Alan Jacobs's Blog, page 4

August 25, 2025

notes of a supply officer

“You have to make your voice heard!” – so the exhortation goes, though the remainder of the sentence usually goes unsaid: “… on the issue that at the moment I think to be the most important.” Nobody thinks you have to make your voice heard about everything all the time, which in any case would be impossible. The same unspoken addendum fits onto “Silence is violence.” All these exhortations have the same essential meaning: If you do not care about what I care about in the way that I care about it, you are a bad person. The language of alliance works the same way: If you say what I want said and do what I want done you are my ally — and if not you are my enemy.

The problem with all these exhortations is their failure to understand how society works. A society or a culture is a vast corporation, a vast body of persons and things that functions only if the principle of division of labor is acknowledged and put into thoughtful practice.

Consider an army: Would an army function if everyone strove to fight on the front lines? Of course not. But that is just what the people who demand that you “make your voice heard” and “get involved” and “take sides” want us all to do: rush to the front and try to overwhelm the enemy with our sheer numbers. (One other unconfronted assumption of this way of thinking is that the other side won’t be acting the same way.) A successful army requires warriors but also generals, strategists, doctors and medics, supply systems, and, before all that, training systems. And a healthy society requires even greater diversity and specialization than an army does.

I often think of a woman I met some years ago whose life is devoted to rescuing abandoned or abused dogs. If she never thinks a thought or says a word about the issues that dominate social media, who cares? She is doing the Lord’s work. Not everyone should do what she does; but she should do what she does.

When I observe my country I am regularly horrified and outraged by the great evils done by our government and by our largest and most powerful businesses. I want to protest, I want to “make my voice heard.” But As I look around I find myself thinking not that too few people speak up, but that too many do: too many people with uninformed minds and unconstrained emotions. We have a surfeit of people who want to fight and not enough willing to train and supply. I often think about something Bob Dylan once said:

There’s a lot of things I’d like to do. I’d like to drive a race car on the Indianapolis track. I’d like to kick a field goal in an NFL football game. I’d like to be able to hit a hundred-mile-an-hour baseball. But you have to know your place. There might be some things that are beyond your talents. Everything worth doing takes time. You have to write a hundred bad songs before you write one good one. And you have to sacrifice a lot of things that you might not be prepared for. Like it or not, you are in this alone and have to follow your own star.

Well, what’s my place? As a teacher, I hope to train and liberate minds; as a writer, I supply people with ideas and contexts, with substantive frameworks to shape and interpret thought and aesthetic experience. Over my forty-three years of teaching, I have gotten used to the rhythm of my life: training and encouraging people as best I can, and then sending them out into the world as well-equipped as I can help them to be. And writing, of the kind I do anyway, is not so different: it too is a kind of provisioning.

In such matters it’s good to remember what the Preacher says, “In the morning sow your seed, and at evening withhold not your hand, for you do not know which will prosper, this or that, or whether both alike will be good.”

When I get the itch to shout or protest or condemn, I remind myself of my place: training and supply. And I remind myself of what is not within my power to control. It brings me peace in convulsive times to remember that I am, after all, following my own star. Which star should you follow?

August 19, 2025

a word to my students

The first thing to know is that I don’t call it AI. When those of us in the humanities talk about “AI in education” what we almost always mean is “chat interfaces to large language modules.” There are many other kinds of machine-learning endeavors but they’re not immediately relevant to most of us. And anyway, whether they’re “intelligent” is up for debate. So the word I’ll use here is “chatbot,” and the question is: What’s my policy? What do I think about your using chatbots for work in my class?

I’ll start to answer that by turning it around: If I forbade chatbot use, would my stated policy have any effect whatsoever on your actions? Pause and think about it for a moment: Would it?

For some of you the answer will be: No. And to you I say: thanks for the candor.

Others among you will reply: Yes. And probably you mean it. But will your compliance survive a challenge? When you’re sitting around with friends and every single one of them except you is using a chatbot to get work done, will you be able to resist the temptation to join them? When they copy and paste and then head merrily out for tacos, will you stay in your room and grind? Maybe you will, once, or twice, or even three times, but … eventually…. I mean, come on: we all know how this story ends.

So let’s be clear about three things. The first is that if I make assignments which you can get chatbots to write for you, that’s what, eventually if not immediately, you’ll do. The second is that if I have a “no chatbot” policy and you use chatbots, you’re cheating. The third is that cheating is lying: it is saying (either implicitly or explicitly) that you’ve done something you have not done. You are claiming and presenting to me as your work what is not your work.

Now, this has several consequences, and one of them — if I don’t catch you, and I don’t plan to spend my precious senior-citizen years trying to catch cheaters — is that I will end up affirming that you have certain skills and abilities that you do not in fact have. Which makes me, however unintentionally, complicit in your lie. That reflects badly on me.

