Marc Lynch's Blog, page 107

August 9, 2012

How Muslims really think about Islam

I have been fascinated by some of the findings of a massive

new Pew Research Center

global public opinion survey of Muslims in 39 countries in every region of

the world. Pew conducted 38,000 face-to-face interviews in more than 80

languages between 2008 and 2012. What makes The

World's Muslims especially interesting is that it doesn't ask questions

mainly of interest to Americans, such as how Muslims feel about America. Instead,

it asks a series of questions about their own understanding of Islam and their

own religious practices and beliefs. The findings reveal some really

interesting differences across regions, countries, and generations. [[BREAK]]

For

instance, the survey found a really disturbing and widespread belief in most

Arab countries that Shias are not real Muslims. Interestingly, in Iraq (82

percent) and Lebanon (77 percent), countries with Shia majorities but notably

torn by sectarian strife, Sunnis are significantly more likely to say that Shias are Muslims than are Muslims in Arab

countries with small Shia populations. But 53 percent of Egyptians, 50 percent

of Moroccans, 43 percent of Jordanians, and 41 percent of Tunisians -- all

countries with very small Shia populations -- said that Shias are not Muslims. In

Indonesia, 56 percent said they were "just a Muslim" and rejected

identification as "Sunni."

Contrary

to the conventional wisdom that the Middle East is being reshaped by a rising

Islamist generation, Muslims older than 35 are significantly more religious

than those under 35. They are more likely to pray several times a day, to

attend mosque, to read the Quran daily, and to say religion is important in

their lives. And the margins are pretty wide. In Morocco, the older generation

is 19 points more likely to read the Quran daily; in Tunisia, the older

generation is 17 points more likely to attend mosque once a week; in the

Palestinian territories, the older generation is 23 points more likely to pray

several times a day. This generational divide was the widest in the Middle East compared to any other region of the

world.

Another

interesting question had to do with the question of interpretation. Asked

whether there was a single interpretation of Islam or multiple interpretations,

more than 50 percent answered "single" in every African country surveyed, as

did more than 69 percent of every Asian country. Seventy-eight percent of

Egyptians and 76 percent of Jordanians said "single," but no other Arab country

had more than 50 percent.

There's

a lot more in this important

and intriguing report. Anyone interested in how Muslims today think about

their own religion should definitely check it out -- and also look for the

second report focused on political and social issues promised for later this

year.

August 8, 2012

Are you there, Margaret? It’s me, Yemen.

This afternoon, a sizable Washington audience turned out to

watch White House Counterterrorism advisor John Brennan talk about American

policy toward Yemen. Imagine that -- a large Washington audience turning out in

the dead of summer to hear about Yemen! And even better, Brennan began by

responding directly to the criticisms of U.S. policy toward Yemen expressed in

a recent

Atlantic Council-POMED letter to President Obama, which called for moving "beyond

the narrow lens of counterterrorism." (I

made similar criticisms in this space in January.)

Brennan's main goal was to push back against these

criticisms. It is simply wrong, he argued, to claim that the U.S. views Yemen

only from a security and counter-terrorism lens. He laid out the

administration's "comprehensive" strategy for Yemen, including support for the

political transition, humanitarian aid and economic development, and

institutional reforms. He effusively praised President Hadi and his efforts at

institutional reform and political transition, and he emphasized several times

that more

than half of the increased U.S. aid to Yemen went to the political

transition and economic development, not to counterterrorism. Of course at the

end he came to AQAP and mounted a spirited defense of drone strikes as ethical,

legal, and effective, but the speech was structured to show that these efforts

came within a broader political and developmental context. (He also,

thankfully, didn't waste our time blaming Iran for Yemen's problems). [[BREAK]]

Now, many would take issue with his presentation of American

priorities and actions. I wanted to ask questions about the effectiveness of Hadi's

military reforms, and the feelings of exclusion among many activists and

political trends despite the official political dialogue. I don't think many in

the room were convinced by the claims about drone strikes, whether on civilian

casualties, anti-Americanism, or legality. But I do think that it's an

unambiguously good thing that Brennan felt the need and the desire to come out

and publicly articulate the kind of comprehensive political strategy for Yemen for

which many of us have long called. That comprehensive policy might not really

be there yet, but the speech was an important point of entry for all future

debate about Yemen and I for one found it a positive development to have these

concerns addressed so directly.

That's the good. The bad? After Brennan's speech about Yemen,

moderator Margaret Warner asked only a few desultory questions about Yemen. She

then immediately shifted to a series of questions about Syria, which while

interesting had nothing to do with Yemen. And then, to an even longer series of

questions about cyber-security, neither interesting nor to do with Yemen. And

then the controversy over leaks ... ditto. The audience started strong, with

several questions about Yemen and about drones. But soon enough, attention

wandered to Nigeria, to al Qaeda, back to cyber-security, and at its lowest

point to an utterly moronic question about the Muslim Brotherhood's alleged

penetration of the U.S. government. I worried that the Yemeni Twitterati were

going to spontaneously combust from accumulated outrage. Even in an event about

Yemen, John Brennan could barely buy a question about Yemen from his easily

distractible Washington audience. C'mon, DC!

Cruel Summer

Stagnation in Egypt. Grinding insurgency in Syria. Unpunished repression in Bahrain. Frustration in Jordan. Parliamentary crisis in Kuwait. Fizzling protests in Sudan. Humanitarian woes in Yemen. Creeping authoritarianism and renewed bloodshed in Iraq. This summer has not been kind to the Arab uprisings. With the shining exception of Libya, which today celebrates its handover to an elected civilian government, almost every Arab country has sunk back into the bog of political stagnation, frustrated citizens, and in the worst cases grinding violence. Many observers have begun to give up on the hopes for change in the Arab world, and are now dismissing the Arab uprisings as a "fizzle", a mirage, or a false flag for Islamist takeovers.

