that aspect). Set in a perpetually storm-smacked and rained-on and nature-savaged Gulf Coast, Rivers presumes something called the Line, which Line (echoing Mason-Dixon) marks the limit of where someone in the US can expect aid. Right, exactly: if you live below the Line, there’s lawlessness, roving bands of theieves, violence—a total lack of the social structures that keeps society from chaos and anarchy.

And of course such a Line demarcates folks in a clear and obvious way: those below the Line are there for *something*. Smith’s metaphorical conceit allows sideways thoughts and considerations about things like immigration and poverty (if you’re below the line and haven’t the means to get north and across, what do you do?), but what you ultimately care about is Cohen, a guy choosing to live below the Line for what are not, at the outset, clear reasons (other than good old sentimentality). The reader learns he’s lost his wife and unborn child (shatteringly, both [presumably] experientially but also linguistically [Smith's just a total master, but more on that in a bit]), but there is, of course, more to his willingness to stay below the line.

Honestly, one needn’t know much more: eventually he makes his way above the line. Eventually he comes back. There is death and retribution of a Biblical sort one associates with McCarthy. There is an infinity of rain. And the writing: “Cohen stood out in the field. A low ribbon of pink wrapping the late-afternoon horizon. His hands stuffed in his pockets and the blade wiped clean and back in its sheath and his weight on his good leg. Aggie had not said anything to him as he limped out of the trailer and past the ashes of the fire and out into the field but he could feel the man’s eyes on him. Could sense his pleasure in discovering what Cohen was capable of doing. Could feel the strength of the unknown.” That’s the start of ch. 21, and it’s fully representative: sentences that any comp teacher’d scribble frag next to on a research paper but which here, in the capable hands of Michael Farris Smith, create a muscular tonality, and the propulsion, that and and and business that (yes) is everyone’s debt to McCarthy (and others, but he’s the king of it, isn’t he?) just throws the reader over the cliff of each paragraph.

It’s a mesmerizing book. You’ll notice I’ve said almost nothing about Cohen, the central character. It’s not that he’s bad–he’s not. It’s that he’s yet another put-upon haunted man who doesn’t take enough care of himself and tries to help and save everyone else, and that’s fine, but there’s a purity to him that borders on innocence, which can’t work here. You don’t really mind all that much—Cohen’s self is (weirdly) sort of minor: it’s one of those books in which you easily imagine yrself the protagonist, and sort of ignore or overlook the dissimilarities between you and the character. Still: that’s the only drag, and it is, ultimately, pretty small. Otherwise Rivers is just fierce and gorgeous, one big glory.

October 25, 2013

Roberto Bolaño’s WOES OF THE TRUE POLICEMAN

Woes of the True Policeman by Roberto Bolaño

Woes of the True Policeman by Roberto Bolaño

There’s something about the Spanish language that’s just miles more beautiful than English can seem to get ahold of, even after translation. There’s truth in that clichéd sketch, played out in every ‘90s sitcom where the girl’s in bed with a Latino man, asks him to say something to her in Spanish, then swoons as he says “it smells like chicken” or something stupid like that – the truth is, it doesn’t matter what’s being said, the language is fluid, romantic and utterly gorgeous. Thankfully, no ounce of beauty has been lost in translation (or so I assume; if I’m wrong, the original Spanish copy must melt people to the floor) of Roberto Bolaño’s posthumous novel, Woes of the True Policeman.

In comparison to other Latino/Chicano authors (Bolaño’s a native Chilean, although he moved throughout Mexico and Spain), Bolaño creates a category all his own. It’s less magical realism in genre, more revelatory of the pitfalls of current (rather than past) governments and in the case of Woes, much more feminine than most Latino – men care to write. It’s easy to see his influence on moderns like Junot Dìaz, even though his popularity has become cult-like only recently.

It’s one of death’s most ironic gifts – the ability to immortalize and make idols of men that were only known in their respective niches. Since his early death (50) of liver failure (due to a drinking problem throughout life) in 2003, Woes is the third novel to be translated into English, following 2007’s release of The Savage Detectives and 2666 the following year. Really, none of his works were available in English before his death (his first translation, the novella By Night In Chile, didn’t reach English audiences until 2003), meaning all us English-folk couldn’t even appreciate the man until he was already gone. It makes me wonder how much more famous he would have been if the English had been released, say a year after his novellas were published, (the first, The Skating Rink, was released in Spanish in 1993), or, subsequently, if Bolaño would have been so popular with English audiences had there not been the air of tragedy surrounding each of his works.