But that makes a problem for you, too, because sooner or later the time will come — perhaps in a job interview, or an interview for a place in a graduate program, or your second week in a new job that doesn’t have you in front of a computer all day — when your lack of the skills you claim to have will become evident, to your great embarrassment and frustration. You’re probably not worried about that now, because one of the most universal of human tendencies is — I use the technical term — Kicking The Can Down The Road. Almost all human beings will put off dealing with a problem if they possibly can; the only ones among us who don’t are those who have learned through painful experience the costs of can-kicking. (This is in fact one of the very few ways in which we Olds are superior to you Youngs: we’ve been there. We have so been there.)

And then I’m a Christian, and I’ve read the parable of the talents. I want to see you multiply your gifts, not leave you exactly as you were when you came to my class, only with a little more experience in writing chatbot prompts. (Would a personal trainer be happy if you instructed a robot to do pull-ups and crunches for you? Would he think he had done his job?)

Perhaps the most worrisome consequence of this whole ridiculous circus in which (a) you’re trying not to get caught cheating and (b) your professors are trying to catch you cheating is how thoroughly dehumanizing it is to all of us. All of us end up acting like we’re in a video-game boss fight. Modern education, with its emphasis on credentialing and therefore on grades, is already dehumanizing: as Tal Brewer of UVA says, we’re not teachers, we’re the Sorting Hat. The chatbot world makes that all crap so much worse. Now we’re Boswer and the Sorting Hat.

But I just want to help you to be a better reader, a better writer, and a better thinker. If you can learn these skills, and the habits that enable them, I believe you will be a better person — not in every way, maybe not even in the ways that matter most, but in significant ways. You’ll be a little more alert, a little more aware; you’ll make more nuanced judgments and will be able to express those judgments more clearly. You may even grow in charity and self-knowledge. I want to do what I can to encourage those virtues.

I don’t want to be trying to outwit you and avoid being outwitted. I don‘t want to enable your can-kicking. I don’t want to affirm that you have skills you don’t have. I don’t want to have to say, at the end of the day, that the only thing I taught you was better prompt engineering. Above all, I don’t want to make assignments that become a proximate occasion of sin for you: I don’t want to be your tempter. So I simply must — I am obliged as a teacher and a Christian — keep the chatbots out of our class, as best I can, and to do so through the assignments I devise. If you pray, please pray for me.

August 18, 2025

due diligence

NetChoice is a massive coalition of internet companies — look who’s in it — that is throwing enormous resources to block any law or proposed law in any and every state that requires age verification for access to websites. Given the technical challenges that make reliable age-verification schemes difficult if not impossible, I might have sympathy for the NetChoice companies if they weren’t who they are. (Oh the moral dilemma: thinking that laws are probably unconstitutional and yet wishing they succeed because you find the companies the laws target utterly loathsome.)

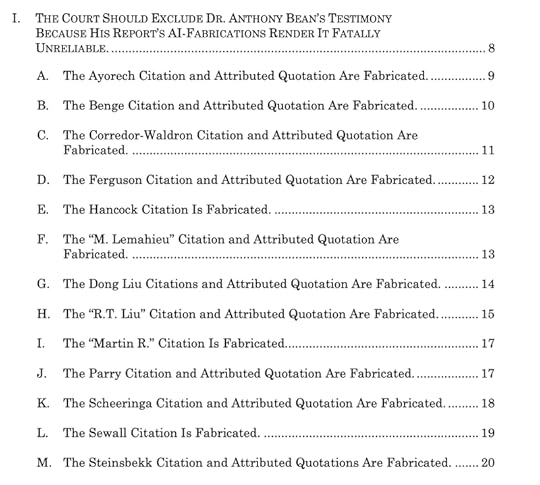

So in fighting a Louisiana law NetChoice recruited a supposed expert named Anthony Bean to affirm that social media use is not bad for young people in any way. As Volokh explains, the Louisiana Attorney General’s office took a look at this expert report and discovered that

None of the 17 articles in Dr. Bean’s reference list exists…. More, none of the 12 quotations that Dr. Bean’s report attributes to various authors and articles exists (even in the original sources provided to Defendants).

A cursory comparison between Dr. Bean’s report and the disclosed original sources would have alerted NetChoice that something is amiss. In fact, just reading Dr. Bean’s report would have done so. His reference list makes no sense, (a) citing website links that are dead or lead to entirely unrelated sources and (b) citing volume and page numbers in publications that are easily confirmed to be wrong. And his report itself is strangely formatted, not least because, well, it looks and reads like a print-out from artificial intelligence (AI).

Dr. Bean’s report bears all the telltale signs of AI hallucinations: completely fabricated sources and quotations that appear to be based on a survey of real authors and real sources.

(More like Mister Bean, amirite?) It’s kinda fun to look at the contents of their reply to Dr. Bean’s testimony:

Etc. There’s a joke going around that A.I. will create jobs because when a company turns a job over to chatbots it’ll then need to hire two people to find and correct the chatbots’ hallucinations.

