Rjurik Davidson's Blog, page 3

October 13, 2015

Gramsci’s Political Writings 1910-20

Selections from Political Writings 1910-1920 by Antonio Gramsci

Selections from Political Writings 1910-1920 by Antonio Gramsci

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

Gramsci has been going through something of a renaissance recently, especially in the Anglophone world, due to a combination of factors. First, there’s the fact that he’s been wildly influential on the Greek left and the Spanish left. The version of Gramsci they offer tells us a lot about those political formations. For many in Greece, Gramsci is a kind of radical reformist, a Left-Eurocommunist who offers us a strategy of radical ruptures within and without the state. For those in Spain, principally those in Podemos, he’s a founding figure of post-marxism, and the strategy is one that transcends class. The second factor in the Gramsci renaissance is the fact that in the Post-Stalinism period theory has been shaken up and theorists like Gramsci have been freed from their place in an crystallised ideological structure. The last reason is the publishing program of the group around the Historical Materialism journal, who are bringing to light, or republishing earlier work that speaks to us anew in this new conjuncture. Particularly important is Peter Thomas’s book, The Gramscian Moment.

Gramsci’s early writings are mostly sidelined by the debates over his famous ‘Prison Notebooks’, but there is a lot of fascinating material in this early volume. In his earliest ‘Crocean’ socialist phase, Gramsci is like an early version of Sartre. His emphasis is on eduction and moral development (which, like much existentialism) almost reads like modern self-development pop-psychology). His second, more interesting phase, was as the theorist of the ‘factory council’ movement in Turin. Most of the pieces here are republished from the paper Ordine Nuovo, which Gramsci edited and which achieved mass circulation and great popularity at the time. During this phase, Gramsci is keen to differentiate the councils from the trade unions, which are, in his eyes, simply mechanisms for workers to defend themselves within the framework of capitalism. They were bureaucratic in structure and consciousness. The councils, on the other hand, were the seeds of a new state within the old one. No longer was culture and education so important, for it was through the practice of the factory councils – the radical democratisation of the factories – that workers came to understand their place within society. The debates in the book (are councils the same as soviets? what is the role of a party?) between Gramsci and others (Bordiga and Tasca) are fascinating. Sometimes Gramsci is in the wrong yet his work has a liveliness and originality that is reminiscent of Rosa Luxemburg or the early Leon Trotsky, both in theoretical outlook (emphasis on the spontaneous creative powers of workers) and style. By the final few essays of the book, Gramsci runs up against the problem of the Socialist Party, which was actively undermining the council movement and occupations in 1920. For the first time the ‘political’ proper – that which later defines him as a theorist – begins to dominate his thought, and he moves closer to Bordiga’s call for a new party. The final essay is written only days before the Livrono conference when they split from the PSI, a move that later Gramsci considered a grievous error.

These pieces are, needless to say, of their time and place. The working class has been so transformed in advanced countries that it’s difficult to imagine factory councils emerging as they did in Turin, which was a city dominate by metalworkers and autoworkers. Though one could imagine councils emerging in industrial countries on the semi-periphery (China (Foxconn!), Mexico, Brazil, South Africa, etc). This is also a work predating the emergence of Lenin as a theorist, and it’s marked by that absence. Particularly lacking are notions of strategy or tactics more appropriate to party formations.This was all about to change. Within a decade socialists across the world – including Gramsci – were to associate themselves with the Soviet Union and ‘Leninism’, and then shortly after that Stalin was to finally take power and stamp out the kinds of liberatory currents that Gramsci here represents. But by then Gramsci himself was imprisoned in a fascist prison by Mussolini, and it was there that he was to write his most influential work.