It is far too soon to accept such a verdict. A frustrating as it has been to live through, this regression to repression is neither surprising nor cause for despair. In my book The Arab Uprising, I warned that there would be such reversals of momentum, unsatisfying political outcomes, activist frustrations, and competitive interventions by powerful states in newly opened political arenas like Syria and Libya. The forces driving the Arab uprisings are deep, structural, and generational. They don't guarantee happy endings, nor do they automatically privilege any one kind of political challenger, whether liberal, sectarian, counter-revolutionary or Islamist. But persistent, creative, and unpredictable challenges to the Arab status quo will continue to manifest in new forms, undermining every effort to restore the authoritarian status quo ante. Don't be fooled by the current sense of stagnation --- but do be worried by the regional fallout of the new struggle for Syria. [[BREAK]]

The reversal of the momentum of the Arab uprisings began within months of their outbreak, of course. Saudi Arabia, after locking down its own home front, helped to prop up friendly monarchies across the region with financial and political aid. Morocco's canny limited constitutional reforms and a burst of mob violence against Jordanian protestors set back reform movements there. Yemen's horrifying descent into violence and failed government and Libya's long military stalemate eroded the non-violent nature of the uprisings. The crushing of Bahrain's protest movement and the sweeping, sectarian repression which followed inflicted perhaps the deepest wound on the Arab uprisings -- not only its unaccountable repression, but the hard-edged sectarianism which had for the first months of the uprisings been suppressed. Politics across the region has been caught ever since between the hopeful efforts of empowered citizens and the determined resistance of entrenched regimes.

This summer has been dominated by a narrative in which protest movements struggle, dictators retrench, the Arab agenda fragments and the Syrian war dominates the news. Arab states seem to some to be back in control, and to others perched back on the tenuous equilibrium of the days before the Arab uprisings --- ongoing political crisis with no signs of serious reform, economic struggles taking an ever harsher toll, and sectarian and ethnic cleavages taking ever deeper hold. Jordan's deeply disappointing new election law has done nothing to restore the legitimacy of the monarchy or to break the trend of tribal dissent and societal fragmentation. Kuwait's political crisis has accelerated dramatically, with the dismissal of Parliament followed and the refusal of its replacement to vote in a new Prime Minister likely leading to yet another new election in a few months. Bahrain simmers with sectarian rage, almost all hope in peaceful reform crushed by a hardline regime more concerned with public relations than with serious political outreach. Countries which largely avoided mobilization during the height of the Arab uprisings, such as Iraq, Lebanon, and Algeria, seem unable to confront their persistent political deadlocks. Saudi Arabia faces a growing, potent protest movement in its Eastern Province which it shows few signs of being willing to accommodate.

Not everything is grim, of course, even within this generally depressing regional environment. Libya has consistently confounded the skeptics. Despite its many remaining problems, most notably the continuing presence of armed militias only tenuously connected to the emerging political order, Libya's successful elections have produced a transition to a democratic, civilian government which few thought possible. Yemen has slightly outperformed (very low) expectations, as its new President has tentatively pushed to restructure the military and assert his authority. Tunisia continues to amaze, despite its crushing economic problems and the emergence of some worrying polarization around religious issues. Even Sudan saw glimmers of popular protest.

But those signs of hope have been overwhelmed by the two largest and most consequential of the Arab arenas: Egypt and Syria. The seating of Mohammed el-Morsi as the elected President of Egypt broke the fever which had kept Egyptians in a state of political frenzy for many long months. The air has largely gone out of Egyptian politics, even before the latest crisis in the Sinai. This isn't necessarily a bad thing. Egypt's constant state of crisis and daily reversals of fortune over the first half of 2012 brought us all close the brink of complete nervous breakdown, and a timeout to regroup was badly needed. Unfortunately, that "strategic pause" seems to have been largely wasted, and the transition to civilian rule which seemed so important seems to be failing to deliver constitutional legitimacy.

Egypt's "pause" should have been an opportunity to get state institutions working again, start dealing with economic disaster, reassure international investors, and rebuild the lost political consensus around the revolution. Instead, it has been frittered away in nervous jockeying between the Muslim Brotherhood and the military. Politics has become ever more polarized between Islamists and their rivals, with virtually any move on either side viewed with suspicion and the worst intentions ascribed (was the Muslim Brotherhood's effort to clean the streets really a nefarious scheme, rather than a smart move to try to actually do something positive?). Revolutionary movements grow every more alienated from the emerging political order, but have done little to build an alternative political movement. The technocratic government which Morsi finally appointed has failed to spark new political energies (though, to be fair, had he appointed an Islamist-dominated government instead the reaction would have been far worse). Indeed, in almost every way the Muslim Brotherhood's decision to seek the Presidency is proving to be the strategic disaster which it appeared at the time --- alienating other political forces without gaining any real power. Egypt may not be in the midst of crisis right now, but it is deep in the political doldrums and looking ever more like the latter-day Mubarak period which the revolution erupted in order to change.

And then, of course, there is Syria. The worst fears about Syria have now largely materialized. With international diplomacy having failed, the conflict has now turned nearly completely into an armed insurgency against a rotting but still capable military regime. The insurgency, fueled by Syrian outrage against Assad's brutality and backed by foreign cash, arms, media and political aid, can sustain itself indefinitely and has little reason to compromise. Assad's regime has little incentive not to fight to the death, and still retains not inconsiderable domestic support and external Russian and Iranian backing. The chances for a political solution were never great, but the unfolding civil war is showing exactly why diplomacy was worth the effort.

The emerging Syrian insurgency is nothing to celebrate. I still believe that Assad is ultimately doomed, as his brutality and political clumsiness has wiped away any hope of restoring legitimate rule over the country. Certainly, the responsibility for political failure and the turn to violence lies with the regime. But the fighting, bloodshed, and spreading sectarianism will leave scars and undermine hopes for political reconciliation in whatever follows Assad. So will the proliferation of weaponry into the hands of armed groups which still lack any real leadership or cohesion, to say nothing of a clear political agenda. The role of al-Qaeda may be exaggerated in some of the reporting, but jihadist fighters are now clearly present and playing an active role, and they will not be easily dimissed when the fighting ends.