Two predictions:

No matter how many organizations get burned by reliance on chatbots, new organizations will always buy in, thinking Well, we won’t get burned No matter how many people get caught farming out their work to incompetent chatbots, new people will always buy in, thinking Well, I won’t get caughtMost human beings are, it seems, genetically predisposed to believe that there really is such a thing as a free lunch and that it’s just waiting for them to pick it up. The question is: How long will be take for people who are rooted in reality, and therefore perform due diligence, to outcompete the mindless herd?

August 14, 2025

the daily driver

Whittaker Chambers, in a 1954 letter to William F. Buckley Jr. and Willi Schlamm:

If I were a younger man, if there were any frontiers left, I should flee to some frontier because, when the house is afire, you leave by whatever hole is open for whatever area is freest of fire. Since there are no regional frontiers, I have been seeking the next best thing — the frontiers within.

I get up early in the morning, feed and walk Angus, make some coffee, check email and my RSS feeds while drinking the coffee I made, answer emails, post links or images to micro.blog and/or sketch drafts of posts for the big blog … and then get off the internet until late afternoon.

I have an old easy chair where I usually work, and before 8am I am sitting in it with

booksarticles (printed out)my notebookmy Travelerpencils, pens, highlighters, sticky notesmy Sony voice recordervinyl records or CDs on the stereoThe key point is this: I do not have any internet-viewing device with me as I work. The nearest one is my Mac, across the room. I get up and use it when I have to check some piece of information I can find only online, but that happens rarely, and I try as I’m working to make note of what I need to search for so I can do all the searches at once at the end of the work day.

The internet is a dark realm which I do not visit except upon compulsion. My old chair is Hobbiton; the internet is Minas Morgul. I would not go there except upon compulsion.

Most of the time I write in the margins of the books I read, or on their endpapers, or on sticky notes appended to their pages. When I have longer things to write, I do that on the Traveler, which uploads files to a website from which I can retrieve them and edit them on my Mac. (That’s my only internet connection when I’m at my chair.)

Or, and this is increasingly common, I record my thoughts on my Sony voice recorder.

Here’s my workflow for audio notes: First, I record thoughts and in some cases whole drafts on the Sony, which uses the MP3 format. Then, near the end of the work day, usually around 3pm, I rise from my comfy chair and

plug the Sony into my Mac;use an Automator action I wrote to (a) open a recording in QuickTime Player, (b) export to M4a, (c) open in Voice Memos, (d) quit QuickTime Player; after which…Voice Memos transcribes the audio file, the text of which…I copy and paste into a chatbot text field with the following prompt:I’m about to paste in a chunk of text. Please punctuate it, add capitalizations and quotation marks where necessary, eliminate repetitions and grammatical errors, but otherwise leave the text unchanged.

It doesn’t really matter which chatbot I use — they all do an adequate job, and adequacy is what I want here: I still have to write the post or essay, I just want at the outset something that’s easier to look at than a huge block of unpunctuated text.

(I use chatbots for this, for summarizing product reviews, and for helping me write AppleScripts. That’s pretty much it.)

Now, I could simplify this whole process by dictating in the Voice Memos app, which would then automatically transcribe my words. But that would mean dwelling in Minas Morgul all day. Not worth it.

Then, in the evenings, I might read a book, or listen to music (probably on vinyl or CD), or watch a movie (probably on disc). When I’m walking Angus, or just walking, I listen to Morning Prayer on the Church of England’s excellent Daily Prayer app, and when I go to bed I might listen to a podcast. Also, I watch a lot of soccer on TV, and streaming makes that possible. But overall, these days the internet plays a smaller role in my life than it has in … 25 years, maybe? Yes, there are days when I need to be at the Mac for extended periods. But overall, it has become normal to me once again to experience the internet as a place I occasionally (and for some specific purpose) visit rather than the place where I live.

And this feels great. I am happier, more serene, more centered. I feel that I am spending my time more wisely and more enjoyably. I understand, of course, that many (most?) people will not be able to detach themselves from online life to the extent I have. But then, a couple of years ago I wouldn’t have thought it possible for me to detach this much. If you take it one step at a time you might discover that you can do more than you think.

For instance: I used to subscribe to Netflix and Disney Plus, but when I ditched those I suddenly had the money to start building up my Blu-Ray collection. Many video discs are quite inexpensive new, and it’s easy to find good used ones; Blu-Ray players are also pretty cheap. In a short time you can have a nice collection of your favorite movies, all of which will, to you, be worth watching repeatedly. You’ll often (always, if you buy Criterion editions) have some special features on the discs that enhance your appreciation of the movies. Once you start a movie you’ll probably watch it through, because the temptation to switch over to something else will be much reduced. And everything will work even if your internet goes out.

I could tell the same story about how I listen to music and have built my music collection. Also about what I read. It’s remarkable how many sites and periodicals I used to read religiously I now avoid religiously.

It occurs to me that if I could just ditch my footy habit I could probably cancel my home internet and get by with cellular service. Now that’s something to aspire to … but I love footy too much.