View all my reviews

September 14, 2015

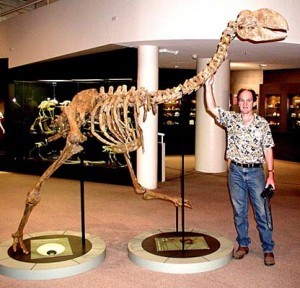

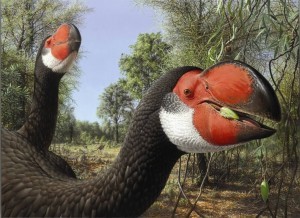

Dromornis Stirtoni and The Rusted Earth

As I recently finished a novel set in 1890s Australia – called The Rusted Earth – with surviving megafauna, I became obsessed with the thunder birds, or Dromornithae. In particular, I very much love the Dromornis Stirtoni, one of the oldest, and the largest of the thunder birds, measuring at 3 metres tall. Why am I in love with them? I’m not sure. I suppose I’m in love with all of Australia’s megafauna. Who wouldn’t be?

Here’s one artists impression, and here’s one of the sections from the novel:

The handsome cab rattled past the great Town Hall, the thunder bird’s powerful legs driving it past a three-storey tram, top-hatted clerks hanging from its sides beside rough-looking workmen. The dromornis stirtoni turned its head, and Detective John ‘Jack’ Lynch caught a glimpse of the bird’s intense red beak. It ruffled its black feathers and let out a savage cry — like that of a screaming hawk — scattering fearful passersby in all directions. An older relative of the smaller and more recently evolved descendent, the genyornis, the dromornis was a truly ancient species. Though they were now increasingly facing extinction, zoologists suggested the birds had survived for millions of years. From it’s wild scream, Jack didn’t doubt it.

Possessing greater speed and endurance than horses, these great thunder birds were the most sought-after steeds for hansom cabs. Jack was lucky his driver, Kenny Lee, had managed to procure this one. Kenny had also fitted out the hansom with compartments filled with all sorts of equipment so that it was practically a mobile expeditionary vehicle. Kenny Lee was a man of practical ingenuity and the future. He kept an eye on the latest technologies, especially those emerging from China and the rest of the orient. As a result, he was always ahead of the rest of the police force’s engineers.

From his place beside Miss Healy, Jack watched as emu-driven rickshaws — the birds seemingly tiny beside the dromornis — ducked in front of them, then dashed away, like a little fleet of mosquitos, their scrabbling on the cobblestones which had been laid during the boom years of the 1880s, when the city was known as ‘Marvellous Melbourne’.

How the city had fallen in recent years, thought Jack. Fallen, like everything.

Here’s a picture featuring a Dromornis’s skeleton, with a stylish guy beside for scale.

September 7, 2015

Dick’s The Simulacra

The Simulacra by Philip K. Dick

The Simulacra by Philip K. Dick

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

Not one of Dick’s better books. There are simply too many balls in the air for him to keep control. Some lovely passages and ideas: the return of the neanderthals after nuclear devastation, Loony Luke and his jalopies which will take you on a one-way-trip to mars, the class-riven society, the fact that the president is a simulacra and the first lady an actor who is really in charge. But Dick can’t pull it off. He probably needed to strip out the time-travel element and several of the characters. But he was writing these so quickly, it’s hard to blame him. Still, not a patch on The Man in the High Castle, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, Ubik, or his other best work.

View all my reviews

August 20, 2015

Unconscious Discrimination and a Regressive Culture

Over at , Kirstyn McDermett and Ian Mond discuss to ongoing issue of women’s representation in fiction. The discussion related to a number of things, including this piece on Jezebel, where Catherine Nicholls describes sending her novel out under a male name, and the way the responses immediately became more positive. She writes:

Within 24 hours George [her nom-de-plume] had five responses—three manuscript requests and two warm rejections praising his exciting project. For contrast, under my own name, the same letter and pages sent 50 times had netted me a total of two manuscript requests. The responses gave me a little frisson of delight at being called “Mr.” and then I got mad. Three manuscript requests on a Saturday, not even during business hours! The judgments about my work that had seemed as solid as the walls of my house had turned out to be meaningless. My novel wasn’t the problem, it was me—Catherine….Even George’s rejections were polite and warm on a level that would have meant everything to me, except that they weren’t to the real me. George’s work was “clever,” it’s “well-constructed” and “exciting.” No one mentioned his sentences being lyrical or whether his main characters were feisty.

