Rjurik Davidson's Blog, page 5

January 4, 2015

A Frozen Hell – Review

A Frozen Hell: The Russo-Finnish Winter War of 1939-1940 by William R. Trotter

A Frozen Hell: The Russo-Finnish Winter War of 1939-1940 by William R. Trotter

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

Written before he had access to the Soviet archives, Trotter’s book is lively and full of interesting anecdotes. The most interesting part is the early chapter on the reasons for the war. Trotter doesn’t – as one might expect – lay the blame solely on Stalin and his hench-creatures, but emphasises their concerns about the coming German assault. Trotter is also excellent on the cynical machinations of international diplomacy. Trotter’s ultimate support for the “democratic” Finns, fighting for freedom smacks a little too much of ideology, but thankfully this comes late in the book and only lasts a page or two.

As a military history, it is excellent, though mostly told from the side of the Finns. Still the mobile battles to the north of lake Ladoga are fascinating, and the latter-day world-war-one trench warfare on the Karelian Isthmus between St Petersberg and Finland horrifying – if that’s your kind of thing. One can’t help ruminate on the horrendous loss of life, especially on the Russian side, whose tactical crudity wasted soldiers the same way their system of production wasted just about everything. Equally interesting – though not discussed by Trotter – is the question of why, having faced such horrors, the Red Army didn’t revolt against its Stalinist masters, either during the war, or after it. This remains one of the enduring historical questions: just why was Stalinism so stable as a system?

View all my reviews

December 23, 2014

Grimdark Reader’s Years Best

Happy that “Unwrapped Sky” came in at number 2 of Grimdark Reader’s Year’s Best list!

December 13, 2014

2014 in review

Another year is creeping up on us, and 2014 is coming to a close. It’s been a good year, compared with recent ones. Most importantly, my neck/back problems basically resolved, though they took a toll on my the first draft of The Stars Askew, which I finished at the end of 2013. I pity my poor editors who had to wade through that shitty first draft, but this year I managed to do a pretty massive rewrite and I’m happy to say, the book now rocks. In my eyes at least. I think it takes the good things about Unwrapped Sky and then raises the bar. It’s a wider, airier and funnier read – though still retains the Caeili-Amur intensity. The story is written to work as a stand-alone, as well as a continuation of the city’s story, a two bob each way bet, which I hope comes off. I can’t wait to see the responses when it comes out. You can read a snipped of the early draft here.

I have also – along with freelance work – almost finished The Rusted Earth, a gaslight fantasy set in 1890s Australia, with touches of Lovecraftian weird and my own bits and pieces. It’s a funnier book than the other two, a kind-of Indiana Jones-ish adventure, without the Orientalism, I hope. And there are Australian megafauna. You can read a bit of the preface here, though it doesn’t feature the main characters, but rather events 50 years before the main novel begins.

Of course the biggest professional event was the release of my novel Unwrapped Sky, which was reviewed across the world, in the Wall Street Journal and Locus and the Age. There were plenty of reviews, mostly good, a few bad. Some loved it, others hated it, most were somewhere in between.

My favourite album of the year was St Vincent’s self-titled (though fourth) album.

My favourite novel. This one is hard, but three I liked were: Hannu Rajaniemi’s The Quantum Thief, which is amazing; Ben Peek’s The Godless (which I’m still reading, so the judgement isn’t yet conclusive) but is ambitious and original and cool; and Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel, which is also ambitious, and practically experimental, and yet also sort-of epic. Hannu and Mantel’s books aren’t, of course, from this year, but I only read them this year.

My favourite non-fiction work, which I’m also still reading, is the fascinating military history of the Winter War between Finland and Russia, A Frozen Hell, by William Trotter (written in ’91 I think). I like history books now more than any other. Followed closely by science books. Then general non-fiction and fiction last. I think partly the reason is that, unlike with novels, reading them doesn’t feel like work. Also, so many novels are, frankly, not very interesting. Commercial publishing is so driven by the bottom-line that the effect is to limit really original work. As Joe Abercrombie said at some point in London: people want a twist on the familiar. I’d rather read something I’ve never read before.

