Rjurik Davidson's Blog, page 8

April 27, 2014

On ‘Likeable’ Characters

On the piece I wrote for Tor called Finding Unwrapped Sky I wrote this: “None of the characters is particularly likeable and each does questionable things. In fact, I’m surprised when readers express a desire to ‘like’ a character, as if they’re considering them as friends. I’d much prefer to find them to be interesting and flawed.” Well, perhaps this is a bit of an exaggeration. Each of the three characters – Maximilian, Kata, and Boris – have good traits and each does kind things. Still, there are reviewers who have objected to the characters’ unlike-ability. More interestingly, there are those who suggest they have had trouble ‘connecting’ with them, while there are those who say they think they’re complex and well-rounded (or words to such effect).

What are we to make of this?

The first thing to note is that readers read for different reasons. Some read for escape or comfort. Some read to challenge themselves. Some read for ideas, for work or to analyse the book as the production of a particular ideology. Some read for all these reasons, or for some of them at particular times and others at other times.

What makes someone connect with a character, then? The same applies, I’d suggest. Different readers will find different things to connect with. Some genuinely want a character to ‘root for’, in which they can project themselves, and I want to examine this for a moment, and how a writer achieves it. When I was a teenager, I would often read in this way. I’d see myself as a particular character. I’d want to be them: let’s say someone like Aragorn from Lord of the Rings. Aragorn is a good guy, but he has had his troubles. When we first meet him – as Strider – he is alone, weathered, deprived of his rightful throne. He has a clear-cut definable goal to achieve.

This is a good beginning to build a ‘likeable’ character. If you want to build up sympathy or empathy with a character, it helps to put them through particularly bad experiences, tough events, especially at the beginning of a novel. The trick is they should be unfair. No one likes to see a character suffer unfairly. It piques our rage – it reminds us of the time we were treated unfairly.

In this kind of reading – reading as projection – the reader also likes people who are good at things – things we wish we were good at. This is a particular hazard of comic books and thrillers, in which the character is preternaturally skilful as a warrior. Strider is mean with a blade, but he’s also special: he’s a man of noble ‘bloodline’. He’s genetically superior to the common folk.

We also like characters who are charming. Think of Tyrion Lannister in Game of Thrones – always ready to throw out a quip. Strider has too much gravitas for quips, so he loses out there, but sometimes we wish we had Tyrin’s wit.

So all of these imply a certain kind of identification with a character, one I’m not completely comfortable with. Characters who are little more than wish-fulfilment tend to leave me cold. You’ll find some of the above elements in the characters in Unwrapped Sky, but only a few, and not thoroughly consistently. I’m not sure people will be wishing to be Kata, Maximilian or Boris too quickly. Part of the reason is that they also do things which are – as I said above – questionable. But this is essential for the kind of book I’m writing, in which the good guys can be bad and the bad guys often good. For me, this reflects the state of the world much more closely, because the world is complex, more complex, I’m afraid, than Tolkien would allow. Who among us hasn’t done bad things, perhaps for good reasons? Who among us – in a world struck down with environmental destruction, poverty, war – can claim to be completely un-compromised? To do the best we can, that’s all we can ask of ourselves, knowing that too often we will fail. It’s not exactly the kind of message a reader looking solely for escape or comfort will enjoy. You can’t find much wish-fulfilment there. But you can find, I think, something interesting.

April 24, 2014

Finding Unwrapped Sky

I’ve written about the process of writing (and inspiration behind) Unwrapped Sky. You can read it over on Tor UK’s site.

April 23, 2014

Interviews

There are quite a number of new interviews with me online, for those interested:

Interview with the Book Plank.

Interview with the Qwillery.

Interview with Nathan Burrage over here.

Interview with Jon Page at Boomerang Books.

April 22, 2014

Snippet of Steampunk Melbourne

I’m not sure what I’m calling my new novel, but here is a little selection of it, for you. From the Journal of Samuel Atterby, who is on an expedition into the centre of Australia to find the inland sea:

Being an Account of the Expedition of Discovery into Central Australia,

By Samuel Atteberry, 1839

One early morning several days later, I dragged myself, sandy-eyed, from the tent. My night had been punctuated by bouts of deep sleep, followed by half-waking states dominated by the Captain’s snoring and horrific dreams that the four horsemen had came upon us, their horses whinnying and breathing fire.