The effects are not only internal to Syria, of course. Like Iraq in the previous decade, Syria is increasingly the battleground for regional proxy war, the breeding ground for regional sectarianism and jihadist extremism, and a potent cautionary tale for autocrats seeking to frighten their discontented populations against further revolts. The Syrian war overshadows almost all other issues in today's Arab media, driving out many of the political and social and intellectual issues brought to the fore by the early days of the Arab uprisings. The idea that things would be better in Syria now had the United States intervened militarily is a fanciful one -- more likely, such an intervention would only have destroyed hopes for a political solution more quickly, accelerated the violence, and now found American forces caught in the quagmire. The Obama administration has been wise to resist pressures to intervene militarily in Syria, and I fear that its emerging moves to support the insurgency, which it likely sees as now politically necessary even if unlikely to actually produce desirable outcomes, will come back to haunt it in the coming years. But the reality is that there are now no good options.

This is a grim regional picture -- and I haven't even mentioned the beating drums for war against Iran or the complete absence of an Israeli-Palestinian peace process. It's been a cruel summer. But it should not be taken as reason to despair or to question either the reality or the value of the Arab uprisings. The core structural driving force behind the Arab uprisings remains the generational rise of a new public sphere of frustrated citizens in a radically new information environment. There was never going to be a straight line from popular uprising to liberal democracy in these countries. Islamists were always going to perform well in elections, autocrats were always going to defend their power, and the beneficiaries of the status quo were always going to resist change. But autocrats are on the defensive, Islamists are internally divided and struggling with the demands of power, and expectations of democratic participation and open, contentious public life taking ever deeper root. Taking a longer view allows us to see the reality of how much has changed in the texture of Arab politics, and perhaps despair less at setbacks and reversals.

In The Arab Uprising I wrote that we were only seeing the early manifestations of a generational change in Arab politics, and that long view remains important. That's why I remain cautiously optimistic on Egypt and on many of the other Arab countries which currently seem so stagnant. But I do continue to fear the regional effects of Syria's relentless shift from political uprising to externally-backed armed insurgency and sectarian rhetoric. As in the 1950s, the region's politics are increasingly shaped by this struggle for Syria, in which, as Patrick Seale famously put it, "each [regional power] sought to control it or, failing that, to deny its control to others." This regional context may not be all-determinative, but it can not help but affect the domestic struggles across the region. Can the domestic struggles for political change gain traction in this environment? Can regional media such as al-Jazeera now obsessed with Syrian war again unify these local struggles into a common demand for Arab change as they did in the early days of 2011? Can protest movements unify around demands for change and resist the insidious spread of sectarian and ethnic conflicts? Those will be the defining questions for the next stage of the unfolding Arab transformations.

July 22, 2012

Preparing for Assad's Exit

Last week's stunning assassination of several key Syrian security officials, the sudden spread of serious fighting into Damascus and Aleppo, and the Russian-Chinese veto of a Chapter VII resolution at the UN Security Council have ushered in a new phase in the Syrian crisis. Five months ago, I wrote a policy report for the Center for a New American Security

warning against U.S. military intervention or arming the opposition,

and proposing a series of non-military steps which might help bring

about a political transition. In April, I argued in a Congressional hearing for giving the Annan Plan a chance to work.

In an essay published today on CNN.com, I suggest that diplomatic efforts to resolve the crisis have failed -- but that this is no cause for celebration. Annan's efforts, supported by the U.S., attempted to find some path to a "soft landing" which could avoid Syria's descent into sectarian civil war, insurgency and potential state collapse. For his pains, Annan was often treated as an enemy by Syrian opposition supporters anxious for external military intervention, outraged by the daily bloodshed or distrustful of any regime promises. But the likely course of the struggle to come demonstrates painfully why this was an effort worth making.

Today, we face the grim reality that the prospects for a negotiated transition have largely ended and Syria now likely faces a long, grinding insurgency with few foundations for a viable post-Assad scenario. Sadly, such an outcome of long-term violence would be acceptable to many whose primary interest is weakening Iran rather than protecting civilians or building a more democratic Syria. At this point, it is vital to prepare for an end which won't come soon, but when it happens will likely be sudden and surprising. [[BREAK]]

The CNN essay was meant to appear on Friday morning, but was pushed back due to the horrible Colorado shooting tragedy; in the interim, several very good pieces have appeared making similar points, including this one by Fred Kaplan and this one by Martin Chulov. In the CNN article, I argue that Assad's end really is nigh, as has been clear for some time, but that the way that his regime ends matters immensely for Syria's short to medium range future:

The assassinations were more of an inflection than a turning

point.

Diplomatically isolated, financially strapped and increasingly constrained by a wide range of international sanctions, Assad’s

regime has been left with little room to maneuver. It resorts to indiscriminate

military force and uses shabiha gangs

and propaganda to inflict terror.

The government’s brutal violence against peaceful protestors

and innocent civilians has been manifestly self-defeating. Assad has failed to kill his way to victory.

Day by day, through accumulating mistakes, the regime is losing legitimacy and

control of Syria and its people.

Nonetheless, it’s premature to think the end is close. The

opposition’s progress, reportedly with increasing external funding and

training, has put greater pressure on Assad’s forces. But the opposition’s

military success has exacerbated the fears of retribution attacks and a reign

of chaos should the regime crumble...

Now, even if Assad’s regime collapses, violence may prove difficult to contain given that the

country is deeply polarized and awash in weapons. Assad’s end could pave the

way for an even more intense civil war. Making matters worse, the continuing fragmentation among the Syrian

opposition groups raises deep fears about their ability to unite themselves or

to establish authority. Few foundations exist for an inclusive and stable

post-Assad political order.

This violent struggle ripping Syria apart is precisely the scenario which the U.N. political track had hoped to avoid, and which Assad's brutality and the escalating insurgency has summoned forth. The U.N.'s efforts never had a great chance of success, of course, but they were worth supporting given the alternatives which could so easily be foreseen and which are now manifesting.