Favourite film: The Immigrant, which stars Marrion Cotillard and Joaquin Pheonix, both of whom were brilliant. Apparently it was released in 2013, but I only saw it a few months ago in Australia, and I suspect it took a while to arrive there.

I travelled the world a bit this year: to Turkey and Ireland, where my grandmother grew up, and spent considerable time in London and France. All in all, it was a lucky year, a good year. Hopefully 2015 will hold up as well.

November 15, 2014

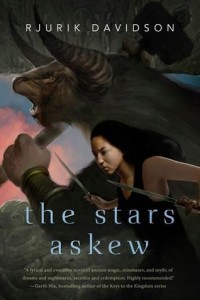

The Stars Askew Cover

The cover for the US version of The Stars Askew seems to have gone out. And here it is, for those interested.

And the PR has gone out too. I there are a couple of inaccuracies, and a couple of small spoilers, but if you really want to know what the book is about, here it is too:

The stunning adventure begun in the critically acclaimed debut The Unwrapped Sky continues.

The Stars Askew is the highly anticipated sequel to the New Weird adventure begun by talented young author Rjurik Davidson. With the seditionists in power, Caeli-Amur has begun a new age. Or has it? The House officials who escaped no longer send wheat and corn, and the city is starving.

When the moderate leader Aceline is murdered, the trail leads Kata to a mysterious book that contains the knowledge to control the fabled Prism of Alerion. But when the last person to possess the book is found dead, it becomes clear that a conspiracy is under-way. At its center is former House Officiate Armand, who has hidden the Prism. He and a family friend are vying for control of the Directorate, the highest political position in the city, but Armand is betrayed and sent to a prison camp to mine the deadly bloodstone.

Meanwhile, Maximilian has a second personality in his mind: that of the joker-god Aya. Aya leads Max to the realm of the Elo-Talern to seek a power source to remove Aya from Max’s brain. But when Max and Aya return, they find the vigilants destroying the last remnants of House power.

It seems the seditionists’ hopes for a new age of peace and prosperity in Caeli-Amur have come to naught, and every attempt to improve the situation makes it worse. The question now is not only whether Kata, Max, and Armand can do anything to lift the state of bloody battle in the city, but if they can escape with their lives.

November 10, 2014

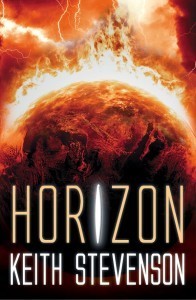

Guest Blog from Keith Stevenson: Horizon — Time Travel: Relatively Speaking

Keith Stevenson is on of the most dynamic people in Australian science fiction, even though he is, in fact, an alien. That is, he’s from Scotland and speaks with as fine a brogue as could ever be imagined. But for many years, Keith has called Australia home, and he is the driving force behind Coeur de Lion Publishing. His also a reviewer and writer of epic science fiction. His novel The Way of the Kresh is long-awaited, and features a magnificent collectivist insect-species facing the threat of colonisation in an interstellar world of Realpolitik. But more importantly, Keith’s debut novel Horizon is soon to be published by HarperVoyager. Here he talks to us about Time Travel, a topic I myself am much interested in. Over to Keith:

I’d like to thank Rjurik for giving over some space on his blog for the Horizon Blog Tour.

Horizon is my debut science fiction novel published by HarperVoyager Impulse. It’s an SF thriller centred on a deep space exploration mission that goes very wrong, with repercussions for the future of all life on Earth.

While the main focus of the story is the tense drama that plays out between the crew in the cramped confines of their ship, the Magellan, a lot of the grunt work in good science fiction goes into imagining exactly how the ‘props’ that support the main action could actually function.

In my post Engage: Tinkering with a Quantum Drive on Joanne Anderton’s blog on 7 November, I talked about the theoretical drive that boosts the explorer ship to an appreciable fraction of the speed of light in order to reach the Iota Persei system in a reasonable time — i.e. before my ‘stellarnauts’ grow too old.

It was important for the story that the world of Horizon was far enough away from Earth for the crew to be entirely isolated from any direct interference — or chance of assistance — from their home planet. That’s why I chose the Iota Persei star system which is thirty-four light years from Earth.