She also makes the point that a certain conditioning process goes along with this:

The interim period is also important, where writers are neither beginners fresh for the journey nor secure professionals with a known name. In between, where a writer is alone for a long time with her work, a “clever” might be enough to steer her toward a bolder plan, and a “not very likable” guides her back to conventions. A small series of constraints can stop the writer before she’s ever worth writing about. Women in particular seem vulnerable in that middle stretch to having our work pruned back until it’s compact enough to fit inside a pink cover.

There should be no surprises here. There’s ample evidence for unconsciously held attitudes which leave all of us prey to dominant cultural attitudes, attitudes which marginalise various groups. In an article on this, I wrote about the need to be conscious of this process:

The point isn’t to be self-flagellating – who among us lives outside of our society? – but to be sensitive. The writer needs to understand society as a whole or risk reaffirming the ideologies of oppression. I’ve sat in writing workshops where a writer has sat blank-faced and uncomprehending as socially conscious participants have attempted to explain this to him (and most commonly, though not always, it’s very much a male).

Writing, then, involves a conscious rearrangement of what your unconscious has provided. That’s the only solution until the culture itself changes. Indeed, in some small ways we can hope that the writing itself helps to change that culture and to provide our minds with more enriching fuel, rather than the paltry stuff to which we are now accustomed.

Where I differ from Kirstyn and Ian is that I don’t think it’s quite good enough to say, “It’s okay to read what you like”. It’s not a matter of people feeling guilty, but rather that all of us – readers included – need to examine our assumptions and reject those which are, to put it crudely, sexist, racist, homophobic, and so on. There’s a narrative dimension to this too. Certain types of narrative are encouraged (linear, goal-driven, in which a character overcomes obstacles and becomes a hero). Characters must be “likeable” (what are they, our friends?!), and usually special. The way this plays out in genre can become pretty regressive. There is an implicit sexism, say, to most feudal fantasy. As I wrote about Game of Thrones in another context here (and also about fantasy and violence here), most fantasy in conservative:

Fantasy has traditionally been dominated by the conservative view: all those neo-feudal world desperate for a farm-boy to rise to his rightful place as benevolent dictator – uh, I mean King. Order will be restored, everyone will find their rightful place in some parody of the divine right of kings. Don’t get me wrong, I love Tolkien, but we should be clear about his lineages.

Our problem, though, it that this kind of critique runs directly counter to the trends in society and publishing. We live in an era when, as a friend of mine commented recently, “My most successful books have been the ones closest to genre formulae.” That is, that the industry itself has a tendency towards repetition, towards standardisation, towards formula – to put it crudely, most people don’t want to read stories that bring them back to the world, but take them away from it. Fantasy sells more than science fiction, because it fits that pattern most obviously. People want to read barely disguised wish-fulfilment – hence the dominance of the superhero narrative in film. The conditioning that that Nicholls mentions in her Jezebel piece isn’t just gendered: it goes along with all writers who aren’t commercially very successful. I’ve had a number of people – in and out of the publishing industry – steer me towards the more formulaic (“write epic fantasy!”). They were being helpful. They were trying to look after my career.

This gets back to something I wrote a couple of days ago, but never quite finished: the publishing industry is all numbers and algorithms now. Market mechanisms have been introduced at every level. There is a systemic logic to this. When an agent looks at a woman writer’s proposal, they’re not just being unconsciously prejudiced, they’re also being honest about the ‘market’. They’re making a judgement, “Will this sell?” Fantasy sells more than science fiction. Men sell more than women. It’s an eviscerating logic.