August 12, 2025

a good and faithful servant

My dear friend of many years, Jay Wood, has died. I want to pay some tribute to this extraordinary man but it is difficult, for me anyway, to know what to say. He was so distinctive — I’ve never met anyone like Jay; he didn’t fit the usual categories. He had a sharp and dialectical mind, and spoke forcefully, which intimidated many people. But he was also exceptionally kind, always quick to notice those in need and to give of his resources.

One summer day in Wheaton Jay and some other friends had come over to my house for a time of fellowship and prayer, and I had to apologize because my air conditioning system had gone out and I had yet to find the money to get it repaired. Later that day there was a knock on my door: it was Jay, lugging a big window air conditioner which he then installed for me. (It had been sitting in the basement of a friend — Jay asked if he could have it.) Probably everyone who knew him at all well has a story like this.

When Jay was a young faculty member and had little money, he managed to buy a house that needed repairs that he simply couldn’t afford to have done. So he taught himself how to do everything needful — from hanging drywall to wiring a room to plumbing to building a deck — and then for the rest of his life would gladly share his knowledge with other people.

He was a person of exceptional discipline, in almost all the ways one could be disciplined. He was always in great shape: he ran marathons, and also would put the Wheaton football players to shame with the number of pull-ups he could do. He also considered it his absolute duty to go to church, so one Good Friday he sat through a service in agony, because he had a kidney stone … which he passed before the service was over. I’m not sure Jay fully understood why other people weren’t as disciplined as he was, but if he judged us he did so silently.

Jay and his friend and colleague (also my friend and colleague) Bob Roberts wrote a wonderful book on the intellectual virtues, and no one could have striven more consistently to practice those virtues. We had some great talks about the subject when that book was being written.

These are all miscellaneous reflections; they probably don’t add up to anything. As I say, Jay is very hard to describe. But maybe one more story will help.

Jay and I shared the experience of growing up in highly dysfunctional homes, with fathers who were damaged themselves and did much damage to others. That Jay ever became a Christian is so remarkable a thing that it almost by itself proves the existence of a merciful God; and I think the primary reason for his self-discipline was to emancipate himself from the consequences of that upbringing. He wasn’t perfect; he always had rough edges; but nobody knew that better than Jay.

All that is the context for one of my strongest memories of Jay, and one of the most influential ones in my own life. This was early in our friendship, probably some time in the early 90s. We were at Jay and Janice’s house, talking in their living room, and Jay was sitting in a chair by a doorway. One of his daughters, Diana or Gillian, ran across the room and was headed through the door when Jay shot out an arm and roped her in. She squealed Daaaadd! — but he gave her a big hug and a kiss before he let her go.

I said “She’s gonna hate that before too much longer.” Jay smiled. “I don’t care. I’ll still do it. My kids will always know how much I love them.”

And they do. Adam and Diana and Gillian and Sam — and now the grandchildren, and always, of course, Janice, his wife of nearly fifty years. They all know how much Jay loves them.

August 11, 2025

the truth in view

One of the finest poems by the great Richard Wilbur is called “Lying.” Says Wilbur: When we make things up, when we claim to have seen a grackle (or some more numinous creature) when we didn’t really, this is a displaced “wish … to make or do.” But when we lie in this way we misunderstand our situation — misunderstand ourselves and our world:

In the strict sense, of course,

We invent nothing, merely bearing witness

To what each morning brings again to light:

Gold crosses, cornices, astonishment

Of panes, the turbine-vent which natural law

Spins on the grill-end of the diner’s roof,

Then grass and grackles or, at the end of town

In sheen-swept pastureland, the horse’s neck

Clothed with its usual thunder, and the stones

Beginning now to tug their shadows in

And track the air with glitter. All these things

Are there before us; there before we look

Or fail to look; there to be seen or not

By us, as by the bee’s twelve thousand eyes,

According to our means and purposes.

(Job 39:19, the LORD to Job: “Hast thou given the horse strength? hast thou clothed his neck with thunder?”) The key phrase is “All these things / Are there before us.” We must simply discover the will and the wisdom to recognize what is already present to us. “The arch-negator” — that is, Satan — manages only briefly and imperfectly to obscure the radiance of the world: In Eden he was but

… darkening with moody self-absorption

What, when he left it, lifted and, if seen

From the sun’s vantage, seethed with vaulting hues.

Here we might remember one of Wilbur’s earlier masterpieces, “The Undead,” in which he counsels us to recognize the condition of vampires: “Their pain is real, and requires our pity.” Because all they can do is “prey on life forever and not possess it, / As rock-hollows, tide after tide, / Glassily strand the sea.”

Wilbur says that have this desire to make or do, and in our “moody self-absorption” sate it with lies, when we could find what we seek if we look — really look.

Closer to making than the deftest fraud

Is seeing how the catbird’s tail was made

To counterpoise, on the mock-orange spray,

Its light, up-tilted spine; or, lighter still,

How the shucked tunic of an onion, brushed

To one side on a backlit chopping-board

And rocked by trifling currents, prints and prints

Its bright, ribbed shadow like a flapping sail.