Whatever the reception would have been, the thing is, Bolaño’s works stand their ground. Woes is no exception. Although less tidy than 2666, another novel published posthumously, Woes offers the same beautiful, poetry-based language and lovely themes as previous works. Even though it’s an “unfinished novel,” it’s complete in the sense of resolution, the tidying-up of character’s lives and stories (interesting part – there’s even some of the same characters from his other works appearing in these stories, which Bolaño seemed to have been working on for the 15 years leading up to his death), yet “unfinished” in the sense that there could be more said, the story could have been five times as thick and not felt drawn-out.

The plot itself (or the main one, there’s side sections and other character stories in here as well) revolves around the disgraced professor Òscar Amalfitano and his daughter, Rosa. Amalfitano is a late-in-life homosexual, a man that loses his true-virginity at the age of 50 to Padilla, a student. Affairs with students are scandal enough, but the same-sex affair is too much for school officials to take. Amalfitano is dismissed, too late to start over in life, too soon to stay home and wait for the grave. It’s self-discovery, re-discovery and it’s best, most beautiful and most heart breaking as we glimpse scenes of Amalfitano and Padilla’s love, his daughter Rosa’s own grasps at normalcy and the pain that follows.

I’d hate to ruin any more. This is a story that’s already too short, and to take anymore away, to unveil more for you before you read the book yourself seems unfair. It’s a novel where each page is its own treasure, it’s own complete story. Unfinished or not, it’s an amazing novel.

October 22, 2013

Donna Tartt’s “The Goldfinch,” based on Carel Fabritius’s “The Goldfinch”

From the beginning, there’s no denying this books debts to Dickens. I’ve never understood a book being called “Dickensian” (do they mean theme? Characters? Certainly not writing…) until picking up Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch. It’s as if the man studied art intensively, then wrote a piece for the digital age. In fact, Tartt shows no pretense about her debt to the author; as she says in an interview with Vogue: “In Dickens there was the risk of real death. There was real blood. I’ve loved him ever since [reading Oliver Twist].”

The Goldfinch ties especially to Great Expectations- written from the point of view of a man, introducing himself as a boy, telling his own tale, no greedy details spared. The boy in Tartt’s story is one Theo Decker, a 13-year old who becomes orphaned in the book’s first chapters, losing his single-parent and adored mother in an explosion inside the Metropolitan Museum of Art. From there, Theo gets adopted into his friend’s home which is run by a high-society mother, and falls irreparably in love with anyone survivor of the museum explosion, a red-headed and free-spirited girl named Pippa, an orphan herself (in case any resemble hadn’t quite gotten to you before).

The Painting of the Story

Here’s the difference: while Dicken’s boy feels his own “greatness” due to a secret benefactor and in part, his own pride, Theo’s sense of pride is nursed by a single painting, pocketed in the smoke and ash and rubble of the explosion, kept tucked away in a pillow case behind his headboard, in storage units for years. That painting is Carel Fabritius’s “The Goldfinch,” held by the art world as a crucial link between the styles of Rembrandt and Vermeer. As Tartt explains through narration in the novel: “That one tiny painting puts Fabritius in the rank of the greatest painters who ever lived. And with The Goldfinch? He performs his miracle.” This is the painting Theo’s mom fauned over moments before her death; this is the painting he couldn’t quite leave amongst the death and the ruins; this is the painting he snatches in a moment, not knowing the effects it will have on his future.

Theo is now lost without his mother, hiding in his apartment waiting for her to come home. He has a father (somewhere) who ran out on the family – social services can’t get in touch. Theo ends up staying with the Barbours, a posh, Park Avenue family, with secrets of their own. He seeks out the two people trapped with him following the explosion, the cute and quirky Pippa and Welty, a partner at an antique and furniture repair shop who never makes it out alive. Theo lives, shielding the painting and just trying to be a normal kid until, lo and behold, the missing father shows up, demanding Theo live with him and his girlfriend in Las Vegas.