To work out how long it would take Magellan to get there, I had to perform a number of mathematical equations. For someone who failed higher maths at school, it was a bit of a stretch and the results have a fair degree of fudge factor, including not accounting for the time taken for the ship to accelerate from rest, but I think they work well enough to support the story.

Firstly, how far is it to Iota Persei? Saying it’s thirty-four light years away really only means it takes a particle of light thirty-four years to get there. Light travels in a vacuum at a speed of 299,792,458 metres per second, commonly referred to as ‘c’. There are 31,536,000 seconds in a year, which means there are 1,072,224,000 seconds in 34 years (thanks, Excel!). That means the distance to Iota Persei is ‘c’ times the number of seconds in 34 years, which equals 321,444,668,486,592,000 metres, or a little over 321 trillion kilometres.

Secondly, how fast does the crew of Magellan need to travel to get there and not be geriatrics on arrival? The drive of the ship is (kind of) grounded in real world physics. I didn’t want to have a super-sci-fi hyperdrive or warp drive because the launch is only set about sixty to eighty years in the future. I felt that travelling at 0.6 ‘c’ was probably reasonable for technology of that time. Dividing the distance to Iota Persei by 0.6 ‘c’ equates to a travel time of 1,787,040,000 seconds or 56.6 years. Still quite a long time. A crew with an average age of thirty would be well into their eighties on arrival. But I had a couple of extra tools to apply to the problem: one due to relativity and the other, I’ll admit, is a bit of hand-wavy sci-fi.

Special relativity allows that a person who is moving experiences time differently to a person who is at rest. The faster the person travels, the slower time passes for them. This ‘time dilation’ can be worked out by using the Lorentz factor, which, for all you maths nerds out there, is 1 divided by the square root of 1 minus the square of the velocity of the ship over the square of ‘c’. For my crew, travelling at 0.6 ‘c’, the Lorentz factor is 1.25, which means the amount of time that passes on the ship during the journey is 56.6 years divided by 1.25, which is 45.3 years. A little better, but the crew would still be pushing seventy-five on arrival.

So I had to deploy a kind of suspended animation for my crew. Once they leave Earth, the crew enter harnesses, which protect them from the acceleration of the ship and also significantly slows their metabolism. The effect of this is to cut ageing by a factor of seven, so the 45.3 year trip only amounts to about 6.47 years of ageing, which is much better for the purposes of the story.

The thing about writing science-based science fiction is that it takes a lot of work in the background to justify a few words on the page. The explanation above took over five hundred words. Hopefully it’s interesting to read as a blog post, but would be dull as dishwater in a novel. Here’s what all that work ended up looking like in the finished novel:

She still had no idea how long they’d been in deepsleep, and Phillips wasn’t around to tell her. She looked closely at Bren, trying to detect any signs of ageing. The mission was scheduled to take fifty-five years, slightly more than forty-five years’ ship time. On average, deepsleep slowed physical processes by a factor of seven so the whole journey should see them age by a little over six years. Bren’s bleached buzzcut had grown out to a shoulder-length, mouse-brown cloche with a wistful frizz of blonde at the tips. But apart from that and her sickly condition, she looked pretty much the same. Hell, they might be no more than a couple of years out from Earth for all Cait knew.

Follow the Horizon Blog Tour

3 November — Extract of Horizon — Voyager blog

4 November — Character Building: Meet the Crew — Trent Jamieson’s blog

5 November — Welcome to Magellan: Inside the Ship — Darkmatter

6 November — Futureshock: Charting the History of Tomorrow — Lee Battersby’s blog

7 November — Engage: Tinkering With a Quantum Drive — Joanne Anderton’s blog

10 November — Stormy Weather: Facing Down Climate Change — Ben Peek’s blog

12 November — Consciousness Explorers: Inside a Transhuman — Alan Baxter’s blog

13 November — From the Ground Up: Building a Planet — Sean Wright’s blog

14 November — Life Persists: Finding the Extremophile — Greig Beck’s Facebook page

17 November — Interview — Marianne De Pierres’ blog

Keith Stevenson is a science fiction author, editor, publisher and reviewer. His debut novel Horizon is available as an ebook via http://www.harpercollins.com.au/books...