At this point, unfortunately, it is difficult to see any real prospect for the "soft landing" envisioned in those efforts. Diplomatic efforts, such as the Arab League's offer of a safe exit for Assad if he leaves immediately, should still be tried. Perhaps the regime's newfound sense of vulnerability and the opposition's sobering recognition of the challenges it faces after the regime's fall might even get the ideas a listen.

But even if Assad and parts of the opposition can somehow be sobered by the inevitable end, the fragmentation, violence and anger are now likely too great to overcome. Does Assad really see that he's losing, and does he really believe that there is any safe passage out at this point (and could anyone truly stomach that)? And could a divided opposition smelling victory and suspiciously eyeing competitors for future power really settle for a pragmatic but unpopular deal... or trust any parts of Assad's regime to honor it? The These are the challenges with which Kofi Annan has tried and failed to grapple, and which will bedevil all other such efforts.

It has never been more clear that the Obama administration was right to reject calls for American military intervention, and should continue to do so. The events of the last week show that those who believed that only American military action could put serious pressure on Assad were wrong. And the likely downside of direct U.S. military involvement is as potent as ever. The new talking point that an earlier American intervention would have quickly ended the fighting is utterly divorced from Syrian reality. American bombs were never likely to quickly end the conflict, and the open entry of the U.S. into the fray (particularly without U.N. authorization) would likely radically transform the dynamics of the conflict for the worse both inside of Syria and at the regional and global levels. And most Americans, who have not forgotten the experience of Iraq, wisely reject the enthusiasm of the op-ed pages for deeper American involvement. Military intervention by the U.S. has not been and still is not the answer, and the Obama administration deserves great credit for rejecting the drumbeat from the armchair hawks.

Nor should the U.S. be joining the dangerous game of arming the insurgency, which seems to be getting plenty of weapons from other sources. All of the risks of the proliferation of weapons into a fragmented insurgency of uncertain identity and aspirations, so blithely dismissed by the op-ed hawks, remain as intense as ever. There are still vanishingly few, if any, historical examples of such a strategy actually leading to a rapid resolution of a civil conflict, and all too many examples of it making conflicts longer and bloodier. Nor is it likely that providing weapons will provide the U.S. with great influence over the groups they are. I see no reason to believe that armed groups will stay bought, or stay loyal, just because they were given weapons, or that the U.S. would be able to credibly threaten to cut off the flow of weapons if groups deemed essential to the battle used them in undesirable ways. As a general rule of thumb if you really think that a group might join al-Qaeda if you don't give them guns, you'd best not give them guns. At this point, the flow of weapons may be as unstoppable as the descent into protracted insurgency and civil war, but that doesn't mean that the U.S. should heedlessly throw more gasoline on the fire. At the most, it should continue its efforts to help shape some form of coherent political and strategic control over those newly armed groups.

Instead, the U.S. should be focusing on supporting the Syrian opposition politically, mitigating the worst effects of the civil war and insurgency, pushing to bring Syrian war criminals to justice, and maintaining its pressure on Assad through sanctions and diplomatic isolation. Several articles published after I wrote the CNN piece have begun to outline some current U.S. thinking and activities in this regard. Above all it needs to work with the Syrian opposition to prepare it for the prospect of unifying the divided, fragmented, and anarchic Syria which it will inherit when Assad falls. That should include doing everything it can to convince the armed opposition of the urgent need to police its own ranks and thinking constantly about how it will need to relate to currently unfriendly communities in a future Syria.

I'm hoping to write more soon about such political efforts, and about the UN mission, and about the regional politics of Syria. But those are beyond the scope of today's short CNN article taking stock of this inflection point in Syria's ongoing conflict.

July 8, 2012

Islamists in a Changing Middle East

The election of the Muslim Brotherhood's Mohammed el-Morsi as President

of Egypt, following the electoral victory of Tunisia's Ennahda Party, has sharpened the world's focus on the role of Islamist movements in a

rapidly changing Middle East. The turn from an "Arab Spring" to an "Islamist Summer (and/or Winter)", as pessimists warn gloomily that the overthrowing of dictators is only

empowering a new generation of religious fanatics, has become the stuff of cliche. But the concern over rising Islamist political power in both the West and in countries such as Egypt is very real. Who are these movements? What do they want? And

how will they shape -- and be shaped by -- the region's new politics?

I am thrilled to announce today's publication of a new ebook, Islamists in a Changing Middle East. This collection of dozens of essays originally published on ForeignPolicy.com offers deep insights into the evolution of these Islamist movements. They offer

accessible, deeply informed analysis by top experts, which can help to correct many of the

misconceptions about such movements while also drawing attention to very real

dangers. These essays were written in real time, in response to

particular circumstances and challenges, and have been only lightly edited and

updated for this volume in order to retain the urgency and passion with which

they were written. The essays offer snapshots of a political moment, informed

by deep experience and long study of these movements and the countries within

which they operate. They have enduring value. [[BREAK]]

The success of Islamist movements in transitional elections in the Arab world should have come as no surprise. Most non-Islamist political parties across the region have long since been crushed, co-opted, or calcified into political irrelevance. Meanwhile, Islamist movements managed for the most part to avoid the taint of association with the old regimes, and have long been the

best-organized and most popular political movements in most Arab countries. They have also spent decades systematically reshaping the public culture of the region at all levels of society. Islamists were thus naturally well positioned

to take advantage of the political openings in many Arab states that followed the

great protest wave of 2011. No meaningful transition towards more democratic systems could have avoided the reality of significant Islamist constituencies and organizations.

But that does not mean that such Islamist movements are all powerful. One point which

quickly emerges from the essays in this volume is simply how disorienting the newly open

political vistas have been for Islamists, and how easily their advantages can evaporate. The Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, for instance, has gone from a cautious movement to a risk-taking power broker which seems intent on grabbing as much power as possible before its window closes and has succeeded in alienating most other political forces along the way. It saw its sweeping Parliamentary victory wiped away with the stroke of a judicial pen and the powers of its narrowly won Presidency constrained by decree. A President unable to even appoint his own Minister of Defense is unlikely to succeed at imposing unpopular sharia laws. Its rise has so frightened and angered its political rivals that some avowed liberals and revolutionaries have rallied to the side of the long-hated SCAF. In short, the Brotherhood has struggled to deal with its own

ascendance, as it suffers internal fissures and unprecedented public scrutiny. Not even the Brotherhood's leadership seems quite certain how their new opportunities will ultimately affect their

behavior, their ideology, or their internal organization.