Here let me direct you to the second chapter of Robert Farrar Capon’s wonderful book The Supper of the Lamb, in which he teaches you how to look at an onion. But back to Wilbur.

Simply making a simile is a way of seeing — or perhaps the making of a simile is a natural product of seeing. And even the the smallest simile, Wilbur says, is “tributary / To the great lies told with the eyes half-shut / That have the truth in view.” I love that phrase, that way of describing our artful tales and tropes. It’s worthy of being placed alongside Sidney’s Defence of Poesy.

Our eyes are half-shut because we’re partly viewing the world and partly retreating within ourselves to find an a response to what we have already seen — to find what the poet Donald Davie called “articulate energy” — syntax adequate to the thing. Wilbur’s offers three examples of such great lie, and the third is this:

That matter of a baggage-train surprised

By a few Gascons in the Pyrenees

Which, having worked three centuries and more

In the dark caves of France, poured out at last

The blood of Roland, who to Charles his king

And to the dove that hatched the dove-tailed world

Was faithful unto death, and shamed the Devil.

(Re; shaming the devil: this is an old proverb, most famously used in Henry IV, Part I by Hotspur to Owen Glendower, who has been boasting of his power over sprits: “O, while you live, tell truth and shame the devil!”)

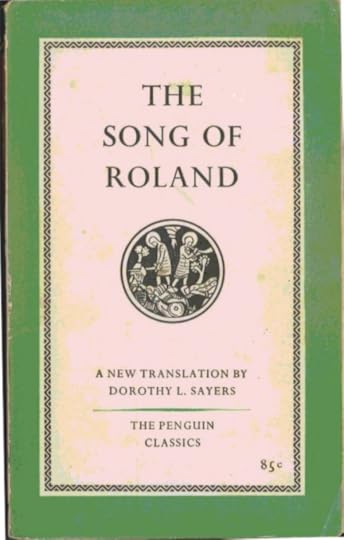

Wilbur is talking about The Song of Roland of course, and these words, coming at the end of the poem, tell us of two ways of shaming the devil: to be “faithful unto death” in one’s deeds and in one’s words.

That is my Thought for Today, but I want to add a postscript. For my biography of Dorothy L. Sayers, I have been reading her translation of The Song of Roland — the last work she completed in her life. She begins her long and remarkably helpful introduction to the poem by describing, quite flatly, a minor skirmish in the year 778, an ambush of the rear-guard of one of Charlemagne’s armies in the Pyrenees in which a few people were killed. A chronicler writing in 830 named some of them; another chronicler ten years later mentioned the skirmish but did not name the dead, since, he said, they had already been named.

So goes Sayers’s first paragraph. And when you read the second one you’ll see where Wilbur got his inspiration for the conclusion of his poem:

After this, the tale of Roncevaux appears to go underground for some two hundred years. When it again comes to the surface, it has undergone a transformation which might astonish us if we had not seen much the same thing happen to the tale of the wars of King Arthur. The magic of legend has been at work, and the small historic event has swollen to a vast epic of heroic proportions and strong idealogical significance. Charlemagne, who was 38 at the time of his expedition into Spain, has become a great hieratic figure, 200 years old, the snowy-bearded king, the sacred Emperor, the Champion of Christendom against the Saracens, the war-lord whose conquests extend throughout the civilised world. The expedition itself has become a major episode in the great conflict between Cross and Crescent, and the marauding Basques have been changed and magnified into an enormous army of many thousand Saracens. The names of Eggihardt and Anselm have disappeared from the rear-guard; Roland remains; he is now the Emperor’s nephew, the “right hand of his body”, the greatest warrior in the world, possessed of supernatural strength and powers and hero of innumerable marvellous exploits; and he is accompanied by his close companion Oliver, and by the other Ten Peers, a chosen band of superlatively valorous knights, the flower of French chivalry. The ambuscade which delivers them up to massacre is still the result of treachery on the Frankish side; but it now derives from a deep-laid plot between the Saracen king Marsilion and Count Ganelon, a noble of France, Roland’s own stepfather; and the whole object of the conspiracy is the destruction of Roland himself and the Peers. The establishment of this conspiracy is explained by Ganelon’s furious jealousy of his stepson, worked out with a sense of drama, a sense of character, and a psychological plausibility which, in its own kind, may sustain a comparison with the twisted malignancy of Iago. In short, beginning with a historical military disaster of a familiar kind and comparatively small importance, we have somehow in the course of two centuries achieved a masterpiece of epic drama – we have arrived at the Song of Roland.

That is, a “small historic event” has been magically transformed into one of “the great lies … that have the truth in view.” The idea of a simple story going “underground,” deep into the unconscious lives of a people, and then emerging as something altogether other and more resonant is the image that Wilbur, with his poet’s alertness, picks up from Sayers.

August 8, 2025

girl Friday

Of all the classics of the Golden Age of Hollywood, the most overrated is His Girl Friday (1940) — and I say this as a great lover of Howard Hawks’s movies. This is his big clunker. It’s frenetic, regularly unfunny, and completely lacking in the vivid and memorable supporting-actor parts that are so important in the true classics. (And in other Hawks films.)