The sun was lost far away, hidden by a heavy fog and I could not see more than a hundred yards through the gloomy dawn. The trees around stood like ancient and twisted men, reaching to the sky with spectral arms. Fear rose in me, swirled around me like the fog itself.

The fire had burned itself out and I stood in silence for moment. The sheep had scattered into the woods. The horses were gone. Now I knew that the dreams of the horsemen were in fact the sounds of our horses as they fled the scene. Only the camel stood stock-still staring balefully back at me.

Patrick was nowhere to be seen.

“Alarm! Alarm!” I cried. There was rustling in the tents as the others staggered out half-dressed and holding their weapons. Together we stared at the ghostly scene and a deep sense of gloom settled over us.

“What happened?” asked the Captain.

None answered, but we knew well enough. We dressed quickly and readied ourselves to search for the animals. Beckman sat on the dray, his gloomy countenance staring into the scrub while Coleman and O’Malley went off together. I joined the Captain in the search for the animals.

The spectral landscape seemed to be from some gothic novel: the twisted gums reaching to the sky, strips of bark falling from their white branches like the rags of nightmare creatures; the chilly silence that hovered over everything. Where were the animals? The rifle felt slippery and cold in my hand. We treaded carefully and I was glad to be with the redoubtable Captain.

Between two of the large gums that dominated that area, I saw a dark shape move; there was the colour brown, and I caught a glimpse of white stripes. My hand trembled. Would I have the strength to fire?

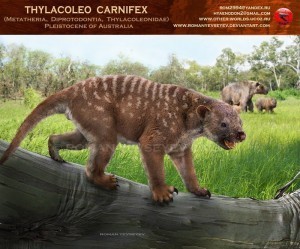

We crept slowly towards the creature, which suddenly sensed us. It turned its lion-like body, and gave a hideous growl. No European can countenance that malign sound, both guttural and rasping — like that of a brush-tailed opossum, but deeper and more terrifying. As it growled, it’s mouth opened wide, showing its stubby front teeth and its powerful jaws. One could not escape the grip of a marsupial lion — thylcoleo carnifex is its proper name — once it took hold of you. Beneath that frightful creature lay the blood mess of one of our sheep, its stomach torn to horrid shreds.

I simply froze, but the Captain raised his rifle in one swift motion. The blast rang through the woods and the monstrous creature fled, its powerful limbs driving it away in but a moment. The Captain fired again, but the creature was gone.

We returned empty-handed. Patrick had not been found. We had also lost four sheep, though only found three carcasses. No one else saw a lion, for they were nocturnal hunters and soon the light broke through the ghostly fog and warmed our icy bones.

The Captain said, “There’s nothing more to do. Let’s be on our way.”

“We have to find Patrick though,” I said.

“He’s gone,” said the Captain. “Nothing will bring him back now.”

So in silence we readied ourselves once more and headed on, each thinking of Patrick and where he might be. What had happened to him in those dark hours of the night?

I found myself riding beside Eddy, who looked close to tears.

“I told him not to sleep,” said Eddy. “I told him.”

“It’s done now,” I said.

“It wasn’t the first time, you know. We’d already lost two more sheep,” said Eddy.

I was stunned. Had Patrick not understand the dangers we faced? Even if we was Irish, a race known for their lack of orderliness and self-control, there was no excuse on such a voyage.

Later that afternoon we came to the Broughton river, which was of considerable width. Wild fowl abounded along its rich banks, for the water was strong and steady. We were travelling between fifteen and twenty miles a day. We set camp and now Eddy and Coleman were given the job of guarding for the beginning of the night. They would wake us halfway through, when Beckmann and I would take the job. We all had a the feeling that a hundred eyes watched us, hidden among the Eucalypus trees.

April 17, 2014

Gideon Smith and the Mechanical Girl

Gideon Smith and the Mechanical Girl by David Barnett

Gideon Smith and the Mechanical Girl by David Barnett

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

From the first, this is a rambunctious adventure which plays on almost every single steampunk trope: Jack the Ripper, dirigibles, Dracula, automatons, Egyptology, and so on. It’s a kind of para-literature and reads like one of the penny-dreadfuls it has so much joy in playing with. Perhaps it’s not wildly original, and at times it is a bit clunky, but we forgive it everything because it is just so infectiously fun. I had a great time reading and the twists and turns kept me engaged. Just when I thought I knew what was going on – and hence, my interest might have flagged – something unexpected sprang up. A great little book – one of a projected trilogy.