Our only chance is to challenge this kind of culture as a whole, then. So even if, as Ian said in the podcast, people don’t want you to bring up unpleasant truths – they don’t want to feel guilty – it’s not good enough. We have to challenge them, as part of a more general cultural campaign, a long, extended, war of position for a better industry and culture. This doesn’t mean giving up or not reading writers who are objectionable (among my favourite writers are Lovecraft and Ellroy), but it’s about what we value. It’s about seeing that often the breaking apart of formula and traditional form is what needs to happen if we’re to express new content. It’s about valuing the work of small presses, who publish more innovative or experimental work. It’s about challenging our own narrative preconceptions. For example, on the same podcast, they reviewed Ben Peek’s excellent book, The Godless , which – whatever its flaws – does some new and original things in fantasy. That is wasn’t, say, on the Aurealis Award shortlist this year I found astounding – given, as Ian and Kirstyn mention, it’s a multicultural fantasy featuring gender equality of sorts. That it wasn’t recognised is a symptom, I’d say, of the problem we have — that commercially successful (or popular) and good are not homologous. Nor is popular taste and quality. That’s something we have to try to rectify if we want to challenge sexism, racism, homophobia and the kind of eviscerated culture that too-often sees good books sink and terrible books make millions.

August 18, 2015

Callinicos’s Marxism and Philosophy

Marxism and Philosophy by Alex Callinicos

Marxism and Philosophy by Alex Callinicos

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

Something more than an introduction, this little book gives a cursory summary of the field at the time it was written – the 1980s. Still, it’s a pretty good little text, starting with modern philosophy before Marx — Kant, Descartes, Hegel, etc — and ending with debates as they were in the 80s. Hegelian Marxists will probably find it too Althusserian, Althusserians too orthodox, but his short engagements — with language, ideology, science — are useful, even when you might not agree with him. There’s also much to agree with, including his take on science, ideology, and some of his reading of Marx. Probably the most anomalous and uninteresting sections are those on English and analytic philosophers. A book like this would now have to deal with Badiou (a kind of modern-day Althusser) and Zizek (probably the dominant Hegelian philosopher). Still, I’d recommend it as a good place to go one step beyond an introduction. A decent little book. 3.5 stars.

View all my reviews

July 25, 2015

No Room for Error: Thoughts on Commercial Success and Writing Part One

A couple of days ago, I came across a piece in the Portland Monthly on one of my literary heroes, Ursula K. Le Guin. It was a fine piece, and it quoted Le Guin’s National Book Awards speech, in which she said:

We need writers who know the difference between production of a market commodity and the practice of an art … Developing written material to suit sales strategies in order to maximize corporate profit … is not quite the same thing as responsible book publishing or authorship.”

The piece continued with this:

Foremost among her concerns these days, it seems, is what Le Guin considers a worrisome literary shift whereby writers—squeezed to make a living in a world that attaches less and less financial value to their profession—view themselves more as brands and “content producers” than artists. “I see so many writers getting pushed around by the sales department, the PR people, and being led to believe that that’s what they do,” she told me. “That’s a terrible waste.”

Artistic resignation in the name of pragmatism—“letting commodity profiteers sell us like deodorant, and tell us what to publish, what to write,” as she put it in her National Book Awards speech—elicits Le Guin’s especial disapproval precisely because she herself spent an entire career bucking what others thought she should write.

There’s a lot to like here. I’ve always resisted the notion that writers should see themselves as “businesses”, and talk about their “brand”. This entrepreneurialism is really an internalised neoliberalism, which has us see ourselves as individuals struggling in the open marketplace, when in fact, most of us are “proletarian writers” (as Philip K. Dick used to refer to himself as), that is, workers how produce for companies – but particularly declassed workers, with few rights.

What Le Guin is getting to here are the changes in the publishing industry itself: The integration of market mechanisms into every level of publishing, the tendency towards standardisation and repetition, the consistent debasing of narrative under these pressures, the elimination of the midlist, the ubiquity of the Neilson Bookscan as a measuring instrument, the determining influence of ‘numbers’ and algorithms.

Though there’s no way to be sure, I suspect even Le Guin would have had difficulty in this environment. Though her first three novels show some of her strengths, they are mostly uneven books, and each would have been caught in the midlist, I think. It was only with the Earthsea books and The Left Hand of Darkness that she suddenly broke through. This isn’t an unfamiliar phenomenon. Writer Scott Westerfeld once said to me, at a dinner, that “There’s something about your fifth book when it all comes together.”

But how many writers get a chance to write their fifth book, nowadays? The systems cuts them off. It’s succeed immediately or not at all, and that is part of the reason writers get pushed around and are happy to write what they’re told to. There’s no room for error.