The only way you could possibly rescue the movie is by seeing it as a very different kind of story than its self-presentation would indicate. So here goes.

To understand what’s really going on in it, you have to compare its opening and closing scenes. In the opening scene Rosalind Russell’s Hildy Johnson is striding happily and confidently into the offices of a newspaper. In the final scene she is stumbling tearfully and confusedly and (above all) obediently out of a press room in the wake of the domineering Walter Burns. She is a woman destroyed.

And she has been destroyed by a monster. Not one moment in the movie gives us any reason to believe that Walter loves Hildy. We only know that he values her journalistic skills and abilities as a writer. Indeed, it seems obvious that while Walter ends by announcing that they will remarry — note: he is not asking her to re-marry him — he only does this to keep her under his thumb: marriage is the best means for him to control her and deploy her talents in ways that serve his ambition. Throughout the movie he shows no signs of caring about anything except his power to make or break political careers. Hildy is the primary instrument through which he can wield this power; that is why she must be wholly within his control and obedient to his dictates. He is a kind of vampire who feeds on her blood, without killing her. He needs her to be alive but weak.

That is to say: the only way you can redeem His Girl Friday – telling title! – as a movie is to see it as a tragedy, as Hildy’s tragedy. Given the social situation of women at this time and in this place, she has to choose between being a wife and mother in Albany or a journalist in New York – but the second option, while it gives her scope for her intellectual gifts, means being subservient to a man’s control far more completely than marriage to the boring Bruce would entail.

His Girl Friday is thus less like Bringing Up Baby or The Lady Eve than it is like Hedda Gabler. It’s impossible to forsee any future for Hildy other than working herself to the nub to make Walter happy with her. She won’t have any children because she and Walter don’t have sex — indeed, they have probably never had sex: Walter is a man whose sexual instincts are thoroughly and completely re-channeled into his libido dominandi. Do they look romantically intimate at any moment in the movie? They do not. If there’s any chemistry between the two of them, it’s not sexual, it’s power-based.

And if Burns is like anyone else in classic Hollywood cinema, it’s the Charles Boyer character in Gaslight, except that he doesn’t want Hildy’s money, he wants her energy and ability. And when that’s gone he will cast her aside.

Walter Burns is the nastiest character that Cary Grant ever played, not excluding the murderous husband in Suspicion (and of course he’s murderous there, don’t be silly). And there are few movies, if any, in that era that strike me as being as darkly depressing. The snappy tone of the film cleverly disguises the real arc of its story. Walter Burns is a vampire and Hildy Johnson his victim. She’s like Earl Williams, the convicted but possibly innocent murderer she interviews: both of them are trapped. The difference is that Earl knows it.

August 6, 2025

Allan Dwan’s stories

There are a lot of stories about the intense conflicts between old Hollywood and new Hollywood. An oft-told one says that at a party Dennis Hopper went up to George Cukor, pointed a finger in his face, and said, “We’re gonna bury you.” This sense that the new Hollywood was at war with the old one — that the new could only live if the old died — was a commonplace idea at the time. But it was not a view held by one of the hot new directors of the Sixties, Peter Bogdanovich.

I’ll probably say more about Bogdanovich’s artistic debt to Old Hollywood in another post, but for now: When he came to Hollywood, Bogdanovich made a point of getting to know the people who had made so many of the movies he loved. He compiled a book of interviews with old-time directors — he also did one with old-time actors, but the one with directors is particularly noteworthy.

Of all those interviews, the most fascinating is the very first one, with Allan Dwan, because Dwan was present at the creation. He had played football at Notre Dame, got an engineering degree there, worked on designing lights for filmmakers, and gradually drifted into making movies himself. He sold some stories, became a scenario manager, and ultimately a director, making dozens and dozens of films — none of them especially famous. His attitude towards movie-making was workmanlike, and he just accepted the tasks set before him.

(He told Bogdanovich that when directors started taking seventeen weeks to make a picture that he would have made in seventeen days, that brought in the producers to manage everything. After that, no director was safe from studio interference. This reminds me of something Christopher Nolan said in his Desert Island Discs interview a few years ago: that right from the beginning of his career he made a particular point of bringing his movies in ahead of schedule and under budget because that was the only way to keep the studio execs away from his sets.)

Dwan’s stories are absolutely fascinating because they show what it was like for Hollywood to be invented. Nobody knew what they were doing. He tells a story about his days as a writer and scenario manager: he showed up at a shoot in Arizona only to discover that the director had disappeared and the actors were just sitting around. He called his bosses in Chicago to report what had happened, and they told him, “Well, you’re the director now.” He had no idea what a director did — but, with the help of the actors, he directed the movie. This happened in 1911. Dwan kept directing movies until 1961.