Other Islamist parties have similarly struggled to master the new political terrain. At one point in the summer of 2011, a leader of the

Egyptian Salafi party, al-Nour, told me that if all went well his party might

win four or five seats; it won over 100. Since that success, the performance of its Parliamentarians has proven underwhelming, leading to serious rethinking in the salafi ranks. Tunisia's Ennahda won the founding elections and initially managed to hold together a broad national consensus, but has struggled to keep its balance in the face of impatient salafis, disgruntled revolutionaries, and anxious secularists. Libya's Islamists look set to do poorly at the polls. Morocco's Islamist PJD may have taken the Presidency, but only by accepting the King's political terms. Jordan's Muslim Brotherhood is planning to boycott upcoming Parliamentary elections. Kuwait's Islamists have been rocked by the Emir's dissolution of Parliament.

The new political landscape is rapidly exposing long-standing divisions among the Islamists themselves. The Muslim Brotherhood is not

al Qaeda, the Global Muslim Brotherhood Organization exercises little control

over its national branches, and Salafi and Muslim Brotherhood parties are

competing furiously for votes and for Islamist credibility. The

participation of Salafi parties in democratic politics is even more novel. While

some Salafi parties had entered the political fray in the Gulf prior to the

Arab uprisings, there had rarely been anything quite like the electoral rise of

Egypt's al-Nour Party. Salafi movements had for decades rejected democracy on

principle, as apostasy which replaced the rule of God with the rule of man. The

enthusiasm with which these movements now entered the electoral fray suggests

that they may yet wear their ideology lightly. But the harsh rhetoric and radical views of many of these

inexperienced Salafi politicians shocked local and foreign audiences alike. Islamist political parties have to calculate

their strategy in uncertain legal and political environments, weigh both

domestic and international calculations, and decide how to reconcile their

ideals with the demands of practical politics.

The exercise of

power, in short, poses significant challenges to all such movements. The

authoritarian realities of these regimes created something of a safety net for

these political Islamists. Imposing Sharia law was never before an option, but now even pragmatic

leaderships must explain to a more radical rank and file why they do not

try. Since there was never any real possibility that they

could come to power through the ballot box, they were rarely forced to choose

between their Islamist ideology and their democratic commitments. They could

posture as democratic reformists, highlighting corruption or repression,

without having to signal whether they would use a position of power to impose

their vision of Islamic morality on others. The Arab uprisings have removed

that buffer, forcing many of these movements to confront for the first time the

opportunity to actually rule. How, one wonders, will Muslim Brothers or Salafis in

leading roles in

an Egyptian government deal with the need to take IMF or World Bank

loans to

rescue the economy, when the Islamic sharia forbids the charging or

paying of

interest? How will they deal with the need to coordinate policies toward

Gaza

with Israel? It has already been intriguing to watch Egypt's new President work to reassure the United States that his country would continue to honor its treaty commitments, including those to Israel.

These deep divisions among competing Islamist trends should ease fears of the rise of a unified Islamic bloc across the

Middle East and North Africa, however. Islamists are deeply divided amongst

themselves about political strategy and how to wield political authority. Some

hope to immediately impose Islamic cultural policies, while others prefer to focus

on economic development. Participation in politics is already changing

these movements, strengthening some factions and weakening others. What is

more, their very success carries the seeds of a backlash -- both from

frightened liberals and from Islamist purists disgusted by the compromises

necessary to political power, as well as from those upset with their failure to solve likely intractable problems. Non-Islamist movements may catch up with the Islamists in forming political parties and harness the substantial non-Islamist electorate. And finally, the experience of the 1950s and

1960s bears recalling, when pan-Arabist dominated states such as Iraq, Syria,

and Egypt proved bitter rivals rather than easy allies under the banner of

Gamal Abed Nasser.

For all these challenges to the Islamists themselves, there

are also good reasons for secularists or liberals to worry about what such movements

might do with state power. It is extremely significant that Islamists of almost all stripes have now decisively opted to accept the

legitimacy of the democratic game. It is far better to have such groups inside

the democratic process than to have them as marginalized outsiders -- as long

as they are willing to respect democratic rules, public freedoms, and the

toleration of others. But at the same time, they should be judged by their behavior. Even where these movements have proven to be able and committed democrats, they are most certainly not liberals and will not become so. The same democracy advocates who once defended

the Islamists against regime repression now should legitimately hold them

accountable for their own actions --- and insist that they respect fundamental human rights, tolerate competing views and identities, and refrain from imposing their preferences on the unwilling.

All of this marks a

dramatic change since the bleak days following September 11, 2001 and the dark days of jihad and civil war in Iraq, when

extremist views and violent rhetoric dominated views of Islamism. The appeal of

violent jihadism has clearly faded, at least for now, and few Islamists still

openly reject the principle of democracy. Al Qaeda has struggled to

adapt to the Arab uprisings, with the American killing of Osama bin Laden marking

at least a symbolic ending to a decade dominated by a so-called "War on

Terror." But it would be wrong to assume that this will necessarily last.

Indeed, one could easily imagine the appeal of jihadism returning with a

vengeance should democratic politics fail or should Islamist politicians

compromise so much that they alienate purists in their ranks. And, of course,

state collapse and protracted civil strife create new opportunities for jihadists to regroup. Syria, in particular, already seems en route to becoming a major new rallying call for salafi-jihadists, a new front for jihad to replace the lost opportunities of Iraq.