His blog is at http://keithstevensonwriter.blogspot.com.

October 21, 2014

The Red Earth

After six weeks of intense work on The Stars Askew, I’m back to work on The Red Earth, my 1890s alternate history, Australian megafauna novel. As part of the research, I’ve been reading selections of the early feminist paper run by Louisa Lawson from Sydney called The Dawn. Here’s a selection I might just to use:

“Woman,” said an ancient writer, “is the crown of creation.”

As to woman’s prerogatives, it matters not surely whether she discourse fearlessly before the multitude, or whether she speak in tones subdued in private sphere, so that she remains true to herself. One wonders why such dubious feelings should be so often entertained with regard to the propriety of a woman speaking to an audience, when she is entreated to sing to he same, and, indeed, almost worshipped for so doing. Also, she should she not as freely speak her thoughts as write them for the world to read? Was there not a Peitho as well as a Mercury?

The Woman of Tomorrow, The Dawn, August 1893

September 22, 2014

Armand’s opening, The Stars Askew

Here’s another little unedited snippet, to whet your appetite:

Later, when he looked back on it, Armand couldn’t be sure exactly when he knew someone was following him. The knowledge had rattled around in his unconscious mind well before he arrived at the roadhouse at the edge of the small town of Scaptia, a week after having fled Caeli-Amur.

Exhausted from the ride, Armand didn’t so much sit as collapse into the rough wooden seat, his core muscles giving way, his head tilting back, as if any effort was too much. For some time he looked blankly across the dingy hall. In one corner, a group of merchants leaned towards each other, discussing events. Varenis had begun a blockade and this group would be the last to make it to Caeli-Amur, they said. Other traders had been halted at the Palian Wall. Varenis’s grip on Caeli-Amur was tightening.

“Be happy about it,” roared a merchant, whose beard was huge and wild like a mountain-man’s. “Think of the profits we’ll make.”

He slapped his hands on the table to emphasise his point and his beard shook with the reverberations.

“This is the last of it though,” another struck the table in response. “What will become of me, later?”

Armand drifted off to thinking about the following day, when a road would lead off to his left into the Keos Pass. Wastelanders had been streaming away from there, escaping the Site where the forces of Aya and Alerion had clashed almost a thousand years ago. There the two Gods had had bent the air, twisted time and space themselves. Now there were rumours the Site was growing inexplicably, engulfing everything around it. He shuddered at the thought of that strange zone, where the air bent and warped under the strange physics and creatures emerged, horribly changed.

Even now a small group of wastelanders sat in a corner. One leaned back against the wall, weary it seemed. Hundreds of small tentacles wriggled energetically on his forehead. Beside him, a woman stared balefully through eyes that had dropped low around her nose. Her face had grown goatlike and terrible. They were headed to Caeli-Amur, it seemed.

Only then was Armand’s suddenly aware of the shadowy figure, watching him from the corner of the room. The man’s hood was thrown over his head, his features obscured. Armand felt a chill rush down his spine. It came to him then: he had been vaguely aware of the man earlier in the day, in the way some obscure knowledge can lurk at the dark edges of one’s consciousness. Armand had been riding north alone, occasionally passing carts headed south. One had been carrying wool for the weavers in Caeli-Amur, a handsome young man sat on the bales carving a scene from wood. After the cart had passed him, Armand had glanced back, his eyes falling onto the young man. Yes, the ripe lips, the large brown eyes – the young man was dashing indeed. In another life, at another time, thought Armand. From the edge of his vision, Armand had barely registered the hooded figure further behind.

Now sitting in that lonely roadhouse, surrounded by strangers, the reality of the situation struck him. The seditionists had sent a philosopher-assassin after him. Of course they had, for he had been seen rushing through the Technis Palace by several of the officiates. Everything had been mad in those moments after the suicide of Technis Director Autec, with intendants crying in the corridors of the Technis Palace, subofficiates trying to hide in cupboards or beneath desks, the officiates spitting recriminations at each other. Officiate Ijem had used the sphere to connect with Varenis, but the Director had promised only damnation for the officials who had failed to contain the seditionists. Officiate Ijem had run laughing absurdly – he was always laughing – about how they would all die. The seditionists would slaughter them, he laughed bitterly.