Tomorrow, I’ll conclude these thoughts.

July 12, 2015

Even A Stopped Clock is Right Twice a Day

Were the radical Left wrong to participate in Syriza? I’m obviously aware that from afar, many things are difficult to tell. Still, we need to make some kind of assessment, just as we might make an assessment of history – for ourselves as much as anyone – and so below are some preliminary thoughts after having watched the recent debate between Stathis Kouvelakis and Alex Callinicos:

Since the capitulation of the Syriza government, a veritable Greek chorus of voices have claimed that that the Syriza project was compromised from the beginning, that this if further evidence of the cul-de-sac of ‘reformism’, and proof that one must build a separate ‘revolutionary’ organisation of self-conscious cadres, or the social force ‘from below’. Alex Callinicos presented a relatively sophisticated version of this in his recent discussion with Stathis Kouvelakis on socialist strategy, discussion well worth watching (as is their earlier debate, in February). The Syriza experiment is strategically defeated, he claimed. By implication, he reasserted the strategy pursued by Antarsya of remaining outside the Syriza front and building a theoretically coherent ‘core’ of Marxists.

No doubt, these criticisms should be taken seriously, especially as we weight up the scale of the defeat. Were we not foolish, to see in Syriza a step forward for the Left? Could we not say in advance – despite Syriza’s origins in the Greek social and anti-austerity movements – that it would turn out badly?

On the whole, it seems to me that these arguments miss the mark, and rather than think through the concrete conjuncture and arrangement of forces, simply repeat abstract verities. Worse, they threaten to erase the very lessons we might learn from the Syriza experience – about how a concrete political project might be constructed on the basis of a ‘transitional program’ of demands and by alliance-building across political traditions and theoretical outlooks.

The point, then, is not so much that one must build a self-conscious theoretically developed and coherent ‘core’ but how one does such a thing. Indeed, we can still assert that before this capitulation, the most intelligent strategy was to have built that core within Syriza.

There are a number of reasons why:

1. Syriza was, for the last few years, the key terrain of political struggle for the ‘Left’. It was where all eyes – Greek and international – were focussed. It was where the Greek working class put its hopes. To refuse to participate was to marginalise yourself from all of this.

2. Syriza was relatively open. This is a key question for the Left. No form of alliance or entryism can be undertaken if you are effectively muzzled, or controlled by the Right, but partly due to its recent origins, Syriza afforded space, and indeed positions of influence, for a conscious Left.

3. The development of Syriza was not preordained. Yes, it was clear that Tsipras and his collaborators were pursuing a dead-end strategy from early on, but it was also possible that, with pressure from below, they may have chosen to honour the Thessaloniki program rather than capitulate. It was also possible that the Left Platform might grow significantly, even to the position of leadership, or at least to a position where they might be unable to be ignored. It was possible that another round of mobilisations might take place from below. Events are not preordained, but depend on activity and intervention.

4. There is a tradition of such an ‘entrist’ strategy, in the form, for example of the ‘French Turn’ advocated by the Trotskyist movement in the 1930s, which was designed to bring the small groups from the margins back onto the terrain of struggle, into where there were significant activists and workers. The point of such entrism is to be in a position to influence events when the leadership makes its betrayals – to coalesce a force out of the struggles.

These reasons help explain the difficulties faced by the other socialist groups or coalitions such as Antarsya, which according to Kouvelakis, are ‘as weak as they were’ at the beginning of the crisis. By remaining outside of Syriza, not only was the Syriza Left weakened, but Antarsya removed itself from a key terrain of struggle.

It’s important not to see the past through the prism of the present. No doubt, with the capitulation of Tsipras, conditions have changed and so should strategy. To argue that now, after the capitulation, is the time to build a separate group from Syriza, is to argue it in the current conjucture. For this reason, we can agree with Callinicos when he makes a criticism of the Left Platform’s MPs, who refused to vote ‘no’ to the new ‘deal’. We can agree with him when he suggests the Left Platform need to break with the government and campaign among the Greek people against it, asserting that ‘we are the representatives of “oxi!”’ (though he fails to note that they are only in a position to make this choice because they have been within Syriza during its rise; we can only imagine how much of a better situation it might be if Antarsya (as a whole or in sections) was in the Left Platform).

