Rjurik Davidson's Blog, page 7

June 13, 2014

New Interview at Rising Shadow

There’s a new interview with me up at Rising Shadow. Here’s a snippet.

We�’re all flawed, even if we don’�t always admit it. We also all face ambiguous choices all the time. In one simple example, we buy goods made in third-world countries all the time. The workers who make these good often work in dehumanising conditions. We survive these decisions, mostly, by repressing that reality. That act of repression interests me. Each of my characters are put in difficult situations where they have to make choices between two different evils. To do so, they have to repress or self-justify. Still, I think the book tries to deal with them sensitively, and we know – in the end – who is mostly good and who is mostly bad.

June 12, 2014

Fantasy and Violence

Over at Tor.com, I wrote a piece called ‘On Fantasy and Violence‘, in which I talk about Game of Thrones a bit too.

June 7, 2014

Interview and Giveaway on Adventures in Sci-fi Publishing

There’s a new interview and a giveway over here.

May 31, 2014

The Mystery of a Hansom Cab

The Mystery of a Hansom Cab by Fergus Hume

The Mystery of a Hansom Cab by Fergus Hume

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

A body turns up in St Kilda, murdered in a Hansom cab. Leaving aside the quaint social mores of the time, expressed by characters in the book, and in the style and form of the the book itself, this is a terrifically fun little novel. Most striking – especially to a writer – is the tight plotting. Hume, I guess, really thought through his plot before he put it on paper. To a native of Melbourne, the description of the city is delightful, in particular the slums of Little Bourke street. There’s plenty of interesting social history contained in it too. Sure there were bits when the novel strained a little, and parts where it dragged, but we should remember that it predates Sherlock Holmes, and almost certainly influenced Conan-Doyle, who had read it by the time he started A Study in Scarlet. Maybe a bit dated, but I liked it a lot.

View all my reviews

May 16, 2014

Pompeii: The Film

So I saw the latest disaster film, Pompeii, which is a kind of combination of Titanic with Gladiator. I can’t say it’s a great movie, though it is a fun one. To a Pompeii-lover like me, there were a few annoying things. Like, at the beginning I think that there is a shot of one of the main characters arriving from Rome, but approaching Pompeii from the south. But really, what is there to say about a film like this? It lumbers on, pretty much as we would expect. The fight scenes are fun. The oppositions are interesting enough. Events occur when we expect them. We are never really surprised. Perhaps the most notable thing is that Kit Harrrington doesn’t really have the gravitas to carry the film, something we couldn’t be sure about having only seen him in the ensemble cast of Game of Thrones, where he fulfils his duty as Jon Snow ably enough. Sure he’s pretty and brooding and his abs are cut as finely as anyone’s, but to carry a film, one must have a different order of charisma, one which is impossible to fake, and hard to learn. The film, then, was standard fare. I wouldn’t watch it again, but I watched it once and it served its purpose well-enough.

May 15, 2014

Fergus Hulme’s Mystery of a Hansom Cab

A great little book, I discovered some early feminism in there. From an entire section on it, there is this little quote:

Depend upon it, that if Adam was angry at Eve for having eaten the apple and got them driven out of the pleasant garden, his descendants have amply revenged themselves on Eve’s daughters for her sin.

May 11, 2014

London Steampunkery

May 8, 2014

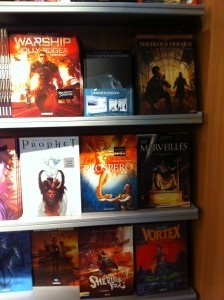

Paris

I’m travelling, so don’t have too much time to blog, but here are two photos to make up for it. They’re from a bandes desinées shop in Paris. I bought a Sherlock Holmes one, which looks very cool. It’s on the top right-hand corner above. There’s an interesting piece on bandes desinées here.

May 3, 2014

The Politics in Science Fiction

A few days ago, Foz Meadows wrote a widely circulated piece on why politics belong in science fiction. The background was this: there has been a flare=up of the culture wars in the SF community, sparked by the odious views of Vox Day, a man of virulent racist and homophobic opinions, who apparently helped coordinate a Sad Puppy slate of nominations to the Hugo awards. The fight seems to be escalating, and it will be interesting how it all plays out at the London World SF convention later this year.

Foz’s article does a good job of explaining the background to this, and why these folks are so reprehensible, but I wanted to add a few comments.

Foz’s article was an immediate response to Glenn Harlan Reynolds’ meagre article which claimed that politics don’t belong in science fiction. Reynold’s article should be understood as part of a long-held right-wing position plea against ‘political correctness’. This particular tactic is to cry at the ‘censorship’ that those poor beleaguered Rightists have to endure in the face to the cruel totalitarian Left. It’s a ploy that emerged as a response to the various movements that emerged from the Sixties, gained currency particularly during the 1980s – the era of Reaganism and Thatcherism – and today used pretty much across the world. What it always amounts to is this: ‘The horrible Left criticise me when I’m racist, sexist and homophobic. That’s censorship! I have a right to be racist, sexist and homophobic!’ Of course this relies on a terribly distorted version of the word censorship, one which equates criticism with a government policy that makes the publication of an opinion illegal. But it also cleverly shifts the terrain from the politics at hand to another more abstract one. Racism gets translated into an abstract question of ‘rights.’ Criticism of sexism becomes ‘bullying’. (The term political correctness was once used by the New Left (often ironically), but was rediscovered in its modern sense by conservatives in the late 1980s).