He tells another story about getting his car repaired and talking to the mechanic, who turned out to be interested in photography. Dwan hired him as a cameraman because he desperately needed one and in those days they weren’t easy to find. That mechanic-turned-cameraman eventually became a director — his name was Victor Fleming, and one of his pictures was Gone with the Wind. Dwan remembered a prop man who liked to wear fake teeth and prosthetic noses. Dwan asked him, “Why are you doing this? Do you want to be on the other side of the camera?” The guy said, “Well, kind of.” That was Lon Chaney.

He also tells of watching a pickup baseball game near the Paramount lot and seeing a girl — maybe 11 or 12 — who was the best player out there and made sure everybody knew it. She was whacking the ball all over the field and taunting the boys mercilessly. Dwan talked to her; he thought she’d make a great impression in the pictures. Her name was Jane Peters, but eventually a studio changed it to Carole Lombard.

(Lombard, by the way, was quite an athlete: Clark Gable fell in love with her after she thrashed him in a tennis match.)

Dwan had a thousand stories like this. It’s fascinating to see how this industry — this art form — developed when nobody knew how to make movies. Dwan himself was the first to figure out that you could dolly a camera backwards, putting it on rails or a truck and backing up. (This actually disoriented viewers at the time, made them feel woozy). He helped D.W. Griffith figure out how to do a crane shot for Intolerance. All such techniques had to be figured out, improvised — and when an improvisation worked it became an invention. You basically had to think like an engineer, and Dwan was an engineer.

And when you put all the improvised and then repreated techniques together, you get the dominant artistic medium — and the dominant form of entertainment — of the 20th century. But nobody could possibly have guessed any of that when Dwan was just getting started. It’s to Bogdanovich’s great credit that he listened to these people. All his interviews with directors arre good but the one with Dwan is the most illuminating.

August 5, 2025

denialism and its counterfeits

Freddie de Boer noted that Yascha Mounck strives to explain The Peculiar Persistence of the AI Denialists — and I want to note what has happened to Mounck’s key term, “denialism.” It originated of course in the debate over climate change: it was and is used to describe people who deny that the climate is changing, and instead insist that everything is what it has always been and that any apparent warming is merely ordinary variation in weather. The point of the phrase is that we have masses and masses of data demonstrating a long-term trend of increasing temperatures, data that can’t be argued out of existence — so if you don’t like that data you can’t refute it, all you can do is deny. And if you deny all the time you become a “denialist,” and your intellectual strategy becomes “denialism.”

But this is not the situation we’re in with regard to machine learning. Nobody knows what’s going to happen, though we can make some reasonable guesses. We don’t know how much better the LLMs will get; it’s possible that their rate of improvement will slow, and that some problems will prove insoluble without serious methodological change. And if that latter is the case, we don’t know whether new methodological strategies will be tried, and if they are tried whether they will succeed. We don’t know whether hallucinations will become less common. We don’t know whether our comatose legislative branch will arise from its torpor and do something: it’s not at all likely — but legislation could well happen in Europe, legislation that offers a template for U.S. legislation. I wouldn’t bet on it, but we might experience a low-grade Butlerian jihad. And one thing I would bet on is, in the not-too-distant future, some serious and widespread black-hat hacking that the big AI companies would be at least as vulnerable to as the rest of the tech sector. (In this matter we’ve been too lucky for too long.) And it’s impossible to guess what the run-on effects of such an exploit would be.

So what Mounck is doing here is dismissing anyone who disagrees with his predictions of the future as “denialists” — as though his predictions have already come true. Which of course they haven’t; that’s what makes them predictions. It’s not “denialism” to doubt that some extraordinarily dramatic thing will eventually happen — even if your doubts turn out to be unfounded. People only use that word with regard to the future when they think their predictive powers are infallible — which Mounck apparently does.

Thus he concludes:

But if there is one thing I have learned in my writing career so far, it is that it eventually becomes untenable to bury your head in the sand. For an astonishingly long period of time, you can pretend that democracy in countries like the United States is safe from far-right demagogues or that wokeness is a coherent political philosophy or that financial bubbles are just a figment of pessimists’ imagination; but at some point the edifice comes crashing down. And the sooner we all muster the courage to grapple with the inevitable, the higher our chances of being prepared when the clock strikes midnight.

Ah, the old “bury your head in the sand” trope — the last refuge of the truly thoughtless. And then the claim that, since some events in the past have turned out to be worse than some people expected, therefore whatever Mounck is most worried about is “inevitable.” Because no one has ever expected things to be worse than they turned out to be, right? Nobody in 1963 ever said “Anyone who thinks that we can avoid nuclear war is burying his head in the sand.” Nobody in 1983 ever said “Anyone who thinks the Soviet Union will just go away is burying his head in the sand.” Nobody! We’ve never been wrong in anticipating the most dramatic outcome … have we?