The schism between the Greek people and the Syriza leadership is now wide. No Left can afford to accept the government’s proposals if it wants to avoid self-destruction. It may be that there is now a basis for organisational separation. Whether this would occur immediately, or after a period of struggle and organisation, or whether Tsipras – as some papers today suggested – will expel the Left, is a matter we can’t possibly comment on from afar. But certainly, the Left will quickly decay if it fails to fail to distinguish itself from the government line.

The claims that Left involvement in Syriza was always an error have an advantage: history has caught up with them. But even a stopped clock is right twice a day. A position held six months ago might become ‘correct’ in the present, but that doesn’t mean it was correct six months ago. Circumstances change. Correct lines become wrong. Wrong lines become correct. The question is to get the right line at the right time, and to keep the clock’s hand moving so that it tells the correct time, whatever the situation.

June 18, 2015

New Story: Skins

You can read my new short story, ‘Skins’ about intimacy and refugees in a future French fascism at Cosmos Magazine (ps, a skin isn’t a cyborg). It opens:

She doesn’t know I’m hovering a few steps behind her, my skin crawling with anticipation. She’s pushing through the metro crowds, past fortune-tellers with names like Doctor Sidibe and Queen Adama, who are passing out business cards. One session to discover one’s future love and wealth – it isn’t so much.

When she reaches street level, she glances across Boulevard de Clichy, up the rising alleyway, to Sacré Coeur.

A hundred mouches buzz around the metro exit, recording and assessing for anonymous companies or départements. The government already knows me, of course. And who isn’t petrified of those policemen, hopped up on amphetamines, with their implants and body modifications? I can’t remember the number of times I’ve turned a corner to see two of them slouching, faceless behind their chunky insect-like masks with their flapping trunk-like appendages. I should be safe: I was born in France, but it has a peculiar effect on your mind, those half-hidden police and those little mechanical flies, spinning in the air, their thousand refracted eyes pinning you, recording your every move, feeding it into the System for later use.

But there’s no time to worry. Not now when I have her in my sights.

May 22, 2015

Mark Lawrence’s Prince of Thorns.

Prince of Thorns by Mark Lawrence

Prince of Thorns by Mark Lawrence

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

I’ve been meaning to write a review of Mark Lawrence’s book for some time; I read the book over a year ago, but things never quite aligned. Anyway, Lawrence is one of the new, cutting edge fantasy writers, and very popular. His protagonist – Prince Jorg – is a kind of fantasy Flashman, a lying, cheating, sociopath who returns after some years on the road as a thuggish criminal to his father’s domain. His intention: to reunite the lands under his sociopathic rule.

It’s an excellent novel which zips along with dark wit and action. Lawrence has mastered early the skill – essential to be popular – of sparse writing. For a musician, the notes which aren’t played are as important as those which are. You musicians quite often fall into the trap of showing of their virtuosity, of playing too much (this, I might say, is something a weakness of mine, in my own work). Lawrence doesn’t have that problem, and it helps explain the wide appeal of his book.

I find a lot of fantasy derivative and, well, boring, even though I write it myself. My own tastes have me searching for something I’ve never read before. I want surprise. Lawrence’s world isn’t too surprising, but it’s a testament to his narrative skill that he kept me reading. He knows how to keep us wondering: what will happen next? Prince of Thorns is not a deep examination of society or a radical recasting of the genre; it’s primarily entertainment and good entertainment at that.

Lawrence has – from what I understand – come under attack for having an antihero as a protagonist, and for the fact that the bulk of the characters are men. This seems to me to miss the point. It’s not the actions (murder, cheating, rape, etc) that a character undertakes in a book, or they types of characters, but rather the attitude the book takes to those characters and their actions. Of course, there is an ambivalence to Prince of Thorn’s attitude to Jorg: it’s impossible to see things through his eyes without investing in him in some way. But there’s no doubt in my mind that Jorg is not being held up as a hero. We’re not supposed to think he’s a good guy. Indeed, there’s an implicit critique of him all the way through the novel, a kind of dialectical undercurrent that continually reminds you that this guy is bad.