Its starts off well out West – Theo makes one of the best friends of his life in Boris, a Russian/Ukranian nomadic creature, alcoholic at 15, drug-dabbler, yet wise beyond his years. Soon, though, it becomes clear Theo’s father is less interested in his son than in the money that may be attached to him and his mother’s inheritance. When business dealings go wrong, Theo’s father dies in a drunk-driving accident, leaving him a full-fledged orphan, and Theo immediately flees back to New York, taking with him a package he believes to contain his painting, thus setting in motion the rest of the novel.

If you’re cursing me under your breath for ruining the story, you can stop now. I’ve described maybe the first 300 pages of the nearly-800 page book. It’s worth its weight – I can’t imagine Tartt putting out this story with even a few less pages. There’s so much intricacy here, with the characters’ lives, struggles and sins, with the storyline and every twist it takes and with the details of the art world’s inner workings. There’s a reason Tartt’s books are published a decade apart from one another – the research alone going into this book must have taken years.

Part mystery and thriller, part drama, it’s less predictable than a mystery, less pulpy than an action piece, more accessible than a classic and more dark and dirt-spilling than a drama, yet it’s an amazing mixture of each. It’s a book that anyone with a casual taste for art, a need for driving action, or the desire for well-crafted work should pick up immediately.

October 18, 2013

Everybody’s Right About Stanley Crouch’s KANSAS CITY LIGHTNING

Kansas City Lightning by Stanley Crouch

Kansas City Lightning by Stanley Crouch

I love how twitter makes one’s world feel echoey: I happen to follow folks in books (obv), and, because of that, the last few months of Twitter have seen, daily, some mention of Stanley Crouch’s Kansas City Lightning, the long-promised first half of his bio of Charlie Parker. Much as I like books, I was excited about this one more for the subject than the author: I didn’t know, as his name kept coming up, how badass Crouch is—I’d seen stuff of his in magazines over the years, but had never dug into anything substantive enough to stake anything like a claim.

Parker was, however, for me, a way-back thing: I hit jazz in my teens and Parker was always the one I wanted to know more about. I never loved his stuff—I’m Rollins mostly, Coltrane too, plus Monk and Davis and Adderly and Bill Evans and Wes Montgomery and and and—but I knew that absolutely everything I ended up liking (even the stuff from good old get-thee-behind-me-elevator-Muzak Stan Getz) and listening to came through Parker. Everything.

And oh good lord, glorious, amazing: Kansas City Lightning is exactly the bio of Charlie Parker I needed. Confession: most of the time when Dwight Garner writes reviews, I read them just clicking along in mimicry of that scene in Wayne’s World in which he’s reviewing the contract— yes…yes…I like what you’ve done here…—and Garner’s review of KCL isn’t much different. His claim—that, if you’re looking for a straightforward bio of Parker, you’ll be left wanting—is 100% on the money. His equal and other claims about the glory of the book, and about Crouch’s language, and his sidestreeting through the events of the first stretch of Parker’s life, are equally deadeyed: this is the book you read so that you can stumble gladly through sentences (mid-paragraph! these aren’t even, like, the ones to make you decide to buy into the game in the first place) like “Though he’d been known to lay about the house, aimless—especially in a month like May, when it often rained—now Charlie started to hit the street, looking for gigs in earnest.” Just relish the deliciousness of that, the (of course) music of the phrasing, how much is taken into consideration.

And the Parker we get in Kansas City Lightning is phenomenal: he’s full-bodied and -blooded, tricky and hard and gifted and searching. You know something of Charlie Parker by the end of it, even if you don’t know some of the more distant or trivial marginalia you’re maybe used to picking up from bios of known folks. What you know, however, more than anything, is the search Parker was on for his sound. Even if you know *nothing* about jazz, Crouch writes with such fervor and muscle—and so startlingly clear about the music itself (the sounds, certain propulsive feels)—that by the end you’ve got more than a passing sense of the arc of Parker’s development, and what he’s going for. It’s hard to even think of another book that tries to so capture its subject: this isn’t mere description; it’s something like an enactment, or a summoning.

It’s a gorgeous book. I pulled my Parker discs out. I’m not there yet—I still head toward the sound I know and love most—but I’m listening for different stuff now, too, trying to trace the traces of Parker Crouch showed.

Jim Henson by Brian Jay Jones

Jim Henson by Brian Jay Jones