Second, it’s worth remembering that although Reynolds holds up the Golden Age SF as one where the field was not rent by politics – here he seems to mean the institutions of SF, not the ideology of its writers – actually, he’s just plain wrong. For example, before World War Two, back in 1937, Donald Wollheim delivered a speech (written by Johnny Michel) denouncing “the Gernsback Delusion,” that idea that technological progress would lead to a glorious technocratic utopia, without consideration to the social arrangements that would need to accompany them (how many of those techno-utopias were white! William Gibson wonderfully critiqued these in his ‘The Gernsback Continuum;). This focus on society obviously marked them off as Leftists. Wollheim unsuccessfully moved,

that this, the Third Eastern Science Fiction Convention, shall place itself on record as opposing all forces leading to barbarism, the advancement of pseudo-sciences and militaristic ideologies, and shall further resolve that science-fiction should by nature stand for all forces working for a more unified world, a more Utopian existence, the application of science to human happiness, and a saner outlook on life.

This was a clear statement against the rise of Fascism, and the leading lights of this motion – the Futurians (including Asimov, Pohl and Judith Merril – who should be better remembered than she is) – were Leftists. Andrew Milner and Robert Savage have written about this here, and they explain:

In 1938, he and like-minded friends formed a Committee for the Political Advancement of Science Fiction, composed the “Science Fiction Internationale” (Moskowitz 149), and drafted a manifesto with “a lot of V.I. Lenin in it, and a lot of H.G. Wells,” according to Pohl’s memoirs. In 1939, Pohl proposed a Futurian Federation of the World, thus anticipating Wells’s own similar (and only slightly less ineffectual) wartime gestures. The same year witnessed what sf fanlore still knows as the “Great Exclusion Act,” when a half-dozen of the more querulous and left-leaning Futurians, including Pohl, Wollheim, and Michel, were banned from the World Science Fiction Convention.

In other words, even in the days that Reynold’s claims were blissfully ‘apolitical’, SF was rent with political disagreements. Maybe they quietened in the immediate postwar period, but they burst forth again in the late Sixties (when Galaxy published two lists of SF writers, one for and one against the Vietnam war).

The organisation of the Sad Puppy slate reminds those of us who consider themselves progressive that we too have to organise in the the field of SF. Like all cultural fields, SF is fractured politically. That’s not something we can avoid, nor is it something we should be afraid of. Science fiction writers are like any other group, responsible for the world we live in. Indeed, as people who are thinking about the future, we have a responsibility to. Perhaps its even time for a more formally organised network of progressives. Quite what this would look like, I’m not sure, but one thing is certain – we can’t leave the field empty for Vox Day and his hench-creatures.

April 30, 2014

The History in Steampunk

As I’ve been writing the Australian Steampunk novel, a surprising issue has arisen: how does one deal technically with the boundaries between the real history and fantastical additions? It’s trickier than I thought it would be, partly because it’s a historical novel, so there’s going to be a gap in the reader’s knowledge anyway. I think I’ve mentioned before that Melbourne had some of the tallest buildings in the world in the 1890s, great Victorian sky-scrapers, like the APA building here.

But if one mentions the great skyscrapers, it’s quite likely the reader will think this is fantasy, rather than reality. The maxim that reality is stranger than fiction here might be recast as history is stranger than fiction. The technical task is to indicate the boundaries of the two, but doing so in an unobtrusive way. Here’s a little bit.

They lit the lantern from the hansom cab, and stepped along the dark tunnel, avoiding the trickles of water and puddles of brackish water. The bluestone roof arched above them, and the place smelled of dank refuse, and Genie hitched her skirt up with both hands. She cursed that she did not have more practical clothes — trousers, to begin with. Luckily her lace-up boots were sturdy enough and without too-high heels (which she regarded as painfully superfluous for the modern woman).

On they went, into the looming darkness, only the little bubble of light surrounding them. Genie felt vulnerable, now and was glad to have detective Lynch’s grim determination beside her. Genie knew that the drains beneath Melbourne connected with older caves and tunnels. In the last decades, as many of them had been built, again and again the work teams had broken through to ancient grottos, filled with stalactites and stalagmites. It was down here that the mole-people lived. By rights, they should have been called wombat people, for there were no moles in Australia. Their history was uncertain. Some said they were originally escaped convicts. Others that the mole people had been there since the beginning.

Melbourne does indeed have lots of drains (and grottos) beneath it, though most were built in the 20th century, I believe, so this is mostly fantasy – though Melbournian readers may think otherwise because it’s based on what later developed, another curious technical consequence of alternate history. Melbourne doesn’t, of course, have older caves down there – so here we enter the realms of fantasy proper. Nor does it have mole people – is there a better name for them? – though it does have the Cave Clan.