View all my reviews

April 16, 2014

On Being Reviewed

My novel Unwrapped Sky finally hit the stores yesterday, but reviews have been coming out for six weeks or so. There have been very good ones, and very bad ones. There have has been at least one in between, I think. For the good ones, the Scifinow one by Jack Parsons is pretty nice. For the bad ones, Liz Bourke’s on my own publisher’s website is worth it.

It’s commonly agreed that a writer shouldn’t comment on reviews of their own work. It’s bad form and looks narcissistic. Here I wanted to reflect a little on the process of being reviewed, of having a book you’ve written out there, available for all to comment on. Though I’ve published internationally before, Unwrapped Sky is of a significantly different scale. It has been reviewed on major websites, in the newspaper of the SF field called Locus, by people I’ve never met and will possibly never meet. It’s still a small stage, but it’s a significantly larger one than I’m used to. There are plenty of writers who don’t read reviews at all, and I can see why. But in the modern world, where you’re meant to get your own work out there – by tweeting, Facebooking, and so on – it’s hard to avoid them. Aren’t you meant to let people know about reviews?

And if so, which ones?

What is a review, after all? Reviews are going to be different, depending on space and audience. A 500 word review in a newspaper is going to be significantly different from a review essay. But in general, my own attitude to reviewing has been this: To begin with, I’ve never written anything I wouldn’t say to someone’s face. I’ve tried to put a work into context – where it sits in the field and in the social space that surrounds it, where it sits in an author’s oeuvre and their life – and to use it to comment on that context. I’ve tried to highlight the strengths and weaknesses of a book (and all books have both strengths and weaknesses). I’ve also indicated whether I think the book is good or bad, in my opinion, but also to allow a reader to know whether they will like it or not. People read for different reasons, after all. Some for pure escapism, some for intellectual interest, and so on. My review of George R.R. Martin’s Dance of Dragons tried to do some of these things in a short amount of space, while my review essay of Lucky McKee’s feminist horror film, The Woman, did so on a more expansive scale.

This is not, of course, the approach of everyone. Many reviewers openly admit they’re not professionals, while many professionals seem remarkably amateurish: if you’re going to be unremittingly negative about someone’s book, you might want to read some of their previous work, so you can put it in context; if you accuse them of sexism, you’d better know if they are a feminist (they may have written something sexist, but at least you’ll understand what they were trying to do). If you claim they’re racist, you might want to find out if they’re Indigenous, or African-American, and so on.

What then, are you sharing when you share a review? What should you be sharing? The line between publicity and the personal becomes awfully blurred here. You’ll piss your friends off if all you do is bang on about how good your own work is, for starters, but then many social media followers aren’t your friends, but are interested in your work.

What about the negative reviews? How should you make sense of them? How should they affect you?

Once you’re on a larger stage, people feel no compunction about attacking someone’s work. In one way, this is admirable, for in smaller literary circles there is often too much niceness and not enough courage. As Jeff Sparrow – with whom I’ve discussed this a number of times – argued in a piece online about ‘anonymous reviewing’:

The great political battles will roll on, irrespective of what happens in the books pages. Like so many other cultural tempests in teapots, this will blow over – with most of the population entirely unaware that the argument ever took place.

Yet if we think literature matters, then how we respond to it should matter, too (which is why it’s so strange to read a critic telling everyone to lighten up about criticism).

Of course, we don’t need a book culture based on attention-seeking hatchet jobs, any more than we need one centred on mutual flattery. We need critics who take books seriously enough to write what they think – and then to stand publicly by that assessment.

Many reviews don’t, of course, measure up to any of these standards – even those of the “professionals”. On a personal level, then, you need to develop a thick skin. You’re in the public eye, people can (and will, whether you like it or not) have opinions that they will express. What’s more, you do best not to take any of them too seriously: one of my most retweeted tweets a month or two ago went something like this: Overly positive reviews and unremittingly negative reviews are both bad for the soul. It’s best not to take either too seriously. I think that’s true.