The essays

collected in Islamists in a Changing Middle East capture the complexity and the uncertainty of the new

Islamism in the rapidly transforming Middle East. They offer no easy answers and no unified perspective. Instead,

they present deeply informed analysis of these movements as they have

confronted new challenges and seized new opportunities. They show the Islamist

movements in all their similarities and differences, their struggles and their

advances, and their troubled engagement with a rapidly changing Middle East. They offer well-informed, timely and highly readable analysis of Islamist movements from some really top-notch experts. Get it as a PDF or as a Kindle eBook today!

Libya's Election (Editor's Reader)

The Middle East Channel Editors Reader #6

Votes are being counted in yesterday's historic election to select a temporary 200 member General National Congress in Libya. The voting process itself was a resounding success, which defied the many skeptics who predicted violence, boycotts, or worse. Reports from across Libya highlighted an enormous, infectious enthusiasm for the vote which belied the sensationalist press reporting and commentary about a collapsing, violent Libya on the brink of chaos. Voter registration and turnout were remarkably high, and there have been few reports of either violence or attempted fraud. With luck, Libya's electoral commission will avoid the self-inflicted wounds of, say, Egypt and quickly announce credible results which will be accepted as such by all of the major contestants.

Few observers have any illusions that the elections themselves will solve any of Libya's many problems, from economic woes to the absence of effective state institutions to the continuing role of armed militias. The absence of any prior history of such elections makes it almost impossible to predict the likely winners. And the experience of countless transitional elections elsewhere warns against exaggerated hopes for a smooth political ride to come. There will be fierce struggles for power and positions as a government is formed, existential decisions to be made by the election's losers about whether and how to contest their defeat, and looming battles about core questions of the country's identity and direction. But the high participation in and smooth progress of the elections will help to ground those coming political battles within a legitimate, democratic and hopefully resilient institutional framework.

In short, July 7 was only one day in Libya. But it was a good day.

Here are some of my recommendations for things to read to help make sense of the election in Libya and the struggles to come.

Sandstorm: Libya in the Time of Revolution, by Lindsey Hilsum. This is the best of the small new crop of reported books about the revolution, war, and their aftermath in Libya. Hilsum gives a well-grounded, accessible account of the Libyan struggle from the ground level, with enough historical background to contextualize the events. She largely avoids editorializing, and has no evident ideological axe to grind over an intervention which sparked more than its share of eye-rolling polemics. Academic histories of the war will come, but for now I thoroughly enjoyed this journalist's account.

Previewing Libya's Elections (Project on Middle East Democracy, July 2012). A very useful backgrounder to the rules, the contenders, the stakes and the issues to watch. POMED also offers useful links to other resources, including an IFES election backgrounder.

Libya's Islamists Unpacked, by Omar Ashour (Brookings Doha, May 2012). Ashour is one of the best informed and well-connected researchers working on Islamist trends in Libya. This policy brief effectively describes and evaluates the major Islamist groups in the emerging landscape. For earlier insights from Ashour on the Middle East Channel, see "Libya's Muslim Brotherhood Faces the Future" (March 2012) and "Ex-Jihadists in the New Libya" (August 2011). Also see Mary Fitzgerald, "A Current of Faith," in Foreign Policy for more on these Islamist movements.

The Libyan Rorschach, by Sean Kane (Middle East Channel, May 2012). Panoramic account of the evolving Libya by an American analyst which delves into the competing narratives and trends across a divided but emerging nation. Also see Kane's "Federalism and Fragmentation in Libya? Not so Fast" (March 2012), "Throw out the playbook for Libya's elections" (January 2012), and "Libya's Constitutional balancing act" (December 2011). For more from Foreign Policy on this confused national tapestry, see Alison Pargeter's new "Qaddafi Lives".

Militia Politics in Libya's National Elections, by Jacob Mundy (Middle East Channel, July 2012). The continuing role of armed groups -- militias to their critics, freedom fighters to their defenders -- is by most accounts the single greatest challenge to the consolidation of a legitimate Libyan political order. Mundy's reported analysis points out some of the real, and less real, dimensions of that important challenge. For more on the challenge to Libya's elections from militias -- which does not end on election day -- see this Crisis Group brief.

Finally, on the ongoing showdown between Libya and the International Criminal Court, follow Mark Kersten at Justice in Conflict -- his summary of the outcome of the clash over the four arrested ICC workers here, and scroll down for much more thoughtful commentary.

*******

Recent editions of the Middle East Channel Editor's Reader:

#5: Sudan's Protests (June 28, 2012); #4 Egyptian judges and salafis, Libyan money, and more (June 11); #3 Three Books and a Special Issue (June 5)

June 28, 2012

Sudan's Protests

The Middle East Channel Editor's Reader, #5

Last week's outbreak

of the largest wave of popular protests in Sudan in nearly two decades has

opened up the possibility for change in one of the cruelest regimes in the

Middle East and Africa. Few regimes are

more deserving of popular challenge than that of Omar Bashir, who should long

since have been in custody in the Hague answering for his indictment by the

International Criminal Court for crimes against humanity in Darfur.

The "Arab spring" is hardly needed to account for the

protests in Khartoum, which has a long history of popular uprisings, but it certainly frames the perception and politics of what is unfolding. The current wave of protests were triggered

by austerity measures, including cuts to food subsidies, in a tenuous political arena framed by the tensions

surrounding the new South Sudan.

Activists, especially students who had been trying to keep protests

alive for over a year and a half, have moved creatively to embrace the

online communications and organizational tactics made familiar by the Arab uprisings

of the last year and a half. The tortuous path of popular struggles in Syria,

Yemen and so many other Arab countries following early waves of enthusiasm

should be a cautionary tale about overly high expectations. But Sudan's rising protest movement in the

face of a growing crackdown clearly merits the world's attention.[[BREAK]]

Foreign Policy

has been on top of this rapidly developing story. For the latest coverage and analysis, see:

Amir Ahmed Nasr, aka

@Sudanese_Thinker, Sudan

Needs a Revolution

Christian Caryl, The

Sudanese Stand Up

Sigurd Thorsen, Sandstorm

Friday

And don't miss this

outstanding slideshow of photos from the Sudanese protests.