Armand stole the Prism of Alerion, the lists of seditionists compiled by House Technis before its overthrow, and the maps of the tunnels beneath Caeli-Amur. He slipped the letter from his supporters into one pocket and he was ready to flee. Dashing to the stables, Armand took the most valuable of horses, a snow-white beast he had called Ice. Using the maps, he slipped through the underground passages beneath the mountain and to the road north. It was only then that he realised the letter had somehow fallen from his pocket. He cursed and railed, but there was nothing he could do.

Ijem or one of the other officiates had clearly talked, and now a killer faced Armand from the opposite side of the common room. The assassin would catch him alone on the road, tomorrow or the day later, and slip a razor-sharp stiletto between his ribs.

September 21, 2014

Opening of The Stars Askew

The opening of The Stars Askew is currently a bit like this:

A revolution, it is said, is a festival of the oppressed. In those early days, Caeli-Amur seemed at times to be one long public meeting. Between the whitewashed walls, the squares and plazas filled with citizens. In the criss-crossing alleyways, hardy washer-women and grim-faced tram drivers debated the new world; in the red-brick factories, committees discussed the running of affairs; avant-garde theatre acts performed bizarre agit-prop on street corners; at the university, students carried on neverending parties, breaking into orgies or fisticuffs before returning to their dwindling stocks of flower-liquors and their nasty yensa-fudge, to begin again. Love affairs were begun; hearts were broken; new ways of living invented. Life itself seemed to have taken on a new intensity and time itself expanded, so that each moment seemed to last forever. And yet, everything was moving at such a pace!

In the heart of the city, the grand Opera building was abuzz. Rough seditionists coursed up and down its grand stairs in and out of its immense doors, heading on their urgent business – for in truth, the city was falling apart.

September 18, 2014

Portland Book Review on Unwrapped Sky

There’s a new, nice and fair review of Unwrapped Sky over at Portland Book Review. Reviewer Whitney Smyth writes:

The story itself is complicated, and deeply rooted in the politics, history, and mythology of the world. Many of the ideas introduced in the book were not resolved at the end, and judging from the book’s marketing it appears that it could be the beginning of a long-running fantasy series. Unwrapped Sky is a good pick for fantasy buffs who enjoy a meatier read, and a novel that wrestles with concepts of power, social injustice, fate, and discovering the consequences of doing the right thing.

August 31, 2014

On Writer’s Block

I’ve written an article for Overland journal about writer’s block. It’s fairly comprehensive, I think, and I hope it helps some writers out there at least a little bit. Here’s how it starts:

There was a time in my early twenties when I found it excruciating to sit in front of the computer. As a teenager, I’d been excited to write, and stories had flowed from me freely.

Then this, from nowhere.

I’d already been published, but that made little difference. I knew I had something to say – coming up with ideas for stories and articles has never been one of my problems – but I found it impossible to drag myself to the study. What the hell was going on? American activist and writer Mary Heaton Vorse seemed to be talking about me when she said that ‘the art of writing is the art of applying the seat of the pants to the seat of the chair.’ But even if I did sit myself down, I would struggle out a few hundred words and grind to a halt like some antique dot-matrix printer at the end of its life.

Because I had accepted a romantic notion of art, it all seemed a mystery to me. Art was meant to be unfathomable. To ask questions about the process, to break it down scientifically, would be to destroy it, I thought.

So I put the problem down to some mysterious personal weakness.

Only recently have I come to think of myself as suffering, back then, from writer’s block, that dreaded curse said to afflict writers at the strangest times, to leave them paralysed, staring at the proverbial ‘blank page’.

One of the reasons I hadn’t thought of my problem in those terms was because I never really believed in writer’s block. When people had mentioned it, I thought they were referring to a lack of ideas, with the blank page representing the blankness of their imagination.

This was not what I was suffering from. I was suffering from an unnecessary blockage, a self-undermining behaviour. My writer’s block was something much more functional: the writing-paralysis caused by anxiety, fear or a similar kind of discomfort.