Developing that thick skin is a little harder, of course, when you’ve been working for some years to have a book published. When you’ve made career and financial sacrifices to do it – when the success of the book is thus very personally important to you. George R.R. Martin need not worry so much about bad reviews, because his books are going to sell regardless (and that is part of the context you’re taking into account as a reviewer). A first-time novelist’s position, however, is much more precarious.

For these reasons, the bad reviews have been more difficult for me to read than the good ones. I always thought I wouldn’t worry much about reviews, but I hadn’t factored in the fact that I would get some unremittingly negative ones (or, for that matter, such positive ones). They always raise the nagging question in the back of the head, “What if the book is not a failure and I don’t get another contract?”

This is not, of course, a purely personal question. The precarious nature of the publishing industry has its effects here too. Writers are struggling along with the industry. The mid-list is being crushed.

At least one thing I remind myself of is that my book – and writing – is not the most important thing in the world. It may be important to me, but others face greater trials. To pick one example, in Australia (and off-shore), there are refugees in concentration camps. It’s useful to remember that we may be the centre of our own lives but that we are not the centre of the world. That notion helps you accept the reviews, good and bad, and to keep on keeping on.

April 13, 2014

Turkey

April 5, 2014

More Steampunk Melbourne

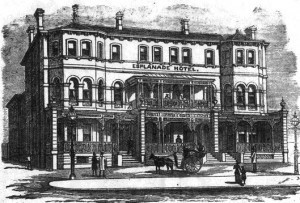

I can’t help it. I’m obsessed with these old photographs. Actually, I’m kinda obsessed with Melbourne’s 19th century history (and my own steampunk recreation of it, in the novel I’m working on) She here we have the Esplanade Hotel in St Kilda, right beside where I used to live. I love it’s former glory: the iron lacework balconies. The wealthy used to live there. Not so now: from my old apartment window I could see that the upper rooms were filled with piles of old chairs and things.

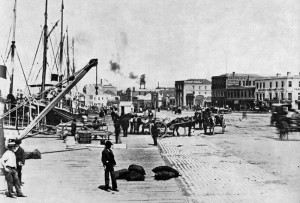

Queens wharf in 1880, on Flinders street (between King/William and Queen):

Another of Queens Wharf, this one in 1870, so a little earlier.

I think these were the original St Kilda Sea Baths, but the newer photographs (say from 1910) show very different buildings. I’m still finding out their history. But anyway, how cool is it?

March 30, 2014

Little Lon, Steampunk Melbourne

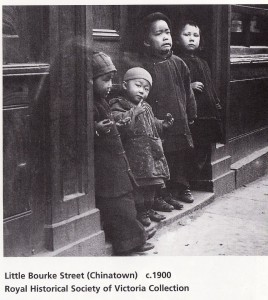

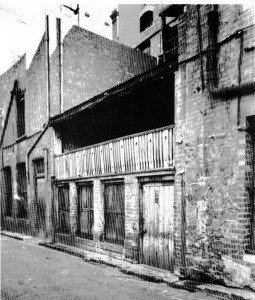

So I’ve been discovering ‘Little Lon’, an inner city area in Melbourne between Lonsdale and Latrobe streets, and Exhibition and Spring. It was a ‘slum area’ filled with brothels, opium dens, and ‘larrikins’. You can be sure it’ll make it into the novel, somehow. Here is Bennett’s Lane, which is just out of little Lon, I think.

Chinatown, a little way away.

George Lane:

A photo of Little Lon:

And a map of it:

March 28, 2014

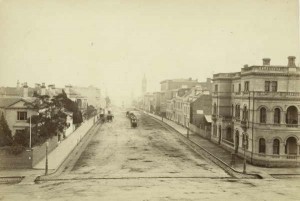

More Steampunk Melbourne

Because I’m addicted, I can’t help but put up some more photos I’ve found in my research. Click in them if you want to see larger versions.

Queens St, around the 1880s.

Collins st, in 1865 (early, huh!)

The Federal Coffee Building, which I just can’t get enough of.

The Deaf and Dumb Asylum, in the late 1860s.

The Melbourne Club. Yep. That wonderful establishment of elite men.

The Hobson’s bay railway pier.

Hotel Windsor.