For background beyond Foreign

Policy, The Middle East Channel

recommends:

Khaled Medani, Understanding

the Prospects and Challenges for Another Popular Intifada in Sudan

(Jadaliyya) and Strife

and Seccession in Sudan (Journal of Democracy) --- insights from one of the

best scholarly Sudan experts

Asmaa el-Husseini, Sudan's Imminent Uprising

(Al-Ahram Weekly)

Abdelwahhab El-Affendi, Revolutionary

anatomy: the lessons of the Sudanese revolutions of October 1964 and April 1985

(Contemporary Arab Affairs) --- essential background on Sudan's history of

popular upheaval

Gerard Prunier, Darfur:

A 21st Century Genocide (Cornell University Press) ---remains an

authoritative reference on that internal conflict

The Economist, "The

Spectre of Sudan's Popular Uprisings" - prescient short note from February

2011

Top Twitter feeds for the Sudan protests -- prepared by Carol Jean Gallo for UN Dispatch

We will update with useful articles as they cross my desk.

- Marc Lynch, June

26, 2012

June 26, 2012

Egypt's Second Chance

The Arab world has never seen anything quite like Sunday's excruciatingly delayed announcement that the Muslim Brotherhood's Mohammed el-Morsi had

won Egypt's Presidential election. The enormous outburst of enthusiasm in Tahrir after Morsi's victory was announced -- and the rapid resurgence of Egypt's stock exchange -- suggests how narrowly Egypt escaped the complete collapse of its political process. This isn't the time for silly debates about "who lost Egypt," since against all odds Egypt isn't lost. On the contrary, it has just very, very narrowly avoided complete disaster --- and for all the problems which Morsi's victory poses to Egypt and to the international community, it at least gives Egypt another chance at a successful political transition which only a few days ago seemed completely lost.

Outside of the Brotherhood itself, this popular response was more a celebration of Shafik's defeat than of Morsi's victory. The signs leading up to the announcement strongly suggested that the SCAF had carried out a "soft coup" aborting its promised transition to civilian rule. The dissolution of Parliament and the issuing of the controversial constitutional annex, along with the long delay in releasing the results and the rampaging rumors of the deployment of military forces and warnings of Brotherhood intrigues, all pointed to the announcement of a Shafik victory which hadn't been earned at the ballot box.

It's actually quite astounding in some ways that the SCAF didn't -- or couldn't -- rig the election in Shafik's favor. I agree with those who suggested that the Brotherhood likely saved

Morsi's victory by rapidly releasing results from every precinct --

results which proved to be extremely accurate. This masterstroke of

Calvinball established the narrative that Morsi had won and that Shafik

could only be named the victor through fraud, and it also dramatically

reduced the room for maneuver for anyone hoping to carry out the cruder

forms of electoral fraud. A Shafik victory widely seen as fraudulent would have ended any hope of a

political transition, and would have likely meant a return to severe

political and social turbulence.

International pressure along with intense behind the scenes political talks in the days following the election also almost certainly contributed to the SCAF's decision. Support for the democratic process, and not any particular support for the Muslim Brotherhood, is why the United States and other outside actors pushed the SCAF so hard publicly and privately to not pull the Shafik trigger. Quiet American diplomacy, which combined continued efforts to maintain a positive relationship with the SCAF with a stern warning that it must complete the promised transition to civilian rule, appears to have played a key role. And the Brotherhood almost certainly gave the SCAF a number of guarantees in the quiet negotiations which reassured the nervous military -- while, of course, infuriating revolutionaries ever attuned to the Brothers selling them out. While such a negotiated outcome might not seem especially democratic, it's hard to see how it could really have gone differently given the intense institutional uncertainty, pervasive doubts and fears, and the reality of the balance of power.

It's important to not overstate the extent of Morsi's victory, which neither proved overwhelming electorally nor put the Muslim Brotherhood in a dominant position in Egyptian politics. The MB's decision to field a Presidential candidate was only very partially vindicated by his victory, and is still likely to create more problems than opportunities for the traditionally secretive and cautious movement. Many revolutionary political forces already had a bill of complaints

against the Islamist movement (supporting the March 2011 constitutional

amendments, not joining various Tahrir protests, trying to dominate the

Constitutional assembly, having the nerve to win Parliamentary

elections, and so forth). Breaking their very public promise to not run a Presidential candidate drove a sharp wedge between the Brotherhood and other political forces because it seemed to confirm a prevailing narrative about their hunger for power and noncredible commitments.

Morsi and the Brotherhood clearly did pay a political price for this behavior. Morsi slipped into the run-off with a quarter of the vote only because non-Islamist revolutionary forces failed to unite around a single candidate and instead split 50% of the vote three ways. Nor was the performance in the runoff especially impressive, as Morsi managed only 51% despite running against a caricature of a figurehead of the

old regime. There were almost the same number of voided ballots as the margin of

victory. Morsi is going to have to quickly take significant moves to reach out to those political forces in the next few days if he has any hope of bridging a polarized polity. He has already begun these efforts, meeting with the martyrs of the revolution (including Khaled Said's mother) and signaling that he would appoint Christians, women, independents and technocrats to key government positions. If he's smart, he will prioritize rapid moves to create jobs, stabilize the economy, reform government ministries, and restore a sense of security and political stability. It isn't going to be easy to overcome the deep, raw wounds which have been opened between Egypt's political forces, and little which has happened over the last year is reassuring... but at least there's a chance to try.

Finally, it remains deeply unclear how much power Morsi will

have. The constitutional annex announced in the midst of the Presidential vote sharply

limits the power of the Presidency. Morsi isn't commander in chief and can't declare war, and won't be able to appoint his own people to key government ministries. If he can't even appoint his own Minister of the Interior or Minister of Defense, he isn't exactly likely to be rushing towards imposing sharia law. There's still no Parliament, with the SCAF absurdly granting legislative power to itself -- will Morsi approve legislation by "liking" it on the SCAF Facebook page?