Lawrence is published pretty much everywhere, and he’s obviously writing parallel to the Grimdark writers. Along with the Game of Thrones TV adaption, he’s part of an entire wave of darker fantasy, which it seems to me reflects our times – I think of it as fantasy after 9/11. Lawrence is one of its foremost representatives.

View all my reviews

May 16, 2015

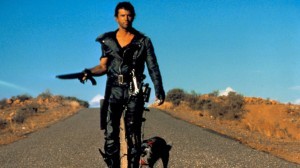

Mad Max: Fury Road

I’m not sure how it happened, but I saw Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior when I was about ten or twelve years old. That’s too young. Seriously. But like all such things we experience too soon, it had a deep, lasting impact on me. Mad Max was, of course, a particular product of Australian culture. We’re suited to the post-apocalypse, not only because so much of the country is beautiful and blasted, but because with colonisation, Australia suffered its own kind of apocalypse – all those films of the empty desert, or the deadly desert, need to be understood as unconscious rendering of the genocide of the indigenous population. And yet the early movies are explicitly post-nuclear war films, and reflect the pretty large fear of nuclear war which was so omnipresent in the 1980s. They were parables then, warnings.

In The Road Warrior, Max himself is a kind of Australian archetype, with his blue heeler dog, his hotted-up car, and his unacknowledged sense of social justice. This was back when Mel Gibson was beautiful, he was also ours, before we knew that he was a nutty anti-semite, and when Australian cultural nationalism was still associated not with the Right but the Left, especially in Australian film (the films of Peter Weir, Fred Schepsi, and other of the Australian New Wave). Those contradictions were yet to unravel. Certainly as a ten-year-old, the world of Road Warrior was terrifying, but it was also familiar, as it would be to any Australian ten year old, who had been on some kind of road trip, even if only along the coast.

My memories of it were compressed, selective: first, the rape and murder of a woman, which mostly happened off-screen but which disturbed me no end; second, the design, the wondrous punk design, of cobbled together cars and clothes; third, the brutal sense of hope stripped away, the slightest sliver of it kept alive only through death and sacrifice; finally, the startling cinematography (in which the DOP and editor cut out several frames each second, to give it that startling jagged quality). As with Planet of the Apes, which I saw at a similar time (and also only remembered in fragments), it marked me.

What then of Fury Road, which has been receiving rave reviews? It’s not often I see a blockbuster which doesn’t disappoint, and Fury Road is that. What interests me most, though, is that though I don’t much like action movies, and though Fury Road is pretty light on for story and characterisation (which it still manages to do nicely, if only in broad brush strokes), it still held my attention. How? The secret must be the film’s sheer inventiveness. Fury Road takes everything which is good about the early Mad Max movies, and pumps them up, as if on amphetamines. The avant-garde and punk sensibility shines, the design is magnificent, the set-pieces impressively imagined, when it stretches credibility (the metal-playing guitarist who hangs in front of one of the trucks, riffing as they drive through the desert; the scantily-clad collection of models, straight from some outback photoshoot, who Max helps escape) it manages to steer its lumbering, out-of-control, ramshackle story back onto the road. It’s loud. It’s brash. It’s over-the-top. It’s wonderfully mad. And best of all, it’s pretty openly feminist. We know this from two scenes: when Charlize Theron’s character Furioser uses Max’s shoulder to rest a rifle, proving herself a better shot than he; and when he washes blood from his face with breastmilk. No wonder the Men’s right’s Activists are up in arms. Indeed, there’s a good case to say that she’s the more central character to the story.

If there are criticisms, we could agree with some of those mentioned by Erik Kain at Forbes, especially that Hardy can’t match Mel Gibson as Max, that The Road Warrior was more intimate and real, and that the ending of The Road Warrior was more messy and ambiguous. All of these are true, but Fury Road has its own consolations.

Post-apocalyptic tales are our lot now, because, of course, it’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism. Like with Children of Men, and The Road, the jury isn’t out on this one.