I don’t know what machine learning will bring, because, contra Mounck, nothing in this crazy old world is inevitable, and if his writing career lasts as long as mine has, he’ll eventually learn that. But as we move into uncharted territory, I will keep three maxims in mind:

Proceed With Caution “We must cultivate our garden” For every Nostradamus there are a hundred NostradumbassesAugust 4, 2025

my anarchist notebook

I mentioned in a recent post that reading Thomas Flanagan’s novels about Ireland has me thinking about revolution – the causes and consequences of revolution, and of course the difficulty of defining “revolution.” Often it is defined quite narrowly as “an attempt to overthrow an existing government by force of arms” and equally often quite expansively as “advocacy for major social change.” In my recent thinking Michael Collins has played a large role, because while there can be no doubt that Collins wanted the British out of Ireland altogether, he became convinced that the best way to do this was to move one step at a time, to accept Dominion status as a way-station to complete independence. This made him, I think, a kind of gradualist revolutionary, though to his Irish opponents it made him into something altogether unrevolutionary, which is why they killed him. (For urgent Irish revolutionaries, the advocacy of anything other than immediate violence made you a “West Briton,” as Gabriel Conroy is called by Miss Ivors in Joyce’s story “The Dead.”)

My interest in anarchism complicates my thinking about these matters. On the one hand, an anarchist society would be radically different than the one we now live in, and in that sense would be the fruit of a revolution. But organized armed revolution could not, in my view, be pursued anarchically – it would be anti-anarchist even if conducted in the name of anarchy. That was also true of the “anarchist” bombers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries: they were not anarchists, for as Proudhon said, “Anarchy is order”; rather, they were Chaotics, a very different thing. To render a social order non-functional in the hope that something more just will somehow rise from the ruins is antithetical to the character of anarchism, which is all about collaboration and cooperation. Terrorism and armed insurrection are thus equally alien to true anarchism.

So how could anarchism be practiced in such a way that society changes for the better? How is it possible to remake the world without betraying your principles in the process? (“We had to destroy the village in order to save it.”)

I’ve written off and on about these matters for years – see the “anarchism” tag at the bottom of this post – but my thoughts are still largely confused. So I decided to make this post a kind of notebook of ideas. I’ll post today but then I will come back and add second and third thoughts later, and see if some kind of order eventually emerges. After all, isn’t anarchic method appropriate to the study of anarchism?

If you haven’t read anything I’ve written about this, start with this essay and then this reflection on Christian anarchy.

One more thing: my major guides to thinking about anarchism are

Peter Marshall, Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism James Scott, Two Cheers for Anarchism David Graeber, essaysAnd now on to the notebook:

Malatesta thought that the committed libertarian, who cares only about his own freedom of movement, will if he follows his natural course become a tyrant, and in even the best case “anything but an anarchist.”

•

It is vitally important to distinguish anarchism from libertarianism. The highest goods of the libertarian are freedom of action and freedom to own property, both conceived as belonging to the individual. The anarchist, by contrast, seeks some form of the good life in collaboration and cooperation with others. Anarchism is therefore intrinsically social, pluralistic, and unplanned. Because, as Isaiah Berlin says, the Great Goods are not always compatible with one another, you collaborate with people who share your priorities, understanding and accepting that others will find other structures of collaboration. And in pursuing those goods you have the humility to recognize that you don’t know how they may be achieved; that is something you discover through your collaboration. (Related by me: this and this.)

Anarchism is therefore not a system of government but a practice, and one can practice it at any level of social interaction. The parent who tells two squabbling children to work out their differences themselves, rather than appealing to a parental verdict, is practicing anarchism, and a very important form of it too.

•

The true anarchist can never throw bombs, because when you do that you are making decisions for other people without their consent, which is anthithetical to anarchism.

•

Anarchism can never be revolutionary in the sense in which political systems (communism, socialism, fascism) can be revolutionary. But the ultimate effects of anarchism can be far greater than the effects of any of those other movements. As Hannah Arendt said, every revolutionary becomes a conservative the day after the revolution; as The Who said, “Meet the new boss, same as the old boss.” Anarchism declines bosses altogether. And that is truly revolutionary – but it is only brought about by means so slow and patient that no one can see them at work.

•

It is a shame that, in The Dispossessed, Ursula K. Le Guin never describes in detail the revolution that led to the anarchist colony on Anarres. We only learn, in a wonderful story, about “The Day Before the Revolution.” So the question of how principled anarchists revolt is left unanswered.

•

James Scott speaks of “the anarchist tolerance for confusion and improvisation that accompanies social learning, and confidence in spontaneous cooperation and reciprocity.” The key point here is that link between improvisation and “social learning.” An algorithmic order is incompatible with both improvisation and social learning.

Scott again: in the last hundred years we have learned that “material plenty, far from banishing politics, creates new sphere of political struggle” and also that “statist socialism was less ‘the administration of things’ than the trade union of the ruling class protecting its privileges.”

•

Jacques Ellul thinks that Christians should be anarchists because God, in Jesus Christ, has renounced Lordship. I think something almost the opposite: it is because Jesus is Lord (and every knee shall ultimately bow before him, and every tongue confess his Lordship) that Christians should be anarchists.

To be continued…

Alan Jacobs's Blog

- Alan Jacobs's profile

- 533 followers