But he will not necessarily accept those

limits. The truth is, this is still Calvinball. No rules are set in stone, everything is up for negotiation, and there are no guarantees about anything. I don't believe that the SCAF is firmly in control or has been manipulating events behind the scenes, or that the MB has accepted a permanently subordinate position. Nor do I think that the current constitutional annex will necessarily stand, or that the courts will take consistent positions, or that the Parliament will remain dissolved. Morsi will struggle with suspicious political forces, the absence of a Parliament, a recalcitrant SCAF, hostile state institutions keen to frustrate any changes, an economy still in something like a death spiral, and a suspicious outside world. The ferocious rumor mill of Egypt's wildly contentious press will continue to exacerbate every political issue into a crisis, and attempt to string together some coherent story out of the limited information available to them.

In other words --- Egyptian politics. It's not as good as many had hoped for by this stage. But it's a lot better than it looked a few days ago. And that's something. So save the inappropriate comparisons between Cairo 2012 and Tehran 1979, and put those "who lost Egypt" talking points on hold. This is only the beginning of a long, intense political struggle to come -- but at least there's still a political process with which to engage.

June 22, 2012

Mini 6.22

June 18, 2012

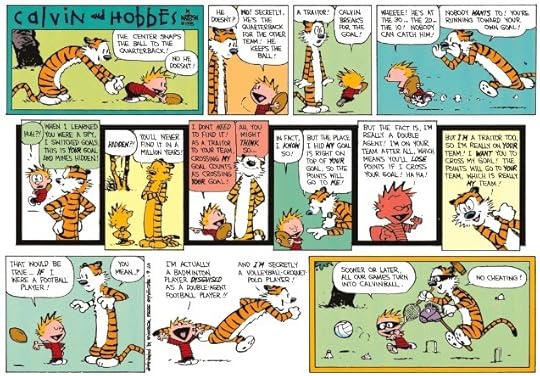

Calvinball in Cairo

The best guide to the chaos of Egyptian politics is Hobbes. No, not

Thomas Hobbes --- Calvin and Hobbes. Analysts have been arguing since

the revolution over whether to call what followed a transition to

democracy, a soft coup, an uprising, or something else entirely. But

over the last week it's become clear that Egyptians are in fact caught up in one great game

of Calvinball.

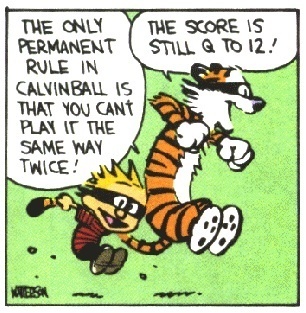

For those who don't remember Bill Watterson's game theory masterpiece, Calvinball

is a game defined by the absence of rules -- or, rather, that the rules

are made up as they go along. Calvinball sometimes resembles

recognizable games such as football, but is quickly revealed to be

something else entirely. The rules change in mid-play, as do the goals

("When I learned you were a spy, I switched goals. This is your goal and mine's hidden."), the identities of the players ("I'm actually a badminton player disguised as a double-agent football player!") and the nature of the competition ("I want you to cross my goal. The points will go to your team, which is really my

team!"). The only permanent rule is that the game is never played the

same way twice. Is there any better analogy for Egypt's current state of

play?[[BREAK]]

As in Calvinball, the one constant in Cairo's trainwreck of a transition seems to be the constantly changing rules and absolute institutional uncertainty. Prior to the first round of the Presidential election, several key candidates were disqualified on questionable grounds. Efforts to form a Constitutional Assembly before the Presidential election failed, then succeeded, then failed again. Just before the Presidential election, the Supreme Constitutional Court declared the Parliamentary election law unconstitutional, leading to the dissolution of Egypt's first freely elected Parliament. But the Parliament's speaker rejected the ruling, declaring that he would convene a session anyway.

Then, in the midst of the Presidential election, the SCAF unilaterally issued a constitutional amendment annex greatly expanding its own power and limiting that of the incoming President. Whoever wins, the powers of the Presidency have been radically

constrained, while the SCAF has granted itself legislative power (!) and

more or less total immunity from any civilian oversight. This rather strips the promised transfer of power to civilian rule of its significance, while falling far short of establishing a legitimate, consensus set of rules of the road for Egyptian politics. Small wonder everyone quickly labeled it a coup, soft or otherwise. But then, in a defensive press conference today, SCAF representatives defended their democratic commitments with explanations which seemed to contradict the text of their own constitutional amendment annex.

Then, just as the fix seemed in for the old regime's candidate, Ahmed Shafik, the campaign of his Muslim Brotherhood rival Mohammed el-Morsi claimed a smashing victory based on the tallies of its observers in all Egyptian voting booths. But the Shafik campaign disagrees, and official results may not be announced until Thursday, leaving plenty of time for this to change. The interpretation of the constitutional annex -- by the SCAF, by the judiciary, and by all political trends -- will likely change depending on the outcome of the election. In the next few days, a Parliament might or might not seat itself, the new President might or might not be empowered, a new Constitutional Assembly might or might not be formed. And tomorrow, another of Egypt's endlessly inventive judges may declare the Muslim Brotherhood itself illegal.

But here's the thing -- Calvin doesn't always win at Calvinball. Players succeed by responding quickly and creatively to the constantly changing conditions. Hobbes plays brilliantly, as one might expect. But even Rosalyn, the dread babysitter, figures out the rules lurking within the absence of rules and has Calvin running from water balloons before he knows it.

[image error]

In other words, Watterson's game theoretic analysis suggests that

Calvinball's absence of rules does not automatically bestow victory on

Calvin. The game is going to continue for a long time, at least until the players finally settle on some more stable rules which command general legitimacy. Perhaps the SCAF might not automatically dominate SCAFball?

And with that, it's back to scanning all available news sources for the latest twists and turns in Egypt's high stakes game of Calvinball. Who says game theory isn't relevant to real world politics?

Note: all images courtesy of dedicated Calvin and Hobbes fans, and all rights reserved to the legendary Bill Watterson.

Marc Lynch's Blog

- Marc Lynch's profile

- 21 followers